Legislative Analyst's OfficeAnalysis of the 2001-02 Budget Bill |

A number of diverse programs make up California's system of long-term care, and a variety of consumers use long-term care services. Our review of long-term care spending and caseloads shows that about half of the state's long-term care expenditures are for institutional care, while most long-term care consumers receive their care from home- and community-based services. Generally, long-term care spending is increasing, while caseloads are either remaining constant or growing at a much smaller rate than spending. In our review, we also note that California's long-term care programs comprise a fragmented service system, but that efforts are under way to improve coordination.

Assembly Bill 452 (Mazzoni). Assembly Bill 452, the Mazzoni Long-Term Care Act of 2000 (Chapter 895, Statutes of 1999), directed the Legislative Analyst's Office to provide in our 2001-02 Analysis of the Buget Bill a summary of spending on California's long-term care programs and, to the extent feasible, estimates of the population served by each program. In accordance with Chapter 895, in this section we provide an inventory of the state's long-term care services. We examine what is meant by long-term care, how much is spent on long-term care services, and how many clients are served by the various programs. We also report on recent patterns of growth in California's long-term care system. Later in this Analysis, we also provide a summary of the Governor's 2001-02 proposals to strengthen long-term care.

State's Efforts to Improve Long-Term Care. Both the Governor and the Legislature have demonstrated an interest in improving the quality and availability of long-term care services in California. The Governor's Aging With Dignity Initiative and the Legislature's subsequent budget actions in 2000 provided for enhancements in the state's long-term care services. The Legislature also passed additional long-term care measures which were subsequently approved by the Governor. For example, in addition to mandating this report, Chapter 895 established a state Long-Term Care Council through the year 2006. Comprised of directors from selected departments within the California Health and Human Services Agency (HHSA), the council is charged with the task of developing strategies for long-term care. As an initial effort to coordinate long-term care services, the council submitted state long-term care budget proposals for the 2001-02 Governor's Budget.

Efforts to improve long-term care in California have focused primarily upon expanding long-term care services that prevent or delay institutional care, maximize a person's independence, and offer consumer choice. Changes in long-term care services that have occurred have resulted not only from state policy initiatives, but also from federal incentives. In particular, the federal government provides matching funds for qualifying state programs that offer home- and community-based care as an alternative to institutional care. In addition, a recent U.S. Supreme Court decision, L.C. & E.W. vs. Olmstead, is likely to shape continued state efforts to improve long-term care. The June 1999 court ruling means that states must provide alternatives to institutions for persons with disabilities who could transition to a community setting, notwithstanding available resources and consumer preference.

Long-Term Care Encompasses a Wide Array of Services. In general, California law defines long-term care as a coordinated continuum of services that:

Long-term care services assist the individual in accomplishing routine daily activities, depending on an individual's level of need. For example, a long-term care service may provide a disabled person with assistive technology that allows that person to accomplish routine activities independently. In another case, an individual may receive assistance in the home with meal preparation; housework or shopping; or with eating, bathing, and dressing.

Generally, long-term care does not include medical care. Health insurance, including Medicare, provides for acute medical care, but generally does not cover nonmedical support services needed to perform daily routine activities. Supportive services, therefore, are made available by other providers and payers of long-term care such as Medicaid; family caregivers (spouses, adult children, and relatives); and private long-term care insurance. Some long-term care services, notably skilled nursing facilities, adult day health care, and the Program for All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) nevertheless do provide some medical care, which is incorporated into the service provider's rates for overall long-term care.

Long-Term Care Services Used by Diverse Group. Long-term care services are provided not only to the elderly (65 years and older), but also to younger persons with developmental disabilities, mental disabilities, or physical disabilities. Many elderly and disabled persons receiving long-term care are linked to the long-term care system as a result of being eligible for Medi-Cal or the Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Program (SSI/SSP).

Persons with developmental disabilities generally have a mental or physical impairment, which begins before their eighteenth birthday and is expected to continue indefinitely, and is due to mental retardation, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, autism, or a condition closely related to mental retardation. They receive their services in state-operated developmental centers or in the community through nonprofit regional centers. Individuals with mental disabilities include mentally ill persons, who generally receive care in state and county mental health programs, and persons with traumatic brain injuries. Persons with physical disabilities may receive services supported by the Department of Rehabilitation that maximize their ability to function independently, such as those offered by independent living centers.

Where Long-Term Care Is Provided. Figure 1 provides a summary of state-funded long-term care programs. Programs are listed according to the setting—institutions, the community, or the home—in which the program is provided. Major programs within each setting have been identified along with the department that administers or provides funding for the program, the total amount of spending in 2000-01, the types of services provided, and the types of clients served.

Long-term care services are provided in a variety of settings and living arrangements. Institutional care includes skilled nursing facilities and intermediate care facilities, both of which are licensed health facilities. Community-based services include nonmedical residential care, adult day health care, transportation, and nutrition. The in-home category, including such programs as In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS), provides personal care services in the home and case management aimed at coordinating a variety of services that allow a person to remain in his/her own home.

|

Figure 1 |

||||

|

Summary of Long-Term Care Programs |

||||

|

2000-01 |

||||

|

Program |

Department |

Total |

Service |

Clients |

|

Institutional Care |

||||

|

Nursing Facilities—Fee-for Service |

Medi-Cal/Health Services |

$2,634 |

Private, licensed skilled nursing facilities. |

Medi-Cal eligible elderly, disabled, or needy. |

|

Nursing Facilities/Intermediate Care Facilities—Managed Care |

Medi-Cal/Health Services |

236 |

Long-term care provided by County Organized Health Systems, usually in an institutional setting. |

Medi-Cal eligible elderly, disabled, or needy. |

|

Developmental Centers |

Developmental Services |

656 |

State institutions. |

Developmentally disabled. |

|

State Hospitals-Lanterman-Petris-Short |

Mental Health |

110 |

State institutions. |

Mental health patients. |

|

State Hospitals-Forensic |

Mental Health |

407 |

State institutions. |

Mental health patients. |

|

Intermediate Care Facilities- |

Medi-Cal/ |

326 |

Private, licensed health facilities. |

Developmentally disabled. |

|

Veterans' Homes-Nursing Facilities and Intermediate Care Facilities |

Veterans Affairs |

60 |

State institutions, with licensed skilled nursing and intermediate care facilities. |

Elderly or disabled veterans. |

|

Veterans' Homes-Residential |

Veterans Affairs |

20 |

State institutions, with residential and domiciliary care. |

Elderly or disabled veterans. |

|

Community-Based Care |

||||

|

Regional Centers/Nonresidential |

Developmental Services |

$1,120 |

Services provided to clients residing in own home or home of a relative. |

Developmentally disabled. |

|

Regional Centers/Residential |

Developmental Services |

$708 |

Services provided to clients residing in community care facilities. |

Developmentally disabled. |

|

SSI/SSP Nonmedical Out-of-Home |

Social Services |

456 |

Cash grant for residential care (generally, grants used for Residential

Care |

Elderly or disabled, as eligible according to income and assets. |

|

Adult Day Health Care |

Medi-Cal/Aging |

123 |

Licensed facilities offering health, therapeutic, and social services. |

Elderly, disabled adults. |

|

Nutrition |

Aging |

68 |

Congregate or home-delivered nutritional meals. |

Elderly. |

|

Program of All-Inclusive Care for the |

Health Services |

66 |

Full range of care, including adult day health, case management, personal care, provided on a capitated basis. |

Elderly. |

|

Supportive Services |

Aging |

36 |

Programs authorized by the Older Americans Act, including case management and transportation. |

Elderly. |

|

Conditional Release Program |

Mental Health |

17 |

Assessment, treatment, and supervision. |

Judicially committed. |

|

Independent Living Centers |

Rehabilitation |

13 |

Grants provided to centers, which provide a full range of services. |

Disabled. |

|

Caregiver Resource Centers |

Mental Health |

12 |

Nonprofit resource centers. |

Caregivers of brain-impaired adults. |

|

Ombudsman |

Aging |

6 |

State program that advocates for rights of residents in 24-hour

long-term care |

Elderly. |

|

Alzheimer's Day Care Resource Centers |

Aging |

5 |

Day care. |

Persons with Alzheimer's disease or other dementia and their caregivers. |

|

Alzheimer's Disease Research Centers |

Health Services |

4 |

Diagnostic and treatment services. |

Persons with Alzheimer's disease or other dementia. |

|

Senior Companion Program |

Aging |

$2 |

Companionship and transportation |

Elderly. |

|

Respite Care |

Aging |

1 |

Temporary or periodic services to relieve primary and unpaid caregivers. |

Elderly or disabled, and their caregivers. |

|

In-Home Care |

||||

|

In-Home Supportive Services |

Social Services |

$1,972 |

Private and public services, coordinated by the county welfare departments, to allow eligible persons to remain in their homes. |

Low income elderly, blind, or disabled. |

|

Multipurpose Senior Services Program |

Aging |

39 |

Case management program provided under a federal waiver to prevent or delay premature institutional placement. |

Medi-Cal eligible elderly certifiable for skilled nursing care. |

|

Linkages |

Aging |

9 |

Case management program to prevent or delay premature institutional placement (services provided regardless of Medi-Cal eligibility). |

Elderly or disabled. |

Multiple State Departments Provide Long-Term Care. Within California, the Departments of Aging (CDA), Health Services (DHS), Social Services (DSS), Developmental Services, Mental Health (DMH), Rehabilitation, and Veterans Affairs directly administer programs and services that provide long-term care. In some cases, for example, mentally disabled and developmentally disabled clients, the department provides funding to county-operated entities or nonprofit organizations for long-term care services.

Many of the long-term care services in California are funded by Medi-Cal—the state's Medicaid program—which is the jointly funded state-federal health insurance program for eligible low-income and needy persons. Specifically, Medi-Cal pays for nursing home beds on a fee-for-service basis for authorized individuals. Medi-Cal also funds an in-home personal care services program as a state optional benefit, which is administered by DSS as part of the IHSS program. Medi-Cal additionally funds home- and community-based services to targeted individuals—those who might otherwise require institutional care. These services are provided under federal home- and community-based services waivers which allow payment for services not otherwise authorized by Medi-Cal. For example, the Multipurpose Senior Services Program (MSSP) provides case management to frail elderly persons so that they may continue to live in their own homes.

Other long-term care programs administered by the CDA and local Area Agencies on Aging receive federal funds under the Older Americans Act. The state provides nutrition services, as well as other home- and community-based social service programs, with these federal funds.

The state's framework for delivering long-term care services largely reflects the state's central role as an administrative entity for federal funds. The federal government requires a single state agency to be responsible for federal Medicaid funds. In California, that agency is DHS, which receives all federal Medicaid funding and disburses these funds to other departments that administer the programs providing long-term care services. Notwithstanding DHS' designation as the single state agency for federal funding, the General Fund portion of Medicaid funding is channeled through DHS only in some cases. In other cases, it is allocated directly to the department administering a particular program.

Key Trends Evident in Data. Figure 2 summarizes the total spending, caseloads, and cost per case for the major long-term care services provided in the state.

|

Figure 2 |

|||||||

|

State-Funded Long-Term Care Services |

|||||||

|

2000-01 |

|||||||

|

Funding |

|||||||

|

Program |

Department a |

State |

Federal |

Local |

Total |

Caseloads b |

Cost |

|

Institutional Care |

|||||||

|

Nursing Facilities— |

Medi-Cal/DHS |

$1,308 |

$1,326 |

— |

$2,634 |

65,050 |

$40,487 |

|

Nursing Facilities/ |

Medi-Cal/DHS |

117 |

119 |

— |

236 |

8,704 |

27,130 |

|

Developmental Centers |

Medi-Cal/DDS |

417 |

240 |

— |

656 |

3,844 |

170,751 |

|

State Hospitals-LPS |

DMH |

9 |

4 |

$97 |

110 |

857 |

128,636 |

|

State Hospitals-Forensic |

DMH |

407 |

— |

— |

407 |

2,717 |

149,835 |

|

ICF-DDs |

Medi-Cal/DDS |

160 |

166 |

— |

326 |

7,075 |

46,062 |

|

Veterans' Homes-SNF&ICF |

DVA |

45 |

15 |

— |

60 |

460 |

131,087 |

|

Veterans' Homes-Residential |

DVA |

15 |

5 |

— |

20 |

965 |

20,478 |

|

Institution Totals |

$2,479 |

$1,873 |

$97 |

$4,450 |

89,672 |

$49,620 |

|

|

Community-Based Care |

|||||||

|

Regional Centers/ |

DDS |

$806 |

$314 |

— |

$1,120 |

133,092 |

$8,415 |

|

Regional Centers/Residential |

DDS |

510 |

198 |

— |

708 |

22,803 |

31,061 |

|

SSI/SSP Nonmedical |

DSS |

238 |

218 |

— |

456 |

63,850 |

7,141 |

|

Adult Day Health Care |

Medi-Cal/CDA |

60 |

63 |

— |

123 |

18,930 |

6,492 |

|

Nutrition |

CDA |

9 |

59 |

— |

68 |

224,698 |

305 |

|

Program of All-Inclusive Care |

Medi-Cal/DHS |

33 |

33 |

— |

66 |

3,711 |

17,785 |

|

Supportive Services |

CDA |

5 |

31 |

— |

36d |

908,836 |

40 |

|

Conditional Release Program |

DMH |

17 |

— |

— |

17 |

749 |

23,028 |

|

Community-Based Care |

|||||||

|

Independent Living Centers |

DR |

6 |

7 |

— |

13 |

33,736 |

$371 |

|

Caregiver Resource Centers |

DMH |

12 |

— |

— |

12 |

13,583 |

902 |

|

Ombudsman |

CDA |

4 |

2 |

— |

6 |

180,451 |

32 |

|

Alzheimer's Day Care |

CDA |

4 |

— |

— |

5 |

2,639 |

1,768 |

|

Alzheimer's Disease |

DHS |

4 |

— |

— |

4 |

2,000 |

2,000 |

|

Senior Companion Program |

CDA |

2 |

— |

— |

2 |

425 |

4,388 |

|

Respite Care |

CDA |

1 |

— |

— |

1 |

1,068 |

604 |

|

Community Totals e |

$1,710 |

$926 |

— |

$2,637 |

1,610,571 |

N/Af |

|

|

In-Home Care |

|||||||

|

IHSS |

Medi-Cal/DSS |

$746 |

$807 |

$418 |

$1,972 |

248,999 |

$7,919 |

|

MSSP |

Medi-Cal/CDA |

22 |

17 |

— |

39 |

13,847 |

2,800 |

|

Linkages |

CDA |

9 |

— |

— |

9 |

5,643 |

1,547 |

|

In-Home Totals e |

$777 |

$825 |

$418 |

$2,019 |

268,489 |

N/A f |

|

|

Grand Totals |

$4,966 |

$3,624 |

$515 |

$9,106 |

N/A f |

N/A f |

|

|

Percentage of Totals |

55% |

40% |

6% |

100%g |

N/A f |

N/A f |

|

a Department of Health Services (DHS), Department of Developmental Services (DDS), Department of Mental Health (DMH), Department of Veteran Affairs (DVA), Department of Social Services (DSS), California Department of Aging (CDA), and Department of Rehabilitation (DR). |

|||||||

b Some caseload data represent an annual estimate based on an average monthly caseload, and therefore does not represent the number of persons served on an annual basis. |

|||||||

c Includes Senior Care Action Network. |

|||||||

d In addition to total spending shown for supportive services, $14 million (General Fund) was appropriated for long-term care innovation grants in FY 2000-01. |

|||||||

e Caseload summation does not provide an unduplicated count of total users. Many individuals use more than one service. |

|||||||

f Caseload summation does not provide an unduplicated count of total users. |

|||||||

g Percentages may not total due to rounding. |

|||||||

The data demonstrate some important points regarding California's system of long-term care:

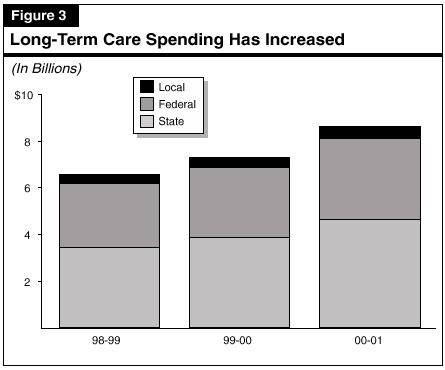

Growth in Spending Over Three Years. As Figure 3 shows, spending on state-funded long-term care services grew from nearly $7 billion in 1998-99 to $7.7 billion in 1999-00, and is estimated to reach $9.1 billion in 2000-01. During this period, the General Fund portion of these costs was $3.7 billion in 1998-99, $4.2 billion in 1999-00, and will be an estimated $5 billion in 2000-01.

An increase of $1.3 billion in General Fund spending from 1998-99 through 2000-01 may be attributed in part to the expansion of services not covered by Medi-Cal and, therefore, not eligible for federal funding support. Also, there has been a reduction in federal funding for two programs. Specifically, two developmental centers lost federal funding due to noncompliance with federal requirements, and the General Fund compensated for that loss. Efforts are under way that would allow restoration of federal funding by 2001-02.

Increases in spending occurred across all three settings for long-term care. However, the rates of increase and, therefore, the relative shares that each of these settings are of total expenditures, have changed somewhat over time. For example, the data indicate that the share of total spending for institutional care has decreased slightly from 1998-99 through 2000-01, from 51 percent to 49 percent. The share of total spending for in-home care, on the other hand, has increased slightly from 21 percent to 22 percent during the same period.

Factors Contributing to Growth. We have identified two major factors contributing to growth in long-term care spending:

Caseloads Not Main Cost Factor. Notably, caseloads are not significantly driving up costs for the largest long-term care programs. For example, growth in caseloads over fiscal years 1998-99, 1999-00, and 2000-01 has remained fairly flat for the services with the highest spending levels, specifically for nursing facilities and developmental centers. Expenditures for nursing facilities, on a fee-for-service basis, grew an average of 13 percent each year and expenditures for developmental centers grew an average of 15 percent each year, while caseloads show zero growth. Also, caseloads for regional centers for the developmentally disabled and caseloads for the IHSS program grew at significantly lower rates than the corresponding growth in expenditures for these programs. Caseloads for regional centers generally grew by 6 percent per year, while overall expenditures for this program grew by 15 percent. Likewise, caseloads for the IHSS program grew an average of 7 percent each year, while costs rose by 19 percent.

Long-Term Care Services Are Fragmented. The state's continuum of long-term care consists of multiple programs administered by multiple entities. Administration of long-term care services in California remains fragmented with no real "system" of long-term care in place. With the exception of the regional centers, which coordinate care for persons with developmental disabilities, little formal coordination of services available to eligible individuals occurs. Nevertheless, informal coordination sometimes does take place at the local level. An adult day health care center, for example, might assist an individual in accessing other services, such as IHSS and transportation services.

Current Efforts to Coordinate Services. The Long-Term Care Council, chaired by the HHSA, was recently established as an interagency working group to seek efficiencies in long-term care programs and to recommend viable options for individuals with long-term care needs. In addition, DHS has a Long-Term Care Integration Pilot Project to develop and test a seamless service delivery system at the local level.

The 2001-02 Governor's Budget proposes more than $10 million ($8 million General Fund) for various programs to expand home- and community-based long-term care services. The proposals build upon the Governor's Aging With Dignity Initiative, recently enacted legislation, and the efforts of the California Long-Term Care Council that was established last year. We raise no issues with most of the proposals at this time.

The 2001-02 Governor's Budget proposes approximately $10 million ($8 million General Fund) to establish new and expand existing home- and community-based long-term care services. The administration proposals are explained below and summarized in Figure 4.

|

Figure 4 |

|||

|

Governor's Long-Term Care Proposals |

|||

|

2001-02 |

|||

|

General |

Other |

Total |

|

|

New Programs |

|

|

|

|

Pilot Projects to Expand Community Long-Term |

$0.5 |

$0.5 |

$1.0 |

|

Assisted Living Waiver |

0.5 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

|

Nursing Home Quality of Care |

1.0 |

0.9 |

1.9 |

|

Institutions for Mental Diseases Transition |

1.0 |

— |

1.0 |

|

Elder Abuse Awareness Campaign |

2.0 |

— |

2.0 |

|

Continued Programs |

|

|

|

|

Linkages |

$1.5 |

— |

$1.5 |

|

Adult Day Health Care |

0.5 |

$0.5 |

1.0 |

|

Senior Wellness Education Campaign |

1.0 |

— |

1.0 |

|

Totals |

$8.0 |

$2.4 |

$10.4 |

Projects Move in Right Direction. Our analysis indicates that the Governor's budget proposals generally have merit and are consistent with the administration's and the Legislature's efforts to strengthen the long-term care system through the adoption last year of the Aging With Dignity Initiative and the establishment of the Long-Term Care Council.

Several of the projects also are consistent with the mandates of the Olmstead decision, which found that the unjustified institutionalization of people with disabilities constitutes discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act. The court's decision therefore compels states to review available alternatives to institutional care for individuals with disabilities. Two of the Governor's budget proposals seek to identify individuals currently receiving institutional care (in nursing facilities and in county-operated IMDs) for placement in a community setting. A third proposal would advance compliance with the Olmstead ruling by seeking to develop an assisted living Medi-Cal waiver program that also might offer an alternative to institutional care for some individuals.

At this time, we have no issues with the Governor's proposals to implement an assisted living waiver, expand the Linkages program, conduct elder abuse public awareness and senior wellness education campaigns, and expand oversight of adult day health care centers. We discuss our proposed modifications of the other budget proposals below.

We recommend that funding for the Institutions for Mental Diseases transition pilot project be reduced by $333,000 from the General Fund, with a corresponding increase in federal funds by $333,000, due to the availability of federal grant funds for such projects. We also recommend approval of the funding requested for pilot projects to expand community options for long-term care, but propose that the federal funding appropriation be increased by $833,000 because of the availability of federal grant funding for expansion of such projects. Finally, we recommend that the state Health and Human Services Agency report at the time of budget hearings on state activities to apply for these federal grants. (Reduce Item 4440-101-0001 by $333,000, increase Item 4440-101-0890 by $333,000, and increase Item 4260-001-0890 by $833,000.)

New Federal Grant Programs. The Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA), the agency that administers the federal Medicaid program, recently announced two grant programs providing collectively more than $65 million to states for projects that would allow persons with disabilities and chronic illnesses to live in the most integrated setting appropriate to their needs. Two of the long-term care projects proposed in the 2001-02 Governor's Budget appear to be eligible for these new federal grants.

Grants to Transition Disabled Persons From Institutions. The first federal grant program would assist states in the transition of disabled persons from nursing facilities to community-based settings. The HCFA plans to award up to $15 million in grants nationally by September 2001, with each individual grant ranging from $300,000 to $1 million for a period of three years.

One of the Governor's proposals, the IMDs transition pilot project, appears to be eligible for funding from the new federal grant program. Just as the federal grant program proposes, the Governor's pilot project aims at providing a transition for disabled persons from an institution to the community. The Governor's proposal for a three-year pilot also matches the proposed three-year term of the federal grants. Shifting the cost of the pilot program from the state to federal grant funds could result in a savings to the state General Fund of up to $333,000 annually for three years.

Grants for Expanding Community Options. The second federal grant program announced by HCFA would award $50 million to states over three years, with individual state grants ranging from $250,000 to $2.5 million for the project period. These so-called "real choice systems change" grants are to support state programs that generally create improvements in community living for people with disabilities.

Our analysis indicates that this second federal grant program could assist the Governor's budget proposal for pilot projects to expand community options for long-term care. Federal grant funds probably could not be used in place of the proposed General Fund appropriation during 2001-02. That is because the initial state funding would be used to develop an assessment tool to identify persons currently residing in nursing homes who could be placed in the community, not for actually testing any new programs to support successful community placement. However, we believe that these federal grant funds could be used as an extension of the pilot projects to begin expanding these community options. If a grant application were successful, the state could receive up to $833,000 during 2001-02, and again in the two subsequent years, to follow through on the Governor's pilot projects.

Analyst Recommendations. For these reasons, we recommend a $333,000 reduction from the General Fund and a corresponding increase in federal funds for the IMDs transition pilot project. We further recommend that the Legislature adopt budget bill language authorizing DMH to submit a Section 27.00 letter for additional General Fund resources if the state is unsuccessful in a federal grant application. These actions would give DMH federal spending authority if the state is awarded grant funding but would also ensure the availability of General Fund support in the event that federal funding is not provided.

We further recommend that $833,000 in additional federal spending authority be provided to DHS in the event it is successful in obtaining federal grant funding to expand the pilot projects to expand community options for long-term care. Finally, we recommend that HHSA report during budget hearings on efforts to apply for federal grants for these projects.

We withhold recommendation on $1.4 million ($500,000 General Fund) and 22.5 positions requested for a new Department of Health Services unit that would process all complaints filed against long-term care health facilities. The department has not explained why the funding and staffing for district offices now handling the intake of these complaints cannot be redirected to help support the new centralized complaint unit. We recommend that the department report at budget hearings regarding the funding and positions currently used in district offices for complaint intake activities. If the Legislature approves the department's request for the additional 22.5 positions, we recommend that 10 of the requested new permanent positions be established instead as two-year limited term positions until the ongoing workload of this new unit can be determined.

Governor's Proposal. The Governor's budget proposes to create a Centralized Complaint Intake Unit within the Licensing and Certification Division of DHS. The unit would receive and track complaints against nursing homes, and ensure proper action is taken. This proposal would facilitate a standard complaint intake procedure that is required by Chapter 451. It would add 22.5 permanent positions to staff the unit at a cost of $1.4 million ($500,000 General Fund) in 2001-02. The Governor's budget also includes $500,000 from the General Fund within the Medi-Cal budget to study the current method of reimbursing long-term care through the Medi-Cal Program.

Proposal Creates 22.5 Headquarters' Positions. The 22.5 new permanent positions include the following: 1 health facility evaluator manager, 1 health facility evaluator specialist, 2 supervisors, 2 evaluators, 12 program technicians, 2 office technicians, and 2.5 nurses. The number of positions is based upon a projected workload of processing 13,000 complaints annually.

Currently, all complaints are received and investigated by DHS Licensing and Certification district offices. Complaints are tracked in a statewide computerized system, to which headquarters has access. Under the proposed centralized complaint intake proposal, the centralized unit would receive all complaints and then assign the complaints to the appropriate district office for inspection or investigation. The district offices, therefore, would retain the primary role in investigating complaints and updating data systems for any action taken on investigated complaints.

No District Resources Redirected. The budget proposal argues that a lack of staff resources has contributed to past failures to track and to respond promptly to complaints. However, district staff did process about 13,000 oral and written complaints in 1999-00. The district staff performed job duties that will be transferred to the proposed new staff at headquarters. The Governor proposes no redirection of these district resources to fund the new centralized complaint intake unit, and has provided an insufficient explanation for keeping staffing and funding for district offices that will see a workload decrease as a result of the creation of the new centralized complaint unit. The DHS has asserted that redirection of existing staff resources would compromise other critical functions but has not demonstrated how merely shifting the location of the DHS staff involved in complaint intake activities could create a problem.

Recent Enforcement Efforts Could Result in Fewer Complaints. According to DHS data, the number of complaints received by Licensing and Certification district offices between 1997-98 and 1999-00 increased by 9 percent to about 13,000. Although the number of complaints has risen, recent enforcement efforts could result in a future decline in the number of complaints received, especially if enforcement efforts are effective. These recent enforcement efforts include increased penalties to nursing facilities for health and safety violations, increased unannounced site inspections, and the addition of Licensing and Certification district office staff to conduct investigations of complaints.

Within two years, the effect of these new enforcement efforts on workload will be known and the Legislature can determine how many permanent positions are needed to accomplish the goals required by statute. If the number of complaints drop as a result of these activities, some of the 22.5 new DHS positions proposed in the budget may no longer be needed.

Analyst Recommendation. We have no concerns about the proposed $500,000 Medi-Cal reimbursement study. We withhold recommendation on the $1.4 million requested in the budget for the new centralized complaint unit. While we agree that a higher level of service might result from the creation of the new unit, the department has not justified the level of additional new resources requested given that existing staff in district offices are currently handling this workload. For this reason, we recommend that DHS report to the Legislature regarding the funding and positions currently used for complaint intake in district offices.

If the Legislature approves the department's request for an additional 22.5 new positions, we recommend that 10 of the positions be established as two-year limited-term positions until the ongoing workload of this unit can be determined. These positions are 1 health facility evaluator specialist, 1 supervisor, 1 evaluator, 6 program technicians, and 1 office technician.