The primary purpose of California's child support enforcement program is the collection of payments from absent parents for custodial parents and their children. Child support offices in the state's 58 counties provide services such as locating absent parents; establishing paternity; obtaining, enforcing, and modifying child support orders; and collecting and distributing payments. Federal law requires states to provide these services to all custodial parents receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF, which is the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids [CalWORKs] program in California) and, on request, to non-TANF parents. Child support payments collected on behalf of TANF families have historically been used primarily to offset the federal, state, and county costs of TANF grants. Collections made on behalf of non-TANF parents are distributed directly to these parents.

As discussed below, legislation enacted in 1999 transferred state administration of the program from the Department of Social Services (DSS) to the newly created Department of Child Support Services (DCSS). The budget proposes $969�million from all funds ($359�million General Fund) for the DCSS in 2000-01. This includes $874�million ($332�million General Fund) for local assistance for the operation of the local child support offices. The proposal for local assistance represents an increase of $23�million from the General Fund (about 7�percent) over the current year. The budget proses to transfer the state share of child support collections for CalWORKs families--$284�million--into General Fund revenues in 2000-01. Currently, these collections are budgeted as state savings in the form of offsets to CalWORKs grant expenditures.

Prior to the legislative reforms in California, the child support program was administered at the local level by the county district attorneys (DAs), with state oversight by the DSS. In an effort to improve program performance, the Legislature passed a package of bills in 1999, including Chapters 478 (AB 196 Kuehl), 479 (AB 150, Aroner), and 480 (SB 542, Burton and Schiff). Together, these acts made significant changes to the organization, administration, and funding of the program (see Figure�1). Generally, these reforms significantly increased state authority and oversight over the program, and changed state administrative responsibility for developing the statewide child support automation system. Included among the changes are the creation of a new state Department of Child Support Services; the transfer of local administration from the county DAs to separate county child support agencies; and the transfer of responsibility for procurement of the automation system from the state Health and Human Services Agency Data Center to the Franchise Tax Board. (Please refer to our analyses of the "Health and Human Services Agency Data Center" and the "Franchise Tax Board" in the General Government chapter.)

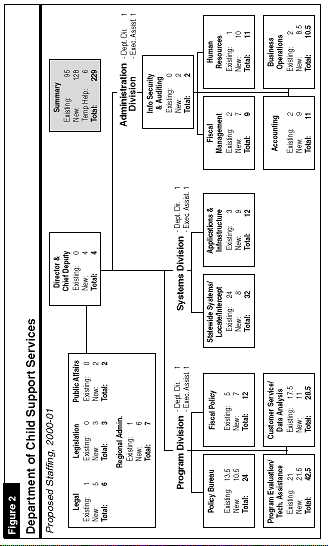

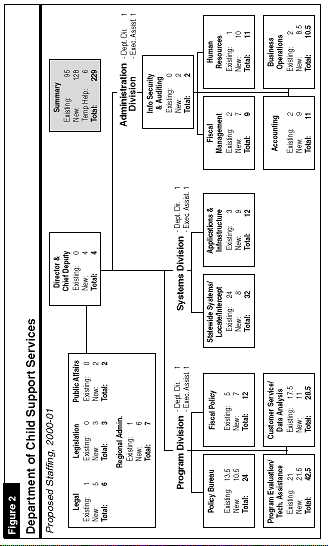

The Governor's budget proposes $95�million from all funds ($26.5�million General Fund) for state operations to support the Department of Child Support Services in 2000-01. The proposal includes a transfer of $79�million ($23�million General Fund) and 95 positions from DSS to the newly created DCSS, and $3.5�million (General Fund) for 128�new positions and additional operating expenses.

We recommend (1)�deletion of five proposed new positions from the Administration Division of the new Department of Child Support Services, (2)�the conversion of five proposed permanent positions in this division to two-year limited term, and (3)�the transfer of four more positions, in addition to the 13.5�transfer positions proposed, from the Department of Social Services to the Department of Child Support Services. This will result in General fund savings of $220,000. (Reduce Item�5175-001-0001 by $125,000 and Item 5180-001-0001 by $95,000.)

The Governor's budget proposed a total of 229�positions for the DCSS (see Figure�2 on page 134). The department is organized into the following units: Executive offices; Program Division; Systems Division; and Administration Division. While the Program Division includes a significant increase in positions (compared to the staffing levels in DSS), we recommend approval of this component because (1)�a significant proportion of the new workload is to carry out new tasks required by the legislative reforms, and (2) we believe there is a need to provide more program support in order to improve the performance of the local child support programs. With respect to the proposed staffing level for the Administrative Division, however, we find that the budget (1)�proposes more positions than are needed and (2)�underestimates the number of positions that should be transferred from DSS.

| Figure 1 |

| Major Provisions of the Child Support Reforms of 1999 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

More Positions Than Comparable Departments. In order to evaluate the Administrative Division, we compared the staffing proposal with the corresponding administrative positions in other departments of similar size (a total of 100 to 300 positions). Our analysis of administrative units focuses on those components that are similar in function to the DCSS administrative functional areas (administrative division management; fiscal and accounting units; human resources; and business operations).

Figure�3 summarizes this comparison. It shows that the budget proposes staffing DCSS with 18�percent of total positions in these administrative units, whereas the comparison departments are staffed at an average of 14�percent for the same units. If held to this administrative average of comparison departments, DCSS should have 32, not the proposed 42, positions in these administrative areas.

While we recognize the need for enhanced staffing to start a new department, we believe that providing DCSS with ten more administrative positions than comparable departments is excessive. Accordingly, we recommend (1) the deletion of five of the proposed new positions from the division and (2) the conversion of five proposed permanent positions to two-year limited term. We believe that this will be sufficient to meet the workload demands of the Administration Division, including tasks associated with starting up a new department. This component of our recommendation would result in General Fund savings of $125,000.

| Figure 3 | |||

| Administrative Division Staffing

Department of Child Support Services and Comparable Departments | |||

| 2000-01 | |||

| Department | Total Positions | Administrative Positionsa | Percent |

| Aging | 142 | 33 | 23% |

| Community Services and Development | 158 | 28 | 18 |

| Real Estate | 303 | 33 | 11 |

| Fair Housing and Employment | 306 | 11 | 4 |

| Average of comparison departments | 227 | 26 | 14% |

| Child Support Services | 229 | 42 | 18% |

| a Excludes positions not comparable to the Department of Child Support Services. | |||

The DSS Should Transfer More Positions. In addition to transferring program staff from DSS, the Governor's budget proposes to transfer 13.5 administrative and support positions from DSS to DCSS. The proposed transfer of 13.5�positions consists of positions from the following units in DSS: Administration; Data Analysis; Legal Services; and Information Systems. In order to calculate the proportionate number of positions to reassign from DSS, the administration used the ratio of DSS's Office of Child Support staffing to total departmental staffing in 1990-91. The rationale for using this baseline year was that, while the staffing of the Office of Child Support grew significantly beginning in 1990-91, DSS grew only minimally in relevant administrative units during the same time period.

We believe the relevant question is whether the DSS has provided adequate administrative support recently, not ten years ago. The administration has not requested additional administrative positions in DSS due to the increase in child support program staff, and has not demonstrated that departmental activities such as accounting and personnel management currently are inadequate. Consequently, we believe it would be more reasonable to apply the department's methodology to current-year staffing levels in DSS, rather than 1990-91. We therefore made the same calculation using the 1999-00 staffing levels and determined that a total of 17.5 administrative and support positions, or four more than proposed in the budget, should be transferred. This is generally consistent, moreover, with the fact that the department claimed federal child support matching funds for 18�administrative positions in 1998-99. Accordingly, we recommend a transfer of four additional positions, and a General Fund reduction of $95,000 in the DSS budget. In total, our recommendations would result in combined General Fund savings of $220,000.

We recommend (1) a $5�million General Fund augmentation for local assistance in 2000-01, to be allocated to local agencies on the basis of county cost-effectiveness (the ratio of historical increases in collections to increases in costs) and (2) enactment of legislation requiring the department to include cost-effectiveness as a criterion in the allocation of all funds to local agencies. We believe that the augmentation will result in a net long-term savings to the state. (Increase Item 5175-101-0001 by $5�million.)

Past Research Suggests Program Underinvestment. In previous analyses, we have shown that the principal goal of the program--the collection of child support--is strongly related to the amount of fiscal resources committed to the program (administrative expenditures). It does not necessarily follow, however, that increasing program spending (and the resulting increase in collections) will be cost-effective to government. This will depend, in large part, on how much it costs to achieve the additional collections. In addressing this question, we found that (1) the counties vary significantly in their levels of cost-effectiveness, as measured by the ratio of collections to costs, and (2) it is likely that an increase in expenditures in many of the counties would yield not only an increase in collections, but net savings to the state due to the welfare grant reductions that result from collections on behalf of these families.

We also found that the funding structure of the prior program--whereby the counties ultimately determined expenditure levels--tended to result in an "underinvestment" of resources in the program. This is primarily because (1) in many cases, counties did not benefit fiscally from the program and therefore had no fiscal incentive to increase spending even when such spending would benefit the state, or (2) in other cases, counties probably would benefit but, without having any assurance of such an outcome, did not want to risk an increase in spending. (For more detail on these findings, please see The 1992-93 Perspectives and Issues and our April 1999 report entitled The Child Support Enforcement Program From a Fiscal Perspective: How Can Performance Be Improved?)

Reforms Create New Opportunity. Under the new reforms, control over spending will shift to the state, creating an opportunity to allocate resources so as to increase both collections and state savings. To achieve this, additional spending should occur in those counties, or local program sites, where there is reason to believe that the resulting increase in collections will be sufficient to yield a net savings to the state. We note that this could be accomplished by a reallocation of existing funding resources among the counties and/or a net augmentation to the program.

Under the new reforms, control over spending will shift to the state, creating an opportunity to allocate resources so as to increase both collections and state savings. To achieve this, additional spending should occur in those counties, or local program sites, where there is reason to believe that the resulting increase in collections will be sufficient to yield a net savings to the state. We note that such an investment could be accomplished by a reallocation of existing funding resources among the counties and/or a net augmentation to the program.

Regardless of the source of funds (reallocation or net augmentation), the state is still faced with the question of how best to allocate program funding among the local jurisdictions. One way to allocate the funds is based on the relative cost-effectiveness of counties as measured by their collections to cost ratios. To illustrate the underlying concept, we note the following two hypothetical examples of counties with different, but generally representative, levels of cost-effectiveness in collecting child support, as indicated by their ratios of marginal collections to marginal costs (that is, the increase in collections that accompany an increase in administrative costs).

In Figure�4, County A is a relatively efficient county which collects an additional $3 in child support for every additional $1 spent in administering the program. County B represents a relatively inefficient county which collects an additional $1 for every $1 expended. The figure shows that after accounting for federal reimbursements, CalWORKs grant savings, and federal incentive payments, a $1 increase in spending in County A would yield a net state savings (12 cents), whereas a $1 increase in spending in County B would result in a net state cost (29 cents).

| Figure 4 | |

| Net State Costs (Savings) From $1 Increase in Spending Under Two Marginal Collections/Costsa Scenarios | |

| Hypothetical County A: Collections/Cost Ratio = $3/$1 | |

| Cost | $1.00 |

| Federal reimbursementb | -.50 |

| Federal incentive payment | -.15 |

| Welfare savings | -.47 |

| Net state costs (savings) | -$.12 |

| Hypothetical County B: Collections/Cost Ratio = $1/$1 | |

| Cost | $1.00 |

| Federal reimbursementb | -.50 |

| Federal incentive payment | -.05 |

| Welfare savings | -.16 |

| Net state costs | $.29 |

| a Ratio of increase in total collections (net of $50 disregard payments) to increase in total administrative costs. | |

| b Assumes reduced federal reimbursement due to automation penalties. | |

Thus, one option would be to reallocate funds from County B to County A. We note, however, that at some point this option could result in significant program disruptions to County B (which, while relatively inefficient, is still providing some programmatic benefits through its efforts), depending on the amount of such reallocations.

A second option would be to augment the program, with the increase limited to those counties that hold the most promise of using the funds cost-effectively (such as County A in our example). In this respect, we note that county cost-effectiveness can be a relatively dynamic phenomenon. In other words, we would expect it to change over time. Furthermore, historical data are only an indication of what might happen in the future, and provide no guarantee.

Analyst Recommendations. After reviewing the historical data on marginal collections and costs among the counties, we believe it would be reasonable to pursue both options. Consequently we recommend (1) a $5�million General Fund augmentation for local assistance in 2000-01, to be allocated to local agencies on the basis of county cost-effectiveness (the ratio of historical increases in collections to increases in costs) and (2)�legislation requiring the department to include marginal cost-effectiveness as a criterion in the allocation of all funds to local agencies. We believe that the augmentation, in particular, will result in a net long-term savings to the state.

If our proposed augmentation is adopted, we recommend adoption of the following budget bill language in Item 5175-101-0001:

Of the amount appropriated in this item, $5�million shall be allocated to the counties solely on the basis of the counties' cost-effectiveness, as measured by the ratio of historical increases in collections to increases in costs.