For the third consecutive year, we distributed a survey to all California public school districts to gather information that could help the Legislature in crafting the state's education budget for the coming year. The survey, distributed in January 2012, asked a range of questions about districts' responses to recent budget reductions, flexibility policies, and funding deferrals, as well as their budgeting approaches for 2012–13.

Districts Have Implemented Notable Reductions in Recent Years. Despite an influx of short–term federal aid and state interventions to minimize cuts to K–12 education, school district expenditures dropped by almost 5 percent between 2007–08 and 2010–11. Districts reduced spending by between 1 percent and 3 percent each year, spreading federal funds and reserves across years to moderate the 6 percent drop in revenues that occurred in 2009–10. Moreover, data suggest districts actually have cut programs even more deeply in order to accommodate increasing costs associated with local teacher contract provisions and health benefits contributions. Given certificated staff represent the largest operational expense in school budgets, this area is unsurprisingly where most reductions have been focused. Districts achieved some of these savings by reducing their workforce (across all employee groups) and making corresponding increases to class sizes. Additionally, districts instituted staff furloughs and made corresponding decreases to both student instructional days and staff work days.

Categorical Flexibility Continues to Be Important for Districts. To provide school districts more local discretion for making programmatic reductions, in February 2009 the Legislature temporarily removed programmatic and spending requirements for about 40 categorical programs and an associated $4.7 billion. As in our prior surveys, districts continue to indicate this flexibility has facilitated their local budget processes, and most districts continue to redirect the majority of funding away from most flexed categorical programs to other local purposes. An increasing number of districts, however, report that the current categorical flexibility provisions are not sufficient to ameliorate continuing year–upon–year funding reductions and cost increases. Our survey respondents indicate that new flexibility for the categorical programs that remain restricted would help them manage budgetary uncertainties in 2012–13 as well as accommodate potentially deeper reductions. In addition to seeking more near–term flexibility, the vast majority of districts indicate they would like the state to eliminate many categorical programs on a lasting basis.

Districts Planning for Challenging Budget Situation in 2012–13. In addition to constrained resources, districts face the additional challenge of budgeting for the upcoming school year without knowing whether voters will approve a revenue–generating ballot measure in November. While the Governor's state budget proposal includes these potential revenues (and corresponding midyear trigger reductions were the voters to reject his tax measure), the vast majority of districts plan to take a more cautious approach. Specifically, because districts have a difficult time making large reductions midway through the school year, almost 90 percent of our survey respondents plan to wait for the results of the November election before spending the potential tax revenue. Districts request that the Legislature maximize local flexibility and provide them greater latitude to manage reductions at the local level. Specifically, were additional state funding reductions to be necessary, districts hope the state focuses them on restricted programs and activities while avoiding additional cuts to their unrestricted funding (such as revenue limits). Restoring state funding deferrals also is a high priority for districts, as a rising number have had to borrow or make cuts to accommodate these delayed state payments, and our survey suggests even more would do so were the state to implement additional deferrals in 2012–13.

Recommend Legislature Take Immediate Actions to Help Districts Manage Budget Uncertainty . . . We recommend the Legislature increase the tools available for districts to balance the dual objectives of preparing their budgets during uncertain times and minimizing detrimental effects on districts' educational programs. Because districts will only take advantage of these tools if they are sure they can count on them when they adopt their budgets this summer, we recommend these changes be part of the initial budget package and take effect July 1, 2012. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature: (1) remove strings from more categorical programs, (2) adopt a modified version of the Governor's mandate reform proposal, (3) reduce instructional day requirements, (4) change the statutory deadlines for both final and contingency layoff notifications, and (5) eliminate statutory restrictions related to contracting out and substitute teachers.

. . . And Initiate Broad–Scale Restructuring of K–12 Funding System. We also recommend the state immediately begin laying the groundwork for a new K–12 funding system. Our survey findings reaffirm how recent categorical flexibility provisions have fundamentally shifted the way districts use funds at the local level and how disconnected existing program allocations have become from their original activities and populations. Whether the state adopts a version of the Governor's weighted student funding formula or instead opts to allocate funds based on a few thematic block grants, we recommend the Legislature initiate the new funding system now, phasing in changes over several years to give districts time to plan and adjust. To ensure the state can appropriately monitor student achievement and intervene when locally designed efforts are not resulting in desired outcomes, we also recommend the Legislature refine its approach to school accountability in tandem with changes to the school funding system. A more robust accountability system would include improvements such as vertically scaled assessments, value–added performance measures based on student–level data, a single set of performance targets, and more effective types of interventions. As a new approach to K–12 funding is being phased in, the state could maintain some spending requirements—particularly for disadvantaged students—and then remove those requirements once an improved accountability system has been fully implemented.

For the third consecutive year, we distributed a survey to all California public school districts to gather information that could help the Legislature in crafting the state's education budget for the coming year. The survey, distributed in January 2012, asked school districts about the effects of recent state actions on their budgets and operations. In this report, we (1) give an overview of our survey, (2) discuss our major findings, and (3) provide the Legislature with recommendations to help districts manage budget uncertainty in the coming year as well as improve the overall K–12 funding system on a lasting basis. The report also includes an appendix that contains a complete listing of this year's survey questions and results.

Survey Asks About Districts' Recent Actions and Future Plans. As in 2010 and 2011, our 2012 survey was completed by district superintendents or chief budget officers. This year's survey asked a range of questions about districts' responses to recent budget reductions, flexibility policies, and funding deferrals, as well as their budgeting approaches for 2012–13. To supplement our survey data, we also reviewed fiscal and demographic information from other sources—obtaining data on certificated and classified staff from the California Basic Educational Data System and on school district revenues and expenditures from the Standardized Account Code Structure database.

Survey Respondents Representative of State. Out of about 950 districts statewide, 467 responded—the highest number of respondents in the three years we have conducted the survey. We received responses from eight of the ten largest school districts. In total, the districts that responded to our survey represent 67 percent of the state's average daily attendance. Figure 1 lists several demographic factors and compares our survey respondents with the statewide average. As shown in the figure, the districts that responded to our survey closely mirror the socioeconomic composition of all students in the state.

Figure 1

Survey Respondents Representative of the State

|

Student Characteristics

|

Percent of Student Population

|

|

Survey Respondents

|

Statewide Total

|

|

Latino enrollment

|

51%

|

50%

|

|

White enrollment

|

25

|

27

|

|

Asian enrollment

|

9

|

9

|

|

African–American enrollment

|

7

|

7

|

|

FRPM participation

|

58

|

57

|

|

English Learners

|

24

|

24

|

Our survey asked a number of questions about districts' practices in recent years, as well as their plans and preferences for 2012–13 and future years. Below, we present our findings in three main areas. The first group of findings relates to the manner and timing in which districts have implemented recent budget reductions. The next group relates to categorical flexibility—focusing on how districts have treated particular programs given recent flexibility provisions and how districts would like the state to treat remaining categorical programs moving forward. Finally, we present survey responses related to how districts are preparing their 2012–13 budgets.

Districts Have Implemented Notable Reductions in Recent Years

During the recent economic downturn, both the federal and state governments have taken steps to mitigate programmatic reductions in California schools. Specifically, the federal government provided $7.3 billion in one–time school aid for 2008–09 through 2011–12 (including $6.1 billion from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and $1.2 billion from the Federal Education Jobs Act). The state also has avoided deeper cuts to K–12 programs by relying heavily on payment deferrals (which authorize school districts to support operations through short–term borrowing in lieu of making reductions). Despite these interventions, school districts have experienced a number of reductions to their K–12 programs over the past several years. This section describes some ways in which districts have implemented these reductions.

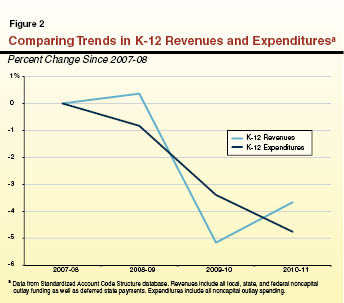

Whereas Funding Dropped Steeply in One Year, Districts Have Been Reducing Their Programs More Gradually Over Last Few Years. Figure 2 compares the percentage change in K–12 revenues to K–12 expenditures since 2007–08. The figure shows that while districts experienced the most severe drop in revenues between 2008–09 and 2009–10 (6 percent), they reduced spending at a more moderate pace across the period (1 percent to 3 percent each year). Specifically, districts appear to have spread one–time monies (including federal aid as well as certain freed–up reserves) strategically across the 2008–09 through 2011–12 period to help mitigate reductions.

Since Recession Hit, Districts Have Reduced Spending by Almost 5 Percent Per Pupil. Figure 3 provides additional detail on how K–12 expenditures have changed over the past four years. Total expenditures (excluding capital outlay projects) dropped by $3.3 billion between 2007–08 and 2010–11, which equates to a statewide average reduction of $565, or 4.7 percent, per pupil. (While statewide data are not yet available for 2011–12, our survey responses indicate about half of districts made additional reductions to per–pupil expenditures in the current year.) The figure shows the most significant spending change has been to certificated staff salaries—the largest operational expense in district budgets. Certificated salary expenditures have decreased by $2.3 billion, including a $1.4 billion drop between 2008–09 and 2009–10. As discussed below, districts have reduced these costs both by employing fewer teachers and administrators and by having them work fewer days. Districts also significantly reduced the amount they spent on books and supplies, dropping these expenditures by $1 billion, or 22 percent, across the four years. Spending on employee benefits notably remained constant across the period, even as districts employed fewer staff.

Figure 3

School District Expenditures Decreasinga

|

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

|

Expenditures (In Billions):

|

|

Certificated salaries

|

$27.5

|

$27.4

|

$26.0

|

$25.2

|

|

Classified salaries

|

10.3

|

10.3

|

10.0

|

9.7

|

|

Employee benefits

|

11.3

|

11.4

|

11.5

|

11.5

|

|

Subtotals—Salaries and Benefits

|

($49.2)

|

($49.1)

|

($47.5)

|

($46.4)

|

|

Books and supplies

|

$4.5

|

$3.7

|

$3.3

|

$3.5

|

|

Otherb

|

17.1

|

17.4

|

17.6

|

17.5

|

|

Totals

|

$70.7

|

$70.1

|

$68.3

|

$67.4

|

|

Per–Pupil Expenditures (In Dollars)

|

$11,892

|

$11,773

|

$11,516

|

$11,327

|

|

Year–to–year percent change

|

—

|

–1.0%

|

–2.2%

|

–1.6%

|

|

Percent change from 2007–08

|

—

|

–1.0

|

–3.2

|

–4.7

|

Districts Have Made Deeper Programmatic Reductions to Offset Increasing Costs. While Figure 3 shows steady decreases to several areas of district spending, our survey responses and state workforce data suggest that reductions to K–12 programs have been even greater than these data suggest. This is because districts frequently have structured teacher contracts in such a way that they face automatic cost increases each year, and therefore must cut programs just to maintain the same spending levels. For example, most districts provide annual "step–and–column" adjustments that automatically increase employee salaries for each additional year of experience or level of professional education. Only 6 percent of our survey respondents report having stopped this practice in recent years. Additionally, the costs of providing employee health benefits have increased by an average of 6 percent each year. The subsequent paragraphs in this section detail the ways in which districts have reduced K–12 programs to help accommodate the combination of these cost pressures and overall decreases in funding.

Many Districts Now Employ Fewer Teachers . . . Figure 4 provides detail on district staffing levels. The state's teacher workforce decreased by 11 percent (about 32,000 teachers) between 2007–08 and 2010–11. The most significant decline occurred in 2010–11, with a 7.7 percent—or 22,000 position—decrease compared to the prior year. Retirements and layoffs each accounted for roughly half of these job losses in 2010–11. Regarding retirements, our survey data indicate that roughly 30 percent of districts provided certain fiscal incentives—often referred to as "Golden Handshakes"—in 2009–10 and 2010–11 to encourage teachers to retire early. Regarding layoffs, about half of all districts issued notices in March of 2009 and 2010 in preparation to lay off teachers for the 2009–10 and 2010–11 school years. Fewer districts (only about one–third) issued notices in March 2011 to lay teachers off for the 2011–12 school year.

Figure 4

Districts Have Reduced Staffing Levelsa

|

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

Percent Change 2007–08 to 2010–11

|

|

Teachers

|

300,512

|

298,960

|

291,028

|

268,495

|

–11%

|

|

Full–time classified staff

|

158,080

|

158,033

|

153,749

|

148,598

|

–6

|

|

Part–time classified staff

|

136,122

|

145,574

|

144,247

|

142,996

|

5

|

|

Pupil support service providersb

|

27,629

|

27,343

|

23,458

|

23,666

|

–14

|

|

Administrators

|

25,687

|

25,095

|

23,159

|

21,602

|

–16

|

. . . And Fewer Administrators and Support Staff. Along with reducing their teacher workforce, school districts also now employ fewer full–time classified staff, pupil support service providers, and administrators compared to previous years. Figure 4 shows that since 2007–08, districts reduced pupil support providers (which include certificated staff such as counselors or speech therapists) by 14 percent and administrators by 16 percent—the largest proportional reductions of all education employee groups. In contrast, districts have made lesser reductions to their classified workforce over the same time period, instead appearing to generate savings by shifting to a greater dependence on part–time staff (who cost less because they typically do not qualify for benefits). Specifically, the full–time classified workforce decreased by 6 percent whereas part–time classified staff increased by 5 percent since 2007–08.

Some Districts Also Have Cut Back on Some Salary Increases and Benefits. In addition to employing fewer staff, some districts have achieved savings in recent years by changing employee contracts. Prior to 2008–09, districts typically included annual cost–of–living adjustments (COLAs) in their contracts, usually commensurate with whatever COLA the state budget provided. Mirroring the lack of state–funded COLAs in recent years, fewer than one–fifth of districts report providing teacher COLAs after 2008–09. (While our survey asked only about teacher contracts, districts likely employed similar practices for classified and other certificated staff.) A smaller but increasing share of districts also report reducing employer contributions to employee health benefits (17 percent in 2011–12).

Average Class Sizes Have Increased. To accommodate the reduction in teacher workforce, districts have had to increase the number of students in each classroom. As shown in Figure 5, average class sizes have increased in all grade levels since 2008–09. The largest increase occurred between 2008–09 and 2010–11, with average Kindergarten through third grade class sizes growing from 23 to 26 students, and all other grade levels increasing by an average of one to two student per class. The majority of school districts maintained these same levels in 2011–12.

Figure 5

Average Class Sizes Are Increasing

|

Grade

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

|

Kindergarten

|

23

|

24

|

26

|

26

|

|

Grades 1–3

|

23

|

25

|

26

|

26

|

|

Grades 4–6

|

30

|

30

|

31

|

31

|

|

Grades 7–12

|

30

|

31

|

32

|

32

|

Many Districts Have Instituted Furloughs . . . In addition to employing fewer staff, a large number of districts have achieved salary savings by cutting back on staff work days through instituting furloughs, or unpaid days, into staff contracts. Furlough days were exceptionally rare in California districts prior to 2009–10, but 60 percent of districts report they instituted an average of three furlough days in 2010–11. Slightly fewer districts report instituting furlough days in the current year—half of districts instituted an average of two days.

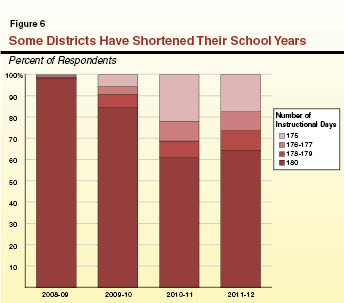

. . . Reducing Both Instructional and Staff Development Days. Furloughs can result in decreases to either student instructional days or staff development days, or both. As shown in Figure 6, our survey indicates that many districts have reduced the number of instructional days. In 2008–09, almost all districts (98 percent) provided at least 180 instructional days per year. By 2010–11, that proportion dropped to only 61 percent, with about one–fifth of districts providing between 179 and 176 days, and about one–fifth having decreased to the statutory minimum of 175 days. Most districts maintained their shorter school years in 2011–12. (The 2011–12 budget package allowed districts to reduce the school year to 168 days since midyear "trigger" cuts were implemented. Our survey data, however, indicate districts did not take advantage of this option.) At least one–third of districts indicate they also have decreased noninstructional staff work days since 2008–09.

Categorical Flexibility Continues to Be Important for Districts

To provide school districts more local discretion for making programmatic reductions, in February 2009 the Legislature temporarily removed programmatic and spending requirements for about 40 categorical programs and an associated $4.7 billion. This flexibility, currently scheduled to expire in 2014–15, allows districts to use funding originally restricted for these programs for any educational purpose. For 2012–13, the Governor proposes to extend flexibility to seven additional programs and to make this local discretion permanent (as part of a larger restructuring of the K–12 funding system). This section describes district perspectives on categorical flexibility, both for the near term and for the future.

Flexibility Continues to Be a Helpful Tool for Districts, but Budget Reductions Becoming More Difficult to Manage. As in our prior surveys, districts continue to indicate that categorical flexibility has facilitated their local budget processes. In particular, the vast majority of districts (roughly 90 percent) report that categorical flexibility has made it easier to develop and balance a budget and dedicate resources to local education priorities. However, district responses regarding how flexibility has affected certain other key decisions were somewhat different in this year's survey. For example, comparing survey responses from last year with this year reveals that a smaller percentage of districts indicate categorical flexibility has helped them to develop and implement a strategic plan (84 percent in 2010–11 compared to 67 percent in 2011–12) and fund teacher salaries (79 percent compared to 64 percent). This suggests that, for a growing number of districts, fiscal challenges are becoming increasingly difficult to manage. That is, while initially very helpful, the current categorical flexibility provisions are not sufficient to ameliorate continuing year–upon–year funding reductions and cost increases.

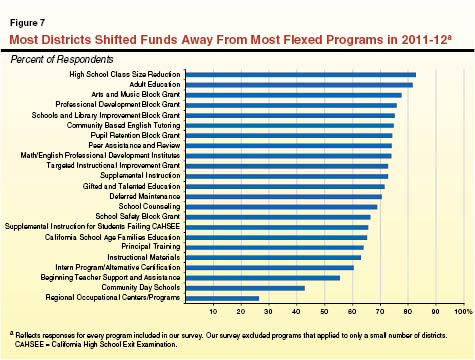

Districts Continue to Shift Funding Away From Flexed Categorical Programs. As shown in Figure 7, most districts continue to shift at least some funding away from every major flexed categorical program. For example, at least 75 percent of districts report diverting funding away from high school class size reduction (CSR), adult education, arts and music, professional development, school and library improvement, and the Community Based English Tutoring program. The trend of shifting flexed funds away from their original programs has been evident in all three years of our survey, and generally seems to be increasing. That is, for many programs a higher percentage of districts report shifting more funds in each successive year. Moreover, many districts report shifting all funding away from some programs, presumably eliminating associated program activities. Specifically, at least 40 percent of districts report shifting all funds away from eight programs, the largest being the Targeted Instructional Improvement Grant and Math and English Professional Development Institutes.

Districts Maintaining Funding for a Few Select Programs. In contrast to the overall trend for most flexed programs, Figure 7 shows that a select group of programs—including Regional Occupational Centers/Programs and community day schools—are experiencing less notable funding shifts. This suggests that continuing these specific activities remains a high priority in many communities. Additionally, comparing survey results across years indicates a slight decrease in the proportion of districts shifting funding away from a handful of programs, suggesting some districts are resuming activities they had temporarily reduced. Many of these select programs, such as instructional materials and deferred maintenance, involve activities that districts may have been able to defer for some years but not indefinitely.

Districts Desire Additional Near–Term Categorical Flexibility . . . Though spending requirements have been removed from many categorical programs, districts responding to our surveys over the past three years have consistently requested more flexibility over the categorical programs that remain restricted. For example, almost 40 percent of districts indicate providing more flexibility for the remaining categorical programs in 2012–13 would be among the most helpful steps the Legislature could take to help them accommodate their budgetary uncertainties. Given the deepening and prolonged fiscal challenges they have been facing, districts appear to be indicating a desire for additional flexibility tools beyond the ones established in 2009.

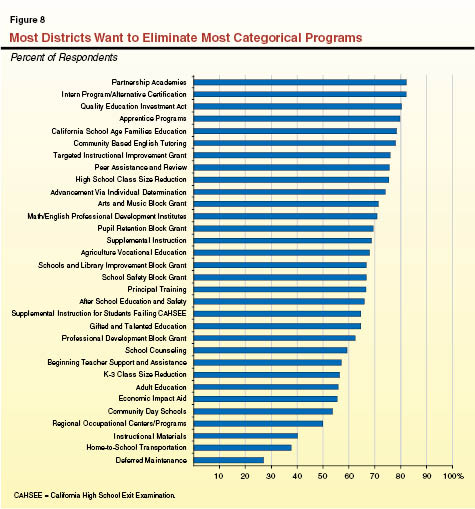

. . . And Long–Term Elimination of Most Categorical Programs. In addition to wanting more near–term flexibility, the vast majority of districts report a desire for ongoing relief from the programmatic requirements associated with most categorical programs. As shown in Figure 8, districts overwhelmingly support the elimination of many categorical programs. For example, more than 70 percent of districts report wanting 12 specific programs eliminated—the largest being the Quality Education Investment Act (QEIA). Districts were more likely to recommend elimination of two types of programs: (1) those in which only a small number of districts participate, such as partnership academies or apprenticeship programs; and (2) professional development (PD) programs, such as Peer Assistance and Review and Math and English Professional Development Institutes. (Roughly 30 percent of districts, however, indicated wanting some targeted PD funding reinstated, but with changed programmatic requirements.) In contrast, over half of respondents reported they would like the state to continue providing some dedicated funding for essential activities such as maintenance, transportation, and instructional materials (though not necessarily with the exact same program requirements).

Districts Planning for Challenging Budget Situation in 2012–13

The Governor's January budget proposal assumes passage of a ballot measure that would generate several billion dollars in additional state revenue, of which a portion would be dedicated to K–12 education. Should his revenue–generating ballot measure fail in November, the Governor would trigger at least $5.4 billion in midyear reductions, including a $2.8 billion cut to K–12 general purpose funding and withdrawal of his proposal to pay $1.6 billion in currently late K–12 state payments on time. While uncertainty over how voters will act in November makes developing a spending plan difficult for the state, it also is exceedingly challenging for school districts, as state laws governing teacher layoffs and local collective bargaining provisions make large midyear reductions difficult for them to implement. Moreover, districts seek to minimize midyear changes that can have disruptive and detrimental effects on students. As districts grapple with how to size their 2012–13 educational programs, including contingency plans for possible outcomes to the November election, our survey responses reveal a clear message from districts to the Legislature—maximize local flexibility and provide latitude to manage reductions at the local level. This section discusses how districts are approaching their 2012–13 budget plans.

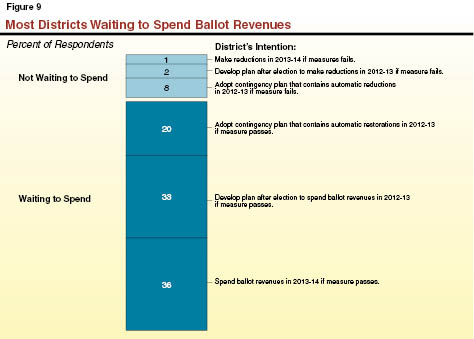

Most Districts Plan to Spend Potential Tax Revenue After Voters' Decision, Want State to Do the Same. Figure 9 shows that, in contrast to the Governor's approach in building the state budget, only a limited number of districts plan to build their budgets assuming the ballot measure will pass. Rather, almost 90 percent of districts plan to wait for the results of the November election before spending the potential tax revenue. Over two–thirds are waiting until the funds materialize before they even develop a plan for how to use them, and half of these would not spend the funds until 2013–14. Moreover, most respondents (almost 300 districts, or about 60 percent) request that the Legislature take a similar approach and avoid building a state budget that includes ballot–related revenues. If the state instead adopts the Governor's trigger approach, however, districts request the state provide additional methods for managing midyear reductions. For example, 30 percent of our survey respondents want the state to provide a post–election window for laying off certificated staff should the ballot measure fail.

Preserving Unrestricted Funding Is Districts' Highest Priority. Consistent with their messages on categorical flexibility, districts indicate an overwhelming preference that the 2012–13 state budget maintain—or increase—the timely provision of general purpose funds. Specifically, when we asked how districts would prefer the state spend any additional funds available for K–12 education, 87 percent ranked revenue limits and 57 percent listed paying down deferrals as their first or second priorities. Conversely, when we flipped the question and asked how districts would prefer the state make future reductions (if needed), most districts selected restricted activities or programs serving restricted populations. Specifically, 77 percent ranked education mandates and 52 percent ranked Economic Impact Aid (EIA) as their first or second most preferred place to cut. (In contrast to this trend, few districts—only 12 percent—listed special education as a first or second preference for reductions. This likely is because even though this is a restricted source of funding, districts are required by federal law to undertake the associated activities regardless of how much funding the state provides.)

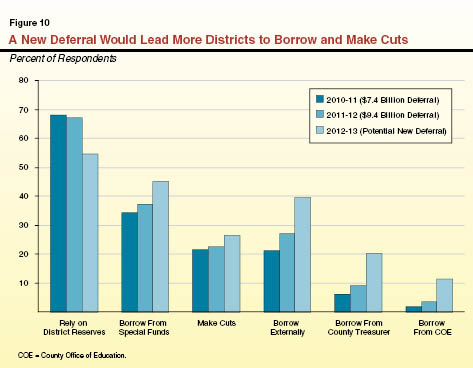

Would Be Increasingly Difficult for Districts to Accommodate Additional Deferrals. In recent years, the state has increasingly relied on deferring Proposition 98 payments as a way to achieve state budgetary savings and avoid further programmatic reductions. In 2011–12, total K–12 deferrals increased from $7.4 billion to $9.4 billion (roughly 20 percent of Proposition 98 payments), with some state payments delayed as long as nine months. Our survey results suggest that while a majority of districts accommodate these late payments by relying on internal reserves, this option is becoming less viable. Figure 10 shows that the most recent increase in deferred payments led more districts to borrow from special funds and other sources, with an even larger proportion of districts reporting they would turn to borrowing should the state institute additional deferrals in 2012–13. The increase in the number of districts that would borrow from the private market is particularly notable given the associated transaction and interest costs. Furthermore, about one–quarter of districts indicate they would manage any additional deferrals in 2012–13 by making cuts because they cannot accommodate or afford additional borrowing. These responses help explain why a majority of districts would prefer the state use any additional K–12 funding to retire existing deferrals.

Responses to our survey indicate districts have made notable reductions to their educational programs in recent years and now face another challenging budget situation in 2012–13. The 2012–13 situation is particularly uncertain for districts given they must begin the school year without knowing whether voters will approve additional tax revenues in November. Our survey findings also reaffirm how recent categorical flexibility provisions have fundamentally shifted the way districts use funds at the local level—and how disconnected existing program allocations have become from their original activities and populations. In light of these findings, we offer the Legislature two sets of recommendations—the first intended to help districts develop budgets in the near term and the second designed to improve the overall K–12 funding system in the long term. Figure 11 summarizes these recommendations, each of which is discussed in more detail below.

Figure 11

Summary of LAO Recommendations

|

Take Immediate Actions to Help Districts Manage Budget Uncertainty

|

- Remove strings from more categorical programs.

|

- Adopt modified version of Governor's mandate reform proposal.

|

- Reduce instructional day requirements.

|

- Give districts until August 1 to make final layoff decisions and establish post–election layoff option.

|

- Offer ways for districts to reduce costs by eliminating existing restrictions on (1) contracting out for noninstructional services and (2) pay and prioritization for substitute teachers.

|

|

Initiate Broad–Scale Restructuring of K–12 Funding System

|

- Replace existing funding system with weighted student formula or block grants.

|

- Implement new funding system over several years to give districts time to plan and adjust.

|

- Combine flexibility with stronger accountability.

|

Take Immediate Actions to Help Districts Manage Budget Uncertainty

Given Uncertainty of Revenues, Certainty of Options Would Help Districts Build 2012–13 Budget Plans. Our survey responses reveal that most districts plan to budget conservatively in 2012–13, waiting until voters approve additional tax revenue before they commit to spending it. By adjusting budgets now, districts protect themselves against either having to make disruptive midyear cuts or finding themselves unable to make sizeable midyear cuts and facing serious corresponding cash management problems. The large number of initial layoff notices reportedly issued this March confirms that many districts are planning for notable reductions. We recommend the Legislature take care not to adopt measures that might actually constrain districts' abilities to plan for budget uncertainty (such as prohibiting layoffs or programmatic reductions), potentially leaving them in an untenable financial situation should revenue–generating measures fail in November. In contrast, we recommend the Legislature increase the tools available for districts to balance the dual objectives of preparing for the possibility of unsuccessful ballot initiatives while mitigating detrimental effects on districts' educational programs. We offer five specific recommendations for the Legislature to increase district decision–making and budgetary flexibility. Districts will only take advantage of these tools if they are sure they can count on them when they adopt their budgets this summer. As such, we recommend these changes be part of the initial budget package and take effect July 1, 2012.

Remove Strings From More Categorical Programs. We recommend the Legislature extend categorical flexibility to several programs for which funding currently remains restricted, as requested by many districts responding to our survey. Even if the Legislature opts not to adopt the Governor's proposed weighted student funding formula, we recommend it approve his proposals to eliminate spending requirements for K–3 CSR, Home–to–School Transportation, and three small vocational education programs. Additionally, we continue to recommend the Legislature explore options for redirecting funding associated with the After School Education and Safety (ASES) and QEIA programs. (Because it was implemented through a ballot initiative, the Legislature would need to seek voter approval to repeal the automatic ASES spending requirement.) To ensure needy students continue to receive supplemental services, however, we recommend the Legislature maintain spending requirements for funds associated with English Learner and economically disadvantaged students, whether through the existing EIA program or a new formula.

Adopt Modified Version of Governor's Mandate Reform Proposal. We recommend the Legislature adopt the Governor's proposal to eliminate the existing mandate reimbursement process and instead provide funding through a block grant. (Because it would add unnecessary complication, we recommend rejecting the proposal to allow districts the option of continuing to claim for reimbursement through the existing mandate process.) This change would provide fiscal relief for many districts by eliminating half of the state–mandated activities that districts must perform under current state law as well as the burdensome reimbursement claiming process. Districts continuously request relief from the existing mandate system. Moreover, our survey respondents overwhelmingly list education mandates as the first place they would like the state to cut, should state budget reductions be necessary.

Reduce Instructional Day Requirements. We recommend the state allow districts to provide a shorter school year without incurring fiscal penalties. This would provide districts additional discretion to reduce their budgets based on local priorities. Different communities across the state may have differing perspectives as to the relative trade–offs of a shorter school year, larger class sizes, or reduced programmatic offerings, and we believe weighing those decisions at the local rather than state level could result in better educational decisions. While the purpose of this recommendation is to maximize local decision–making, the state could develop a framework for changing instructional time requirements based on the amount by which state funding is reduced. For example, if the state is considering a midyear trigger cut of $2 billion, it might reduce the minimum school year requirement by five days to allow districts to achieve half of these savings, assuming districts would use a combination of other tools to implement the remaining $1 billion reduction (each instructional day costs about $200 million statewide).

Make Two Changes to Teacher Layoff Process. We recommend the state change the statutory deadlines for both final and contingency layoff notifications. Though districts already have initiated their layoff processes based on the March 15 notification requirement, we recommend the Legislature move the final notification date from May 15 to August 1. This would give districts more certainty as to both the final state budget package and important local information (such as teacher retirements or resignations) prior to finalizing their layoff decisions. Additionally, we recommend the Legislature replace the existing August layoff window with a rolling emergency window whereby districts could lay off staff midyear if the state makes significant budget changes. With a guaranteed post–election layoff option to address potential midyear trigger cuts, school districts might lay off fewer teachers heading into the 2012–13 school year.

Offer Other Ways to Reduce District Costs. We recommend the state remove two other statutory provisions that currently constrain school districts' abilities to economize. First, we recommend eliminating existing restrictions on school districts that seek to contract out for noninstructional services (such as food services, maintenance, clerical functions, and payroll). Providing districts with greater discretion to choose the most cost–effective options for these services could lead to savings at the local level. Second, we recommend removing restrictions relating to substitute teachers. Specifically, we recommend repealing requirements that districts hire substitute teachers based on seniority rankings and pay substitute teachers at their pre–layoff salary rates. Instead, we recommend districts be able to choose from among the entire pool of substitute teachers and negotiate associated pay rates at the local level. This could generate local savings and afford districts a better opportunity to hire the most effective substitute–teaching candidates.

Initiate Broad–Scale Restructuring of K–12 Funding System

The Time for Fundamental Restructuring Is Now. We recommend the state immediately begin laying the groundwork for a new K–12 funding system. Long criticized for being overly complex and inefficient, recent changes have rendered the existing system even more irrational and inequitable. For the third consecutive year, our survey findings indicate that most districts have responded to recent flexibility provisions by shifting most or even all funding away from most categorical programs. Additionally, the state has "frozen" district allocations for the flexed categorical programs at 2008–09 levels, continuing to distribute the same proportion of funds to each district regardless of changes in student enrollments during the ensuing years. These two trends have increasingly disconnected existing funding allocations from the original categorical purposes and student needs for which they were originally intended. As such, we believe it is increasingly urgent that the state rethink its overall approach to K–12 funding and craft a better system. Districts echo this sentiment, with large majorities of our survey respondents indicating they believe most existing program requirements should be eliminated permanently.

Replace Existing Funding System With Weighted Student Formula or Block Grants. We recommend the Legislature pursue one of two approaches to restructuring the school funding system—a weighted student formula or thematic block grants. The Governor proposes the state adopt the weighted student approach. Under this methodology, districts serving higher proportions of low–income or English Learner students would receive additional funding, but all funds would be general purpose in nature, with no "strings" or spending restrictions. While this would provide districts maximum flexibility, we are concerned it would not provide sufficient assurances that districts provide supplemental services for needy students. Were the Legislature to choose the weighted student approach, we recommend maintaining some broad spending requirements for disadvantaged students, at least until the state has refined the existing accountability system (as discussed below). Alternatively, the state could restructure K–12 funding into a few block grants. These funding "pots" could have broad thematic objectives and requirements that provide districts with direction but also latitude as to how specifically to structure local services. If the Legislature opts for this approach, it will want to avoid establishing too many grants or imposing too many restrictions, lest it recreate some of the problems associated with the existing, overly prescriptive categorical system.

Implement New Funding System Over Several Years to Give Districts Time to Plan and Adjust. Regardless of which approach the Legislature adopts, a new funding formula almost inevitably will change individual district allocations. Consequently, districts will need some time to plan for these potential changes in resources. We believe the Governor's proposal to transition to a new formula over six years, while holding districts harmless from any potential loss in 2012–13, is reasonable. The Legislature could consider extending the hold harmless period for an additional year or two, especially given current budget conditions and fiscal uncertainties. However, we do not believe the fact that some districts might receive less funding in the future should impede the state from immediately initiating progress towards a more rational and equitable system. The Legislature will need to weigh how long to continue protecting historical advantages for certain districts against the benefits of allocating resources based on the needs of current student populations.

Combine Flexibility With Stronger Accountability. We recommend the Legislature refine its approach to K–12 accountability in tandem with changes to the school funding system. We believe ceding most authority over education programs to districts should be contingent upon the state's ability to monitor student achievement and intervene when locally designed efforts are not resulting in desired outcomes. While the state has made great strides in developing accountability and statewide student data systems over the past decade, we believe the existing framework is not yet nuanced enough to help districts clearly determine how they need to improve or help the state clearly identify which school districts need intervention. A more robust system would include improvements such as vertically scaled assessments, value–added performance measures based on student–level data, a single set of performance targets, and more effective types of interventions. We also recommend linking a stronger focus on outcomes with a refocused mission for the California Department of Education—placing a greater emphasis on data, accountability, and best practices in lieu of compliance monitoring. Needed enhancements in accountability would take time, however, and should not impede progress towards a more rational and equitable funding system. As a new approach to K–12 funding is being phased in, the state could maintain some spending requirements—particularly for disadvantaged students—and then remove those requirements once an improved accountability system has been fully implemented.

Responses to our district finance survey indicate that California schools have experienced notable changes as a result of the recent recession, including a reduced workforce, larger class sizes, shorter school years, and less extensive programmatic offerings. Given the slow pace at which the economy is recovering, combined with uncertainty over the outcome of the November election, school districts indicate they are bracing themselves for additional reductions in 2012–13. Although the state and districts continue to struggle with tight budgets, we believe the Legislature can take a number of actions to assist districts in managing their fiscal challenges. Equally important, we believe now is the time for the Legislature to lay the groundwork for long–term improvements to the K–12 funding and accountability systems. Acting now will establish a solid foundation upon which the state can build as fiscal conditions improve.