November 6, 2002

The $2 Billion Question:

Providing Health Insurance for State Employees and Retirees

In recent years, the cost to provide health insurance coverage to state employees and

retirees has increased considerably. The state will pay $1.3 billion for these health

insurance premiums in 2002 and $1.7 billion in

2003. We review actions the Public Employees' Retirement System is taking to control these rising costs and highlight legislative options

to further limit the state and enrollee costs for

the health insurance program. We also recommend steps to further ongoing legislative

oversight of the program.

Introduction

Like many employers, the state provides health insurance coverage for its employees.

In addition, the state provides health insurance

for retirees from state service. The state pays

most of the monthly premiums for this coverage.

In recent years, health care costs have escalated nationwide. A number of factors

have contributed to these increases. Some of these factors are out of the control and influence

of the state as a buyer of health insurance coverage, while other factors are subject to

state control. This report looks at what the

Public Employees' Retirement System (PERS), which administers the state program, is currently

doing to control the state's health insurance costs

for its employees and retirees. It also examines

what the Legislature can do to control these costs.

Throughout this report, we focus on the health program as it impacts the state.

However, these issues and any program changes also would impact local governments that

contract with PERS for health services.

Current Health insurance Program

Administration of the Program

After the federal government, PERS is the second largest public purchaser of

employee health benefits in the nation and the largest

in California. The PERS administers the health insurance program for employees and

retirees of the state, as well as local governments

that contract with PERS to provide this service. Under current law, PERS determines the

health plan design, including:

- The types and level of services covered.

- The level of user fees, or "copays."

- The types of insurance offered—for example,

health maintenance organization (HMO) plans and

preferred provider organization (PPO) plans.

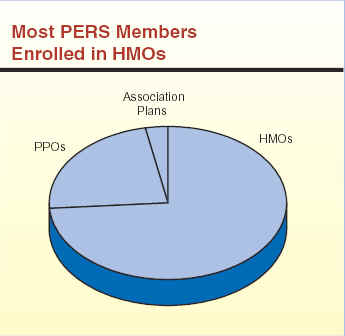

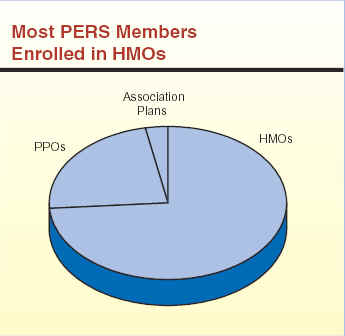

Currently, PERS offers enrollees a choice between seven HMOs and two PPOs. (As

we indicate later, the number of HMOs available to PERS enrollees in 2003 will decline to three.)

In addition, PERS offers three PPO options for specific groups of employees (primarily

highway patrol and correctional officers). Enrollees

who are 65 years of age or older must enroll in

the Medicare-coordinated plans offered by each HMO and PPO. Younger enrollees are

enrolled in the "basic" (non-Medicare) plans. The

health services covered by the participating HMOs

and PPOs are virtually identical. There are more

than 1.2 million individuals covered under the

PERS health insurance program, 60 percent of

whom are state members, with the remainder being local government members.

HMO Versus PPO Plans. There are

important similarities and differences between

HMOs and PPOs. They are similar in that both types

of organizations contract with specific sets of

doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers

to provide services to enrolled members. Also,

both HMOs and PPOs attempt to manage the delivery of health care services to members, although

the extent of this control is less under PPOs.

And herein lies a significant difference between these plans. The HMOs require

the provision of care through a primary care provider who determines whether referrals

to specialists are warranted. By contrast, PPOs permit enrollees to obtain services from

specialists without referral.

Other differences exist between HMOs and PPOs. In general, an HMO enrollee

who receives services outside of an HMO network has to pay the entire costs of those services.

In contrast, the PPO enrollee who obtains services outside of the provider network would not

pay the entire cost of the services, although

he/she would pay a greater portion than if the

service had been delivered by a contracted

provider. Finally, HMOs tend to prepay providers a

per-capita rate for each enrollee (known as capitation), while PPOs generally pay providers on

a discounted fee-for-service basis. Because of these differences, HMO coverage tends to

be less expensive than PPO plans.

The PERS contracts with HMOs (such as Kaiser Permanente and Blue Shield) to

offer HMO plans to employees and retirees at premiums negotiated by PERS and the

individual companies. Thus, these HMOs bear the

financial and legal risk of administering these

health plans if, for example, revenues do not

cover expenses. On the other hand, PERS bears the financial and legal risk of operating the two

PPO plans it offers. This type of arrangement is known as self-insurance and is not

uncommon among large employers.

Premiums Set in Spring for the Next Calendar Year.

The PERS staff negotiates premiums with the HMOs at the beginning

of each calendar year for the following calendar year. These negotiated premiums are

then reviewed and approved by the PERS board during the spring. For example, the

premiums that will be in effect for 2003 were

negotiated and approved during the first part of 2002.

All contracting HMOs must provide the same set of covered services, as designated

by PERS. The negotiated premium for each HMO is the same throughout the health plan's

service area and does not vary from one region of

the state to another.

As indicated above, PERS does not contract with health plans for the PPOs. Instead, PERS

is responsible for administering the program (with the aid of contracted third-party

administrators) and setting premiums at sufficient levels

to cover medical costs. As with the HMOs, the PERS board also sets PPO premiums in

the spring for the next calendar year.

PERS Health Plans, 2002

Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs)

Blue Shield Access+HMO

Health Neta

Health Plan of the Redwoodsa

Kaiser Permanente

PacifiCarea

Universal Carea

Western Health Advantage

Preferred Provider Organizations (PPOs)

PERSCare

PERS Choice

Association Plans

California Association of

Highway

Patrolmen Health Benefits Trust

California Correctional Peace Officers

Association

Peace Officers Research Association of

California

aNo longer available for 2003. |

|

State Costs to Provide Health Insurance

Existing law declares that the state's purpose

in providing health insurance to its employees and retirees is to

promote increased efficiency in state government

by (1) attracting and retaining employees

through providing health plans similar to those available

in the private sector and (2) protecting the state's

labor investment by maintaining employees' good health.

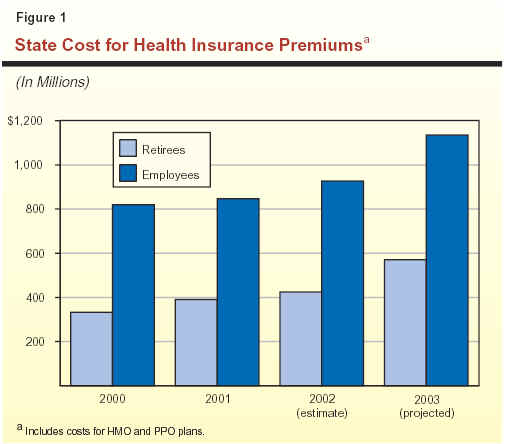

In 2002, the total cost (state and employee contributions) of health insurance premiums

for state employees and retirees will be about $1.6 billion. This includes about $1.1 billion

to provide coverage for active employees and their dependents and more than

$500 million for retirees and their dependents. Of the

total amount, the state will pay more than

$1.3 billion while employees and retirees will pay

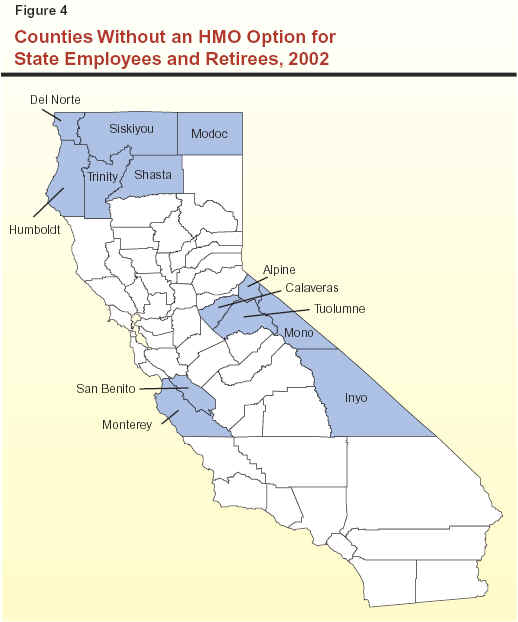

the remainder. Figure 1 shows the growth in

the state's share of costs since 2000.

We estimate that the total 2003 cost for health insurance will exceed $2 billion, with

the state paying $1.7 billion of this amount.

State Contribution for Employees Subject to Collective Bargaining.

Current law requires the state contribution for employees'

health insurance premiums to be determined through collective bargaining. The Department of

Personnel Administration (DPA) establishes the

state contribution for those

employees—including managers and supervisors—who are not

subject to collective bargaining. Under new

memoranda of understanding (MOUs) approved by the Legislature for all 21 bargaining units,

the monthly state contribution for 2002 is $190

for one-party, $378 for two-party, and $494 for family enrollment. This amounts to the

state paying 85 percent of health insurance

premiums for employees and their dependents.

Employees pay the remaining 15 percent.

Statutory Formula Determines State Contribution for Retirees.

On the other hand, current law requires the state to pay

100 percent of a weighted average premium for

retirees and 90 percent of the additional

premiums for their dependents, depending on years

of state service. This is known as the

"100/90 formula." The weighted average premiums

are calculated based on the premiums of the four health plans with the highest enrollment.

This calculation results in monthly state

contributions of $216 for one-party, $411 for two-party,

and $525 for family enrollment in 2002. (If the premium for the health plan selected by

a retiree is lower than these maximums, the state pays the lesser amount.) This amounts to

the state paying 81 percent of premiums for

retirees and their dependents.

State Cost for Employees' Coverage

"Buried" in Departments'

Budgets. While the state annually pays a substantial amount for its

share of health insurance premium costs for state employees, the total cost to the state cannot

be easily identified in the budget. This is

because funding for these costs is spread throughout

the budget. Specifically, the bulk of the state's

cost for employee coverage is included in the base budgets of individual departments, as part

of personal services costs. However, the

additional costs that the state has to pay as health

insurance premiums grow from one year to the next are separately appropriated in a lump sum in

the annual budget act (under Item 9800, Augmentation for Employee Compensation). This

amount supplements the baseline allocations

embedded in individual departmental budgets.

Pursuant to annual budget language, the Department of Finance allocates the

appropriated amount for the higher premiums to

individual departments' budgets. For 2002-03, the budget includes $163 million for the

state's portion of premium increases. When

allocated to individual departments, these

additional health insurance costs also become buried

in departments' baseline budgets in the subsequent year. We estimate that state costs

for current employees (excluding the portion of premiums paid by employees themselves)

are approaching $1 billion in 2002, as shown

in Figure 1.

State Cost for Retirees' Coverage Appropriated in Budget Line

Item. In contrast, the annual budget act includes a line-item

appropriation (under Item 9650, Health and Dental Benefits for Annuitants) for state retirees'

health insurance costs. (Although PERS administers

the program on a calendar-year basis, the state appropriates funding for its share of costs on

a fiscal-year basis.) This provides the

Legislature the opportunity to review these

premium expenditures during budget hearings. The budget includes $577 million for these

state costs in 2002-03.

Additional Program for Higher-Cost Rural

Areas. The total cost to the state to

provide health insurance for state employees and retirees is, in fact, somewhat more than

the $1.3 billion for premiums cited above for

2002. This is because in recent years, HMOs have dropped rural areas from their service

territories for a number of reasons, including the

higher cost of care in those regions compared to urban areas. In particular, factors driving up

rural costs have included greater use of costly

regimens in treating medical conditions and fewer available doctors and hospitals. (Please see

our report HMOs and Rural California for a

more detailed discussion of this issue.) As a

result, state employees and retirees who live in

these rural areas must enroll in one of the

higher-cost PPO plans, which are available

statewide. Consequently, state employee and

retiree enrollment in PPOs has increased.

In order to provide insurance at a similar level of cost to all enrollees (including those

in rural areas), the state established the Rural Health Care Equity program, administered

by DPA. This program subsidizes health care costs for employees and retirees in rural

areas. Generally, the program reimburses (1) out-of-pocket health care costs that would normally be covered by an HMO, such

as deductibles and co-insurance payments (typically a percentage of the cost of service), and

(2) the difference in premiums between the lower cost of the two PPO plans available to

those eligible and the average HMO premium. The budget act includes $32 million for this

program in 2002-03 (under Item 8380, DPA).

The growth in PPO enrollment also drives up the state's health insurance costs in

another way—indirectly, via the weighted average

premium formula used to calculate the state's contribution for retirees' premiums.

Because HMOs have withdrawn from rural areas, one

of the state's PPO plans now is among the top four in enrollment. As a result, this

higher-cost PPO plan now drives up the state

contribution for retirees' premiums at a faster rate

than previous increases.

State Costs Increasing; Will Continue to Escalate

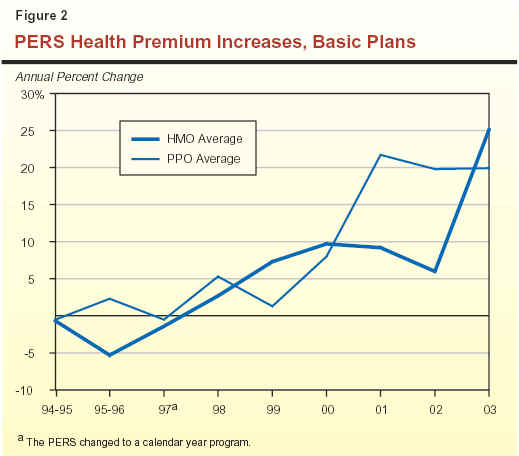

Like other employers, the state has experienced escalating cost trends for health

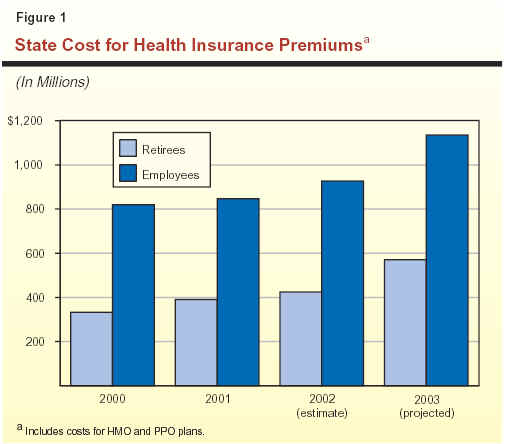

insurance. As a result, premiums have grown considerably in recent years. Figure 2 (see next

page) shows the average premium increases adopted by PERS from the mid-1990s through 2003

for the basic (that is, non-Medicare) HMO and PPO plans.

As Figure 2 shows, HMO premiums have increased by more than 5 percent annually

since 1999. In 2000, the increase approached

10 percent. The increase in HMO premiums dampened for 2002 as a result of plan

changes adopted by PERS to increase enrollees'

out-of-pocket usage fees ("copays") for office

visits and prescription drugs. Without these plan changes, the average HMO premium

increase would have been 13 percent instead of

6 percent. The high 25.1 percent jump for

2003 reflects the current cost pressures on the

health care system, as described below.

Figure 2 shows that from 2000 through 2002, average premiums have increased

even more dramatically for the two PPOs administered by PERS. This reflects mainly

PERS'

efforts to restore the plans' financial solvency,

which has been strained by growing costs and high enrollment growth. The PERS began

these efforts to "catch up" plan reserves in

December 2000. At that time, because of the trend

toward increased levels of treatment and growing enrollment due to

HMO withdrawals from rural areas, the PPOs faced $9 million more in

costs than they had in reserve. In 2002, PPO

premiums increased by an average 19.8 percent, and

PERS adopted a 19.9 percent increase for these

plans for 2003.

Cost Increases Expected to Continue.

Various factors affect the cost of health care.

In recent years, the following factors have

contributed to upward pressure on state health care insurance premiums:

- Increasing cost and use of prescription drugs.

- Higher payments to doctors and hospitals for patient care.

- Greater levels of treatment provided to and used

by patients (including new high-cost technologies).

- An aging population.

These factors are expected to continue driving up the cost of health care and

therefore health insurance premiums.

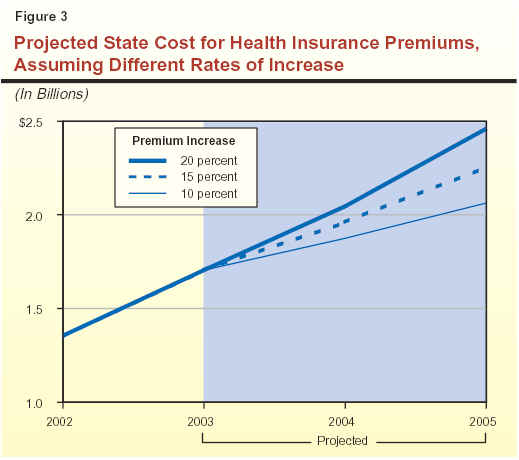

Based on these recent trends, last fall PERS estimated annual premium increases of

15 percent for the HMO and PPO plans from

2003 through 2005, absent changes in program structure. However, recently concluded

premium negotiations for 2003 resulted in much larger-than-anticipated 25.1 percent

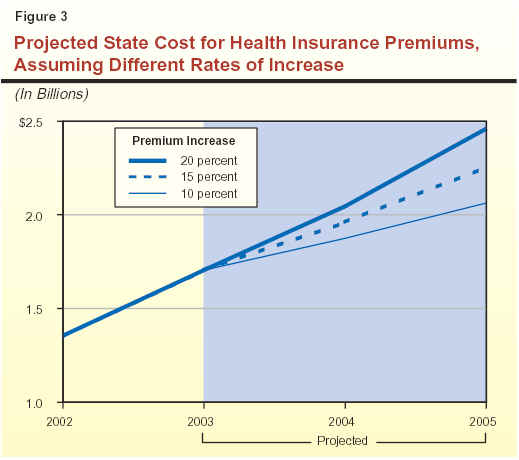

and 19.9 percent increases for HMOs and PPOs, respectively, as noted above. Figure 3 shows

the cost to the state if premiums increase at PERS' estimated 15 percent rate for 2004 and

2005, assuming the state continues to pay its

current share of health insurance premiums. The

figure also shows the cost to the state if

premiums were to increase at lower (10 percent)

or higher (20 percent) rates. As shown in the figure, the PERS projection of 15 percent

would result in state costs increasing from

$1.3 billion in 2002 to more than $2.2 billion by 2005.

On the other hand, if premiums increase at a

smaller annual rate of 10 percent, the state's cost

would be just over $2 billion in 2005. An

annual increase of 20 percent would result in

state costs of nearly $2.5 billion by 2005.

Given the magnitude of these costs, significant dollar savings are possible with even

small reductions in premium growth. Specifically,

a 1 percent reduction in premium costs would save the state around $20 million.

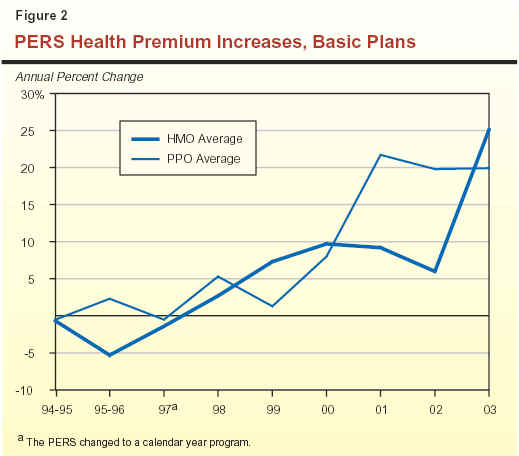

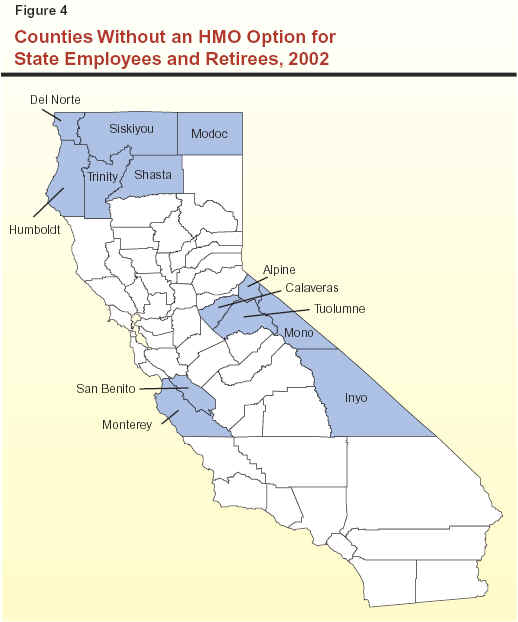

HMOs Dropping Rural Areas Pushes Up Cost.

As discussed earlier, HMOs have dropped certain rural areas entirely from their

service territories because of the higher cost of care

in those regions compared to urban areas. Individuals in these

counties without HMOs must enroll in more costly PPO plans

administered by PERS, which are available statewide.

Figure 4 shows the counties that currently do

not have any HMOs under the PERS program. (There may be

HMOs serving private sector employees in these counties, but not

state employees and retirees.) In 2002, as a result of HMOs leaving rural

areas, state employees and retirees in 13

California counties no longer have an HMO option.

This number will grow to 15 in 2003 with the planned withdrawal of HMOs from Lassen

and Tehama Counties. In addition, parts of nine counties are without an HMO, and this

number will also grow to 15 in 2003.

PERS Attempts to Rein in Growing Costs

Despite its relatively small share of HMO enrollment in California (5 percent to

10 percent for each HMO), PERS has, to date,

been successful at keeping premium increases down. In the 1990s, PERS negotiated very low

premium increases and even reductions in some years. More recently, as discussed

earlier, premium growth has been quite sizable,

largely due to widespread health care cost pressures.

Historically, PERS has successfully negotiated some of the lowest HMO premium increases

in the country. For example, the Kaiser Family Foundation reported that monthly premiums

for private sector employer-sponsored HMO coverage in California jumped 9.9 percent

for 2001, compared to PERS' 9.2 percent

increase. For 2002, federal government employees' health insurance premiums rose

13 percent. Similarly, members of the Pacific Business

Group on Health, which purchases insurance on

behalf of large and small businesses, faced 10 percent

to 20 percent jumps. At the same time, PERS negotiated a 6 percent average premium

increase for its HMOs in 2002.

2002 Premium Negotiations

As part of its efforts to limit cost pressures during HMO contract negotiations for

2002 premiums, PERS rejected the original

proposals submitted by HMOs because of the

magnitude of premium increases requested. Proposed increases for the basic plans ranged from

5.5 percent to 41 percent, averaging

23.3 percent. Instead, PERS required the HMOs to

resubmit lower bids for the existing plan design, as well

as provide bids for two alternative plan designs

that would help limit premium costs. The PERS also announced that it would only contract with

up to seven health plans to be selected based on various performance statistics and price.

Figure 5 shows the weighted average premium

increases for the original and resubmitted bids for

the existing plan design, as well as for the

alternative plan design that PERS subsequently adopted.

|

Figure 5

2002 HMO Premium Bids

Basic Plans

|

|

Proposals

|

Percent

Increase

|

|

Original

|

23.3%

|

|

Resubmitted

|

13.2a

|

|

Adopted (higher copay)

|

6.0a

|

|

|

|

a

Seven adopted HMOs only.

|

In the end, PERS contracted with seven HMOs, eliminating

three from its list of 2001 contracts, and adopted the alternative

design that increased enrollees' copays to further

limit monthly premium increases. Specifically, PERS increased

copays for doctor's office visits from $5 to $10, which

is the most common amount among California businesses,

according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey. It also implemented

a three-tiered prescription drug copay schedule to encourage enrollees

to use less expensive generic and mail-order drugs. The PERS had

not changed these provisions since the early 1990s.

The PERS estimated that rejecting the initial bids and requiring the health plans to

resubmit new bids lowered total HMO premium costs

for state employees and retirees by

$105 million. Adopting the higher-copay plan further

dropped the premium increase to 6 percent. This

shaved another $82 million off the cost, according

to PERS.

2003 Premium Negotiations

In negotiations for 2003 premiums that would be effective January 1, 2003, PERS

again faced proposals for very high premium increases. Proposed increases for the

existing plan structure averaged 30 percent for the

basic plans. The PERS also requested bids for

alternative plan designs. Alternatives submitted by

the HMOs for consideration included:

- Tiered hospital coverage—with copays ranging from $100

to $1,000 per admission or per day for choosing nonpreferred, more expensive hospitals.

- Changes in prescription drug coverage—with higher

copays (up to 50 percent for brand-name prescriptions) and

higher annual maximum for drug costs paid by the enrollee.

In the end, the PERS board rejected any plan design changes that called for smaller

premium increases and higher out-of-pocket costs

for enrollees. Instead, the board voted to

contract with only the five HMOs with the smallest premium increases, eliminating two HMOs

from its 2002 choices for enrollees.

(Subsequently, two of the five HMOs could not meet

conditional requirements regarding their financial stability and therefore were not included in

the 2003 state program.) This reduced the average premium increase to 25.1 percent. The

PERS estimated that reducing the number of HMOs it contracts with will save $45 million for

state employees in 2003. However, total estimated HMO premiums will still jump by

nearly $300 million to $1.3 billion.

What Else Is PERS Considering?

Beyond its actions relating to the 2002 and 2003 premiums, PERS is pursuing

additional options to rein in growing premium

costs. These options, which are not mutually

exclusive, include the following.

Prescription Drug "Carve-Out."

To address escalating drug costs, PERS is investigating

the feasibility of having a separate carve-out

contract for prescription drug coverage for some or all

of the HMO plans beginning in 2004. Under this arrangement, individual plans would not

provide pharmaceutical coverage. Instead, there

would be a separate contract with one provider to supply prescription drugs for all HMO enrollees.

Currently, one company provides prescription drug coverage for both PPO plans.

By contrast, each HMO provides prescription coverage as part of the plan. Under this

option, bidders for the new contract to provide

prescription coverage to PPO enrollees would have to

be able to serve HMO enrollees as well beginning as early as 2004. Until PERS determines

an estimate of savings from a pharmacy carve-out contract for HMO enrollees, the likelihood

that PERS will implement this option remains unclear.

Data Warehouse Project. The

2002-03 budget includes first-year funding of

$3.5 million for PERS to develop a Health Care

Decision Support System (HCDSS). The project

involves the purchase of off-the-shelf software to

establish a "data warehouse" consisting of

information on the use of medical services and

prescription drugs by those enrolled in the PERS

health program. One-time acquisition costs would

total $6.2 million, with $3.3 million in ongoing

annual costs to support the system beginning in 2004-05.

The PERS indicates that medical and pharmaceutical claims information from HCDSS

would be used to improve patient care and help contain increases in health insurance

premiums by identifying the most prevalent and

costly illnesses, the most effective treatment

regimens, and individual health plans' treatment costs.

The PERS anticipates HCDSS to be functioning in 2004 so that PERS could use data from

the system in negotiations for 2005 health

insurance premiums. Specifically, it is anticipated that

PERS would know actual treatment costs for each HMO with which it contracts. This

information would be used to negotiate premiums

that better reflect actual cost trends. The PERS estimates ongoing premium savings

from HCDSS that would accumulate from year to year—an estimated additional $10 million

in savings each year.

Regional Premiums. The PERS has

also considered adopting some form of

"regional rating" so that premiums reflect the actual

cost of service in various areas of the state.

Currently, each health plan has a uniform statewide

premium schedule for all of its service areas. However, under a regional rating

structure, PERS would divide the state into a number

of regions and allow HMO premiums to vary among regions based on actual treatment

costs. This could induce HMOs to provide services

in higher cost rural areas, and reduce the impact on total premiums resulting from the

withdrawal of HMOs from rural areas.

County-specific information from PERS demonstrates the variability in treatment

costs, which would be reflected, to some degree,

in premium charges under this proposal. For example, per-member monthly HMO

treatment costs range from $109 in the urban south

(San Diego, for example) to $159 in rural areas (Shasta, for example), with a statewide

average of $120. Monthly PPO treatment costs per member range from $171 in the suburban

south (Riverside, for example) to $189 in the

urban north (Contra Costa, for example), with a statewide average of $183.

The HMOs have indicated to PERS that full regional rating, under which premiums

reflect actual costs, may mean that they could stay

in their existing rural areas. This is because

full regional rating would reduce the cost uncertainty associated with HMOs' existing

service territories by allowing the plans to

charge premiums that are in line with their costs

in these more expensive areas. However, HMOs have also indicated that a regional rating

system would not induce them to restore service to areas from which they have already

withdrawn. This is because HMOs have expressed a lack

of interest in reentering high-cost rural areas

under the current PERS program. Consequently, although regional rating could help stem

the tide of HMO withdrawals from high-cost rural areas, it would likely not reverse the

pull-outs that have already occurred.

Fewer Plan Choices, But Statewide Coverage.

The PERS is also considering two major proposals that would further limit the number

of health plan choices of enrollees. These proposals would, however, ensure that the

limited choices are offered statewide, thereby

eliminating the problem of HMOs pulling out of

rural areas. Nonetheless, PERS is only beginning

to develop these proposals and the likelihood of eventual implementation is uncertain at this time.

The first proposal would include three HMO choices with service territories

covering the entire state, instead of HMOs in only

selected parts of the state as is the case

currently. Under the second option, the state would,

like other states and large employers, become self-insured for all enrollees instead of just for

PPO members. The program would offer two or more insurance products (an HMO and a

PPO plan, for example). The PERS estimates significant cost savings for each of these proposals.

Current Law Leaves Legislature Out of the Process

As PERS considers these program design changes, current law leaves the Legislature

out of the process of determining the provisions of the state's health insurance program for its

employees and retirees, as well as how much to pay for it.

PERS Establishes Health Insurance Program.

Existing statute requires the PERS board to

establish the scope and content of health benefits

plans, taking into consideration (1) the "needs

and welfare" of employees and the state and

(2) "prevailing practices" in prepaid medical and

hospital care. No legislative review of the health

plan design is required.

State Cost for Employees Reflects Administration's

Priorities. Under current law, the state contribution for employees'

health insurance—estimated to surpass $1 billion

in 2003—is determined through collective

bargaining. Agreements the administration reaches

with the bargaining units on this item reflect the administration's priorities. Typically,

negotiated MOUs reach the Legislature at the last

minute before the end of session and are often not reviewed in committee hearings. This

occurs despite a statutory requirement that MOU provisions requiring an appropriation must

be approved in the budget act. In practice, the Legislature has little opportunity to

consider state expenditures in this area.

Different Levels of Legislative Oversight Possible

The PERS has over the years successfully negotiated some of the lowest premium

increases among large employers. However, given rising costs in the health care industry,

the Legislature may want to reconsider whether

this broad delegation of authority continues to

meet the state's needs and priorities in the most

cost-effective manner.

There are different approaches the Legislature could use to strengthen its oversight. For

example, the Legislature could take a one-time action to direct PERS to develop

particular coverage choices or have annual budget oversight hearings on health insurance costs

for state employees and retirees. Alternatively,

the Legislature could direct PERS to report on the implications—in terms of cost and

coverage—of the various alternative plan designs that PERS

is currently considering.

Recommend Legislative Oversight On an Ongoing Basis

To provide the Legislature with ongoing information on a multibillion dollar program,

we recommend the following actions.

Annual Report in Budget Hearings.

The Legislature should require PERS to report annually in budget hearings on (1) the

total costs to provide health insurance for state employees and retirees; (2) the trends,

cost factors, and forecasts for the health care

sector; and (3) the steps PERS is taking to

address health care costs and other identified

issues. This would facilitate ongoing legislative

oversight of the program. Based on the information provided by PERS, the Legislature could

also determine on an as-needed basis whether to hold additional in-depth policy and fiscal

hearings. We believe that such oversight hearings are warranted, given that the costs of the

program are increasing dramatically and PERS is moving toward a more consolidated

program structure with fewer plan choices for

enrollees. Both types of hearings would provide

the opportunity for the Legislature to direct

PERS' efforts to reflect legislative priorities and to

make policy changes in the health insurance

program for state employees and retirees.

Consolidated Display in Governor's Budget.

We also recommend that the Governor's budget bring together in one location a

consolidated informational presentation of total

health insurance costs for state employees. This

would improve legislative oversight of total state

expenditures for this purpose. This is similar to how

the state has dealt with expenditures across

multiple departments for the CALFED Bay-Delta program.

Specifically, the informational display should list the number of state employees enrolled

and the cost of health insurance, broken down by (1) HMO and PPO enrollment and (2)

agency. This would make it easier for the Legislature

to identify the growth of program expenditures. Such a consolidated display, together

with budget information currently provided on

health insurance coverage for retirees, would give

the Legislature a more comprehensive picture of the state's health insurance costs for current

and past employees.

Legislative Options to Limit Costs

In addition to increasing oversight, we identify two primary ways that the

Legislature could limit total costs for employee and

retiree health insurance premiums paid both by the state and by enrollees. The first

approach focuses on developing lower-cost HMO options. This approach emphasizes the

development of health plan choices that limit

total premiums—both those paid by the state and

by enrollees. The second option changes the way state contributions are determined. In particular,

it focuses on the collective bargaining process

and the statutory formula for retirees.

Develop Lower-Cost HMO Options

In structuring the state's health insurance plans, PERS, unlike some states such as

Missouri and Oregon, has required that contracting HMOs offer a

standardized package of services that are covered with specified copays.

Thus, the HMOs compete with one another only on price and quality of service provided, not on

the types of services offered.

As a result, unlike other forms of insurance such as auto or homeowners' coverage,

enrollees do not have any option within the HMO choices to decide how much insurance

they want. For example, enrollees cannot choose a plan that reduces their monthly premiums

by having fewer covered services, a $100 or $250 per-admission copay for hospitalization

or surgery, or a higher copay for doctor visits.

To offer more consumer choice and potential premium savings for enrollees and the

state, the Legislature could examine the feasibility

of offering an alternative, lower-cost health

insurance option to state employees and retirees. Such an option, for example, could require

each contracting HMO to provide one lower-cost and one higher-cost plan to enrollees, instead

of just one standardized plan. (Although PERS required HMOs to submit proposals with

two plan designs for 2002, the differences

included only relatively minor changes in doctor visit

and prescription drug copays.) In fact, the

current two PPO plans are already structured in such

a manner. One plan offers lower monthly premiums than the other in exchange for greater

cost sharing for medical services. Specifically,

the lower-premium PPO generally requires enrollees to pay 20 percent of health care costs up

to a specified amount, whereas the higher-premium plan requires enrollees to pay just

10 percent of health care costs.

The lower-cost options would reduce enrollees' out-of-pocket premium costs to

the extent the plan's premium is above the maximum state contribution. In addition,

these options could reduce state contributions to

the extent that there are more plan options that

cost less than the maximum state contribution. However, developing lower-cost HMO

options would not address the lack of HMO coverage in rural areas.

Change the Way State Contributions Are Determined

There are also a number of ways that the Legislature could change how the state

contributions for health insurance premiums are derived, with the potential for reducing

state costs depending on how the changes are structured.

Adopt Formula for State Employees.

Prior to 1974, state law prescribed a specific

dollar amount (increased periodically) as the

state's share of employee health insurance

premiums. In 1974, the Legislature changed the

state's contribution for health insurance to

80 percent of the average premium for employees

and retirees and 60 percent for their

dependents. This formula was subsequently increased to 85/60 in 1975 and finally to 100/90 in 1978. However, in 1978, the Legislature also

allowed the state contribution for employees'

health insurance premiums to be determined through collective bargaining, which typically

concludes after the budget is completed. Unlike state

costs for retirees which is governed by the 100/90 formula, the state's cost for employees

is unknown when the budget is approved.

While total cost is a significant issue with

this program, the uncertainty of how much the

state will pay is another key issue. To eliminate

some uncertainty regarding the amount the state

has to pay for its employees, the Legislature

could again adopt a formula for calculating the

state contribution for employees. In fact, the

Legislature recently attempted to do this. In 2001,

the Governor vetoed AB 1554 (Hertzberg), which would have applied the 100/90 formula to

state employees. The PERS estimated that this

would have cost an additional $64 million in 2002,

or about 7 percent of current state

expenditures for employee health insurance.

The Legislature could consider a contribution formula for employees other than the

100/90 formula envisioned by AB 1554. A formula resulting in reduced state costs

would not be outside the norm for contributions by California businesses, the state itself in the

past (as noted above), or other states. In 2002,

PERS estimates that the state will pay an amount

equal to 85 percent of total health insurance

premiums for employees and their dependents.

According to a 2002 Kaiser Family Foundation

survey, businesses in the state pay the equivalent

of 90 percent of one-party premiums and

79 percent for family enrollment. In addition, a

2001 survey of state government health benefits reported that a majority of states cover less

than 75 percent of dependent premiums. Thus, California pays a similar portion of

employee and dependent premiums as businesses in

the state, but a higher portion of dependents' premiums than other states.

We also did a nationwide survey of states, of which 14 responded. Our survey shows that

of the responding states, most pay a greater portion of employee premiums but a

smaller portion of dependent premiums than

California does (see Figure 6). In addition, only five

negotiate state contributions through the

collective bargaining process. Specifically, a number

of states including Iowa, Maine, Oregon, and Texas pay 100 percent of employee

premiums and anywhere from zero to 80 percent

of dependent premiums. Others like Nebraska, Nevada, and Vermont pay the same

portion, ranging from 75 percent to 80 percent,

for employees and their dependents alike. New York pays 90 percent of employee

premiums and 75 percent of dependent premiums.

Drawing from these findings, if the state adopted an 85/75 formula for employees

and their dependents, we estimate that state

savings in 2003 would be about $16 million.

Alternatively, with a 100/50 formula, the state

would save approximately $70 million.

Adopting a statutory formula would not impact overall premium increases. Rather,

it would determine what portion of premiums would be paid by the state. In addition,

depending at what level a formula is fixed and what

the administration would have otherwise negotiated in collective bargaining, it would also not

necessarily reduce state premium costs. It would, however, eliminate some uncertainty

regarding how much the state will pay from year to year.

Change 100/90 Formula for Retirees.

Our survey shows that while 8 of the 14 states

listed in Figure 6 pay some contribution for

retirees' premiums, only four of them contribute

toward dependent premiums. In comparison,

California uses the 100/90 formula to calculate the

state portion of premiums for retirees and their dependents.

|

Figure 6

LAO Survey of State

Contributions for Health Insurance Premiums

|

|

|

Employees

|

|

Retirees

|

|

|

State

Pays Less Than California For . . .

|

|

|

Coverage

Provided For . . .

|

|

Respondent Statesa

|

Employee

|

Dependents

|

Collectively

Bargained

|

|

Retiree

|

Dependents

|

|

Iowa

|

|

ü

|

ü

|

|

|

|

|

Maine

|

|

ü

|

b

|

|

ü

|

|

|

Mississippi

|

|

ü

|

|

|

|

|

|

Missouri

|

ü

|

ü

|

|

|

ü

|

|

|

Nebraska

|

ü

|

ü

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nevada

|

ü

|

ü

|

|

|

ü

|

ü

|

|

New York

|

|

ü

|

ü

|

|

ü

|

ü

|

|

North Dakota

|

|

ü

|

|

|

ü

|

|

|

Oregon

|

|

ü

|

ü

|

|

|

|

|

Texas

|

|

ü

|

|

|

ü

|

ü

|

|

Utah

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Vermont

|

ü

|

ü

|

ü

|

|

ü

|

ü

|

|

Washington

|

|

|

|

|

c

|

|

|

Wyoming

|

|

ü

|

|

|

|

|

|

a

Respondents to LAO nationwide survey.

|

|

|

b

Maine's contribution for dependents is determined through

collective bargaining.

|

|

c

Washington pays a specified dollar amount for retirees

enrolled in Medicare.

|

As discussed previously, the state provides health insurance for its employees—both

active and retired—in order to attract and retain

them and to protect this labor investment. This is

to help achieve the goal of having a more efficiently run government. While the prospect

of having state-paid health insurance in

retirement may influence some to work for the state,

we find little analytical basis for the state to

contribute more for retirees' health insurance

premiums than for current employees' premiums. However, this is precisely the case, as shown

in Figure 7.

|

Figure 7

2003 State Contributions

for

Health Insurance Premiums

`

|

|

Enrollment

|

Employeesa

|

Retireesb

|

|

One-party

|

$226

|

$288

|

|

Two-party

|

449

|

537

|

|

Family

|

587

|

665

|

|

|

|

a

Determined by collective bargaining.

|

|

b

Determined by the 100/90 formula.

|

State expenditures for retirees' health insurance have jumped 33 percent since

2000 to an estimated $424 million in 2002 because

of both enrollment and premium growth. To control this expenditure growth in the future and

to create a more balanced relationship between state contributions for employee and

retiree premiums, the Legislature could change the

100/90 formula as discussed in more detail below.

However, it appears that the formula could only be changed prospectively—that is, for

state employees beginning service after the

formula changes. This is because court decisions

have often considered employer contributions for retirees' health benefits to be part of the

employment contract as guaranteed compensation. As a result, changing this contribution for

current employees and retirees is likely to be

determined by a court to be a contract violation.

The Legislature has prospectively changed this contribution in law twice before. From

1978 through 1984, the 100/90 formula applied to

all current and future retirees. Then the

Legislature changed state law for employees first hired

on or after January 1, 1985. These individuals

would not be eligible for the full amount of the

100/90 formula contribution in retirement until

they worked for the state for ten years (instead

of five years as under prior law). Another law change effective January 1, 1989, made

new employees starting after that date eligible for

just half of the 100/90 formula contribution in retirement after ten years of state service.

These individuals would then be eligible for an

additional 5 percent of the formula amount

with each additional year of state service, up to

the full amount after working for the state for 20 years.

The Legislature could similarly adopt another contribution schedule for retirees to

apply to new state employees hired after some

future date. Alternatively, the Legislature could set

the state's monthly contribution for retirees'

health insurance premiums at the same dollar

amount as that negotiated for employees through collective bargaining. Any savings would

be prospective though, once those new employees retire. Thus, there would be no

near-term savings from changing the contribution

for retirees now.

Strengthen Incentive to Choose Lower-Cost Plans.

The Legislature could also consider significantly strengthening the incentive for

both employees and retirees to select lower-cost

plans. One way to achieve this is by setting the

state's contribution at some portion of (or equal to)

the monthly premium of the lowest-cost plan

available in each county. (The state contribution

may vary depending on what plans serve each county.) While PERS requires health plans

to meet certain standards to be approved for the state program, the premiums vary from one

plan to another. The Legislature could send a

strong, clear signal encouraging employees and

retirees to choose lower-cost health plans by tying

the state contribution to the lowest-cost plan

available. If individuals believe that other

options provide better care or otherwise better

meet their needs, then they could pay the

difference in premium for a more expensive health plan.

We recognize that this option could cause the state contribution for health insurance

to vary by county to the extent that the

lowest-cost health plan is not offered statewide. For

example, because it lacks HMO service, the state contribution for employees and retirees

in Trinity County would be tied to the premium of the lower-cost PPO plan available there. On

the other hand, the state contribution in Ventura County would be tied to the lowest-cost

HMO plan available there, which has a smaller premium than the PPO plans. Thus, the

state contribution in Trinity County would exceed that in Ventura County if such an option

were currently in effect.

Such variation in compensation is not without precedent. For example, the

state currently offers pay differentials for

hard-to-fill positions based on criteria such as

location. Varying the state health insurance

contribution based on available health insurance

choices would similarly reflect local economic and employment conditions.

If implemented, this option should be coordinated with the existing Rural Health

Care Equity program. This would avoid compensating eligible employees for the HMO-PPO

premium differential already addressed by the higher

state contribution for rural areas that would be adopted under this option.

Other Options

There are other options the Legislature may wish to consider or have PERS investigate.

For example, the state could consider

consolidating prescription drug purchasing for all state

departments. Currently, PERS contracts for

prescription coverage for state employees and

retirees, while the Department of General Services contracts on behalf of other departments

such as Corrections, Mental Health, and Developmental Services for their prescription

drug needs. In addition, and at a more macro

level, the Legislature may wish to study the

feasibility of consolidating the state's separate

purchases of health insurance coverage for programs

such as PERS, Medi-Cal, and Healthy Families.

These options may help maximize the state's

negotiating leverage as a large purchaser of

health coverage, thereby enabling the state to

achieve better prices and lower costs.

Conclusion

The PERS is taking a number of steps to help control the sharply rising cost of the state

health insurance program for employees and

retirees. We recommend ongoing legislative oversight

of this program. Specifically, we recommend:

- An annual report from PERS in budget hearings on (1) the

total costs to provide health insurance for state

employees and retirees, (2) health care cost trends and forecasts

generally, and (3) PERS actions to address growing program

costs and other identified issues.

- A consolidated informational display of total health insurance costs for

state employees in the annual Governor's budget.

We have also highlighted two major options for the Legislature to consider to further

limit state and enrollee costs for the program:

- Develop lower-cost HMO options.

- Change the way state contributions are determined.

| Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by ,Todd

Clark, under the supervision of C.

Dana

Curry. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office

which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the

Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656.

This report and others, as well as an E-mail

subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at

www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000,

Sacramento, CA 95814. |

Return to LAO Home Page