Proposition 76 on the November Special Statewide Election ballot is a complex measure that would have far-reaching effects on the state budget. In this report, we describe the measure’s key provisions and provide answers to some of the questions that have been raised about its potential impacts on state and local governments. The report has been prepared to facilitate testimony at a legislative joint overview hearing on the measure.

Proposition 76 makes major changes to California’s Constitution. These changes would have substantial and far-reaching effects on the state budget. As shown in Figure 1, the measure creates an additional state spending limit, grants the Governor substantial new power to reduce state spending, alters key provisions of Proposition 98, and makes a number of other changes related to transportation funding, loans between state funds, and payments to various entities. In this report, we briefly describe each of the measure’s key provisions and address a number of questions that have been raised regarding its potential impacts on state and local budgets.

|

Figure 1 Proposition 76: Main Provisions |

|

|

|

� An Additional State Spending Limit |

|

� Places a second limit on state expenditures, which would be based on an average of revenue growth in the three prior years. |

|

� Budget-Related Changes |

|

� Grants the Governor substantial new authority to unilaterally reduce state spending under certain conditions. |

|

� Continues spending based on prior-year budget when new budget is late. |

|

� School Funding Changes (Proposition 98) |

|

� Changes several key provisions in the State Constitution relating to the minimum funding guarantee for K-12 schools and community colleges. |

|

� Other Changes |

|

� Makes a number of other changes relating to transportation funding; loans between state funds; and payments to schools, local governments, and special funds. |

California currently has a spending limit which is tied to appropriations in 1979-80 and is adjusted annually for growth in the economy and population. Since the 2001-02 revenue downturn, actual state expenditures have been well below this limit.

Proposition 76 adds a second limit, but one based on average revenue growth. As indicated in Figure 2, spending from the state’s General Fund and special funds would be limited to the prior-year level, adjusted by the average of the growth rates in combined General Fund and special fund revenues during the prior three years. If revenues exceed the limit, the excess amount would be allocated proportionally among the General Fund and each of the state’s special funds. The amounts allocated to special funds would be held in reserve until they could be spent in subsequent years. The General Fund amounts would be allocated for reserves; payments for various obligations in the areas of debt repayment, schools, and transportation; and construction projects.

|

Figure 2 New Spending Limit |

|

|

|

�

Spending from the state’s General Fund and special

funds combined |

|

� Revenues in excess of this limit allocated between the General Fund and each of the special funds. |

|

Special fund’s portion held in reserve for expenditures in future years. |

|

General Fund’s portion allocated for specified purposes, including

|

Would This New Limit Reduce Spending?

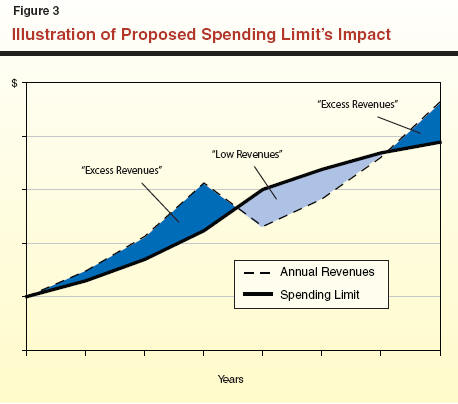

The answer to this question depends on whether the Governor and Legislature could accumulate enough reserves during high revenue-growth periods to cushion spending during bad times.

If the state were able to set aside sufficient reserves in the excess-revenue period, these funds could be used to supplement revenues and maintain spending at the spending cap level during the low- revenue years. In terms of Figure 3, this means that enough reserves would need to be set aside during the “excess-revenues” period to maintain spending at the limit during the “low-revenues” period. To the extent this occurred, the primary impact of the limit would be to “smooth out” spending over time.

If it were not able to set aside sufficient reserves, then spending would need to be reduced during the low-revenue period in order to maintain a balanced budget. Since the subsequent year’s limit would be based on the reduced level of spending, the limit itself would ratchet downward. As a result, allowable spending would be reduced over time.

As a practical matter, it may prove difficult for the state to accumulate reserves that are large enough to fully cushion the budget in low-revenue years. The amount of reserves needed would be dramatically larger than what the state has been able to accumulate in the past. A further complicating factor is that the proposition itself designates that most of the General Fund’s portion of excess revenues be devoted to one-time spending rather than reserves. For these reasons, we conclude that the limit would likely reduce state spending over time.

Yes, the limit would apply to all special funds, including those devoted to transportation and programs carried out by local governments. The state collects several billions of dollars in taxes that local governments use for local services and programs. These taxes include a half-cent sales tax and vehicle license fee for health and social services programs, and fuel taxes for roads and transportation programs. Because these taxes are deposited into state special funds, they would be subject to the terms of this measure. Thus, some revenues allocated to local governments may be held in reserve if total revenues affected by this measure exceeded the spending limit.

The answer to this question depends partly on how the excess revenues were allocated among the General Fund and special funds. This would be an important implementation issue if the measure were to pass. Proposition 76 requires that excess revenues be allocated proportionally to the General Fund and special funds, but does not specify the methodology for this apportionment. As a result:

If the allocation were based on each fund’s contribution to the excess revenues in a given year, then most of the required adjustments would likely take place in the General Fund. This is because most of the revenue fluctuations would likely be attributable to General Fund sources, such as the inherently volatile personal income and corporate taxes. Under an apportionment method based on each fund’s contribution to excess revenues, the effects of the limit on special funds-especially those with stable revenue sources, such as transportation funds-would be comparatively modest.

If, however, the allocation were based on each fund’s share of total revenues, then spending in all state funds would be proportionally affected whenever combined General Fund and special fund revenues exceeded the limit-regardless of which fund was responsible for the excess. Under this method of apportionment, a spike in General Fund revenues could require a temporary reduction in special fund spending, even in the case where revenues to the special fund were stable. We note that any revenues that could not be spent would be held in each special fund’s reserve for expenditures in a subsequent year.

Yes, the state could raise taxes for either general or specific purposes under the proposed limit. If the state were under Proposition 76’s spending limit, it could immediately spend these new tax revenues. If, however, the state were at its limit, it would not be able to use the proceeds immediately. It would, however, eventually be able to use new tax proceeds as the impact of the tax increase worked its way into the new spending limit’s adjustment factors over several years.

The provisions of this measure relating to the budget process are summarized in Figure 4. They fall into two main areas.

|

Figure 4 Main Budget-Related Provisions |

|

|

|

�

New Powers for Governor. Grants Governor

substantial new authority to unilaterally reduce state spending

under certain conditions. |

|

Governor can declare a fiscal emergency if his or her administration finds that revenues are falling below estimates or reserves are declining by more than one-half. |

|

If Legislature and Governor cannot agree on solutions within 45 days

|

|

� Late Budgets. When new budget is not enacted, spending authorized in prior-year’s budget continues. |

Expanded Governor Powers. Under the State Constitution, the Legislature is given the sole authority to appropriate funds and make reductions to enacted appropriations. This measure would give the Governor substantial new powers to unilaterally reduce spending under certain circumstances. Specifically, the measure permits the Governor to declare a “fiscal emergency” when his or her administration finds that either (1) revenues are falling 1.5 percent below its estimates, or (2) that the state’s budget reserve will fall by more than one-half between the beginning and end of the fiscal year. If the Legislature and Governor cannot agree on solutions which address the emergency within 45 days (30 days in the case of a late budget), then the Governor is given power to reduce spending in most areas of the budget. The Legislature could not override the reductions.

Late Budgets. Under current law, if a budget has not been enacted prior to the beginning of a new fiscal year, most spending does not have authorization to continue, although court decisions and legal interpretations have identified certain types of payments that may continue to be made when a budget is not enacted. This measure requires that when a budget is late, the spending levels authorized in the prior-year’s Budget Act remain in effect until a new budget is enacted.

The specific thresholds set forth by the measure for declaring fiscal emergencies are not particularly high. For example, a 1.5 percent deviation on revenues could occur frequently, given the volatility of revenues, especially in individual months within the fiscal year. Thus, the frequency of emergency declarations would largely be at the discretion of the administration.

The Governor would be given broad authority to reduce General Fund spending in most areas of the budget, including education, health and social services, and criminal justice. The measure specifically states that all expenditures would be subject to reductions, except for debt service, appropriations necessary to comply with federal laws and regulations, or appropriations where the reduction would result in a violation of contracts.

Roughly $7 billion-or 8 percent-of the General Fund budget would be largely “off limits” either because the spending is for debt service or a reduction would result in impairment of a pre-existing contract-such as would be the case for retirement contributions for existing employees.

The answer to this question is not straightforward. This is because in many programs there are limited or no federal requirements for states, while in some instances there are federal requirements. For example, there is a modest amount of spending in areas where there are specific federal requirements for states to provide services for children. Spending reductions in these areas would be limited to one degree or another by the federal requirements.

There is, however, roughly $22 billion in state General Fund spending in programs such as California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs), Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Program (SSI/SSP), Medi-Cal, and special education, where funding is provided jointly by federal and state governments. State participation in most of these programs is optional, but in order to qualify for federal funding, participating states must comply with federal rules relating to minimum funding requirements, eligibility guidelines, and minimum service levels. The measure would appear to permit the Governor to reduce spending in these areas by any amount. As a practical matter, reductions to these programs beyond a certain point would be discouraged by the loss of federal funds that could occur if state funding were cut below federally specified minimum levels.

Some health and social services programs are “entitlements” under current state law, meaning that individuals meeting specified eligibility criteria are entitled to the benefit regardless of whether adequate funds have been appropriated in the budget. Major entitlement programs are mainly in the health and social services area, and include Medi-Cal, CalWORKs, and SSI/SSP.

The measure provides the Governor with the power to reduce spending on entitlement programs. However, it does not provide the Governor with authority to change the laws which govern the entitlement (such as the amount of a monthly welfare grant payment, the scope of a medical service, or who is eligible for a particular program). Consequently, in the absence of a change by the Legislature to the underlying laws, these programs would continue to operate under the terms of existing law until the remaining funds were exhausted.

Our reading of the proposition is that the state would no longer be required to provide funds for the program. Under this measure, a program recipient’s entitlement to benefits would be contingent on the availability of funds. As one hypothetical example, suppose that the Governor elected to reduce spending for welfare grants by one-twelfth (8.3 percent) of the annual budget. Absent changes by the Legislature to the underlying laws governing the program, monthly payments would continue unchanged until available funds were exhausted. In this example, the spending reduction would probably result in recipients receiving no state-funded benefit payments during the last month of the fiscal year (June). At the start of the next fiscal year (July) state-funded payments would resume under the terms of the budget.

Yes, the Governor’s reductions could potentially affect local governments (mostly counties) in two main ways.

Shift of CalWORKs Costs. Some individuals who temporarily lose state-funded benefits might be eligible for county-funded benefits. For example, under current state law, counties make welfare payments directly to eligible families using a combination of federal, state, and county funds. If state and federal funds ran out before the end of the fiscal year due to a Governor’s reduction, it appears that counties would be required to pay benefits out of their own funds until the start of the next fiscal year.

Increased Demand for Local Services. State law requires counties to be the “provider of last resort” for certain health and social services to people with low incomes. If support for similar programs operated by the state declined as a result of this measure, counties could experience increased demand for their programs. For example, if state funds for Medi-Cal and Healthy Families programs were exhausted as a result of a Governor’s reduction, some low-income adults and children could seek assistance from county indigent health care programs, thereby increasing county costs for providing such services.

The state also appropriates state funds annually to local governments to support local and shared state-local programs and services, including public protection, health, and social services. These appropriations could be reduced by the Governor.

We do not believe that the continuing budget provisions, by themselves, would create more pressure for on-time budgets. Absent a fiscal emergency, all programs that had received state funding in the previous year would continue to operate under a “status quo” budget until a new budget were enacted. Under existing law, a significant amount of state spending is temporarily halted during a late-budget period. In this regard, this measure would likely reduce the pressure for an on-time budget.

We note, however, that other provisions of this measure-in particular, the expanded powers of the Governor to declare a fiscal emergency and ultimately unilaterally reduce appropriations at his or her discretion-may provide incentives for on-time budgets.

No, in the case of a late budget (with no fiscal emergency), the amount of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee would not be affected. In such cases, there would be some appropriations for schools (particularly for categorical programs) that could be temporarily held at prior-year levels. However, this would not have any effect on total school spending required by Proposition 98 for the fiscal year.

Proposition 98 is a measure passed by the voters in 1988 which established in the State Constitution a “minimum funding guarantee” for K-12 schools and community colleges (K-14 education). Each year, the minimum guarantee is calculated based on a set of funding formulas.

Under the main funding formula (referred to as “Test 2”), the guarantee increases roughly in line with school attendance and the state’s economy. In 1990, voters approved Proposition 111. Among other things, this measure added an alternative, less generous, formula (referred to as “Test 3”) to Proposition 98. The alternative formula allows school funding to grow more slowly when state revenues are weak. When this occurs, the difference between the reduced funding level and that which would be required by the main funding formula is tracked, and referred to as “maintenance factor.” As state revenues improve, Proposition 98 requires that the state spend more on schools to “restore” this maintenance factor-in effect, returning schools to where they would have been absent the reductions. Presently, the state has $3.8 billion in maintenance factor outstanding.

Also, when the Legislature spends more money on schools than is required by the minimum guarantee, the added funds raise the minimum guarantees by comparable amounts in future years.

As shown in Figure 5, this measure would eliminate the Test 3 and maintenance factor provisions of Proposition 98. Thus, school funding would no longer automatically fall during bad times and rise back up to the main guarantee level in good times. It would also count any funding above the minimum guarantee as one-time, meaning that that future minimum guarantees would no longer be increased by comparable amounts. For more detail on Proposition 98 and how it would be changed by Proposition 76, please see the appendix of this report.

|

Figure 5 Proposition 98 Provisions |

|

|

|

� Eliminates provisions that allow school funding to automatically slow in low-revenue years (Test 3) and automatically rebound in high-revenue years (payment of maintenance factor). |

|

� Eliminates obligation to keep track of funding gap when state provides less than the main guarantee (Test 2) through suspension or Governor’s reduction (creation of maintenance factor). |

|

�

Converts $3.8 billion in long-term obligation to

increase the annual |

|

� Eliminates current requirement that spending in excess of the guarantee in a single year raises the minimum funding guarantee in future years. |

The impact of the Proposition 98-related changes in any individual year is uncertain. For example, by removing the formulas that allow school funding to automatically fall and rise with state revenues, the changes made by this measure would result in more steady growth in the minimum guarantee. As a result:

If revenues were weak in a particular year, the effect of the changes would be a higher minimum guarantee, since the less-generous Test 3 formula would no longer be operative.

However, if revenues were strong in a particular year, then the effect of these changes would be a lower guarantee for schools, since the state would no longer be required to restore the maintenance factor (currently $3.8 billion).

This measure would result in a lower minimum guarantee for K-14 education compared with existing law, for three reasons:

First, the state would no longer have to eventually restore the current maintenance factor obligation ($3.8 billion).

Second, any time in the future that the state suspended the minimum guarantee or the Governor reduced school spending during a fiscal emergency, the guarantee would be permanently lowered.

Third, any time in the future that the state spent above the guarantee, that additional spending would no longer increase the minimum guarantee for future years.

A lower guarantee does not mean that actual spending for schools would necessarily be lower. Policymakers would still be free to spend more than required by the minimum guarantee in any given year. Since spending above the guarantee would no longer become a permanent augmentation, future Legislatures and Governors might be more likely to spend above the minimum guarantee in a given year. Overall, the measure’s Proposition 98-related changes would result in the annual budgets for K-14 education being more subject to annual funding decisions by state policymakers and less affected by the minimum guarantee.

However, while the Proposition 98-related changes, by themselves, would not necessarily reduce K-14 education spending, other provisions of the measure might have that effect. To the extent, for example, that the measure constrains overall state spending, budget reductions resulting from the spending limit or the Governor’s new authority could apply to schools.

We believe that some elements of the measure would have a substantial impact on budget deliberations in 2006-07.

State Faces Major Budget Shortfall in 2006-07. As background, we estimate that General Fund revenues will total about $88 billion or $6 billion less than the $94 billion that would be required to maintain current-law spending requirements. Thus, policymakers will be faced with a significant budget shortfall in 2006-07 that requires corrective action.

Provisions Expanding Governor’s Powers and Changing Proposition 98 Could Have Impact. We believe that the provision granting the Governor authority to unilaterally reduce spending could have a substantial impact on how the 2006-07 budget shortfall is addressed. The Governor would have greater control over both the general nature of the solutions (for example, tax increases versus spending reductions) as well as the specific programs that would be reduced in order to balance the budget.

Also, the provision making spending above the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee one-time in nature could have an impact on budget deliberations in 2006-07. This is because the state is spending $740 million more than required by the minimum guarantee in 2005-06. Under existing law, this amount will raise the minimum guarantee in 2006-07 and future years by an equivalent amount. If Proposition 76 were to pass, the $740 million would become a one-time payment, and the minimum guarantee would be reduced by $740 million relative to current law.

Proposed Spending Limit Not Major Factor Next Year. While we would expect the proposed spending limit to have substantial effects on budgeting over the longer-term, we do not expect it would be a factor in 2006-07-its first year of implementation. Based on recent strong revenue growth and the level of spending in 2005-06, we estimate that the limit would exceed both revenues and current-law expenditures during the year. This implies that policymakers could address the shortfall through any combination of expenditure reductions and revenue increases.

In any individual year, the effects would depend on circumstances surrounding the budget and the policy choices of the Governor and Legislature. However, we believe that over time, the spending limit and expanded authority to the Governor would have the effect of reducing state spending (see Figure 6). The lower spending could apply to all major state programs, including education, health, social services, and criminal justice. The reductions could also increase costs to local governments, mostly counties. Finally, the enhanced powers of the Governor could result in a change in mix of expenditures relative to current law. That is, the allocation of spending among programs could be more consistent with the Governor’s priorities and less reflective of legislative priorities than is the case under current law.

|

Figure 6 Combined Effects of Proposition 76 |

|

|

|

� Effects on Spending |

|

� The additional spending limit and new powers granted to the Governor would likely reduce state spending over time relative to current law. These reductions also could shift costs to local governments (primarily counties). |

|

�

The new limit could also “smooth out” state spending

over time, |

|

�

The new spending-reduction authority given to the

Governor and other provisions of the measure could result in a

different mix of state |

|

� Effects on Schools |

|

� The provisions changing school funding formulas would make school funding more subject to annual decisions of state policymakers and less affected by a constitutional funding guarantee. |

|

�

Budget reductions resulting from the spending limit or

Governor’s |

These effects could be dampened to the extent that the state were able to accumulate much larger reserves than it has in the past. These reserves could reduce the required amount of spending reductions during low-revenue periods and result in a smoother pattern of spending over time.

|

Appendix How Proposition 76

Would Change School Spending Guarantee for |

|

How Current Guarantee Works |

|

� Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee. Is based on the operation of three formulas (“tests”). The operative test depends on how the economy and General Fund revenues grow from year to year. |

|

Test 1—Share of General Fund. Provides 39 percent of General Fund revenues. This test has not been operative since 1988‑89. |

|

Test 2—Growth in Per Capita Personal Income. Increases prior-year funding by growth in attendance and per-capita personal income. This test is generally operative in years with normal-to-strong General Fund revenue growth. |

|

Test 3—Growth in General Fund Revenues. Increases prior-year funding by growth in attendance and per-capita General Fund revenues. Generally, this test is operative when General Fund revenues fall or grow slowly. |

|

� Suspension of Proposition 98. This can occur through the enactment of legislation passed with a two-thirds vote of each house of the Legislature, and funding can be set at any level. |

|

� Long-Term Target Funding Level. This would be the K-14 education funding level if it were always funded according to the provisions of Test 2. Whenever Proposition 98 funding falls below that year’s Test 2 level, either because of suspension of the guarantee or the operation of Test 3, the Test 2 level is “tracked” and serves as a target level to which K-14 education funding will be restored when revenues improve. |

|

� Maintenance Factor. This is created whenever actual funding falls below the Test 2 level. The maintenance factor is equal to the difference between actual funding and the long-term target amount. Currently, the K-14 funding level is $3.8 billion less than the long-term target funding level—that is, the current outstanding maintenance factor is $3.8 billion. |

|

� Restoration of Maintenance Factor. This occurs when school funding rises back up toward the long-term target funding level. Restoration can occur either through a formula that requires higher K-14 education funding in years with strong General Fund revenue growth, or through legislative appropriations above the minimum guarantee. |

|

What This Measure Does |

|

� Eliminates Future Operation of Test 3. In low-revenue years, the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee would no longer automatically fall below the Test 2 level. |

|

� Eliminates Future Creation of Maintenance Factor. If in any given year K-14 education was funded at a level less than that required by Test 2 (through suspension or Governor’s reductions), there would no longer be a future obligation to restore that funding shortfall to the long-term target. These reductions would permanently “ratchet down” the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. |

|

� Converts Outstanding Maintenance Factor to One-Time Obligation. The measure converts the outstanding maintenance factor (estimated to be $3.8 billion) to a one-time obligation. Payments to fulfill this obligation would be made over the next 15 years. These payments would not raise the future Proposition 98 minimum guarantee (in contrast to existing law). |

|

� Counts Future Appropriations Above the Minimum Guarantee as One-Time Payments. Spending above the minimum guarantee would not raise the base from which future guarantees are calculated. |

The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office

which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the

Legislature. To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail

subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at

www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000,

Sacramento, CA 95814.

Acknowledgments

LAO Publications

Return to LAO Home Page