January 2005

The Legislature has made protection of and access to California's 1,100 miles of coastline a statewide priority. While the California Coastal Commission has made progress toward protecting California's coastline, certain of the commission's permitting practices have temporarily reduced, and may permanently reduce, the public's access to the coast. We make a number of recommendations designed to improve the commission's progress in facilitating coastal public access.

The California Coastal Commission—created initially by a voter initiative in 1972—was permanently authorized by the California Coastal Act of 1976. The commission's primary responsibility is to protect the state's natural and scenic resources along California's coastal zone. To do this, the act authorizes the Coastal Commission to issue permits for development within the coastal zone, and to place upon these permits conditions for offsetting—or "mitigating"—the adverse effects of the permitted development. These permit conditions are intended to compensate the public for adverse impacts of new development on the state's natural resources and to ensure access to the coast.

The Coastal Commission's mitigation strategies include owners offering to dedicate portions of their property to public use as a condition of receiving a coastal development permit. These "offers to dedicate" (OTDs) are designed to provide public access to the coast or to provide open space and public trails within the coastal zone as mitigation for development. In contrast with permit conditions that require mitigation (including public access) to be provided by the permittee concurrent with development, OTDs result in a delay in the intended mitigation because they are dependent on future actions by third parties.

In the course of our review, we identified a number of shortcomings with the use of OTDs. These include:

We believe that the Legislature has the opportunity to address these shortcomings in order to encourage more timely and more appropriately financed coastal development mitigation.

In the first section of this report, we provide a brief review of the Coastal Commission's mitigation strategies and explain why the Coastal Commission uses OTDs. Secondly, we discuss the different types of OTDs and review the status of the existing OTDs. Lastly, we make recommendations on how to ensure that (1) the existing OTDs are developed and made available for public use promptly and (2) future permit requirements achieve mitigation in a timely manner without undue costs to the state.

Methodology. In reviewing the Coastal Commission's mitigation policies and practices, we interviewed a broad range of interested parties including staff of the commission, other state agencies, local governments, and federal agencies; private housing and environmental consultants; and representatives of coastal associations and the building industry. We also reviewed state documents from the commission and other state agencies, local documents, and individual case studies.

To begin with, it is important to define the scope of the Coastal Commission's involvement in coastal development mitigation. Responsibility for land use planning on the coast is highly fragmented among the Coastal Commission, cities, counties, and regional entities. The California coastal zone (which extends seaward to the state's territorial limit of three miles and extends inland anywhere from 1,000 yards to several miles) is divided into 128 geographic segments. Local governments within each segment are required to adopt Local Coastal Programs (LCPs) to ensure that development within that segment of the coastal zone complies with the California Coastal Act. However, 37 segments do not have certified LCPs.

In areas without certified LCPs, the Coastal Commission is required to issue all coastal development permits. The commission's non-permitting workload includes, but is not limited to, programs related to water quality protection, coastal energy facilities, and the expansion and protection of opportunities for public coastal access and recreation. In certified LCP areas, permits are processed and issued by the local government, and only are seen by the commission if an appeal is filed on the basis that the permitted development conflicts with the California Coastal Act.

Status of Local Coastal Programs (LCPs)The California Coastal Act requires local governments within the coastal zone to develop an LCP. The Coastal Commission is required to certify the initial LCP and review it every five years. The purposes of the certification and subsequent reviews are twofold: (1) to ensure that the LCP is being effectively implemented consistent with the provisions of the Coastal Act, and (2) to provide the commission the opportunity to make recommendations on how the LCPs can better promote the goals of the act. However, there is no requirement that a local government adopt these recommendations, leading to many jurisdictions currently without certified LCPs. There are also many overdue reviews. Figure 1 shows that only 2 percent of LCPs are certified and current in terms of statutorily required reviews, while 29 percent have yet to be certified. The remaining LCPs (69 percent) were certified at one time, but are currently overdue for review, with a vast majority of these being overdue for review by six years or more. We have previously recommended increasing incentives for local governments to incorporate the commission's recommendations for amendments into their LCPs. (Please see our December 2004 LAO Recommended Legislation, page 44, and our Analysis of the 2000-01 Budget Bill, page B-93.)

|

In areas where there is no certified LCP, the Coastal Commission is involved in regulating coastal development. It does this by using various strategies to offset (mitigate) the impacts of proposed coastal development on the state's natural resources. (Please see the box below for a definition of commonly used mitigation terms that will be used throughout this report.)

|

Common

Mitigation Definitions |

|

|

Easement |

An easement is a permanent condition placed

on a title to real property, granting a third party use of the property

for a specified purpose. Easements can be used for a variety of

purposes, such as to provide public access to a beach or protect natural

resources. For example, an easement holder could assume responsibility

for providing and maintaining a public accessway over land held in title

by another person. |

|

Local Coastal |

All local governments within the state’s coastal

zone are required to adopt plans that conform local planning and

permitting to the Coastal Act. The Coastal Commission is required to

certify and review these LCPs

every five years to ensure they comply with and promote the goals of the

Coastal Act. |

|

Mitigation |

Mitigation is a type of compensation, either to the public

at large, the environment, or a particular party (neighbor, community),

for allowing development to occur when it has an impact on one or more

of these parties. |

|

Offer to Dedicate (OTD) |

An OTD

is a condition placed on a development permit in the coastal zone as

mitigation for a particular development. The land owner “offers to

dedicate” a portion of land for various public purposes as a condition

of developing in the coastal zone. |

|

OTD Acceptance |

The OTD is accepted when the offered

property is transferred to an accepting agency who assumes

responsibility for ownership, including liability for the property, and

who may also agree to make specified improvements to the property. |

|

OTD Dedication |

The landowner dedicates an OTD on the

permit as a condition for approval. The landowner is not responsible for

finding an appropriate accepting agency for the OTD. The dedication

remains on the property deed for 21 years and if not accepted by an

appropriate agency at the end of this time, the OTD expires (is no

longer available for public transferal). |

|

OTD Opening |

The OTD is considered opened when the land

in question is made available for public use or benefit. |

|

OTD Requirement |

The commission may require an OTD from the

landowner as a condition for approval of a permit. |

|

OTD Review |

The commission reviews the OTD on the

permit and has 21 years to find a state or local agency or nonprofit

organization to accept the OTD at which time the land offered is

transferred in deed to the new owner. |

Two examples of these mitigation strategies are (1) permit requirements that require upfront mitigation and (2) those that involve OTDs. Both strategies are similar in that they require developers to agree to take certain mitigation steps as a condition of receiving a development permit. However, the strategies differ as to the timing of mitigation.

One strategy to offset the impacts of proposed coastal development is to include upfront mitigation as a permit condition. In cases where upfront mitigation is required, mitigation takes place while the permitted development is occurring. Also, the developer is financially responsible for the immediate mitigation of the development's impact, whether it be providing a public walkway, fencing, or the like. Upfront mitigation mirrors most general development planning wherein the conditions necessary for development to be permitted (sewer, sidewalk, school) are paid for or developed by the landowner before the completion of a project. Additionally, the developer is sometimes responsible for ensuring the provision of the long-term maintenance, management, and protection of the mitigation site.

Upfront mitigation can include a wide range of stipulations, from using a natural tone paint color on a structure to providing public access to the beach. As will be discussed below, courts have held that there must be a clear nexus and proportionality between these permit requirements and the adverse impacts of the development and the public purpose served by the permit requirements.

There are many benefits to including upfront mitigation as a permit condition. First, since the mitigation is completed upon conclusion of the development, there is no temporary loss of public resources or access. Another benefit is that the developer, and not the general public, funds the cost of mitigation. This follows the "beneficiary pays" principle, in that the developer, who benefits from impacting natural resources, pays the costs for mitigating those impacts.

The San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC)—a state agency with coastal development permitting authority in the San Francisco Bay Area—recently reviewed its coastal development mitigation policies. (See adjacent box.) The BCDC's review confirmed the benefits of upfront mitigation requirements.

The OTDs are quite different from the upfront mitigation requirements discussed above. Under OTDs, the permittee is offering to transfer an interest in a portion of his/her land at some point in the future (when an entity is found to accept the offer) in return for a permit to develop his/her property now. For example, if the development of a shoreline structure on the beach impedes access to the beach, the commission may require an OTD to mitigate this public access impact. The OTD could be an offer to dedicate an alternate area that would permanently be available for public use. In this situation, the alternate area would be recorded as an OTD on the property deed and the permittee would be allowed to develop the shoreline structure.

Once the OTD is recorded, the commission attempts to identify organizations to accept the OTD, a process which typically takes several years. By accepting the OTD, the accepting agency assumes responsibility for providing and maintaining the mitigation—the alternate beach access in our example. Pursuant to commission practice, the "offer" of an OTD typically remains in effect for a period of 21 years. (Even after an OTD is accepted, a number of years may pass before the OTD is developed and opened to the public.) In the meantime, the shoreline structure development is completed in our example and there is a temporary loss of access to the beach. If an OTD is not accepted by a third party within the specified time, the OTD expires, thereby resulting in a permanent loss of access to the beach for the public.

In summary, an OTD does not result in immediate mitigation. As a result, the intended beneficiaries of the OTD, such as the general public or the environment, do not receive the benefits from the mitigation until the OTD is both accepted and developed by a third party, which can take over 21 years. According to the commission, it typically takes 10 to 20 years to identify an organization to accept the OTD. Moreover, with this strategy, the developer has no obligation to develop or maintain the mitigated site.

Mitigation Policy of the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC)The BCDC, whose function is similar to the Coastal Commission, but whose jurisdiction is limited to the San Francisco Bay Area, has required mitigation for adverse environmental impacts of projects as a condition of a development permit since the early 1970s and does not employ offers to dedicate as a mitigation tool. (The Coastal Commission's geographic jurisdiction borders, but does not overlap, the BCDC's jurisdiction.) The BCDC policies state the following:

|

In addition to upfront mitigation, the commission also employs OTDs as a mitigation strategy. In this section, we discuss the commission's use of OTDs in response to court decisions and state statutory provisions that place limits on the mitigation requirements that it can impose on permittees.

Originally, the California Coastal Act allowed mitigation to be required as a permit condition for coastal development, with few guiding parameters. However, court decisions within the last 20 years have significantly limited the commission's ability to impose mitigation as a permit condition. Two United States Supreme Court decisions are particularly relevant.

Nexus Requirement. First, in 1987, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Nolan v. Coastal Commission that the requirement to mitigate development as a permit condition is an unconstitutional "taking" of private property unless there is a clear nexus between the development's adverse impact and the required mitigation of that development. For example, if a property owner proposes to build a three-story building that restricts the public's view of the coast, the permit condition must directly relate to mitigating the loss of the public's view of the coast. This test represents the first criterion that must be met when mitigation is a required permit condition.

Proportionality Requirement. Secondly, in 1994, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Dolan v. City of Tigard that the nature and extent of development permit conditions must be roughly proportional to the adverse impact of the development. Mitigation requirements as permit conditions must satisfy this test as well as the nexus requirement to be legally valid.

In addition to these court decisions, the California Coastal Act restricts the commission's ability to require that a permittee provide public access-related mitigation. Specifically, the act provides that an accessway shall not be required to be opened to public use until a public agency or a private association agrees to accept responsibility for maintenance and liability of the accessway. (The right granted to the third party to use the property that is held in title by another—such as to provide and maintain an accessway—is referred to as an "easement.") Accordingly, the commission can only require upfront, public access mitigation as a permit condition if at the time of permitting an organization (referred to as the "easement holder") is found to accept responsibility for the maintenance and liability of the accessway. Since current law does not authorize the commission itself to hold interest in land, it cannot be the public agency to accept responsibility for these easements. Therefore, the commission must search for an entity to accept responsibility for the easement at the time of permitting, which according to the commission is very difficult and resource intensive.

As indicated by the commission, this provision of the act protects the due process rights of the permittee. According to the commission, due process rights would be violated if the government agency imposed a condition that is beyond the control of the permittee. Such a condition, for example, would include a requirement on a permittee (as a permit condition) to find someone upfront to assume responsibility for maintenance and liability of a public accessway.

As just discussed, there are legal and statutory limitations on imposing mitigation as a permit condition for coastal development. For this reason, the commission developed the OTD as an alternative mitigation tool to address many of these constraints.

The design of the OTD is consistent with the Coastal Act's provision which protects

due process, because it transfers the

responsibility for finding a third party to accept

responsibility for maintenance and liability of the

easement from the permittee to the commission or another public agency. Therefore, the

permit condition is not beyond the control of

the permittee and the due process requirement is met. This is important because at least

50 percent of the commission's permittees are single-family homeowners, who would find

it difficult to locate a third party to be

responsible for maintenance and liability of the easement.

In contrast, a majority of BCDC's permittees are large businesses, such as hotels. These

organizations often volunteer to be responsible for

the maintenance and liability of a public

accessway because they financially benefit from

maintaining the accessway for their customers.

Second, as mentioned earlier, nexus and proportionality requirements must be met in requiring mitigation as a permit condition. However, these legal requirements can be avoided in those cases where permittees volunteer to offer to dedicate portions of their property for public access. In such instances, an OTD can be recorded as a permit condition and future mitigation is possible. Recording an OTD as a permit condition provides at least the potential benefit of coastal development mitigation. Without the use of this strategy, potential future mitigation may be lost to the state.

With this understanding of why the Coastal Commission uses the OTD as a mitigation tool, we now turn to a discussion of the different types of OTDs used by the commission, the status of these OTDs, and the extent to which the use of OTDs has resulted in actual mitigation.

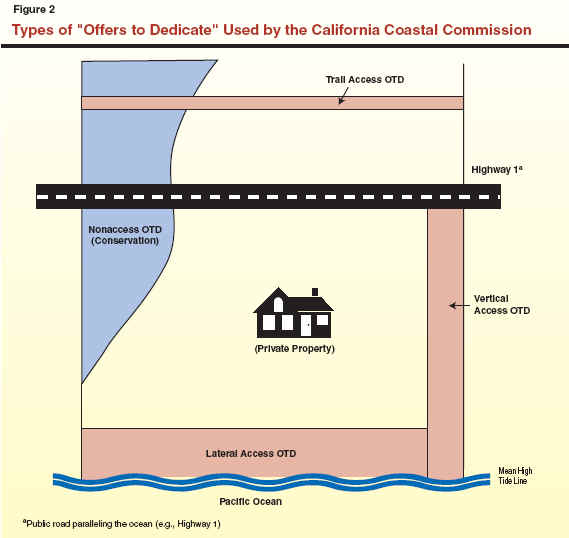

There are two major categories of OTDs used by the commission: access and nonaccess. Access OTDs provide access within the coastal zone—usually directly to the ocean. These OTDs are identified by their relationship to the ocean: "lateral" OTDs are parallel to the ocean; "vertical" OTDs are perpendicular to the ocean; and "trail" OTDs provide recreation access within the coastal zone. The second broad category of OTDs are nonaccess (mainly conservation) dedications. These are generally conservation areas or environmentally important areas where public access is not the primary goal of the mitigation. Figure 2 shows how these different types of OTDs might look on a single parcel of land. We discuss each of these two broad categories of OTDs in further detail below.

As shown in Figure 3, over 1,400 access OTDs are known to have been attached to permits issued by the commission. Figure 3 shows the status of these OTDs, broken down by type.

As shown in Figure 3, lateral OTDs are the most prevalent type of access OTD. Of

the 1,089 lateral OTDs, about

79 percent have been accepted, 20 percent remain outstanding offers, and less than

1 percent have expired to date. These lateral OTDs are usually a strip of land parallel to

the ocean above the mean high tide line. Lateral OTDs are the least expensive

OTD,

usually requiring little development or long-term

maintenance. Costs to develop a lateral OTD

typically range from essentially nothing to around $10,000. Agencies who have accepted

lateral OTDs include the State Lands Commission

and local governments.

|

Figure 3 Status of Access OTDs |

|

|

OTDs Recorded From 1977 Through July 2004 |

|

|

Access OTDs—by Status of Offer |

|

|

Offer not yet accepted |

379 |

|

Offer accepted |

1,049 |

|

Expired |

19 |

|

Total |

1,447 |

|

Access OTDs—by Type |

|

|

Laterals |

|

|

Offer not yet accepted |

223 |

|

Offers accepted |

858 |

|

Expired |

8 |

|

Subtotal |

(1,089) |

|

Verticals |

|

|

Offer not yet accepted |

38 |

|

Offer accepted |

101 |

|

Expired |

3 |

|

Subtotal |

(142) |

|

Trails |

|

|

Offer not yet accepted |

108 |

|

Offer accepted |

39 |

|

Expired |

8 |

|

Subtotal |

(155) |

|

Others |

|

|

Offer not yet accepted |

10 |

|

Offer accepted |

51 |

|

Expired |

0 |

|

Subtotal |

(61) |

|

Total |

1,447 |

Of the 142 vertical OTDs, about 71 percent have been accepted, 27 percent remain outstanding, and 2 percent have expired to date. Since vertical OTDs usually require engineered staircases and trails to be developed and are often susceptible to damage from wind and rain, these OTDs are usually of the more expensive type of OTD for the accepting agency. Costs to develop a vertical OTD typically range from about $8,000 to $50,000. The types of agencies who have accepted and developed these offers include nonprofits, local governments, and the State Coastal Conservancy. Many of the vertical OTDs have been jointly developed or operated.

Trail and "other" OTDs make up the rest

of the access OTDs. (Other OTDs include vista points and automobile pullout points.)

These OTDs may not provide direct access to the coast but may parallel the coast, provide

scenic views, or complement an existing accessway. Costs associated with these OTDs can

include costs to develop the trail, for maintenance,

and for liability insurance. Costs to develop

trail OTDs typically range from about $10,000 to

$200,000. One hundred fifty-five trail OTDs have been offered, with about 70 percent

not yet accepted, 25 percent accepted, and

5 percent expired. Sixty-one other OTDs have been offered, with 84 percent accepted,

16 percent not yet accepted, and none expired.

The commission uses nonaccess OTDs as a mitigation option for projects where traditional "access" is not a feasible mitigation alternative. These nonaccess OTDs generally concern conservation areas or environmentally important areas where public access is not the primary goal of the mitigation. For example, a nonaccess OTD might include land offered for habitat, open space, or agricultural protection, or involve a permanent retirement of land from development. Costs to develop nonaccess OTDs typically range from about $10,000 to $50,000. Figure 4 describes the status of nonaccess OTDs to the extent that they have been tracked. As shown, the status of over 200 nonaccess OTDs is unknown. According to the commission, the incomplete tracking of nonaccess OTDs has been due to personnel and budget constraints. However, the commission is currently making an effort to track the status of all nonaccess OTDs.

|

Figure 4 Status of Nonaccess |

|

|

OTDs Recorded From 1977 Through June 2004 |

|

|

Nonaccess (Conservation) OTDs— |

|

|

Offer not yet accepted |

797 |

|

Offer accepted |

232 |

|

Expired |

54 |

|

Unknown status |

233 |

|

Total |

1,316 |

As indicated in Figures 3 and 4, over 40 percent of all OTDs recorded and tracked by the commission have not yet been accepted. (In addition, potentially a significant portion of the nonaccess OTDs with unknown status might also be outstanding.) Furthermore, a significant number of these OTDs will expire within the next few years (meaning that the "offer" has remained outstanding for 21 years). Almost 30 percent of the OTDs that have not yet been accepted are scheduled to expire in the next four years. In 2004 alone, over 95 OTDs are scheduled to expire, followed by roughly 80 expirations a year in the succeeding three years.

Several issues arise from our investigation of the commission's policies and practices related to OTDs. These issues can be grouped into two categories. The first set of issues concerns the existing "stock" of OTDs—that is, what can be done to ensure timely acceptance, development, and opening of the existing OTDs that have been recorded in the past and that remain unaccepted? The second set of issues looks prospectively at the future use of coastal development mitigation tools, including OTDs—that is, how can the state ensure that future permit requirements achieve mitigation in a timely manner and are appropriately funded?

As Figures 3 and 4 indicate, there are over a thousand OTDs that have not been accepted and are thus currently unavailable for public use or benefit. In this section we discuss the state's challenges in making these OTDs available for public use or benefit and make recommendations to refocus the commission's work to provide a more effective approach to address these existing OTDs.

The commission has recently made an effort to improve its tracking of OTDs, particularly access OTDs. However, as Figure 4 reveals, the commission cannot currently identify the status of 17 percent of nonaccess OTDs. Without tracking the status of these OTDs, it is likely that the potential mitigation to be achieved from these properties will be either lost forever, or at least delayed significantly.

All OTDs should have been reported at some point to a number of state agencies (the Department of Parks and Recreation, the State Coastal Conservancy, and the State Lands Commission) pursuant to a long-standing statutory requirement in the Coastal Act. Therefore, a log should exist that would facilitate the tracking of OTDs by informing the commission of the universe of OTDs to be tracked.

Improve Tracking and Reporting of OTDs. We recommend that the Coastal Commission make the tracking of all existing OTDs a high priority. While the commission appears to be moving in this direction, we think that it is also important that the information gleaned from the tracking effort be compiled and conveyed to the Legislature. This information will enable the Legislature to evaluate how well the Coastal Act's objectives are being met through OTDs. Additionally, such information will allow the Legislature to determine future funding requirements connected with OTDs. (We discuss this funding issue in the next section.)

Therefore, we recommend that the Legislature direct the commission to report to the Legislature by January 1, 2006, on the status, location, and expiration date of all outstanding OTDs, including those nonaccess OTDs not currently being tracked. Should the commission lack sufficient funding for this tracking and reporting workload, the Legislature might consider revising the distribution of the revenues from the Whale Tail License Plate (see box next page) by permitting a portion of these funds to be used for coastal development mitigation-related activities.

According to the commission, the entire process from the conditioning of a coastal development permit with an OTD to the date an OTD is accepted can take anywhere from several weeks to 21 years. In addition, the actual development and opening of the OTD to the public may take several more years beyond the acceptance date. This means that from the date the commission first permits the coastal development, whether it is an addition to a house or a large commercial development, to the date the accepting agency makes the OTD usable, it can take over one generation before the mitigation-related benefits begin to be realized by the public. As mentioned earlier, almost 30 percent of the outstanding OTDs are scheduled to expire within the next four years.

An important step toward reducing the amount of time it takes before the public can benefit from OTDs is to speed up the acceptance process of OTDs. Accepting entities vary by region, but generally are state or local agencies; in certain areas, established nonprofits step in to accept expiring OTDs. Those OTDs accepted by state agencies generally have been accepted by the State Lands Commission (SLC) in areas where SLC has primary jurisdiction (certain beaches and waterfronts) and the State Coastal Conservancy (SCC). Recently enacted legislation (Chapter 518, Statutes of 2002 [SB 1962, Polanco]), declares the state's intent to accept expiring access OTDs in order to prevent the potential loss of public accessways to and along the state's coastline. Specifically, under this legislation, SCC must accept all public access OTDs within 90 days of their expiration and open at least three public accessways every year. (Subsequent legislation conditioned the latter requirement to open accessways on funding availability.) According to SCC, it accepted 12 OTDs in 2003 and 7 OTDs as of May 2004 to prevent OTDs from expiring.

The Whale Tail License Plate: Potential Source of Additional FundingThe Whale Tail License Plate was established in 1994 by Chapter 558, Statutes of 1994 (SB 1411, Mello). Revenues from the issuance, renewal, and transfer of these plates, less administrative costs of the Department of Motor Vehicles and exclusive of additional fees for such things as personalization (which are deposited into the Environmental License Plate Fund [ELPF]), are split equally between the California Beach and Coastal Enhancement Account (CBCEA)—an account within the ELPF—and the ELPF. Funds in the CBCEA are allocated according to statute to support the Coastal Commission's Adopt-A-Beach Program, Coastal Cleanup Day, coastal marine education and to the Coastal Conservancy for general program use. Funds deposited directly in the ELPF from the Whale Tail License Plate can be used for a broad range of environmental purposes, and have been allocated to several departments including the Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and the Baldwin Hills Conservancy. From March 2003 through February 2004, approximately $3 million was deposited in the ELPF and $1.3 million was deposited into the CBCEA from sale and personalization of the Whale Tail License Plate. The Legislature may wish to consider specifying conditions on how the Whale Tail License Plate funds deposited into the ELPF are allocated. For example, a portion of these funds could be used to improve tracking of OTDs or for the maintenance and operations of public accessways and nonaccess mitigation projects. The use of a portion of the Whale Tail License Plate funds for coastal development mitigation-related activities would be consistent with the broadly stated eligible uses of ELPF funds. |

Require Development of Plan to Further Acceptance and Opening of OTDs. We recommend the enactment of legislation directing the commission, in conjunction with the SLC and SCC, to develop a plan to be submitted to the Legislature to facilitate the acceptance, development, and opening of all outstanding OTDs within a specified timeframe to be determined in consultation with the commission and other state agencies.

We recognize that the development and implementation of such a plan could have cost implications for both the administering state agencies (for example, costs to determine the status of OTDs and locate the entities to accept them) and the agencies accepting the OTDs (which could be a state or local agency or a nonprofit organization). As discussed previously, the costs to develop and maintain an OTD typically have varied from essentially nothing to $200,000. Accordingly, the plan should identify (1) the costs to meet the plan's objective, specifically identifying the costs that would likely be borne by the state (for example, the administrative costs to accept or find accepting agencies for the over 300 OTDs that will expire in the next five years), (2) potential state funding sources (such as Whale Tail License Plate funds), and (3) organizations that could potentially assume the long-term management of the OTDs. For example, if there are several OTD properties in relatively close proximity to an existing local public park or beach, these might be appropriate for transfer to and long-term maintenance by a local government, should it be willing.

Consider Requiring State Agency to Accept Expiring Nonaccess OTDs. Lastly, similar to how SB 1962 is preventing public access OTDs from expiring and being lost to the public for future use, the Legislature may wish to consider enacting similar legislation for the nonaccess OTDs. Such legislation could require a state agency—such as SLC or the Wildlife Conservation Board—to accept nonaccess OTDs that are about to expire.

It should be noted that while there are no direct costs when an OTD is accepted, the acceptance of outstanding OTDs (most of which expire in the next five years) will create some administrative costs in the short term for the accepting agencies. Specifically, according to SCC, accepting an OTD requires review of the easement documentation by program and legal staff and the completion of a "Certificate of Acceptance."

In the previous section, we made recommendations to remedy the backlog of existing OTDs that are waiting to be accepted and opened to the public. In this section, we discuss the commission's future use of coastal development mitigation strategies. Specifically, our recommendations focus on encouraging more upfront mitigation of coastal development, finding a more appropriate funding source for mitigation, and shortening the timeframes for acceptance and opening of OTDs.

Before discussing our recommendations for the future of coastal development mitigation, it is important to point out two factors that we believe will limit the number of permittees who will be affected by these recommendations. As mentioned earlier, the court decisions that established nexus and proportionality tests for mitigation requirements have dramatically reduced the ability of the commission to require mitigation (whether upfront mitigation or OTDs) as a condition of a coastal development permit. For example, the number of OTDs recorded as permit conditions in 1985 (before the nexus and proportionality court decisions), was about 100 and the number of OTDs recorded as permit conditions in 2003 (after the court decisions) was less than 10. Additionally, as more LCPs are certified, the state's involvement in coastal development mitigation will decrease as local jurisdictions become responsible for approving coastal development permits and prescribing mitigation. Accordingly, the universe of future permittees that would be affected by our recommendations over time would likely be relatively small.

We also note that our recommendations—with the overall goal of providing more complete and timely mitigation of coastal development—can be achieved with minor additional administrative costs to state agencies.

As discussed earlier, when upfront mitigation is a permit condition, the mitigation is completed upon conclusion of the project. Consequently, there is no loss to the public of natural resources. In contrast, when an OTD is a permit condition, mitigation is not completed until an entity accepts the OTD and completes the mitigation, which can take over 21 years. Additionally, in cases where the OTD is not tracked or is not a public access OTD, the OTD may expire and be permanently lost to the public.

Require State Agency to Accept Responsibility for Accessway Maintenance and Liability in Specified Circumstances. As discussed earlier, there are a number of legal parameters that constrain the ability of the commission to require upfront mitigation as a permit condition. Specifically, these parameters include the California Coastal Act provision that an accessway shall not be required to be opened to public use until a public agency or a private association agrees to accept responsibility for maintenance and liability of the accessway. As a result of this legal constraint, the OTD was developed as a mitigation alternative. However, we think that there is a way to facilitate more upfront mitigation, while living within these legal parameters.

Specifically, we recommend the enactment of legislation that would require SCC to accept responsibility for maintenance and liability for public accessways that are required as a condition of future commission permits, but only if certain circumstances apply. These circumstances apply to a very limited number of cases and would be instances where (1) the permittee can be legally required to develop the accessway upfront upon completion of the permitted development, (2) the permit requirements provide that a third party should assume the management and liability-related responsibilities for the accessway, and (3) at the time of permitting, no other third party has been found to accept these management and liability responsibilities. With the enactment of such legislation, the commission should nonetheless be encouraged to continue to seek out local governments and other regional nonstate entities' involvement in accepting responsibility for these easements.

Since SCC is already involved in the acceptance of OTDs pursuant to SB 1962, we think that the conservancy is an appropriate entity to assume these responsibilities. Because SCC does not have regional offices and is not a property management organization, in assuming these responsibilities it would practically serve more of an intermediary role by accepting the easement until it finds another entity to accept ongoing responsibility for the easement.

In summary, we think that this statutory change would ensure more timely development of public accessways to the coast to the extent that it facilitates such access being provided upon completion of the development project, rather than at some uncertain time potentially many years in the future.

Permittees Currently May Be Absolved From Fiscal Responsibility of Mitigation. As discussed previously, upfront mitigation by the permittee is not always a feasible mitigation alternative. For example, there are situations in which a project's mitigation may be part of a regional trail that should be developed concurrently with other sites. In such instances, OTDs are appropriate permit conditions because it is appropriate for mitigation to be completed (developed) in the future. However, under the current implementation of OTDs, the permittee is absolved from any fiscal responsibility in developing the mitigation. Similarly, when mitigation involves easements (in the case of both OTDs and upfront mitigation), it is the accepting agency (easement holder), rather than permittees, that is responsible for the operational costs associated with maintaining the easement.

Require Permittee to Fund Future Mitigation Development When OTD Is Permit Condition. In situations in which upfront mitigation is not feasible as a permit condition and instead an OTD is recorded, we think that the permittee should nevertheless be required to fully fund the capital costs to develop the project-specific mitigation in the future. We would note that the requirement to fund these capital costs would have to meet the legal parameters of nexus and proportionality. Since the permittee benefits from the development that is permitted, it is appropriate that the permittee be financially responsible for mitigating the effects of this development, even if the timing of the mitigation is delayed. We also note that impact fees to cover public agency costs related to the mitigation of development are common at the local level. We therefore recommend the enactment of legislation to require, as a permit condition, the upfront assessment of an impact fee to cover these future capital costs when an OTD is recorded.

Increase Existing Development Permit Fees to Fund Ongoing Operational Costs Associated With Easements. Additionally, in a previous analysis (please see our Analysis of the 2004-05 Budget Bill, page B-57), we found that the commission's existing coastal development permit fees are very modest and offset less than 10 percent of the costs of the commission's permitting and enforcement program. Our review found that these fees have not been raised since 1991, and that the fees are set at levels far below the fees assessed by local permitting agencies for comparable development projects. Since the permittees directly benefit from the permitting program, we recommended that fees be increased to better reflect this benefit and create General Fund savings.

If the Legislature increases development permit fees, it could direct a portion of the increased fees into a special fund to offset the cost of the operations and maintenance of easements connected with coastal development mitigation, including access and nonaccess OTDs. (Current development permit fees are deposited into the Coastal Access Account per Chapter 782, Statutes of 1997 [SB 72, McPherson], and are available to SCC for the operations and maintenance of public accessways.) Our discussions with commission and conservancy staff indicate that a dedicated funding source for the maintenance and operations of easements (including OTD properties) is critical to finding local government agencies and nonprofits to accept and operate them.

The timeframe in which an OTD must be accepted is not specified in current law, but rather a timeframe has been set administratively by the commission. The commission generally provides for 21 years from the date an OTD is recorded for the commission to search for an organization to accept the OTD before it expires. During this time, the OTD is unavailable for public use.

Shorten OTD Acceptance Timeframe. We recommend the enactment of legislation that specifies the timeframe in which an OTD must be accepted and shortens the timeframe from the commission's current practice. Generally, we believe a maximum of ten years is appropriate for the commission to find an organization to accept responsibility for an OTD. By shortening this timeframe, the commission will be encouraged to find an accepting entity in a timelier manner such that the OTD would be available for public use in a shorter timeframe.

It should be noted again that the costs associated with accepting an OTD are essentially administrative in nature, and should not be substantial.

Similarly, under current law, the entity accepting an OTD is not required to develop the property and open it to public use or benefit in a specified timeframe. This has led to some access OTDs taking over ten years from the date of acceptance to be opened. While the commission does enter into agreements with accepting entities specifying matters such as timelines to open the OTD property, the commission lacks the statutory authority to require and effectively enforce that the OTDs be made usable within a given time.

Require Accepted OTDs to Be Developed Within Specified Time. We therefore recommend the enactment of legislation to generally require any OTDs accepted in the future to begin development within one year of acceptance, and to be completed within three years of the start of development. We think that these timeframes to develop an OTD are reasonable benchmarks in light of the nature and extent of development required for most OTDs (provided there is no litigation delaying the development of the OTD). With the enactment of an impact fee as recommended above, accepting entities would have sufficient funding to open OTDs and make them available to public use (in cases where the impact fee is levied).

Although the OTD is an innovative strategy that provides the potential for future mitigation of coastal development, we find that the implementation of this strategy can be improved to provide more timely and more appropriately financed coastal mitigation. Specifically, we recommend that the commission make tracking of OTDs a high priority and be required to develop a plan to expedite the acceptance and opening of backlogged OTDs. We recommend that legislation specify the timeframes to accept and open OTDs for public use. We also recommend the enactment of legislation to (1) require the assessment of new impact fees on permittees to cover the costs to develop and open an OTD property after acceptance of the OTD and (2) increase existing development permit fees to support the operational costs of developed and opened OTD properties that are assumed by the state or other third parties.

Furthermore, we find that the commission should encourage more upfront mitigation and rely less on the use of the OTD, provided that legal parameters governing permissible mitigation requirements continue to be followed. To facilitate this, we recommend the enactment of legislation to require SCC to accept responsibility for accessway maintenance and liability under specified circumstances where this will allow the mitigation to proceed at the time of permitting.

| Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by Michelle Baass, based in part on research done by Catherine Freeman, and reviewed by Mark Newton. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |