Chapter 794, Statutes of 2002 (AB 1401, Thomson), directed the Legislative Analyst’s Office (LAO) to evaluate the effectiveness of the measure in providing heath care coverage to individuals who are otherwise unable to obtain health benefits (the “hard-to-insure”). While we found there is now only limited information available to assess the outcome of various aspects of AB 1401, we concluded the measure has increased the state’s capacity to help hard-to-insure individuals access health coverage using the same level of state resources. Based upon our evaluation, we present several recommendations to improve the program by potentially reducing its costs to enrollees and the state.

|

Figure 1 Key Health Insurance Terms and Definitions |

|

|

|

|

|

Group health insurance |

Health insurance purchased through a group that exists for some

purpose other than buying insurance, such as a workplace, labor

union, or |

|

Individual health insurance |

Health insurance purchased on an individual basis which covers only one person and, in some cases, members of his or her family. |

|

Major Risk Medical |

California’s comprehensive health insurance program for individuals

who are unable to obtain coverage in the individual insurance

market. |

|

Post-MRMIP coverage |

Health coverage that is offered to MRMIP subscribers who have reached the 36-month time limit in that program. |

|

Continuation coverage |

A

temporary extension of group health insurance coverage that is |

|

Health Insurance Portability and |

Health coverage available to individuals who lose their group coverage and meet certain criteria for any health plan that sells individual coverage. State law limits the rates that can be charged for this coverage. |

|

Conversion coverage |

Health coverage available to individuals who lose their group

coverage and meet certain criteria from the insurance carrier that

originally provided them coverage. The benefits and rates charged

for this coverage are now |

The measure further directs the LAO to report on the effectiveness of its provisions in providing health benefits to individuals who otherwise would be unable to obtain that coverage. Specifically, the study is to include the following:

Basic demographic information regarding individuals enrolled in MRMIP before and after the enactment of AB 1401.

Basic demographic information regarding individuals who were shifted from the MRMIP caseload to health coverage in the individual market in accordance with the provisions of AB 1401. (Throughout this report, we refer to this as “post-MRMIP” coverage. We discuss this aspect of AB 1401 in more detail later in this report.)

Basic demographic information regarding individuals receiving so-called “continuation,” “conversion,” or certain other individual coverage in the private health plan and insurance market. (We also discuss these provisions to provide more continuity of health coverage in greater detail later in this report.)

An assessment of AB 1401’s effect on the affordability and accessibility of health insurance in the health insurance market for individuals receiving coverage under this act.

An assessment as to whether the cost of coverage and level of benefits under MRMIP and post-MRMIP coverage should be changed.

Recommendations for changes in the affected programs, including whether the changes made to the state’s high-risk pool should continue.

In preparing this report, we obtained information from the Managed Risk Medical Insurance Board (MRMIB), which administers MRMIP and so-called post-MRMIP programs, on the level of enrollment in these programs before and after the enactment of AB 1401. We also obtained information from the largest California insurance carriers (health plans and insurers) regarding the number of individuals receiving certain group and individual health coverage in the private market. We consulted with the California Department of Insurance (DOI), the Department of Managed Care (DMHC), MRMIB, and other state high-risk pool experts on various issues related to AB 1401. Lastly, we also reviewed published information regarding high-risk health insurance pools in other states for purposes of comparison with the programs modified by AB 1401.

How the Program Works. The MRMIP, the state’s high-risk pool, provides comprehensive health insurance benefits for Californians who are generally unable to obtain coverage in the individual insurance market. Typically, these individuals are considered high-risk for coverage by health insurers because they have “pre-existing medical conditions”-medical conditions that were treated or diagnosed by a doctor before the individual applied for health insurance. For example, someone with a chronic heart condition might be turned down for coverage in the individual health insurance market if the insurance carrier concluded that the costs of ongoing medical care over time for the applicant would likely exceed the premiums collected from that individual. The MRMIP has been in operation since 1991. (See the nearby text box for more information on high-risk pools operated throughout the country.)

High-Risk Health Insurance Pools in Other StatesCurrently, thirty-three states have created high-risk pools to provide access to health coverage for the hard-to-insure population. While the purpose of these pools is generally similar-to provide comprehensive health insurance benefits to individuals with pre-existing conditions-the methods used by various states differ. High-risk pools typically include a lifetime limit on the amount of benefits received, deductibles, and waiting periods for coverage for pre-existing conditions. The maximum lifetime benefits range from $500,000 to $2 million. The annual deductibles, which vary according to the health plan chosen by the insured, can range between $250 and $10,000. A number of state high-risk pools also contain provisions that exclude coverage for a certain period of time following an individual’s enrollment in the program. These exclusion periods range from For many of the high-risk pools, premiums paid by subscribers (the person who receives health insurance benefits on behalf of himself or his dependents) typically fund between 50 percent and 60 percent of the entire cost of operating the heath insurance pool (including medical claims and administrative costs), with the remaining resources coming from some form of public subsidy. In most states, the source of this subsidy is some form of assessment on insurers. In California, however, the subsidy is funded with tobacco tax revenue. Some states provide an additional premium subsidy to lower-income individuals participating in the pool. Some states cap the premiums paid through high-risk pools, although even the capped rate may exceed the rates charged in the private market by 10 percent to 100 percent. States control the costs of their high-risk pools through caps and waiting lists in periods when state funding is limited or unable to keep pace with growth in health care costs. Many states have developed comprehensive disease management programs as a means to improve the quality of care provided to participants in the pools and to reduce health care costs. These programs typically involve technical expertise in a particular disease, positive reinforcement and support from a case manager, and the coordination among health care providers and the enrollee to insure that the appropriate medications are being used. |

Such high-risk individuals are eligible to enroll in MRMIP to obtain health care coverage for themselves and their family if they are California residents, and can demonstrate that they were unable to secure other adequate coverage on their own or are only able to access individual coverage at a cost that is greater than the MRMIP subscriber rate. All individuals must also have been determined to be ineligible to receive a temporary extension of group health insurance (continuation coverage) from their former employer’s health plan. (A discussion of continutation coverage and other federal and state efforts to assist the hard-to-insure in receiving health coverage can be found in the text box below.)

Other State and Federal Measures Assist Medically High-Risk IndividualsBesides creating high-risk insurance pools, both the state and federal governments have enacted various additional measures to assist individuals who may find it difficult to obtain health coverage for themselves or their families as the result of a pre-existing medical condition. COBRA Coverage. The federal Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) allows employees and/or their family members to temporarily extend their coverage in a group health plan when that family’s health coverage would otherwise be lost due to certain events, such as individual’s voluntary or involuntary loss of employment or a divorce from the primary person insured. Depending upon an individual’s circumstances, this so-called continuation coverage is available from 18 to 36 months. Continuation coverage is typically more expensive to an individual than the previous group coverage. Under group coverage, an individual probably shared the cost of his or her health coverage with his or her employer, but COBRA participants may be required to pay up to the entire cost of coverage by themselves. Under federal law, the COBRA rules provide continuation of health coverage for persons associated with larger employers-those with more than 20 employees. In 1997, California established a Cal-COBRA program to provide coverage similar to that required under COBRA to employees who worked for smaller employers with between 2 and 19 employees. Generally, Cal-COBRA participants may be required to pay no more than 110 percent of the total cost of coverage they previously received through their employer’s health plan. Both COBRA and Cal-COBRA offer certain advantages to individuals transferring from group to individual coverage, and in particular for the hard-to-insure since they are more likely than others to need health coverage. Individuals eligible for continuation coverage are given the right to keep their group coverage under certain conditions when it would otherwise end. Also, eligible individuals receiving this coverage have the right to keep nearly the same premium rates as were charged to their former employer for group coverage. These guarantees do not apply if an individual later transfers to the individual insurance market. HIPAA Coverage. The federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) also assists individuals who might encounter difficulty because of their medical condition in shifting from their former employer’s group coverage to individual coverage. To be eligible for HIPAA coverage, the individual must have previously had group health coverage for 18 months or longer and must currently have no other health insurance. Every carrier that sells health coverage in the individual insurance market must offer HIPAA coverage to a person eligible under HIPAA. Under state law, additional protections also exist that limit the rates that health insurance carriers can charge to certain individuals who are protected under HIPAA. Conversion Coverage. State law also requires group insurance carriers to provide certain subscribers “conversion” coverage. This means that an individual must be permitted to transfer from group health insurance coverage to individual coverage without having to provide evidence of their insurability in cases when the employer has terminated the group health coverage. To be eligible for conversion coverage, the individual must have previously had group coverage for at least three months and currently have no health insurance coverage. Individuals who are eligible for conversion coverage can only obtain this type of coverage from the insurance carrier that originally provided them group coverage. |

The MRMIP subscribers can select coverage from any of the private health plans in their county that are participating in the program. Currently, four plans are offering MRMIP coverage in various locations throughout the state, including both health maintenance organizations and a preferred provider organization. Depending on the type of coverage selected, a waiting period of three months may apply for some or all medical services.

How the Program Is Funded. The MRMIP is supported with contributions collected from persons who have enrolled in the program and funding appropriated from Proposition 99, a measure passed by voters in 1988 that increased taxes on tobacco products for various health-related and environmental protection programs. Historically, the state has appropriated $40 million each year from Proposition 99 for MRMIP. Given this relatively fixed level of funding, MRMIB has capped the number of individuals that can be enrolled in the program at any given time to stay within its appropriated resources. As of December 2004, 8,844 individuals were enrolled in the program.

The premiums paid by MRMIP subscribers are between 25 percent and 37.5 percent, higher than what an insurance carrier would charge a non-high-risk person for similar coverage. The monthly premiums paid by subscribers are capped, and can range from a few hundred dollars to a few thousand dollars a month depending on the plan selected and the age and geographical location of the enrollee. Given these premium levels, MRMIP subscribers’ incomes are generally higher than those of persons in other state-subsidized health programs. The most recent data compiled by MRMIB indicate that approximately two-thirds of MRMIP subscribers live in households with incomes that equal or exceed 300 percent of the federal poverty level (approximately $38,500 annually for a family of two).

In addition to monthly premiums, enrollees must also make co-payments to help offset the cost of their care, which are generally limited to $2,500 per year for an individual and $4,000 per year per household. The program also limits the cost of the health care benefits that a MRMIP enrollee can receive to $75,000 per year and $750,000 in their lifetime.

Before the passage of AB 1401, a subscriber could continue in MRMIP indefinitely so long as he or she continued to pay the required health plan premiums and did not become eligible for other health care coverage (such as Medicare). As subscribers maintained their coverage, the program caseload grew. Eventually, the relatively fixed level of funding provided for MRMIP resulted in waiting lists that slowed the acceptance of new applicants. Rising health coverage costs meant that, over time, the program could not maintain the same level of enrollees it once had. The maximum number of enrollees in the program (the program’s enrollment cap) declined from 21,900 in 1998 to 14,658 in 2002. At the time AB 1401 was enacted, in September 2002, the MRMIP’s waiting list was more than 1,500 persons.

In 2000, two years before AB 1401 was enacted, the Legislature approved a one-time augmentation of $10 million in Proposition 99 funds to maintain the number of persons enrolled in MRMIP and to reduce the size of the waiting list for the program. However, Governor Davis vetoed $5 million of the $10 million augmentation, stating that it was inappropriate to increase support for MRMIP using resources from Proposition 99, which have generally been declining along with the sales of tobacco products. In lieu of further increases in state funding for MRMIP, the Governor proposed that the Legislature and the insurance industry work “to develop market-based solutions to provide coverage to persons with financial resources but reduced access to private health insurance.”

Certain provisions of AB 1401 were intended to address an imbalance between group insurance coverage and individual insurers in providing coverage for the hard-to-insure. Specifically, coverage for these individuals was perceived as shifting from the group insurance market to the individual insurance market.

Before AB 1401 was enacted, group insurance carriers were required to allow high-risk individuals to convert from group insurance to individual insurance when an employer had terminated group health insurance. However, the terms under which this coverage was made available were not closely regulated by the state and as a result were often unattractive to the individuals eligible for that coverage because of its high cost and limited benefits. As a result, some individuals would seek Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) coverage in the individual health insurance market. The terms by which this HIPAA coverage must be offered are more closely regulated and thus potentially more attractive to individuals.

Assembly Bill 1401 was enacted in response to the Governor’s call in 2001 for a new, market-based approach to address MRMIP’s growing waiting list and funding constraints. This legislation consisted of several separate components. The key provisions of the measure are summarized in Figure 2 and discussed below.

|

Figure 2 Main Provisions of AB 1401 |

|

|

|

|

|

Major Risk Medical |

Limits enrollment in MRMIP to 36 months. |

|

Post-MRMIP |

Requires all health carriers in the individual insurance market to

offer Coverage must be generally comparable to that available under MRMIP. Insurers must charge premiums that are 10 percent higher than in MRMIP. |

|

Continuation coverage |

Insurance carriers must offer Cal-COBRA for up to 36 months for individuals with less than 36 months of Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (COBRA) or Cal-COBRA coverage. |

|

Conversion coverage |

Rates and benefits for conversion coverage must be similar to those

|

|

Comparative information on |

Requires Department of Managed Care and Department of Insurance to

|

Time Limits on MRMIP and Creation of Post-MRMIP Coverage. Two key provisions of AB 1401 impose a time limit on participation in MRMIP and expand market-based coverage for these subscribers. Specifically, the measure limits to 36 months the length of time an individual can continuously enroll in MRMIP. Also, under AB 1401, all insurance carriers operating in California’s individual health market are required to offer health coverage (at specified rates, as described below) to individuals “graduating” from MRMIP after this 36-month period of enrollment so long as they enroll within a certain time period. (In this report, we refer to this private sector availability of health benefits as post-MRMIP coverage.) The intent of this change was to transition these hard-to-insure individuals into the individual insurance market.

Under AB 1401, the post-MRMIP health insurance coverage offered must be generally comparable to one of the insurance plans currently available under MRMIP. The insurance carriers are required by statute to charge the “graduates” 10 percent more in premiums than subscribers must pay for MRMIP coverage. This guaranteed coverage mirrors the coverage available in MRMIP, except that the benefits are capped at $200,000 annually, with a new lifetime benefit cap of $750,000.

The state and insurance carriers jointly subsidize post-MRMIP coverage because the premiums paid by subscribers do not cover its full cost. The state’s subsidy for the post-MRMIP, as well as MRMIP, coverage comes from part of the state’s appropriation of tobacco tax revenue. These changes to MRMIP were adopted as a pilot program that by law will run from September 1, 2003 to September 1, 2007.

California Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (Cal-COBRA) and Conversion Coverage Changes. In addition to limiting the length of enrollment in MRMIP and creating post-MRMIP coverage, AB 1401 made two other key policy changes intended to improve access to health coverage for medically hard-to-insure individuals. These changes in law are permanent and would not sunset as do some other provisions of AB 1401.

Cal-COBRA. Group health plans and health insurers must now offer Cal-COBRA coverage for up to 36 months for individuals with less than 36 months of COBRA or Cal-COBRA coverage. Before AB 1401, this coverage was available for 18 to 36 months depending on the individual’s status. This coverage must be available to all qualified individuals and family members who began continuation coverage on or after January 2003.

Conversion Coverage. As of September 2003, group health plans and health insurers must offer conversion coverage at rates and with benefits that are comparable to those available under HIPAA. Before the passage of AB 1401, conversion policies provided limited benefits and with no limitation on the rates.

Comparative Information. Assembly Bill 1401 also requires DMHC and DOI to develop written comparisons (called “matrices”) of benefit packages for individuals either graduating from MRMIP or those eligible for HIPAA, conversion, or individual commercial market coverage. These matrices have been posted on the departments’ web sites.

The findings from our analysis of the implementation to date of the provisions of AB 1401 are summarized in Figure 3 and discussed in more detail below. We note that these findings are preliminary in nature. Most of the changes made under AB 1401 have been in effect for only about two years and our analysis is based on roughly one year’s worth of data.

|

Figure 3 Outcome of AB 1401 (Thompson) Uncertain |

|

LAO Findings |

|

Major Risk Medical Insurance Program (MRMIP) enrollment dropped

|

|

After the implementation of the AB 1401 pilot, MRMIP enrollees were

on |

|

Post-MRMIP subscribers were on average more costly than individuals

|

|

The impact of AB 1401 on conversion, continuation, and Health

Insurance Portability and Accountability Act coverage is not yet

clear and may not be |

|

Some anecdotal information suggests that post-MRMIP coverage has

become unaffordable for some graduates, but the extent of this

problem is unclear |

|

Assembly Bill 1401 has increased MRMIP’s capacity to help

hard-to-insure |

Pursuant to the requirements of AB 1401, we evaluated data on the number of individuals enrolled in MRMIP before and after the enactment of this legislation. Specifically, we reviewed total enrollment in the program at specific points in time and enrollment by gender and age. The data indicate that enrollment generally declined prior to the enactment of AB 1401, and then significantly dropped following the implementation of the pilot program on September 1, 2003, as discussed further below.

As seen in Figure 4, prior to the implementation of the pilot, enrollment levels in MRMIP had been generally declining. Between 1998 and 2003, enrollment dropped by approximately 21 percent. As noted earlier in this report, this drop in enrollment was not due to a decrease in the demand for MRMIP coverage. Rather, it was largely due to the fixed amount of funding provided for the program over time despite ongoing increases in health care costs. Program enrollment data indicate that, before the enactment of AB 1401, the program had been typically providing coverage at its enrollment limit and had accumulated a significant waiting list.

|

Figure 4 MRMIP Enrollees—By Gendera |

||||

|

As of August 31 |

||||

|

Year |

Females |

Males |

Totals |

Percent |

|

1998 |

11,634 |

8,051 |

19,685 |

59% |

|

1999 |

12,448 |

8,525 |

20,973 |

59 |

|

2000 |

11,569 |

8,032 |

19,601 |

59 |

|

2001 |

9,724 |

6,777 |

16,501 |

59 |

|

2002 |

9,724 |

6,916 |

16,640 |

58 |

|

2003 |

8,966 |

6,502 |

15,468 |

58 |

|

2004 |

4,978 |

3,591 |

8,569 |

58 |

|

|

||||

|

a These figures

reflect the actual caseload for specific points in time. Due to |

||||

In 2004, the year following the implementation of the pilot program, enrollment dropped by 45 percent compared to the prior year. This decline is largely due to the disenrollment of over 9,600 MRMIP enrollees (as of August 2004) who had reached their 36-month time limit.

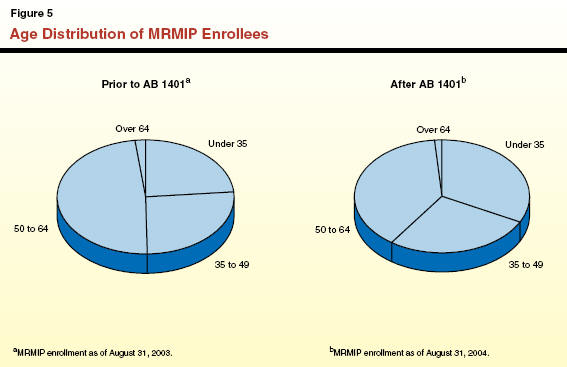

Our analysis indicates that the gender distribution of enrollees remained constant before and after the implementation of AB 1401. However, our review of age distribution data indicates that the pool of MRMIP enrollees as a whole generally became younger after the pilot was implemented. As seen in Figure 5, before AB 1401 was implemented, 50 percent of the enrollees were under 50 years of age. After AB 1401 was implemented, this group comprised 60 percent of total enrollment. According to the program’s actuary, this shift in age occurred because a large group of older individuals shifted to post-MRMIP coverage, which in turn made “space” available for younger individuals to enter the MRMIP program.

Additional information on the age distribution in MRMIP since 1998 is presented in Figure 6.

|

Figure 6 MRMIP Enrollees—By Age |

|||||

|

As of August 31 |

|||||

|

Year |

Age |

|

|||

|

Under 35 |

35 to 49 |

50 to 64 |

Over 64 |

Totals |

|

|

1998 |

4,188 |

5,595 |

9,504 |

398 |

19,685 |

|

1999 |

4,732 |

5,719 |

10,032 |

490 |

20,973 |

|

2000 |

4,245 |

5,226 |

9,635 |

495 |

19,601 |

|

2001 |

3,348 |

4,290 |

8,416 |

447 |

16,501 |

|

2002 |

3,485 |

4,352 |

8,363 |

440 |

16,640 |

|

2003 |

3,644 |

4,050 |

7,460 |

314 |

15,468 |

|

2004 |

2,786 |

2,332 |

3,331 |

120 |

8,569 |

If this shift toward younger enrollees in MRMIP proves to be permanent, it could significantly affect the health insurance costs and caseload of the program over time. It is possible that a pool of younger enrollees in MRMIP will result in lower overall health care costs for the state program, which might enable the state to cover more high-risk individuals through this program with the existing level of resources.

Enrollment estimates prepared by the program’s actuary suggest that the health care costs in MRMIP are declining. Prior to the implementation of AB 1401, the actuary reported that the average annual claims paid were approximately $7,200 per enrollee. Following the implementation of AB 1401, the actuary reported that the average claims paid dropped to approximately $6,300 per enrollee per year. However, we view these data as preliminary and potentially subject to change. Notably, the claims data for the period after the implementation of AB 1401 are based on claims activity for only 14 months. Accordingly, we believe further monitoring of this data is warranted to see if this trend continues in the future.

As directed by AB 1401, we also evaluated basic demographic data regarding the individuals who have been enrolled in post-MRMIP coverage after the enactment of the legislation. These are individuals who reached the 36-month time limit for enrollment in MRMIP and successfully enrolled in post-MRMIP coverage. Specifically, we reviewed total enrollment in the program as reported by the health plans at two points in time-as of December 2003 and again as of December 2004-according to participants’ gender and age. We also assessed aggregate data on the financial claims paid by the state to participating insurance carriers for post-MRMIP enrollees during the same time period.

Our analysis of enrollment data for the time periods described above indicates that enrollment dropped by over 900 individuals between December 2003 (7,058 enrollees) and December 2004 (6,122 enrollees), as shown in Figure 7. Generally, this outcome occurred because some graduates of MRMIP are not enrolling in post-MRMIP and some individuals who do enroll in post-MRMIP are subsequently disenrolling.

|

Figure 7 Post-MRMIP Enrollment |

||||

|

Age |

Females |

Males |

Totals |

Percentage in Age Group |

|

As of December 31, 2003 |

||||

|

Under 35 |

642 |

583 |

1,225 |

17% |

|

35 to 49 |

1,013 |

822 |

1,835 |

26 |

|

50 to 64 |

2,396 |

1,477 |

3,873 |

55 |

|

Over 64 |

78 |

47 |

125 |

2 |

|

Totals |

4,129 |

2,929 |

7,058 |

100% |

|

Percentage |

59% |

41% |

— |

— |

|

As of December 31, 2004 |

||||

|

Under 35 |

621 |

574 |

1,195 |

20% |

|

35 to 49 |

944 |

771 |

1,715 |

28 |

|

50 to 64 |

1,942 |

1,189 |

3,131 |

51 |

|

Over 64 |

55 |

26 |

81 |

1 |

|

Totals |

3,562 |

2,560 |

6,122 |

100% |

|

Percentage |

58% |

42% |

— |

— |

Our review further indicates that the gender distribution of individuals in post-MRMIP coverage mirrors the historical distribution of the individuals enrolled in MRMIP. Also, the data indicate that over time the age distribution of post-MRMIP graduates had begun to resemble the age distribution in MRMIP prior to AB 1401, with roughly one-half of the enrollees over 50 years of age.

Our review of the aggregate claims information for January through December 2004 indicates that health care costs were higher for the post-MRMIP graduates than for MRMIP enrollees. During this time, the program paid approximately $71 million in insurance claims for on average 6,542 post-MRMIP enrollees (the average number of enrollees each month) or approximately $10,800 per individual. That is significantly more than the $6,300 per enrollee cost of claims paid for persons enrolled in MRMIP during a roughly overlapping period of time. Presumably, this is because the post-MRMIP subscribers are sicker on average than MRMIP subscribers.

If this trend of higher health care costs for post-MRMIP coverage is permanent-and further monitoring is warranted to see if this is indeed the case-it has important implications for the caseload and costs of post-MRMIP coverage over time. However, we also note that despite the higher overall cost of post-MRMIP coverage, this coverage will be less expensive to the state than subscriber enrollment in MRMIP. This is because post-MRMIP coverage is supported with substantial premiums from subscribers and subsidies from insurance carriers, and not just state funds.

Pursuant to the requirements of AB 1401, we reviewed basic demographic data regarding individuals enrolled in certain types of coverage required in the private health insurance market. Specifically, we collected data from the largest health insurance carriers in California regarding the number of individuals enrolled and the age and gender distribution of those who were receiving coverage through (1) Cal-COBRA, (2) HIPAA, and (3) conversion coverage. This data is shown in Figure 8.

|

Figure 8 Frequency of Coverage

in Private Market |

|||

|

As of August 31, 2004 |

|||

|

|

Cal-COBRA |

HIPAA

|

Conversion Coverage |

|

Total number of beneficiariesb |

8,828 |

878,870 |

4,316 |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

|

Male |

3,581 |

426,711 |

1,819 |

|

Female |

4,671 |

452,158 |

2,497 |

|

Age |

|

|

|

|

<29 years |

2,494 |

357,444 |

540 |

|

30‑49 |

3,314 |

312,087 |

1,087 |

|

50‑64 |

2,418 |

206,428 |

2,462 |

|

65+ |

28 |

2,911 |

227 |

|

|

|||

|

a Based on sample of largest carriers. |

|||

|

b Total number of beneficiaries may not match totals by gender and age. Some of the insurance companies did not provide gender and age information for each category. |

|||

Data Limitations. The data we compiled provides point-in-time descriptions of the individuals enrolled in the coverage mentioned above. However, we were unable to draw any significant conclusions as to the impact AB 1401 had on enrollment in these types of coverage. That is partly because the effective date of some parts of the legislation is so recent that their effects are not yet fully reflected in the available data. For example, individuals eligible for conversion coverage under AB 1401 are generally required to exhaust Cal-COBRA or COBRA coverage before they can access conversion coverage. Effective January 2003, AB 1401 lengthened the time individuals have access to continuation coverage through Cal-COBRA to 36 months. Thus, the full impact of this provision on conversion coverage would not become apparent until sometime after December 2006.

Pursuant to AB 1401, our office was directed to evaluate whether the act affected the affordability and accessibility of health insurance for individuals who might encounter difficulty obtaining coverage because of pre-existing medical conditions. We focused our analysis on the potential effects of the MRMIP and post-MRMIP programs because, as noted earlier, the data available to us at this time provide little conclusive information on the effects of AB 1401 requirements related to Cal-COBRA continuation and conversion coverage.

Effect on the Affordability of Coverage. In assessing the effect of AB 1401 on the affordability of coverage, we specifically evaluated how the measure affected existing enrollees, individuals waiting to enroll in MRMIP, and enrollees in post-MRMIP coverage.

In regard to existing MRMIP enrollees, recent survey data collected by MRMIB suggest that affordability is indeed a concern. A 2004 survey indicated that 46 percent of MRMIP enrollees who have disenrolled from the program reported that they did so because they found that MRMIP premiums were no longer affordable. That figure dropped to 23 percent in the 2005 survey. However, AB 1401 did not modify the rates paid by the existing MRMIP subscribers. (The MRMIP premiums have been increased recently, but not as a result of AB 1401.) Thus, we conclude that AB 1401 did not directly affect the affordability of assistance for existing MRMIP enrollees.

We also examined whether AB 1401 had any other effects on the affordability of coverage for persons who are on waiting lists for MRMIP coverage or those who enroll in post-MRMIP coverage. In theory, AB 1401 could have made health coverage more affordable for a greater number of hard-to-insure persons by adding post-MRMIP coverage and by opening up “room” for additional persons who would otherwise have to continue to wait to enroll in MRMIP. However, a lack of available data make it difficult to gauge the actual impact the act had for individuals enrolling in post-MRMIP coverage. Some anecdotal information suggests, for example, that post-MRMIP coverage has also become unaffordable for some MRMIP graduates. The extent of this problem is not clear. Although insurance carriers record the reason why a post-MRMIP enrollee’s coverage has been cancelled, the categories of reasons that are recorded to explain disenrollments are broad and overlap with one another. Furthermore, no data are available on persons who “timed out” of the regular MRMIP after 36 months and chose not to enroll in post-MRMIP coverage-possibly because it was found not to be affordable.

Impact on the Accessibility of Health Insurance. We evaluated the effects of AB 1401 on accessibility of health insurance coverage in MRMIP and post-MRMIP coverage. Specifically, we evaluated the enrollment levels for each program, the waiting list for MRMIP, and reviewed the demographic characteristics of the individuals enrolling in both programs. Overall, we found there was a net gain in the state’s capacity to provide coverage for hard-to-insure individuals using the same level of state resources.

Specifically, as of December 2004, the regular MRMIP program had the capacity to provide coverage for 10,718 persons, the number established at that time as the enrollment cap. At that same time, an additional 6,122 individuals were enrolled in post-MRMIP coverage. Together, through MRMIP and post-MRMIP, MRMIB could have provided comprehensive health coverage to as many as 16,840 individuals. This capacity is roughly 15 percent greater than the enrollment cap of 14,658 persons that existed in 2002 before AB 1401 was enacted.

Our analysis indicates that the AB 1401 pilot has also increased the speed at which individuals can access coverage through MRMIP. Before the enactment of AB 1401, the waiting period for enrollment typically ranged from six months to one year. As of December 2004, the waiting list had been reduced to 44 individuals. Enrollment of these 44 was placed on hold only because they still needed to fulfill a waiting period required for the program, not because of any limit on space in the program. As of December 2004, MRMIP was providing coverage to 8,844 individuals, or roughly 1,870 individuals fewer than the program’s enrollment cap. Thus, additional applicants would be able to enroll in MRMIP with little delay.

We noted earlier in this report that the gender distribution in MRMIP and post-MRMIP did not change after the implementation of AB 1401. This information suggests that males and females continued to access the programs at the same rate after the implementation of the pilot. Monthly summary data reported by MRMIB, and our own analysis of county-level data, further indicate that the geographic distribution of individuals enrolled in MRMIP likewise did not change following the enactment of AB 1401.

One important remaining question is whether this initial gain in overall capacity to assist the hard-to-insure will stand up over time. Our review of enrollment data indicates that a significant percentage of graduates enrolled in post-MRMIP coverage after they reached the 36-month time limit in MRMIP. Of the almost 10,000 individuals who graduated from MRMIP between September 2003 and December 2004, 83 percent enrolled in post-MRMIP coverage for at least some amount of time. However, by December 2004, over one quarter of these individuals had disenrolled from post-MRMIP coverage.

Currently, we do not have sufficient information to determine whether these enrollment and disenrollment trends are a cause for concern or a positive policy development. If a large number of individuals are opting not to enroll in post-MRMIP coverage, or are disenrolling from such coverage, because they are able to obtain health coverage elsewhere (such as through Medicare or an employer), the pilot could be viewed by the Legislature as having served a useful purpose. In effect, it could be providing a temporary stopgap for coverage until a permanent and ongoing source of coverage became available to these individuals. These results would be viewed differently if these individuals are actually disenrolling primarily because the post-MRMIP coverage is not affordable to them. If this were the case, the AB 1401 pilot program might simply be taking away regular MRMIP coverage from persons who reached their 36-month time limit, and awarding coverage to other individuals who took their place on the regular MRMIP caseload. In such a case, it may be that there would be no net increase in individuals receiving access to coverage. As we indicated earlier, no definitive data on the status of post-MRMIP graduates are currently being collected.

As we discuss below, we believe further investigation is warranted to determine whether the pilot is meeting the Legislature’s intended goal of increasing access to coverage for the hard-to-insure.

In light of the findings we have discussed above, we offer several recommendations that we believe would provide the Legislature with additional information to evaluate the AB 1401 pilot projects and to improve the program by potentially reducing its costs to subscribers and the state. Figure 9 summarizes our recommendations, which are discussed in more detail below.

|

Figure 9 Options for Improving MRMIP Coverage |

|

LAO Recommendations |

|

Seek additional information regarding why some individuals have

declined |

|

Depending on survey results, explore a restructuring of the

cost-sharing |

|

— Establishing Health Savings Accounts. |

|

— Targeting premium assistance to lower-income subscribers. |

|

Encourage the participation of MRMIP and post-MRMIP enrollees in disease management services. |

Based upon our analysis, we found that a significant number of eligible individuals are not enrolling in AB 1401’s post-MRMIP coverage and that many individuals who enrolled in the program are subsequently disenrolling. However, no state entity is currently collecting the data needed to clearly determine why this is happening.

Assembly Bill 1401 directed the LAO to assess whether cost and benefits provided under the MRMIP and post-MRMIP coverage should be changed. However, absent more information on these two groups of individuals, the Legislature cannot determine whether there is a need to change the benefits or structure of post-MRMIP coverage or whether this major component of the AB 1401 pilot should continue at all after the program’s scheduled 2007 expiration date. For example, the Legislature will not know whether individuals eligible for post-MRMIP coverage decided against taking that coverage because they were able to obtain health coverage elsewhere (such as through an employer or Medicare), or because the coverage that was offered was unaffordable to them.

Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature seek additional information regarding: (1) the reasons some individuals have opted against post-MRMIP coverage and (2) how these individuals are currently receiving coverage for their health care costs.

Such information appears likely to be forthcoming. The MRMIB has indicated it plans to survey the individuals impacted by the AB 1401 pilot utilizing funding awarded by the California HealthCare Foundation. We have been advised that this survey will address a number of the information gaps we have identified in our evaluation, and that the results of this survey may be released as soon as March 2006.

If the survey finds that individuals are largely opting against or disenrolling from post-MRMIP because the rates are unaffordable, rather than because the individuals enrolled in alternative forms of coverage, the Legislature may wish to consider different approaches for addressing this problem. We offer a couple of options for the Legislature to consider below.

Assembly Bill 1401 directs our office to assess whether the cost of coverage and benefits offered under MRMIP and post-MRMIP should be changed. If the data gathered-as we have proposed above-show that there is a significant problem in the affordability of those programs for subscribers, there are other approaches the Legislature could consider to address these concerns.

For instance, the Legislature could consider the different approaches a number of other states have taken in structuring the premiums and deductibles charged to program participants in their high-risk pool programs. California’s high-risk pool programs-the coverage now provided under MRMIP and post-MRMIP-include premiums and co-payments, but do not include deductibles. As noted earlier in this report, MRMIP disenrollment survey data indicate that almost half of the MRMIP disenrollees have reported that they are leaving the program because it is not affordable. To address the concerns it may have about this trend, the Legislature may wish to consider expanding the cost-sharing requirements for MRMIP to include deductibles tied to alternative forms of coverage.

For example, as one option, the state could also offer a high-deductible plan that takes advantage of available federal tax benefits. Recent federal legislation allows individuals to establish Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) in conjunction with certain qualifying health plans which have high deductibles-at least $1,000 for individuals and $2,000 for families. Contributions and withdrawals from these accounts are not taxed when used for qualified health expenses, including direct medical services or insurance deductibles and copays, and unused funds can be carried over to the next year.

Several states have recently begun to offer HSAs as a way to reduce premium costs for the persons enrolled in their high-risk pools. Some health insurance carriers in California are already offering such health coverage in the commercial market. Our analysis of the HSA insurance rates in another state suggests that MRMIP subscribers or post-MRMIP subscribers in California could potentially benefit from such HSA arrangements. This is because the higher deductibles established under HSAs allow such health plans to charge lower premiums than would otherwise be the case. In addition, HSAs provide for tax breaks on the money set aside by persons enrolled in them to pay their out-of-pocket medical expenses.

One major policy question is how such a change would affect participation in California’s high-risk pool programs. Although a number of high-risk pools in other states have begun to offer high-deductible plans in conjunction with HSAs, we are not aware of any published evaluations indicating how they affected enrollees or the insurance market. For example, it is possible that some hard-to-insure individuals might not be interested in this option or that the tax savings from HSAs are not easily realized. Also, how health carriers in California would react to the HSA concept for this population is not known.

Accordingly, before it pursues any such change in MRMIP coverage, we recommend that the Legislature direct MRMIB to evaluate MRMIP subscribers’ interest in this alternative benefit design as well as its potential impacts on the health carriers now participating in the MRMIP and post-MRMIP coverage.

There are also alternative approaches to the cost-sharing issue besides HSAs that we believe are worth consideration by the Legislature. Specifically, the Legislature may want to consider targeting additional assistance to the lower-income subscribers in MRMIP who are most likely to find the premiums unaffordable. For example, several states assist lower-income high-risk pool subscribers with paying their premiums by reducing their premium rates or deductibles, or offering refunds of premiums. We note that, absent a change in funding for the program, providing this additional assistance to lower-income individuals would probably mean that fewer individuals could be served by the program overall. (This is because, if funding for the program remained limited, the cost of premium assistance for some individuals would probably be offset by a reduction in the cap on enrollment.) However, in years when the program is not operating at the enrollment cap, this type of assistance may enable the program to serve more individuals by holding down the rate of disenrollment from coverage.

We recommend evaluating the HSA and premium assistance options after the Legislature has reviewed the California HealthCare Foundation survey and after further monitoring of program enrollment trends. This additional information may help the Legislature to determine whether the potential changes to the program we have described above are warranted.

A number of states are incorporating disease management services into their health insurance programs to both improve the quality of care received by program beneficiaries and to reduce health care costs. These programs typically involve technical expertise in a particular disease, positive reinforcement and support from a case manager, and coordination among health care providers and the enrollee to insure that the appropriate treatment is being used.

Currently, MRMIB does not independently offer disease management to either MRMIP or post-MRMIP enrollees or promote participation in such services. The current design of these programs relies upon participating health plans to provide such services, if they choose to offer them. Our analysis indicates that a more proactive approach for connecting program enrollees to disease management services is worth considering, for two main reasons-the potential for improved quality of care as well as state savings.

First, MRMIP provides coverage to a significant number of individuals who are prime candidates for disease management services. A study of claims information conducted by MRMIB several years ago indicated that a significant portion of MRMIP enrollees had medical claims for services to treat chronic conditions such as diabetes, arthritis, and heart disease-all of which are the focus of disease management efforts in California and other states. We believe such medical practices have a significant potential to improve the quality of care for individuals with high-risk medical problems-the very population that the MRMIP and post-MRMIP programs are intended to help.

The MRMIB is currently in the process of compiling claims information that would enable the program to identify and target the most suitable candidates for disease management services. This information would allow health plans to identify the patients who are most appropriate for disease management activities.

Second, states have indicated that they have achieved significant savings through well-targeted disease management services. For instance, Colorado officials estimate that its high-risk pool was able to achieve $1.4 million in savings annually in this fashion. Oklahoma officials reported an average savings of $800 per individual in the first month of implementing a disease management program.

For these reasons, we recommend that the Legislature direct MRMIB to determine, in collaboration with the insurance carriers participating in its programs, how many of its current MRMIP and post-MRMIP enrollees are offered and actually receive disease management services.

If it were determined that a sizable segment of the enrollees who could benefit from disease management services are not actually receiving them, MRMIB should further explore what steps could be taken (such as establishing outreach and information programs) to encourage MRMIP and post-MRMIP enrollees to take advantage of such services that are available. To the extent that such services are not available, or are available only for a limited group of medical conditions, the MRMIB should further explore with insurance carriers how disease management services could be expanded to additional MRMIP and post-MRMIP enrollees.

This report was prepared by Celia Pedroza, under

the supervision of

Daniel C. Carson. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office

which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the

Legislature. To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail

subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at

www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000,

Sacramento, CA 95814.

Acknowledgments

LAO Publications

Return to LAO Home Page