May 24, 2004

The administration's local government proposal would make far-reaching changes to state-local finance. Our review of the proposal indicates that it would greatly increase the stability of local finance and increase accountability in the mandate process. We also find, however, that the proposal locks in place the current flawed state-local fiscal structure, imposes added fiscal stress on many local governments, and is not structured in a fashion that addresses long-term state fiscal goals. For the Legislature's consideration, we provide various recommendations to bring the proposal into greater alignment with legislative goals and state fiscal objectives.

In its May Revision, the administration proposes that the Legislature place before the statewide voters in November a constitutional amendment to enact far-reaching changes to state-local finance and intergovernmental relations. Over time, the proposed constitutional provisions would significantly influence state decision-making regarding cities, counties, special districts, and redevelopment agencies. (With the exception of provisions relating to a proposed tax swap, K-14 districts are largely unaffected by the measure.)

In general, the measure greatly restricts state authority to reduce noneducation local government taxes, except for a $1.3 billion shift from these agencies in 2004-05 and 2005-06. The measure also includes a complex swap of vehicle license fee (VLF) "backfill" revenues for K-14 property taxes and places into the State Constitution: (1) the current VLF rate of 0.65 percent, (2) certain existing statutory provisions relating to local finance, and (3) reforms to the mandate reimbursement process. Figure 1 summarizes the major provisions of the local government proposal.

|

Figure 1 Major Provisions of the Administration�s Local

Government Initiative |

|

|

Policy

Area |

Provisions |

|

Protection of Major Local

Government Revenues |

|

|

State Fiscal Relief |

|

|

VLF Backfill for Property Tax

Swap |

|

|

Mandates |

|

While the administration is still developing the constitutional language (and related statutory changes), the Legislature will need to begin its review shortly given the measure's link to the 2004-05 state budget and the upcoming deadlines for placing a measure on the November ballot. Accordingly, to assist the Legislature, we provide a summary and initial assessment of the proposal as described in materials provided by the administration and preliminary language provided on May 21, 2004. (We note that some minor elements of the proposal have changed since our summary of the proposal in the Overview of the 2004-05 May Revision.) As additional information and specific language for the measure becomes available, we will provide the Legislature with additional analyses.

Under the administration's proposal, noneducation local governments would contribute $1.3 billion in 2004-05 and 2005-06 to their respective county Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund (ERAF) accounts. County auditors would allocate these property tax revenues to K-14 districts, which in turn would offset a comparable amount of state education spending. (Please see the appendix for some background information on ERAF and other local government financial terms used in this report.)

Figure 2 provides information regarding the proposed allocation of the $1.3 billion across cities, counties, special districts, and redevelopment agencies. The administration indicates that these methodologies were developed in conjunction with the following local government statewide associations: League of California Cities, California State Association of Counties, California Special Districts' Association, and California Redevelopment Association.

|

Figure 2 Allocation of $1.3 Billion Revenue Shift |

|

|

Agencies�Amount |

Allocation

|

|

Cities� |

|

|

Counties� |

|

|

Independent Special Districts� |

|

|

Redevelopment Agencies� |

|

Under current law and the California Constitution, the state has significant authority over the rate and/or allocation of most major local taxes, including the property tax, the 1 percent local "Bradley-Burns" sales tax, optional local sales taxes, and the VLF. The administration's proposal would greatly limit state authority over local finance by preventing the Legislature from enacting laws that reduced, delayed, or reallocated any noneducation local government's share of revenues from the VLF, sales tax, or property tax. The measure also would preclude the Legislature from enacting a law to increase the VLF rate over its current 0.65 percent rate.

Finally, the administration also proposes to place into the Constitution certain existing financial provisions or requirements relating to local finance. These include requirements that the state (1) pay $1.2 billion in 2006-07 for the VLF "gap loan" (as discussed in the appendix), (2) guarantee replacement property taxes during the period that part of the local sales tax is used to pay Proposition 57's fiscal recovery bonds (as discussed in the appendix regarding the "triple flip"), (3) reestablish local government's full authority to impose a 1 percent Bradley-Burns sales tax rate when the fiscal recovery period ends, and (4) pay the backlog of noneducation mandate claims in five installments, beginning in 2006-07 (approximately $1.6 billion).

The May Revision proposes major changes regarding city and county VLF revenues and

K-14 district property taxes by:

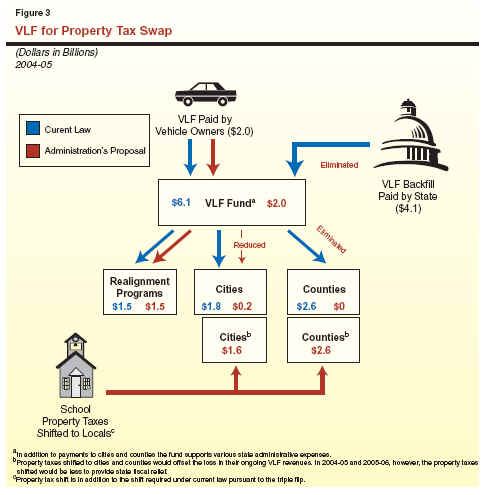

Figure 3 summarizes the tax swap. As shown in the figure, VLF backfill payments would be eliminated, thereby reducing VLF fund revenues by two-thirds. County health and social services realignment programs would receive the same dollar amount of VLF revenues as under existing law, but general-purpose VLF revenues to cities and counties would change significantly. Counties would no longer receive general-purpose VLF revenues. Cities would receive the remaining nonrealignment VLF revenues, net of the state's administrative costs, or about $227 million.

To offset these city and county VLF reductions, county auditors would reallocate property taxes from schools and community colleges to cities and counties, with K-14 district property tax losses offset through increased state education apportionments. (These property tax allocations from K-14 districts to cities and counties would be in addition to the property tax allocation required under existing law to replace reduced city and county sales taxes under the triple flip.)

"Hold Harmless" Provisions. Any shift of this magnitude affects local governments differently due to unique conditions and factors in various communities. Seeking to maintain the current level of resources for all local governments and K-14 districts, the administration proposes a wide variety of hold harmless provisions, including provisions to exempt from the tax swap "basic aid" K-14 districts (those districts that receive unusually high amounts of property taxes).

The Constitution currently requires the state to reimburse local agencies (including K-14 districts) if the state mandates a new program or higher level of service. Under current law, local agencies file "test claims" with the Commission on State Mandates. If the commission finds a mandate, it adopts a mandate reimbursement methodology, and reports the mandate's estimated statewide cost to the Legislature.

Because of the complexity of this process, it takes several years for the commission to process a claim. In addition, although the Constitution requires the state to reimburse local agencies for mandates, the state does not incur any significant consequences if it defers reimbursements to a later date. Existing law also permits the state to avoid incurring a mandate liability in any year in which the Legislature suspends a mandate requirement in the budget act.

Administration's Proposal. The administration proposes an array of changes that would be applicable only to noneducation mandates. First, the commission would have four months to determine whether a noneducation test claim constitutes a mandate. If the commission found a mandate, the Department of Finance (DOF) would determine the reimbursement methodology and propose the amount needed to reimburse local governments. If funding at the amount the DOF determines is not provided in the next state budget or subsequent state budgets, the mandate would terminate in 90 days, unless the mandate related to employee rights or benefits. The measure also would preclude the Governor from vetoing a mandate appropriation. Finally, the administration proposes to widen the definition of a mandate to include, among other items, situations when the state transfers partial funding responsibility for a joint state-county program. This would limit state authority to alter existing cost sharing agreements, such as for mental health or in-home supportive services programs.

Other Local Initiative on Ballot. Earlier this year, a coalition of statewide local government associations submitted signatures to the Secretary of State to qualify "The Local Taxpayers and Public Safety Protection Act" (LTPSPA) for the November 2004 ballot. Although the LTPSPA is similar to the administration's proposal in many respects, the LTPSPA would rescind any state budget action taken this year that reduced noneducation local agency's property taxes. The administration's proposal, in contrast, permits the state to redirect $2.6 billion of local government property tax revenues over the coming two years. The administration's measure also (1) places greater restrictions on state authority over local finance than does the LTPSPA and (2) takes a different approach to reforming the mandate process. As part of the agreement between the administration and the statewide local government associations, we understand that the associations have agreed to support the administration's proposal instead of the LTPSPA if both measures appear on the November ballot. If the administration's proposal does not appear on the November ballot, the local government associations have indicated that they will support the LTPSPA.

Future State-Local Realignment. As part of its proposal, the administration indicated its intent to propose additional state-local program realignment in 2006-07. As we discussed in the 2003-04 Perspectives and Issues (please see page 123), given the size and diversity of California, we think realignment of some state programs could improve program outcomes. We note, however, that the administration's proposal to widen the mandate definition would constrain the Legislature's flexibility in realigning the fiscal obligations for jointly financed programs.

Our review of the preliminary materials provided by the administration indicates that the proposed constitutional provisions would increase the stability of local finance and increase accountability in the mandate process. The proposal also contains elements, however, that appear contrary to the Legislature's long-term policy objectives, lack obvious policy rationales, or are not consistent with state and local fiscal interests. We summarize our concerns in Figure 4 and discuss these matters below.

|

Figure 4 Major Concerns Regarding Administration�s |

|

|

|

�

Existing local finance system locked in place. |

|

�

Rationale for complex tax swap not clear. |

|

�

Major local fiscal effect for short-term state relief. |

|

�

Mandate proposal shows promise, needs work. |

The May Revision proposal highlights tensions between two longstanding interests relating to local finance: (1) local government fiscal protection and (2) local finance reform.

Protecting Local Government Revenues. In contrast to most other states, California law gives state government, rather than local governments or their residents, significant authority over major local revenues. Specifically, the California Legislature may enact laws to change the rate and/or allocation of the VLF, local sales tax, and property tax. Over the years, the state has used this authority to address policy concerns, such as changing (1) the share of property taxes allocated to schools after the passage of Proposition 13 in order to increase resources to cities, counties, and nonenterprise special districts; (2) the allocation of property taxes and VLF revenues to cities that had been assigned a very low share of the property taxes under tax allocation laws; and (3) the amount of revenues required to be "passed-through" by redevelopment agencies to other local agencies. During periods of state fiscal difficulty, however, the state also has used this authority to transfer some of its fiscal burdens to local governments. For example, in 1992-93 the state began shifting city, county, and special district property taxes to K-14 districts (via ERAF) as a means of offsetting state education costs. Because of the fiscal impact of these and other state actions, local governments have long sought "protection" against future state changes in local finance.

Reforming Local Finance. Over the last two decades, the Legislature and administration have expressed interest in addressing concerns regarding local finance. For example, Chapter 94, Statutes of 1999 (AB 676, Brewer), stated that:

California's system for allocating property taxes does not reflect (1) modern needs and preferences of local communities or (2) the relative need for funding by cities, counties, special districts, redevelopment agencies, and schools to carry out their mandated and discretionary services. In addition, the current system centralizes control over property tax allocation in Sacramento and gives the state full authority to reallocate property taxes to offset state education funding obligations. The Legislature wishes to revamp the current system of property tax allocation to do the following: (1) increase taxpayer knowledge of the allocation of property taxes, (2) provide greater local control over property tax allocation, and (3) give cities and counties greater fiscal incentives to approve land developments other than retail developments.

As discussed further below, the administration's proposal would greatly limit the Legislature's authority to reform local finance.

The administration's proposal offers significant protection to noneducation local governments' revenues, but greatly reduces the Legislature's authority to reform local government finance. Specifically, our review of the administration's proposal indicates that the Legislature apparently could not change such basic components of local finance as:

We also note that while the measure decreases the Legislature's authority over local finance, the measure does not provide any increase in local resident authority over local taxes. For example, residents would continue to have virtually no authority over the allocation of local property taxes. Thus, residents could not decide to shift some local property taxes from a water enterprise special district to their library district. Similarly, residents of a county could not decide to have a portion of their local sales taxes allocated on a population basis, rather than the existing point of sale (situs) basis. Instead, the measure locks the existing local fiscal system in place, requiring future constitutional amendments any time change is needed or desired.

Given some past state actions to modify local finance laws for the fiscal benefit of the state, local government's interest in safeguarding local tax revenues is both understandable and reasonable. The state, however, has an important interest in the viability of local fiscal affairs and a key role to play in state-local finance issues. The administration's proposal would curtail this role by freezing in place current revenue structures. While this approach provides certainty for local governments (and the state), it does so at the expense of placing severe constraints on the ability of state and local governments and their residents to work together to improve the shared fiscal landscape.

We urge the Legislature to consider policies that offer local fiscal protection, but still allow the Legislature and local residents to modify revenue sources and allocations. Instead of placing restrictions on the ability of the state to alter existing fiscal structures and institutions, we recommend the Legislature consider policies that protect local revenue streams in the aggregate, yet maintain authority to alter these taxes and the allocation of these revenues among local governments. This would insure that the state no longer used local funds for state fiscal relief.

The proposed shift of VLF backfill revenues for K-14 property taxes is extraordinarily complex. To date, the administration has not articulated a rationale for this swap, although others have attributed its purpose as seeking to: (1) protect local government revenues against possible future delays in state payment of VLF backfill revenues and/or (2) improve local government land use incentives. As we discuss below, the tax swap does not appear to be justified by either of these rationales.

Swap Not Necessary to Provide Local Protection. In the current year, local governments sustained revenue reductions when payment of the VLF backfill was delayed. If the goal of the proposed swap is to give local governments protection against future delays or nonpayment of VLF backfill payments, there is a simpler solution: the Legislature could propose a VLF backfill guarantee be amended into the Constitution.

Existing Land Use Incentives. California cities and counties rely on three major statewide taxes, the VLF, property tax, and sales tax, and some smaller, locally imposed taxes. When considering future land developments, cities and counties typically consider their potential effects on these sources of revenues. Local governments usually report that they receive the greatest revenues from retail developments and, accordingly, face fiscal incentives to promote retail developments over other developments. Local governments, in contrast, frequently indicate that housing developments do not generate sufficient revenues to offset the costs to provide municipal services to new residents.

No Obvious Improvement to Land Use Incentives. To give cities and counties incentives to approve a balance of land developments (including housing), many local government observers have suggested the state decrease city and county reliance upon the sales tax and increase their reliance on the property tax. The administration, however, proposes to trade VLF revenues for property taxes. Overall, we do not see why this swap would improve local government land use incentives. In the case of housing developments, for example, cities and counties would receive higher property tax revenues, but much of this increase would be offset by greatly reduced VLF revenues, a tax allocated on a population basis. Moreover, we note that local governments do not receive property taxes from public housing developments, whereas they receive VLF revenues for the people residing in these developments.

To date, we see no information suggesting that the highly complex tax swap would be beneficial to the state or to local governments. Absent evidence to the contrary, we recommend the Legislature delete this tax swap from this proposal. We note that the local government association initiative does not include a comparable tax swap. As an alternative, the Legislature could amend the Constitution to guarantee the annual VLF backfill.

For some agencies, the requirement to contribute their share of the $1.3 billion in

2004-05 and 2005-06 will pose significant financial burdens. For example,

certain independent recreation and park districts

would lose more than 15 percent of their

total revenues in 2004-05 and 2005-06. Cities and counties—some facing considerable

fiscal pressures of their own—also will

sustain significant reductions in general purpose revenues. Finally, with the exception

of enterprise special districts (which have broad authority to raise replacement revenues

through user fees) local communities are likely to experience service reductions during the

two years that their property taxes would be reduced. Given the fiscal effect of

the administration's measure on local governments, it is important to assess the extent to which

this proposal is structured in a manner that

offers state fiscal relief while imposing the least

harm on local governments.

State Budget Relief Is Short Term. The administration's proposal offers substantial state budgetary relief for two years. As we discuss in our Overview of the 2004-05 May Revision, however, the state's fiscal problem spans a much longer period. We note that in 2006-07, after the temporary $1.3 billion relief from local governments ends, the state is scheduled to pay (1) the $1.2 billion VLF gap loan and (2) the first of five installments to reimburse local government mandate obligations (a debt that is likely to total $1.6 billion by 2006-07). Together, these local government-related obligations will pose a significant challenge for the state beginning in 2006-07.

Potential Higher State Education Costs.

The proposed reduction in property taxes for

K-14 districts could result in higher costs for the

state than under current law. While it is difficult

to predict how the property tax and VLF will perform in the future, we note that property

tax growth over the last four years has been quite robust, averaging close to 8 percent

annually. The VLF, in contrast, has grown at a rate

closer to 6 percent annually over the same period.

To the extent that the property tax continues to grow at a rate faster than the VLF,

local governments would benefit, but the state

would experience increased education funding obligations. Assuming these growth rates

prevail through 2006-07 (when the plan is fully implemented), this tax swap could result

in higher state K-14 expenditures of almost

$200 million annually. This increased expenditure obligation would continue

to increase over time.

In view of these factors, we recommend that the Legislature consider altering the proposal in order to restructure the burden on local governments and, in the process, stretch out state budgetary relief over a longer period of time. We recommend that the Legislature consider (1) reducing revenue shifts from those local governments that are less able to generate replacement revenues, (2) maximizing local control by reducing special purpose subventions rather than general purpose revenues and authorizing some local decision-making over property tax allocation, and (3) redistributing state budget savings from 2004-05 and 2005-06 into future years.

Below, we present an alternative that incorporates these features. The alternative would maintain the administration's proposed $2.6 billion in budget relief, but restructure the proposal to redistribute the impact on local governments and provide state relief over a longer period of time. It is important to note that there are numerous other alternatives that could result in similar benefits for both the state and local governments. Our suggested alternative consists of the following components:

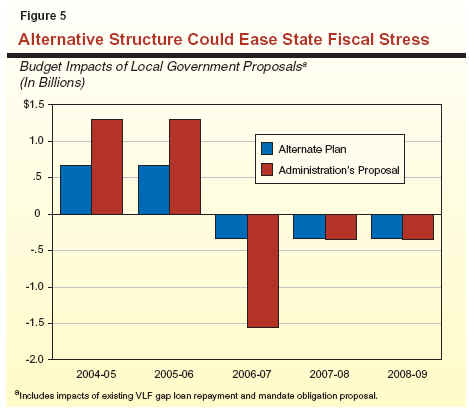

Figure 5 shows the state budget impact of the two proposals. The figure displays the revenue impacts of the property tax shift and the reduction in special subvention payments, as well as the state's payment of existing local government VLF and mandate obligations. As shown in the figure, the administration's plan would result in savings of $1.3 billion in each of the first two years, compared with the $670 million of savings in each of these years in our alternative. In 2006-07, however, the state would repay the VLF gap loan (pursuant to current law) and make the first mandate payment (pursuant to the administration's proposal) for a total of approximately $1.55 billion. In contrast, our alternative would require the VLF gap loan to be paid over a three-year period and partially offsets these liabilities by the ongoing property tax reductions for special districts. The administration's mandate repayment would be included in our alternative as well.

The administration's proposal and our alternative would result in identical total losses for local governments from 2004-05 through 2008-09, but the distribution of these losses would differ significantly. Specifically:

For the state, the alternative presented above would provide substantially lower budget savings during the initial two years, compared to the administration's proposal, but would result in significant budget relief in subsequent years. By altering various components of the proposal (and making changes to existing state obligations), our alternative provides an easier fiscal transition in 2006-07.

While critical details regarding the administration's mandate proposal are still under development, two elements of the plan would significantly improve the state's mandate reimbursement process. We discuss these elements, along with some concerns regarding the proposal, below.

Tearing Up the Mandate Credit Card. Usually, when the state faces difficulties funding a program, the state modifies or repeals the program. In the case of mandates, however, state actions to defer mandates costs result in local agencies being required to implement programs without funding—representing essentially an involuntary loan from local governments to the state. In addition, state actions to defer mandates costs tend to reduce the state's incentives to review and reduce mandate program costs. In our view, adopting the administration's proposal to sunset most unfunded mandates would increase state accountability regarding mandates. (We also note that legal challenges relating to the state's failure to fund mandates are pending in lower courts and it is conceivable that future court rulings regarding unfunded mandates could constrain the Legislature's authority more broadly than the administration's proposal.)

Ending Mandate Suspension Process. Legislative actions to suspend mandates in the annual budget frequently result in unreimbursed local costs because it makes it very difficult for local agencies (or others) to understand the requirements of state laws. As an example, Figure 6 explains the steps a local agency official would need to take to know how long a stray dog must be held at a shelter before it could be euthanized. In addition, local agencies often incur unreimbursed local costs under the suspension process because it is difficult to change local policies immediately after a mandate is suspended. In our view, the administration's proposal to reform a system that makes state laws difficult to understand and imposes unreimbursed costs on local agencies is appropriate and commendable.

|

Figure 6 Steps Required to Understand State Law |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Concerns Regarding Administration's Mandate Proposal. Based on the materials available at this time, we note several areas of concern regarding the administration's proposal. Specifically, it:

For about a year, the Assembly Special Committee on Mandates has been reviewing individual state mandates and the mandate process. In April 2004, drawing from testimony provided from a wide array of parties and our previous mandate analyses, our office presented a proposal for an accountable, expedited mandate process. Figure 7 summarizes our proposal, which contains many similarities to the administration's proposal, most notably the establishment of an automatic sunset requirement and the repeal of the mandate suspension process.

|

Figure 7 A Mandate Reimbursement Process With Greater |

||

|

Time |

Action |

Maximum

Elapsed Time |

|

|

The Legislature passes a law, a state agency

promulgates a regulation, the Governor signs an executive order. |

|

|

Up to 12 months |

Local agencies may file a claim up to one year

after (1) a mandate is created or (2) they experience increased costs. |

12 |

|

Up to 12 months |

Reconfigured Commission on State Mandates (CSM)

deliberates. State and local agencies fund CSM activities through

reimbursements and fees. |

24 |

|

Up to 4 months |

If CSM finds a

mandate, the State Controller�s Office (SCO), with assistance from an

ongoing local agency advisory body, develops a �reasonable

reimbursement methodology� that balances accuracy with

simplicity�and specifies a future date when revision to the

methodology shall be considered. |

28 |

|

Up to 2 months |

The CSM reviews the proposed SCO reimbursement

methodology. The CSM may return the methodology to SCO for revision if

it finds the methodology inconsistent with the CSM mandate

determination. |

30 |

|

Up to 2 months |

If necessary, the SCO reviews CSM comments and may

make changes to its methodology. |

32 |

|

Up to 2 months |

The CSM either approves the SCO methodology or

adopts findings identifying its concerns with the methodology. The CSM

reports the mandate, the SCO methodology, and any concerns to the

Legislature and administration. |

30 - 34 |

|

Up to 6 months |

The Legislature funds the mandate (either in

legislation or the budget act) and specifies the reimbursement

methodology. If the Legislature does not fund the mandate, the SCO shall

notify affected local agencies that the mandate is invalid, pursuant to

state statute. Legislative Counsel prepares draft legislation for the

chairs of the local government policy committees to introduce to codify

the repeal of the mandate. |

36 - 40 |

|

Annually thereafter |

Local agencies

submit claims for mandate reimbursement in the fiscal year after costs

are incurred. The Governor proposes and Legislature appropriates funding

for mandates in the annual budget bill, including any funding needed to

pay prior-year mandate deficiencies. The annual suspension process in

the budget bill is repealed. If mandate reimbursement is not provided,

the mandate is invalid. (As in above, the SCO will notify local agencies

and Legislative Counsel will prepare draft legislation for the chairs of

the local government policy committees to introduce to codify the repeal

of the mandate.) If a valid local claim is unpaid for more than two

years after submittal, a local agency may bring action in superior court

to have the mandate declared invalid. |

|

Other elements of our proposal, however, differ notably from the administration's proposal, including our common treatment of all mandates (education, noneducation, and labor relations), the assigned roles and responsibilities of state agencies, and the process for determining a reimbursement methodology. In general, while we find much about the administration's proposal to recommend, we think the conceptual approach outlined in our alternative offers significant advantages. These advantages are highlighted in Figure 8. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature substitute it for the administration's approach.

|

Figure 8 Advantage of LAO Mandate Approach Over |

|

|

|

�

Creates a single, expedited process for all mandates. |

|

�

Greatly simplifies the mandate claiming process. |

|

�

Avoids conflicts of interest in developing mandate cost

estimates and reimbursement methodologies. |

|

�

Strengthens the mandates determination process by

increasing state agency participation, restructuring the commission, and

establishing reasonable deadlines. |

The administration has proposed a significant local government package with provisions that help address the state's budgetary difficulties, alter long-term state-local fiscal interactions, and reform the mandate process. Our review of the proposal indicates that it would increase the stability of local finance and increase accountability in the mandate process. We also find, however, that the proposal lacks overall policy coherence and, in exchange for short-term state fiscal relief, locks in place the current flawed state-local fiscal structure.

Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature review the proposal with the objective of bringing it into greater alignment with legislative goals and state fiscal objectives. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature:

The VLF is an annual fee on the ownership of a registered vehicle in California, levied in lieu of taxing vehicles as personal property. Revenues from the VLF are dedicated to local governments. The fee is based on the depreciated value of the vehicle according to a set schedule. Vehicle owners currently pay a 0.65 percent rate, with the difference between this and the former 2 percent rate paid by the state General Fund (see "VLF Backfill").

In 1998, the Legislature adopted a schedule of VLF rate reductions, which resulted in the rate falling from 2 percent to 0.65 percent by 2000. In conjunction with these VLF reductions, cities and counties continued to receive the same amount of revenue that they would have under the 2 percent rate, with the reduced VLF revenues from vehicle owners replaced by General Fund revenues or backfill. Under current law, the backfill for 2004-05 is estimated to be $4.1 billion.

The previous administration made a determination in June 2003 that there

were insufficient funds for the state to continue making General Fund backfill payments to

local governments. The backfill ceased and the VLF rate paid by vehicle owners increased

to 2 percent approximately three months later.

The "gap" period between when the backfill

ceased and the increased VLF rate occurred resulted

in a loss in local revenue of $1.2 billion, essentially representing a loan to the state scheduled to

be repaid to local governments in 2006-07. By executive order, the current

administration returned the rate to 0.65 percent in

November 2004.

In 1992-93, the state directed each county auditor to establish an Educational Revenue Augmentation Fund (ERAF) and annually transfer to this fund property taxes that otherwise would be allocated to cities, counties, and special districts. In 1993-94, the state increased the annual amount of property taxes shifted from these local agencies. In 2003-04, the amount of property taxes deposited to ERAF totals about $5 billion. The state's original purpose in creating ERAF was to allocate the property tax funds to K-14 districts, thereby offsetting state education spending. As part of the "Triple Flip" agreement discussed below, however, the state pledged to use some ERAF revenues to replace transferred city and county sales tax revenues.

The state's Economic Recovery Bonds, approved by the voters in March 2004, are secured by a pledge of revenues from an increase in the state's share of the sales and use tax of one-quarter cent beginning July 1, 2004. The share of the tax going to local governments will be reduced by the same amount and, in exchange, local governments will receive an increased share of the local property tax (and K-14 districts a reduced share) during the time the one-quarter cent is being used to pay off the bonds (estimated to be between 9 and 14 years). This shift in revenues between the state and local governments is known as the "triple flip."

| Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by Mark Ibele and Marianne O'Malley. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |