The state, federal, and local governments operate many HHS programs that provide assistance intended to meet a variety of needs, mainly to low–income Californians. Many individuals qualify for two or more of these programs. For example, more than one million Californians are enrolled at the same time in Medi–Cal, which provides health services; CalFresh, which provides food assistance; and CalWORKs, which provides cash assistance and welfare–to–work services to families with children. Because many HHS programs serve overlapping populations, it makes sense to integrate the programs’ eligibility and enrollment processes in order to avoid duplicative processes and streamline the enrollment process from the beneficiary’s perspective. In the past, the state has taken steps to promote integration among certain key programs, particularly the three mentioned above, while other HHS programs are less integrated, meaning they have not been structured to facilitate sharing information and coordinating administrative processes to the extent that they could be.

The integration of health programs and human services programs is sometimes referred to as horizontal integration, a term we will use throughout this report. The state’s horizontal integration efforts have been affected by implementation of ACA, also known as federal health care reform, primarily by making significant changes to Medi–Cal eligibility and administration. At the same time, however, the ACA has presented opportunities to enhance horizontal integration of HHS programs. Throughout ACA implementation, various stakeholders, including the Legislature, the administration, program beneficiaries, and advocates, have expressed an ongoing commitment to preserving and improving horizontal integration.

In this report, we describe the three key programs—Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs—where the state has focused its horizontal integration efforts over the past several years. We also describe how the implementation of ACA has both challenged and facilitated horizontal integration efforts, and we give a status report on where horizontal integration now stands. Given the potential substantial benefits of horizontal integration in terms of both improved government efficiency and improved beneficiary experience, we outline key concepts for the Legislature to consider as it formulates long–term horizontal integration policy and describe steps the Legislature can take to move forward in the short term.

What Is Integration?

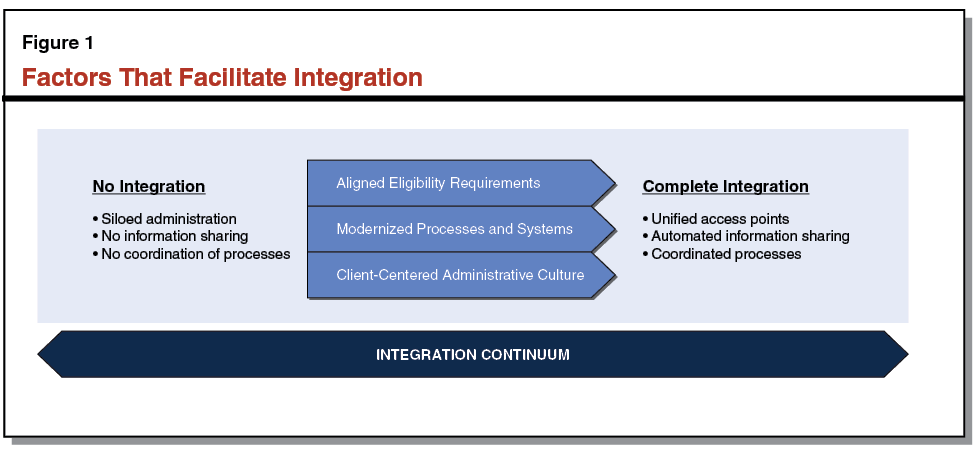

Integration is a way of structuring programs that facilitates information sharing and coordinated administrative processes among programs with the goal of simplifying government administration and improving the access of clients (individuals who receive services through HHS programs) to services. In general, integration can exist among HHS programs to varying degrees and may be understood in terms of a continuum. At one end of the continuum, HHS programs are fully “siloed” and there is no information sharing or coordination of processes among programs, while at the opposite end of the continuum, there is seamless interaction of programs.

What Would Complete Integration Look Like? Completely integrated HHS programs would allow applicants to learn about, and apply for, a broad range of programs through unified access points. One of these access points could be a single online portal that would screen for eligibility and take applications for all HHS programs. For applicants seeking in–person help at county human services offices, (where many HHS programs are administered) staff would be available to connect applicants to the programs that address all of their needs (such as nutritional assistance or prenatal care). Additionally, information shared with one program either online or in–person would automatically be shared with other relevant programs as needed, while taking steps to preserve confidentiality of personal information. For example, once residency information was verified by one program, it would not need to be verified by subsequent programs. This would simplify the enrollment experience for applicants and reduce administrative burdens for the state and local administrators, which would no longer need to duplicate enrollment and eligibility processes. After enrollment, ongoing eligibility would be automatically checked from time to time using existing electronic information, reducing or eliminating the need for program clients to provide additional verification to continue to receive program services. Finally, complete integration need not be limited to HHS programs. It could extend to other government service providers with which program clients interact, such as schools and the courts.

Factors That Facilitate Integration

Below, we discuss several factors that affect where HHS programs are along the integration continuum, as illustrated in Figure 1. It is important to note that these factors interrelate and are not mutually exclusive.

Aligned Program Eligibility Requirements Allow for Cleaner Overlap and Simpler Integration of Eligibility Determinations. Programs can more easily streamline their collective application and administrative processes when their eligibility requirements align. For example, if Program A serves individuals with income at or below 110 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), while Program B serves individuals with income at or below 115 percent of the FPL—but otherwise the two programs have identical eligibility requirements—the programs largely serve overlapping populations. Serving overlapping populations allows program administrators to more easily identify when an individual may be eligible for multiple programs and could more easily connect individuals to programs for which they may be eligible. In these cases, the programs may more easily share application and eligibility determination processes, resulting in a less burdensome experience for program administrators, applicants, and clients. In contrast, the more distinct eligibility requirements are among programs, the more likely that documentation and application processes differ, which complicates cross–enrollment for program administrators, applicants, and clients. In this case, programs may be more likely to operate in silos.

Modernized Processes and Systems Facilitate Information Sharing and Reduce Administrative Burdens. Modernized administrative processes and automation systems make it possible for programs to share information with one another efficiently and accurately, while also helping to reduce duplicate work for program administrators, applicants, and clients. Modernized administrative processes—such as allowing for electronic verification of eligibility information—streamline operations, enhance access, and facilitate integration. The automation systems that support HHS programs perform many of the same basic functions, such as accepting applications, determining program eligibility, tracking application statuses, managing cases, and renewing benefits. When automation systems are linked, application information can more easily be shared electronically for these purposes. For example, information collected and verified by one program to determine eligibility—such as household income—could be shared and used for eligibility determination for other programs. Modifications to automation systems that enhance integration can include (1) “front–end” improvements that simplify the application process and facilitate access to programs for individuals and families and (2) “back–end” improvements that make the eligibility determination process more efficient for program administrators. In some cases, modernized systems and processes can also compensate for unaligned program eligibility requirements by using shared information to sort out eligibility for multiple programs automatically, limiting the need for additional information or time from caseworkers and applicants.

Client–Centered Administrative Culture Facilitates Integration of Multiple Programs. In conjunction with modernized processes and systems, the administrative culture (or the general philosophical approach to administering HHS programs) found in state agencies and in county human services departments can directly affect the extent of integration of programs. Administrative culture that is client–centered will tend to approach administration of HHS programs from the perspective of meeting the multiple needs of program applicants and clients. Rather than focusing on whether applicants and clients are eligible for only the particular programs for which they expressed interest, a client–centered administrative culture will connect applicants and clients to all programs for which they may be eligible. Administering programs with a client–centered focus will generally result in greater integration of HHS programs, and may lead to the modernization of automation processes and systems. On the other hand, program–centered administration will generally result in decreased integration, even in the presence of modernized processes and systems.

The Potential for Integration: Benefits and Costs

Benefits of Integration. Streamlining and better integrating HHS programs can be beneficial in two main ways. First, better integrating programs through simplified and aligned eligibility and enrollment processes may result in decreased administrative burdens for counties (as program administrators) and for clients. For counties, decreased workload could result in additional time being made available for county workers to more adequately assess and address client needs or potentially in budgetary savings for the state and counties. (Budgetary savings would depend on whether county administrative funding is reduced, after accounting for overall county workload and the funding provided therefore.) Integration can also reduce administrative challenges and create efficiencies for program applicants and clients, who may no longer be required to provide the same information to multiple programs. Second, better integrating HHS programs may increase clients’ ability to achieve greater economic stability and self–sufficiency. The HHS programs are structured in such a way that they are fragmented, with each generally serving a relatively specific subset of needs, such as health, nutrition, or job training. Increasing the extent to which individuals with multiple needs can access the full range of programs for which they are eligible could provide greater stability to these individuals and households.

Cost of Integration. The state must allocate resources to implement the administrative process changes and build the automation systems that strengthen integration of HHS programs. The processes and systems involved with administering HHS programs are complex. Making these changes can be costly and subject to risks of delay.

Other Fiscal Impacts on State and Counties. Streamlining and better integrating HHS programs would also have other fiscal impacts on the state and counties. Focusing on connecting clients to all services for which they may be eligible would likely result in higher enrollment, at least in the short run, as individuals participate at higher rates in programs for which they are eligible. Increased enrollment in an uncapped, primarily federally funded program (such as CalFresh), would have relatively little state (General Fund) or county fiscal impacts. However, the state and county impacts of increased enrollment in programs where the state and/or counties and the federal government have their respective cost share (such as Medi–Cal), or in programs where the state receives fixed federal block grant funding (such as CalWORKs), would be much greater, potentially putting pressure on limited state and county resources that fund other legislative or local priorities.

Legislative Interest in Integration

The Legislature has already expressed its interest in strengthening the integration of HHS programs by approving key pieces of legislation and budget proposals. As will be described in greater detail later in this report, some legislation required specific changes to program administrative processes or the related automation systems so that information can more easily flow back and forth across programs, while other legislation called for the formation of workgroups that would be charged with identifying additional opportunities for strengthening integration. Additionally, the Legislature approved budget proposals that allocated resources tasked with further advancing integration and supported improvements to automation systems. The following sections will describe what integration of HHS programs looked like prior to the ACA, how the ACA affected the state’s pre–existing level of integration, and how the state has responded to changes related to the ACA.

The Pre–ACA State of Integration

As noted above, while the ACA has put increased focus on the issue of horizontal integration, integration was a feature of HHS programs in California prior to the ACA. Below, we provide a description of this pre–existing integration, focusing on Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs.

Key Programs Serving Overlapping Populations Offer Opportunities for Integration

HHS Programs Address a Variety of Needs. As noted above, the state and federal governments operate several HHS programs that provide assistance intended to help meet various needs of vulnerable Californians, primarily those with low income. The needs that these programs seek to address include lack of access to medical care, poor nutrition, insufficient income to obtain basic necessities, and unemployment or underemployment. Among HHS programs, three programs—Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs—are characterized by (1) the large number of overlapping clients they serve; (2) their focus on providing means–tested assistance that is intended, at least in part, to help low–income individuals achieve greater economic stability; and (3) local administration by county human services departments. As a result of these common features, the majority of the state’s past focus on HHS–related integration has been on these programs, which we will refer to as “key” HHS programs throughout the remainder of the report. The box below provides background information on the three programs.

Description of Key Health and Human Services (HHS) Programs

In the past, the state’s efforts to integrate HHS programs has focused on the following three programs.

Medi–Cal. In California, the joint federal–state Medicaid Program is administered by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) as Medi–Cal. Medi–Cal is by far the largest state–administered health services program in terms of annual caseload and expenditures. As a joint federal–state program, federal funds are available to the state for the provision of health care services for most low–income persons. In 2013–14, total Medi–Cal costs were estimated to be $62.3 billion—$39.5 billion federal funds, $16.6 billion General Fund, and $6.2 billion other nonfederal funds (including county funds, provider taxes, and fees). Until recently, Medi–Cal eligibility was mainly restricted to low–income families with children, seniors, persons with disabilities, and pregnant women. California generally receives a 50 percent federal share of costs for these populations—meaning the federal government pays one–half of Medi–Cal costs for these populations. As part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), beginning January 1, 2014, the state expanded Medi–Cal eligibility to include additional low–income populations—primarily childless adults who did not previously qualify for the program. The federal government will pay 100 percent of the costs of providing health care services to this newly eligible Medi–Cal population from 2014 through 2016, with the federal cost share phasing down to 90 percent in 2020 and thereafter. In 2013–14, which includes the first six months of ACA implementation, DHCS estimates an average of 9.4 million individuals (roughly 25 percent of the state’s population) received Medi–Cal coverage each month. The DHCS expects Medi–Cal to provide health coverage to about 11.5 million individuals (roughly 30 percent of the state’s population) in 2014–15. Although overseen at the state level by DHCS, Medi–Cal is administered locally by county human services departments.

CalFresh. The CalFresh program is California’s version of the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides food assistance to qualifying low–income households. It is overseen at the state level by the Department of Social Services (DSS) and administered locally by county human services departments. During 2013–14, an average of 4.3 million individuals (roughly 11 percent of the state’s population) received CalFresh assistance each month. The cost of food benefits in the CalFresh program, which totaled $7.6 billion in 2013–14, is paid almost entirely by the federal government. (A small share of total benefit costs—less than one percent—is paid for from the General Fund for certain legal noncitizens who are ineligible for federal benefits.) Costs to administer the CalFresh program are shared among the federal government, the state, and counties. Total budgeted administrative costs in 2013–14 were $1.9 billion ($957 million federal funds, $662 million General Fund, and $280 million county funds). Despite significant recent increases in the CalFresh caseload, many households in California that are eligible for CalFresh assistance do not participate. The United States Department of Agriculture, which administers SNAP at the federal level, estimates that in federal fiscal year 2011, only 57 percent of eligible Californians received CalFresh assistance. The low CalFresh participation rate has been a source of concern for the Legislature in recent years, resulting in numerous policy changes intended to increase participation among those who qualify, some of which have yet to be fully implemented.

CalWORKs. The California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program is California’s version of the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, which provides cash assistance and welfare–to–work services for families with children whose income is inadequate to meet their basic needs. It is overseen at the state level by DSS and administered locally by county human services departments. During 2013–14, an average of about 1.3 million individuals (roughly 3 percent of the state’s population), mostly children, received assistance through the CalWORKs program each month. The CalWORKs program is funded by a combination of the state’s annual federal TANF block grant allocation (fixed at $3.7 billion each year), the state General Fund, and county funds. In 2013–14, total CalWORKs costs were estimated to be almost $5.4 billion—$2.7 billion TANF, $1.1 billion General Fund, and $1.6 billion county funds (including roughly $1.5 billion provided through state–local realignment that directly offset state General Fund costs). Since the state’s annual TANF block grant—the federal funding source for CalWORKs—is fixed and fully allocated in the state budget, incremental costs and savings that occur because of higher or lower caseloads or state policy changes generally accrue to the General Fund. This differentiates CalWORKs from the CalFresh and Medi–Cal programs, in which a fixed percentage share of costs is funded by the federal government.

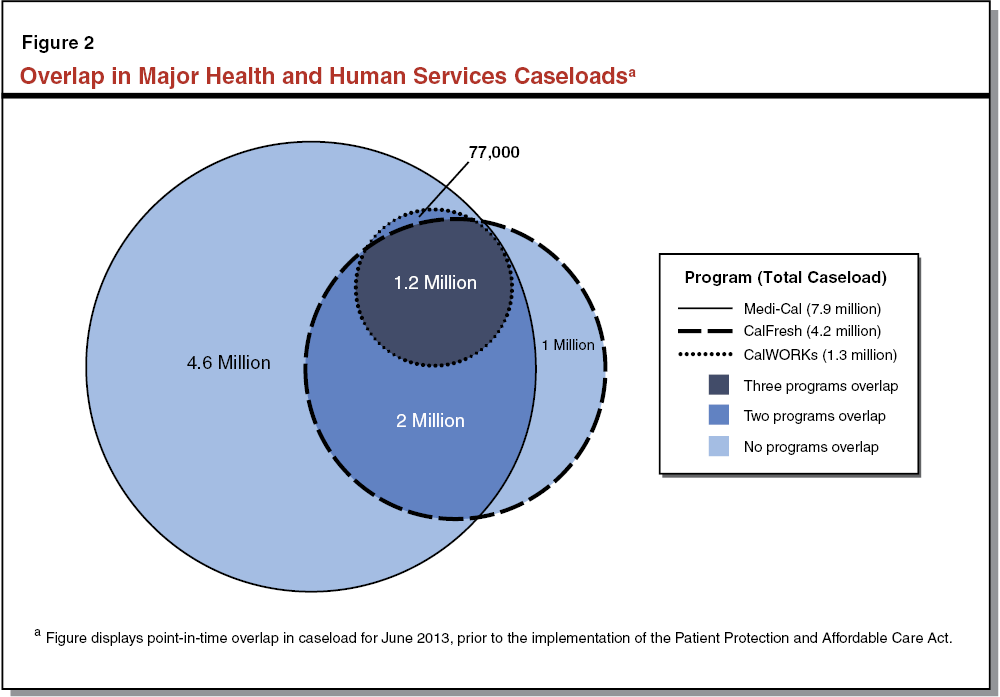

Key HHS Programs Serve Overlapping Populations. The three key HHS programs serve similar populations that overlap. Figure 2 displays the overlap in Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs caseloads in June 2013, prior to the implementation of the ACA. As shown in the figure, at that point in time roughly 1.2 million individuals were enrolled in all three key HHS programs. These individuals represent 92 percent of the CalWORKs caseload, 28 percent of the CalFresh caseload, and 15 percent of the Medi–Cal caseload at that time. This is consistent with CalWORKs having more restrictive eligibility requirements than the other two programs, such that CalWORKs recipients are generally automatically eligible for the other two programs. Additionally, roughly 3.2 million CalFresh clients (including 1.2 million who also received CalWORKs assistance and 2 million who did not) were also enrolled in Medi–Cal, which represents 76 percent of total CalFresh clients and 40 percent of total Medi–Cal clients. As can be seen in the figure, many families have multiple needs and are served by multiple programs. This overlap is one motivation for the state’s previous efforts to integrate eligibility and enrollment processes across the key HHS programs, and for future actions that might be taken to strengthen that integration.

Administrative Processes Partially Supported Integration

Prior to the implementation of the ACA, certain state decisions, described below, led to some integration of administrative processes for Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs. At the same time, differences in county processes and administrative culture resulted in some variation in the level of integration across the state.

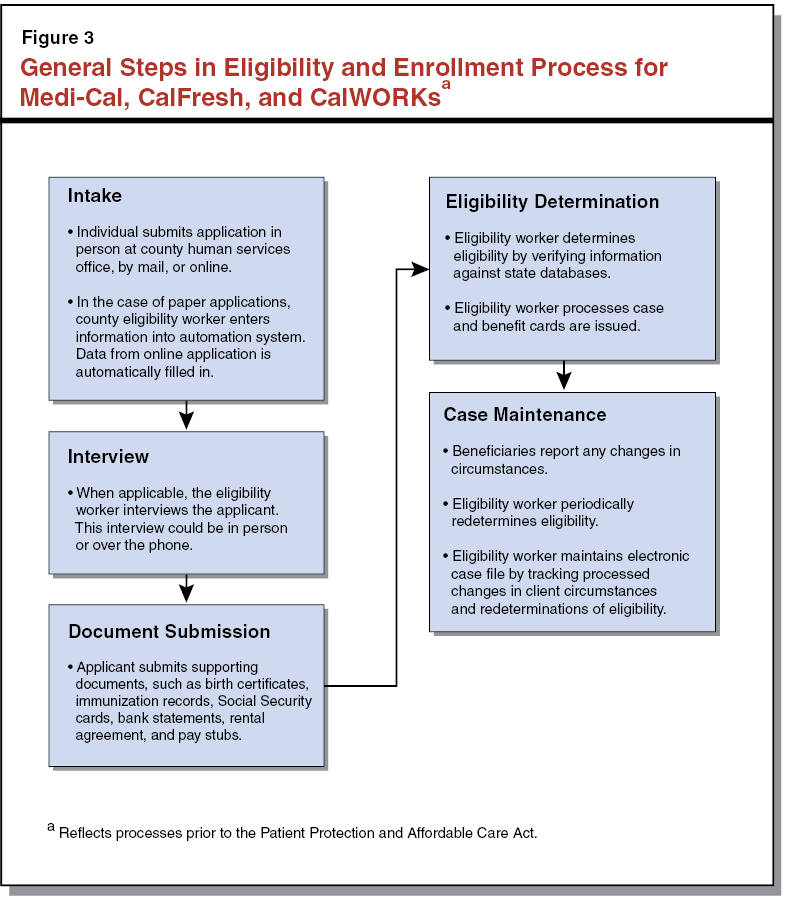

General Steps in Eligibility and Enrollment Process Common Across Key Programs. Prior to January 2014, when the ACA became effective, the basic process of determining eligibility was substantially similar for Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs. Having the same general steps in eligibility and enrollment processes for the three key programs made them conducive to integration. However, similar processes do not guarantee complete integration. Figure 3 shows a high–level view of the main steps in this general eligibility and enrollment process.

State Took Action Prior to ACA Implementation to Promote Process Integration. The state and counties also took steps to integrate some more technical aspects of the eligibility and enrollment processes of Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs prior to the ACA. As an example, the amount of resources a household could have and still qualify for CalFresh and CalWORKs was aligned. Similarly, whenever possible, the points in time during a year at which eligibility was predetermined were generally aligned for clients enrolled in both the CalFresh and CalWORKs programs when the same individuals in the household participated in both programs. This allowed the reporting of identical eligibility information to take place only once for each period of enrollment, reducing reporting burdens for clients and county administrators. For individuals applying for CalWORKs or for more than one of the other key HHS programs, the state also required counties to use a multi–program application that captured all the information necessary to apply for all three programs. The multi–program application allowed counties to process applications for all three programs simultaneously, without having to gather redundant information for each program individually. Although we have described these policies and practices as existing prior to the ACA, they continue today.

County Practices Reflected Local Adaptation and Thus Varying Levels of Integration. Broadly speaking, county administrative practices prior to implementation of the ACA followed the general flow shown in Figure 3. However, the specific county processes varied somewhat, reflecting local circumstances, resources, and preferences. For example, some counties had specialized eligibility staff that processed applications only for specific HHS programs, while other counties had staff that were trained to process applications for multiple programs. Counties also had significant discretion over practices that could lead to applicants being made aware of other programs and services for which they may have been eligible. One county we spoke with while preparing this report noted that its eligibility workers were specifically trained to examine the needs of applicants holistically. Such workers offered all programs for which the applicant was potentially eligible, even if the applicant was not aware of these programs or did not initially intend to apply. Since counties had discretion in the detailed implementation of administrative processes and worker training, the extent to which HHS programs might have been considered integrated varied among counties. Counties continue to have discretion over their administrative processes today.

Automation Systems Partially Supported Integration

While the state’s HHS automation systems were partially integrated prior to the ACA, some aspects of the automation landscape complicated integration. Two automation systems primarily have supported the enrollment, eligibility determination, and case management functions for the key HHS programs: the Statewide Automated Welfare System (SAWS), which consists of three county–run systems known as consortia, and the Medi–Cal Eligibility and Data System (MEDS), which is a statewide is a statewide database that consolidates utilization and benefits data. (The box below describes the systems and provides a history of the SAWS consortia.) In terms of supporting integration, the consolidation of eligibility, enrollment, and case management functions for Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs within SAWS meant that many eligibility and enrollment processes could be coordinated and information could be utilized across the programs with relative ease. The three consortia that comprise SAWS each offered an online portal through which applicants could learn about and apply for Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs. In recent years, these online portals have become increasingly important as a means for clients to apply for services. On the other hand, having multiple SAWS consortia, each providing the same basic functions, leads both to redundancy and variation in how these functions are carried out in different parts of the state. Having multiple SAWS consortia is one reason that other systems, such as the state–run MEDS, are needed to bridge between the systems and provide a centralized repository of statewide client information. In the past, efforts to develop a single SAWS that supports eligibility and enrollment for HHS programs have been stymied by technical, programmatic, and administrative challenges.

Key Automation Systems Supporting Health and Human Services (HHS) Programs

Various automation systems have supported and currently support the state’s HHS programs. The following section describes the two key systems.

Statewide Automated Welfare System (SAWS). The SAWS is made up of multiple systems that support eligibility and benefit determination, enrollment, and case management, among other functions, at the county level for some of the state’s HHS programs, including Medi–Cal, California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs), and CalFresh. The systems perform similar functions, but each system serves a distinct group of counties and is known as one of the SAWS “consortia.” The three consortia systems that currently make up SAWS are Consortium–IV (C–IV), CalWORKs Information Network (CalWIN), and Los Angeles Eligibility, Automated Determination, Evaluation, and Reporting (LEADER) System. The SAWS consortia have been a sizable financial commitment for the state, taking multiple years and hundreds of millions of state and federal dollars to develop and maintain. Efforts are underway to consolidate the total number of SAWS consortia. The LEADER System will be updated in a project known as the LEADER Replacement System (LRS) project. When complete, C–IV counties will be transferred, or migrated, into LRS. At that point, LRS and CalWIN will be the remaining two consortia systems.

Medi–Cal Eligibility Data System (MEDS). Unlike the SAWS consortia, which are county–administered systems that determine eligibility, process enrollment, and manage client cases, MEDS is a statewide database that consolidates information—including utilization and benefits data—on individuals who have applied for or are receiving public benefits from various programs administered by the Department of Health Care Services and the Department of Social Services—including the three key HHS programs that are the focus of this report. (Data maintained in MEDS originates from California’s 58 counties, state and federal agencies, and health plans.) The data found in MEDS is accessed by each of the SAWS consortia (through an interface) to check program applicants’ benefit history. In an environment where eligibility is determined in a decentralized manner—through county–based eligibility systems—MEDS allows counties to check utilization data and prevent duplication in the provision of services to an individual (for example, when an individual applies for the same program in multiple counties). The MEDS is over 30 years old and relies on old technology that is difficult and time–consuming to modify. The state is engaged in preliminary efforts to modernize MEDS, but there is currently no timeline set for the completion of this modernization project.

Other Systems. Various other automation systems also support HHS programs. Some of these programs include:

- The income and Eligibility Verification System, which verifies whether the income information that applicants provide during enrollment intake matches the income information contained in other databases.

- The Electronic Benefit Transfer System, which provides an automated system for the electronic payment of various types of public assistance benefits.

- The Statewide Fingerprint Imaging System, which detects fraud in certain HHS programs by matching the fingerprints of program applicants against a database containing fingerprints of persons who are already receiving aid.

- The Case Management Information and Payrolling System II, which performs payroll and case management functions for all In–Home Supportive Services providers and recipients.

- The Child Welfare Services/Case Management System, which manages child welfare services cases.

History of the Statewide Automated Welfare System (SAWS) Consortia

In 1995, the Legislature approved the development of four automation systems that would serve groups of counties—known as consortia—after the state had unsuccessfully attempted for several years to design and build a single statewide system. In 2006 legislation, the Legislature expressed its preference to reduce the number of consortia. Over the years, the Legislature has consolidated the total number of SAWS consortia, reducing the state’s financial burden of maintaining multiple systems and also assisting in standardizing the eligibility determination processes of the state’s health and human services operations.

Chapter 7, Statutes of 2009–10 Fourth Extraordinary Session (ABX4 7, Evans), directed the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) and the Department of Social Services (DSS) to implement a statewide enrollment determination process for many of the programs administered by the SAWS consortia. The goals of Chapter 7 included (1) using state–of–the–art technology to improve the efficiency of eligibility determination processes and (2) minimizing the overall number of technology systems performing the eligibility process. The statute required DHCS and DSS to develop a comprehensive plan, including an evaluation of the costs and benefits of building a single statewide system, to streamline the eligibility determination process. To ensure the Legislature was kept informed of the plan, Chapter 7 required that the administration submit a strategic plan prior to a request for an appropriation to begin work on a new system related to eligibility determination process changes.

While the administration did take initial steps to implement Chapter 7, a plan was never submitted to the Legislature for its review. Ultimately, the administration suspended planning when the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted in 2010 (with implementation beginning largely in January 2014). In large part, this was due to the fact that the ACA created significant changes to eligibility and enrollment processes for Medi–Cal and therefore impacted the automation system that supports it. Additionally, ACA created health benefit exchanges that need to interact with SAWS for information and data exchange. Anticipating that program changes related to the ACA would necessitate significant changes to the SAWS, the administration paused in planning for a new system.

In 2011, the Legislature enacted Chapter 13, Statutes of 2011–12 First Extraordinary Session (ABX1 16, Blumenfield), which stated the Legislature’s policy to decrease the number of SAWS to two, rather than to a single statewide system. Additionally, this legislation specifies that the reduction will occur by migrating, or moving, 39 counties from the existing Consortium—IV system to Los Angeles County’s new modernized replacement system, currently under development. This effort is expected to be completed in 2019.

The implementation of the ACA created significant changes to eligibility and enrollment processes for Medi–Cal that have in some ways complicated horizontal integration efforts. At the same time, the ACA has presented opportunities to enhance horizontal integration of HHS programs. In the following sections, we provide background on the ACA and describe the ways that the ACA both complicates and provides opportunities to strengthen integration.

The ACA Fundamentally Alters Health Care Coverage

The ACA is resulting in significant changes to health care coverage in California. A primary goal of the ACA is to reduce the number of uninsured by expanding access to affordable health insurance coverage. The ACA seeks to accomplish this goal in several ways, as described below.

Establishes New Requirements for Private Health Insurers and Individuals. Among other things, beginning in January 2014, the ACA prohibits private health insurers from denying coverage to any applicant, including high–risk individuals with pre–existing conditions for whom providing health care is generally more expensive. To compensate for this cost, the ACA also requires most U.S. citizens and legal residents, including low–risk individuals for whom providing health care is relatively inexpensive, to obtain health coverage or pay a penalty. The inclusion of low–risk individuals in health insurance coverage is an important counterbalance to the cost of including high–risk individuals.

Creates Health Benefit Exchanges, Offers Coverage Subsidies. The ACA further promotes coverage by creating health benefit exchanges through which individuals and small businesses are able to research and obtain health coverage from a continuum of health coverage options. (States had the option to establish their own state–based exchange or the federal government would operate an exchange on their behalf. California opted for a state–based exchange.) Creating this continuum of coverage options has required the modification of Medi–Cal to allow it to be linked with the new health coverage subsidies created by the ACA. Individuals with low income may qualify for coverage through Medi–Cal, while the ACA provides new subsidies that offset the cost of health insurance coverage for individuals with higher incomes (up to 400 percent of FPL). The health benefit exchange that serves California, known as Covered California, brings the coverage options available together into one place and assists clients in selecting coverage.

Expands Coverage Through Medi–Cal and Simplifies Medi–Cal Eligibility Determination Process for Many Applicants. The ACA allows states to expand the role of Medicaid in the coverage continuum by expanding eligibility. Effective January 2014, California expanded Medi–Cal coverage to most adults under age 65 with incomes at or below 138 percent of FPL. In addition to expanding eligibility, the ACA also significantly simplified the Medi–Cal eligibility determination process in several ways. Most significantly, the ACA introduced a new methodology for calculating income for certain households, known as Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI). Under the previous methodology, a household’s income would have to be less than specified thresholds after several deductions and exemptions were applied. Under MAGI, income deductions and exemptions are largely eliminated and income is defined simply in terms of the adjusted gross income used for federal income tax purposes. Also of significance, the limit on assets that a household could have and still qualify was removed for most households. For certain other households, primarily seniors and persons with disabilities, the previous Medi–Cal eligibility determination methodology will continue to apply. For the balance of this report, we will refer to this population as the “non–MAGI” Medi–Cal population.

The ACA Affects Pre–Existing Opportunities for Integration

The implementation of federal health care reform created significant changes to eligibility and enrollment processes for state health programs. This, in turn, required the state to reevaluate the administration of the Medi–Cal Program and make modifications to the state’s automation systems in ways that had significant implications for integration, as discussed below.

Linking Medi–Cal to Covered California Required Reevaluation of Medi–Cal Administration

State Considered Options for Medi–Cal Administration in Light of ACA. Prior to the ACA, counties were responsible for reviewing applications, determining eligibility, and managing cases for Medi–Cal clients using the three SAWS consortia. Implementation of federal health care reform required new automation functions not available in the SAWS consortia. Specifically, SAWS consortia did not support (1) the new MAGI rules for determining eligibility for the bulk of the Medi–Cal population and (2) functionality to allow clients to select coverage and obtain a health coverage subsidy through Covered California. The state evaluated a few different approaches to obtaining the needed technical functions to implement the ACA within the complex automation landscape that supports existing HHS programs, including the administration of the Medi–Cal Program at the county level. The state considered three alternatives.

- Option 1: Adding ACA Eligibility and Enrollment Functions to SAWS Consortia. Under this option, the state would add functionality for MAGI Medi–Cal and the other functions needed to support Covered California to the SAWS consortia (eligibility determinations and case management for non–MAGI Medi–Cal cases would remain with SAWS). Building this capacity into the existing eligibility systems would support horizontal integration as the administration of Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs would remain with the counties. However, this option would also be duplicative and potentially expensive as automation changes would be required in each of the three consortia systems.

- Option 2: Developing a Centralized Eligibility and Enrollment System for ACA, Linking to Counties for Medi–Cal Processing and Case Management. Under this option, the state would develop a new central automation system to support eligibility determination for both MAGI Medi–Cal and functions related to subsidies available through Covered California, while retaining existing SAWS consortia to support eligibility determinations for non–MAGI Medi–Cal cases and ongoing case management for all Medi–Cal cases. This approach would require relatively limited modifications to existing consortia systems and would preserve ongoing case management of Medi–Cal in the SAWS consortia with the key human services programs.

- Option 3: Developing a Centralized Eligibility and Enrollment System for ACA, Including All Medi–Cal Eligibility Determinations (MAGI and Non–MAGI). Under this option, the state would develop a new central automation system to administer all coverage options available through Covered California, including non–MAGI Medi–Cal. This approach would result in less duplication relative to option 1, but effectively would weaken the connection between Medi–Cal and human services programs delivered at the county level, potentially making it more difficult for individuals and families to receive all the benefits for which they are eligible.

State Elected Option 2. Ultimately, the state chose to move forward with the second option described above—a central automation system for the functions related to Covered California (including subsidized coverage and MAGI Medi–Cal determinations) that leverages existing infrastructure for ongoing case management. The new central automation system—known as the California Health Eligibility, Enrollment, and Retention System (CalHEERS)—is jointly administered by Covered California and the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS). The CalHEERS allows for real–time eligibility determinations both for Medi–Cal under the new MAGI rules and subsidized coverage; health plan certification, recertification, and decertification; reporting and tracking of data for federal, state, and local purposes; and consumer assistance. The CalHEERS is designed to leverage information and automation processes existing in other state systems—including SAWS and other health–related systems—so as to reduce duplication, and was built using flexible technology to allow for future integration. This decision to pursue the second option reflects a balance between the competing objectives of limiting cost and complexity by reducing duplication and maintaining integration of HHS programs by preserving the link between Medi–Cal and human services programs at the county level.

Post–ACA Eligibility and Enrollment Processes for Medi–Cal Now Differ More From Those of Human Services Programs

As noted above, the ACA made significant changes to eligibility and enrollment processes for Medi–Cal. Specifically, MAGI was introduced as a new streamlined methodology for how income is counted and how household composition and size are determined for the majority of Medi–Cal applicants. These changes were made in order to allow Medi–Cal clients to transition seamlessly between Medi–Cal and coverage subsidies as their circumstances change. At the same time, these and certain other changes mean that Medi–Cal eligibility processes now differ to a greater extent from eligibility processes for CalFresh and CalWORKs than they did previously. While the differences make eligibility determinations simpler for Medi–Cal, the ACA generally made no corresponding simplification for human services programs, and the now greater differences in requirements make integration of processes more challenging. Some of these differences are:

- Electronic Data Verification Now Reduces Application Burden for Medi–Cal, but Not for Human Services Programs. Prior to the ACA, individuals applying for Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs were required to provide verification of the information needed to determine eligibility, often in the form of paper documents such as pay stubs or medical bills. Pursuant to the ACA, many pieces of information needed to determine a Medi–Cal applicant’s eligibility are required to be verified electronically by accessing existing state and federal databases, such as information available from the Employment Development Department and the Franchise Tax Board to verify residency. Consumers are only to be asked to provide physical verification of eligibility if reasonably compatible electronic verification is not available. The CalFresh and CalWORKs programs, however, continue to generally require that physical documents be presented for verification of eligibility.

- Recertification Simplified for Medi–Cal Clients, While Human Services Programs Require Clients to Provide Documentation to Recertify. As discussed previously, individuals enrolled in HHS programs must periodically recertify their eligibility to continue to receive assistance. Prior to the ACA, Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs clients were required to provide updated information related to their eligibility and provide documentation related to any changes. Failure to provide this information or required verification generally resulted in discontinued assistance. Pursuant to the ACA, county administrators now are to proactively attempt to verify continued MAGI Medi–Cal eligibility each year using available electronic sources. If electronic sources confirm eligibility, the individual is automatically certified for an additional 12 months of coverage. If electronic sources are insufficient to verify eligibility, the individual is sent a renewal form with known information filled in that requires verification of only those aspects of eligibility that could not be verified electronically. In contrast, individuals receiving assistance through the CalWORKs and CalFresh programs are still generally required to have a recertification interview and provide documentation supporting continued eligibility. Failure to attend a scheduled recertification interview or provide required documentation results in discontinued assistance.

- Household Definition Now Differs More Among Key Programs. Prior to the ACA, household definitions in Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs differed somewhat. In general, CalWORKs and Medi–Cal households consisted of family members residing in the same home, whereas CalFresh households consisted of individuals that live and prepare food together in the same home. Under the MAGI methodology brought about through the ACA, a majority of Medi–Cal households are now defined as an adult filing a federal income tax return (including the adult’s spouse if a joint return is filed) and any dependents claimed on that adult’s tax return. This new definition of households for Medi–Cal purposes is significantly different than the definition of CalWORKs households. Accordingly, while the transition to MAGI eligibility enables integration of Medi–Cal with coverage subsidies, it also increases the differences in household definitions among the key programs.

The ACA Encourages Integration

As described above, some aspects of the ACA challenged the state’s efforts to horizontally integrate HHS programs. However, other aspects of the ACA provided opportunities to pursue further integration, as discussed below.

Sets Standards That Encourage “Interoperability” of HHS Programs. The ACA requires the U.S. Department of HHS, in consultation with other stakeholders, to develop interoperability standards that facilitate enrollment in HHS programs. Interoperability allows for programs to connect and share information (a term we view as generally equivalent to integration). The standards are not mandatory requirements but rather are intended to encourage adoption of modernized automation systems and processes that allow clients to seamlessly access the full range of HHS benefits for which they are eligible. Although compliance is not mandatory, some federal funding for state automation investments is conditional on compliance with interoperability standards. Initially, the U.S. Department of HHS has called for common technology standards that enable efficient and transparent exchange of data between programs and strong privacy and security standards that protect the personal information of applicants and clients.

Provides Enhanced Federal Funding for Automation System Enhancements. The federal government recognized that most states would need to make significant investments in automation systems in order to meet the requirements of ACA and to horizontally integrate HHS programs. To assist states’ implementation of necessary technological changes, in April 2011 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announced the availability of enhanced federal funding for designing, developing, and implementing automation systems for state–based exchanges (which would include determining eligibility for Medicaid using the new MAGI income definition).

To encourage greater integration of state eligibility systems, the federal government also announced the availability of enhanced federal funding for states investing in human services eligibility and enrollment systems that also serve Medi–Cal or other coverage options available through a state exchange. Traditionally, the cost of implementing or upgrading a human services automation system is generally shared by the various programs that use the system. However, under the ACA’s enhanced funding rules, states may implement or modernize eligibility and enrollment systems that serve both human services programs and exchange–related health programs (such as Medi–Cal), and receive 90 percent federal funding for the total costs (as opposed to the traditional 50 percent). This enhanced federal funding is available only for a limited time. States have until December 31, 2015 to incur costs for goods and services furnished for the design, development, and implementation of human services–related eligibility systems. Currently, both CalHEERS and the Los Angeles Eligibility, Automated Determination, Evaluation, and Reporting(LEADER) Replacement System (LRS) automation projects are leveraging this enhanced federal funding. In addition, the expansion of call centers that support the SAWS consortia by processing Medi–Cal applications over the phone are also being funded with enhanced federal funding.

The changes created by the ACA pose risks and offer opportunities for the state’s human services programs and the clients enrolled in them. Given changes resulting from the ACA discussed above, the state took several actions, described below, that in some cases preserved the existing level of integration of HHS programs and in other cases further enhanced the level of integration.

Steps Taken to Adapt to ACA’s Effects on Existing Integration

The state made various decisions regarding the administration of Medi–Cal and the automation systems supporting HHS programs in order to respond to ACA’s effects on the existing level of integration of HHS programs.

Counties Continue to Administer Medi–Cal

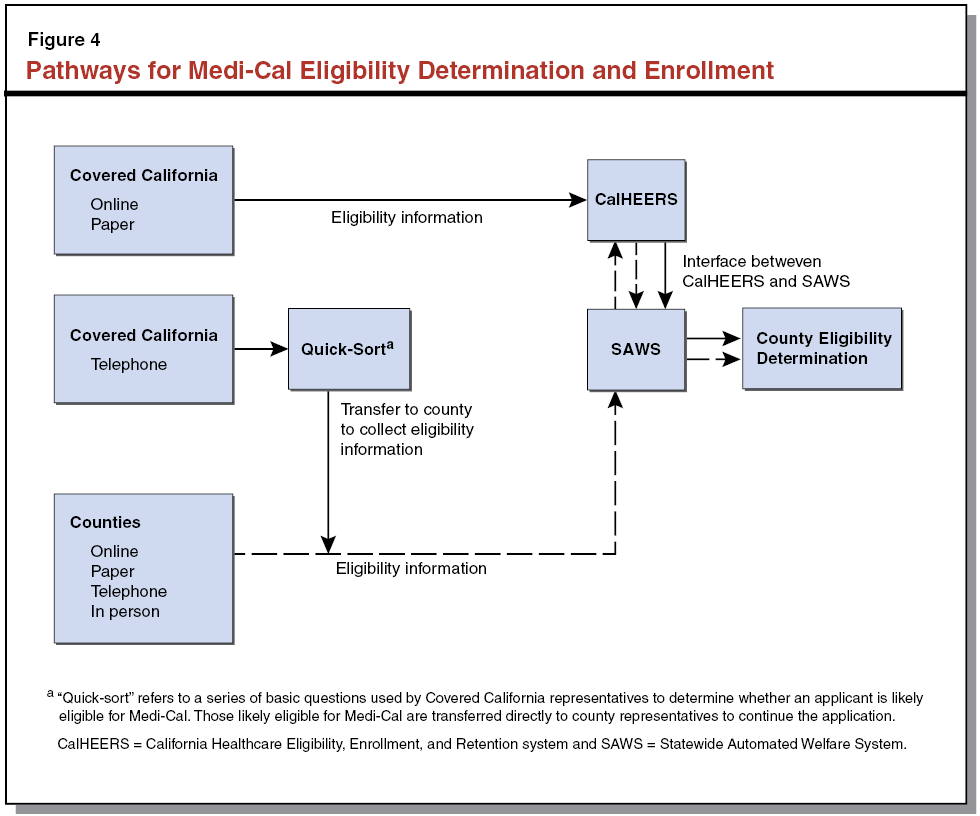

Counties Continue to Approve and Manage All Medi–Cal Cases. As noted previously, the ACA required the state to reevaluate the administration of the Medi–Cal Program. By deciding to build the rules for determining MAGI Medi–Cal eligibility into CalHEERS, the connection between MAGI Medi–Cal and human services programs delivered at the county level could have been weakened. The state chose to preserve the connection between these programs by having counties ultimately perform the eligibility determinations for MAGI Medi–Cal applicants, using the eligibility determination functions built into CalHEERS. (These functions are accessed through an interface between CalHEERS and SAWS, described further later.) This means that counties will be able to largely maintain the processes that link Medi–Cal to key human services programs, as before ACA implementation. As shown in Figure 4, Medi–Cal applications will come to counties in several ways, depending on how a Medi–Cal applicant submits his/her application.

- Paper or Online Application Through Covered California. When applications are submitted to Covered California as paper applications or through the web portal, CalHEERS performs eligibility calculations and sends the results to SAWS through an interface. County workers then complete the eligibility determination and the SAWS becomes the system of record for the case. Counties perform ongoing case management, including answering questions, processing changes in circumstances, and performing administrative redeterminations.

- Telephone Application Through Covered California Call Center. When an applicant calls a Covered California service center, Covered California uses a series of basic questions to determine if the individual is likely eligible for Medi–Cal (a process known as the “quick–sort”). If this is the case, the call is transferred immediately to a county representative who enters eligibility information into SAWS. This information is then sent to CalHEERS where eligibility calculations are performed. The results are sent back to SAWS through the interface, and a county representative completes the eligibility determination for that applicant.

- Paper, Online, Telephone, or In–Person Application Through Counties. Counties may also process applications through the interface between the SAWS and CalHEERS when individuals contact the county directly by phone, online, with a paper application, or in person.

The decision to continue to have counties perform Medi–Cal determinations and ongoing case management is significant for integration because it preserves counties’ ability to assist Medi–Cal clients with additional needs should they qualify for other HHS programs that are also administered by the counties.

Integration With Existing Information Technology Systems

The implementation of the ACA required integration of CalHEERS with multiple federal, state, and county automation systems. In order to integrate, CalHEERS has a system of interfaces, which allow for a back and forth flow of information with other automation systems. Specifically, CalHEERS interfaces with the Federal Data Services Hub, which connects the state with federal data sources—such as those of the Internal Revenue Service, Department of Homeland Security, and the Social Security Administration—to verify income, citizenship, and identity. Implementation of the ACA has also required the linking of CalHEERS with state and county systems. The most significant interfaces are described below.

SAWS Interface With CalHEERS. As a result of the state deciding to move forward with a new centralized system that supports eligibility determinations for MAGI Medi–Cal and Covered California subsidies while retaining existing systems that support non–MAGI Medi–Cal and other HHS programs, the state developed the necessary real–time interface between CalHEERS and SAWS. The SAWS consortia are the systems of record for case management purposes for all cases determined to be eligible for MAGI Medi–Cal as a result of the implementation of the ACA. The interface allows for application and case management information to be shared between CalHEERS and SAWS. The interface therefore allows county workers to process both non–MAGI and MAGI Medi–Cal eligibility determinations as if they are being done with SAWS, even though the MAGI eligibility determination rules are built into CalHEERS.

MEDS Interface With CalHEERS. The CalHEERS interfaces with MEDS for the verification of an applicant’s current enrollment status in state health programs. In addition, CalHEERS interfaces with MEDS to issue identification cards used by clients to access services.

Steps Taken to Enhance Integration

In addition to steps taken to accommodate changes to the existing level of integration brought about through the ACA, the state also took various actions, described below, to go beyond the level of integration that existed prior to the ACA.

Legislature Expressed Commitment to Integration of HHS Programs

As noted previously, the Legislature has expressed a commitment to horizontal integration through various actions. Of note, in 2012 the Legislature passed SB 970 (De León), which would have given individuals who apply for health coverage through Covered California the option of forwarding their application information to county human services offices so as to simultaneously initiate an application for CalWORKs and CalFresh. Additionally, the bill would have required the California Health and Human Services Agency (HHSA) to convene a workgroup to identify additional opportunities for strengthening integration of HHS programs. Ultimately SB 970 was vetoed; however, the Governor stated his intentions to pursue horizontal integration without legislation. As will be described in later sections, the ability to initiate applications for multiple HHS programs in conjunction with a health application is a key feature of more recent state efforts to strengthen integration.

Targeting Existing Human Services Clients for Medi–Cal Enrollment

Of the steps taken by the state to enhance integration of HHS programs, many are focused on more effectively implementing the ACA (by promoting enrollment of eligible individuals into Medi–Cal) in addition to making the administration of HHS programs more effective and efficient. These efforts have primarily centered on strengthening connections between Medi–Cal and CalFresh, the two largest HHS programs and the two programs with the greatest overlap in caseload.

Express Lane Eligibility of CalFresh Clients for Medi–Cal. One way that the state has taken advantage of the opportunities created by the ACA to increase integration of programs is through a federal waiver that allows CalFresh eligibility to serve as a proxy for Medi–Cal eligibility. This process, known as “Express Lane Eligibility,” is intended to expedite the enrollment of individuals into Medi–Cal coverage who are known to qualify for CalFresh without requiring a formal application. Pursuant to Chapter 4, Statutes of 2013–14 First Extraordinary Session (SBX1 1, Hernandez and Steinberg), DHCS obtained the federal waiver and implemented the Express Lane process beginning in early 2014. Under this process, CalFresh clients who have characteristics that indicate they would be eligible for Medi–Cal but are not enrolled in Medi–Cal are sent a notice informing them that they qualify for Medi–Cal coverage and can enroll by returning the notice. Those that return the notices are enrolled in Medi–Cal without having to submit a separate application. As of September 2014, over 200,000 adults and nearly 40,000 children enrolled in Medi–Cal using the Express Lane process. Going forward, DHCS has instructed counties to use the Express Lane process to enroll interested CalFresh clients in Medi–Cal when they initially apply for CalFresh or at their annual recertification. The current waiver that allows Express Lane Eligibility expires at the end of 2015.

Targeting Medi–Cal Clients for Human Services Enrollment

Through ACA implementation, the state has taken action to strengthen integration by facilitating enrollment in human services programs to existing and new enrollees in health coverage made available through the ACA. This integration is being pursued in several ways described below. These efforts are expected to increase the state’s CalFresh participation rate, which, as discussed earlier, is low.

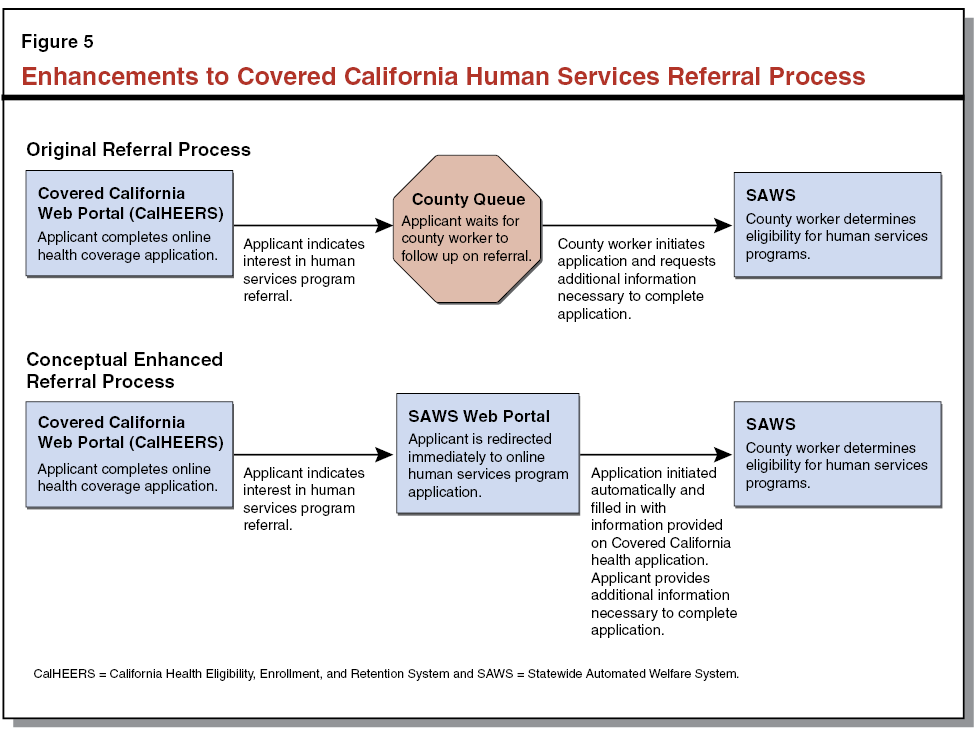

Human Services Referrals From Covered California Health Application. The Covered California application for health coverage (whether on paper or online) has allowed applicants to indicate that they would like the information provided in the application to be shared with county human services departments as a referral for CalFresh and CalWORKs. This referral process places applicants in a queue until a county eligibility worker reaches out to applicants to begin applications for the relevant programs. It is unknown how many individuals have enrolled in CalFresh and CalWORKs as a result of these referrals since the process was put in place. The referral process is a step towards fulfilling the intent of SB 970—by facilitating enrollment in human services programs through a health coverage application. The objective of SB 970 will be more fully realized once the interface between CalHEERS and SAWS is enhanced, as described in the next section.

Enhancements to CalHEERS and SAWS Interface. The 2014–15 Budget Act includes $22.7 million for enhancements to the interface between CalHEERS and SAWS that will incorporate more real–time functionality and screening capabilities that streamline counties’ time processing of applications. Although the design for the enhanced interface is not complete, the funds are intended to provide, among other things, for a more robust referral process that will screen applicants for eligibility and take interested applicants immediately to the SAWS portal where applicants can complete and submit their applications for human services programs, including CalFresh and CalWORKs. Once implemented, the enhanced interface between CalHEERS and SAWS—as illustrated in Figure 5—will expedite the referral process and maximize enrollment of individuals in the programs for which they are eligible. In addition, the funds will automate Express Lane Eligibility for ACA implementation to expedite MAGI Medi–Cal eligibility determinations for CalFresh clients. Automating the Express Lane process will reduce county manual workarounds and assist counties in correctly processing the Medi–Cal portion of the case without data errors.

Additional Changes to Promote CalFresh Awareness Among Medi–Cal Clients. The state has taken additional steps to raise awareness of CalFresh among Medi–Cal applicants and clients by including information about CalFresh in Medi–Cal enrollment documentation. Many counties additionally use existing Medi–Cal enrollment data to determine which Medi–Cal clients are likely to be eligible for CalFresh and then providing information about CalFresh enrollment to these households.

Creation of Executive Office at DSS to Identify Horizontal Integration Opportunities

As part of the 2013–14 Budget Act, the Governor proposed and the Legislature approved the creation of new positions for an Assistant Director for the Office of Horizontal Integration and two additional staff at Department of Social Services (DSS) to facilitate an analysis of the human services program implications of the ACA and to identify options for further integrating HHS programs. Given tight federal time frames related to the state’s establishment of a health benefit exchange, integrating HHS programs was secondary to the task of launching Covered California. However, with the launch of Covered California and the first open enrollment period complete, greater attention can now be given to horizontal integration efforts.

Interoperability Symposia Explored Issues Around Data Sharing

The federal government awarded California (and six other states) a one–year grant as part of the State Systems Interoperability and Integration Project. This project was intended, among other things, to allow selected states to explore and plan for improved data sharing, or interoperability, across HHS automation systems in order to help streamline administrative processes, among other goals. In California, the HHSA’s Office of Systems Integration used the grant to host two symposia in May and September 2013. The symposia brought together state and local representatives to (1) create a common awareness of the value of interoperability; (2) identify barriers to information sharing, specifically to gain an understanding of how current governance, legal, technical, and cultural models could impede interoperability moving forward; and (3) identify a strategy for improving interoperability and integration across HHS programs.

Interoperability Roadmap Outlines Short–, Medium–, and Long–Term Goals. The principal product of the symposia in California was an interoperability plan, or roadmap, with short–, medium–, and long–term objectives to developing interoperable HHS systems:

- Short–term goals (within the first six months) focus on setting a strong foundation for future integration efforts by, among other things, cultivating advocates for interoperability within the stakeholder community and formalizing a governance model at the agency level that would improve coordination and decision–making around efforts to improve interoperability.

- In the medium term (6 to 24 months), the plan calls for staffing of the governance model; developing various policies, procedures, and performance metrics for interoperability; and assessing active projects for interoperability opportunities.

- Beyond two years, the roadmap focuses on implementing strong governance across HHSA and counties, adopting protocols that facilitate information sharing, and monitoring and measuring progress towards a client–centered culture.

Status of Implementation of Interoperability Roadmap. The administration has not put forward a proposal to implement the interoperability roadmap in whole. However, a recent budget action was, broadly speaking, in line with the goals of the interoperability roadmap. Specifically, as part of the 2014–15 Budget Act, the Governor proposed and the Legislature approved new permanent resources within the Office of the Agency Information Officer—an office of the California Health and Human Services Secretary—to establish a formal agency–wide governance and strategic planning program. The resources are intended to help the agency consider ways to promote interoperability as it is developing automation projects.

As discussed above, ACA implementation has resulted in significant changes to health care coverage but also focused attention on integration of HHS programs. During the period between the passage of the ACA and the first open enrollment period for Covered California, emphasis was appropriately placed on systems and processes needed to support Covered California, while broader discussions of potential changes to enhance integration were, to some extent, deferred. At the same time, we find that significant steps have been taken throughout the initial period of ACA implementation that addressed challenges posed by the ACA on the existing level of integration and also strengthened integration. Collectively, the progress made prior to the ACA and the steps taken because of the ACA to preserve and enhance integration have resulted in a moderate level of integration across HHS programs. As discussed below, we find that while some aspects of furthering integration remain challenging, some additional opportunities exist for enhancing integration beyond those steps already taken. However, such opportunities will involve trade–offs and likely require additional high–level coordination and planning to implement.

Federal Law Limits Ability to Align Many Program Eligibility Requirements and Processes

In some HHS programs, such as CalWORKs, the state has significant discretion over certain eligibility requirements, including maximum income thresholds or limits on the amount of resources households may have and still qualify. The Legislature could examine the cost and benefits of using its discretion to better align these requirements with other major HHS programs. For other programs, however, the state has much less flexibility. Despite state efforts to align eligibility requirements and processes for HHS programs that serve overlapping populations, many key differences between programs exist and many of these differences reflect requirements set in federal law. One example is the process for determining income eligibility for CalFresh. Federal law requires that a household’s income be adjusted by various factors (such as housing costs and child care expenses) before determining eligibility. These adjustments generally involve an additional verification, adding complexity to the eligibility determination process that is not reflected in eligibility processes for other programs. The federal government also places limitations on how some eligibility processes may be structured, for example, by limiting the use of certain sources of the electronic verification of income, identity, and other matters. Specifically, federal guidance currently does not allow for electronic verifications provided through the Federal Data Services Hub (which is used to perform electronic verifications for health coverage through Medi–Cal or coverage subsidies) to be used in determining eligibility for any other program. The fact that many program requirements are set through federal law limits the state’s ability to pursue further alignment of eligibility requirements and processes in many instances. Waivers of some federal regulations are possible, but the state has had mixed success in receiving approval for such waivers in the past.

Decentralized Administrative Structure Complicates Efforts to Modernize Systems and Processes

As noted previously, local administration is a defining characteristic of California’s HHS delivery system. Given the size and diversity of the state, local administration makes sense in many contexts. However, local administration also means that efforts to increase integration through modernizing processes and systems must involve many stakeholders in different agencies at multiple levels of government.

County Practices, While Similar, Are Developed and Implemented Independently. While the overarching administrative processes for eligibility determination and case management are similar across counties, varying county practices make it difficult to create uniform administrative practices that serve the needs of all 58 counties. Making further progress towards an integrated HHS environment would require engagement from a broad range of stakeholders at different levels of government. These stakeholders would have to be willing to forego some autonomy in favor of more standardized state–driven processes in order to advance integration.

Multiple Automation Systems Complicate Integration. . . The complex and sometimes duplicative automation landscape that remains in the state even after integration efforts also impedes further horizontal integration. The multiple automation systems that support HHS programs—some operated by the state and others operated locally—make it more challenging for programs to share information seamlessly and efficiently cross–enroll applicants. As noted previously, technical challenges have prevented the state from developing a single statewide eligibility determination system for key HHS programs. However, the migration of Consortium–IV counties into LRS will reduce the number of consortia systems to two and make some progress toward overcoming technological impediments to further integration.

. . . But Planned System Upgrades May Provide Opportunity for Additional Modernization and Enhanced Integration. Several key automation systems are currently undergoing or are likely in the future to undergo major development or enhancement (including LEADER, MEDS, and the Child Welfare Services/Case Management System). Should the Legislature wish to pursue additional integration through automation system modernization, the development of planned upgrades to existing systems would be an ideal time to consider how improvements related to integration could be worked into upgrade plans. One potential example of such an improvement would be restructuring other systems to use a common identity verification function. Currently, multiple HHS automation systems, including MEDS, have the capacity to electronically verify the identity of an applicant. Rather than have duplicate technology in multiple systems, multiple HHS programs could interface to share a common identity verification function. The MEDS modernization project creates an opportunity to build an upgraded system with the flexibility to share the identity verification function with other automation systems.

Time Is Right for Legislature to Indicate Priorities for Integration

Setting Legislative Priorities Could Help Drive Integration Efforts. Given that the first open enrollment period for Covered California has passed and the Covered California automation system infrastructure is in place, now would be an appropriate time for the Legislature to indicate its goals and priorities for integrating HHS programs going forward. The Legislature could elaborate on its previously expressed commitment for integration, assess the extent to which these priorities have or have not been met through ACA implementation, and consider what further action may be appropriate. This report is intended to facilitate the Legislature’s review by describing integration–related changes made through the initial ACA implementation period. However, the significant complexity involved with any planning for further integration will naturally require close collaboration with the administration and with local program administrators as specific next steps are identified.

Interoperability Roadmap Is a Good Starting Point for Legislative Deliberations. In our view, the California Interoperability Symposia were effective at bringing together state and local administrators and other stakeholders to identify and discuss key issues relating to information sharing and integration of HHS programs more broadly. Should the Legislature wish to focus attention on further integration, the goals outlined in the Interoperability Roadmap would provide a useful starting place for legislative deliberations.

Significant steps have been taken through the process of implementing the ACA to both preserve existing integration and also move the state further along the continuum of integration of HHS programs. As we noted, we find that the state has achieved a moderate level of integration. If desired, strengthening the integration of the state’s HHS programs beyond what has already been accomplished will be a long–term initiative that requires legislative direction and engagement. Legislative engagement in setting a common vision for integration that all stakeholders—executive branch state officials, local representatives, and client advocates—can work toward will be critical to the success of any future integration efforts. The following section outlines ways that the Legislature could build on the steps taken to date and craft its vision for integration.

Holding Legislative Hearings on Horizontal Integration Efforts to Date to Inform Legislative Vision

We think a necessary next step is for the Legislature to hold hearings to review current and anticipated integration efforts. Many of the initiatives to advance integration since the passage of the ACA have been administration–led. Legislative hearings would update the Legislature on what has been accomplished and better positon it to craft its vision for the future. Specifically, at such hearings we think it would be important for the Legislature to ask HHSA to do the following:

- Present the California Interoperability Roadmap and provide a status update on its efforts to implement the roadmap.

- Identify legal impediments to data sharing that could stifle integration efforts and corresponding opportunities for the Legislature to remove or mitigate the impact of such impediments.

- Describe administration–led efforts to (1) align eligibility requirements for HHS programs, (2) standardize eligibility and enrollment processes, and (3) centralize or consolidate automation systems.

Issues to Consider When Setting Integration Priorities

We recommend that the Legislature consider the following questions as it holds the hearings described above, develops its vision, and determines what further efforts could be made to strengthen the integration of eligibility and enrollment processes for HHS programs.

What Is the Appropriate Balance Between Local Control and Standardized Statewide Automation Systems and Processes? As noted previously, the administration of HHS programs is complex, involving many stakeholders in different agencies at different levels of government. Some local variation is inherent in current eligibility and enrollment practices. Further efforts to increase integration would likely result in less local autonomy. The Legislature should weigh the benefits of local variation, such as responsiveness to local needs and preferences, against the benefits of increased integration, including administrative efficiencies and improved client access to programs. Completely eliminating all county variation in eligibility and enrollment processes is likely neither feasible nor desirable. In fact, local variation can be a source of innovative practices that merit consideration for implementation statewide. For example, when one of the SAWS consortia built in new functions for clients to more easily monitor benefits online, the other SAWS consortia have recognized the value to clients and added similar functions to their systems. It is important to note that increased standardization and integration of eligibility and enrollment processes does not imply that other forms of local variation would necessarily be affected. For example, counties currently have significant latitude with respect to the structuring of welfare–to–work services in the CalWORKs program. This type of variation is not related to eligibility and enrollment processes (and would therefore not be part of integration efforts).

How Can Automation Systems Currently in Development Be Built to Strengthen Integration? As noted previously, several key HHS–related automation systems are currently undergoing or are likely in the future to undergo major enhancements. The Legislature should consider whether additional resources ought to be devoted to researching and implementing options to promote integration of these systems. In considering these kinds of enhancements, the Legislature would need to weigh the potential benefits of increased integration (in the form of decreased duplication, streamlined access, and data sharing) against likely increases in development costs, longer implementation timelines, and potentially higher risk of project delays and cost overruns.

What Additional Programs Should Be Integrated? This report has focused primarily on three key HHS programs: Medi–Cal, CalFresh, and CalWORKs. However, the state administers additional HHS programs that could also at some point be integrated with these three programs. As the Legislature considers its broader vision for integration, it could prioritize programs for inclusion in future integration efforts. In our view, the Legislature should consider giving priority to programs that (1) have the greatest overlap with key HHS programs in the populations they serve, (2) rely on some of the same automation systems as other key programs, and (3) are administered by the same state or local agencies as other key programs. For example, the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program would likely be a higher priority for integration under these criteria, as (1) it serves individuals that often also qualify for CalFresh or CalWORKs, (2) the Electronic Benefit Transfer System (which currently provides benefits for CalWORKs and CalFresh clients) could be used to distribute WIC benefits, and (3) in some cases it is administered out of county human services departments.