Proposition 2 Changes How State Pays Debt and Builds Reserves. Proposition 2—approved by the voters in November 2014—places formulas into the State Constitution that determine the minimum amount of debt payments and budget reserve deposits to be made in a fiscal year. Because the estimates required by Proposition 2 are uncertain, the state’s elected leaders face key choices that will ultimately determine the amount of Proposition 2’s budget reserve and debt payment requirements.

Administration Estimates $2.4 Billion Proposition 2 Requirement. Under the administration’s January 2015 estimates, Proposition 2 requires that $2.4 billion be split between Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) deposits and debt payments in 2015–16. This amount is $1.5 billion lower than in our office’s November 2014 Fiscal Outlook due to our then–higher estimates of capital gains and complex interactions with Proposition 98, the state’s minimum funding guarantee for schools and community colleges.

Proposed Reserve of $3.4 Billion Marks Progress. Proposition 2’s required BSA deposits make up a sizeable portion of the state’s total proposed budget reserve for 2015–16. The $3.4 billion of total reserves proposed in the Governor’s budget would be helpful but insufficient to address a budget shortfall under many hypothetical economic slowdowns.

Administration Pays Down More Debt Than Required by Proposition 2. The administration meets Proposition 2 debt payment requirements in 2015–16 by paying down $965 million in special fund loans and $256 million in Proposition 98 settle up. In addition, we think there is a strong argument that the Legislature could count scheduled repayments of certain transportation loans—totaling $186 million in 2015–16—toward meeting Proposition 2 requirements. Under the administration’s January 2015 estimates, such an approach would allow the Legislature to reduce other proposed Proposition 2 debt payments by $186 million, freeing up a like amount of General Fund resources for other priorities. Moreover, should Proposition 2 requirements increase under the May Revision, this approach would help the Legislature meet those increased requirements.

Overall Budget Condition More Difficult to Forecast. Proposition 2 increases the complexity of an already complex budgetary system. Estimates necessary to calculate Proposition 2 requirements in 2015–16 involve at best educated guesses and thereafter are impossible to produce with any precision. With such a large amount of incremental gains in General Fund revenues allocated to reserves and debt under Proposition 2 and schools and community colleges under Proposition 98—itself an unpredictable formula—the Legislature may find that multiyear budget forecasting, now a constitutional requirement for the administration under Proposition 2, is much less useful than it has been in the past.

Proposition 2 places formulas into the State Constitution that determine the minimum amount of debt payments and budget reserve deposits to be made in a fiscal year. Most of the fiscal calculations required by Proposition 2 are dependent on estimates that the measure requires the Legislature to include in the annual budget act. Some of these estimates are uncertain when the Legislature adopts the budget package. In particular, Proposition 2’s requirements depend greatly upon estimates of capital gains taxes—a variable that is largely unknown for two years after the Legislature passes the budget for a fiscal year. This uncertainty is compounded by interactions with other budgetary estimates, principally those related to the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for schools and community colleges. Given these uncertainties, the state’s elected leaders face key choices in administering the measure that will ultimately determine the amount of Proposition 2’s budget reserve and debt payment requirements. This publication analyzes the administration’s Proposition 2 proposal outlined in the 2015–16 Governor’s Budget. The administration’s Proposition 2, Proposition 98, and other budget estimates and calculations will change in May 2015, as will our office’s estimates.

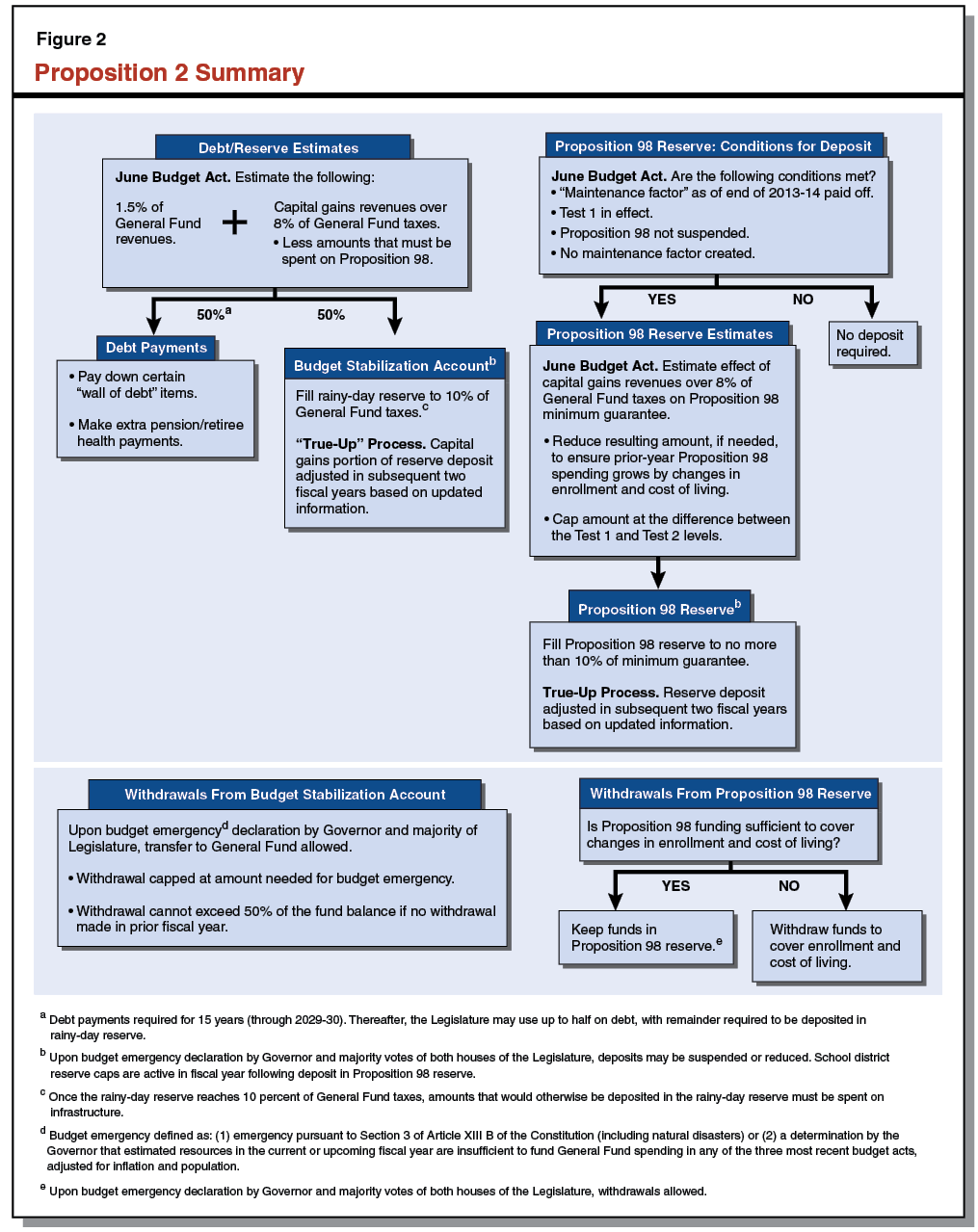

Proposition 2 Approved by Voters in 2014. Proposition 2 changes the way that the state pays down debts and saves money in reserves. Figure 1 displays the key changes made by Proposition 2, while the flowchart in Figure 2 shows how the new reserve and debt rules will affect state budget calculations.

Figure 1

Key Changes Made By Proposition 2

|

State Debts

|

|

Requires state to spend minimum amount each year to pay down specified debts.a

|

|

State Reserves

|

|

Changes amount of annual Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) deposit.a

|

|

Increases maximum size of the BSA.

|

|

Changes rules for when the state can reduce or suspend the BSA deposit.

|

|

Changes rules for withdrawing funds from the BSA.

|

|

School Reserves

|

|

Creates state reserve for schools and community colleges, the Public School System Stabilization Account (PSSSA).

|

|

Sets maximum reserves that school districts can keep in a year following a deposit into the PSSSA.b

|

Requires Amounts Be Spent on Reserves and Debt. As shown in the left column of the flowchart, Proposition 2 captures a base amount of 1.5 percent of General Fund revenues plus a portion of capital gains taxes that exceed 8 percent of all General Fund taxes. In this publication, we refer to this as the 8 percent threshold. (The estimate of all General Fund taxes is an alternate measure of General Fund revenues that excludes fees and penalties.) The resulting amount must be split between (1) debt payments and (2) reserve deposits into the BSA. Half of the capital gains portion of the Proposition 2 estimate—that concerning BSA deposits—will be “trued up” in the subsequent two budget acts.

Debts Eligible for Proposition 2 Funds. As shown in Figure 3, Proposition 2 specifies four debts eligible for payments under the measure—three types of budgetary liabilities and unfunded retirement liabilities generally. We provide more detail about these liabilities in the box below. (We note that the annual state budget pays down several billion dollars of liabilities outside of Proposition 2 requirements.)

Figure 3

Debts Eligible for Proposition 2 Debt Payment Fundsa

(In Billions)

|

Type of Debt

|

Amount

|

|

Budgetary Liabilities

|

|

|

Special fund loans to the General Fund

|

$5.3b

|

|

Proposition 98 settle up

|

1.5

|

|

Pre–2004 mandate reimbursements owed to cities, counties, and special districts

|

0.3c

|

|

Unfunded Retirement Liabilitiesd

|

|

|

State and CSU retiree health benefits

|

$71.8

|

|

CalPERS pensions for state and CSU employees

|

49.9

|

|

CalSTRS pensions

|

19.9

|

|

UC retiree health benefits

|

14.0

|

|

UC pensions

|

12.1

|

|

Judges’ Retirement System I pensions

|

3.3

|

|

CalPERS quarterly payment deferral

|

0.5

|

|

Judges’ Retirement System II pensions

|

0.0e

|

Proposition 2 requires half of the amount captured by its formula for the upcoming fiscal year be used to pay down specified debts.

Prior–Year Proposition 98 Obligations. When the actual Proposition 98 minimum guarantee turns out to be larger than the amount that was initially included in the budget, the state later addresses this funding shortfall—referred to as a settle–up obligation. Proposition 2 allows debt payments to be used for Proposition 98 settle up existing as of July 1, 2014.

Budgetary Loans. Proposition 2 authorizes debt payment funds to be used to pay down “budgetary loans to the General Fund, from funds outside the General Fund, that had outstanding balances on January 1, 2014.” The administration produces an official report of budgetary loans to the General Fund twice per year. The January 2015 edition lists $3.5 billion of outstanding loans as of December 31, 2014. (We include $3 billion of these loans in Figure 3 because the administration plans to pay down $457 million of special fund loans during the second half of 2014–15.)

In addition to the administration’s display, we include $2.3 billion in transportation loans in Figure 3. This total includes (1) $1.3 billion in loans of transportation weight fees, (2) $879 million owed from a loan from the Transportation Congestion Relief Fund (TCRF); and (3) the final repayment of $83 million of funds used for General Fund relief rather than transferred to the Transportation Improvement Fund (TIF). In 2000, the Legislature established the TCRF to receive General Fund revenues (one–time) and the TIF to temporarily receive ongoing revenues from the sales tax of gasoline transferred from the General Fund. In March 2002, voters approved Proposition 42, which permanently extended the transfer of gasoline sales tax revenue to the TIF. The Legislature suspended these required transfers to the TIF in certain years.

We include these additional transactions in Figure 3 (see page 7) because we think there is a strong argument that the Legislature could count them toward meeting Proposition 2’s debt payment requirements. Proposition 1A (2006) required that the suspensions of the TIF transfers required in Proposition 42 be treated as loans to the General Fund. In addition, both the weight fee loans and the TCRF loan have been listed in prior versions of the administration’s report of outstanding loans.

Pre–2004 Mandates. Proposition 2 also allows debt payment amounts to be used to pay down pre–2004 mandate reimbursements owed to cities, counties, and special districts. While the state owes $800 million of such reimbursements, we list less than $300 million of these liabilities in Figure 3 because—under the administration’s January estimates—the mandates “trigger” included in the 2014–15 spending plan pays down $533 million. Proposition 2 excludes reimbursements incurred after 2004, which now total $1.1 billion. In addition, by referencing a section of the State Constitution that addresses reimbursements to cities, counties, and special districts only, the measure implicitly excludes K–12 and community college mandates from being eligible for Proposition 2 debt payment funds ($4.2 billion as of the end of 2014–15).

Unfunded Retirement Liabilities. The measure allows debt payment funds to be spent on unfunded liabilities for “state–level” pension and retiree health liabilities. Payments toward these retirement liabilities must be in excess of amounts scheduled under law. In other words, the spirit of the measure is to encourage accelerated payments on pension and retiree health liabilities.

Budget Emergency Required to Reduce Deposit or Make Withdrawal. Under Proposition 2, the amount of a BSA deposit may be reduced only upon a budget emergency declaration by the Governor and majority votes of both houses of the Legislature. (Debt payments are required through 2029–30 and may not be reduced in a budget emergency during this period.) A budget emergency is allowed under the measure when estimated resources in the current or upcoming fiscal year are insufficient to fund General Fund spending in any of the last three enacted budgets, adjusted for inflation and population. (We refer to this as the budget emergency fiscal calculation.) A budget emergency may also be declared in response to a natural disaster. A budget emergency is also necessary to make a withdrawal from the Proposition 2 BSA, but the amount of a withdrawal is capped at the lesser of (1) the amount needed to maintain General Fund spending at the highest level of the past three enacted budget acts and (2) 50 percent of the BSA balance.

Creates State Reserve for Schools and Community Colleges. Proposition 98 requires the state to provide a minimum amount of funding for schools and community colleges. The right hand column of the flowchart in Figure 2 displays the process for making deposits into and withdrawals from the Proposition 98 reserve. As shown in the flowchart, a few conditions would need to be met in order for a deposit to be made into the Proposition 98 reserve. Because we do not anticipate these conditions to be met in the very near term, we do not focus on the Proposition 98 reserve in this publication. (For more information, see our February 2015 publication, The 2015–16 Budget: Proposition 98 Education Analysis, and our January 2015 publication, Analysis of School District Reserves.)

Figure 4 displays the administration’s January 2015 multiyear projection of Proposition 2 requirements. Below, we explain the administration’s Proposition 2 proposal for 2015–16 and then compare its estimates with those of our November 2014 Fiscal Outlook.

Figure 4

Summary of Administration’s Proposition 2 Estimates as of January 2015

General Fund (In Millions)

|

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

2018–19

|

|

Base amount

|

$1,719

|

$1,782

|

$1,864

|

$1,888

|

|

Excess capital gains taxes captured by Proposition 2

|

721

|

378

|

404

|

202

|

|

Totals, Proposition 2 Requirement

|

$2,440

|

$2,160

|

$2,268

|

$2,090

|

|

Deposit into Budget Stabilization Account

|

$1,220

|

$1,080

|

$1,134

|

$1,045

|

|

Debt paymentsa

|

1,220

|

1,080

|

1,134

|

1,045

|

$2.4 Billion Proposition 2 Requirement. Two components determine the total amount of revenue captured by Proposition 2. First, the base amount is equal to 1.5 percent of General Fund revenues and transfers. In 2015–16, the administration estimates this amount to be $1.7 billion. The base amount captured by Proposition 2 is relatively predictable and should not fluctuate much between now and the May Revision. In addition, the formula captures a portion of capital gains taxes exceeding the 8 percent threshold. Figure 5 shows the administration’s capital gains tax estimates for 2015–16 in more detail. As shown in the figure, the administration estimates that $721 million in so–called excess capital gains taxes will be captured by Proposition 2 in 2015–16. The sum of these two components is a $2.4 billion Proposition 2 requirement, split between BSA deposits and debt payments.

Figure 5

Administration’s Proposition 2 Capital Gains Tax Estimates

General Fund (In Millions)

|

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

2018–19

|

|

Total taxes from capital gains

|

$10,577

|

$10,235

|

$10,598

|

$10,403

|

|

Less amount equal to 8 percent of all General Fund taxes

|

–9,131

|

–9,490

|

–9,909

|

–10,007

|

|

Subtotals, Capital Gains Taxes Over 8 percent Threshold

|

($1,446)

|

($745)

|

($689)

|

($396)

|

|

Less Proposition 98 share

|

–$725

|

–$367

|

–$285

|

–$194

|

|

Totals, Excess Capital Gains Taxes Captured by Proposition 2

|

$721

|

$378

|

$404

|

$202

|

$1.2 Billion BSA Deposit Results in Total Reserves of $3.4 Billion at End of 2015–16. Under the administration’s estimates, $1.2 billion would be deposited in the BSA in 2015–16. Combined with the $1.6 billion BSA deposit made in the 2014–15 budget package, the BSA would end 2015–16 with a $2.8 billion balance. Along with a $534 million projected year–end balance in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties—the state’s traditional budget reserve—the Governor’s budget proposes total reserves of $3.4 billion.

Proposes $1.2 Billion for Special Fund Loans, Proposition 98 “Settle Up.” Figure 6 displays the administration’s multiyear plan for using Proposition 2 debt payment monies. As shown in the figure, the administration proposes to pay down all remaining special fund loans and Proposition 98 settle up by the end of 2018–19. We note that the administration proposes to pay around $60 million more in these debts over the four fiscal years combined than is required under their Proposition 2 estimates. In addition, the administration does not count several hundred million dollars in transportation loan repayments over the same period that arguably could count toward meeting Proposition 2’s debt payment requirements.

Figure 6

Administration Proposes to Pay Special Fund and Proposition 98 Debtsa

|

|

2015–16

|

2016–17

|

2017–18

|

2018–19

|

Amount Remaining After 2018–19

|

|

Special fund loan repayments

|

$965

|

$1,123

|

$694

|

$246

|

—

|

|

Proposition 98 “settle up”

|

256

|

—

|

445

|

811

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$1,221

|

$1,123

|

$1,139

|

$1,057

|

—

|

LAO Proposition 2 Estimate $1.5 Billion Higher Than Administration’s. Our office’s most recent revenue forecast was in the November 2014 Fiscal Outlook. (We will release updated estimates in May.) Figure 7 compares the administration’s January Proposition 2 estimates for 2015–16 with our office’s “main scenario” estimates from November 2014 for the same fiscal year. (Our main scenario assumes continuing, moderate economic growth through 2020, similar to the administration’s January 2015 forecast.) As shown in the figure, our office estimated that total Proposition 2 requirements would be $1.5 billion greater than the administration’s January estimate, resulting in a $754 million larger deposit into the BSA and $754 million more in required debt payments.

Figure 7

Comparing LAO and Administration Proposition 2 Estimates

(In Millions)

|

|

2015–16

|

Difference

|

|

LAO Nov. 2014 (Main Scenario)

|

Jan. 2015 Governor’s Budget

|

|

Base amount

|

$1,701

|

$1,719

|

–$18

|

|

Excess capital gains taxes captured by Proposition 2

|

2,248

|

$721

|

1,527

|

|

Totals

|

$3,949

|

$2,440

|

$1,509

|

|

Deposit into Budget Stabilization Account

|

$1,974

|

$1,220

|

$754

|

|

Debt payments

|

1,974

|

1,220

|

754

|

Difference Due to Capital Gains Estimates, Interactions With Proposition 98. Figure 8 displays the difference between the administration’s estimate of excess capital gains for 2015–16 and our office’s November 2014 main scenario estimate for the same fiscal year. Of the $1.5 billion difference, $947 million is due to our higher estimates of capital gains over the 8 percent threshold. The remaining difference ($580 million) is due to the calculation of Proposition 98 spending related to the excess capital gains revenue. (This hypothetical amount is calculated for Proposition 2 purposes only. It has no effect on the amount schools and community colleges will actually receive under Proposition 98.)

Figure 8

Comparing LAO and Administration Estimates of Excess Capital Gains Taxes

(In Millions)

|

|

2015–16

|

Difference

|

|

LAO Nov. 2014 (Main Scenario)

|

Jan. 2015 Governor’s Budget

|

|

Total taxes from capital gains

|

$11,450

|

$10,577

|

$873

|

|

Less amount equal to 8 percent of General Fund proceeds of taxes

|

–9,056

|

–9,131

|

75

|

|

Subtotals, Capital Gains Taxes Over 8 Percent Threshold

|

($2,393)

|

($1,446)

|

($947)

|

|

Less Proposition 98 Share

|

–$145

|

–$725

|

$580

|

|

Totals, Excess Capital Gains Taxes Captured by Proposition 2

|

$2,248

|

$721

|

$1,527

|

Legislative Role in Implementing Proposition 2. Figure 9 displays choices that the state faces in implementing Proposition 2’s rules and calculations. Where possible, we have indicated the decisions made by the administration in producing the Governor’s budget. We make no recommendations concerning these issues at this time, but note that the Legislature has choices in implementing Proposition 2, either directly or indirectly through negotiations with the Governor. (We described most of these issues in Chapter 4 of our November 2014 Fiscal Outlook publication.)

Figure 9

Key Choices for the State Related to Proposition 2 Implementation in 2015–16

|

Choice for State’s Policymakers

|

Choice Reflected in Governor’s budget

|

|

Pre–Proposition 2 Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) Deposits

|

|

|

Apply Proposition 2’s new withdrawal rules to $1.6 billion deposited in BSA prior to Proposition 2?

|

The administration seems to regard the pre–Proposition 2 deposit as subject to the new Proposition 2 withdrawal rules.

|

|

Capital Gains Calculations

|

|

|

Apply Proposition 98 Test 3 supplement in Proposition 2 calculations?

|

Issue is not a factor currently in administration’s Proposition 2 calculation. Applying the supplement contributes to higher LAO estimates of Proposition 2 requirements.

|

|

Use average or marginal tax rates in capital gains calculations?

|

Average. Results in lower BSA/debt payment requirements than using marginal rates.

|

|

Use administration method for attributing capital gains taxes to fiscal years?

|

Yes. Different assumptions would produce different Proposition 2 results.

|

|

Assume that a portion of capital gains taxes in upcoming fiscal year will match long–term historical averages as a share of state’s economy?

|

Yes. Administration assumption may result in under—appropriation of debt payments over the long term.

|

|

Estimate that capital gains taxes are over the 8 percent threshold?

|

Yes. Administration estimates that capital gains taxes will equal 9.3 percent of General Fund taxes.

|

|

Debt Payments

|

|

|

Count repayment of transportation loans as meeting certain Proposition 2 debt payment requirements?

|

No. Counting these loan repayments (and reducing other Proposition 2 debt payments by a like amount) would free up $186 million General Fund in the 2015–16 budget (administration’s January 2015 estimates).

|

|

Budget Emergency

|

|

|

Declare budget emergency due to fiscal calculation or natural disaster, such as drought or fire?

|

No. If Governor chooses to declare a budget emergency, the Legislature could pass a bill to suspend or reduce BSA deposit for 2015–16.

|

Degree of Legislative Control Over $1.6 Billion Deposited in BSA Prior to Proposition 2. As we discussed in our November 2014 Fiscal Outlook, there is a strong argument that the Legislature could appropriate the $1.6 billion of pre–Proposition 2 BSA balances at any time, whereas the Governor would have to declare a budget emergency before the Legislature could access BSA funds deposited after passage of Proposition 2. The maximum amount that the Legislature can withdraw from the Proposition 2 BSA is 50 percent of the balance in the first fiscal year of a budget emergency. If a future downturn results in a larger shortfall in the first year of a budget emergency, the 50 percent limitation may mean that the Legislature could have to cut spending, increase taxes, or adopt other actions despite the availability of other BSA funds. If this scenario were to arise, flexibility concerning the $1.6 billion deposited before Proposition 2 could help in addressing such a budget problem.

Budget Emergency Seems Unavailable Under Fiscal Calculation. Proposition 2 does not require that the administration produce a budget emergency calculation as a part of the budget process. Presumably, the administration would only produce such a calculation when declaring a budget emergency. Nevertheless, we think it instructive to attempt to produce such a calculation using data from the administration’s multiyear budget and economic forecast. We display our version of this calculation in Figure 10.

Figure 10

Budget Emergency in 2015–16 Seems Unavailable Under Administration Estimatesa

(In Millions)

|

2014–15 Calculation

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Adjusted budget for fiscal yearb

|

$95,978

|

$98,448

|

$107,987

|

|

Resources available for 2014–15c

|

112,171

|

112,171

|

112,171

|

|

Adjusted budget greater than resources available?a

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Reduced resources necessary for availability of budget emergency

|

16,193

|

13,723

|

4,184

|

|

2015–16 Calculation

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

2014–15

|

|

Adjusted budgetb

|

$98,861

|

$101,405

|

$111,230

|

|

Resources available for 2015–16c

|

113,832

|

113,832

|

113,832

|

|

Adjusted budget greater than resources available?a

|

No

|

No

|

No

|

|

Reduced resources necessary for availability of budget emergency

|

14,971

|

12,427

|

2,602

|

As shown in the figure, a Proposition 2 budget emergency—under the measure’s fiscal calculation—seems unlikely under the administration’s January 2015 estimates. (We note that a budget emergency—allowing the BSA deposit to be reduced or eliminated—would be available in virtually any year based on the existence of a natural disaster, such as a fire or drought.) Estimated resources for 2015–16 would have to be $2.6 billion lower in order for a budget emergency to be available under the Proposition 2 fiscal calculation. Absent a significant drop in the stock market or other event affecting the national or global economy between now and June 2015, a decline in resources available of this magnitude seems unlikely.

Recommend Long–Term Debt Plan. In our November 2014 Fiscal Outlook, we suggested that the Legislature solicit proposals from the administration, state pension systems—including CalPERS, CalSTRS, and the UC Regents—and others concerning the benefits of applying Proposition 2 debt payment funds to the retirement and budgetary liabilities listed earlier in Figure 3. While developing a long–term plan for Proposition 2, the Legislature could begin to pay down budgetary liabilities related to local governments and special funds in 2015–16, as well as begin to address the relatively small $3.3 billion unfunded liability for the Judges’ Retirement System I.

Administration Pays Down More Debt Than Required in 2015–16. As described earlier, the administration calculates that Proposition 2 requires $1.2 billion in debt payments be made in 2015–16. The administration meets this requirement by paying down $965 million in special fund loans and $256 million in Proposition 98 settle up. In addition, the Governor’s budget assumes that $102 million in loans to the General Fund from transportation weight fees are repaid in 2015–16, along with the final $83 million payment to the Transportation Improvement Fund under Proposition 1A. As described earlier, we think a strong argument exists to count these payments toward Proposition 2. If the Legislature counted these transactions as meeting Proposition 2 debt payment requirements, it could reduce other Proposition 2 debt payments by $186 million, freeing up a like amount of General Fund resources for other priorities. (We note that—depending on the administration’s May estimates—weight fee loan repayments may not be required until a future year.)

Administration Estimating Methods Could Affect Debt Payments. The administration’s January 2015 forecast assumes that—beginning in 2016—capital gains will match a long–term historical average as a share of the state’s economy. There is an argument that this approach underestimates likely 2015–16 capital gains taxes, given recently elevated stock prices. Debt payments are not required to be trued up under Proposition 2. Therefore, relying on a modest capital gains tax estimate in the 2015–16 budget will result in smaller Proposition 2 debt payment requirements over the next year than under other estimating methods. Given voters’ intent to pay down debts under Proposition 2, the Legislature may wish to consider whether such a modest estimate of capital gains taxes is desirable.

Suggest State Aim for $3.4 Billion or Larger Reserve. While the $3.4 billion reserve proposed in the Governor’s budget would be helpful, it would be insufficient to address many hypothetical budget shortfalls that could arise in the next few years. The hypothetical slowdown scenario in our November 2014 Fiscal Outlook illustrates how quickly the General Fund budget could return to a deficit. We have little reason to believe that such a slowdown will occur soon, but urge the Legislature to continue making progress in building reserves. Doing so would better protect the state against the inevitable future drop in revenues resulting from the state’s volatile revenue system.

For these reasons, a $3.4 billion or larger reserve would be ideal for the 2015–16 budget. We recognize, however, the challenges associated with surging revenues in 2014–15. As we discussed in a variety of recent publications, these revenue increases—holding other factors constant—will generally boost ongoing spending on Proposition 98 by a like amount. If 2015–16 revenues cannot support that spending without reductions in other areas of the budget—or if Proposition 2 or other factors constrain the budget further—it could be quite difficult for the Legislature to maintain a reserve of $3.4 billion.

Advise Against Reliance on Special Funds Borrowing. While proposing repayment of special fund loans in recent years, the Governor and other administration officials have suggested that the state could borrow from those funds again in the future when the state General Fund faces a shortfall. We regard these administration suggestions with some concern. Such an approach would result in problematic outcomes for individuals and businesses that pay fees into and receive services financed by these funds. If repaying special fund loans will result in billions of dollars in excess balances, we advise the Legislature to consider either increasing special fund spending or reducing fees to bring those accounts back toward an appropriate balance.

Proposition 2 Amounts Uncertain for 2015–16, Unpredictable Thereafter. In recent years, debates about General Fund revenues have centered around revenues from capital gains. As discussed by our office and the administration, revenues from capital gains are notoriously difficult to forecast due to the unpredictability of the stock market. To illustrate, the state will not have reliable data about capital gains realized in 2015 until May 2017. This means that Proposition 2 estimates for the 2015–16 fiscal year will be largely uncertain until the state makes its second true–up deposit in the 2017–18 budget. By that time, the Proposition 2 requirement would equal the BSA deposit and debt payment for 2017–18 plus true ups—or “true downs,” in the event budget estimates prove too high—for half of the excess capital gains taxes in both 2015–16 and 2016–17. True ups and true downs will introduce significant uncertainty to the budget process in the future.

Overall Budget Condition More Difficult to Forecast. Proposition 2 increases the complexity of an already complex budgetary system. Estimates necessary to calculate Proposition 2 requirements in 2015–16 involve at best educated guesses and thereafter are impossible to produce with any precision. In any fiscal year, Proposition 2 requirements could range between $1.5 billion to $4 billion or more. With such a large amount of incremental gains in General Fund revenues allocated to reserves and debt under Proposition 2 and schools and community colleges under Proposition 98—itself an unpredictable formula—the Legislature may find that multiyear budget forecasting, now a constitutional requirement for the administration under Proposition 2, is much less useful than it has been in the past.