Introduction

This report responds to supplemental report language, approved in the 2011 legislative session, seeking our office's recommendations on the structure and duties of a statewide higher education coordinating body for California. The Legislature requested the report after rejecting an administration proposal to phase out CPEC. However, the Governor effectively reversed the Legislature's decision and vetoed state funding for CPEC, forcing its closure in fall 2011.

The elimination of CPEC makes more urgent the task of ensuring effective coordination of California's higher education system. In fact, we believe it exposes a more fundamental question about the extent to which the state needs to ensure not just coordination but oversight of its higher education system. The Master Plan and statutory provisions related to CPEC directly and indirectly refer to both concepts, but neither term is well defined. For this report, we focus primarily on the need for oversight as a set of functions, more deliberate and robust than coordination, whereby public policymakers articulate what they want from the state's higher education system, assess what it is producing, and make changes to bridge the gap between the two. Earlier models of coordination were designed to guide the development of a growing higher education system. California now needs a new model to guide the efficient and effective use of its established and extensive higher education resources.

The report includes both longer–term recommendations for creating a new state oversight structure with a formal agency, as well as interim steps the Legislature could take to help guide the state's postsecondary education policy in the absence of a new agency. In preparing the report, we consulted with a broad range of stakeholders as directed in the supplemental report language.

Background

Need for Coordination and Oversight Well Established

Promoting an Integrated System. In a 2010 report, we detail the need for coordination of the state's higher education system and trace the history of repeated Legislative attempts to strengthen this function. That report, Greater Than the Sum of Its Parts—Coordinating Higher Education in California, underscores the potential value of coordination. If California's diverse postsecondary education segments act as an integrated system in which each part makes its own contributions toward achieving a common purpose, then their combined efforts may add up to more than what the institutions could achieve independently. Insufficient coordination, on the other hand, gives rise to duplication of efforts, misalignment of student education pathways, and other inefficiencies which make it unlikely that the collective efforts of the state's public and private postsecondary institutions will meet the state's needs.

Protecting the Public Interest. Moreover, insufficient state oversight could allow state priorities to be subordinated to those of the institutions and other interests. These have been long–standing concerns. As long ago as 1960, the Master Plan for Higher Education in California found that the segment's own governing boards could not be relied on to oversee the state's higher education system on their own. Accordingly, the Master Plan called for a state oversight body, observing that it "is increasingly obvious that enforcement will require more sanctions than are available at present."

Duties Assigned to Coordinating Body. Several specific coordination functions were recommended in the Master Plan and statutorily assigned to a Coordinating Council and later to CPEC. The Legislature assigned numerous additional duties to CPEC over the years, to the extent that core oversight functions were diluted by myriad reporting requirements and other tasks. This is now generally understood to have weakened CPEC's effectiveness.

Functions Prioritized. In 2008, recognizing that CPEC could not perform all of the functions and tasks assigned to it, the Legislature adopted statutory language prioritizing four functions: (1) reviewing and assessing proposals for new public campuses and facilities, (2) reviewing and assessing proposals to create new programs at the public higher education segments, (3) serving as the designated state educational agency to carry out federal education programs and, (4) collecting and managing higher education data. Missing from this list are other duties generally considered central to oversight, including planning, evaluating effectiveness, and participating in the executive and legislative budget processes. We believe the omission of these key oversight duties from the priority list reflects the Legislature's lack of confidence in CPEC's ability to perform them effectively.

Data Role Primary. In recent years, it became evident that data functions—including maintaining a public website for data access—were the CPEC functions most highly valued by most stakeholders including the segments, policymakers, analysts, and researchers. Many other CPEC functions were largely disregarded. Although the Legislature had prioritized facility and program review, CPEC had not been influential in these areas in recent years. While the commission's administration of a federal teacher quality grant was well respected among participating institutions, this role was largely invisible to the broader public.

Persistent Oversight Concerns Span Decades

The structure of California's higher education system reaffirmed in the Master Plan—comprising three distinct public segments differentiated by eligibility pools and functions, and a number of independent and proprietary institutions—has been widely credited with facilitating the orderly growth of high–quality, relatively low–cost educational opportunities in the 1960s. By the early 1970s, however, concerns surfaced about the state's ability to sustain the Master Plan's vision of a unified, coordinated system. These concerns intensified over the ensuing decades as numerous reviews, studies, and reports identified "mission creep" across segments, decline of the transfer function, a dearth of comprehensive data, and inadequate planning as serious problems.

Some Concerns Directed at Coordinating Body. The reports also cited broad and incompatible roles for CPEC, the composition of its governing board, and lack of state support and follow–through as barriers to improving oversight.

- Several reports identified an intrinsic conflict between CPEC's coordinating function, which required that it maintain positive relationships with the segments, and its charge to produce objective and critical policy analysis with which the segments may strongly disagree.

- Some noted that segmental representatives on the commission tended to dominate CPEC's agenda, raising issues about the commission's objectivity.

- Declining state financial support hampered CPEC's effectiveness. Between 2001–02 and 2009–10, its General Fund budget declined by more than 60 percent (adjusted for inflation), seriously eroding its capacity.

- More importantly, policymakers sometimes ignored CPEC's recommendations, further marginalizing the organization and making it difficult to attract effective leadership.

Responding to these longstanding concerns about CPEC, several Governors and Legislators have attempted to reform, combine, replace, or eliminate CPEC. More than a dozen proposals from the Legislature and the administration were introduced in as many years. No significant reforms, however, were enacted.

Governor Eliminates CPEC Through Budget

Governor's "Blue Pencil" Eliminates CPEC Funding. The Governor proposed eliminating CPEC in his May Revision budget proposal. Under this proposal, the agency would have been phased out over a period of six months with the exception of one function—management of a federal teacher quality training grant—that would have been moved to CDE. The Legislature rejected the May Revision proposal, and instead adopted supplemental report language calling for this review. In signing the 2011–12 Budget Bill, the Governor used line–item veto authority to eliminate all General Fund support for CPEC. Although the commission's statutory authority remains intact, the agency was forced to close in fall 2011.

CPEC Winds Down. Although the Governor's funding veto was effective July 1, CPEC's closeout required about five months to complete. During that time, CPEC transferred its reports and historical materials to the State Archives and the California State Library, and its federally funded Improving Teacher Quality State Grants Program to CDE. Most of CPEC's 21 staff members retired from state service or found other positions. When it closed its doors on November 19, CPEC laid off two remaining staff members. The Department of General Services collected office furnishings and equipment, and is seeking a new tenant for the office space. The Department of Finance (DOF) has estimated closeout costs at roughly $850,000, including final payments for salaries, leave payouts, and other benefits, and suggested that the Governor may include the final amount in his 2012–13 budget proposal.

Data Transferred to CCC Chancellor's Office

The commission gained the ability to collect and aggregate student records from the three segments relatively recently. Although Chapter 916, Statutes of 1999 (AB 1570, Villaraigosa), required the segments to provide student records, the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) did not begin doing so until the mid–2000s. The data warehouse CPEC developed with these records proved useful for understanding higher education processes and outcomes in California. Prior to closing down, CPEC transferred its data warehouse to the CCC Chancellor's Office.

What Data Resources Did CPEC Have?

The commission compiled two main categories of higher education data:

- Individual Student Records. The commission maintained individual student records from each of the public higher education segments dating back to 1993 for the CCC and 2000 for UC and CSU. Information contained in these records includes high school of origin, postsecondary enrollment history, program of study, transfers, completions, degrees awarded, and demographic information. The commission was able to link data across the three segments using unique student identifiers. For example, a community college record for a transfer student could be matched with the corresponding university record.

- Aggregate Data From Other Public Sources. Fulfilling its role as a clearinghouse for California higher education data, CPEC collected publicly available data sets from federal sources including CDE, Census Bureau, and Bureau of Labor Statistics, as well as the state Employment Development Department (EDD) and other sources. The commission extracted California data from these data sets and made the resulting information readily available through its public website.

How Did CPEC Use These Data? Commission staff used these data resources to meet the agency's research and reporting responsibilities. In some cases, research was conducted in collaboration with other agencies, including CDE, colleges and universities, and EDD. In addition, CPEC made much of its data available to the public through preconfigured reports and an interactive reporting tool on its website. (To protect student privacy, only aggregate data with no individual student identifiers was made available to the public.)

Examples of reports available from CPEC's public website include:

- Freshman Pathways: flow of recent high school graduates to public colleges and universities, by campus.

- Transfer Pathways: flow of community college students to public four–year colleges and universities, by campus.

- Trend Analyses: data over time.

- Custom Data Reports: California students by gender, age, ethnicity, student level, institutions, and segment.

- Pre–Configured Reports: various quick data reports located on the commission's website.

Where Did the Data Go? Shortly before its closure, CPEC transferred its database servers to the CCC Chancellor's Office. (The administration, however, did not transfer the associated funding and personnel.)

Under federal privacy laws, each segment is permitted access only to its own student data and should not have access to individually identified student records from other segments. (See nearby box for a description of federal and state privacy provisions.) Accordingly, CPEC's transfer of the data warehouse to CCC could be considered unallowable disclosure of student records to a third party. Recognizing this, UC and CSU formally requested that CPEC return to them their own students' records. Instead of returning the data directly to each segment, however, the universities requested that CPEC transfer their data to CCC, which has agreed (through a formal interagency agreement) to manage the data on their behalf. Through this legal maneuver, the segments believe they have satisfied the privacy protections in the law while preserving the value of the intersegmental data resources CPEC had assembled.

Federal and State Privacy Laws

The Family Education Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) is the major federal law affecting access to student records. The main objectives of FERPA are to (1) ensure students and their parents have access to all information in a student's official academic record, and (2) prevent unauthorized access to individually identifiable information in a student's records. Under this law, individually identifiable student data may not be disclosed without the student's or parent's written consent in most circumstances. The entity directly collecting student data has the responsibility for ensuring compliance with the law. According to federal privacy officials, only statewide education authorities with program evaluation responsibilities may maintain intersegmental data under FERPA.

California's privacy laws also include provisions limiting who can receive individually identifiable data from a state agency or department. In addition, state laws require review by an independent review board for any new release of individually identifiable information to a researcher.

|

Although it is now stored and hosted in new locations, the public website remains available at CPEC's same Internet address. Individual student data is on a secure server under the management of CCC Information Systems staff, with separate "partitions" on the server for each segment's data. Eventually, CCC plans to move the data to the Corporation for Education Networks in California (CENIC), a membership organization that operates the high–speed Internet "backbone" through which schools and other educational institutions in California connect to the broader Internet. While CENIC will provide the infrastructure for the databases, management will remain with CCC under current agreements. This may not be a viable long–term solution, however, as discussed later in this report.

Separately, CDE is seeking a federal grant to support a statewide kindergarten through postsecondary (K–20) data system. If its appeal is successful, this funding could help support intersegmental data resources.

Role of CCC May Be Problematic. The transfer to CCC of CPEC's data warehouse may not be a viable long–term solution for management of intersegmental data. Federal privacy officials with whom we consulted expressed concerns about whether the current arrangement (in which CPEC "technically" returned data to each segment while physically transferring it to CCC) meets federal privacy requirements. They agreed this arrangement could comply with federal privacy laws if the CCC were determined to be a statewide education authority with assigned responsibility for data collection and program evaluation across postsecondary education. Such a designation would likely require a statutory change to provide the necessary authority.

Questions regarding data access will have to be resolved this year if the data warehouse is to be kept current. With the segments' cooperation, CPEC completed its annual update of student data in fall 2011. The next update is due in fall 2012, and will require CCC to use personally identifiable information in student records from each segment. Federal privacy officials were especially concerned about CCC's legal authority to perform this update or any other studies that involve using student identifiers across segments without specific statutory authority for postsecondary data.

Alternatives for Maintaining Data Resources. The CCC is providing a valuable service to the state by accepting CPEC's data warehouse, immediately making the CPEC website and associated data resources available to the public and securing student record data on behalf of the segments. With no other transition plan in place, it is possible that the extensive data resources CPEC had assembled would otherwise have become unavailable. For the long term, however, there remain legal and policy issues to be resolved.

Federal privacy officials have confirmed that CPEC's data warehouse legally could be transferred to a different state oversight body for postsecondary education. They pointed out that state departments of education commonly receive student data resources when other entities holding student records (K–12 or postsecondary) are terminated. As statewide education authorities with data collection and program evaluation responsibilities, education departments can take over management of the records without constituting disclosure of the information. It is unclear, however, whether CDE currently possesses the statutory authority to maintain intersegmental data. The state could grant the necessary authority to CDE, CCC, or another entity designated as a statewide education authority.

The segments have laid some groundwork for a Joint Powers Authority (JPA) to oversee intersegmental data. These efforts are on hold due to the difficulty of creating new public organizations in the current fiscal environment. In addition, discussions with federal officials suggest a JPA could encounter the same or greater legal problems as the current arrangement.

Policy Considerations. In addition to the legal questions, a significant policy issue concerns control of intersegmental data. Under the current arrangement, each segment considers that it has sole control over access to its own student records. If outside analysts wish to use information from these records for state policy purposes (for example, to study transfer outcomes by institution), they need the approval of the segments involved. After approval, CCC (or CENIC as a contractor) would match the specified data and provide a file to the analysts. In contrast, CPEC was able to perform such studies on behalf of the state and provide data access to researchers without having to secure individual approval from the segments.

We believe there is a potential conflict of interest in relying on the segments for permission to study their performance and that of their students. For this reason, we believe it is in the state's best interests for a third party independent of the segments to maintain the data. The Legislature previously assigned this role to CPEC, and later strengthened CPEC's statutory authority to require data, after some frustration with segment responses to state data requests.

Future of Coordination Unclear

The Governor's veto message acknowledges the importance of higher education coordination and cites CPEC's ineffectiveness, rather than a diminished need for coordination, as the reason for the veto. In the message, the Governor requests the three public higher education segments, along with stakeholders, to explore alternative ways to improve coordination and development of higher education policy.

In the wake of CPEC's closure, the segments have stepped in to assume roles previously performed by CPEC in two areas:

- The CSU Board of Trustees has initiated a revision of the university's comparison groups for executive compensation. Previously, CPEC was responsible for developing comparison groupings for various purposes, including tuition levels and executive compensation, using a process agreed upon by administration, legislative, and segment representatives. The CSU's process departs from the agreed–upon methodology in several significant ways, and involves no direct legislative or administration participation (although comments from LAO and DOF were solicited after prompting by a legislative committee).

- The segments have reestablished the student data warehouse that CPEC had created as a public resource. The segments contend that policymakers, legislative analysts, and researchers will need their explicit permission to conduct a study or evaluation using these data to the extent the data are not already publicly available.

As described in our earlier report on coordination, institutions and their governing boards have their own interests and priorities, which do not always match the broader public interest. The segments' recent actions on comparison groups and data resources may be an early indication that the absence of a formal coordinating structure increases the opportunities for them to emphasize their institutional interests.

Improving Higher Education Oversight

Purpose of Oversight. In our view, higher education oversight enables policymakers (and to some extent, other audiences) to monitor how efficiently and effectively the system is serving the state's needs, and make changes to improve its performance. This view of oversight focuses on outcomes, and is also concerned with program, administrative, and resource allocation decisions at all levels. The state has a role in oversight of private as well as public higher education, although the policy tools available to the Governor and Legislature differ between the two.

This section presents a conceptual view of how the state can improve higher education oversight. Figure 1 provides an illustration of some of the terms we use in this section. The last section provides more specific recommendations for improvement, both short and long term.

Figure 1

Illustration of Key Terms for Higher Education Oversight

|

Term

|

Example

|

|

Vision

|

The purpose of the postsecondary education system in California is to align the knowledge and skills of the adult population with the civic and workforce needs of the state of California.

|

|

Goal

|

Achieve measurable, value–added student learning outcomes.

|

|

Measure, Metric, or Indicator |

Mean change in scores for individual students from freshman to senior year on specified portions of the Collegiate Assessment of Academic Proficiency or Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA).

|

|

Target

|

System target is for each segment to achieve mean gain scores of 50 points on performance task and 100 points on writing task of CLA (for example). Segments allocate targets to individual campuses to achieve system target.

|

System Should Be Guided by State's Needs

In an earlier policy brief we assessed the state's vision for higher education, concluding it was no longer as cohesive as it had been in earlier periods. Our use of the term vision was deliberate. Our view of oversight presumes public policymakers have envisioned what success looks like, and thus what the system should be achieving. This is not a trivial requirement. The higher education system is a complex enterprise with multiple missions and many constituencies. Policy decisions often involve difficult tradeoffs among legitimate competing interests. For decades, policy experts have called for the state to articulate its needs in the form of clear goals and priorities for higher education. That this remains a work in progress in part reflects the difficulty of the task.

Master Plan Provides Insufficient Guidance. For more than 50 years, the Master Plan has been looked to as the primary expression of the state's vision for higher education. Its emphasis on access, affordability, and quality are well known and invoked widely in policy discussions. However, these principles, compelling as they may be, are insufficient to guide policymakers in the 21st century. The Master Plan principles lack specificity, are not prioritized, and fail to take into account the many changes in California's population and economy over the last half–century.

Moving Forward From Here. The Legislature has a range of possible approaches for articulating its expectations for higher education. Ideally, the Legislature could develop specific and measurable goals which are more likely to improve performance than vague goals. We would acknowledge that it is difficult to agree on goals. There is sometimes little analytical basis for setting a specific goal in a given area, and efforts to do so could result in arbitrary or unrealistic goals. As well, elected officials may place different value on various aspects of higher education, making it problematic to win agreement on priorities.

Yet common ground can often be found between specific goals and general principles. The Legislature has previously agreed on important questions to guide higher education policy, and has put in place a number of mostly ad–hoc reporting requirements through statute, budget language, and supplemental reports. Many of these reflect broadly shared concerns about particular aspects of the higher education system and its performance. Examples include efficiency of the transfer process, preparation of math and science teachers, and effectiveness of campus financial aid programs.

Progress Should Be Monitored Using Standardized Measures

Whatever level of goal specificity the Legislature is able to achieve, it can begin monitoring the system's performance in a more systematic way. For example, the Legislature could regularly review existing data about access, affordability, quality, and student progression and completion for the higher education segments. (See Figure 3 for examples.) A consolidated report drawing on various sources and presenting information concisely could facilitate such a review. Several states use performance "dashboards" or "scorecards" (such as the one illustrated on the cover of this report) to track measures of interest.

Figure 3

Examples of Existing Measures for Articulated Values

|

Articulated Values

|

Existing Measures

|

|

Access

|

|

- Application, admission, and enrollment reports

|

|

Affordability

|

- Total instructional costs; student and state shares

|

- Total and net costs of attendance

|

|

Quality

|

- Passage rates on licensure and certification examinations

|

- Value–added measures from system accountability reports

|

|

Student progression

|

- Year–to–year persistence rates

|

|

|

|

Student completion

|

|

|

|

Other states as well as associations of state governments have developed integrated sets of measures for higher education productivity and efficiency that California could employ. (For example, the National Governor's Association and Complete College America have developed measures of student progression, student completion, and system and institutional efficiency and effectiveness.) Some of these are quite sophisticated and adjust for differences among colleges or states, while others are simpler and more intuitive. The Legislature could adapt one or more of these frameworks for its own needs. Routine monitoring of the higher education system's performance could improve oversight and inform further discussion of goals and priorities. Measuring performance and publicizing results also focuses institutions' attention on the measures of importance to the state and creates an incentive for them to improve their performance.

Whether linked to specific goals or used more generally to track performance in areas of interest to public policymakers, the choice of measures matters. Poorly designed measures could give misleading or confusing signals to policymakers and the public. For measures to be useful, there must be broad agreement that they accurately reflect the parameters they are intended to measure, and they must be defined consistently to ensure comparability over time across segments.

Selecting Measures and Collecting Baseline Data. While the Legislature may formally adopt higher–level goals, it would be impractical to include in statute the level of detail needed to define measures for monitoring progress across a diverse higher education system. Instead, statute can delegate technical decisions about specific measures and reporting protocols.

As an illustration, consider a goal of improving student completion. Measuring this would require several decisions:

- Whether to count transfers and certificate awards as successful completion, in addition to degree awards.

- Whether to focus on the absolute number of completions, the increase in number over time, the percent increase over a baseline, the rate for a particular cohort of students over a given time period, or a rate per 100 full time–equivalent students in a given year.

- For any rate, which students to count in the denominator—many students enroll in courses with no intention of completing a full academic program.

- Which data elements and data sources to use, to ensure validity and comparability across institutions and over time.

These are only some of the types of questions analysts would have to consider when measuring progress against each goal.

The Legislature could delegate these questions to a technical group including representatives from the administration, legislative staff, the segments, and independent researchers with expertise in higher education performance measurement. This group could consider existing, well–defined measurement frameworks from national associations as a starting point. The technical group could also be responsible for collecting baseline data for comparisons over time and recommending performance targets.

Setting Targets. Another question facing policymakers is how they will evaluate performance once it is reported. States with a goal–setting approach usually set numeric statewide targets for each measure of performance. In our completion example, a numeric target could be to increase by 1 million (above a baseline projection) the cumulative number of degrees and certificates students earn by 2025. Alternatively, it could be to increase awards by 2 percent annually; or to match a benchmark such as the top quartile of states, best–performing states, or comparison institutions in completion rates or number of completions per $100,000 of spending. The state could allocate a portion of the target to each segment and compare performance against these targets. Although a technical group is best suited to perform the analytical work of measuring current performance and assessing the feasibility of reaching certain targets, the setting of targets is a policy decision.

Using Comparisons. Alternatively, the state could compare performance directly with other states or comparison institutions. Direct comparisons across institutions can be problematic, however, because of differences in institutional missions, program mix, student populations, resources, and other factors. Emerging research focuses on input–adjusted and value–added measures of institutional performance. Adjusted outcome measures (which may adjust for the academic achievement or socioeconomic status of incoming students, for example) and longitudinal measures of learning (testing students as freshmen and again as seniors) can provide more accurate information than traditional measures regarding how well institutions are serving their students, leveling the playing field for comparisons. Higher education researchers and policymakers disagree about whether these measures are ready to be broadly employed, especially for high–stakes applications such as performance funding. Some believe more research and development is needed to refine them. There is broad agreement, however, that policy analysts should use these measures to inform policy discussions, along with clear communication about their limitations.

Data Should Be Collected Systematically

Data is a vital tool for coordination and oversight, both for measuring progress toward goals and more broadly for understanding costs, changes in student enrollment patterns, effects of financial aid and other state programs, and other aspects of the state's higher education system. California has made progress on higher education data collection. In recent years, CPEC worked with the segments and CDE and other state agencies to systematically collect student data and make it accessible to policymakers, analysts, researchers, and the public. The closure of CPEC confronts policymakers with the central question of who will collect data to assess the higher education system and its progress toward state goals. To enable effective oversight, the state will need to assign this function to another entity and direct the segments to continue providing student records in standardized formats to be used for routine and ad–hoc analyses and reports.

Policy and Budget Decisions Should Be Informed by Analysis of Progress

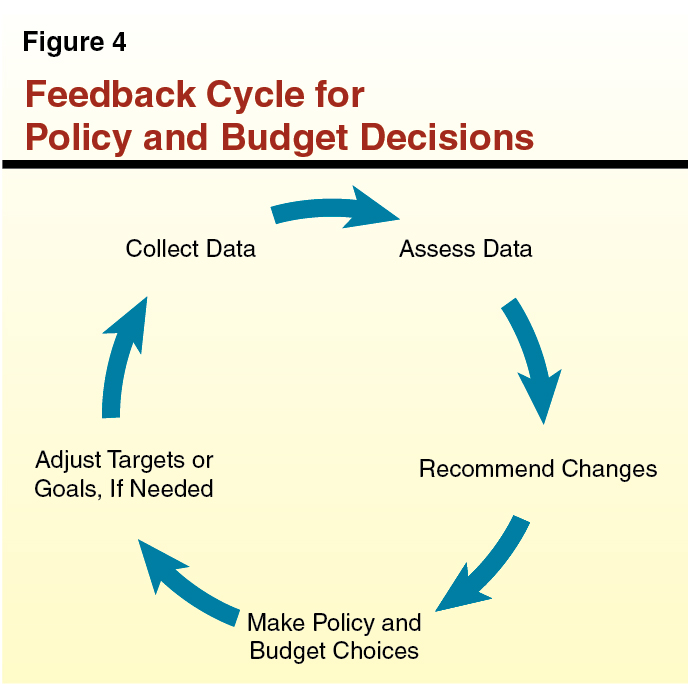

Regular measurement of system performance provides crucial data for assessing progress toward established goals. Even more importantly, it can shed light on the effectiveness of state policy and budget decisions, thus paving the way for continuous improvement and adjustment. Figure 4 illustrates this cycle.

Independent Assessment of Data. While data collection and dissemination is largely an administrative responsibility, assessing that data is an analytical task requiring expertise, sound judgment, and independence. It is here that the need for an independent oversight agency is most pronounced. For example, if college attainment rates were to decline, it would be necessary to understand whether this was the result of changes in student preparation, changes in student enrollment patterns, issues with transfer and alignment, affordability challenges, or other factors. Such analyses could be politically sensitive, reflecting on decisions made by campuses, segments, or policymakers. Independence from the segments and both branches of government would protect against undue political influence in assessing the data. In addition, the audience for such analyses includes the administration, the Legislature, and the higher education segments. If analyses were conducted within any one of these spheres, the others might reasonably be concerned about bias stemming from partisan, ideological, or financial interests.

Recommending Changes. A more challenging aspect of the analysis involves recommending changes in policy that address these areas. Recognizing that different observers could reasonably arrive at different prescriptions for the same symptoms, the analysis should be presented publicly in a format that enables policymakers and others to readily evaluate results and recommendations. Public transparency is especially important because there are multiple audiences for an analysis of higher education performance, and several levels of responsibility for making changes.

Making Policy and Budget Choices. Based on progress towards meeting state goals and the continued analysis of state's needs and priorities, policymakers at various levels can then review and modify policies and funding to better align performance of the higher education system with the needs of the state of California. The Legislature's and Governor's roles in this process are paramount, and could be facilitated by an established process to periodically review progress and consider policy recommendations. For example, the Legislature could hold annual hearings where the oversight body reports its findings and recommendations, representatives of the segments and other postsecondary agencies offer comments on the analysis, and other stakeholders have an opportunity to provide input. Ideally, discussion would encompass the broad system of postsecondary education, including financial aid programs and private institutions as well as the public segments.

Tiered Responsibility. State policymakers, the segments, campuses, and other parts of the postsecondary system (the Student Aid Commission, for example) have distinct roles in overseeing postsecondary education. The Legislature and Governor establish the state's expectations for higher education statewide and communicate them through budgets, statutes, committee hearings, and other mechanisms. The segments' and other agencies' governing boards and administrative leaders are responsible for ensuring their institutions contribute toward meeting the state's expectations. Just as their missions and functions are differentiated, so too will their individual contributions to meeting state goals differ. In addition, there is a role for an independent perspective in monitoring the segments' contributions and assisting the Governor, Legislature, and governing boards—through data collection, analysis, and policy advice—to meet the state's postsecondary needs.

Adjust Goals, Indicators, and Targets as Necessary. The Legislature will need to periodically review goals, indicators, and targets to reflect changing priorities, technology, and expectations. It could do so as part of the annual hearing process suggested above.

Recommendations

Need for Oversight Remains. The Governor eliminated CPEC because it had proved ineffective, not because the need for oversight had diminished. In fact, we find that the state's higher education system requires oversight that is more robust than what the state has had to date.

The Legislature, the administration, segment governing boards, and an independent agency all have distinct oversight roles. The Legislature could take several steps to begin establishing an effective oversight structure. The Legislature could also implement a number of short–term steps to improve oversight in the interim.

Strategic Actions

Articulate State's Needs. As discussed above, we envision oversight as a process which (1) monitors how effectively the postsecondary system is serving the state's needs, and (2) makes changes to improve its performance. This presumes policymakers have identified the state's needs, suggesting some metrics against which to measure performance.

Accordingly, our foremost recommendation is for the Legislature to articulate the state's postsecondary education needs in some form. This could involve setting specific goals, as many states have done, or identifying key areas or outcomes of interest to the state. In either case, we would encourage the Legislature to prioritize among identified needs.

Best practices from other states suggest that developing such an agenda involves broad stakeholder participation and formal deliberation by policymakers. California has begun the deliberative process on several fronts, including the Legislature's Joint Committee on the Master Plan for Higher Education, a number of legislative proposals to establish an accountability framework, and efforts by several nongovernmental organizations to develop recommendations for statewide goals. The Legislature adopted the Joint Committee's report calling for state goals in Chapter 163, Statutes of 2010 (ACR 184, Ruskin). The Legislature could build on those efforts to gain broad agreement on postsecondary education needs for California, and establish them in statute.

For example, the Legislature could use hearings on proposed legislation as a vehicle for stakeholder participation in refining goals. (See nearby box for a summary of current legislative efforts.) Participation by the Governor's office is key, given that previous Governors have vetoed bills establishing goals and accountability frameworks despite broad support within the Legislature.

Current Legislative Efforts to Improve Oversight

- Assembly Bill 2 (Portantino, 2011) would establish a new accountability framework for achieving prescribed educational and economic goals.

- Senate Bill 721 (Lowenthal, 2011) would likewise establish an accountability framework for achieving prescribed educational and economic goals.

- Senate Bill 885 (Simitian, 2011) would encourage the design and implementation of a high–quality, comprehensive, and longitudinal preschool through higher education (P–20) statewide data system that meets specified goals.

|

Assign a Technical Work Group to Define Measures, Collect Baseline Data. We recommend the Legislature delegate technical decisions about specific measures and reporting protocols to a technical working group with representatives from the administration, legislative staff, and the segments, as well as independent researchers with experience in higher education performance measurement. The group could also collect baseline information and recommend targets for the state's performance on the measures, considering current performance and various types of benchmarks. The ultimate selection of targets, however, would need to be decided by the Governor and Legislature.

Use Performance Results to Inform Policy Decisions. We recommend the Legislature delegate data analysis, interpretation of results, and development of policy recommendations to an entity independent of the segments, and direct the organization performing these functions to report measures and results clearly and concisely. We also recommend the Legislature convene regular oversight hearings to review progress and consider policy changes. In considering actions, we recommend the Legislature focus on setting expectations and incentives, and that segment and other institutional governing boards focus on operational and programmatic improvement efforts.

Establish a Formal Oversight Body. For the long run, we reiterate our earlier recommendation to establish an effective, independent oversight structure for higher education. In the past, we have recommended reforming or replacing CPEC. The Governor's elimination of CPEC this year could pave the way to create a far more effective organization in the future.

Our 2010 report on higher education coordination includes a number of specific recommendations for improvement, summarized in Figure 5 (see below). Recommendations relative to CPEC's organizational structure and duties include:

- Increase the body's independence from the public higher education segments.

- Develop a more unified governing board appointment process.

- Assign to it limited and clear responsibilities.

We believe those earlier recommendations remain relevant today. In addition, we have continued to explore oversight structures and roles in consultation with stakeholders, and are developing additional options for the Legislature to consider. For example:

- Pared–down duties could focus on postsecondary effectiveness and efficiency.

- An organization with a stronger oversight role in capital outlay decisions could better balance institutional or other interests with a statewide view.

- The organization could ensure a more integrated approach to the state's overall higher education policy by, for example, including in its purview private postsecondary education.

- A more streamlined organization could maintain a minimal research staff and make expanded use of independent researchers to conduct policy studies and analyze data.

- Nearly all stakeholders we consulted identified the need for better linkages with K–12, workforce, and economic development agencies, with respect to both data and policy development.

At the same time, we recognize the difficulty of creating a new public organization in the current fiscal environment. We will continue to refine our recommendations on the structure and duties for a new independent entity to perform some of the key functions required for effective higher education oversight. In the meantime, we turn below to interim measures to ensure oversight in the absence of an independent entity.

Figure 5

Summary of Recommendations From 2010 LAO Report

|

|

|

Set a Clear Public Agenda for Higher Education

|

- Set specific statewide goals (see sample goals)

|

- Use goals as framework for an accountability system

|

|

Strengthen Coordination Mechanisms

|

- Align funding formulas with state goals

|

- Simplify articulation and transfer processes

|

- Improve oversight for major policy decisions

|

- Reform program approval process

|

- Consider regional coordination

|

|

Rebuild State's Capacity for Policy Leadership

|

- Maintain coordinating board's independence from executive and legislative branches and increase its independence from higher education segments

|

- Revise appointment process for the coordinating board

|

- Assign clear responsibility for shepherding the public agenda

|

- Create a more comprehensive statewide student data resource with enhanced research and analysis capabilities

|

We recommend a number of immediate solutions to guide higher education policy in the interim. These include ensuring continued access to higher education data, relying on existing resources for budget and policy recommendations, limiting major new investments in facilities and programs, and monitoring major reallocation decisions within the segments.

As part of the legislation, the Legislature could direct the three public segments to (1) continue providing data (or otherwise making it available) for intersegmental data evaluation and (2) work with economic development, workforce, and public education officials to improve the state's capacity for longitudinal outcome analysis. We believe there should be a clear expectation that student record data from the public segments remain a public resource that is available for public purposes so long as all parties maintain appropriate privacy safeguards.

Capital outlay and other long–term proposals (such as the establishment of new professional programs or off–campus centers) are of particular concern in the absence of an oversight structure. It is difficult for legislative committees to devote the time and resources needed to identify each proposal's long–term costs, alignment with state needs and institutional missions, duplication of other resources, and priority relative to other long–term demands on the General Fund. While our office and DOF will continue to analyze these proposals, neither agency has the resources to routinely conduct the type of in–depth evaluation that an office focused exclusively on higher education could provide. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature limit significant new commitments of resources until a more comprehensive higher education oversight structure is in place to support the Legislature's decision making.

While the Legislature can weigh in on major new programs through the budget process, many program changes are made through reallocation of existing resources within campuses. We recommend the Legislature require the segments to report annually on new program approvals, program deletions, and substantive program changes, until such time as a structure is in place to independently measure outcomes on behalf of the Legislature.

Taken together, we believe these recommendations would improve higher education oversight in the short term while providing an opportunity for the Legislature to establish an effective, outcome–oriented process to improve the performance of the higher education system in meeting the state's priorities.