Analysis of the 2001-02 Budget BillLegislative Analyst's Office

|

In this section, we discuss several of the most significant spending proposals in the budget. For more information on these spending proposals and our findings and recommendations concerning them, please see our analysis of the appropriate department or program in the Analysis of the 2001-02 Budget Bill.

Education programs account for 52 percent of General Fund spending in the 2001-02 Governor's Budget. Below we provide an overview of the budget for K-12 and higher education, beginning with a focus on Proposition 98.

Background. Proposition 98 establishes a minimum funding level that the state must provide for public schools and community colleges each year. K-12 education receives about 90 percent of total Proposition 98 funds.

Governor's Budget-Year Plan. The budget proposes $41.3 billion in total K-12 Proposition 98 funding in 2001-02 (consisting of state General Fund and local property tax allocations). This is an increase of almost $3.2 billion, or 8.3 percent, compared to the 2000-01 revised amount. Pupil attendance is projected to increase by 1.08 percent, resulting in funding of $7,174 per pupil, an increase of $479 (7.1 percent) from the revised 2000-01 amount.

The major 2001-02 budget proposals include:

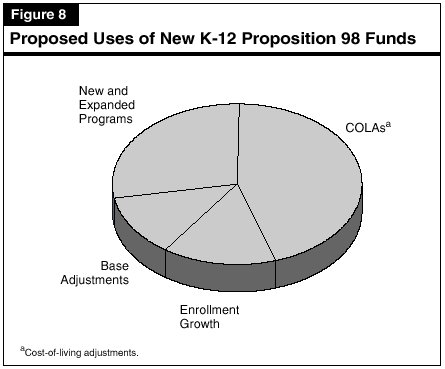

Figure 8 illustrates how the budget would allocate projected growth in K-12 Proposition 98 funds in 2001-02.

Budget "Overappropriates" Proposition 98 Minimum Requirement. The Governor's proposed spending level for Proposition 98 (including the community colleges) exceeds his estimate of the constitutionally required minimum amount for 2001-02 by $1.9 billion. Under the terms of Proposition 98, the state could set its K-14 education spending level at the required minimum amount determined for 2001-02 by the proposition's "test 3" calculation. However, this would cause the state to fall far short of the amount required to meet COLAs, enrollment growth, and adjustments needed to annualize spending for new programs and program expansions authorized in the 2000-01 Budget Act. The Governor set his proposed appropriation total at Proposition 98's "test 2" amount, which not only meets COLAs, enrollment growth, and annualization needs, but provides resources for further K-14 initiatives. This test 2 spending amount—a combined total of $46.4 billion from the General Fund and local property tax allocations to school and community college districts—also is consistent with the minimum level of annual appropriations that will be required in future years under the terms of Proposition 98. (For all practical purposes, the test 2 calculation determines this long-run appropriations requirement.)

The University of California (UC) and the California State University (CSU). The budget proposes General Fund support for UC and CSU of $6.1 billion in 2001-02, an increase of $418 million, or 7.4 percent, compared with estimated current-year budgets. Budgeted enrollment levels at UC and CSU would increase by 5,700 full-time equivalent (FTE) students at UC and 8,760 FTE students at CSU. The budget proposes a 5 percent baseline funding increase totaling $267 million in General Fund appropriations for the two segments. The proposed budget also includes a total General Fund increase of $38 million in lieu of student fee increases.

Community Colleges. The budget proposes $3 billion in General Fund support for the community colleges in 2001-02. All but $83 million of this amount counts as Proposition 98 spending. The 2001-02 General Fund request represents an increase of $225 million, or 8.2 percent, from the current year. The combined increase proposed from all funding sources, including student fee revenues is $444 million, which represents a 7.8 percent increase in combined funding.

In 2001-02, the budget provides $154 million for a 3.91 percent COLA for general-purpose spending, $114 million for enrollment growth of 3 percent, and $62 million to increase part-time faculty salaries.

Student Aid Commission. The budget proposes a General Fund increase of $138 million, or 26 percent, for the Student Aid Commission in 2001-02. The majority of this increase, $128 million, pays for the added costs associated with additional Cal Grant awards authorized by Chapter 403, Statutes of 2000 (SB 1644, Ortiz).

Need for Greater Local Flexibility—K-12 Education. We take broad issue with the priorities and approach to K-12 education taken by the budget. One of the salient aspects of the 2001-02 Governor's Budget is the relative lack of discretion given to local school districts. The budget adds to the major area of general purpose funds for K-12—"revenue limits"—only what existing law requires to cover COLAs and enrollment growth. The budget proposes spending the remainder of new funds for K-12 education on a long list of new and expanded categorical programs. As well-intentioned as these programs are, we believe most will be diminished in effectiveness because of constraints on local discretion. A notable exception is the Governor's proposal to expand standards-based training to K-12 teachers over three years, where a significant element of local discretion has been introduced.

To maximize the chances for improving educational results, the state must give local school districts and school sites more flexibility to fit budgetary resources to local circumstances and needs. The approach we take to the state's K-12 education budget in the 2001-02 Analysis of the Budget Bill builds on this foundation.

Disadvantaged Schools Block Grant. We recommend various changes in Proposition 98 appropriations for the budget year, involving the redirection of almost $800 million of proposed spending. The largest of these changes is a recommendation to establish a $500 million disadvantaged schools block grant focused on middle schools and high schools that are very low-performing and/or have high concentrations of students in poverty. We make this recommendation, in part, as an alternative to the Governor's proposal to extend the length of the school year for middle school grades. Although this proposal by the Governor requires $100 million in 2001-02, it could require annual spending of $1 billion or more by the 2003-04 fiscal year. As we discuss in detail in the 2001-02 Analysis, the Governor's proposal attempts to address student achievement problems, as measured by standardized test scores, that manifest around grade nine. As we also discuss, however, the proposal's approach is flawed in many respects, including:

We believe our recommended disadvantaged schools block grant better addresses the above problems. The essence of our block grant is twofold (1) targeting resources to schools and students most in need of additional state help and (2) local discretion to draw from a broad "menu" of specific educational interventions. These interventions could include lengthening the school year at disadvantaged schools—if school officials determine this best meets local needs—but also could include a "mix" of such measures as selective reductions of class size, focused tutoring, improved after school programs, improved quality of curriculum, enriched (or restored) music and arts education, and more and better counseling.

Other Recommendations Provide Expanded Local Flexibility. We make various other recommendations that would give school districts and community colleges more control over their resources. For example, we recommend allocating an additional $175 million to K-12 revenue limits, which districts could use for any purpose. With regard to community colleges, we recommend that $81 million in the budget targeted for various part-time faculty issues and financial aid administration be redirected to Partnership for Excellence. This program gives districts flexibility to direct funding to local priorities in order to meet their education goals.

Make Better Use of Existing Teacher Training Resources. As mentioned above, the Governor proposes a greatly expanded effort over the next three years to train nearly all the state's teachers in providing instruction based on the state's academic content standards. The Governor proposes spending $830 million over the three years, including a $335 million augmentation for 2001-02. We recommend an approach that better accounts for existing programs and provides a more realistic implementation time frame. Our approach provides the same number of teacher training opportunities over the three years, at a General Fund savings of $235 million in 2001-02 and $500 million over the three years.

Better Preparing Students for College. In the Analysis, we recommend that the Legislature adopt a multifaceted strategy to improve students' academic preparation for higher education and increase the segments' accountability for appropriately serving unprepared students. Specifically, we recommend the segments assess students' college readiness earlier, report on the preparedness of all entering students, and study the effectiveness of their precollegiate courses across the three segments in a more equitable manner.

The Governor's budget proposes a number of augmentations totaling $1.2 billion ($1.1 billion General Fund) related to the state's energy crisis (see Figure 9). These proposals would add nearly 100 positions across six departments. The largest share of proposed expenditures is for a $1 billion General Fund set-aside for energy initiatives to address the energy crisis. Proposed budget bill language specifies that (1) the funds are for "projects awarded by the Governor's Clean Energy Green Team" and (2) allocation of the amount appropriated will be subject to legislation. No further information is available on this set-aside at this time.

| Figure 9 | |||

| Energy-Related Budget Proposals 2001-02 Governor's Budget | |||

| (Dollars in Thousands) | |||

| Amount | |||

| Proposal | General Fund | Special Funds | Positions |

| Energy Initiatives (Item 3365) | |||

| Set-aside for energy projects |

$1,000,000 |

— | — |

| Air Resources Board (Item 3900) | |||

| Diesel engine grant program to offset new power plant emissions |

100,000 |

— | 4 |

| Utilities Costs (Item 9911) | |||

| For increased state department costs for natural gas and electricity |

25,000 |

$25,000 | — |

| Department of Transportation (Item 2660) | |||

| Diesel retrofit and green fleet program to offset emissions from new power plants |

— |

20,332 | — |

| Energy Commission (Item 3360) | |||

| Long-Term Energy Baseload Reduction Initia- tive: electricity market analysis, Renewable Energy Program administration, and energy efficiency standards update |

3,230 |

2,626 | 8 |

| Power plant siting program |

3,129 |

— | 19 |

| Alternative energy grant programs |

— |

1,000 | — |

| Subtotals (Item 3360) |

($6,359) |

($3,626) | (27) |

| Department of Justice (Item 0820) | |||

| Investigate electricity generators and natural gas suppliers |

$3,975 |

— | 15.5 |

| Public Utilities Commission (Item 8660) | |||

| Green Team activities |

2,738 |

— | 34 |

| Track San Diego Gas and Electric costs to purchase electricity |

— |

$682 | 4 |

| Subtotals (Item 0820) |

($2,738) |

($682) | (38) |

| Electricity Oversight Board (Item 8770) | |||

| Augment and reorganize staff by function to improve market oversight |

— |

$983 | 7 |

| Green Team activities |

$512 |

— | 4 |

| Contract funds for the University of California Energy Institute for market research |

— |

500 | — |

| Reauthorize expired positions |

— |

249 | 3 |

| Contract funds for legal services |

— |

75 | — |

| Subtotals (Item 8770) |

($512) |

($1,807) | (14) |

| Totals | $1,138,584 | $51,447 | 98.5 |

We have withheld recommendation on most of the funding requested, including the $1 billion set-aside, pending receipt and review of information justifying the proposed expenditures. For the Air Resources Board diesel engine grant proposal, we have recommended that, given the policy implications involved, the Legislature delete the $100 million request from the budget bill and adopt the proposal in separate legislation if it wants to fund the program. An overview of all the energy-related proposals can be found in the "Crosscutting Issues" section of the "General Government" chapter of the Analysis of the 2001-02 Budget Bill.

In addition to these proposals in the Governor's budget, the Legislature convened in a special session on electricity beginning in January. At the time this analysis was written, the special session was continuing and the Legislature had approved several bills related to the state's electricity crisis.

State Purchases of Electricity. On January 17, 2001, the Governor declared a state of emergency in response to the financial condition of Pacific Gas and Electric and Southern California Edison. The Governor ordered the Department of Water Resources (DWR) to buy electricity for these two utilities to meet customer demand. Under this emergency authority, DWR spent $150 million buying electricity.

Subsequently, two special session bills were enacted authorizing the state to purchase and sell electricity. These bills are:

As the state began negotiating cheaper long-term contracts, pursuant to AB 1x, DOF submitted a deficiency request to the Legislature for an additional $500 million. Thus, the state had committed to $1.6 billion from the General Fund to buy electricity at the time this analysis was written.

Assembly Bill 1x also authorized DWR to issue revenue bonds to help finance the cost of the state's electricity purchases. These bonds would be used in part to reimburse the General Fund for the funds already committed for this purpose, presumably before the end of the current year. In addition, the bonds would prospectively finance the difference between the actual cost DWR pays for electricity and the rate consumers pay. A portion of ratepayers' payments will be designated to pay off these bonds.

Other Legislation. In addition to these two bills, the Legislature has also revised some provisions of the original restructuring legislation. Chapter 1x, Statutes of 2001 (AB 5x, Keeley), replaced the 26-member stakeholder board of ISO with a five-member board of gubernatorial appointees. Board members cannot be affiliated with any participants in the electricity market and do not require Senate confirmation.

Chapter 2x, Statutes of 2001 (AB 6x, Dutra), prohibits the utilities from selling any more power plants until January 1, 2006. Remaining utility-owned power plants are to be dedicated to providing electricity to utility customers.

The state owns a vast amount of infrastructure—including nearly 2.5 million acres of land, 180 million square feet of building space, and 15,000 miles of highways. Much of this infrastructure is aging. For example, 55 million square feet in the three public higher education segments was built or renovated over 30 years ago and most of the 9.5 million square feet of buildings in the state hospitals and developmental centers was built over 40 years ago.

Budget Bill Proposal. The budget includes nearly $2 billion for the state's infrastructure (excluding highways and rail programs). As shown in Figure 10, over 40 percent of the proposal is for higher education with the next largest amounts in health and human services and resources. Nearly all of the amount under health and human services is for one project—a new 1,500 bed sexually violent predator facility in Coalinga (Fresno County) for the Department of Mental Health.

| Figure 10 | |||

| State Capital Outlay Program | |||

| 2000-01 and 2001-02 (In Millions) | |||

| 2000-01 Appropriations |

2001-02 Governor's Budget |

Difference | |

| Legislative, Judicial, and Executive |

$69.2 |

$19.2 | -$50.0 |

| State and Consumer Services |

54.7 |

141.7 | 87.0 |

| Business, Transportation (excluding highways and rail), and Housing |

26.9 |

170.7 | 143.8 |

| Environmental Protection |

0.3 |

3.1 | 2.8 |

| Resources |

972.2 |

287.1 | -685.1 |

| Health and Human Services |

18.7 |

360.0 | 341.4 |

| Youth and Adult Corrections |

123.7 |

115.3 | -8.4 |

| Education |

8.0 |

2.6 | -5.5 |

| Higher Education |

826.1 |

862.3 | 36.2 |

| General Government |

11.3 |

32.0 | 21.6 |

| Totals | $2,111.0 | $1,993.9 | -$116.2 |

Nearly 50 percent of the amount proposed in the budget is for pay-as-you-go funding. Of this amount about $758 million is from the General Fund, with the balance from special funds and federal funds. These direct appropriations are for 32 agencies for a variety of proposals—such as land acquisition, new courthouses, fire stations, research institutes, and various infrastructure and building improvements. Bond financing totals $1 billion, consisting of general obligation bonds ($667 million) and lease payment bonds ($349 million). The proposed general obligation bonds primarily finance projects for higher education ($554 million) and resources ($113 million). The proposed $349 million in lease payment bonds would finance the sexually violent predator facility mentioned above.

Bond Debt. The state's debt payments on bonds will be about $3.2 billion in the budget year. This is an increase of 10 percent over current-year payments. The payments include $2.6 billion for general obligation bonds and $574 million for lease-payment bonds. We estimate that the amount of debt payments on General Fund-backed bonds as a percent of General Fund revenue (that is, the state's debt ratio) will be 3.8 percent in the budget year.

Implementing the California Infrastructure Plan. Addressing the issues of an aging infrastructure and population growth will require expenditures of billions of dollars to renovate existing infrastructure and develop new public infrastructure. A significant step toward developing a process to address this issue was the enactment of Chapter 606, Statutes of 1999 (AB 1473, Hertzberg)—The California Infrastructure Planning Act. The act requires—beginning January 10, 2002 and annually thereafter—the Governor to submit to the Legislature a statewide five-year infrastructure plan and a proposal to fund it. The plan is to contain infrastructure needs of all state departments and public schools.

The new California Infrastructure Plan should provide the Legislature with more information on a statewide basis than it has had in the past. The specific information required to be included in the plan, however, may not be sufficient for the Legislature to assess whether or not the plan supports statewide infrastructure needs. We are also concerned that the Legislature will not receive the information in a timely manner. For example, the DOF issued a budget letter dated January 12, 2001, directing departments not to share capital outlay budget proposals and five-year plans with our office. This is contrary to the practice of over 30 years, whereby departments have sent the information to our office at the same time it is sent to DOF. This will severely limit our ability to conduct site visits of proposed projects and provide timely policy analysis and recommendations to the Legislature. This also greatly restricts the information available to the Legislature when it is asked to appropriate capital outlay funding. To address these concerns and to begin the Legislature's participation in the infrastructure planning process, we recommend the Legislature hold hearings this spring on the administration's process for developing the plan and on the way the plan can be used by both the administration and the Legislature to more effectively provide for the state's future infrastructure.

Funding Higher Education Capital Outlay. We continue to recommend that the Legislature fund the capital outlay program for the three segments of higher education based on statewide priorities and criteria, making use of appropriate construction cost guidelines, and on the basis of year-round operation (YRO) of facilities.

| Figure 1 | |

| LAO Recommended Priorities for Funding Higher Education Capital Outlay Projects | |

| Priority Order |

Description of Priority |

| 1 | Critical Fire, Life Safety, and Seismic Deficiencies |

| 2 | Necessary Equipment |

| 3 | Critical Deficiencies in Utility Systems |

| 4 | Improvements for Undergraduate Academic Programs |

| U New construction or renovations that increase

instructional efficiency, and are needed based on year-round operation. | |

| U Libraries. | |

| U Renovation of existing instructional buildings. | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| 5 | Research and Administrative Facilities |

| U Research laboratories. | |

| U Faculty and administrative offices. | |

| 6 | Integrity of Operationally Important Facilities |

| 7 | Support Facilities |

Background. The state system for providing health care services to the medically needy is comprised of a number of separate programs, the most significant of which are Medi-Cal, Healthy Families, Child Health and Disability Prevention (CHDP), and California Children's Services. The state also supports a number of public health programs targeted at certain diseases and certain populations with special health needs.

The 2001-02 Governor's Budget provides funding to continue the implementation of several recent efforts to expand the number of persons receiving health benefits through the Medi-Cal and Healthy Families Programs. It also proposes a new initiative to expand eligibility for Healthy Families to certain parents. The budget plan also proposes some new public health programs and the expansion of some existing ones. We summarize the major 2001-02 budget proposals below.

Medi-Cal. The Medi-Cal Program provides health care benefits to welfare recipients and to other qualified low-income persons, primarily families with children and the aged, blind, or disabled. Funding for the program is split about evenly between the state and the federal governments. The 2001-02 budget plan includes funding to continue implementation of major initiatives relating to Medi-Cal. These include (1) the expansion of health coverage to families, including working families with two parents, earning up to 100 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), and (2) the provision of benefits without a share of cost to all aged, blind, and disabled persons with current income equivalent to 133 percent of the FPL. The budget plan would also implement previously approved changes in Medi-Cal that would provide continuous eligibility for children up to 19 years of age and eliminate quarterly status reporting requirements for families.

Healthy Families. The Healthy Families Program implements the federal State Children's Health Insurance Program, in which each state dollar spent for persons eligible for health coverage is matched by about $2 in federal funding. Families pay a relatively low monthly premium and can choose from a selection of managed care plans for their children.

The 2001-02 Governor's Budget provides funding to continue an expansion of health coverage to children in families earning up to 250 percent of the FPL and to provide state-only benefits for children who are legal immigrants who do not qualify for federal funding because they entered the U.S. after August 22, 1996.

The Governor's budget plan includes a proposal to expand coverage under Healthy Families to parents of Health Families' eligible children with family income between 100 percent and 200 percent of the FPL. Funding would also be provided to expand coverage to parents of Medi-Cal eligible children who are ineligible or enrolled in Medi-Cal with a share of cost with incomes between 100 percent and 200 percent of the FPL, as well as parents with income below 100 percent of the FPL who do not qualify for Medi-Cal because of asset tests.

Public Health Programs. The budget plan provides funds to create or expand various public health programs. The funds would come from the General Fund and a proposed new trust fund comprised of monies from the settlement of tobacco litigation. Proposals include medical screening and treatment programs for prostate cancer and breast cancer, as well as programs to prevent youth from using tobacco and better tracking of infectious diseases.

Ensure Programs Work More Effectively. An estimated 5 million low-income people in California do not have health coverage. Of this total, about 1.6 million are uninsured low-income children and the remainder are parents and single adults who do not qualify for government health assistance and lack private coverage through their employers.

In recent years, the Legislature and the Governor have focused on efforts to reduce the number of uninsured children and adults and to improve access to health care for those who do have coverage. While the changes will expand health care coverage, the Legislature may wish to consider further steps to ensure that the state's complicated mosaic of health programs is working effectively—both separately and in combination with each other—to improve access to health care. Our analysis indicates that California's health care system remains fragmented and overly complex, with significant negative consequences for the health of California's medically needy and for state taxpayers. New health programs have been added or expanded over the years without full consideration of how the changes fit with the ones that were made before. This has led to a number of significant problems.

For example, while eligibility for coverage is being expanded, many persons who were already eligible for these programs are not being enrolled in them. A number of barriers continue to deter enrollment in health coverage, including requirements that parents and children enroll in different programs and be served by different health providers; asset tests to determine eligibility; and complicated application approval procedures. In a number of respects, California's public health care system is not operating much like a system at all. State-funded public health programs such as CHDP often fail to refer and help enroll their clients in more comprehensive coverage; incompatible computerized data systems and overlapping eligibility criteria lead to inefficiencies such as double-billing and added paperwork; and persons enrolled in coverage may encounter difficulty finding a doctor willing to accept them as patients.

Given this situation, the Legislature may wish to consider further steps to create a more comprehensive and effective health care system by improving the way existing state health programs work separately, and together, to provide medically necessary coverage. Opportunities for improving the state's health care system are summarized below and discussed in more detail in the Analysis.

Make CHDP a True "Gateway" Program. The CHDP program provides health screens and immunizations for California's low-income uninsured children. The program was also intended to serve as a gateway for children to enter a more comprehensive health care system provided by the Medi-Cal and Healthy Families Programs. However, the state has missed opportunities to establish CHDP as a gateway to better health coverage for these children and to use available federal funds to help support the cost of providing the care.

We recommend in the Analysis a number of steps to address this problem, including establishing new requirements for providers to encourage enrollment in Medi-Cal and Healthy Families, conforming CHDP income eligibility rules with those of the Health Families Program, improving data tracking systems, providing greater assistance to families in applying for coverage, and further simplifying the benefits application process.

Healthy Families Expansion. Our analysis indicates that the Governor's proposal to expand Healthy Families coverage to certain parents appears to meet the criteria needed to obtain the approval of the federal government, but misses some opportunities to further reduce the ranks of the uninsured and to conform and simplify the Healthy Families and Medi-Cal Programs.

In the Analysis, we outline an option for the Legislature to further expand coverage to parents in families earning up to 250 percent of the FPL in a way that would maximize the use of available federal funding. We also discuss an option of eliminating the asset test for determining eligibility for Medi-Cal, a step that would bring the Medi-Cal and Healthy Families Programs into closer conformity.

A More Rational Approach to Setting Medi-Cal Physician Rates. There is some evidence to suggest that the level of rates paid to physicians affects access to medical care. Our analysis indicates that the rates paid to physicians for Medi-Cal services are relatively low compared to those paid by other providers. Despite state and federal requirements, the state has not conducted annual rate reviews or made periodic adjustments to Medi-Cal rates to ensure reasonable access to health care services. Rate adjustments have generally been adopted on an ad hoc basis.

In the Analysis, we recommend that the Legislature establish a more rational process for setting Medi-Cal rates and for periodically reviewing and adjusting those rates. Medicare rates would be used as a benchmark in the interim. Later, a comprehensive analysis of access to physician services and the quality of care provided to Medi-Cal beneficiaries would become the basis for future rate adjustments.

Breast and Cervical Cancer Coverage. Federal legislation enacted last year gives California the opportunity to build on the limited services now available for low-income women who are diagnosed with breast or cervical cancer. Our analysis indicates that the state could coordinate its existing cancer screening programs with new Medi-Cal coverage options in a way that would simplify eligibility determinations, meet the health care needs of low-income individuals with cancer, and improve access to cancer screens for women with a high risk of cancer.

In the Analysis, we outline several options for the Legislature that would allow the state to address the current gaps in coverage of cancer treatment, drawdown available federal funding, better align eligibility among related programs, and expand the network of providers who could provide needed treatment services.

State and local governments spend more than $18 billion annually to fight crime. Local governments are largely responsible for crime fighting and thus, spend the bulk of total criminal justice monies for law enforcement activities. State expenditures have grown significantly in recent years, however, particularly for support of the state's largest criminal justice department, the California Department of Corrections (CDC). The CDC is responsible for the incarceration, training, education, and supervision in the community of adult criminals. Other state entities spend large sums of money on criminal justice activities as well, including the Departments of the Youth Authority and Justice; the courts; and the Office of Criminal Justice Planning (OCJP).

The budget proposes about $8.2 billion from the General Fund and other funds for support of criminal justice programs in the budget year, an increase of 3.8 percent over the current year.

The CDC accounts for the largest share of this funding, $4.8 billion, or about 5 percent more than the current-year amount. The CDC budget provides full funding for projected growth in the number of prison inmates and parolees under current law, as well as several program augmentations.

Other significant criminal justice General Fund increases include $40 million for a new War on Methamphetamine program in OCJP to provide noncompetitive grants to local law enforcement agencies within the Central Valley. The Governor also proposes $30 million for OCJP grants to local governments to improve local forensic laboratories for all but the City and County of Los Angeles which received a $96 million grant last year. Finally, the budget proposes $11.1 million to OCJP for two programs to fight high-technology crime.

Target Crime Fighting Based on Need. Between 1991 and 2000, California experienced a steep drop in crime. In fact, the 1998 rate was the lowest the state had experienced in over 30 years. In the last year, however, this trend reversed itself very slightly as the California crime index inched up by 1.3 percent. This increase was not distributed evenly across types of crimes, nor was it distributed evenly across jurisdictions. Instead, crime increases were registered primarily in Los Angeles metropolitan communities and other selected locales around the state.

These variations—both in the rates of increase or decrease as well as the locations—point to the need to target crime fighting efforts at specific locales based on need. This would be a more cost-effective approach for state funding than spreading resources across jurisdictions on a per-capita basis.

Correctional Spending Trends. Past declines in statewide crime rates have contributed to a slowdown in the growth of the state's correctional populations. The CDC continues to project a slowing rate of growth, but has not yet taken into account the effect of Proposition 36, the Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act, enacted by the voters in 2000. Our review indicates that inmate growth rates will be slower than projected and, when coupled with the effects or Proposition 36, will actually decline slightly between the current and budget year. Youth Authority wards and parolees also are expected to decline slightly.

With regard to spending for correctional programs, the Governor's budget contains no significant initiatives or major expenditure changes. Instead, it provides modest program enhancements and reforms for medical care, substance abuse, and mental health in both the CDC and Youth Authority budgets.

The CDC has taken steps to screen and provide specialized services to inmates with developmental disabilities, in response to a recent court case. We point out, however, that CDC's plan fails to address the community service needs of parolees with similar disabilities. To ensure that these parolees receive such services, it will be necessary for the department to examine their service needs and develop a follow-up plan.

Focus State's Crime-Fighting Role. Because law enforcement is primarily a local responsibility, it is important for the state to carefully delimit an appropriate role for itself. In our view, some of the Governor's proposals would unnecessarily overlap the responsibilities of different state agencies for targeted crimes. For example, the new War on Methamphetamine program proposed for OCJP would overlap the Department of Justice's existing statewide effort to combat methamphetamine production, trafficking, and use. In addition, some proposals such as those directed at high-technology crime and identity theft, would significantly expand the state's involvement in local law enforcement activities. Alternatively, we recommend targeting funds on those functions that would benefit from centralized statewide development, such as database and research support or training. Finally, some proposals fail to consider alternative funding sources or give inadequate attention to the desired state funding approach, described above, of awarding competitive grants based on demonstrated local need.

Question of State Support for Trial Courts Needs Resolution. The state General Fund now contributes over $1.2 billion toward the cost of trial court operations. This is a result of recent legislation that transferred responsibility for court operations and personnel systems from counties to the state. One issue which the Governor's budget does not address is whether and under what circumstances responsibility for court facilities also should be transferred to the state. In our view, state responsibility for those facilities would be consistent with prior legislative actions in the area of court operations and personnel.

This issue of facility responsibility is one which deserves immediate legislative attention for several reasons. First, until this issue is resolved, some counties are likely to continue to backlog deferred maintenance, thereby resulting in continued facility deterioration. Second, facility transfer poses a potentially huge funding liability to the state's General Fund. The current annual cost of supporting court facilities is estimated at $119 million (which would be offset by $80 million to $90 million in county maintenance-of-effort agreements). The larger cost, however, is the estimated future capital funding needs which are estimated in the multibillion dollar range over the next 20 years.

Because of the fiscal implications and complexity of the task, we recommend enactment of legislation that would carefully detail and streamline the process of transferring the court facilities from the counties to the state. The legislation should also carefully define state and county responsibilities so as to appropriately limit the state's future funding liability. In addition, we recommend a number of ways to develop a strategy for the state to use in dealing with the escalating costs of state support for court operations and personnel.

Intercity Rail Program. The state supports and funds intercity passenger rail services on three corridors—the Pacific Surfliner (formerly the San Diegan) in Southern California, the San Joaquin in the Central Valley, and the Capitol in Northern California. Intercity rail services primarily serve business and recreational travelers going between cities in California and to other parts of the country.

The state contracts with Amtrak for the operation and maintenance of the intercity rail service. In 2000-01, state operating costs for intercity rail services are about $64 million.

Caltrans Issues Ten-Year Rail Plan. In October 2000, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) issued its statutorily required ten-year passenger rail plan, covering the period from 1999-00 through 2008-09. The plan calls for a substantial expansion of state-supported intercity rail service over ten years in order to improve customer service. Specifically, the plan envisions $3.2 billion in capital improvements over ten years, including track and signal improvements, as well as maintenance facilities. In general, these improvements are expected to increase on-time performance, reduce travel times between stations, and expand track capacity for additional round trips between cities. The plan also forecasts annual state operating costs to increase to $118 million by 2008-09, mainly due to additional round-trip services on existing corridors and the start of service on new corridors.

Budget Request Begins to Implement Ten-Year Plan. For 2001-02, Caltrans requests substantial funds from the Public Transportation Account to make capital improvements and to expand rail service on two corridors in order to carry out the rail plan. For capital improvements, the budget requests $98 million for the following:

For service expansion, the budget requests $9.5 million for the following:

The Legislature should consider the following two factors when assessing the budget proposal in the near term, and Caltrans' ten-year rail plan in the long term: (1) what it wants the state's role to be in funding intercity rail vis-a-vis commuter rail and (2) the extent to which proposed capital improvements and service expansions are justified by ridership performance.

Current State and Local Passenger Rail Roles Blurred. Chapter 622, Statutes of 1997 (SB 45, Kopp) defined the state's role in mass transportation as primarily providing for interregional transportation while local agencies are responsible for regional services. As a result, Caltrans concentrates on providing intercity rail service, while leaving regional services to commuter and urban rail systems run by regional and local agencies. Commuter rail generally offers frequent service during the commute hours throughout a metropolitan region and may cover a number of cities. Urban rail generally provides regular service throughout the day.

The distinction, however, between state and local responsibilities has started to blur. For example, on portions of the Pacific Surfliner corridor, state-supported rail transportation is in direct competition with regional commuter rail systems. Specifically, between Oceanside and San Diego, the Surfliner travels the same corridor with the Coaster, a regional commuter rail system. North from Oceanside to downtown Los Angeles, the Surfliner shares tracks with Metrolink, another commuter rail service.

The blurring of responsibilities is also found in northern California. For example, the San Joaquin corridor provides daily service between Stockton and Oakland, while the Altamont Commuter Express—another regional commuter rail service—provides daily round trips between Stockton and San Jose.

The increased investments proposed for intercity rail further blur the distinction between the state-supported intercity rail program and regional commuter rail systems. This is because Caltrans' plan to expand the intercity rail service, through adding more round trips particularly at commute hours, moves the state closer to providing regional commuter rail service. Essentially, this moves the state further away from the policy established under Chapter 622 which envisions the state providing interregional rail service while local agencies provide regional service. If the Legislature determines that the state's responsibility should continue to be interregional transportation, then as intercity rail investment decisions

are made, the Legislature should consider whether capital and service enhancements primarily benefit interregional or regional mobility.

Justification for Intercity Rail Enhancements Depend on Ridership Performance. A key reason to make rail capital improvements is to increase the number of passengers who ride the system. According to Caltrans, the proposed track and signal projects in the Governor's budget would increase track capacity, thereby enabling an increase in round-trip service that would generate more riders. Therefore, the decision whether to invest in additional capital improvements should be based on evidence that the increased expenditures will increase ridership.

Of the $3.2 billion in capital improvements proposed in the rail plan, $2.6 billion are for improvements on the three existing intercity rail corridors. With these investments, the plan projects ridership to increase by 84 percent (from 2.9 million in 1999-00 to 5.4 million in 2008-09).

The projected ridership increase is likely to be overstated, however. The increase—at an average annual growth rate of 7 percent—is significantly higher than the average growth rate (2.9 percent) experienced between 1990-91 and 1999-00. Furthermore, in the past, Caltrans has been too optimistic in its intercity rail ridership projections. For instance, from 1997-98 through 1999-00, actual ridership was between 7 percent and 18 percent below the department's ridership projections.

Our review also shows that an increase in round-trip service on two of the three corridors has not resulted in a corresponding ridership increase in recent years. For instance, between 1990-91 and 1999-00, additional capital improvements were made to the Pacific Surfliner corridor and round-trip services expanded from 8 to 11 per day. Yet, over this period, ridership on the Surfliner either fell or remained relatively flat, largely because of alternative commuter rail service being available within the same corridor. As for the San Joaquin corridor, a large increase in total ridership occurred in 1996-97 and 1997-98, after four years of no expansion in round-trip service. However, when a new round trip was added in 1998-99, ridership remained flat for two consecutive years.

Analyst's Recommendation. Capital improvements to the intercity rail services are warranted to the extent the improvements lead consistently to more use by riders. However, as discussed above, increased service on both the Pacific Surfliner and the San Joaquin in recent years, facilitated by various capital improvements, have not generated a commensurate increase in riders. Accordingly, we recommend that the capital projects proposed for the two services in 2001-02 not be funded.

For primarily the same reason, we recommend that the request for $4.2 million to add a sixth round-trip on the San Joaquin corridor not be funded. Our review shows that while ridership dropped by 4.4 percent between 1997-98 and 1999-00, state costs to support the San Joaquin service increased by 50 percent from about $24 to over $36 per passenger. As a result, expending additional funds to expand round-trip service does not seem warranted at this time.

State Faces Major Water-Related Problems. The state faces a number of water-related problems, including (1) various issues related to the San Francisco Bay/Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta Estuary (the Bay-Delta) and (2) the existence of a large number of seriously polluted water bodies statewide.

Bay-Delta Problems. The CALFED Bay-Delta Program (CALFED) was formed in 1995 to address the interrelated water problems in the Bay-Delta, including inadequate water quality, declining fish and wildlife populations, deteriorating levees, and uncertain water supplies. This program is a consortium of 18 state and federal agencies that have regulatory authority over water and resource management responsibilities in the Bay-Delta. Since 1995, the program has been developing a planning framework to address these water-relater problems. The planning process culminated in August 2000 with the signing of the "Record of Decision" (ROD) by the lead CALFED agencies. The ROD guides the first seven years of the program's implementation at an estimated cost of $8.5 billion. The ROD allocates costs among federal, state, and user/local sources.

The existing organizational structure of CALFED, currently housed in the Department of Water Resources (DWR), is loosely configured. This reflects the fact that the program has evolved administratively and has not been spelled out in state statute.

Seriously Polluted Water Bodies. Under federal law, states are required to develop plans to address pollution in the state's most seriously impaired water bodies. These plans—called Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs)—are developed for each pollutant contributing to the pollution problem. The TMDLs allocate responsibility for reducing pollution among the various sources of pollution. Currently, there are 509 water bodies on the state's most recent list of impaired water bodies, requiring the development of 1,471 TMDLs.

The CALFED Bay-Delta Program. The budget proposes $414 million of state funds—spread throughout seven state departments—for CALFED-related programs in 2001-02. Of this amount, $94 million is from the General Fund and the balance is mainly from bond funds. The program is divided into 11 program elements. As in the current year, the largest state expenditures are proposed for ecosystem restoration ($161 million) and water storage ($56 million, of which $19 million is for studies to be conducted by DWR). In addition, the budget proposes about $30 million for the Environmental Water Account (EWA). The EWA is a new concept that would involve the state buying water to hold in reserve to release when needed for fish protection.

The TMDL Program. The budget proposes about $12 million (mainly General Fund) for the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) to develop TMDLs. In addition, the budget proposes about $1.6 million for the Department of Pesticide Regulation to assist SWRCB in developing TMDLs. These proposed expenditures represent no change from estimated expenditures in the current year.

The CALFED Bay-Delta Program. As part of its review of CALFED-related proposals, the Legislature should consider the following:

The TMDL Program. Our review finds that the state lags in developing TMDLs, has no long-term work plan, and is spending ten times the national average to develop each plan. The slow pace of developing TMDLs has potentially serious consequences, including delays in improving water quality, a loss of federal funds, and federal takeover of aspects of the state's water quality program.

We find that there are a number of efficiencies and improvements that would make the TMDL program more effective and timely while reducing the costs of the program. In this regard, we recommend enactment of legislation to (1) require greater policy direction from SWRCB to the regional water quality control boards (the entities mainly responsible for developing TMDLs) and (2) streamline the TMDL approval process. Greater policy direction from SWRCB is needed to address a general perception in the regulated community that regional board decisions related to TMDLs are made arbitrarily. If this perception is not addressed, further delays and costs in TMDL development are likely because TMDL decisions are more likely to be challenged in court. Finally, to enable legislative evaluation of the program's funding requirements, the Legislature should require SWRCB to develop a ten-year work plan and budget for the program.

State employees (other than those in higher education) last received a general pay increase of 4 percent on September 1, 2000. Figure 12 shows a history of general salary increases for state civil service employees and the consumer price indices for the United States and California since 1981-82.

| Figure 12 | |||

| State General Salary Increases | |||

| 1981-82 Through 2001-02 | |||

| Consumer Price Indices | |||

| Fiscal Year | State General Salary Increases |

United States | California |

| 1981-82 |

6.5% |

8.8% | 10.7% |

| 1982-83 |

— |

4.2 | 2.3 |

| 1983-84 |

6.0 |

3.7 | 3.6 |

| 1984-85 |

8.0 |

3.9 | 4.9 |

| 1985-86 |

6.0 |

2.9 | 4.0 |

| 1986-87 |

6.0 |

2.2 | 3.3 |

| 1987-88 |

3.8 |

4.1 | 4.2 |

| 1988-89 |

6.0 |

4.6 | 4.8 |

| 1989-90 |

4.0 |

4.8 | 5.0 |

| 1990-91 |

5.0 |

5.5 | 5.3 |

| 1991-92 |

— |

3.2 | 3.6 |

| 1992-93 |

— |

3.1 | 3.2 |

| 1993-94 |

5.0 |

2.6 | 1.8 |

| 1994-95 |

3.0 |

2.9 | 1.7 |

| 1995-96 |

— |

2.7 | 1.4 |

| 1996-97 |

— |

2.9 | 2.3 |

| 1997-98 |

— |

1.8 | 2.0 |

| 1998-99 |

5.5 |

1.7 | 2.5 |

| 1999-00 |

4.0 |

2.9 | 3.1 |

| 2000-01a |

4.0 |

3.0 | 4.0 |

| 2001-02b |

—b |

2.3 | 2.8 |

| a Legislative Analyst's Office estimate of consumer price indices. | |||

| b To be determined through collective bargaining. | |||

State Civil Service Employees. The Governor's budget does not include any budget-year funding for employee compensation. However, the Department of Personnel Administration (DPA) will begin collective bargaining negotiations to replace the expiring memoranda of understanding (MOUs) this spring. As a result, we anticipate the state will face increased compensation costs in 2001-02. Based on current salary levels, we estimate that a 1 percent salary increase for state employees increases General Fund costs approximately $55 million.

Employees in Higher Education. In higher education, the Governor's budget proposes $131 million for UC and $96 million for CSU for employee compensation to provide salary and benefit increases to faculty and staff. Figure 13 shows how these amounts would be allocated.

| Figure 13 | |

| Higher Education Proposed Compensation Increases | |

| General Fund (In Millions) | |

| University of California | |

| Merit salary increases |

$43.0 |

| Average 2 percent cost-of-living increase |

38.4 |

| Full-year cost of 2000-01 salary increases |

19.5 |

| Health benefit cost increases |

13.1 |

| Parity adjustments for staff and nonfaculty academic employees |

10.0 |

| Parity adjustments for faculty |

7.1 |

| Subtotal |

($131.1) |

| California State University | |

| 4 percent compensation pool (effective July 1, 2001) |

$81.5 |

| Health and dental benefit cost increases |

13.2 |

| Full-year cost of 2000-01 salary increases |

1.5 |

| Subtotal |

($96.2) |

| Higher Education Total | $227.3 |

Current Status of Negotiations. In September 1999, the Legislature approved MOUs for all of the state's 21 collective bargaining units. (This does not include employees in higher education.) These agreements are effective until June 30, 2001. The new MOUs provided 4 percent general salary increases effective July 1, 1999 and September 1, 2000. For employees not covered by collective bargaining (such as managers and supervisors), DPA approved a compensation package similar to that approved in the MOUs. As noted above, DPA will begin negotiations for new MOUs with the unions representing the 21 bargaining units this spring.

Strengthen Legislature's Collective Bargaining Oversight. The Ralph C. Dills Act directs the administration and employee representatives to endeavor to reach agreement before adoption of the budget act for the ensuing year. The act further specifies that provisions of MOUs requiring the expenditure of state funds be approved by the Legislature in the annual budget act before the provisions may take effect. Historically, however, agreements often have not been reached in time for legislative consideration as part of the budget process. Instead, the Legislature has received MOUs for approval late in the session. In addition, assessments of the total cost of the MOUs have not always been available or complete for consideration with the proposals.

To ensure that the Legislature has the opportunity to appropriately review any proposed MOUs, we recommend that the

Legislature (1) require a minimum 30-day review period between the submittal of proposed MOUs to the Legislature and hearings

on the proposals to ensure that their fiscal and policy implications are fully understood and (2) review the administration's MOU

proposals during budget hearings and adopt them in the annual budget act (or as amendments to the act if they are not available for

review during budget hearings).

Return to Perspectives and Issues Table of Contents,

2001-02 Budget Analysis