California’s state and local governments levy a tax on retail sales of tangible goods. This tax has two parts:

- Sales Tax on Retailers. When California retailers sell tangible goods, they generally owe sales tax to the state. Retailers typically add sales tax to the price they charge customers and show it as a separate item on sales receipts.

- Use Tax on Buyers. State law requires buyers to pay a use tax on certain purchases of tangible goods if the retailer does not pay California sales tax. Some internet purchases from out–of–state retailers fall into this category. The use tax rate is the same as the sales tax rate.

This report begins with an overview of California’s sales and use tax. It then provides more detail about which transactions are subject to this tax, the variation in tax rates across the state, the distribution of revenue among state and local governments, and revenue growth over the last few decades. For simplicity, we refer to the state’s combined sales and use tax as the “sales tax.”

The amount of sales tax generated by a sale depends on the tax rate and the dollar value of the goods sold. Figure 1 shows how the sales tax is calculated if a retailer sells five books costing $20 each and the tax rate is 8 percent. As discussed later in this report, California’s sales tax rate varies across cities and counties, ranging from 7.5 percent to 10 percent. The state’s average rate is 8.5 percent.

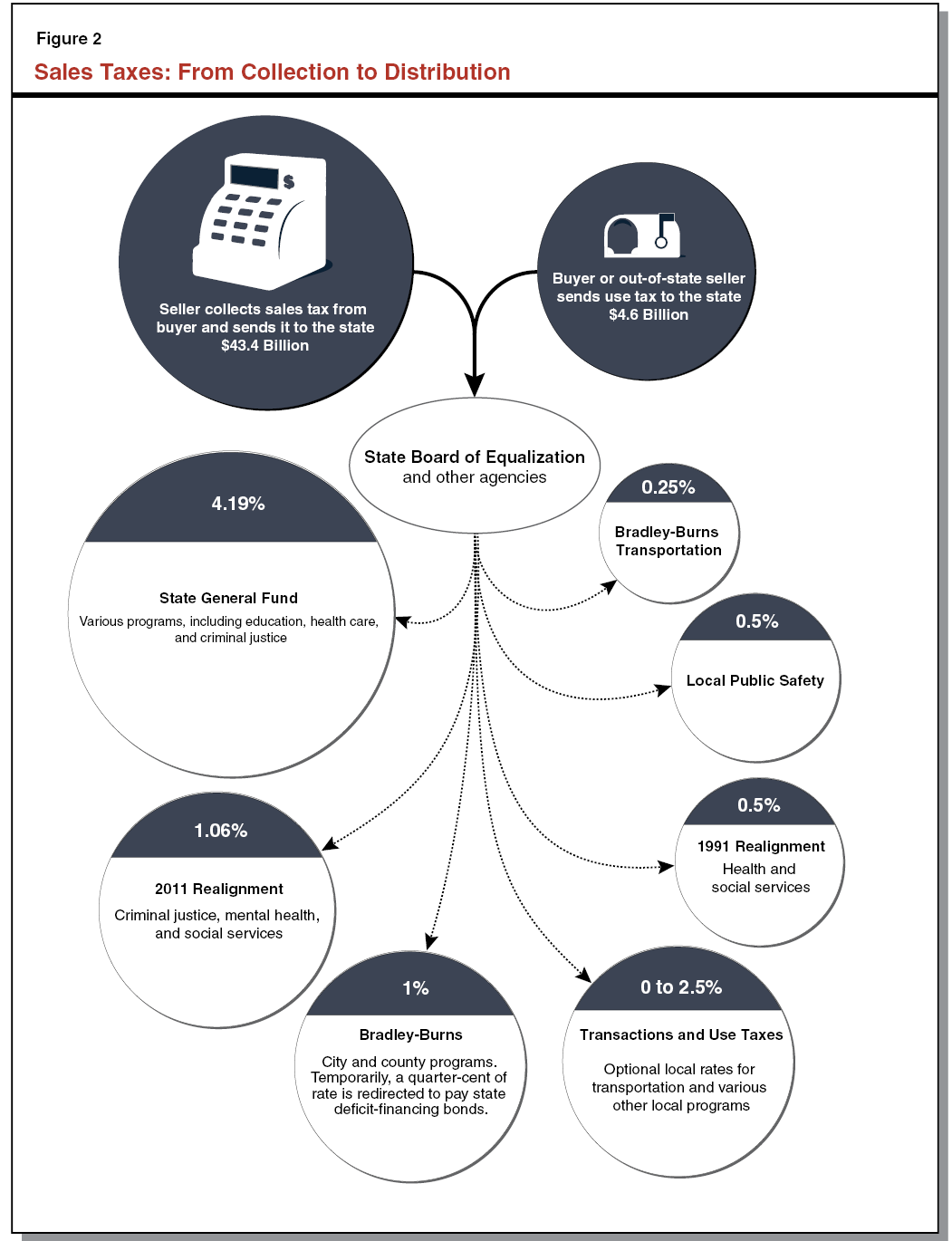

In 2013–14, buyers and sellers of tangible goods paid $48 billion in sales tax, equivalent to roughly $1,300 for every resident of California. The State Board of Equalization (BOE) is the primary entity responsible for collecting and administering the tax. Other agencies are also involved in use tax collection: the Department of Motor Vehicles collects use tax on private sales of used vehicles, and the Franchise Tax Board collects use tax reported on personal income tax returns.

Most Sales Tax Revenue Available for General Purposes. After the state collects sales tax revenue, it allocates the money to various state and local funds. As shown in Figure 2, roughly half—collected from an approximately 4.2 percent rate—goes to the state’s General Fund and can be spent on any state program, such as education, health care, and criminal justice. Another 1 percent, known as the Bradley–Burns rate, goes to cities and counties for general purposes. (As described in the box Cities Compete for Bradley–Burns Revenue later in this report), the state has temporarily reduced this rate to 0.75 percent, replacing the reduced local government revenues with other revenues. The Bradley–Burns rate will return to 1 percent by 2016.) Additionally, some local governments levy optional local rates—known as Transactions and Use Taxes (TUTs)—and a small portion of these funds are used for general purposes.

Rest of Sales Tax Revenue Used for Specified Purposes. Four sales tax funds have uniform state rates and support specified programs—an approximately 1.1 percent rate for 2011 realignment (county–administered criminal justice, mental health, and social service programs); a 0.5 percent rate for 1991 realignment (county–administered health and social services programs); a 0.5 percent rate for city and county public safety programs pursuant to Proposition 172 (1993); and a 0.25 percent Bradley–Burns rate for county transportation programs. In addition, most of the revenue from the optional TUTs is used for specified purposes, primarily transportation programs.

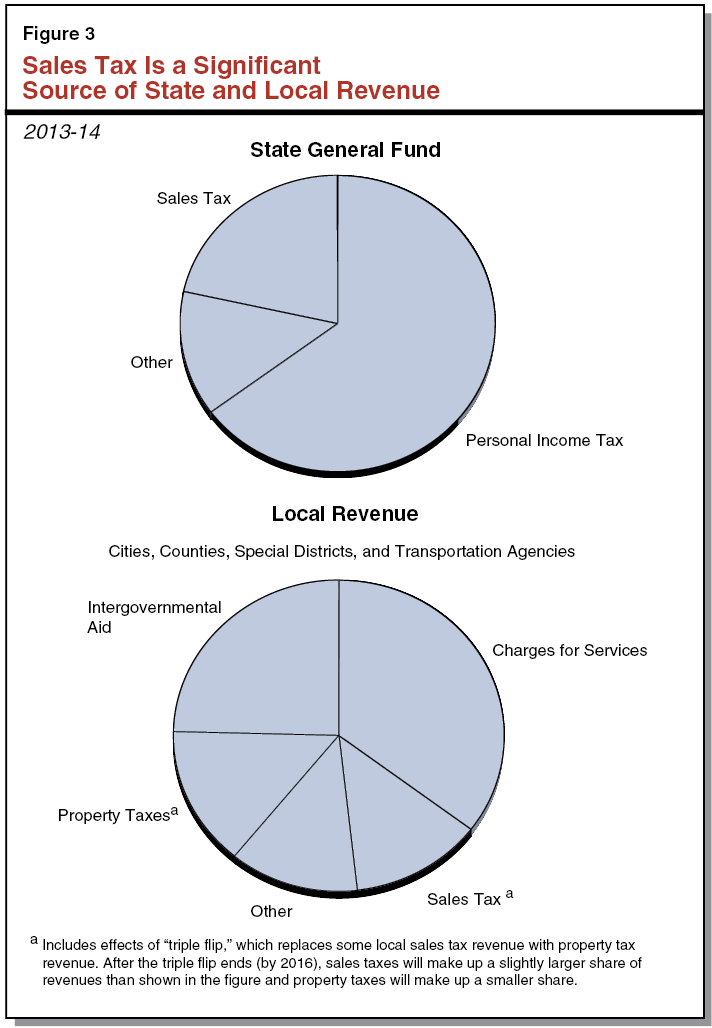

Sales Tax Is a Significant Source of Revenue for the State. As shown in Figure 3, the sales tax is the second–largest revenue source for the state’s General Fund, accounting for one–fifth of its revenue. The largest General Fund revenue source, the personal income tax, accounts for two–thirds of revenue. The relative contributions of these taxes has changed over time. In the 1950s, the sales tax accounted for the majority of General Fund revenue, while the personal income tax contributed less than one–fifth. Since then, personal income tax revenue has grown rapidly due to growth in real incomes, the state’s progressive rate structure, and increased capital gains. As described later in this report, sales tax revenue has grown more slowly in part because consumers are spending a declining share of income on taxable goods.

Sales Tax’s Role Varies Across Local Governments. Overall, the sales tax is local governments’ fourth–largest revenue source, but different types of local governments rely on this tax to different degrees. For example, the sales tax is a primary funding source for transportation agencies, but fire and water special districts do not receive any sales tax revenue. In addition, the sales tax is a significant revenue source for cities and counties, but those local governments face different constraints in the use of sales tax funds. Specifically, a large share of city sales tax revenue comes from the 1 percent Bradley–Burns rate and can be used for general purposes. In contrast, most county sales tax revenue is allocated to the two realignment funds, which are earmarked for specific programs.

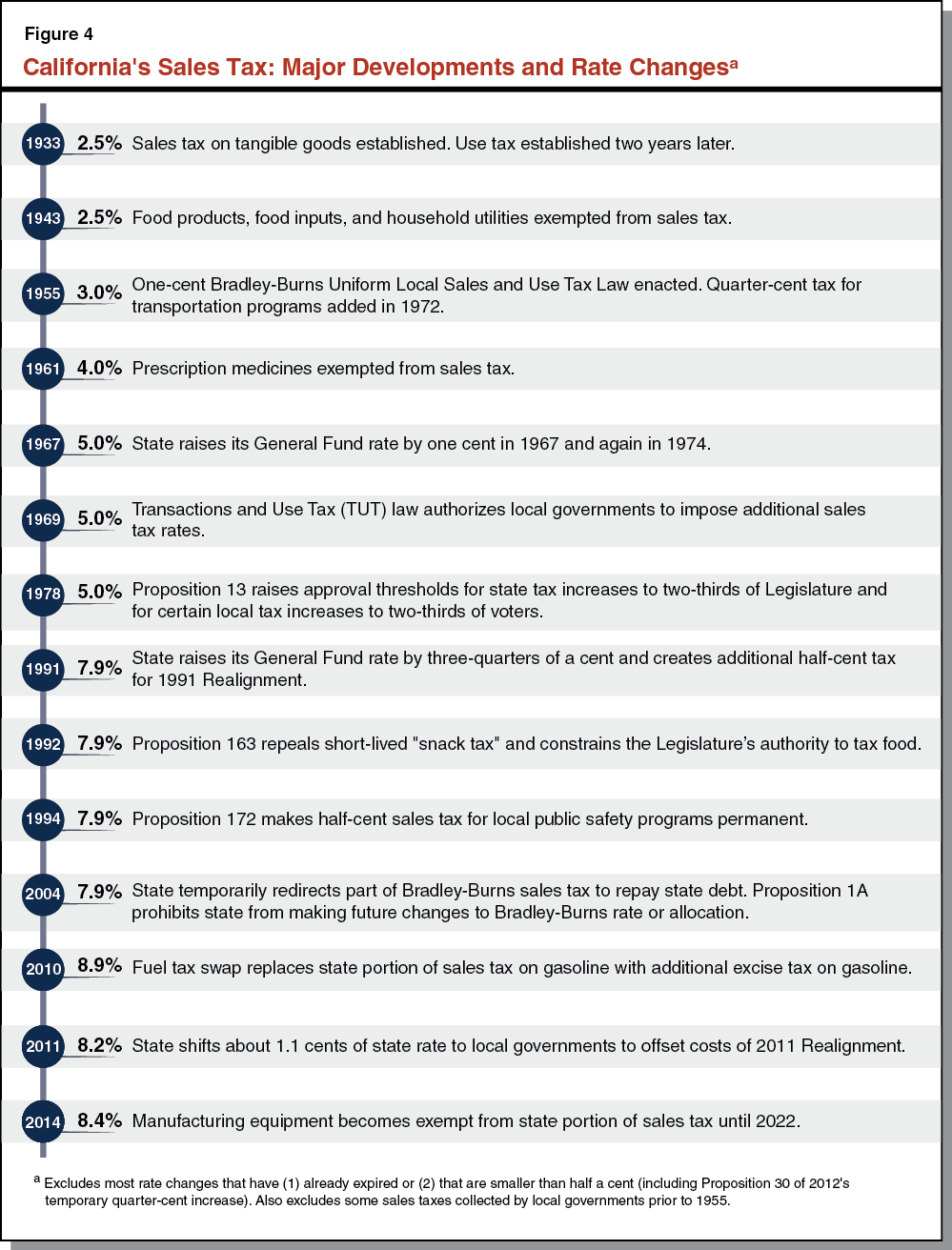

California has had a sales tax for eight decades, but the tax we have today is dramatically different from the initial one. When California created its sales tax in 1933 and its use tax in 1935, the rate was 2.5 percent and all revenue went to the state’s General Fund. Since then, the overall tax rate has more than tripled, the use of sales tax revenue has become more local and more restricted, and many types of tangible goods have become exempt from the tax. Figure 4 highlights some of the major changes, which generally fall into the following categories:

- Rate Increases. Three groups of rate increases have led to the current average sales tax rate of 8.5 percent. The first group has authorized local taxes: the Bradley–Burns rate for general purposes in 1955, the TUT Law for optional local rates in 1969, and the Bradley–Burns rate for transportation in 1972. The second group has increased the rate for the state’s General Fund, including one–cent hikes in 1967 and 1974. The third group has imposed new state rates for local programs: the 1991 realignment rate for health and social services and the Proposition 172 (1993) rate for public safety.

- Exemptions. The Legislature has exempted certain tangible goods from sales tax, including food, prescription medicine, household utilities, manufacturing equipment, and a variety of goods related to agriculture. (We discuss some sales tax exemptions later in the report.)

- Constitutional Restrictions. Ballot measures have amended the California Constitution in ways that limit the Legislature’s authority to make future changes to the sales tax. Proposition 13 (1978) sets a two–thirds vote threshold for (1) the Legislature to enact state tax increases and (2) local governments to approve certain tax increases. Proposition 163 (1992) constrains the Legislature’s authority to tax food. Proposition 1A (2004) prohibits the Legislature from (1) lowering the Bradley–Burns local sales tax or TUT rates or (2) changing the allocation of these revenues. Proposition 26 (2010) subjects a wider array of state tax changes to Proposition 13’s two–thirds legislative approval threshold.

California levies its sales tax on the retail sale of tangible personal property. State law defines these terms as follows:

- “Retail sale” excludes goods that businesses purchase for resale. It also generally excludes materials that go into products.

- “Tangible” generally refers to physical materials that people can touch. Products that are not tangible—such as services or digital goods—are not subject to sales tax.

- “Personal property” is movable from one place to another. Real property—land and things that are attached to land, like buildings—is not subject to sales tax.

California’s sales tax applies to a retailer’s sales to most buyers, including individuals, businesses, nonprofit and religious organizations, and California’s state and local governments. However, sales to some buyers, such as the federal government, are exempt from tax.

Sales Taxes on Discounted Goods. When a retailer sells a taxable good at a discount—through a club card, a retailer’s coupon, or an online “deal of the day”—the retailer generally calculates sales taxes based on the product’s discounted price, not its full retail price. However, for some types of discounts, sales tax applies to the full retail price before the discount is applied. Specifically, if the customer compensates the retailer for the discount—for example, by trading in a used car—then sales tax generally applies to the full retail price, not the discounted price. In addition, if the discount is available only through a bundled transaction (such as a mobile phone purchased together with a service contract), then sales tax applies to the full unbundled price of the taxable good (the full retail price of the mobile phone).

Sometimes, California consumers buy tangible goods from retailers who do not collect California sales tax. Those consumers generally owe use tax. For example, use tax is due in these common situations:

- Bringing Out–of–State Purchases Into California. Californians purchase tangible goods while they are traveling outside of the state. When they use those goods in California, they owe California use tax.

- Making Online Purchases From Out of State. Sales tax applies to tangible goods Californians purchase over the Internet. If the seller does not collect the tax on a taxable item (possibly because the seller is not located in California), the consumer owes use tax.

- Buying a Car From a Private Party. Individuals often sell used cars directly to other individuals. When this happens, the purchaser owes use tax. (Individuals who frequently sell used cars, however, are required to register as a retailer with the BOE and pay sales taxes.)

As discussed later in this report, many Californians are not familiar with the use tax, and compliance with this tax is uneven.

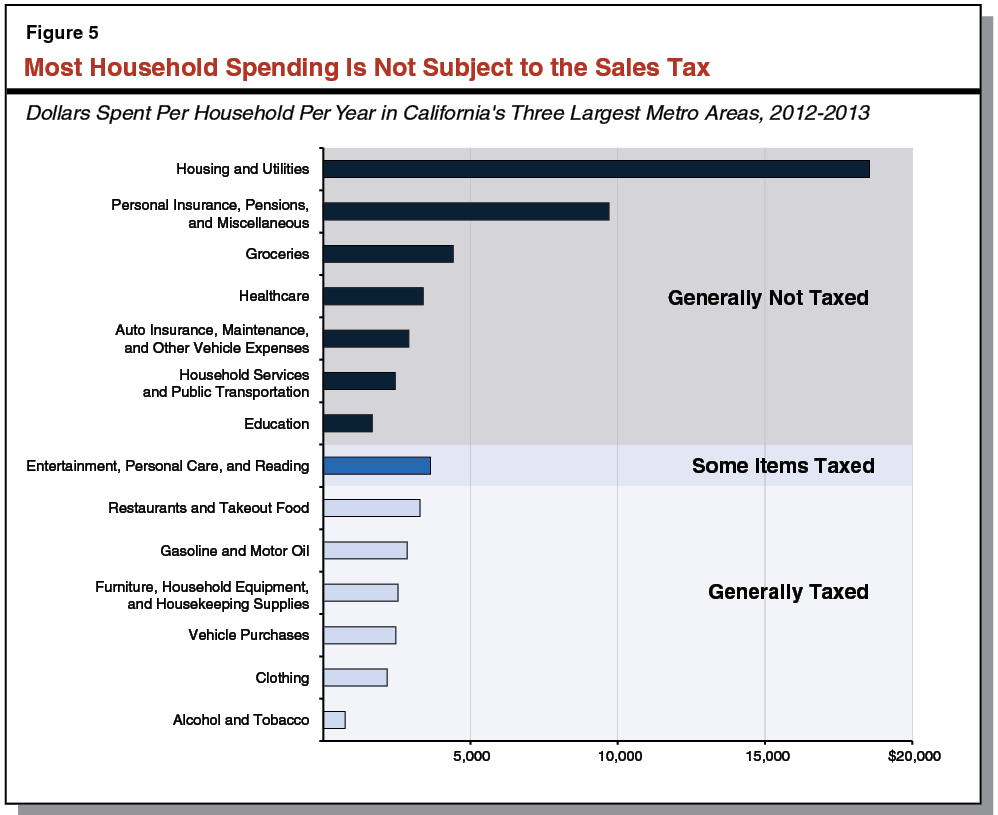

Most Household Spending Not Subject to Sales Tax. Figure 5 divides spending by households in California’s largest metropolitan areas—on average, about $60,000 per year—into 14 categories. Some categories of household spending—such as restaurant food, furniture, cars, and clothes—generally are subject to the sales tax. However, many other categories are not. For example, housing—by far the largest expenditure category—generally is not subject to sales tax. Homes attached to land are real property rather than personal property, so their sale is not subject to sales tax. (However, homes are subject to property taxes.) Household utilities generally are not subject to sales tax but often are subject to local utility user taxes. Groceries and prescription medicines are also exempt from sales tax, along with many other tangible goods that account for small portions of household spending.

Many household purchases are not subject to sales tax because they are not tangible personal property. For example, insurance, healthcare, and education are generally not part of the “tax base”—the set of things taxed—because they are not tangible goods. However, sales tax does apply to a very limited number of services that are closely connected to sales of tangible goods, such as mandatory service charges at restaurants.

Each Household’s Taxable Spending Fluctuates From Year to Year. Some taxable sales are “big–ticket items”—infrequent, major purchases of durable goods, like cars or household appliances. In some years, a household might make several such purchases, resulting in relatively high sales tax payments. In other years, the same household might not make any such purchases, resulting in much lower sales tax payments.

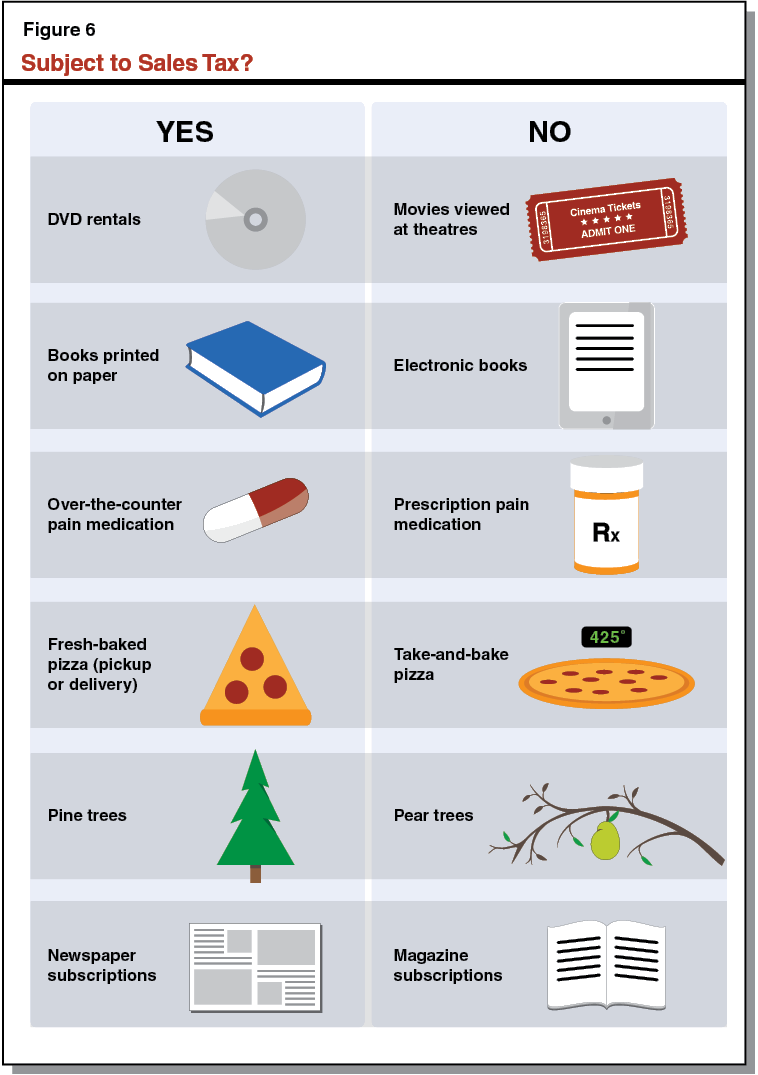

As shown in Figure 6, many similar items are treated differently for sales tax purposes.

Some Services Are Similar to Tangible Goods. Under California law, DVD purchases and rentals are subject to sales tax, but movies viewed at theaters are not. From a consumer’s perspective, the experiences are similar—all involve watching a movie. However, DVD consumers acquire physical objects, which are tangible goods and therefore subject to sales tax. Seeing a movie at a theater, in contrast, is a service, not a physical object. When consumers purchase such services, they do not pay sales tax—even if they could have similar experiences by buying or renting tangible goods.

Some Digital Goods Are Similar to Tangible Goods. DVDs are subject to sales tax, but streamed or downloaded movies are not. Books printed on paper are subject to sales tax, but electronic books are not. Digital goods are not tangible, so sales tax generally does not apply to them. As a result, many goods are taxable in tangible form but not in digital form.

Some Exempt Tangible Goods Are Similar to Taxed Tangible Goods. Over–the–counter pain medication is subject to sales tax, but prescription pain medication is not. The Legislature created the sales tax exemption for prescription medicine in 1961.

Some Exempt Food Items Are Similar to Taxed Food Items. Food for home consumption is exempt from sales tax. In practice, it can be difficult to identify whether a particular food item is for home consumption, so the state has developed a complex system of rules for distinguishing taxable food from exempt food. One such rule is that food heated right before it is sold is generally subject to sales tax. For example, fresh–baked pizza—whether picked up by the customer or delivered by the seller—is subject to sales tax. However, “take–and–bake” pizza—which is not heated prior to sale—is exempt from sales tax. Similarly, a sandwich purchased to go may shift from tax–exempt to taxable if the customer chooses to have the bread toasted.

Constitutional Restriction on Food Tax Rule Changes. In 1991, the state passed a law that extended the sales tax to certain foods—popularly known as the “snack tax.” In 1992, a ballot measure (Proposition 163) amended the California Constitution, repealing the snack tax and constraining the Legislature’s authority to tax food.

Many Goods Used to Produce Food Also Exempt. People who landscape their yards with pine trees pay sales tax. If they bought pear trees instead their purchases would not be taxed. Pear trees are exempt from sales tax because they produce food for human consumption. This exemption applies to plants, animals, seeds, fertilizer, feed, and medicine used for food production.

Some Exemptions Are Narrow. Magazine subscriptions are exempt from sales tax. However, magazines sold at stores are taxed, as are subscriptions to daily newspapers. This narrow exemption—like many others—emerged from efforts to balance a variety of competing interests. The Legislature created a broad sales tax exemption for all types of periodicals in 1945. In 1991, lawmakers eliminated this exemption as part of a broader effort to raise revenue. After magazine publishers objected to this change, the Legislature reinstated the exemption for magazine subscriptions but not for other sales of periodicals.

Most States Have State and Local Sales Taxes. Most states assess sales tax at the state and local levels. Some states, like Kentucky, have sales taxes at the state level but do not allow local governments to levy local sale taxes. Alaska is the opposite—local governments impose sales taxes, but the state does not.

A few states, such as Hawaii, levy taxes that are similar to sales taxes, but broader. These “gross receipts taxes” apply to many types of transactions, not just retail sales. A handful of states, like Oregon, do not levy sales or gross receipts taxes.

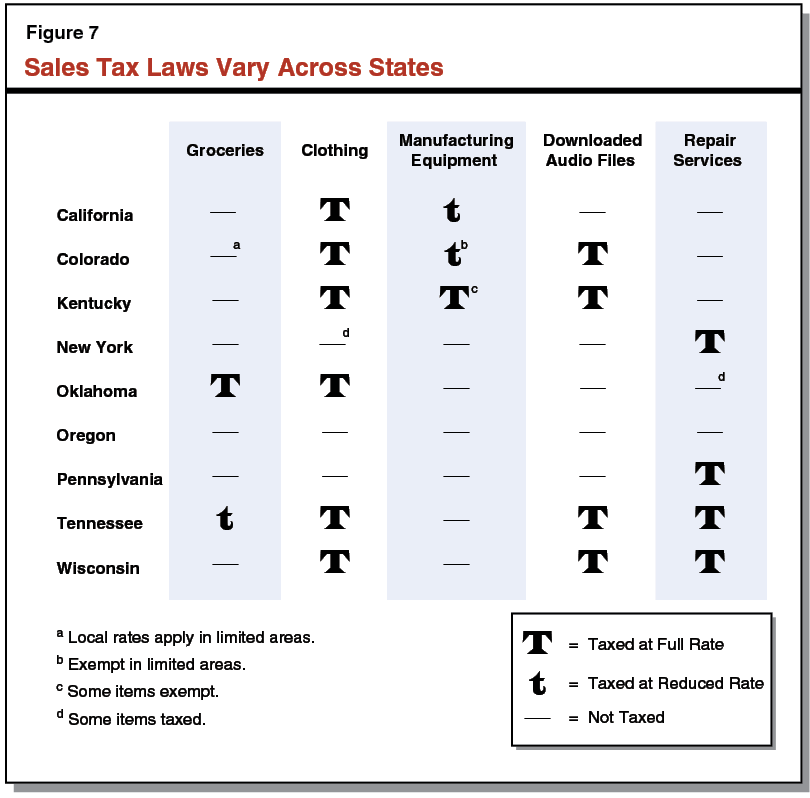

Exemptions for Tangible Goods Vary Across States. The nine states listed in Figure 7 highlight the wide range of variation in state sales tax policies. The first three columns of the figure highlight cross–state variation in exemptions for three types of tangible goods: groceries, clothing, and manufacturing equipment.

As shown in the figure, groceries are completely exempt from sales tax in many states, including California. Some states—like Oklahoma—tax groceries at the full rate, while other states—like Tennessee—tax groceries at a reduced rate. Although many states exempt groceries, some of these exemptions are narrower than California’s. For example, Wisconsin levies sales taxes on various “snack foods”—a policy that California voters prohibited when they approved Proposition 163 in 1992.

Taxation of clothing also varies across states. In Pennsylvania, most clothing is exempt. New York charges sales tax on clothing items over $110 but exempts less expensive items. California, like many other states, taxes clothing at the full rate.

As shown in the third column, many states exempt manufacturing equipment from sales tax. Some states, like Kentucky, generally tax manufacturing equipment at the full rate but offer some limited exemptions. Other states, like California and Colorado, tax manufacturing equipment at a reduced rate. Since 2014, California has exempted manufacturing equipment from the General Fund portion of the sales tax rate but not from the other parts of the rate. (Under current law, this partial exemption will expire on July 1, 2022.)

Taxation of Digital Goods Varies Across States. The fourth column of the figure shows that some states levy sales taxes on downloaded music files. Some of these states, like Wisconsin, have passed laws expanding their sales tax bases to include digital goods in addition to tangible goods. Others, like Colorado, tax digital goods because they interpret “tangible personal property” more broadly than California does. In both cases, states that tax digital goods must tackle some difficult legal issues. For example, they must develop—and then enforce—rules for determining where digital goods are sold.

Taxation of Services Varies Across States. Some states, like California, charge sales tax on a very small set of services—those that are essentially inseparable from sales of tangible goods. However, some states charge sales tax on a broader range of services, such as services performed on tangible goods. For example, some of the states shown in the figure levy sales taxes on automotive and appliance repair services.

Some States Have Locally Varying Sales Tax Bases. In California and many other states, the sales tax base is standard across cities and counties. That is, a retail transaction that is taxable in one part of the state is taxable in other parts of the state. However, in other states, like Colorado and New York, sales tax bases vary considerably across local areas. For example, New York City’s sales tax applies to various personal care services, like haircuts, that are not taxed elsewhere in New York State. In Colorado, groceries and manufacturing equipment are exempt from the state’s sales tax but are taxed in some cities. Colorado’s largest cities exempt groceries, but some smaller cities do not. Manufacturing equipment is partially exempt in some areas of Colorado but fully exempt in others.

In the eight decades since California created its sales tax, the state has made several major changes to the tax base. Most of these changes have narrowed the base by exempting certain types of tangible goods. For example, the Legislature is currently considering additional exemptions for various tangible goods, including energy–efficient appliances, low–emission vehicles, and diapers.

In recent years, lawmakers have also considered whether to expand the base. For example, the 2009–10 Governor’s Budget included a proposal to apply the sales tax to veterinarian services, amusement parks, sporting events, golf, and various repair services. The Legislature is currently considering a bill (SB 8 [Hertzberg]) that would create a broad sales tax on services with some specified exemptions.

As discussed earlier, every state makes decisions as to which purchases by households and businesses are subject to sales taxes—and these decisions change over time. Thus, the Legislature could enlarge or reduce the set of purchases subject to the sales tax. As the Legislature considers its options, it is important to note that the California Constitution limits the Legislature’s authority to include certain items (such as food or insurance) in the sales tax base. In addition, legislation narrowing the base of a tax can be approved by a majority vote of the Legislature, but expanding the tax base requires approval by two–thirds of the Legislature.

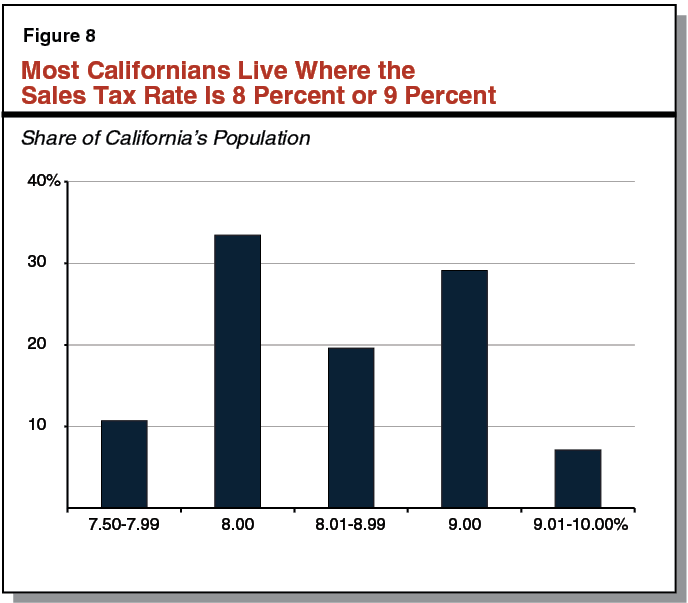

California’s Rates Range From 7.5 Percent to 10 Percent. The state’s average rate is roughly 8.5 percent, including a quarter–cent established by Proposition 30 of 2012. (This quarter–cent rate is scheduled to expire at the end of 2016.) Although California’s cities and counties have many different sales tax rates, two rates are much more common than others. As shown in Figure 8, almost two–thirds of Californians live in cities or counties with 8 percent or 9 percent rates. The remaining third live in places with other rates. While many rural counties have the lowest rate (7.5 percent), some of these counties contain cities with higher rates. Eight cities have the highest rate, 10 percent. (The tax rates described in this report are as of May 1, 2015.)

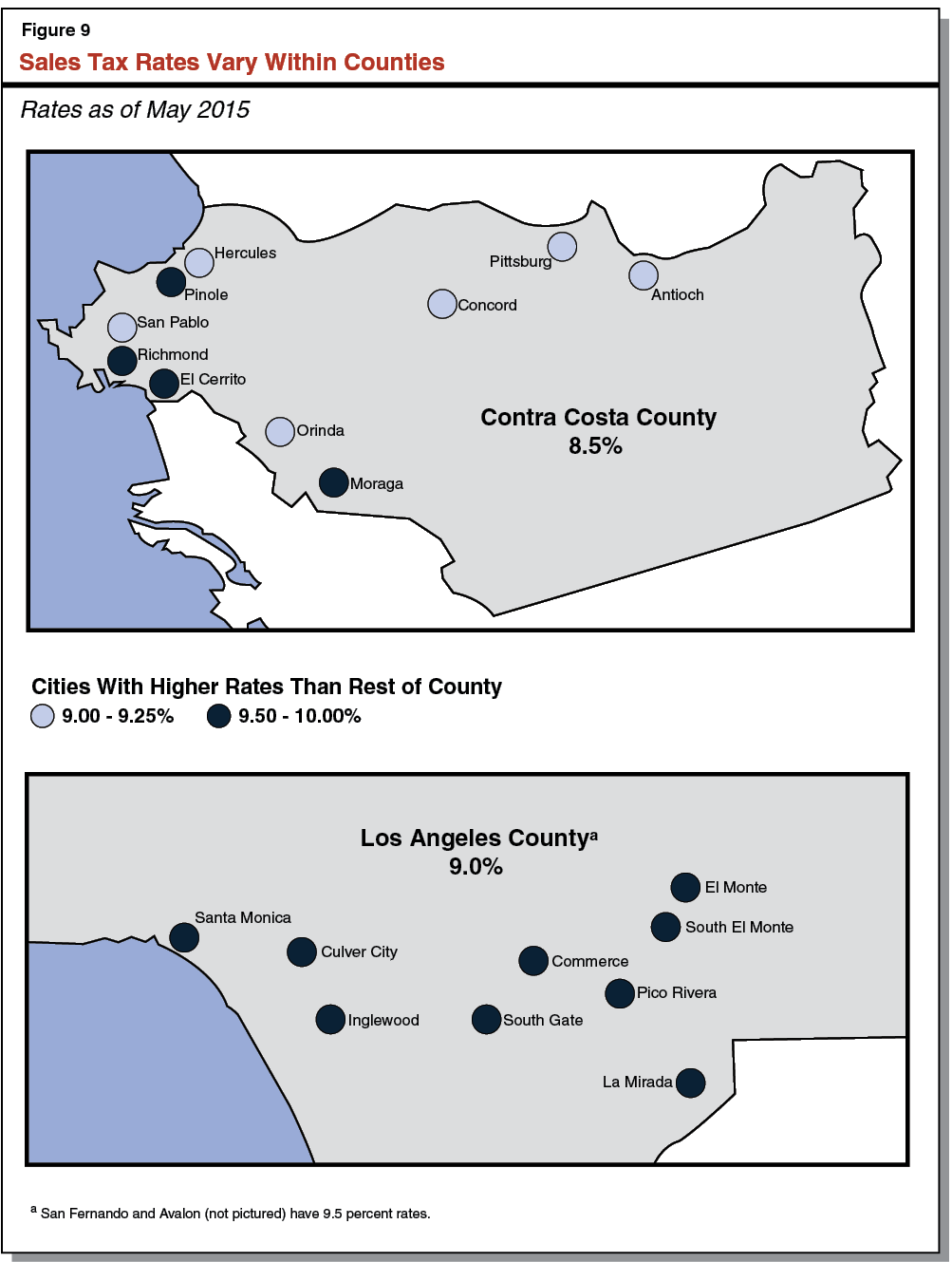

California’s major population centers include cities and counties with a wide range of sales tax rates. Figure 9 illustrates this variation in two counties: Contra Costa and Los Angeles. Specifically, the figure (1) shows the sales tax rate charged in most cities and the unincorporated area of each county and (2) identifies the cities in each county with sales tax rates that are higher than elsewhere in the county. As shown in the figure’s top panel, ten cities in Contra Costa County have sales tax rates higher than the 8.5 percent rate charged in the county’s unincorporated area and other Contra Costa cities. As shown in the figure’s bottom panel, the sales tax rate charged in most of the Los Angeles County is 9 percent. Eleven Los Angeles County cities, however, have rates ranging from 9.5 percent to 10 percent. This includes the nine cities shown in the figure’s map of southern Los Angeles County and two cities (San Fernando and Avalon) located elsewhere in the county.

Which Rate Applies? For most taxed transactions, the location where the buyer takes possession of the good determines the sales tax rate. When residents of San Mateo shop in San Francisco, they pay the San Francisco rate, 8.75 percent. When they purchase items to be delivered to their homes in San Mateo, they owe the San Mateo rate, 9.25 percent. Vehicle purchases are a key exception to this rule. When Californians buy cars—no matter where they take possession of them—they pay their locality’s sales tax rate.

Local Decisions Regarding TUTs Drive Rate Differences. Sales tax rates vary across localities because cities and counties differ in their imposition of optional local taxes. Under the state’s TUT Law, local governments may levy these TUTs in addition to the statewide rate of 7.5 percent. California’s constitution requires local governments to submit proposed TUTs to voters. TUTs that set aside revenue for specific purposes are considered special taxes and need approval by two–thirds of their local voters to pass. Otherwise, they are general taxes and pass with a simple majority.

Under state law, the combined rate of all TUTs in an area generally cannot exceed 2 percent. (Legislation pending at the time this report was prepared, AB 464 [Mullin], would change this limit to 3 percent.) However, the Legislature has passed laws allowing certain local governments to exceed the 2 percent cap. As a result, eight cities have 10 percent sales tax rates—two and a half cents above the 7.5 percent statewide minimum.

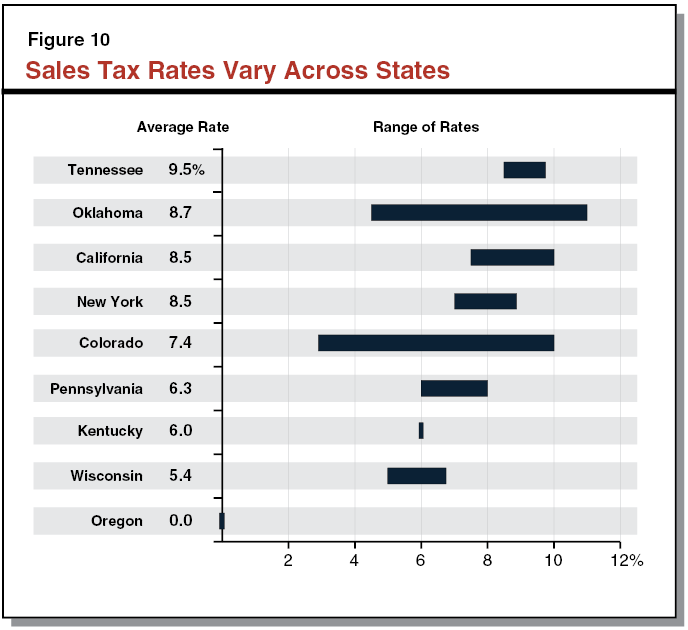

States’ Minimum Sales Tax Rates Vary. Figure 10 displays the rates for the states discussed earlier. Among states with sales taxes, Colorado has a relatively low minimum rate, 2.9 percent. Tennessee has a relatively high minimum rate, 8.5 percent. (These minimum rates are the lowest actual rates in each state. They are not necessarily the lowest rates allowed by state law.) As mentioned above, Oregon has no sales tax.

Local Tax Rates Vary. Most states have sales tax rates that vary across cities and counties, but some have uniform rates statewide. Kentucky, along with six other states, has a sales tax at the state level but not at the local level. As a result, its 6 percent rate is uniform throughout the state. Tennessee has local sales taxes, but the range of rates is relatively narrow—less than one and a half cents. At the other end of the spectrum, the difference between Colorado’s lowest and highest rate is more than seven cents.

States’ Maximum and Average Rates Vary. As shown in Figure 10, Kentucky’s maximum rate is six percent, while Oklahoma’s is 11 percent. Some states, like Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, have average rates that are close to their minimum rates. Other states, like New York and Tennessee, have average rates much closer to their maximum rates. Wisconsin’s average rate is 5.4 percent, while Tennessee’s is 9.5 percent. (These averages are weighted by population.)

Some States Apply Different Sales Tax Rates to Different Products. As discussed earlier, some states levy reduced sales tax rates on certain products. For example, California taxes manufacturing equipment and gasoline at lower rates than other goods. (We provide information about the state’s sales tax rates on fuel in the box below.) In other cases, states levy additional taxes—often known as “excise taxes”—on specific products. For example, California imposes excise taxes on fuel, cigarettes, and alcohol.

Different Sales Tax Rates Apply to Fuel. Prior to 2010, California applied the same sales tax rate to fuel as it did to other goods. Additionally, the state levied 18–cent–per–gallon excise taxes on gasoline and diesel fuels. In 2010, the Legislature enacted the “fuel tax swap”—a combination of sales tax and excise tax changes designed to give the state more flexibility in the use of fuel tax revenues. As a result, the state now applies special sales tax rates to gasoline and diesel. California’s sales tax rate on gasoline is 5.25 cents lower than the rate on other goods. Offsetting this lower sales tax rate, the state has an extra excise tax on gasoline, in addition to the base rate of 18 cents per gallon. The additional tax rate—12 cents per gallon in 2015–16—changes once per year. The state uses the opposite approach for diesel fuel, with an extra sales tax rate and a reduced excise tax rate. The annual rate changes are designed to achieve “revenue neutrality” by cumulatively raising the same amount of revenue as would have been raised pursuant to the state’s fuel tax laws in effect prior to the swap.

As described earlier in this report, California’s sales tax rate includes many distinct pieces. As the number of pieces has grown over time, the laws governing the allocation of sales tax revenue have grown more complex. This section discusses these allocation laws in three groups—statewide rates for state programs, statewide rates to support realigned programs, and other rates for local programs—and then highlights some exceptions to these allocation laws.

The largest component of the sales tax rate is the approximately 4.2 percent rate that goes to the state’s General Fund. This revenue pays for a wide variety of programs, including K–12 education, higher education, health programs, and criminal justice. The General Fund rate includes a quarter–cent rate established by Proposition 30 (these revenues will expire at the end of 2016). In addition to the overall 4.2 percent General Fund rate, the state has set aside a quarter–cent sales tax for another state purpose: repaying debt. As described in the box below, this “triple flip” rate will likely end in 2015.

“Triple Flip” Rate Will Likely End in 2015. The Bradley–Burns rate for city and county operations—1 percent historically—is temporarily reduced to 0.75 percent. This temporary change is part of a budget maneuver called the triple flip that will likely end in 2015.

In 2004, the state borrowed money to pay for its accumulated budget debts. To repay the borrowed money, it imposed a quarter–cent state sales tax rate to deposit into a newly created Fiscal Recovery Fund. To keep the overall sales tax rate constant, the state reduced the local Bradley–Burns rate by a corresponding quarter–cent. That substitution was one of three “flips” that redirected revenue, leading to the name triple flip. The other two flips (1) directed school property tax money to cities and counties to compensate them for the redirected sales tax revenue and (2) reimbursed schools for their reduced property tax revenues.

Two state sales taxes for county–administered programs—the half–cent 1991 realignment rate and the approximately 1.1 cent 2011 realignment rate—were created as part of the 1991–92 and 2011–12 state budget agreements, respectively. In both cases, the state addressed budget deficits by shifting (or “realigning”) some state program and/or fiscal responsibilities to counties. To mitigate the fiscal effect of these transfers on counties, the state (1) imposed a new half cent rate in 1991, earmarking its revenues for the realigned health and social services programs and (2) redirected part of the state’s sales tax rate (about 1.1 cents) to counties in 2011, earmarking the revenues to pay for the realigned criminal justice, mental health, and social services programs. In both cases, the state allocates the sales tax revenue based on formulas that are intended to reflect each county’s programmatic responsibilities.

Local Public Safety and Bradley–Burns Transportation Rates. Two statewide rates for local programs—the half–cent Local Public Safety sales tax and the quarter–cent Bradley–Burns tax rate for county transportation programs—have similar revenue allocation rules. Unlike realignment revenue, the money raised by these rates does not go to counties based on programmatic factors. Instead, all of the revenue collected within a particular county goes back to that county. All revenue raised by the Bradley–Burns transportation tax supports county transportation programs. Most revenue from the Local Public Safety tax is used by counties for public safety programs, but a small share (about 5 percent) is allocated to cities for public safety purposes.

Bradley–Burns Rate for General Purposes. Revenue from the Bradley–Burns rate is available to local governments—primarily cities—for general purposes. The state allocates this revenue to the city or county that served as the “place of sale” in a transaction. In general, the place of sale is the retailer’s sales location. Bradley–Burns tax revenues from sales occurring with a city’s limits are allocated to that city; revenues from transactions occurring in a county’s unincorporated area are allocated to the county. This approach to revenue allocation is known as a “situs–based” system. As discussed in the nearby box, this system gives cities and counties significant fiscal incentives to promote retail development within their jurisdictions.

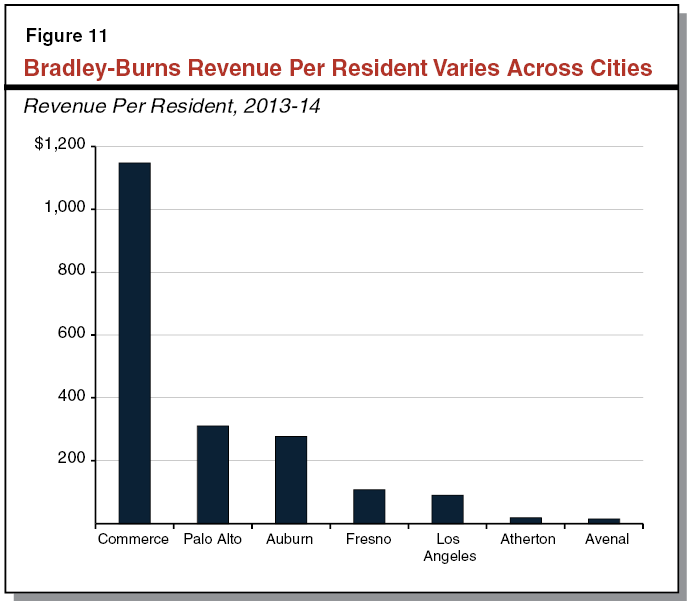

Bradley–Burns Revenue Varies Across Cities. Although the Bradley–Burns rate is uniform throughout the state, it raises widely varying amounts of revenue across cities. Figure 11 highlights some examples of cities with different levels of Bradley–Burns revenue per resident in 2013–14. With $110 per resident, Fresno’s revenue is close to the average for a California city. Los Angeles raises $90 per resident—a lower amount than most large California cities. Many Los Angeles residents shop in surrounding cities, such as Commerce. With an outlet mall and other retailers, Commerce raises $1,150 per resident—more than ten times the amount raised by the average California city.

To some extent, variation in Bradley–Burns revenue reflects income differences across cities. For example, Palo Alto, whose residents’ incomes are much higher than average, raises $310 per person, while Avenal, whose residents’ incomes are much lower than average, raises $15 per person. However, other factors also contribute to this difference. Avenal is in a rural area with few potential shoppers nearby. Palo Alto is close to other cities, many of which also have high–income residents. For example, Atherton—one of the highest–income cities in California—contains few retailers, and its residents sometimes shop in nearby Palo Alto. As a result, Atherton’s Bradley–Burns tax raises $19 per person—less than one–fifth of the average city.

Some cities raise large amounts of Bradley–Burns revenue without having high incomes or being close to large numbers of shoppers. As described in the nearby box, this is partly due to actions taken by cities to compete for revenue. For example, Auburn raises $280 per resident, much of it due to the presence of a business that sells fuel through a “cardlock system.” This type of business can concentrate taxable sales at a single location—even when the physical exchange of goods occurs at many locations.

Cities Compete for Bradley–Burns Revenue. As described in our 2007 report, Allocating Local Sales Taxes: Issues and Options, distributing Bradley–Burns revenue based on the retailer’s sales location gives local governments fiscal incentives to maximize retail sales within their boundaries. In some cases, cities and counties have responded to these incentives by seeking to influence the location of new retail development. For example, some cities and counties have (1) used their land use powers to reserve large tracts of readily developable land for retail purposes and (2) established fiscal policies—such as partial sales tax rebates to retail businesses—to attract retail development.

In other cases, local governments have taken actions to shift the legally defined “place of sale” for retail transactions without changing the location of the economic activity. For example, some cities have competed to attract businesses that sell “cardlock systems.” A cardlock system allows businesses to make an advance purchase of large amounts of fuel. All Bradley–Burns revenue from this transaction goes to the city where the advance purchase occurs. The physical transfer of fuel associated with the purchase, however, occurs later in other cities and counties throughout the state.

Transactions and Use Taxes. As described earlier in this report, many cities and counties levy optional local sales taxes known as TUTs. Statewide, the average TUT rate is about 1 percent, but some areas have rates as high as 2.5 percent. For most transactions, TUT revenue is allocated to the place where the buyer takes possession of the purchased good. Vehicle purchases are the main exception. TUT revenue from vehicle sales goes to the local government where the vehicle is registered, regardless of where the buyer takes possession of it.

Ballot Measure Limits Legislature’s Authority Over Local Revenue Allocation. In 2004, voters approved Proposition 1A, an amendment to California’s constitution. This measure prohibits changes to the TUT and Bradley–Burns allocation systems. Consequently, any further changes would require voters to approve another amendment to the state’s constitution.

Allocation of Bradley–Burns Use Tax. California allocates Bradley–Burns local use tax through countywide pools. These pools assign revenue to local jurisdictions based on each jurisdiction’s share of total taxable sales. The state also uses this method to allocate Bradley–Burns revenue that cannot be identified with a permanent place of business. However, local use tax revenue from some transactions—generally very large purchases—does not enter these pools. Instead, it goes to the jurisdiction where the buyer first uses the purchased goods.

Allocation of Local Tax Revenue From Jet Fuel. For sales of jet fuel, the place of sale is the place where the jet fuel is delivered to the aircraft. (However, a recent ruling by the Federal Aviation Administration could lead to future changes in jet fuel taxation.)

California’s state and local revenue from the sales tax—which totaled $48 billion in 2013–14—has grown at an annual rate of 7.3 percent since 1970–71. Over the same period, total sales tax revenue has grown faster than personal income—a measure of the size of the state’s economy. Personal income has grown 7 percent per year.

Sales tax revenue growth varies from year to year. In the last four decades, sales tax revenue grew fastest in 1974–75 (22 percent annual growth) and slowest in 2008–09 (a 10 percent annual decline). Revenue from other taxes also varies from year to year. However, these year–to–year fluctuations—often described as revenue “volatility”—are more pronounced for some taxes than for others. From the state government’s perspective, the sales tax is a relatively stable tax because it is less volatile than the personal income tax, the state’s main revenue source. From the perspective of local governments, the sales tax is a relatively volatile tax since it is more volatile than the main local tax, the property tax.

Year–over–year growth in sales tax revenue does not necessarily reflect underlying growth in the tax base. For example, the economy was in a recession in 1974–75, but sales tax revenue grew very fast that year—largely due to high inflation and a one–cent rate increase.

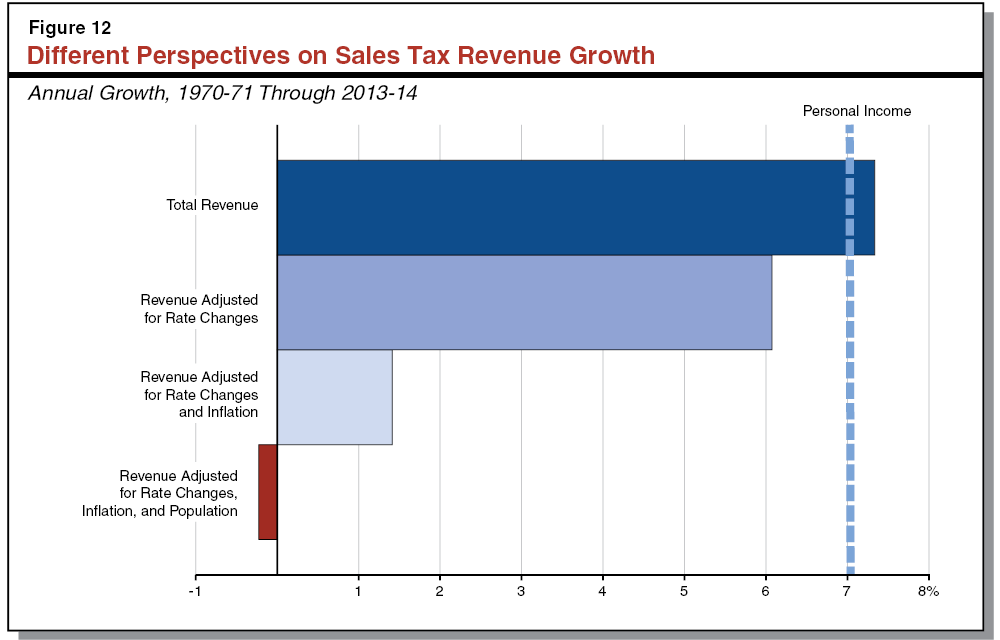

To illustrate a more meaningful growth measure, Figure 12 shows sales tax revenue growth from 1970–71 to 2013–14, with adjustments for rate changes, inflation, and population growth.

- Rate Change Adjustment. The sales tax rate was 5 percent in 1970–71 and 8.4 percent in 2013–14. Adjusting sales tax revenues for each year’s rate allows us to focus on growth in the tax base—taxable sales—rather than growth in revenue. As shown in Figure 12, rate–adjusted revenue has grown 6.1 percent per year since 1970–71.

- Inflation Adjustment. Prices tend to rise over time—including the prices of state and local government purchases. As a result, one dollar of state or local spending represents fewer real resources in 2014 than it did in 1970. Adjusted for rate changes and inflation, sales tax revenue has grown about 1.4 percent per year since 1970–71.

- Population Adjustment. As the number of Californians increases, so does the size of the state’s economy, which leads to higher revenue from sales tax and other taxes. However, the state’s main expenditures—education and health care—provide services to individuals. Consequently, population growth also increases the demand for state services. For these reasons, it is useful to consider not just total revenue, but also revenue per person. Adjusting for rate changes, inflation, and population, sales tax revenue has remained roughly constant over the long run, declining 0.2 percent per year since 1970–71.

As described in our 2013 report, Why Have Sales Taxes Grown Slower Than the Economy?, the share of Californians’ personal income that they spend on taxable items peaked in 1979. In that year, consumers spent about half their income on taxable items. Since then, the state’s sales tax base has grown slower than the state’s economy. As a result, consumers now spend about one–third of their income on taxable goods.

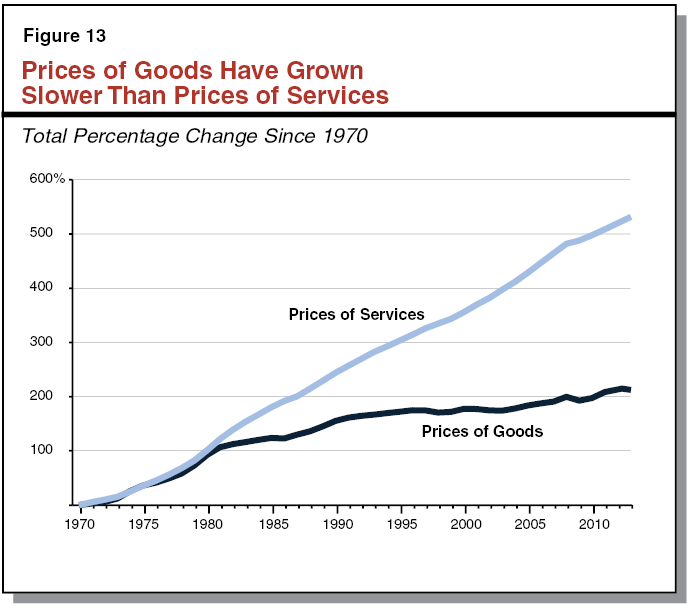

This shift in consumer spending has occurred primarily because prices for services (which generally are not subject to the sales tax) have grown four times as much as prices for goods (which generally are subject to the sales tax), as shown in Figure 13. Prices of goods have grown slowly for several reasons, including growth in manufacturing productivity and imports of low–cost goods. Unlike production of most goods, production of services tends to be labor–intensive and customized, making it harder to cut costs. This factor—along with many other developments, like growing demand for healthcare services for an aging population—has led to relatively rapid growth in prices of services.

Two Main Challenges: Awareness and Enforcement. Many Californians are not familiar with the use tax, so they do not attempt to comply with it. Additionally, the use tax is difficult to enforce since the obligation to pay generally falls on buyers—including households, businesses, and others.

Uncollected Use Tax Could Be Substantial. Due to data limitations, it is difficult to estimate the “tax gap”—the difference between taxes owed and taxes paid. Recent estimates indicate that California’s use tax gap could be $1 billion or more.

Despite Challenges, Use Tax Revenue Is Growing. State and local use tax revenue totaled $4.6 billion in 2013–14, up from $4.4 billion in 2012–13 and $3.9 billion in 2011–12. Use tax revenue grew faster than sales tax revenue over this period.

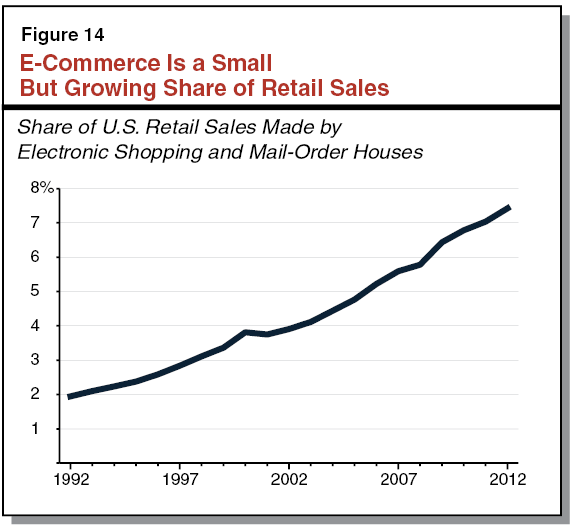

E–Commerce Has Grown Faster Than Other Retail Sales. Although the challenges of use tax awareness and enforcement are not new, they have become more relevant as the Internet has made out–of–state purchases more convenient. As shown in Figure 14, retailers that specialize in selling goods over the Internet or by mail are a small but growing share of retail sales. Nationwide, this category grew from 2 percent of nationwide retail sales in 1992 to over 7 percent in 2012.

Federal Law Limits State’s Power to Collect Use Tax. The most direct strategy for collecting the use tax is to collect the money from the seller rather than the buyer. However, federal law—particularly the U.S. Constitution’s commerce clause—limits states’ ability to collect use tax from out–of–state retailers. If an out–of–state retailer does not have a “physical presence”—employees, offices, warehouses, or the like—within a state, that state cannot require the business to collect use tax. This physical presence test is based on a series of legal decisions—particularly the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Quill Corp. v. North Dakota (1992). In Quill, the court ruled that North Dakota could not levy a tax on Quill Corporation because the business had no physical presence in the state.

Based on the Quill decision, Congress may pass a law allowing states to require out–of–state retailers to collect use tax. The U.S. Senate passed such a bill in 2013 (S. 743). Around the same time, the House of Representatives referred a similar bill (H.R. 684) to two committees but has not acted on it since.

State Employs Multiple Strategies to Collect Use Tax. California’s efforts to collect use tax include:

- Registering Out–Of–State Retailers. State law requires all retailers “engaged in business” in California—those with a physical presence in the state—to register with BOE to collect use tax. Revenues from these businesses account for half of all use tax collected. Because many relationships among businesses are complex, it is sometimes unclear whether a particular business is physically present. Chapter 313, Statutes of 2011 (AB 155, Calderon and Skinner), specifies that the requirement to collect use tax extends to: (1) out–of–state retailers in the same “commonly controlled group,” or corporate family, as in–state businesses; and (2) out–of–state retailers who work with in–state “affiliates”—people who refer potential customers to those retailers.

- Registering Buyers. The state has several programs through which in–state buyers—primarily businesses—register with BOE to pay use tax on their purchases. For example, the “qualified purchasers” program requires some service businesses (like law or accounting firms) to report the use tax owed on goods they purchase from out of state.

- Other Interactions With Taxpayers. California drivers who buy vehicles from private parties or from out–of–state dealers pay use tax when they register those vehicles with the Department of Motor Vehicles. In addition, the Franchise Tax Board allows taxpayers to report and pay use tax on their state income tax returns.