The Governor proposes major changes in the funding and scope of retiree health benefits earned by state employees. This report provides an overview of these benefits and assesses the Governor’s proposal to (1) begin setting aside funds to pay for their future costs through a combination of employer and nonrefundable employee contributions and (2) change the scope of retiree health benefits for future employees.

Given the significant fiscal and policy issues associated with the administration’s proposal, we recommend that the Legislature take an active role in reviewing it. We outline a series of question that we think the Legislature should consider when reviewing the administration and any other parties’ retiree health proposals, beginning with the fundamental question of how the state should approach health benefits for its retirees given the recent changes to health care stemming from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the 2012 changes to new state employees’ pension benefits in the Public Employees’ Pension Reform Act (PEPRA) of 2013 and related measures. It is possible that future state employees may not value today’s retiree health benefits as much as they cost, and therefore the state and future employees might be better off if the state made significant changes to its retiree health benefits in the future. The Legislature may wish to further consider whether the governor’s proposal:

- Funds normal costs and reduces unfunded liabilities.

- Continues the practice of pushing costs to future generations.

- Causes pressure to increase state employee compensation.

- Considers all funding sources.

- Negatively affects employee recruitment and retention.

The Governor’s proposal envisions the state and employees paying significant amounts to prefund retiree health benefits in the future. As we discuss in the report, the Governor’s approach could constrain future state fiscal flexibility and require some employees to pay for benefits they will never receive. We discuss other options the Legislature could explore to realize the long–term financial benefits of prefunding retiree health benefits without requiring employees to make contributions. These options include using debt payments already required under Proposition 2 to address a large part of the state’s retiree health costs.

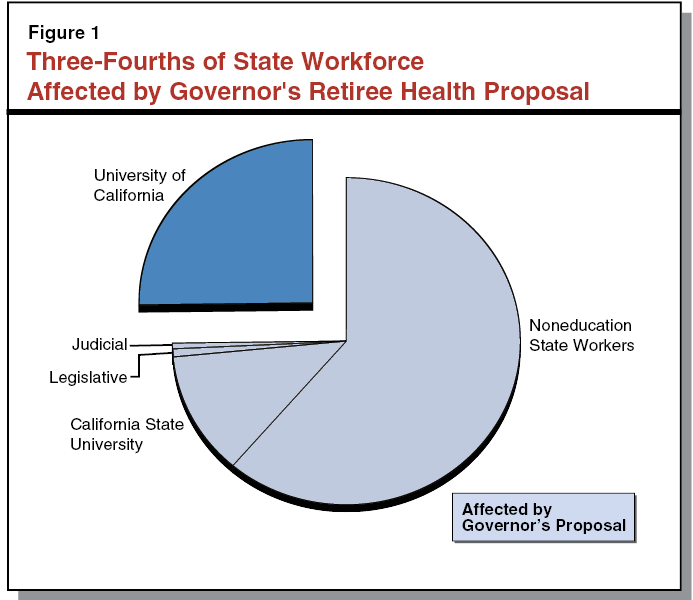

The 2015–16 budget proposes major changes to the retiree health benefits for about three–quarters of the people working for the state. As shown in Figure 1, this proposal excludes employees of the University of California (UC). Throughout the report, we use the term “state employees” to refer to non–UC state employees—the workers affected by the Governor’s proposed changes. These employees include:

- “State workers”—people working for an executive branch agency or department that administers non–higher education programs, such as the California Departments of Corrections and Rehabilitation or Transportation.

- California State University (CSU) employees.

- Employees of the Legislature and the statewide entities of the judicial branch of government.

In this report, we provide an overview of the health benefits the state offers employees during their careers and in retirement. We discuss the state’s method of funding these benefits, the state’s mounting retiree health liabilities, and the Governor’s proposal to address these liabilities. Given the wide ranging implications of the Governor’s proposal, we recommend that the Legislature take an active role in reviewing it, similar to the Legislature’s approach in recent years to addressing the retirement liabilities at the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) and California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS).

Origins and Federal Health Care Reform. For over 50 years, the state has offered health benefits to state employees, their spouses, and their dependents. While the state’s initial decision to offer these benefits was discretionary, passage of the ACA now requires the state to offer comprehensive health benefits to employees and their dependents (but not to their spouses). The benefits the state offers state employees provide somewhat greater coverage than is required by the ACA. Specifically, the ACA requires the state to provide employees health care insurance that pays for at least 60 percent of the covered health care expenses whereas the typical plan offered by the state likely pays for at least 80 percent of these costs.

State Health Plans. CalPERS administers the state’s health plans—including supplemental plans for people enrolled in Medicare. Every year, CalPERS negotiates with health care providers to establish the premiums for the plans offered to state employees. The state’s health plan premiums are divided into three tiers: single–party (only the state employee is covered), two–party (employee plus one dependent), and family coverage (employee plus two or more dependents). Medicare supplemental plans have significantly lower premiums than the health plans available to people not enrolled in Medicare.

State Contribution for Employee Health Premiums. The state pays a large share of state employee health premiums. Figure 2 shows the average premium costs and the amount of money the state contributes for these health benefits. The state’s contribution is determined through a two–step process:

- Calculate Average Premium Cost. The state identifies the four health plans with the highest enrollment of state employees and calculates a weighted average of the premiums for these plans.

- Apply Contribution Rate. For most state employees, the state pays 80 percent of the average premium cost for the employee and 80 percent of the average additional costs for his or her dependents. This is known as the “80/80” formula. For employees at CSU, the state pays a higher amount—100 percent of the average premium cost for the employee and 90 percent of the average additional premium costs for dependents, the “100/90” formula.

Figure 2

2015 Monthly Health Premium Costs and State Contributions

|

|

Single–Party

|

Two–Party

|

Family

|

|

Average premium cost

|

$655

|

$1,312

|

$1,711

|

|

State contribution formulaa

|

|

|

|

|

80/80

|

$524

|

$1,050

|

$1,368

|

|

100/90

|

$655

|

$1,246

|

$1,605

|

Employee Responsibilities for Health Premiums. An employee’s share of health premium costs depends on the health plan in which the employee enrolls. For example, an employee who receives the state’s 80/80 contribution for family health coverage receives a monthly state contribution of $1,368. If the employee enrolls in the most popular health plan among state employees—offered by Kaiser Permanente—the employee pays about $278 each month, or about 17 percent of the total premium cost. Comparing the most and least expensive in–state health plan premiums available to state employees, the employee would pay about 30 percent of the total premium cost for the most expensive health plan and less than 5 percent of the total premium cost for the least expensive health plan. Employees may pay additional sums for health care copays and deductibles.

State and Employee Costs Have Grown Significantly. In 2013–14, the state’s cost for these health care premiums was about $2 billion. On a per employee basis—after controlling for general economic inflation—the state’s premiums nearly doubled between 2001–02 and 2013–14. In some years during this period, average premium costs increased by more than 10 percent. Growth in these costs has slowed in recent years, but has still outpaced inflation in the broader economy. The state’s experience over the past 15 years is similar to that of most large employers across the nation that provide health coverage to employees. The trend of rising health insurance premiums is largely attributed to increased health costs resulting from physician and hospital charges, use of health care services, new technologies, prescription drugs, an aging population, unhealthy lifestyles, and other factors.

Because (1) employees pay a share of premium costs and (2) this share has increased pursuant to labor agreements (referred to as memoranda of understanding, or MOUs), employee costs also have increased considerably over the past 15 years.

Origins and Federal Health Care Reform. California has provided health benefits to retired state employees since 1961. The health plans available to retired state employees are the same plans available to active employees, including supplemental plans for people enrolled in Medicare. Unlike the state’s responsibility under federal law to provide health benefits for active employees, the ACA does not mandate that the state provide health coverage to retired employees or their dependents.

State Contributions for Retiree Health Premiums. Since 1978, the maximum contribution available to retired state employees has been the 100/90 formula discussed earlier. Retired state employees now generally are eligible to receive this contribution after 20 years of state service. (Retired employees with ten years of state service receive 50 percent of this amount, increasing 5 percent annually until the 100 percent level is earned.) Most state retirees receive the full 100/90 contribution. About two–thirds of them are enrolled in Medicare and a state–sponsored Medicare supplemental plan, the rest are enrolled in one of the plans offered to active employees.

Benefits Paid as Costs Incurred. The state has set aside virtually no money to pay for the future cost of retiree health care. Instead, the state funds the cost of each employee’s retiree health benefits on a pay–as–you–go basis after the employee retires.

Pay–as–You–Go Costs Growing Significantly. Between 2000–01 and 2013–14, the state’s adjusted costs for retiree health benefits tripled from about $500 million to $1.5 billion. The state’s costs are expected to increase to $1.8 billion by 2015–16. The largest contributing factor to the rapid growth in these costs is the rising cost of health premiums discussed earlier. A secondary cause of the increase is the growing number of people receiving this benefit as more employees retire and people live longer. Between 2000–01 and 2015–16, for example, the number of state retirees receiving this benefit is expected to have increased by 74 percent from 108,044 to more than 188,000.

Prefunding Retiree Health Care Costs. For a few state worker groups—highway patrol officers, doctors, and maintenance workers—the state and employees have started to partially prefund retiree health benefits. These contributions were established through MOUs and are considered assets of the employer—meaning that employees are not entitled to withdraw any of these funds. In 2015–16, the state is expected to contribute $54 million and employees are expected to contribute $18 million for this purpose. In total, the administration assumes that the prefunding trust fund will have a balance of $164 million at the end of 2015–16. This amount is considerably less than the amount of money actuaries estimate is needed to fully prefund the benefits earned to date by participating employee groups. As described more fully in the nearby box, the most recent actuarial valuation released by the State Controller’s Office determined that the total unfunded liability resulting from retiree health benefits earned by all current employees and retirees is about $72 billion.

Each year, to comply with requirements set forth by the Governmental Accounting Standards Board (GASB), the State Controller’s Office releases the state’s official actuarial valuation of retiree health benefits. The calculations reported in the valuation are prepared by professional actuaries and are consistent with GASB accounting standards and generally accepted actuarial principles and practices. The valuation estimates the state’s existing unfunded liability under the current pay–as–you–go structure and the annual costs to address this liability going forward.

Existing Unfunded Liability. Under the current pay–as–you–go system, the state has set aside less than $200 million to pay for retiree health benefits that have been earned to date by current employees and retirees. The actuaries estimate that the value of these benefits as of June 30, 2014 (in today’s dollars) is about $72 billion.

Annual Costs to Address Liability. The actuaries estimate that it would cost the state about $4 billion in 2015–16 to begin addressing retiree health liabilities: (1) $2.7 billion to retire the unfunded liability over 30 years (including making annual benefit payments to current retirees) and (2) $1.3 billion to prefund benefits earned that year by current employees. This approach would increase the state’s annual costs by about $2 billion (in today’s dollars), compared to the current pay–as–you–go system.

Are Retiree Health Benefits Guaranteed? In some cases, retirement benefits are obligations protected under state and federal contract law. There arguably is some ambiguity as to (1) whether retiree health benefits offered to California state employees are contractual obligations of this type and (2) if so, the extent to which these benefits are protected from modifications. To the extent these benefits are guaranteed contractual obligations, the state’s ability to modify the benefit for current or future retirees already employed by the state—such as reducing the state’s premium contributions, increasing copays or deductibles, or reducing the range of services covered by state plans—likely is constrained. There are no limitations on how the state may modify or change retiree health benefits for future employees.

The Governor proposes major changes to the funding and scope of retiree health benefits. The changes affect current and future state employees, but not former state employees who already are retired when these changes are implemented.

Pay–as–You–Go Payments Continue. For about the next 30 years, the state would continue paying for retiree health premiums as these costs are incurred. State costs would grow as health care costs are expected to increase faster than general inflation and people are expected to live longer. By the 30th year, the administration estimates that the state’s annual pay–as–you–go costs would exceed $7 billion (in today’s dollars).

Prefunding Benefits Begins. The Governor’s proposal would establish a “standard” that state employees and their employer share the costs to prefund retiree health benefits. Specifically, employees and the state each would pay half of the amount of money actuaries estimate is needed to be invested to pay for these future obligations. Under this concept, employees and the state each would contribute funds equal to about 3 percent of pay. This money would be put into a preexisting CalPERS trust fund, invested, and allowed to grow for the next 30 years. The trust fund’s assets would be considered the state’s assets—state employees would not be entitled to withdraw any of the money they contribute to the fund. Although the fund is designated as a prefunding trust fund, no money would be withdrawn from the fund to pay for retiree health benefits until about 2046–47. Instead, all payments for these costs would continue to be funded on a pay–a–you go basis (as described above). The 2015–16 proposed budget does not identify resources to pay the state’s share of this prefunding plan.

Funding Structure Established Through Collective Bargaining. As the box on the next page explains, compensation for most nonmanagerial state workers and CSU employees is established through collective bargaining between management and employee representatives. To facilitate this negotiation, employees are organized into bargaining units and represented by unions. State workers are organized into 21 bargaining units and CSU employees are organized into 12 bargaining units. Under the Governor’s proposal for employees subject to collective bargaining, the employer and employees’ contributions to the trust fund would be established through the collective bargaining process and phased–in as existing MOUs expire. The administration then would extend these contribution requirements to state workers excluded from collective bargaining. The administration’s proposal does not specify how the new contribution requirement would be established for other state employees: CSU employees excluded from collective bargaining, legislative staff, and judicial employees.

Collective bargaining is a process through which employees and employers negotiate terms and conditions of employment. Elements of compensation for most state employees are established through the collective bargaining process. Some state employees—such as managers and supervisors, legislative branch employees, and judicial branch employees—are excluded from the collective bargaining process. Employers—the Governor or the California State University (CSU) Board of Trustees, in the case of executive branch employees—have significant authority to establish terms and conditions of employment for employees excluded from the collective bargaining process. The Legislature established the collective bargaining process for state workers and CSU employees through two laws discussed below.

Ralph C. Dills Act. The Dills Act applies to executive branch state employees who work for one of the state’s departments or agencies that administer non–higher education programs. These employees often are referred to as “state workers.” About 85 percent of state workers are rank–and–file employees who are organized into 21 bargaining units represented by unions in the collective bargaining process. The Governor—represented by the Department of Human Resources—negotiates terms and conditions of employment with employee unions. The product of these negotiations is a labor agreement referred to as a memorandum of understanding (MOU). The Legislature must ratify an MOU before it goes into effect. (See our new State Workforce website for additional information about the collective bargaining process for state workers and analyses of MOUs submitted to the Legislature.)

Higher Education Employer–Employee Relations Act (HEERA). The HEERA applies to state employees who work for the University of California (UC) or CSU. Faculty and nonmanagerial staff are represented by unions who negotiate with representatives of their respective institutions or university systems. Before an MOU goes into effect, the governing board of the respective university must ratify the agreement. The Legislature typically does not have a direct role in this process unless an MOU results in the CSU or UC requesting an appropriation or change in statutes.

The Governor’s proposal would make two significant modifications to the retiree health benefits earned by employees first hired after January 1, 2016. These proposals would reduce the state’s costs for future employees’ retiree health benefits.

Employees Work Longer to Receive Maximum Contribution. Future employees would need to work five years longer to be eligible for retiree health benefits. Specifically, employees hired after 2015 would need to work with the state for 15 years to receive 50 percent of the maximum contribution and 25 years to receive 100 percent of the maximum contribution.

Maximum Contribution Linked to Benefits Received During Career. The administration proposes tying a retiree’s maximum state health contribution to the formula they were under as active employees. Specifically, employees who receive state health benefits under the 80/80 formula would receive retiree health benefits under the same formula.

In recent years, the Legislature and administration have taken significant steps towards addressing the state’s unfunded budget liabilities. The state’s retiree health benefit program constitutes the state’s last major liability that needs a funding plan. The longer the state waits to address this liability, the larger the problem and the more expensive any solution will become. The administration’s proposal aims to (1) address this liability by establishing a prefunding plan through collective bargaining and (2) reduce state costs going forward through benefit scope changes for future employees.

Like any retirement policy change, the proposed retiree health funding plan is complex and has broad implications over a time horizon that spans the lifetimes of current state employees, retirees, and their dependents. The Governor’s proposal raises some very difficult questions relating to:

- The purpose of this benefit.

- The distribution of costs across generations.

- The need for administrative flexibility to respond to this benefit’s escalating and unpredictable costs.

- The long–term effect requiring employees to make nonrefundable contributions could have on employee compensation, recruitment, and retention.

In contrast to the active role the Legislature played in recent years reviewing proposals to address retirement liabilities at CalSTRS and CalPERS, the administration assumes that the Legislature will play a minor role in developing the state’s policy to address its retiree health liabilities. Specifically, under the Governor’s proposal, the new policy would be established through (1) collective bargaining (in the case of most state workers and CSU employees) and (2) administrative actions (for most other state employees). Traditionally, these processes have been used to resolve a narrow range of employee compensation issues (such as determining pay increases, the state’s contribution towards employee health benefits, and overtime rules) and the Legislature has given the administration significant flexibility in their use. In the case of collective bargaining with state workers, for example, the Legislature typically has no information on the elements of a proposed MOU until it receives a tentative agreement for ratification (often about two weeks before the end of a legislative session or the June 15th budget deadline).

In the case of CSU employees, judicial employees, and state workers excluded from the collective bargaining process, the Legislature typically has no role in establishing their employee compensation or policies except in cases when an appropriation or a change in statute is necessary. Under the Governor’s proposal, therefore, the Legislature seemingly may be closely involved in setting retiree health funding parameters for only one group of employees: legislative staff.

Any policy to address the state’s retiree health liabilities is too important for the Legislature not to be an active and informed participant in its development. We recommend the Legislature give this issue at least the same level of review as it gave the development of plans to address the CalPERS and CalSTRS retirement liabilities. Therefore, we recommend the policy committees of the Legislature hold hearings to discuss the Governor’s proposal—as well as other options to address retiree health liabilities—with actuaries, employee groups, policy experts, and the public. We further recommend that the Legislature not approve a funding plan until it has had an opportunity to review the plan and a written evaluative report of it prepared by a professional actuary.

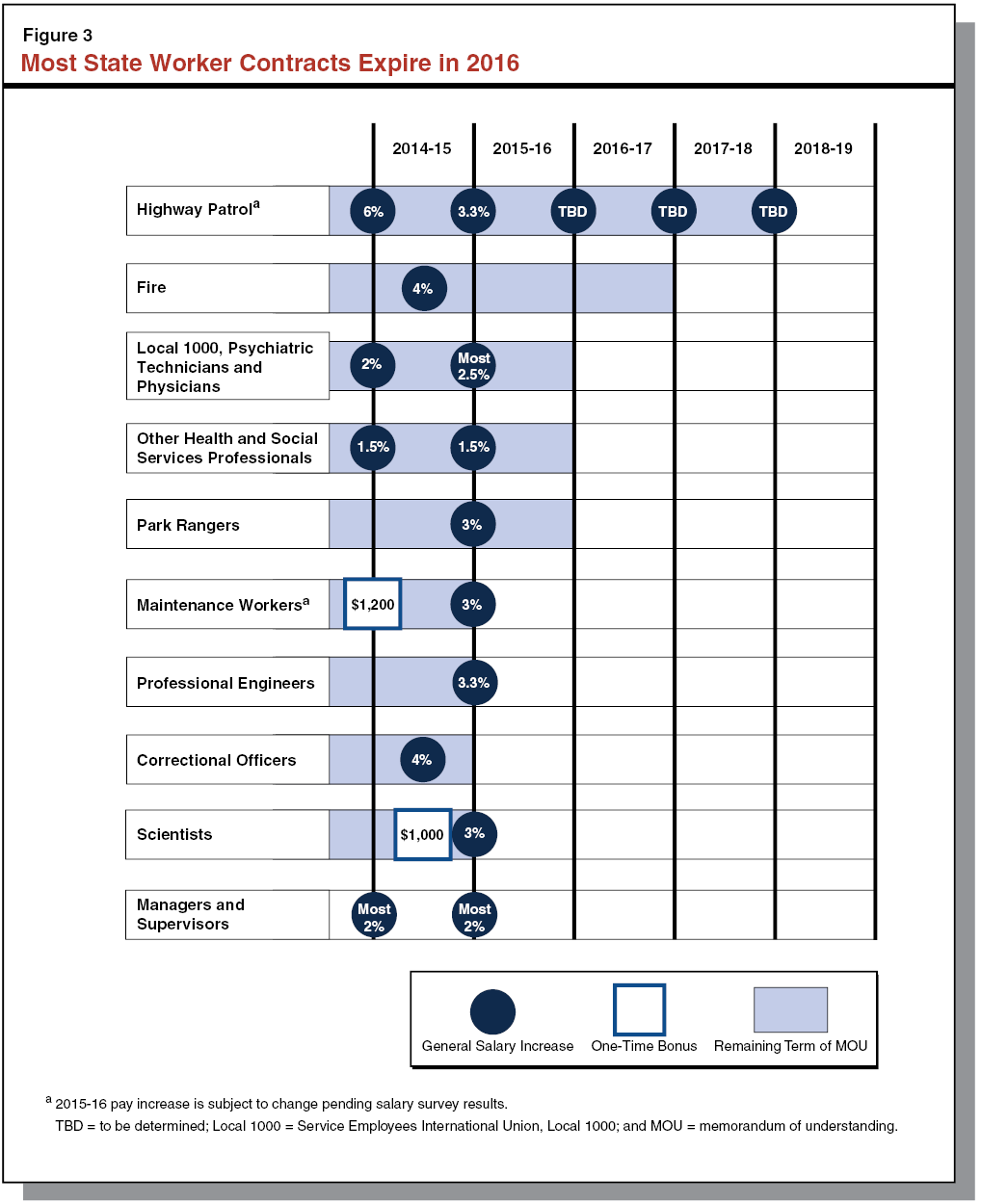

We acknowledge that subjecting the Governor’s proposal to deliberation could delay the plan’s implementation—possibly by as much as a year. We think, however, it is more important to get the plan right than to rush into a prefunding plan just to have it in place in 2015–16. This is particularly true given that, under the Governor’s implementation schedule, relatively few employees likely would be included in the prefunding plan in 2015–16. This is because (1) as Figure 3 shows (see next page), MOUs with most state worker groups are not scheduled to expire until 2016 and (2) Most CSU contracts do not expire until 2016 or 2017. (Go to our new State Workforce website for additional information about the collective bargaining process for state workers and analyses of MOUs submitted to the Legislature.)

The Governor’s retiree health benefit proposal raises many questions, ranging from (1) fundamental issues related to the value of the benefit to new hires and the purpose of an employee share of cost to (2) practical and legal questions related to potential pressures to increase wages and the ability of the state to modify retiree health benefits in the future. To facilitate a wide ranging discussion of the Governor’s proposal—as well as other proposals to address retire health benefit liabilities—we discuss these matters below.

Should California Change Its Benefit Package for Future Employees? The Governor builds his retiree health proposal on the assumption that the state would continue to offer retiree health benefits to future employees. Before examining the details of any funding proposal, the Legislature should first consider this fundamental premise. Ultimately, the design of the state’s retiree health funding model would be very different if the state offered future employees a compensation package that did not include retiree health benefits, but offered instead—for example—increased salaries or contributions to a supplemental retirement plan that the employee could use in retirement to purchase insurance (or for other purposes).

There is no single best way to design a state employee compensation package. In any such package, there exists a tension between providing valuable benefits that attract and retain qualified employees and minimizing costs to the employer. The state’s retiree health benefit was added to the list of state benefits more than a half century ago in an era before the federal government created the Medicare program and implemented the ACA. At that time, retired state employees were at risk of losing health care coverage—either because they (1) could not afford to purchase insurance or (2) had preexisting health conditions and could be denied coverage by insurance companies. Because the state’s retiree health program ensures that state employees have access to affordable health coverage in old age, these benefits historically have been a highly valued element of state employee compensation. In today’s environment, however, it is possible that prospective employees might place a lower value on these benefits because they (1) are more likely to retire later in life under the pension formulas established by PEPRA—closer to when they are eligible for Medicare—and (2) can purchase health insurance on the Exchange, sometimes with subsidies, prior to becoming eligible to receive Medicare benefits. Before California builds a funding model to pay for this benefit for decades to come, the Legislature should consider whether this benefit should continue to be a part of the state employee compensation package for new hires. If prospective employees do not value this benefit as much as it costs, the state and the new employee might be better off if the state offered future employees an alternative form of compensation.

Does the Proposal Fund Normal Costs and Reduce Unfunded Liabilities? A fundamental principle of public finance is that costs should be paid the year in which they are incurred. We think the primary tenant of any retiree health plan should be to pay the amount of money that actuaries estimate is necessary—combined with future investment returns—to pay for benefits earned by employees in that year. This amount of money is referred to as the “normal cost.” Secondary to paying normal cost, a plan should establish a payment schedule to reduce the existing unfunded liability for benefits earned to date by current state employees and retirees.

While the administration has not provided an actuarial evaluation of its proposal, it indicates that it would fully fund normal cost and eliminate unfunded liabilities in 30 years. We note that the administration’s proposal hinges on state employers’ success in establishing—through the collective bargaining process—a major new prefunding revenue stream from their employees. The PEPRA included a similar assumption that all state employers would negotiate with current employees to pay half the normal cost for pensions, but payments of this magnitude have not been instituted for a large segment of the state workforce.

Will the Proposal Cause Pressure to Increase Compensation? The Governor’s proposal establishes a standard that state employers and employees split equally the normal cost of retiree health benefits earned each year. This level of cost sharing reduces the average employee’s take–home pay by about 3 percent. Requiring employees to make these contributions towards retiree health benefits inevitably would create pressure for state employers to provide offsetting pay increases. (We note, for example, that when the state increased state worker contributions to pay for pension normal cost recently, the state provided most affected employees a dollar–for–dollar offsetting pay increase.) Employee pay increases, in turn, drive up state (1) annual costs for salary–driven benefits—Social Security, Medicare, and pension benefits—so that a $1 pay increase for the typical state worker increases state costs by about $1.34 and (2) long–term pension obligations as employees’ pensions are based on their final compensation levels. If the state provided a dollar–for–dollar offset to all employees—or even a 75 cents–on–the–dollar offset—the state’s costs for retiree health prefunding and increases in pay and salary–driven benefits would be more than total retiree health normal costs. That is, it would cost the state more to “share” normal costs than to pay them without an employee contribution.

Are All Funding Sources Considered? Given the magnitude of retiree health liabilities, the state should consider using all available funding sources to pay normal cost and reduce the unfunded liability. The administration indicates that the state’s costs for its funding proposal would be proportionately spread across all funds (General Fund, special funds, and federal funds). At the same time the Legislature considers retiree health funding sources, the Legislature also should consider the extent to which these funds could absorb new costs without requiring revenue adjustments or cuts to other programs supported by the funds. Because the Governor did not include any resources in his 2015–16 budget to pay the employer’s share of normal cost for his retiree health care proposal, the state would need to redirect about $100 million (mostly from the General Fund) to pay half the normal cost for employees whose labor contracts expire this year. The state’s costs would grow to about $600 million annually upon full implementation. Some special funds may have difficulty redirecting funds to pay their share of normal cost, now or in the future.

The administration does not consider using money available under Proposition 2 as a retiree health funding source. We describe Proposition 2 in the nearby box. As we explain in Chapter 4 of our November 2014 report, The 2015–16 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook, we think addressing retirement–related liabilities—including those related to retiree health—should be considered as one possible use of the resources available under Proposition 2.

Proposition 2, approved by voters in November 2014, is highly complex and significantly alters how the state saves money in its budget reserves and pays down debts. For a discussion of the measure, refer to Chapter 4 of our November 2014 report, The 2015–16 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook.

Sets Money Aside to Pay Existing Debts. Proposition 2 requires the state to pay a specified amount of money each year towards existing debts for at least the next 15 years. Proposition 2 could result in roughly $15 billion to $20 billion (in today’s dollars) being used to pay down state debts over the next 15 fiscal years. The law specifies the types of debts that are eligible to be paid using Proposition 2 money and includes budgetary liabilities like paying down loans to the General Fund from special funds and unfunded retirement liabilities. In 2015–16, the budget assumes that Proposition 2 provides $1.2 billion to pay down debt.

Governor Proposes Using Bulk of Proposition 2 to Pay Back Special Fund Loans. The Governor’s 2015–16 budget proposes using the money available under Proposition 2 to pay down $965 million in special fund loans and $256 million in prior–year Proposition 98 costs known as “settle up.” These actions reduce the outstanding amount of special fund loans and Proposition 98 settle up to $2.1 billion and $1.3 billion, respectively.

An Alternative Use of Proposition 2: Paying Down Retirement Liabilities. As we discuss in the November report, we recommend that the Legislature invite the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, California State Teachers’ Retirement System, University of California, and others to respond with proposals for using Proposition 2 funds to address one or more of the state’s large retirement–related debts over the next 15 years. One viable option for the Legislature to consider is to use Proposition 2 money to start paying down the $72 billion unfunded liability for retiree health benefits.

Will the Proposal Reduce the State’s Long Term Fiscal Flexibility? As we discussed earlier, there arguably is some ambiguity regarding the extent to which retiree health benefits are an obligation protected under state and federal contract law. If state employees are required to prefund retiree health benefits based on the current benefit design, these payments could be viewed as increasing employees’ contractual rights to receive these same benefits when they retire. If so, the state would have less flexibility to redesign state health plans in the future to reduce costs—for example, modifying state health plans to offer less coverage for particular procedures or to require higher copays or deductibles. To maintain legislative flexibility, there would need to be laws or agreements providing explicit disclaimers preserving the state’s legal interests in this regard.

Would the Plan Affect Employee Recruitment or Retention? Requiring current employees to make contributions towards retiree health benefits reduces employees’ take home pay. This, in turn, could make it more difficult for the state to recruit employees or retain certain employees. Younger people, for example, might find state employment less attractive because they would be required to contribute about 3 percent of pay for a benefit that they receive only if they work for the state for at least 15 years. (As discussed earlier, people leaving state employment before that time would not be entitled to a return of any funds they contributed.) Older employees, conversely, might retire earlier than they would otherwise. This is because, in retirement, these employees would not be required to make payments towards prefunding the benefit.

Should Employees Make Contributions to Prefund Retiree Health Benefits? The administration proposes that state employers and employees each pay half of the annual normal cost that actuaries determine is necessary to prefund retiree health benefits. If the state did not increase pay to offset these employee costs, this proposal would place on employees a significant share of the cost to prefund these benefits—more than $600 million each year. At the same time, as we discuss below, the administration’s approach could (1) constrain future state fiscal flexibility and (2) require some employees to pay for a benefit they never receive. To avoid these issues, the Legislature could explore other options that realize the long–term financial benefits of prefunding retiree health benefits without requiring employees to make contributions. These options include using money available under Proposition 2 to pay the full annual normal cost of these benefits.

- Constrain Future State Fiscal Flexibility. Requiring employees to pay half of the normal costs of retiree health benefits might be interpreted as establishing a contractual obligation that restricts the state’s ability to modify these benefits. To the extent that this occurred, the cost sharing structure would expose the state’s budget to financial risk because (1) health costs likely will continue outpacing general economic inflation and (2) the state may not be able to reduce its future costs through benefit modifications.

- Employees Pay for a Benefit Some Never Receive. The administration’s proposal requires employees to make nonrefundable contributions to prefund retiree health benefits. Employees leaving state service before they have worked long enough to be eligible for retiree health benefits would receive no benefit for their contributions.

Would a More Traditional Amortization Schedule Reduce Future Budgetary Pressure? When an employer has an unfunded retirement liability—meaning that the value of benefits earned to date by employees and retirees exceeds the assets on hand to pay these benefits—actuaries commonly develop an amortization schedule to eliminate the liability over time. Typically, the amortization schedule is fairly level—analogous to the mortgage payments many homeowners make over 30 years until the cost of their home is paid in full. The payment schedule proposed by the Governor is very different: instead of costs remaining flat, costs escalate rapidly. Under the Governor’s plan, the state’s cost in year 30 (in today’s dollars) is more than triple the state’s costs during the first few years. This amortization schedule reduces cost pressures in the short term, but would require the Legislature to make significant budgetary cuts or revenue increases in the future. Adopting an amortization schedule that spreads these costs more evenly across time could make it easier for future legislators to budget these costs.

Health benefits for retired state employees constitute a large and growing cost for the state of California. With limited exception, the state does not put money aside to pay for future retiree health costs. Instead, the state pays these costs as they are incurred on a pay–as–you–go basis. The state’s retiree health benefit program constitutes the state’s last major liability that needs a funding plan. As part of his 2015–16 budget, the Governor proposes one approach to address retiree health liabilities through the collective bargaining process. We recommend that the policy committees of the Legislature hold hearings to discuss the Governor’s proposal—as well as other options to address retiree health liabilities—with actuaries, employee groups, policy experts, and the public. While these deliberations could delay a prefunding plan’s implementation, we think it is important to get the plan right.