Analysis of the 2001-02 Budget BillLegislative Analyst's Office

|

| How Has Realignment Affected Mental Health, Social Services, and Health Programs? How Can Realignment Be Improved? |

| Summary

In 1991, the state enacted a major change in the state and local government relationship, known as realignment. In the areas of mental health, social services, and health, realignment transferred programs to county control, altered program cost-sharing ratios, and provided counties with dedicated tax revenues from the sales tax and vehicle license fee to pay for these changes. This report summarizes the major components of realignment, evaluates its effectiveness, and provides recommendations to improve its administration. Realignment has been a largely successful experiment in the state-county relationship. Its dedicated revenue stream has helped to create an environment of fiscal stability which improves program performance. The flexibility provided within realignment has allowed some counties to effectively prioritize their needs among many competing demands. Realignment could be improved by creating greater fiscal incentives to promote more efficient delivery of public services. Specifically, we propose a simplified system for allocating all new realignment dollars that would improve county incentives to control costs and increase local control. By emphasizing efficient fiscal incentives and performance accountability, realignment could serve as a useful model for future program changes in the state-county relationship. |

In 1991, the state enacted a major change in the state and local relationship—known as realignment. In the areas of mental health, social services, and health—realignment shifted program responsibilities from the state to counties, adjusted cost-sharing ratios, and provided counties a dedicated revenue stream to pay for these changes. While there have been other significant changes in the broader state-county relationship since the enactment of realignment, the effects of realignment over the past decade have not been reviewed in a comprehensive manner.

In this piece, we (1) summarize the major components of realignment, (2) evaluate whether realignment has attained its original goals and its ability to meet current and future needs of the state, and (3) provide recommendations to improve the workings of the state-local relationship in this area.

In 1991, the state faced a multibillion dollar budget problem. Initially responding to Governor Wilson's proposal to transfer authority over some mental health and health programs to counties, the Legislature considered a number of options to simultaneously reduce the state's budget shortfall and improve the workings of state-county programs. Ultimately, the Legislature developed a package of realignment legislation that:

The specific programs that were transferred and the changes in cost-sharing ratios are summarized in Figure 1 and discussed below.

| Figure 1 | ||

| Components of Realignment | ||

| Transferred Programs—State to County | ||

| Mental Health | ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Public Health | ||

| ||

| ||

| Indigent Health | ||

| ||

| ||

| Local Block Grants | ||

| ||

| ||

| County Cost-Sharing Ratio Changes | State/County Shares Of Nonfederal Program Costs (%) | |

| Prior Law | Realignment | |

| Health | ||

|

75/25 |

50/50 |

| Social Services | ||

|

95/5 |

40/60 |

|

76/24 |

70/30 |

|

97/3 |

65/35 |

|

84/16 |

70/30 |

|

100/0 |

75/25 |

|

100/0 |

70/30 |

|

89/11 |

95/5 |

|

50/50 |

70/30 |

| Local Revenue Fund | ||

| ||

| ||

| a The AFDC-FG&U program was subsequently replaced by CalWORKs. | ||

While closing the budget gap was a top priority at the time, the Legislature also relied on a series of policy principles in implementing the realignment changes, including:

In 1991, realignment transferred more than $1.7 billion in state program costs to counties, accompanied by an equivalent amount of realignment revenues. While eliminating state General Fund spending, the state maintained varying degrees of policy control in these areas. These programs, as detailed below, are now funded through realignment dollars and other county sources of funds.

In addition, realignment eliminated two block grants that had previously provided funding to counties. The County Justice Subvention Program had provided funding for local juvenile justice programs, and the County Revenue Stabilization Program had provided funding to improve the fiscal condition of smaller counties. At the time of realignment, the value of these block grants totaled $52 million. Counties received in their place an equal amount of realignment funding that could be used for juvenile justice, health, mental health, or social services programs.

As shown in Figure 1, realignment increased the county share of nonfederal costs for a number of health and social services programs. In two cases, the county share of costs was reduced. These programs are detailed below.

In order to fund the more than $2 billion in program transfers and shifts in cost-sharing ratios, the Legislature enacted two tax increases in 1991, with the increased revenues deposited into a state Local Revenue Fund and dedicated to funding the realigned programs. Each county created three program accounts, one each for mental health, social services, and health. Through a complicated series of accounts and subaccounts at the state level (described below), counties receive deposits into their three accounts for spending on programs in the respective policy areas.

Sales Tax. In 1991, the statewide sales tax rate was increased by a half-cent. The half-cent sales tax generated $1.3 billion in 1991-92 and is expected to generate $2.4 billion in 2001-02.

Vehicle License Fee. The VLF, an annual fee on the ownership of registered vehicles in California, is based on the estimated current value of the vehicle. In 1991, the depreciation schedule upon which the value of vehicles is calculated was changed so that vehicles were assumed to hold more of their value over time. At the time of the tax increase, realignment was dedicated 24.33 percent of total VLF revenues—the expected revenue increase from the change in the depreciation schedule.

In recent years, the Legislature has reduced the VLF tax rate. As of this year, the effective rate is 67.5 percent lower than it was in 1998. The state's General Fund, through a continuous appropriation to local governments outside of the annual budget process, replaces the dollars that were previously paid by vehicle owners. In other words, realignment continues to receive the same amount of dollars from VLF sources as under prior law. The VLF allocations to realignment have grown from $680 million in 1991-92 to an expected $1.2 billion in 2001-02.

The VLF Collections. In 1993, the authority to collect delinquent VLF revenues was transferred from the Department of Motor Vehicles to the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) in order to increase the effectiveness of delinquent collections. The first $14 million collected annually by the FTB is allocated to counties' mental health accounts as part of realignment. The distribution schedule is developed by the State Department of Mental Health in consultation with the California Mental Health Directors Association.

All counties are affected by realignment and receive funding from the two revenue sources. In addition, a few cities also receive realignment funding due to their historical responsibility for some of the realigned programs. Berkeley receives funding for both mental health and health programs. Long Beach and Pasadena receive funding for health programs. The Tri-City area (Claremont, LaVerne, and Pomona) receives funding for mental health programs.

The original allocations to each jurisdiction were based on their level of funding in these program areas just prior to realignment. These allocations, as of 1991, were in many cases rooted in historical formulas and spending patterns. For instance, funding for the AB 8 county health programs was based on county spending in the 1970s for such programs. As such, realignment did not represent an overhaul of the historical allocation formulas in these program areas. Instead, the realignment formulas emphasized maintaining the county funding levels in existence at the time of its enactment.

The realignment legislation established a revenue allocation system in which the total amount of revenues received in one year becomes the base level of funding for the following year for each jurisdiction (excluding the VLF delinquent collections allocation). For instance, a county's total realignment allocation in 1997-98 became its base level of revenues for 1998-99. Growth in revenues between the two years was then allocated based on a series of statutory formulas. Thus, a county's base revenues in 1998-99 plus any growth revenues received in that year becomes the base for 1999-00.

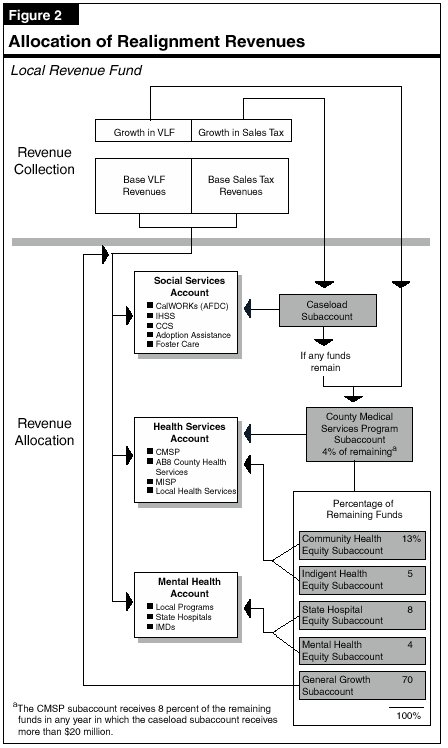

Figure 2 illustrates how these revenues are allocated. The allocation of growth revenues is described in more detail below.

Growth Revenues. Any amount by which the sales tax and VLF realignment revenues have grown is deposited into a series of state subaccounts, each associated with one of the mental health, social services, or health accounts of each county. Sales tax growth funds are first committed to the:

Any remaining sales tax growth funds and all VLF growth funds are allocated to the following subaccounts (which then flow back into one of the three main accounts, as noted in parentheses).

Figure 3 summarizes the specific distributions of revenues in 1998-99, when realignment revenues totaled $2.9 billion. In that year, the total amount owed the caseload subaccount exceeded the total growth in sales-tax revenues. Consequently, no other subaccount received funding from the sales tax growth in 1998-99, and the remaining 1998-99 caseload obligation is allocated from the 1999-00 sales tax growth. In those years where caseload allocations account for the entire amount of sales tax growth, VLF growth funds are allocated to the subaccounts in the same proportion as the 1996-97 allocations.

| Figure 3 | ||||

| Distribution of Realignment Revenues | ||||

| 1998-99 (In Millions) | ||||

| Account | ||||

| Mental Health |

Social Services |

Health | Total | |

| Base Revenues (from 1997-98) |

$888 |

$691 | $1,144 | $2,723 |

| Growth Subaccounts | ||||

| Caseload |

$96 |

$96 | ||

| CMSP |

— |

— | $9 | 9 |

| Community Health Equity |

— |

— | 11 | 11 |

| Indigent Health Equity |

— |

— | 5 | 5 |

| State Hospital Equity |

$6 |

— | — | 6 |

| Mental Health Equity |

4 |

— | — | 4 |

| General Growth |

25 |

5 | 29 | 59 |

| Totals | $923 | $792 | $1,197 | $2,912 |

| VLF Collections | $14 | — | — | $14 |

| Total Revenues | $937 | $792 | $1,197 | $2,926 |

| Note: Totals may not add due to rounding. | ||||

Although funds are deposited into the three separate accounts in each county, the realignment statute allows for transfers of dollars among these accounts in certain circumstances. These transfers allow counties to adjust program allocations to best meet their service obligations.

Each county is allowed to transfer up to 10 percent of any account's annual allocation to the other two accounts. In order to take advantage of this provision, the county must document at a public meeting that the decision is being made to ensure the most cost-effective provision of services. Each county may transfer an additional 10 percent from the health account to the social services account under specified conditions. Each county may also transfer an additional 10 percent from the social services account to the mental health or health accounts under specified conditions. All transfers apply for only the year in which they are made, with future allocations based on the pre-transfer amounts.

At the time of the enactment of the realignment statutes, it was unclear whether the legality or constitutionality of any of the components would be challenged. Therefore, a series of "poison pill" provisions were put into place that would make components of realignment inoperative under specified circumstances. These provisions are still active and fall into three types.

Reimbursable Mandate Claims. If, as a result of the realignment provisions, (1) the Commission on State Mandates adopts a statewide cost estimate of more than $1 million or (2) an appellate court makes a final determination that upholds a reimbursable mandate, the general provisions regarding realignment would become inoperative.

Constitutional Issues. Although local entities receive their realignment VLF allocations as general purpose revenues, the realignment statute requires that each entity must then deposit an equal amount of revenues into their health and mental health accounts. Section 15 of Article XI of the State Constitution requires VLF revenues to be subvened to cities and counties. If a final appellate court decision finds that the realignment provisions related to VLF deposits violate the Constitution, the VLF tax increase from 1991 would be repealed.

Similarly, if a final appellate court decision finds that revenues from the half-cent realignment sales tax are subject to Proposition 98's education funding guarantee, this portion of the sales tax would be repealed.

Court Cases Related to Medically Indigent Adults. If a final appellate court decision finds that the 1982 legislation that transferred responsibility from the state to counties for providing services to medically indigent adults constitutes a reimbursable state mandate, the VLF increase would be repealed.

If any of these poison pill provisions were to take effect, the affected statute would become inoperative within three months, with the precise timing dependent on the particular provision.

Below we analyze the impacts of realignment in detail for each of the three areas affected—mental health, social services, and health programs. We have focused upon the major programs and therefore, do not discuss every program funded by realignment. We also discuss several realignment issues which cut across the program areas.

The realignment of mental health programs has accomplished most of its original intended purposes. The relative fiscal stability and flexibility that has resulted from the shift of funding and program responsibilities from the state to the counties has encouraged efficiency and innovation while resulting in modest revenue growth. However, significant concerns remain regarding efforts to have the state measure and track the performance of the counties in using the funds.

As was noted above, the Legislature had a number of programmatic and fiscal goals in enacting the realignment of mental health care programs. Our review of expenditure and caseload data over the last decade and discussions with state and county officials strongly suggests that most of the original intended purposes of realignment have been accomplished.

Mental Health Funding Once Vulnerable. Before the enactment of realignment, state funding for local mental health services was subject to annual legislative appropriation, which could vary significantly from year to year depending upon the state's financial condition. Because 90 percent of so-called Short-Doyle grant funding for mental health programs generally came from the state (with the remaining 10 percent funded by the counties), local mental health services were particularly vulnerable to reductions when the state was faced with financial shortfalls. In 1990-91, for example, state expenditures for community mental health programs declined by about $54 million or 8.6 percent below the prior-year's spending level.

At the time that realignment legislation was considered, mental health program experts had voiced concern that the uncertainty created by the annual state appropriations process was harmful to the development of sound community programs. The significant year-to-year swings in funding levels and uncertainty in the state budget process were also said to have discouraged county government officials from making the multiyear commitments needed to develop innovative programs. Before a pioneering new program could be staffed, made operational, and fully developed over several years, a county mental health department was at risk of having to scale back the commitment of funding and personnel for such efforts. The intent of realignment was to provide mental health programs stable and reliable funding through a dedicated revenue source in order to foster better planning and innovation.

Program Flexibility Was Constrained. The lack of flexibility provided to counties to use the resources available to them in the most cost-effective and medically effective manner was also a concern at the time realignment was considered. For example, prior to realignment each county was given a set allocation of beds for seriously mentally ill patients receiving a civil commitment to the state mental hospital system under the Lanterman-Petris-Short (LPS) Act. Counties were also allocated state-funded nursing care beds known as Institutions for Mental Diseases (IMDs). A county mental health department did not have the option of using fewer LPS or IMD beds and instead using the money for much less-costly (and in some cases potentially more medically effective) community-based treatment programs. In effect, counties were required to "use or lose" their allocation of LPS or IMD beds even if more cost-effective options were available.

Counties were also concerned that much of the state funding for their mental health systems was in the form of categorical programs, by which specific state grants were restricted for use for programs assisting specific target groups of mentally ill individuals. This categorical funding approach limited the ability of county mental health systems to meet the specific mental health needs of their communities and to combine funding from various programs to coordinate services.

The realignment plan was intended to provide additional flexibility to the counties in their use of state funding. For example, the realignment plan directly allocated to county mental health systems the funding for LPS beds within the state hospitals and for IMDs. Counties were free to continue to use the funds for the same number of LPS or IMD beds as before. With advance notice to the state, however, they could use fewer beds than previously allocated and use the savings for other components of their community-based programs. The realignment plan also eliminated some categorical community-based mental health programs, including the Community Support System for Homeless Mentally Disabled Persons and the Self-Help for Homeless programs. The counties were free either to continue the programs using realignment funds or to reallocate the funds to other purposes.

System Accountability Deemed Lacking. Finally, the enactment of realignment was intended to provide more effective state supervision and oversight of local mental health programs. While the state had long collected fiscal and program activity data about community-based mental health programs, state policymakers had voiced concern that the state had little information about the effectiveness of the county programs it had been funding. For these reasons, the realignment legislation expressed the intent that the state implement an effective data system that would measure such performance outcomes.

Funding Stability Did Improve. The realignment plan adopted by the Legislature and Governor (as shown in Figure 4) addressed concerns over the lack of funding stability for community-based mental health programs by shifting a share of sales tax and VLF revenues to counties along with the primary fiscal responsibility for operating those programs. Since an initial shortfall caused by the state's recession, the total amount of state revenues redirected to county-run mental health programs under realignment has grown fairly steadily. Mental health realignment funding is anticipated to exceed $1 billion in the current fiscal year, an increase of more than $350 million since 1991-92 and an average annual growth rate of 6 percent.

| Figure 4 |

| The Results of Mental Health Realignment |

Improved Program Efficiency and Flexibility. The implementation of realignment has generally succeeded in establishing better coordinated, more flexible, and less costly mental health programs in the community. The evidence suggests that counties have been successful in shifting their treatment strategy so that fewer clients receive treatment in costly mental health hospitals and other long-term care facilities and more clients are served with a potentially more effective treatment approach in less costly community-based outpatient and day-treatment programs.

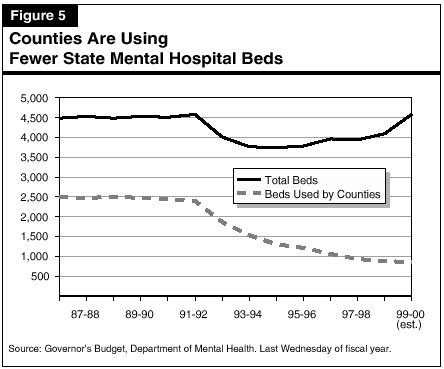

As shown in Figure 5, county LPS placements in state mental hospital beds dropped dramatically after the enactment of realignment—from about 1,900 in 1992-93 to about 850 today. The number of patients placed in IMDs has also dropped. Before realignment was enacted, almost 3,900 mentally ill persons were in IMD beds at any given time. The DMH recently estimated the IMD population to be about 3,500.

County expenditure reports document that the funds saved by scaling back inpatient care have shifted to outpatient treatment. In 1991-92, when realignment was enacted, county mental health program expenditures for outpatient care were about $300 million, about 32 percent of their total spending. By 1997-98 (the most recent year for which statewide data is available), $666 million was being spent on outpatient care, and these expenditures represented 42 percent of their total spending. Realignment funding played a critical role in this expansion of outpatient care. About $72 million in realignment funding was used to support outpatient care programs in 1991-92. By 1997-98, this amount had almost quadrupled to $265 million.

County officials have indicated that the new flexibility they gained under realignment has allowed them to launch experimental community-based programs to better coordinate services for their clients and to establish new types of services that were previously unavailable. Los Angeles County, for example, initiated an effort to coordinate the services its mental health programs provide to adults and children with other social services agencies within targeted neighborhoods. San Diego County established "clubs" for mentally ill clients in the community where they receive peer counseling and other nontraditional support services. Riverside County created special teams of county staff members to respond to the crises of individual patients in the community and divert them from commitment to expensive inpatient beds. Some of these experimental programs might not have been possible without realignment's elimination of some categorical programs.

Non-Realignment Policy Changes Have Also Influenced Program Changes. These major changes in mental health programs over the past decade should not be attributed to realignment alone. A number of other significant changes to the structure and finances of county mental health systems have occurred since the enactment of realignment. These include the establishment of a statewide program of managed care for mental health services under the Medi-Cal Program and the resulting consolidation of fee-for-service Medi-Cal services with the county mental health system in each county. In addition, the statewide Medi-Cal plan was amended to allow a broader array of mental health services, including case management, to be reimbursed under the Medi-Cal Program. Other key changes have been the dramatic expansion of mental health services for children under the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program and the commitment of additional state funds to expand services for homeless mentally ill persons.

County officials indicate that, in a number of cases, the availability of realignment funding has enabled them to take full advantage of these other changes in the mental health system to expand their services and caseloads. For example, county officials have indicated that they have used realignment funding to expand rehabilitative services for mentally ill persons who are eligible for Medi-Cal. Because the federal government is obligated to pay for half the cost of Medi-Cal services, counties are in a position to "buy" more mental health services for less money by effectively leveraging the realignment funds available to them.

Accountability System Still Needs Improvement. Implementation of realignment has yet to result in a significant improvement of the state's oversight of the provision of community-based mental health services. Several efforts are progressing to establish new, standardized measures by which to judge the performance and quality of county mental health programs. A committee of state and county officials and mental health program providers appears to be nearing completion of an initial list of agreed-upon performance measures providing data on the cost of services, client and family satisfaction, client retention rates, and other factors. Another committee continues to examine the process by which counties would be held accountable for their performance. Also, a new statewide computerized Client and Service Information System (CSIS) is coming on-line, providing more up-to-date information on a statewide basis regarding the demographics, diagnoses, and treatment outcomes of mental health clients. As of September 2000, about 49 counties were in compliance with state CSIS data-reporting rules.

However, completion of these efforts is long overdue. The establishment of statewide performance outcome measures was initially to have been completed by 1992-93. More recent legislation requires that measurements of access and quality for mental health care provided in community-based programs be developed by an undetermined date, with a status report to the Legislature by March 2001. Despite the progress made to date, it remains unclear when and if these efforts will lead to an effective statewide system providing rewards for counties with exemplary programs and appropriate consequences for counties that do not meet minimum performance standards.

Not All Mentally Ill Are Served. Realignment was intended to help stabilize mental health funding, and also enable some marginal growth in county systems. Realignment, however, was not meant to close the gap in meeting the state's full mental health service needs, and it has not done so. Given recent estimates that 600,000 seriously mentally ill persons annually lack needed mental health services, substantial additional funding might be needed to accomplish such an expansion.

Realignment increased the county share of nonfederal costs for certain health and social services programs, and reduced the county share for others. These increased shares of costs in a number of programs, paired with limited funds for new cases, were initially intended to create incentives for counties to control costs. However, early legislative changes to the realignment program largely negated realignment's cost control incentives. Although realignment altered the costs shared between the state and counties for cash assistance programs, the changes implemented by welfare reform have overshadowed the impact of realignment in this area.

Our analysis focuses on the major social services programs affected by realignment—specifically, foster care, IHSS, and AFDC/CalWORKs. These three programs accounted for 85 percent of realignment's net shift in social services costs in 1991.

Foster Care. Foster care is an entitlement program funded by the federal, state, and local governments. Children are eligible for foster care grants if they are living with a foster care provider under a court order or a voluntary agreement between the child's parent and a county welfare department. The California Department of Social Services (DSS) provides oversight for the county-administered foster care system. County welfare departments make decisions regarding the health and safety of children and have the discretion to place a child in foster care. Following the decision to remove a child from his or her home, county welfare departments have the discretion to place a child in: (1) a foster family home (basic grant of $405 to $569 monthly), (2) a foster family agency home ($1,467 to $1,730 monthly), or (3) a group home ($1,352 to $5,732 monthly).

In-Home Supportive Services. The IHSS program is currently an entitlement providing various services to eligible aged, blind, and disabled persons. The costs of this program are shared by the federal, state, and county governments. An individual is eligible for IHSS if he or she lives in his or her own home and meets specific criteria related to eligibility for the Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Program. Services are intended to serve as an alternative to out-of-home care, but eligibility for the program is not based on an individual's risk of institutionalization. Authorized services include domestic services, nonmedical personal care services, and protective supervision.

The DSS provides oversight for the IHSS program, and county welfare departments make assessments regarding client eligibility, monthly hours of service per case, and duration of services. In addition, counties provide various administrative services related to worker wages, taxes, training, and referrals.

Cash Assistance. At the time of realignment, California's cash assistance program for families with children was known as AFDC. This program, like its successor program—the CalWORKs program—provided cash assistance to families with incomes inadequate to meet their basic needs. Some families also received welfare-to-work services (such as job search, on-the-job training, and education) through the GAIN program.

Prior to realignment in both foster care and IHSS, costs were generally shared by the federal, state, and local governments, with the federal government paying approximately half of total costs. The state paid virtually all of the nonfederal costs for both programs. Although foster care placement decisions and IHSS assessments of client needs were made at the county level, counties at that time assumed little of the fiscal responsibility for these decisions. Under these sharing ratios, counties therefore had little incentive to seek the most cost-effective alternatives within these care systems.

Under realignment, the Legislature significantly increased the county share of nonfederal costs for these programs (from 5 percent to 60 percent for foster care and from 3 percent to 35 percent for IHSS). To pay for any net caseload cost increases as a result of these cost-sharing changes, the original realignment statute provided counties with a fixed amount of dollars from growth revenues.

The apparent purpose of these changes was to establish county incentives to control costs. Both the change in sharing ratios and the fixed amount of growth funds available for new cases were expected to create fiscal pressure on counties to seek out less expensive alternatives within the programs. If counties exceeded the fixed amount of funds allocated for caseload growth, they were to cover these additional costs from their own revenues.

Examples of less expensive service alternatives within the foster care system could be a shift away from group homes and toward foster family and foster family agency homes, as well as emphasizing both family reunification and adoptions as alternatives to foster care. In addition, the designers of realignment had hoped that increased collaboration and innovation with probation, mental health, and community-based service organizations would reduce foster care placements.

Legislation enacted within two years of the original realignment plan changed a key piece of the realignment funding strategy. While the original realignment statute provided a fixed pool of funds for caseload growth, Chapter 100, Statutes of 1993 (SB 463, Bergeson) provided that all net costs incurred by counties due to caseload growth would be backfilled by realignment revenues in a subsequent year. Because this statutory change effectively returned county caseload costs to their pre-realignment cost-sharing ratios, realignment's cost control incentives were negated. This statutory change relieved some fears that the original formula could have exposed the state to mandate claims for the unfunded portion of the entitlements.

We note that after the enactment of Chapter 100, counties still have a very modest incentive to control costs because of cash flow concerns. Specifically, counties must wait at least one year for realignment funds to backfill county costs for caseload cost increases. Thus, to the extent that counties face cash flow difficulties in funding their caseload costs, they would face a modest incentive to control costs.

Cost Controls Largely Not Achieved. Given the minimal incentives for counties to control costs, it is not surprising that costs per case since realignment have increased in both foster care and especially IHSS. In foster care, potential savings have not been realized since realignment's enactment and the cost per case has increased slightly after adjusting for inflation. We note that in IHSS a series of non-realignment policy changes that started in the 1990s, and that are expected to impact counties through 2005-06, have added to the total cost of IHSS services.

Prior to realignment, costs for AFDC grant payments, program administration, and welfare-to-work services (GAIN) were shared among the federal, state, and local governments. As summarized in Figure 1, realignment changed the nonfederal cost-sharing ratios for the state and county governments, with a net decrease in county costs of about $210 million in 1991-92.

In response to the 1996 federal welfare reform legislation, the Legislature replaced the AFDC program with California's own version of welfare reform—the CalWORKs program. This legislation made two changes in the state/county fiscal relationship that benefitted the counties. First, the CalWORKs legislation fixed the county share of costs for administration, employment services, and support services (such as child care) at their 1996-97 dollar levels. Thus, the state now absorbs all of the increased costs (more than $1 billion in 2000-01) for welfare-to-work services. Second, the state welfare reform legislation created a performance incentive program for the counties. Specifically, all savings attributable to program exits from employment or recipient earnings are paid to the counties as performance incentives. As of 2000-01, the Legislature has appropriated approximately $1.3 billion for payment of these incentives that must be expended on needy families. Compared to the modest changes in this area made by realignment, welfare reform has provided counties with significant financial benefits.

The realignment of health programs was largely a shift in funding sources—from the state's General Fund to realignment's revenue sources—without significant changes in fiscal incentives or program administration. A lack of data makes evaluating realignment's impact on health programs difficult to gauge, but there do appear to be opportunities for improving counties' flexibility.

Unlike some programs within the social services and mental health areas, the realignment of health programs was largely not intended to alter fiscal incentives, establish performance measures, or shift program administration to the counties. According to state and local government officials, the main purpose was to relieve the state General Fund of fiscal pressure. At the time of realignment, MISP and AB 8 services were already being administered by the counties, and realignment did not change the state's role in the administration of CMSP and LHS. Essentially then, realignment substituted fund sources—replacing state General Fund appropriations with realignment's tax increases. At the same time, realignment did make several changes in the areas of data reporting and fiscal flexibility, which we discuss below. The realigned health programs received $833 million of the original realignment allocations, which had grown to $1.3 billion in 1999-00.

Realignment Reduced Reporting Requirements. Realignment was intended to reduce the reporting requirements for the AB 8 program. Prior to realignment, counties were required to submit to the state an AB 8 Plan and Budget and an Actual Financial Data Report. The Actual Financial Data Reports showed how AB 8 funds were being allocated among public health, inpatient care, and outpatient care within an individual county and contained details of AB 8 budget appropriations, revenues, and the county's share of costs for its programs.

A county's AB 8 Plan and Budget presented detailed descriptions of the affected programs. For example, a county would report its total public health expenditures, its specific allocation to chronic disease, and which specific diseases were being tracked (such as cancer, diabetes, arthritis, and heart disease). In addition, counties would report their public health staffing levels by type of personnel (such as administrative staff, physicians, nurses, or sanitarians). Pursuant to realignment legislation, counties are no longer required to submit their AB 8 Plans and Budgets to the state. Today's level of reporting does not include the tracking of specific diseases or detailed staffing information.

Much of the previously collected data was helpful at the state level for understanding a particular county's approach to providing health services. Aggregating this data for statewide analysis, however, could only be done manually. As a result, it was difficult for DHS to use the reported data for policy purposes.

Lack of Data Restricts Statewide Evaluation. Our analysis of realignment's impact on health programs indicates that there are data gaps in the realigned health programs. Specifically, there is no state system to collect data regarding each county's (1) total expenditures for indigent care by fund source, or (2) total expenditures by fund source for each major spending category—public health, indigent inpatient care, and indigent outpatient care. The lack of this data leaves the state unable to answer fundamental questions regarding the provision of health services in each county and hampers the state's ability to devise effective health financing policies and budgets.

Realignment appears to have improved county fiscal flexibility in some areas. For example, realignment has provided additional authority to shift resources between AB 8 services and MISP services to the area of greatest need. Specifically, any growth in realignment funding that counties receive can be spent in either the AB 8 service area (public health, inpatient care, or outpatient care) or MISP (indigent care) area.

Assembly Bill 8 Historical Restrictions Remain. Realignment, however, has continued some funding restrictions within the allocations for AB 8 services. Prior to realignment, a county had the authority to use state AB 8 General Fund monies within the public health area for (1) those programs that it had selected to fund just prior to the passage of AB 8 in 1979 and (2) any new public health programs that were established subsequent to the passage of AB 8. A county could not, however, use AB 8 funds for any existing public health programs that the county had not funded in the year prior to AB 8. Realignment's preservation of this restriction limits the discretion of counties to shift realignment funds among public health programs, leverage federal funds, implement local cost-saving measures, or reflect current local preferences.

These restrictions have created difficulties for at least one county. Humboldt County officials wanted to use realignment funding for administrative costs associated with public health programs. After the county sought clarification from the state, DHS denied the county the use of realignment funds for this purpose because the county had not used certain funding prior to AB 8 for this purpose. Other counties which did spend their funding on this purpose years ago would be eligible to spend their realignment dollars in this manner.

Realignment has generally provided counties with a stable and flexible revenue source. Realignment's growth allocation formulas have not, however, created incentives for counties to control their costs. Over time, the social services account has gained a greater share of total realignment dollars, with a corresponding reduction in the shares of funding for health and mental health programs. While these formulas have somewhat reduced allocation inequities, 22 counties remain "under-equity" as defined by realignment law. Realignment's transfer provisions were used by many counties over a five- year period and provided those communities an opportunity to adjust funding allocations in order to reflect local priorities.

As discussed earlier, one of the original goals of realignment was to design a system that, through changes in fiscal incentives, would encourage counties to make more cost-effective and efficient program decisions.

In the social services discussion above, however, we highlighted how the passage of Chapter 100 in 1993 effectively restored the pre-realignment cost-sharing ratios for the realigned programs. These pre-realignment ratios generally required only minimal county contributions for new caseload expenditures and, therefore, counties have little incentive to control their caseload costs, as was the case prior to realignment.

Growth Allocation Formulas Limit Incentives to Control Costs. Furthermore, the system of revenue growth allocations provides little benefit to those counties which do reduce their caseload costs. This is because counties are not permitted to retain any realignment caseload savings. Rather, each dollar that a county saves in realignment caseload costs will be distributed among all 58 counties through the remaining growth subaccounts. Therefore, counties have little incentive to seek savings in their caseload costs. This dynamic will likely intensify in the coming years as counties decide whether to increase IHSS program expenditures (due to non-realignment policy changes)—potentially driving up caseload subaccount payments without facing significant fiscal incentives to control their costs.

The combination of the half-cent sales tax and a portion of the VLF has generally provided counties a stable, reliable, and expanding funding source for the realignment portion of the various programs. Overall annual growth rates have exceeded 5 percent during the past five years. In an economic downturn, realignment program demands would likely rise at the same time that revenue growth would slow. Currently, no mechanism exists within realignment for a funding reserve to assist counties in such a situation. Furthermore, due largely to the property tax shifts of the early 1990s, counties' general purpose revenues have generally eroded over the past decade—leaving most counties with limited access to alternative revenues in such a situation.

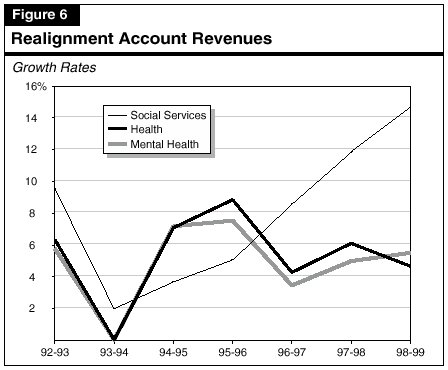

Under the initial realignment allocations, the social services account received 24 percent of total funds, mental health 34 percent, and health 42 percent. In the mid 1990s, as shown in Figure 6 , growth rates for both the mental health and health accounts exceeded the rate for the social services account. However, in more recent years, the social services account has outpaced the other accounts in growth rates—receiving about half of new revenues in 1998-99. The social services account has averaged 10 percent growth since the beginning of realignment, while the health and mental health accounts have averaged 6 percent growth. Consequently, the social services account has, over time, gained a larger share of the total realignment allocations. As shown in Figure 7, by the end of 1998-99, the social services account was receiving 27 percent of total funds, mental health 32 percent, and health 41 percent.

| Figure 7 | |||

| Changes in Account Shares of Realignment Funds | |||

| Mental Health |

Social Services |

Health | |

| 1991-92 |

34.0% |

23.7% | 42.3% |

| 1998-99 |

32.0 |

27.1 | 40.9 |

This trend reflects realignment's emphasis on fully funding entitlement programs (all but one are social services programs) as a first priority. The caseload subaccount receives the first allocation from the sales tax growth account. The allocations are based on the difference in caseload costs under realignment and the previous cost-sharing ratios. As this difference has grown in recent years, fewer dollars have been available to allocate to the mental health and health accounts from the sales tax growth funds. Although the social services account's share of revenues has increased, counties do maintain the flexibility to transfer these new dollars in the social services account to either of the other accounts. Furthermore, VLF growth dollars are allocated almost exclusively to mental health and health programs.

One of the original goals of realignment was to provide the capacity to address the historical differences in funding allocations among counties and link funding to estimates of a county's program needs. Since the original allocations were based on each county's funding levels just prior to realignment's enactment, counties' allocations generally reflected a combination of their historical spending, caseloads, and populations of 1991 or even earlier.

Beginning in 1994-95, a portion of realignment growth funds have been dedicated to the four equity subaccounts—community health, indigent health, state hospital, and mental health. A fifth equity subaccount—the special equity subaccount—has completed its payments to its designated recipients and ceased operations. Each of the four remaining equity subaccounts use the same definition of equity (varying only by which jurisdictions provide the respective services). This definition—half based on population and half based on estimated poverty population—sets a statewide average of revenue allocation for each policy area. Jurisdictions below this statewide average receive a proportionate share of the dollars allocated from the respective equity subaccount. Because all realignment allocations received in one year become part of the next year's base, "under-equity" counties continue to receive these allocations in future years as part of their base realignment funding.

In 1994-95, the first year of these equity allocations, there were 22 under-equity counties. At that time, it would have taken about

$250 million (about 11 percent of total realignment allocations in that year) to bring these counties to the statewide average. In 1998-99 (the most recent equity allocations available), this "equity shortfall" had been reduced to $219 million, but 22 counties remained under-equity. Due to overall realignment revenue growth over that time, the equity shortfall now represents less than 8 percent of total realignment allocations.

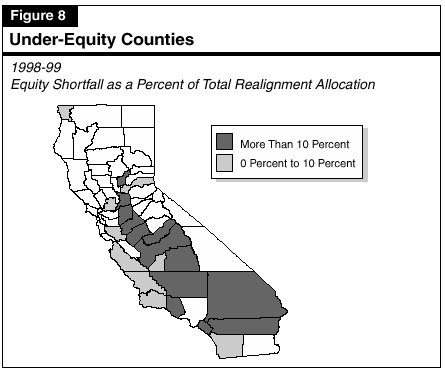

Under-Equity Counties Regionally Concentrated. Thirteen of the 22 counties' equity shortfalls represent more than 10 percent of their total realignment allocations. As shown in Figure 8, these 13 counties are concentrated in the Central Valley.

Thus, over the five-year period, variations among counties have been reduced, but this reduction is not occurring rapidly. Of the $190 million in realignment growth dollars available in 1998-99, for instance, only

$26 million (14 percent) was allocated towards equity payments. In comparison, $59 million (31 percent) was allocated to the general growth subaccount in that year—which reinforces the existing funding disparities by allocating revenues in the same proportion as counties' existing shares of revenues. Additionally, the existing formulas will not achieve equity, as defined by state law, by the time the equity subaccounts reach their statutory limit on allocations. To the extent that counties remain under-equity, they may be at a disadvantage in relation to other counties in their ability to provide services on a per-client basis.

The realignment transfer provisions allow each county the option of shifting up to 10 percent of any of their three account's annual revenues to another account (and up to 20 percent in some circumstances). These provisions were used by 22 counties during the five-year period from 1993-94 to 1997-98 (the only years for which statewide data is currently available). These counties collectively transferred a total of $193 million, or 1.6 percent of total realignment allocations during that period.

Social Services Accounts Gain From Transfers. The majority of revenue transfers have shifted dollars to social services accounts from health or mental health accounts. Over the five-year period as shown in Figure 9, counties' social services accounts had a net gain of $133 million, with nearly two-thirds of this amount coming from counties' health accounts.

| Figure 9 | ||||

| Realignment Account Transfers | ||||

| (Dollars in Millions) | ||||

| Mental Health |

Social Services |

Health | Number of Counties | |

| 1993-94 |

$3.9 |

$5.9 | -$9.8 | 10 |

| 1994-95 |

-25.9 |

80.3 | -54.4 | 13 |

| 1995-96 |

2.2 |

7.9 | -10.0 | 14 |

| 1996-97 |

-18.7 |

26.7 | -8.0 | 21 |

| 1997-98 |

-10.4 |

12.6 | -2.2 | 18 |

| Totals | -$48.9 | $133.3 | -$84.4 | 22 |

| Note: Amounts may not total due to rounding. | ||||

At the time realignment was being considered, some concern was voiced by advocates of mental health programs that funding for such programs might be significantly eroded by the transfer provisions. As shown in Figure 9, these fears have largely proven unfounded. Since 1993-94, mental health programs had a cumulative net reduction of about $49 million. In other words, about 1 percent of the funding allocated to county mental health programs during that period has been shifted to health and social services programs. Moreover, of that $49 million, about $32 million of the shift can be attributed to the actions of just one county—Los Angeles. In some years, it should be noted, mental health programs received a net gain of several millions of dollars under the transfer provisions.

Because shifts in non-realignment revenues are not reported to the state, the reports of these transfers do not necessarily reflect the entire county story regarding county program priorities. A number of counties, including Los Angeles, have taken advantage of the transfer provisions and later restored at least some of the transferred dollars using non-realignment revenues. Other counties may shift non-realignment dollars to accomplish changes in funding priorities and therefore do not report any use of realignment's transfer provisions.

At the same time, a number of counties have expressly not used the transfer provisions—citing the desire to avoid contested debates at the local level over which programs deserve additional funding. By maintaining realignment allocations as they were received from the state, counties have avoided the controversy that could result from shifting funds away from a particular program.

Transfers Allow Local Control. Nonetheless, the transfer provisions represent an important component of local control within realignment's framework. While the realignment formulas reflect statewide decisions on program funding priorities, the transfer provisions allow each county to adjust funding levels to reflect their local priorities. Furthermore, the majority of realignment dollars are allocated on historical formulas even though communities' needs and demands for services may have significantly evolved over time. The transfer provisions allow counties to appropriately modify allocations to reflect these changing needs and demands. Finally, the transfers allow counties to accommodate short-term funding shortfalls in one policy area more easily than might otherwise be possible.

In our conversations with counties, a couple of administrative issues regarding the allocations of funding from the state to counties were raised.

Unpredictable Level of Revenues. Given the complicated nature of the allocation formulas, some counties have found it difficult to develop reliable estimates of the funding they should expect from realignment on a monthly and annual basis. As a result, counties have found program planning difficult.

Delay in Caseload Payments. Since the payments from the caseload subaccount are calculated as an actual change from the prior year and made a year in arrears, payments for caseload cost increases may not be paid to a county for as many as two or more years after the time the costs were incurred. With rising caseload costs in a number of programs, some counties expressed concerns that they will face cash flow difficulties in covering the current expenses of caseload cost increases.

Our analysis indicates that, after a decade of implementation, realignment can be considered largely successful. Yet, our evaluation highlights a number of areas where improvements could be made. While maintaining its underlying structure, we recommend that the Legislature take the following actions as summarized in Figure 10, so that realignment will be better able to address the challenges and demands of the coming decade.

| Figure 10 |

| Summary of LAO Realignment Recommendations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

At several points in this analysis, we have noted that realignment preserved the system of programs and revenue allocations as existed in 1991. With each passing year, the 1991 system of funding allocations and fiscal incentives becomes more disconnected from contemporary needs and preferences. In particular, the retention of pre-realignment cost-sharing ratios in social services programs provides little incentive for counties to control costs in these programs. This, in turn, can affect the funding available for mental health and health programs. In order to promote cost-effective decision making, we believe a county's fiscal decisions in one program area should have a clear impact on its available funds in other areas. This can perhaps best be achieved by a system which provides each county its new realignment revenues in a separate distribution from other counties. As discussed above, the current system's pool of funds from which all counties compete against each other fails to provide counties an incentive to control caseload costs.

For instance, an improved growth allocation system could allocate all growth funds by a single formula. The ideal formula would provide funds to each county based on the level of demand for realigned programs in that county. For instance, the current statutory "equity" formula half based on population and half based on poverty population would be one reasonable estimate of county program demands. While maintaining their base level of funds in each of the three program accounts, counties could receive all new growth funds based half on their proportionate share of the state's population and half on their share of the state's poverty population. These funds could be distributed to each county without designating their allocation to the mental health, social services, or health accounts. County officials could then decide which realignment programs had the most pressing needs. This approach would have several advantages over the current funding allocation formulas, including:

Earlier, we noted that counties were concerned with two revenue allocation issues: (1) the lack of predictable revenue payments and (2) delays in caseload subaccount payments. The simplified growth allocation system proposed above would address both of these concerns. Since a county's share of population and poverty population does not change dramatically from year to year, a county could expect a consistent share of the total projected growth dollars. There would no longer be delayed payments based on caseload changes.

Even within the existing growth allocation system, we believe these administrative concerns could be relatively easy to address. To make the flow of allocations more predictable, the State Controller, in conjunction with the Department of Finance, could provide estimates of monthly allocations at the beginning of the year (similar to the Controller's existing annual shared revenue estimate for gas tax and base VLF revenues). Caseload payment delays and cash flow concerns could be addressed by creating a short-term loan fund. Counties could apply for loan funds based upon a reasonable estimate of future caseload payments. These loan amounts could simply be deducted from future caseload payments. Loan funds could be administered by counties in the same manner as other realignment funds and could be transferred by counties among their three accounts.

Improve Data in the Health Area. We were unable to undertake a comprehensive study of realignment's impacts in the health area as a result of limited data. In order to assist in future decision making for these programs, we recommend exploring the feasibility of collecting meaningful health data at the state level. Specifically, the state should collect annual data regarding county expenditures for public health and indigent care by fund source.

Increase County Flexibility. In our review of health programs, we noted the unnecessary restrictions placed upon counties regarding their use of former AB 8 program funds. In our view, while preserving the intent of the original AB 8 program is a reasonable approach, the spending decisions of a county more than two decades ago is an unnecessarily restrictive standard for determining appropriate spending decisions today. We recommend that the Legislature eliminate these restrictions on county flexibility and explore other ways to increase program flexibility without a loss of accountability.

Create a Reserve Subaccount. We recommend that the Legislature create a realignment reserve subaccount. The establishment of such a reserve would help mitigate the need for program reductions during periods of economic difficulty. In this regard, the Legislature could create a reserve subaccount either from (1) existing realignment revenue growth (thereby lowering new revenues available for program spending), or (2) a new revenue source, presumably a state General Fund appropriation. When the funds accumulated in the reserve subaccount reached an adequate level, further contributions could cease. If realignment revenues were to stagnate during a recession, the reserve would automatically be allocated to counties to stabilize their program funding.

Given a decade of relative success with realignment, we believe its approach to state-county relations can be a useful model for future legislative action in at least three situations, described below.

Expanding Existing Realignment Services. If the Legislature wished to increase the levels of service provided by existing realigned programs, it has several approaches available. For example, it could enact new statutes or specific state General Fund budget appropriations for particular programs. However, the Legislature may wish to instead consider adding additional resources to the existing realignment revenue streams—with counties choosing which specific programs to fund. Providing counties with additional resources within realignment would provide them with the flexibility to meet their different needs (within the general set of realignment programs). To promote accountability, a county's receipt of any additional realignment funding could be contingent upon its providing data on specific performance outcome measurements. The state could establish an Internet Web site to publish a "report card" allowing the public to compare the performance of each county with these standards.

Adding Related Services to Realignment. In order to improve flexibility for programs which provide similar services as the realignment programs, the Legislature could consider the transfer of these additional programs to the county level—along with an equivalent amount of a dedicated revenue source—and integrate them into realignment. For example, the local assistance programs of the Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs now supported through annual state General Fund appropriations could be transferred to the counties with revenues equal to their present level of state General Fund dollars (about $128 million). Likewise, in order to further realignment's original goal of creating productive fiscal incentives, counties could also receive additional fiscal responsibility for the mental health services provided under the $563 million EPSDT program. The EPSDT costs have been growing at an average annual rate of 28 percent. County costs for EPSDT are fixed at about $120 million, with the additional costs of the program borne by the state and federal governments. Thus, counties currently have no fiscal incentive to attempt to control the rapid growth in EPSDT spending—such as by implementing a rigorous utilization review process.

Applying the Concept to Non-Realignment Programs. Finally, realignment could be used as a model to "realign" state-county programs in another policy area separate from the existing realignment structure by using a dedicated revenue stream, local flexibility and authority, and accountability for new or expanded programs. In the past, we have suggested that juvenile justice, adult parole, and substance abuse might be appropriate programs for further realignment. Providing counties additional resources within a specified policy area, if implemented appropriately, could strengthen local control of program decision making, improve program coordination, reduce growth in state administrative costs, and establish clearer lines of accountability for the success of these programs.

The 1991 realignment of mental health, social services, and health programs has been largely a successful experiment in the

state-county relationship. In particular, a dedicated revenue stream for the realigned programs has helped to create an environment

of fiscal stability which improves program performance. Moreover, the flexibility granted within realignment has allowed some

counties to effectively prioritize their communities' needs among many competing demands. With some changes, realignment can

continue to provide the state an effective way to fund the various mental health, social services, and health programs.

Return to Perspectives and Issues Table of Contents,

2001-02 Budget Analysis