California's wildland fire protection system involves multiple levels of government, requires significant levels of personnel and equipment, and relies on a complex series of interagency agreements. This primer is intended to assist the Legislature in understanding how wildland fire protection services are delivered and the major cost drivers affecting spending. We also make recommendations for increasing legislative oversight of state expenditures for wildland fire protection and for reducing these expenditures.

Wildland fires are those fires that occur on lands with natural vegetation such as forest, brush, and grass. While such fires can have a beneficial effect on the natural environment, they also can be costly and destructive. Wildland fires can risk lives and property, and compromise watersheds, wildlife habitat, recreational opportunities, and local economies. Wildland fires occur in both sparsely populated and developed areas. As development continues to increase in areas with high wildfire risks, California is faced with the challenge of controlling the costs of wildland fires while reducing the losses from such fires.

Who is responsible for wildland fire protection? How are wildland fire protection services delivered in California? What factors are causing wildland fire protection expenditures to increase? What can be done to reduce the state's costs of wildland fire protection and increase legislative oversight of these expenditures? The purpose of this primer is to address these and other wildfire-related issues in order to aid policymakers and other interested parties in their deliberations and decision making.

This primer on California's wildland fire protection system is organized into the following sections: (1) the statutory responsibilities of state, federal, and local agencies; (2) the wildland firefighting resources of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CDFFP); (3) the multiagency agreements that are used to coordinate and deliver services for wildfire protection; (4) CDFFP's expenditures and funding for wildland fire protection; and (5) the factors that drive the state's fire protection costs. This primer also includes recommendations for increasing legislative oversight of state expenditures for wildland fire protection and for reducing these expenditures.

We have included a glossary at the end of this report with definitions of commonly used wildland fire terms.

Fire protection efforts in California's wildlands involve firefighting resources at the state, federal, and local levels. The responsibilities for each level of government are set forth in law and policy directives. However, these responsibilities and the geographic areas of protection often overlap among governments. In order to reduce overlap and maximize the use of resources across jurisdictions, firefighting agencies generally rely on a complex series of agreements which result in a multiagency wildland fire protection system. Even under this multiagency approach, responsibilities are not always clear, particularly as they relate to life and structure fire protection in wildland areas.

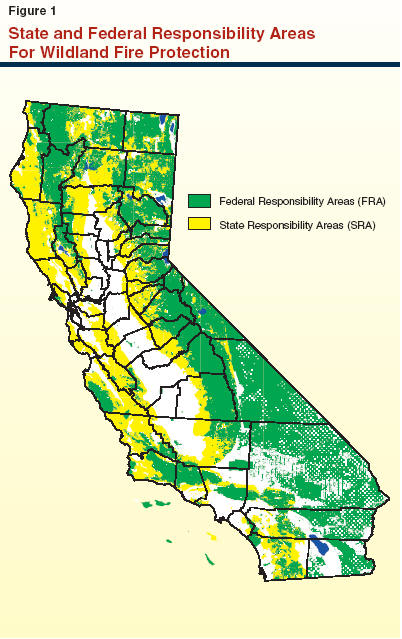

As shown in Figure 1, California encompasses approximately 101 million total acres (all types of lands). This total includes 79 million acres of wildlands for which the state or federal agencies are primarily responsible for providing wildland fire protection. Specifically, the state is responsible for wildland fire protection on approximately 31 million acres of wildlands (generally privately owned) and federal agencies are responsible for wildland fire protection on approximately 48 million acres of federally owned wildlands. (As will be discussed later, while the protection of people and structures within wildlands is generally provided by local governments, the responsibilities for providing such protection are not clearly established in statute.) The balance of the state consists of both developed and relatively rural lands (generally not wildlands) for which fire protection services are generally provided by local jurisdictions. Fire protection by local jurisdictions in these areas is mostly focused on structure and medical response.

As shown in Figure 2 and discussed below, multiple federal, state, and local agencies each have various roles in providing fire protection in wildlands.

|

Figure 2 Federal, State, and

Local Fire Protection Roles |

|

|

Agency |

|

|

State |

|

|

California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CDFFP) |

Provides fire protection in “state responsibility areas” (SRAs) which consist mostly of privately owned forestlands, watershed, and rangelands. |

|

Office of Emergency Services (OES) |

Coordinates overall state agency response to major disasters. In large fires, OES coordinates the exchange of resources among local, state, and federal agencies. The OES is also the “pass-through” agency for federal disaster assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). |

|

California Department of the Youth Authority |

Provides about 30 crews (approximately 600 people) under the direction of CDFFP. |

|

California Department of Corrections |

Provides about 160 crews (approximately 3,200 people) under the direction of CDFFP. |

|

Federal |

|

|

United States Forest Service |

Responsible for land management and fire protection for lands under the agencies’ jurisdiction. |

|

Bureau of Land Management |

|

|

National Park Service |

|

|

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |

|

|

U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs |

|

|

U.S. Department of Defense |

|

|

FEMA |

Although not a wildland fire protection provider, manages disaster relief efforts and provides federal funding for fires declared disasters. |

|

Local |

|

|

Counties, cities, and fire districts |

Responsible primarily for protection of homes and other structures in wildlands. |

The CDFFP is the lead state agency for wildland fire protection on "state responsibility areas" (SRA). The SRA consist mostly of privately owned forestlands, watersheds, and rangelands. Less than 1 percent of SRA acres are publicly owned lands. Land within city boundaries and federally owned lands are excluded from SRA.

The SRA lands are designated as such by the Board of Forestry (BOF) and are covered wholly or in part by timber, brush, or other vegetation that serves a commercial purpose (such as ranching or timber harvesting) or that serves a natural resource value (such as watershed protection). There can be several different types of property owners in SRA, such as timber operators, ranchers, and owners of individual residences. Although these lands may have structures on them, when housing density reaches more than three units per acre, the BOF generally removes those lands from SRA. These SRA designations are reviewed every five years, with the next review scheduled for this year.

As shown in Figure 3, SRA lands are found in every county except San Francisco and Sutter Counties.

|

Figure 3 State Responsibility Areas (SRA), by County |

|||

|

(Acres in Thousands) |

|||

|

County |

Acres |

County |

Acres |

|

Alameda |

250.9 |

Orange |

120.6 |

|

Alpine |

38.2 |

Placer |

384.4 |

|

Amador |

291.4 |

Plumas |

428.8 |

|

Butte |

525.1 |

Riverside |

712.5 |

|

Calaveras |

526.7 |

Sacramento |

118.6 |

|

Colusa |

257.2 |

San Benito |

728.9 |

|

Contra Costa |

200.7 |

San Bernardino |

358.3 |

|

Del Norte |

190.2 |

San Diego |

1,186.6 |

|

El Dorado |

564.6 |

San Francisco |

— |

|

Fresno |

763.5 |

San Joaquin |

160.5 |

|

Glenn |

32.5 |

San Luis Obispo |

1,497.4 |

|

Humboldt |

1,583.5 |

San Mateo |

180.2 |

|

Imperial |

2.2 |

Santa Barbara |

736.9 |

|

Inyo |

218.6 |

Santa Cruz |

234.7 |

|

Kern |

1,764.5 |

Santa Clara |

1,355.9 |

|

Kings |

97.3 |

Shasta |

86.9 |

|

Lake |

391.1 |

Sierra |

794.8 |

|

Lassen |

1,028.2 |

Siskiyou |

1,355.9 |

|

Los Angeles |

515.8 |

Solano |

86.9 |

|

Madera |

373.0 |

Sonoma |

794.8 |

|

Marin |

199.9 |

Stanislaus |

449.3 |

|

Mariposa |

442.9 |

Sutter |

— |

|

Mendocino |

1,874.8 |

Tehama |

1,276.6 |

|

Merced |

422.6 |

Trinity |

478.9 |

|

Modoc |

628.6 |

Tulare |

603.0 |

|

Mono |

198.1 |

Tuolumne |

356.1 |

|

Monterey |

1,285.1 |

Ventura |

352.0 |

|

Napa |

369.6 |

Yolo |

175.3 |

|

Nevada |

386.9 |

Yuba |

213.7 |

|

Total |

|

|

30,783.0 |

Although CDFFP is responsible for wildland fire protection in SRA, its responsibility for life and structure protection in such areas is less definitive. Specifically, CDFFP is authorized, but not required, under current law to provide day-to-day emergency services—such as structure protection and medical assistance—in SRA when resources are available and when it is within its budget. Additionally, BOF has issued policy direction which emphasizes the importance of CDFFP responding to structure fires when there is a threat to wildlands.

The CDFFP's overall strategy for fire protection is to provide an immediate response to fires and limit all fires to ten acres or less rather than allowing fires to run their course. This suppression policy is intended to reduce the occurrence of larger, more costly fires and to facilitate the protection of private property.

Local Roles Within SRA. Structures, including residences, are found on some parts of SRA. While state law does not require local governments to provide fire protection within SRA, in practice local governments have generally assumed the responsibility for providing structure protection and basic medical assistance in SRA. In fact, about 70 percent of SRA are covered by some form of local fire protection focused on structure protection and medical response. (The state's fire protection services are focused on protecting the wildlands.) These local services are generally funded from property tax revenues or from special assessments. The current provision of structure and medical response services by local governments is consistent with historical practice as well as BOF policy that life and structure fire protection within SRA is the responsibility of private citizens and local governments.

Our review finds that as the number of structures in and adjacent to wildland areas continues to grow, costs for structure protection in connection with wildland fires have increased significantly. This has prompted calls for greater clarification of the respective roles of the various levels of government in providing such structure protection.

Lands owned and administered by various federal agencies comprise Federal Responsibility Areas (FRA). There are approximately 48 million acres of FRA in California. The United States Forest Service (USFS) is the federal agency with the single largest holdings of wildlands. However, FRA also include lands held by the Bureau of Land Management, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Department of Defense, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. Although not a provider of fire protection services, the Federal Emergency Management Agency plays an important role in certain cases in providing financial assistance related to wildland fires. This includes reimbursements to state and local governments for costs associated with wildland fires and payments to individuals for losses from federally declared disasters.

The federal agencies vary in their approaches to wildland firefighting. For example, some agencies may follow a policy of containing fires when they are small. Other federal land managers may elect to permit fires to burn unchecked to improve or maintain resource values. With regard to life and structure fire protection, recent federal policies have stated that structural fire protection in wildland areas is the responsibility of the state and local governments.

In practice, the wildland fire protection system is built upon the premise that agencies will respond to incidents beyond their jurisdictions in order to maximize the use of firefighting resources and ensure the closest available resources respond. The delivery and use of these resources across jurisdictions are guided by a series of interagency agreements, as discussed below.

Although state, local, and federal agencies each have unique responsibilities for wildland fire protection, the actual delivery of wildland fire protection services in California relies on an integrated multiagency effort to maximize the use of firefighting resources. This integration is essential in order to avoid duplication of firefighting resources and to allow the closest available resources to respond to a fire, regardless of jurisdiction. This integration is authorized by statute and is guided by interagency agreements under which CDFFP provides services to local and/or federal agencies, and vice versa. These agreements that allow for the rendering of services by one jurisdiction to the benefit of another jurisdiction are typically referred to as "mutual aid" agreements.

The four main categories of mutual aid agreements are listed in Figure 4 and are discussed in detail below. The most prominent of these agreements have tended to be those which allow for services to be rendered to another jurisdiction without reimbursement and those under which local agencies reimburse CDFFP for services.

|

Figure 4 Four Main Categories

of |

|

|

|

� Services Provided to Other Jurisdictions Without Reimbursement |

|

� State and Federal Agencies Reimburse Local Agencies for Services |

|

� Local Agencies Reimburse CDFFP for Services |

|

� State and Federal Interagency Cooperation: Exchange of Responsibility |

Mutual aid agreements can be negotiated at a statewide level as well as at the local level. The CDFFP participates in about ten mutual aid agreements negotiated at a statewide level and hundreds of agreements negotiated between local CDFFP offices and local governments. The specific type of services that are provided and the reimbursement levels vary by agreement.

CDFFP's Wildland Firefighting ResourcesWe discuss below CDFFP's staffing, facility, and equipment resources for wildland fire protection. Personnel. As of March 2005, CDFFP's fire protection program included about 2,000 state-funded permanent staff, including fire professionals directly involved in firefighting efforts as well as support positions. Fire professionals include positions such as firefighters, fire apparatus engineers, and fire captains. The CDFFP also employs about 740 state-funded seasonal firefighters. In addition, there are another 1,700 permanent state positions that are funded by local governments for services provided by CDFFP on behalf of these governments. For large wildland fires, CDFFP uses Department of Corrections inmate crews, in conjunction with its own personnel. These crews are on the "front line" of a fire and generally consist of 12 to 17 people per crew and one fire captain. Facilities Throughout the State. The CDFFP is divided into two regions with 21 administrative ranger units statewide. As shown in Figure 5, within these ranger units, CDFFP operates 229 state-funded forest fire stations. These stations are generally operated on a seasonal basis. There are another 410 local government-funded stations operated by the state (not shown on map). The CDFFP also operates 41 conservation camps that house about 198 inmate fire crews spread throughout the state. Figure 5 shows the location of state-funded fire stations and conservation camps.

Equipment. The CDFFP owns and operates about 336 wildland fire engines. Each fire engine holds 500 gallons of water, carries crews of three to four people, and are designed to travel off-road. In addition, CDFFP operates another 700 engines under contract with local agencies. From the air, CDFFP operates 23 airtankers, 11 helicopters, and 14 air attack planes which direct the airtankers and helicopters to critical areas of the fire. The CDFFP also has other equipment such as bulldozers and mobile telecommunications centers. All of this equipment is owned by the state. During large fire sieges, CDFFP often rents additional equipment. The 2005-06 Governor's Budget also includes an augmentation of $10.8 million for the purchase of fire apparatus and helicopters. In our Analysis of the 2005-06 Budget Bill (see page B-52), we discuss this proposal and raise concerns about the lack of details supporting it. |

In the course of wildland fire protection service delivery, agencies often provide services that are the responsibility of another agency's jurisdiction without reimbursement. This is done with the expectation that at some time in the future the assisting agency will be the recipient of such services from the other agency. Generally, agencies provide services without reimbursement with the understanding that it is a short-term option. After a certain length of time (depending on the type of agreement that provides for such "mutual aid"), services will be rendered on a payable ("assistance by hire") basis. As discussed below, agreements which provide for services without reimbursement are used to address a variety of circumstances.

Under certain agreements, local governments are reimbursed for the services they provide in protecting SRA and assisting federal agencies. Listed below are the major examples of such agreements.

Local government entities such as cities, counties, and fire districts contract with CDFFP for it to provide local fire protection and emergency services. These contracts are referred to as "Schedule A" agreements. Generally, these local entities contract with CDFFP when they determine that it is more economical for CDFFP, rather than themselves, to provide the services. Local entities with such contracts range in size from very small cities such as Hamilton City (population 2,000) in Glenn County to large counties such as Riverside County. Some local government entities contract for complete fire protection services, while other local government entities elect to have CDFFP provide dispatch services only. When CDFFP provides fire protection services under these agreements, the local entity pays all of the state's firefighting costs, including equipment. In 2004-05, CDFFP expects to receive $190 million in reimbursements from local agencies for services provided under Schedule A agreements.

State and federal agencies have entered into an agreement referred to as the "Cooperative Fire Protection Agreement" which provides for interagency cooperation between these two levels of government. As part of this agreement, CDFFP and its federal partners have mapped out the entire state and determined in which areas it is most efficient for the state and federal governments to exchange resource protection responsibility. Lands are divided into "Direct Protection Areas" (DPA) delineated by boundaries regardless of statutory responsibility. For example, if a particular parcel is in SRA, but that parcel is surrounded by USFS fire stations, it may be more efficient for that parcel to be protected by the USFS, rather than by CDFFP. Once responsibility for protecting lands is determined, the agency accepting responsibility for the protection of that land assumes full financial responsibility for any firefighting costs associated with it. The agreement also provides that when the state requests federal assistance and vice versa, there are no cost reimbursements (excluding aircraft) for the first 24 hours of an incident. In addition, the agreement provides that each agency, to the extent possible, will fight fires consistent with the approach of the other agency had it been present.

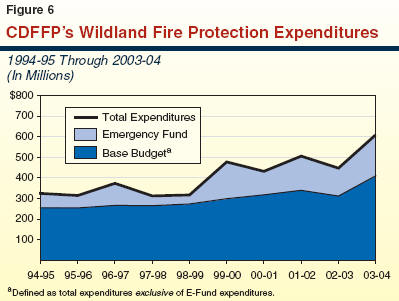

Expenditures for wildland fire protection represent the largest General Fund expenditure in the Resources Agency. In recent years, the average annual General Fund costs for wildland fire protection have exceeded $400 million, or about 40 percent of General Fund expenditures for the Resources Agency. The CDFFP's budget for wildland fire protection is unusual in that the administration has the statutory authority to exceed the initial appropriation when budgeted resources are insufficient to meet emergency needs. Over the last ten years, expenditures for wildland fire have generally increased. As discussed later, there are a number of factors which have driven costs upwards—increasing labor costs, the growing population in and around wildland areas, and unhealthy forest conditions (particularly in Southern California).

In budgeting for wildland fire protection, CDFFP distinguishes between the "normal," day-to-day, base costs of firefighting and those costs associated with emergency fire suppression that require additional staff and equipment beyond those that are regularly scheduled. The base costs include the day-to-day costs of operating CDFFP facilities, fighting fires, payments to contract counties, and fire prevention costs.

When additional resources for fighting fires are needed, these resources (such as overtime costs and equipment rental) are funded from the Emergency Fund, which is referred to as the "E-Fund." Because it is not possible to know the exact amount of funds that will be needed each year, the annual budget act provides a baseline appropriation for the E-Fund that in recent years has been based roughly on a ten-year average of these expenditures. The budget act authorizes the Director of Finance to augment the baseline appropriation by an amount necessary to fund the E-Fund.

Expenditures for Fire Protection Have Increased Over Time. As shown in Figure 6, CDFFP's total expenditures for wildland fire protection have increased over the last ten years. Increases have occurred in both base budget and E-Fund costs. Although total expenditure levels have varied significantly from year to year, on average expenditures for wildland fire protection have increased by 10 percent annually.

As shown in Figure 7, estimated 2004-05 expenditures for fire prevention and protection are about $522 million, a decrease of $90 million from estimated expenditures in 2003-04. The decrease in expenditures does not reflect a reduction in service. Rather, it largely reflects the fact that 2003-04 was a high fire year with correspondingly high E-Fund costs.

|

Figure 7 CDFFP’s Expenditures

for Wildland Fire Protection |

||

|

2003-04 and 2004-05 |

||

|

|

2003-04 |

2004-05a |

|

Fire Prevention |

$14.5 |

$22.9 |

|

Fire Control |

245.4 |

267.4 |

|

Cooperative Fire Protection |

34.7 |

38.5 |

|

Conservation Camps |

65.3 |

64.5 |

|

Emergency Fire Suppression (E-Fund) |

252.2 |

129.0 |

|

Totals |

$612.1 |

$522.3 |

|

|

||

|

a Estimated. |

||

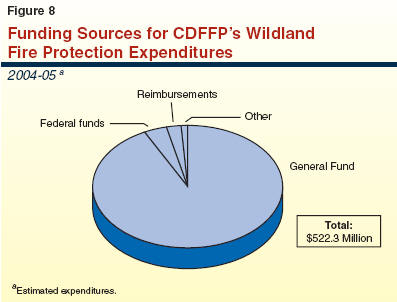

Funding Is Provided Mostly From the General Fund. As shown in Figure 8, the General Fund provides the bulk of support (about 94 percent) for CDFFP's expenditures for wildland fire protection on SRA. The remaining funds come from federal trust funds (3 percent) and from reimbursements and other funds (3 percent). In the "Issues" section that follows, we discuss the potential role of fees in funding the state's fire protection services.

There are a number of factors that drive the state's total fire protection costs—the occurrence of large and damaging fires, labor costs, wildland fuel conditions, and the extent of development in and around wildland areas. These factors help explain the increase in expenditures over time that is shown in Figure 6.

When a fire escapes "initial attack," the cost of fire suppression can rise quickly. This is because these fires often require large numbers of personnel and equipment, aviation support, lodging and meal costs, and overtime. In addition, during larger fire incidents, CDFFP often has to hire additional resources such as personnel and equipment. These resources can be very expensive. At the peak of the fire, costs for these fires can exceed $1 million a day.

The fuel conditions of wildlands can directly affect expenditures for wildland fire protection. Wildlands that consist of dead and diseased trees, overcrowded forests, and significant undergrowth are more susceptible to large and damaging fires. These conditions are referred to as wildland fuels. Fires resulting from these conditions require more resources to fight and for a longer period of time.

Currently, wildland fuels occur at very high levels in several parts of the state that are already considered at high risk for fire. This is especially true along the western slope of the Sierra Nevada range, and in Southern California. For example, in the Southern California forests in San Bernardino and Riverside Counties, there has been an elevated level of dead and dying trees because the forests are significantly stressed and vulnerable to infestation from recent years of drought. According to fire experts, the magnitude and extent of tree mortality has produced conditions which can result in very large and damaging wildfires. These conditions contributed to the severity of the fire season in Southern California during 2003-04 and continue to pose a high risk of large, costly wildfires. These conditions exist on state and federal responsibility areas and can exist in some areas for which local jurisdictions are primarily responsible for fire protection.

Recent efforts to reduce this high level of fuel have focused on Southern California and have been funded mainly from federal funds. The 2004-05 Budget Act also includes $39 million from Proposition 40 for fuel reduction efforts in the Sierra Nevada.

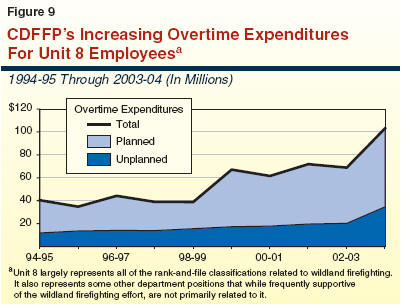

Firefighting is a labor-intensive activity. Labor costs account for a significant portion—roughly 50 percent—of CDFFP's costs for wildland fire expenditures. Any increases in compensation per employee, as well as in the number of employees and hours of overtime worked, can substantially impact expenditures for wildland fire protection. This section discusses recent increases in base compensation, overtime compensation, and retirement benefits for firefighters and related positions. The most recent increases occurred pursuant to a 2001 memorandum of understanding (MOU) with CDFFP firefighters (Unit 8). While Unit 8 largely represents all of the rank-and-file classifications related to wildland firefighting, it also represents some other department positions that while frequently supportive of the wildland firefighting effort, are not primarily related to it.

Increases in Base Compensation and Positions. During the last several years, firefighting personnel have received several negotiated base compensation increases. (Base compensation is defined as compensation exclusive of benefits and overtime compensation.) Unit 8 employees and their managers and supervisors were granted compensation increases in 1998-99, 1999-00, 2000-01, and 2003-04 (which was deferred until 2004-05). Each of these increases was between 4 percent and 5 percent annually—generally similar to the salary increases received during this time period by most state employees. Between 1998-99 and 2003-04, the total number of Unit 8 employees and their managers and supervisors also increased by roughly 15 percent, thereby contributing to the upward trend in total base compensation expenditures for wildland firefighting over the last several years. As a result of these factors, we estimate base compensation expenditures in 2003-04 are $46 million higher than in 1998-99.

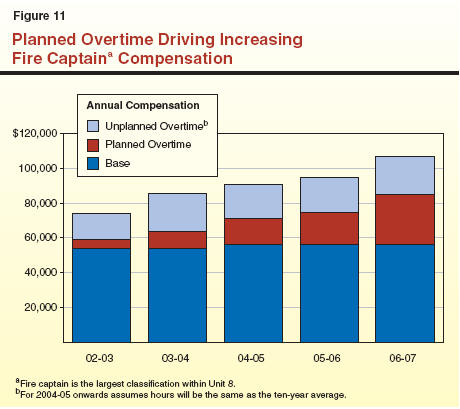

Increases in Overtime Expenditures. Overtime expenditures are a significant portion of CDFFP's costs for wildland fire expenditures. For example, between 1994-95 and 2003-04, overtime costs accounted for an average of 27 percent of total compensation expenditures for Unit 8 employees and their managers and supervisors. As shown in Figure 9, CDFFP's overtime costs consist of two types of expenditures: planned and unplanned. Planned overtime is the portion of the firefighters' regularly scheduled workweek for which they receive compensation at overtime rates. Firefighters receive overtime for a portion of a regularly scheduled workweek because federal labor law has been interpreted as requiring firefighters to receive overtime for any hours worked that exceed 53 hours a week. The CDFFP firefighters' scheduled work shifts exceed 53 hours pursuant to contract obligations. For example, during the fire season, firefighters normally work three 24-hour shifts in a week, for a total of 72 hours. Of this total, 19 hours are therefore considered "planned overtime." During the nonfire season, firefighters do not currently accrue planned overtime. Unplanned overtime is the compensation firefighters receive for working any unscheduled hours.

As shown in Figure 9, CDFFP's total overtime expenditures for Unit 8 employees and their managers and supervisors increased an average of 14 percent per year between 1994-95 and 2003-04. This increase reflects both increases in the number of overtime hours (planned and unplanned) worked and the base compensation increases discussed above which impact the amount at which each overtime hour is compensated. Additionally, this increase reflects a negotiated increase in the hourly compensation for planned overtime that took effect in 2003-04.

As regards the total number of overtime hours compensated, there was roughly a 61 percent increase in those hours between 1994-95 and 2003-04. Unplanned overtime can be due to a variety of factors, including larger fires and other emergencies, increasing vacancies, retirements and sick leave, and poor scheduling. The department has not done an analysis to determine the extent to which these and other factors are driving the increase in overtime hours.

Future-Year Costs of Planned Overtime Will Increase Substantially. The cost of overtime in future years will continue to increase substantially due to two provisions in the 2001 Unit 8 MOU. First, CDFFP firefighters will receive significant, incremental annual increases in planned overtime pay through 2005-06 due to changes in the formula used to calculate the compensation paid for each hour of planned overtime worked. We estimate that as a result of these changes alone, planned overtime expenditures in 2005-06 (including related retirement benefits) will be almost $47 million greater than the 2002-03 level.

Second, the 2001 agreement provides that beginning the last day of the agreement (June 30, 2006), firefighters will earn planned overtime year round, instead of only during the fire season as is the current practice. Practically speaking, this provision puts the state at a negotiating disadvantage in future contract negotiations by in effect setting a "base" level of compensation for the future based on one day at the end of the current contractual term. The cost of this change has not yet been calculated by the administration (DPA). Based on our analysis, we estimate that this change will result in additional annual costs of roughly $37 million beginning in 2006-07.

Summary: 2001 Unit 8 MOU Is Major Driver of CDFFP's Increasing Costs. In summary, when all of the fiscal provisions of the 2001 Unit 8 MOU are considered, they will result in significant compensation increases for employee classifications within Unit 8. Figure 10 shows the upward trend in the average compensation package for the three largest employee classifications under Unit 8 from 2002-03 to 2006-07. For example, as shown in Figure 10, the average annual regular compensation (excluding unplanned overtime compensation) for the Fire Captain classification (the largest classification within Unit 8 accounting for 43 percent of Unit 8 employees) will increase roughly 45 percent between 2002-03 and 2006-07. As shown in Figure 11, the increasing compensation is largely driven by increases in planned overtime compensation.

|

Figure 10 Compensation Increases

for Selected Unit 8 Employee Classificationsa |

|||||

|

|

2002-03 |

2003-04 |

2004-05 |

2005-06 |

2006-07 |

|

Firefighter II |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Base compensation |

$35,595 |

$35,395 |

$37,165 |

$37,165 |

$37,165 |

|

Planned overtime compensation |

4,603 |

7,819 |

10,240 |

12,525 |

18,916b |

|

Total regular compensation |

$40,198 |

$43,214 |

$47,405 |

$49,690 |

$56,081 |

|

Percent increase |

— |

7.5% |

9.7% |

4.8% |

12.9% |

|

Unplanned overtime compensationc |

$10,923 |

$13,238 |

$11,939 |

$12,450 |

$13,218 |

|

Total Compensation |

$51,121 |

$56,452 |

$59,344 |

$62,140 |

$69,299 |

|

Fire Apparatus Engineer |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Base compensation |

$42,508 |

$42,445 |

$44,567 |

$44,567 |

$44,567 |

|

Planned overtime compensation |

5,357 |

9,153 |

11,295 |

13,711 |

22,683b |

|

Total regular compensation |

$47,865 |

$51,598 |

$55,862 |

$58,278 |

$67,250 |

|

Percent increase |

— |

7.8% |

8.3% |

4.3% |

15.4% |

|

Unplanned overtime compensationc |

$11,463 |

$14,562 |

$14,479 |

$15,099 |

$16,030 |

|

Total Compensation |

$59,328 |

$66,160 |

$70,341 |

$73,377 |

$83,280 |

|

Fire Captain |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Base compensation |

$53,568 |

$53,665 |

$56,348 |

$56,348 |

$56,348 |

|

Planned overtime compensation |

5,210 |

9,982 |

14,986 |

18,273 |

28,679b |

|

Total regular compensation |

$58,778 |

$63,647 |

$71,334 |

$74,621 |

$85,027 |

|

Percent increase |

— |

8.3% |

12.1% |

4.6% |

13.9% |

|

Unplanned overtime compensationc |

$15,301 |

$21,557 |

$19,491 |

$20,326 |

$21,579 |

|

Total Compensation |

$74,079 |

$85,204 |

$90,825 |

$94,947 |

$106,606 |

|

|

|||||

|

a Data reflect average compensation (excluding benefits) for a full-year employee under each of the three largest Unit 8 classifications. 2002-03 and 2003-04 data are actuals; 2004-05 and future-year data are projections. |

|||||

|

b Assumes negotiated change to year-round planned overtime takes effect. |

|||||

|

c For 2004-05 onwards, assumes annual unplanned overtime hours for employee will be the same as the ten-year average of these hours from 1994-95 through 2003-04. |

|||||

Future Retirement Benefit Costs Will Also Increase

Substantially. Pursuant to legislation and related MOUs, changes have been made

to the calculation of firefighter retirement

benefits that will significantly increase the

department's costs over time. Specifically, prior to 2000,

the firefighter retirement benefit was 2.5 percent

at 55 years. Chapter 555, Statutes of 1999

(SB 400, Ortiz), increased the benefit to

3 percent at 55 years beginning in 2000. The

1999 and 2001 Unit 8 MOUs adopted the higher pension formula provided for in SB 400. In

2003, Unit 8 renegotiated the 2001 MOU to

3 percent at 50 years beginning on January 1, 2006.

The 1999 Unit 8 MOU has resulted in roughly $20 million of additional

retirement costs for the department each year since

2001-02. The cost of the retirement benefit adjustments will

continue to increase over time as the total amount of compensation paid

by the department increases and as the retirement benefit

is increased again to 3 percent at 50 years beginning in 2006.

The fiscal impact of the latter change has not yet

been calculated by the department.

Other Costs and Impacts of the Unit 8 MOUs. The Unit 8 MOUs discussed above will also result in significant additional costs to local governments which contract with CDFFP to provide local fire protection services. This is because as CDFFP's costs increase, the costs for local governments that contract for CDFFP's services will correspondingly increase. For example, the 2001 Unit 8 MOU resulted in about $9 million in additional costs to local governments in 2003-04. We estimate that the additional annual costs to local governments will increase from $9 million to $22 million by 2005-06 as a result of the 2001 Unit 8 MOU.

In addition, according to CDFFP, increases in planned overtime compensation is resulting in "salary compaction" problems. According to the department, it has been difficult to recruit to the chief officer positions from the rank-and-file positions because, as a result of the planned overtime compensation changes, there is no longer a significant pay differential between the highest rank-and-file positions and chief officer positions.

The area where human development meets and intermingles with undeveloped wildlands is commonly referred to as the wildland-urban interface or WUI. Of the approximately 8 million acres of WUI in California, about 5.5 million acres are considered at high risk of wildfire as shown in Figure 12. These high-risk WUI areas are characterized by a history of fire conditions that are favorable to wildland fire and the presence of structures. These areas include relatively sparsely populated areas as well as areas which may be urban in terms of density, but are also at risk of wildfire from high winds.

High-risk WUI areas are scattered throughout the state, with concentrations in the populated areas around the coastal and interior ranges of Southern California, the hillsides surrounding the San Francisco Bay, and the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Development in the WUI has been increasing and there is widespread agreement among land use planners that this trend will continue. Estimates by CDFFP show a 20 percent increase in the number of homes in the WUI from 1990 to 2000. The department also indicates that while the majority of houses in WUI are in areas for which local governments provide the primary fire protection services, some are also found in SRA. However, even in those areas outside of SRA, when wildland fires threaten homes and lives in WUI and require resources beyond those available from local government, state resources are often called upon as part of the state's integrated wildland fire protection system.

Increasing development in the WUI translates into increased fire protection costs for several reasons. First, because of the presence of life and property in the WUI, more resources are often deployed to suppress those fires than would be used in nondeveloped areas. The assets at risk in these areas include structures, power lines, and water supplies. Second, the presence of development can limit the fire prevention and suppression options available to wildland fire managers, thereby potentially increasing the fire risk of an area and increasing fire suppression costs. For example, development substantially restricts the ability of fire prevention agencies to use certain techniques such as prescribed burning to reduce the high volume of flammable vegetation intermixed with development. Lastly, the presence of people in wildlands can increase fire protection costs because fires from structures, vehicles, and human activities can quickly spread to the wildland vegetation.

In the sections that follow, we raise a number of concerns about the current delivery of wildland fire protection services in the state. We make a number of recommendations designed to contain costs and improve accountability of the service providers for their expenditures. While the involvement of multiple agencies provides an essential network of firefighting resources, many of the current problems stem from this multiplicity of service providers. In some cases, it is not clear who is fiscally responsible to provide certain services. Also, the multitude of interagency agreements has resulted in inefficiencies. In addition, it has been difficult to track the flow of funds among governments. Finally, we discuss opportunities to contain one of the most significant drivers of increasing costs—employee compensation.

Local Decisions in WUI Significantly Impact State Costs. As discussed earlier, the increasing presence of homes in WUI is expected to result in the continued increase in expenditures for wildland fire protection. The location of homes, level of vegetation clearance, and the type of building materials all affect the risk homes in WUI face from wildfire. The decisions on where and how these homes are built are generally made at the local level. However, the consequences of these decisions are experienced at both the state and local level. At the state level, for example, in the fast-growing foothill region of the Sierra, CDFFP reports the number of its life protection-related emergency responses (such as medical aids) more than doubled between 1993 and 2000—increasing from 10,000 to 25,000 responses. In addition, when a large wildland fire threatens a development, firefighting resources for structure and life protection beyond those available at the local level are often needed. The cost of those additional resources is generally borne by state taxpayers rather than local residents.

Opportunities Exist to Encourage "Fire Safe" Local Planning in WUI. In order to contain costs associated with development in WUI, the state should encourage local governments to make fire-safe planning decisions—local decisions that can reduce the risk from wildland fires. These decisions include planning decisions on where to locate development, fuel management plans, and building codes and designs that address wildland fire. The Legislature has recently taken action related to planning decisions in SRAs and other high fire risk areas. For example, the Legislature enacted Chapter 951, Statutes of 2004 (AB 3065, Kehoe), that requires local jurisdictions that contain SRA or high-risk fire hazard zones to submit the safety element portion of their general plans to the BOF for review.

We think that there is an additional opportunity to provide an incentive for fire-safe planning by local governments in WUI areas. Specifically, current law should be clarified to provide explicitly that the state is not fiscally responsible for life and structure protection in SRA. As discussed earlier, current law does not specifically address which level of government—state or local—is responsible for life and structure fire protection in SRA. While current law authorizes CDFFP to provide day-to-day life and structure fire protection in SRA when resources permit, it does not require that CDFFP provide these services. Similarly, current law does not require local agencies to provide for life and structure fire protection in SRA.

The statutory clarification described above could help in a couple of ways to address the increasing fire protection costs (state and local) associated with the continued development in WUI areas. First, if local agencies are clear that the state is not fiscally responsible for life and structure protection, this should encourage local land-use decisions that attempt to minimize the risk to structures and people from wildfire. Second, a clear statement that the state is not responsible for providing life and structure fire protection could encourage local governments to budget an appropriate level of local resources for this purpose. This would reduce the cost pressure on the state to increase its investment for this type of fire protection.

There are a couple of policy rationales for the state not being fiscally responsible for life and structure protection in SRA. First, since the state does not make the development decisions which determine where and how structures are built in the WUI, it should not be fiscally liable for the firefighting cost impacts of these decisions. Second, as discussed previously, the provision of life and structure protection is consistent with the traditional role of local government to provide day-to-day fire and police services for the residents under its jurisdiction.

We think that any such clarifications to the state's responsibilities for life and structure fire protection in SRA should nevertheless maintain the state's commitment to participate in mutual aid agreements which dispatch the closest available resources to an incident because these agreements are in the best interest of public safety. The proposed clarification would specifically address the issue of fiscal responsibility for the provision of certain fire-related protection, regardless of who actually provides the service in question.

Would this clarification of state fire responsibilities impose a reimbursable mandate on local governments? Proposition 1A, approved by the state's voters in November 2004, broadens the definition of a mandate to include transfers by the state to local governments of financial responsibility for a "required program for which the State previously had complete or partial financial responsibility." Because state statutes do not specify a state responsibility to provide life and structure fire protection (and, in fact, constrain CDFFP's authority to provide these services to budget limitations), we think it is unlikely that such a clarification of the state's role regarding fire services would be considered to be a state-reimbursable mandate.

As discussed earlier, there are a number of different types of interagency agreements which guide the multiagency efforts to deliver wildand fire protection services. Our discussion in this section focuses on the multiplicity of agreements CDFFP uses for hiring local resources. Currently, CDFFP may hire local resources under the CFAA to assist in fighting larger fires. This agreement provides a standardized reimbursement formula when state and federal agencies hire local resources. In addition, CDFFP has hundreds of other agreements with various local entities to hire local firefighting resources for wildland fire protection. In the sections below, we discuss how the variation in these latter agreements can result in confusion and inefficiencies, and complicate state oversight of the implementation of these agreements. We then recommend that CDFFP replace the existing multiple agreements for hiring local resources with a uniform agreement, such as one modeled on the CFAA.

Current System of Multiple Agreements Is Confusing and Cumbersome. As discussed earlier, local CDFFP units have entered into agreements with local fire agencies for hiring local resources. Our review of a sampling of agreements between local CDFFP units and local agencies found that because each local CDFFP unit generally negotiates its own agreements independently, the agreements often have different terms resulting in differing levels of reimbursement to local agencies for assisting CDFFP. These differences exist even after accounting for differences among local agencies in pay scales.

These differences in how much local agencies are reimbursed occur largely because the agreements differ in specifying when reimbursements are to occur after local agencies respond to an emergency. For example, an agreement with El Dorado and Amador Counties requires reimbursement after six hours, whereas agreements with Yuba and Placer Counties call for reimbursements after 12 hours.

Our review of a sampling of agreements also found that they differ considerably in the extent to which they specify other terms and conditions related to hiring local resources. For example, an agreement with Nevada and Placer Counties specifies in detail the training and equipment standards that must be satisfied as a condition of CDFFP hiring the local resources, whereas agreements with Santa Clara, Alameda, and Contra Costa Counties do not provide such conditions.

A recent report by the Governor's Blue Ribbon Fire Commission (which included representatives from state, local, and federal agencies and elected officials) raised concerns with the number of, and differences among, the agreements used to hire local resources. In subsequent discussions with commission staff, we determined that there were essentially four consequences of multiple agreements. First, since there can be multiple agreements under which a local agency can be hired, it can be difficult for local governments to determine their obligations and the terms of their assistance during emergencies as the terms of these agreements vary. Second, the state may be compensating local agencies differently for providing essentially the same level of service at roughly the same costs, due to differences in reimbursement rates among the agreements. Third, a multiplicity of agreements is administratively inefficient as this adds to the cost of negotiating, monitoring, and making payments under the agreements. Finally, based on discussions with OES and the findings of the Blue Ribbon Commission's report, there is evidence that local entities may delay accepting a request for assistance under one type of agreement if they anticipate receiving a similar request for assistance under a different agreement with higher reimbursement rates. This has sometimes led to a delay in local firefighting resources reaching a fire.

A Uniform Agreement Would Promote Consistency and Efficiency. To address the problems with multiple agreements for hiring local resources, the Blue Ribbon Commission recommended replacing the multiple agreements with a uniform agreement. Such an agreement would use a consistent methodology for calculating reimbursements and set up consistent terms for local agency response. We concur with the Blue Ribbon Commission recommendation and therefore recommend the enactment of legislation directing CDFFP to adopt a uniform agreement at the statewide level for hiring local resources. The adoption of a uniform agreement for hiring local resources will result in benefits to both state and local entities and address the concerns with the existence of multiple agreements discussed earlier.

While it is not possible to provide a specific estimate of the cost savings from adopting a uniform agreement for hiring local resources, we think that such an approach will result in efficiencies and improvements in oversight that will assist the department in controlling costs and achieving some level of savings in the future.

We think the department could implement the Legislature's direction to adopt a uniform agreement for hiring resources relatively easily. This is because an agreement and system (the CFAA) for hiring local resources using standardized terms and reimbursement rates already exists, as discussed earlier. We think that CDFFP can use the CFAA as a model to develop a new, uniform agreement for hiring local resources with local agency participation.

Summary of LAO Proposal. As shown in Figure 13, currently local CDFFP units negotiate agreements with local agencies for hiring local resources, resulting in a system of multiple agreements that is confusing and cumbersome. Instead, we recommend that these multiple agreements be replaced with a uniform agreement at the statewide level for hiring local resources. The uniform agreement could largely be modeled on an existing agreement that would be retained—the CFAA—which is used by federal and state agencies for hiring local resources on generally larger wildland fires. While our proposal affects the hiring of local resources by CDFFP, our proposal leaves in tact both the existing mutual aid system under which services are provided among jurisdictions without reimbursement and the existing agreements under which local agencies contract for CDFFP's services.

Budget Reflects Repeal of Fire Protection Fees. A bill accompanying the 2004-05 budget repealed a previously authorized fire protection fee that was to be levied on private landowners in SRA. This fee—which was repealed before an initial collection occurred—would have partially supported the state's fire protection services provided to these landowners. This annual fee was to be assessed on private landowners at a flat $35 per parcel in SRA, and would have raised roughly $40 million toward the annual cost for these firefighting services—estimated to be $522 million in 2004-05. As a consequence of this budget action, the state's fire protection services to private landowners in SRA are almost entirely funded from the General Fund.

Recommend Reconsideration of Fee. We think the Legislature should reconsider enacting a fee to partially support the state's fire protection services for a couple of reasons. First, we think that the fee could be restructured to address the equity concern raised about the prior fee. The concern was that a flat fee of $35 per parcel did not fairly reflect the different levels of benefits received by property owners with different sizes of property. As we discuss later in this section, there are ways to restructure the fee to strengthen the relationship between the amount of the fee assessed and the benefit a particular landowner receives from the state's firefighting services.

Second, there has been additional analysis that responds to previously aired concerns that a SRA fee would result in some landowners in effect paying twice (to both the state and a local government) for the same level of fire protection. As discussed earlier, the local assessments (whether levied by a special district or as part of the property tax assessment that pays for municipal fire protection) are used to support life and structure fire protection services that have been traditionally the responsibility of local governments. These current local assessments do not support the state's wildland fire protection services received by private landowners living on SRA lands. Without the SRA fees, these private landowners are not contributing to the separate obligation of CDFFP to provide wildland fire protection on the mostly private lands in SRA.

Recommend Fire Fees Be Reinstated and Modified. We recommend that the Legislature reinstate fire fees for property owners in SRA because these property owners directly benefit from CDFFP's fire protection services. However, the state's general population also benefits from CDFFP's wildland fire protection through the preservation of natural lands and their wildlife habitat. We therefore think the state's costs for providing fire protection on private SRA lands should be shared evenly between property owners benefiting from these services and the general public. Such an even sharing of costs is reflective of the benefits to private landowners from the state's fire protection efforts as well as the benefits to the general public. We therefore recommend the enactment of legislation to reinstate fire protection fees and set them at a level so that the state's costs of providing fire protection on SRA are shared evenly between private landowners and the General Fund. Sharing the costs of providing fire protection on SRA evenly between property owners and the general public would result in annual savings of about $244 million to the General Fund.

As we discussed in our Analysis of the 2003-04 Budget Bill (see page B-88), there are a number of potential ways that such fire protection fees could be structured. For example, fees could be based on the wildland fire risk to a particular area, the type of land and the presence of structures, or past actual costs. Other ways of structuring the fees include a simple flat per-acre fee or per-parcel fee, or as a flat fee that is tiered based on risk and other factors. Regardless of what the fees are based on, they could be adjusted to provide an incentive to property owners to take steps that potentially lower the extent of state fire protection services that would be needed. For example, landowners that meet certain fuel clearance standards around their homes by performing specified fuel reduction and other fire-safe planning activities could be eligible for a reduced fee. Such a reduction in the fee recognizes that there is less potential cost to the state in providing fire protection services if landowners undertake these fire-safe planning activities.

We think that a per-acre fee, which would vary depending upon the type of land and presence of structures, is the preferred approach among these options for a couple of reasons. First, such a per-acre fee is a reasonable proxy for the benefit to landowners from the state's fire protection services in SRA. This is because the fee would reflect the department's generally higher costs to fight fires on larger parcels with certain characteristics, such as the presence of timber. Second, a per-acre fee would be relatively administratively efficient to assess and collect because most of the data necessary to determine the fee for an individual landowner exists and a collection mechanism already exist with the property tax assessment process. That is, the fee could be billed along with the landowners' annual property tax assessments.

An important step towards identifying potential savings and efficiencies for wildland fire expenditures is to improve the accountability and transparency of CDFFP's expenditures. In the sections below, we identify areas where these factors can be strengthened while also maintaining the department's flexibility to respond to wildland fires.

When CDFFP provides assistance for those fires or portions of fires that are considered a federal responsibility, it fronts money from the General Fund to cover these costs prior to reimbursement from the federal agencies after the fire. As we discuss in our Analysis of the 2005-06 Budget Bill (see page B-56), we find that the Legislature lacks oversight over the subsequent use of these unanticipated federal funds by CDFFP (that is, federal funds received as reimbursements for which expenditure authority has not been provided in the annual budget act).

Legislature Lacks Oversight of Federal Reimbursements. The budget act generally requires that the Legislature be notified before a department can spend unanticipated federal funds which it has received. However, since 2002-03, the budget act has exempted CDFFP from this notification requirement. This exemption in effect allows the department to make significant changes to its legislatively approved budget without legislative notification. In fact, the department has used the unanticipated federal funds to "free up" General Fund monies which it then used to augment other programs beyond their budgeted level of expenditures. This happens because the CDFFP's annual support budget is appropriated as a lump sum without any scheduling among program areas, such as fire protection and resource management. This lack of scheduling enables the department to transfer funds among program areas without legislative notification, thereby impeding legislative oversight and preventing the Legislature from using these funds for its priorities within the department. For example, our review found that in 2003-04 the department used about $39 million in unanticipated federal funds to in effect augment programs in various areas of the department's budget, including resource management, without legislative review. This type of diversion of funds circumvents the Legislature's appropriation authority.

Improving Oversight of Cost Recoveries. We recommend the Legislature take the following actions to improve legislative oversight of cost recoveries from federal agencies.

Recap of Increasing Employee Compensation Costs. As discussed earlier, labor costs for wildland firefighting are projected to continue to increase significantly as a result of the 2001 Unit 8 MOU. As a result of this MOU, for example, we project that annual planned overtime expenditures alone will increase by almost $47 million from 2002-03 through 2005-06, due to negotiated increases in compensation per hour of overtime worked. In addition, beginning in 2006-07, firefighters will earn planned overtime year round, instead of only during the fire season, resulting in additional costs of $37 million annually. The changes in planned overtime will result in an average increase in the regular compensation for selected employee classifications of 42 percent by 2006-07.

The recent 2001 Unit 8 MOU has also increased costs to local governments to reimburse CDFFP and created recruiting problems for the department. The 2001 Unit 8 MOU resulted in about $9 million in additional annual costs to local governments in 2003-04. In addition, CDFFP has reported that as a result of the increases in planned overtime, it has become difficult to recruit to the chief officer positions from the rank-and-file positions because there is no longer a significant pay differential between the highest rank-and-file positions and the chief officer position.

Opportunities to Reduce Costs. We think that there are opportunities to reduce labor-related costs to the state and local governments for wildland fire protection and also to address the department's recruiting problems. As a first step, we think that there is a need for better information on the full cost impacts of the 2001 Unit 8 MOU and on the factors driving the department's increasing use of unplanned overtime. Our first two recommendations below address these information needs. Finally, we follow with options for the Legislature to consider for reducing costs associated with the 2001 Unit 8 MOU.

Full Costs of 2001 Unit 8 MOU Are Unknown. As discussed earlier, at the time the Legislature approved the 2001 Unit 8 MOU, DPA did not provide information to the Legislature on the significant cost associated with changing the department's firefighter staffing pattern to a 72-hour work week. As of the writing of this report, this information was not available from DPA. (We have, however, been able to develop a rough estimate that these costs will be about $37 million annually.)

Require DPA to Provide Cost Estimates Due to Staffing Schedule Changes. In order for the Legislature to evaluate the complete costs of the 2001 Unit 8 MOU, we recommend the Legislature require DPA, in conjunction with CDFFP, to provide information on the costs associated with changing the staffing patterns to a 72-hour work week year round. These cost estimates should include estimates of increased compensation expenditures, as well as any other operational costs that may be necessary to accommodate changing the staffing pattern to a 72-hour week.

Analysis Lacking on the Use of Unplanned Overtime. Despite increasing overtime costs, CDFFP has not done an analysis of the factors driving its use of unplanned overtime. As discussed earlier, the use of overtime can be due to factors such as larger incidents, vacancies, retirements, use of overtime to cover for sick leave, and inadequate management and controls and oversight.

Recommend CDFFP Conduct an Analysis of Unplanned Overtime Costs. In order to address the issues driving departmental overtime costs, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDFFP to conduct a thorough analysis of its unplanned overtime costs, including an analysis of when unplanned overtime hours are used. A similar analysis was conducted recently by the Department of Corrections. We think such an analysis can be used to evaluate the appropriate staffing levels of the department and should result in specific recommendations. For example, if current compensation levels are maintained, it may be more cost-effective for CDFFP to hire more personnel as an alternative to relying on unplanned overtime to meet staffing requirements.

In a prior recommendation, we recommended that DPA, in conjunction with CDFFP, provide the Legislature with a revised cost estimate for changing the department's firefighting staffing pattern to a 72-hour work week, as provided in the 2001 Unit 8 MOU. If these cost estimates are significantly greater than previously projected when the MOU was approved by the Legislature, we recommend the Legislature consider opportunities to reduce the costs through a renegotiation of the 2001 Unit 8 MOU. We also think that given the state's fiscal condition, the Legislature may wish to re-examine the other planned overtime provisions in the 2001 Unit 8 MOU that have contributed significantly to increased overtime expenditures. Such a re-examination of a contract would be consistent with past legislative practice. For example, the Legislature reconsidered and approved a revised contract for correctional officers this past session.

The specific level of savings that can be achieved will depend upon the terms of the renegotiated MOU. For example, maintaining the current staffing patterns rather than shifting to a year-round fire staffing pattern would result in significant annual General Fund savings beginning in 2006-07 of about $37 million. As another example, if an agreement were reached to reinstate the formula used to calculate the compensation paid for each hour of planned overtime that was in effect in 2003-04, this would create about $16 million in savings to the state in 2005-06. Using the formula in effect in 2003-04 would still result in average regular compensation that is about 7.5 percent higher than that in effect prior to the 2001 Unit 8 MOU. However, DPA indicates it is difficult to project the actual total level of savings from these and other changes that might be renegotiated because it is likely that any savings from changes to planned overtime would be partially offset by concessions granted in other areas of the contract.

The above potential changes to the planned overtime provisions could also help to address the "salary compaction" issue to the extent that the changes help to maintain a more significant salary differential between the highest rank-and-file positions and chief officer positions. Lastly, changes to planned overtime that reduce the state's costs would also result in significant cost savings to local governments which contract with CDFFP to provide local fire protection services. For example, we estimate potential savings for local governments in 2005-06 of about $13 million.

We note that the administration previously attempted to renegotiate the 2001 Unit 8 MOU during the spring and summer of 2004 to reduce costs in an effort to address the state's fiscal condition. The DPA reports that these negotiations were unsuccessful because the union had no incentive to make concessions. In order to provide an incentive for negotiations, the Legislature has the option under current collective bargaining law of not approving funding in the annual budget act for the incremental increases in planned overtime compensation. Such an action would likely reopen negotiations because funding would not be available to pay for the incremental budget-year costs of the Unit 8 agreement.

State, federal, and local firefighting agencies in California rely on a complex series of agreements and practices which result in a multiagency wildland fire protection system. We find that state costs to provide fire protection have increased significantly over the last decade. We recommend the Legislature take a number of steps to improve the efficiency and accountability for delivery of wildland fire protection services and to reduce the state's expenditures on wildland fire suppression. These steps include: (1) clarifying state responsibilities for structure and life fire protection; (2) directing CDFFP to replace the myriad of agreements used to hire local resources with a single agreement; (3) authorizing fire protection fees and setting them at a level so that the state's costs of providing fire protection on SRA are shared evenly between private landowners and the General Fund; (4) improving legislative oversight of federal reimbursements; and (5) directing the administration to conduct an analysis of the factors driving unplanned overtime costs and to provide cost estimates of changing the staffing pattern to a 72-hour work week year round, potentially opening the door to a renegotiation of the 2001 Unit 8 MOU.

Glossary of Common Wildland Fire TermsAir Attack Planes—The planes that fly over an incident, provide information to the incident commander on the ground, and direct airtankers and helicopters to critical areas of a fire. Airtanker—Large planes used to drop fire retardant and water on wildland fires. Conservation Camps—The facilities that house the 198 inmate fire crews used by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CDFFP). There are currently 41 conservation camps throughout the state. Contract Counties—Counties which provide fire protection services on behalf of CDFFP in State Responsibility Areas within county boundaries. These "contract counties" include Los Angeles, Marin, Orange, Santa Barbara, Kern, and Ventura Counties. California Fire Assistance Agreement—An agreement among the federal forest service agencies, CDFFP, and local government entities (coordinated by the Office of Emergency Services) for the use of local government firefighting resources on wildland fires. Cooperative Fire Protection Agreement—An agreement among federal forestry agencies and CDFFP which provides terms and conditions for interagency cooperation. Direct Protection Area (DPA)—The area protected by an agency with its own fire protection force. Fire Crew—Crews of 12-17 inmates used by CDFFP to construct fire lines by hand in areas where heavy machinery cannot be used. All inmate crews are directly supervised by a CDFFP fire captain. Initial Attack—The first attack on the fire. Municipal fire departments call this the first alarm. Mutual Aid—The rendering of firefighting services by one jurisdiction to the benefit of another jurisdiction. Prescribed Fire—A deliberate burn of wildland areas in order to achieve a planned resource management objective. Schedule "A" Agreements—Contracts among CDFFP and local government entities such as cities, counties, and fire districts for CDFFP to provide local fire protection and emergency services. State Responsibility Areas (SRA)—Areas in which the primary responsibility for preventing and suppressing fires is that of the state. The SRA lands consist mostly of privately owned forestlands, watershed, and rangelands. The SRA lands must be designated as such by the Board of Forestry and must be covered wholly or in part by timber, brush, or other vegetation that serves a commercial purpose or that serves a natural resource value. Wildland Fire—Those fires that occur on lands with natural vegetation such as forests, grasslands, or brush, and generally minimal or no development. Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI)—The area where human development meets and intermingles with undeveloped lands. |

| Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by Jennifer Giambattista, under the supervision of Mark Newton. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |