Executive Summary

Reductions to school districts' budgets over the past five years have resulted in a sharp decline in the teacher workforce, with the number of full–time teachers decreasing by 32,000 since 2007–08. One way school districts have reduced their workforce is by laying off staff. This has led to an increased focus on how the teacher layoff process works. This report gives an overview of the existing layoff process, evaluates how well the process is working, and makes recommendations for improving its effectiveness. For our analysis, we distributed a survey to all public school districts in the state asking them about their implementation of the teacher layoff process, used information provided by two state agencies—the California Department of Education (CDE) and the Office of Administrative Hearings (OAH), and included information from the California Teachers Association (CTA).

Districts Are Issuing More Layoff Notices Than Necessary. One of the most significant problems with the existing layoff process is the notification time line. The state–imposed layoff time line is disconnected from both the state budget cycle and the availability of critical local information. Because of this misalignment, the number of teachers that are initially noticed typically far exceeds the number of teachers that are actually laid off for the following school year. Moreover, the August option for laying off additional staff following the start of the state's fiscal year is often not helpful. Though this contingency option is designed to help districts balance their budgets in the summer if the final state budget differs significantly from the May Revision, it officially has been activated only a few times.

Recommend Aligning Layoff Time Line With State Budget Process. We recommend changing the time line to later in the year—to June 1 for initial layoff notices and to August 1 for final notices. This would better align the layoff deadlines with the state budget process—resulting in fewer notifications unnecessarily issued by school districts because they would have better fiscal information on which to base their layoff determinations. Fewer initial notifications, in turn, would reduce the time and cost invested in conducting the layoff process, result in fewer teachers unnecessarily concerned about losing their job, and minimize the loss of morale in the school communities affected by layoff notices. We also recommend the Legislature replace the existing August layoff option with a rolling emergency layoff window. The window would require a district to notify teachers and complete due process activities within 45 days of a major state budget action.

Hearing and Appeals Process Adds Some Value, but Is Costly. Another significant problem with the teacher layoff process is unnecessary costs incurred by school districts because of inefficiencies in the hearing and appeals process. The current hearing and appeals process helps ensure districts implement the state's layoff process correctly, with OAH assisting districts in correcting mistakes. However, teachers' automatic right to a hearing adds significant costs without adding substantial value. The hearings are primarily used to check factual mistakes, which could be achieved between the district, the bargaining unit, and OAH without conducting formal hearings. Our survey indicates that districts on average spend roughly $700 per–noticed teacher, with the largest costs relating to district personnel and legal activities. With the costs estimates derived from our survey, we estimate that districts spent about $14 million statewide on layoff–related costs in 2010–11.

Recommend Streamlining Hearing and Appeals Process. We recommend eliminating teachers' right to a hearing and replacing the hearings with a streamlined alternate process that ensures: (1) all relevant information is presented to OAH for review and (2) both district and union personnel have an adequate opportunity to review, comment upon, and dispute each other's information. Eliminating hearings would increase the efficiency of the layoff process while maintaining the oversight needed to ensure teachers are laid off correctly according to state law.

State Values Seniority in Layoff Process. A more challenging area for the state to address is the selection criteria used to determine which teachers will be laid off. Current law requires that districts lay off teachers in inverse seniority order but it provides some exceptions for deviating from seniority to protect specialized teachers or to achieve equal protection of the laws. Using seniority on a statewide basis for laying off staff has some benefits. On one hand, it is an objective, standard approach that is transparent and easy to implement. On the other hand, basing employment decisions on the number of years served instead of teachers' performance can lead to lower quality of the overall teacher workforce. California also is different than many other states—the majority do not prescribe seniority–based layoffs but rather allow school districts themselves to decide how to lay off their staff.

Recommend Exploring Alternatives to Seniority. Given the limitations of using seniority as the primary factor in layoff determinations, we recommend exploring statewide alternatives that could provide districts with the discretion to do what is in the best interest of their students. Ideally districts would use multiple factors in making layoff determinations—factors that result in the least harm to students, the overall teaching workforce, and the school community. Some alternative factors districts could consider are student performance, teacher quality, and contributions to school community. Many of these factors could be considered at both the local and state level, but some (such as contributions to school community) might be impractical data collections for the state to pursue. Nonetheless, the state could play a key role in helping districts develop reliable teacher quality information. Specifically, it could encourage the CDE to collect and disseminate district best practices on evaluating teacher performance.

Recommend Carefully Reassessing State Involvement and Expanding Locally Negotiated Options. As evident from the above description, state law regarding teacher layoffs is very prescriptive—notably more prescriptive than layoff policies in many other states. Moving forward, the state faces difficult trade–offs in deciding how involved to remain in local personnel matters. On the one hand, if the state retains its highly involved role, it can help assure that districts do not make layoff decisions that are arbitrary, biased against individual teachers, or based upon political or personal motivations. On the other hand, the state's existing involvement might be deterring districts from taking the time and effort to establish their own layoff procedures that are better aligned with local needs. Moreover, the state recently has become less prescriptive in a number of areas in the state budget, including education. We recommend the Legislature carefully reassess the need for and benefits of its current prescriptive role in local personnel matters. One option for providing greater local control would be to allow districts and local bargaining units to negotiate more aspects of the teacher layoff process.

Introduction

Over the past several years, school districts in California have experienced ongoing cuts to their operational budgets and made difficult associated decisions—including reducing their teacher workforce. One of the primary ways districts are able to reduce their workforce is by laying off staff. Under current law, the state sets forth many aspects of the layoff process, including establishing time lines and procedures for notifying teachers of layoffs as well as specifying how teachers may appeal layoff decisions. In this report, we provide background information on the size of California's teacher workforce, give an overview of the existing teacher layoff process, assess how well the process is working, and make recommendations for improving its effectiveness and lowering its costs.

For this report, we use information provided by CDE, OAH, and CTA. We also distributed a survey in the fall of 2011 to all public school districts in the state asking them about their implementation of the teacher layoff process. The survey asks a range of questions regarding the time line districts use to meet state notification deadlines, the selection criteria districts use to lay off teachers, and the costs of undergoing the process. Out of about 950 districts statewide, 230 completed a response. We received responses from eight of the state's ten largest school districts. In total, the districts that responded to our survey represent 44 percent of the state's average daily attendance (ADA). Though representing a large portion of total ADA, our survey sample is slightly more representative of large urban districts. The survey questions and results are contained in the appendix at the end of this report.

Recent Trends

Statewide School Funding Reduced 8 Percent Over Past Five Years. Programmatic per–pupil funding is lower today than five years ago. In 2011–12, per–pupil funding is $7,580—8 percent lower than the 2007–08 level of $8,235. This reduction in school district programmatic support would have been deeper had it not been for a substantial amount of one–time federal aid. Between early 2009 and the end of 2010, California received a total of $7.3 billion in special one–time federal aid ($6.1 billion from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and $1.2 billion from the Federal Education Jobs Act) that could be spent over the 2008–09 through 2011–12 period. In addition to this federal aid, the state took several actions to mitigate programmatic reductions, including deferring certain payments and swapping certain fund sources. Although these federal and state actions allowed school districts to save many teacher jobs, they were not sufficient to forestall teacher layoffs entirely.

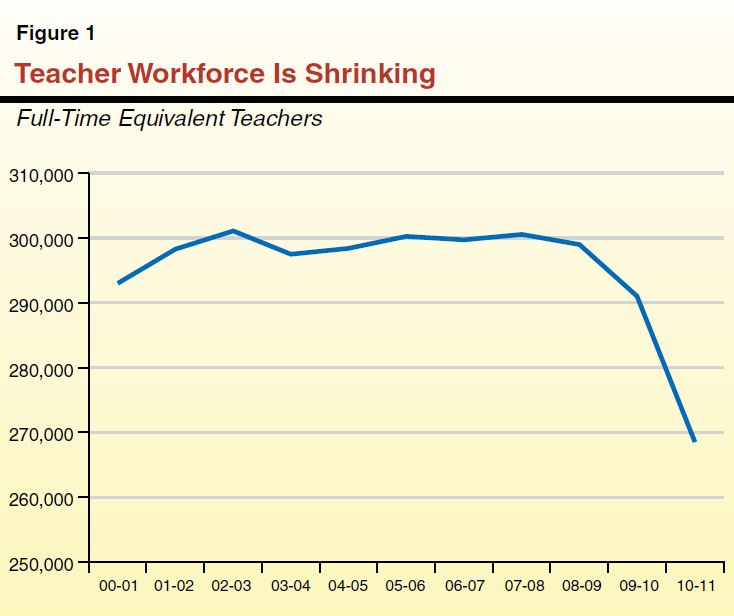

Teacher Workforce Also Reduced Significantly Over Past Few Years. In response to these funding reductions, many districts have reduced staffing levels (the largest operational expense in their budgets). As shown in Figure 1, the size of the state's teacher workforce has decreased by about 32,000 teachers (11 percent) since 2007–08. While the teacher workforce has been shrinking, the statewide student population has been generally steady. The net effect of these two trends has been an increase in the number of students per teacher—climbing from 19.4 in 2007–08 to 20.5 in 2010–11.

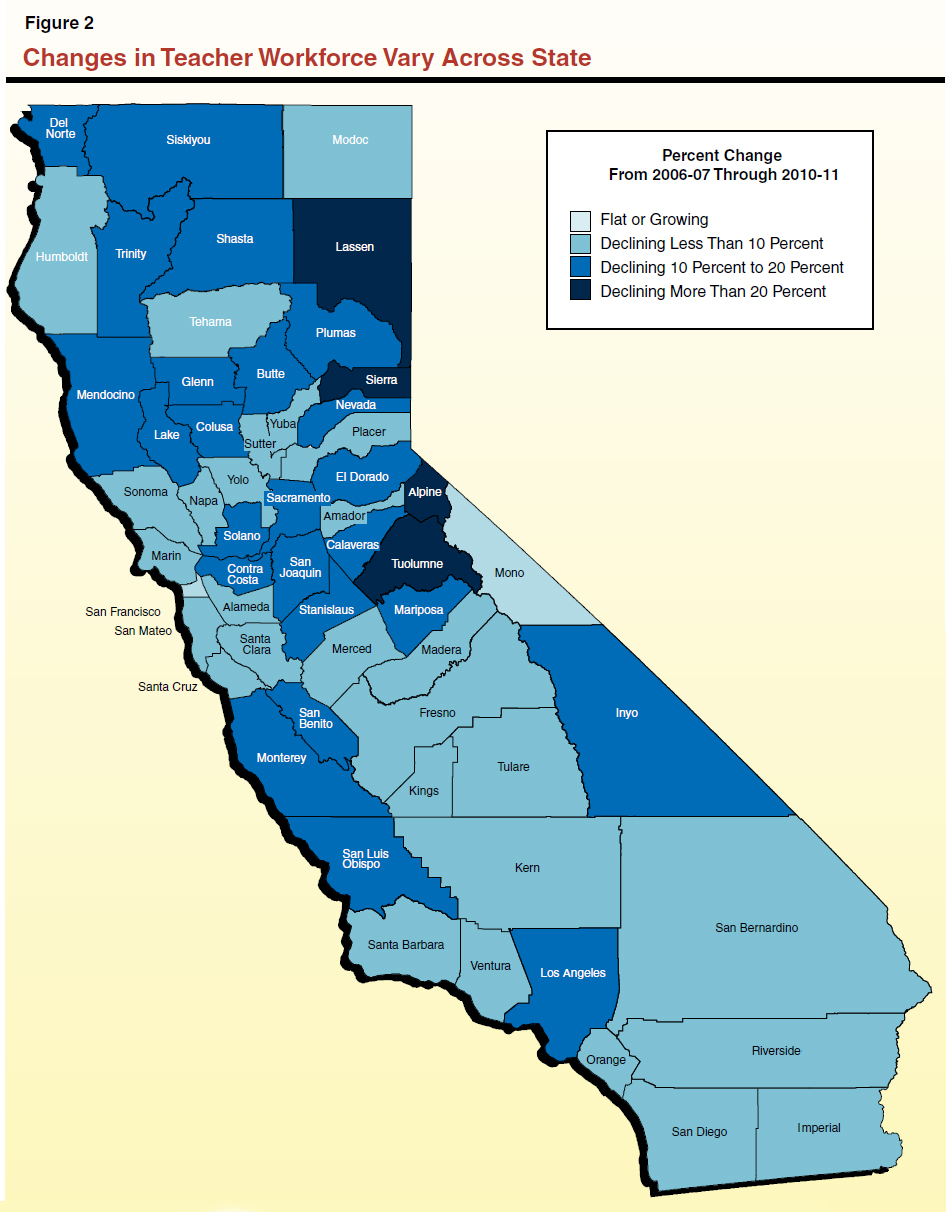

Some Regions Experiencing Deeper Teacher Workforce Reductions. Though the statewide teacher workforce has been reduced by 11 percent, various regions throughout the state have been experiencing deeper reductions—primarily because they are undergoing significant declines in student enrollment in addition to budget reductions. The vast majority of districts are reducing their teacher workforce, with 342 districts reducing their workforce by more than 10 percent since 2007–08. As shown in Figure 2, districts in Los Angeles County and Solano County, for example, have reduced their teacher workforce by a weighted average of 15 percent and 16 percent, respectively. (Only 2 counties—San Francisco and Mono—have increased their teacher workforce over this period.)

Districts Have Reduced Teacher Workforce in Several Ways. Districts have a few ways they can reduce their teacher workforce. In any given year, districts can rely on retirements and attrition, with some teachers voluntarily exiting the workforce and districts choosing not to backfill the associated positions. Districts also can be proactive in offering early–retirement incentives. Providing these incentives has been a common practice among districts in the past few years (with incentives offered by roughly 30 percent of districts). The early–retirement option allows districts to reduce the number of more senior, more expensive staff to save more entry–level jobs. In addition, districts can reduce their workforce by laying off staff—a practice that has become more common given recent budget reductions. From 2009–10 to 2010–11, the size of the teacher workforce declined by 7.7 percent. Though precise estimates are not available, retirements and layoffs likely accounted for roughly the same number of job losses, with attrition accounting for a relatively small number of losses.

Number of Layoffs Is Unknown. The CDE does not collect data on the number of teachers laid off each year. The OAH collects data on the number of districts conducting the layoff process each year. Information provided by OAH shows many districts are undertaking the layoff process—roughly one–third of districts issued layoff notices in 2010–11 and about 500 districts conducted layoffs in each of the previous two years. The bulk of districts responding to our survey reported undergoing the layoff process two or three times in the past four years. Data collected by CTA indicate that more than 20,000 initial layoff notices were issued statewide in 2010–11 for the 2011–12 school year, but no agency knows how many teachers statewide ultimately were laid off and not rehired.

Overview of Teacher Layoff Process

Layoff Process Largely Dictated by State Law. Districts have two options for structuring their teacher layoff process. The vast majority of districts use the state layoff process established in 1976. A few districts (6 percent) locally negotiate with their employee bargaining unit certain layoff processes per the Education Employment Relations Act (EERA) of 1975. Specifically EERA allows districts to negotiate layoff procedures for: (1) probationary teachers for any reason and (2) both probationary and permanent staff if the district lacks the funds to support the positions.

State Law Specifies Under What Conditions Districts Can Lay Off Teachers. Current law allows districts to lay off teachers in a few specified situations.

- Districts can lay off teachers if their student enrollment is declining. Layoffs resulting from declining enrollment are allowed either when a district's student count is below the previous two years or when an interdistrict student transfer agreement is terminated.

- State law also allows districts to lay off teachers if they can show that they need to reduce a "particular kind of service." Reductions in particular kinds of services (such as eliminating art programs or closing an elementary school) are almost always connected with budget reductions. Districts have some discretion in determining which service(s) or program(s) should be reduced or eliminated in order to balance their budget.

- In addition to these reasons, state law allows districts to lay off teachers due to a state–required curriculum modification, though teacher layoffs rarely are initiated for this reason.

State Law Also Prescribes Various Other Aspects of Layoff Process. Current law establishes the criteria districts are to use in determining which teachers to lay off. It also sets the time line in which districts are to make initial and final layoff decisions. Additionally, state law sets forth an administrative oversight process whereby OAH is to ensure districts are adhering to state layoff policies. Lastly, if circumstances improve for school districts—either they receive additional, unexpected revenues or experience higher–than–projected student enrollment—and they plan to add full–time equivalent staff as a result, then they are required to rehire teachers in seniority order from a list of laid off employees. Probationary teachers (first– and second–year teachers who have not yet received permanent status) stay on the "rehire" list for 24 months. Permanent teachers remain on the list for 39 months. The layoff process for teachers is different than layoff procedures for other public education employees as well as state–employed civil servants, as discussed in the nearby box.

Comparing Teacher Layoff Process With Process Used for Classified Staff and Civil Servants

Similarities. Some similarities exists in the procedures used to lay off teachers and those used for classified staff (noncertificated public education employees) and state–employed civil servants (state employees). For all three groups, the criteria used to determine who is to be laid off is the same: inverse seniority. Additionally, the state requires the employers of all three groups to provide substantial advance notice to employees—classified staff must be noticed 45 days and civil servants must be noticed 120 days prior to the effective layoff date.

Differences. While there are some similarities, teachers have additional protections that are not provided to other public employee groups. Though all must receive advance notice, classified staff and state employees can be laid off at any time throughout the year whereas school districts typically only can lay off teachers during the March–through–May period. The hearing and appeals process also varies for the three employee groups, with teachers receiving the greatest protections. Classified staff do not have the right to appeal layoff determinations (unless pursuing a formal grievance), and no state agency is required to oversee the school district's process in laying off classified staff. By comparison, state employees, similar to teachers, can challenge their seniority determinations through an appeal, but state employees are not granted a hearing automatically. The Department of Personnel Administration—the state agency that oversees civil servant layoff processes—investigates each appeal and determines whether it warrants a hearing. (Some state agencies have alternate layoff procedures that may provide different due process rights for state employees, though this depends on whether they have negotiated these alternate procedures in their collective bargaining agreements.)

Four Concerns With Existing Process. In reviewing the existing layoff process, we have four areas of concern relating to: (1) the time line for layoff notifications, (2) the hearing and appeals process, (3) the selection criteria for making layoffs, and (4) the extent of the state's involvement. The remainder of this report is dedicated to examining each of these issues in turn. We begin with the area for which we believe changes in state law could make the most immediate, significant improvement.

Time Line for Layoff Notifications

Current Law

Establishes Early Time Line for Notifying Teachers. School districts are required to determine the number of layoffs needed for a given school year and initially notify teachers who are to be laid off by the proceeding March 15. They also must confirm teachers receive the notice and are informed of their right to request a hearing. Two months later, by May 15, school districts are required to make official layoff decisions. In special circumstances, districts have one further avenue to lay off additional staff. Assuming a final state budget is passed around the beginning of the state's fiscal year (July 1), districts are able to initiate an accelerated layoff process if their revenue limit allocations do not increase by at least 2 percent from the previous fiscal year. This accelerated 45–day process—often called the "August layoff window"—must be complete by August 15. The August layoff window requires the same basic notification and hearing activities as the regular process but on an expedited time line.

Districts Significantly Overnotify

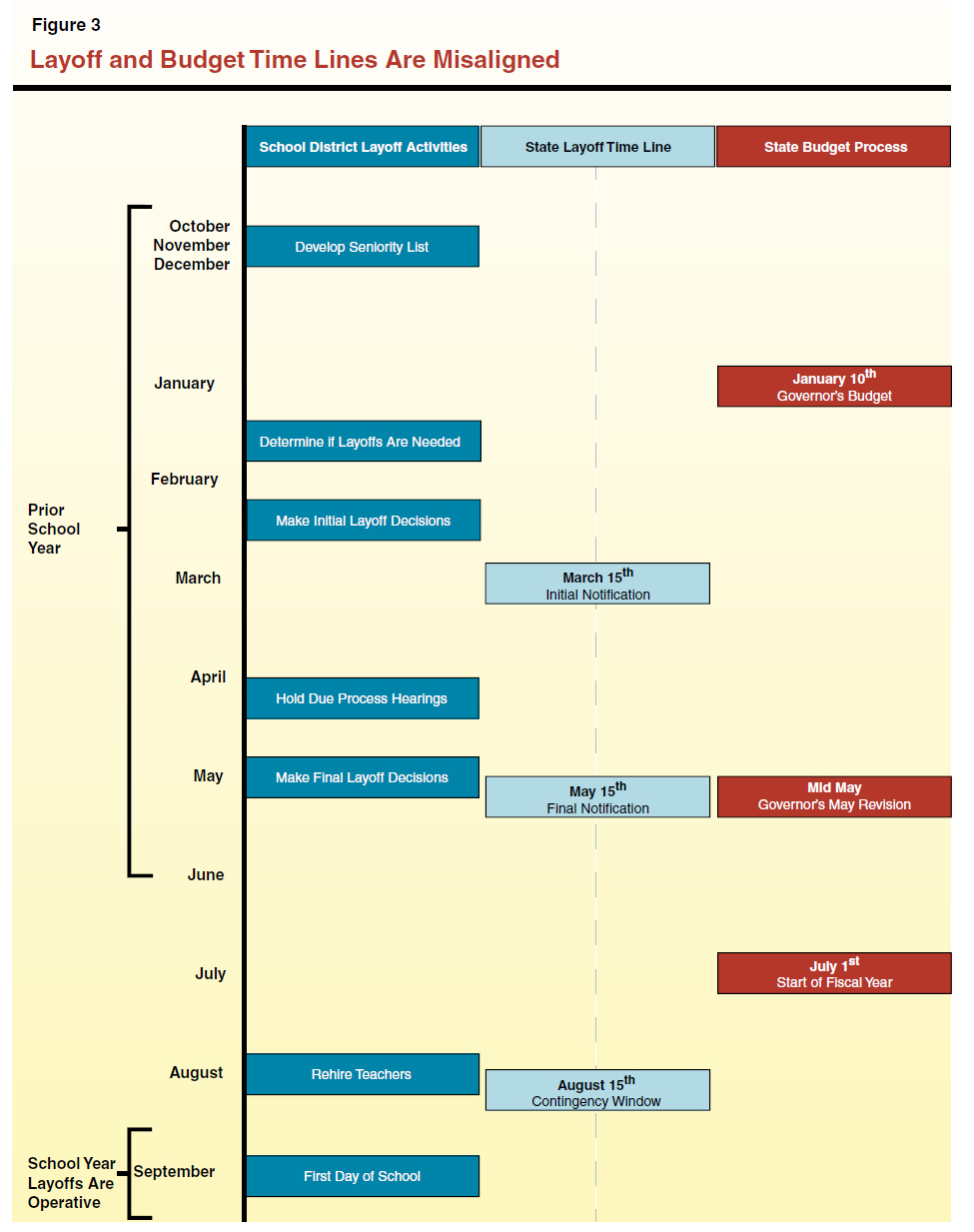

Layoff Deadlines Precede Key Budget Deadlines. School districts rely on information provided throughout the state budget cycle to build their local budgets for the following school year. Two key steps in the state budget cycle that influence districts' decisions are the Governor's January budget and May Revision (see Figure 3). Districts typically use the initial funding estimates in the Governor's January budget proposal to determine whether their existing program can be maintained moving forward. If state funding projections are such that districts believe they cannot sustain their current program into the following school year, then they can initiate the teacher layoff process. School districts must make their final layoff decisions about the same time as the May Revision—prior to the enactment of the state budget. Given the January budget proposal, May Revision, and final budget package can and often do dramatically differ, districts face a significant level of uncertainty in making staffing decisions for the coming fiscal year. Overall, the state layoff deadlines force districts to make layoff determinations too early without accurate fiscal information. Additionally, critical local information, such as the number of teachers that will leave the district or retire, is typically not available by the time school districts are required to make layoff decisions.

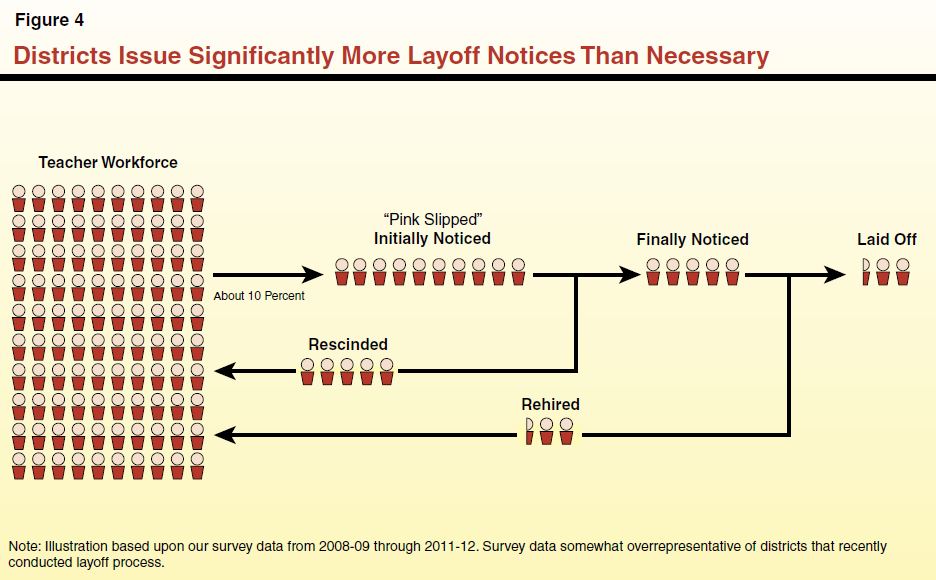

To Protect Against Budget Uncertainties, Districts Routinely Plan for More Layoffs Than Necessary. Primarily because of the uncertainty resulting from the misalignment between the state budget cycle, the state–imposed layoff deadlines, and the timing of critical local information, districts issue significantly more layoff notices than necessary. As shown in Figure 4, the number of teachers that are initially noticed far exceeds the number of teachers that are actually laid off for the following school year. Out of every ten teachers that are "pink slipped," roughly half are given final layoff notices and only two or three are not rehired prior to the beginning of the school year. Many districts either rescind almost all notices before the final notification deadline or rehire almost all staff after they receive final state budget information in the early summer months. While planning for more layoffs than necessary is a problem for school districts—particularly because it results in higher costs for each additional teacher noticed and morale problems for many teachers unnecessarily told they will lose their job—districts are essentially forced to overnotify so they can be assured of being able to balance their budget in the following fiscal year.

Contingency Layoff Window Is Not Particularly Helpful. In the past four years, the August layoff window has been available only once (2009–10). Though revenue limit allocations for school districts have not increased by more than 2 percent since 2008–09, state budgets enacted close to or after August prevented the window from opening in 2008–09 and 2010–11, and the state prohibited the layoff window from being used in 2011–12. Though this contingency option is designed to help districts balance their budgets in the summer if the final state budget differs significantly from the May Revision, it officially has been operative only a few times and has not been used widely.

Recommend Aligning Layoff Time Lines With State Budget Process

Move Layoff Deadlines Later in the Year. We believe the state–imposed layoff time line should be better linked with the availability of critical state and local fiscal information. Specifically, we recommend changing the time lines later in the year—to June 1 for initial layoff notices and to August 1 for final notices. Allowing districts to wait until a couple weeks after the May Revision to issue initial layoff notifications would significantly improve the quality of the fiscal information upon which districts base their decisions and decrease the number of notifications issued. This is because the May Revision offers much better information than the Governor's January plan given it is based upon updated state revenue estimates. Fewer initial notifications, in turn, would reduce the time and cost invested in conducting the layoff process, result in fewer teachers unnecessarily concerned about losing their job, and minimize the loss of morale in the school communities affected by layoff notices.

Balancing Needs of Districts and Teachers. Considerable trade–offs exist in setting new layoff deadlines. Establishing later deadlines means school districts have better fiscal information on which to make their layoff determinations, whereas setting earlier deadlines gives those teachers ultimately laid off more time to seek other employment opportunities. We believe a June 1 deadline for initial notification is reasonable because it attempts to balance these competing priorities—allowing districts to have relatively solid fiscal information prior to making initial layoff decisions, minimizing the overall number of teachers affected, and notifying laid off teachers before the end of the school year (in most districts) so they can have the summer months to seek alternate employment.

Provide Rolling Emergency Layoff Window. We recommend the Legislature replace the existing August layoff window with a rolling emergency layoff window. Unlike the current contingency option, we recommend establishing a "last–resort" window that districts can use at any point in the school year if the state makes significant budget changes. The window would require a district to notify teachers and complete due process activities within 45 days after a major state budget action. The 45–day emergency layoff window only would become available to districts if the state made significant budget reductions from the May Revision level. For example, we suggest allowing districts to use this window if the state makes reductions of 5 percent or more from the May Revision level.

New Rolling Emergency Window Also Balances Needs of Districts and Teachers. The state also faces important trade–offs when deciding whether to provide districts the ability to reduce staff midyear. On the one hand, allowing districts to reduce their staff throughout the school year could cause disruptions in the classroom for students and increase the difficulty laid off teachers have finding employment for the rest of the school year. On the other hand, if districts are faced with significant budget uncertainty, as they are in the 2012–13 budget cycle with potential trigger reductions, an emergency layoff window would allow them to reduce their staffing level if needed to ensure they remain solvent throughout the rest of the fiscal year. An emergency layoff window also would help districts reduce initial overnotification and layoffs by providing a subsequent opportunity for adjusting their staffing levels. Moreover, few other employee groups have similar types of protections from midyear layoffs—including other employee groups that also are entrusted with providing continuity in services.

Hearing and Appeals Process

Current Law

Noticed Teachers Have Right to a Hearing. Noticed probationary and permanent teachers have the right to a due process hearing if contesting a school district's initial layoff notice. Both the school district and teacher (or the local bargaining unit if it is legally representing that teacher) may present relevant information that supports each of their respective cases. Relevant information includes testimony or documentation that supports or disputes each teacher's start date, credential status, and any other information related to the criteria the district used to issue the preliminary layoff notice. The hearings are conducted by OAH's Administrative Law Judges (ALJ)—whose role we discuss in the following section. The hearings typically are held from April to early May and typically last from one to two days. The district is required to provide substitute teachers for all teachers that attend a hearing. While most districts' hearings last one or two days, hearings for larger districts with hundreds or even thousands of noticed teachers can take several weeks to conduct.

ALJ Oversees How Districts Implement State Layoff Policies. The OAH is a quasi–judicial agency that hears administrative disputes for state and local government agencies in California. In education, OAH is involved in addressing disputes relating to special education, teacher layoffs, and teacher dismissals (as one participant of a three–member panel). Its current role in the teacher layoff process is to review school districts' implementation of state layoff policy—ensuring policy is adequately applied and both school districts and teachers have an opportunity to present relevant information as well as review and dispute the other party's information. School districts are required to submit all applicable information (seniority list, governing board–approved resolutions on services that will be reduced, and tie–breaking and skipping criteria) to the ALJ and set up a hearing date with a preliminary estimate of the number of teachers that will be present at the hearing. The ALJ conducts the hearing and has until May 7 to provide its advisory recommendation to the school district's governing board regarding which teachers can be laid off legally. The governing board can then accept or reject the ALJ's recommendation, with the board required to implement final layoffs by May 15.

Process Adds Some Value but Is Costly

ALJ Provides Administrative Support and Oversight of District Actions. In implementing the state's layoff process, districts sometimes make mistakes. For example, districts can make mistakes identifying employee start dates, documenting teacher credentials or specializations, or interpreting state–allowable selection criteria. While certain mistakes, such as incorrect employee start dates and credential status, are administrative and easily corrected, more serious mistakes tend to occur when districts try to interpret state law regarding allowable selection criteria. Districts that are implementing this process for the first time tend to make more mistakes. In these cases, ALJ oversight tends to be more valuable in helping ensure that all teachers are laid off correctly. For those districts that have conducted this process for a number of years, such that they are highly experienced in building and maintaining their seniority list as well as their layoff criteria, the administrative oversight process takes considerably less time but still might be helping to ensure that state layoff law is implemented appropriately.

ALJ and School Districts Tend to Agree on Layoff Determinations. While districts do make some mistakes, the vast majority of them report that the ALJ's layoff recommendations are rarely or never different from their own initial layoff determinations. Furthermore, districts often meet with their local bargaining unit prior to or during the hearings to discuss relevant information and resolve mistakes, though this is highly dependent on the relationship between the districts and the local bargaining units. The vast majority of districts (95 percent) report resolving most of their mistakes prior to the hearings. In the cases wherein the majority of mistakes are worked out between the district and bargaining unit, the ALJ's oversight through the formal hearing does not add much value. For these districts, the hearings are an unnecessary investment of time and resources.

Administrative Process Is Costly. State law requires that school districts pay for the costs associated with laying off staff. Districts incur a variety of costs, including (1) notification mailings; (2) legal and AJL costs; (3) district personnel costs, such as time spent by human resources directors, support staff, and other administrators in preparing and implementing layoff activities; and (4) substitute costs to replace teachers that participate in hearings or other layoff activities (see Figure 5). Our survey indicates that districts on average spend roughly $700 per–noticed teacher, with the largest costs relating to district personnel and legal activities. In the layoff process held in 2010–11 for reductions in the 2011–12 school year, 370 districts issued over 20,000 initial layoff notices. With the costs estimates derived from our survey, we estimate that districts spent about $14 million statewide on layoff–related costs.

Recommend Streamlining Administrative Process

Eliminate Teachers' Right to a Hearing. The hearing aspect of the process does not add substantial value especially because mistakes on the seniority list could be resolved between all parties prior to the hearings. Conducting formal hearings to check factual mistakes—what happens in the majority of cases—is unnecessary and costly. We recommend the state eliminate teachers' right to a hearing but retain the ALJ's oversight in the process. Though we recommend eliminating formal hearings, we recommend the state establish a streamlined alternate process that ensures: (1) all relevant information is presented to the ALJ for review and (2) both parties have an adequate opportunity to review, comment upon, and dispute each other's information.

Would Lower Costs Especially for Larger Districts, Increase Efficiencies Overall. While some of the costs associated with the layoff process are unavoidable (such as district personnel costs associated with developing the seniority list), conducting hearings adds unnecessary costs and consumes considerable staff time (both for district and union personnel). Eliminating hearings would increase the efficiency of the layoff process while maintaining the oversight needed to ensure teachers are laid off correctly according to state law. For larger districts, whose hearings can last for weeks, the potential time and cost savings of eliminating hearings are substantial. For medium and smaller districts, that typically conduct hearings lasting one or two days, associated time and cost savings would be less but still reflect some fiscal relief.

Selection Criteria

Current Law

Inverse–Seniority Order Is Required, Results in a Last–Hired, First–Fired Policy. State law requires that districts lay off teachers in inverse seniority order. That is, the last teachers hired in the district—those having the least seniority—are first to be laid off. The state also specifies that no junior employee can be retained if a more senior employee is "certificated or competent" to teach in that position. For example, a district may decide to eliminate its physical education program but all teachers working within that program might not be laid off. If one of those teachers is more senior and credentialed to teach in any other subject, for example math, he or she can replace a junior employee whose math position was not being considered for elimination. This practice is commonly known as "bumping," whereby more senior employees bump junior employees down the seniority list because the senior teacher is able to teach a junior teacher's course.

Districts Currently Have Some Discretion to Deviate From Seniority Order. Though the state requires inverse–seniority order as the primary criteria for laying off staff, it allows districts to deviate from seniority for three specified reasons.

- If two or more employees started with the district on the exact same date, the district has the right to develop standard criteria solely based on the district's and students' needs.

- If the district demonstrates a need for specialized services that require a specific course of study, special training or experience (such as special education or speech pathologists), it may develop a system that gives higher priorities to teachers with these credentials or types of experience.

- The state also allows deviating from seniority for "maintaining or achieving compliance with constitutional requirements related to equal protection of the laws."

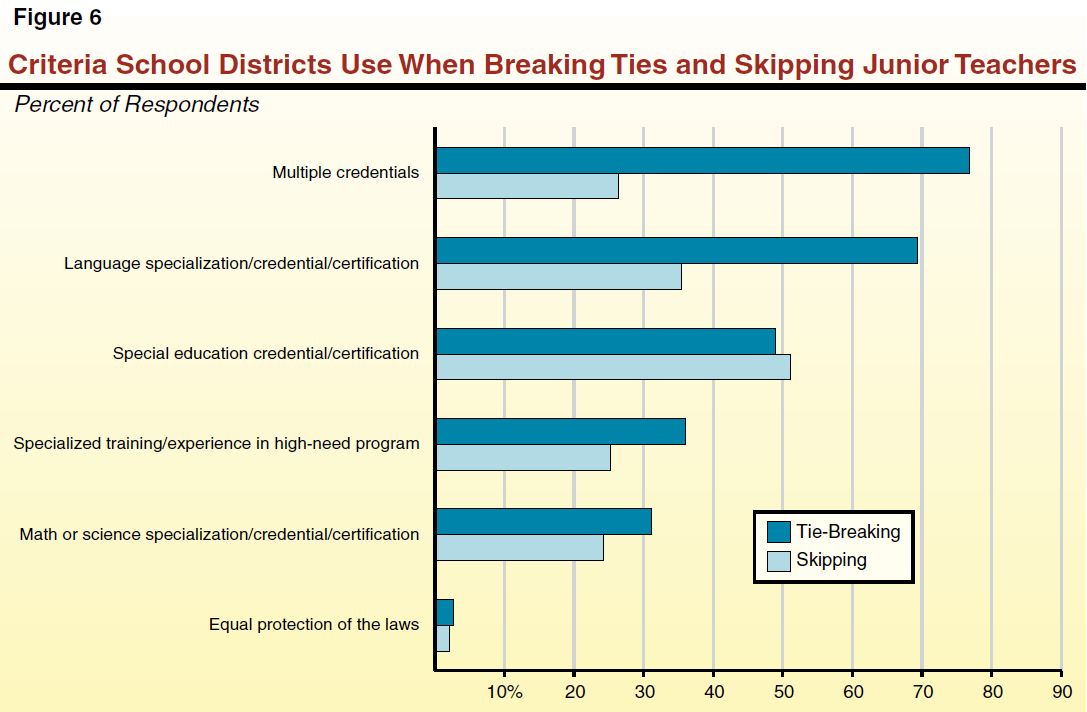

Breaking Ties Amongst Employees With the Same Start Date. Virtually all districts must break ties amongst employees—especially because districts often must focus on groups of employees that started around the same time. Some districts use random number assignment to decide which employees with the exact same start date will be laid off. The majority of districts, however, use more refined criteria. As shown by the dark bars in Figure 6, our survey indicates districts commonly break ties by retaining teachers who have multiple credentials and/or a language specialization.

Skipping Specialized Junior Employees. The majority of districts in our survey also report developing criteria to "skip" junior teachers with specialized credentials or experience. State law allows school districts to retain certain junior employees if the district can prove certain types of trained and experienced teachers meet a specific need within the district. The most common types of teachers protected under this skipping criteria are special education teachers and language specialists (see the light bars in Figure 6). Whereas almost all survey respondents develop tie–breaking criteria (94 percent), about two–thirds of survey respondents deviated from seniority to skip junior employees.

Using Equal Protection Clause. Chapter 498, Statutes of 1983 (SB 813, Hart), amended the original 1976 teacher layoff statute to allow districts to deviate from seniority–based layoffs "for purposes of maintaining and achieving compliance with constitutional requirements related to equal protection of the laws." When this clause was added, the provision was intended primarily to "ensure that the teaching force reflects the multicultural makeup of the state." Since Proposition 209 (approved by voters in 1996) constitutionally banned discrimination against or preferential treatment of any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in public employment—including public education employment—a district no longer can skip certain teachers during the layoff process in an effort to maintain cultural diversity.

More Recent Interpretation of Equal Protection Clause. Districts recently have begun to use the equal protection provision to skip certain teachers employed at certain schools serving disadvantaged students. In some instances, seniority–based layoffs result in some schools laying off a significant proportion of their teachers. Some public advocates have raised concern that such high proportions of layoffs in these schools, coupled with other educational disadvantages, cause major disruption for students and the quality and continuity of their education program—threatening students' equal protection of the laws.

Few Applications of Clause to Date. Of the districts we surveyed, very few report exploring their discretion to deviate from seniority for the purpose of equal protection of the laws. Only five districts reported having used this discretion in developing criteria to break ties amongst employees with the same start date. Another four reported developing skipping criteria for this purpose. For layoffs operative in the 2012–13, one district to date has ventured in this direction. San Francisco Unified School District (SFUSD) recently conducted their first round of layoff determinations and used the equal protection clause to protect junior teachers in 14 schools they classify as having high–need students with low academic performance. (The ALJ will review whether SFUSD adequately implemented state layoff law in the coming weeks.)

State Values Seniority in Layoff Process

Some Benefits to Using Seniority to Determine Layoffs . . . Using seniority on a statewide basis for laying off staff has some benefits. Seniority is an objective, standard approach that is transparent and easy to implement. All parties involved clearly know what information is used to make layoff determinations. Disagreements can be based only on factual errors—for example, a district and employee disputing the day the employee officially started paid service with the school district. Seniority also can serve as a rough proxy for teacher quality, with first– and second–year teachers less effective, on average, than more experienced teachers.

. . . But Seniority Has Significant Drawbacks. Using seniority, however, has a number of significant drawbacks. Basing employment decisions on the number of years served instead of employees' productivity and performance can lead to lower quality of the overall teacher workforce. State law allows school districts to adopt layoff practices that are in the best interest of students only when breaking start–date ties amongst employees. In all other cases, state law values the protection of teachers who have served the district for many years and ignores how well teachers have served. While it is generally true that newer teachers are less effective than more experienced teachers, not all new teachers are the least effective. In fact, the few academic studies done on comparing layoffs based on performance rather than on seniority show little overlap exists between the teachers who would be laid off under strict performance criteria versus seniority criteria. The current seniority–based layoff policy also causes disruption in schools. As we previously mentioned, senior employees are able to bump junior employees at different school sites and in different positions. Because of this, position eliminations in one school usually affect a number of school communities and can disrupt staff teams throughout the district.

California State Law Is More Prescriptive Than Many Other States. Whereas 33 states allow their local education agencies (LEAs) to develop their own layoff criteria, California—along with 13 other states—prescribe seniority as the primary criteria districts must use to lay off personnel. In contrast, three states (Arizona, Colorado, and Oklahoma) require their LEAs to include teacher performance as a factor in making layoff determinations.

Recommend Exploring Alternatives to Seniority–Based Layoff Criteria

Explore Alternatives. Given the limitations of using seniority as the primary factor in layoff determinations, we recommend the state explore alternatives that could provide districts with the discretion to do what is in the best interest of their students. Ideally, districts would use multiple factors in making layoff determinations—factors that result in the least harm to students, the overall teaching workforce, and the school community. Some alternative factors districts could consider are: student performance, teacher quality, classroom management, teacher attendance and truancy, leadership roles, contributions to school community, and degrees and specializations. Consideration of such factors would help school districts retain their highest quality teachers.

Virtually All of These Alternatives Currently Are Impractical. Many of these factors could be considered at both the local and state level, but their statewide application currently is impractical. This is because districts have varying capacities to maintain information on many of these factors, with teacher evaluation and data collection practices varying throughout the state. Whereas some districts have robust data and evaluation systems that could enable them to use performance evaluations objectively and fairly in making important personnel decisions, many districts do not have such well–developed systems. Moreover, the state only collects information on a few of these factors and some data collections (such as contributions to school community) ultimately might be impractical for the state to pursue. Student performance data, on the other hand, already are collected at the state level and teacher quality data could be pursued with statewide benefits beyond providing information to improve the teacher layoff process (such as better investment of the state's professional development funds and evaluation of teacher preparation programs).

Finding Better Statewide Indicators for Teacher Quality as an Alternative to Seniority. If the state could more confidently rely on teacher quality information from districts, it might be able to move in the direction of an improved statewide teacher layoff process using teacher quality as the primary criteria for layoff determinations. The state could play a key role in helping districts develop reliable teacher quality information. Specifically, it could encourage CDE to collect and disseminate district best practices on evaluating teacher performance. Sharing best practices information from districts that have pioneered work in this area likely would have long–term benefits for many school districts that currently do not have the capacity to evaluate their teachers robustly.

State Involvement in Local Layoff Decisions

Current Law

State Assertive in Teacher Layoff Policy and Other Local Personnel Matters. Given that very few districts have negotiated layoff terms in their teachers' contracts, the state layoff process has become the de facto policy for the majority of school districts. As described in the overview section, the state prescribes the conditions under which districts can lay off staff, when they must notice staff, the criteria they must use in determining who to lay off, and lastly how they must rehire teachers if their financial or enrollment circumstances improve. The state's role in layoff policy is not an exception. The state also asserts a relatively strong role in other local personnel matters, including teacher assignments, compensation, and credentialing. In layoff policy, California is somewhat more prescriptive than other states, with the majority of states allowing districts more latitude in making layoff determinations.

State Law Contains Both State and Local Protections for Teachers. While the state plays an assertive role in establishing a uniform statewide layoff policy, it also provides protection of teachers' rights at the local level. The EERA established teacher layoff policy as a mandatory negotiable topic under certain circumstances. That is, a school district and local bargaining unit must engage in good–faith negotiations and mutually agree on procedures and criteria before a district can initiate a locally designed layoff process. School districts and teacher unions largely have deferred to the state layoff process, which provides significant protections for teachers, but state law is designed to protect teachers whether the state process or a locally developed process is used.

Difficult Trade–Offs in Deciding State Role

State Involvement Helps Provide Uniform System. Determining personnel policies at the state level can ensure that all school districts adhere to a uniform set of rules. Currently, the state's layoff policy can help ensure that districts do not make layoff decisions that are arbitrary. State law also requires school districts to use only objective criteria when breaking ties, skipping, and bumping teachers.

State Control Might Be Unnecessarily Restrictive. By having a one–size–fits–all layoff policy, the state, however, could be unnecessarily restraining districts from crafting better practices suited for their particular teacher and student populations. Given that EERA provides protection of teachers' rights regarding layoffs through the collective bargaining process, the state's policy may be unnecessarily restrictive. Consequently, it could be preventing more frequent and thoughtful negotiations on this topic at the local level. Moreover, it is not clear that a state–imposed process is necessary to prevent undesired local district behavior. Some of the state's primary goals in the layoff process are to prevent teachers from being unnecessarily laid off, provide teachers with early information, and protect students from midyear disruptions. These state values appear closely aligned with district goals in building their education program. Currently, districts have strong incentives not to take disruptive midyear actions that would negatively impact their students—including laying off teachers and shuffling students to different classes while the school year is in progress.

Recommend Exploring Other Options

Carefully Assess Trade–Offs Between State Involvement and Local Flexibility in Personnel Matters. The state faces difficult trade–offs in deciding how involved it should remain in local personnel matters. If the state retains its current prescriptive role, it can help ensure that districts do not make layoff decisions that are arbitrary, biased against individual teachers, or based upon political or personal motivations. On the other hand, the state recently has moved in the opposite direction in a number of areas, including education. In February 2009, the state removed many requirements associated with education categorical programs. Further moving in this direction, the Governor this year has proposed fundamentally restructuring how the state funds schools and providing districts significantly more flexibility and local discretion in structuring their education programs. The state also recently has shifted certain state responsibilities to counties and cities in a number of other areas of the state budget, including criminal justice, mental health and substance abuse programs, foster care, and child welfare services. Along with these fundamental changes to the services the state provides and the requirements it chooses to impose on local governments, we recommend the Legislature carefully reassess the need for and benefits of its current prescriptive role in school district personnel matters.

Consider Expanding Locally Negotiated Options. In addition, we recommend the state consider expanding locally negotiated options under EERA to allow school districts and local bargaining units to negotiate the entire layoff process for any certificated staff under any applicable circumstance. Because EERA is somewhat restrictive in allowing districts and unions to negotiate the layoff process in only limited circumstances, districts and unions currently might be deterred from taking the time and effort to establish their own layoff procedures. That is, under current law, if districts did collectively bargain layoff procedures in the few allowable areas, they likely would be required to implement one set of layoff procedures in those areas and the state set of layoff procedures in all other cases. Negotiating such a bifurcated process is unnecessarily complicated. Districts and unions could avoid this complication if allowed to negotiate the layoff process for all applicable situations.

Summary

Figure 7 summarizes our major findings and recommendations.

Figure 7

Summary of LAO Findings and Recommendations

|

Layoff Provision

|

Current Law

|

Finding

|

Recommendation

|

|

Time Line for Layoff Notifications

|

- Requires initial layoff notifications to be distributed by March 15 and layoffs to be implemented by May 15.

|

- Districts significantly over notify.

- "Contingency" layoff window in August is not particularly helpful.

|

- Authorize June 1 as deadline for initial notifications and August 1 for final layoffs.

- Provide a rolling, 45–day emergency layoff window.

|

|

Hearing and Appeals Process

|

- Requires administrative oversight of districts' implementation of state layoff policy and provides teachers the right to a hearing.

|

- Teachers receive more protections than other public employee groups.

- Administrative process for laying off teachers adds some value but is costly.

|

- Replace teachers' right to automatic hearing with a streamlined alternate process that ensures: (1) all relevant information is presented to the Office of Administrative Hearings for review and (2) both district and bargaining unit have opportunity to review information.

|

|

Selection Criteria

|

- Requires inverse–seniority order, resulting in a last–hired, first–fired policy.

- Allows districts some discretion to deviate from seniority order.

|

- The selection criteria specified in California state law is more prescriptive than many other states.

- State values seniority more than alternative criteria in layoff process.

|

- Explore alternatives to seniority–based layoffs.

- Encourage California Department of Education to collect and disseminate district best practices on evaluating teacher performance.

|

|

State Involvement

|

- Leads to state involvement in virtually all districts' layoff practices.

- Contains both state and local protections for teachers.

|

- State involvement might be ensuring fair and uniform system, but it also might be unnecessarily restrictive.

|

- Assess trade–offs between state involvement and local flexibility in personnel matters.

- Consider expanding locally negotiated options.

|

Recommendations Could Provide Immediate Benefits . . . Though initial notices already have been sent to teachers who might be laid off for the coming school year, some of our recommendations could improve the process almost immediately. Though the March 15 date has passed, the Legislature could consider moving the final notification date from May 15 to our recommended date of August 1. This would give districts the benefit of having information on the final state budget package prior to finalizing their layoff decisions. Moreover, if the Legislature adopted our recommendation to replace the August layoff window with a rolling emergency window, school districts might find that they could lay off fewer teachers now—knowing that a post–election window subsequently could be available.

. . . And Lasting Benefits. Though some of our recommendations could provide immediate benefits, our package of recommendations is designed to improve the layoff process on a lasting basis. As many districts continue to experience declining enrollment, some districts continue to face fiscal difficulties, and the economy continues to experience booms and busts, teacher layoffs will remain a common issue of concern in the coming years. By changing notification deadlines, streamlining the administrative oversight process, and exploring alternatives to seniority–based layoffs, we believe the state would improve the existing layoff system significantly. Furthermore, we think the overall education system could benefit moving forward from a reassessment of the state's role in local personnel matters, with the state dedicating its efforts to those limited areas in which school districts lack sufficiently strong incentives to uphold statewide public values.