Overview of Human Services Budget. The Governor’s budget proposes $10.9 billion from the General Fund for human services programs—a 4.3 percent increase above 2014–15 estimated expenditures. For the most part, the year–over–year changes reflect the implementation of previously enacted policy changes as well as changes in caseload, utilization of services, and costs per unit of service, as opposed to new policy proposals. The Governor’s budget proposal for human services programs reflects significant fiscal uncertainty relating to federal actions in a number of programmatic areas. For example, the President’s recent executive action on immigration would have a highly uncertain fiscal impact on human services programs.

Programmatic and Spending Trends Since 2007–08. Our review of trends in the major human services programs since 2007–08 (the last budget developed before the recent recession) finds that total spending is up by 11 percent (in inflation–adjusted terms), with major changes in how human services programs are funded. Specifically, there has been an increasing reliance on federal funds and realignment revenues and less reliance on the General Fund. Caseloads are up in all major programs, cash assistance payments and some provider rates have fallen in real terms, and while funding for some program reductions made during recessionary times have been fully or partially restored, other program reductions continue today. In addition, the Legislature has made a select group of program augmentations since 2007–08 as well.

Uncertain Legal Status of Federal Labor Regulations Affecting In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS) Program and Department of Developmental Services (DDS). A federal court has blocked the implementation of new federal labor regulations (originally set to take effect on January 1, 2015) that would have required the payment of overtime compensation and other payments to home care workers in IHSS and DDS’s community program. This court decision has been appealed. The Legislature will need to account for this legal uncertainty in approving the IHSS and DDS budgets. To the extent funding budgeted in 2014–15 and 2015–16 to implement the federal regulations is no longer needed because the federal court’s decision is ultimately upheld on appeal, monies would be freed up for other legislative priorities.

Proposed Restoration of IHSS Service Hours Previously Reduced. The Governor’s budget proposes to use revenue from a restructured managed care organization tax to provide the nonfederal share of funding needed to restore service hours from the 7 percent reduction in hours enacted in 2013–14. We find the Governor’s overall concept to be a reasonable approach to allow for this funding restoration.

Developmental Center (DC) Closure Plans Needed. Federal and state policy promotes the integration of individuals with developmental disabilities into community settings. In furtherance of this policy, and supported by our analysis of the fiscal merits of transitioning DC residents to community settings, we recommend that the Legislature move torward closure of Fairview and Sonoma DCs.

Governor Proposes Next Steps in Addressing Program Deficiencies in Community Care Licensing (CCL). The Governor’s budget proposes a multiyear, multistage plan to reform the CCL program that oversees the licensing of child care, children’s residential, and adult and senior care facilities. This proposal builds on reforms enacted in the 2014–15 budget to address recent health and safety issues discovered at these CCL–licensed facilities. Overall, we find that the Governor’s proposal is responsive to the Legislature’s interest in decreasing the lengthy time interval (currently as long as five years) between required inspections. We think that increasing the inspection frequency for all facility types to at least once every three years—the first stage of the Governor’s proposal—is a reasonable first step. However, we think it is premature to approve the Governor’s proposal to further increase inspection frequencies in the subsequent stages of his plan until enforcement data is reviewed in an effort to target enforcement resources as cost–effectively as possible.

Continuum of Care Reform (CCR) Budget Proposal Should Be Justified in Context of Broader Reform Effort. The Governor’s budget proposes funding in 2015–16 to implement 2 of 19 recommendations of a working group established by the Legislature to recommend revisions to rates, services, and programs in the foster care system. The impetus for the reform effort is to further state law that requires that foster children be placed in the least restrictive, most family–like setting possible. While we think that the budget proposal appropriately focuses first on building capacity in home–based settings, we are unclear on how the proposed funding fits into the broader CCR implementation and how the funding would help achieve CCR objectives. We therefore recommend that the administration provide the needed justification at budget hearings.

California’s major human services programs provide a variety of benefits to its citizens. These include income maintenance for the aged, blind, or disabled; cash assistance and welfare–to–work services for low–income families with children; protecting children from abuse and neglect; providing home care workers who assist the aged and disabled in remaining in their own homes; collection of child support from noncustodial parents; and subsidized child care for low–income families.

Human services are administered at the state level by the Department of Social Services (DSS), DDS, Department of Child Support Services, and other California Health and Human Services Agency departments. The actual delivery of many services takes place at the local level and is typically carried out by 58 separate county welfare departments. A major exception is Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP), which is administered mainly by the U.S. Social Services Administration. In the case of DDS, community–based services (the type of services received by the vast majority of DDS consumers) are coordinated through 21 nonprofit organizations known as regional centers (RCs).

Recent Major Changes in Funding for Human Services Programs. As a result of realignment–related legislation in 2011 and 2013, the budget reflects shifts to counties of a significant amount of General Fund costs in human services programs. Specifically, as a result of 2011 legislation, the budget (beginning in 2011–12) reflects shifts to local realignment revenues of about $1.1 billion of General Fund costs in the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program and about $1.6 billion in child welfare and adult protective services General Fund costs. As a result of the latter shift, the state’s role with respect to child welfare and adult protective services is largely one of oversight of county administration of these program areas.

Legislation enacted in 2013 shifted additional General Fund costs in the CalWORKs program to local realignment revenues that previously have been used to provide health services to indigent individuals. These realignment revenues have been freed up given that many indigent individuals are newly eligible for coverage in the state–funded Medi–Cal program. Specifically, the budget shifts $300 million in CalWORKs General Fund costs to these local realignment revenues in 2013–14, $725 million in 2014–15, and $698 million in 2015–16. The 2013 legislation additionally provided that the costs of specified ongoing increases to CalWORKs assistance payments will be shifted to revenues from the growth of existing local realignment revenues that otherwise would have supported other human services programs. We discuss the statutorily driven CalWORKs grant increases in greater detail later in the “CalWORKs” section in this report.

Overview of Human Services Budget Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes expenditures of about $10.9 billion from the General Fund for human services programs in 2015–16. As shown in Figure 1, this reflects an increase of $444 million—or 4.3 percent—above revised General Fund expenditures in 2014–15.

Figure 1

Major Human Services Programs and Departments—Budget Summary

General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2013–14

Actual

|

2014–15

Estimated

|

2015–16

Proposed

|

Change From 2014–15 to 2015–16

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

SSI/SSP

|

$2,772.6

|

$2,805.0

|

$2,834.0

|

$29.0

|

1.0%

|

|

Department of Developmental Services

|

2,801.0

|

3,098.1

|

3,298.8

|

200.7

|

6.5

|

|

CalWORKs

|

1,161.9

|

650.0a

|

663.2

|

13.2

|

2.0

|

|

In–Home Supportive Services

|

1,926.3

|

2,246.1

|

2,449.7

|

203.6

|

9.1

|

|

County Administration and Automation

|

674.5

|

843.6

|

842.2

|

–1.4

|

–0.2

|

|

Department of Child Support Services

|

304.6

|

313.6

|

313.6

|

—

|

—

|

|

Department of Rehabilitation

|

57.0

|

58.4

|

58.4

|

—

|

—

|

|

Department of Aging

|

31.5

|

32.3

|

30.4

|

–1.9

|

–5.9

|

|

All other social services (including state support)

|

253.0

|

415.9

|

416.2

|

0.3

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$9,982.4

|

$10,463.0

|

$10,907.3

|

$444.3

|

4.3%

|

Summary of Major Budget Proposals and Changes. As shown in Figure 1, the budget reflects generally stable General Fund expenditures across a majority of human services programs, with relatively significant growth in DDS and IHSS expenditures being the exceptions.

The 6.5 percent growth ($202 million) in DDS General Fund expenditures is driven largely by caseload growth and higher utilization of community services. The year–over–year expenditure growth also reflects a new spending proposal for $18.1 million in 2015–16 to increase capacity in the secured treatment program at Porterville DC.

The 9.1 percent growth ($204 million) in IHSS General Fund expenditures largely reflects the annualized cost of complying with new federal labor regulations (currently unenforceable pursuant to a court order, as discussed later), caseload growth, and higher costs per service–hour as a result of wage increases. As also discussed below, the Governor’s budget proposes to restore IHSS hours that were eliminated as a result of the current 7 percent reduction in service hours initially enacted as a budget solution in a prior year. Funding for this restoration, however, is proposed to come from a restructured tax on managed care organizations, rather than from the General Fund.

It is important to note that the modest (2 percent) year–over–year net growth in CalWORKs General Fund expenditures masks a number of both cost increases and savings. On the cost front, the budget reflects increased costs for the full–year implementation of items adopted as part of the 2014–15 budget package, including the April 2015 grant increase (partially funded from the General Fund) and the extension of eligibility for drug felons. On the savings front, the budget reflects a projected decrease in caseload and the increased utilization of non–General Fund monies.

Budgetary Uncertainty Related to Federal Actions. The Governor’s budget proposal for human services programs reflects significant fiscal uncertainty relating to federal actions in a number of programmatic areas. We highlight these uncertainties in Figure 2 and later discuss some of the key ones in greater detail.

Figure 2

Human Services Budgetary Uncertainty Related to Federal Actions

|

Issue

|

Budgetary Uncertainty

|

|

Implementation of new federal labor regulations for In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS) and Department of Developmental Services (DDS)

|

The 2015–16 budget includes a combined total of $342 million General Fund in IHSS and DDS to make overtime and other required payments pursuant to new federal labor regulations. However, if a current lower federal court ruling invalidating the regulations is upheld, the state would realize General Fund savings.

|

|

Presidential executive action on immigration

|

If the President’s executive action takes effect, some undocumented immigrants may newly qualify for state human services programs, including IHSS and the Cash Assistance Program for Immigrants. The potential cost increase to the state’s human services programs resulting from this action is highly uncertain.

|

|

Federal funding of developmental centers (DCs)

|

The budget assumes that the state will retain federal Medicaid funding for DCs, despite DCs not meeting federal certification requirements. If the state does not make sufficient improvements to DCs, then a total of about $103 million in annual federal funding is at risk. Historically, lost federal funds for the DCs have been backfilled with General Fund monies.

|

|

Federal CalFresh administration funding target

|

The federal government typically pays 50 percent of CalFresh administrative costs. However, projected need for federal funds in 2014–15 and 2015–16 exceeds a federal funding maximum target. In the past, federal administrative funds from other states that spent below their respective targets were made available to California. To the extent that such funds are not available, as much as $270 million in additional General Fund spending would be required over the two years should the state backfill the lost federal funds.

|

|

Federal Title IV–E funding (foster care) disallowance

|

The federal government identified an instance of noncompliance with Title IV–E foster care regulations and has ordered the state to repay Title IV–E funds, with interest, that were disallowed because of the noncompliance. The state has appealed the disallowance, but has also set aside $50 million (General Fund) should the appeal be rejected. These set–aside dollars would become available for other purposes should the state’s appeal succeed.

|

Generally Varied Growth Through Most Recent Recession. While caseload grew for most of the state’s human services programs during the most recent recession, there was substantial variability in the growth rate across programs. This variability largely reflects the extent to which a program’s caseload is susceptible to economic fluctuations. (One key exception to this recessionary caseload growth is the state’s foster care caseload, which has declined since 2001 and through the recession. In part, this reflects the creation of the Kinship Guardian Assistance Payment program in 2000 that facilitates a permanent placement option for relative foster children outside of the foster care system.)

Both Caseload Growth and Declines Since Recession. Since the end of the most recent recession several years ago, caseloads in human services programs that are particularly sensitive to economic fluctuations—such as CalWORKs—have experienced year–over–year caseload declines as the economy improved. Other program areas—those that are less sensitive to economic fluctuations, such as DDS—have generally experienced caseload growth. We now turn more specifically to caseload trends in IHSS, DDS, and CalWORKs and the budget’s assumptions regarding caseload for these three program areas in 2015–16.

IHSS Caseload Projected to Grow Modestly in 2015–16. The budget projects the average monthly caseload for IHSS to be 462,648 in 2015–16—a 3.7 percent increase over the most recent estimate of 2014–15 caseload.

DDS Community Caseload Continues to Grow. The budget projects the average monthly DDS caseload in the community to be 288,317 in 2015–16—a 3.5 percent increase over estimated 2014–15 caseload. This caseload has grown steadily at similar percentage increases over each of the last several years, largely reflecting increased diagnoses of autism, the moratorium on the placement of consumers in state DCs, and general population growth.

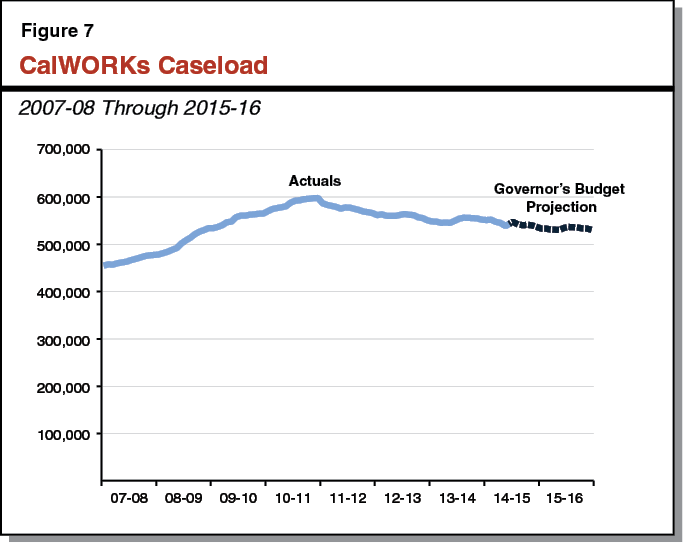

CalWORKs Caseload Continues to Decline. In the midst of the most recent recession, the CalWORKs caseload rose substantially and peaked at over 597,000 cases in June 2011. The caseload has been declining since that time due to enacted policy changes and an improving labor market. The budget assumes an average monthly CalWORKs caseload of 543,557 in 2014–15—a decline of 1.3 percent from the prior year. The year–over–year decline in caseload is projected to accelerate slightly to 1.9 percent in 2015–16, resulting in an average monthly caseload of 533,335. While caseload is declining, resulting in savings on cash assistance payments, the number of CalWORKs cases utilizing services is expected to modestly increase, partially offsetting cash assistance savings.

The Legislature has expressed significant recent interest in the issue of the level of the state’s spending in human services programs today compared to pre–recession levels (the 2007–08 state budget was the last budget developed before the recent recession). As with all areas of the budget, significant General Fund budget reductions were made in the human services policy area to help balance the budget during the recessionary years. This section is intended to provide information to the Legislature to be able to make a meaningful comparison between (1) the state’s spending and programmatic service/benefit levels in human services programs in the 2007–08 budget and (2) the level of spending and service/benefit levels for such programs proposed in the 2015–16 Governor’s Budget. For the state’s major human services programs, we discuss caseload trends, changes in how programs are funded, changes in eligibility and service/benefit levels, and other main drivers explaining the difference between 2007–08 and 2015–16 spending levels.

As shown in Figure 3, when all funding sources flowing through the state budget are considered (including federal funds), total spending in human services programs has grown by 25 percent between 2007–08 and the Governor’s 2015–16 budget proposal. After adjusting for inflation, the increase in spending is 11 percent.

Figure 3

The Human Services State Budget:

Pre–Recession Versus 2015–16 Proposal

(Dollars in Billions)

|

Fund Source

|

2007–08

Actual

|

2015–16

Proposed

|

Change From

2007–08 to 2015–16

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

General Fund

|

$12.0

|

$10.9

|

–$1.1

|

–9%

|

|

Federal fundsa

|

12.1

|

15.1

|

3.0

|

25

|

|

Realignment revenues

|

1.6

|

6.3

|

5.7

|

342

|

|

Other special funds

|

0.7

|

0.7

|

—b

|

2

|

|

Totals (All Funds)

|

$26.4

|

$33.0

|

$6.6

|

25%

|

Embedded in this total spending increase over the period are substantial changes in how human services programs are funded. Specifically, while General Fund spending has declined over this period, spending from federal funds and realignment revenues has increased substantially. To a significant extent, federal funds and realignment revenues are replacing what otherwise would have been General Fund expenditures, thereby driving down General Fund expenditures without a concomitant decrease in program benefit and service levels. (Realignment revenues are replacing General Fund expenditures in the child welfare services, adult protective services, and CalWORKs program areas.) As a result, General Fund spending on human services as a percentage of the total state General Fund budget decreased from 11.6 percent in 2007–08 to 9.6 percent in the 2015–16 budget proposal. Below, we provide a more in–depth comparison of pre–recession versus 2015–16 spending on a program–by–program basis, drilling down into how the caseload served, eligibility, benefit and service levels, and funding mix have changed over this period.

A benefit of the state–federal Medicaid program—known as Medi–Cal in California, IHSS provides in–home personal care and domestic services to low–income aged, blind, and disabled individuals.

Significant Expenditure Growth. In the period from 2007–08 to the budget proposed for 2015–16, IHSS expenditures have grown from $5 billion ($1.7 billion state funds) to $8.2 billion ($2.7 billion state funds), or an increase of 65 percent.

Caseload Growth. In the period from 2007–08 to the budget proposed for 2015–16, the IHSS caseload has grown from 400,156 individuals to an estimated 462,648 individuals, or an increase of 15.6 percent.

Service Hours From 7 Percent Reduction Proposed to Be Restored in 2015–16. Over the nine–year period from 2007–08 to 2015–16, IHSS recipients have experienced reductions in service hours. From 2010–11 to 2012–13, a 3.6 percent reduction in service hours was generally in effect, increasing to an 8 percent reduction in 2013–14, and ratcheting down to a 7 percent reduction in 2014–15. (We note that the 8 percent and 7 percent reductions were enacted in 2013 in relation to an IHSS settlement agreement that resolved two class–action lawsuits related to previously enacted IHSS budget reductions that had not taken effect.) The 2015–16 budget proposes to fully restore service hours from the 7 percent reduction.

Other Factors Explaining Growth in Spending. After accounting for inflation and caseload growth, the remaining significant growth in total spending between 2007–08 and 2015–16 reflects several factors, including the assumed implementation beginning in 2014–15 of new federal labor regulations (requiring the payment of overtime and the payment for previously uncompensated activities of IHSS providers), wage increases (both state–mandated minimum wage increases and wage increases negotiated at the county level), and higher average utilization of IHSS among recipients.

State Share of IHSS Costs Has Decreased Slightly. The IHSS program is funded through a combination of state funds, county realignment funds, and federal Medicaid funding. Beginning in 2011–12, the federal government began providing an enhanced reimbursement rate for a significant portion of the IHSS caseload, which has caused the federal share of costs to increase. In 2012–13, the Legislature enacted a county maintenance–of–effort (MOE) requirement, in which counties generally maintain their 2011–12 expenditure level for IHSS. The county MOE has caused the county share of IHSS costs to decrease. On net, the state share of IHSS costs has decreased slightly from 33.2 percent in 2007–08 to 32.5 percent in 2015–16.

The SSI/SSP program provides cash grants to low–income aged, blind, and disabled individuals. The state’s General Fund provides the SSP portion of the grant while federal funds pay for the SSI portion of the grant.

Modest Growth in Overall Program Spending. Total spending for SSI/SSP grants—including General Fund and federal expenditures (which are not passed through the state budget)—has increased by about $1.1 billion—or 12 percent—between 2007–08 and 2015–16. As this spending is less than the rate of inflation over this time period (roughly 14 percent), total spending has decreased slightly in real terms.

Modest Caseload Growth. In the period from 2007–08 to the budget proposed for 2015–16, the SSI/SSP caseload has grown from 1,235,932 individuals to an estimated 1,310,977 individuals, or an increase of 6.1 percent.

Decline in State–Funded Grant Levels. Historically, the state provided an annual cost–of–living adjustment (COLA) for the SSI/SSP grant. However, the state has not provided a COLA since June 2008 and no COLA is proposed for 2015–16. Further, over the period from 2007–08 to 2015–16, the state has significantly reduced the maximum SSP grant available for individuals and couples to the minimum allowed under federal law. We note that SSI/SSP recipients continue to receive a federally funded COLA for the SSI portion of the grant. In Figure 4, we display the maximum monthly SSI/SSP grant for individuals and couples in 2007–08, as compared to proposed grant levels for 2015–16. We also compare the grant levels in each of the two years to the federal poverty level (FPL) in that year (the FPL is adjusted annually for inflation). Reflecting SSP grant reductions and the suspension of the state COLA, the combined SSI/SSP maximum monthly grant for individuals and couples has declined significantly as a percentage of FPL over the nine–year period. After adjusting for inflation, the maximum combined SSI/SSP grant proposed for 2015–16 (1) for individuals represents roughly $76 (8.7 percent) less purchasing power than was provided in 2007–08 and (2) for couples represents roughly $190 (12.4 percent) less purchasing power than was provided in 2007–08.

Figure 4

SSI/SSP Maximum Monthly Grants Pre– and Post–Recession

|

|

2007–08

|

2015–16

Proposeda

|

|

Maximum Grant—Individuals

|

|

|

|

SSI

|

$637

|

$744

|

|

SSP

|

233

|

156

|

|

Totals

|

$870

|

$900

|

|

Percent of FPL

|

102.3%

|

91.8%

|

|

Maximum Grant—Couples

|

|

|

|

SSI

|

$956

|

$1,116

|

|

SSP

|

568

|

396

|

|

Totals

|

$1,524

|

$1,512

|

|

Percent of FPL

|

133.6%

|

113.9%

|

The DDS oversees the provision of services and supports for individuals with developmental disabilities. Community–based services are coordinated through 21 nonprofit organizations known as RCs.

Significant Expenditure Growth. In the period from 2007–08 to the budget proposed for 2015–16, DDS expenditures will have grown from $4.4 billion ($2.7 billion state funds) to an estimated $5.7 billion ($3.3 billion state funds), or an increase of 30.9 percent.

Significant Caseload Growth. In the period from 2007–08 to the budget proposed for 2015–16, the total DDS caseload has grown from 223,737 individuals to an estimated 289,327 individuals, or an increase of 29.3 percent.

Most Budget Solutions Implemented Since 2007–08 (and Earlier) Remain in Place. During the most recent period of budget deficits, the Legislature enacted numerous DDS budget reductions and cost savings measures in order to yield General Fund savings, such as rate restrictions for RC vendors, service changes, and reliance on increased federal funding. Rates paid to vendors established by statute or by the department have generally been frozen since 2003–04. Rates negotiated by the RCs for new vendors were limited beginning in 2008 to no higher than the median rate for that service. On top of the rate freezes and restrictions, temporary rate reductions were implemented broadly to RC vendors from 2009–10 through 2012–13, but these were completely lifted in 2013–14. In 2009–10, service reductions and eligibility restrictions were implemented in the Early Start program, which provides early intervention services to infants and toddlers under the age of three who have a developmental disability or delay(s). While the Early Start service reductions continue, the Early Start eligibility criteria were restored to the threshold in place prior to 2009 as of January 1, 2015. Also in 2009–10, the DDS suspended the availability of certain services, including social/recreation activities, camping services and associated travel, educational services for school–aged children, and certain nonmedical therapies. The Governor’s budget does not propose any restorations for these suspended services. Collectively, the Early Start service reductions and service suspensions that continue are estimated to create General Fund savings in the low tens of millions of dollars annually.

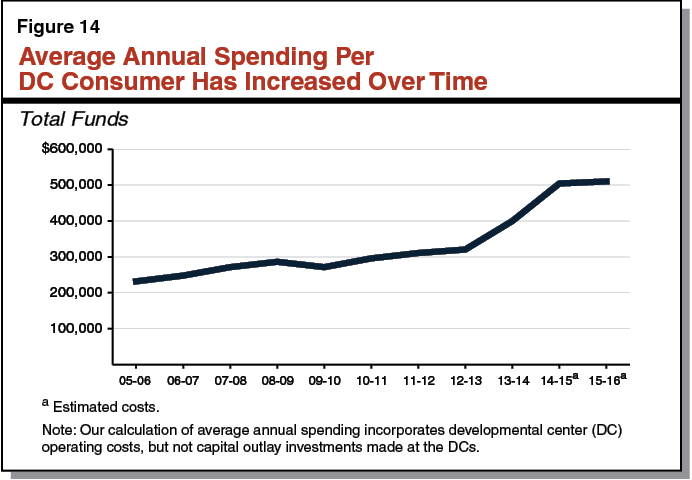

Figure 5 shows average spending per consumer over the period. While such spending has increased slightly in nominal terms, it has fallen by 9.5 percent once adjusted for inflation.

Figure 5

DDS Average Spending Per Consumer Pre– and Post–Recession

|

|

2007–08

|

2015–16 Proposed

|

|

Total funds (in millions)

|

$4,356

|

$5,699

|

|

Total caseload

|

223,737

|

289,327

|

|

Average spending per consumer

|

$19,467

|

$19,699

|

|

Average spending per consumer—adjusted for inflation

|

$19,467

|

$17,617

|

Federal Share of Costs Has Increased. The DDS is funded through a combination of state and federal funds. In 2007–08, 38 percent of total DDS costs were paid for by federal funds. In 2015–16, 42 percent of total DDS costs are proposed to be paid for by federal funds. This increase in federal funding is due primarily to the state’s efforts to increase federal Medicaid funding during the recent period of budget deficits.

CalWORKs provides cash grants and welfare–to–work services to families whose income is inadequate to meet their basic needs.

Total Expenditures Have Risen 11 Percent. From pre–recession levels in 2007–08, the Governor’s CalWORKs proposal for 2015–16 represents an increase in total spending (from all fund sources) of 11 percent—from $5.2 billion to $5.8 billion. As shown in Figure 6, total funding has increased slightly over this period for cash assistance, services, and county administration. Growth in services and administration has somewhat outpaced growth in cash assistance.

Figure 6

CalWORKs Funding Before and After Recession

|

|

2007–08 Actual

|

|

2015–16 Proposed

|

|

Funds

|

Share of Total

|

Funds

|

Share of Total

|

|

Spending by Purpose (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cash assistance

|

$3,006

|

58%

|

|

$3,242

|

56%

|

|

Services and county administration

|

2,031

|

39

|

|

2,348

|

41

|

|

Other

|

142

|

3

|

|

181

|

3

|

|

Total Funding

|

$5,179

|

100%

|

|

$5,771

|

100%

|

|

|

2007–08 Actual

|

|

2015–16 Proposed

|

|

Funds

|

Share of Total

|

Funds

|

Share of Total

|

|

Spending by Fund Source (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Federal funds

|

$3,765

|

69%

|

|

$2,928

|

51%

|

|

State General Fund

|

1,319

|

29

|

|

663

|

11

|

|

County funds

|

95

|

2

|

|

2,180a

|

38

|

|

Total Funding

|

$5,179

|

100%

|

|

$5,771

|

100%

|

Significant Program Costs Shifted From General Fund to County Funds. As shown in Figure 6, the mix of funds supporting the CalWORKs program has changed significantly from 2007–08 to 2015–16. Over this period, the state has taken several actions to shift General Fund CalWORKs costs to counties, primarily through state–local realignment. Specifically, in 2011, the state provided dedicated revenues to counties to meet additional fiscal responsibilities in several areas. Of these new funds, $1.1 billion annually was directed to pay for an increased county share of existing CalWORKs grant costs, directly offsetting General Fund spending. In 2013, the state began redirecting realignment funds used by counties to provide indigent healthcare to instead pay for an additional county share of CalWORKs grant costs. The amount redirected each year corresponds to estimated county savings resulting from the shift of low–income individuals into Medi–Cal. This transfer, at an estimated $698 million in 2015–16, also directly offsets General Fund spending in CalWORKs. Finally, in 2013, the state also redirected future growth in certain other realignment funds to pay for the costs of future CalWORKs grant increases. These funds generally pay for new CalWORKs costs instead of directly offsetting existing General Fund costs, but will continue to increase the portion of CalWORKs supported by county funds over time.

Caseload Rose During Recession, Remains Above Pre–Recession Levels by 14 Percent. During 2007–08, an average of 465,951 families received CalWORKs assistance each month. As shown in Figure 7, during the recession, the monthly CalWORKs caseload reached nearly 600,000 (in June 2011) and has been declining since that time. The Governor’s budget assumes that the average monthly caseload during 2015–16 will be 533,335 families—14 percent higher than in 2007–08, but lower than the recession’s peak caseload.

Adult Eligibility for Aid Tightened. In general, adult eligibility for CalWORKs is time limited and able–bodied adults are subject to a work requirement. In July 2011, the lifetime maximum number of months that an adult could receive CalWORKs assistance was reduced from 60 to 48. This reduction in the amount of time over which an adult can receive CalWORKs assistance was one of the most important policy changes made to the program since 2007–08. It was estimated to save the state about $110 million when initially implemented (this savings amount would have declined slightly due to lower caseload today). There have also been major policy changes related to the work requirement that applies within the 48 months of assistance; however, these policy changes are not expected to create significant budgetary savings.

Grants Reduced, Then Partially Restored. In 2007–08, a family of three with no other income received a CalWORKs grant of $723 per month. Since 2007–08, CalWORKs grants have been both reduced and increased. Specifically, in 2009, grants were reduced by 4 percent and a statutory COLA that automatically adjusted grants for changes in inflation was eliminated. Grants were further reduced by 8 percent in 2011. Grants were later increased by 5 percent in 2014, and are scheduled to be increased by 5 percent again in April 2015. Both of these increases were provided through a new statutory mechanism that functions like a COLA, but bases automatic grant increases on availability of funds from a dedicated fund source rather than cost of living. The Governor’s proposal assumes no additional grant increase in 2015–16, such that the same family of three with no earned income would receive a grant of $704 per month—$19 (about 3 percent) lower than in 2007–08. After adjusting for inflation, the CalWORKs grant amount for this family proposed for 2015–16 represents roughly $115 (14 percent) less purchasing power than was provided in 2007–08. Because recent increases have not fully restored past reductions, and because the statutory COLA was eliminated, grants have also fallen as a percentage of FPL (a poverty threshold that is adjusted for inflation) between 2007–08 and 2015–16. Federally funded CalFresh food benefits (which CalWORKs families generally receive) are adjusted for inflation and have risen since 2007–08; however, combined CalWORKs and CalFresh food assistance have still fallen as a percentage of FPL from 2007–08 to 2015–16, as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8

Monthly CalWORKs Grant and CalFresh Benefit Pre– and Post–Recessiona

|

|

2007–08

|

2015–16

Proposed

|

Change

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Grant

|

$723

|

$704

|

–$19

|

–3%

|

|

CalFresh benefit

|

356

|

493

|

137

|

38

|

|

Totals

|

$1,079

|

$1,197

|

$118

|

11%

|

|

Grant as percent of FPL

|

51%

|

42%

|

|

|

|

Grant and CalFresh benefit as percent of FPL

|

75

|

71

|

|

|

Employment Services Funding Temporarily Reduced. . . Beginning in 2009–10 and continuing through the first half of 2012–13, the Legislature reduced county funding for CalWORKs services (initially by $420 million) and exempted certain CalWORKs families with young children from the program’s work requirement, thus reducing demand for services and allowing counties to manage the reduction. This reduction, and the associated exemption, was slowly phased out in 2013 and 2014. As formerly exempt recipients became subject to the work requirement, county funding for services was restored.

. . . Then Augmented With Early Engagement Strategies. The 2013–14 budget package included funding for three new strategies intended to better identify and address CalWORKs recipients’ barriers to employment early in their time on aid. These strategies included (1) ongoing funding to pay for additional subsidized employment opportunities for CalWORKs recipients, (2) the creation of the Family Stabilization Program within CalWORKs to provide intensive case management for families experiencing destabilizing crisis situations that interfere with their ability to meet the work requirement, and (3) the creation of a new online appraisal tool to comprehensively evaluate recipients as they enter the program to identify barriers to employment. This online appraisal tool is expected to be implemented statewide during 2015–16. The collective cost of these early engagement strategies in 2015–16 is about $140 million.

Other Program Reductions, Restorations, and Augmentations. Other relatively smaller CalWORKs reductions, restorations, and augmentations (each in the range of low to mid tens of millions of dollars) have taken place since 2007–08. For example, reimbursement rates for child care provided to certain CalWORKs families were reduced on an ongoing basis. The mechanism that allows CalWORKs families to keep a portion of their grant as their earnings increase was reduced and later restored. Case management services in Cal–Learn, a program within CalWORKs that helps pregnant and parenting teens complete high school, was eliminated and later restored. In 2014, a new Housing Support Program was created in CalWORKs, and CalWORKs eligibility will be expanded to individuals with prior drug felony convictions beginning in April 2015.

In summary, the main takeaways from our analysis of programmatic and spending trends in the major human services programs since 2007–08 are as follows:

- Spending Up, Funding Mix Changed. While total spending has gone up in real (inflation–adjusted) terms—by about 11 percent—there have been major changes in how programs are funded. Specifically, there has been an increasing reliance on federal funds and realignment revenues and less reliance on the General Fund. For the most part, these funding shifts have no affected program service levels.

- Caseloads Up. Caseloads have risen in all major human services programs since 2007–08, many at rates faster than the rate of growth of the state’s population. However, while some caseloads have grown steadily, the CalWORKs caseload—more closely tied to the state’s economy and labor market than other caseloads—reached a peak during the recession and has been declining since.

- Cash Assistance Payments and Some Provider Rates Have Fallen in Real Terms. The inflation–adjusted level of CalWORKs and SSI/SSP grants has fallen, reflecting both actual grant reductions (funding for which has not been fully restored) and the lack of COLAs in these two program areas for many years. Similarly, widespread rate freezes have applied to DDS vendors since 2003–04, meaning that these vendor rates have fallen in real terms.

- Some Programmatic Reductions Continue, but There Have Also Been Augmentations. In addition to reductions in cash assistance grant levels, there were a number of other programmatic reductions made during the recessionary period. While funding for many of these reductions has been fully or partially restored, several of the reductions continue today. For example, a number of DDS community services continue to be suspended today. On the other hand, there have also been a number of program augmentations since 2007–08. For example, the CalWORKs budget has been augmented to implement new strategies intended to better identify and address CalWORKs recipients’ barriers to employment early in their time on aid.

In 2013, the federal Department of Labor (DOL) issued revised regulations related to the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) affecting the home care industry, resulting in impacts on the state’s IHSS program and DDS. Under these new labor regulations (originally set to take effect on January 1, 2015), the state is required to make the following changes to the IHSS program: (1) provide overtime compensation—at one–and–a–half times the regular pay rate—to IHSS providers for hours that exceed 40 in a work week, and (2) make payments for newly compensable work activities of IHSS providers, including wait time during medical appointments and commute time under certain circumstances. (We note that 2014 budget–related legislation generally restricts IHSS providers to working no more than 66 hours per week.) For DDS, the state is required to provide funding to enable home care vendors to provide overtime compensation to their employees. Please refer to the “Human Services Compliance With Federal Labor Regulations” analysis in The 2014–15 Budget: Analysis of the Human Services Budget for further background on the labor regulations.

The Case Management, Information and Payrolling System (CMIPS) II is the newly implemented IT system that stores IHSS case records, provides program data reports, and processes IHSS provider payments. In order to comply with the new federal labor regulations, CMIPS II system changes would be needed to process overtime compensation and payments for newly compensable work activities, and provide other needed capabilities. Most CMIPS II system changes have already been completed in preparation for the assumed implementation of the new federal labor regulations beginning January 1, 2015. The total estimated FLSA–related project cost is $37 million ($19 million General Fund) over 2014–15 and 2015–16.

The Governor’s budget updates 2014–15 estimated expenditures for FLSA–related costs in IHSS and DDS to a total of $459 million ($212 million General Fund). This is an increase of $48 million ($30 million General Fund) above the 2014–15 enacted budget appropriation, primarily due to adjustments for IHSS administrative costs at the county level and CMIPS II system changes. Below, we provide a breakdown of these costs.

Governor’s Budget Updates 2014–15 Estimated Expenditures for FLSA–Related IHSS Costs. The Governor’s budget updates 2014–15 estimated expenditures for FLSA–related IHSS costs, including a total of $439 million ($200 million General Fund) to fund the following: overtime compensation, newly compensable work activities, administrative costs at the county level, and CMIPS II system changes. We note that the total estimated cost for FLSA compliance also includes an administration proposal to provide work limit exceptions to certain parent providers of IHSS recipients at an estimated cost of $2 million ($985,000 General Fund) in 2014–15. This exception would allow certain parent providers to exceed the work limit of 66 hours per week.

Governor’s Budget Updates 2014–15 Estimated Expenditures for FLSA–Related DDS Costs. The Governor’s budget updates 2014–15 estimated expenditures for FLSA–related DDS costs, providing $21 million ($11 million General Fund) to increase the rates paid to vendors that provide in–home care to individuals with developmental disabilities. The additional funding is intended to enable home care vendors to provide overtime compensation to their employees.

The 2015–16 proposed budgets for IHSS and DDS provide a total of $758 million ($342 million General Fund) to annualize the cost of complying with the new labor regulations. Below, we provide a breakdown of these costs.

IHSS Budget Includes $717 Million ($319 Million General Fund). The 2015–16 proposed budget for IHSS annualizes the cost of complying with the new labor regulations, including a total of $717 million ($319 million General Fund). This amount includes about $1 million ($513,000 General Fund) for a total of eight positions—four new limited–term positions and the extension of four CMIPS II limited–term positions—at DSS to address workload related to implementation of the new federal labor regulations.

DDS Budget Includes $41 Million ($22 Million General Fund). The 2015–16 proposed budget for DDS annualizes the cost of complying with the new labor regulations, including $41 million ($22 million General Fund) to increase the rates paid to home care vendors to enable them to provide overtime compensation to their employees.

In Figure 9, we provide a breakdown of FLSA–related costs budgeted for IHSS and DDS in 2014–15 and 2015–16.

Figure 9

FLSA–Related Costs Budgeted for IHSS and DDS

(In Millions)

|

|

2014–15 Estimated

|

|

2015–16 Proposed

|

|

General Fund

|

Total Funds

|

General Fund

|

Total Funds

|

|

IHSS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Overtime compensation

|

$87.6

|

$200.8

|

|

$166.4

|

$385.2

|

|

Newly compensable work activities

|

69.7

|

152.2

|

|

146.2

|

319.1

|

|

Work limit exception for certain parent providers

|

1.0

|

2.1

|

|

2.0

|

4.4

|

|

Administrative costs at the county level

|

25.3

|

50.4

|

|

1.7

|

3.3

|

|

DSS staffing request

|

—

|

—

|

|

1.0

|

0.5

|

|

Subtotals

|

($183.6)

|

($405.6)

|

|

($317.3)

|

($712.5)

|

|

CMIPS II system changes

|

$16.7

|

$33.0

|

|

$2.0

|

$4.0

|

|

IHSS Totals

|

$200.3

|

$438.6

|

|

$319.3

|

$716.6

|

|

DDS

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rate increase for home care vendors

|

$11.3

|

$20.7

|

|

$22.4

|

$41.4

|

|

Grand Totals

|

$211.6

|

$459.3

|

|

$341.7

|

$758.0

|

In a lawsuit brought by associations of home care companies, a federal district court recently ruled that DOL overreached its rulemaking authority when it promulgated the revised FLSA regulations for the home care industry. Effectively, the court ruling invalidates the DOL’s new regulations, removing any requirement for the state to (1) provide funding for overtime compensation for IHSS and DDS, and (2) provide payments for wait and commute time for IHSS providers.

DOL Appeal Creates Fiscal Uncertainty for the State. At the time of this analysis, the DOL had appealed the federal court ruling. It is therefore uncertain as to whether the federal labor regulations will eventually go into effect, requiring the state to implement overtime compensation for IHSS and DDS, make the wait and commute time payments for IHSS, and complete the CMIPS II system changes needed to fully conform with the new regulations and related rules specified in 2014 budget–related legislation. It is our understanding that the appeal proceedings will occur on an expedited schedule. It is therefore possible that the court case could be resolved within 2014–15 or in the beginning of 2015–16, and—if DOL prevails—the state would be required to implement the payments.

State Implementation of Additional Payments Halted if Federal Regulations Are Deemed Ineffective. Budget–related legislation enacted in 2014 deletes state implementation of overtime compensation for IHSS and DDS as well as the wait and commute time payments for IHSS in the event that the federal labor regulations are deemed ineffective. Consistent with this statutory direction, both DSS and DDS halted the commencement of these payments related to the labor regulations (scheduled to have begun on January 1, 2015) in light of the federal court ruling. Further, the 2014 budget–related legislation for IHSS requires that the funding appropriated for FLSA–related costs remain within the IHSS budget. We address this aspect of the legislation below.

Legislature Can Use Freed–Up Funding as It Sees Fit. Given the invalidation of the federal labor regulations for now, the Legislature can use the 2014–15 funding appropriated for FLSA–related costs toward an alternative purpose. Although 2014 budget–related legislation requires the funding appropriated for FLSA–related IHSS costs to remain within the IHSS budget, the Legislature is free to enact new legislation specifying its intent to use the funding—about $184 million General Fund—for any purpose. We note that the $11 million General Fund from the updated 2014–15 DDS budget is also available for alternative purposes, and the Legislature could specify its intent on how to use the funding. Alternatively, if the Legislature does not take any action, there are two possible scenarios. First, these monies intended for FLSA–related purposes could remain unspent, with the funding reverting to the General Fund at the end of 2014–15, thereby building up the state’s General Fund reserve. As a second scenario, the departments could spend some or all of these funds on other purposes. This would reduce or eliminate the amount available for other legislative priorities.

Funds Appropriated in 2014–15. If the Legislature is concerned about the possibility that DSS and DDS could spend some or all of the 2014–15 funding appropriated for FLSA–related costs on other purposes, the Legislature would want to enact legislation specifically reverting these funds so that they would be available for any legislative priority.

Amounts Proposed for 2015–16. The uncertainty as to whether the federal labor regulations will be implemented in 2015–16 lead us to recommend that the Legislature wait until the May Revision before making a decision related to the 2015–16 FLSA–related appropriations for IHSS and DDS. Because of the expedited appeal filed by DOL, there is a fiscal risk that, if the court’s decision is overturned, the regulations could go into effect during 2015–16, requiring the state to provide overtime compensation and other payments for much of 2015–16. At the May Revision, we may know more about the timing of the fiscal risk associated with the court case. At that time, we would be in a better position to advise the Legislature on how much money, if any, should be appropriated or set aside for IHSS and DDS to meet possible FLSA–related costs in 2015–16.

The state had completed most of the CMIPS II system changes needed to process overtime compensation, provide wait and commute time payments to IHSS providers, and enforce related rules when the labor regulations were invalidated in federal court. Given DOL’s appeal of the court’s decision, the uncertainty as to whether the labor regulations will eventually be implemented raises questions about the department’s plans for CMIPS II system changes. We therefore recommend that the Legislature direct DSS to report at budget hearings on the proposed plan for CMIPS II, including the following specific issues.

- Plan for Period of Legal Uncertainty. We recommend that the department report at budget hearings on its plan for FLSA–related CMIPS II system changes—including the changes that have already been made and those that have not—during the current period of legal uncertainty while validity of the regulations is being challenged in the courts. This would help the Legislature to understand the feasibility of allowing CMIPS II changes to lie in a dormant state for an extended period of uncertainty.

- Fiscal Impact if Labor Regulations Remain Invalidated. We recommend that the department also report on the fiscal impact to the CMIPS II budget if the federal labor regulations were to remain invalidated upon resolution of the court case. We anticipate that there could be some costs associated with reversing FLSA–related system changes.

- Fiscal Impact if Labor Regulations Are Upheld. Finally, we recommend that the department assess the fiscal impact to the CMIPS II budget if the federal labor regulations were to be upheld upon resolution of the court case. We anticipate that there would be a change in when expenditures to complete FLSA–related CMIPS II system changes are incurred.

Ascertaining the information we describe would enable the Legislature to assess what, if any, CMIPS II budget adjustments are appropriate.

Given the uncertainty as to whether the labor regulations will eventually be implemented—and whether such implementation will occur in 2015–16—we recommend that the Legislature hold off on taking action related to the DSS staffing request that assumed the January 1, 2015 implementation of FLSA–related changes to the IHSS program and CMIPS II. We further recommend that the Legislature direct DSS to report at budget hearings on staffing implications if the regulations remain invalid in 2015–16.

Overview of IHSS. The IHSS program provides personal care and domestic services to low–income individuals to help them remain safely in their own homes and communities. In order to qualify for IHSS, a recipient must be aged, blind, or disabled and in most cases have income below the level necessary to qualify for SSI/SSP cash assistance. The recipients are eligible to receive up to 283 hours per month of assistance with tasks such as bathing, dressing, housework, and meal preparation. Social workers employed by county welfare departments conduct an in–home IHSS assessment of an individual’s needs in order to determine the amount and type of service hours to be provided. The average number of hours that will be provided to IHSS recipients is projected to be 94 hours per month in 2015–16. In most cases, the recipient is responsible for hiring and supervising a paid IHSS provider—oftentimes a family member or relative.

The IHSS Program Receives Federal Funds as a Medi–Cal Benefit. For nearly all IHSS recipients, the IHSS program is delivered as a benefit of the state–federal Medicaid health services program (known as Medi–Cal in California) for low–income populations. The IHSS program is subject to federal Medicaid rules, including the federal medical assistance percentage reimbursement rate for California of 50 percent of costs for most Medi–Cal recipients. For IHSS recipients who generally meet the state’s nursing facility clinical eligibility standards, the federal government provides an enhanced reimbursement rate of 56 percent referred to as Community First Choice Option (CFCO). Because of the large share of IHSS recipients eligible for CFCO—about 40 percent of the caseload—the average federal reimbursement rate for the IHSS program is 55 percent. The remaining nonfederal costs of the IHSS program are paid for by the state and counties, with the state assuming the majority of the nonfederal costs. (Under the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—also known as federal health care reform—about 20,000 individuals, or 4 percent of the IHSS caseload, are projected to receive IHSS as a result of the optional Medi–Cal expansion, with their costs fully paid for by the federal government in 2015–16.)

Counties’ Share of IHSS Costs Is Set in Statute. Budget–related legislation adopted in 2012–13 enacted a county MOE, in which counties generally maintain their 2011–12 expenditure level for IHSS—to be adjusted only for increases to IHSS providers’ wages (when negotiated at the county level through collective bargaining) and an annual inflation factor of 3.5 percent beginning in 2014–15. Under the county MOE financing structure, the state General Fund assumes all nonfederal IHSS costs above counties’ MOE expenditure levels. In 2015–16, the total county MOE is estimated to be about $1 billion, an increase of $35 million above the estimated county MOE for 2014–15. To the extent wage increases negotiated at the county level are implemented in the remainder of 2014–15 or in 2015–16, the county MOE will increase by a percentage share of the annual cost of those wage increases.

Year–to–Year Expenditure Comparison. The budget proposes $8.2 billion (all funds) for IHSS expenditures in 2015–16, which is a $1 billion, or 14.4 percent, net increase over estimated expenditures in 2014–15. General Fund expenditures for 2015–16 are proposed at $2.4 billion, a net increase of $204 million, or 9.1 percent, above the estimated expenditures in 2014–15. This net increase in General Fund expenditures incorporates the $35 million increase in the county MOE (which offsets General Fund expenditures). Below, we describe the major factors that explain the net increase.

- Increase in IHSS Basic Services Costs. The budget includes $300 million ($152 million General Fund) because of (1) caseload growth of 3.7 percent and (2) higher costs per hour due to the increase in the state–mandated hourly minimum wage from $9 to $10 beginning January 1, 2016. A total of 32 counties will be impacted by the minimum wage increase, at a cost of $68 million ($34 million General Fund). (Because the state enacted the minimum wage increase, the county MOE is not adjusted to reflect cost increases associated with the new minimum wage.)

- New Federal Labor Regulations Assumed to Be Effective. The budget also proposes a net increase of $307 million ($134 million General Fund) to reflect the annualized cost of complying with new federal labor regulations, including funding for: overtime compensation, newly compensable work activities, work limit exceptions for certain parent providers, and administrative costs at the county level. The budget was developed assuming that the regulations would take effect on January 1, 2015. However, a federal court recently invalidated the regulations, and the DOL has appealed the ruling. (Please refer to the “Federal Court Blocks New Federal Labor Regulations, Impacting IHSS and DDS” analysis earlier in this report for more detail on, and our analysis of, this issue.)

- CMIPS II. Offsetting the above increases, the budget includes reduced funding for CMIPS II of $53 million ($27 million General Fund) due to expected completion of: (1) system enhancements for blind and visually impaired IHSS recipients, (2) software upgrades and associated training, and (3) one–time system changes related to assumed implementation of the new federal labor regulations in 2014–15. The CMIPS II IT system stores IHSS case records, provides program data reports, and processes IHSS provider payments. (Please refer to the “Federal Court Blocks New Federal Labor Regulations, Impacting IHSS and DDS” section for more detail on, and our analysis of, CMIPS II system changes related to the new federal labor regulations.)

Proposed Restoration of Service Hours From 7 Percent Reduction. The budget proposes to use revenue from a restructured managed care organization (MCO) tax in the amount of $216 million to provide the nonfederal share of funding needed to restore service hours from the 7 percent reduction enacted in 2013–14. (The total cost to restore service hours from the 7 percent reduction is estimated to be $483 million in 2015–16.) The current 7 percent reduction relates to terms of an IHSS settlement agreement—adopted by the Legislature—that resolves two class–action lawsuits stemming from previously enacted budget reductions. The terms of the settlement agreement require the state to pursue a revenue source other than the General Fund for the purpose of restoring service hours from the 7 percent reduction. We generally find the Governor’s overall concept to be a reasonable approach for raising revenues needed to restore service hours from the 7 percent reduction. Please refer to the “MCO Tax Modification” analysis in the Medi–Cal section of The 2015–16 Budget: Analysis of the Health Budget for a more thorough discussion of the Governor’s MCO tax proposal.

Potential Costs in IHSS and Cash Assistance Program for Immigrants (CAPI) Related to President’s Immigration Actions. We note that the President’s recent executive actions on immigration could result in additional state costs for two human services programs—IHSS and CAPI (the state–funded cash assistance program for immigrants ineligible for SSI/SSP). If the actions are ultimately implemented at the federal level, then under existing law some undocumented immigrants may newly qualify for IHSS and/or CAPI fully paid for by the state. The potential fiscal impact of these actions on human services programs is highly uncertain. Please refer to the “President’s Executive Actions on Immigration” analysis in the Medi–Cal section of The 2015–16 Budget: Analysis of the Health Budget for more discussion of the President’s immigration actions, as they potentially relate to the state’s health and human services programs.

Caseload Growth. The Governor’s budget assumes the average monthly caseload for IHSS in 2015–16 will be 462,648, an increase of 3.7 percent compared to the revised estimate of the 2014–15 average monthly caseload. We have reviewed the caseload projections for IHSS and do not recommend any adjustments at this time. We note that the caseload estimates for 2014–15 and 2015–16 do not include the average monthly caseload associated with the optional Medi–Cal expansion (about 20,000 cases) or the relatively small but likely increase in IHSS recipients as a result of the Coordinated Care Initiative (CCI). The CCI integrates IHSS, and other long–term care services and supports, into managed care plans in seven counties statewide and requires managed care plans to provide care coordination services for new plan enrollees, potentially leading to an increase in IHSS use.

Staffing–Related Budget Requests. The budget is requesting additional staff resources for the following proposals:

- Staffing Request to Comply With New Federal Labor Regulations Assumed to Be Effective. The budget proposes about $1 million ($513,000 General Fund) for a total of eight positions—four new limited–term positions and the extension of four limited–term CMIPS II positions—to address administrative workload related to implementation of the new federal labor regulations. Please refer to our analysis earlier in this report “Federal Court Blocks New Federal Labor Regulations, Impacting IHSS and DDS” for more detail on, and our analysis of, this budget request.

- Staffing Request Related to IHSS in CCI Counties. The budget requests the extension of nine existing limited–term positions through 2016–17 to address workload associated with shifting IHSS to a managed care plan benefit in seven counties under CCI. We find that this budget proposal is justified on a workload basis.

Overview of DDS. The Lanterman Developmental Disabilities Services Act of 1969 (known as the Lanterman Act) forms the basis of the state’s commitment to provide individuals with developmental disabilities a variety of services and supports, which are overseen by DDS. The Lanterman Act defines a developmental disability as a “substantial disability” that starts before age 18 and is expected to continue indefinitely. The developmental disabilities for which an individual may be eligible to receive services under the Lanterman Act include: cerebral palsy, epilepsy, autism, intellectual disabilities, and other conditions closely related to intellectual disabilities that require similar treatment (such as a traumatic brain injury). The department works to ensure that individuals with developmental disabilities over the age of three have access to services and supports that sufficiently meet their needs, preferences, and goals in the least restrictive setting. For children under the age of three with a developmental disability or delay(s), the department administers early intervention services through the Early Start program. Unlike most other public human services or health services programs, services for the developmentally disabled are generally provided without any requirements that recipients demonstrate that they or their families do not have the financial means to pay for the services themselves. The department administers two main programs for eligible individuals (referred to as consumers), described in detail below.

Community Services Program. Community–based services are coordinated through 21 nonprofit organizations known as RCs, which assess eligibility and—through an interdisciplinary team—develop individual program plans (IPPs) for eligible consumers. The DDS provides RCs with an operations budget in order to conduct these activities. The department also provides RCs with a budget to purchase services from vendors for its consumers—estimated at 278,593 in 2014–15. These services and supports can include housing, activity and employment programs, in–home care, transportation, and other support services that assist individuals to live in the community. The centers purchase more than 100 different services on behalf of consumers. As the payer of last resort, RCs generally only pay for services if an individual does not have private health insurance or if the RC cannot refer an individual to so–called “generic” services such as (1) other state–administered health and human services programs for low–income persons or (2) services that are generally provided to all citizens at the local level by counties, cities, school districts, or other agencies. We note that the majority of consumers receiving services through the Community Services Program are enrolled in Medi–Cal, California’s federal–state Medicaid health program for low–income individuals. (For a description of the Medi–Cal program, please refer to the “Medi–Cal” section of The 2015–16 Budget: Analysis of the Health Budget.)

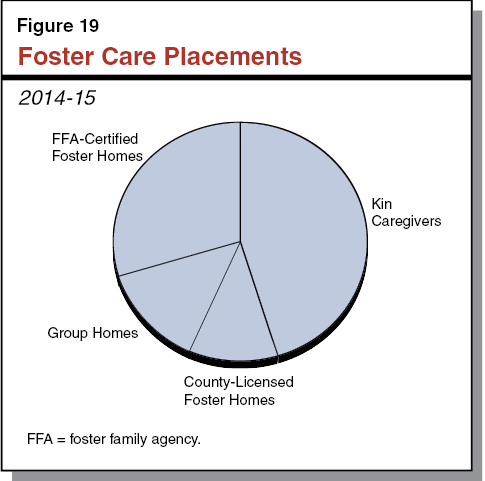

More than 99 percent of DDS consumers receive services under the Community Services Program. These consumers live in the community with their parents or other relatives, in their own houses or apartments, or in residential facilities or group homes designed to meet their needs. Less than 1 percent of DDS consumers live in state–operated institutions known as DCs, discussed below.

DCs Program. The DDS operates three 24–hour facilities known as DCs—Fairview DC in Orange County, Porterville DC in Tulare County, and Sonoma DC in Sonoma County—and one smaller leased community facility (Canyon Springs in Riverside County). Together, these facilities provide care and supervision to approximately 1,100 consumers in 2014–15. Each DC is licensed by the Department of Public Health (DPH), and certified by DPH on behalf of the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), as skilled nursing facilities (SNFs), intermediate care facilities for the developmentally disabled (ICF–DDs), and general acute care hospitals.

The DCs are licensed and certified to provide a broad array of services based on each resident’s IPP, such as nursing services, assistance with activities of daily living, specialized rehabilitative services, individualized dietary services, and vocational or other day programs outside of the residential unit. The DCs must be certified in order to receive federal Medicaid funding, and the vast majority of DC residents are enrolled in Medi–Cal. Generally, for Medi–Cal enrollees living in DCs, the state bears roughly half the costs of their care and the federal government bears the remainder. Over the past 15 years, oversight entities such as DPH, CMS, and the United States Department of Justice have repeatedly identified problems at the DCs, including inadequate care, insufficient staffing, and inadequate reporting and investigation of instances of abuse and neglect. For more background on the history of problems identified at DCs, please refer to the “Department of Developmental Services” analysis in The 2013–14 Budget: Analysis of the Health and Human Services Budget.

Overall Budget Proposal. The budget proposes $5.7 billion (all funds) for DDS in 2015–16, which is a 4.5 percent net increase over estimated expenditures in 2014–15. General Fund expenditures for 2015–16 are proposed at $3.3 billion, a net increase of $201 million, or 6.5 percent, over estimated expenditures in 2014–15. This net increase in total expenditures generally reflects year–over–year increases in the budget for the Community Services Program, partially offset by decreasing costs in the DCs program budget.

2014–15 Adjustments Require Supplemental Appropriation. The revised 2014–15 DDS budget includes a number of adjustments that require a supplemental appropriation of $128 million General Fund ($102 million for the Community Services Program and $26 million for the DCs program), described further below.

2014–15 Adjustments. The revised 2014–15 budget for the Community Services Program includes several adjustments, requiring a supplemental appropriation of $102 million General Fund above the 2014–15 enacted budget appropriation to cover the following costs:

- Caseload Growth and Greater Utilization of Services. Increase of $111 million ($56 million General Fund) because of caseload growth and greater utilization of specialized adult residential facilities and supported living services.

- Unrealized Savings From Transferring Behavioral Health Treatment (BHT) Costs to Private Health Insurance. Increase of $44 million General Fund because of unrealized savings related to the transfer of BHT costs from RCs to private health insurance for individuals with autism who have private health insurance coverage. Chapter 650, Statutes of 2011 (SB 946, Steinberg), required private health insurance companies to provide BHT coverage to individuals with autism beginning July 1, 2012.

- New Federal Labor Regulations Assumed to Be Effective. Increase of $3.7 million ($1.9 million General Fund) to reflect an updated cost estimate for complying with new federal labor regulations originally set to take effect on January 1, 2015. Please refer to the “Federal Court Blocks New Federal Labor Regulations, Impacting IHSS and DDS” analysis earlier in this report for more detail on, and our analysis of, this issue.

We have reviewed these cost increases but are withholding our recommendation on this proposal, pending further information from the department on its estimated cost increase associated with greater utilization of services. We address this issue in greater detail later in this section.

2015–16 Community Services Program Budget. The budget proposes $5.1 billion (all funds) for the Community Services Program in 2015–16, which is a 6 percent net increase over estimated expenditures in 2014–15. Of this total, $615 million is proposed for RC operations expenditures and the remainder of $4.5 billion is for the purchase of services from RC vendors. General Fund expenditures are proposed at $3 billion, a net increase of $231 million, or 8.3 percent, above the estimated expenditures in 2014–15. This net increase reflects the following year–over–year budget changes.

- Caseload Growth and Greater Utilization of Services. Increase of $198 million ($181 million General Fund) because of caseload growth and greater utilization of specialized adult residential facilities and supported living services. We analyze these two components of the Governor’s proposal—caseload growth and greater utilization of services—later in this section.

- State–Mandated Hourly Minimum Wage Increase From $9 to $10. Increase of $64 million ($37 million General Fund) primarily for increasing the rates paid to certain RC vendors that employ workers currently earning less than $10 per hour. Chapter 351, Statutes of 2013 (AB 10, Alejo), will increase the state–mandated hourly minimum wage from $9 to $10 beginning January 1, 2016. We analyze this component of the Governor’s proposal later in this section.

- Paid Sick Days for Employees of RC Vendors. Increase of $25 million ($16 million General Fund) to provide funding to vendors that do not currently provide paid sick leave to their employees. Chapter 317, Statutes of 2014 (AB 1522, Gonzalez), requires employers to provide at least 24 hours (or three days) of sick leave per year to an employee. We analyze this component of the Governor’s proposal later in this section.

- One–Time Adjustment to RC Purchase of Services (POS) Budget. Decrease of $13 million General Fund to adjust the 2015–16 budget to account for a one–time augmentation of $13 million General Fund in 2014–15—used to implement recommendations from the Task Force on the Future of DCs.

- Annualizing Cost of New Federal Labor Regulations Assumed Effective. Increase of $21 million ($11 million General Fund) to annualize the cost of complying with new federal labor regulations originally set to take effect on January 1, 2015. Please refer to the “Federal Court Blocks New Federal Labor Regulations, Impacting IHSS and DDS” analysis earlier in this report for more detail on, and our analysis of, this issue.

2014–15 Adjustments for DCs Program Budget. The revised 2014–15 budget for the DCs program includes several adjustments, requiring a supplemental appropriation of $26 million General Fund above the 2014–15 enacted budget appropriation to cover the following costs:

- Expanding Capacity at Porterville DC for Incompetent to Stand Trial (IST) Admissions. Increase of $9 million General Fund to expand capacity within the secure treatment program (STP) of Porterville DC to accommodate an additional 32 beds for IST admissions. We note that a similar proposal to expand capacity for IST admissions is included in the budget for the Department of State Hospitals. Please refer to the “Department of State Hospitals” analysis in The 2015–16 Budget: Analysis of the Health Budget for more detail on, and our analysis of, this related proposal.

- Backfilling Withdrawn Federal Funding at Sonoma DC. Increase of $8.8 million General Fund is requested to backfill withdrawn federal funding for four ICF–DD residential units at Sonoma DC. The budget assumes federal funding for the four residential units will be restored no later than February 18, 2015.

- Implementation of Program Improvement Plans (PIPs) for Fairview and Porterville DCs. Increase of $12 million ($7.5 million General Fund) to fund ongoing improvements needed at Fairview and Porterville DCs in order to meet federal certification requirements for ICF–DD residential units.

We have reviewed these cost increases and find the supplemental appropriation request related to the DCs program to be reasonable.

2015–16 DCs Program Budget. The budget proposes $515 million (all funds) for the DCs program in 2015–16, which is an 8.5 percent net decrease below estimated expenditures in 2014–15. General Fund expenditures for 2015–16 are proposed at $280 million, a net decrease of $30 million, or 9.6 percent, below estimated expenditures in 2014–15. The major factors explaining the net decrease are:

- Completion of Lanterman DC Closure. Net decrease of $46 million ($24 million General Fund) related to the closure of Lanterman DC. The net decrease takes into account costs related to settling workers’ compensation claims and ensuring the successful transition of DC residents to the community, which are more than offset by savings from eliminating staff positions. The last resident transitioned to the community from Lanterman DC in December 2014. The budget proposes to transfer the Lanterman DC property to the California State University as of July 1, 2015.

- Annualizing Cost of Expanding Capacity at Porterville DC for IST Admissions. Increase of $9 million General Fund to annualize the cost of expanding capacity within the STP of Porterville DC to accommodate an additional 32 beds for IST admissions. We analyze this component of the Governor’s proposal later in this section.

- Staffing Reductions Due to Decreased DC Resident Population. Decrease of $12 million ($6.6 million General Fund) because of staffing reductions as the population of DCs declines (these staffing reductions exclude Lanterman DC, which is discussed separately above).

- Replacement of the Sonoma Creek Pump Station Intake System for Sonoma DC. Increase of $1.6 million General Fund to begin work related to replacing the pump station intake system at Sonoma Creek in order to ensure availability of the local water supply for Sonoma DC residents and staff. (Completing the replacement will cost an additional $2 million General Fund in 2017–18.)

Deferred Maintenance for DCs, Including Capital Outlay at Porterville DC. An increase of $7 million General Fund is budgeted separately from the department’s DC program budget for deferred maintenance projects within the DCs. Approximately $800,000 of these funds is proposed to conduct preliminary work related to a new fire alarm system at Porterville DC. (To complete the project will cost an additional $7.2 million General Fund over several years.) At the time of this analysis, the DDS is preparing a list of high–priority deferred maintenance issues to be addressed using the balance of the $7 million General Fund. Please refer to The 2015–16 Budget: The Governor’s General Fund Deferred Maintenance Proposal for more detail on, and our analysis of, the Governor’s deferred maintenance proposal.