State Ordered to Reduce Prison Overcrowding. In August 2009, a federal three–judge panel ordered the state to reduce its inmate population to no more than 137.5 percent of the design capacity in the prisons operated by CDCR. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds that CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per cell. It also does not count inmates housed in contract beds.) Specifically, the court found that prison overcrowding was the primary reason that the state was unable to provide inmates with constitutionally adequate health care. The court’s ruling was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in May 2011. The state was initially given until June 2013 to reach the population cap.

Initial State Attempts to Comply With Population Cap. In the years following the three–judge panel’s August 2009 order to reduce prison overcrowding, the state took various actions to reduce the size of its prison population. Some of the actions taken included (1) providing counties a fiscal incentive to reduce the number of felony probationers that fail on probation and are sent to state prison, (2) increasing the number of credits inmates can earn to accelerate their release date from prison, and (3) increasing the dollar threshold for certain property crimes to be considered a felony, thus making fewer offenders eligible for prison. The most significant of these changes, however, happened with the passage of the 2011 realignment which, among other changes, shifted various criminal justice responsibilities from the state to counties. In particular, the 2011 realignment made felons generally ineligible for state prison unless they had a current or prior conviction for a serious, violent, or sex–related offense. By the end of 2012–13, realignment had reduced the prison population by tens of thousands of inmates.

Despite these actions, in May 2012, the administration notified the federal court that the prison population would not be low enough to meet the court–imposed cap. The court subsequently ordered the administration to meet the population cap by April 18, 2014. In September 2013, the Legislature passed and the Governor signed Chapter 310, Statutes of 2013 (SB 105, Steinberg), which provided CDCR with an additional $315 million in General Fund support in 2013–14 and authorized the department to enter into contracts to secure a sufficient amount of inmate housing to meet the court order and to avoid the early release of inmates which might otherwise be necessary to comply with the order. The measure also required that if the federal court modified its order capping the prison population, a share of the $315 million appropriation in Chapter 310 would be deposited into a newly established Recidivism Reduction Fund. As we discuss below, the Governor’s budget assumes that the court would extend the population cap by two years.

Court Extends Deadline to Meet Population Cap. In January 2014, the Governor requested that the court extend the deadline to reduce the prison population from April 18, 2014 to February 28, 2016. The court subsequently granted the extension. Specifically, the court ordered the state to reduce its prison population to:

- 143 percent of design capacity by June 30, 2014.

- 141.5 percent of design capacity by February 28, 2015.

- 137.5 percent of design capacity by February 28, 2016.

The court also plans to appoint a Compliance Officer. If the administration fails to meet any of the above benchmarks, the Compliance Officer would be authorized to order the release of the number of inmates required to meet the benchmark.

In addition, the federal court ordered CDCR to immediately implement certain policy changes and population reduction measures. For example, the court ordered CDCR to activate within a year “reentry hubs” at nine additional prisons that would provide various forms of cognitive behavioral therapy (such as substance abuse treatment), and employment services to high–risk inmates as they near the ends of their sentences. (Currently, four prisons operate such reentry hubs.) The court also ordered the department to explore the expansion of a recently implemented pilot program in which inmates serve the concluding portion of their prison sentence in jail in the county they will be released to. This pilot program currently only operates in San Francisco County. Moreover, the court ordered CDCR not to increase the number of inmates currently housed in out–of–state contract facilities and to make various changes to the parole process. The administration’s plan anticipated the court ordering the two–year population cap extension and these other policy changes. We discuss these changes in further detail below.

The administration’s plan to comply with the court order consists of three primary strategies: (1) contracting for bed space, (2) utilizing funding from the Recidivism Reduction Fund to support initiatives intended to reduce the prison population, and (3) implementing population reduction measures.

Contract Beds

The centerpiece of the administration’s plan to meet the court–ordered prison population cap is the use of in–state and out–of–state contract beds. As shown in Figure 1, the Governor’s budget proposes a total of $481.6 million (primarily from the General Fund) to house about 8,000 inmates in in–state contract beds and above 9,000 inmates in out–of–state contract beds in 2014–15. This represents an increase of $97.1 million and over 4,700 contract beds above the revised 2013–14 level. The Governor’s budget assumes that the two–year extension of the court–ordered population cap deadline will reduce planned expenditures on contract beds by $87.2 million in 2013–14. We note that the administration indicates that it is assessing various options for long–term compliance—as required by Chapter 310—and that this may lead to alternative measures to comply with the population cap in the long run. However, in the absence of such measures, the administration’s current plan would set the state on a course to rely on contract beds indefinitely.

Figure 1

Governor Proposes Funding for Thousands of Additional Contract Beds

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2013–14

|

|

2014–15

|

|

Change

|

|

Beds

|

Cost

|

Beds

|

Cost

|

Beds

|

Cost

|

|

Out–of–state contract beds

|

8,839

|

$234.3

|

|

8,988

|

$235.2

|

|

149

|

$1.0

|

|

In–state contract beds

|

3,413

|

150.2

|

|

7,985

|

246.4

|

|

4,572

|

96.2

|

|

Totals

|

12,252

|

$384.5

|

16,973

|

$481.6

|

4,721

|

$97.1

|

Recidivism Reduction Proposals

As noted above, the Governor’s budget assumes that expenditures on contract beds in 2013–14 will be $87.2 million lower than planned. Of this amount, the budget reflects—based on the requirements specified in Chapter 310—a deposit of $81.1 million to the Recidivism Reduction Fund for expenditure in 2014–15. (Chapter 310 requires that the remaining $6.1 million revert to the state General Fund.) Specifically, the Governor proposes allocating the $81.1 million from the Recidivism Reduction Fund as follows:

- Community Reentry Facilities—$40Million. The budget proposes $40 million for community reentry facilities. These facilities would provide services similar to those in the reentry hubs, but would not be located within a state prison. The administration indicates that inmates with less than six months of their sentence remaining would be transferred to these facilities, which would provide substance abuse treatment, education programs, and employment assistance. The facilities would be located either in county jails or in state, local, or private community facilities. The administration indicates that the facilities would eventually serve a total of 500 inmates.

- Prison Substance Abuse Treatment Expansion—$11.8Million. The Governor’s budget includes an $11.8 million augmentation and 44 new positions to expand drug treatment services within state prisons in 2014–15. This would increase the total funding for in–prison drug treatment services to $37 million in 2014–15. This augmentation is proposed to increase to $23.9 million and 91 positions in 2015–16. The proposal would expand drug treatment services to ten non–reentry hub institutions in 2014–15 and to all institutions by 2015–16.

- Integrated Services for Mentally Ill Parolees (ISMIP)—$11.3Million. The budget includes an $11.3 million augmentation for CDCR’s ISMIP program, which was established in 2007 and provides services to parolees suffering from serious mental illness and who are at risk for being homeless. Such services include case management, assistance with applying for entitlement benefits (such as Medi–Cal or veterans benefits), mental health and substance abuse services, and employment assistance. The proposed augmentation would increase total funding for ISMIP to $28 million in 2014–15 and expand the program from 600 to 900 slots.

- Rehabilitation Programming at In–State Contract Facilities—$9.7Million. The budget includes $9.7 million and 24 new positions (two positions at each contract facility to manage the treatment programs) to begin providing various forms of cognitive behavioral therapy to inmates at the 11 in–state contract facilities and the California City Correctional Center. (California City Correctional Center differs from other in–state contract facilities in that it is staffed by CDCR employees, rather than contract employees.) Specifically, the proposed funding would be used to provide cognitive behavioral therapy services, including substance abuse treatment and therapy for anger management, criminal thinking, and family relations. The funding would establish 4,008 programming slots annually (334 slots at each institution). Each institution would have 46 slots related to family relations programs and 96 slots for each of the other three program types.

- Northern California Reentry Facility (NCRF)—$8.3Million. The budget includes $8.3 million to fund the design phase of NCRF, which would provide housing and services to 600 inmates when completed. At the time of this analysis, the administration had not provided an estimate of the cost to fully renovate or operate the facility. However, we note that the Governor proposed a similar project in 2010 using funds authorized in Chapter 7, Statutes of 2007 (AB 900, Solorio), and the department indicates that NCRF will be based on the 2010 proposal. In that proposal, the administration estimated that the total cost of renovation would be about $115 million. In addition, the administration estimated that the facility would cost $45 million annually to operate, which is about $90,000 per inmate.

Population Reduction Measures

The administration’s compliance plan also includes a series of measures intended to reduce the state’s prison population. The Governor’s budget proposes $7.1 million from the General Fund to implement these measures. While the measures are expected to achieve state savings upon full implementation from having a lower prison population, the budget does not identify such savings. Instead, the administration indicates that any savings resulting from the measures would be reflected in the department’s annual population budget adjustments. As shown in Figure 2, the administration estimates that the various measures would eventually reduce the prison population by around 2,000 inmates. We note that these measures were ordered by the court. In doing so, the court waived any conflicting statute and, thus, the administration can proceed with them without legislative approval. We discuss each specific measure in greater detail below.

Figure 2

Administration’s Population Reduction Measures—Expected Reduction in Inmates

|

Proposed Measure

|

June 30, 2014

(First Population Deadline)

|

February 28, 2015

(Second Population Deadline)

|

February 28, 2016

(Final Population Deadline)

|

|

Credit enhancements

|

200

|

700

|

1,400

|

|

Parole process for second–strikers

|

—

|

175

|

350

|

|

Expanded medical parole

|

20

|

70

|

100

|

|

Elderly parole

|

50

|

70

|

85

|

|

Expanded alternative custody for women

|

—

|

60

|

80

|

|

Totals

|

270

|

1,075

|

2,015

|

Credit Enhancements. Under the state’s Three Strikes law, if an offender has one previous serious or violent felony conviction, the sentence for any new felony conviction is twice the term otherwise required under law. Such offenders are called “second strikers.” Second–strike inmates currently can earn sufficient “good–time” credits to reduce their sentence by up to 20 percent by participating in rehabilitative programs and maintaining good behavior. The administration’s plan will allow non–violent second strikers to reduce their sentence by up to 33 percent going forward. During the time these offenders are in the community earlier than they would have otherwise been, state parole agents (rather than county probation officers) will supervise them and any revocation terms will be served in state prison (rather than county jail). Following that time period, these offenders will be supervised in the community by the county, consistent with current law.

The court also ordered that the administration change the amount of credits earned by minimum custody inmates by making such inmates eligible to earn two–for–one credits. However, the court stipulated that these enhanced credit earnings can only be provided if they do not reduce the number of inmates who volunteer for fire camps. This is because fire camps also provide two–for–one credits and employ minimum custody inmates and, thus, it is possible that the change ordered by the court could reduce participation in fire camps.

Parole Process for Second–Strikers. In addition, the administration proposes allowing second strikers to have parole hearings once they have served 50 percent of their prison sentence. The administration also proposes reducing the length of time it takes to schedule parole hearings from 180 to 120 days. Finally, the court ordered CDCR to move up the parole dates of inmates who have already been granted parole, but have not yet been released.

Expanded Medical Parole. Existing state law allows for medical parole, which is a process by which inmates who are permanently incapacitated and require 24–hour care can be paroled earlier than they otherwise would have been. The Governor proposes to expand eligibility for medical parole to include additional inmates. However, at the time of this analysis, the administration had not provided detailed information specifying which additional inmates will be eligible.

Elderly Parole. The Governor also proposes to allow inmates 60 years of age or older who have served a minimum of 25 years of their sentence to have parole hearings to determine if they are suitable for release, commonly referred to as “elderly parole.”

Expanded Alternative Custody for Women. The court ordered CDCR to expand the alternative custody for women program, which places certain nonserious, non–violent, non–sex offending female inmates in the community for a portion of their sentence. At the time of this analysis, the department had not provided information detailing the specific programmatic changes being proposed and how such changes would be implemented.

Our analysis indicates that the administration’s plan is likely to achieve compliance with the court–ordered population cap in the short run. However, we find that the plan is very costly and may not be able to maintain compliance with the cap in the long run. We also find that the Governor’s proposed expenditures from the Recidivism Reduction Fund raise multiple issues.

Plan Likely Achieves Compliance in Short Run, But Is Costly and Less Certain in Long Run

In the short–term, the state faces the immediate challenge of reducing the population to 137.5 percent of design capacity by February 2016, as well as meeting two interim population deadlines before that time. To meet these immediate deadlines in the coming months, the state’s options are effectively constrained to (1) contracting with private prisons and jails to house state inmates, as proposed by the Governor; (2) releasing inmates early; or (3) some combination of contracting and early release.

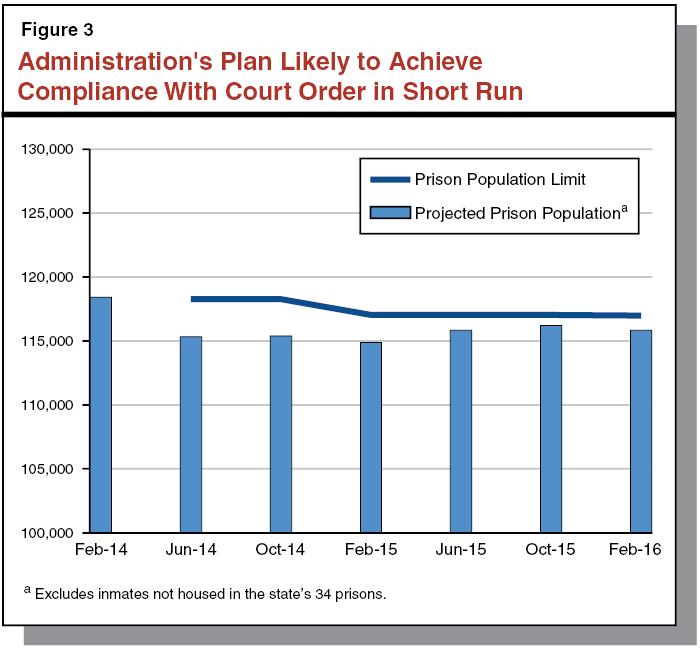

As shown in Figure 3, the administration’s plan is likely to result in compliance with each of the court–ordered population cap deadlines in the short run. Based on CDCR’s current prison population projections, the administration’s plan would bring the population in the state’s prisons below the June 2014 population limit by 2,900 inmates. Similarly, the administration’s plan would bring the population about 2,100 inmates below the February 2015 interim population limit and 1,200 inmates below the final limit in February 2016. Since CDCR’s actual prison population can vary each year from its projections, we find that reducing the population slightly below the limits is a prudent approach.

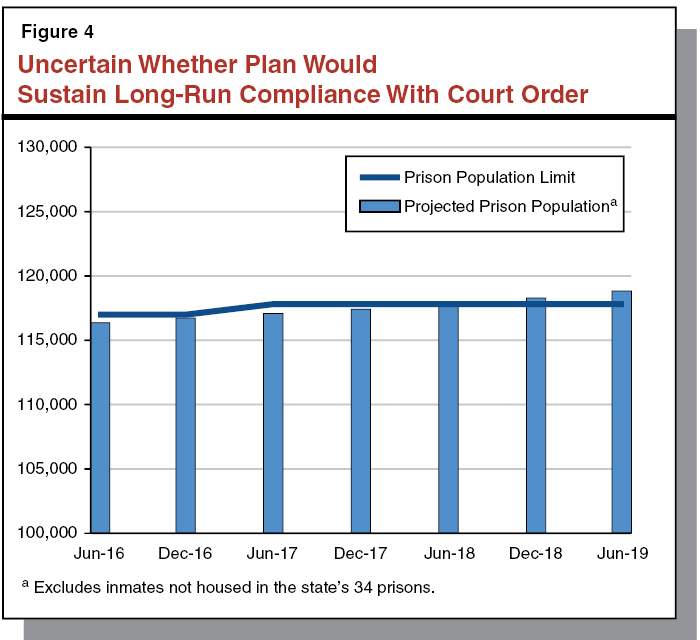

While the plan is likely to achieve compliance with the court order in the short run, current projections indicate that CDCR is on track to eventually exceed the cap. As shown in Figure 4, CDCR is currently projecting that the prison population will increase by several thousand inmates in the next few years and will reach the cap by June 2018 and exceed it by 1,000 inmates by June 2019. However, we note that this projection is subject to considerable uncertainty. Given the inherent difficulty of accurately projecting the inmate population several years in the future, it is possible that the actual population could be above or below the court imposed limit by several thousand inmates.

In addition, we are concerned that the plan’s heavy reliance on contract beds makes it a very costly approach. As we note earlier, the administration is currently considering alternatives to contracting for additional prison beds indefinitely to maintain long–term compliance with the cap. However, until such alternatives are implemented, the state will likely need to continue spending nearly $500 million annually on contract beds in order to maintain compliance with the prison population cap. In contrast, other options available to the Legislature could actually decrease state expenditures, as we discuss later in this brief.

Governor’s Recidivism Reduction Proposals Raise Multiple Issues

Our analysis also finds that the Governor’s proposed expenditures from the Recidivism Reduction Fund raise various concerns. For example, several of the proposals lack important details or are not completely developed. In addition, other proposals are unlikely to be the most cost–effective approach to reducing recidivism.

Proposals Require Ongoing General Fund Support. As described previously, the monies in the Recidivism Reduction Fund were deposited on a one–time basis from the funding appropriated by Chapter 310 that was not used for contract beds. The Governor’s budget proposes to spend all of the Recidivism Reduction Fund in 2014–15 on the various initiatives discussed above. Despite the one–time nature of this funding, all of the Governor’s budget proposals create or expand programs that would require ongoing funding to effectively reduce the prison population. In order for the administration’s plans related to the Recidivism Reduction Fund to be effective, the Legislature would likely need to provide General Fund support for these programs in the future.

ISMIP Program Benefits Unclear. In 2012, CDCR evaluated the impact of the ISMIP program. Specifically, the evaluation compared the rates at which ISMIP participants returned to prison within one year to a similar group of parolees who did not participate in the program. The study found that overall, ISMIP reduced recidivism by 30 percent. However, when the analysis controlled for important factors, such as the seriousness of an offender’s mental illness and whether offenders were connected with services immediately upon parole, the results changed substantially. In particular, the evaluation found that the recidivism rate increased slightly for inmates with less serious mental illnesses and who were connected with services immediately upon parole. While the program seems effective at treating parolees with more serious mental illnesses, it does not appear to be effective for lower acuity parolees. Despite the program’s lack of success with parolees with less serious mental illnesses, the Governor’s budget proposes expanding the program as it is currently operated—meaning that both high and lower acuity parolees would continue to receive ISMIP services.

In recent years, the program cost was an average of approximately $26,500 per slot, which is primarily due to the wide array of services that the program provides. As a result, for the program to be cost–effective, it has to result in a major reduction in the recidivism rate of its participants to fully justify the high costs. Thus, even if the program is targeted to inmates with more serious mental illnesses, it may still not be cost–effective. Also, the recidivism reduction results reported above reflect the program’s impact before the implementation of the 2011 realignment. After realignment, many of these parolees may be ineligible for state prison unless they commit a new felony. As a result, improvements in recidivism may not generate as much state savings or reduce the prison population as they did before realignment when any violation was punished with a prison term. Thus, this raises further questions about the effectiveness of the current program at reducing the state’s prison population—particularly given its high cost.

We note that, to the extent ISMIP is not cost–effective, its high cost is particularly problematic in light of the other programs that these funds could support. Rather than using $11 million to provide treatment to around 300 individuals, these funds could instead be used to fund programs that provide services to a larger population, thereby having greater effects on recidivism and the prison population.

Drug Treatment Can Be Effective if Implemented According to Best Practices. The administration’s proposal to expand in–prison substance abuse treatment holds promise. This is because data collected by CDCR indicate that recidivism rates for inmates completing in–prison drug treatment programs are lower than for those who do not. This data provides some evidence that the department’s programs may be effective. It does not, however, provide sufficient basis to conclude definitively that the programs are effective because the department did not use rigorous analytical methods for evaluating the programs. For example, the department made no attempt to account for potential differences between inmates who chose to complete the programs and those who did not (such as by randomly assigning inmates to participate in the program). Currently, there is very little recent independent research using rigorous analytical methods to evaluate the cost–effectiveness of the in–prison drug treatment services delivered by CDCR. However, numerous pieces of research from other states suggest that—if implemented consistent with best practices—substance abuse treatment can be a cost–effective way to reduce recidivism. It remains unclear, however, if CDCR is implementing best practices.

Rehabilitation Programming for Inmates in Contract Facilities Not Well Planned. As mentioned earlier, CDCR is planning to transition to a reentry hub model to deliver much of its rehabilitative programming. We find that the reentry model has several strengths. First, it consolidates certain rehabilitation programming, achieving cost savings through economies of scale. Second, it provides services only to high–risk inmates, which, according to research, provides the greatest benefit. Third, it targets inmates who are nearing release so that programs can assist these individuals with reintegration into society. Finally, these reentry hubs are located near where most inmates are paroled so that families can visit and help inmates reintegrate.

However, the administration’s proposal to expand access to these rehabilitation services in all in–state contract facilities represents a significant deviation from the reentry hub model. This is because, rather than concentrating services, it spreads them across the contract facilities. Also, the plan does not limit the programs to high–need or soon–to–be–released inmates. Providing programming to inmates who do not meet this description is problematic because it does not adhere to evidence–based methods. In addition, many high–risk, soon–to–be–released inmates in other CDCR facilities would continue to lack access to these services. Furthermore, the administration’s plan would provide 334 annual programming spaces at each of the in–state contract facilities, irrespective of the number of inmates at each facility that require services. This is problematic because the number of inmates at each facility can vary widely. For example, Lassen houses only 125 inmates, but would be provided 334 programming slots. Thus, virtually every inmate at Lassen would have to participate in two to three programs annually for all the slots to be filled. Conversely, California City Correctional Center houses approximately 2,381 inmates—nearly 30 percent of the in–state contract population. However, under the proposal this facility would also only receive 334 programming slots—about 8 percent of the total amount allocated. Moreover, CDCR has not done an analysis of the number of inmates at each facility that would have an assessed need for these programs. Thus, there may be inmates who could benefit from such programming—particularly high–risk inmates nearing release—who would not be able to access services, while the administration’s plan would provide treatment to inmates without need for such services.

NCRF Proposal Is an Inappropriate Use of Funds and Unlikely to Be Cost–Effective. We have several concerns with the administration’s plan to allocate $8.3 million from the Recidivism Reduction Fund to support the design of NCRF. First, we are concerned that the proposal is an inappropriate use of the Recidivism Reduction Fund. The Legislature created the Recidivism Reduction Fund to support programs designed to reduce recidivism, such as substance abuse treatment and cognitive behavioral therapy. As such, we are concerned that the Governor’s proposed use of these funds to support the design of a new prison is inconsistent with legislative intent, particularly since the department has not provided any information on how NCRF would reduce recidivism. Second, we are concerned about the potential cost of NCRF. As mentioned above, in 2010, the department estimated that the total construction costs would be $115 million and that the facility would cost about $90,000 per inmate to operate—one and a half times the current average cost to house an inmate in state prison. Thus, even if NCRF is operated in a way that would reduce recidivism, its potential cost makes it unlikely to be the most cost–effective approach for doing so.

Community Reentry Proposal Lacks Important Details and May Be Difficult to Implement. We are also concerned that the administration’s plan to allocate $40 million from the Recidivism Reduction Fund to support the development of community reentry facilities lacks several important details. For example, the administration has not indicated how many reentry facilities would be opened or where they would be located. In addition, CDCR has not provided the estimated cost or population per facility, nor has it indicated what specific services would be offered or what the expected reduction in recidivism would be. Without this information the Legislature cannot determine whether the reentry facilities would be a cost–effective approach to reducing recidivism.

We are also concerned that the state may face challenges siting new reentry facilities. The greatest need for reentry services tends to be in densely populated urban areas with a high concentration of reentering inmates. However, it can be difficult to find suitable locations for reentry facilities in such areas because they tend to be more developed, leaving less land available for acquisition. In addition, it can be difficult to find communities that are interested in accommodating correctional facilities. For example, in 2007 the Legislature approved funding to construct 32 reentry facilities. For a variety of reasons, including CDCR’s difficulty finding suitable locations for the facilities, none were actually built. In 2012, the Legislature ultimately withdrew the funding authority for these facilities.

In view of the above, we recommend a variety of modifications to the Governor’s recidivism reduction proposals. In addition, we recommend that the Legislature focus on adopting policies that would help to maintain long–term compliance with the court–ordered population cap. Our recommendations are summarized in Figure 5 and described in more detail below.

Figure 5

Summary of LAO Recommendations

- ✓ Modify Governor’s Recidivism Reduction Proposals

- • Reject funding for Integrated Services for Mentally Ill Parolees program expansion and require evaluation.

- • Approve expansion of drug treatment but require evaluation.

- • Withhold funding for rehabilitation programming in contract facilities.

- • Reject Northern California Reentry Facility proposal.

- • Reject reentry facility proposal.

- • Evaluate current rehabilitative programs.

- ✓ Use Recidivism Reduction Fund to Incentivize Counties to Reduce Prison Admissions

- ✓ Focus on Long–Term Compliance

|

Modify Governor’s Recidivism Reduction Proposals

Reject Funding for ISMIP Expansion and Require Evaluation. We are concerned that the administration’s plan to spend $11.3 million to expand ISMIP from 600 to 900 slots does not take into account the available data on the program’s effects on recidivism. The high cost per participant raises questions both about its cost–effectiveness as currently operated and whether it would be cost–effective even if targeted to parolees with serious mental illnesses. Additionally, the evaluation performed by CDCR is not adjusted for the effects of realignment, which casts further doubt on the cost–effectiveness of the program.

Given these concerns, we recommend that the Legislature reject the administration’s plan to expand the ISMIP program. We also recommend the Legislature use a portion of the funding proposed for the program to contract with independent research experts (such as a university) to evaluate the effectiveness of the existing ISMIP program. Such a study should include information on recidivism reduction effects, the types of crimes avoided, and cost–effectiveness of the program. This would help the Legislature determine whether the existing ISMIP program could be improved. We estimate that such a study could be completed for several hundred thousand dollars.

Approve Drug Treatment Expansion but Require Evaluation. We recommend that the Legislature approve the administration’s proposed expansion of drug treatment services in state prisons. Given the limited evaluation regarding the effectiveness of CDCR’s in–prison drug treatment services, we also recommend that the Legislature use a portion of the proposed funding to contract with independent research experts to evaluate the department’s delivery of such services. This would allow the Legislature to determine whether CDCR’s programs are being implemented consistent with best practices and are cost–effective at reducing recidivism. We estimate that such a study could be completed for several hundred thousand dollars.

Withhold Funding for Rehabilitation Programming in Contract Facilities. While we acknowledge inmates housed in in–state contract facilities have a need for rehabilitation programs, we are concerned that the administration’s plan to expand such programs to these facilities is poorly conceived. This is because the proposal is not consistent with CDCR’s reentry hub model and does not account for each facility’s population or programming needs. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature withhold funding for the proposed expansion and require the department to present a revised proposal at spring budget hearings. The department’s revised proposal should align with the CDCR reentry hub model, target inmates who have a high or moderate risk to reoffend, and be based on the treatment needs of each facility’s population. Should this revised proposal address the issues identified in this brief, we would recommend the Legislature approve funding for the proposal.

Reject NCRF Proposal. We recommend that the Legislature reject the administration’s plan to allocate $8.3 million from the Recidivism Reduction Fund to support the design of NCRF. As discussed above, the proposal is an inappropriate use of the Recidivism Reduction Fund and is unlikely to be a cost–effective approach to reducing recidivism.

Reject Reentry Facility Proposal. We also recommend that the Legislature reject the administration’s plan to allocate $40 million from the Recidivism Reduction Fund to support the development of community reentry facilities. The administration has not provided the Legislature the information it needs to assess whether the proposal is a cost–effective approach to reducing recidivism.

Evaluate Current Rehabilitative Programs. The type of rehabilitative services provided by CDCR—including cognitive behavioral therapy, substance abuse treatment, education, and employment programs—have been found to reduce recidivism in a cost–effective manner if implemented consistent with best practices. Thus, these programs can improve public safety and reduce state and local correctional populations and costs. However, a significant share of the inmate and parolee population will continue to lack access to these programs even after the administration’s proposed expansions. This suggests that the Legislature may want to pursue a further expansion of these programs as a way to assist the state in maintaining compliance in the long run.

However, just as there are questions about CDCR’s implementation of the ISMIP and substance abuse treatment programs, it is unclear whether CDCR’s other inmate and parolee programs are cost–effective and implemented consistent with best practices. In addition, it is unclear whether CDCR has assessed a sufficient number of inmates and parolees to identify the full extent of their rehabilitative needs. Given these information limitations, we recommend the Legislature direct the department to develop a proposal to contract with independent research experts to evaluate the department’s rehabilitative programs—for both inmates and parolees—in addition to the ISMIP and in–prison substance abuse program evaluations. The evaluation should include information on the cost–effectiveness of the programs and the cost and long–term implications of expanding the programs to meet the needs of CDCR offenders. We estimate that such a study could be completed for a few million dollars and could be funded from the Recidivism Reduction Fund. This information would allow the Legislature to assess (1) the cost–effectiveness of the state’s current investment in rehabilitative programming, (2) whether a further expansion is appropriate, and (3) whether other, more effective investments that improve offender outcomes would be more appropriate.

Use Recidivism Reduction Fund to Incentivize Counties to Reduce Prison Admissions

Our above recommendations to reject the administration’s plans related to community reentry facilities, NCRF, and ISMIP would “free up” almost $60 million from the Recidivism Reduction Fund for the Legislature to allocate to other activities it deems to be of higher priority. As discussed above, we recommend using a small portion of these funds for research and evaluation. While the Legislature has many options regarding these monies, in our view the best option would be to use the remaining funds to provide grants to counties to reduce the number of offenders they admit to state prison.

Under our proposed option, the Legislature could expand the program created by Chapter 608, Statutes of 2009 (SB 678, Leno), commonly referred to as SB 678, which provides counties a fiscal incentive to reduce the number of felony probationers that fail on probation and are incarcerated. Specifically, the Legislature could reward counties for successfully preventing offenders under other forms of county community supervision created by realignment from coming to prison. Under the 2011 realignment, realigned felons can receive a split sentence in which they spend the initial portion of their sentence in jail and the remaining portion in the community under “mandatory supervision” of county probation officers. In addition, following their prison sentences, nonserious, non–violent felons are generally placed on Post–Release Community Supervision (PRCS), where they are supervised in the community by county probation officers. If offenders under these types of county supervision commit new prison–eligible felonies, they can be sentenced to state prison. Under our proposed option, funds could be provided to counties as “seed” grants to support the development or expansion of programs for offenders on mandatory supervision and PRCS that have been demonstrated to reduce crime. Counties could then be rewarded with a portion of the savings they create for the state by preventing these offenders from being sent to state prison. Award grant funding would then provide an ongoing funding source for crime reduction programs.

Our recommended approach has several advantages. Because the state would retain a portion of the savings from reduced prison admissions, this approach would result in net state savings. The approach could also have a positive impact on public safety if it caused counties to invest grant funds in ways that improved offender outcomes. The impact on county workload would be minimal because the costs of any potential caseload increases could be offset by state incentive grant funding. In addition, much of the data necessary to administer the grant program is already being collected by counties. We note, however, it could take time for a sufficient amount of data to be available.

There are, however, a couple of trade–offs with this approach. First, the degree to which this approach reduces the prison population is subject to significant uncertainty and could vary significantly depending primarily on (1) the size of the fiscal incentive and (2) whether counties are able to successfully reduce prison admissions. Second, this approach is unlikely to result in a reduction in prison admissions comparable to SB 678, given that the combined mandatory supervision and PRCS population is about one–tenth of the felony probation population. However, in order to achieve a larger impact, the Legislature could consider creating a new grant program that would also reward counties for reducing their prison admission rates both for offenders on misdemeanor probation as well as for individuals not under any form of community supervision. We note, however, that this would pose much greater implementation challenges as it would be necessary to develop the methodology and data required to effectively measure and reward counties’ efforts at reducing prison admissions.

Focus on Long–Term Compliance

Given the immediate deadlines facing the state in the next few months, the administration’s plan to contract for bed space is a reasonable approach to achieve short–term compliance with the court order, and the Legislature has little choice but to approve the funding for the contracts if it wishes to avoid releasing inmates early. However, if the inmate population grows at the rate CDCR projects, the state will be unable to maintain long–term compliance. This is because the plan contains relatively few measures that would help the state maintain long–term compliance other than relying indefinitely on costly contract beds. While using the monies in the Recidivism Reduction Fund as we have proposed would bring the state closer to long–term compliance, these investments alone are unlikely to result in a reduction in the prison population of sufficient magnitude to ensure long–term compliance or substantially reduce the number of contract beds needed to maintain compliance. Thus, the Legislature must take additional steps if it wishes to (1) ensure that the state will not exceed the court–ordered prison population cap in the future and (2) reduce the number of contract beds necessary to maintain compliance with the cap.

To accomplish these goals, we recommend that the Legislature consider the following criteria.

- Public Safety. How will the option affect public safety? Can any negative impacts to public safety be mitigated by the use of evidence–based correctional practices, such as risk assessments, community–based sanctions, or treatment programs?

- Budget Impact. What is the fiscal impact to the state? How certain is the impact?

- Magnitude. To what extent will the option reduce the prison population or increase prison capacity? Are the changes sustainable?

- Ease of Implementation. Does the option require only simple actions (like statutory changes) or something more complicated (like implementing a new program)? Will population reductions be delayed because of implementation requirements?

- Effects on Local Governments. Will the option increase local costs or jail overcrowding? Will the option affect local law enforcement?

In order to assist the Legislature, we provide below some options that we think merit legislative consideration. None of the options are “perfect” solutions, and we recommend that the Legislature review each option with an eye towards identifying those that best meet legislative policy goals and have the least potential negative trade–offs. We also note that many of these policy options would take months or even years to reach their full impact on the prison population. Accordingly, the sooner the Legislature acts, the better. By acting now, the Legislature puts itself in a better position to ensure that the state’s compliance strategy is consistent with its policy priorities. Conversely, the longer the Legislature waits to adopt long–term solutions, the more likely it will find itself once again forced to respond to an imminent court–ordered population limit by extending contracts for prison beds, thereby consuming resources that could be used for other more cost–effective purposes.

Reclassify Certain Felonies and Wobblers as Misdemeanors. One specific option the Legislature could consider is to reclassify certain crimes from felonies and wobblers to misdemeanors. (Wobblers are crimes that current law allows to be prosecuted either as felonies or misdemeanors.) For example, the Legislature could reduce penalties for drug possession offenses to make such crimes misdemeanors. Under current law, possession of most controlled substances (such as cocaine or heroin) is classified as a misdemeanor, a wobbler, or a felony. Under the 2011 realignment of adult offenders, most offenders convicted of felony drug possession are ineligible to be sentenced to state prison and are thus sentenced to local jail or community supervision. However, those with prior convictions for violent, sex, or serious crimes are still eligible for state prison. Accordingly, making these crimes misdemeanors would prevent such offenders from coming to state prison. We estimate that reclassifying these crimes to misdemeanors would reduce the state prison population by a couple thousand inmates on an annual basis. We note that there are other non–violent felonies and wobblers (such as property crimes) that the Legislature could also convert to misdemeanors.

This option has several advantages. First, it could result in state savings of several tens of millions of dollars annually within a few years of implementation due to the ongoing reduction in the prison population. Second, it would, on net, reduce county jail and probation populations and could create significant correctional savings for counties. This is because converting these crimes to misdemeanors would result in shorter jail stays and probation terms for the felony offenders who do not have prior convictions for serious, violent or sex offenses. Finally, changing drug possession offenses to misdemeanors would be relatively simple to implement as it would only require statutory changes.

One potential trade–off is that the sentencing change would reduce the amount of incarceration time for these offenders, and thus place them in the community earlier. This is because the maximum jail sentence for a misdemeanor is one year, which is typically less than the time these offenders would serve in prison or jail if they were sentenced as felons. This could have a negative impact on public safety because it would increase the amount of time these offenders are in the community and able to commit crimes. We note, however, that there is little evidence that the length of time someone serves in prison affects his or her recidivism rate.

Reduce Sentences for Certain Crimes. The Legislature could also consider reducing sentences for certain crimes. For most felonies, current law provides criminal court judges with a choice of three prison terms, commonly known as a sentencing triad. Judges choose which of these sentences is most appropriate given the circumstances of the crime and offender’s criminal history. For example, first–degree burglary is punishable by two, four, or six years in prison. In addition, current law provides for a number of sentence enhancements—additional time that can be added to an offender’s sentence—based on factors such as prior offenses or possession of a weapon during the commission of the crime. The Legislature could choose to reduce the triad sentences for certain crimes, or it could reduce or eliminate particular sentence enhancements. The effect of such changes to sentencing law would depend on the specific statutory changes made, but could result in a significant and ongoing reduction to the state prison population and correctional costs. This option could also result in a reduction to county caseloads and costs as it would likely affect felons who serve their sentences under county jurisdiction due to the 2011 realignment. While this option would be relatively simple to implement, it would likely take at least a couple of years before it significantly reduced the prison population. One major trade–off with this option is that the affected offenders would spend less time in custody and thus could commit crimes that they could not commit if they remained incarcerated.

Increase the Early Release Credits Inmates Can Earn. Most inmates are eligible to earn credits towards reducing time off of their sentence, such as by participating in prison work assignments or rehabilitation programs. In addition, most inmates earn “day–for–day” credits—one day off their sentence for each day that they refrain from disciplinary problems. However, certain inmates are either ineligible to receive certain credits or have limits on the amount of credit they can earn. For example, as mentioned earlier, second strikers can only receive credits sufficient to reduce their sentence by 20 percent under current law. While the administration’s plan would increase the amount of credits second strikers earn, the Legislature could further expand the amount of credits available to inmates. For example, the Legislature could increase the cap on the amount of credits other inmates can earn or it could further expand the number of inmates eligible to receive credits. The Legislature could also increase participation in rehabilitation programs by expanding the amount of credits inmates earn for participating in these programs.

The magnitude of the prison population reduction that could be achieved from increasing credits would depend on the number of inmates affected and the extent to which their sentences were reduced. While this option would create an ongoing reduction in the prison population and state correctional costs, it would likely take at least a couple of years to achieve. In addition, this option could require resources for CDCR to implement because the department would have to make further changes to the way it calculates sentencing credits, which is already a difficult task. Similar to the above option of reducing sentences, a trade–off associated with this option is that the affected offenders would spend less time in custody and thus could commit crimes that they could not commit if they remained incarcerated. However, to the extent that this option increases participation in programs that make inmates less likely to reoffend, some of the potential negative impacts on public safety from releasing inmates early would be mitigated.

Expand Alternative Custody Program to Male Inmates. As mentioned above, CDCR currently operates an alternative custody program that allows female inmates who meet certain criteria to serve part of their sentence in the community rather than in state prison. Participants may be housed in a private residence, a transitional care facility, or a residential treatment program. The Legislature could consider expanding eligibility for this program to certain male inmates. The reduction in the state prison population and state costs resulting from this option would depend on (1) how many male inmates were eligible to participate in the program, (2) what portion of the participants’ sentences were served outside of prison, and (3) whether the state subsidized the housing costs of participants. To the extent that the state cost for the program was less than the cost of prison, this option would result in net savings to the state.

Similar to the above options of reducing sentences and increasing the credits inmates can earn, a trade–off associated with this option is that the affected offenders would spend less time in custody and thus could commit crimes that they could not commit if they remained incarcerated. However, the Legislature could minimize the effect on public safety by restricting eligibility to inmates who are low risk and by requiring that participants attend programs that make them less likely to reoffend. Another disadvantage of this option is that it could present some implementation challenges as CDCR indicates that the process for reviewing female applicants and placing them into the current program is time consuming and difficult. In addition, to the extent the program further reduced the number of lower security inmates in the institutions, it could reduce the number of inmates available for the fire camp program and other work assignments that are limited to lower security inmates, which could create operational difficulties for CDCR.

Modify Rehabilitative Programs Based on Evaluation. Depending on the outcome of our recommended evaluation of CDCR’s cognitive behavioral therapy, education, and employment programs, the Legislature could also reduce the size of the prison population by expanding these programs, to the extent they are found to be cost–effective. Alternatively, if CDCR’s current programs are not found to be cost–effective, the Legislature could reduce the prison population either by directing CDCR to modify its delivery of the current programs to match best practices or by investing in other programs that have been shown to be cost–effective.

This approach could improve public safety and reduce state and local correctional costs. However, the extent to which this option would reduce the prison population and yield these potential benefits is subject to significant uncertainty. In addition, there could be significant implementation challenges. For example, CDCR would need to hire additional education and vocational instructors and identify contractors to provide community and in–prison rehabilitation programming. This would require a significant up–front investment of resources and could delay any eventual reduction in the prison population. Given these limitations, it is difficult to assess what long–term effect such changes in inmate and parolee programs might have on the prison population, or what the cost of such an expansion might be.