This publication summarizes California’s 2013–14 spending plan, including legislative and gubernatorial action through October 2013. A preliminary electronic version was released prior to gubernatorial actions on bills passed by the Legislature in August and September 2013. This final published version reflects gubernatorial action on those bills and various minor changes.

Figure 1 displays state and federal spending in the 2013–14 Budget Act.

Figure 1

Total State and Federal Fund Expenditures

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Fund Type

|

Revised

|

Enacteda

2013–14

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

General Fundb

|

$86,404

|

$95,665

|

$96,281

|

$617

|

0.6%

|

|

Special funds

|

33,853

|

38,656

|

42,022

|

3,366

|

8.7

|

|

Budget Totals

|

$120,257

|

$134,321

|

$138,303

|

$3,982

|

3.0%

|

|

Selected bond funds

|

$6,104

|

$12,261

|

$6,997

|

–$5,264

|

–42.9%

|

|

Federal funds

|

73,063

|

81,299

|

87,566

|

6,266

|

7.7

|

Total State and Federal Funds Spending

The state spending plan assumes total budget expenditures of $138.3 billion from the General Fund and special funds, an increase of 3 percent over 2012–13. This consists of $96.3 billion from the General Fund and Education Protection Account created by Proposition 30 (2012), as well as $42 billion from special funds. The budget estimates that spending from federal funds in 2013–14 will total $87.6 billion, an increase of 7.7 percent over 2012–13. (Unless otherwise specified, figures in this publication generally reflect the administration’s official scoring as of late June 2013. As such, figures do not reflect budget–related legislation enacted between July and October, including Chapter 310, Statutes of 2013 [SB 105, Steinberg], which appropriated $315 million to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation [CDCR] for 2013–14.)

General Fund Revenues

Figure 2 displays the key revenue assumptions underlying the 2013–14 Budget Act.

Figure 2

2013–14 Budget Act Revenue Assumptions

General Fund and Education Protection Account Combined (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12 Estimated

|

2012–13 Estimated

|

2013–14 Enacted

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Personal income tax

|

$54,261

|

$63,901

|

$60,827

|

–$3,074

|

–4.8%

|

|

Sales and use tax

|

18,658

|

20,240

|

22,983

|

2,743

|

13.6

|

|

Corporation tax

|

7,233

|

7,509

|

8,508

|

999

|

13.3

|

|

Subtotals, “Big Three” taxes

|

($80,152)

|

($91,650)

|

($92,318)

|

($668)

|

(0.7%)

|

|

Insurance tax

|

$2,165

|

$2,156

|

$2,200

|

$44

|

2.0%

|

|

Other revenues

|

2,959

|

2,641

|

2,249

|

–392

|

–14.8

|

|

Transfers and loans

|

1,509

|

1,748

|

331

|

–1,416

|

–81.0

|

|

Totals

|

$86,786

|

$98,195

|

$97,098

|

–$1,096

|

–1.1%

|

Budget Projects Lower Revenues in 2013–14. The spending plan estimates General Fund and Education Protection Account revenues of $97.1 billion in 2013–14, a decrease of 1.1 percent over 2012–13. The budget assumes that one–time state revenue associated with the 2012 Facebook initial public offering and decisions made by wealthy individuals to accelerate income from 2013 to 2012 due to changes in federal tax policy will inflate 2012–13 revenues, contributing to a year–over–year decline in 2013–14.

The Condition of the General Fund

Figure 3 summarizes the estimated General Fund condition for 2012–13 and 2013–14.

Figure 3

General Fund Condition

General Fund and Education Protection Account Combined (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2012–13

|

2013–14a

|

Percent Change

|

|

Prior–year balance

|

–$1,658

|

$872

|

|

|

Revenues and transfers

|

98,195

|

97,098

|

–1.1%

|

|

Total resources available

|

$96,537

|

$97,970

|

|

|

Total expenditures

|

$95,665

|

$96,281

|

0.6%

|

|

Fund balance

|

$872

|

$1,689

|

|

|

Encumbrances

|

$618

|

$618

|

|

|

Reserve

|

$254

|

$1,071

|

|

2012–13 Projected to Be First Year Since 2007–08 to End With a Reserve. The administration’s May Revision estimates of 2012–13 revenues were about $2.3 billion higher than when the 2012–13 spending plan was adopted last year. As discussed in “Chapter 2,” these higher revenues result in $2.5 billion in additional expenditures under the Proposition 98 minimum funding guarantee for K–14 education. In addition, higher expenditures in other areas contributed to the estimated 2012–13 General Fund ending balance being about $694 million lower than was assumed in the 2012–13 spending plan. Nevertheless, under the spending plan 2012–13 would end with a $254 million reserve, the first such year–end positive balance in the reserve since 2007–08.

2013–14 Projected to End With a $1.1 Billion Reserve. The spending plan assumes General Fund and Education Protection Account revenues of $97.1 billion and expenditures of $96.3 billion. Those assumptions, however, are based on the administration’s official scoring as of late June 2013. As such, they do not include budget–related legislation enacted between July and October, including Chapter 310, which appropriated $315 million (General Fund) to CDCR for 2013–14. After accounting for this and other post–budget act legislation, 2013–14 would end with a roughly $700 million General Fund reserve.

Major Features of the 2013–14 Budget Plan

Contrary to recent years in which the state took actions to address multibillion dollar budget shortfalls, the spending plan augments programmatic spending in a few areas. The major features of the spending plan are summarized below. These actions and others are described in more detail in “Chapter 2.”

School Funding. Major features of the Proposition 98 budget include $2.1 billion for a new formula to distribute funding amongst schools, $1.25 billion in one–time funding to implement the Common Core State Standards, and $4.3 billion in 2012–13 and 2013–14 combined to pay down deferrals to schools and community colleges.

Medi–Cal Expansion. Legislation adopted in a special session implements a state–based plan to expand Medi–Cal. Specifically, the plan exercises an option pursuant to federal health care reform to expand eligibility for Medi–Cal to cover more than one million additional low–income adults who will become eligible for health care coverage on January 1, 2014.

Selected Restorations of Funding From Prior Year Program Cuts. The budget plan includes spending increases for a few programs that were cut or eliminated in recent years. The most significant of these actions provide a $63 million ongoing augmentation for the judicial branch and a partial restoration of adult dental benefits under Medi–Cal ($17 million, partial–year effect).

Other Program Augmentations. The spending plan also includes $143 million in one–time funding for mental health services infrastructure and provides enhanced mental health and substance use disorder services ($67 million, partial–year effect). In addition, budget–related legislation augments California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) grants by diverting revenue growth in the Local Revenue Fund created by 1991 realignment that otherwise would have increased funding for county health programs and other social services programs. This action is assumed to have no General Fund effect in 2013–14. The spending plan also creates a new financial aid program for certain students at the University of California and California State University beginning in the 2014–15 school year.

Changes to 1991 Realignment. The Medi–Cal expansion discussed above shifts much of the responsibility for providing indigents with health care from the counties to the state. To capture the savings that counties are expected to experience under the expansion, the budget redirects funding from 1991 realignment to the benefit of the General Fund. The spending plan assumes the state savings to be $300 million in 2013–14.

The Governor signed the 2013–14 Budget Act on June 27, 2013. Between that date and October 2013, the Governor signed 44 budget–related bills into law. The budget and related bills are listed in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Selected Budget–Related Legislation

|

Bill Number

|

Chapter

|

Author

|

Subject

|

|

AB 110

|

20

|

Blumenfield

|

2013–14 Budget Act

|

|

AB 74

|

21

|

Budget Committee

|

Human services

|

|

AB 75

|

22

|

Budget Committee

|

Transfer of DADP programs to DHCS and DPH

|

|

AB 81

|

161

|

Budget Committee

|

Public safety: domestic abuse

|

|

AB 82

|

23

|

Budget Committee

|

Health

|

|

AB 85

|

24

|

Budget Committee

|

1991 realignment, CalWORKs grants

|

|

AB 86

|

48

|

Budget Committee

|

K–14 education and child care

|

|

AB 89

|

25

|

Budget Committee

|

Developmental services

|

|

AB 92

|

26

|

Budget Committee

|

State government

|

|

AB 93

|

69

|

Budget Committee

|

Enterprise zones

|

|

AB 94

|

50

|

Budget Committee

|

Higher education, MCS

|

|

AB 97

|

47

|

Budget Committee

|

K–12 LCFF

|

|

AB 98

|

27

|

Budget Committee

|

Seismic Safety Commission

|

|

AB 101

|

354

|

Budget Committee

|

Amendments to the 2013–14 Budget Act

|

|

AB 106

|

355

|

Budget Committee

|

Enterprise zones

|

|

AB 113

|

3

|

Budget Committee

|

Amendments to the 2012–13 Budget Act

|

|

AB 234

|

449

|

Gatto

|

Claims against the state

|

|

AB 478

|

391

|

Gomez

|

Employee compensation MOU

|

|

AB 701

|

393

|

Quirk–Silva

|

Orange County—property taxes

|

|

SB 67

|

4

|

Budget Committee

|

IHSS

|

|

SB 68

|

5

|

Budget Committee

|

Amendments to 2012–13 Budget Act

|

|

SB 71

|

28

|

Budget Committee

|

State government

|

|

SB 73

|

29

|

Budget Committee

|

Proposition 39 implementation

|

|

SB 74

|

30

|

Budget Committee

|

Corrections

|

|

SB 75

|

31

|

Budget Committee

|

Courts

|

|

SB 76

|

32

|

Budget Committee

|

Public safety

|

|

SB 78

|

33

|

Budget Committee

|

Tax on managed care organizations

|

|

SB 82

|

34

|

Budget Committee

|

Mental health wellness act

|

|

SB 85

|

35

|

Budget Committee

|

Transportation

|

|

SB 89

|

36

|

Budget Committee

|

Augmentations to the 2012–13 Budget Act

|

|

SB 90

|

70

|

Galgiani

|

Economic development

|

|

SB 91

|

49

|

Budget Committee

|

Amendments to LCFF

|

|

SB 94

|

37

|

Budget Committee

|

Medi–Cal managed care, IHSS, and CCI

|

|

SB 96

|

356

|

Budget Committee

|

Resources and environmental protection

|

|

SB 97

|

357

|

Budget Committee

|

K–12 LCFF, MCS, Proposition 39, and other education provisions

|

|

SB 98

|

358

|

Budget Committee

|

Health and human services

|

|

SB 99

|

359

|

Budget Committee

|

Active transportation program

|

|

SB 100

|

360

|

Budget Committee

|

Public finance

|

|

SB 101

|

361

|

Budget Committee

|

Health

|

|

SB 102

|

397

|

Budget Committee

|

Employee compensation MOU

|

|

SB 105

|

310

|

Steinberg

|

Prisons

|

|

SB 239

|

657

|

Hernandez

|

Hospital quality assurance fees

|

|

ABX1 1

|

3

|

John A. Pérez

|

Medi–Cal ACA implementation

|

|

SBX1 1

|

4

|

Hernandez

|

Medi–Cal ACA implementation

|

|

SCA 3

|

123

|

Leno

|

Mandates

|

Significant Operating Surpluses Estimated to Produce $1 Billion Reserve. On January 10, 2013, the Governor released his 2013–14 budget proposal, which included General Fund and Education Protection Account revenues of $98.5 billion and expenditures of $97.7 billion. The administration estimated that a $2.4 billion operating surplus in 2012–13 would be sufficient to erase the $2.2 billion 2011–12 deficit. The administration also projected that the resulting $167 million ending balance for 2012–13 and a $851 million operating surplus in 2013–14 would produce a $1 billion reserve at the end of 2013–14.

Governor’s May Revision Revenue Estimates Increase Slightly. The administration’s revenue estimates at the May Revision grew by $749 million for 2011–12, 2012–13, and 2013–14 combined. (This total excludes a $500 million loan to the General Fund from cap–and–trade revenues, which is booked on the revenue side of the state budget.) The May Revision contained a few major proposals, the most noteworthy of which realigned some fiscal responsibilities for CalWORKs, CalWORKs–related child care, and CalFresh from the state to counties. That proposal was estimated to achieve $300 million in General Fund savings in 2013–14, growing to $1.3 billion in savings by 2015–16.

Legislature Passes Budget Package. Our office’s May 2013 revenue forecast projected considerably higher revenues than did the administration’s May revenue forecast. Specifically, we estimated about $3.2 billion higher General Fund and Education Protection Account revenues across 2011–12, 2012–13, and 2013–14 combined. The most significant difference in our forecasts was our higher assumed level of capital gains and resulting personal income tax revenues in 2013–14. During hearings in late May, the budget committees in the Senate and Assembly adopted our office’s revenue estimates. After negotiations with the Governor, however, the Legislature passed a budget package that incorporated the administration’s lower revenue estimates. As discussed in “Chapter 2,” that package included a modified version of the administration’s realignment proposal that did not affect CalWORKs–related child care or CalFresh.

Budget Package Signed by Governor. The budget package was signed by the Governor on June 27, 2013. Notably, aside from one action to correct a technical error in the Franchise Tax Board budget, the Governor did not use his line–item veto authority to reduce or eliminate non–Proposition 98 General Fund spending. The Governor did, however, reduce spending from other funds by $5.6 million.

Legislature Adopts Additional Budget–Related Legislation. The Legislature sent several budget–related bills to the Governor in late June and early July. These included bills that addressed issues related to the California Public Records Act and Local Agency Ethics mandates. In addition, the Legislature passed AB 93 to phase out Enterprise Zones over several years and replace them with: (1) a partial sales tax exemption for purchases of certain manufacturing equipment, (2) a narrowly focused hiring tax credit, and (3) a program to provide tax credits to select businesses on a case–by–case basis.

Governor Signs Legislation to Address Prison Population. In September 2013, the Governor signed Chapter 310, which provides $315 million (General Fund) to CDCR to address a federal order requiring the state to reduce the prison population. Chapter 310 is described in more detail in “Chapter 2.”

Approved by voters in 1988, Proposition 98 established a set of rules relating to education funding. Most importantly, Proposition 98 established a funding requirement commonly referred to as the minimum guarantee. Each year the minimum guarantee is determined by one of three formulas, known as “tests.” The tests take into account a number of inputs, including General Fund revenues, per capita personal income, and K–12 average daily attendance (ADA). In certain cases, the state can provide less than otherwise required, but it must keep track of a resulting “maintenance factor” obligation. Moving forward, the state is required to accelerate growth in Proposition 98 funding until the maintenance factor is retired—at which time base funding is at least as high as it would have been absent the earlier reduction. The guarantee is met using both state General Fund and local property tax revenues. Proposition 98 is the main funding source for K–12 education, the California Community Colleges (CCC), and state–subsidized preschool.

Below, we walk through changes in the 2012–13 and 2013–14 Proposition 98 minimum guarantees and describe major changes in Proposition 98 spending. In the next two main sections of this chapter, we discuss the child care and higher education budgets in more detail. (In addition, the online version of this report contains a link to a packet of detailed tables relating to various aspects of the education budget.)

2012–13 Minimum Guarantee Up $2.9 Billion Due to Increases in Revenues. As Figure 1 shows, the revised 2012–13 minimum guarantee is $56.5 billion—$2.9 billion higher than the amount estimated in the 2012–13 Budget Act. The bulk of this increase—$2.5 billion—is due to General Fund revenues that count toward the guarantee being $2.4 billion higher than estimated in the 2012–13 spending plan. The growth in General Fund revenues has such a large effect on the minimum guarantee (more than dollar for dollar) because of the manner in which the budget plan makes maintenance factor payments. (Test 1 is operative in 2012–13 and the maintenance factor is being paid on top of the Test 1 rather than Test 2 level.) The minimum guarantee also increases by $364 million as a result of higher baseline property tax revenues. Because 2012–13 is a Test 1 year—in which the state provides a fixed percentage of General Fund revenues regardless of property tax revenues—an increase in baseline property tax revenues results in an increase in the minimum guarantee. (The budget package adopts LAO local property tax estimates in some cases and Department of Finance [DOF] estimates in other cases, as described in the box below.)

Budget Package Relies on Combination of Two Offices’ Local Property Tax Estimates

The budget package relies on a combination of LAO and Department of Finance (DOF) local property tax estimates. (Both offices prepared revenue forecasts in May 2012.) Specifically, the budget package uses:

- LAO estimates for 2012–13 and 2013–14 baseline property tax revenues.

- DOF estimates of 2012–13 redevelopment agency (RDA) property tax revenues (both ongoing

tax–increment revenues and one–time liquid assets).

- LAO estimates of 2013–14 RDA tax–increment revenues.

- DOF estimates of 2013–14 RDA liquid assets.

Figure 1

Proposition 98 Funding

(In Millions)

|

|

2011–12

Final

|

|

2012–13

|

|

2013–14

|

|

Budget Act

|

Revised

|

Change

|

Enacted

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Preschool

|

$368

|

|

$481

|

$481

|

—

|

|

$507

|

$26

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

General Fund

|

$29,317

|

|

$32,828

|

$36,195

|

$3,366

|

|

$34,693

|

–$1,502

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

12,125

|

|

14,342

|

13,760

|

–582

|

|

13,936

|

175

|

|

Subtotals

|

($41,443)

|

($47,170)

|

($49,955)

|

($2,785)

|

|

($48,628)

|

(–$1,327)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

General Fund

|

$3,279

|

|

$3,415

|

$3,701

|

$285

|

|

$3,742

|

$42

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

1,977

|

|

2,403

|

2,251

|

–152

|

|

2,291

|

40

|

|

Subtotals

|

($5,256)

|

($5,818)

|

($5,951)

|

($133)

|

|

($6,033)

|

($82)

|

|

Other Agencies

|

$83

|

|

$79

|

$78

|

–$1

|

|

$78

|

—

|

|

Unallocateda

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

$35

|

$35

|

|

Totals

|

$47,149

|

$53,549

|

$56,465

|

$2,917

|

|

$55,281

|

–$1,184

|

|

General Fund

|

$33,047

|

|

$36,804

|

$40,454

|

$3,651

|

|

$39,055

|

–$1,399

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

14,102

|

|

16,745

|

16,011

|

–734

|

|

16,226

|

215

|

Total 2012–13 Local Property Tax Revenues Down More Than $700 Million. Despite higher baseline property tax revenues, total 2012–13 local property tax revenues are $734 million lower than in the 2012–13 Budget Act. This difference is explained by changes in redevelopment agency (RDA) property tax revenues. Actual 2012–13 property tax revenues from RDAs are $1.1 billion lower than assumed in the 2012–13 budget plan. The state adjusts the Proposition 98 calculation such that changes to RDA property tax revenues have no effect on the minimum guarantee. These lower RDA property tax revenues, however, do result in higher General Fund costs. As a result of the year–over–year increase in the minimum guarantee coupled with the decrease in overall local property tax revenues, Proposition 98 General Fund costs increase $3.7 billion in 2012–13. (The budget package allows DOF to authorize up to an additional $100 million in Proposition 98 General Fund spending in 2012–13 if RDA revenues for community colleges come in lower than anticipated.)

$1.2 Billion Decrease in 2013–14 Guarantee Caused by “Spike Protection” Provision. Under the budget plan, General Fund revenues that count toward the guarantee increase slightly (less than 1 percent) from 2012–13 to 2013–14. This slight year–over–year growth increases the minimum guarantee by $300 million. This increase is more than offset by a reduction in the guarantee due to the spike protection provision of Proposition 98. (This provision will take effect for the first time in 2013–14.) In a year when the minimum guarantee increases at a much faster rate than per capita personal income, the spike protection provision excludes a portion of Proposition 98 funding from the calculation of the minimum guarantee the subsequent year. This essentially prevents a portion of the prior–year Proposition 98 appropriation from permanently increasing the minimum guarantee in future years. Because the minimum guarantee increases much faster than per–capita personal income in 2012–13, the spike protection provisions require that $1.5 billion in 2012–13 Proposition 98 funding be excluded from the 2013–14 Proposition 98 calculation, reducing the 2013–14 minimum guarantee by a like amount. Accounting for both changes, the minimum guarantee is a net $1.2 billion lower in 2013–14 ($55.3 billion) than 2012–13 ($56.5 billion).

2013–14 Local Property Tax Revenues Up More Than $200 Million. Under the budget plan, total property tax revenues increase by $215 million from 2012–13. The budget plan assumes baseline property tax revenues increase $776 million. This increase is offset by RDA property tax revenues being $561 million lower than in 2012–13. (Similar to 2012–13, the budget package authorizes a General Fund backfill for schools and community colleges if RDA property tax revenues come in lower than anticipated in 2013–14.) Because 2013–14 is a Test 3 year, the increase in property tax revenues results in reduced General Fund Proposition 98 costs.

Figure 2 shows all major Proposition 98 spending changes in 2012–13 and 2013–14. In this section, we highlight the major changes each year and describe how those changes affect per–student funding. In the next section, we discuss the major Proposition 98 augmentations in more detail.

Figure 2

Proposition 98 Spending Changes

(In Millions)

|

2012–13 Budget Act

|

$53,549

|

|

Pay down additional deferrals

|

$1,769

|

|

Fund Common Core implementation (one time)

|

1,000

|

|

Revenue limit adjustments

|

293

|

|

Other technical adjustments

|

–145

|

|

Total 2012–13 Changes

|

$2,917

|

|

Revised 2012–13 Spending

|

$56,465

|

|

Technical Adjustments

|

|

|

Fund growth and COLA for certain categorical programsa

|

$114

|

|

Revenue limit adjustments

|

43

|

|

Other technical adjustments

|

–26

|

|

Use prior–year unspent funds

|

–94

|

|

Adjust for one–time actions

|

–4,994

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

|

Implement LCFF for districts and charter schools

|

2,052

|

|

Allocate funds for energy projectsb

|

406

|

|

Fund Common Core implementation (one time)

|

250

|

|

Fund Career Pathways program (one time)

|

250

|

|

Pay down deferrals

|

242

|

|

Augment mandate block grant

|

50

|

|

Implement LCFF for county offices of education

|

32

|

|

Increase preschool slots

|

26

|

|

Establish CCEE to provide academic advice and assistance

|

10

|

|

Other changesc

|

37

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

Fund enrollment growth

|

89

|

|

Provide COLA

|

88

|

|

Increase categorical funding

|

88

|

|

Allocate funds for energy projectsb

|

50

|

|

Pay down deferrals

|

30

|

|

Provide building maintenance funding (one time)

|

30

|

|

Fund adult education planning grants

|

25

|

|

Fund new technology initiative

|

17

|

|

Total 2013–14 Changes

|

–$1,184

|

|

2013–14 Proposition 98 Spending Level

|

$55,281

|

Changes in 2012–13 Spending. As shown in the top part of Figure 2, the $2.9 billion increase in 2012–13 Proposition 98 spending is primarily used to pay down deferrals and implement a new one–time initiative relating to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS).

Major Changes in 2013–14 Spending—K–12 Education. For K–12 education, the largest 2013–14 augmentation ($2.1 billion) is for implementing the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) for school districts. Other major 2013–14 K–12 augmentations include $406 million in grants and loans for energy projects, an additional $250 million on a one–time basis for the CCSS initiative, $250 million on a one–time basis for a new Career Pathways program, $50 million to augment the mandate block grant, $32 million to implement the LCFF for county offices of education (COEs), and $10 million to establish the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE) to provide low–performing school districts with academic assistance.

Major Changes in 2013–14 Spending—Community Colleges. Major CCC augmentations in 2013–14 include $88 million for various categorical programs, $50 million in grants and loans for energy projects, $30 million on a one–time basis for building maintenance projects (including replacing instructional equipment and library materials), $25 million for adult education planning grants, and $17 million for a new CCC technology initiative.

Other Changes in 2013–14 Spending. The budget also further pays down both K–12 and CCC deferrals. Additionally, the budget includes a 1.57 percent cost–of–living adjustment (COLA) for certain K–12 categorical programs and CCC general–purpose apportionment funding. The budget includes a slight increase to reflect 0.2 percent growth in K–12 ADA and an $89 million increase to fund 1.63 percent enrollment growth at the community colleges. The budget also provides a $26 million (5 percent) increase to the part–day/part–year State Preschool program to support approximately 7,100 new preschool slots. (The Governor vetoed $5 million for preschool—bringing the augmentation down from $31 million.)

K–12 Per–Student Funding Up 5.5 Percent Year Over Year. Given the budget package devotes virtually all of the increase in 2012–13 funding for one–time purposes, ongoing funding per student in 2012–13 changes only negligibly from the 2012–13 Budget Act. In 2013–14, despite fewer overall resources compared to 2012–13, much less funding is designated for paying down deferrals. This frees up funds in 2013–14 that can be used for other purposes. In total, the budget includes a $2.6 billion increase in K–12 ongoing funding. Ongoing funding per student (as measured by ADA) increases from $7,590 in 2012–13 to $8,005 in 2013–14—an increase of $415 (5.5 percent).

CCC Per–Student Funding Up 5 Percent Year Over Year. Like K–12 education, increases in 2012–13 funding for CCC are primarily used for one–time purposes (paying down additional deferrals), with virtually no change in ongoing funding per student. In 2013–14, also similar to K–12 education, much less funding is designated for paying down CCC deferrals, thereby freeing up funds in 2013–14 for other purposes. In total, the budget includes a $350 million increase in CCC ongoing funding. Ongoing funding per full–time equivalent (FTE) CCC student increases from $5,524 in 2012–13 to $5,792 in 2013–14—an increase of $268 (5 percent).

LCFF for School Districts and Charter Schools

Budget Package Contains Major Restructuring of K–12 Funding System. The budget package includes a major restructuring of the state’s funding system for school districts and charter schools. The new LCFF system replaces existing funding formulas for revenue limits and most categorical programs with a weighted student funding formula. Over the course of implementation, districts will receive additional funding to reduce the same share of the gap between their existing per–pupil funding rates and their targets under the LCFF. Full implmentation of the LCFF is expected to take eight years (with full implementation in 2020–21) and cost $18 billion (not accounting for future COLA costs). The 2013–14 Budget Act provides first–year funding of $2.1 billion. This is expected to close 12 percent of each district’s gap.

New Funding Formula Has Grade–Span Base Rates. Figure 3 highlights the major components of the LCFF. As shown in the figure, the LCFF establishes base rates for four grade spans. The LCFF adjusts the base rates by providing additional funding intended to be used for class size reduction (CSR) in the K–3 grades and career technical education in high school. (Hereafter, the term “base rates” includes the additional funding for the K–3 and high school adjustments.) Different base rates are intended to reflect the differential costs of providing education across the grade spans.

Figure 3

Overview of Local Control Funding Formula for School Districtsa

|

Formula Component

|

|

|

Initial base rate(s) (per ADA)

|

K–3: $6,8454–6: $6,9477–8: $7,1549–12: $8,289

|

|

Additional funding for K–3 and high school students (per ADA)

|

K–3: 10.4 percent of base rate.9–12: 2.6 percent of base rate.

|

|

Supplemental funding for certain student subgroups (per EL/LI student and foster youth)

|

20 percent of base rates, as adjusted for K–3 and high school.

|

|

Concentration funding

|

Each EL/LI student above 55 percent of enrollment generates an additional 50 percent of base rates as adjusted for K–3 and high school.

|

|

Economic Recovery Target (ERT)

|

Establishes an ERT assuming revenue–limit and categorical funding is restored to 2007–08 levels and revenue limits receive COLA from 2008–09 through 2020–21. Provides districts with the greater of their LCFF target or ERT (capped at the 90th percentile of all districts’ ERTs). If a district’s 2020–21 ERT is greater than its LCFF target, one–eighth of the amount needed to reach the district’s ERT is provided each year for the next eight years.

|

|

Special rules for four existing programs

|

Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grant, Home–to–School Transportation, Adult Education, and Regional Occupational Centers and Programs (see text for description of the special rules).

|

|

Programs Kept/Spending Requirements Retained

|

|

Special Education, After School Education and Safety, State Preschool, Quality Education Investment Act, Child Nutrition, Mandates Block Grant, Assessments, American Indian Education Centers and Early Childhood Education Program, Foster Youth Services, Adults in Correctional Facilities, Partnership Academies, Specialized Secondary Programs, and Agricultural Vocational Education.

|

|

Programs Eliminated/Spending Requirements Removed

|

|

Summer School Programs, Grade 7–12 Counseling, Gifted and Talented Education, Economic Impact Aid, Professional Development for Math and English, Principal Training, Educational Technology, Deferred Maintenance, Instructional Materials Block Grant, Community Day School (extra hours), Staff Development, National Board Certification Incentives, California School Age Families Education, California High School Exit Exam, Tutoring, Civic Education, Teacher Dismissal, Charter School Block Grant, Categorical Programs for New Schools, Community–Based English Tutoring, School Safety, High School Class Size Reduction, Advanced Placement Fee Waiver, International Baccalaureate Diploma Program, Student Councils, Teacher Credentialing Block Grant, Professional Development Block Grant, School and Library Improvement Block Grant, School Safety Competitive Grant, Physical Education Block Grant, Certificated Staff Mentoring, Oral Health Assessments, Alternative Credentialing.

|

Includes Supplemental Funding for English Learner and Low–Income (EL/LI) Students. Under the LCFF, districts and charter schools receive significantly more funding for EL/LI students and foster youth. For each of these students, districts receive an additional 20 percent of the base per–pupil amount. For example, an EL/LI student in grades K–3 would generate an additional $1,511 for the district (20 percent of $7,557, which reflects the K–3 base rate adjusted for CSR). In addition, districts whose EL/LI populations exceed 55 percent of their enrollment receive concentration funding. Specifically, these districts receive an additional 50 percent of the base per–pupil amount for each student above the 55 percent threshold. For the purposes of generating both supplemental and concentration funding, the formula counts each student only once (regardless of whether they are EL, LI, and/or a foster youth).

Guarantees Virtually All Districts Receive as Much as They Would Have Under Previous System. To ensure that the vast majority of districts receive at least as much as they would have under the previous system, the new system includes a component called the Economic Recovery Target (ERT). The ERT assumes the revenue limit deficit factor is retired, categorical programs are restored to 2007–08 levels, and revenue limits receive a 1.94 percent COLA every year moving forward. In most cases, if a district’s ERT is greater than its LCFF target, its funding level is to increase by one–eighth of the amount needed to reach its ERT each year for the next eight years. For the vast majority of districts, the LCFF target for 2020–21 will be higher than the ERT for 2020–21. For about 230 districts, the ERT, however, will be higher. Over the next eight years, roughly 130 of these districts will receive additional payments in excess of their LCFF payments to get them to their higher ERT. (Districts that have an ERT above the 90th ERT percentile will receive no additional funding in excess of the 90th percentile. Approximately 100 districts have rates that are this high.)

Special Rules for Four Categorical Programs. Specifically, the Targeted Instructional Improvement Grant (TIIG) does not apply toward a district’s LCFF allocation. Instead, the district’s TIIG allocation is locked in at the 2012–13 level and treated as an “add–on” to LCFF. No state spending requirements are associated with this add–on funding. Home–to–School (HTS) Transportation funding also does not apply toward a district’s LCFF allocation. The state, however, established an ongoing maintenance–of–effort (MOE) requirement that districts spend as much on HTS Transportation annually moving forward as in 2012–13. Under the new system, existing funding for adult education and Regional Occupational Centers and Programs (ROCP) do count toward a district’s LCFF allocation but districts have an MOE requirement that they spend as much on each of these two programs in 2013–14 and 2014–15 as in 2012–13.

Other Notable Changes in Spending Requirements. As shown in the bottom part of Figure 3, the LCFF removes the spending requirements associated with most existing categorical programs. In lieu of most existing categorical spending requirements, districts will have to complete Local Control and Accountability Plans (LCAPs). The LCAP is an annual plan in which districts will specify how they will spend LCFF funding to improve the education of their students and implement state priorities. Districts are required to make their LCAPs publicly available and submit them to their COE for review. Charter schools will annually submit comparable reports to their chartering authority.

Develops New Technical Assistance and Intervention System. In tandem with the new funding formula, the budget package establishes a new system of district support and intervention. Under the new system, districts that fail to improve student outcomes will receive support from their COE, an academic expert or team of experts assigned by their COE, or the newly established CCEE. (For a charter school that fails to improve student outcomes, the chartering authority would be responsible for providing or arranging technical assistance.) A district that displays persistently poor student performance also may be subject to more intensive interventions at the discretion of the State Board of Education (SBE) and State Superintendent of Public Instruction (SPI). These interventions could include the SPI changing the LCAP, revising a district’s budget, or exerting control over local school board actions (with the exception of board actions involving local bargaining agreements). With SBE approval, the SPI can assign an academic trustee to the district to implement these interventions. (For charter schools, persistently poor student outcomes can lead to the chartering authority or SBE revoking their charters.)

LCFF for COEs

Establishes New Two–Part Funding Formula for COEs. The budget package also replaces the existing COE revenue limit and categorical funding system with a new two–part funding formula (see Figure 4). The new formula has (1) one part relating to funding for operational services that COEs provide to local educational agencies (LEAs) within their respective counties and (2) a second part relating to the alternative education services COEs directly provide to students. Similar to the approach for school districts, the formula establishes a funding target for each COE, counts existing funds toward the target, and uses new funding to close the same proportional share of each COE’s gap between its existing funding level and target funding level. Full implementation of the new COE system is expected to take two years (with full implementation in 2014–15) and cost $50 million. The 2013–14 Budget Act provides first–year funding of $32 million—almost two–thirds of the funding needed to bring COEs up to their target levels.

Funds COE Operational Support. As shown in Figure 4, the new funding formula provides an operations grant for each COE based on the total number of school districts and students within the county. This grant is intended to support basic COE operations and services for LEAs in the county. Each COE has considerable discretion over the use of this funding, with most existing categorical spending requirements removed. The COEs, however, must perform certain activities for school districts within their counties, including providing fiscal oversight and verifying districts’ EL/LI student counts. As described above, the budget package also gives COEs a significant role in the new district academic support and intervention system, with COEs required to review the LCAPs submitted by school districts and provide technical assistance to districts whose plans are disapproved.

Figure 4

Overview of Local Control Funding Formula for COEs

|

Operations Grant

|

|

Funding target

|

Base funding of $655,920 per COE.Additional $109,320 per school district in the county.Additional $40 to $70 per ADA in the county (less populous counties receive higher per–ADA rates).

|

|

Alternative Education

|

|

Eligible student population

|

Students who are (1) under the authority of the juvenile justice system, (2) probation–referred, (3) on probation, or (4) mandatorily expelled.

|

|

Initial base rate

|

$11,045 per ADA.

|

|

Supplemental funding for EL, LI, and foster youth

|

Additional 35 percent of base rate.a

|

|

Concentration funding

|

Additional 35 percent of base rate for EL/LI students above 50 percent of enrollment.a

|

Funds COEs for Alternative Schools. The other part of the new funding formula is for COE–operated alternative schools, including court schools, county community schools, and community day schools. The budget package limits funding for COEs to those alternative–education students who are incarcerated, on probation, referred by a probation officer, or mandatorily expelled. (The COEs can serve other types of students through arrangements with a cooperating school district to pass through a portion of the district’s funding.) As shown in Figure 4, the structure of this part of the COE formula is similar to the formula for school districts, except that the base rate is significantly higher and different percentages are used for the supplemental and concentration grants. As with school districts, the funding generated by the supplemental and concentration grants must be used to increase or improve services for the students generating the funds.

Requires LCAPs for Alternative Education. Somewhat similar to the LCAPs that school districts must develop, the budget package requires each COE to adopt an LCAP describing its plan for serving alternative–education students and making progress towards state priorities. The COE LCAP also must describe how the COE will coordinate instruction for expelled pupils (as well as services for foster youth) within the county. If the SPI does not approve a COE’s plan, the SPI must provide technical assistance to that COE.

Includes Hold Harmless Provision. Under the new system, most of the funding COEs currently receive from revenue limits and categorical programs becomes unrestricted and is applied toward each COE’s funding target. The largest categorical program rolled into the formula is ROCP, for which COEs received about $180 million in 2012–13. (The associated MOE means COEs that ran ROCPs in 2012–13 must continue to support those activities for the next two years rather than expanding or enhancing operational services or alternative education.) In 32 of the state’s 58 counties, existing funding streams exceed the COEs’ funding target under the LCFF. The COEs are allowed to continue to receive funding in excess of their LCFF target, but the intent is that these COEs not receive funding increases until their LCFF target exceeds their 2012–13 funding level.

State–Level LCFF Implementation

Up to $4.7 Million Available for State–Level LCFF Implementation. In addition to the Proposition 98 funding provided for LCFF, the budget plan includes non–Proposition 98 General Fund augmentations for state operations relating to LCFF administration. The budget plan includes up to 22 positions and $2.7 million in ongoing non–Proposition 98 General Fund support for the California Department of Education (CDE) to implement the new LCFF fiscal provisions (11 positions, $1.4 million) as well as LCAP–related provisions (11 positions, $1.3 million). Of the combined amount included in the budget plan for CDE, 11 positions and $1.2 million are contingent on DOF approval of an expenditure plan to be submitted by CDE. The budget plan also provides $2 million in one–time non–Proposition 98 General Fund support to SBE for statutorily required activities related to LCFF. Specifically, SBE is required to (1) develop regulations regarding the use of supplemental and concentration funds by January 31, 2014 and (2) create templates by March 31, 2014 for school districts, COEs, and charter schools to use in adopting their LCAPs.

Deferral Paydowns

Total of $4.3 Billion in Deferrals Paid Down in 2012–13 and 2013–14. After four consecutive years of increasing the amount of deferrals for schools and community colleges—reaching a total of $10.4 billion in outstanding deferrals by the end of 2011–12—the 2012–13 budget plan provided $2.2 billion to reduce the amount of outstanding deferrals. As Figure 5 shows, the recently enacted budget plan makes an additional $1.8 billion in 2012–13 deferral paydowns as well as $272 million in paydowns in 2013–14. Under the budget package, $6.2 billion in outstanding deferrals remain as of the end of 2013–14.

Figure 5

State Paying Down More Than $4 Billion in Deferrals

(In Millions)

|

|

K–12

|

CCC

|

Totals

|

|

Outstanding Deferrals at End of 2011–12

|

$9,469

|

$961

|

$10,430

|

|

Deferral paydowns in 2012–13 budget package

|

2,065

|

160

|

2,225

|

|

Newly authorized 2012–13 deferral paydowns

|

1,590

|

179

|

1,769

|

|

Deferral paydowns for 2013–14

|

242

|

30

|

272

|

|

Total Paydowns

|

$3,898

|

$369

|

$4,266

|

|

Outstanding Deferrals at End of 2013–14

|

$5,571

|

$592

|

$6,164

|

CCSS Implementation

Provides $1.25 Billion for Implementing CCSS. The budget plan provides $1.25 billion in one–time funding to schools for implementing the CCSS. (Of this amount, the budget plan counts $1 billion towards meeting the 2012–13 minimum guarantee and $250 million towards meeting the 2013–14 guarantee.) The CCSS are nationally developed standards for math and English/Language Arts that the state adopted in 2010. Under current law, schools are required to align instruction to the CCSS beginning in 2014–15. The $1.25 billion in CCSS funding must be spent in 2013–14 or 2014–15 for professional development, instructional materials, and technology that assist schools in aligning instruction to the CCSS. Local governing boards are required in a series of public meetings to discuss and adopt a plan for spending the funds and must report how the funds were spent to the CDE by July 1, 2015.

State Suspends Most Existing Standardized Tests as Part of Transition to CCSS. To begin the transition to the CCSS, the Legislature adopted Chapter 489, Statutes of 2013 (AB 484, Bonilla), which suspends most of the California Standards Tests (CSTs) in 2013–14. Specifically, Chapter 489: (1) suspends all CST exams in mathematics and English–language arts; (2) requires CST science exams only in grades 5, 8, and 10; and permanently eliminates all CST history/social science exams. (Because student results on these exams are the core of the state’s Academic Performance Index, this index may not be calculated for all schools in 2013–14.) Chapter 489 makes similar changes to the California Modified Assessment (CMA), an exam taken by some students with disabilities, but makes no changes to the California Alternate Performance Assessment, an exam for students with the most significant cognitive disabilities. The savings generated by not administering CSTs and CMA is to be used to field test CCSS–aligned exams, also known as the Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium (SBAC) tests. The field test is primarily designed to assess the accuracy and reliability of SBAC test items prior to full implementation in 2014–15. The results of the field test will not be used to assess the performance of schools or students for state or federal accountability purposes.

Proposition 39

Creates $467 Million Proposition 39 Spending Plan. Passed by the voters in November 2012, Proposition 39 increases state corporate tax revenues and requires for a five–year period, starting in 2013–14, that a portion of these revenues be used to improve energy efficiency and expand the use of alternative energy in public buildings. The budget package applies the entire increase in associated corporate tax revenues to the calculations of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. The budget plan appropriates a total of $467 million for Proposition 39–related programs and support. The funds support a new grant program, new revolving loan program, and energy–related workforce training.

Grant Program for Schools and Community Colleges ($428 Million). The budget provides $428 million (Proposition 98 General Fund) for a new grant program for schools ($381 million) and community colleges ($47 million) to undertake energy projects. (The school program allows school districts, COEs, and charter schools—referred to as LEAs throughout the rest of this section—to access funding.) For LEAs, the plan distributes 85 percent of funding on a per–student basis, with the remaining 15 percent based on student eligibility for free and reduced price meals. The LEAs with fewer than 2,000 students receive a minimum grant (ranging from $15,000 to $100,000, depending on size) in lieu of the per–student allocation if the minimum grant is higher. The LEAs must prioritize projects according to certain criteria (such as age of facilities) and must receive approval from the California Energy Commission (CEC) prior to spending funds. For community colleges, the Chancellor’s Office is to allocate funding at its discretion. The CEC, in consultation with other state education and energy agencies, is to develop guidelines for LEAs and community colleges to evaluate energy benefits.

Loan Program for Schools and Community Colleges ($28 Million). The budget also provides $28 million (Proposition 98 General Fund) to the CEC to provide low– and no–interest revolving loans to LEAs and community colleges for eligible energy projects and technical assistance. (Though CEC has discretion to allocate the $28 million among LEAs and community colleges, the budget plan assumes $25 million for LEAs and $3 million for CCC.) Program documentation and review processes are to be coordinated with the grant program discussed above.

Workforce Training Programs ($8 Million). The budget supports two energy–related workforce training programs using non–Proposition 98 General Fund monies. Specifically, it provides (1) $5 million to the California Conservation Corps to be used for workforce development, such as energy audit and weatherization training, and (2) $3 million to the California Workforce Investment Board for a competitive grant program for workforce training organizations to provide energy–related work experience and job training to disadvantaged youths and veterans.

Provides $3.1 Million for State Operations. The budget plan provides a total of $3.1 million for supporting implementation of the Proposition 39 spending plan. The CEC receives $3 million (Energy Resources Program Account) for various administrative and support activities, including establishing guidelines, reviewing project expenditure plans, maintaining a database of projects, and providing technical assistance, particularly to smaller LEAs that need help conducting energy audits. In addition, CDE receives one new position, at a General Fund cost of $109,000.

Adult Education

Provides Planning Grants for Adult Education Providers to Form Regional Consortia. In an effort to improve coordination among adult education providers, the budget provides $25 million (Proposition 98 General Fund) for a new Adult Education Consortium Program. School districts and community colleges that form a regional consortium are eligible to apply for these funds. While the monies are in CCC’s budget, the budget package charges both CDE and the CCC Chancellor’s Office with awarding grants to consortium applicants. The grants, which may be spent over two years, are to be used by consortium members to develop joint plans for serving adult learners in their area. The trailer legislation specifies the content that each consortium must include in these plans, including (1) a needs assessment of adult education services within the region, (2) plans for coordinating and integrating existing programs (such as English as a second language instruction and vocational training), and (3) strategies for improving student success. By March 1, 2014, CDE and the CCC Chancellor’s Office must submit a report to the Legislature and Governor on the status of (1) the formation of regional consortia across the state and (2) grant allocations to these regional consortia. By March 1, 2015, CDE and the CCC Chancellor’s Office must submit a second report detailing the plans that regional consortia have developed and providing recommendations for improving the state’s new regional delivery system. The budget package also includes intent language for the Legislature to (1) work toward establishing common policies affecting adult schools and community colleges (such as student fee levels) and (2) appropriate new funds to regional consortia in 2015–16 to “expand and improve” adult education in the state.

Eliminates School District Adult Education Categorical Program, but Includes MOE Requirement. In a related action, the budget package eliminates school districts’ adult education categorical program and consolidates all associated annual funding ($635 million Proposition 98 General Fund) into the school district LCFF. The budget package, however, contains a requirement for school districts (through their adult schools) to maintain at least their 2012–13 level of state spending on adult education in 2013–14 and 2014–15.

Shifts School Districts’ Apprenticeship Categorical Funds to CCC. The budget also shifts the school district–run apprenticeship program (a type of adult education instruction related to job training) to the community colleges, thereby creating two CCC apprenticeship categorical programs—CCC’s existing program ($7.2 million), which is reinstated as a restricted CCC program, and the shifted school district program ($15.7 million). Though the latter (renamed the “Apprenticeship Training and Instruction” program) is within CCC’s budget, trailer legislation permits school districts to continue administering their existing apprenticeship programs using funds from this categorical program. The trailer legislation, however, requires CCC and school district apprenticeship programs to adopt common administrative policies (such as regular visits to apprenticeship classes) by early 2014.

Retains School Districts’ Adults in Correctional Facilities Categorical Program. The budget takes a separate approach for the Adults in Correctional Facilities categorical program (an adult education program operated by school districts at various county jails). Rather than folding the program into LCFF or shifting funds to CCC, the budget maintains Adults in Correctional Facilities as a restricted categorical program within school districts’ budget and provides $15 million (Proposition 98 General Fund) to reimburse 2012–13 program costs.

New Career Pathways Program

The budget provides $250 million in one–time Proposition 98 funding to create a “California Career Pathways Trust.” The primary purpose of the new program is to improve linkages between career technical (vocational) programs at schools and community colleges as well as between K–14 education and local businesses. The program authorizes several types of activities, such as creating new technical programs and curriculum. The program is open to school districts, COEs, charter schools, and community colleges. Funds are allocated through a competitive grant process. The SPI, in consultation with the CCC Chancellor’s Office and interested business organizations, is charged with reviewing grant applications. Grant funds are available for expenditure from 2013–14 through 2015–16. As a condition of receiving pathway grants, recipients must identify other fund sources (such as commitments from businesses) that will support the ongoing costs of the program. By December 1, 2016, the SPI and grant recipients must report to the Legislature and Governor on program outcomes, such as the number of students making successful transitions to the workforce. Of the amount provided for this program, $250,000 is designated for an independent evaluation. The budget package also provides CDE with $459,000 (non–Proposition 98 General Fund) for development of a data repository to track program outcomes and three staff positions.

CCC Categorical Programs

Augments Funding for Several Categorical Programs. The budget contains both one–time and ongoing increases for CCC categorical programs. Specifically, the budget provides $30 million on a one–time basis for CCC’s Physical Plant and Instructional Support program to fund primarily facility maintenance projects and instructional equipment purchases. In addition, the budget includes a total of $88.2 million in base augmentations for five other categorical programs.

- $50 million for the Student Success and Support Program, which funds various support services such as academic counseling and orientation for incoming students. Provisional language permits the CCC Chancellor to use up to $14 million of this augmentation for three new technology projects—electronic transcripts, electronic planning tools, and a common assessment system. Provisional language also reinstates it as a restricted program.

- $15 million for Extended Opportunity Programs and Services, which provides additional academic and financial support to underprepared and financially needy students.

- $15 million for Disabled Students Programs and Services, which provides support services and educational accommodations to CCC students with disabilities.

- $8 million for various services (such as child care and career counseling) provided to CCC students in the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program.

- $150,000 for the CCC Academic Senate to support the joint CCC–California State University (CSU) common course numbering initiative.

Funds New CCC Technology Program. The budget provides $16.9 million in 2013–14 for a new CCC technology initiative (with an intent to provide annual ongoing funding of $10 million beginning in 2014–15). The stated goal of the initiative is to increase student access to high–quality online courses and provide alternative ways for students to earn college credit. The funds support the development of a number of projects, with the majority of funding in 2013–14 supporting the acquisition of a common learning management system (LMS) for the CCC system. (An LMS allows faculty to post syllabi, assignments, course material, and instructional content such as video presentations. Students use the LMS to perform functions such as submitting their assignments, taking tests, and participating in online discussions with classmates.) Other projects include (1) creation of an inventory of online courses that would be offered by a consortium of community colleges and available to students throughout the CCC system, (2) a single online portal for students to find and access such courses, (3) centralized round–the–clock technical and tutorial support for these online students, (4) additional professional development for faculty teaching online courses, and (5) development of standardized “challenge tests” that allow students to obtain academic credit for learning outside the traditional classroom setting. The budget contains a March 1, 2014 requirement for the CCC Chancellor’s Office to submit a report to the Legislature and Governor on the status of these projects.

CCC Chancellor’s Office

Funds Five New Positions. The budget provides a total of $508,000 (non–Proposition 98 General Fund) to fund five new positions at the CCC Chancellor’s Office—three positions in adult education, one position in apprenticeship, and one position to support primarly the new CCC technology initiative.

Education Mandates

Adds $50 Million to Block Grant for Graduation Requirements Mandate. The budget plan increases funding for the K–12 mandates block grant from $167 million to $217 million to account for the inclusion of the Graduation Requirements mandate. Enacted in 1983, this mandate requires that schools award a high school diploma to students only if they have met all state graduation requirements, including passing a second science course. Since the mandate pertains only to high schools, the block grant allocates the $50 million augmentation on a per–student basis for high school students only. All other block grant funding continues to be distributed across all students, without regard to grade level. As a result, the 2013–14 rates for school districts are $56 per student in grades 9 through 12 and $28 per student in all other grades. For charter schools, the rate is $42 per high school student and $14 per student in all other grades. (Charter schools receive lower rates because fewer mandates apply to them.)

Limits Behavioral Intervention Plans (BIP) Mandated Activities. The budget plan modifies several state requirements collectively known as the BIP mandate that specify how schools must respond when a student with a disability exhibits behavioral problems. In general, these modifications conform state BIP requirements more closely with federal BIP requirements, thereby eliminating most associated state reimbursable mandate costs. For example, schools no longer will be required to use specific types of assessments and specific types of behavioral interventions. A few state BIP requirements that exceed federal requirements are retained, however, such as procedures relating to emergency interventions. The budget provides $230,000 in one–time federal special education funds for CDE to provide technical assistance to schools regarding the BIP changes. (The budget package makes no change to existing state law provisions requiring schools to use their state special education funds to pay for any BIP mandated activities.)

Conforms With Other Local Governments on Mandate Suspensions. The budget package suspends four education mandates that have been suspended for other local governments in recent years: Absentee Ballots, Brendon Maguire Act, Mandate Reimbursement Process, and Sex Offenders: Disclosures by Law Enforcement. The Sex Offenders disclosure mandate applied only to community colleges, with the other three mandates applying to both schools and community colleges. Though the four mandates are removed from the block grants, the budget does not decrease block grant funding. (The budget plan also adds one small mandate relating to pupil expulsions to the schools block grant without adjusting block grant funding.)

Removes One Additional Mandate From Block Grant. The budget removes the Open Meetings/Brown Act mandate from the schools and community college block grants since Proposition 30 eliminated the state’s obligation to pay local governments for performing the associated activities.

Special Education

Revises Allocation Formulas. The budget package makes three notable changes to special education funding. First, the package simplifies the state’s approach to distributing funding to special education local plan areas (SELPAs) by delinking state and federal special education allocation formulas. A conforming change revises the “statewide target rate” used to fund new students to the updated statewide average per–pupil funding rate. Second, the budget provides $2.6 million in Proposition 98 funds to fully offset federal sequestration funding cuts for preschoolers and infants/toddlers with disabilities and provides $2.1 million in federal carryover funds to partially mitigate federal sequestration funding cuts for K–12 students with disabilities. Third, the package consolidates several special education grants, as described below. (As passed by the Legislature, the budget package also included $30 million to begin equalizing special education funding rates across SELPAs, but the Governor vetoed these funds.)

Consolidates Several Special Education Grants. The budget package consolidates 11 special education categorical grants into 5 larger grants. The consolidations include the following:

- Merges funding for SELPA administrative support and regional services ($90 million) and staff development ($2.5 million) into base SELPA funding. Funds will be available for any special education purpose. (The budget continues to provide $3 million in supplemental funds for small, geographically isolated SELPAs.)

- Combines two “WorkAbility” grants into one grant while maintaining the same programmatic requirements ($40 million) to provide vocational education, training, and job placements to students with disabilities.

- Combines three grants for students with low–incidence disabilities—materials ($13.4 million), services ($1.7 million), and ROCP ($2.1 million)—into one grant with fewer spending requirements reserved for serving the same group of students.

- Combines two extraordinary cost pools ($3 million each) for subsidizing high–cost student placements into one pool with a uniform set of eligibility criteria.

- Folds funds ($200,000) formerly dedicated for assessment research into an existing larger grant ($1.1 million) used to provide technical assistance to SELPAs.

As shown in Figure 6, the 2013–14 Budget Act authorizes a total of $1.7 billion in federal funds and state non–Proposition 98 funds for subsidized child care programs. (As shown earlier in Figure 1, the budget also includes $507 million in Proposition 98 funds for the State Preschool program.) Changes in funding by child care program vary, but total funding in 2013–14 is virtually unchanged from 2012–13. As shown in the bottom part of the figure, state non–Proposition 98 General Fund support for child care programs decreases slightly ($3 million) compared to 2012–13. Additionally, the figure shows that funding from the federal Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) is anticipated to drop by $9 million. (This includes a $16 million reduction associated with federal sequestration, offset by a base increase of $7 million.) The amount of federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funding dedicated for child care increases by $10 million. The budget package for child care contains several changes, as discussed below.

Makes Caseload and Statutory Growth Adjustments. As shown in the top part of Figure 6, the budget adjusts funding for CalWORKs child care based on anticipated changes in eligible caseload, including year–to–year increases for Stage 1 ($15 million) and Stage 3 ($21 million), and a decrease for Stage 2 ($61 million). (The Stage 3 funding level adopted in the budget was $15 million too high due to a technical error, which was corrected in Chapter 354, Statutes of 2013 [AB 101, Committee on Budget].) The net change in CalWORKs child care slots due to these caseload adjustments is a decrease of 2,200 slots. Embedded in the non–CalWORKs numbers shown in Figure 6 is a $1.3 million increase to fund a statutory 0.2 percent growth adjustment for the General Child Care, Alternative Payment, and migrant child care programs. This adjustment, based on projected annual changes in the state’s population of children under age five, will fund approximately 150 new slots in these programs. (As discussed next, a separate decision was made to increase slots in these programs beyond the statutorily required growth adjustment.)

Figure 6

Child Care and Preschool Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12a

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Child Care Expenditures

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CalWORKs Child Care

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stage 1

|

$309

|

$390

|

$406

|

$15

|

4%

|

|

Stage 2

|

442

|

419

|

358

|

–61

|

–15

|

|

Stage 3

|

152

|

162b

|

183c

|

21

|

13

|

|

Subtotals

|

($903)

|

($972)

|

($961)

|

(–$11)

|

(–1%)

|

|

Non–CalWORKs Child Care

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Child Cared

|

$675

|

$465

|

$473e

|

$8

|

2%

|

|

Alternative Payment

|

213

|

174

|

177e

|

3

|

2

|

|

Other child care

|

30

|

28

|

28e

|

—

|

2

|

|

Subtotals

|

($918)

|

($666)

|

($678)

|

($11)

|

(2%)

|

|

Support programs

|

$76

|

$76

|

$74

|

–$1

|

–2%

|

|

Totals

|

$1,897

|

$1,714

|

$1,699

|

–$15

|

–1%

|

|

Child Care Funding

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

State Non–Proposition 98 General Fund

|

$1,059

|

$779

|

$776

|

–$3

|

—

|

|

Other state funds

|

8

|

14

|

—

|

–14

|

—

|

|

Federal CCDF

|

533

|

549

|

541e

|

–9

|

–2

|

|

Federal TANF

|

297

|

372

|

383

|

10

|

3

|

|

State Preschoold (Proposition 98)

|

$368

|

$481

|

$507

|

$26

|

5%

|

Increases Slots. The budget reappropriates $10 million in unspent 2012–13 child care funds to provide a total of about 1,100 new slots in the General Child Care, Alternative Payment, and migrant child care programs.

Backfills for Federal Sequestration Cuts. The budget assumes the federal sequester will decrease California’s share of the CCDF grant by $16 million (equivalent to about 1,700 child care slots), but it provides a like amount of additional state General Fund to avoid the reduction. (The 2013–14 Budget Act authorizes DOF to make the associated reductions once the federal government provides final data on the amount of sequestration reductions.)

Large General Fund Increase but Smaller Overall Increase. The budget provides a total of $18.2 billion in support for higher education in 2013–14—a 4 percent increase from 2012–13. Of this amount, $10.9 billion is state General Fund, $3.6 billion is tuition and fee revenue, $2.3 billion is local property tax revenue, and $1.3 billion is from other sources. As Figure 7 shows, General Fund support increases $1 billion from 2012–13. Of this amount, $249 million is associated with fund swaps whereas $765 million reflects an augmentation. Regarding tuition and fees, the amount paid by students is projected to decline slightly in 2013–14 as the amount covered by existing financial aid programs grows. Revenue from local property taxes is expected to increase modestly at the community colleges whereas funding from other sources is expected to decline notably, primarily due to a $262 million reduction in federal TANF funding for Cal Grants.

Figure 7

Higher Education Core Funding

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

|

General Fund

|

$2,272

|

$2,377

|

$2,844a

|

$467

|

20%

|

|

Net tuitionb

|

2,506

|

2,428

|

2,471

|

43

|

2

|

|

Other UC core funds

|

388

|

441

|

385

|

–55

|

–13

|

|

Lottery

|

30

|

37

|

37

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($5,196)

|

($5,283)

|

($5,738)

|

($455)

|

(9%)

|

|

California State University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fundc

|

$2,000

|

$2,304

|

$2,607

|

$304

|

13%

|

|

Net tuitionb

|

1,948

|

1,885

|

1,909

|

24

|

1

|

|

Lottery

|

42

|

56

|

56

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($3,990)

|

($4,245)

|

($4,572)

|

($327)

|

(8%)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$3,512

|

$3,817

|

$3,861

|

$44

|

1%

|

|

Local property tax

|

1,977

|

2,251

|

2,291

|

40

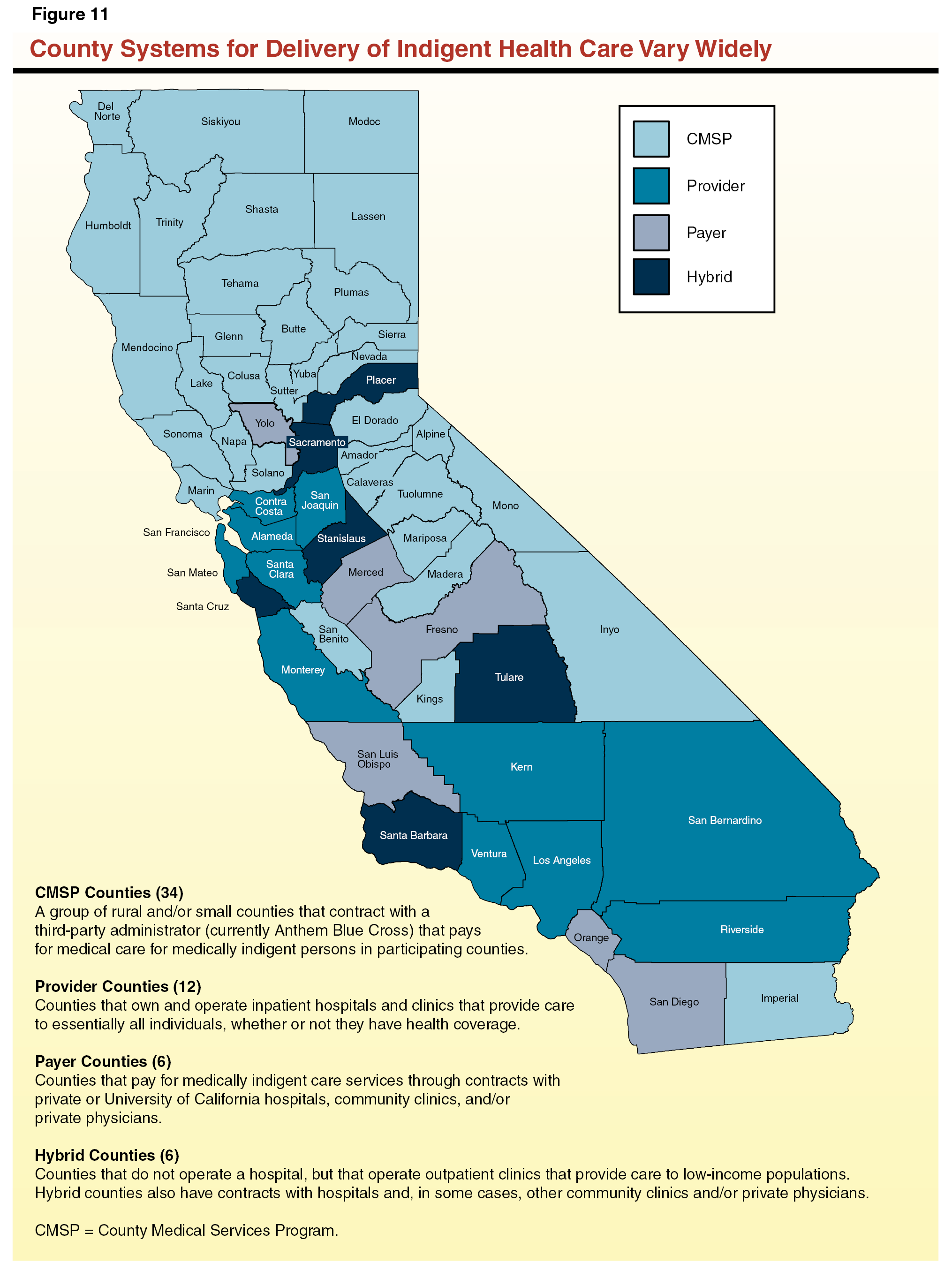

|