May 21, 2002

The Rural Crime Prevention program supports local law enforcement activities targeted at agricultural crime. A lack of data on agricultural crime before implementation of the program prevents us from determining the program's effectiveness in reducing agricultural crime. However, we were able to determine that the program's rates of arrests, prosecutions, and convictions were higher than the statewide average and efforts to recover lost equipment have been successful. We make recommendations to more effectively target the program and improve data collection should the Legislature decide to reauthorize the program.

Chapter 327, Statutes of 1996 (AB 2768, Poochigian), established the Rural Crime Prevention program to test the effectiveness of crime prevention strategies in reducing rural crimes, that is, agricultural property crimes. The program currently provides grant funding to eight rural counties to support law enforcement activities targeted at such crimes.

Chapter 310, Statutes of 2000 (AB 1727, Reyes), required the Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) to report to the Legislature on the outcomes of the Rural Crime Prevention program. Pursuant to Chapter 310, this report presents our findings. In this report, we provide background information on the program, describe the crime prevention strategies used by the participating rural counties, and discuss our findings with regard to the effectiveness of the program in preventing rural crime.

Our findings are primarily based upon (1) data provided by the counties, (2) consultation with the Office of Criminal Justice Planning, (3) discussions with law enforcement personnel implementing the program, and (4) site visits and attendance at regional Rural Crime task force meetings.

Legislative History. The Rural Crime Prevention program was originally established as a pilot program in Tulare County. The enabling legislation—Chapter 327, directed the county to establish a multiagency task force to develop and implement strategies aimed at preventing agricultural crime. The task force included representatives from the Sheriff's Department, the District Attorney's Office, and the County Agricultural Commissioner's Office.

The pilot program that evolved from the efforts of the task force had several components, including community outreach and education, targeted law enforcement strategies geared towards addressing the unique aspects of agricultural crime, specialized prosecution efforts, and loss recovery efforts. These components are discussed in greater detail later in this report.

Based on the report of the Tulare County pilot project, and continued concerns of significant economic losses to the state's agricultural industry resulting from agricultural crime, the Legislature enacted Chapter 564, Statutes of 1999 (AB 157, Reyes), which expanded the Rural Crime Prevention program to seven additional counties—Fresno, Kern, Kings, Madera, Merced, San Joaquin, and Stanislaus. The new counties were to implement crime prevention strategies modeled on those developed in the pilot project, and to track statistics on crime prevention, crime suppression, prosecutions, and loss reductions. This program is scheduled to sunset on July 1, 2002.

What Is Rural Crime? Under the Rural Crime Prevention program, rural crimes are property crimes against the agricultural industry. Thefts of crops, livestock, farm equipment, farm chemicals, and farm property are classified as rural crimes. If a farmer's house is burglarized, and a computer is stolen that the farmer's children use to prepare their homework, then the law enforcement officer would classify this crime as a regular burglary. If the primary purpose of the stolen computer is to track the dairy cows' daily milk output, then the offense would be classified as a rural crime. In Kern County, where oil is a major rural industry, this definition of rural crimes also includes thefts of crude oil and crude oil industry equipment.

Administration. At the local level, the Rural Crime Prevention program is administered by multiple agencies, including the Sheriff's Department, the District Attorney's Office, and the County Agricultural Commissioner in each of the participating counties. The efforts of the individual local agencies are guided by a regional task force, which includes representatives from each of the participating agencies. The task force representatives from each county meet regularly to discuss the operation of the program.

The Office of Criminal Justice Planning (OCJP) is responsible for state oversight of the program. The role of OCJP primarily involves administering grants, and providing technical assistance to the eight counties in submitting forms for reimbursements and in organizing the monthly task force meetings.

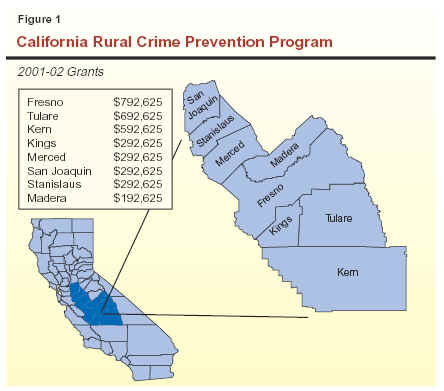

Funding. The Rural Crime Prevention program is supported by the General Fund. There is no required county contribution. The amount each county receives annually is set in statute as shown in Figure 1. The Governor's budget originally included $3.4 million for 2002-03, the same level of funding as provided in the current year. However, this amount was reduced to $1.7 million in the May revise due to the state's fiscal condition. In the current year, grants range from $193,000 (Madera) to $793,000 (Fresno). Since its inception, the program has received a total of approximately $15 million from the state, through the current year.

Reported Program Expenditures. Based upon data we collected from the participating counties, Figure 2 provides a breakdown of county expenditures by type for fiscal year 2000-01 (the latest year for which complete data are available). As the figure shows, the counties spent the largest percentage of funds (82 percent) on salaries and benefits, followed by equipment (10 percent), and administrative overhead (8 percent). These expenditures are discussed in greater detail below.

|

Figure 2 Rural Crime Program

Expenditures |

||||

|

County |

Salaries

and Benefits |

Equipment |

Administrative

Overhead |

Totala |

|

Fresno |

$741,800 |

— |

$50,800 |

$792,600 |

|

Kern |

534,200 |

$36,400 |

22,000 |

592,600 |

|

Kings |

234,500 |

14,100 |

44,000 |

292,600 |

|

Madera |

180,500 |

— |

12,200 |

192,600 |

|

Merced |

211,500 |

54,800 |

26,400 |

292,600 |

|

San Joaquin |

190,400 |

70,700 |

31,500 |

292,600 |

|

Stanislaus |

136,900 |

124,900 |

30,800 |

292,600 |

|

Tulare |

599,900 |

37,000 |

55,700 |

692,600 |

|

Totalsa |

$2,829,600 |

$337,900 |

$273,400 |

$3,441,000 |

|

Percent |

82.2% |

9.8% |

7.9% |

100% |

|

|

||||

|

a

Numbers may not add due to rounding. |

||||

Based upon our discussions with task force members and program administrators, we found that the participating counties used the Rural Crime Prevention grants to support a range of similar crime prevention activities that generally fall into four broad categories: (1) community outreach, (2) enhanced law enforcement, (3) specialized prosecution, and (4) loss recovery efforts. These strategies are described in greater detail as follows.

Community Outreach. The counties adopted prevention education activities developed by the Tulare Pilot Project. In addition to public presentations, the counties offered printed publications, a fax network, and a Web site to create community awareness of rural crimes. These materials were geared towards educating community members about rural crimes and teaching them methods of reducing the risks of victimization. One such method is to mark farm equipment with a unique identification number, as discussed in greater detail below. The participating counties also implemented a fax network and an Internet Web site to expand their ability to reach a wider audience.

Targeted Enforcement. The participating counties used a variety of targeted enforcement activities. In areas identified as "high risk," surveillance, stakeouts, and covert operations allowed the Sheriff's deputies in specialized rural crime prevention units to assist owners in protecting crops ready to harvest, livestock, and other property.

For example, detectives in Tulare and Kern mounted nylon trip wires connected to sensitive sound detectors to serve as burglar alarms in citrus and grape orchards. In another example, the Sheriff's unit in Merced cooperated with a rancher to safeguard his cattle by moving them to an area that the officers had earlier identified as useful for surveillance. In several stakeout operations the Sheriff's unit in Merced, Madera, and San Joaquin surrounded high-risk fields and orchards, and watched while suspects arrived to pick fruit during the night. When suspects left the fields, they were arrested with the stolen crops still in their possession. Remote radio frequency alarm systems were used in several counties including Tulare, Kern, and Stanislaus to detect burglaries in progress and respond to them. Also, the rural crime prevention officers in Tulare developed covert or "sting" operations using decoys to catch thieves in the act of taking farm chemicals.

Specialized Prosecution. The District Attorneys in the participating counties used a specialized prosecution strategy known as vertical prosecution that studies have shown maximizes the likelihood of conviction. Vertical prosecution is different from the usual prosecution process in that one attorney is assigned to handle each case of agricultural crime through all stages of the prosecution process. The premise behind this approach is that the assigned attorney gains greater expertise on each particular case, and acquires greater knowledge of rural crimes in particular, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful convictions.

Loss Recovery Efforts. The counties used various loss reduction efforts to recover stolen items and return them to their rightful owners. One such effort is the Owner Applied Number (OAN) program, a nationwide equipment identification system that allows law enforcement to find owners of recovered stolen property. Established by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the federally funded program is run regionally by Tulare County for the eight participating counties. A unique identification number was assigned and stamped on each piece of equipment registered with the OAN program. More than 5,000 farmers and ranchers have registered various pieces of their farm equipment with the OAN project. The rural crime prevention officers stated that the OAN registry system was most valuable for marking tractors and other large equipment. However, the concept of marking equipment was also applied to other types of equipment. For example, the Kern County Rural Crimes Investigative Unit marked irrigation pipe and baling wire when there were numerous thefts of such equipment.

Chapter 310 required each county to prepare and submit to the Legislative Analyst a cost-benefit analysis of their programs. Based upon our review of the initial information provided by the counties, we concluded that the data had limited usefulness for purposes of evaluating the effectiveness of the program. This is primarily because baseline information was not available. In other words, there were no data collected on the numbers of agricultural crimes, arrests, convictions, and property recovered for the period before the existence of the program with which to compare data collected after the program's implementation.

Additionally, we identified a number of other concerns related to data collection. There was no standardized recording form or procedure used by all eight counties when collecting data. Moreover, each District Attorney and Sheriff's Department unit at the local level kept its own records, in most cases using different identification numbers for record keeping, thereby making it difficult to match prosecutions with arrest records. We found that the counties in the Rural Crime Prevention program had invested less than 1 percent of their resources in staff to conduct the required data entry, record keeping, and reporting functions. We believe that in order to conduct the kind of analysis required by statute, the counties would have had to commit more resources or have had greater technical assistance in planning this data collection effort at the outset of the program.

We note that counties were cooperative in providing supplemental data which we requested. Specifically, counties were asked to provide a record of program activities for the calendar year 2000, including the number of cases reported, investigated, prosecuted, and convicted. Measures of loss recovery included the estimated value of stolen property and the estimated value of items recovered. Qualitative information was gathered during on-site visits, task force meetings, and in discussions with rural crime prevention officers and attorneys.

Ideally, the effectiveness of the rural crime program would be evaluated on the basis of its impact in reducing agricultural crimes. However, as indicated earlier, data do not exist on the extent of these crimes prior to the implementation of the Rural Crime program. Given this data limitation, we evaluated the effectiveness of the program on two other dimensions: (1) the effect on the reporting of property crimes and (2) the effect on law enforcement outcomes. We based our analysis on data collected annually by the California Department of Justice (DOJ) as well as data provided by the Rural Crime counties.

Effect on Reporting of Property Crimes. We examined overall property crime rates in the rural crime program counties to evaluate the impact of the program on reported property crimes. We analyzed these rates for each county before and after the program's implementation, as well as compared the trend in each county to the statewide property crime trend.

We took this approach because it is a well recognized phenomenon in criminal justice research that increased law enforcement emphasis on a particular crime is frequently accompanied by an increase in the reporting of such crimes due to heightened public awareness. Accordingly, one might expect that an increase in the reporting of overall property crimes in the Rural Crime counties could be explained by an increase in the reporting of agricultural crimes during the period of the program's existence. We would note, however, that because rural crimes are a subset of property crimes, the impact of the Rural Crime program on reported crimes could be masked to the extent that residents of the participating counties were reporting agricultural crimes at a relatively high rate before the implementation of the program.

Using this approach, the data did not suggest an impact of the program on the number of reported agricultural crimes in seven of the eight counties (Tulare being the one exception). For the most part, total reported property crimes in each of these seven counties appeared to be roughly the same before and after the program's implementation, and generally followed the same trend as the state overall. The lack of effect may be explained by the fact that the program had been in operation in these seven counties for only one year.

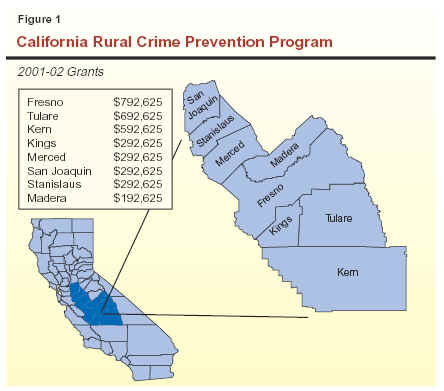

However, we did observe a significant increase in the number of total reported property crimes in Tulare County, and a significant departure from the overall state trend, suggesting that the Rural Crime program in that county may have been successful in increasing the number of reported rural crimes. While the analysis is inconclusive, we believe there is evidence to suggest the Tulare County program potentially had an impact on reported property crimes.

Effect on Law Enforcement Outcomes. We used the agricultural crime data reported to us by the participating counties to calculate arrest, prosecution, and conviction rates, and then compared these rates to the state average rates for similar activities. This comparison is limited since "agricultural crime" data are not collected statewide, but rather only in the participating counties. Thus, we compared the rural county reported agricultural crime data for arrests, prosecutions, and convictions to statewide data for property crime felonies, as reported by DOJ.

We found that all eight counties had better outcomes than the state as a whole, suggesting that the Rural Crime Prevention program has led to greater success in the area of arrests, prosecutions, and convictions.

If the Rural Crime program in the eight counties were having a significant impact on the reporting of agricultural crime, we would expect the number of reported property crimes to increase and to be a departure from their earlier trends and from trends statewide. This is because crime prevention activities, such as education and outreach, often result in an increase in the number of reported crimes.

For the eight counties participating in the Rural Crime Prevention program, we examined the number of total property crimes reported before and after the establishment of the program in order to evaluate whether the existence of the program resulted in any noticeable change in the number of reported crimes. We also compared the property crime rates in each of these counties to the state as a whole to examine whether any of the counties experienced a property crime trend that diverged from the statewide trend.

No Significant Change in Property Crime Reports in Seven of Eight Counties. For seven of the eight counties—all except Tulare—we found that there was not a significant change in the level of reported property crimes in those counties before and after the program was established.

In comparing the eight counties to the state as a whole, we found that these counties had higher property crime rates than the state as a whole. However, with the exception of Tulare, the property crime trend, before and after the program was established, remained consistent with the statewide trend.

Reported Property Crimes Increased Significantly in Tulare County, While State Reports Declined. In Tulare County, we observed a dramatic change in the level of reported property crime after the program was established. Property crime rates in Tulare were lower than the California average in 1995 before the Rural Crime Prevention program began. After 1996, when the program was established, the crime rates increased rather abruptly and never again declined below the California average, as shown in Figure 3. Specifically, the property crime rates in Tulare increased in 1997 and 1998, at a time when the overall state property crime rate was dropping, including the seven other rural crime counties.

In summary, based upon our examination of property crime rates, we cannot draw any definitive conclusions about the impact of the Rural Crime Prevention program on the reporting of agricultural crimes in seven of the eight counties. This may be because there is only one year of data for the seven counties (2000)—the same year they were implementing the program. However, the data suggest that education and outreach activities in the Tulare County program may have had an impact on increased property crime reports.

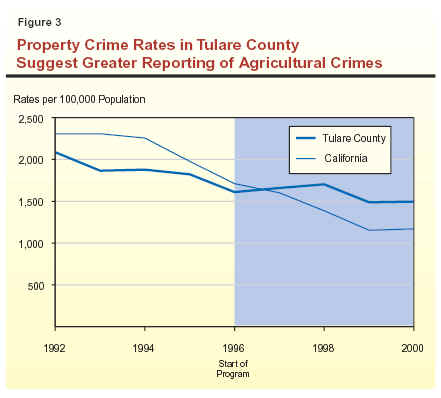

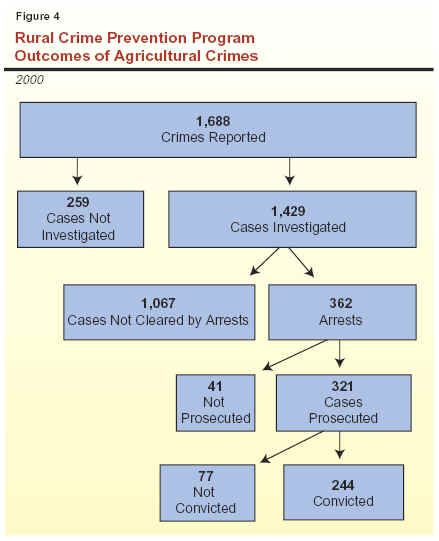

Overview of Enforcement Outcomes. As indicated earlier, we asked the participating counties to provide data on the number of agricultural crimes reported, investigated, prosecuted, and convicted in calendar year 2000. This information is summarized in Figure 4.

Our analysis calculated the rates for each of the outcomes reported by the participating counties as measures of the success of the program, then compared these outcomes to similar outcomes reported by the DOJ for the state as shown in Figure 5. Specifically, we compared the arrest rate for agricultural crime to the statewide arrest rate for burglary and motor vehicle theft. We compared the county data on agricultural crime prosecutions and convictions to DOJ data on all felony prosecutions and convictions. We recognize that this is not a perfect comparison. However, in view of the lack of data on agricultural crimes on a statewide basis, we believe that the DOJ statewide data provide a reasonable yardstick by which to measure the effectiveness of the law enforcement components of the program.

|

Figure 5 Rural Crime Prevention

Program Outcomes |

|||

|

Outcomes |

Rural

Crime |

Property

Crimes Statewidea |

Percent |

|

Investigation rate |

85% |

—b |

—b |

|

Arrest rate |

25 |

10%c-14%d |

11%-15% |

|

Prosecution rate |

89 |

84e |

5 |

|

Conviction rate |

76 |

71e |

5 |

|

|

|||

|

a

Based

on California Department of Justice data reports. |

|||

|

b

Data

not available. |

|||

|

c

Motor vehicle thefts, as reported to DOJ for 1999. |

|||

|

d

Burglaries, as reported to DOJ for 1999. |

|||

|

e

All felonies. |

|||

Investigation Rate. A successful investigation is one in which enough evidence is gathered that at least one suspect is identified or enough evidence is gathered to proceed to an arrest. While the arrest or "clearance" rate is often used as the measure of success, an arrest cannot be made without adequate evidence obtained through an investigation. We note also that a productive investigation may result in a single arrest that solves several crimes because the perpetrator was guilty of other crimes as well. Conversely, a single crime that is thoroughly investigated can well result in several arrests. For these reasons, an investigation rate is one important measure of the success of a program and its activities. As shown in Figure 5, the numbers of agricultural crimes reported by the eight counties as having been investigated is relatively high at 85 percent with only 15 percent of those reports not being investigated. Unfortunately, statewide data on investigation rates are not available for comparison.

Arrest Rates. The arrest rate is another important indication of how well a program is being conducted. According to statistics gathered by DOJ about 26 percent of all crimes in California were solved by an arrest. Property crimes result in an arrest less often than violent crimes. The Rural Crime Prevention program had higher numbers of reported cases solved by an arrest than the average arrest rate for our selected comparison of property crimes in California. For example, an arrest occurred for 14 percent of the burglaries and 10 percent of the motor vehicle thefts in the state. In comparison, the number of arrests per investigation for the Rural Crime Prevention program is 25 percent or nearly one in four.

Prosecution Rates Higher than the Rate for Felonies Statewide. The vertical prosecution method used for rural crime prevention produced 321 prosecutions (felonies and misdemeanors) out of 362 arrests, or a prosecution rate of 89 percent. In a report issued in 2000, the DOJ found that 84 percent of all felonies in California had been prosecuted. Thus, the Rural Crime Prevention program had a prosecution rate that was five percentage points higher than the rate for felonies in California. The prosecution rate for the Rural Crime program is impressive when one considers that it includes misdemeanors that typically are prosecuted at a lower rate than felonies. This suggests a more active level of prosecution in the Rural Crime program than generally is the case statewide.

Conviction Rates Higher Than Felony Conviction Rates Statewide. Conviction rates were higher for the Rural Crime Prevention program than the overall felony conviction rates in California. Conviction rates for this program were 76 percent of all cases prosecuted. These numbers may be somewhat underestimated because of an unknown number of cases that were still pending trial at the time the data were compiled. As reported by DOJ, the conviction rate for all felonies prosecuted in California was 71 percent.

Counties Report Efforts to Recover Stolen Property Were Relatively Successful. As discussed earlier, counties implemented a number of strategies, including marking equipment with an OAN, to improve their ability to recover stolen objects. Based upon the data submitted by the participating counties, we found the Rural Crime Prevention program recovered approximately $3.9 million, or 48 percent, of a total estimated loss of $8.1 million in 2000 as Figure 6 shows. Our discussions with law enforcement suggest that recovery of the farm equipment items is due in part to the success of the OAN program in marking larger equipment, especially tractors. Larger equipment is more easily marked, and tractors account for a large proportion of both losses and recoveries. Thefts of heavy equipment, mainly tractors, accounted for the largest share of losses. This is mainly because these are the most expensive items on a farm or ranch. Stolen crops included items such as walnuts, hay, citrus, almonds, and grapes, representing the smallest share of reported losses.

|

Figure 6 Rural Crime Counties |

|||

|

Type of Loss |

Estimated

Losses |

Amounts |

Percent

of |

|

Equipment taken |

$2,943,525 |

$1,881,310 |

63% |

|

Property losses |

2,121,943 |

783,878 |

36 |

|

Stolen farm chemicals |

1,385,810 |

587,909 |

42 |

|

Stolen livestock |

838,525 |

352,746 |

42 |

|

Crop losses |

815,964 |

313,552 |

38 |

|

Totals |

$8,105,767 |

$3,919,394 |

48% |

Qualitative Evidence of Improved Information Sharing. The Rural Crime Prevention program participants we interviewed stated that regular meetings of the task force led to an exchange of information that resulted in improved investigations of cross-jurisdictional crimes and other types of crimes. As one sheriff's deputy described it, before the implementation of the program, an offender was able to get away with crime just by crossing the county line. Rural Crime detectives also discovered that solving rural property crimes lead to solving other crimes in the area such as drug offenses. For example, some offenders were stealing certain farm chemicals to manufacture methamphetamines and other illegal drugs.

The Rural Crime Prevention program has a history of mixed results with some signs of success. On the one hand, there is inconclusive evidence regarding the effectiveness of the program's outreach and education efforts in increasing the reporting of agricultural property crimes. On the other hand, the program's rates of arrests, prosecutions, and convictions were higher than the statewide average, although the data are limited to one year. In addition, efforts to recover lost equipment have been successful in recovering nearly half of each dollar reported lost.

With this performance as a backdrop, the Legislature will very shortly be faced with the issue of whether or not to reauthorize the program since it sunsets July 1, 2002. We note, however, that the Governor's January budget provides funding for the program through 2002-03.

Below we offer criteria for the Legislature to use when considering this program's reauthorization.

Criteria for State Funding of Local Law Enforcement Activities. In California, law enforcement is primarily a local responsibility. Generally, local governments carry out and fund activities that enforce the laws, particularly investigating, arresting, and prosecuting crime. There have been exceptions, however, when the state has provided funds, as it has in the Rural Crime program, to augment local public safety efforts.

In those instances where the state decides to augment local public safety expenditures, we believe that it should do so only for those programs that have the following attributes:

How Does the Rural Crime Program Stack Up? Based on our review, we conclude that the Rural Crime program clearly meets a couple of these criteria, while the program's performance on a couple of the other criteria needs improvement. As regards the first criterion, we believe that the Rural Crime program is generally targeted to a specific statewide objective which is the reduction of agricultural crime. Although the program supports a limited number of counties, the eight counties that receive funds constitute a major agriculture producing region in California. As regards the sharing of information criterion, this is done through meetings of the regional taskforce. It is at such meetings that information on particular cases is shared, as well as information about best practices. As regards the evaluation of programs (particularly the availability of data to evaluate the program) and the allocation of funds, we would recommend that improvements be made in the event that the Legislature decides to reauthorize the program. These suggested improvements are discussed as follows.

One of the objectives of the enabling legislation for the Rural Crime program is to improve the collection and availability of data on agricultural crime in California. However, we found that the participating counties lack a uniform procedure for collecting data on agricultural crimes. For example, counties do not use similar forms for collecting their agricultural crime data. This results in varying levels of consistency among the data collected by the counties. We also found that the data are collected separately in each county with no central database for storing this data. We believe that these problems are the result of a lack of technical assistance to the counties, and to a lesser extent, the relatively low level of staff resources that counties committed to data collection efforts.

We recommend that the regional task force be required to develop a uniform procedure for all participating counties to use in collecting data, and that counties be required to collect and maintain data as a condition of participation in the program. We also recommend the establishment of a central database, to be maintained by one of the participating counties, for the collection and maintenance of data on agricultural crimes. The Legislature may also wish to require the regional task force to submit an annual report on the performance of the program.

The enabling legislation for the Rural Crime program specifies that the purpose of the program is to strengthen the ability of law enforcement agencies to "detect and monitor agricultural- and rural-based crimes." However, the current program is limited to eight counties which are specified in statute. Although the counties in this region are responsible for about half of the agricultural production in the state, there are several counties with agricultural production that are not included in the program. If the Legislature decides to reauthorize the program, it should determine whether to limit the program to the current eight counties or to make it available to other counties with agricultural production. The answer to this issue is basically a policy call for the Legislature.

In addition to the question of which counties should participate in the program, there is also the issue of how funds should be allocated among participating counties. The current allocation of funds is specified in statute. Although it is not precisely clear how the statutory allocation was derived, it is our understanding that it is based on agricultural production. While this is an important element, we recommend that the Legislature add an additional "crime rate" factor. Ideally, one would want this to be an agricultural property crime rate. While this is desirable in the long run, it is probably not practical in the short term due to the data limitations discussed previously. In the short term, an overall property crime rate could be used instead, in combination with agricultural production when allocating funds among counties.

Reducing the economic losses due to rural crimes poses a significant challenge to policymakers and to state and local criminal justice officials. The Rural Crime Prevention program has had mixed results. Should the Legislature decide to reauthorize the program, we recommend steps to more effectively target it, and to improve data collection.

| Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by , Stephanie Amedeo Marquez under the supervision of Gregory Jolivette. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |