Legislative Analyst's OfficeAnalysis of the 2001-02 Budget Bill |

Foster care is an open-ended entitlement program funded by federal, state, and local governments. Children are eligible for foster care grants if they are living with a foster care provider under a court order or a voluntary agreement between the child's parent and a county welfare department. The California Department of Social Services (DSS) provides oversight for the county-administered foster care system. County welfare departments make decisions regarding the health and safety of children and have the discretion to place a child in one of the following: (1) a foster family home (FFH), (2) a foster family agency (FFA) home, or (3) a group home.

The 2001-02 Governor's Budget proposes expenditures totaling $1.6 billion from all funds for foster care payments. This is an increase of $92 million, or 6 percent, over estimated current-year expenditures. The budget proposes $413 million from the General Fund for 2001-02, which is an increase of $25 million, or 7 percent, compared to 2000-01. Most of this increase is due to the proposed foster care cost-of-living-adjustment (COLA). The caseload in 2001-02 is estimated to be approximately 78,000, a decrease of 4 percent compared to the current year. Most of this decrease is due to child exits from foster care to the Kinship Guardianship Assistance Program, which is part of the California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids program.

Federal and state government policies generally view foster care as a temporary, not long-term, solution when children are removed from an abusive or neglectful home. Generally, the longer a child spends in foster care, the less time he or she spends in a permanent living arrangement. Our review indicates that (1) children stay longer in foster family agencies (FFAs) than other placement arrangements and (2) emotional and/or behavioral differences of FFA children do not explain the longer stay. We recommend enactment of legislation to pilot test a change in FFA rates intended to provide an incentive to accelerate FFA reunification and adoption efforts.

Federal Direction. In recent years, there has been an increased emphasis by both the state and federal governments to reduce the length of time children spend in foster care. This trend toward reducing the length of stay reflects concern about the dramatic growth in the number of children in foster care and their need for permanent, stable families. Pursuant to the Federal Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 (PL 105-89), California is required to file a petition to terminate parental rights on behalf of children who have been in foster care for 15 out of the most recent 22 months. Under this policy, the longer a child is in foster care, the less likely it is that he or she will be reunified with his or her family of origin. The goal of this policy is to ensure that children do not "drift" into foster care, but rather are moved to a permanent, stable setting. This could be reunification with the family of origin or an adoptive family.

Caseload and Costs Grow When Children Remain in Foster Care. The length of time youth spend in foster care affects government by increasing (1) the foster care caseload, (2) county workloads, and (3) total costs. From 1989 through 1999, the foster care caseload increased almost 70 percent. A portion of this growth was due to an increasing number of children entering foster care. A majority of the increase, however, was due to children remaining longer in foster care.

Increases in the foster care caseload affect local government by increasing the administrative and clinical workload of county workers. Workload increases result in costs to all levels of government. Foster care costs are shared by the federal, state, and local governments. Approximately 50 percent of costs are paid by the federal government. The remaining nonfederal costs are shared 40 percent by the state and 60 percent by the counties. The 2001-02 Governor's Budget proposes expenditures totaling $1.6 billion from all funds for foster care payments.

Range of Foster Care Placements. Following the investigation of child abuse or neglect, county welfare departments make decisions regarding the health and safety of children and have the discretion to place a child in one of three settings. These are: (1) a FFH (which costs $405 to $569 monthly plus "specialized care increments" for children needing special support services); (2) a FFA home (which costs $1,467 to $1,730 monthly); or (3) a group home (which costs $1,352 to $5,732 monthly). The FFHs must be located in the residence of the foster parent(s), provide services to no more than six children, and be licensed by DSS. The FFAs, created as an alternative to group homes, are nonprofit organizations that recruit foster parents, certify them for participation in the program, and provide training and support services. Group homes may vary from small, family-like homes to larger institutional facilities and generally serve children with greater emotional or behavioral problems who require a more restrictive environment.

In theory, the respective foster care rates were designed to reflect the needs of children. Those placed in FFHs have the fewest needs for services and support, while children placed in group homes are the most in need of intensive services and supervision. The FFAs, positioned between FFHs and group homes, were created to provide "intensive treatment" to youth who might have otherwise been placed in a group home.

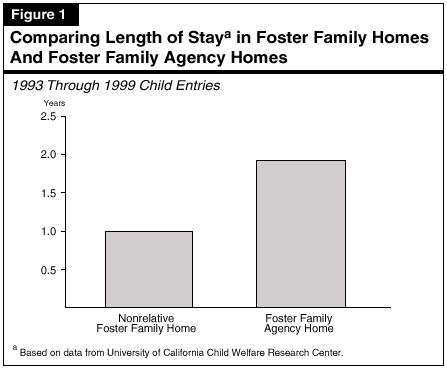

Comparing Length of Stay. Length of stay is a key performance measure of the foster care system. It shows how well the goal of permanence for children has been met. Figure 1 shows the median time in foster care for children who entered the system between 1993 and 1999, by placement type. As shown in the figure, those children for whom a FFA home was their primary placement stayed in care for almost two years, or twice as long as youth in nonrelative FFHs. As discussed above, increased time spent in foster care is generally considered undesirable, as children are less likely to be reunified with their family of origin or adopted.

Do Youth Characteristics Explain Differences in Foster Care Length of Stay? Longer stays in FFA homes might be justified if research indicated that the children in FFAs need more services prior to reunification or adoption than do children in FFHs. However, available research does not demonstrate such differences. In a report recently released by DSS, few differences between FFH and FFA youth populations were identified. County child welfare administrators surveyed in this report generally indicated that (1) behavioral issues, (2) mental health diagnoses, and (3) need for reunification services were similarly important factors in the placement of foster youth in either a FFH or FFA. We note that a legislatively mandated study is currently underway to evaluate county placement patterns, child outcomes, and oversight of FFHs and FFAs.

From 1989 through 1998, the number of children placed in FFAs increased tenfold, from 2 percent to approximately 23 percent of the total foster care population, while the proportion of FFH placements declined slightly. This trend has been accompanied by the longer length of stay for children in FFA placements. Below, we discuss how (1) the growth in FFA placements has been driven largely by a shortage in FFH slots, not children's need for FFA services; and (2) the FFA rate structure may provide an incentive to keep children in foster care longer.

What Caused the Growth in FFA Placements? Local child welfare and probation officers have indicated during our field visits that counties frequently use FFA placements for children who, according to the county's assessment, would be more appropriately placed in a FFH if such facilities were available. This finding was recently confirmed by a DSS survey of county child welfare departments, discussed above. In this survey, over 40 counties cited a lack of FFH resources as a primary reason for FFA placement.

The FFA Rates May Create Fiscal Incentive to Increase Time in Foster Care. The FFA rate is more than three times the rate paid to FFHs, as shown in Figure 2 (see next page). In theory, the higher rates paid to FFAs reflect (1) their function as alternatives to more expensive group homes and (2) the cost of services and support for children with greater emotional or behavioral issues than those children in FFHs. However, as discussed above, available research does not show such differences between children in FFHs and FFAs. We believe that the FFA rate, including about $900 per child, per month for services and administration, potentially creates a fiscal incentive for FFAs to keep children in foster care longer.

|

Figure 2 |

|||||

|

Comparison of Foster Family Home and |

|||||

|

Foster Family Agency Rate |

|||||

|

Age of |

FFH Rate |

Paid to |

Treatment and |

Total |

Difference From FFH Home Rate |

|

0 to 4 |

$405 |

$595 |

$872 |

$1,467 |

$1,062 |

|

5 to 8 |

441 |

629 |

895 |

1,524 |

1,083 |

|

9 to 11 |

471 |

657 |

913 |

1,570 |

1,099 |

|

12 to 14 |

521 |

708 |

947 |

1,655 |

1,134 |

|

15 to 18 |

569 |

753 |

977 |

1,730 |

1,161 |

As described above, children stay longer in FFAs than other placements, and these longer stays do not appear to be related to the needs of the FFA children. Given that FFAs cost more than FFHs, we discuss an approach to decreasing the length of time children spend in FFA homes by changing the FFA payment structure.

Adjusting FFA Treatment Rates. One adjustment that would provide incentives for FFAs to accelerate reunification and adoption efforts would be to gradually decrease the amount paid to FFAs for services and administration. While the rate paid to the FFA foster family would remain the same over time, the portion of the rate paid to the FFA organization for services and administration would decrease the longer a child remained in care. For example, the monthly services and administration component per child could be reduced by one-quarter (between approximately $220 and $250), incrementally, after each six-month period. Figure 3 shows an example of this incremental reduction in the treatment rate. Under this example, treatment and administrative costs would be funded at the full rate for the first six months a child is in placement. The funding would continue, at a reduced rate, for up to two years while a child remains in care. A similar step down of the treatment and administration component would be applied to all of the age-adjusted rates. (We note that many of the youth in FFAs are either reunified with their family of origin or adopted before two years has passed.) This tapering of the treatment and administration component of the rates could create an incentive system by encouraging FFAs to move children toward reunification or adoption more quickly. However, a decrease in rates could reduce the number of participating FFAs.

|

Figure 3 |

|||

|

Example of Incremental |

|||

|

Child 5 to 8 Years of Age |

|||

|

Foster Family Agency Rate |

|||

|

Time in Placement |

Paid to |

Treatment and |

Total |

|

0-6 months |

$629 |

$895 |

$1,524 |

|

7-12 months |

629 |

671 |

1,300 |

|

13-18 months |

629 |

447 |

1,076 |

|

19-24 months |

629 |

223 |

852 |

|

over 24 months |

629 |

— |

629 |

Analyst's Recommendations. We recommend enactment of legislation to conduct a three-year pilot project whereby FFA treatment rates would incrementally decrease over time. Specifically, the treatment and administration component of the rate would decrease by one-quarter every six months, reaching zero after two years. The pilot would help identify how changes in the rates impact (1) time spent in FFAs and (2) the supply of foster care slots in up to three California counties. We further recommend that DSS conduct a study to evaluate the results of the pilot. Finally, in order to encourage participation, we recommend providing modest fiscal incentives to pilot counties to offset potential associated administrative costs. Such incentives could be in the form of block grants. The grants could be based on the county share of FFA costs.

The budget proposes to convert four Foster Care Ombudsman positions from temporary to permanent, even though the department has not documented the permanent workload. We recommend retaining these positions as two-year limited term until the department can substantiate the ongoing workload.

Pursuant to Chapter 311, Statutes of 1998 (SB 933, McPherson), DSS established the Office of the Ombudsman for Foster Care to assist foster youth in resolving concerns related to their placement, care, or services. The office provides a toll-free phone service that is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. In addition, the office (1) conducts investigations, (2) resolves complaints, and (3) provides outreach to foster youth.

The 2001-02 Governor's Budget proposes the conversion of four foster care ombudsman positions from temporary to permanent. However, the proposal fails to document the level of the ongoing workload. (The original justification for these positions was based on 1995-96 caseload data from the Michigan Children's Ombudsman Office.) Accordingly, we recommend retaining the positions as limited term until the department substantiates the ongoing workload.

The cost of providing the statutory cost-of-living-adjustment to the foster family homes, foster family agencies, group homes, and related programs will be $2.4 million above the amount included in the budget due to an upward revision in the California Necessities Index. These costs should be reflected in the May Revision of the budget.

The budget proposes to provide the statutory COLA to FFHs, FFAs, group homes, and related programs effective July 1, 2001. The COLA is based on the change in the California Necessities Index (CNI) from December 1999 to December 2000. The budget, which is prepared prior to the release of the December CNI figures, estimates that the CNI will be 4.85 percent, based on partial-year data. Based on a CNI of 4.85 percent, the Governor's budget includes $69.3 million ($18.7 million General Fund) for these foster care COLAs. Our review of the final data, however, indicates that the CNI will be 5.31 percent. Based on an actual CNI of 5.31 percent, we estimate that the cost of providing the foster care COLA will be $77.3 million ($21.1 million General Fund). The administration should address this $2.4 million General Fund cost in the May Revision of the budget.