Proposition 47, which was approved by voters in November 2014, makes significant changes to the state’s criminal justice system. Specifically, it reduces the penalties for certain non–violent, nonserious drug and property crimes and requires that the resulting state savings be spent on (1) mental health and substance use services, (2) truancy and dropout prevention, and (3) victim services. In this report, we describe the provisions of the measure and their effect on state corrections, state courts, and the county criminal justice system. We also describe and assess the Governor’s 2015–16 budget proposals related to Proposition 47. In addition, we recommend steps the Legislature can take to ensure that it has the necessary information to make important decisions regarding the implementation of Proposition 47. Finally, we provide recommendations on how the Legislature can ensure that the state savings from the proposition are spent in a manner that maximizes reductions in recidivism, truancy, and dropout–rates and improves victim services.

There are three types of crimes: felonies, misdemeanors, and infractions. A felony is the most serious type of crime. State law classifies some felonies as “violent” or “serious,” or both. Examples of felonies defined as both violent and serious include murder, robbery, and rape. Felonies that are not classified as violent or serious include grand theft and selling illegal drugs. A misdemeanor is a less serious crime. Misdemeanors include crimes such as petty theft and public drunkenness. An infraction is the least serious crime and is usually punished with a fine.

Felony Sentencing. In recent years, there has been an average of about 220,000 annual felony convictions in California. Prior to 2011, anyone convicted of a felony was eligible for state prison. In 2011, the state realigned to county governments the responsibility for certain felony offenders. Under this realignment, most offenders convicted of nonserious and non–violent felonies (specifically those with no prior convictions for violent, sex, or serious crimes) are generally ineligible to be sentenced to state prison and are instead sentenced to county jail and/or community supervision. Accordingly, offenders convicted of felonies can be sentenced as follows:

- State Prison. Felony offenders who have current or prior convictions for serious, violent, or sex crimes can be sentenced to state prison. Offenders who are released from prison after serving a sentence for a serious or violent crime are placed on parole where they are supervised in the community by state parole agents. Offenders who are released from prison after serving a sentence for a crime that is not a serious or violent crime are usually supervised in the community by county probation officers. Offenders who break the rules that they are required to follow while supervised in the community can be sent to county jail. However, they may be sent to state prison if they commit a new prison–eligible offense.

- County Jail and/or Community Supervision. Felony offenders who have no current or prior convictions for serious, violent, or sex offenses are typically sentenced to county jail and/or the supervision of a county probation officer in the community. In addition, depending on the discretion of the judge and what crime was committed, some offenders who have current or prior convictions for serious, violent, or sex offenses can receive similar sentences. Offenders who break the rules that they are required to follow while on community supervision can be sent to county jail. However, they may be sent to state prison if they commit a new prison–eligible offense.

Misdemeanor Sentencing. Under current law, offenders convicted of misdemeanors may be sentenced to county jail, county community supervision, a fine, or some combination of the three. Offenders on community supervision can be placed in jail if they break the rules that they are required to follow while supervised in the community. However, they may be sent to state prison if they commit a new prison–eligible offense. In general, offenders convicted of misdemeanor crimes are punished less severely than felony offenders. For example, misdemeanor crimes carry a maximum sentence of up to one year in jail while felony offenders can spend much longer periods in prison or jail. In addition, offenders who are convicted of a misdemeanor are usually not supervised as closely by probation officers.

Wobbler Sentencing. Some crimes—such as burglary of a commercial property—can be charged as either a felony or a misdemeanor. These crimes are known as “wobblers.” Courts decide how to charge wobbler crimes based on the details of the crime and the criminal history of the offender.

Proposition 47 reduced certain nonserious and non–violent property and drug offenses from wobblers or felonies to misdemeanors. The measure limits these reduced penalties to offenders who have not previously committed certain severe crimes listed in the measure—including murder and certain sex and gun crimes. Specifically, the measure reduces the penalties for the following crimes:

- Drug Possession. Under Proposition 47, possession for personal use of most illegal drugs (such as cocaine or heroin) is always a misdemeanor crime. Previously, such a crime was a misdemeanor, a wobbler, or a felony—depending on the amount and type of drug. The measure did not change the penalty for possession of marijuana, which is currently either an infraction or a misdemeanor.

- Receiving Stolen Property. Individuals found with stolen property may be charged with receiving stolen property. Proposition 47 changes receiving stolen property worth $950 or less from a wobbler crime to a misdemeanor.

- Theft. Proposition 47 limits when theft of property of $950 or less can be charged as a felony. Specifically, such crimes cannot be charged as felonies solely because of the type of property involved or because the defendant had previously committed certain theft–related crimes.

- Shoplifting. Under Proposition 47, shoplifting property worth $950 or less is always a misdemeanor and can no longer be charged as burglary in the second degree, which is a wobbler.

- Writing Bad Checks. Under Proposition 47, it is always a misdemeanor to write a bad check unless the check is worth more than $950 or the offender has previously committed three forgery related crimes, in which case the crime is a wobbler. Previously, writing a bad check was a wobbler crime if the check was worth more than $450, or if the offender had previously committed a crime related to forgery.

- Check Forgery. Proposition 47 makes forging a check worth $950 or less a misdemeanor, except that it is a wobbler crime if the offender commits identity theft in connection with forging a check. Previously, it was a wobbler crime to forge a check of any amount.

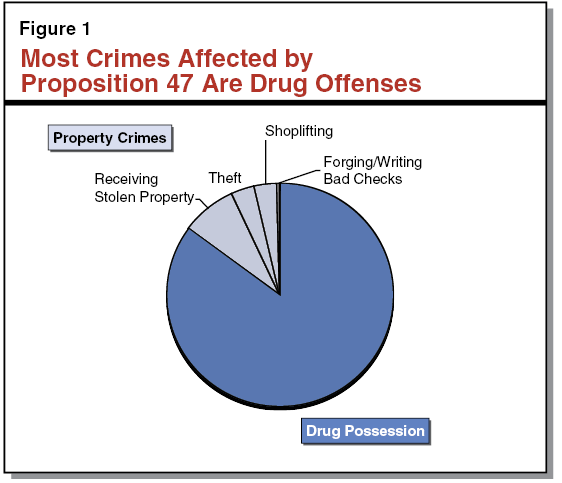

Based on 2012 data, we estimate that about 40,000 offenders annually are convicted of the above crimes and will be affected by the measure. However, this estimate is based on the limited available data, and the actual number could be thousands of offenders higher or lower. As shown in Figure 1, most of the affected crimes are drug offenses.

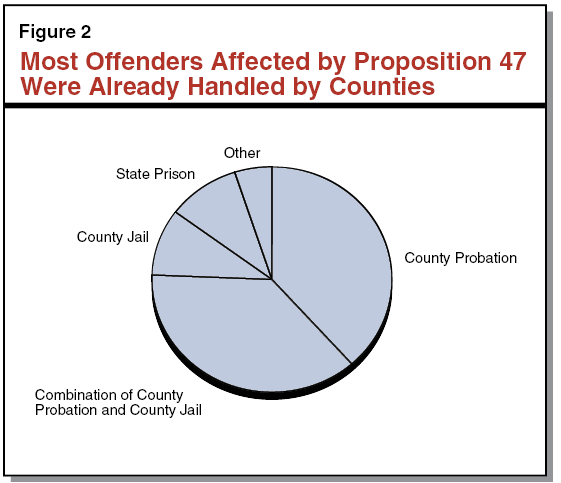

Change in Penalties for These Offenders. Since Proposition 47 designated crimes are nonserious and non–violent, most offenders have been handled at the county level since the 2011 realignment, as shown in Figure 2. Nearly nine out of every ten offenders who received felony convictions in 2012 for crimes affected by Proposition 47 were sentenced to county jail and/or county community supervision. Under Proposition 47, these offenders will continue to be handled locally. However, the length of sentences—jail time and/or community supervision—will typically be less. A relatively small portion—roughly one–tenth—of offenders of the above crimes are currently sent to state prison. Under this measure, none of these offenders will be sent to state prison. Instead, they will serve lesser sentences at the county level.

Proposition 47 allows offenders currently serving felony sentences for the above crimes to apply to have their felony sentences reduced to misdemeanor sentences. In addition, certain offenders who have already completed a sentence for a felony that the measure changes can apply to the court to have their felony conviction reclassified as a misdemeanor. However, no offender who has committed a specified severe crime can be resentenced or have their conviction reclassified. In addition, the measure states that a court is not required to resentence an offender currently serving a felony sentence if the court finds it likely that the offender will commit a specified severe crime. Offenders who are resentenced are required to be on state parole for one year, unless the judge chooses to remove that requirement.

The measure requires that the annual savings to the state from the measure, as estimated by the Department of Finance (DOF), be annually transferred from the General Fund into a new state fund, the Safe Neighborhoods and Schools Fund (SNSF), beginning in 2016–17. The amount will depend on DOF’s estimate of savings resulting from the measure in the prior fiscal year. For example, state savings from 2015–16 will be deposited into the fund for expenditure in 2016–17. (State savings in 2014–15 are not required to be deposited in the SNSF.) The measure also states that funds in the SNSF shall be continuously appropriated, which means that the funds can be spent without future legislative action. Under the measure, monies in the fund would be divided as follows:

- 65 percent to the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) for grants to public agencies aimed at supporting mental health treatment, substance abuse treatment, and diversion programs for people in the criminal justice system. The measure directs BSCC to prioritize programs that reduce recidivism of people convicted of less serious crimes (such as those covered by Proposition 47) and those who have substance abuse and mental health problems.

- 25 percent to the California Department of Education (CDE) for grants to public agencies aimed at improving outcomes for K–12 public school students by reducing truancy and supporting those students who are at risk of dropping out of school or are victims of crime.

- 10 percent to the Victim Compensation and Government Claims Board (VCGCB) to make grants to trauma recovery centers (TRCs) to provide services to victims of crime.

While Proposition 47 requires state savings to be spent for the above purposes, it does not specify what process shall be used by the administrative agencies to allocate the funding. For example, the measure does not generally specify what criteria the administering agencies shall use to identify grant recipients (such as a demonstration of need) or what requirements shall be placed on grant recipients (such as reporting on outcomes).

Impact on State Correctional Population. Proposition 47 makes two changes that will reduce the state prison population. First, the reduction of certain felonies and wobblers to misdemeanors will make fewer offenders eligible for state prison sentences. We estimate that this could result in an ongoing reduction to the state prison population of several thousand inmates within a few years. Second, the resentencing of inmates currently in state prison could result in the release of several thousand inmates, temporarily reducing the state prison population for a few years. The release of these inmates will also result in a slight increase in the state parole population of a couple thousand parolees over a three–year period.

Impact on Meeting Court–Ordered Population Cap. In recent years, the state has been under a federal court order to reduce overcrowding in the prisons operated by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). Specifically, the court found that prison overcrowding was the primary reason the state was unable to provide inmates with constitutionally adequate health care and ordered the state to initially reduce its prison population to 143 percent of design capacity by June 20, 2014. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds CDCR would operate if it housed only one inmate per cell and did not use temporary beds, such as housing inmates in gyms. Inmates housed in contract facilities or fire camps are not counted toward the overcrowding limit.) As shown in Figure 3, the federal court ordered the state to further reduce the prison population to 141.5 percent of design capacity by February 28, 2015 and to 137.5 percent of design capacity by February 28, 2016. The February 2016 cap represents the ongoing and final limit on the state’s prison population. (For more information regarding the federal court–ordered population cap, please see our report, The 2014–15 Budget: Administration’s Response to Prison Overcrowding Order.)

Figure 3

Federal Court–Ordered Prison Population Cap

|

|

Design Capacity of CDCR Prisons

|

Population Cap

(Percent of

Design Capacity)

|

Inmates Allowed in CDCR Prisons

|

|

June 30, 2014 through February 27, 2015

|

82,707

|

143%

|

118,271

|

|

February 28, 2015 through February 27, 2016

|

82,707

|

141.5

|

117,030

|

|

After February 27, 2016

|

85,082a

|

137.5

|

116,988

|

The court also appointed a compliance officer. If the prison population exceeds the population cap at any point in time, the compliance officer would be authorized to order the release of the number of inmates required to meet the cap. In order to ensure that such releases do not occur if the prison population increases unexpectedly, CDCR has intentionally reduced the prison population below the court–required cap by thousands of inmates. This gap between the number of inmates CDCR is allowed to house in its 34 prisons and the number it actually houses acts as a “buffer” against the population cap. Between June 2014 and November 2014, CDCR maintained an average buffer of about 2,000 inmates and at no point came within 1,000 inmates of the population cap. In recent months, the buffer has grown even larger as a result of a decline in the inmate population—primarily from Proposition 47. As of January 28, 2015, the inmate population in the state’s prisons was about 113,500, or 3,600 inmates below the February 2015 cap, and slightly below the final February 2016 cap. The expected impact of Proposition 47 on the prison population will make it easier for the state to remain below the population cap. As we discuss below, the Governor’s budget projects that the state will maintain compliance with the court–ordered population cap throughout 2015–16.

Reduces CDCR’s Budget by $12.7 Million Due to Proposition 47. The Governor’s budget assumes a reduction of 1,900 inmates and an increase of 900 parolees in 2015–16 due to the implementation of Proposition 47. The budget assumes this will result in a decline in the number of inmates housed in the state’s prisons. Accordingly, the budget assumes no reduction in the number of inmates housed in contract beds. For the most part, prison staffing levels remain fixed when the inmate population changes unless the change is significant enough to justify opening or closing housing units. Since the Governor’s budget does not propose closing specific housing units, the savings from the estimated reduction of 1,900 inmates is limited to minor staffing reductions and other variable costs (such as feeding and clothing costs). These savings amount to about $9,500 per inmate, for a total of $18 million in 2015–16. These savings are offset by a proposed $5.4 million augmentation for the projected increase in the parole population. In total, the budget proposes a net $12.7 million reduction to CDCR’s budget for 2015–16 to account for Proposition 47.

The administration is projecting that the prison population will decline by nearly 2,000 inmates from 2014–15 to 2015–16—resulting from Proposition 47 and various court–ordered population reduction measures. Due in part to this reduction, the Governor’s budget is projecting that the state will maintain compliance with the federal court–ordered population cap throughout 2015–16. However, the state’s ability to comply with the cap also depends on various factors that affect the amount of prison capacity available to the department. In particular, it will depend heavily on (1) the number of contract beds maintained by CDCR and (2) the design capacity of the state’s 34 prisons. The Governor’s budget for 2015–16 includes proposals that affect both of these factors.

Slight Increase in Contract Beds. The Governor’s budget includes $495 million in General Fund support to maintain about 15,900 contract beds in 2015–16. This represents a slight increase (about 4 percent) from the revised current–year funding level of $476 million for 15,400 contract beds. As mentioned above, inmates housed in contact beds are not counted towards the population cap.

Activation of New Infill Beds. The Governor’s budget also includes $36 million from the General Fund to activate three new infill bed facilities that are currently under construction—specifically, two new facilities at Mule Creek prison in Ione and one new facility at R.J. Donovan prison in San Diego. These facilities will add almost 2,400 beds to the design capacity of CDCR’s 34 prisons. Because the state will be allowed to overcrowd to 137.5 percent of design capacity, the activation of these facilities will allow the state to add about 3,300 inmates to its prison facilities. The budget assumes that all three facilities will be activated in February 2016. (A facility is considered to be activated when it admits its first inmate.)

According to the administration, there is significant uncertainty regarding a couple of key aspects of its compliance plan. In particular, the administration indicates that its inmate population projections and the timing of additional capacity from new infill facilities are subject to uncertainty. However, the administration states that its plan was developed to account for such uncertainties and to ensure compliance with the population cap regardless of how these factors unfold.

Population Projections Subject to Unusually High Degree of Uncertainty. According to the administration, a key source of uncertainty is the accuracy of the department’s population projections. In developing its annual budget request, CDCR estimates what its inmate population will be in the upcoming fiscal year. In past years, these projections—provided as part of the Governor’s January budget proposal and May Revision—have also included the department’s estimate of what the average annual inmate population will be in each of the four fiscal years following the budget year. The department’s population projections are always subject to some uncertainty because the prison population depends on several factors (such as crime rates and county sentencing practices) that are hard to predict. However, according to the administration, this year’s projections are particularly uncertain due to the additional challenge of estimating the effects of Proposition 47 and other court–ordered population reduction measures. Due in part to this, CDCR has decided not to publish its estimate of the inmate population beyond 2015–16.

Timing of Additional Capacity From New Prison Facilities Is Uncertain. According to the administration, another key source of uncertainty is the schedule for the activation of the three new infill bed facilities. The department plans to admit inmates into the facilities in waves beginning in February 2016 and expects to reach full occupancy by July 2016. However, the administration is uncertain whether the facilities will in fact begin accepting inmates as scheduled. In particular, the administration indicates that construction crews could encounter unanticipated difficulties (such as poor weather) that could result in delayed activation.

In addition, there is some uncertainty regarding how the federal court will count the additional infill capacity for the purpose of calculating the number of inmates the state can house in its 34 prisons. In a previous order, the court required the state to meet with the plaintiff’s attorneys and attempt to reach an agreement regarding how the court should count capacity added by new construction, such as the above infill facilities. According to the administration, these negotiations have not yet begun. The number of inmates that can be housed in the 34 prisons could vary significantly depending on the court’s decision. For example, if the court counts the entire design capacity of the facilities immediately upon activation—irrespective of the number of inmates actually housed there—the number of inmates that could be housed in the 34 prisons would increase by about 3,300 immediately. (This is the way the court previously treated additional capacity.) Alternatively, the court could determine that the facilities must be fully occupied before it counts the full design capacity. In that case, the court would likely count the inmates housed in the facilities during the activation phase the same way it counts inmates housed in contract facilities or fire camps. In other words, the state would only get credit for the number of inmates housed in the infill facilities rather than for the full 3,300 bed increase in design capacity. Such a decision would reduce the number of inmates that could be housed in the state’s prison by thousands of inmates in the months in which the facilities are being filled.

The Governor’s proposals raise a couple of concerns. Specifically, we find that the budget would provide more contract bed funding than necessary for CDCR. In addition, the Governor’s budget lacks long–term inmate population projections that are needed for the Legislature to begin planning how best to adjust the state’s prison capacity to account for the effects of Proposition 47. We discuss these concerns in greater detail below.

In order to deal with the uncertainty regarding the above factors, the Governor’s budget makes very cautious assumptions regarding (1) the number of contract beds needed to comply with the population cap and (2) the size of the population reductions resulting from Proposition 47. This approach provides more funding than necessary to CDCR. The precise amount of excess funding depends on whether the infill facilities are activated on time and how the court counts the new capacity. However, as we discuss below, our analysis indicates that the amount would reach at least $20 million under almost any scenario.

Proposed Number of Contract Beds Would Result in Excessive Buffer. Based on CDCR’s population projections, the administration is planning to maintain a buffer of several thousand inmates in 2015–16. It maintains this buffer by housing these inmates in contract beds rather than in the state’s 34 prisons. In other words, CDCR could move several thousand inmates from contract beds into the state’s prisons without violating the court’s order. According to the administration, the planned buffer is needed to account for the uncertainty regarding the timing of additional capacity from the new infill facilities. However, our analysis suggests that the state could achieve significant savings by maintaining a smaller buffer without meaningfully increasing the risk of violating the population cap. This is true regardless of whether the infill facilities are activated as scheduled or how the court counts the new capacity provided by the facilities.

For example, if the new facilities are activated as scheduled and the court counts the full capacity immediately, the state would have enough inmates in contract beds to maintain an average buffer of 4,300 inmates in 2015–16. Alternatively, if the court instead requires the facilities to be fully occupied before counting them towards the state’s design capacity, the state would still have enough inmates in contract beds to maintain an average of 3,700 inmates below the population cap. Maintaining the buffer at the level proposed by the department would come at a significant cost. This is because the department saves almost $18,500 annually by taking an inmate out of a contract bed and placing the inmate in one of the state’s prisons. If the department instead maintained a buffer in 2015–16 at a level similar to the average buffer over the first several months of 2014–15—about 2,500 beds—it could reduce its contract bed expenditures significantly. While the precise amount of savings would depend on how the court counts the additional infill capacity, we estimate it would reach at least $20 million under almost any scenario.

Operational Savings Could Offset Contract Bed Costs If Infill Delayed. If the activation of the infill facilities is delayed, we find that CDCR would still have excess funding under the Governor’s budget. This is because if the facilities are not activated on the timeline assumed in the budget, some or all of the proposed $36 million to support their activation would not be needed. For example, if the department determines that construction is running behind schedule, it could delay the hiring of the staff needed to operate the facilities. While some staff may be needed to prepare the facility for activation, the vast majority of staff (such as custody staff assigned to guard the housing units) would not be needed as long as there are no inmates in the facilities. While the operational savings would vary depending on the extent of the delays, the amount could easily reach into the tens of millions of dollars. A delay of the infill capacity would likely require the department to maintain contract beds at the level proposed by the administration during the last several months of 2015–16. Nevertheless, we note that CDCR could still reduce its use of contract beds somewhat over the first several months of the budget year. Moreover, the operational savings from the delayed activation of the infill facilities could be used to partly offset the cost of any additional contract beds needed.

Population Estimates Appear High. Our analysis indicates that the administration may be underestimating the population impacts of Proposition 47 and thus overestimating the inmate population for 2015–16. In other words, the administration is assuming a lesser reduction in the inmate population from Proposition 47 than will likely occur. If this turns out to be the case, the amount of excess contract bed funding we described above would be even greater. We acknowledge that it is difficult to predict the size of the effect of Proposition 47 on CDCR’s inmate population. This is because it depends on some key factors about which there is uncertainty, such as exactly how many offenders are currently in prison for offenses affected by the measure, which are described in more detail later in this report. Given such uncertainty, we find that the administration’s estimate of the impact of Proposition 47 on the prison population is not out of the realm of possibility. However, our analysis indicates that the administration made very cautious assumptions in a variety of areas that have the effect of minimizing its estimate. For example, the administration assumed that there would be no impact on the prison population from provisions in the measure that prevent shoplifting from being charged as a felony. The result is that CDCR’s estimate is on the low end of a range of what our analysis indicates could occur. In our view, there is a high likelihood that the actual population impacts will be greater than projected by the department.

In the long term, the Legislature may have a variety of options to achieve savings by reducing prison capacity as the inmate population declines as a result of Proposition 47, as well as population reduction measures ordered by the court. For example, the Legislature could consider permanently reducing the state’s use of contract beds or even closing a state prison. The appropriate course of action, and any necessary planning to achieve it, depends heavily on the estimated prison population in future years. As we discuss later, this decision could significantly affect the amount of state savings achieved from Proposition 47, and as a result, the size of the deposit to the SNSF. As such, it is impossible for the Legislature to make an informed decision regarding how to adjust the state’s prison funding and capacity without the long–term population projections that the department has declined to provide this year.

Withhold Action Pending Additional Justification. We find that the Legislature could reduce the Governor’s proposed contract bed funding level by at least $20 million by directing CDCR to move inmates from contract beds into state prisons. We note, however, that the amount of savings could exceed our preliminary estimate depending on (1) the timing of the activation of the infill beds, (2) how the court counts the infill capacity, and (3) how the actual inmate population level compares to the administration’s projections.

As such, we recommend that the Legislature not approve the proposed contract bed funding until the department can provide additional information demonstrating what level is necessary to meet the court–ordered population cap. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature direct the CDCR to report at budget hearings on (1) how the administration’s population projections for the current year compare with actual population levels, (2) whether the infill facilities are on track to be activated on schedule, and (3) the status of negotiations with plaintiffs related to how the court will count the additional capacity resulting from the activation of the infill facilities. Based on this information, the Legislature would be able to assess the amount of contract bed funding needed and adjust the budget for 2015–16 accordingly.

Direct CDCR to Provide Long–Term Population Projections. In addition, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to resume its historical practice of providing long–term population projections biannually. This information would allow the Legislature to better assess and plan for the long–term implications of Proposition 47, as well as court–ordered population reduction measures, and determine how best to adjust the state’s prison funding and capacity accordingly.

Resentencing and Reclassification Hearings Will Temporarily Increase Workload. Under Proposition 47, trial courts will experience a one–time increase in costs resulting from the processing of (1) resentencing petitions from offenders currently serving felony sentences for the crimes affected by Proposition 47 and (2) reclassification petitions from individuals who have already completed their sentences. Resentencing requests eligible under the proposition will be resolved in judicial hearings. Based on our discussions with the courts, such resentencing hearings could last minutes if the request is uncontested or several hours if evidence and arguments need to be presented. In contrast, Proposition 47 authorizes the court to resolve reclassification petitions without a hearing. Finally, the proposition requires that all petitions be filed within three years of its enactment unless the petitioner can demonstrate good cause for filing at a later date.

Reduction in Felony Cases and Other Hearings Will Permanently Reduce Workload. The above increased costs to the courts will be partly offset by savings in other court workload. First, because misdemeanors generally take less court time to process than felonies, the reduction in penalties will reduce the amount of resources needed for such cases. Second, Proposition 47 will reduce the amount of time offenders spend on county community supervision, resulting in fewer offenders being supervised at any given time. This will likely reduce the number of court hearings for offenders who break the rules that they are required to follow while supervised in the community. Overall, we estimate that the measure would likely result in a net increase in court workload for a few years with a net annual reduction thereafter.

The Governor’s budget proposes a $34.5 million General Fund augmentation to the courts—$26.9 million in 2015–16 and $7.6 million in 2016–17—to address increased workload related to resentencing petitions. The budget includes provisional language to allow the amount proposed for 2015–16 to be available for this workload until June 30, 2017. The proposed augmentation does not include funding for costs related to reclassification hearings and does not include an adjustment to reflect savings from reductions in workload resulting from the implementation of Proposition 47. According to the judicial branch, funds would be allocated to trial courts on a workload basis.

Estimate of Resentencing Costs Appears Reasonable for 2015–16. . . In order to estimate the cost to process resentencing requests, the administration relied on historical data on sentencing outcomes, workload, felony filing patterns, and trial court staffing costs. This historical data served as a proxy for potential workload given the current lack of reliable data on actual increases in court workload. (We would note that the judicial branch has started to collect data on the number of petitions filed related to Proposition 47 and the time required to resolve them.) The administration assumes that the majority of the workload would occur in the first 18 months following the passage of the proposition. We note that a portion of the funding proposed for 2015–16 would reimburse courts for workload that occurred in 2014–15—specifically the first eight months following the passage Proposition 47. In general, we find that the administration’s methodology for calculating potential resentencing costs appears reasonable given the limited data available.

. . .But Costs After 2015–16 Are Uncertain. While the administration’s estimate appears reasonable for 2015–16 based on the limited data currently available, it is unclear at this time if the proposed $7.6 million for 2016–17 will be necessary. The availability of data collected in 2015–16 would help resolve several uncertainties about the workload associated with Proposition 47 resentencing hearings. First, it is currently unknown whether the administration’s estimates will match the actual workload received and processed by the trial courts. For example, fewer petitions may be filed or more court time may be needed to process a hearing than assumed in the Governor’s budget. Second, while Proposition 47 requires that offenders must file their petitions for resentencing within three years of the proposition’s enactment unless there is good cause for a later filing, there are no requirements on how quickly trial courts must resolve these petitions. We note that the proposition generally requires that the judge who originally sentenced the offender address the resentencing request. This could result in courts resolving resentencing cases beyond the time frame assumed in the administration’s estimate.

Lack of Data Related to Other Effects on Courts. Although the judicial branch indicates that it is has started to collect data related to Proposition 47 (such as the number of resentencing or reclassification petitions received), the judicial branch is not currently collecting data to measure the proposition’s impact on other court workload. For example, data is not currently being collected on the number of cases being filed as misdemeanors that otherwise would have been filed as felonies absent enactment of the proposition. The availability of such data would provide the Legislature with the necessary information to determine whether adjustments to trial court funding are necessary. Because Proposition 47 requires that any state savings from its enactment (including those obtained from reduced court workload) be annually deposited into the SNSF, this data will be needed to accurately estimate the size of this deposit.

Only Approve Proposed Funding for 2015–16. We recommend that the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposed $26.9 million General Fund augmentation in 2015–16 to address court workload related to resentencing petitions. Based on the data currently available, the administration’s estimates and funding request for the budget year are reasonable. The additional funding would minimize impacts on the processing of other court workload—such as backlogs—that would result if the courts were required to absorb the additional workload related to Proposition 47. In addition, the additional funding would help ensure that there are no delays in the resentencing hearings. This is important because such delays could postpone the release of inmates eligible for reduced sentences, which in turn would reduce the amount of state and county correctional savings resulting from the proposition. In addition, we recommend the Legislature direct the judicial branch to provide an update at budget committee hearings this spring regarding the impact of Proposition 47 on trial court workload. To the extent additional data is available and shows a different level of funding is necessary, the Legislature could adjust the request accordingly.

However, we recommend that the Legislature not approve the Governor’s proposed $7.6 million General Fund augmentation for 2016–17 at this time. Instead, we recommend the Legislature require the administration to provide an updated workload calculation as part of the deliberations on the 2016–17 budget. By using updated data from the judicial branch on the actual workload impacts of processing petitions for resentencing and reclassification, the administration and the Legislature would be able to more accurately determine the appropriate level of funding needed in 2016–17.

Require Data Collection to Enable Calculation of Savings From Reduced Workload. We also recommend that the Legislature require the Judicial Council to immediately begin collecting additional data to measure the proposition’s impact on overall court workload (such as the number of cases being filed as misdemeanors instead of felonies), and report on the overall effect of Proposition 47 on the courts. Without such workload data, it would be difficult to accurately calculate the amount of court savings needed to be deposited into the SNSF.

The reduction in penalties authorized in Proposition 47 will affect county jails and probation departments, as well as various other county agencies (such as public defenders and district attorneys’ offices). In general, the proposition will significantly reduce criminal justice workload for counties. We estimate that, prior to the passage of Proposition 47, counties spent several hundred million dollars annually on workload that will be eliminated by the measure. However, local decisions on how to respond to this workload reduction will determine whether it results in fiscal savings or improvements to the administration of local criminal justice systems, such as reduced jail overcrowding. We discuss below the specific effects of Proposition 47 on jails, probation departments, and other county agencies.

Reduction in County Jail Workload. Proposition 47 will reduce the workload for county jails associated with the individuals affected by the measure for several reasons. First, offenders convicted of the crimes affected by the measure will generally receive shorter jail terms than they otherwise would have. This is because the maximum amount of time an offender can be held in jail for a misdemeanor is one year. In contrast, when these offenses were classified as felonies, offenders were typically eligible for jail terms of between 16 months and 3 years. Second, individuals arrested for the crimes affected by Proposition 47 are less likely to be held in jail prior to the conclusion of their court case. This is because counties are less likely to hold individuals arrested for misdemeanors prior to their trials as compared to those arrested for felonies. Finally, some offenders serving sentences in jail for the crimes affected by Proposition 47 are eligible for shorter jail terms or release if they are successfully resentenced.

The above reductions in jail workload will be slightly offset by an increase in workload associated with offenders who would otherwise have been sentenced to state prison. As discussed above, when offenders who have not previously been convicted of one of the severe crimes listed in the measure commit one of the crimes affected by Proposition 47, they can only be subject to misdemeanor penalties. Accordingly, they can no longer be sentenced to state prison and may instead serve their sentences in county jail. Despite this possible increase in workload, we estimate that the total number of statewide county jail beds freed up by these changes could reach into the low tens of thousands annually within a few years.

Relief to Overcrowded Jails. Although Proposition 47 will free up county jail beds, it will not necessarily result in a reduction in the county jail population of a similar size. This is because, just prior to the passage of Proposition 47, 33 of the state’s 58 counties—which account for two–thirds of the state’s jail population—had overcrowded jails and therefore were releasing inmates early. Such overcrowded jails could use the freed up beds created by the measure to reduce early releases. This would result in longer sentences being served by the remaining jail population. In these cases, there would be little or no reduction in the size of the jail population in the affected counties. Alternatively, the freed up jail beds could be used to reduce overcrowding. This could improve the operation of jails in a couple of ways. First, it can require more staff and be more difficult to manage inmates in crowded conditions than if the jail is operating at or closer to its design capacity. In addition, reduced overcrowding could improve a county’s ability to provide rehabilitation or health care services to inmates by freeing up the space necessary to conduct classes and provide treatment.

Cost Reductions for Other Jails. Jails that are not overcrowded will have reduced operating costs because they will have fewer inmates under their supervision. At a minimum, these counties will realize savings from purchasing less food, clothing, and other items used daily by inmates. Additional savings could also be realized, depending on the extent to which these counties are able to reduce higher cost components of their jail operations, such as staffing.

Probation Workload Likely to Decline. County probation departments will experience reduced workload as a result of Proposition 47 for a couple of reasons. First, offenders who are sentenced for misdemeanors generally receive less intensive community supervision than offenders sentenced for felonies. For example, probation departments typically conduct routine meetings and compliance checks with felony offenders, while many individuals on community supervision for a misdemeanor are seldom required to meet with their probation officer or be subjected to compliance checks. In addition, some offenders typically spend less time under community supervision when they are sentenced for a misdemeanor instead of a felony. We estimate that this reduction in supervision terms could result in county probation departments experiencing a reduction of thousands of offenders in their caseloads annually.

Impact on Community Supervision Services and Costs Could Vary. The effect on counties will depend on how they respond to the above reductions in community supervision workload. Counties could use the freed up resources to conduct more intensive supervision on the remaining population or provide offenders with additional rehabilitative services. Alternatively, counties could achieve savings from the reduced probation workload and redirect the funds to other local priorities. The extent to which counties choose to use the freed up resources to provide more intensive probation services versus achieving cost savings could vary by county and will likely depend on numerous factors, such as whether probation departments were adequately staffed prior to these changes.

Unclear Effect on SB 678 Grants. Chapter 608, Statutes of 2009 (SB 678, Leno), commonly referred to as SB 678, was enacted to improve outcomes for certain individuals supervised by probation departments by giving counties a fiscal incentive to reduce the number of such offenders who violate the terms of their supervision and are incarcerated. For example, SB 678 provides counties a share of the state prison and parole savings that occur when such offenders are successful and not sent to state prison. Because Proposition 47 reduces the total population of offenders under community supervision by counties, it could reduce the population that is eligible for grant funds. As a result, it is possible the size of the grant that each county probation department receives will decline. Alternatively, it is possible that the size of each county’s grant will increase as a result of Proposition 47. For example, if the remaining individuals supervised by a county probation department have higher rates of success, that county’s grant could increase. As a result, it is possible that some counties could see an increase in SB 678 grants while other counties could see a decline, depending on differences in their probation population. Because of limitations on the data available, it is not possible for us to determine at this time whether SB 678 probation grants are likely to increase or decrease statewide as a result of Proposition 47.

As discussed above, the reduction in penalties from Proposition 47 will increase court workload associated with resentencing and reclassification of offenders over the next few years. As a result, county district attorneys’ and public defenders’ offices (who participate in these processes) and county sheriffs (who provide court security) could experience a temporary increase in workload. However, Proposition 47 will reduce on an ongoing basis the workload for these local agencies associated with both felony filings and other court hearings (such as for offenders who break the rules of their community supervision). However, these effects on county workload are unlikely to generate significant costs or savings.

As discussed above, the 2011 realignment shifted responsibility for thousands of less serious felony offenders from the state to counties. The state provided counties around $1 billion to support this increased responsibility. Proposition 47 reduces the sentences for some of the realigned offenders. Specifically, realigned offenders who have committed an offense specified in the proposition will be subject to misdemeanor, rather than felony penalties. As a result, some of the workload reduction to counties discussed above is related to realigned offenders. While detailed data on the specific number of realigned offenders affected by Proposition 47 is currently unavailable at this time, the number could be substantial because both the 2011 realignment and Proposition 47 generally affect the same types of less serious felony offenders.

As discussed earlier, Proposition 47 requires that the annual savings to the state from the measure be annually transferred to the SNSF. The actual amount of funding deposited into the SNSF can vary significantly depending primarily on (1) the estimated size of the reduction in the state prison population and (2) whether and how the state reduces prison capacity in response to a decline in the inmate population.

Reduction in State Prison Population. The impact of Proposition 47 on the state’s prison population will significantly depend on both the prospective penalty reductions and the resentencing provisions in the measure. The actual impact of the penalty reductions in Proposition 47 will be difficult to determine with certainty because of data limitations. An estimate of the impact will depend heavily on the number of offenders historically sentenced to state prison for crimes affected by the measure. While CDCR has information on the types of crimes for which offenders are sent to prison, it lacks the data needed to make a precise estimate (such as the dollar value involved in certain theft related crimes). In addition, county sentencing practices could change in the future, which would further impact the effects of the prospective penalty reductions. The impact of the resentencing of inmates currently in prison is also difficult to predict. For example, the size of this impact on the prison population will depend heavily on how many inmates are eligible for resentencing, which is uncertain due to the above data limitations. In addition, each resentencing application is subject to judicial review and it is difficult to predict the outcome and timing of court decisions.

Reduction in Prison Capacity. The size of the deposit into the SNSF could also vary significantly depending on whether and how the state reduces prison capacity in response to a decline in the prison population. In particular, the state could take one (or some combination) of three possible approaches that would result in varying levels of savings. First, the state could attempt to close a prison and achieve the greatest amount of savings—perhaps as much as $50,000 annually per inmate. Second, the state could reduce its use of contract beds, which would achieve less savings—about $28,000 annually per inmate. Finally, the state could keep all of its 34 prisons open but reduce the number of inmates housed in them, which would achieve the least amount of savings—about $9,500 annually per inmate.

SNSF Deposit Could Be Significant. Based on historic sentencing practices, we estimate that the total annual deposit into the SNSF will likely range from $100 million to $200 million beginning in 2016–17. Because the state savings from the resentencing provisions in the measure are temporary in nature, the deposit in future years could be somewhat smaller, but will still likely fall within the $100 million to $200 million range.

Although Proposition 47 states that the monies in the SNSF shall be allocated to particular departments based on specific percentages for particular purposes, the Legislature has the opportunity to provide some direction on how the funds are spent in a manner that furthers the purpose of the proposition. In particular we have identified a couple of key policy questions for legislative consideration. Specifically, the Legislature could weigh in on (1) how the individual departments should distribute the funds and (2) how much state oversight to provide to ensure that the funds are being spent effectively. In our view, the appropriate answers to these questions will vary depending on the program area. To the extent the Legislature wishes to weigh in on these issues, it has a couple of options. For example, the Legislature could hold hearings and ask the administration to present its plans for allocating the funds. The Legislature could also pass legislation directing the administration to allocate the funds consistent with its priorities. (We would note that, depending on the specific language, it is possible that such legislation could require a two–thirds majority vote of the Legislature, based on the provisions of the proposition.) In order to give the departments and potential grant recipients time to plan, we recommend that the Legislature begin addressing these issues in the near term. Below, we recommend some possible approaches the Legislature could consider for each of the three program areas that will receive funding under Proposition 47—mental health and substance use treatment, K–12 truancy and dropout prevention programs, and victim services.

As discussed previously, Proposition 47 states that 65 percent of the SNSF shall be allocated to BSCC to administer a grant program for public agencies to support mental health treatment and substance use treatment to reduce recidivism, particularly for individuals convicted of less serious crimes, such as those affected by the measure. (The BSCC is responsible for administering various criminal justice grant programs and providing technical assistance to local authorities, among other responsibilities.) We estimate funding available for this grant program will likely total between $65 million and $130 million annually beginning in 2016–17.

Currently, mental health and substance use treatment services are provided to individuals in the state by a variety of programs with services provided by both private and public providers. These programs are supported from state, local, federal, and private funds. For example, these programs receive funding from private insurers, Medi–Cal, federal block grants, and Proposition 63 (also known as the Mental Health Services Act). We also note that many of these programs have overlapping target populations. In fact, many of the individuals that would be eligible for services funded by the SNSF are also eligible for services provided by the current mental health and substance use treatment system. Public spending in California on mental health and substance use treatment services is roughly $8 billion annually.

In order to ensure that BSCC distributes SNSF funds in an effective manner, we recommend that the Legislature direct BSCC to (1) coordinate SNSF funding with existing funding sources, (2) allocate funds in a manner that maximizes their impact, and (3) evaluate grant recipients’ ability to achieve recidivism reduction goals.

Coordinate With Existing Programs and Funding Sources. As noted above, there are currently many state, local, and private programs that deliver mental health and substance use services, including those that focus on individuals in the criminal justice system. Individuals may participate in several programs, and programs may receive funding from several sources. As such, it is important that the SNSF grant program for these services be structured to complement these existing programs. In considering how the SNSF fits into the existing system, there are several factors to consider: (1) many individuals in need of treatment do not have access to existing programs, (2) many existing programs could serve additional individuals or provide additional services with increased funding, and (3) given that many providers receive funding from multiple sources, there may be significant difficulty associated with managing multiple grants and billing sources. To coordinate SNSF funds with the existing programs and funding sources in a manner that addresses these concerns, we recommend that the Legislature direct BSCC to:

- Target Underserved Populations. Although there are a variety of mental health and substance use treatment programs currently provided in the state, some individuals may not have access to or be eligible for these programs. For example, Medi–Cal funds a variety of mental health services, but jail inmates are not eligible for Medi–Cal services. In addition, some individuals live in areas that have a limited number of services and providers—making it difficult for them to access treatment or find providers. Given these limitations, the Legislature could direct BSCC to require applicants to demonstrate that they target underserved populations, or the Legislature could specify which populations BSCC should target (such as jail inmates or individuals living in areas with few treatment options) when distributing SNSF funding.

- Target Programs That Lack Other Funding Sources. Given that there are already funds available for certain mental health and substance use treatment services, the Legislature may want to direct BSCC to prioritize programs or services that have difficulty obtaining funding from existing sources. For example, some residential treatment programs are not eligible for Medi–Cal funding, which limits the availability of those programs. The Legislature could direct BSCC to identify programs and services that do not have access to existing mental health and substance use treatment funding and target SNSF grants toward those programs, or could identify which specific programs (such as jail–based programs) that the BSCC should prioritize when distributing SNSF funding.

- Minimize Administrative Burden. Many mental health and substance use treatment service providers receive funding from multiple sources, which can create administrative burdens for these providers. For example, such providers may be required to submit several different grant applications and bill different entities for the services provided. In order to minimize the potential burdens of applications and reporting associated with the newly established SNSF grant program, the Legislature could require BSCC to streamline the grant process (such as by establishing standardized applications to ensure that administrative processes are as streamlined as possible). The Legislature could also require BSCC to coordinate the SNSF grant program with other grants administered by the state to minimize the administrative burdens placed on providers.

Allocate Funds to Maximize Impact. We also recommend the Legislature direct BSCC to prioritize the use of SNSF grants for programs that are shown to be cost–effective. There is a significant body of research on mental health and substance use programs that can reduce recidivism in a cost–effective manner if implemented in accordance with best practices. These are programs that have been delivered in the past and found to reduce recidivism and result in costs savings. Such programs include offender education programs, inpatient drug treatment, and work release programs. Given the limited funding available, the Legislature could direct BSCC to fund only programs that have been proven to be cost–effective. Alternatively, some funds could be set aside for programs that are likely to be effective, but currently lack sufficient data to show that they are in fact cost–effective.

Evaluate Grant Recipients Based on Outcomes. In order to ensure that SNSF dollars are being used effectively, we recommend that the Legislature require the evaluation of recipients and the outcomes they achieve. This would serve two major purposes. First, it would ensure that programs are achieving the intended recidivism reduction goals in a cost–effective manner. Second, it would allow programs that have not previously been proven to reduce recidivism cost–effectively to demonstrate their ability to do so. In order to facilitate such evaluation, the Legislature could direct BSCC to establish a periodic evaluation process for grant recipients. For example, BSCC could require grant recipients to submit specific performance information, including cost, participation, completion, and recidivism reduction data. The Legislature could have BSCC periodically report on the outcomes achieved. The BSCC could use the information gathered to inform future funding decisions.

Proposition 47 requires that 25 percent of the SNSF go to CDE to administer a grant program to reduce truancy, high school dropout, and student victimization rates. We estimate funding available for this grant will likely total between $25 million and $50 million annually beginning in 2016–17. Recently enacted changes to the way the state funds and oversees school districts provide important context for the Legislature’s decisions regarding SNSF funds. This new school funding paradigm leads us to recommend a somewhat more flexible approach for the education portion of the SNSF as compared to the other grant programs authorized by the proposition.

State Recently Adopted New Funding and Accountability System for Schools. Prior to 2013–14, the state allocated a notable portion of school funding via a number of discrete “categorical” grants, each of which had an associated set of requirements and allowable activities. In enacting the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), the state replaced that categorical–based approach with a formula–based system that allocates funding according to certain student characteristics. Specifically, the LCFF provides a base per–pupil grant to every district, then allocates supplemental funds based on the number of English learners, low–income, or foster youth (EL/LI) students each district serves. Districts with particularly high concentrations of EL/LI students (at least 55 percent of enrollment) receive an additional allocation. Districts generally have broad flexibility over how they may spend LCFF dollars, although they must use the supplemental and concentration funds the state provides on behalf of EL/LI students in ways that “principally benefit” those student groups. In 2014–15, the state awarded a total of $47 billion to districts via the LCFF. (Because fully funding the new formula would cost an additional $9 billion, implementation is being phased in over the next several years.) In conjunction with the LCFF, the state also adopted a new system of planning, support, and intervention to help ensure that districts are held accountable for meeting certain student outcomes. Under this system, districts must report their progress on certain measures, including student achievement, attendance, and dropout rates. Districts that do not meet established performance expectations in these areas will receive additional support and intervention. (For more detailed information about the LCFF and the new state accountability system, please see our report, An Overview of the Local Control Funding Formula.)

LCFF Changes Context for Allocating SNSF Funds to Districts. The state’s new focus on local control over school spending makes it somewhat more complicated for the Legislature to also satisfy the intent outlined in Proposition 47—that the funds be targeted for improving student outcomes, reducing truancy, and supporting certain at–risk student groups. Based on historical practice, the state could create a new, discrete categorical program for districts that agree to use the funds for a specific list of state–established, allowable activities focused on these goals. Such a prescriptive approach, however, would deviate from the state’s recent effort to eliminate most unique state education grants linked to particular activities.

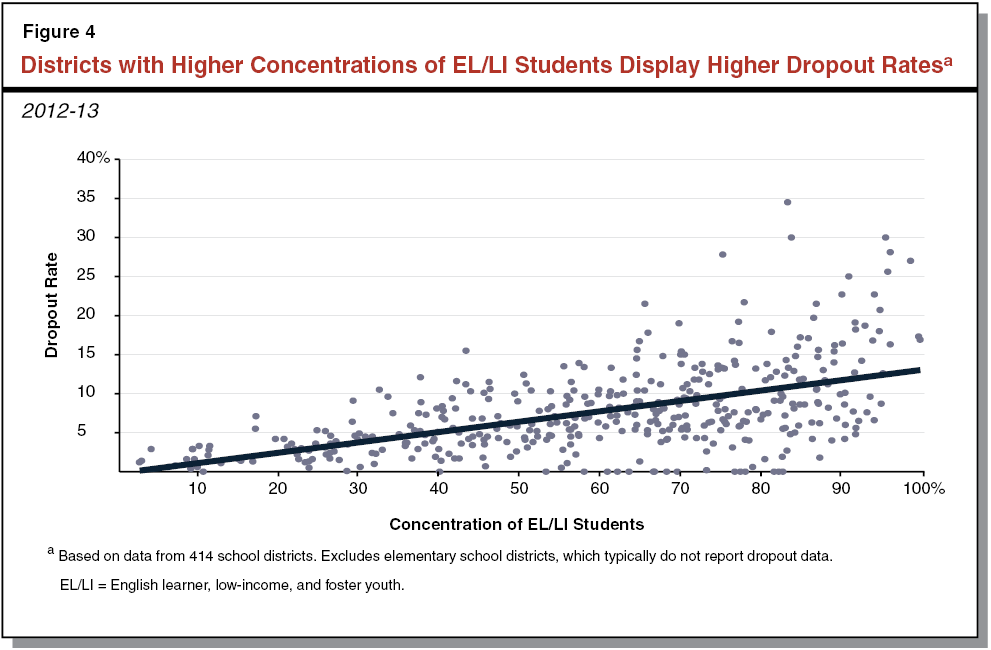

Allocate Funds to Districts With High Concentrations of At–Risk Students. We recommend the Legislature allocate SNSF funds to districts that have notably high concentrations of EL/LI students. This allocation method would create a new grant separate from the LCFF, yet would be consistent with the LCFF principle of providing additional funds to districts serving students with certain characteristics. While this approach does not allocate funds explicitly based on districts displaying the poor student outcomes described in the measure, research indicates that EL/LI students are at higher risk than other students for truancy, dropout, and victimization. Moreover, districts with high concentrations of these student groups frequently display poorer outcomes. For example, Figure 4 illustrates that as California districts’ concentrations of EL/LI students increase, so do their dropout rates. Increasing funding for such districts therefore could help improve such outcomes. To target the districts with the greatest need and provide grants large enough to support meaningful local efforts, we recommend setting a relatively high eligibility threshold for receiving the SNSF funds (higher than the LCFF concentration threshold of 55 percent). Per–pupil funding rates would depend upon which threshold is established, with stricter thresholds resulting in higher per–pupil rates (but serving fewer students). For example, we estimate setting the threshold at 65 percent EL/LI enrollment would provide about $25 per student for 2.4 million EL/LI students in about 450 districts. In contrast, funding only districts enrolling at least 85 percent EL/LI students would provide about $75 per student for about 830,000 EL/LI students in 180 districts. (These amounts still are notably less than the roughly $1,600 per EL/LI student districts will receive in supplemental LCFF funds when the formula is fully implemented.)

Focus on Outcomes, Not Spending Requirements. Consistent with the regulations governing LCFF expenditures, we recommend the Legislature impose a broad requirement that districts use SNSF funds to principally benefit students at risk of truancy, dropout, or victimization while still permitting local district leaders to determine which specific activities to undertake. Instead of tracking expenditures of the funds, we recommend the state rely on its newly adopted accountability system to monitor student outcomes and intervene in districts that fail to meet expectations for the targeted student groups. The state still is in the process of defining exactly how it will identify which districts are in need of additional assistance to improve student outcomes and the method by which such assistance will be provided. Student engagement—including absenteeism, dropout, and graduation rates—has been identified as a key state priority area, however, so the issues emphasized by Proposition 47 likely will be key areas of state oversight within the new system. (The accountability system should be more fully defined by 2016–17 when SNSF funds become available.) The state could consider adding special oversight emphasis on these outcomes for districts receiving SNSF funds to ensure they receive additional state intervention if they struggle to make improvements in these areas after receiving additional funding.

Proposition 47 requires that 10 percent of the SNSF go to VCGCB to administer a grant program to TRCs. We estimate funding available for this grant will likely total between $10 million and $20 million annually beginning in 2016–17. Below, we provide background information on the state’s existing TRCs and other victim programs, and make recommendations regarding this new funding for TRCs.

Existing TRCs. TRCs are centers that directly assist victims in coping with a traumatic event (such as by providing mental health care and substance use treatment). For example, victims may receive weekly counselling sessions with a licensed mental health professional at a TRC for a specified amount of time. The centers also sometimes help victims connect with other services provided in their community and by the state. While some of the TRCs existed before receiving state support, the state first began funding TRCs in 2001 with a grant to the San Francisco TRC. Since then, three other TRCs have also received state funding—one in Long Beach and two in Los Angeles. Currently, VCGCB provides a total of $2 million annually in grants to four TRCs.

- San Francisco TRC. The San Francisco TRC is affiliated with San Francisco General Hospital—a level I trauma center—and the University of California, San Francisco. (A level I trauma center is a 24–hour research and teaching hospital with the surgical and medical capabilities to handle the most severely injured patients.)

- Long Beach TRC. The Long Beach TRC is affiliated with Dignity Health St. Mary Medical Center—a level II trauma center—and California State University Long Beach. (A level II trauma center is 24–hour hospital with the surgical and medical capabilities to handle severely injured patients).

- Los Angeles TRC—Special Service for Groups. The first Los Angeles TRC to receive state funding is affiliated with a community–based organization, Special Service for Groups, which provides a wide array of services, such as substance use treatment, mental health counselling, and housing assistance.

- Los Angeles TRC—Downtown Women’s Center. The second Los Angeles TRC to receive state funding is affiliated with a community–based organization, the Downtown Women’s Center, which provides housing assistance and other supportive services in an effort to end homelessness for women.

Other Existing State Victim Programs. The majority of the state’s spending for victim services is through other programs that have existed for many years. Specifically, the state spends about $100 million annually on the victim compensation program, which reimburses some expenses (such as those related to mental health services) incurred by victims of certain crimes. This program is administered by VCGCB. In addition, the state spends another roughly $100 million annually on numerous smaller grant programs, primarily administered by the Office of Emergency Services, that provide funding primarily to local agencies and nonprofit organizations for various victim services, such as funding for victim advocates in district attorneys’ offices who focus on assisting victims through the legal process.

Given that the state only began funding TRCs in recent years and because of their limited number, we recommend that the Legislature provide additional guidance to VCGCB on the use of the SNSF to ensure that funds are used effectively to further the purposes of Proposition 47.

Structure Grants to Ensure Effectiveness. We recommend that the Legislature structure the grants for TRCs to ensure that funds are spent in a manner that effectively and efficiently provides services to victims. Specifically, the Legislature could consider:

- Requiring a “Trauma Informed” Approach. The Legislature could require that TRCs use a trauma–informed approach—an approach to delivering services that takes into account the unique needs of individuals suffering a trauma (such as providing multiple services from one location in order to limit the number of times victims must retell the story of their victimization in order to apply for assistance). Similarly, the Legislature could require that TRCs provide treatment with licensed mental health professionals who have the appropriate training necessary to work with victims of violent crimes. We are informed that the San Francisco TRC already uses such an approach.

- Establish Multiyear Grants. The Legislature could consider specifying the length of grants in order to ensure that new TRCs have a sufficient amount of time to get established before needing to apply for a renewal of their grant, or requiring the VCGCB to take such timing issues into consideration.

- Prioritizing Certain Qualifying Organizations. The Legislature could prioritize which types of organizations will receive grant funds in the event that more grant applications are received than can be funded with available Proposition 47 monies. For example, establishing TRCs affiliated with trauma hospitals (as is the case with two of the state—funded TRCs) provides a point of access to recovery services for the most severely injured crime victims, as these victims will likely be taken to a trauma hospital for medical treatment.

Ensure Receipt of Federal Reimbursement Funds. Under the federal Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) grant program, the state is eligible to receive a federal reimbursement of 60 cents for every state dollar spent on qualifying victim services. Examples of qualifying victim services include mental health counselling and medical expenses. Some of the services TRCs are likely to provide to crime victims are eligible for federal VOCA funds. If the state is able to get VOCA funds for its expenditures on TRCs, it could increase the funding for victim services resulting from Proposition 47 by up to 60 percent. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature direct the VCGCB to ensure that the state receives all eligible federal VOCA funds for services provided through TRCs. For example, the Legislature could consider requiring VCGCB to collect information on eligible expenditures from grant recipients and include these amounts when applying for federal VOCA funds.

Evaluate Grant Recipients Based on Outcomes. In order to ensure that SNSF dollars are being used effectively, we recommend the Legislature require the evaluation of TRC grant recipients and the outcomes they achieve. The Legislature could specify certain basic evaluation criteria (such as the number of victims served, types of services provided, and improvements in victims’ mental health) and require VCGCB to develop additional criteria that it deems necessary. The Legislature could also have the VCGCB periodically report on the outcomes achieved and any changes made to the grant program as a result of the findings. The VCGCB could use the information gathered to inform future funding decisions. This would help ensure that TRCs are delivering services to victims effectively.

Consider How Funding Fits Into Broader Victims Programs. Grants to TRCs are only one of many state programs that assists victims. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature consider how this additional funding and the corresponding expansion in the number of TRCs fits into the state’s broader provision of services to crime victims. For example, the Legislature could consider requiring TRCs to assist victims with applying to the victim compensation program or create streamlined processes for TRCs that provide such assistance. Similarly, the Legislature could review existing programs to ensure that they are not duplicating the efforts of the new TRCs and that the overall administration of victim programs is well coordinated.

Proposition 47 represents a significant change to the state’s criminal justice system. In the next few years, the Legislature will be faced with major decisions related to the implementation of Proposition 47. Most significantly, the Legislature will have to decide how to manage the reduction in the size of the prison population and how the state savings from the measure should be used to provide services to offenders, students, and victims. We recommend that the Legislature begin considering these issues now to ensure that the potential benefits to the state are maximized. Specifically, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR, the judicial branch, and counties to provide it with the necessary information to effectively address the various issues raised by the implementation of Proposition 47. In addition, we recommend that the Legislature begin deciding now how to use the state savings created by Proposition 47 in a manner that will most improve (1) recidivism rates, (2) truancy and dropout rates, and (3) services to victims.