January 26, 2006

In 2004, we published A Look at the Progress of English Learner Students, which analyzed the 2002 results of the California English Language Development Test (CELDT). This update assesses student performance on the test in 2003 and 2004, concluding that gains made by students in 2003 and 2004 are roughly the same as 2002. We also make two recommendations for steps the Legislature can take to improve the way CELDT data are used.

In February 2004, we published A Look at the Progress of English Learner Students, which evaluated the performance of English learner (EL) students on the California English Language Development Test (CELDT) in 2002. Since we issued our report, the California Department of Education (CDE) released the results of the CELDT for 2003 and 2004. The department�s analysis of the 2004 data indicated that EL students were making significant gains in English fluency. According to CDE, these gains-an increase in the proportion of EL students that scored in the two highest performance levels-are evidence that students are learning English more quickly than in the past.

This update compares the CELDT results from 2002 through 2004 and assesses whether student performance in 2003 and 2004 improved compared to 2002. Our analysis reveals a much more complex story than suggested by CDE. On the whole, we conclude that gains made by students in 2003 and 2004 are similar to those in 2002. Indeed, our review shows that CDE�s analysis of CELDT scores fails to accurately characterize the results.

We make two recommendations to the Legislature. First, we recommend the Legislature require the department to submit an annual report on each year�s scores that focuses on gains in English proficiency achieved by students during the previous year. Second, we suggest the Legislature direct the State Board of Education and CDE to revise one of the state�s current performance measures for EL students under the federal Title II program so it focuses on gains in English fluency and is not affected by local reclassification standards.

Our previous report examined the gains in English proficiency made by EL students between 2001 and 2002 as measured by the CELDT. Unlike other state K-12 tests, student-level data on CELDT contains both the current year and the previous year�s score. By comparing each student�s scores for the two years, we measured the growth in English proficiency during the 2001-02 school year.

The CELDT measures a student�s English proficiency in listening, speaking, reading, and writing. All K-12 students identified as EL take the test each fall. The CELDT uses a five-level scale to report scores, with a level 1 indicating a beginning level of proficiency and a level 5 indicating advanced English skills. A score of 4 or 5 signals a student may be ready to be reclassified as �fluent� (see the box for an explanation of the reclassification process).

Reclassification-State Law and GuidelinesReclassification Process. English learners are reclassified as �fluent� when they have sufficient English skills to learn in a regular classroom without extra assistance and perform in academic subjects at approximately �grade level.� State law requires districts to include four types of information in the reclassification decision: results from the California English Language Development Test (CELDT) and Standardized Testing and Reporting (STAR) examinations and parental and teacher input about the readiness of a student for reclassification. State Guidelines. State law required the State Board of Education to issue guidelines for districts in the use of CELDT and STAR results in the reclassification process. In 2002, the State Board adopted the following guidelines.

Locally Adopted Criteria. Districts may adopt local reclassification standards that differ from the State Board�s guidelines. Districts may set higher or lower minimum scores on CELDT and STAR. In addition, districts may include other forms of evidence, such as grades or scores on other tests, as part of the reclassification decision. |

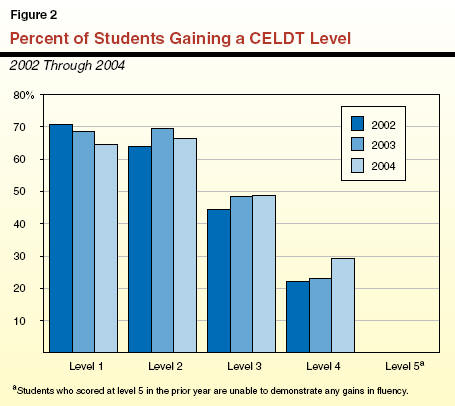

Our first report found that about 40�percent of all EL students improved their CELDT score in 2002 by at least one proficiency level. The proportion of students gaining a level was highest at the earlier stages of learning-70�percent of students scoring level 1 in 2001 improved their score by at least one level in 2002. Only about one-fifth of students scoring in level 4 during 2001 reached a level 5 in 2002.

We also used these gains to estimate the amount of time it would take a student who began kindergarten as an EL student to be reclassified as fluent and no longer designated as an EL. Since the reclassification decision involves each student�s English proficiency and level of academic skills, the CELDT provides only part of the information needed to make this estimate. Using data from CELDT, the Standardized Testing and Reporting (STAR) program, and other sources, we estimated that by sixth grade, one-half of all EL students who began school in California as kindergarteners would be reclassified.

From these findings, we concluded that the progress of EL students in mastering English was too slow. Students who are still learning English in grades 4 through 6 risk falling behind in school by failing to master the skills needed for success in middle and high school. Some groups of EL students, however, make very rapid progress. This suggests that the state should focus on learning about the mix of education services that helps particular groups of students master English more quickly.

Figure�1 shows the proportion of students achieving at each CELDT performance level in 2002 through 2004. In 2002, 29�percent of students scored in the beginning levels (levels 1 or 2), 37�percent scored at the intermediate level (level 3) and about 35�percent scored at the advanced levels (levels 4 or 5). Each year, the proportion of students scoring at levels 1 or 2 has declined and the percentage in levels 4 or 5 has increased. For example, 47�percent of students scored at level 4 or 5 in 2004-about 5�percentage points higher than in 2003 and 12�percentage points higher than 2002.

Gains in the proportion of students scoring at the two highest performance levels is used by CDE as evidence of positive results for 2004. The analysis is straightforward-more students are scoring at levels 4 or 5 than in 2003; therefore, EL students are exhibiting greater mastery of English. There is, however, a second possible explanation for this increase-students are taking longer to establish the academic skills students must have to be reclassified as fluent. By staying an EL for a longer period of time, there would be a �buildup� of EL students who are proficient in English (scoring at levels 4 or 5) but who are working to improve their academic skills.

Such a build-up of students may have been caused by policy changes affecting the reclassification of students that occurred along with the implementation of CELDT and STAR. The reclassification process is designed to ensure that students master English and possess academic skills that are comparable to their English-speaking peers before they are considered fluent. Prior to CELDT and STAR, districts chose local assessments and set local standards for assessing whether students were ready to be reclassified.

State law requires districts to use both CELDT and STAR data (when they became available) in the reclassification process (as well as parent and teacher input). The state also required the State Board of Education to establish guidelines for the use of the testing data for reclassification. In 2002, the state board recommended districts review a student for reclassification when the student scores at level 4 or 5 on CELDT and scores in the low- to mid- �basic� level on the STAR English language arts (ELA) test. (Basic is the middle performance level out of five levels.)

The board�s action led districts to revise local reclassification criteria. If this review resulted in higher standards in many districts, it seems likely that EL students would need more time than in the past to develop the skills needed to reach fluency. Unfortunately, there are no available data to determine whether the board�s guidelines raised reclassification standards statewide.

A recent report by the Bureau of State Audits (BSA) published in June 2005 indicates that districts have adopted reclassification requirements that meet or exceed the state�s suggested criteria. Districts adopting a higher standard than recommended by the board may require students, for example, to achieve a higher CELDT score, a higher score on the STAR ELA test, a specified test score on the STAR mathematics test, or minimum grade levels in specific courses.

In sum, it is not readily apparent whether the growth in the proportion of students scoring at levels 4 and 5 on CELDT is the result of more rapid acquisition of English or the result of higher reclassification standards put in place after the State Board of Education issued its guidelines in 2002. To determine the impact of the two possibilities, we have to go beyond the data in Figure�1. First, we review year-to-year gains in student progress on CELDT to directly measure gains on the CELDT. Then we take a closer look at fourth-grade CELDT scores to look for evidence of a buildup of higher performing EL students.

As noted above, the CELDT allows a unique opportunity to measure the progress of individual EL students in learning English because the results contain the current- and prior-year scores of each student. Overall, the data suggest that CELDT gains have stayed relatively constant from 2002 to 2004. In 2002, 38�percent of all EL students tested gained at least one performance level on the CELDT. The proportion increased to 43�percent in 2003 but then fell to 39�percent in 2004.

Figure�2 displays the percent of students in each performance level who gained a level on CELDT compared to their previous year�s score. Beginning students make rapid gains-about 60�percent to 70�percent of students in level 1 gain a level each year. More-advanced students take more time to show progress on the test. For instance, only 20�percent to 30�percent of students in level 4 show a similar gain. Student gains on the CELDT appear roughly similar in all three years, although 2003 and 2004 show a slightly higher percentage of students making gains in most levels compared to 2002. Only students in level 1 made less progress in 2003 and 2004 than in 2002. On the other hand, students in level 4 were much more likely to improve to level 5 in 2004 than in the prior two years. On the whole, Figure�2 suggests that student gains on CELDT have been roughly consistent over the past three years.

How can the increase in the number of students scoring at high levels be explained when the gains students make are similar or improving only slightly? This would occur if students were staying on EL for a longer period of time, resulting in a buildup of higher performing EL students. To look for evidence of this build-up, we examined the previous year�s CELDT score for students taking the exam in 2002 through 2004. That is, we looked for evidence that an increasing number of EL students who scored a 4 or 5 on CELDT continued to be classified as EL in the subsequent year.

Figure�3 shows the percent of fourth grade students scoring at level 4 or 5 for 2002 through 2004. For each year, the figure shows the proportion of students who reached a level 4 or 5 for the first time in the fourth grade (by gaining a level) and the number who had reached those levels as a third grader (and maintained that level in fourth grade). Over the three years, the total number of students scoring at levels 4 or 5 increased modestly-from 44�percent to 45�percent. This growth occurs because of the increase in the percentage of students who had achieved a 4 or 5 as third grade students. In fact, the proportion of students scoring a 4 or 5 for the first time as fourth graders actually fell in both 2003 and 2004.

The data in Figure�3 suggest a buildup of higher performing EL students in the CELDT results. By looking only at the number of students achieving a level 4 or 5 for the current-year test results, the data suggest students are doing better on the test each year-that the number of high-achieving students is increasing because of greater gains in proficiency. The prior-year scores, however, show that many of these students were already achieving at these levels and the gains in the numbers at the highest levels are actually diminishing. The data shown in Figure�3 for the fourth grade is typical of the buildup of students in levels 4 and 5 in most other grades. So the increase in the number of students scoring at level 4 and 5 may reflect changes in reclassification policies, and not an improvement in EL achievement.

Our review of the 2003 and 2004 CELDT data shows fairly minor differences in student performance compared to the 2002 test. While the proportion of students scoring in the advanced performance levels increased in 2003 and 2004, the increase appears to be caused by a buildup of students who have mastered English (as measured by CELDT) but have not achieved the academic skills necessary to be reclassified as fluent. Our analysis also shows that CDE�s analysis of the CELDT scores leads to incorrect conclusions. The increase in the number of students scoring at levels 4 or 5 does not necessarily represent progress.

The CELDT results present a data analysis challenge. Because the population taking the test changes each year as students are reclassified and new students arrive, careful analysis is required to accurately understand the progress of students. It is critical that the Legislature obtain accurate information on this important assessment. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature require CDE to submit an in-depth analysis of each year�s CELDT scores that describes the gains made by students and explores the reasons for the observed changes.

The buildup of students in levels 4 and 5 has important implications for state policy because the CELDT data are used to satisfy federal accountability requirements as part of Title III of the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act. Title III provides funding to school districts for services that help EL students learn English. The act also holds districts accountable for ensuring that EL students make progress towards English fluency by establishing several performance measures or �Annual Measurable Objectives� (AMOs) for the program. The State Board of Education approved three Title III AMOs for California, as follows:

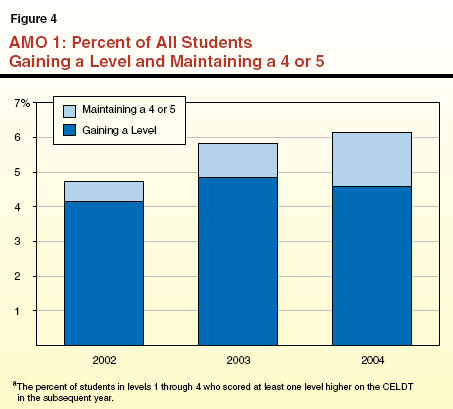

AMO 1: Annual Progress. This measure is based on the percentage of EL students in each district that gain at least one level on CELDT or that attain a score of 4 or 5 on CELDT and continue achieving at that level. In 2004, 51.5�percent of students had to show annual progress on CELDT to satisfy this accountability measure.

AMO 2: English Proficiency. This measure captures the proportion of EL students who score a 4 or 5 on CELDT for the first time. The performance target for AMO 2 was 30.7�percent for 2004.

AMO 3: Proficient on State Standards. This outcome is defined as the percentage of EL students (and fluent students for two years after they are reclassified) who meet state standards on the STAR English and mathematics tests (that is, they score at the �proficient� or �advanced� level). This measure is identical with the Title 1 �annual yearly progress� measure. Performance targets depend on the subject area and grade level.

While we believe that AMO 2 and AMO 3 effectively hold school districts accountable, we are concerned that AMO 1 may create unintended consequences.

The buildup of higher performing EL students is causing AMO 1 to report misleading results. The measure is designed to reflect the progress of EL students in mastering English. By including students who scored at levels 4 and 5 on the CELDT in both the current and previous year, however, AMO 1 can actually reward districts that delay the reclassification of students.

For example, districts that adopt high academic standards for reclassifying students will have a relatively large number of students scoring at levels 4 and 5 while they work to improve their academic skills to meet the districts� reclassification criteria. In districts with lower reclassification standards, a portion of these students would be reclassified. As a result, a district with high standards has a larger proportion of students scoring a 4 or 5 on CELDT simply because of its reclassification policy. All other things being equal, a high-standards district will also have a higher score on AMO 1 for this reason.

The issue is not whether high reclassification standards represent the appropriate local policy. Our concern is whether the definition of AMO 1 gives high-standards districts an inappropriate advantage in meeting the performance target. The BSA report on EL suggests this problem is real, finding that local reclassification standards affect a district�s success in meeting the state�s AMO 1 performance targets. Specifically, BSA found that �[s]chool districts with relatively stringent �[reclassification] criteria may find it easier to meet objective 1s [AMO 1] target for progress in learning English because they tend to have higher percentages of students who have attained proficiency on the CELDT.� As discussed above, districts may establish reclassification criteria that include higher CELDT or STAR scores than recommended by the state or include other data, such as course grades, as part of the reclassification process. The BSA found that districts that choose higher standards �appear to have larger proportions of English learners scoring at the early advanced or advanced levels [levels 4 or 5 on CELDT].� As a result, by establishing higher reclassification standards, these districts would more easily meet the performance targets in AMO 1.

Figure�4 displays the statewide data for AMO 1. As the figure shows, the proportion of EL students who gained a level or remained at levels 4 or 5 increased in 2003 and 2004. In 2004, more than 60�percent of students met one of the two criteria for success as defined by AMO 1. Figure�4 also shows the percentage of students who scored in levels 1 through 4 who gained at least one level on the CELDT in the subsequent year. This measure shows a different pattern of progress from 2002 through 2004. While the percentage of students in levels 1 through 4 increased from 41�percent to 48�percent in 2003, it fell in 2004 to below 46�percent-even though AMO 1 suggests continuing improvement that year.

These data suggest that AMO 1 does not accurately represent year-to-year progress in attaining English proficiency. We have identified three concerns with AMO 1. First, the measure fails to accurately reflect gains in English proficiency because it contains no evidence that students who maintain a score of 4 or 5 on CELDT are continuing to make progress towards fluency.

Second, local reclassification policies affect the meaning of the performance measure. The BSA findings suggest that districts with high standards have a higher proportion of students scoring in levels 4 and 5 compared to districts with more modest standards. This makes sense. A district that reclassifies EL students only when they reach state standards on STAR will have more EL students scoring at levels 4 or 5 on CELDT than a similar district that reclassifies students sooner. A district with high reclassification standards, therefore, may find it easier to meet AMO 1 than a district with lower standards.

Third, the current definition of AMO 1 rewards schools that delay reclassifying students as fluent. The BSA report also cites numerous instances where students who met all local reclassification standards were not reclassified as fluent. Districts cited many reasons-primarily administrative-for this problem. As with higher local standards, however, schools and districts that keep a larger proportion of students classified as EL for administrative reasons will tend to more successfully meet the criteria in AMO 1. Districts also have a financial incentive for keeping students classified as EL because federal Title III funds are distributed on a per EL basis, and the state Economic Impact Aid program-which is the primary source of district funding for EL services-is based in part on EL student counts. We think the annual measurable objectives can moderate the influence of these fiscal incentives by reinforcing the importance of helping students achieve gains in English fluency.

The federal requirements to create annual measurable objectives were intended to create strong incentives to ensure that EL students make consistent progress in learning English and perform at a level consistent with state academic standards. The flaws in AMO 1 undermine those incentives and may even create negative incentives to reclassify students.

For this reason, we think the Legislature should require CDE and the State Board of Education to revise AMO 1 with the aim of improving the incentives created by the targets and ensuring that the meaning of the measure is consistent across all districts. We see two options.

First, the state could develop a statewide reclassification standard that would apply to all districts. This option, proposed in the BSA report, would attempt to create a consistent reclassification policy in all districts and, therefore, would address the problem of different local standards.

The second option would revise AMO 1 so that it measures actual gains on CELDT. Similar to the data in Figure�4, it would establish performance targets based on the percentage of students gaining a level. Because students in level 5 cannot gain a level, this measure would be restricted to those students who scored in levels 1 through 4 in the prior year. Since gains on the CELDT are unaffected by a district�s reclassification policy, this option also would establish a relatively consistent measure across the state.

We think this second option is preferable. Creating a statewide reclassification policy assumes there is one �best� time to transition EL students. Indeed, the BSA report finding of different local standards and our own review of available research evidence suggests there is little agreement about when to reclassify students. Thus, lacking a research basis, any statewide standard will be somewhat arbitrary. In addition, how local educators would refashion local programs in response to a statewide policy is unknown. Because teacher and parent input would likely continue to be part of the reclassification criteria, significant local control over when to reclassify students would remain. Therefore, we recommend the Legislature direct the State Board of Education to redefine AMO 1 to reflect gains made by students who scored in levels 1 through 4 in the prior year.

Despite the difficulties in interpreting its results, the CELDT is shedding new light on a major challenge facing the state�s K-12 system-helping EL students master English and perform at levels consistent with the state�s academic goals. Because EL students constitute one-quarter of the state�s K-12 population, the Legislature needs a thorough analysis of CELDT gains and the resulting implications for state policy.

Unfortunately, CDE�s analysis of the 2003 and 2004 results does not provide an accurate picture of the gains EL students are making on CELDT. In addition, trends in the CELDT data make it clear that the federally required annual measurable objectives under Title III of NCLB have not worked as anticipated by the state department and the state board. We recommend the Legislature enact legislation to address these issues.

This report was prepared by

Paul Warren. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office

which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the

Legislature. To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail

subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at

www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000,

Sacramento, CA 95814.

Acknowledgments

LAO Publications

Return to LAO Home Page