The Sacramento–San Joaquin Delta (Delta) is a biodiverse ecosystem that covers about 1,150 square miles and is used to convey water from Northern California to Southern California. Several significant problems are occurring in the Delta that negatively impact environmental quality and water supply reliability. Specifically, scientists and policy experts have found that the current approach to managing the Delta must change in order to (1) meet the state’s environmental objectives (such as improving the health of native species in the Delta) and (2) ensure that the state has a reliable water supply. In 2009, the Legislature formally established these two goals in statute as the state’s policy for the Delta and enacted legislation to help achieve them. However, many obstacles to achieving the goals remain. A better understanding of these obstacles will help inform the Legislature in making future decisions regarding the Delta.

In this report, we (1) provide an overview of the importance of the Delta to California in terms of biodiversity and water supply, (2) describe the problems facing the Delta and their causes, (3) review ongoing efforts to improve certain aspects of the Delta, and (4) identify issues for the Legislature to consider to help ensure that its goals and objectives for the Delta are achieved.

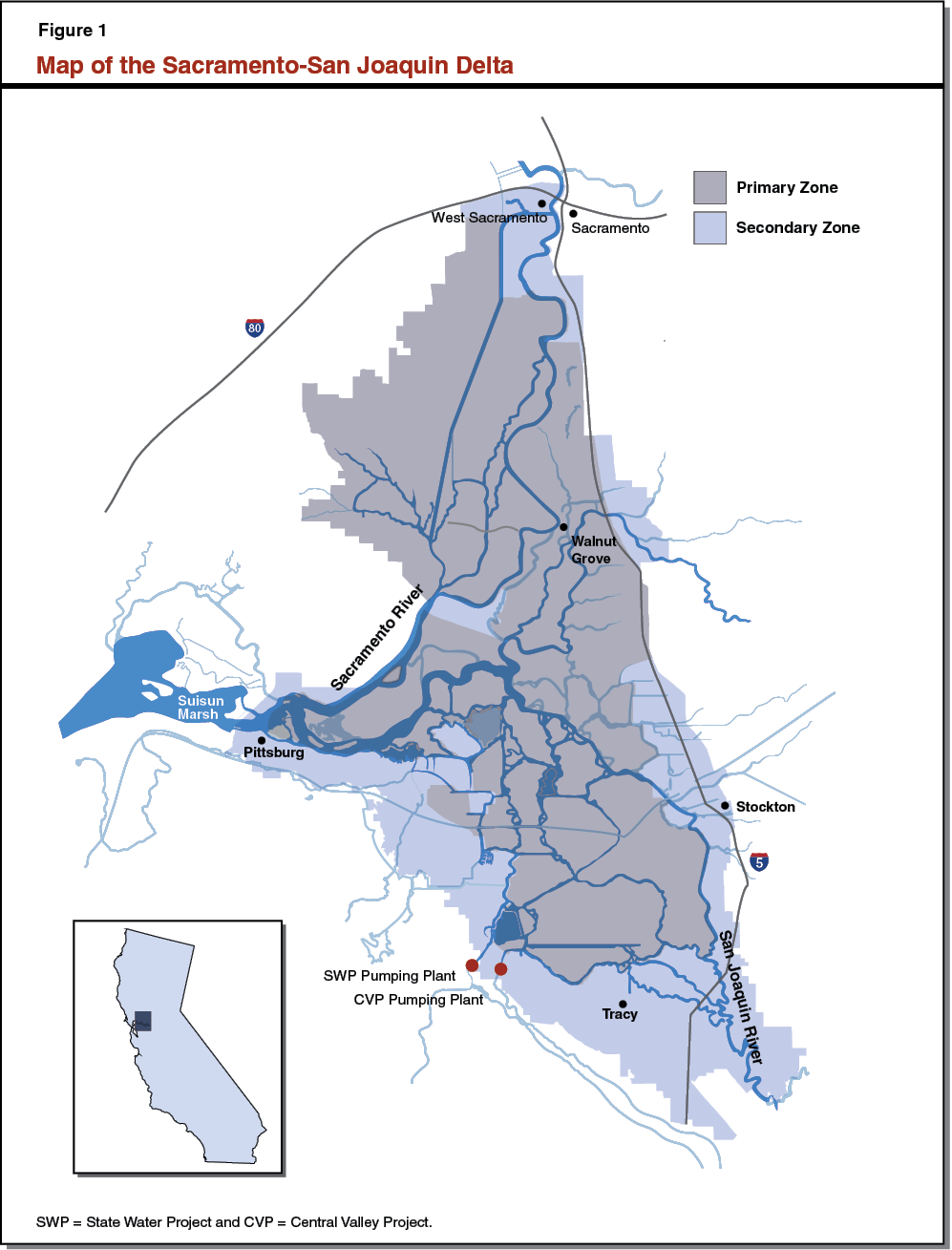

The Delta is formed by the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers and covers about 1,150 square miles in Sacramento, San Joaquin, Contra Costa, Solano, and Yolo counties. The Delta comprises about 70 islands that have been created from what was historically tidal marshland through the construction of over 1,100 miles of levees. About three–fourths of the water flowing into the Delta comes from the Sacramento River. In addition, the Suisun Marsh, the San Francisco Bay, and the Pacific Ocean affect the Delta through the tides and the flow of saltwater. Figure 1 provides a map of the Delta.

The Delta is divided into two zones—the primary zone and the secondary zone. The primary zone makes up two–thirds of the total land area and is mostly located in the interior of the Delta. State law places restrictions on development in the primary zone in order to preserve the ecological, agricultural, and recreational aspects of the Delta. In contrast, the secondary zone is on the periphery of the Delta and includes urban areas such as Stockton, West Sacramento, and several cities in the eastern Bay Area. In part because of the above restrictions in the primary zone, the primary and secondary zones have developed at different paces into distinct agricultural and urban areas. While the primary zone relies on agriculture as its main economic activity and is sparsely populated, the secondary zone is urbanized and home to most of the Delta’s 571,000 residents.

Although the Delta is geographically located in one part of the state, it affects the rest of the state in four important ways. As we discuss below, the Delta is (1) a biologically diverse ecosystem, (2) essential to the state’s water system, (3) a place with economic and cultural value to the state, and (4) an important infrastructure corridor.

Biologically Diverse Ecosystem. The Delta is the largest estuary on the west coast and contains a variety of habitat types for over 700 species of fish and wildlife. In addition, many of the state’s native fish species migrate through the Delta. As a result, the Delta is important for maintaining biodiversity in California and the United States.

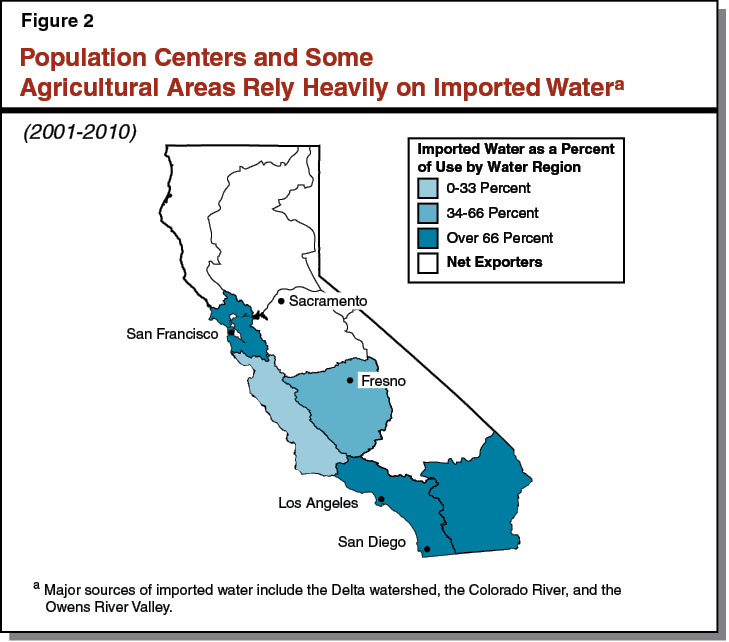

Essential to State’s Water System. Water supply in California does not naturally occur where demand is highest. Much of the state’s precipitation occurs in the northern and eastern parts of the state, while much of the demand occurs in the south and on the coast because of the locations of population centers and agricultural lands. As a result, two large water projects—the State Water Project (SWP) and the federal Central Valley Project (CVP)—were built to store and transport water throughout the state. (A glossary is included as an appendix to this report that provides a more complete list of agencies and programs working in the Delta, as well as definitions of other key terms.) These projects store water in dams upstream of the Delta and use rivers to transport it to the Delta. The water then moves through the Delta’s waterways to pumps in the southern part of the Delta, where the SWP and CVP then pump, or “export,” that water to the Central Valley, Southern California, and parts of the San Francisco Bay Area. Figure 2 shows which regions of the state are net importers and exporters of water. (The Department of Water Resources [DWR] divides the state into ten regions, based on the geography of water basins.)

The SWP and CVP deliver water exported from the Delta to 63 local agencies (referred to as “water contractors”) in the south and on the coast. These contractors fund most of the costs of operating and maintaining SWP and CVP. The contractors generally then sell water to smaller local agencies that serve agricultural and urban water users. For example, the Metropolitan Water District is one of the largest contractors and sells water to 26 agencies in Southern California, such as the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power and the San Diego County Water Authority.

On average, half of the water exported from the Delta goes to SWP contractors, with the remainder going to CVP contractors. About two–thirds of the water exported from the Delta is used by agriculture, while the remainder is allocated to urban and industrial users. Approximately one–quarter of the state’s cropland is irrigated with Delta water, and 25 million Californians (about two–thirds of the state’s population) rely on Delta water for part or all of their drinking water. Three of the largest contractors in the state—Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, Kern County Water Agency, and Westlands Water District in Fresno and Kings Counties—have received about 60 percent of the water exported from the Delta since 1981.

While water exported from the Delta has only made up an average 13 percent of total water use in the state in recent years, the Delta is an important source of water that helps the state’s overall water system function well for two reasons. First, as we discuss later in this report, Delta water is currently a relatively cheap source of water supply for agricultural and urban users. Second, Delta water helps the state manage its water supplies through “conjunctive use,” where groundwater and surface water are used in combination to maximize the amount of water that can be sustainably used. Specifically, in wetter years, more Delta water is available for export, and it can be used to replenish groundwater that was depleted during drier years when less surface water had been available.

Economic and Cultural Value. As noted above, the Delta is home to over half a million people. It contributes to the state’s economy, with annual economic output exceeding $26 billion per year in 2008 (most recent data available). While urban areas such as Stockton drive most of the Delta economy, it is also an important agricultural region that produces a wide variety of crops, such as corn, tomatoes, wine grapes, and asparagus. In addition, the Delta contains many small communities that have historical value. Finally, the Delta provides opportunities for recreation and tourism, including fishing, boating, wildlife watching, wine–tasting, and other activities. The Delta receives about 12 million visitors per year.

Important Infrastructure Corridor. The Delta is also an important corridor for goods movement throughout northern and central California. The Delta is intersected by 1,800 miles of roads (including three interstate highways), three freight railways, and the Stockton and Sacramento shipping channels. In addition, the ports of Stockton and West Sacramento serve as key processing points for bulk goods produced in and imported to California. For example, the port of Stockton is one of the largest inland ports on the West Coast and serves as the entry point for most of the fertilizer used in the Central Valley. Other infrastructure with regional or statewide importance in the Delta includes: electrical transmission lines; natural gas pipelines and storage; and the Mokolumne Aqueduct, which supplies water for much of the eastern Bay Area.

The Delta faces several significant problems, including (1) declining health of the Delta’s ecosystem, (2) restrictions on water supply, (3) worsening water quality, and (4) the failure of Delta levees. Left unaddressed, these problems could persist or worsen over the next 30 to 50 years. According to existing research, the annual costs associated with these problems could potentially range from the hundreds of millions of dollars to the low billions of dollars. Although the Legislature, the administration, and other stakeholders have made efforts to address these problems in the past, the Legislature formally established the goals of resolving these problems with the passage of the Delta Reform Act of 2009. We discuss in more detail below each of the problems and their effects on the state.

Ongoing Decline in the Health of the Delta Ecosystem

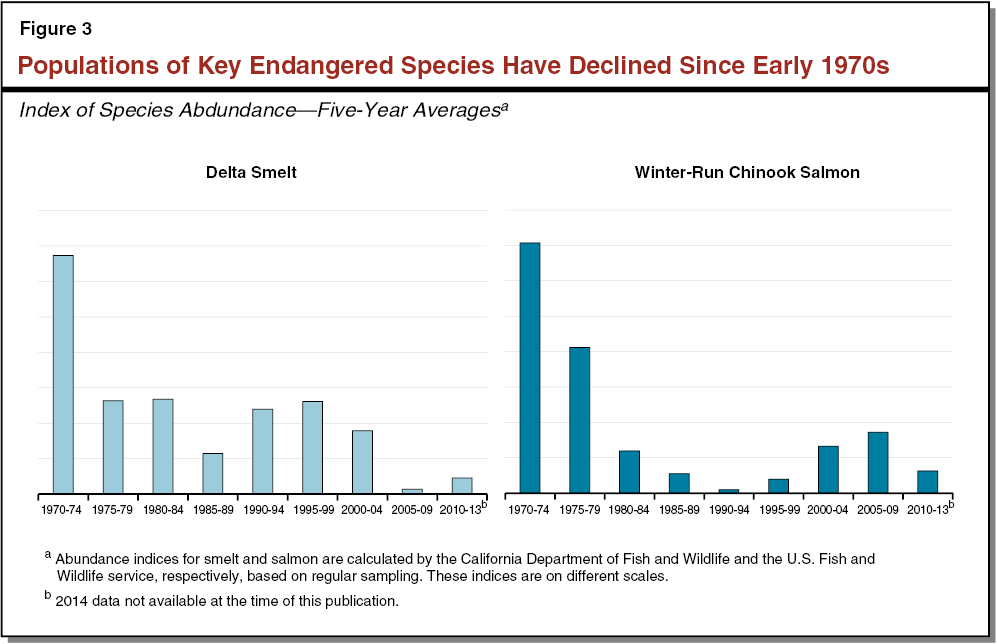

Decline of Native Fish Species Since 1970s. The Delta ecosystem has been degraded over time, resulting in harm to endangered species, including certain native fish species. As we discuss below, the decline of native species has resulted in restrictions on how much and when water can be exported by the SWP and CVP. In particular, as shown in Figure 3, there has been a decline in Delta smelt and winter–run chinook salmon since the early 1970s. Populations of certain fish species—particularly Delta smelt—have been especially low in recent years. Several endangered types of salmon, steelhead, and green sturgeon have also declined in recent years. In contrast, nonnative species are thriving, including aquatic invasive plants (such as egeria densa), invertebrates (such as certain species of clams), and fish (such as largemouth bass).

Causes of Ecosystem Decline. There are many factors causing the decline of the Delta ecosystem. These causes include water diversions from the Delta (including exports by the SWP and CVP), increases in invasive species, and pollutants such as selenium and methyl–mercury. In addition, it is estimated that over 95 percent of the habitat that historically supported native species of fish and wildlife in the Delta has been eliminated.

These factors interact in complex ways. A single factor may have different effects on different species or parts of the Delta. For example, the construction of dams upstream of the Delta has harmed salmon by blocking their migration but has not had the same impact on other species. In addition, the combined effects of multiple factors may be greater than that of each factor taken separately. For example, both habitat degradation and changes to water flows (such as water diversions) have had harmful effects on species in the Delta. The interaction between these two factors increases the harm that each factor causes because (1) changes to water flow have reduced species access to remaining habitat that is of good quality and (2) degraded habitat reduces species ability to adapt to the consequences of changes in water flow. This complexity makes it difficult to identify the factors that have the greatest negative effect on the Delta and, consequently, the most cost–effective ways to improve the Delta.

Reductions in Water Supply Reliability

The decline of the Delta ecosystem, among other factors, has prompted state and federal agencies to reduce the amount of water that can be pumped out of the Delta, thereby reducing the reliability of the state’s water supply. These reductions can have significant economic effects.

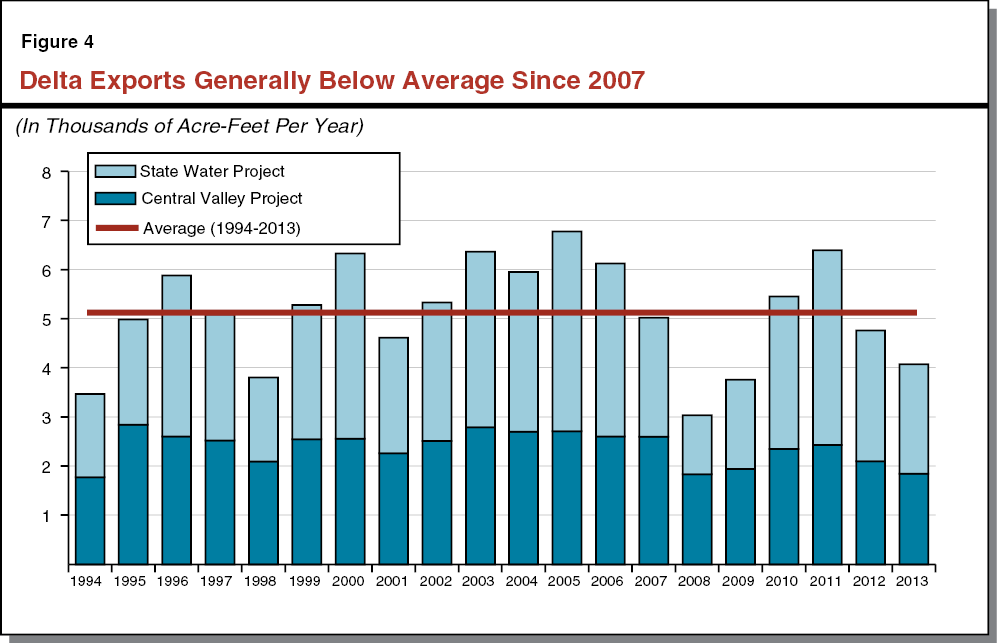

Water Exports From Delta Are Declining. State and federal regulatory agencies have responded to decreases in fish populations by reducing the amount of water exported from the Delta through the SWP and CVP. This effort to protect fish species has affected the reliability of the state’s water supply. Over the past 40 years, exports of water from the Delta have varied from a low of 2.1 million acre–feet in 1977 to a high of 6.9 million acre–feet in 2005. (Water is commonly measured in acre–feet, which is the volume of water required to cover one acre of land to a depth of one foot—roughly the annual amount of water used by two average households.) Figure 4 shows Delta exports by CVP and SWP from 1994 to 2013. As shown in the figure, exports have been below the historical average in five of the past seven years because of several dry years and regulatory actions intended to protect the environment. Exports are expected to continue to decline in the future because of factors such as climate change and regulatory actions that could place further restrictions on the timing and amount of pumping from the Delta. According to the Bay Delta Conservation Plan (BDCP), state and federal agencies could reduce water exports in the future by about one–fourth to one–third.

Water Quality Regulations Affect Supply. The State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB), including the nine regional water boards, makes some rules that affect how much water can be exported from the Delta by SWP and CVP. This is because SWRCB develops regulations that protect Delta water quality. Specifically, SWRCB sets water quality rules to preserve the “beneficial uses” of water (such as for drinking, irrigation, fish habitat, or industry) in the Delta and other bodies of water. These rules:

- Regulate Delta Water Flows. The amount of water flowing in a river or stream can affect water quality, such as by affecting the concentration of pollutants. Thus, in order to improve the water quality in the Delta, SWRCB regulates the amount and timing of water flowing into and out of the Delta through its Bay–Delta Water Quality Control Plan (Bay–Delta Plan). Specifically, SWRCB administers the state’s water rights system, which permits the use of a specified amount of water for a beneficial purpose. For example, the board has the authority to regulate how much water an individual can divert, as well as when that water is diverted. In 2000, SWRCB placed conditions on when the CVP and SWP can divert water under their water rights in order to protect water quality, which reduced water exports.

- Limit Discharge of Pollutants. The SWRCB also sets rules that limit the concentrations of pollutants that harm beneficial uses in the Delta. The board enforces these rules by placing restrictions on the amount of pollutants that dischargers—such as municipalities and industry—can put into waters that feed into the Delta, including the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers.

Endangered Species Regulations Also Affect Supply. The operations of SWP and CVP have the effect of “taking” (killing or otherwise negatively affecting) endangered species in the Delta, such as by capturing and killing fish at the pumps. Thus, in order to operate, the projects must receive “incidental take permits” from state and federal wildlife agencies to comply with the state and federal endangered species acts. These permits include rules that ensure CVP and SWP operations do not harm endangered species. For example, some rules dictate when the pumps can operate so that fish are not caught in the pumps, which in turn reduces water supply. In 2008 and 2009, state and federal wildlife agencies updated those rules in response to declining fish populations. These rules have further reduced exports and also require SWP and CVP to restore 25,000 to 28,000 acres of habitat in the Delta and Suisun Marsh.

Reduced Water Supply Could Have Economic Effects. Reduced exports have the potential effect of increasing the cost of water statewide. Some amount of reduction in exports can be mitigated with relatively inexpensive approaches such as using water conservation efforts to reduce demand. However, to the extent Delta exports were reduced significantly, developing and obtaining alternative water supplies would be increasingly costly. According to DWR, the costs of alternatives to Delta water (such as water recycling or desalination) are generally higher but vary significantly depending on a variety of factors. These factors include the type of infrastructure improvements that are required, whether economies of scale can be realized, where in the state the water will be used, and the cost of inputs such as energy. For example, while Delta water delivered by SWP cost an average of $187 per acre foot in 2014, San Diego County Water Authority recently signed a long–term agreement to purchase desalinated water at ten times that amount. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power estimates that their water conservation programs cost between $75 and $900 per acre foot in 2011. Such alternatives might be too expensive for some water customers. To the extent that available alternatives are too expensive, those users might reduce water use. Reductions in water use could result in economic losses, particularly in the agricultural sector.

Worsening Water Quality

Water pollutants such as urban wastewater discharges, agricultural discharges, saltwater intruding into the Delta, and pollutants from previous eras (such as mercury) have impaired water quality in the Delta. According to SWRCB data, ten pollutants in the Delta significantly impair water quality. By comparison, the upper part of the Sacramento River is only impaired by one pollutant. Treatment costs are likely to increase in the future as the Delta faces greater concentrations of certain pollutants. For example, the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) projects that sea level rise will result in additional treatment costs for urban users of Delta water because water agencies will have to use more expensive technology to treat the saltier water. Specifically, it estimates that an increase of one foot of sea level rise will increase water treatment costs by $80 to $440 per acre foot in 2050, resulting in increased treatment costs ranging from $200 million to $1 billion annually. The actual increase in costs would depend on the technologies used to treat the water and how these increased costs will affect demand for Delta water. Moreover, as water in the Delta becomes saltier, it becomes less suitable for agricultural use, which could negatively affect farming in the Delta and throughout the state.

Failure of Delta Levees

Many Delta Levees Are at Risk of Failure. Agriculture in the Delta and movement of water through the Delta for the SWP and CVP both depend on an extensive system of levees. Currently, many of the levees in the Delta are in jeopardy of failing for several reasons. First, many Delta levees were constructed before the development of most modern techniques for ensuring the integrity of their foundations and preventing erosion—meaning they are not as reliable as the highly engineered levees typically built today. Second, the shape and size of Delta levees provide relatively low levels of flood protection. This is because the levees were designed primarily to protect agricultural areas, which suffer less damage and loss of life from flooding than urban areas. Third, the land behind many levees has “subsided” (or sunk lower) over time, which negatively affects the ability of the levees to hold back water. Thus, in order to maintain the same level of protection, the levees in the Delta have required strengthening over time. In 2009, DWR estimated that the likelihood of a major failure of multiple Delta levees in the next 25 years was greater than 50 percent.

Causes of Levee Failure. Delta levees are surrounded by water at all times and can fail as a result of earthquakes, storms, water seeping through the levee, or other reasons. Sometimes, it is unclear why levees fail. For example, the levees protecting a large Delta island, Jones Tract, failed on a sunny day in 2004 for reasons that remain unknown. Moreover, the failure of one section of a levee can cause failures elsewhere in the levee. In addition, the probability of failure will likely increase if no action is taken in the future as Delta islands subside and water levels rise due to climate change, thereby increasing pressure on the levees.

Effects of Levee Failure. According to DWR and other experts, a failure of these levees could damage infrastructure such as farms, roads, and natural gas pipelines in the Delta. A major failure could also affect water exports from the Delta for as much as a year, particularly if salt water from the San Francisco Bay flowed into the Delta because of the failure. The costs associated with the failure of Delta levees would depend on the number of islands that flood and the time of year when the failures occur. Such costs would include (1) emergency response and levee repair, (2) loss of agricultural and industrial output, and (3) the loss of use of major infrastructure such as state highways. In 2009, DWR estimated that a major failure of multiple Delta islands would cost over $22 billion.

Effect of State Spending on Levees Unknown. Prior to 2006, most funding to upgrade and maintain Delta levees came from two bond measures that authorized a total of $100 million for flood protection in the Delta. Voters approved two additional water–related bond measures in 2006 that significantly increased funding for Delta levees. Since then, the Legislature has appropriated $575 million in funding for Delta levees from those bonds, including $275 million from the Safe Drinking Water, Water Quality and Supply, Flood Control, River and Coastal Protection Bond Act of 2006 (Proposition 84) and $300 million from the Disaster Preparedness and Flood Protection Bond Act of 2006 (Proposition 1E). This funding has been used to evaluate the conditions of Delta levees and add material to them in order to strengthen them. However, the effects of this spending on the likelihood of failure is unknown because repairs are ongoing and the state has not comprehensively reevaluated the risk of levee failure.

Since 1935, the state has engaged in numerous efforts to address the problems facing the Delta. Past efforts include an attempt by the Legislature and Governor to build a peripheral canal to move water around the Delta, as well as efforts to construct new dams in partnership with the federal government. More recently, the Legislature enacted the Delta Reform Act of 2009, which was intended to comprehensively address the environmental, water supply, and infrastructure problems in the Delta. In addition, the Administration is currently developing a proposal called the BDCP in an effort to change the way water is conveyed through the Delta. Figure 5 provides a timeline of the state’s major efforts regarding the Delta, which we describe in more detail below.

Past Attempts to Resolve Delta Problems

Since the 1940s, a variety of engineering and policy proposals have been developed to address the problems facing the Delta. These proposals have included strengthening certain levees to convey fresh water through the Delta and releasing additional water from upstream reservoirs. Two principal attempts in the past 35 years include (1) the peripheral canal and (2) the CALFED Bay–Delta Program (CALFED). Although they were unsuccessful, positive and negative aspects of these attempts persist in today’s efforts to improve the Delta.

Proposed Peripheral Canal

In 1980, the Legislature authorized the construction of a “peripheral canal” to divert fresh water from the Sacramento River and convey it around the Delta to pumping plants in the south. Supporters of the peripheral canal, such as DWR and the Department of Fish and Game (recently renamed the Department of Fish and Wildlife [DFW]), believed that it would have improved the state’s water supply by increasing the amount of water exported, as well as improved the quality of water exported by taking higher quality water directly from the Sacramento River. In addition, supporters thought the canal would provide environmental benefits compared to the existing system of pumping water from the south Delta because a canal would have fewer harmful effects on fish. For example, pumping from the southern part of the Delta interferes with salmon migration by changing stream flows, and young fish get caught in the pumps. In contrast, groups opposed to the canal—including a coalition of environmentalists, Northern California water interests, and some farmers—raised a variety of concerns with the amount of water that would be exported. The project went before the voters in 1982 as Proposition 9. At the time, DWR estimated the capital cost to be at least $3.1 billion. Ultimately, voters defeated Proposition 9 and the construction of the canal.

CALFED

In response to increasing environmental concerns and water supply restrictions, state and federal agencies created CALFED in 1994. The program was a collaboration of 25 state and federal agencies focused on improving California’s water supply and the ecological health of the Delta. Constructing new dams upstream of the Delta was a cornerstone of CALFED. Some of the added storage capacity would have been set aside for environmental purposes, such as to release cold water at times when it would benefit fish (rather than to meet urban or agricultural water demands). The remainder of the storage capacity would have been used to increase the water supply and improve water quality for contractors. The estimated cost to construct the proposed surface storage was $9.5 billion in 2007. CALFED also planned and completed ecosystem restoration projects (such as habitat restoration on Delta islands) and improvements to Delta levees. Finally, CALFED established a Delta Science Program, which provided scientific guidance to the participating agencies.

CALFED was overseen by a state agency—the California Bay–Delta Authority, which was governed by a 24–member board, including representatives from state and federal agencies, the public, and the Legislature. Several issues hindered CALFED—including a weak governance structure, disagreement on what water uses should be prioritized, uncertain financing, and a lack of performance measures—leading to its end in 2009. (As discussed below, some elements of CALFED continue as part of the current efforts in the Delta.)

Current Efforts to Resolve Delta Problems

In more recent years, efforts were initiated to resolve the problems in the Delta. In particular, the Legislature enacted a package of legislation in 2009 that identified goals and objectives for the Delta, replaced the CALFED governance structure, and mandated the creation of a plan for the future of the Delta. This package also established policies to address other water management issues by improving water conservation and groundwater monitoring throughout the state. The administration is also in the process of completing BDCP. We discuss these and other ongoing efforts related to the Delta below.

Delta Reform Act and the Delta Plan

The centerpiece of the 2009 package was the Delta Reform Act of 2009 (Chapter 5, Statutes of 2009, Seventh Extraordinary Session [SBX7 1, Simitian]), which had several purposes. First, the act established state goals and objectives for the Delta. The primary aim of the act was to achieve the “coequal goals” of (1) providing a more reliable water supply for California and (2) protecting, restoring, and enhancing the Delta ecosystem, while also preserving the cultural, recreational, natural resource, and agricultural characteristics of the Delta. Other goals identified in the act were to improve flood protection, ensure orderly development in the Delta, and reduce the state’s reliance on the Delta for its water supply. The Legislature also identified objectives that it considered integral to achieving these goals, such as improving water conveyance and promoting statewide water–use efficiency.

Second, the Delta Reform Act established a new governance structure to resolve the lack of accountability and authority that hindered the CALFED program. To carry out this objective, the act created the Delta Stewardship Council, which was charged with developing and approving a Delta Plan to set objectives and the overall direction for state policy in the Delta for the next 50 years. The council approved the plan and associated regulations in 2013 and is required to update them at least every five years. The plan includes binding regulations as well as nonbinding recommendations intended to ensure progress in areas such as water supply reliability, ecosystem restoration, water quality, flooding, and the economic health of the Delta. It also includes performance measures for improving water supply reliability and enhancing the Delta ecosystem.

The 2009 package of water legislation also included a requirement that SWRCB update by 2018 its Bay–Delta plan that sets the inflows and outflows required to protect beneficial uses on the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, as well as their tributaries. Additionally, the 2009 water package set water conservation targets for urban water agencies to reach by 2020, as well as established a program to monitor groundwater elevation.

BDCP

BDCP is the administration’s proposal, led by the California Natural Resources Agency and DWR, to address some of the Delta’s water supply reliability and environmental problems. The main features of BDCP are (1) construction of two tunnels that would allow water to be diverted from a different part of the Delta and (2) restoration of about 150,000 acres of habitat in the Delta. At the time this report was prepared, state and federal fish and wildlife agencies were responding to public comments submitted on BDCP and are expected to make a final decision in 2015. As discussed below, BDCP can proceed without legislative action, although the Legislature may be asked to appropriate funding for some portions of it.

Major Components of BDCP. The centerpiece of BDCP is a new method of conveyance. Specifically, a set of tunnels underneath the Delta would take water from the Sacramento River to the existing pumping plants in the southern part of the Delta. The SWP and CVP would both receive water from these tunnels. Currently, the SWP and CVP export Delta water from separate pumping plants, but coordinate their operations and have jointly funded some facilities. For example, the two projects share the San Luis Reservoir in Merced County, which stores water for both projects.

In addition, the BDCP proposes numerous conservation measures intended to address some of the causes of ecosystem decline in the Delta. Such measures include protecting or restoring roughly 150,000 acres in the Delta and surrounding areas by acquiring land and making it more suitable as habitat for native and protected species. Some of this restoration activity is required by existing rules that allow the SWP and CVP to operate. The BDCP also contains measures to directly manage invasive and native species, improve water quality, and provide ongoing scientific monitoring of the environment.

Intended to Comply With Endangered Species Acts (ESAs). The state and federal ESAs generally prohibit activities that result in the taking of threatened or endangered species. However, DFW and federal wildlife agencies can issue permits that allow some taking of protected species if several conditions are met. For example, some taking is allowed if (1) taking the species is not the primary purpose of the activity, (2) the impacts of the activity are minimized and fully mitigated, and (3) issuing the permit would not jeopardize the existence of the species. State and federal wildlife agencies have used this permitting authority to develop rules that affect the operations of SWP and CVP, such as those we described earlier in regards to water supply reliability.

The BDCP is a natural community conservation plan (NCCP), which is an alternative way of complying with the ESAs. The state Natural Community Conservation Planning Act (NCCPA) of 2003 allows entities in California to comply with the state ESA by developing a NCCP to conserve habitat for all of the protected species in an area. (The federal ESA allows for similar plans.) If a plan meets certain requirements in the NCCPA, DFW approves it and issues the permits to take species covered by the plan. The requirements in the NCCPA include describing (1) the conservation measures that will be undertaken to help the covered species recover and (2) how such measures will be funded. In addition, NCCPs must be accompanied by an agreement among the permittees and state and federal wildlife agencies that establishes conditions under which the above permits can be revoked. If approved, BDCP would allow wildlife agencies to issue new take permits for the proposed tunnels—allowing SWP and CVP to operate for the next 50 years. It would also replace the current rules affecting SWP and CVP operations.

Legislative Involvement in BDCP. Significant portions of BDCP can proceed without legislative action. Specifically, DWR can construct and fund new conveyance—such as the tunnels in BDCP—using its existing authority. The 1960 bond act that authorized the development of the SWP also allows for the construction of “Delta facilities,” which could include new conveyance. In addition, the revenues from water contractors that fund SWP are continuously appropriated to DWR, meaning that the department does not require an annual appropriation approved by the Legislature to spend the funds. However, there has been some legislative direction on BDCP. Specifically, the Delta Reform Act directs the Delta Stewardship Council to incorporate BDCP into the Delta Plan if state and federal wildlife agencies approve BDCP. However, the Council can make its own determination of whether it meets those requirements.

$202 Million Spent on BDCP. As of August 2014, DWR had spent $202 million on BDCP since 2006–07. All of these funds have been spent for planning activities, such as developing legally required environmental documents, preliminary engineering and design, and planning the operations of the tunnels. These costs have been paid for by SWP and CVP water contractors south of the Delta pursuant to a series of agreements with DWR and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR). Under these agreements, the costs are split evenly between the state and federal water contractors.

Many Agencies Perform Related Functions in the Delta

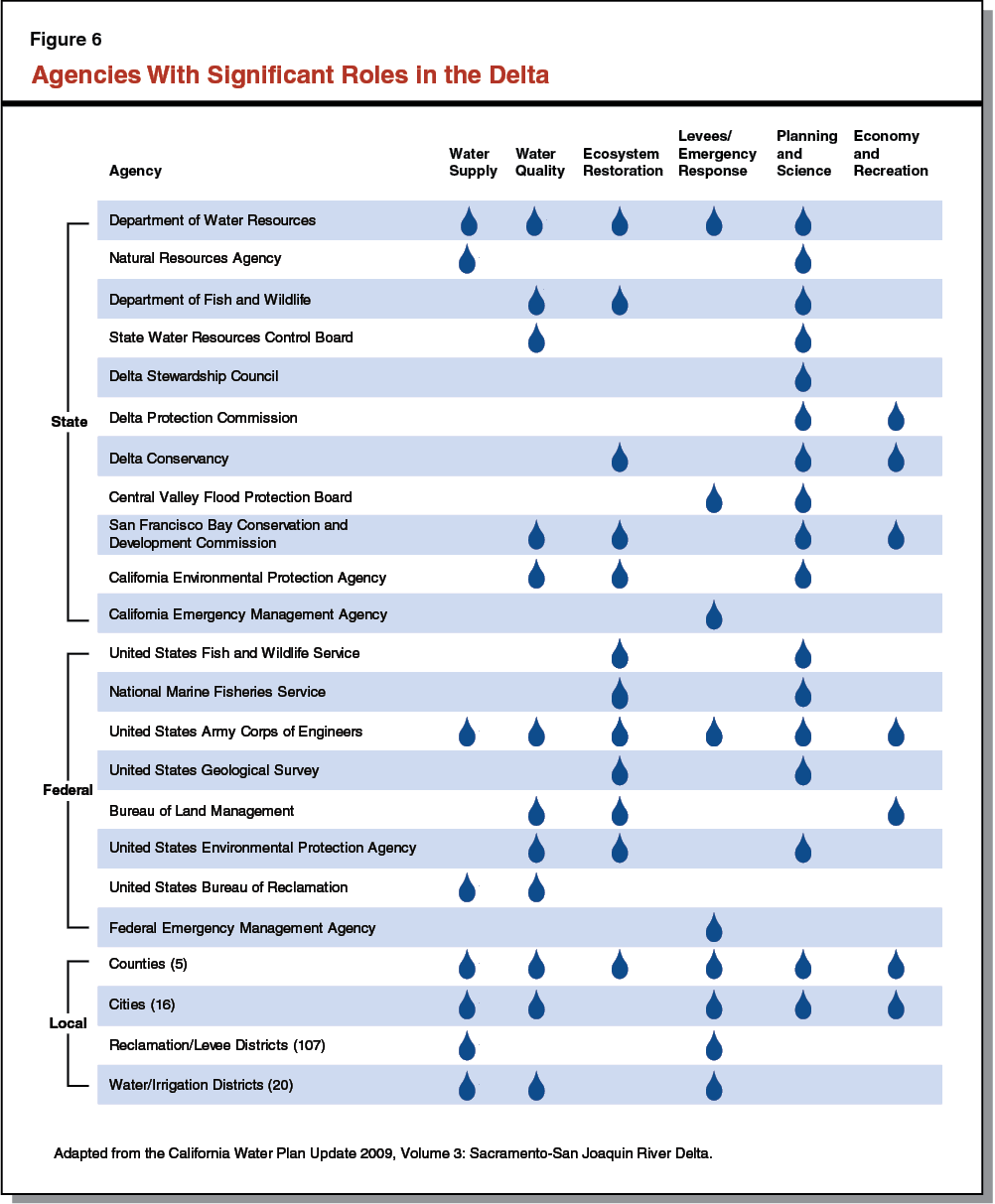

While the Delta Reform Act and the BDCP are two major state efforts to improve the Delta, many local, state, and federal agencies have other responsibilities for setting policies and implementing programs in the Delta, as shown in Figure 6.

Agencies Issue Water Regulations Related to Quality and Supply. As described above, SWRCB and state and federal wildlife agencies have regulatory responsibilities that could have significant effects in the next decade on the SWP and CVP, BDCP, and the Legislature’s goals for the Delta. In particular, SWRCB’s update to their Bay–Delta Plan and other regulations could improve the Delta ecosystem by improving water quality or increasing the amount of water that flows into the Delta. Various governmental agencies also regulate individual projects in the Delta (such as ecosystem restoration or levee upgrades) in order to ensure compliance with laws that preserve water quality, navigation, cultural resources, and other aspects of the environment. Most projects require multiple permits from different agencies. For example, as many as 50 consultations or permits from federal, state, and local agencies could be needed in order to construct the facilities associated with BDCP.

State and Federal Agencies Support Ecosystem Restoration. Several state agencies have a role in ecosystem restoration in the Delta. As the operator of the SWP, DWR is responsible for habitat restoration mandated by wildlife agencies under the state and federal ESA. DFW directly performs ecosystem restoration activities in the Delta, as well as gives grants for similar activities to entities such as nonprofit environmental organizations. The USBR and federal wildlife agencies also directly perform and fund ecosystem restoration activities.

Local Flood Control Agencies Maintain Levees. Over 100 local agencies are responsible for maintaining levee systems in the Delta, which range in length from less than one mile to 50 miles. However, many of these agencies do not have the financial resources to maintain levees. This is primarily because of (1) constitutional limits on increasing property tax assessments, (2) a reluctance of property owners to pay increased taxes, and (3) the difficulty in ensuring that all beneficiaries of levees—not just property owners in the Delta—pay for a share of levee improvements. To help protect the state’s interests in the Delta (such as state highways), DWR provides bond funding to local agencies for maintenance and upgrades, as well as directly performs work on levees.

Historical Delta Expenditures

Most Spending for Water Supply Reliability and Ecosystem Restoration. A variety of activities in the Delta have been taking place for many years. These activities include studies and projects to improve water supplies, ecosystem restoration plans and projects, upgrades to Delta levees, and plans and projects to improve water quality. Since 2000–01, the largest areas of spending have been for water supply reliability (such as for BDCP planning and studies to identify potential sites for reservoirs) and ecosystem restoration. In more recent years, expenditures for levee maintenance have increased significantly, taking up a larger share of annual Delta spending. This is largely due to the passage of Proposition 1E and Proposition 84 in 2006, which provided significant additional funding for levees. Figure 7 shows average annual state and federal spending on the Delta by category. (In addition, local governments spend money on Delta–related projects such as levee improvements or wastewater treatment.)

Figure 7

Delta Expenditures Have Increased, Mostly Due to Spending on Levees

Average Annual State and Federal Expenditures (Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2000–01 to 2005–06

|

2006–07 to 2013–14

|

Change

|

Percent Change

|

|

Water supply reliability

|

$175

|

$124

|

–$50

|

–29%

|

|

Ecosystem restoration

|

116

|

116

|

—

|

—

|

|

Coordination and science

|

28

|

51

|

23

|

83

|

|

Levees

|

18

|

109

|

91

|

509

|

|

Water quality

|

17

|

30

|

13

|

79

|

|

Totals

|

$354

|

$431

|

$77

|

22%

|

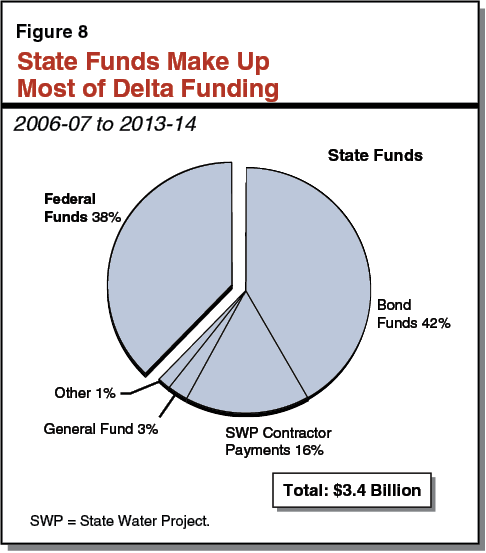

Most Spending on Delta Activities Since 2006–07 From State Funds. Between 2006–07 and 2013–14, state and federal agencies spent a total of $3.4 billion on Delta–related activities (including BDCP). As shown in Figure 8, more than half of the funding came from state resources—specifically, from voter–approved state bond funds (42 percent), revenues from SWP contractors (16 percent), and other state sources (4 percent), including the state General Fund. The remaining 38 percent of expenditures were supported with federal funds.

As noted above, there are several ongoing efforts to achieve the Legislature’s goals of ecosystem restoration in the Delta and ensuring the state’s water supply. While these efforts can progress without additional legislative action, there are many opportunities for the Legislature to improve the success of these efforts. Figure 9 summarizes five of the most significant issues for the Legislature to consider addressing to ensure successful implementation of legislative policies in the Delta. Some of these issues are similar to those faced by policymakers in the past. Failing to address these issues would likely increase costs and could delay progress, resulting in significant effects on the Delta ecosystem, the state’s water supply, and Delta residents. We discuss each issue in more detail below.

Figure 9

Issues for Legislative Consideration

- Managing and Prioritizing Demands for Delta Water

|

- Funding Sources for Some Key Delta Activities Is Uncertain

|

- Current Delta Governance Limits Effectiveness

|

- Slow Implementation of Some Key Activities

|

- Challenges to Restoring the Delta Ecosystem

|

Managing and Prioritizing Demands for Delta Water

The Delta is affected by statewide water use and policies that determine how water is managed in the state. To ensure that the Legislature’s goals for the Delta are achieved, it is important that Delta exports are considered within the context of the state’s overall water system. The Legislature may wish to consider providing direction on how demands for Delta water throughout the state are prioritized and managed.

Diversions in the North and Groundwater Management Statewide Affect Delta

Efforts to address the problems in the Delta may be more successful if the state comprehensively examines water use and other factors that originate outside of the Delta. This is because demands by other users diminish the flows needed to benefit some species in the Delta. The Legislature could consider the impacts of other sources of pressure on the Delta, including diversions in the north and groundwater pumping.

Water Diverted Prior to Reaching the Delta. Certain segments of the state—including San Francisco and the East Bay, other parts of Northern California, and the east side of the San Joaquin Valley—rely on water diverted from rivers and streams that feed into the Delta. In an average year about half of the water that would naturally flow out of the Delta to the San Francisco Bay is diverted for use elsewhere. About 60 percent of that water is taken out from upstream of the Delta, such as for use in the Sacramento Valley and the Bay Area. Those areas use water that would naturally flow into the Delta but is diverted before it reaches the Delta. An additional 8 percent is diverted by water users in the Delta. These demands are regulated through SWRCB’s water rights system. However, prior to 2013–14, they had not faced significant restrictions since 1978. (We note that the remaining 32 percent of the water diverted is exported south of the Delta by SWP and CVP. These demands are subject to ESA rules in addition to water rights regulation, as described above.)

Groundwater Management Can Affect Demand for Delta Water. Groundwater overdraft (withdrawing more water than can be practically replenished over an extended period of time) in other parts of the state can increase demand for Delta exports as water users attempt to replenish groundwater storage. We note that in 2014 the Legislature passed and the Governor signed major legislation that requires improved groundwater management in many parts of the state. However, improving groundwater management may require additional surface water supplies—potentially from the Delta—to replenish overdrafted basins. The DWR is required to publish a report on water available for replenishment in 2016. The Legislature may wish to provide direction to DWR on how much Delta water should be relied on for replenishing groundwater.

“Reduced Reliance” Not Clearly Defined

The Delta Reform Act established the goal of reducing the state’s reliance on the Delta for water in order to benefit the Delta ecosystem and increase water supply reliability throughout the state. However, that goal can have multiple interpretations. Reduced reliance can mean reducing the amount of water taken from the Delta and the rivers that feed into it. This could be done through either (1) fewer diversions from the Delta itself or (2) fewer diversions from the rivers that feed into the Delta. Alternatively, reduced reliance on the Delta could simply mean increasing the use of other sources of water to meet an overall increase in water demand. Implementing reduced reliance in this manner would make water exported from the Delta a smaller share of overall water use in the state without necessarily reducing Delta exports.

Definition of Reduced Reliance Determines Who Bears Costs. Achieving any one of these interpretations potentially involves different actions by state and local agencies, and these actions would have different effects on the environment and water users. For example, reducing diversions from the Delta itself would potentially result in costs to users in southern and coastal California that get water from SWP and CVP. Those costs would include lost productivity due to fallowing land or more expensive urban water supplies. Reducing diversions from the rivers that feed into the Delta would result in similar costs, but those costs would also be partially born by those in Northern California who would use less water. Finally, making Delta exports a smaller share of future water use would require additional expenditures on infrastructure to (1) maintain historical Delta exports, for example by implementing BDCP and (2) create new water supplies, such as by building plants to recycle or desalinate water. Reducing diversions or exports could also have greater benefits for species and the environment than if Delta exports remain the same. It will be important for the Legislature to clarify the meaning of reduced reliance.

Other Water Sources and Policies Can Lessen Demand for Delta Water

The amount of water that needs to be exported from the Delta to ensure the state has an adequate water supply depends on many factors, such as the availability of alternative water supplies, the total demand for water, and how state policies that affect water use and availability are implemented. Currently, no explicit policy identifies how much Delta water should be used to meet the state’s needs, or how much the state should rely on alternative sources or reductions in water demand. However, the administration’s decision to pursue BDCP has implications for what it considers to be the amount of Delta exports that are needed to meet the state’s demands. Specifically, if BDCP were implemented, Delta exports would remain roughly around historical levels. This level of exports is based on certain assumptions about other factors (such as total water demand). However, BDCP does not consider alternative scenarios for many of these other factors. For example, BDCP does not include modeling to assess how water consumption in the future would respond to different economic conditions or how future land–use patterns and changes in the state’s agricultural industry would affect demand for water. (The United States Environmental Protection Agency raised similar concerns in a comment letter during the public review of BDCP.) Such an analysis would help the state identify the most cost–effective approach to ensuring adequate water supplies, and at the same time provide a broad range of benefits.

Some stakeholders have suggested that the Legislature consider additional options to lessen demand for Delta exports. For example, the Legislature could influence what mix of supplies is most cost–effective by levying a charge on diversions from the Delta watershed. It could also provide grants to support water sources that could replace water exported from the Delta. For instance, voters recently approved the Water Quality, Supply, and Infrastructure Improvement Act of 2014 (Proposition 1), which includes funding for alternative water sources such as desalination.

Funding Sources for Some Key Delta Activities Is Uncertain

Many of the activities proposed in BDCP and the Delta Plan to achieve the coequal goals require funding. Some of the costlier activities are described below.

Significant Costs From BDCP Would Require Funding

BDCP Estimated to Cost $24.7 Billion Over 50 Years. As shown in Figure 10, DWR estimates that the one–time capital costs for BDCP will total $19.9 billion, including $14.5 billion for construction of the Delta conveyance tunnels and $5.4 billion for projects related to ecosystem restoration. The DWR also estimates ongoing operations and maintenance costs will total $4.8 billion, including $1.5 billion for the tunnels and $3.3 billion for ecosystem restoration over 50 years. Thus, the total estimated cost of the project over the 50–year term of the permits that authorize its operation is $24.7 billion. The actual costs could be higher or lower than estimated. However, we note, based on our review of the research, very large public infrastructure projects cost one–third more than budgeted, on average.

Figure 10

Summary of Estimated Future Bay Delta Conservation Plan Costs

(In Billions Over 50 Years)

|

Capital

|

|

|

Conveyance

|

$14.5

|

|

Ecosystem restoration

|

5.4

|

|

Capital Subtotal

|

($19.9)

|

|

Operations

|

|

|

Conveyance

|

$1.5

|

|

Ecosystem restoration

|

3.3

|

|

Operations Subtotal

|

($4.8)

|

|

Total

|

$24.7

|

Sources of Funding for Some BDCP Costs Are Uncertain. According to BDCP, the water contractors that receive water from the tunnels would pay for all of their construction and maintenance costs—as well as its associated mitigation—through increased water charges. This is consistent with how the existing SWP has been funded, although there is uncertainty about the number of contractors that are willing or able to pay those costs.

In addition, the likelihood of some other funding sources identified in BDCP materializing is uncertain, including funding for additional planning and ecosystem restoration. In particular, the BDCP identifies the state and federal governments as the primary potential funding sources for ecosystem restoration, which would mean significant new financial responsibilities for the state. Moreover, some of the proposed funding sources, such as state funding from the sale of water bonds, are uncertain. Specifically, BDCP assumes that $1.5 billion in state funding will be made available for ecosystem restoration by the passage of a water bond in 2014. However, the recently approved water bond measure, Proposition 1, includes only $140 million that could be used for Delta ecosystem restoration—less than 10 percent of the anticipated amount. If bond funds are not available in the near future and additional funding sources are not identified, some ecosystem restoration might not be funded, including some habitat restoration that needs to occur in order to determine how much water can be exported by the BDCP tunnels.

In addition, BDCP proposes to establish a Supplementary Adaptive Management Fund that would be available to support additional activities under BDCP. The uses for this fund are not specified in detail, but could include purchasing water or restoring additional habitat in order to enable increased pumping. The plan proposes a funding level of at least $450 million, to be provided by the water contractors, the state of California, and the federal government. Thus, establishing this fund could result in significant additional costs to the state.

In addition, contractors have voluntarily provided funding for planning BDCP, and that funding is likely to be exhausted soon. Specifically, the contractors have agreed to provide a total of $240 million for BDCP planning. As noted above, $202 million (84 percent) of that amount has been spent to date. If planning activities continue, such as for more changes to environmental documents, additional funding may need to be identified. Although the amount of future planning costs is unknown, it could be in the low tens of millions of dollars based on average annual expenditures on planning activities up to this point.

Determining the Role of State Funding for Delta Plan Activities

Delta Plan Implementation Costs Unknown But Potentially Significant. A variety of activities may potentially be required in order to implement some aspects of the Delta Plan, such as upgrading levees, restoring additional habitat, or strengthening infrastructure to support the Delta as an evolving place. The costs of these activities have not been estimated, but could include expenditures for levees, economic development, and compliance with new regulations. We note that CALFED identified about $8 billion in similar Delta projects. It has not been determined who would pay the costs for such projects.

State Funding Sources Are Limited. At this time, there is limited state funding available for Delta–related costs. Moreover, the Delta will have to compete with other projects, such as flood control projects in other parts of the state, for some of these funds. Based on the most recently available information (August 2014), about $130 million in funds from the 2006 water bonds remains available specifically for Delta activities. (This does not include Proposition 1E, which has allocations that can be used for multiple types of flood control projects throughout the state, including Delta levees.) However, some previously appropriated bond funds might become available in the future if they are not spent. For example, the 2014–15 Budget Act included provisional language that allows the DWR to expend $37 million for temporary barriers in the Delta to protect water quality during the current drought. As of December 2014, none of these funds have been spent.

Identifying Who Should Pay for Work in Delta. In our view, it is reasonable that some state funds be used to support some portion of Delta–related costs because certain projects would provide a broad public benefit to residents of the state. Such activities include helping endangered species recover. In addition, investing state funds in levee repairs and upgrades can reduce the need for future state expenditures associated with levee breaches, such as for emergency repairs and paying damage claims. However, some Delta–related activities envisioned primarily have private benefits, such as improving levees to protect private infrastructure or agricultural production. In addition, some activities will be performed in order to address harms that have been caused by specific polluters (such as cities or farms that produce polluted runoff). Thus, it will be important for the Legislature to consider what Delta–related activities are most appropriate to be funded by the state—such as with bonds—or with other funding sources, including charges on beneficiaries or polluters. For example, the Delta Plan includes a recommendation to charge individuals and entities that benefit from Delta levees (such as landowners in the Delta and water agencies that transport water across the Delta) for the cost of maintaining those levees. This could potentially increase funding available for levee maintenance.

It is also worth noting that the state’s activities in the Delta could impose significant costs on a small, concentrated group of Californians. Specifically, any negative impacts associated with BDCP or other efforts in the Delta—such as loss of agricultural land—will fall mainly on the small number of people residing in the Delta. To the extent that the Legislature is concerned about this, it could mitigate some of the impacts on certain stakeholders within the Delta (such as farmers).

Current Delta Governance Limits Effectiveness

The governance structure set up by the Delta Reform Act has resulted in some concerns about the effectiveness of efforts to address the problems in the Delta. Below, we describe issues related to enforcement and integration of Delta policies.

Delta Reform Act Provisions May Reduce Council’s Effectiveness

Delta Stewardship Council Lacks Power of Enforcement. The Delta Reform Act gave the Delta Stewardship Council the authority to decide whether certain actions proposed by state or local agencies—such as authorizing new development—are consistent with the Delta Plan and to offer recommendations if they are not. However, state and local agencies are not required to adopt the council’s recommendations. Yet, the act requires the Delta Plan to be “legally enforceable.” It is unclear how the Delta Plan would be enforced if agencies decide not to follow the Delta Stewardship Council’s recommendations. Consequently, it is likely to be difficult to hold the council or other state agencies accountable for their progress towards achieving the Legislature’s coequal goals for the Delta.

Exemptions to Delta Plan Could Limit Ability to Meet Goals. The Delta Reform Act exempts certain activities from complying with the Delta Plan. For example, the act exempts certain activities designed to meet other state policy goals. Specifically, certain local transportation plans that are developed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and make communities more sustainable are exempt from having to be consistent with the Delta Plan. In addition, all regulatory actions by state agencies are exempt from being consistent with the Delta Plan. If these activities have significant effects on the Delta, they could affect the ability to achieve the state’s goals in the Delta. For example, the state Fish and Game Commission, which regulates fishing and hunting, could approve regulations that restrict the number of predatory nonnative fish that can be caught in a season. This could result in an increase in these populations and, consequently, a decrease in native fish species that are preyed upon by the nonnative species.

Limited Integration of Regulatory and Planning Activities

As discussed previously, many agencies are responsible for carrying out activities in the Delta. Several reviews of Delta governance have found that decision–making continues to be fragmented, leading to a lack of integration among the various planning and regulatory activities in the Delta. For example, in 2014, the Delta Vision Foundation found that although some positive steps have been taken to improve how state agencies work together, there continues to be a lack of integration in several areas. One such area is water supply reliability, where the foundation found that interactions between potential water storage projects and BDCP were not being adequately considered by the administration. A lack of integration is likely to result in conflicting plans and regulatory actions, slowing progress on the state’s objectives. For example, some ecosystem restoration projects have been slowed by requirements for numerous, and sometimes duplicative, permits and environmental reviews at the state, local, and federal levels. PPIC has suggested establishing an entity to oversee all permitting in the Delta in order to streamline the permitting process by minimizing duplicative efforts.

To achieve success in the Delta, integration between state and federal activities will be especially important. One strength of CALFED was that federal agencies that played a key role in the Delta were formally incorporated into the governance structure and involved in planning the overall program and related outcomes. Under the current arrangement, state–federal partnerships generally occur on an ad–hoc basis or are related to specific, relatively narrow issues such as ecosystem restoration or BDCP. It will be important to incorporate federal agencies into plans and activities going forward because the federal government is expected to provide significant funding for many of the proposed activities and might also implement some of those activities. Federal agencies also can affect whether the state achieves its goals for the Delta through regulatory activities, which may either help to address problems or, conversely, slow efforts by other agencies to address them.

Slow Implementation of Some Key Activities

The Delta Reform Act states that the coequal goals shall be achieved in a way that protects and enhances the Delta as an “evolving place,” including protecting its natural resources, cultural value, recreational opportunities, and agricultural activities. However, the state has been slow to implement some actions that would help protect the Delta, including tracking of outcomes and a strategy for reducing flood risk. As a result, the state’s goals for protecting the Delta may not be achieved as the Legislature intended.

Slow to Track Performance Measures for Protecting the Delta. The Delta Plan includes some policies and recommendations intended to protect the Delta, and it includes some recommended performance measures for tracking related outcomes. For example, it includes a measure that no farmland in the Delta should be lost to urban development. However, the Delta Stewardship Council has not yet begun tracking any outcomes. Council staff indicated that they plan to release a report in mid–2015 describing progress on implementing the recommended performance measures. Tracking outcomes will be important for the success of efforts in the Delta. Without measures of outcomes, it will be difficult for the Legislature to hold the Council accountable for the state’s progress in this area and for the Council to learn from past activities in order to identify effective programs.

No Strategy for Reducing Flood Risk. The act directs the Delta Stewardship Council to develop a strategy for prioritizing state spending on levee repairs and upgrades, but the Council has only developed interim goals for developing priorities. One consideration in prioritizing levee investments is that the cost of mitigating risk from levee failures will depend on the specific characteristics of the Delta that the state wants to protect. For example, protecting agriculture in the Delta could require greater expenditures on levees widely throughout the Delta, while protecting state highways could require expenditures on only the levees that border them. Prioritization of which aspects of the Delta should be protected and a strategy that ensures those priorities are protected would help to ensure that flood risk is reduced in a cost–effective manner.

Challenges to Restoring the Delta Ecosystem

Difficult to Identify the Most Cost–Effective Ways to Restore the Ecosystem. As discussed above, the factors causing the decline of the Delta ecosystem interact in complex ways. For example, a change to the amount of water flowing through the Delta can increase or decrease the effects that other factors (such as water temperature and water quality) have on species in the Delta. Thus, it is difficult to rank the importance of factors in order to identify the most cost–effective ways to improve the Delta and help fish populations recover. As a result, improving ecosystem conditions will likely require addressing most factors to some degree. In addition, because of the interactions among different factors and natural changes from year to year, it could take decades to identify the actions that are most effective.

Adaptive management—periodically adjusting restoration policies and activities based on ongoing monitoring and evaluation—will be necessary to ensure that restoration is effective and efficient. However, the specific details of how adaptive management will be carried out and funded will significantly affect its effectiveness. Both the Delta Plan and BDCP are intended to include science programs that would form the basis for adaptive management, but how those efforts will be integrated remains unknown. If the programs do not work together successfully, state agencies could take conflicting actions that might reduce the overall effectiveness of actions in the Delta. For example, the programs may reach different conclusions on the effects of the BDCP tunnels on the Delta environment and therefore may have different prescriptions for how best to improve the Delta ecosystem. Furthermore, if separate, these programs could end up dividing available funding for similar adaptive management efforts.

Completing Ecosystem Projects Can Be Challenging. Many of the ecosystem restoration projects started under CALFED still have not been completed in the expected time frame. For example, studies for a restoration project on the McCormack–Williamson Tract began in 2000, but construction has been delayed repeatedly and the project is not estimated to be completed until 2015 or later. In general, reasons for delay cited by departments and others include difficulty in getting federal permits, funding constraints on local agencies that make it difficult for them to provide matching funds, and changes in how the state finances bond–funded projects. In addition, failing to respond to the concerns of Delta stakeholders can stall progress toward ecosystem projects. For example, purchasing land from willing sellers in order to restore habitat could require cooperation with Delta stakeholders.

Expenditures on the Delta are likely to continue and increase in the future. The Legislature has appropriated funding for Delta activities in the past and will continue to see requests in the future. In addition, although many activities to resolve the problems in the Delta are able to proceed without further legislative direction, the Legislature may want to provide additional statutory guidance in order to address the issues raised in this report. By doing so, the Legislature can improve the likelihood that its goals and objectives will be realized by offering additional guidance and specificity on many aspects of Delta policy.