January 19, 2006

The new federal transportation act (SAFETEA-LU), enacted in August 2005, will provide $23.4 billion in federal funds to California through 2009 for highways, transit, and transportation safety. This represents a 40 percent increase in federal funding each year for transportation over the previous federal program. In addition to increasing federal funding to the state, SAFETEA-LU presents opportunities for financing transportation through nontraditional funding sources and expediting project delivery. There are a number of issues for the Legislature to consider when implementing the act in California. We discuss these issues and make recommendations where further legislative actions are warranted.

In October 2003, the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21) expired. This act had provided federal transportation funding from 1998 through 2003, financing highway and transit projects nationwide through a combination of formula, discretionary, and earmarked funds. The act also allowed transportation agencies to shift formula funds from one grant category to another with few restrictions, thereby providing a flexible source of federal funding for transportation projects.

Congress failed to reauthorize a multiyear transportation program in 2003. Instead, it extended TEA-21 for almost two years to provide continued funding for transportation. However, on August 10, 2005, Congress reauthorized the federal transportation program through 2009 by enacting the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU).

This report summarizes the major provisions of the new federal act, highlights how they differ from TEA-21, and discusses the act�s implications for California. The report then identifies the main issues that the Legislature should consider and where further legislative actions are warranted to facilitate implementation of SAFETEA-LU in California.

Figure�1 highlights the major provisions of SAFETEA-LU. This section discusses these provisions in detail and compares national funding levels under SAFETEA-LU and TEA-21. (See a glossary at the end of this report for descriptions of various acronyms and terms used throughout the report).

|

Figure 1 The Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users |

|

Major Provisions |

|

General: |

|

Maintains overall structure of previous transportation act (TEA-21), but increases emphasis on safety. |

|

Continues TEA-21�s flexibility allowing up to 50 percent of most program formula funds to be redirected. |

|

Funding Nationwide: |

|

Provides 42 percent increase in average annual funding over TEA-21. Authorization of $241 billion for fiscal years 2005 through 2009 includes $190 billion for highways, $45 billion for transit, and $5.7 billion for safety enhancements. |

|

Earmarks over $26 billion worth of congressionally specified projects, including $14.8 billion for High Priority Projects and $1.8 billion for Projects of National and Regional Significance. |

|

Highways: |

|

Guarantees �donor states� a minimum of 90.5 percent return on state fuel tax contributions in 2005 and 2006, 91.5 percent in 2007, and 92.0 percent in 2008 and 2009. |

|

Provides incentives for private sector participation in construction of major transportation facilities. |

|

Pilots include: federal delegation of environmental review responsibilities to states and toll programs on interstate highways. |

|

Transit: |

|

Most discretionary funds remain available for competitive project applications. |

|

Provides capital funding for smaller transit projects requiring less than $75 million in federal funds. |

Program Structure Relatively Unchanged, but Increases Focus on Safety. As with TEA-21, the new act directs federal funding for highways and transit. In the highway program, there continues to be six major formula funding categories-Interstate Maintenance, National Highway System, Congestion Mitigation/Air Quality Improvement (CMAQ), Surface Transportation Program (STP), Bridges, and Equity Bonus (known as Minimum Guarantee under TEA-21). In the transit program, a mixture of formula and discretionary grants is provided through the Urban Formula, Fixed Guideway Modernization, New Starts, and High Priority Bus categories.

The new act differs from TEA-21 by increasing the focus on safety. In addition to augmenting funding levels to previously established safety programs, SAFETEA-LU introduces new discretionary and formula grants aimed at reducing travel-related hazards through increased law enforcement and safety-related planning. The act increases the total authorization for highway safety programs to $5.7�billion from $3.3�billion under TEA-21. New federal safety grant programs include Highway Safety Improvement, High Risk Rural Roads, Safety Belt Performance Grants, and Safe Routes to School.

Overall Funding Level Increases Relative to TEA-21. The act authorizes $286�billion nationwide for transportation over the six-year period from 2004 through 2009. However, due to the delay in reauthorization, about $45�billion was expended by the time SAFETEA-LU was enacted. Thus, between 2005 and 2009, funding will be closer to $241�billion with $190�billion for highways, $45�billion for transit, and $5.7�billion for safety improvements. This represents approximately a 40�percent increase in average annual funding over TEA-21, with the ratio of transit to highway funds relatively unchanged.

Substantial Increase in Earmarks. The act earmarks over $26�billion for more than 6,000 projects nationwide. These projects are specified in various discretionary programs including ones that existed under TEA-21-High Priority Projects (HPP), New Starts, and High Priority Bus-as well as new programs-Projects of National and Regional Significance (PNRS), National Corridor Infrastructure Improvement (NCIIP), and Transportation Improvements (TI). The earmarked amount is a substantial increase over the $9.3�billion earmarked in TEA-21 for about 1,850 projects exclusively in the HPP program.

Formula Funds Remain Flexible, Discretionary Funds Less So. Similar to TEA-21, the new federal act provides both formula-based funds and discretionary funds. As with TEA-21, SAFETEA-LU provides the state with considerable flexibility in the use of formula funds, which account for 80�percent of total funds authorized in the act. Specifically, state and regional agencies can move up to 50�percent of funds from one formula category to another subject to various restrictions. For example, a state may transfer up to half of its CMAQ apportionment to projects eligible for Interstate Maintenance, National Highway System, STP, Bridges, or Recreational Trails grants. Furthermore, funds provided under STP and Equity Bonus-two of the largest funding categories, making up 30�percent of the $241�billion distributed through 2009-can be used for a wide variety of projects including transit, highway, local road, bridge, safety, and transportation enhancement projects at states� discretion.

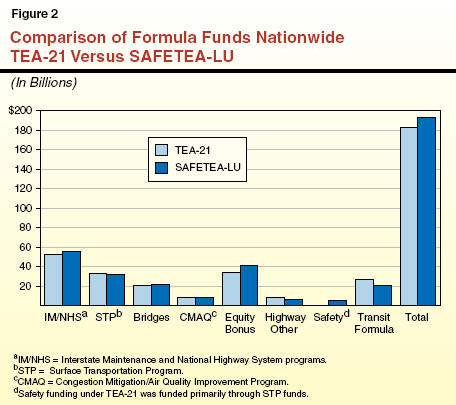

Though formula grants are a flexible source of funding to meet diverse transportation needs, the new act only increases these funds by a modest amount. As Figure�2 shows, total funding to formula grant categories increased by $10�billion, or 5�percent, over TEA-21 levels.

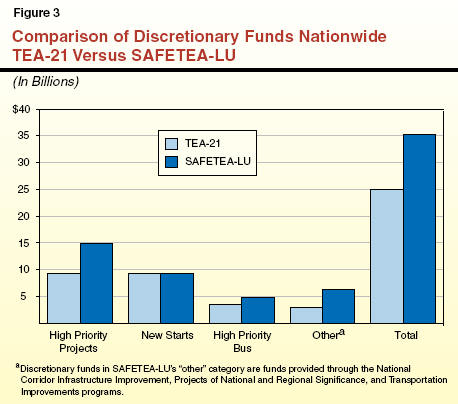

In contrast, Figure�3 shows that SAFETEA-LU provides about $35�billion in discretionary funding nationwide-about 40�percent more than the amount under TEA-21. In particular, funding for the HPP program increases from $9.3�billion to $14.8�billion. The act also creates three new discretionary grant programs for NCIIP, PNRS, and TI.

Compared to formula funds, discretionary grants are considerably less flexible. This is because many discretionary grants are nontransferable among fund categories. For example, HPP funds cannot be applied toward NCIIP projects (included in �other� programs in Figure�3). Further intensifying this rigidity is the fact that four of the major discretionary fund categories (HPP, PNRS, NCIIP, and TI) are completely earmarked for specified projects. This means that there are no funds left over in these four categories for additional, nonearmarked projects.

Moreover, for a large number of specifically earmarked projects, the designated funding cannot be redirected to other projects. This further limits states� ability to direct funding to projects they deem to be of high priority within each fund category.

Equity Bonus Program Beneficial to Donor States. The Equity Bonus program (which is the equivalent to TEA-21�s Minimum Guarantee program) ensures each state a minimum rate of return on its share of fuel tax contributions to the federal highway trust fund. States will receive in 2005 and 2006 a minimum level of funding equivalent to 90.5�percent of their fuel tax contributions-the same rate as guaranteed under TEA-21. The rate will increase to 91.5�percent in 2007 and to 92�percent in 2008. This represents an increase in return for donor states like California, which sends more fuel tax revenues to the federal government than it receives back. Equity Bonus funds may be used for any transportation project eligible for funding under other major highway formula programs.

Highway and Safety Funds Potentially More Reliable. Under TEA-21, funding levels for highway and safety programs were adjusted when revenues to the federal highway trust fund (HTF) fluctuated. Because fuel excise tax revenues to the HTF were lower than projected in 2003, for example, this resulted in a downward fund adjustment to many highway and safety programs. However, under the new federal act, funding to highway and safety programs would not be reduced when tax revenues decline so long as the HTF balance exceeds $6�billion. This would provide more certainty to states regarding the level of highway and safety funding to be received. However, it is estimated that the trust fund�s balance will be below $6�billion in the last two years of SAFETEA-LU. As a consequence, highway and safety programs would likely still experience downward fund adjustments if revenues to the HTF are lower than projected. Transit funding is unaffected by this provision, as transit funds have always been exempt from revenue adjustments.

Other Provisions. In addition to changes already discussed, SAFETEA-LU includes a number of provisions that influence the way that transportation facilities are planned, built, and administered. Specifically, the act encourages private investments and partnerships in constructing transportation infrastructure, in addition to providing opportunities for environmental streamlining, design-build contracting, and toll road projects.

The new federal act has a number of implications for California�s transportation program. The key implications are highlighted in Figure�4, and are further discussed in this section.

|

Figure 4 SAFETEA-LU: Key Implications for California |

|

|

|

Funding/Financing |

|

» Overall funding to state increases. |

|

» High level of earmarks a mixed blessing. |

|

» New program funding benefits goods movement. |

|

» Innovative finance options expanded, but state law does not provide for use. |

|

» Toll road project opportunities expanded. |

|

Project Delivery |

|

» Design-build restrictions relaxed, but state law requires design-bid-build. |

|

» Environmental streamlining opportunities offered, but at additional cost and potential state liability. |

|

Programmatic Changes |

|

» Regions achieving air quality conformity raise Congestion Mitigation/ Air Quality Improvement fund distribution issues. |

|

» Safety programs provide additional funding, but may be subject to implementation hurdles. |

|

» Hybrids allowed to utilize high occupancy vehicle lanes. |

|

» Changes to transit program could benefit state. |

Overall Funding to State Increases. California�s apportionment of federal transportation funds under SAFETEA-LU will be substantially higher than under TEA-21. This is because of both the increase in the nationwide funding authorization and the higher rate of return to donor states on fuel tax contributions. According to the Department of Transportation (Caltrans) and federal estimates, the act will provide $23.4�billion in transportation funds to California from 2005 through 2009. Of this amount, about $18�billion will go to highways, $5�billion will go to transit, and $452�million will go to safety improvements. This represents a 40�percent increase in average annual funding over TEA-21. Figure�5 compares average annual funding for California by mode under the two acts. As the figure shows, average annual highway authorizations are 44�percent higher and average annual transit authorizations will grow by a third over the span of SAFETEA-LU.

Figure�6 shows California�s authorized funding by program. Funding for highways will account for 76�percent of all funding allocated to California, with six major formula grant programs (including Interstate Maintenance, National Highway System, STP, Bridges, CMAQ, and Equity Bonus) comprising the majority ($15�billion) of highway funding. Of the remaining $3�billion in the state�s highway allocation, $2.4�billion comes from earmarks in the HPP, PNRS, NCIIP, and TI programs with the remainder from smaller highway grants.

|

Figure 6 SAFETEA-LU Program Funding in California 2005 Through 2009a |

|

|

(In Millions) |

|

|

Highways |

$17,834 |

|

Surface Transportation |

$3,200 |

|

Equity Bonus |

3,200 |

|

National Highway System |

2,800 |

|

Interstate Maintenance |

2,200 |

|

Bridges |

1,900 |

|

Congestion Mitigation/Air Quality Improvement |

1,800 |

|

High Priority Projects |

1,200 |

|

National Corridor Infrastructure Improvement Program |

660 |

|

Projects of National and Regional Significance |

450 |

|

Metropolitan Planning |

221 |

|

Coordinated Border Infrastructure |

106 |

|

Transportation Improvements |

97 |

|

Transit |

$5,145 |

|

Urbanized Area Formula |

$2,700 |

|

New Starts |

1,100 |

|

Fixed Guideway Modernization |

821 |

|

Discretionary Bus |

195 |

|

Jobs Access/Reverse Commute |

86 |

|

Non-Urbanized Area Formula |

85 |

|

Metropolitan Planning |

54 |

|

Elderly and Disabled Operating Assistance |

52 |

|

New Freedoms |

42 |

|

State Planning |

10 |

|

Safety |

$452 |

|

Highway Safety Improvement Program |

$384 |

|

Safe Routes to School |

68 |

|

Total |

$23,431 |

|

|

|

|

a Transit funding authorization estimated by the Federal Transit Administration for 2006 through 2009 only. |

|

California will receive about $5�billion for transit purposes. This amount includes $3.9�billion in formula grant programs, including mainly Urbanized Area formula and Fixed Guideway Modernization, and roughly $1.3�billion earmarked in discretionary grants. The total transit funding level represents 22�percent of California�s total transportation funding allocation under SAFETEA-LU. This share, however, could increase as the state applies for and receives additional funding for transit projects from discretionary programs like High Priority Bus and New Starts.

While SAFETEA-LU creates and expands safety grant programs, these programs account for a relatively small portion of the total funding authorization to the state. The majority of the state�s safety funds will come from the Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP), which provides $384�million for statewide safety-related data collection, infrastructure improvement, and administration of safety programs. The federal Safe Routes to School Program (SRTS) will provide a total of $68�million for safety improvements on the transportation network serving schools.

High Level of Earmarks a Mixed Blessing. Under SAFETEA-LU, California is a major recipient of earmarked funds from the HPP, PNRS, NCIIP, High Priority Bus, and New Starts programs. Figure�7 shows that $3.7�billion (16�percent) of California�s $23.4�billion authorization is earmarked for specific projects. This more than quadruples the total amount of earmarked funds received by the state ($877�million) under TEA-21.

|

Figure 7 Authorized Funding for California |

|||

|

(In Billions) |

|||

|

|

Formula |

Earmarks |

Totals |

|

Highway |

$15.4 |

$2.4 |

$17.8 |

|

Transit |

3.9 |

1.3 |

5.2 |

|

Safety |

0.4 |

— |

0.4 |

|

Totals |

$19.7 |

$3.7 |

$23.4 |

Figure�8 shows that $2.5�billion-about two-thirds-of the state�s earmarked funds are associated with large highway, transit, and goods movement projects. While only three projects in California received more than $20�million in earmarked funds under TEA-21, SAFETEA-LU authorizes $20�million or more for each of 24 projects around the state.

|

Figure 8 California Earmarked Projects Valued at $20 Million or More |

|||

|

(In Millions) |

|||

|

Project |

County |

Source |

Earmark Amount |

|

Metro Gold Line Eastside Extension |

Los Angeles |

New Starts |

$406 |

|

Centennial Corridor Loop |

Kern |

NCIIPa |

330 |

|

BART Extension |

San Francisco |

New Starts |

280 |

|

Mission Valley East Extension |

San Diego |

New Starts |

153 |

|

Bakersfield Beltway |

Kern |

PNRSc |

140 |

|

Alameda Corridor East |

SCAGb Region |

PNRS |

125 |

|

Oceanside Escondido Rail Corridor |

San Diego |

New Starts |

114 |

|

SR-178 Bakersfield |

Kern |

NCIIP |

100 |

|

Gerald Desmond Bridge |

Los Angeles |

PNRS |

100 |

|

I-405 high occupancy vehicle (HOV) lane |

Los Angeles |

NCIIP |

100 |

|

Widen a state route between San Luis Obispo County Line and I-5 |

Kern |

HPPd |

92 |

|

Mission Valley East Extension |

San Diego |

New Starts |

89 |

|

Widen Rosedale Highway |

Kern |

NCIIP |

60 |

|

Inland Empire Goods Movement Gateway |

San Bernardino |

PNRS |

55 |

|

Increase capacity on I-80 |

Placer |

NCIIP |

50 |

|

Golden Gate Bridge |

San Francisco |

Highway Bridge |

50 |

|

Widen SR-46 |

San Luis Obispo |

HPP |

33 |

|

Widen I-405 for HOV lane |

Los Angeles |

TIe |

30 |

|

Alameda Corridor East |

SCAG Region |

TI |

30 |

|

Transbay Terminal |

San Francisco |

PNRS |

27 |

|

Nonmotorized Transportation Pilot Program |

Marin |

Nonmotorized Pilot |

25 |

|

Increase capacity on I-80 |

Placer |

HPP |

22 |

|

SR-4 East Upgrade |

Contra Costa |

NCIIP |

20 |

|

Inland Empire Goods Movement Gateway |

San Bernardino |

HPP |

20 |

|

Total of earmarks at or exceeding $20 million each |

|

$2,452 |

|

|

Total of earmarks less than $20 million each |

|

$1,271 |

|

|

Total California earmarks |

|

$3,723 |

|

|

|

|||

|

a National Corridor Infrastructure Improvement Program. |

|||

|

b Southern California Association of Governments—Region includes Imperial, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and Ventura Counties. |

|||

|

c Projects of National and Regional Significance. |

|||

|

d High Priority Projects. |

|||

|

e Transportation Improvements. |

|||

A number of SAFETEA-LU�s earmarked funds assist projects that are high in statewide priority. However, other earmarks are tied to projects that are less crucial from the state�s perspective. While earmarked funds infuse the state with federal dollars, these grants are not as flexible as formula funds. Specifically, the state has little discretion to redirect earmarked funds to other projects that it may deem to have higher priority. About 60�percent of California�s earmarked funds are devoted to specified projects and cannot be transferred to other priorities. For example, the $5.8�million provided in HPP funds for a mountain hiking trail may not be used for any other purpose, even if there are alternative projects that can better address the state�s transportation needs.

Even in the other 40�percent of cases where earmarked funds can be used for other projects, the act sets limits on the extent of transfers. Specifically, transfers can only be for projects funded by the same discretionary grant program. For instance, TI earmarked funds may only be transferred to other TI earmarked projects. Additionally, there is a limit on the amount of earmarked funding that may be devoted to any given project. As a result of these two conditions, the state�s flexibility to transfer earmarked funds is quite limited. Furthermore, this limited flexibility applies primarily to a relatively small number of projects in the PNRS, NCIIP, and TI programs. Consequently, Caltrans has limited leeway in shifting funds among projects to better reflect state priorities.

In addition, earmarked amounts typically do not cover the full costs of projects. As such, state and local agencies must dedicate substantial additional funding from other sources to fully cover project costs. For example, the $130�million earmarked for carpool lanes on I-405 (in NCIIP and TI funds) does not come close to meeting full project costs, which are estimated at over $500�million. Moreover, if an earmarked project is not a state priority, dedicating other funding to fully pay for the project would further limit the state�s ability to meet higher funding priorities.

New Program Funding Benefits Goods Movement. The act establishes several new programs, including the PNRS and NCIIP programs, which target funding to projects that benefit national and international commerce. The state is a major recipient of these funds. Specifically, California will receive $450�million from PNRS for high-cost projects that improve the flow of goods and people on the national or regional scale. Major PNRS grants include $125�million for the Alameda Corridor East in Southern California and $55�million for the Inland Empire Goods Movement Gateway Project. From NCIIP, which funds projects on highway corridors of importance to national economic growth and trade, California will receive $660�million for projects in Contra Costa, Kern, and Los Angeles Counties.

In addition, SAFETEA-LU allocates $106�million in Coordinated Border Infrastructure (CBI) program funds to California. Prior to 2005, CBI was a discretionary program that provided grants for highway projects near an international border on a competitive basis. The new federal act makes CBI a formula program, allocating funds to border states based on commercial truck and private vehicle volumes, truck cargo volumes (by weight), and the number of land border ports of entry. These funds are intended to provide additional support to mobility improvement projects within 100 miles of the California-Mexico border. For California, this means that CBI funds may only be used in San Diego, Imperial, and parts of Orange and Riverside Counties and thus require a different allocation method than other federal funds flowing into the state.

Innovative Finance Options Expanded, but Current State Law Does Not Provide for Use. The new federal act expands in a number of ways the potential of using innovative financing mechanisms to fund transportation projects. Specifically, it lowers the project cost eligibility threshold for the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) program. The purpose of the program is to stimulate private investment in nationally or regionally significant surface transportation projects by providing federal credit assistance in the form of direct federal loans, loan guarantees, and lines of credit. Although public agencies can access TIFIA funds, the program�s primary mission is to entice private investment. Whereas TEA-21 restricted TIFIA funds to highway projects with costs greater than $100�million, SAFETEA-LU lowers the cost threshold to $50�million. Project eligibility has also been expanded to include international bridges and tunnels, as well as intercity passenger bus and rail projects.

The act also allows tax-exempt bonds to be used by the private sector when partnering with a public agency to construct transportation facilities. These bonds, more commonly known as �private activity bonds� (PABs), encourage private investment in transportation infrastructure by making borrowing less expensive (through paying a lower interest rate). The PABs are subject to a national cap of $15�billion, but there is no limit by state. A variety of public-private partnerships are eligible for PABs-highway, transit, rail freight projects, international bridges and tunnels managed by international entities, as well as intermodal truck-rail transfer projects. Because current state law does not provide general authority to build transportation infrastructure using public-private partnerships, the extent to which these innovative finance provisions can benefit California is limited without state statutory changes.

Toll Road Project Opportunities Expanded. The act provides expanded opportunities to charge tolls on interstate highways. In particular, SAFETEA-LU establishes the Express Lanes Demonstration program. This program allows the creation of 15 new toll projects nationwide on existing high occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes and any highway lane opened after SAFETEA-LU�s enactment. Once toll revenues cover facility construction and maintenance costs, states may use revenues for other transportation purposes. The program requires that newly tolled HOV lanes include variable pricing structures (tolls vary by time of day or congestion level) and that all toll lanes utilize automatic toll collection technologies, such as FasTrak. Caltrans notes that the I-15 HOV-toll lanes were built under a similar provision in TEA-21 and an I-680 HOV lane could potentially be included in SAFETEA-LU�s Express Lanes Demonstration.

Relaxes Design-Build Restrictions, but State Law Requires Design-Bid-Build. The new federal act eliminates the $50�million floor on the cost of projects that can be constructed using the design-build method, a delivery process that awards both the design and construction of a project to a single entity. The use of design-build to construct public projects is a relatively recent development aimed at reducing project delivery times by streamlining the design and construction processes. Most public agencies in the state have little experience using this delivery process. The new act makes virtually any project eligible to be built using design-build contracting.

With a few exemptions, state law requires public agencies to use the design-bid-build process to deliver capital projects. Under this process, public agencies typically complete the project design before advertising and awarding the construction contract through competitive bidding. Caltrans is not currently authorized to utilize the design-build method. However, SB 371 (Torlakson and Runner) and AB 508 (Richman), if enacted, would permit the department to use this project delivery process.

Offers Environmental Streamlining Opportunities, but at Additional Cost and Potential Liability. The act allows five states, including California, to participate in a pilot program that authorizes the state to assume the Federal Highway Administration�s (FHWA�s) responsibilities under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). These responsibilities include assessing a highway project�s environmental impact, preparing the required federal documentation, and consulting with federal agencies, such as the Fish and Wildlife Service, which are involved in the environmental review process. State transportation officials must decide whether and to what extent they wish to assume these environmental review responsibilities from the federal government. Figure�9 highlights potential levels of NEPA delegation that California could assume.

|

Figure 9 National Environmental Policy Act Options for Delegation of Responsibilities to State |

|

|

Option |

Description |

|

1 |

Assume responsibility for both state highway system (SHS) and local assistance projects. |

|

2 |

Assume responsibility for SHS projects only. |

|

3 |

Assume responsibility for local assistance projects only. |

|

4 |

Assume responsibility for preliminary environmental studies only. |

|

5 |

Assume responsibility for state selected projects only. |

|

6 |

Assume responsibility only for projects in select geographic areas. |

Delegation could streamline the environmental review process, reducing project delivery time. This is because the state would have more control over the pace of the environmental review process and Caltrans would communicate directly with involved federal agencies, instead of doing so indirectly, via FHWA staff. Currently, California has its own environmental review process which parallels the federal process in many aspects. Consequently, Caltrans has indicated that it believes it can assume delegation at any level it chooses, if it has the necessary staff resources to do so. However, no precedent exists for state delegation of NEPA responsibilities, thus there is no experience from which to gauge how much project delivery time could actually be saved or what the new costs to the state would be. Delegation of NEPA responsibilities represents a cost shift from the federal to state government.

Furthermore, the state should choose its level of participation with caution, as delegation means the state could be sued in federal court over its decisions. Under the U.S. Constitution, the state is currently immune from being sued in federal court. In order to participate in the pilot, California would have to waive this constitutional immunity. The additional resources that Caltrans would need to respond to lawsuits in federal court are also unknown.

Regions Achieving Air Quality Conformity Raise CMAQ Fund Distribution Issues. The CMAQ program allocates funds to states based on the severity of air quality problems and the population in air quality nonattainment and maintenance areas. The funds are spent on projects offering air quality or congestion-reduction benefits. In 2005, the federal government replaced one of the measures used in determining whether localities are in conformity with air quality standards. This change affected the air quality conformity status of four California counties (Santa Cruz, Monterey, San Benito, and Santa Barbara), which were reclassified from maintenance to attainment areas under the new standard. Because these counties are no longer considered maintenance areas, the state�s CMAQ funding level would be lower than if these counties were included in the funding calculation. Consequently, they do not contribute to California�s apportionment of CMAQ funds under SAFETEA-LU.

Federal law allows the state to continue dispersing CMAQ funds to these counties, as the reclassification reflects more of a change in definition than a measurable improvement in the counties� air quality. Current state law, however, prohibits the expenditure of CMAQ funds in air quality conformity regions. Thus, the state must decide whether it wants to continue dispersing CMAQ funds to these four counties. The level of CMAQ funding previously allocated to these regions was quite low-approximately $8�million out of the state�s $389�million apportionment in 2004-05. While the amount of CMAQ funds received by the four counties was small, how the state decides to allocate its CMAQ apportionment could set a precedent for future allocations if and when other regions reach air quality conformity.

Safety Programs Provide Additional Funding, but May Be Subject to Implementation Hurdles. The act increases the focus on safety by providing more funding for existing highway safety programs and introducing new programs that support safety improvements. In total, the state will receive about $452�million from HSIP and SRTS. In order to access all of this funding, the state must address implementation issues associated with expenditure of these funds.

To utilize HSIP funds, SAFETEA-LU requires Caltrans to prepare a Strategic Highway Safety Plan, which identifies dangerous points throughout the state�s highway and road network and identifies projects to mitigate these hazards. Caltrans must also report on the effectiveness of the safety programs it implements. Creating these documents could be relatively resource intensive as they require coordination between Caltrans and local transportation authorities. The state must meet these reporting requirements in order to receive a portion of the safety funding beyond 2007.

The act establishes a federal SRTS, a formula-based program providing grants to improve nonmotorized transportation facilities (such as bicycle lanes and sidewalk improvements) used by children traveling to school. Since 1999, the state has funded its own SRTS, using one-third of the state�s allocation of federal safety grants. Under current law, the state program will continue through 2008. While the state and federal programs share the same name and general purpose, they each have different funding rules resulting in different allocations. Furthermore, the federal SRTS would provide less average annual funding in 2006 through 2009 (about $17�million) than the state program has historically provided (about $22�million annually). The state must decide between funding the federal and state SRTSs concurrently, abandoning the state program in favor of the federal program, or adopting an alternative strategy.

Allows Hybrids to Utilize HOV Lanes. The new federal act gives the green light for low-emissions, energy-efficient vehicles with a single occupant to utilize HOV lanes, so long as these vehicles do not cause congestion in the lanes. Although current state law, Chapter�725, Statutes of 2004 (AB 2628, Pavley), has a more detailed definition of HOV lane congestion than does SAFETEA-LU, Caltrans does not perceive a conflict between the state and federal laws.

Changes to Transit Program Could Benefit State. Not only has California�s average annual transit funding authorization increased by 33�percent under SAFETEA-LU, but transit provisions in the new federal act are generally favorable to California. For instance, starting in 2007, the discretionary New Starts program will begin awarding grants to smaller transit projects requiring less than $75�million in federal funds (with total project costs not exceeding $250�million). Planned bus rapid transit and low-cost trolley projects similar to Los Angeles� Orange Line could benefit from this new source of funds.

Additionally, the new act increases funding to Fixed Guideway Modernization (FGM) and Job Access Reverse Commute (JARC) programs which provide funding for construction and improvement of transit systems. California will receive $821�million from FGM, up from $700�million under TEA-21. In addition to increasing funding to the JARC program, SAFETEA-LU makes the program formula-based, significantly improving the reliability of these funds to the state. Prior to reauthorization, California received about $10�million per year in JARC program grants that were subject to a highly subjective application process. In 2006, the state will receive approximately $19�million in formula funds from the JARC program, an annual sum that is set to increase slightly each year of SAFETEA-LU�s duration.

Above, we discussed the major implications of the new federal transportation act for California�s program through 2009. In this section, we highlight key issues that the Legislature should consider and identify areas where further legislative action is warranted for the state to implement SAFETEA-LU. Recommended legislative actions are summarized in Figure�10.

|

Figure 10 SAFETEA-LU: Recommended Legislative Actions |

|

|

|

» Direct California Transportation Commission to (1) estimate nonfederal funds required to fully finance earmarked projects and (2) identify how projects align with state and local priorities. |

|

» Create new competitive grant programs to allocate Coordinated Border Infrastructure funds. |

|

» Authorize additional public-private partnerships taking into account the state�s past experience with such arrangements. |

|

» Authorize Caltrans to use design-build contracting on a pilot basis. |

|

» Direct Caltrans to provide a cost-benefit analysis of the National Environmental Policy Act delegation authority. |

|

» Phase out Congestion Mitigation/Air Quality Improvement funding in counties attaining air quality conformity. |

|

» Maintain Safe Routes to Schools program at current state funding level. |

How Much Nonfederal Funding Is Needed to Cover Full Project Costs of Federally Earmarked Projects? How Do Earmarked Projects Align With State and Local Priorities? The new federal act earmarks about 13�percent of the state�s highway allocation and a quarter of transit funding for specified projects. In few, if any, cases do the earmarked amounts cover the full project costs. To utilize California�s allotment of earmarked funds, significant additional nonfederal funding must be made available. While a number of the earmarked projects may be high in statewide priority, others may not be. Providing all of the additional resources necessary to fully fund earmarked projects could skew the state�s transportation priorities, resulting in state funds being directed to projects which from a statewide perspective are lower in priority.

We recommend the enactment of legislation that directs the California Transportation Commission (CTC), in cooperation with Caltrans and local transportation agencies, to estimate the nonfederal funds required to fully finance the state�s earmarked projects. Additionally, the commission should provide an assessment of which earmarked projects rank higher in state priorities and which earmarks rank lower. With this information, the state would be able to make better decisions regarding the allocation of state funds for the earmarked projects.

How Should Coordinated Border Infrastructure Funds Be Allocated? The CBI funding category will provide $106�million to fund projects in four counties (San Diego, Imperial, and parts of Riverside and Orange) within 100 miles of the California-Mexico border. Under current state law, these funds would be pooled and programmed for projects in the State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) regardless of proximity to the border. Congress, however, required that CBI funds be used exclusively to enhance mobility near international borders, which precludes these funds from being commingled with STIP funds.

To expend CBI funds in a manner consistent with the federal act, we recommend the enactment of legislation specifying that CBI funds are not subject to the current state formula for allocating state and federal funding in the STIP. We further recommend allocating CBI funds in a manner consistent with SAFETEA-LU, by creating a new competitive grant program through which transportation agencies could submit CBI eligible projects for funding to be awarded by CTC. Project selection criteria could include a project�s ability to reduce congestion and facilitate goods movement between regions. These measures are already used to select projects for the Interregional Transportation Improvement Program.

Should the State Promote and Expand Public-Private Partnerships to Encourage Private Investment in Transportation Facilities? Public-private partnerships provide a means to generate private investment in the construction of transportation facilities. These partnerships often take the form of a state or local government granting a franchise to a private entity to design, construct, maintain, and operate a facility for an extended period of time. The new federal act allows the use of TIFIA credit assistance and tax-exempt PABs as incentives to induce private sector investments in transportation, by lowering their cost of investing in transportation infrastructure. Both funding sources are finite. As discussed earlier, SAFETEA-LU sets a $15�billion nationwide cap on the total PABs that can be issued for transportation projects.

In general, transportation improvements in California are funded with taxes and user fees. In 1989, the state authorized a pilot program for up to four franchises for privately built transportation under Chapter�107, Statutes of 1989 (AB 680, Baker). To date, only one project (SR-91) is operational and another (SR-125) is under development. The two other franchises authorized by Chapter�107 did not materialize. Thus, the state has limited experience with public-private partnerships.

Current state law does not authorize Caltrans to engage in additional public-private partnerships. Nonetheless, we think there is merit to allowing Caltrans to engage in public-private partnerships, as they provide a way to generate investment in the state�s transportation infrastructure from the private sector. Thus, we recommend enacting legislation to authorize additional public-private partnerships taking into account the state�s prior experience. Specifically, before enacting legislation, Caltrans should identify for the Legislature the opportunities and pitfalls the state encountered in its previous experience with public-private partnerships. The Legislature could then take this into account in the new authorization.

For California to take advantage of SAFETEA-LU�s innovative finance opportunities, timely action would be needed to provide that authority. This is because other states (such as Texas and Virginia) are already using public-private partnerships to construct large projects and they may be further ahead than California to take advantage of the limited federal financing capacity.

Should State and Local Transportation Agencies Be Authorized to Construct Projects by Design-Build? The new federal act makes virtually any surface transportation project eligible to be built through design-build contracting. As noted earlier, Caltrans is not currently authorized by state law to use design-build, and it does not have experience in using this method to deliver transportation projects. While there are advantages to using design-build, including the potential shortening of project delivery time, there are also potential pitfalls to avoid, including making sure contracts are awarded fairly and competitively such that public accountability is not diminished.

We recognize that there are potential benefits in using design-build to deliver projects. However, because of Caltrans� lack of experience, we recommend that the Legislature provide the department with the authority to use design-build contracting on a pilot basis subject to periodic review and oversight. Accordingly, we recommend that Caltrans be required to report periodically to the CTC and the Legislature on the timeliness of delivery, its process and methodology of contractor selection, and the results of peer review of contracts and projects delivered.

To What Extent Should Caltrans Participate in the NEPA Delegation Pilot? As we noted earlier, allowing Caltrans to assume FHWA�s responsibilities under NEPA could potentially shorten the time required for environmental review. However, this would occur only if Caltrans is equipped with the appropriate level and type of staff to take on the tasks. Furthermore, assuming the federal responsibilities by acting in place of FHWA means that the state could be sued in federal court for its decisions. Prior to determining whether and the extent to which Caltrans should be authorized to participate in the delegation pilot, we recommend that the Legislature direct the department to assess the costs (in terms of staffing and risk of lawsuits) and benefits (in terms of project review timesavings) that could be realized by accepting various levels of delegated responsibilities.

Should CMAQ Funds Be Allocated to Regions That Are Reclassified as Air Quality Compliant? As discussed earlier, a recent federal rule change has resulted in four California counties (Santa Cruz, Monterey, San Benito, and Santa Barbara) being reclassified as air quality attainment areas. As a result, total CMAQ funding to California would be less than otherwise. While the new act allows the state to continue to allocate CMAQ funds to these counties, current state law limits the allocation of these funds only to nonattainment and maintenance regions. Accordingly, we recommend CMAQ funding for these four counties be phased out over a couple of years. This would gradually move CMAQ funds away from attainment areas while refocusing resources on regions with the most serious air quality issues.

How Should the Safe Routes to School Program(s) Be Structured? The new federal SRTS program will provide $68�million to the state through 2009 to fund improvements to nonmotorized transportation facilities in the vicinity of schools. As discussed earlier, this program is similar, but not identical, to an existing state program that is set to continue through 2008.

Currently, the state program is funded at roughly $22�million annually using one-third of the state�s allocation of federal safety grants. We recommend that the Legislature fund the new federal SRTS program at the current state program level. This would free up about $11�million in other federal safety funds in 2006-an amount equivalent to the federal SRTS funding-for other statewide road safety priorities. As the federal SRTS apportionment to California increases each year of SAFETEA-LU, the annual savings would grow to about $22�million by 2009.

In addition to increasing funding for transportation, SAFETEA-LU includes a number of provisions that affect the way that transportation facilities are planned, built, and administered. For California, the new act promises an increase in transportation funding and presents opportunities for financing transportation through nontraditional sources and expediting project delivery. There are, however, a number of issues that the Legislature should consider and areas where further legislative actions are warranted to facilitate implementation of SAFETEA-LU in California.

Caltrans: The California Department of Transportation.

CTC: The California Transportation Commission.

CMAQ: Congestion Mitigation/Air Quality Improvement is a formula program, established under TEA-21, which funds projects and programs offering transportation related emissions reductions.

CBI: Coordinated Border Infrastructure is a new formula program which funds highway mobility improvement projects within 100 miles of an international border.

FHWA: The Federal Highway Administration.

HPP: High Priority Projects is a discretionary program, established before TEA-21, which provides designated funds to specified projects identified by Congress.

HSIP: Highway Safety Improvement Program is a new formula program which provides funding to reduce traffic fatalities and other travel related hazards.

HTF: The Highway Trust Fund is the federal account which collects federal fuel excise taxes and funds most of the highway and safety programs in SAFETEA-LU.

NCIIP: National Corridor Infrastructure Improvement Program is a new discretionary program which provides funding for construction of highway projects in corridors of national significance to promote economic growth and international or interregional trade.

NEPA: The National Environmental Policy Act is a federal environmental review law. It is the federal equivalent of the California Environmental Quality Act.

PAB: Private Activity Bonds are tax-exempt bonds issued by private entities when partnering with a public agency to construct transportation facilities. These bonds encourage private investment in transportation infrastructure by making borrowing less expensive (through paying a lower interest rate).

PNRS: Projects of National and Regional Significance is a new discretionary program which provides funding for high-cost projects of national or regional significance.

SRTS: Safe Routes to School is a new formula program which provides funding for projects that improve nonmotorized transportation facilities used by children traveling to school.

SAFETEA-LU: The Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users, the federal transportation funding program spanning 2004 through 2009.

STIP: State Transportation Improvement Program is California�s primary program for construction of new transportation projects.

STP: Surface Transportation Program is a formula program, established prior to TEA-21, which provides flexible funding that may be used by states on almost any highway, local road, or transit project. TEA-21: The Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century, the federal transportation funding program that spanned 1998 through 2003.

TI: Transportation Improvements is a new discretionary program which provides designated funds to 466 projects identified by Congress.

TIFIA: Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act program provides federal credit assistance to nationally or regionally significant surface transportation projects, including highway, transit, and rail. Both public and private entities are eligible to receive TIFIA funds.

Formula Funds: Funding apportioned to states based on formula.

Discretionary Funds: Grants available on a competitive basis, not apportioned to states by formula.

Earmarked Funds: A subset of discretionary funds which are designated to specific projects.

This report was prepared by

Kendra

Breiland, and reviewed by Dana Curry. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office

which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the

Legislature. To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as an E-mail

subscription service, are available on the LAO's Internet site at

www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000,

Sacramento, CA 95814.

Acknowledgments

LAO Publications

Return to LAO Home Page