In this report, we assess many of the Governor’s budget proposals in the resources and environmental protection area and recommend various changes. We provide a complete listing of our recommendations at the end of this report.

Budget Provides $9.3 Billion for Programs. The Governor’s budget for 2015–16 proposes a total of $9.3 billion in expenditures from the General Fund, various special funds, bond funds, and federal funds for resources and environmental protection programs. This includes $4.4 billion for the Department of Water Resources, $1.8 billion for the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire), $1.5 billion for the Department of Resources Recycling and Recovery, as well as funding for many other departments. This proposed level of spending is a decrease of $1.4 billion, or 13 percent, below estimated expenditures in the current year, mostly related to lower bond funds for resources programs.

Water Policies a Major Focus of Governor’s Budget. The proposed budget includes three significant sets of water–related proposals. For each of these, we offer the Legislature recommendations designed to better ensure effective implementation of the proposals.

- Proposition 1E of 2006—Flood Protection. The Governor proposes to appropriate the remaining $1.1 billion in flood protection funds from Proposition 1E. In addition, the Governor is requesting that the funds be appropriated on a ten–year basis and with administrative flexibility to shift funds among state operations, local assistance, and capital outlay purposes. The administration makes this request because the proposition required all funds to be appropriated no later than July 2016. We find, however, that these provisions would significantly hamper the Legislature’s traditional role of being able to prioritize projects and conduct oversight. We recommend appropriating Proposition 1E funds for specific projects in 2015–16 and 2016–17, and using pay–as–you–go in following years. This approach would allow some of the remaining Proposition 1E funds to support projects in the near term, reduce long term financing costs, and maintain the Legislature’s traditional oversight role through the budget process.

- Proposition 1 of 2014—Water Bond. Proposition 1 authorizes $7.5 billion for various water–related purposes, such as water storage, watershed protection, and water quality improvements. The Governor’s budget proposes $533 million of these funds for various programs in 2015–16. Please see our companion report The 2015–16 Budget: Effectively Implementing the 2014 Water Bond for our recommendations designed to ensure that cost–effective projects are funded and that such projects are adequately overseen and evaluated.

- Drought Funding. The Governor’s budget includes $115 million—mostly from the General Fund—for a range of activities designed to reduce the impacts of the current drought. This includes funding for fire protection, emergency water supplies, and protection of vulnerable fish and wildlife. Since water conditions in 2015–16 will not be known until the end of California’s traditional rainy season later this spring, we withhold recommendation on these proposals until more information on water conditions is available.

Cap–and–Trade Auction Revenues Underestimated. The Governor’s budget assumes that state revenues generated from auctioning carbon allowances in 2015–16 will total $1 billion. We find that actual revenues most likely will be significantly higher than estimated, perhaps by $1 billion or more. This underestimate has spending implications for two reasons. First, 60 percent of auction revenues are continuously appropriated to specific programs, such as high–speed rail and sustainable communities. So, a share of any higher revenues will automatically be directed to those programs. Second, the Legislature will have options for how to allocate the remaining 40 percent of any additional revenues. This could include expanding existing programs, funding new climate change programs, or reserving the funding for future years. In considering these options, the Legislature will want to take into account various factors and trade–offs, such as costs and the degree to which investments are likely to help the state reach its carbon emission goals.

Opportunities for Legislative Oversight. The Governor’s budget raises several issues that we believe merit greater legislative oversight. We recommend the Legislature take steps to ensure that the proposals are likely to be cost–effective and consistent with its priorities.

- CalFire Helicopter Procurement. The budget includes language to allow CalFire to begin the procurement process to replace its helicopter fleet. Despite potential General Fund costs of a couple hundred million dollars, the department has not provided the Legislature with information regarding equipment, operating, or capital costs; design specifications; or procurement schedule. Consequently, we recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the request and require CalFire to provide this information at budget hearings. If it does not do so, we would recommend rejecting the proposed language.

- Air Resources Board (ARB) Southern California Consolidation Project. The budget for ARB includes $5.9 million in 2015–16 to develop design criteria for a new consolidated testing and research facility in Southern California. The project is estimated to cost a total of $366 million, but the board has not provided important details regarding (1) how it determined the facility’s size, (2) other viable alternatives, and (3) the long term funding plan. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature direct the board to provide this information before making a decision on whether to move forward on the project.

- Environmental License Plate Fund (ELPF) Shortfall. The Governor proposes several changes—including delaying the implementation of new programs, funding shifts, and increased personalized license plate fees—to address a budget shortfall in the ELPF. We recommend the Legislature require the administration to provide additional information on ELPF–funded activities. Based on that information, the Legislature can make more informed decisions about what spending reductions or fee increases are most consistent with its priorities for the fund.

Total Spending Proposed of $9.3 Billion in 2015–16. The Governor’s budget for 2015–16 proposes a total of $9.3 billion in expenditures from various fund sources—the General Fund, various special funds, bond funds, and federal funds—for programs administered by the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Agencies. This level is a decrease of $1.4 billion, or 13 percent, below estimated expenditures for the current year. Most of the proposed reduction in spending is in the resources area. Specifically, the budget proposes $5.7 billion in 2015–16 for resources programs, a decrease of $1.3 billion (18 percent) from 2014–15. Proposed expenditures for environmental protection departments are $3.7 billion, a decrease of $100 million (3 percent) from 2014–15.

The reduction in proposed spending for resources and environmental protection programs is mostly related to spending from bond funds. Specifically, the budget proposes bond expenditures totaling about $1.9 billion in 2015–16—a decrease of $1.1 billion, or 36 percent, below estimated bond expenditures in the current year. Some of this decrease, however, is related to how bond funds are accounted for in the budget, making year–over–year comparisons difficult. In fact, the proposed budget includes substantial new investment of bond funds, particularly for flood protection and other water–related purposes, as described in more detail below. General Fund spending on resources and environmental protection programs is proposed to be $2.6 billion in 2015–16, a net increase of $50 million, or about 2 percent. This reflects increased expenditures for debt–service on general obligation bonds, partially offset by decreased General Fund spending in various departments.

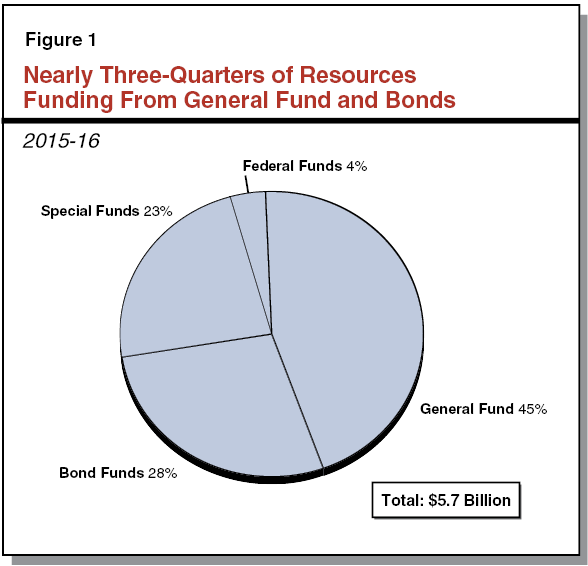

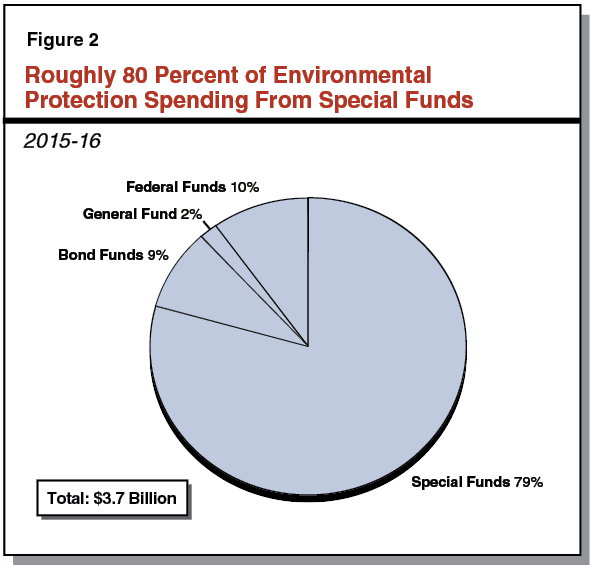

Programs Rely on Varying Fund Sources. Departments within the Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Agencies vary significantly in which fund sources support their programs. As shown in Figure 1, resources programs are primarily dependent on the General Fund and bond funds (which are ultimately repaid from the General Fund in most of these cases). These two sources make up almost three–quarters of funding for these departments in 2015–16. Environmental protection departments, on the other hand, are primarily dependent on special funds, usually derived from fees. As shown in Figure 2, the Governor’s budget proposal assumes roughly 80 percent of funding for these departments will come from special funds next year.

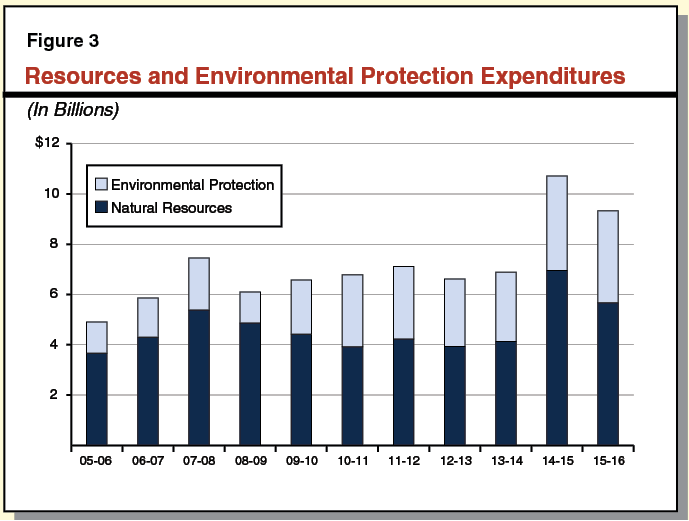

Historical Expenditure Trend Reflects Various Fund Increases. Figure 3 shows total expenditures for resources and environmental protection programs since 2005–06. The proposed funding level in the current and budget years would represent a significant increase over prior years, increasing from $4.9 billion in 2005–06 to $9.3 billion in 2015–16. The total for 2015–16 includes more spending from bond funds by resources departments, a proposed increase of $2 billion compared to 2005–06. (We note, however, that the amount of bonds actually expended in 2015–16 will be less than appropriated because departments generally have multiple years to spend these funds.) This trend of increased bond spending largely reflects the passage by voters of bonds in 2006 (Propositions 1E and 84) and 2014 (Proposition 1), which provided a total of about $17 billion in bond authority for resources–related projects. In addition, General Fund spending in resources agencies is proposed to be $1.1 billion higher in the budget year compared to 2005–06, and spending from special funds by environmental protection departments is $1 billion higher over this period.

Figure 4 shows spending by selected fund sources for the state’s major resources programs and departments—that is, programs within the jurisdiction of the Natural Resources Agency. As the figure shows, total spending proposed for most resources programs is generally down in 2015–16, resulting from a reduction in bond fund expenditures. For example, the budget proposes a reduction of $738 million, or 36 percent, in bond spending for the Department of Water Resources (DWR).

Figure 4

Major Resources Budget Summary—Selected Funding Sources

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Department

|

Actual

2013–14

|

Estimated

2014–15

|

Proposed

2015–16

|

Change From 2014–15

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Water Resources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$96.7

|

$124.5

|

$83.2

|

–$41.3

|

–33.2%

|

|

State Water Project funds

|

822.3

|

1,916.4

|

1,916.0

|

–0.4

|

—

|

|

Bond funds

|

701.5

|

2,041.3

|

1,303.6

|

–737.7

|

–36.1

|

|

Electric Power Fund

|

881.2

|

958.0

|

961.6

|

3.6

|

0.4

|

|

Other funds

|

52.3

|

147.2

|

138.1

|

–9.1

|

–6.2

|

|

Totals

|

$2,554.0

|

$5,187.4

|

$4,402.5

|

–$784.9

|

–15.1%

|

|

Forestry and Fire Protection

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$773.1

|

$1,077.6

|

$1,086.6

|

$9.1

|

0.8%

|

|

Reimbursements

|

376.6

|

436.8

|

447.5

|

10.7

|

2.4

|

|

Other funds

|

103.5

|

256.6

|

237.0

|

–19.7

|

–7.7

|

|

Totals

|

$1,253.2

|

$1,771.0

|

$1,771.1

|

$0.1

|

—

|

|

Parks and Recreation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$117.6

|

$121.4

|

$115.9

|

–$5.5

|

–4.5%

|

|

Parks and Recreation Fund

|

136.5

|

173.2

|

176.5

|

3.3

|

1.9

|

|

Off–Highway Vehicle Trust Fund

|

82.8

|

160.1

|

92.5

|

–67.6

|

–42.2

|

|

Bond funds

|

114.2

|

108.4

|

22.5

|

–85.9

|

–79.2

|

|

Other funds

|

144.4

|

217.1

|

178.2

|

–38.9

|

–17.9

|

|

Totals

|

$595.5

|

$780.2

|

$585.6

|

–$194.6

|

–24.9%

|

|

Fish and Wildlife

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$65.8

|

$97.2

|

$80.9

|

–$16.3

|

–16.8%

|

|

Fish and Game Fund

|

102.8

|

123.2

|

133.3

|

10.1

|

8.2

|

|

Bond funds

|

21.8

|

76.4

|

53.7

|

–22.7

|

–29.7

|

|

Other funds

|

167.3

|

253.8

|

250.0

|

–3.8

|

–1.5

|

|

Totals

|

$357.7

|

$550.6

|

$517.9

|

–$32.7

|

–5.9%

|

|

Energy Commission

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Electric Program Investment Charge

|

$5.3

|

$373.9

|

$128.5

|

–$245.4

|

–65.6%

|

|

ARFVTF

|

101.2

|

172.9

|

109.1

|

–63.8

|

–36.9

|

|

Other funds

|

135.6

|

239.3

|

185.6

|

–53.7

|

–22.4

|

|

Totals

|

$242.1

|

$786.1

|

$423.2

|

–$362.9

|

–46.2%

|

Despite an overall decline in proposed bond spending for resources programs, the budget includes the appropriation of new bond funds in 2015–16 for both existing and new programs. In particular, the budget proposes to spend $1.3 billion in bond funds in DWR, including $1.1 billion in bond funding for flood protection projects from Proposition 1E (2006) and $87 million from the water bond approved by voters in November 2014 (Proposition 1).

Similar to Figure 4, Figure 5 shows spending and fund source information for the major environmental protection programs—those within the jurisdiction of the California Environmental Protection Agency. The proposed budget for the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) includes a $164 million increase in Underground Storage Tank Cleanup Funds, which primarily reflects implementation of recent policy changes adopted by the Legislature to (1) increase fees on petroleum stored in underground tanks and (2) use the resulting revenues for new and existing programs related to cleaning up contamination from underground storage tanks. The largest decrease in funding for environmental protection departments is in proposed bond spending by the Air Resources Board (ARB), which reflects the funding of projects from Proposition 1B bond funds in 2014–15 designed to reduce emissions associated with transporting goods on trucks, trains, and cargo ships.

Figure 5

Major Environmental Protection Budget Summary—Selected Funding Sources

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Department

|

Actual

2013–14

|

Estimated

2014–15

|

Proposed

2015–16

|

Change From 2014–15

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Resources Recycling and Recovery

|

|

|

|

|

|

Beverage container recycling funds

|

$1,181.9

|

$1,189.3

|

$1,181.9

|

–$7.4

|

–0.6%

|

|

Electronic Waste Recovery

|

76.3

|

95.9

|

101.5

|

5.6

|

5.8

|

|

Other funds

|

174.2

|

254.9

|

248.3

|

–6.6

|

–2.6

|

|

Totals

|

$1,432.4

|

$1,540.1

|

$1,531.7

|

–$8.4

|

–0.5%

|

|

State Water Resources Control Board

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$13.5

|

$42.3

|

$32.7

|

–$9.6

|

–22.7%

|

|

Underground Tank Cleanup

|

228.9

|

234.5

|

398.4

|

163.9

|

69.9

|

|

Bond funds

|

51.3

|

275.9

|

320.8

|

44.9

|

16.3

|

|

Waste Discharge Fund

|

109.0

|

122.0

|

120.2

|

–1.8

|

–1.5

|

|

Other funds

|

17.6

|

462.4

|

486.7

|

24.3

|

5.3

|

|

Totals

|

$420.3

|

$1,137.1

|

$1,358.8

|

$221.7

|

19.5%

|

|

Air Resources Board

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund

|

$30.9

|

$209.2

|

$211.9

|

$2.7

|

1.3%

|

|

Motor Vehicle Account

|

121.1

|

131.6

|

134.1

|

2.5

|

1.9

|

|

Air Pollution Control Fund

|

118.4

|

116.4

|

117.5

|

1.1

|

0.9

|

|

Bond funds

|

104.2

|

245.0

|

0.1

|

–244.9

|

–100.0

|

|

Other funds

|

113.8

|

146.2

|

118.5

|

–27.7

|

–18.9

|

|

Totals

|

$488.4

|

$848.4

|

$582.1

|

–$266.3

|

–31.4%

|

|

Toxic Substances Control

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$21.1

|

$27.3

|

$27.1

|

–$0.2

|

–0.7%

|

|

Hazardous Waste Control

|

52.1

|

58.9

|

60.0

|

1.1

|

1.9

|

|

Toxic Substances Control

|

43.8

|

45.9

|

48.9

|

3.0

|

6.5

|

|

Other funds

|

64.0

|

101.0

|

72.1

|

–28.9

|

–28.6

|

|

Totals

|

$181.0

|

$233.1

|

$208.1

|

–$25.0

|

–10.7%

|

|

Pesticide Regulation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pesticide Regulation Fund

|

$80.0

|

$84.7

|

$87.8

|

$3.1

|

3.7%

|

|

Other funds

|

3.1

|

3.0

|

3.1

|

0.1

|

3.3

|

|

Totals

|

$83.1

|

$87.7

|

$90.9

|

$3.2

|

3.6%

|

Assembly Bill 32. The Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (Chapter 488, Statutes of 2006 [AB 32, Núñez/Pavley]), commonly referred to as AB 32, established the goal of reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. Among other provisions, the legislation directed the ARB to develop a plan to achieve the maximum technologically feasible and cost–effective GHG emission reductions by 2020. This plan is commonly referred to as the AB 32 Scoping Plan. The Scoping Plan includes a wide variety of regulations and programs intended to reduce GHG emissions, including a cap–and–trade program.

Cap–and–Trade. The ARB adopted a cap–and–trade program that places a “cap” on aggregate GHG emissions from large GHG emitters (such as large industrial facilities, electricity suppliers, and transportation fuel suppliers), which are responsible for roughly 85 percent of the state’s GHG emissions. (Uncapped sources include agriculture, forestry, and relatively small GHG emitters.) The cap declines over time, ultimately arriving at the target emission level in 2020. To implement the cap–and–trade program, ARB allocates a number of carbon allowances equal to the cap, and each allowance is essentially a permit to emit one ton of carbon dioxide (or the equivalent amount for other GHGs). The ARB provides some allowances for free, making others available for purchase at quarterly auctions. Large emitters must then obtain allowances equal to their total emissions in a given period of time. They can purchase the allowances at the auctions. Entities can also “trade” (buy and sell on the open market) the allowances in order to obtain enough to cover their total emissions for a given period of time.

The supply and demand of allowances in a trading market generally determine the price of an allowance. Parties that can reduce their emissions—for instance, by modifying their production processes—are likely to do so as long as it is cheaper than buying allowances at current prices. In theory, the level of overall emissions reductions is achieved at the lowest cost possible. This is because the allowance price provides an economic incentive to all regulated emitters to find the mix of emissions reductions and allowance purchases that minimize their costs.

Results From Past Auctions. The ARB has conducted nine cap–and–trade auctions between November 2012 and November 2014—generating a total of $970 million in state revenue. Beginning January 1, 2015, transportation fuel suppliers are required to obtain allowances for the GHG emissions associated with the combustion of the fuels they provide. In connection with this change, the number of state–auctioned allowances will increase significantly and, as a result, future auctions are expected to raise greater amounts of state revenue than in the past.

Prior Legislative Direction for Use of Revenue. Three statutes enacted in 2012 provide some requirements and direction on the use of cap–and–trade auction revenue.

- Chapter 39, Statutes of 2012 (SB 1018, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review). Chapter 39 created the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), into which all auction revenue is to be deposited. The legislation requires that before departments can spend monies from the GGRF, they must prepare a record specifying: (1) how the expenditures will be used, (2) how the expenditures will further the purposes of AB 32, (3) how the expenditures will achieve GHG emission reductions, (4) how the department considered other non–GHG–related objectives, and (5) how the department will document the results of the expenditures.

- Chapter 807, Statutes of 2012 (AB 1532, Perez). Chapter 807 directed the Department of Finance (DOF) to develop and periodically update a three–year investment plan that identifies feasible and cost–effective GHG emission reduction investments. Chapter 807 requires that cap–and–trade auction revenues be used to reduce GHG emissions and, to the extent feasible, achieve co–benefits such as job creation, air quality improvements, and public health benefits. It also requires the DOF to submit an annual report to the Legislature by March 1 on the status and outcomes of GGRF–funded projects.

- Chapter 830, Statutes of 2012 (SB 535, de León). Chapter 830 requires that 25 percent of auction revenue be used to benefit disadvantaged communities. Chapter 830 also requires that 10 percent of auction revenue be invested in disadvantaged communities.

Expenditure Plan Adopted in 2014–15. The 2014–15 budget includes $832 million from the GGRF for various transportation, energy, and resources programs designed to reduce GHG emissions. At the time of this analysis, agencies are at varying stages of developing program guidelines, selecting projects, and expending funds. (For more detail on the types of programs that were funded in the 2014–15 budget, please see our report The 2014–15 Budget: California Spending Plan.)

Chapter 3, Statutes of 2014 (SB 862, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), also specifies how the state will allocate most cap–and–trade auction revenues in 2015–16 and beyond. For all future revenues, the legislation continuously appropriates (1) 25 percent for the state’s high–speed rail project, (2) 20 percent for affordable housing and sustainable communities grants (with at least half of this amount for affordable housing), (3) 10 percent for intercity rail capital projects, and (4) 5 percent for low carbon transit operations. The remaining 40 percent would be available for annual appropriation by the Legislature. Chapter 3 also requires that an outstanding loan of $400 million from the GGRF to the General Fund be repaid to the high–speed rail project when needed by the project.

Legal Restrictions on the Use of Auction Revenues. There are several ongoing legal challenges to the different components of the cap–and–trade program. For example, in 2012, the California Chamber of Commerce filed a lawsuit against the ARB claiming that cap–and–trade auction revenues constitute illegal tax revenue. In November 2013, the superior court ruled that the “charges” from the auction have characteristics of a tax as well as a fee, but that, on balance, the charges constitute legal regulatory fees. This ruling has been appealed to the appellate court. It is also possible that even if ultimately determined to be a fee, the courts would put limits on how the revenues can be used, just as all other state fees have spending constraints. For example, the state may be required to use the revenues from the cap–and–trade auctions to mitigate GHG emissions. Final decisions from the appellate courts on these issues may take years.

Continue Expenditure Plan Adopted as Part of 2014–15 Budget. The Governor’s budget assumes the receipt of $650 million in state revenue from cap–and–trade auctions in 2014–15 and $1 billion in 2015–16. As shown in Figure 6, the Governor proposes 2015–16 expenditures that are consistent with the framework adopted as part of the 2014–15 budget. For example, the Governor’s budget assumes that 60 percent of cap–and–trade revenues collected in 2015–16 would be continuously appropriated as follows: (1) $250 million for the state’s high–speed rail project, (2) $200 million for the Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities Program, (3) $100 million for the Transit and Intercity Rail Capital Program, and (4) $50 million for the Low Carbon Transit Operations Program. The remaining $400 million (40 percent)—which is not continuously appropriated—would be allocated to various programs in a manner that is identical to what was provided in the 2014–15 budget.

Figure 6

Governor’s Proposed Cap–and–Trade Expenditures

(In Millions)

|

Program

|

2014–15

|

2015–16

|

|

High–speed rail

|

$250

|

$250a

|

|

Low carbon transportation

|

200

|

200

|

|

Affordable housing and sustainable communities

|

130

|

200a

|

|

Transit and intercity rail capital program

|

25

|

100a

|

|

Low–income weatherization and solar

|

75

|

75

|

|

Low carbon transit operations

|

25

|

50a

|

|

Sustainable forests and urban forestry

|

42

|

42

|

|

Wetlands and watershed restoration

|

25

|

25

|

|

Waste diversion

|

25

|

25

|

|

Energy efficiency for public buildings

|

20

|

20

|

|

Agricultural energy and operational efficiency

|

15

|

15

|

|

Totals

|

$832

|

$1,002

|

Future Revenue Is Subject to Substantial Uncertainty. The amount of future auction revenue will depend on two basic factors: the number of state allowances purchased and the selling price of the allowances. Both of these factors are uncertain because they can be affected by many factors that are difficult to predict, including overall economic activity, covered entities’ costs of emission reduction alternatives, market expectations about future allowance prices, industry expectations about future statutory or regulatory changes, and the degree to which other AB 32 policies reduce emissions.

Revenue Will Likely Be Significantly Higher Than the Budget Assumes. To illustrate the range of potential revenues in 2014–15 and 2015–16, Figure 7 provides revenue estimates under three different scenarios, as well as the level of revenue assumed in the Governor’s budget. Each of our scenarios uses a different set of assumptions about the proportion of state allowances sold and the average price of allowances sold.

Figure 7

Range of Estimated Annual Cap–and–Trade Revenue

(In Billions)

|

|

Governor’s Budget

|

LAO Scenarios

|

|

Low Revenue

|

Moderate Revenue

|

High Revenue

|

|

2014–15

|

$0.7

|

$1.3

|

$1.5

|

$2.8

|

|

2015–16

|

1.0

|

2.0

|

2.3

|

4.9

|

|

Totals

|

$1.7

|

$3.3

|

$3.7

|

$7.7

|

Based on our analysis of different factors (such as prior auctions and studies that projected future allowance prices), we consider the moderate–revenue scenario the most likely of the three scenarios presented. This scenario results in revenues totaling $3.7 billion in the current and budget years—assuming that nearly all allowances offered at state auctions are sold at the minimum price established by the state (between $12 and $13 in 2014–15 and 2015–16). The low–revenue scenario assumes a smaller portion—but still a majority—of allowances are purchased at the minimum price. The high–revenue scenario assumes all allowances are purchased at an average price of $25—roughly double the minimum price. The low– and high–revenue scenarios are plausible, but less likely. Under all three scenarios, state auction revenue will likely be significantly higher than what is assumed in the budget. There is also a chance that allowance prices could approach or exceed $50, in which case revenue would be significantly higher than the high–revenue scenario.

Certain Programs Would Automatically Receive Additional Funding. To the extent revenues exceed the amount assumed in the budget, those programs that are continuously appropriated specified percentages of auction revenue would receive more funding in 2015–16 than is identified in the Governor’s budget. For example, under the moderate revenue scenario, the 60 percent of continuous appropriations in 2015–16 would be allocated as follows:

- $570 million for high–speed rail,

- $456 million for affordable housing and sustainable communities,

- $228 million for transit and intercity rail capital program,

- $114 million for low carbon transit operations.

Significant Additional Revenue Would Remain Unallocated. Under the Governor’s proposal, any unanticipated revenue in 2014–15 above the $650 million assumed in the budget, as well as 40 percent of revenue above $1 billion collected in 2015–16, would remain unallocated. For example, an additional $800 million in 2014–15 revenue and $500 million in 2015–16 revenue would remain unallocated under the moderate revenue scenario discussed above.

The Legislature could use additional auction revenue—relative to what is assumed in the Governor’s budget—in many different ways. Below, we discuss the following options: (1) waiting to spend funds until future years, (2) allocating funds to existing GGRF programs in 2015–16, and (3) allocating funds to other programs in 2015–16. We also discuss some potential advantages and disadvantages of each approach. The Legislature could adopt a combination of approaches based on its priorities.

Allocate Funds in Future Years. The Legislature could choose not to spend additional revenues in 2015–16, thereby making them available for spending in future years. By waiting until future years, the Legislature may have better information about the benefits of the various spending commitments made in 2014–15 that could help inform future spending decisions. For example, as mentioned above, the administration is required to provide the Legislature with annual reports on the status and outcomes of GGRF spending. This information could help the Legislature determine which programs are providing the greatest value. However, we caution the Legislature that it may be years before the current GGRF–funded projects are implemented and there is reliable information that can be used to adequately evaluate their effectiveness. In addition, if the Legislature elected to allocate the funds in future years, it would likely delay the benefits that could be achieved with these funds—such as GHG reductions, air quality improvements, and public health benefits.

Allocate Funds to Existing GGRF Programs in 2015–16. The Legislature could allocate additional funding in 2015–16 to programs that are currently receiving GGRF appropriations. One advantage to providing more funds to existing programs—instead of establishing new programs—is that agencies already have experience developing and administering these programs and, thus, there may be relatively little additional work needed to administer increased funding. Furthermore, the Legislature has already identified these programs as areas of priority. One potential concern with this approach, however, is that there may be diminishing returns to providing additional funding to these programs. For example, if agencies are currently allocating funds to projects with the greatest benefits per dollar spent, additional funding provided to these programs would likely be used to fund projects that provide fewer benefits per dollar spent. These additional projects may still be worth funding, but the Legislature should consider the marginal benefits of providing additional funds to these programs compared to other options.

Allocate Funds to Other Programs in 2015–16. The Legislature could fund additional programs that did not receive GGRF funds in 2014–15 and are not proposed to receive funding in 2015–16. We identified a few additional options in our report The 2014–15 Budget: Cap–and–Trade Auction Revenue Expenditure Plan. For example, the Legislature could use GGRF funds to support the development of energy storage technology. The Legislature has expressed its interest in this area and the integration of energy storage into the electricity grid. For example, the Legislature recently directed the California Public Utilities Commision (CPUC) to explore options for expanding the use of energy storage by the state’s investor–owned utilities. Energy storage has the potential to support state efforts to increase the proportion of energy coming from renewable sources, such as solar.

The Legislature should attempt to identify a cap–and–trade spending strategy that maximizes net benefits within the existing legal restrictions. The Legislature has identified a wide variety of goals it would like to achieve with the use of cap–and–trade auction revenues, including reducing GHG emissions, improving air quality and public health, and addressing inequities in disadvantaged communities. To the extent possible, the Legislature will want to have a clear understanding of how different spending options help achieve these benefits. When evaluating different spending options, we encourage the Legislature to evaluate the expected benefits relative to the benefits that would have otherwise occurred. Such a comparison is particularly important when evaluating spending options that affect GHG emissions from the capped economy. We discuss this issue in more detail below, as well as some potential strategies that may help target spending in ways that maximize net benefits—above and beyond what would have otherwise occurred.

Spending on Activities That Reduce GHG Emissions From the Capped Economy. As discussed above, the cap–and–trade program is designed to ensure California meets its 2020 GHG emission reduction targets at the least possible cost. When evaluating the benefits of spending on activities that affect GHG emissions from the capped economy—such as activities that reduce gasoline consumption, electricity consumption, or emissions from large industrial sources—the Legislature may want to consider the potential for the following effects:

- Might Not Affect Overall Emissions. The cap of the cap–and–trade program ensures total GHG emissions from the capped economy do not exceed a certain level. If the cap is limiting total GHGs, GHG reductions from one covered entity simply allows other covered entities to emit more GHGs. Therefore, spending cap–and–trade revenues on activities that reduce GHG emissions from the capped economy might not reduce overall GHG emissions. It may simply change the mix of emission reduction activities.

- Likely Leads to More Costly Emission Reduction Activities. In theory, by establishing a price on GHG emissions, the cap–and–trade program creates an economic incentive for producers and consumers to find the mix of least costly emission reductions. Spending cap–and–trade revenues on activities that reduce emissions from the capped economy likely leads to more costly emission reductions overall than simply relying on cap–and–trade. This is because it is unlikely that state expenditures would be directed at the least costly GHG emission reduction strategies. To the extent state expenditures are directed at emission reductions that are more costly than what would be achieved by the cap–and–trade program alone, the resulting mix of emission reductions would be more costly overall.

- Reduces Private Costs of Emission Reduction Activities. While spending on activities that reduce emissions in the capped sector might increase the overall cost of compliance—including public and private funds—it would reduce the private costs of compliance by subsidizing certain emission reduction activities. These reduced costs could be realized by either producers or consumers.

- Could Help Achieve Other Legislative Goals. Spending money on emission reduction activities in the capped economy could help achieve other legislative goals, such as improving air quality, improving public health, and addressing inequities in disadvantaged communities. However, similar to GHG reductions discussed above, the Legislature should evaluate how different spending options help address these benefits relative to what would have otherwise occurred. For example, spending on activities that reduce transportation emissions—both GHGs and local air pollutants—will help improve local air pollution where transportation emissions are reduced. However, those emission reductions might be at least partially offset by an increase in emissions somewhere else.

Targeting Spending to Achieve the Greatest Net Benefits. The Legislature will want to consider how to best target its spending in a way that achieves maximum net benefits, after considering some of the potential limitations associated with spending funds in the capped economy discussed above. Some of the strategies to target spending options with the greatest net benefits include:

- Spending in the Uncapped Economy. One strategy is to spend funds on activities that reduce emissions from the uncapped economy. In contrast to the capped economy, spending revenues on activities that reduce GHGs in the uncapped economy would not be offset by an increase in GHG emissions from other sources, thereby resulting in an overall reduction in emissions.

- Identifying Other Market Failures. Another strategy may be to fund GHG reduction activities that the private market fails to adequately provide, even under the incentives established by the cap–and–trade program. An example of this is energy efficiency. Some evidence suggests that the owners of existing apartment buildings might not invest in the optimal amount of energy efficiency. Since renters typically pay the energy bills, apartment building owners do not have much of a financial incentive to make energy efficiency investments that reduce utility bills. In theory, spending on energy efficiency could potentially provide low–cost GHG reductions that the private sector otherwise would not provide. However, the benefits and costs of such projects should be carefully evaluated to determine whether they provide clear net benefits.

- Prioritizing Other Legislative Goals. If spending on activities that reduce emissions from the capped economy have little or no impact on net GHGs, the Legislature may want to consider giving greater weight to some of its other goals—such as addressing concerns about disadvantaged communities or improving air pollution. However, given the legal restrictions discussed above, it should be aware of the potential legal risk associated with giving greater weight to non–GHG related criteria. We continue to recommend the Legislature consult with Legislative Counsel about the legality of different spending options.

- Offset Other Types of State Spending. The Legislature could use GGRF funds to offset spending from other sources of state funds, including special funds and General Fund. Using revenues to offset other state spending could free up state funds to be used for other legislative priorities. To the extent these other priorities provide significant benefits, this option would be worthy of consideration. For example, the Legislature could consider using the additional revenue to offset special fund spending—thereby freeing up such funds for alternate uses or allowing the Legislature to reduce the fees that are collected to support these programs. Similarly, using GGRF funds to offset General Fund expenditures would make additional General Fund dollars available for other legislative priorities. The current amount of potential General Fund offsets is unclear. However, in 2012, our office found only a handful of programs—totaling around $100 million—that could potentially meet the potential legal restrictions discussed above. (For more detail, please see our 2012 report The 2012–13 Budget: Cap–and–Trade Auction Revenues.)

On November 4, 2014, voters approved Proposition 1, a $7.5 billion water bond measure primarily aimed at increasing the supply of clean, safe, and reliable water and restoring habitat. The Governor’s budget proposes to appropriate $533 million from Proposition 1 in 2015–16 as shown in Figure 8. In a recent report, we identify key principles for implementing Proposition 1 and use these principles as the basis for a series of recommendations aimed at assisting the Legislature to ensure that the bond is implemented effectively—meaning that funding is directed towards cost–effective projects and that such projects are adequately overseen and evaluated. (For more information on Proposition 1 and our recommendations, please see our report The 2015–16 Budget: Effectively Implementing The 2014 Water Bond.)

Figure 8

Governor’s 2015–16 Proposals for Proposition 1 Bond Funds

(In Millions)

|

Purpose

|

Proposed for

2015–16

|

|

Water Storage

|

$3

|

|

Water storage projects

|

$3

|

|

Watershed Protection and Restoration

|

$178

|

|

Conservancy restoration projects

|

$84

|

|

Enhanced stream flows

|

39

|

|

Watershed restoration benefiting state and Delta

|

37

|

|

Los Angeles River restoration

|

19

|

|

Urban watersheds

|

<1

|

|

Various state obligations and agreements

|

—

|

|

Groundwater Sustainability

|

$22

|

|

Groundwater sustainability plans and projects

|

$22

|

|

Groundwater cleanup projects

|

1

|

|

Regional Water Management

|

$57

|

|

Integrated Regional Water Management

|

$33

|

|

Water use efficiency

|

23

|

|

Stormwater management

|

1

|

|

Water Recycling and Desalination

|

$137

|

|

Water recycling and desalination

|

$137

|

|

Drinking Water Quality

|

$136

|

|

Drinking water for disadvantaged communities

|

$69

|

|

Wastewater treatment in small communities

|

66

|

|

Flood Protection

|

—

|

|

Delta flood protection

|

—

|

|

Statewide flood protection

|

—

|

|

Administration and Oversighta

|

$1

|

|

Administration

|

$1

|

|

Total

|

$533

|

Extended Drought Affecting California. California entered an extended drought beginning in 2011, including the third driest year on record in 2014. Water conditions for 2015 are currently unknown since the state typically receives nearly all of its precipitation between December and April each year. However, as of January 29, 2015, the snowpack in the Sierra Nevada Mountains—which is the source of most of the state’s water in summer months—is currently at about one–fourth of average for the date.

Recent Expenditures on Drought. In response to the drought, the Legislature appropriated and the Governor approved a total of $839 million (mostly bond funds) for various drought–related activities in 2013–14 and 2014–15. Among other things, this amount included (1) $473 million to DWR for local water supply projects, (2) $66 million to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) for wildland fire suppression, (3) $41 million for the Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) to protect and monitor vulnerable fish and wildlife, and (4) $30 million for food assistance to drought–affected communities.

As of January 20, 2015, the administration had expended $234 million (27 percent) of the above $839 million. We note that the $473 million for local water supply projects is expected to be spent over multiple years as those projects are constructed. Of this amount, DWR has awarded the first round of $221 million and plans to award the remaining funding in 2015–16.

The Governor’s budget proposes additional drought–related expenditures in 2015–16. In total, the Governor requests $115 million ($93.5 million General Fund) in one–time funds across five departments. These requests—along with the prior–year appropriations—are shown in Figure 9. Specifically, the Governor’s budget provides drought–related funding in 2015–16 to the following departments:

- CalFire—$61.8 million. The budget includes $61.8 million for CalFire to continue expanded fire prevention and suppression activities, including employing seasonal firefighters longer during the fire season, increased vehicle repairs resulting from higher use, and contracts for additional firefighting aircraft. The request includes 373 temporary positions, mostly seasonal firefighters.

- SWRCB—$22.6 million. The SWRCB requests (1) $15.9 million for emergency drinking water supplies and (2) $6.7 million for emergency water rights activities (such as processing urgent changes to regulations and increasing enforcement efforts). The proposal includes 42.5 limited–term positions.

- DFW—$14.6 million. The budget proposes a total of $14.6 million to DFW for various activities. This amount includes (1) $3.3 million for emergency measures to protect fish and wildlife (such as rescuing and holding fish), (2) $3.2 million for enhanced monitoring of fish species in the Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta (Delta) and in other parts of the state, (3) $3.2 million for maintenance and upgrades of hatcheries to protect commercial salmon fisheries, and (4) $2 million to address effects on wildflife (such as mountain lions). The request includes 13 limited–term positions.

- DWR—$11.6 million. The DWR requests a total of $11.6 million for various activities. This amount includes (1) $3.8 million to coordinate the water supply and fish protection actions of multiple state agencies through DWR’s Drought Management Operations Center, (2) $2.5 million to review local agencies’ drought planning efforts and provide assistance where needed, and (3) $1.7 million to expedite water transfers.

- Office of Emergency Services (OES)—$4.4 million. The Governor’s budget proposes $4.4 million for OES to continue coordinating state and local activities associated with the drought.

Figure 9

Drought Related Appropriations

(In Millions)

|

Purpose

|

Department

|

2013–14

Actual

|

2014–15

Actual

|

2015–16

Proposed

|

|

Increased fire suppression and prevention

|

Forestry and Fire Protection

|

—

|

$66.0

|

$61.8

|

|

Emergency drinking water supplies

|

Public Health/SWRCB

|

$15.0

|

—

|

15.9

|

|

Actions to protect fish and wildlife

|

Fish and Wildlife

|

2.3

|

38.8

|

14.6

|

|

Emergency water supply activities and education

|

Water Resources

|

1.0

|

18.1

|

11.6

|

|

Emergency regulations and enforcement

|

SWRCB

|

2.5

|

4.3

|

6.7

|

|

Drought response coordination and guidance

|

Office of Emergency Services

|

1.8

|

4.4

|

4.4

|

|

Food assistance

|

Social Services

|

25.3

|

5.0

|

—a

|

|

Grants for local water supply projects

|

Water Resources

|

472.5

|

—

|

—

|

|

Flood control projects

|

Water Resources

|

77.0

|

—

|

—

|

|

Housing assistance

|

HCD

|

21.0

|

—

|

—

|

|

Grants for projects that save water and energy

|

Water Resources

|

20.0

|

—

|

—

|

|

Groundwater cleanup and sustainable management

|

Water Resources/SWRCB

|

14.0

|

9.1

|

—

|

|

Drought response and water efficiency

|

California Conservation Corps

|

13.0

|

—

|

—

|

|

Grants for irrigation improvements to save water and energy

|

Food and Agriculture

|

10.0

|

—

|

—

|

|

SWP water–energy efficiency

|

Water Resources

|

10.0

|

—

|

—

|

|

Training for workers affected by drought

|

Employment Development

|

2.0

|

—

|

—

|

|

Water conservation in state facilities

|

General Services

|

—

|

5.4

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

|

$687.4

|

$151.1

|

$115.0

|

These activities are largely a continuation of activities funded in the current year, but at different funding levels. The largest proposed decrease in funding from 2014–15 to 2015–16 is a reduction of $24.2 million for DFW, primarily because much of the 2014–15 expenditures are associated with one–time equipment purchases. The largest increase in a proposed funding level is for SWRCB, mainly due to the $15 million in new funding for emergency drinking water supplies. The administration indicates that the proposed level of funding in 2015–16 is intended to address the needs that would arise if the state receives average precipitation, a level which would likely not significantly increase or decrease the intensity of the drought.

Proposals Generally Reasonable Response to Problems Caused by Drought. Our review of the Governor’s proposals finds that they generally address significant problems that have arisen during the drought. In addition, the administration appears to have learned some lessons from its previous drought–related activities that it has incorporated in its new proposals. For example, DFW recently identified impacts to protected wildlife species—such as mountain lions—in 2014–15 and requested $2 million to address those impacts in 2015–16.

Funding Required Will Depend on Future Hydrologic Conditions. The level of funding needed to respond to the drought will depend on future hydrologic conditions. As noted above, water conditions for 2015 will be determined by the amount of precipitation that falls in the next few months. Thus, the level of resources required is uncertain at this time. The administration indicates that it intends to reevaluate these budget needs with the May Revision, when more information on water conditions will be available.

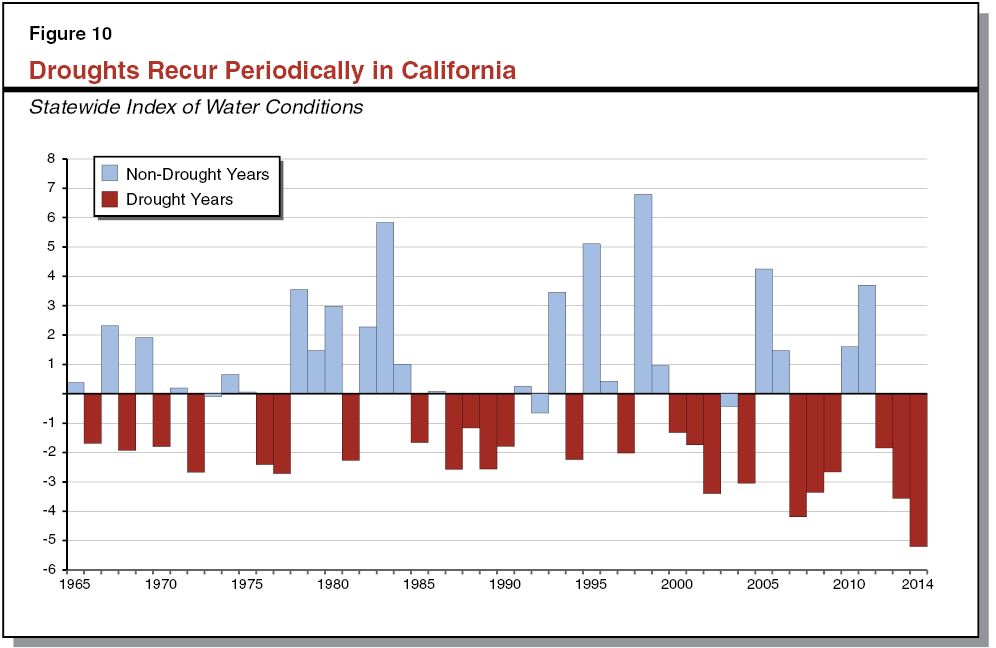

Agencies Do Not Adequately Plan for Periodic Droughts. Droughts recur periodically in California and can be expected to recur in the future. Figure 10 shows this variation in water conditions. As shown in the figure, the state experienced drought years in 24 out of the past 50 years. The severity of drought years is affected by not only the precipitation that year, but also the dryness of previous years. (Statewide water conditions index values below –1 indicate drought years.) Given periodic droughts, it is important for state and local governments to have infrastructure and planning processes in place to manage these conditions, as they do for disasters. However, many state agencies and some local agencies do not have ongoing programs and procedures in place to deal with droughts, and as a result, their drought response activities funded in recent years have been implemented as emergency measures.

Responding to the drought on an emergency basis creates several issues, including:

- Use of General Fund Instead of More Appropriate Sources. An inability to fund activities from other sources that might be more appropriate. This is because some drought activities provide benefits to private parties but are being supported by the General Fund. For example, DFW was unable to secure funding from other sources in the short time available for the monitoring of endangered species in the Delta in 2014–15. Thus, it requested General Fund for this purpose as part of the Governor’s May Revision to the 2014–15 budget, which was approved by the Legislature.

- Potentially Higher Costs for Routine Activities. Some activities may become more expensive during droughts. For example, drilling new wells in response to water supply shortages can be more expensive during droughts than at other times because of increased demand for well–drilling services.

- Delayed Progress on Other Activities. Several state agencies did not have time to hire new staff to respond to the drought and therefore redirected existing positions to meet drought needs. For example, DWR redirected 72 positions from various programs to carry out 2014–15 drought activities. According to DWR, this delayed various activities, including the development of the 2013 update to the California Water Plan.

Limited Ability to Learn From Past Drought Responses. State law requires OES—in cooperation with other relevant agencies—to develop an “after action report” following a declared disaster, such as droughts. This report describes potential improvements to the state’s response to the emergency and a description of the actions planned to implement those improvements. However, the comprehensiveness of these reports can vary, and it is unclear whether past after action reports have been helpful in responding to the current drought.

Withhold Recommendation on Drought Proposals. We withhold recommendation on the administration’s drought proposals until the administration reevaluates drought response needs at the May Revision. This will allow the Legislature to evaluate the proposals when more complete information about water conditions is available.

Administration Should Identify Changes Needed to Improve Resilience. We also recommend the Legislature pass budget trailer legislation requiring that the after action report produced at the conclusion of this drought identify programmatic changes to California’s water system that would improve the state’s resilience to dry conditions. The report should also identify funding sources to support the recommended activities, including consideration of federal funds, State Water Project (SWP) funds, and water rights funds. The report should be provided to the Legislature to inform future drought–management policies.

Some examples of potential changes the administration and Legislature could consider include ongoing monitoring and enforcement of the water rights system, planning drought operations for SWP and the federal Central Valley Project in advance of dry conditions, and comprehensively reviewing the content of local agency drought plans to assess whether they provide a feasible response. In addition, we note that the administration’s 2014 Water Action Plan includes a recommendation to streamline water transfers, in part to address droughts by making it easier for people to buy and sell water. To implement this, the Governor’s 2015–16 budget includes a separate proposal of $1.4 million from the General Fund for DWR to continue its efforts to streamline water transfers through a “water transfer clearinghouse.”

The DWR protects and manages California’s water resources. In this capacity, DWR plans for future water development and offers financial and technical assistance to local water agencies for water projects. In addition, the department maintains the SWP, which is the nation’s largest state–built water conveyance system. Finally, DWR performs public safety functions such as constructing, inspecting, and maintaining levees and dams.

The Governor’s 2015–16 budget proposes a total of $4.4 billion from various funds (mainly special funds) for support of the department. This is a net decrease of $785 million, or 15 percent, compared to projected current–year expenditures. This change is primarily due to technical adjustments to bond expenditures.

Defining Flood Risk. According to a November 2013 report by DWR, California faces significant risk from flooding. The flood risk for a given area is determined by the amount of damage (such as damage to property and loss of life) that would be caused if a flood occurred, combined with the likelihood that a flood will occur. For example, an urban area along a river might have a relatively high flood risk—even if a flood is unlikely to occur—because the area has high property values and a large number of residents would be affected if flooding happened. In contrast, a rural area might have a lower flood risk—even if a flood is more likely to occur—because property values and populations in the area are lower.

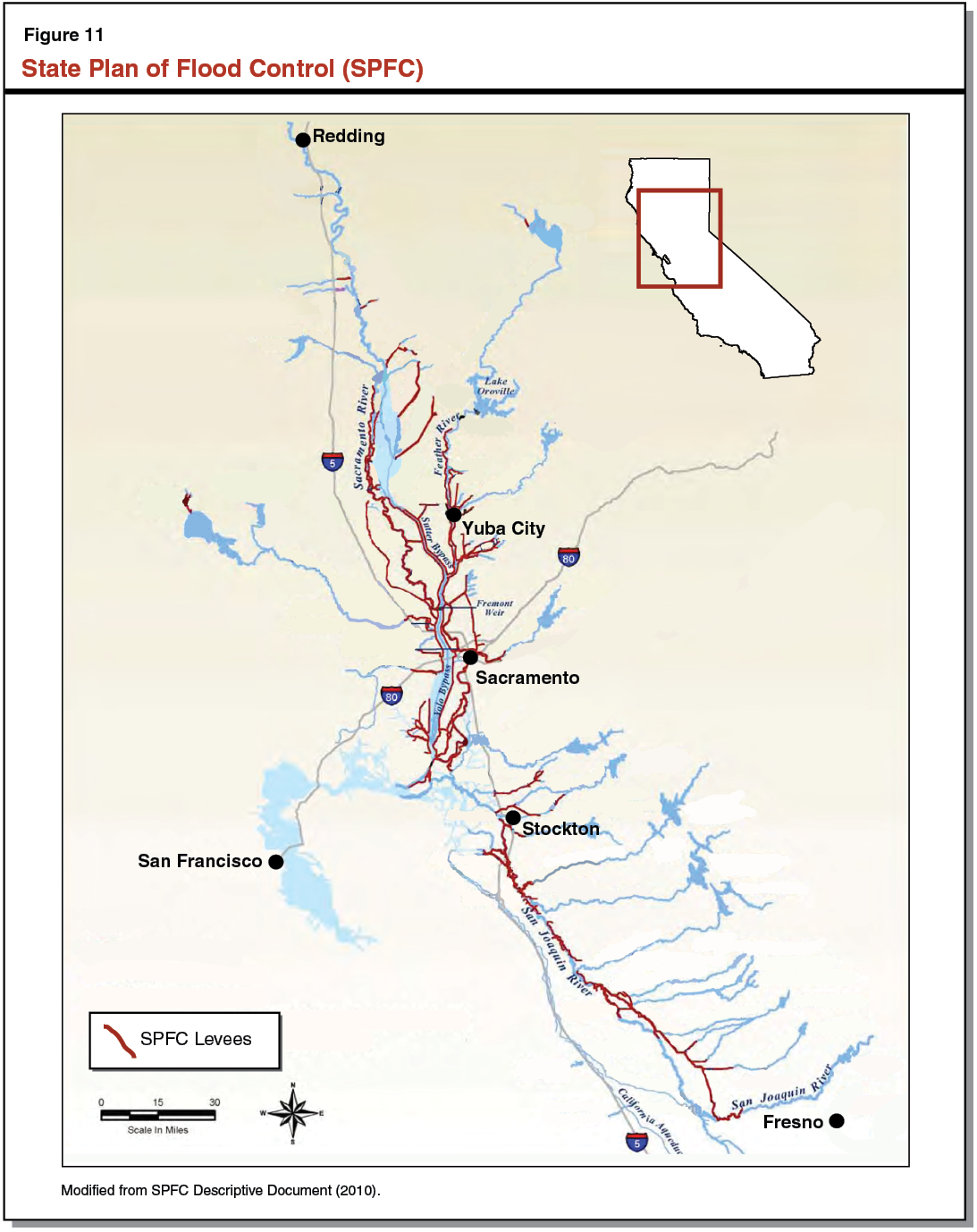

State Role in Flood Protection. Historically, most flooding has occurred in the Central Valley. The state is the primary entity responsible for flood control in this area. The State Plan of Flood Control (SPFC) is the state’s system of flood protection in the Central Valley. It includes about 1,600 miles of levees, as well as other flood control infrastructure, such as bypasses and weirs, which are used to divert water at times of high flow. Figure 11 shows the location and extent of the SPFC.

Within the SPFC, the state funds the construction and repair of flood control infrastructure. Typically, the federal and local governments also provide funding for these projects. The state also provides grants to local governments to support local levee improvements and other activities. For most levee segments, the state has turned over the operations and maintenance to local governments (primarily local flood control districts). Even though some of these local agencies have failed to adequately maintain the levees in the past, the state has been found liable for such levee failures. Outside the SPFC, the state’s role in flood management generally consists of providing financial assistance to local governments for flood control projects located throughout the state.

Voters Passed Proposition 1E. In November 2006, California voters approved the Disaster Preparedness and Flood Protection Bond Act of 2006 (Proposition 1E) in order to improve the condition of the state’s levees. Proposition 1E authorized the sale of $4.1 billion in general obligation bonds for several broad categories of flood protection activities, such as improvements to the state’s flood control system and the construction of bypasses. The measure requires (1) all funds to be appropriated by July 1, 2016, (2) the funds to be directed to projects that achieve maximum public benefits, and (3) the Governor to submit an annual flood prevention expenditure plan that includes the amount of matching federal and local funds.

Central Valley Flood Protection Plan Developed. Subsequently, the Legislature passed the Central Valley Flood Protection Act of 2008 (Chapter 364, Statutes of 2007 [SB 5, Machado]). Chapter 364 required DWR to develop a plan—the Central Valley Flood Protection Plan (CVFPP)—for reducing the risk of flooding throughout the SPFC system, including recommended actions and projects. The CVFPP was developed by DWR in 2012 and identified a total flood control funding need of $14 billion to $17 billion.

State Flood Protection Activities. The state funds several types of flood protection activities. This includes three types of state–managed capital outlay projects:

- Urban Capital Outlay Projects. These projects protect urban areas, typically by improving levees. Projects in urban areas often provide large reductions in flood risk for the protected areas because the levees protect high value property and large populations. However, the way urban capital projects have historically been constructed often negatively affect fish habitat for several reasons, such as by reducing native vegetation. Consequently, such projects often require significant environmental mitigation. The federal government often provides most of the funding for these projects because they meet certain federal criteria for reducing flood risk in a cost–effective manner.

- Rural Capital Outlay Projects. These projects protect rural areas by repairing levees and making other improvements, such as flood–proofing structures or widening floodplains. The impact of rural flood projects on fish habitat depends on how they are designed. For example, some of these projects include “setback” levees, which are built further back from the bank of the river. This connects the river to its historical floodplain, which creates additional habitat and provides good food sources for fish and other species. Because these projects reduce risk in rural areas—which do not have high populations or property values—they often do not meet the federal government’s cost–effectiveness criteria. Thus, the state typically pays over half the cost of these projects, with local governments paying the remainder.

- Systemwide Capital Outlay Projects. These projects include building or expanding existing bypasses (such as the Yolo Bypass near Davis). Bypasses significantly reduce the chance of flooding for large regions—including urban and rural areas—and improve environmental benefits for fish species that migrate through them. However, because some of the flood benefits accrue to rural areas, these projects may not reduce flood risk as cost–effectively as urban projects. The cost shares among state, federal, and local governments depend on the specific project.

The state also provides funding for other activities, including:

- Grants to Local Governments. The state provides grants to support a variety of flood protection activities at the local level. Specifically, the state funds a share of the costs associated with projects that are developed and led by local governments. This includes grant programs focused on reducing flood risk in small communities and supporting local levee maintenance.

- State Operations. The state also supports various state flood protection activities, such as updates to the CVFPP, analyses of flood risk, levee maintenance, and purchasing equipment and supplies needed to respond to flood emergencies.

Challenges to Expending Proposition 1E Funds. While the Legislature has appropriated most of the Proposition 1E funds for specific projects, only $1.9 billion of Proposition 1E funds had been expended or committed to projects as of June 2013 (the latest information available). According to DWR, this is because the state has faced some challenges in expending Proposition 1E funds. These challenges include difficulties in (1) securing funding for local and federal shares of certain flood protection projects; (2) identifying projects developed by local agencies that have gone through the required design stages and environmental reviews; and (3) securing other local, state, and federal permits needed to complete projects.

The Governor’s proposed budget for DWR includes $1.1 billion (nearly all from Proposition 1E) to support various flood control activities. As shown in Figure 12, this amount is primarily for capital outlay projects ($738 million), but also includes some funding for local assistance ($222 million) and state operations ($163 million). The proposal would appropriate all remaining Proposition 1E funding and would support 530 existing positions.

Figure 12

2015–16 Proposed Proposition 1E Appropriations

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Purpose

|

Amount

|

Percent of Total

|

|

Capital Outlay Projects:

|

$738

|

66%

|

|

In Urban Areas

|

(320)a

|

(28)

|

|

Systemwide

|

(300)

|

(27)

|

|

In Rural Areas

|

(118)

|

(11)

|

|

Local Assistance

|

222

|

20

|

|

State Operations

|

163

|

15

|

|

Totals

|

$1,123

|

100%

|

The Governor proposes to give DWR ten years to encumber the funds (commit to projects) and an additional two years to expend them. (This significantly exceeds the typical three–year appropriation for capital projects.) Unlike with prior appropriations, the proposal does not identify specific projects that would be funded. The proposal would also allow the department to transfer funds between state operations, local assistance, and capital outlay projects as it deems necessary. The administration has indicated that it will seek legislation to appropriate some funding prior to the passage of the 2015–16 Budget Act with the intent to expedite flood projects. In future years, the administration also intends to submit an annual report detailing proposed expenditures for the year and progress on past programs.

Based on our analysis, we have identified several concerns with the Governor’s Proposition 1E proposal. Specifically, the proposal (1) significantly reduces legislative involvement and oversight (particularly due to the proposed ten–year appropriation period and the lack of key information provided), (2) provides no opportunity for the Legislature to ensure that funded projects provide the best balancing of the numerous trade–offs inherent in selecting among different possible flood projects, and (3) does not address any of the underlying issues that have cost delays in completing flood protection projects in the past. Below, we discuss each of these concerns in more detail.

Significantly Reduces Legislative Involvement and Oversight. Under the proposal, the administration would be able to direct funding to currently unknown projects and shift funding away from currently planned projects without soliciting input from the Legislature or providing justification for its choices. Compared to the current budgeting practice, where the Legislature appropriates funds for specific projects in the annual budget act, the Governor’s Proposition 1E proposal would significantly limit the Legislature’s ability to direct funding to its priorities and oversee how those funds are spent. For example, the Legislature could have a particular interest in flood protection projects in certain areas, but it would not be able to ensure that funds were directed to those projects under the Governor’s proposal.

These legislative constraints are particularly problematic because the administration’s proposal lacks key information about what projects would be funded. As noted above, the proposal does not identify specific projects or even a list of potential projects that would be eligible for funding. The DWR states that it has lists of projects prioritized according to risk from flooding, but has not provided these lists for each type of activity to the Legislature. Moreover, the department has not indicated how it would prioritize among potential projects. (The DWR has provided our office with a list of potential rural levee improvements but has not confirmed that this lists all of the projects eligible for funding.) The administration also has not indicated how it decided to allocate the $1.1 billion among different types of flood protection activities. Without such information, it is impossible for the Legislature to determine whether the initial allocation of funds among the different types of activities or the specific projects that are expected to be selected are consistent with its priorities.

Provides No Opportunity for Legislature to Weigh Trade–Offs. As noted above, the CVFPP identified a total flood control funding need of $14 billion to $17 billion. Thus, Proposition 1E funding will only be sufficient to complete a small share of the recommended actions of the CVFPP. The state will have to make difficult choices about how to allocate limited dollars to projects and other activities. The choice of projects determines what outcomes are ultimately achieved by the investment of state dollars. Thus, the Legislature will want to weigh in on which projects and activities are funded in order to ensure that its highest priorities are achieved. However, the proposal does not provide the Legislature with such an opportunity. Reduction in flood risk is certainly one important factor to consider, but prioritizing among flood protection projects requires consideration of other factors and trade–offs, including:

- Ability to Obtain Cost Shares. As noted above, one obstacle to completing projects has been a lack of federal and local cost shares to fully fund projects. Given this challenge, for many projects the state will likely have to consider whether it is best to wait to secure those cost shares, even if it means delaying the completion date of projects. Alternatively, the state could consider using additional state funds to make up for unsecured local or federal shares.

- Environmental Benefits. As noted above, different flood protection projects provide various environmental benefits and harms. Environmental impacts are an important consideration for these types of projects, in part due to the potential additional costs associated with environmental mitigation.

- Achieving State–Level Benefits. According to the “beneficiary pays” principle, the costs of providing flood protection should be borne by those who benefit (such as local communities protected by levees). Therefore, state funds should be reserved for projects that provide public benefits for the state as a whole (such as environmental benefits). However, focusing state funds exclusively on projects that provide state–level public benefits could reduce the funding available for other priorities, such as reducing risk in high priority areas.

- Reducing Potential State Liability. The state could be found liable if levees fail. So, the state has an interest in funding levee improvements even where there are beneficiaries that could pay. However, this would likely reduce state funding available to support other projects.

- Funding State Operations Versus Projects. As currently reflected in the Governor’s budget, 15 percent of the requested funds would support shorter–term, operational activities such as for state staffing, feasibility studies, and levee evaluations. Some of these activities may be reasonable, but without additional information on the activities that would be funded and the basis for selecting those activities, it is difficult for the Legislature to know whether they provide a greater benefit than funding additional projects.

Does Not Address Problems That Led to Delay. The administration’s proposal for a ten–year appropriation (with two additional years to expend the funds) would allow the administration to spend funds potentially as late as 2027—21 years after the bond was initially passed and 11 years after the bond requires the funds to be appropriated. While lengthening the appropriation as proposed might allow the state to fully expend the bond funds, it does not directly address any of the problems that led to past delays. We would note that the department reports that it intends to take steps to address some challenges. For example, the department has begun work to establish a pilot program for securing necessary permits on a regional basis (instead of on a project basis). If successful, this could help streamline the permitting process for flood projects. However, other reasons for delay cited by the department, such as inability to obtain federal and local cost shares, remain unaddressed.

Under the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature would be forced to forgo its traditional oversight and appropriation authority in order to spend the remaining Proposition 1E funds for flood protection projects. However, the Legislature has other options available that could provide a better balance between continuing to fund flood protection projects and having legislative oversight. Below, we describe two such options for legislative consideration: (1) funding flood protection activities on a pay–as–you–go basis and (2) modifying the Governor’s proposal to add control and accountability measures.

Option 1: Fund Flood Protection on Pay–As–You–Go Basis. One option the Legislature has is to reject the Governor’s proposal and instead appropriate funds for flood protection activities on a pay–as–you–go basis. This means that expenditures would be paid for up front, instead of paid for through borrowing (as is done with bond financing). Funding flood control projects on a pay–as–you–go basis would allow the Legislature to exercise its traditional project approval and oversight roles through the budget process and to direct funds to its priorities. For example, the Legislature could target funding to specific projects in certain areas of concern or that meet other state goals.

In addition, pay–as–you–go funding of projects has the benefit of reducing long term General Fund spending. This is because selling bonds to finance projects requires the state to pay interest on those bonds from the General Fund. On the other hand, pay–as–you–go spending could increase costs in the near term compared to financing projects, which spreads the cost over many years. Of course, with a pay–as–you–go approach, the Legislature could choose a spending level for flood protection projects each year that balanced its flood protection goals with other legislative budget priorities.

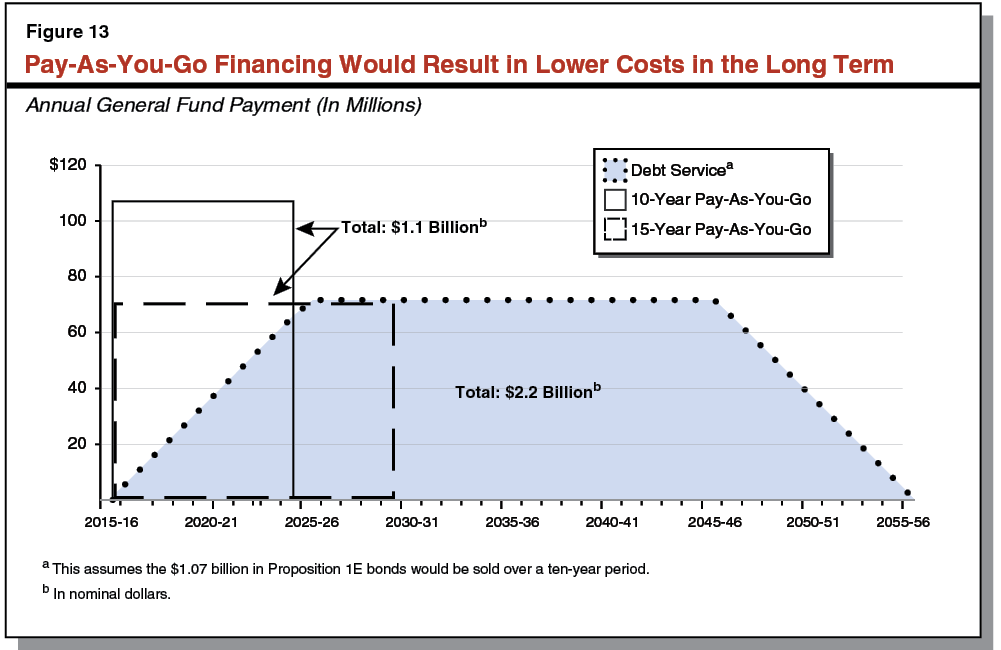

Figure 13 illustrates how costs associated with funding $1.1 billion in projects could differ under three scenarios: (1) spending the full amount on a pay–as–you–go basis evenly over the next ten years, (2) spending the full amount on a pay–as–you–go basis evenly over the next 15 years, and (3) using general obligation bonds to finance the projects. We describe the trade–offs associated with these three scenarios below.

- 10–Year Pay–As–You–Go. Under the 10–year pay–as–you–go scenario, projects would get built over the same time period as proposed by the Governor, and would cost $107 million annually over the decade. Total costs would be $1.1 billion.

- 15–Year Pay–As–You–Go. Under the 15–year pay–as–you–go scenario, it would take a few additional years to spend the full $1.1 billion, but annual costs would only be about $70 million, same as the peak level of debt–service spending under the general obligation bond scenario. Total costs would be $1.1 billion.

- General Obligation Bonds. Under bond financing, as proposed by the Governor, the state would pay debt–service costs over a 40–year period (assuming it takes ten years to sell the bonds). Those costs would increase to about $70 million annually before declining at the end of this period. Because the state would be making debt–service payments for a much longer period of time using bonds, the state would pay a total of $2.2 billion from the General Fund.

Importantly, the Legislature would also have options for pay–as–you–go funding sources including: