In response to federal welfare reform legislation, the Legislature created the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program, enacted by Chapter 270, Statutes of 1997 (AB 1542, Ducheny, Ashburn, Thompson, and Maddy). Like its predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), the new program provides cash grants and welfare-to-work services to families whose incomes are not adequate to meet their basic needs. A family is eligible for the one-parent component of the program if it includes a child who is financially needy due to the death, incapacity, or continued absence of one or both parents. A family is eligible for the two-parent component if it includes a child who is financially needy due to the unemployment of one or both parents.

The budget proposes an appropriation of $5.6 billion ($2.1 billion General Fund, $195 million county funds, $30 million from the Employment Training Fund, and $3.3 billion federal funds) to the Department of Social Services for the CalWORKs program. In total funds, this an increase of $186 million, or 3.5 percent. Similarly, General Fund spending is proposed to increase by $78 million (3.8 percent). Although the current-year amounts reflect the grant savings from child support collections, the budget proposes a technical change to treat child support collections as revenues in the budget year. If the budget-year figures for CalWORKs are adjusted, for purposes of comparison, to include the savings from child support collections (net of the costs of child support incentives paid to the counties), then proposed total CalWORKs spending would be $316 million (5.9 percent) less than the current year, and General Fund spending would be $126 million (6.3 percent) below the current year.

Because the Governor's budget proposes to expend all available federal block grant funds and the minimum amount of General Fund monies required by federal law, any net augmentation will result in General Fund costs and any net reductions will result in savings in federal block grant funds (which would be retained by the state).

Maintenance-of-Effort (MOE) Requirement. To receive the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant, states must meet a MOE requirement that state spending on welfare for needy families be at least 75 percent of the federal fiscal year (FFY) 1994 level, which is $2.7 billion for California. (The requirement increases to 80 percent if the state fails to comply with federal work participation requirements.) Although the MOE requirement is primarily met with state and county spending on CalWORKs and other programs administered by the Department of Social Services (DSS), we note that $400 million in state spending in other departments is used to help satisfy the requirement.

Proposed Budget Is At the MOE Floor. For 2000-01, the Governor's budget for CalWORKs is at the MOE floor. We note that the budget also includes, $59 million for the purpose of providing state matching funds for the federal Welfare-to-Work block grant funds. These funds cannot be counted toward the MOE because they are used to match federal funds.

The Governor's budget also proposes to spend all available federal TANF funds in 2000-01, including the projected carry-over of unexpended funds ($459 million) from 1999-00. We note that without these carry-over funds, General Fund spending would be significantly above the MOE floor in 2000-01, under the budget's assumption of fully funding the estimated needs for the program.

We recommend that proposed spending for California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids grants be reduced by $66 million (federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds) in 1999-00 and $35 million in 2000-01 because the caseload is overstated. (Reduce Item 5180-101-0890 by $34,900,000.)

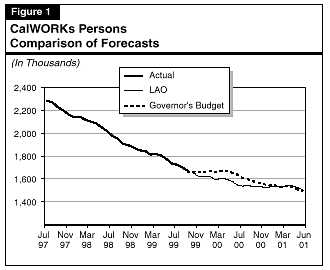

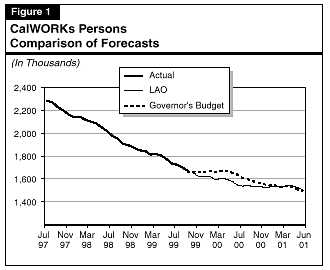

The CalWORKs caseload has been declining rapidly since reaching its peak in 1994-95. During 1998-99, the number of persons in the CalWORKs program decreased by approximately 14 percent. The Governor's budget projects that the average monthly number of persons in CalWORKs will decrease by 10 percent in 1999-00 and 6.8 percent in 2000-01. Thus, on a year-over-year basis the budget assumes a continuing caseload decline. However, the budget's month-by-month estimates show that the caseload is projected to decrease until October 1999, at which point it increases until April 2000. Beginning in May, the budget assumes that the caseload will once again begin to decline, but not as rapidly as in prior years.

Our review of caseload trends does not suggest any reason to project an abrupt end to the caseload decline during the current year. We note that the CalWORKs program was not completely implemented in 1998-99, and that the tendency for recipients to benefit from welfare-to-work services and subsequently leave assistance is likely to be stronger in 1999-00 when the program is fully implemented. Accordingly, we estimate that caseload decline will continue steadily throughout 1999-00. We recognize, however, the possibility that caseloads will level off at some point in the future, once the program is fully implemented. Consequently, in order to be conservative in forecasting budget savings, we project that the caseload will begin to level off in 2000-01.

Figure 1 shows the actual caseload through September 1999 (the last month for which data are available) and then compares the Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) caseload forecast with the Governor's budget forecast. The LAO forecast projects that the caseload will decline by 12 percent in 1999-00 and 5.8 percent in 2000-01. Compared to the Governor's budget, the LAO forecast will result in grant savings of $65.8 million (federal TANF funds) in 1999-00, and $34.9 million in 2000-01. Accordingly, we recommend that the budget be reduced to reflect these savings.

We recommend that proposed spending for California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids grants be reduced by $20 million (federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds) because the statutory cost-of-living adjustment will be lower than estimated in the budget. (Reduce Item 5180-101-0890 by $20,000,000.)

Pursuant to current law, the Governor's budget proposes to provide the statutory cost-of-living adjustment (COLA), effective October 2000, at a General Fund/TANF fund cost of $112 million. The statutory COLA is based on the change in the California Necessities Index (CNI) from December 1998 to December 1999. The Governor's budget, which is prepared prior to the release of the December CNI figures, estimates that the CNI will be 3.61 percent, based on partial-year data. Our review of the actual full-year data, however, indicates that the CNI will be 2.96 percent. Applying the actual CNI of 2.96 percent reduces the cost of providing the COLA to $92 million, a savings of $20 million compared to the Governor's budget. We recommend that the budget be reduced to reflect these savings.The CalWORKs Grant Levels

Figure 2 (see next page) shows the maximum CalWORKs grant and food stamps benefits for a family of three, effective October 2000, as displayed in the Governor's budget assuming a 3.61 percent CNI and as adjusted to reflect the actual CNI of 2.96 percent. As the figure shows, grants for a family of three in high-cost counties will increase by $19 to a total of $645, and grants in low-cost counties will increase by $18 to a total of $614.

As a point of reference, the federal poverty guideline for 1999 (the latest reported figure) for a family of three is $1,157 per month. (We note that the federal poverty guidelines are adjusted annually for inflation.) When the grant is combined with maximum food stamps benefit, total resources in high-cost counties will be $890 per month (77 percent of the poverty guideline). Combined maximum grant and food stamps benefits in low-cost counties will be $873 per month (75 percent of the poverty guideline).

| Figure 2 | |||||

| CalWORKs Maximum Monthly Grant and Food Stamps

Governor's Budget and LAO Projection Family of Three | |||||

| 1999-00 and 2000-01 | |||||

| 2000-01 | LAO Projection Change From 1999-00 | ||||

| 1999-00 | Governor's Budgeta | LAO Projectiona, b | |||

| Amount | Percent | ||||

| Region 1: High-cost counties | |||||

| CalWORKs grant | $626 | $649 | $645 | $19 | 3.0% |

| Food Stampsc | 254 | 243 | 245 | -9 | -3.5 |

| Totals$880$892$890$101.1% | |||||

| Region 2: Low-cost counties | |||||

| CalWORKs grant | $596 | $618 | $614 | $18 | 3.0% |

| Food Stampsc | 267 | 257 | 259 | -8 | -3.0 |

| Totals | $863 | $875 | $873 | $10 | 1.2% |

| a Effective October 2000. | |||||

| b Based on California Necessities Index at 2.96 percent (revised pursuant to final data) rather than Governor's budget estimate of 3.61 percent. | |||||

| c Based on maximum food stamps allotments effective October 1999. Maximum allotments are adjusted annually each October by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. | |||||

We recommend that proposed spending for California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) grants be reduced by $32 million in 1999-00 and $30.1 million in 2000-01 (federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds) because grant savings from the imposition of sanctions on CalWORKs recipients are underestimated. (Reduce Item 5180-101-0890 by $30,095,000.)

The CalWORKs program requires able bodied adults to participate in work or work-related activities for a minimum of 32 hours per week. Failure to comply with this requirement results in a sanction, in the form of a grant reduction. In addition, participants are required to have their children immunized, ensure that their children attend school, and cooperate with child support enforcement. Failure to comply with these requirements results in a penalty (also a grant reduction). Based on data from 1998, the Governor's budget assumes that an average of 4 percent of all CalWORKs cases will have a sanction or penalty imposed upon them during 1999-00 and 2000-01. Consistent with this assumption, the budget estimates savings from penalties and sanctions to be $43.3 million in 1999-00 and $40.7 million in 2000-01.

The most recent data--from July and August of 1999--indicate that the combined sanction and penalty imposition rate was 7 percent, a substantial increase from the 1998 levels used as the basis for the Governor's budget (largely due to increased participation requirements in CalWORKs). Based on the more recent data, we estimate that savings from sanctions and penalties will be $32 million above the budget estimate in 1999-00 and $30.1 million above the budget projection for 2000-01. Accordingly, we recommend that the budget be reduced to reflect these savings.

We recommend that the department count toward the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) maintenance-of-effort requirement $49.9 million in General Fund expenditures for health care for legal immigrants. This action permits the replacement of General Fund expenditures for CalWORKs grants with an identical amount of available federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds, thereby resulting in $49.9 million of General Fund savings. (Reduce Item 5180-101-0001 by $49,900,000 and increase Item 5180-101-0890 by $49,900,000.)

Countable MOE Funds. Pursuant to the federal welfare reform legislation, California may count many types of state spending on families eligible for CalWORKs, even if they are not in the CalWORKs program, for purposes of meeting the MOE requirement. To be countable, such spending must be consistent with the broad purposes of federal welfare reform--providing assistance to families so that they can become self-sufficient. For health expenditures to be countable, they must (1) satisfy a "new spending" test whereby the countable expenditures are limited to the amount by which they have grown since FFY 1995, (2) not be used as matching funds for any federal health program, and (3) not be part of the federally-supported Medicaid program.

State Health Programs for Recent Immigrants. In the budget year, the Medi-Cal program, administered by the California Department of Health Services, will expend approximately $90 million on nonemergency (and primarily preventive) health care for legal immigrants who arrived in the United States after August 1996. This program is not part of the federal Medicaid program, and is therefore supported entirely by the General Fund. In addition, the Managed Risk Medical Insurance Board will expend $4.9 million from the General Fund (also state-only funding) on health care for recently arrived legal immigrant children in the Healthy Families Program.

Providing preventive health services for families with children keeps parents and children healthy and thus assists the parents in keeping regular work hours. Therefore, these health care expenditures are consistent with the purpose of TANF. Because these programs were not created until after 1995 and are paid for with General Fund monies that are not used to match federal funds, they meet the federal requirements for counting health expenditures toward the MOE.

In order to count all of the health care expenditures described above, toward the CalWORKS MOE, the state TANF plan would need an amendment. We note that such an amendment would have no impact on eligibility rules for CalWORKs cash assistance and welfare-to-work services.

Analyst's Recommendation. We recommend that the DSS count the $49.9 million budgeted for these health services toward the MOE and amend the state TANF plan accordingly. This action would result in $49.9 million in General Fund savings. This is accomplished through a fund shift as follows: Counting these health care expenditures raises total state spending to $49.9 million above the MOE floor. Thus, General Fund spending on CalWORKs grants may be reduced by $49.9 million while still maintaining compliance with the MOE. To maintain funding for the grants, $49.9 million in federal TANF funds must be shifted, from available reserves, to support the grants. The TANF reserves will be made available by adoption of all, or part of, our technical recommendations (discussed above) with respect to CalWORKs caseloads and costs.

We recommend a technical adjustment in the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families fund balance (reserves) to reflect the December 1999 award of $45.5 million in federal High Performance Bonus funds.

The federal welfare reform legislation of 1996 authorized the High Performance Bonus award program. From FFY 1999 through FFY 2003, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services will award $200 million annually in High Performance Bonus funds to qualifying states. In 1999, California was one of 27 states that received an award for outstanding performance during FFY 1998. As a result, the state was awarded $45.5 million in federal TANF funds in December 1999. Because part of the formula for future awards is based on improvement in job placement and success in the workforce among CalWORKs recipients, it seems likely that continued implementation of the CalWORKs program should result in additional bonus awards.

Although the Governor's budget summary recognizes the award, the budget's TANF fund balance for 1999-00 does not reflect the receipt of these funds. Consequently, we recommend a technical adjustment in the TANF fund condition statement to account for the receipt of these funds. This adjustment will increase the TANF reserve by $45.5 million.

We note that the Governor's budget summary indicates that a plan for expending the 1999 award funds will be developed in spring 2000. Because these are TANF funds, they must be spent on families eligible for TANF. The funds could be held in reserve, expended within CalWORKs, or expended on new initiatives for the non-CalWORKs working poor. Please see "The TANF Regulations Increase State Flexibility to Serve the Working Poor" at the end of the CalWORKS analysis for a discussion of potential uses for TANF funds.

Finally, we also note that the $45 million in High Performance Bonus funds are distinct from the $20 million received by California for being one of the top five states in reducing the ratio of out-of-wedlock births. The Governor's budget proposes to expend the $20 million awarded for reducing out-of-wedlock births on the Community Challenge Grant Program, which is administered by the Department of Health Services.

Current law requires that a new methodology for budgeting California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) employment services be implemented in 2000-01. Because the new county expenditure plan model for budgeting CalWORKs employment services was not completed in time for inclusion in the Governor's budget, we withhold recommendation on the budget for CalWORKs employment services ($884 million from the General Fund and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds).

Chapter 147, Statutes of 1997 (AB 1111, Aroner) requires that beginning in 2000-01 the budget for CalWORKs employment services be based on "projected county costs" (essentially county CalWORKs services expenditure plans), using a methodology jointly developed by DSS and the County Welfare Directors Association. This new budgeting system was not completed in time for inclusion in the January budget but will be used for the May revision of the Governor's budget. Thus, the January budget for employment services ($884 million General Fund and federal TANF funds) represents a placeholder, pending the completion of the county expenditure plan model. Because the new system may result in substantial changes, we withhold recommendation on the budget for CalWORKs employment services.

The Governor proposes enactment of legislation prohibiting counties from earning new performance incentive payments until the estimated prior obligation owed to the counties (approximately $500 million) has been paid by the state. Once the obligation has been met, the Governor proposes to either repeal or modify the fiscal incentive system. We concur with the Governor's proposal to prohibit new incentives until the past obligation to the counties has been satisfied. We recommend either repealing the county performance incentive provision or replacing it with a new system that would (1) be funded with General Fund monies that the counties could use for any purpose and (2) tie the amount of incentive payments to improvements in program outcomes.

Background. The CalWORKs legislation requires that savings resulting from (1) exits due to employment, (2) increased earnings, and (3) diverting clients from aid with one-time payments, be paid by the state to the counties as performance incentives. Current law also requires that DSS, in consultation with the welfare reform steering committee, determine the method for calculating these savings.

Steering Committee Actions. In 1998, the steering committee determined that savings would be calculated as follows. Savings from exits due to employment would be based on the increase in exits compared the average number of exits in the three years prior to welfare reform. Savings attributable to the earnings of recipients would be paid in their entirety to the counties. Similarly, all savings from diversion were also to be paid to counties.

Growing Obligation to the Counties. By the end of 1998-99 counties had earned approximately $900 million in performance incentives. This amount excludes incentives based on exits due to employment during 1998-99 because the data are not yet available. By the end of 1999-00, we estimate total incentives earned by the counties (including incentives based on exits to employment) will be approximately $1.6 billion. The total of the appropriations (from 1998-99 and 1999-00) for incentive payments is approximately $1.1 billion. Thus, we estimate that the unfunded obligation to the counties will be approximately $500 million by the end of 1999-00. We note that county receipt of fiscal incentives has significantly lagged the appropriation, and that counties have spent very little of their incentive payments. As of September 1999, they had received a total of $685 million but had spent only $5.3 million.

Governor's Proposal. The Governor proposes to prohibit counties from earning additional performance incentives until the unmet obligation to the counties has been satisfied. For 2000-01, the budget proposes an expenditure of $252 million toward this obligation, which, as noted above, is estimated to be $500 million by the end of 1999-00. If $252 million is paid to the counties in 2000-01, a remaining obligation of about the same amount will be carried forward into 2001-02. The department estimates that the counties would earn an additional $500 million in 2000-01, under current law. Thus, the Governor's proposal to prohibit counties from earning additional incentives results in savings of approximately $500 million in 2000-01. The administration also indicates that it will propose legislation to either eliminate or "sharply modify" the performance incentive program.

Department and Steering Committee Could Modify the Methodology. As noted above, the method for calculating the performance incentives is determined by DSS, in consultation with the welfare reform steering committee. The administration has the authority to convene the steering committee at any time, consult with the committee, and then modify the methodology for calculating the incentives.

Legislative Considerations. To assist the Legislature in considering these issues, we begin by examining the rationale for the county performance incentive program. While the Legislature did not specify the purpose of the program, we can identify several possible rationales. Specifically, performance incentives could have been intended as (1) a reward for county performance, (2) an inducement for counties to make an effort to achieve better program outcomes, and/or (3) a funding source for the CalWORKs program. Below we discuss each of these potential rationales for the program.

Reward System. The incentive payments may have been intended simply to be a reward to the counties. If this is the case, however, it is not clear what distinguishes county implementation of CalWORKs from county administration of other state programs in areas such as health, welfare, and criminal justice. Counties administer many programs on behalf of the state. For most of these, counties are provided with operating funds but are not provided with "incentive" bonuses for improved program outcomes. The CalWORKs and child support enforcement programs are the only significant county-administered state programs that offer incentive payments to the counties and under the recent child support reforms, the incentive payments will be largely replaced by a new funding system. There is, however, no analytical basis for determining whether incentive payments should be provided as a reward.

Inducement for Better Program Performance. Another argument for providing incentive payments is that they may act as an incentive for counties to make extra efforts toward improving their programs. As noted above, the counties have spent very little of their incentive payments and are still in the early stages of CalWORKs implementation. Thus, while incentive payments could have some impact in the future, it does not appear that they have had any appreciable effect on county behavior so far.

We also note that, as currently structured, counties can earn substantial incentive payments without demonstrating any program improvement. About $800 million of the performance incentives owed to the counties as of 1998-99 are due to savings attributable to the earnings of recipients. According to DSS, about two-thirds of these savings would have occurred even if CalWORKs had never been implemented (because many recipients were working before CalWORKs started). We believe that for incentives to serve as an inducement, the conditions under which incentives are "earned" must be limited to situations in which program outcomes actually improve.

Finally, we note that given the way fiscal incentives have been budgeted, the counties must spend the incentive payments within the CalWORKs program. Thus, county government programs outside of CalWORKs receive no direct fiscal benefit from the incentive payments.

Program Funding. A third argument for the performance incentives is that they could provide the counties with a source of funding for the CalWORKs program. Under CalWORKs, counties have had two sources of funds for employment services (1) the regular budget allocation to fund estimated program needs and (2) the performance incentives. The regular budget allocation (referred to as the "single allocation") has been based on statewide experience with the Greater Avenues for Independence (GAIN) programCalifornia's previous welfare-to-work program. Under this budgeting system, performance incentives were to be used for county-specific enhancements to the CalWORKs program. We note that this has not been the experience to date. Counties have spent only about 60 percent of their single allocation funds and hardly any of their performance incentives.

Pursuant to Chapter 147, Statutes of 1999 (AB 1111, Aroner) the regular budget allocation for employment services will shift from a system based on the GAIN cost model to one based on county expenditure plans, beginning in 2000-01. The shift to budgeting employment services according to individual county expenditure plans should reduce the need for county performance incentives as a funding source. This is because the county plans, or budgets, can include any funding proposals the counties deem appropriate.

Conclusion. The experience so far with CalWORKs suggests that the county performance incentives have not served as an effective reward, inducement toward better program outcomes, or funding source for program enhancements. While it is possible that, in the future, incentive payments might have some behavioral effect in inducing better performance, we believe that based on experience to date there is little chance of this as the program is currently structured.

Analyst's Recommendation. Based on the amount of prior-year obligations, we concur with the Governor's proposal to prohibit counties from earning new county performance incentives until the outstanding obligation to the counties is satisfied. With respect to whether the program should be eliminated, we have no analytical basis for determining the cost-effectiveness of fiscal incentives. Should the Legislature choose to retain such a system, however, we recommend that it (1) be funded with General Fund monies that can be used by the counties for any purpose and (2) tie the amount of incentive payments to improvement in CalWORKs program outcomes.

We believe that performance incentives would have a better chance of being effective if paid for with General Fund monies that the counties can use for any purpose. This will increase their value to the counties, therefore making it more likely to induce the counties to make an effort to improve the program. Furthermore, it will require the Legislature and the Governor to weigh the potential benefits of the incentives against the costs, because the incentives would compete with other state priorities for funding.

As we have previously recommended, tying performance incentive payments to improvement in outcome measures should increase the chances that these payments will induce counties to make an effort to improve their programs. (For a discussion of this aspect of the issue, please see our analysis of CalWORKs in the Analysis of the 1999-00 Budget Bill.)

Finally, we note that repealing the performance incentive system, or replacing it with a new system supported by the General Fund, will free up a significant amount of federal TANF funds, which have been the principal source of funding for the incentive payments. These TANF funds could be (1) held in a reserve, (2) provided to the counties or other local governments to provide services to TANF-eligible individuals, or (3) used to fund state-level initiatives for the working poor. (Please refer to "TANF Regulations Increase State Flexibility to Serve Working Poor" later in this chapter for a discussion of the possible uses of TANF funds.)

The provision of current law permitting counties to divert grants to employers for the purpose of funding wages for community service participants conflicts with other sections of the Welfare and Institutions Code. Because of these conflicts, counties are effectively precluded from providing wage-based community service. We recommend enactment of legislation to clarify these provisions so that counties will have the option of providing wage-based community service jobs for California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids recipients.

Background. Chapter 270, Statutes of 1997 (AB 1542, Ducheny) created the CalWORKs program. Under CalWORKs, able-bodied adult recipients (1) must meet participation mandates, (2) are limited to five years of cash assistance, and (3) must begin community service employment after no more than 24 months on aid, unless they have obtained nonsubsidized employment. With respect to "grant diversion," Chapter 270 authorizes counties to divert all or part of a recipient's cash grant to an employer to fund a recipient's wages. The statute specifically states that such grant diversion can be used to fund wages for community service participants. (We believe that wage-based community service is a good option for CalWORKs recipients, as explained in our February 1999 report, CalWORKs Community Service: What Does It Mean for California?)

Earned Income Disregard. Under CalWORKs, recipients who obtain nonsubsidized employment are entitled to a specific "earned income disregard." Under this system, the first $225 of earnings, plus 50 percent of each additional dollar of earnings, are disregarded (not counted as income) in determining a family's grant. This structure is designed to encourage recipients to obtain nonsubsidized employment.

Based on our understanding of current law, a CalWORKs community service participant who is receiving wages that are funded through grant diversion would be entitled to the same $225 and 50 percent earned income disregard that is available to a recipient in a nonsubsidized job. We believe that application of the disregard substantially reduces the incentive to find nonsubsidized employment. Accordingly, we previously recommended (in our February 1999 report) that the Legislature eliminate or reduce the earned income disregard for community service participants whose grants are diverted and paid to them in the form of wages.

Maximum Aid Payment Statute Effectively Precludes Grant Diversion. The DSS concurs that a recipient of a diverted grant is entitled to the earned income disregard. The department also believes that, under current law, total grant payments cannot exceed the maximum aid payments prescribed in Section 11450 of the Welfare and Institutions Code. Therefore, the department concludes that current law has the effect of precluding counties from diverting most or all of a recipients grant to an employer because such a grant diversion, when combined with the application of the earned income disregard, would ultimately result in a total grant ($1,052 for a family of three) that would exceed the maximum aid payment ($626). In other words, DSS believes that the statute governing maximum aid payments overrides the provision that applies the disregard to wages funded with grant diversion (which is the statutory basis for a wage-based community service program).

In summary, current law includes two technical obstacles to wage-based community service. First of all, it severely restricts counties' ability to use grant diversion to fund wage-based community service positions because of the interaction between the code sections pertaining to grant diversion, the earned income disregard, and the maximum aid payments. Secondly, by applying the earned income disregard to community service participants, it makes no distinction between subsidized and nonsubsidized employment, thereby reducing the incentive for participants to obtain nonsubsidized employment, and increasing the costs of the program.

Analyst's Recommendation. We believe that applying the disregard to subsidized employment results in an unintended consequence of Chapter 270. In order for wage-based community service to be a viable option for counties, we recommend enactment of legislation to clarify that the earned income disregard does not apply to "diverted grants" that are used to fund community service wages. As an alternative to eliminating the disregard, the Legislature could also provide a work expense supplement in the amount of $50 in lieu of the current $225 and 50 percent disregard, on the basis that recipients participating in wage-based community service must pay employee Federal Insurance Contributions Act taxes (about $50 per month).

These clarifications to current law would allow counties to provide wage-based community service positions, while maintaining the incentive for recipients to obtain nonsubsidized jobs.

The Governor's budget fully funds the estimated need for California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) child care, plus a reserve of $81 million. The budget proposal includes an increase of $85 million for the Stage 3 "set-aside" designed to provide former CalWORKs families with child care beyond the two-year time limit for such services. We summarize the CalWORKs child care program.

Background. The CalWORKs child care program is delivered in three stages. Stage 1 is administered by county welfare departments (CWDs) and begins when a participant enters the CalWORKs program. In Stage 1, CWDs refer families to resource and referral agencies to assist them with finding child care providers. The welfare department then pays providers directly for the child care services.

Families transfer to Stage 2 when the county determines that the families' situations become "stable"that is, they develop a welfare-to-work plan and find a child care arrangement that allows them to fulfill the obligations of that plan. Stage 2 is administered by the State Department of Education (SDE) through its voucher-based Alternative Payment (AP) programs. Participants can stay in Stage 2 while they are on CalWORKs and for up to two years after the family stops receiving a CalWORKs grant. Because it is up to the CWD to determine when a recipient is stable, the time at which families are transferred from Stage 1 to Stage 2 varies significantly among counties. Some counties make the transfer to Stage 2 as soon as possible, while others wait until the family has left CalWORKs. The variance in county practice contributes to the uncertainty in budgeting child care funds for each stage.

Although Stages 1 and 2 are administered by different agencies, families do not need to switch child care providers upon moving to Stage 2. The real difference in the stages is in who pays the providers--in Stage 2, AP programs, operating under contracts with SDE, do this instead of CWDs.

Stage 3 refers to the broader subsidized child care system administered by SDE that is open to both former CalWORKs families and working poor families who have never been on CalWORKs. Once CalWORKs recipients leave aid, they have two years of eligibility in Stage 2. During this time, they are expected to apply for "regular" Stage 3 child care (in contrast to the Stage 3 set-aside child care discussed below). We note, however, that typically there are waiting lists for such child care because there are significantly more eligible families than the available child care slots. (Families with incomes up to 75 percent of the state median are eligible for regular SDE child care, but priority is given to families with the lowest income. Most of the available slots go to families with incomes below 50 percent of the state median).

In order to provide continuing child care for former CalWORKs recipients who reach the end of their two-year Stage 2 time limit, the Legislature created the Stage 3 set-aside in 1997. Recipients timing out of Stage 2 are eligible for the Stage 3 set-aside if they have been unable to find regular Stage 3 child care. Assuming funding is available (and legislative and administrative practice to date has been to fully fund the estimated need), former CalWORKs recipients may receive Stage 3 set-aside child care as long as their income remains below 75 percent of the state median and their children are below age 14.

Current-Year Spending. For 1999-00, the total appropriation for CalWORKs child care was $1.2 billion, including a reserve of $270.7 million that can be allocated to Stage 1 or Stage 2 depending on a subsequent determination of actual need. As of January 2000, $128 million of the reserve had been allocated to Stages 1 and 2. The budget estimates that an additional $98 million will be transferred from the reserve to either Stage 1 or State 2 before the end of 1999-00. Although total spending for 1999-00 is estimated to be about $45 million below the appropriation, spending for the Stage 3 set-aside is approximately $10 million greater than estimated. The administration has proposed to fund this anticipated $10 million shortfall mostly with savings from 1998-99.

Proposed Budget. For 2000-01, the Governor's budget proposes $1.3 billion for CalWORKs child care. This is an increase of $117 million (9.8 percent) over the current-year appropriation. Figure 3 summarizes the proposed spending plan. As discussed below, most of the increase is due to higher costs in Stage 3. The budget proposal includes a reserve of $150.4 million. Of this total, $69.4 million is "held back" from the estimated need for Stage 2 child care. The remaining $81 million is above the estimated need and represents a "true" reserve for Stages 1 and 2. This includes $45.4 million that is anticipated to go unspent from the current-year reserve and is proposed to be transferred to the budget-year reserve.

| Figure 3 | |||||

| CalWORKs Child Care

Estimated Children Served and Proposed Budget | |||||

| 2000-01

(Dollars in Millions) | |||||

| Estimated Number of Children | Funding | ||||

| Total | TANFa | CCDFb | General Fund | ||

| Stage 1 | 83,000 | $424.2 | $389.7 |

-- |

$34.5c |

| Stage 2 | 117,000 | 624.5 | 442.8 | $43.0 | 138.7d |

| Child care reservee | 29,000 | 150.4 | 150.4 |

-- |

-- |

| Stage 3 set aside | 21,000 | 115.7 |

-- |

63.4 | 52.3f |

| Totals | 250,000 | $1,314.8 | $982.9 | 106.4 | $225.5 |

| a Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. | |||||

| b Child Care Development Fund. | |||||

| c General Fund used toward CalWORKs maintenance-of-effort requirement. | |||||

| d Proposition 98 funds, including $15 million in the California Community Colleges. | |||||

| e Proposition 98 funds. | |||||

| f The reserve will be allocated to Stage 1 or Stage 2 depending on actual need. | |||||

Stage 3 Set-Aside Costs Are Growing Rapidly. As shown in Figure 3, the estimated cost for the Stage 3 set-aside is $116 million, an increase of almost $90 million compared to the current-year estimate. This increase is because a growing number of former CalWORKs recipients are expected to reach their two-year Stage 2 post-assistance time limit. Preliminary estimates from the Department of Social Services indicate the cost for the Stage 3 set-aside will increase to about $200 million in 2001-02 and about $265 million in 2002-03.

For a discussion of the how child care for CalWORKs families differs from child care for the non-CalWORKs working poor families, please see "Child Care for CalWORKs Families and the Working Poor" in the Crosscutting Issues section of this chapter.

We recommend the adoption of budget bill language requiring county probation offices to report data on all juvenile probation referrals, court actions, and final dispositions to the Department of Justice, in order to receive full-funding allocations for county probation facilities.

Background. County probation departments receive about $200 million annually from the state for support of probation camps and ranches that house juvenile offenders and for a wide range of juvenile justice system services, from basic prevention to various kinds of residential placements for juvenile offenders. These services are funded with federal TANF monies.

Information on these children and other juveniles involved with the probation system is collected by the Department of Justice (DOJ) and stored in the Juvenile Court and Probation Statistical System (JCPSS). This is a statewide database that collects information from county probation departments on all juvenile probation referrals, court actions, and final dispositions. The database was active through the 1980s, using information voluntarily provided by all 58 counties, but was eliminated in 1989 due to budget reductions at DOJ.

The purpose of the JCPSS is to provide a statewide database of information about juveniles in the criminal justice system. The database is used for many purposes, including assessing potential impacts of recent and proposed changes in law.

Many Counties Not Reporting Data. Chapter 803, Statutes of 1995 (AB 488, Baca) directed DOJ to reestablish a juvenile justice data collection system, and the Department of Information Technology approved a new database design in August 1996. Since that time, DOJ has attempted to collect information from all of the counties. Currently, 15 counties are submitting data and 15 counties are testing to determine whether their reprogrammed databases are effective. Of the remaining counties, 10 intend to begin testing software within the next few months, and 18 have taken no action to submit data to DOJ.

Statewide Database Participation Is Necessary. In our view, it is important for the state to have complete and accurate data as to how juveniles are treated in the criminal justice system in order to assist policymakers in analyzing the state of the juvenile justice system and in making decisions about proposed legislation. The information is valuable to the counties as well as the state in assessing trends among counties and impacts of county-based programs. For this reason, we believe that it is vital that all counties submit data to DOJ, in order to ensure that information from the JCPSS reflects the statewide juvenile justice situation.

These concerns about the need for better county reporting were raised during 1999-00 budget hearings last spring and the county probation officers committed to begin submitting data to the JCPSS. To date however, only a handful of counties are submitting data.

Analyst's Recommendation. In order to ensure that the state has complete data in JCPSS, we recommend that the Legislature adopt budget bill language that would require counties to forfeit a portion of the TANF monies provided to probation if they do not submit data to DOJ by March 2001. We believe that this will give all counties adequate time to develop their reporting mechanisms. We do not believe that this will create a hardship on counties since they already collect the requested data for their own use. Based on our discussions with DOJ and counties, the costs to counties to report the data to DOJ should be minimal. The TANF dollars provided to probation departments could cover these minimal costs.

Specifically, we recommend the following budget bill language be adopted in Item 5180-101-0001:

A county shall receive no more than 50 percent of its respective allocation of funds appropriated under Schedule (a)(5) 16.30.050County Probation Facilities until the Department of Justice (DOJ) has certified to the Department of Social Services that the county is participating in the Juvenile Court and Probation Statistical System. Counties that fail to receive certification by March 31, 2001 shall forfeit the balance of their allocation. Any funds forfeited pursuant to this provision shall be reallocated to counties that have received DOJ certification. The distribution shall be proportionally based on such counties' original allocations.

The final federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) regulations increase state flexibility to serve working poor families that are not eligible for the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids program. We summarize the TANF regulations and present some options for program changes permitted by the regulations.

Background: Federal Welfare Reform. The federal welfare reform legislation of 1996 replaced the AFDC program with the TANF program. The federal law made numerous changes in the nation's welfare system, including the following: the individual entitlement to a grant is eliminated; federal funding for the program is provided as a block grant; recipients are subject to a five-year time limit for receipt of federal funds; and states are subject to various penalties for failing to meet specified objectives, including work participation rates.

In order to receive the federal block grant, states must meet a MOE requirement that state spending on welfare for needy families be at least 75 percent of FFY 1994 level, which is $2.7 billion for California (the requirement increases to 80 percent if the state fails to comply with federal work participation requirements). State MOE funds can be spent in conjunction with TANF funds or may be expended on separate state-only programs for needy families.

Previous Federal Guidance Limited State Flexibility. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) issued its first written guidance for the TANF program in January 1997 and later issued proposed regulations in December 1997. Both of these documents had the effect of limiting state flexibility in implementing the TANF program. State flexibility was limited by (1) the way in which DHSS defined the term "assistance," and (2) cautions against the creation of state-only programs. These limitations are explained below.

Definition of Assistance. The definition of assistance is important because a recipient of TANF assistance is subject to all TANF program requirements, including time limits, work participation requirements, and certain child support rules. In both the initial federal guidance and the proposed regulations, the DHHS defined almost all benefits or services funded with TANF funds as assistance. This broad definition meant that almost any recipient of a benefit funded with TANF funds would be subject to TANF rules, including the federal time limits. Thus, under this regulatory approach receipt of services such as child care, or counseling for victims of domestic violence, would require recipients to meet time limits and other TANF requirements.

Limits on State-Only Programs. State TANF programs, such as the CalWORKs program in California, are funded with a combination of TANF federal block grant funds and state MOE funds. (In California, most of the MOE funds are state funds appropriated for the CalWORKs program, but some state funds supporting TANF-eligible families in other programs also qualify.) The federal legislation indicated that if states create separate state-only programs for needy families (funded only with state MOE funds), TANF requirements such as time limits and work participation would not apply to such programs. The DHHS guidance and proposed regulations, however, threw this provision into question by cautioning that states creating separate state-only programs may not be eligible for federal TANF penalty relief. (We note that the dollars at stake were not insiginificant. For example, in FFY 1997, the DHHS used its authority to reduce California's penalty for noncompliance with federal work participation rates by about $32 million.)

Final Regulations Increase Flexibility. In April 1999, the DHHS released its final TANF regulations. These regulations became effective on October 1, 1999. In comparison to the proposed rules, the final regulations increased state flexibility in several ways as follows.

Narrowing the Definition of Assistance. The term assistance is now defined narrowly. Under the final rules, assistance is generally limited to payments directed at providing for a family's ongoing basic needs. The definition of assistance specifically excludes (1) nonrecurring short-term benefits designed to respond to crisis situations lasting less than four months, (2) child care, (3) transportation benefits, (4) work subsidies paid to employers, (5) refundable earned income tax credits, and (6) services such as education and training. Thus, a state can provide such "nonassistance" benefits with TANF or state MOE funds without triggering TANF requirements for the recipients of such benefits.

State-Only Programs Permitted. Prior warnings that the creation of state-only programs might result in a state being ineligible for penalty relief have been dropped. The regulations simply require that states report program information on state-only programs to DHHS.

State Authority to Define Needy. The final regulations affirmed and strengthened state flexibility to define the term "needy." Because most TANF spending is limited to needy families or parents, the definition of needy is important. Under the final regulations, states may set multiple definitions of needy and tailor benefits to the populations falling within each respective definition. For example, the state could set one definition of needy for cash assistance and a "higher" definition of needy to allow for the provision of services, without cash assistance, to working poor families. The final regulations do not establish any income limit on the definition of needy.

Options for Using New Flexibility. Below we identify two types of changes that are permitted by the final regulations. The first category consists of program expansions. These options would require additional resources or redirection of resources within the TANF program. Second, we present certain program changes that do not require substantial additional resources.

Generally, the significance of this added flexibility is that it gives the state new options for using federal TANF funds to serve the working poor. Specifically, these funds are now available to support new activities or to replace CalWORKs General Fund support within the Department of Social Services (provided this meets the MOE requirement).

Potential Program Expansions. The expansions discussed below would result in program costs. Although counties were unable to expend all of the TANF funds provided for the CalWORKs program in 1998-99, the Governor's budget projects that these carryover balances will be exhausted by the end of 2000-01. Thus, if the Legislature were to use TANF funds for any of the options presented below, new funding eventually would have to be identified either from redirection within the CalWORKs program or from the General Fund in order to continue the expansions.

Potential Program Modifications. In contrast to the program expansions discussed above, the program changes presented below do not result in significant costs.

Conclusion. The final TANF regulations provide the Legislature with significant new flexibility to modify the CalWORKs program. In summary, the state can now use TANF and state MOE funds to provide services to working poor families that are not eligible for CalWORKs cash assistance without triggering TANF requirements such as the federal time limit, work participation requirements, and certain child support rules.