Legislative Analyst's OfficeAnalysis of the 2001-02 Budget Bill |

In response to federal welfare reform legislation, the Legislature created the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program, enacted by Chapter 270, Statutes of 1997 (AB 1542, Ducheny, Ashburn, Thompson, and Maddy). Like its predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children, the new program provides cash grants and welfare-to-work services to families whose incomes are not adequate to meet their basic needs. A family is eligible for the one-parent component of the program if it includes a child who is financially needy due to the death, incapacity, or continued absence of one or both parents. A family is eligible for the two-parent component if it includes a child who is financially needy due to the unemployment of one or both parents.

The budget proposes an appropriation of $5.5 billion ($2.1 billion General Fund, $143 million county funds, $15 million from the Employment Training Fund, and $3.2 billion federal funds) to the Department of Social Services (DSS) for the CalWORKs program. In total funds, this is a decrease of $126 million, or 2.3 percent. However, General Fund spending is proposed to increase by $193 million (10 percent). The increase is due to (1) replacing the current-year, one-time General Fund reduction of $154 million (due to a retroactive reduction in the maintenance-of-effort [MOE] requirement) and (2) an increase of $40 million in spending for the Department of Labor Welfare-to-Work match requirement.

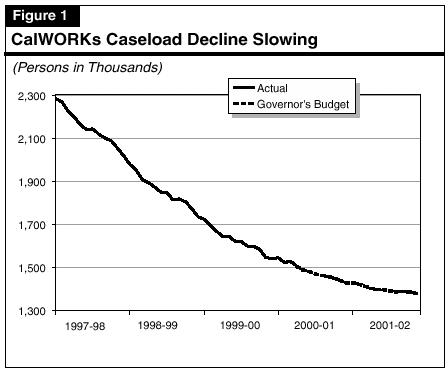

The California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids caseload has declined significantly since 1994-95. However, recent caseload data suggest a deceleration in caseload decline, and the Governor's budget projects a continued deceleration in the budget year.

The CalWORKs caseload has declined every year since 1994-95, when caseloads reached their peak. During 1999-00, the average monthly number of persons in the CalWORKs program decreased by approximately 13 percent. However, the Governor's budget projects that the caseload decline will slow to 9 percent in 2000-01. The most recent caseload data (July to September 2000) is consistent with the Governor's current-year caseload forecast. The budget projects a further deceleration in caseload decline in the budget year, when the average monthly caseload is projected to decrease by only 6 percent. Figure 1 illustrates the recent trend toward slower caseload decline.

Because the CalWORKs caseload drives program costs, we will continue to monitor caseload trends and advise the Legislature accordingly.

The General Fund cost of providing the statutory cost-of-living adjustment will be $10 million above the amount included in the budget, due to an upward revision in the California Necessities Index. These costs should be reflected in the May Revision of the budget.

Pursuant to current law, the Governor's budget proposes to provide the statutory cost-of-living adjustment (COLA), effective October 2001, at a General Fund/Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) fund cost of $132 million. The statutory COLA is based on the change in the California Necessities Index (CNI) from December 1999 to December 2000. The Governor's budget, which is prepared prior to the release of the December CNI figures, estimates that the CNI will be 4.85 percent, based on partial-year data. Our review of the actual full-year data, however, indicates that the CNI will be 5.31 percent. Based on the actual CNI, we estimate that the cost of providing the COLA will be $141 million, an increase of $10 million compared to the Governor's budget. We recommend that the budget be increased to reflect these costs.

Figure 2 shows the maximum CalWORKs grant and food stamps benefits for a family of three, effective October 2001, as displayed in the Governor's budget assuming a 4.85 percent CNI and as adjusted to reflect the actual CNI of 5.31 percent. As the figure shows, based on the actual CNI, grants for a family of three in high-cost counties will increase by $34 to a total of $679, and grants in low-cost counties will increase by $33 to a total of $647.

|

Figure 2 |

|||||

|

CalWORKs Maximum Monthly Grant and Food Stamps |

|||||

|

2000-01 and 2001-02 |

|||||

|

2001-02 |

LAO Projection |

||||

| 2000-01 | Governor's Budget a |

LAO |

Amount |

Percent |

|

|

High-cost counties |

|||||

|

CalWORKs grant |

$645 |

$676 |

$679 |

$34 |

5.3% |

|

Food Stamps c |

251 |

237 |

236 |

-15 |

-6.0 |

|

Totals |

$896 |

$913 |

$915 |

$19 |

2.1% |

|

Low-cost counties |

|||||

|

CalWORKs grant |

$614 |

$644 |

$647 |

$33 |

5.4% |

|

Food Stamps c |

265 |

252 |

250 |

-15 |

-5.7 |

|

Totals |

$879 |

$896 |

$897 |

$18 |

2.0% |

a Effective October 2001. |

|||||

b Based on California Necessities Index at 5.31 percent (revised pursuant to final data) rather than Governor's budget estimate of 4.85 percent. |

|||||

c Based on maximum food stamps allotments effective October 2000. Maximum allotments are adjusted annually each October by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. |

|||||

As a point of reference, the federal poverty guideline for 2000 (the latest reported figure) for a family of three is $1,179 per month. (We note that the federal poverty guidelines are adjusted annually for inflation.) When the grant is combined with the maximum food stamps benefit, total resources in high-cost counties will be $915 per month (78 percent of the poverty guideline). Combined maximum grant and food stamps benefits in low-cost counties will be $897 per month (76 percent of the poverty guideline).

The Governor's budget proposes to expend in 2001-02 all but $85 million of available federal block grant funds and the minimum amount of General Fund monies required by federal law for the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program. Any net augmentation to the program in excess of the proposed $85 million reserve will result in General Fund costs and any net reductions will result in an additional reserve of federal block grant funds (which would be carried over by the state).

The MOE Requirement. To receive the federal TANF block grant, states must meet a MOE requirement that state spending on assistance for needy families be at least 75 percent of the federal fiscal year (FFY) 1994 level, which is $2.7 billion for California. (The requirement increases to 80 percent if the state fails to comply with federal work participation requirements.) Although the MOE requirement is primarily met with state and county spending on CalWORKs and other programs administered by the DSS, we note that $478 million in state spending in other departments is also used to satisfy the requirement. (Below we comment on the Governor's proposal to reduce General Fund spending by $154 million in the current year due to a retroactive reduction in the MOE.)

Proposed Budget Is at MOE Floor. For 2001-02, the Governor's budget for CalWORKs is at the MOE floor. We note that the budget also includes $89 million for the purpose of providing state matching funds for the federal Welfare-to-Work block grant. These funds cannot be counted toward the MOE because they are used to match other federal funds.

The Governor's budget also proposes to spend all but $85 million of available federal TANF funds in 2001-02, including the projected carry-over of unexpended funds ($263 million) from 2000-01. The $85 million will be held in a reserve for unanticipated future program needs.

Proposition 36 Could Be New Source of MOE Funds. As noted above, California meets its MOE requirement partially through spending in other departments, which the Governor's budget assumes to be $478 million in 2001-02. As we indicate in our analysis of Proposition 36, certain expenditures of Proposition 36 funds may also be countable towards the MOE requirement. (Please see "Crosscutting Issues" in this chapter.) In that analysis, we also cite the possibility of using Proposition 36 funds to draw down additional federal funds, in which case they could not be used to satisfy the MOE requirement. To the extent that some Proposition 36 expenditures on CalWORKs-eligible families are not used to draw down new federal funds, they could be counted towards the MOE requirement.

The Governor's budget contains two proposals to reduce county performance incentives by a total of $397 million in 2000-01 and 2001-02. Specifically, the Governor proposes urgency legislation to reduce the current-year appropriation for county performance incentive funds by $153 million. In addition, the Governor `s budget proposes no funding for performance incentives in 2001-02, resulting in a savings of $244 million compared to the amount suggested by current law.

Background. The CalWORKs legislation provides that savings resulting from (1) exits due to employment, (2) increased earnings, and (3) diverting potential recipients from aid with one-time payments, may be paid to the counties as performance incentives. The 2000-01 budget trailer bill for social services—Chapter 108, Statutes of 2000 (AB 2876, Aroner)—changed the treatment of performance incentives in several important ways. Among these changes, it:

The of 2000-01 Budget Act appropriated $250 million to counties for performance incentives. Since this amount was less than the estimated prior-year obligations ($320 million), it was assumed that counties would earn no new performance incentives in the current year, consistent with the provision of Chapter 108.

Current-Year Proposal. Although earlier estimates had assumed that prior-year obligations owed to the counties would exceed $250 million, the department's current estimate of the arrearage is only $97 million. The Governor has proposed urgency legislation to reduce the current-year appropriation for performance incentives to $97 million, resulting in a TANF savings of $153 million.

Budget-Year Proposal. The department has estimated that, under the statutory formula for determining performance incentives, counties would earn approximately $244 million in 2001-02. However, the Governor's budget exercises the option, created by Chapter 108, to spend less for performance incentives than the amount suggested by the statutory formula. Specifically, the budget proposes no funding for county performance incentives, resulting in a savings of $244 million.

Expenditure of Performance Incentives. By the end of 1999-00, counties had earned approximately $1.2 billion in performance incentives, and had been paid $1.1 billion. However, as of December 2000, counties had spent only $46 million of these funds. As required by Chapter 108, nearly all the counties have submitted their performance incentive spending plans for the current year, which describe how the expenditure of these funds will be coordinated with existing services for CalWORKs recipients as well as the nonrecipient working poor. The department is still reviewing these plans.

Current-Year Proposal Raises Policy Issues. As we have indicated, the Governor proposes to reduce county performance incentive payments in the current year. We note that the Governor proposes to use the resulting TANF savings ($153 million) to replace essentially an equivalent amount of General Fund monies, which he proposes to "free-up" in 2000-01 as a result of a federal decision regarding the state's MOE. The amount appropriated for county performance incentives, as well as the treatment of the state's MOE, are policy decisions for the Legislature. Below we comment on these two current-year proposals.

The Governor proposes urgency legislation in the current year to reduce the appropriation for county performance incentives by approxiamtely $150 million. He further proposes to use the resulting Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) savings to replace a like amount of General Fund spending during 2000-01. Both of these current year proposals are significant policy decisions for the Legislature.

If the Legislature elects to reduce county performance incentives through urgency legislation, as proposed by the Governor, we recommend that the Legislature amend the legislation to prohibit the expenditure of the resulting TANF savings in the current year. This action will effectively move the decision about whether to reduce General Fund spending (resulting from the maintenance-of -effort reduction) into the budget process for 2001-02. The Legislature could then deliberate fully on its priorities with respect to General Fund support for California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids and the level of the TANF reserve for future years.

Retroactive Reduction in the MOE Requirement. As described earlier, states must meet a MOE requirement in order to receive the federal TANF block grant funds. Specifically, state spending on welfare for needy families must be at least 75 percent of the FFY 1994 level, which is $2.7 billion for California. The requirement is 80 percent if the state fails to comply with federal work participation requirements. During FFY 1997, California assumed that it would not meet the federal work participation rate, so the state budgeted sufficient General Fund monies to satisfy the higher 80 percent MOE level.

In December 1998, the federal Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) notified California that (1) it had not met the federal work participation requirements and (2) was subject to a penalty. California appealed the penalty, and in August 2000, DHHS notified the state that in fact it had met the federal work participation requirements in FFY 1997 and therefore would not be penalized. Based on this successful appeal, California's MOE requirement is retroactively reduced by about $150 million in FFY 1997. By amending a series of historical federal financial reports, California may reduce its General Fund spending for CalWORKs by the same $150 million, in the current year or future years, while remaining in compliance with the federal MOE requirement. Although DSS indicates that amending historical federal financial reports is a common practice, we note that the federal Administration for Children and Families is reviewing whether such amendments with respect to TANF and MOE spending are appropriate.

Governor's Proposal. The Governor's budget proposes to score the General Fund savings in the current year. In order to reduce General Fund spending and hold total CalWORKs program spending harmless, the Governor proposes to backfill the General Fund savings with federal TANF funds realized from his proposal to reduce county performance incentives in the current year. He proposes to achieve this reduction in performance incentives through urgency legislation in the current year. This approach fully funds the CalWORKs program in 2000-01. However, it has the effect of reducing the TANF reserve because the TANF savings resulting from the reduced county performance incentives would have otherwise gone to the reserve.

Governor's Proposals Represent Significant Policy Changes for the Current Year. The amount of spending for county performance incentives in the current year is a policy decision for the Legislature. Similarly, the amount of General Fund support for CalWORKs and the level of the TANF reserve are also policy judgments for the Legislature.

Because federal TANF funds may be carried over indefinitely, the amount of the TANF reserve is important. In future years, the TANF reserve could be used to cover potentially higher costs for (1) child care for working and former recipients and (2) higher grants pursuant to the statutory COLA. We also note that the annual TANF block grant is only authorized through the end of FFY 2002. Some observers believe that Congress may reduce the block grant after 2002 because the TANF caseload has declined significantly since the block grant was created in 1996.

We note that achieving any savings from reducing county performance incentives cannot wait until the budget year. If current law is not changed during this fiscal year, counties would establish claims to the entire $250 million appropriated. Conversely, there is no urgency with respect to achieving the General Fund savings pertaining to the retroactive FFY 1997 MOE adjustment. This could wait until the budget year, or longer. Consequently, we believe the proposal to reduce General Fund support for CalWORKs by decreasing the TANF reserve should be considered during the regular budget process for 2001-02 rather than be "rushed through" in the current year as the Governor proposes.

Analyst's Recommendation. We recommend that the Legislature take necessary action to ensure that the decision about any General Fund savings resulting from the 1997 MOE reduction is moved into the 2001-02 budget process. Adopting this approach will give the Legislature time to deliberate fully on its priorities with respect to General Fund support for CalWORKs and the level of the TANF reserve for future years.

Moving the decision about whether to reduce General Fund spending because of MOE relief into the budget year can be achieved in two different ways. First, if the Legislature rejects the urgency legislation proposal, such an action would automatically move the decision into the budget year. If, however, the Legislature approves the urgency legislation proposal, we recommend that such legislation be amended to prohibit the expenditure of the resulting TANF savings during the current year. This will effectively move the policy decision about any General Fund savings into the 2001-02 budget process.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued a program instruction clarifying that states may not draw down federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) funds prior to their immediate expenditure. California's practice of drawing down county performance incentive funds may not be consistent with this instruction. Thus the state may be required to return some TANF funds along with any interest that may have been earned. We recommend that the department provide an estimate at budget hearings on the potential interest liability and report on how it will comply with the federal instruction.

The Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), which administers the TANF program, issued a program instruction notice on January 2, 2001, regarding the draw-down of TANF funds in advance of a state's immediate need to expend the funds. The instruction indicates that TANF funds, which are subject to the Cash Management Improvement Act (CMIA), shall be advanced only when they are immediately required for program purposes. The notice further indicates that states or their grantees (including counties) that have violated the draw-down rules must return the overdrawn TANF funds along with any interest earned on the funds.

California's practice of paying counties performance incentives when they are earned, rather than when they will be used for program purposes, may not be consistent with CMIA and DHHS regulations. Accordingly, we recommend that DSS report at budget hearings on (1) the estimated cost of refunding the interest earned on TANF funds that may have been drawn down prematurely and (2) what steps it will take to comply with the federal instruction.

The California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids legislation requires that counties provide for the treatment of substance abuse or mental health problems that may prevent a recipient from becoming self-sufficient. The Governor's budget allocates $109 million to the counties for substance abuse and mental health treatment services in 2001-02, an amount virtually identical to the current-year allocation. Because counties have historically been unable to fully expend their substance abuse and mental health treatment funds, we withhold recommendation on the proposed appropriation for 2001-02 pending receipt of additional data on current-year spending.

Background. National evaluation studies, as well as information from California counties and other states, suggest that 20 percent to 30 percent of CalWORKs recipients may have a substance abuse or mental health diagnosis (or, in some cases, a "dual diagnosis"). The CalWORKs legislation requires that, to the extent funding is available, counties provide for the treatment of substance abuse or mental health problems that limit a participant's ability to make the transition from welfare to work or retain long-term employment. The legislation requires county welfare departments to collaborate with county alcohol and drug departments to coordinate assessment and treatment. The legislation also stipulates that available mental health services must include assessment, case management, and treatment services.

Each year since 1998-99, the budget has included funding for both substance abuse treatment and mental health services. This funding is counted toward the state MOE requirement.

Governor's Proposal. The Governor proposes an appropriation for 2001-02 of $55 million for substance abuse treatment and $54 million for mental health treatment, for a total of $109 million. The Governor proposes an additional $1.7 million from the CalWORKs budget for mental health and substance abuse treatment for Native American health clinics.

Prior-Year Spending Below Appropriations. In 1998-99, counties were allocated $85 million for substance abuse and mental health treatment (see Figure 3). However, counties spent only $21 million, or 25 percent of available funds. With the expectation that counties would fully implement their treatment services in 1999-00, $118 million was appropriated for substance abuse and mental health treatment in 1999-00. However, counties spent only $68 million. Specifically, counties claimed only 62 percent of their allocation for substance abuse ($38 million out of $61 million) and only 52 percent of their mental health allocation ($30 million out of $58 million).

| Figure 3 | ||||||

|

County Expenditures of CalWORKs Mental

Health and Substance Abuse Treatment Funds |

||||||

| (Dollars in Millions) | ||||||

| Mental Health |

Substance Abuse |

|||||

|

Expenditures |

Expenditures |

|||||

|

Appropriation |

Amount |

Percent |

Appropriation |

Amount |

Percent |

|

| 1998-99 | $25.0 | $11.2 | 44.9% | $59.7 | $10.0 | 16.8% |

| 1999-00 a | 57.7 | 29.8 | 51.7 | 60.5 | 37.6 | 62.1 |

| 2000-01 b | 54.1 | 4.6 | 8.6 | 54.8 | 7.0 | 12.7 |

| a Does not include supplemental claims which may accrue through March 2001. | ||||||

| b Expenditures through September 2000. | ||||||

Spending in 1999-00 varied widely among counties. In terms of the mental health funding, for example, 23 counties spent more than 90 percent of their allocation (with 11 counties spending above their allocation), while 28 spent less than 50 percent of their allocations. In fact, nine counties spent less than 10 percent of available funds. Spending on substance abuse followed a similar pattern.

Current-Year Spending Uncertain. The current-year appropriation for substance abuse and mental health services is $109 million ($55 for substance abuse and $54 for mental health). Expenditure data from the first quarter indicate that counties have spent only $12 million, or 11 percent of their current-year allocation. Whether this is indicative of a trend in the current year is uncertain. Given the large number of counties that under-spent their allocations in the prior year, it may be that they are continuing to spend below their allocations in the current year, despite technical assistance from the department and efforts to disseminate best practices information. Any unspent funds would ultimately revert and result in an increase in the TANF reserve.

On the other hand, first quarter data are typically low relative to later quarters and, therefore, do not provide a reliable estimate of full-year spending. Additionally, current-year spending is 66 percent higher than first quarter spending in the prior year. If counties continue to spend at this higher rate for the rest of the year, they would expend the entire 2000-01 allocation.

Proposition 36 Funding Adds to Uncertainty. In November, California voters approved Proposition 36, the "Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act of 2000." The measure provides $60 million (General Fund) in the current year and $120 million annually through 2005-06 to counties to pay for substance abuse treatment for specified adult offenders. The effect of Proposition 36 on CalWORKs spending for mental health and substance abuse treatment is uncertain.

On the one hand, to the extent that counties use Proposition 36 funding for eligible CalWORKs recipients, counties may use less of their CalWORKs allocation for substance abuse treatment services. On the other hand, as counties invest their Proposition 36 allocations in new program infrastructure, the additional treatment capacity may enable counties to spend their full CalWORKs substance abuse allocations. This may be the case, for example, in counties that have cited lack of capacity as a barrier to spending their full allocation.

Finally, to the extent that counties use the Proposition 36 funds to provide dual diagnosis treatment, the measure may impact counties' expenditures of their CalWORKs mental health allocations as well. (Please see "Crosscutting Issues" in this chapter for our analysis of Proposition 36.)

Withhold Recommendation on Governor's Proposal. Given the uncertainty of current-year spending for substance abuse and mental health treatment services, we withhold recommendation on the Governor's proposal to appropriate $109 million for these services in 2001-02. We will continue to monitor spending in the current year. Based on additional quarterly data, we will advise the Legislature about potential savings in the current year, as well as options for the budget year.

The Governor's budget provides only limited funding for child care for former California Work Opportunity and Responsiblity to Kids recipients who have been off aid for two years or longer.

The CalWORKs Child Care. The CalWORKs child care program is delivered in three stages. Stage 1 is administered by county welfare departments and begins when a participant enters CalWORKs. Participants transition to Stage 2, which is administered by the State Department of Education (SDE), once their situations become stable as determined by the counties. Participants can stay in Stage 2 while they remain on CalWORKs and for up to two years after they leave CalWORKs. Stage 3 refers to the broader subsidized child care system administered by SDE that serves both former CalWORKs recipients and working poor families who have never been on CalWORKs. Because there typically are waiting lists for Stage 3, in 1997 the Legislature created the Stage 3 "set-aside" in order to provide continuing child care for former CalWORKs recipients who are unable to find "regular" Stage 3 child care once they "time-out" of Stage 2.

Governor's Budget. The Governor's budget for the Stage 3 set-aside only provides funding for former CalWORKs recipients who will time-out of Stage 2 during the one month of July 2001; funding is not provided for those who will time-out during the rest of the budget year. The department has estimated that this results in a funding shortfall of about $61 million. In our analysis of the Department of Education's child care programs, we recommend using additional federal funds to backfill the shortfall. (Please see the "Education" chapter of this Analysis.) We note that if this shortfall is not addressed, it may result in former recipients returning to CalWORKs due to a lack of child care.

California's remaining match obligation for the U.S. Department of Labor Welfare-to-Work grants is $89 million. Pursuant to recently enacted federal legislation, California's deadline for expending its federal grant and the required state matching funds has been extended from July 2002 to July 2004. We recommend that proposed spending for the Welfare-to-Work match be spread equally over the next three state fiscal years to take advantage of the extension. This would result in a General Fund savings of $59 million in 2001-02. (Reduce Item 5180-102-0001 by $59 million.)

The U.S. Department of Labor provides states with Welfare-to-Work grants to serve low-income persons with specific barriers to employment. States must provide a $1 match for every $2 of Welfare-to-Work grant funds awarded. Although the Employment Development Department administers the federal grant, state matching funds are included in the DSS' budget and are appropriated to county welfare departments as part of the CalWORKs program.

California has received two Welfare-to-Work grants totaling $367 million. At the time the Governor's budget was prepared, it was assumed that the second grant ($177 million) would expire by July 2002. The budget, therefore, assumes that California would expend its remaining $89 million state match obligation in the budget year. However, pursuant to recently enacted federal legislation, California's deadline for expending the second grant has been extended to July 2004.

Consequently, we recommend that proposed spending for the Welfare-to-Work match be spread equally over the next three state fiscal years (about $29.5 million each year). Thus match spending in 2001-02 would be $29.5 million, resulting in a savings of $59.1 million. We believe this approach would not have negative program impacts, as California has had difficulty fully expending its Welfare-to-Work appropriations in prior years.

We note that if our recommendation is adopted, the department would need to increase the county allocations for employment services accordingly. This is because, as discussed below, the Welfare-to-Work matching funds are used as a partial offset to employment services allocations.

Because counties may use Welfare-to-Work funds to pay for California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids employment services, the budget reduces county funding requests by $142 million, even though in the prior year most counties' budget requests had already accounted for these funds. To avoid a potential double reduction in employment services funding, we recommend that the May Revision address this issue.

Background. Pursuant to Chapter 147, Statutes of 1997 (AB 1111, Aroner), the budget for CalWORKs employment services is based on counties' expenditure plans. (For a full discussion of the county budgeting process, please see our report, Improving CalWORKs Program Effectiveness by Changing the Employment Services Budget Process.) In addition to their employment services allocation, counties have access to other sources of funds for employment services, including the federal Department of Labor Welfare-to-Work funds and the required state matching funds.

Governor's Budget. The Governor's budget recognizes the Welfare-to-Work funds as a funding source available to counties for CalWORKs services, and therefore reduces the counties' allocation by $142 million ($79 million in federal Welfare-to-Work funds and $63 million in state matching funds). However, in 2000-01, most counties had already accounted for the Welfare-to-Work funds in developing their employment services expenditure plans. We expect counties to do the same in the budget process for 2001-02, in which case the $142 million reduction would represent a "double reduction."

Analyst's Recommendation. With respect to the Welfare-to-Work funds, we recommend that the budget process be changed as follows. First, counties would specifically identify how they plan to use both the federal Welfare-to-Work funds and the state matching funds to serve their CalWORKs clients. In making this identification, counties would note any barriers or limits on using these funds. All of this information would be incorporated into the counties' budget requests. During their review process, DSS would then determine if the proposed county use of the federal funds and state matching funds were "reasonable" and "consistent" with CalWORKs purposes. We believe this approach will result in county allocations that correctly reflect the use of available funds for employment services. Finally, we recommend that the May Revision address this issue.

The department estimates that by June 2002, nearly 60 percent of single-parent adults in the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program will reach their federal time limit. Because the CalWORKs program began 13 months after the start date of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, assistance to these families will be funded with state-only funds. If trends continue, approximately 80,000 families could face grant reductions in July 2003.

Federal Time Limit. The federal welfare reform legislation of 1996, which created the TANF block grant, established a lifetime limit on federal assistance. Specifically, states may not use TANF funds to provide assistance to families in which an individual has already received a cumulative total of 60 months of assistance (beginning December 1996). However, a state may exempt up to 20 percent of its caseload from the federal time limit for "hardship." States that use their own funds for families who have reached the federal time limit may count such expenditures towards their MOE requirement.

CalWORKs Time Limit. Generally, under CalWORKs legislation, able-bodied parents or caretaker relatives may not receive cash assistance for more than 60 months. However, their children remain eligible, in which case assistance would be provided with state-only funds, countable toward the MOE requirement. Pursuant to federal legislation, California may exempt up to 20 percent of the caseload from the time limit for hardship reasons, as determined by the county (for example, if an adult is determined to be incapable of maintaining employment).

Cases Will Be Shifted to State-Only Program. The CalWORKs adults will begin reaching their TANF time limit in December 2001. Because the CalWORKs program began in January 1998, 13 months after the federal TANF start date, adults who will reach their federal 60-month time limit in 2001-02 are eligible to receive CalWORKs for an additional 13 months. Assistance for such cases would be funded with state-only funds.

Governor's Estimates. The Governor's budget projects that by June 2002, a cumulative total of 139,000 adults, or 59 percent of all single-parent adults on the CalWORKs caseload, will have reached their federal 60-month time limit. Assuming that 20 percent of these adults will be exempted from the federal time limit, the department estimates that approximately 92,000, or 39 percent of single-parent adults, will be funded exclusively with state-only funds.

State Time Limit Approaching. If the same group of adults who will have reached their federal time limit by June 2002 remain on CalWORKs, about 80,000 families may face a grant reduction in July 2003 (this figure assumes some families will lose eligibility due to the youngest child reaching age 18).

The department has not submitted a legislatively mandated report on the Cal-Learn program due July 1, 2000. We recommend that the department report at budget hearings on the status of the report and on its findings and recommendations.

Established in 1994 as a five-year federal demonstration project, the Cal-Learn program is designed to assist pregnant and parenting teens receiving CalWORKs to graduate from high school or its equivalent. The program provides intensive case management, payments for educational expenses and supportive services such as child care and transportation, as well as bonuses and sanctions based on academic performance. Participants may earn bonuses when they achieve satisfactory grades and upon graduating, while participants who do not make satisfactory progress are subject to a $100 sanction per report card period. Chapter 902, Statutes of 1998 (AB 2772, Assembly Committee on Human Services), made Cal-Learn a permanent program supported by the General Fund and TANF.

Current law requires the department to provide the final Cal-Learn report to the Legislature by July 1, 2000. At the time this analysis was prepared, the department had not submitted the report. We recommend that the department report at budget hearings on the status of the final report and on its findings and recommendations.

By requiring recipients to enter community service after two years on aid, current law limits county flexibility in delivering services most likely to assist California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids recipients in achieving self-sufficiency. We recommend enactment of legislation to give counties the option to provide employment services for more than two years so long as participants work at least 20 hours per week. We believe this approach will enhance program effectiveness for recipients who are working because counties are in the best position to judge whether employment services or community service offers the best approach for long-term self-sufficiency.

Background. The CalWORKs program requires parents to participate in employment or welfare-to-work activities for a specified number of hours per week (single parents must work 32 hours and two-parent families must work a combined 35 hours). Recipients who are unable to find employment after an initial job search are referred for an assessment of their work skills and any employment barriers. Following assessment, the recipient signs a welfare-to-work plan, which specifies the work activities and employment services in which the recipient will participate, as well as the supportive services the recipient will be provided (including case management, child care, or personal counseling). Employment services include vocational education and training; adult basic education; and mental health, substance abuse, and domestic violence services. The primary purpose of employment services is to enable recipients to obtain employment or to advance in their current job, so that they can leave CalWORKs and become self-sufficient for the long term.

The CalWORKs legislation has two separate time limits for adult recipients. Generally, adults are limited to 60 months of grant payments and 18 to 24 months of employment services. Once the welfare-to-work plan is signed, the participant's employment services time limit begins. After a cumulative period of 18 months on aid, or, at county option, 24 months, the participant must meet his or her weekly participation mandate (32 or 35 hours) either through unsubsidized employment, community service, or a combination of the two. After the 18- or 24-month time limit, employment services may only be offered in very limited circumstances. For example, education or training may be provided if it is required for the participant's community service placement. (Months in which a recipient is exempt from participation, or is sanctioned for noncompliance, do not count toward the employment services time limit.)

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). The Department of Labor believes that under FLSA, CalWORKs recipients participating in community service are considered employees and, therefore, must be compensated at the minimum wage. This means that a recipient's monthly hours of required participation in community service may not exceed the amount determined by dividing his/her grant plus his/her food stamp benefit by the minimum wage. As a result, smaller families with relatively low monthly grants cannot be required to participate in community service for the full 32 or 35 hours required by CalWORKs. Instead, they have to meet their work requirement with other work activities, such as employment services.

Figure 4 shows the maximum number of hours per week that nonworking recipients can be required to participate in community service activities. As the figure illustrates, two- and three- person families are unable to meet their participation requirements through community service activities alone. These families are required to participate in other welfare-to-work activities, including education or job training, to meet the balance of their work requirement.

|

Figure 4 |

|||

|

Maximum Hours Per Week of Community Service |

|||

|

Region/Family Size |

Combined |

Maximum Hours |

Weekly Hours |

|

High-Cost Counties |

|||

|

2 persons |

$740 |

25 |

7 |

|

3 persons |

915 |

31 |

1 |

|

4 persons |

1,079 |

37 |

None |

|

5 persons |

1,222 |

42 |

None |

|

Low-Cost Counties |

|||

|

2 persons |

$725 |

24 |

8 |

|

3 persons |

897 |

30 |

2 |

|

4 persons |

1,058 |

36 |

None |

|

5 persons |

1,198 |

41 |

None |

a Maximum grant levels effective October 1, 2001. |

|||

b Minimum wage of $6.75 effective January 1, 2002. |

|||

c Assumes 32-hour per week participation mandate for single parents. |

|||

The Role of Community Service. We believe community service is an important component of the CalWORKs participation mandate, as it provides recipients an opportunity to gain valuable work experience prior to reaching their lifetime limit on cash assistance. This is especially true for recipients with limited or no work experience during their first 18 to 24 months on aid. However, we have identified two concerns with how current policy affects recipients who are working at least 20 hours when they reach their services time limit.

Current Policy Raises Cost-Effectiveness Concerns. Current law precludes counties from permitting working recipients to complete their participation mandate with education or training once they reach their services time limit (18 to 24 months). Thus, for example, after reaching the employment services time limit, a participant who was working for 20 hours and taking vocational education classes for the remaining 12 hours of his/her 32-hour participation mandate would instead be required to participate in community service activities for those 12 hours. Substituting a community service assignment for the employment services may be counter-productive to that participant ultimately reaching self-sufficiency. This may be true, for example, in cases where a working recipient is diverted from a successful education or training program to community service. To the extent this policy results in some CalWORKs recipients staying on assistance longer than they otherwise would, it may result in long-term costs that could be avoided.

Additionally, while not providing employment services to such recipients results in savings, there are offsetting costs involved in providing community service activities. Indeed, the costs involved in arranging transportation and child care for limited-hour community service activities may outweigh the public benefit associated with those activities.

Current Policy Raises Equity Concern. Under current law, some working and nonworking families are treated differently upon reaching their employment services time limit. After participating in community service for the maximum number of hours allowed by FLSA, certain small nonworking families can receive education or training services. Conversely, working families cannot receive such services to fulfill their participation mandate. Instead, they are required to meet their mandate with additional hours of community service. This creates a perverse incentive by "rewarding" small nonworking families with the opportunity to receive education and training in addition to their community activities, while preventing working families from receiving such services.

Analyst's Recommendation. Given the 60-month lifetime limit on cash assistance, we believe imposing a time limit on employment services may be necessary to move recipients into full-time work and, therefore, closer to self-sufficiency, as quickly as possible. As discussed above, however, the current policy raises several concerns for working recipients.

For working recipients who reach their employment services time limit, we believe that counties are in the best position to judge what mixture of employment, education or training, or community service is most likely to result in long-term self-sufficiency. Current policy, however, limits counties' flexibility to provide the services they deem most appropriate. We believe it makes more sense to give counties the option to provide employment services so long as a participant is working at least 20 hours a week. By requiring 20 hours of unsubsidized employment, this approach would be consistent with the CalWORKs policy to move recipients into full-time work as quickly as possible. This approach would also mean that participants who go to work full-time after signing their plan, and do not receive any employment services during their first 18 to 24 months on aid, would not be forfeiting their opportunity to meet the balance of their participation mandate with employment services if needed in the future.