Total funding for general government is proposed to decrease in the budget year. The General Fund portion of the budget is proposed to decrease by about $150 million, while the special fund portion is proposed to increase by slightly more than $20 million. The major General Fund changes include the reduction of one-time funding for the Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank ($425 million) and for Year 2000 costs ($48 million) and increases for vehicle license fee-related tax relief ($389 million ) and retirement costs for the State Teachers' and Judges' Retirement Systems ($90 million).

The General Government section of the budget contains a variety of programs and departments with a wide range of responsibilities and functions. These programs and departments provide financial assistance to local governments, protect consumers, promote business development, provide services to state agencies, ensure fair employment practices, and collect revenue to fund state operations. The 2000-01 Governor's Budget proposes $10.5 billion to fund these functions, not including federal funds. The proposed budget-year funding is $129 million less than estimated 1999-00 expenditures.

There are six major program areas within general government:

| Figure 1 |

|||

| General Government Spending |

|||

| By Program Area |

|||

| 1999-00 Through 2000-01 |

|||

| (In Millions) |

|||

| Estimated | Proposed | ||

| Agency/Program | 1999-00 | 2000-01 | Difference |

| Local government subventions | $3,600 | $3,459 | -$141 |

| Tax relief | 1,890 | 2,279 | 389 |

| Regulatory | 1,367 | 1,353 | -14 |

| Tax collection | 590 | 599 | 9 |

| State administration | 1,694 | 1,293 | -401 |

| Retirement | 1,533 | 1,562 | 29 |

| Totals |

$10,674 | $10,545 | -$129 |

The largest general government program is the local government subvention program, proposed to total $3.5 billion in 2000-01 which

(1) distributes state-collected revenue (primarily from vehicle license fees and gas taxes) to local government agencies and (2) provides local governments

additional funding for specified programs.

The Governor's budget proposes to subvene $3.2 billion in shared revenues (virtually all from special funds) and $227 million in other local assistance (all General Fund) to local governments. More than half of this assistance ($121 million) is for the Citizen's Option for Public Safety, a program created in 1996-97 that distributes money to local governments for criminal justice services.

The state provides local tax relief--both as subventions to local governments and as direct payments to eligible taxpayers--through a number of different programs. The Governor's budget proposes nearly $2.3 billion for tax relief expenditures in 2000-01. The two largest are the Vehicle License Fee (VLF) offset and the Homeowners' Property Tax Relief (homeowners' exemption) programs. The Governor's budget proposes an expenditure of $1.7 billion General Fund on the VLF offset in 2000-01, which reflects the continuation of the 35 percent reduction begun on January 1, 2000.

A total of 22 departments are responsible for providing regulatory oversight of various consumer and business issues. Most of these departments are funded from special funds that receive revenue from those subject to regulation. Included in this total are the Departments of Consumer Affairs, Industrial Relations, Food and Agriculture, Financial Institutions, and Corporations, as well as the Public Utilities Commission.

The total proposed expenditures for all regulatory activities in the budget year are $1.4 billion. This includes approximately $1.1 billion from special funds and $286 million from the General Fund. Total expenditures in this category are $14 million, or less than one percent, below estimated current-year expenditures. The four largest agencies in terms of overall proposed expenditures are the Department of Consumer Affairs, $307 million ($1.9 million General Fund); the Department of Industrial Relations, $211 million ($166 million General Fund); the Energy Commission, $210 million (all special funds); and the Department of Food and Agriculture, $208 million ($87 million General Fund).

These regulatory agencies protect the consumer and promote business development while regulating various aspects of licensee, business, and employment practices. The groups regulated range from individual licensees to large corporations.

Expenditures. The Franchise Tax Board and the Board of Equalization are the largest revenue collection agencies in the state. Together, both boards collect the state's personal and business income taxes, sales tax, and special use taxes. The budget proposes $599 million for these tax programs in 2000-01. This is an increase of $9 million, or 1.6 percent, from estimated current-year expenditures.

Revenues. The Governor's budget estimates combined General Fund collections by both boards will be $65.7 billion in 2000-01. More than half of all General Fund revenues ($36.3 billion) come from personal income taxes.

There are more than 30 departments and agencies that provide a wide range of administrative services. These services range from oversight and support of other departments (such as the Department of General Services, the Department of Information Technology, and the Office of Administrative Law), to economic development (such as the Trade and Commerce Agency), to various specialized services provided to individuals and communities (such as the Office of Emergency Services, the Military Department, and the Department of Veterans Affairs).

The budget proposes a total of $1.3 billion to support these functions in 2000-01. This is a decrease of $401 million, or 24 percent, from current-year expenditures. The decrease is primarily a result of the one-time appropriation to the state Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank in the current year.

Retirement-related expenditures account for a significant part of state spending for the budget year. In 2000-01, state expenditures for various costs associated with public employee retirement (excluding University of California costs) will total $2.4 billion, including $2 billion from the General Fund. As summarized in Figure 2, the General Fund provides for employer contributions and/or various other payments to four retirement systems. In addition, the state (1) contributes to the payment of premiums for health and dental benefit plans for retired state employees and (2) makes Social Security and Medicare contributions for most state employees.

Public Employees' Retirement System. The Public Employees' Retirement System (PERS) is the retirement system for most state employees. The budget projects General Fund expenditures of $83 million for PERS in 2000-01. The state's projected General Fund payment to PERS represents a nearly $400 million decline from 1998-99. This is because of changes related to Chapter 555, Statutes of 1999 (SB 400, Ortiz), which enhanced retirement benefits for all state employees effective January 1, 2000. Chapter 555 also required PERS to adopt the following changes to its actuarial valuation methods: (1) modify the June 30, 1998 valuation using 95 percent (rather than 90 percent) of the market value of state employer assets and (2) reduce from 30 years to 20 years the amortization of the June 30, 1998 excess assets beginning July 1, 1999. These changes recognize excess assets more quickly, thereby partially offsetting the state's costs that result from the benefit improvements. The state's costs are anticipated to increase by more than $350 million in 2001-02--the first year that PERS recognizes the increased liability for the benefit improvements in setting the state employer contribution rates.

| Figure 2 | |

| General Fund Costs |

|

| For Retirement Programs a |

|

| 2000-01 |

|

| (In Millions) |

|

| State Retirement Plans | |

| State Teachers' Retirement | $1,007 |

| Judges' Retirement b | 104 |

| Public Employees' Retirement c | 83 |

| Defined Contribution Plan | 35 |

| Legislators' Retirement | -- |

| Subtotal | ($1,229) |

| Other Retirement Benefits | |

| Health and Dental Benefits for Annuitants d | $387 |

| Social Security and Medicare | 346 |

| Subtotal | ($733) |

| Total | $1,962 |

| a Excludes costs for University of California employees. | |

| b Includes 2 percent "pick up" for Bargaining Unit 8 employees' retirement contribution. | |

| c Program for Bargaining Unit 6 employees. | |

| d Legislative Analyst's Office estimate based on 1998-99 costs | . |

State Teachers' Retirement System. The State Teachers' Retirement System (STRS) is the retirement system for teachers in public K-12 schools and community colleges. The STRS receives contributions from teachers and their employers. However, these contributions have historically been insufficient to provide for the cost of basic retirement benefits (which were enhanced by 1998 legislation), the protection of retirees' purchasing power, and past unfunded liabilities (the system no longer has an unfunded liability). These shortfalls have been covered by annual transfers from the General Fund. In the budget year, the transfers are expected to total $1 billion--about $70 million higher than the current year.

Health and Dental Premiums. The budget also includes $387 million from the General Fund to pay the state share of health and dental insurance premiums for retired state employees and their qualifying beneficiaries. This is $39.6 million more than estimated current-year expenditures, reflecting an increase in the number of retirees and a dental insurance premium increase. The PERS is currently negotiating the health premiums rates for the second half of the budget year. These negotiations may result in a change in the estimated General Fund cost for the budget year.

There are approximately 164,000 rank-and-file state employees (not including those in higher education) covered under state collective bargaining law. The pay, benefits, and working conditions for these employees are typically spelled out in memoranda of understanding (MOUs). In September 1999, the Legislature approved MOUs for all of the state's 21 collective bargaining units. These agreements replace the MOUs that expired June 30, 1999 and are effective for a two-year period beginning July 1, 1999. The new MOUs provide a 4 percent salary increase retroactive to July 1, 1999; another 4 percent effective September 1, 2000; and increased retirement benefits (subject to separate legislative action--Chapter 555, Statutes of 1999 [SB 400, Ortiz]).

The Governor's budget includes a total of $60 million ($30 million General Fund, $20 million from special funds, and $10 million from nongovernmental cost

funds) to provide additional employee compensation. According to the Department of Finance, these as yet unspecified adjustments are to address pay issues

(such as recruitment and retention pay differentials) not resolved in the collective bargaining agreements adopted in the fall.

In California, the Department of Insurance (DOI) is responsible for regulating insurance companies, brokers, and agents in order to protect businesses and consumers who purchase insurance. Currently, there are about 1,600 insurers and 300,000 brokers and agents operating in the state.

The budget proposes total expenditures of $157.7 million for DOI in 2000-01. This is $15.7 million, or 11 percent, more than estimated current-year expenditures. The changes proposed for the budget year include:

Fraud Control--A net increase of $8.9 million, mainly due to a proposed increase in state and local activities for auto fraud control that is funded by a recent 50-cent fee increase on auto insurance policies.

Consumer Protection--A net increase of $5.9 million, mainly due to an additional $5.6 million, funded by a recent 30-cent fee increase on auto insurance policies, to eliminate a backlog of enforcement cases and improve consumer protection programs for auto fraud activities. The budget also includes a $3.8 million General Fund loan to continue the Holocaust claims program.

Regulation of Insurance Companies and Insurance Producers--

A $2.2 million increase for regulatory activities.

Earthquake Grants and Loans--A reduction of $1.6 million in local assistance to provide grants and loans to retrofit high-risk residential dwellings owned or occupied by low-or moderate-income households to minimize the risk of future earthquake damage.

We withhold recommendation on the request for a $3.8 million General Fund loan to review, investigate, and resolve insurance claims related to the Holocaust, pending receipt of the forthcoming biannual report on the current status of the program.

The budget includes a $3,778,000 General Fund loan (to be repaid by June 30, 2006) to continue DOI's activities concerning insurance claims related to the Holocaust. Chapter 963, Statutes of 1998 (SB 1530, Hayden) required DOI to implement a program to review, investigate, and resolve unpaid insurance claims for losses resulting from the activities of the Nazi-controlled German government and its allies for insurance policies written before and during World War II by insurers that currently have California affiliates. If an insurer or its affiliate has not paid a valid claim from Holocaust survivors, DOI must suspend the insurer's certificate of authority, which licenses the company to operate in California, until the insurer or the affiliate pays the claim.

Chapter 963 appropriated $4 million to DOI for expenditure during 1998-99 for this program. The legislation stipulates that funding for subsequent years is

subject to appropriations in the annual budget acts. As a result, in the 1999-00 Budget Act, the Legislature approved an additional $4.7 mil-lion General Fund

loan for current-year activities to be repaid by June 30, 2005. The statute also requires DOI to submit to the insurance and budget committees of the Legislature

a biannual report on its

(1) progress implementing the program, (2) results in identifying and resolving insurance claims, and (3) current and anticipated program expenditures.

Biannual Report Forthcoming. According to DOI, there have been no claims settlements or reimbursements yet. In addition, the department has indicated that the required biannual report will be available around the time of budget hearings. Consequently, we withhold recommendation on the request for a $3.8 million General Fund loan for the Holocaust claims program until receipt and review of this report on the current status of the program.

We recommend that the Legislature delete the request for $115,000 to continue the Antirebate Investigation and Enforcement Unit because the department has not demonstrated the effectiveness of this pilot. (Delete $115,000 from Item 0845-001-0217.)

The budget proposes $115,000 for 2000-01 and $230,000 each year thereafter to continue the Antirebate Investigation and Enforcement Unit. Chapter 434, Statutes of 1997 (SB 997, Schiff) established this special unit for a three-year period to enforce state and federal laws prohibiting title companies from paying "kickbacks" or referral fees to real estate agents for directing clients to them to conclude home purchases. Chapter 434 authorized DOI to assess affected companies--title insurers, underwritten title companies, and controlled escrow companies--to pay for the unit's activities, which sunset in September 2000.

The DOI proposes to continue this program without additional authorizing legislation by changing the funding source to license fees currently paid by all insurance companies into the Insurance Fund. The information provided by DOI does not indicate that the department has evaluated the effectiveness of this three-year pilot program. Before this program is made permanent, DOI should provide data that demonstrate its effectiveness. If the program merits continuation, DOI could (1) redirect existing resources to this function on a priority basis or (2) pursue legislation to continue the assessment. In either case, the proposed budget augmentation is not necessary. Thus, given the lack of an evaluation of the pilot, we recommend that the Legislature delete the request.

We withhold recommendation on $16,052,000 of the proposed augmentation of $16,532,000 and 114 positions to implement legislation authorizing an increase in the auto insurance policy fee of up to 80 cents to augment automobile fraud program activities, pending receipt of further information on the proposal. Further, we recommend that the Legislature reduce the request by $480,000 to fund new positions at the first step of the salary range, in accordance with Department of Finance budget instructions and standard budget practice. (Delete $480,000 from Item 0845-001-0217.)

Prior to January 1, 2000, insurers paid $1 for each auto insurance policy written to fund DOI's automobile fraud program to investigate and prosecute fraudulent auto accident claims and car theft. This fee generated approximately $19 million for the program annually, which is allocated to DOI, the California Highway Patrol, and county district attorneys.

Chapter 884, Statutes of 1999 (SB 940, Speier) authorized a 30 cent increase in the $1 auto insurance policy fee to improve DOI's consumer services related to automobile insurance. The legislation specifies that the highest priority for this additional fee is to eliminate the current backlog of consumer complaints regarding auto insurance and illegal conduct by companies selling auto insurance. The department is requesting $5.6 million and 55 positions to implement the provisions of Chapter 884. The DOI proposes to eliminate the backlog by December 31, 2001. In addition, DOI's proposed improvements to consumer service activities include increasing the number of fiduciary examinations, criminal investigations, insurance companies investigated pursuant to consumer complaints, management reviews of companies, companies seized, and staff dedicated to cases leading up to criminal prosecution. The DOI also proposes to reinstate its enforcement of education requirements for licensees and implement a consumer education and outreach program.

Chapter 885, Statutes of 1999 (AB 1050, Wright), authorized an increase in the $1 auto insurance policy fee of up to 50 cent to combat organized crime rings involved in fraudulent auto accident claims. These funds would be distributed among DOI, district attorneys, and CHP, as with existing funds. The funds dedicated to local assistance for county district attorneys are to be used for three to ten grants to combat organized crime rings involved with fraudulent auto claims. The department requests $11 million and 59 positions to implement the provisions of Chapter 885.

Legislature Needs More Information on the Proposed Expenditures.

At the time this analysis was written, we had not received detailed information on the proposed program changes to be funded by the 80-cent fee increase authorized under Chapters 884 and 885. In addition, it is not clear why DOI has chosen to increase the fee dedicated to the organized crime ring component to the full 50 cents allowed by Chapter 885. It is also unclear how DOI will be able to fill all 114 new positions during the budget year. Consequently, except as discussed below, we withhold recommendation on the proposed augmentation.

Funding for Positions Overbudgeted. The proposal includes 46 new fraud investigator positions with sufficient funds to hire the new employees at the top step

of the applicable salary range. Budget instructions from the Department of Finance to all state departments, as well as standard practice, require that new

positions be funded at the first step of the salary range applicable to each position. The requested amount is $480,000 above the first step of the salary range for

the 46 positions. As a result, we recommend deleting $480,000 from the request.

The California State Lottery (lottery) was established by the Lottery Act, an initiative statutory and constitutional amendment approved by the voters in 1984. Revenues from lottery sales are deposited in the State Lottery Fund and are continuously appropriated to the California State Lottery Commission. The commission's budget is displayed in the Governor's budget and is included in the budget bill for informational purposes only.

The Lottery Act provides that sales revenue is to be distributed annually as follows: 50 percent returned to the public in the form of prizes, at least 34 percent for public education, and no more than 16 percent for administrative costs. Figure 1 (see next page) shows the distribution of lottery sales revenue since 1994-95.

We recommend the California State Lottery report to the Legislature on: (1) its authority to allocate more than 50 percent of lottery sales revenues to prizes rather than distribute the excess amount to education as required in the Lottery Act and (2) how the Bridge Project and associated recent changes in administrative expenses and revenue distribution have furthered the purpose of the Lottery Act by providing increased revenue to education.

In 1997, the lottery implemented the Bridge Project, a three-year strategic management plan to streamline lottery operations, decrease administrative expenses and staff, and increase sales. The budget year will be the fourth year of the project. The Bridge Project represents a fairly significant administrative restructuring of the lottery. The project's major initiatives have been to: Hold administrative expenses at no more than 13.5 percent of sales. It is our understanding that the lottery intends administrative expenses to remain at the 13.5 percent level, with further reductions if possible.

Allocate all the difference between the statutory 16 percent maximum for administration and actual costs to prizes.

Reduce staffing levels. The commission cut 219 permanent positions (out of 853) in 1997-98.

| Figure 1 | |||||||

| Distribution of State Lottery Sales Revenue | |||||||

| 1994-95 Through 2000-01

(Dollars in Millions) | |||||||

| 1994-95 | 1995-96 | 1996-97 | 1997-98 | 1998-99 | Estimated | Proposed | |

| 1999-00 | 2000-01 | ||||||

| Annual Sales | $2,166 | $2,292 | $2,063 | $2,294 | $2,498 | $2,550 | $2,550 |

| Distribution | |||||||

| Prizes | $1,075 | $1,128 | $1,031 | $1,182 | $1,307 | $1,339 | $1,339 |

| Educationa | 755 | 798 | 712 | 786 | 850 | 867 | 867 |

| Administration | 336 | 365 | 321 | 327 | 341 | 344 | 344 |

| Percentage | |||||||

| Prizes | 49.6% | 49.2% | 49.9% | 51.5% | 52.3% | 52.5% | 52.5% |

| Educationa | 34.9 | 34.8 | 34.5 | 34.3 | 34.0 | 34.0 | 34.0 |

| Administration | 15.5 | 15.9 | 15.6 | 14.3 | 13.7 | 13.5 | 13.5 |

| Staff levelsb | 880 | 895 | 889 | 853 | 634 | 634 | 634 |

| a This total does not include interest income, unclaimed prizes, or other miscellaneous income distributed to education because these amounts are in addition to the minimum 34 percent allocation mandated by law. | |||||||

| b Authorized permanent positions. | |||||||

The Bridge Project institutes a change in the revenue distribution-- shifting reductions in amounts allocated for administration to prizes rather than education. In the past, and consistent with the Lottery Act, amounts below the maximum 16 percent have been distributed to education at the end of the fiscal year. In 1998-99, however, increasing prize payouts from 50 percent to 52.3 percent resulted in about $58 million of these savings going to prizes, not education. In the budget year the distribution to prizes would be 52.5 percent, resulting in $64 million going to prizes rather than education. While the lottery has the authority to allocate administrative expenses to prizes for promotional purposes, it is not clear if the lottery has the authority to make a permanent change in the revenue distribution. We recommend the lottery report to the Legislature on the lottery's authority to continue allocating over 50 percent of revenues to prizes, rather than distributing the excess amount to education as provided in the Lottery Act.

The lottery believes that offering larger prizes will increase sales and thus result in increased revenue to education. Now that the lottery is in the fourth year of the Bridge Project, it should have sufficient data to present to the Legislature to substantiate this conclusion. Essentially the lottery needs to be able to substantiate that the increase in sales--related to the additional prize payout--is sufficient to offset the amount education otherwise would have received (for example, the $64 million in the budget year).

In the past, when asked to substantiate the proposed positive correlation between prize payout and sales revenue, the lottery has provided data from other state lotteries whose prize payouts exceed California's. The lottery has also indicated that the increasing sales revenue during the years of the Bridge Project "proves" that the positive correlation between prize payout and sales exists.

Other Factors Influencing Lottery Revenues. However, during the four years of the Bridge Project, several other factors have occurred that lead us to question the strength of the relationship between payouts and revenue. First, personal income of Californians has increased significantly over the four years of the Bridge Project and, therefore, individuals have had additional dollars to spend on the lottery. Further, the lottery took other actions during the term of the Bridge Project, each of which, according to the lottery positively affected sales:

At the beginning of the Bridge Project the lottery undertook an aggressive advertising campaign to promote lottery games.

The lottery implemented a retailer cashing bonus to encourage retailers to promote lottery tickets to their customers.

The lottery installed automated lottery ticket dispensers.

Given these factors, the lottery needs to provide more information to substantiate its case that their actions have in fact resulted in increased revenues to education.

We recommend that the Legislature amend the 2000-01 Budget Bill to extend the reporting requirement from the 1999-00 Budget Act and include an additional reporting requirement to be notified of changes in lottery revenue estimates.

The Lottery Act provides the commission certain flexibilities not normally granted to state agencies, such as the continuous appropriation of lottery funds for administrative expenses without external review, and the authority to establish its own procurement policies.

In order to establish a degree of oversight on the state lottery budget, the Legislature added an informational item to the 1999-00 Budget Act identifying planned

budget-year expenditures for administration. Included were several reporting requirements that the lottery provide updated administrative budget estimates to

the Legislature at specific times during the year. These reporting requirements are not included in the budget bill as submitted by the Governor. We believe

continued over-sight and monitoring of the lottery's administrative expenses is important for the Legislature. Thus, we recommend the reporting requirement

from the 1999-00 Budget Act be included in the 2000-01 Budget Bill. Further, in view of the recent differences between projected and realized revenues, we

recommend that the commission also provide updated revenue projections to the Legislature when the administrative expense reports are submitted. If revenues

have been adjusted since the previous report, the commission should include reasons for the adjustments.

The California Gambling Control Commission was established by Chapter 867, Statues of 1997 (SB 8, Lockyer). The five-member commission is to be appointed by the Governor subject to Senate confirmation. The commission (1) is responsible for licensing card rooms, card room owners, and certain card room employees; and (2) assesses fines for violations of the act.

The 2000-01 Governor's Budget proposes $1.2 million from the Gambling Control Fund for support of the commission and its activities, a 2 percent increase from the current-year appropriation. The budget also includes authority for the five commission members and six permanent staff. When this Analysis was written, the Governor had not yet appointed the commission members. As a result, the commission has not incurred any expenditures to date.

Card Room Gambling. Card rooms are one of four types of legal gambling in California. The others are the State Lottery, parimutuel wagering on horse race

results, and charitable gambling. State law prohibits card rooms from offering (1) certain specific games--such as twenty-one,

(2) banked games--games where the house has a stake in the outcome of the game, and (3) percentage games--games where the house collects a given share of

the amount wagered. Typically, card room players pay a fee on a per hand or per hour basis to play the game.

While the basic authority for card rooms is found in state law, local jurisdictions must approve an ordinance authorizing the establishment of a card room. Local governments also establish the operating hours, number of tables, number of players per table, and wagering limits for card rooms in their jurisdiction. Finally, local governments can prohibit the operation of card rooms and can enact more stringent local controls and conditions on gambling.

There are currently 160 card rooms operating in California.

Attorney General Staff Currently Performing Commission Duties.

Pursuant to Chapter 867, the Division of Gambling Control in the Department of Justice investigates applicants for gambling licenses, monitors licensee conduct, and investigates suspected violations of the Gambling Control Act. Essentially, the division provides investigatory services to the commission.

Given that the commission is not operative yet, the division has issued regulations and begun inspections and licensing of card rooms, car room owners, and critical employees. The Gambling Control Act authorizes the division to engage in enforcement and regulatory oversight of the card room industry, regardless of the commission being appointed.

We withhold recommendation on the proposed $1.2 million for support of the California Gambling Control Commission because the commission's workload is yet to be determined.

As noted earlier, the Governor has yet to appoint any commission members. Consequently, there is no experience in the current year as to the level of ongoing workload for the commission. In addition, the commission's workload could be affected by voters' decisions at the March 2000 primary elections (see below).

Commission Has Role in Recently Signed Tribal Gambling Compacts.

The state has recently signed gambling compacts with several Indian tribes to authorize numerous types of previously prohibited gambling on Indian land. These compacts were ratified by the Legislature in Chapter 874, Statutes of 1999 (AB 1385, Battin). The compacts ratified by Chapter 874 will become effective only if Proposition 1A receives voter approval at the March 2000 election and the compacts are approved by the federal Department of the Interior. The compacts, among other provisions, establish two funds that would receive revenue from tribes with gambling activities: one fund for distributing money to various tribes and a second fund, effective in 2002, available to the Legislature for appropriation for various purposes. The compacts also provide for limited state oversight of the gambling activities.

If Proposition 1A receives voter approval, there will presumably be gambling revenue available for distribution to various tribes in the current year as well as in the budget year. The Gambling Control Commission will be the trustee of this fund. In addition, the commission will be the lead state agency for interacting with each tribes's gambling regulatory agency.

Proposition 29 would ratify the tribal-state compacts known as the Pala compacts, signed by the state in 1998. If Proposition 1A fails to receive voter approval and Proposition 29 passes, then the Pala compacts would go into effect. (If both propositions pass, the Pala compact would not go into effect.) These compacts designate the commission as the state agency responsible for establishing state regulation of gambling on Indian lands.

Recommendations. Given these factors, the level of budget-year workload for the commission is unknown at this time. As a result, we withhold

recommendation on the entire budget. The administration will be in a better position in early March to advise the Legislature on the commission's workload.

The Department of Consumer Affairs is responsible for promoting consumer protection while supporting a fair and competitive marketplace. The department includes 26 semiautonomous regulatory boards, commissions, and committees that regulate various professions. These boards are comprised of appointed consumer and industry representatives. In addition, the department has ten bureaus and programs that regulate additional professions which are statutorily under its direct control.

Expenditures for the support of the department and its constituent boards are proposed to total $335 million in 2000-01, a $24 million decrease from the current year. The reduction results primarily from a onetime appropriation in the current year for the California Complete Count Committee. Included in the budget-year total are $2 million in expenditures from the General Fund for support of the Athletic Commission and various public outreach programs.

We recommend deletion of the $1.8 million ($1.2 million General Fund) and eight positions the budget proposes to (1) augment the department's consumer information center ($1 million General Fund) and (2) create eight "consumer ombudsman" positions in various board and program field offices ($766,000 various funds including $185,000 General Fund). (Reduce various items by $1,766,000.)

Call Center Nonjurisdictional Workload. The department operates a toll-free inquiry/complaint (800 number) telephone line to handle telephone inquiries and complaints from consumers and department licensees. The department established the combination automated and live operator call center in 1994 and has since expanded the center to respond to inquiries received via the Internet. It is budgeted at $3.8 million in the current year.

The budget proposes to establish a level of General Fund support for the call center through an augmentation of $1 million. The department believes this augmentation should be provided to offset costs associated with answering calls and inquiries concerning matters not under the department's jurisdiction. These include landlord/tenant issues, vehicle registration and driver's license renewals, and collection agency practices.

We believe the General Fund augmentation is unnecessary and inappropriate. Other state agencies receive nonjurisdictional inquiries--including inquiries intended for the department's boards and bureaus. These calls need to be handled in an effective and efficient manner, but it should not be necessary to determine the correct jurisdiction and then assess that jurisdiction the cost associated with the inquiry.

Furthermore, the department has implemented several methods to efficiently deal with this workload. For example, the department offers recorded information for certain nonjurisdictional programs and its operators have ready access to a list of other government agency call centers so that these calls can be readily forwarded. The department also maintains numerous links on its website to other government agencies. Furthermore, many of the nonjurisdictional calls are clearly not a General Fund responsibility (such as landlord/tenant issues, motor vehicles/ driver's license, and collection agencies).

We recommend the department continue to implement practices that mitigate the impact of nonjurisdictional inquiries. However, we do not believe a General Fund augmentation is appropriate and recommend the Legislature delete the requested $1 million General Fund augmentation.

Consumer Ombudsman Positions. The Governor's budget includes $766,000 ($581,000 from various special funds and $185,000 from the General Fund) to create eight consumer ombudsman positions throughout the state. According to the department, these staff would assist consumers with requests for information or the processing of complaints with the department or any other regulatory agencies. In addition, the staff would be furnished with vehicles so they could ". . . seek out opportunities to ensure all . . . citizens receive complete service . . ."

We believe this augmentation is not warranted for the following reasons:

As mentioned previously, the department currently operates a call center and web site to provide consumer information and respond to consumer inquiries and complaints.

In addition, its constituent boards and programs each have public telephone numbers and several provide information through linked web sites.

Certain boards and programs also operate field offices where consumers can request information.

Other regulatory agencies (such as the Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control) operate field offices as well and, to our knowledge, have not identified a problem which would be addressed by the department's proposed consumer liaison efforts. Further, it is not clear what expertise the proposed new positions would have with regard to regulatory programs outside the department's jurisdiction.

Therefore, we recommend the Legislature delete the requested $766,000 and eight positions.

Background. Chapter 78, Statutes of 1997 (AB 71, Wright) abolished the Council for Private Postsecondary and Vocational Education, established in its place the Bureau for Private Postsecondary and Vocational Education within the department, transferred the council's duties to the bureau, and established some additional regulatory oversight. The bureau is responsible for regulating private postsecondary and vocational schools through a licensing and inspection program and for approving courses and programs.

Chapter 78 also required the bureau to assume responsibility for administering the Student Tuition Recovery Fund, a continuously appropriated fund established for the purpose of relieving or mitigating students' tuition losses suffered when an educational institution closes without fulfilling its instructional obligations. Finally, Chapter 78 gives the bureau authority to establish maximum fees to fund the bureau's operations and specifically directs the bureau to propose legislative modifications to the fee schedule, if warranted.

Budget Proposal. The Governor's budget proposes $7.2 million from various funds and 71 positions to support the bureau in 2000-01, a 26 per-cent decrease from the current year. The reduction is primarily a result of the expiration of a substantial two-year augmentation the bureau had received to process a backlog of work it inherited from the council.

We withhold recommendation on the bureau's budget pending receipt and review of information that explains why the bureau has been unable to eliminate its workload backlog, and what steps will be taken to assure that the bureau fulfils its responsibilities. This information should be submitted to the Legislature prior to budget hearings.

The bureau began operations January 1, 1998. At that time, there was a significant amount of backlogged work. During hearings on the 1998-99 Budget Bill, the bureau requested a two-year staff and budget augmentation to complete the transition from the council and to process the workload backlog. The Legislature approved an augmentation of $1.4 mil-lion in special funds, $1.8 million in reimbursements, and 75 two year limited-term staff--for a total bureau budget of $9.8 million. At that time, the bureau expected to receive the reimbursements from schools to cover the costs of site visits as part of the licensing process.

Subsequently, the bureau determined that it does not have the statutory authority to charge a fee for site visits performed as part of the licensing process. As a result, the bureau did not receive any reimbursements for this work. Furthermore, the bureau also determined that the fee schedule it had adopted in January 1998 for all other work was set too low. A second fee package was developed by the bureau, and during the regulation setting process a public hearing was held in November 1999. Based on review of the public comments, the bureau decided not to proceed with the proposed fee changes. The bureau has not provided any information to substantiate why the bureau made this decision. As a result of this decision, however, the bureau indicates it has not been able to fully address the work backlog, especially the work associated with mandatory site reviews.

It is not clear why this is the case. According to the Governor's budget, the bureau spent over $9.3 million in 1998-99 and expects to spend approximately $9.8 million in the current year. Because of the bureau's inclusion in the department's performance based budgeting efforts, we are unable to determine the number of staff the bureau employed in those years. Nonetheless, the bureau apparently spent the funds the Legislature appropriated to enable the bureau to complete all current workload in a timely manner and to eliminate the backlog it inherited from the council.

Given this situation, the bureau should provide the Legislature, prior to budget hearings, information on: (1) the amount of backlog inherited by category and the current status of the backlog, (2) why it has been unable to completely eliminate the backlog, (3) how the bureau will handle the ongoing workload and eliminate the backlog, and (4) a fee schedule that will provide the bureau with sufficient funds to fulfil its responsibilities in a timely manner and maintain a prudent fund balance. We withhold recommendation on the bureau's budget pending receipt and re-view of this information.

The Legislature should not act on the bureau's budget until the bureau and the Air Resources Board provide the Legislature a report on the status of each aspect of the Smog Check Program and of the February 2000 program evaluation to be submitted to the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

Background. The original framework for a statewide biennial Smog Check program was implemented in 1984 by the Bureau of Automotive Repair. Under this program, both smog (emission) testing and needed vehicle repairs were permitted at any privately owned smog test-andrepair station. The 1990 federal Clean Air Act amendments required a somewhat different smog program in states with the worst air quality, including California. Federal regulations define a region's air quality in one of two ways:

A geographic area that meets or exceeds a national ambient air quality standard is referred to as an attainment area.

An area that does not meet this standard is a nonattainment area.

These nonattainment areas are the focus of the federal Environ-mental Protection Agency (EPA).

Under the 1990 act, the EPA mandated a centralized, state-owned smog check program. Under this scenario virtually all vehicles would have been initially tested at a state-owned, test-only facility. Any vehicle failing the test would go to a second facility to be repaired and then back to the test-only facility to be retested. If the vehicle failed the retest, the process would then begin again with the vehicle owner traveling back and forth between the test and repair facilities.

California negotiated with the federal government to adopt a modified program. This alternative program focuses on the highest polluting vehicles but is intended to be less cumbersome to the customer. The Smog Check program components as agreed to by California and the federal government are laid out in the State Implementation Plan (SIP).

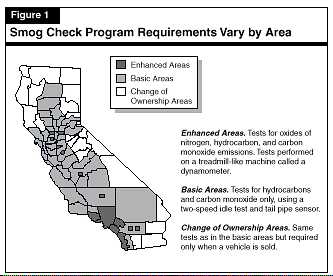

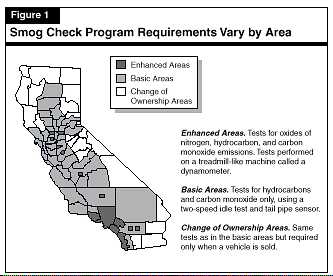

Basics on the SIP. The SIP was adopted by the Legislature in 1994 and approved by the federal EPA in 1996. The SIP divides California into three types of program areas based on air quality--enhanced, basic, and change of ownership. The smog test required varies by area (see Figure 1).

In addition to the requirements in the SIP, the bureau administers several smog-related programs that have been adopted by the Legislature. These other nonmandated programs are the Low-Income Repair Assistance Program and the Voluntary Retirement Program. The state's Smog Check program is funded from two funds--the Vehicle Inspection Repair Fund (VIRF) and the High Polluter Repair and Removal Account (HPRRA). The VIRF funds the SIP-mandated program and the HPRRA funds the other programs.

The SIP-Mandated Components. The SIP-mandated program includes the smog testing and repair stations as well as the bureau's administrative activities (such as enforcement staff, technician licensing, remote sensing, public relations, and general administration). The 2000-01 Governor's Budget proposes $74 million from the VIRF for the bureau's activities related to the SIP.

In addition to the bureau, two other state entities, the Inspection and Maintenance Review Committee and the Air Resources Board (ARB), have responsibilities under the SIP. Both these entities monitor the progress of the bureau in implementing the SIP and the overall effectiveness of the program in bringing California into compliance with federal air standards.

To monitor California's performance, the SIP includes performance standards and deadlines for implementation of key SIP components. Essentially, the SIP calls for the entire state to meet federal air quality standards by 2010.

California agreed to have its complete program in place by December 31, 1997. However, as discussed below, some components of the program have been amended by state statute, others were not implemented by the December deadline, and still others had not been implemented at the time this analysis was written.

Smog Check Stations. The SIP requires California to implement a hybrid testing program that includes test-only stations and the conventional test and repair stations. The California system includes four station designations:

The test-only network of stations was to begin in 1995 and a percent of vehicles in the enhanced areas, as determined by the bureau, were to be sent to test-only stations. The network did not begin until September 1998 but is currently operational.

Remote Sensing. The SIP requires an on-road testing program using remote sensing devices. The program is designed to monitor vehicles as they are driven on the highway. According to the SIP, the sensing units would be set up at various points throughout the enhanced areas. Vehicles shown to be a gross polluting vehicle when driven past a unit would be pulled to the roadside and tested. If the test confirmed that the vehicle was a "gross polluter" the vehicle owner would be required to repair the vehicle and pass a smog test.

In addition, the data compiled from this program was to be incorporated into the high-and low-emitter profiles. The bureau was to use the high-emitter profile to direct vehicles to the test-only stations for the biennial test and use the low-emitter profile to exempt vehicles from the biennial test.

The bureau is using remote sensing to add data to the high-and low-emitter profiles. Vehicles found to be gross polluters by the remote sensing devices are not required to be repaired and pass a smog check simply because of the remote sensing test results.

Oxides of Nitrogen. Under the SIP, the program in the enhanced areas must test for three different pollutants: carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, and oxides of nitrogen (NOx). The NOx is a key component of smog and ozone formation. Therefore, reducing NOx emissions is crucial to meeting the federal air quality requirements.

Testing for NOx was to be implemented by December 31, 1997 but was delayed until September 1998. Also, once NOx testing began, the level at which a vehicle would fail was set very high to avoid failing a large number of vehicles. We understand the bureau is gradually adjusting the failure points toward the level necessary to meet the federal requirements.

Evaluation for Federal EPA. The SIP requires the bureau, in conjunction with the ARB, to submit an evaluation of the Smog Check Program to the federal EPA in February 2000. The evaluation is to address the program's progress in meeting the emission reduction and subsequent air quality improvements as mandated in the SIP. At the time this analysis was prepared, the bureau and the ARB indicated the evaluation report should be ready for public comment in late February and submitted to the federal EPA in March.

In view of the importance of this issue and the Legislature's past concerns with the program, the Legislature should not act on the bureau's budget until the bureau and the ARB provide the Legislature a report on the current status of each aspect of the Smog Check Program and of the program evaluation report.