Summary

Over the last two years, a small number of cities and counties did not receive enough local property tax revenue to offset two complex state–local financial transactions: the triple flip and vehicle license fee (VLF) swap. This funding insufficiency, commonly called “insufficient ERAF” (Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund), requires state action if the affected local governments are to receive complete payment. To assist the Legislature in responding to this unanticipated development, this report describes the causes of insufficient ERAF and outlines a framework the Legislature may wish to use in considering remedies. We summarize the highlights of our report below.

Insufficient ERAF Probably Is a Limited Issue. To date, insufficient ERAF has affected local governments in only two counties—Amador and San Mateo—and resulted in total VLF swap funding shortfalls of less than $2 million. Insufficient ERAF may grow somewhat over the next few years. In the longer term, however, insufficient ERAF likely will be limited to a small number of cities and counties—or not occur at all in some years.

Two Possible Levels of Compensation for Insufficient ERAF Appear Reasonable. As insufficient ERAF is not the product of any particular local government actions, a strong analytical argument can be made that the state should reimburse cities and counties for all triple flip and VLF swap funding shortfalls. This would require increased state expenditures, potentially up to tens of millions of dollars annually. On the other hand, in recognition of the significant fiscal benefits cities and counties receive under the VLF swap, the Legislature may wish to reimburse cities and counties only where necessary to replace actual sales tax and VLF revenue losses.

Compensation Mechanisms Are Limited. We see two primary options for compensating local governments experiencing insufficient ERAF: provide the compensation in the annual state budget or through a redirection of certain local education agency property tax revenues.

Introduction

Almost a decade ago, the Legislature adopted two complex financial transactions with California’s cities and counties known as the “triple flip” and “VLF swap.” Under these transactions, city and county sales tax and VLF revenues are reduced, but local revenue shortfalls are offset annually by property taxes redirected from (1) a countywide educational account (ERAF) and, in some cases, (2) certain K–12 and community college districts. Local education district revenue losses, in turn, are offset by increased state aid.

Earlier this year, the auditor from Amador County reported an unanticipated development: available funding in 2010–11 was not sufficient to fully reimburse the second financial transaction, the VLF swap. The county had insufficient ERAF—not enough revenues to fully compensate local governments for the triple flip and/or VLF swap. More recently, county auditors reported that insufficient ERAF continued in Amador County in 2011–12 and expanded to include local governments in San Mateo County.

In the 2012–13 state budget, the Legislature appropriated $1.5 million to fully offset Amador County’s 2010–11 funding shortfall. (Funding insufficiencies in Amador and San Mateo in 2011–12 were not known until after the state budget was adopted.) To consider the state’s options for addressing future claims of insufficient ERAF, the Supplemental Report of the 2012–13 Budget Package directed the Legislative Analyst’s Office and the Department of Finance (DOF) to submit reports (1) addressing the conditions under which local governments may be compensated in cases where there are insufficient local funds to offset fully the fiscal effect of the triple flip and VLF Swap and (2) outlining one or more alternative mechanisms for providing such compensation. This report is submitted in fulfillment of our office’s requirement.

Background

In order to better comprehend the complicated issue of insufficient ERAF, this report begins with an overview of California’s system of distributing property taxes amongst local governments. It then describes several major statutory measures that are integral to the issue of insufficient ERAF: the 1990s ERAF property tax shift, triple flip, VLF swap, and dissolution of redevelopment.

Property Tax Allocations Basics

Property Taxes Are Shared by Many Local Governments. All property tax revenue remains within the county in which it is collected to be used exclusively by local governments (cities, counties, special districts, K–12 schools, and community college districts). The county auditor is responsible for allocating revenue generated from the 1 percent rate to local governments pursuant to state law. The allocation system commonly is referred to as “AB 8,” after the bill that first implemented the system—Chapter 282, Statutes of 1979 (AB 8, L. Greene). In general, AB 8 provides a share of the total property tax revenue collected within a community to each local government that provides services within the community.

Property Taxes Also Affect the State Budget. Although the state does not receive any property tax revenue directly, the state has a substantial fiscal interest in the distribution of property tax revenue because of the state’s education finance system under which the state guarantees each school district an overall level of funding. For K–12 districts, each district receives a comparable amount of per–pupil funding—a “revenue limit”—from local property taxes and state resources combined. Community college districts receive apportionment funding from local property taxes, student fees, and state resources. If a district’s local property tax revenue (and student fee revenue in the case of community colleges) is not sufficient, the state provides additional funds. Conversely, if a district’s nonstate resources alone exceed the district’s revenue limit or apportionment funding level, the district does not receive general purpose state aid (though they typically receive funding for various categorical programs). These districts commonly are referred to as “basic aid” districts because historically they have received only the minimum amount of state aid required by the State Constitution (known as basic aid).

Each year, the state estimates how much each district will receive in local property tax revenue (and student fee revenue in the case of community colleges), then the annual budget act appropriates state General Fund to “make up the difference” and fund the district’s revenue limit or apportionment at the intended level. Frequently, however, the actual property tax revenues allocated to school districts may be less than anticipated. The state’s education finance system addresses these shortfalls differently for different types of educational entities. For K–12 districts, all funding shortfalls are backfilled automatically with additional state aid. In contrast, explicit state action is required to backfill community college funding shortfalls.

1990s ERAF Property Tax Shift

Property Taxes Shifted to Schools. In 1992–93 and 1993–94, in response to serious budgetary shortfalls, the state permanently redirected almost one–fifth of total statewide property tax revenue from cities, counties, and special districts to K–12 and community college districts. Under the changes in property tax allocation laws, the redirected property tax revenue is deposited into a countywide fund for schools, ERAF. The property tax revenue from ERAF is distributed to nonbasic aid schools and community colleges, reducing the state’s funding obligations for K–14 education.

“Excess ERAF” Shifted Back. In the late 1990s, some county auditors reported that their ERAF accounts had more revenue than necessary to offset all state aid to non–basic aid K–12 and community college districts. In response, the Legislature enacted a law requiring that some of these surplus funds be used for countywide special education programs and the remaining funds be returned to cities, counties, and special districts in proportion to the amount of property taxes they contributed to ERAF. The ERAF funds that are returned to noneducational local governments are known as excess ERAF.

Triple Flip

The Triple Flip Is Reimbursed From ERAF. In 2004, state voters approved Proposition 57, a deficit–financing bond to address the state’s budget shortfall. The state enacted a three–step approach—commonly referred to as the triple flip—that provides a dedicated funding source to repay the deficit bonds:

- Beginning in 2004–05, one–quarter cent of the local sales tax is used to repay the deficit–financing bond.

- During the time these bonds are outstanding, city and county revenue losses from the diverted local sales tax are replaced on a dollar–for–dollar basis with property taxes shifted from ERAF.

- K–12 and community college district tax losses from the redirection of ERAF to cities and counties, in turn, are offset by increased state aid.

Triple Flip Projected to End in 2016–17. Based on current projections, the Proposition 57 deficit–financing bond will be repaid in 2016–17 and the triple flip will be ended. At that time, the $1.7 billion in ERAF monies that otherwise would have been used to fund the triple flip will be available for other uses—namely funding the VLF swap and offsetting state K–14 expenditures.

VLF Swap

VLF Traditionally Has Been a Local Revenue Source. Established in 1935, the VLF is an annual tax on the ownership of registered vehicles in California in place of taxing vehicles as personal property. The tax is based on the vehicle’s purchase price and declines in accordance with a statutory depreciation schedule. For most of its years, the primary use of VLF has been as a general purpose local government revenue source—with all or most VLF revenues distributed to cities and counties on a per capita basis.

State Began Reducing VLF Revenue Collections in the Late 1990s. While the VLF rate was 2 percent for over five decades, the state began enacting measures in 1999 that reduced the effective VLF rate paid by vehicle owners—thus reducing revenue collections. Most notably, Chapter 322, Statutes of 1998 (AB 2797, Cardoza), established an “offset” to the annual VLF paid by vehicle owners. Under this legislation, the VLF owed by a vehicle owner was initially calculated using the 2 percent tax rate and then the offset was applied, effectively reducing the rate paid by the vehicle owner. The amount of the tax reduction was shown as a credit on the vehicle owner’s registration bill. Beginning in 1999, this offset acted to reduce VLF collections by 25 percent. Chapter 322 provided for a series of additional reductions beginning in 2001, possibly reaching a maximum 67.5 percent beginning in 2003, if General Fund revenue growth met certain targets. Subsequent legislation accelerated the pace of these additional effective rate reductions, setting the VLF offset at 67.5 percent and reducing VLF collections a commensurate amount. Under this reduction, the effective VLF rate paid by vehicle owners was 0.65 percent.

State General Fund Allocations Backfilled Local Revenue Losses. These reductions in VLF collections substantially reduced the revenue available for cities and counties. The Legislature, however, replaced the lost VLF revenues with General Fund allocations to cities and counties on a dollar–for–dollar basis. Funds from the General Fund backfill generally were allocated on a per capita basis so that each city and county received the same amount of revenue as the local government would have received absent the VLF reductions. The backfill was continuously appropriated and, therefore, not subject to annual appropriation in the budget bill.

General Fund Resources Found Insufficient to Cover Backfill. Chapter 322 included a “trigger” provision requiring the effective VLF rate to be increased during periods in which insufficient General Fund monies were available to backfill for city and county revenue losses. In these cases, General Fund expenditures for the backfill would be reduced, accompanied by a commensurate increase in VLF payments made by vehicle owners. In June 2003, Governor Davis determined that there were insufficient funds for the state to continue making backfill payments to cities and counties. As a result, backfill payments were suspended in June 2003. For various reasons, however, the effective VLF rate was not returned to 2 percent until October 2003. Following the recall election, in November 2003 Governor Schwarzenegger reversed the determination of insufficiency. This restored the effective VLF rate to 0.65 percent and resumed payment of the General Fund backfill to cities and counties. The time difference between the suspension of the backfill payments and the increase in the effective VLF rate resulted in revenue losses of $1.3 billion for cities and counties. This amount was deemed to be a loan from cities and counties to the state, and was repaid during the 2005–06 budget year.

VLF Swap Enacted to Replace General Fund Backfill. In 2004, the state and cities and counties worked together to develop a new mechanism for reimbursing cities and counties for their reduced VLF revenue. This mechanism, known as the VLF swap, provides an element of increased security for cities and counties by replacing a state–controlled reimbursement with a revenue source that is subject to greater local control. Specifically, the VLF swap replaced the General Fund VLF backfill with property taxes redirected at the county level from (1) ERAF and, if ERAF revenues are not sufficient, from (2) nonbasic aid K–12 and community college districts. (All reductions in revenue to K–12 and community college districts are offset by additional state aid.) The VLF swap also specified that future growth in these reimbursement property taxes would not be distributed on a per capita basis (like VLF revenues and the VLF General Fund backfill had been). Instead, the property taxes provided as part of the VLF swap would grow each year based on growth in property values within the entity.

Redevelopment Dissolution

Dissolution of Redevelopment Increases Property Taxes Distributed to Schools. The 2011–12 budget package included legislation—Chapter 5 (ABX1 26, Blumenfield)—that resulted in the dissolution of all redevelopment agencies (RDAs) in California effective February 2012. As discussed in our report,

The 2012–13 Budget: Unwinding Redevelopment, by diverting property taxes from K–12 and community college districts, redevelopment had the overall effect of increasing state costs for K–14 education. Under the dissolution process, the property tax revenue that formerly went to RDAs is used first to pay off redevelopment debts and obligations and the remainder is distributed to local governments, including K–12 and community college districts, in accordance with AB 8. The shift of property taxes to nonbasic aid districts reduces state K–14 expenditures by a similar amount. Over time, as former redevelopment debts and obligations are retired, state savings from redevelopment dissolution will grow as school districts receive larger distributions of property taxes. The cash and other liquid assets of former RDAs also will be distributed to local governments in accordance with AB 8. These distributions will provide additional one–time increases in revenue for school districts in the current year and over the next few years.

No Change in Excess ERAF. In general, an increase in the amount of property tax revenue to school districts decreases (1) the amount of state funding needed by schools to reach their revenue limits and (2) the amount of ERAF that can be used to offset the state’s obligations. As less ERAF funding is needed to offset state education expenditures, more property tax is returned to local governments as excess ERAF. This, in turn, leaves fewer resources in ERAF available to make payments under the triple flip and VLF swap. In order to maximize the state’s fiscal benefit from the dissolution of redevelopment, the Legislature enacted Chapter 26, Statutes of 2012 (AB 1484, Committee on Budget), which directs county auditors to exclude revenues provided to schools by the dissolution of RDAs in the calculation of excess ERAF.

Administering the Triple Flip and VLF Swap

Calculating Payments to Cities and Counties

Triple Flip Reimbursements Equal to Projected Annual Reductions in Sales Tax Revenue. Each fiscal year, DOF provides county auditors with an estimate of the sales tax revenue lost by each local government as a result of the triple flip. The DOF’s estimate is based on the actual amount of sales tax revenue distributed to each local government in the prior year, adjusted for projected growth (as determined by the State Board of Equalization) in the current year.

VLF Swap Payments Pegged to Growth in Local Assessed Property Values. In general, each city and county’s annual VLF payment is equal to its VLF losses related to the state reductions in 2004–05, grown by the total percentage change in the city or county’s assessed value of taxable property—or assessed valuation—between 2004–05 and the current year. For example, if a city’s VLF revenue losses were $1 million in 2004–05 and its assessed valuation increased by 20 percent between 2004–05 and 2012–13, then its VLF payment in 2012–13 is $1.2 million. For the purposes of this calculation, county auditors are directed to ignore any growth in assessed valuation due to changes in a city’s boundaries, such as an expansion of boundaries through annexation, that occur after 2004–05.

Reimbursement Process

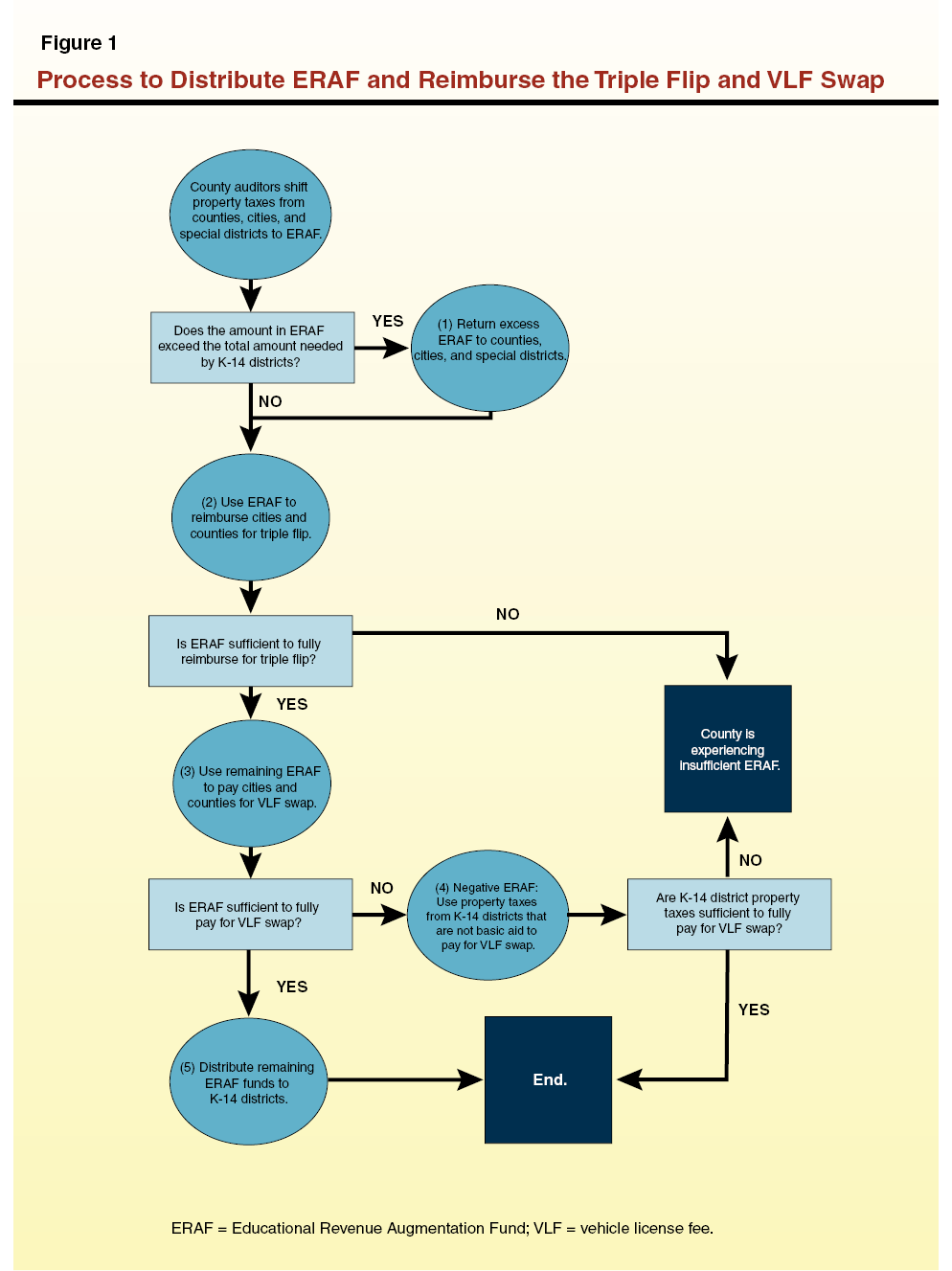

Figure 1 displays the complex process county auditors follow to allocate ERAF and to reimburse cities and counties for the triple flip and VLF swap. This figure also shows that, under certain circumstances, it is possible that the auditor could determine that there are not enough funds to fully compensate cities and the county for the triple flip and/or the VLF swap. These funding shortfalls are referred to as insufficient ERAF. The major steps in the process are as follows.

Step 1: Return Excess ERAF. As shown in the figure, the first step is for each county auditor to determine whether the funds deposited into the countywide account exceed the amount needed by all nonbasic aid K–12 and community college districts in the county, plus a specified amount for special education. If so, the special education program receives funding from ERAF and any remaining ERAF is returned to cities, special districts, and the county in proportion to the amount of property taxes they contributed to ERAF. This calculation of excess ERAF was recently modified to exclude property taxes distributed to K–12 and community college districts as a result of redevelopment dissolution.

Step 2: Reimburse Triple Flip. Following the calculation and distribution of excess ERAF, state law directs county auditors to reimburse local governments for their revenue losses associated with the triple flip. This reimbursement is shown in the figure as step two. If the county auditor uses all available ERAF, but determines that the local governments have not been fully reimbursed for the triple flip, the county has insufficient ERAF. In this situation, additional state action is required if cities and counties are to be fully reimbursed for the triple flip.

Steps 3 and 4: Pay for VLF Swap. After reimbursing the triple flip, the next use of ERAF is to make payments to local governments for the VLF swap. If the county auditor determines that the remaining ERAF resources alone are not sufficient to fully pay cities and the county for the VLF swap, the county auditor redirects some property taxes from nonbasic aid K–12 and community college districts for this purpose, as shown in step 4. The redirection of school property taxes is commonly referred to as “negative ERAF” because it decreases K–12 and community college property taxes rather than supplementing them (the original purpose of ERAF). If ERAF and nonbasic aid school district property taxes combined do not contain enough resources to make the payments required under the VLF swap, then the county has insufficient ERAF. In this situation, additional state action is required for cities and counties to receive the full VLF swap payment.

Step 5: Distribute Remaining ERAF to K–12 and Community College Districts. Any funds remaining in ERAF after the other uses have been satisfied are distributed to schools and offset state education spending.

Examples of the ERAF Distribution Process

While the same rules govern the distribution of ERAF throughout the state, the outcome varies significantly from county to county. This variation reflects the large differences among counties in the amount of property taxes allocated to K–12 and community college districts, the number of students enrolled in K–14 programs, the level of ERAF resources and sales taxes, and other factors. Below, we present four examples using data from 2011–12.

Simplest Example: Alameda County. Property tax collections in the county totaled $2 billion—of which $410 million was deposited in ERAF. Because the county’s K–12 and community college districts needed more than $410 million in additional property taxes to meet their revenue limits or guaranteed funding levels, no ERAF resources were returned to cities, counties, and special districts as excess ERAF. Instead, ERAF resources were available to make triple flip and VLF swap payments to cities and the county ($309 million) and the remainder was distributed to nonbasic aid K–12 and community college districts ($101 million).

Negative ERAF: Los Angeles County. Property tax collections in the county totaled about $10 billion—of which $2.08 billion was deposited in ERAF. K–12 and community college districts needed more than $2.08 billion to satisfy their revenue limits or guaranteed funding levels. Therefore, no ERAF funds were returned to cities, counties, and special districts as excess ERAF. The first use of the county’s ERAF (before allocating any funds to K–12 and community college districts) was to provide $302 million in triple flip reimbursements to cities and the county. After ERAF funds were distributed for the triple flip, $1.78 billion remained in ERAF to fund VLF swap payments of $1.84 billion—resulting in a shortfall of about $65 million. To cover this shortfall, Los Angeles’ auditor redirected $65 million of property taxes from nonbasic aid K–12 and community college districts to ERAF to make the full VLF payment. (The numbers above exclude certain revenues related to the county’s policies regarding delinquent property taxes.)

Excess ERAF: Napa County. Property tax collections in the county totaled $275 million—of which $34 million was deposited to ERAF. In total, K–12 and community college districts in the county needed only one–fourth of the funds deposited into ERAF to meet their funding needs. Thus, $25 million of the ERAF resources were first used to offset state expenditures in county special education programs ($7 million), with the remaining funds ($18 million) returned to cities, counties, and special districts as excess ERAF. Following these distributions, just under $9 million remained in ERAF to fund the triple flip and VLF swap. These funds were used first to pay triple flip reimbursements totaling $6 million. The remaining $3 million was applied to a VLF swap obligation of $23 million—resulting in a shortfall of $20 million. To cover this funding shortfall, Napa’s auditor redirected $20 million from property taxes of nonbasic aid K–12 and community college districts.

Insufficient ERAF: San Mateo County. Property tax collections in the county totaled $1.4 billion—of which $187 million was deposited to ERAF. In total, the county’s K–12 and community college districts needed $38 million from ERAF to meet their guaranteed funding levels, leaving $149 million to distribute to county special education programs ($18 million) and to cities, counties, and special districts as excess ERAF ($131 million). Following these distributions, $38 million remained in ERAF to fund the triple flip and VLF swap. These funds were used first to pay triple flip reimbursements totaling $32 million. The remaining $6 million was applied to a VLF swap obligation of $125 million—resulting in a shortfall of $119 million. To cover this funding shortfall, San Mateo’s auditor shifted property taxes from nonbasic aid K–12 and community college districts. Because many K–12 and community college districts in San Mateo are basic aid, however, the amount of K–12 and community college district property taxes available to be shifted was slightly lower ($200,000) than the $119 million needed to reimburse city and county for the VLF swap. Thus, San Mateo County experienced $200,000 of insufficient ERAF.

A Recent Development: Insufficient ERAF

In 2010–11, Amador County found that the resources available from ERAF and nonbasic aid K–12 and community college district property taxes were insufficient to fully fund VLF swap payments to cities and counties. This funding shortfall—the first reported case—is known as insufficient ERAF. If insufficient ERAF occurs, state action is required if cities and counties are to receive full triple flip or VLF swap payments. In the 2011–12, two counties—Amador and San Mateo—reported having insufficient ERAF. This section discusses the factors leading to insufficient ERAF and explores the possibility of insufficient ERAF extending to other counties and affecting payments for the triple flip.

Factors Leading to Insufficient ERAF

Prevalence of Basic Aid School Districts Is the Most Significant Cause of Insufficient ERAF. In general, counties where a greater proportion of K–12 and community college districts are basic aid are more likely to experience insufficient ERAF. The prevalence of basic aid districts can affect the amount of resources available to fund the triple flip and VLF swap in two ways. First, if more K–12 and community college districts are basic aid, there is less capacity to use ERAF to offset state education costs and, therefore, more ERAF is returned to local governments as excess ERAF. Monies returned as excess ERAF are not available to fund triple flip or VLF swap payments. Second, because state law does not allow county auditors to shift property taxes from basic aid districts to fund the VLF swap, an increase in the number of basic aid districts decreases the pool of resources county auditors can draw from to fund the VLF swap. In 2011–12, around 10 percent of K–12 and community college districts in the state were basic aid. In contrast, about two–thirds of K–12 and community college districts in San Mateo County were basic aid and Amador County’s only K–12 district was basic aid.

Local Demographics, Property Values, and State Policies Drive Basic Aid Status. A wide range of factors influence whether a K–12 or community college district is basic aid, including economic and demographic factors, as well as state fiscal and educational policies. In general, basic aid districts (1) receive comparatively high property tax revenue—because of substantial property wealth and/or they receive a higher share of the property tax (for more information on property tax allocation, see our report,

Understanding California’s Property Taxes) and (2) serve a community with a comparatively smaller school–aged population. In addition, changes in state policy can also influence whether a district is basic aid. The number of basic aid districts generally increases when the state decreases K–12 district revenue limits and community college apportionment funding levels, and vice–versa. Changes in revenue limits and apportionment funding levels can be caused by state fiscal actions (such as a reduction of overall state K–14 expenditure) or by state policy changes (such as consolidation of categorical program funding into revenue limits). In addition, state actions that increase the property tax revenue of K–12 and community college districts (such as dissolution of redevelopment) can increase the number of basic aid districts.

Slower Growth of ERAF Contributes Modestly to Insufficient ERAF. Property tax revenues deposited in ERAF are the primary funding source for VLF swap payments. Historically, ERAF resources have grown slightly slower than VLF payments—by up to about 1 percent a year. The slower growth of ERAF relative to VLF swap payments (which grow at the rate of change in assessed valuation) has reduced somewhat the amount of resources available to fund the VLF swap, thus contributing to insufficient ERAF. The overall statewide effect of ERAF’s slower growth rate, however, has been small. If ERAF grew at the same pace as VLF swap payments, there currently would be around $340 million more ERAF to fund VLF swap payments—an amount equal to 6 percent of total VLF payments. We note that the difference between ERAF and VLF swap payment growth rates in Amador and San Mateo Counties was not a significant factor contributing to their ERAF insufficiencies.

Insufficient ERAF In Future Years

To date, insufficient ERAF has been a limited issue: only a small number of local governments have been affected and the dollar amount of the insufficiencies has been relatively minor. Going forward, it is difficult to project the magnitude of insufficient ERAF in future years. However, based on our current economic and demographic forecasts and our review of county triple flip and VLF swap financial data, in the absence of significant state educational policy changes, we think it is likely that insufficient ERAF (1) will increase over the next few years (potentially to tens of millions of dollars in some years), (2) may affect triple flip reimbursements in a small number of counties, and (3) will abate considerably after 2016–17 (following the end of the triple flip), possibly continuing to affect a small number of counties on an ongoing basis. We note that these outcomes could be influenced by legislative actions to increase general purpose funding levels for K–12 and community college districts—such as transitioning to a new K–12 weighted student formula—which could substantially reduce future growth in basic aid districts and, therefore, insufficient ERAF. Below, we discuss the rationale underlying our insufficient ERAF projections.

Property Tax Growth Over Next Few Years Could Create More Basic Aid Districts. In 2012–13 and over the next few years, many K–12 and community college districts are expected to receive a significant increase in property tax revenue from the distribution of former RDA assets and an anticipated increase in property values. This growth in property tax revenue is likely to shift temporarily some K–12 and community college districts into basic aid status and, in turn, increase the number and dollar amount of ERAF insufficiencies experienced by local governments. The ERAF insufficiency faced by local governments in San Mateo County is likely to increase significantly in 2012–13, from $200,000 to several million or more. Also, at least one additional county—Napa—appears at risk of having insufficient ERAF in 2012–13 or the near future. Despite the potential growth of insufficient ERAF over the next few years, the issue is not likely to expand beyond a small number of counties because the vast majority of counties have only a small number of K–12 and community college districts that are basic aid or are close to becoming basic aid.

Chance of Triple Flip Funding Shortfalls. A few counties—San Mateo and Napa—appear somewhat at risk of developing insufficient ERAF as a result of ERAF resources being inadequate to reimburse cities and counties for the triple flip. This situation can occur if a significant portion of a county’s ERAF revenues are distributed to special education programs and to local governments as excess ERAF, leaving inadequate funds to reimburse for the triple flip. In 2011–12, over 70 percent of ERAF monies in San Mateo and Napa counties were distributed to special education programs and as excess ERAF, leaving less than 30 percent of ERAF to fund the triple flip and VLF swap. Most of the funds remaining in ERAF were used to reimburse the triple flip. For this reason, a relatively small increase in excess ERAF distributions—for example, a 5 percent increase in San Mateo County—likely would result in a triple flip funding shortfall. It is possible such an increase in excess ERAF distributions could result from expected growth in property values in San Mateo and Napa counties over the next few years. Because the triple flip is scheduled to end in 2016–17, any triple flip related insufficient ERAF would be a temporary, short–term issue.

End of Triple Flip Should Decrease ERAF Insufficiencies. Any growth in insufficient ERAF that occurs over the next few years is likely to be reversed beginning in 2016–17. As mentioned previously, the Proposition 57 deficit–financing bonds are projected to be repaid in 2016–17 and the triple flip will end. At that time, there will be roughly $1.7 billion (about one–third of statewide VLF swap payments) more ERAF funding available statewide to fund the VLF swap—significantly decreasing the likelihood of VLF swap funding shortfalls. In addition, state K–14 expenditures are projected to increase consistently between 2013–14 and 2017–18, likely leading to growth in revenue limit entitlements for K–12 districts and apportionment funding levels for community colleges. To the extent growth in revenue limits and apportionment funding exceeds growth in K–12 and community college district property taxes, the number of basic aid districts could decrease. The combination of these factors should reduce the possibility of local governments experiencing insufficient ERAF. As a result, beginning in 2016–17, it is likely that insufficient ERAF will be limited to a small number of counties—or perhaps nonexistent in some years—for the foreseeable future.

Addressing Insufficient ERAF

In addressing claims of insufficient ERAF in future years, the Legislature is faced with two primary decisions: how much compensation cities and counties should receive and how the compensation should be provided. In the sections that follow, we provide a framework the Legislature may wish to use in considering these decisions.

How Much Should Cities and Counties Be Compensated for Insufficient ERAF?

Deciding the amount of compensation to provide is difficult and inevitably requires the Legislature to make trade–offs between providing funding for state versus local government programs—and weighing implicit commitments made by previous Legislatures. As we discuss below, we think a strong analytical argument can be made for developing a funding mechanism that provides full reimbursement for all shortfalls in triple flip and VLF swap reimbursements. However, it would also be reasonable for the Legislature to consider a lower level of reimbursement for VLF swap funding shortfalls in recognition of an additional unforeseen outcome of the VLF swap: cities and counties have received a significant fiscal benefit from the VLF swap due to unexpected growth in VLF swap payments. Should the Legislature wish to provide a lower level of support, we think a reasonable alternative would be to (1) provide full reimbursement for all triple flip losses and (2) reimburse VLF swap shortfalls to the extent that a local government did not receive more revenues under the VLF swap than it would have if the VLF rate had remained 2 percent.

Providing Full Reimbursement. The legislative record is unambiguous that the state intended to provide each city and county with (1) dollar–for–dollar reimbursement for their local sales tax losses associated with the triple flip and (2) VLF swap payments equal to the local government’s 2004–05 VLF losses, grown by annual change in its assessed value. The Legislature specified that the resources to provide this compensation were to be property taxes in ERAF and, if necessary, property taxes redirected from nonbasic aid K–12 and community college districts—a funding system that was believed to be sufficient to accomplish the Legislature’s objective. The funding insufficiency that has developed is a byproduct of California’s complex system of local finance and not the result of any actions by cities and counties. Therefore, there is no clear reason that some local governments should get lower levels of reimbursement simply because they are located in a county with insufficient ERAF.

Alternative: Fully Reimburse Actual Local Government Revenue Losses. While it is clear the Legislature intended for VLF swap payments to grow with annual changes in assessed valuation, it is not clear the Legislature could have known this would result in most cities and counties receiving VLF swap payments significantly in excess of their VLF losses. As discussed in the nearby box, VLF swap payments have grown relatively quickly since 2004, significantly surpassing the amount of VLF revenues that local governments lost as a result of the VLF swap. Local governments today are receiving $2 billion more annually than they would have received if the VLF rate had been left at 2 percent. In recognition of this fact, the Legislature may wish to consider an alternative approach to insufficient ERAF which limits reimbursement to the actual amount of sales tax and VLF losses a local government experienced. Under this approach, all triple flip shortfalls would be reimbursed, but the state would reimburse VLF swap shortfalls only to the extent that the local government had not already received at least the same amount of funding it would have received if the swap had not occurred and the VLF rate was 2 percent. This limitation on VLF reimbursement would decrease the magnitude of state liabilities—no additional reimbursement would be required for the cases of insufficient ERAF that have occurred to date. While the analytical argument for this alternative is less straightforward, it is consistent with the notion that the state’s goal was to hold local governments harmless from the fiscal effects of the VLF rate reduction—not to increase local government revenues overall.

A Look at Growth in Vehicle License Fee (VLF) Payments

VLF Swap Payments Have Grown Faster Than VLF Revenues. Each year, a city’s or county’s VLF payment increases (or decreases) proportionately to the change in its assessed valuation. After the adoption of the VLF swap, statewide growth in assessed valuation—and, as a result, VLF swap payments—has significantly exceeded growth in VLF revenues. From 2004–05 to 2011–12, VLF swap payments grew by an average of about 5 percent each year, while VLF revenues declined by an average of about 0.5 percent each year. Consequently, annual statewide VLF swap payments now are roughly $2 billion (around 45 percent) greater than the VLF revenues lost by cities and counties. This large fiscal benefit for cities and counties was not foreseen at the time the VLF swap was adopted. Prior to the VLF swap, historical growth in assessed valuation and VLF revenue had been fairly comparable.

City and County Fiscal Benefits Vary Significantly. While most cities and counties have benefited from the faster growth of VLF swap payments, some cities and counties with less growth in assessed valuation or more growth in population have received less benefit from the VLF swap than other cities and counties. Our estimates of the benefits (or losses) of individual cities and counties—measured in terms of the percentage gain or loss in VLF swap payments relative to VLF revenue losses—range from losses of a few percent to gains in excess of 80 percent. In terms of the two counties that have insufficient Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund (ERAF) (Amador and San Mateo), our analysis indicates that local governments in these counties have benefited under the VLF swap, but not more than most other cities and counties.

Choice to Tie VLF Swap Payments to Assessed Value Was Significant. In enacting the VLF swap, the state departed from its prior policy of replacing city and county VLF revenue losses dollar for dollar and instead linked growth in VLF swap payments to growth in assessed valuation. Had the state adopted a mechanism that provided for reimbursement of city and county actual VLF revenue losses only, annual payments to cities and counties would be about $2 billion less today than under the VLF swap. This would reduce the occurrence of insufficient ERAF, including eliminating Amador and San Mateo’s status as counties with insufficient ERAF.

How Should Compensation Be Provided to Cities and Counties?

After deciding how much compensation to provide to local governments, the next decision for the Legislature is to design a financing mechanism to provide the funds. Given the Constitution’s many provisions limiting state authority over local finance, we see only two primary options: provide the compensation in the annual state budget or through a redirection of certain local education agency property tax revenues. We discuss these alternatives below.

Annual State Budget Appropriations. In the 2012–13 state budget, the Legislature addressed insufficient ERAF by providing the affected local governments with a one–time allocation from the General Fund. Continuing this approach in future years would allow the Legislature to weigh the expense of providing insufficient ERAF compensation against other state spending priorities on an annual basis. On the other hand, subjecting insufficient ERAF compensation to annual review would reduce revenue security for cities and counties. We note that the Legislature designed the current triple flip and VLF swap payment mechanism to be controlled at the local level with the objective of giving local government revenue security.

Redirect Property Taxes From Some Local Educational Entities. Current law allows auditors to redirect property taxes from nonbasic aid K–12 and community college districts to fund the VLF swap. These districts’ property tax losses are backfilled with state aid. Current law does not allow auditors, however, to redirect (1) K–12 or community college district property taxes to fund the triple flip or (2) county offices of education (COE) and special education program property taxes to fund the triple flip or VLF swap. Expanding county auditor authority to redirect property taxes from all of these educational agencies for the triple flip and VLF swap would provide additional funding that could be used to avoid ERAF insufficiencies. Similar to K–12 and community college districts, COE and special education programs receive a particular level of annual funding through a combination of local revenues and state aid. If the property tax revenues received by COEs or special education programs decrease, the state typically provides additional state funding to achieve a specified funding level. Therefore, total funding to these entities likely would not decrease if county auditors were permitted to redirect some of their property taxes to fund the triple flip and VLF swap.

Our review indicates that redirecting property tax revenues from COEs and special education programs would cover most, but not all, of the current costs of insufficient ERAF in Amador and San Mateo Counties. Similarly, this funding mechanism might not be sufficient in future years if the scope of insufficient ERAF is constant or expands. Consequently, if the Legislature wishes to provide full reimbursement for all triple flip and VLF swap funding shortfalls, supplemental General Fund appropriations will be required to compensate cities and counties.

The Redirection Option Raises Two Important Considerations. In considering this option, the Legislature should be aware of two important considerations. First, if the actual amount of property taxes allocated to COEs or special education programs in a given year ends up being less than was expected at the time the state budget was enacted, additional state funding would need to be provided if COEs and special education programs are to reach their specified funding levels. State policies addressing this situation differ between COEs and special education programs. As with K–12 districts, COE funding shortfalls are backfilled automatically with additional state aid. On the other hand, an additional state appropriation would be needed to backfill special education funding shortfalls—similar to community colleges. While the issue of differing approaches to backfilling local educational agencies’ property tax revenues extends far beyond insufficient ERAF and the scope of this report, the Legislature should be aware that the ramifications of shifting property taxes from local educational agencies to fund the triple flip and VLF swap may vary across entities. Second, the Constitution constrains the Legislature’s ability to alter the allocation of property tax revenues—even in cases when the state would be providing cities and counties with increased property taxes. Legislation authorizing property taxes to be shifted from COE or special education programs may require approval by two–thirds of both houses of the Legislature.

Conclusion

Over the last two years, local governments in two counties—Amador and San Mateo—did not receive enough revenue to offset two complex state–local financial transactions: the triple flip and VLF swap. It is likely this funding insufficiency, commonly called insufficient ERAF, will continue in future years, requiring state action if the affected local governments are to receive their full triple flip and VLF swap payments. In addressing future claims of insufficient ERAF, the Legislature will be faced with the difficult decisions of how much compensation cities and counties should receive and how it should be provided. Ultimately, in making these decisions, the Legislature to will need to balance trade–offs between providing funding for state versus local government programs and weigh implicit commitments made by previous Legislatures.