Legislative Analyst's OfficeAnalysis of the 2001-02 Budget Bill |

The Department of Conservation (DOC) is charged with the development and management of the state's land, energy, and mineral resources. The department manages programs in the areas of: geology, seismology, and mineral resources; oil, gas, and geothermal resources; agricultural and open-space land; and beverage container recycling.

The department proposes expenditures totaling $542.4 million in 2001-02, which represents a decrease of $19.6 million, or 3.5 percent, below estimated current-year expenditures. About 91 percent of the department's proposed expenditures ($492.1 million) represent costs associated with the Beverage Container Recycling Program.

The Department of Conservation is the state agency that oversees enforcement of the Surface Mining and Reclamation Act (SMARA). We find that there are several problems associated with the operation of the program. Most importantly, an unknown, potentially significant number of mining operations are in violation of SMARA.

California's surface mining industry is highly diverse in terms of mine size, minerals mined, and terrain affected by mining activities. In 1999, the state's mining industry ranked second among the states in nonfuel mineral production, with total production value of about $3 billion. About two-thirds of that amount was generated by the mining of construction-grade aggregates, such as construction sand and gravel, portland cement, and crushed stone.

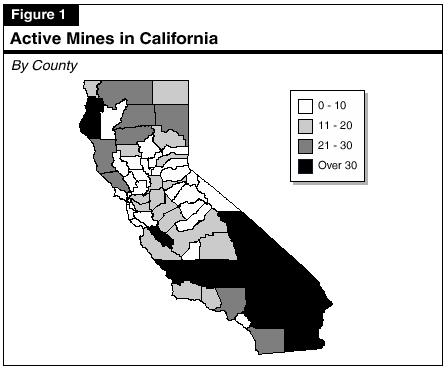

Figure 1 shows the geographical distribution of the approximately 1,000 active mines in the state. All counties except one—San Francisco—have active mines. The counties with the largest number of active mines are San Bernardino, Inyo, Riverside, Humboldt, Imperial, and Kern. For some counties, such as Trinity and Humboldt, mining is a large portion of the local economy. In other counties, such as San Bernardino and Kern, mining is of less economic importance due to a more diverse economic base. The types of materials mined throughout the state vary greatly. More than half of the state's active mines are sand and gravel mines. Stone and rock mines account for another 10 percent.

In the following sections, we discuss the requirements of the Surface Mining and Reclamation Act (SMARA), evaluate how DOC and local agencies implement and enforce SMARA, and make recommendations to improve the enforcement and oversight of SMARA.

Different levels of government have established a variety of laws and regulations to minimize environmental and other risks posed by surface mining.

Although mining is an important sector of California's economy, it poses distinct environmental and public safety risks. Depending on the type of mineral mined and the process used, mining can have an adverse effect on water and air quality, wildlife habitat, wetlands , soils, ambient noise levels, and other aspects of the environment.

A variety of laws and regulations attempt to ensure that mining is conducted in a way that does not unduly harm the state's environment, public safety, or quality of life. Local ordinances address land use issues such as siting and hours of operation. State laws such as the California Environmental Quality Act require that adverse environmental impacts be mitigated, while regional agencies such as regional water boards and air quality management districts regulate water and airborne emissions coming from mines.

In addition, SMARA, enacted in 1975, imposes various requirements specifically related to the operation of mines. More importantly, SMARA establishes requirements for the ultimate disposition of mining sites once mining has ceased—that is, the reclamation of mined lands. In general, SMARA seeks to ensure that mines are operated in a way that permits the land to be effectively reclaimed at the end of the mine's useful life.

Central to SMARA is a split in enforcement responsibility between the state and local governments. In general, "lead agencies" (primarily county governments) approve mining permits and conduct annual reviews and inspections, while the state oversees the lead agencies to ensure that they carry out their duties and serves as an arbiter of disputes over lead agency actions.

The Surface Mining and Reclamation Act requires that a variety of activities be performed by the state, local lead agencies, and mine operators.

Three general types of activities are to be performed under SMARA: (1) the classification and designation of lands with mineral resources; (2) the development of mining-related documents (mining ordinances, reclamation plans, and financial assurances); and (3) the monitoring of mining operations through inspections and reports.

Classification and Designation of Lands. The State Geologist, appointed by the Director of DOC, is responsible for "classifying" land based on the extent and importance of its mineral deposits. This mineral classification is provided to the affected local lead agencies that oversee mining operations (generally counties) to be incorporated into their local general plans. The State Mining and Geology Board (SMGB) also uses the mineral classification information to "designate" lands throughout California that have "regional significance" or "statewide significance" in meeting projected future demands for minerals. Lead agencies with jurisdiction over lands designated as significant must adopt land use policies that "emphasize the conservation and development of identified mineral deposits." For example, a local government might prohibit development in areas that would prevent the mining of major mineral deposits.

To date, the State Geologist has classified approximately 10 percent of the land in the state, focusing on those areas most subject to projected development. (Upon request and as resources permit, the State Geologist will classify additional lands, giving priority to regions facing development pressures.) The SMGB has designated approximately one-fourth of all classified lands as being of regional or statewide significance.

Ordinances, Reclamation Plans, and Financial Assurances. Under SMARA, lead agencies must have adopted a surface mining ordinance, approved by SMGB, before they are able to approve mining operations in their jurisdictions. The ordinance must specify requirements for mine operation permits, as well as requirements for reclamation plans and maintenance of financial assurances.

Mine operators must possess a surface mining permit and an approved reclamation plan to operate a mine. In general, a reclamation plan describes the nature of the surface mining operation and explains how the land will be restored after mining ceases, noting such concerns as controlling groundwater contamination, rehabilitating habitat, and stabilizing geological features.

Operators must also provide financial assurances to cover the costs the local government or the state would incur if it has to reclaim the land in the event the operator fails to do so. A financial assurance can take the form of a surety bond, a letter of credit, a trust fund, or another form approved by SMGB. In the event the operator abandons the site or is unable to complete reclamation, the lead agency or DOC's Office of Mine Reclamation (OMR) can seek forfeiture of the financial assurance in order to fund the reclamation.

Reclamation plans and financial assurances must be approved by lead agencies. When the lead agency believes that a submitted reclamation plan or financial assurance meets SMGB requirements, it forwards the document to OMR. Current law allows OMR to review and recommend revisions to the plan or financial assurance in order to ensure compliance with SMARA. The lead agency must consider OMR's comments, and may require that a mine operator amend its reclamation plan or financial assurance to address OMR's concerns. Once the lead agency approves a reclamation plan or financial assurance, it files the approved document with OMR. Reclamation plans and financial assurances must be adjusted annually to reflect expansion of operations or progress made toward reclamation. Amended plans and assurances are also subject to review by the lead agency, review by OMR, and approval by the lead agency (after considering any suggestions made by OMR).

Inspections and Reporting. The SMARA also requires lead agencies annually to inspect all mines in their jurisdictions. These inspections in part are to determine whether mine operators are operating in accordance with the approved reclamation plan and mining permit. Mine operators are responsible for the cost of inspection.

In addition, mine operators are required to report annually to the lead agency and OMR. The report must describe the mining operation during the previous calendar year, and must include specified information pertaining to ownership, production, land disturbance, and documentation of financial assurances, reclamation plans, and inspections. Operators must also pay to the state an annual fee, as determined by SMGB, based on the size and type of mining operations.

Various provisions of the Surface Mining and Reclamation Act (SMARA) fail to be enforced at an unknown, potentially significant number of mines. Hundreds of mines are in violation of procedural requirements. In addition, some mines do not meet SMARA's substantive provisions, but the number is unknown because state oversight in this area has been limited.

In the course of our review, we conducted site visits of active mining operations, met with representatives of the mining industry and local governments, participated in discussions with DOC and legislative staff, and reviewed various reports, including DOC's October 2000 report required by the Supplemental Report of the 2000 Budget Act. We find that various provisions of SMARA fail to be enforced at a potentially significant number of mine sites.

Violations can be classified as "procedural" or "substantive." By a "procedural" violation we mean a failure to complete some mandated action, such as a mine operating without an approved reclamation plan or a lead agency failing to conduct an annual mine inspection. By contrast, we define a "substantive" violation as an instance where a mandated action has been taken—such as submitting a reclamation plan—but it does not conform to the standards established in statute and regulations.

As regards procedural violations, DOC reports that well over 100 mines lack approved reclamation plans and financial assurances. In addition, lead agencies have failed to conduct required annual mine inspections for more than 200 mines. This is a preliminary estimate that may increase upon further review by DOC.

The complete number of substantive violations is unknown. This is because DOC has seldom determined whether reclamation plans and financial assurances substantively comply with SMARA. Anecdotal evidence suggests that a portion of these documents in fact do not meet the substantive requirements of SMARA. In addition, the failure of lead agencies to conduct annual inspections for some mines prevents the Legislature from knowing whether those mines are in fact operating in compliance with their reclamation plans.

The department lacks current, complete, and reliable data on mine compliance. We recommend the enactment of legislation that requires an annual report from the department in order to monitor its efforts to improve its data collection activities.

The DOC has not been able to provide reliable information on the status of mine compliance with SMARA. This became an issue during the 2000-01 budget hearings as the department cited high levels of noncompliance as justification for its budget augmentation request. When asked to elaborate, the department asserted that it did not have reliable data to provide a precise number of mines which were in compliance with SMARA.

Partly as a response to this uncertainty about compliance levels, the Legislature included in the Supplemental Report of the 2000 Budget Act a requirement that OMR identify mines that lacked valid reclamation plans, financial assurances, current annual reports, or recent inspections. The findings of that report, dated October 2000, are summarized in Figure 2. However, as emphasized in the report, OMR's data remains subject to serious limitations. These limitations generally fall into two categories: (1) incomplete data and (2) insufficient document review.

Incomplete Data. The incompleteness of OMR's data stems from several causes. For example, OMR asserts that a portion of its mine files lack certain documents, such as approved reclamation plans and financial assurances. In such cases, DOC cannot determine whether the missing document was never approved, or whether it was approved but simply not delivered to DOC by the lead agency. In preparing the October report, DOC attempted to clarify these kinds of questions by reviewing its mine files and requesting missing documents from lead agencies. However, in order to meet the report deadline, DOC staff reviewed fewer than half of its mine files. It is possible that review of the remaining files, which the department intends to complete in the future, will uncover additional violations.

|

Figure 2 |

|

|

Number of Mines Violating |

|

|

October 2000 Report |

|

|

Types of Violations |

Number of Mines |

|

Lacking approved financial assurance |

|

|

52 |

|

70 |

|

Lacking approved reclamation plan |

|

|

39 |

|

40 |

|

Active mines lacking annual report |

20 |

|

Mines lacking required inspection since 12/31/98 |

224 |

In addition, the incompleteness of DOC's data in part owes to haphazard data management in the department. The department asserts that management of OMR's database, including data entry and modification, has not been a priority in the past. As a result, the database is subject to missing and inaccurate information.

Insufficient Document Review. Another data limitation is the insufficient review of documents. For example, while OMR reviews most reclamation plans and amendments submitted by lead agencies, it generally does not attempt to determine whether the recommendations it makes in response to those submittals are in fact incorporated into the final, adopted versions of those plans. Further, OMR performs no review at all on most of the financial assurances that it receives. The department asserts that it limits these reviews because it lacks staff to review all documents.

The DOC Needs Incentive to Maintain Completeness, Accuracy of Data. In our opinion, DOC needs increased incentive to keep better records on statewide mine compliance with SMARA. We believe the Supplemental Report of the 2000 Budget Act requirement motivated the department to confront some of its data problems for preparation of the October 2000 SMARA report. The supplemental report requires additional SMARA reports on January 1, 2001 and quarterly thereafter, but it is unclear whether this requirement would extend beyond the 2000-01 fiscal year.

In order to ensure that it continues to maintain current and accurate data on mine compliance with SMARA, we recommend the enactment of legislation requiring DOC to report to the Legislature at least annually on mine compliance with SMARA. This report should include, at a minimum:

We recommend the reporting requirement be allowed to sunset after four years if the Legislature does not decide to extend the requirement before then.

It is unclear whether the department's review of financial assurances and reclamation plans results in increased compliance with the Surface Mining and Reclamation Act. We believe that review activities should be more directly tied to improving compliance with the act. We recommend that the department be required to provide at budget hearings a detailed plan for monitoring the adequacy of submitted reclamation plans and financial assurances. Depending on the department's response to this request, the Legislature may wish to provide further direction on how enforcement resources are to be allocated.

Under SMARA, lead agencies perform the initial review of financial assurances and reclamation plans to ensure they comply with SMARA. The DOC's role is to make certain that the documents ultimately approved by the lead agencies do in fact meet SMARA regulations. In fulfilling this role, DOC has discretionary authority to evaluate reclamation plans and financial assurances submitted by lead agencies. We believe that DOC should not exercise this discretionary authority simply to duplicate the review activity of lead agencies. Rather, DOC's activity should help to ensure that lead agencies are performing their role effectively.

One important way to help lead agencies effectively perform their SMARA duties is through the provision of technical assistance and workshops for local officials. The department currently provides such assistance to a very limited extent. We believe that such activities are valuable insofar as they help local agencies to understand SMARA requirements and to review financial assurances and reclamation plans more effectively.

The other way DOC can help to promote local compliance with SMARA is through its monitoring of lead agency-certified financial assurances and reclamation plans. In general, DOC focuses its review activity on reclamation plans, not financial assurances.

The DOC Reviews Reclamation Plans. According to DOC, OMR reviews most reclamation plans and amendments submitted to the office. Reviews often include a visit to the mine site by a geologist and a revegetation specialist. In 1999, OMR reviewed 166 reclamation plans and reclamation plan amendments, including interim management plans. In carrying out these reviews, OMR conducted 61 site visits.

The OMR does not know how many of the reclamation plans and amendments it receives comply with SMARA requirements. The OMR sometimes uses the number of comments it provides in review letters as a rough gauge of compliance, but we believe this rule of thumb cannot estimate actual, substantive compliance with any precision.

The SMARA does not require that a lead agency adopt any of OMR's recommended changes to reclamation plans and financial assurances. The lead agency is only required to "respond to" the comments, with an explanation of how it disposed of the issues raised by DOC, including reasons for rejecting any comments and suggestions. Since OMR typically does not go on to determine whether its comments were addressed in the final, adopted reclamation plans, OMR does not know the percentage of adopted plans that comply with SMARA.

The DOC Does Not Review Most Financial Assurances. Currently, OMR does not review the majority of submitted financial assurances. According to DOC, this is a policy decision meant to direct limited resources to reclamation plan review, which the department views as the higher-priority task. However, the office does review a small number of financial assurances from operators and lead agencies that it believes historically to be deficient in carrying out their SMARA responsibilities. When it does review a financial assurance, OMR verifies that the form of the assurance meets state law, and ensures that the amount would enable the lead agency to complete reclamation if the mine operator is unable to do so.

In its documentation supporting a proposed SMARA enforcement position in the 2000-01 budget, the department asserted that it has "performed few reviews of cost estimates" for financial assurances. Although the new position was included in the adopted budget, DOC has not filled the position as of January 2001.

Reviews Should Promote Compliance. We believe DOC should perform reviews in a way that ensures that lead agency activity is periodically checked for accuracy and compliance. It may not be necessary to review all submitted documents; such reviews could be performed on a representative sample of documents received by DOC. However, we believe it is important that both financial assurances and reclamation plans are checked.

We recommend that the Legislature direct the department to provide at budget hearings a detailed plan for monitoring the adequacy of submitted reclamation plans and financial assurances. The plan should

(1) estimate the number of reclamation plans and financial assurances the department expects to receive during the 2001-02 fiscal year;

(2) estimate the number of reclamation plans and financial assurances that, in its judgment, the department should review during the 2001-02 fiscal year in order to provide an appropriate level of oversight;

(3) explain the criteria that will be used to select plans and assurances for review;

(4) indicate the number and type of staff that will be required to perform these activities; and

(5) indicate whether the department currently has adequate resources to implement the plan and, if not, how the department proposes to secure adequate resources.

While statute clearly authorizes the Department of Conservation to review reclamation plans and financial assurances for compliance with the Surface Mining and Reclamation Act (SMARA), the department's recommendations that arise from those reviews are often not adopted by lead agencies. We recommend that legislation be enacted authorizing the department to revoke a lead-agency approved reclamation plan or financial assurance that it deems to not substantively comply with SMARA.

When DOC reviews reclamation plans and financial assurances submitted by lead agencies, it sends the lead agency a letter with any recommendations for changes. Statute requires lead agencies to review those recommendations and to provide DOC with a written response to its comments. It also requires the lead agency to provide DOC with a copy of the assurances and plans when they are approved.

In most cases, the department does not determine whether its recommendations were in fact adopted. This is for two reasons. First, lead agencies often neglect to submit written responses to DOC's recommendations. Without those letters, determining if and how DOC's comments were addressed requires labor-intensive review of adopted documents. Second, and more importantly, DOC argues that the question of whether its recommendations were addressed is largely an academic point, since the department cannot require adoption of its recommendations. Even if DOC believes that a reclamation plan fails to substantively comply with SMARA regulations, the approval of that plan is granted by the lead agency and not DOC.

Because DOC is ultimately responsible for overseeing SMARA, and since the state has an interest in ensuring that SMARA is enforced fairly and evenly for all the mines of the state, we believe that DOC should have the ability to take action when a SMARA document is clearly deficient. Therefore, we recommend enactment of legislation authorizing the department to revoke a lead agency's approval of a reclamation plan or financial assurance that the department deems to substantively fail to comply with SMARA. This would provide both an incentive to lead agencies to respond to DOC's recommendations and a tool for DOC to respond directly to certain SMARA violations. We emphasize that DOC should not be responsible for developing or approving a new reclamation plan or financial assurance; rather, it should simply be authorized to reject such documents that do not comply with state law.

Hundreds of mines are not inspected by lead agencies. We recommend the enactment of legislation that authorizes the State Mining and Geology Board to conduct required mine inspections where lead agencies fail to do so, and which requires that lead agencies pay the cost of such inspections.

Lead agencies often do not conduct annual inspections of mines under their jurisdictions, despite statutory requirements that they do so. The OMR's October

2000 report finds that 224 mines, or about 15 percent of those required to be inspected, had not been inspected since

December 31, 1998. The actual number may be higher once DOC completes its review of additional mine files. Lead agencies frequently cite lack of staff and

financial resources as the reasons for their failure to conduct annual inspections. However, SMARA requires that the cost of inspections be borne solely by the

mine operator. Thus, the lead agency's costs should be covered by fees paid by mine operations.

The DOC's work plan for addressing SMARA compliance problems (included as part of its October SMARA report) makes no mention of how the department might address lead agencies' failure to conduct annual inspections. Neither has SMGB taken action on this issue. Yet the performance of regular mine inspections is critical for ensuring that mine operations in fact are abiding by their approved reclamation plans.

We believe that the state should ensure that annual inspections are performed. We therefore recommend the enactment of legislation authorizing SMGB to perform inspections of mines when the lead agency fails to do so. The SMGB, like the lead agencies themselves, should be authorized to hire a qualified consultant to do this work. The SMGB should also have clear authority to gain access to mine sites to perform inspections. We further recommend that the responsible lead agency, rather than the mine operator, be required to pay the cost of inspections conducted by SMGB. This would provide an incentive for lead agencies to conduct required inspections in the first place, rather than intentionally defer this responsibility to the state.

Funding for the department's Surface Mining and Reclamation Act activities is subject to statutory caps. We recommend that (1) these caps be eliminated and (2) funding matched to workload needs be appropriated from the General Fund.

State administration of SMARA is funded from two sources: The Surface Mining and Reclamation Account (which receives a portion of federal payments from mining activities on federal lands) and the Mine Reclamation Account (which receives the annual reporting fees from mine operators). Statute limits the SMARA Account to $2 million annually (or less, under certain conditions), with the remaining federal payments going to the General Fund. The Mine Reclamation Account is currently limited to $1.4 million annually ($1 million in 1991, subsequently adjusted for inflation per statute). The fees imposed on individual mine operators are also limited, depending on the size of the operation, to the range of $50 to $2,000.

We believe caps such as these unnecessarily restrict the Legislature's review of the program's budget. Given the expansion of mining operations over time, the increasing complexity of reclamation issues, and the enforcement concerns identified in DOC's October 2000 report, additional resources for SMARA enforcement may be justified. However, the administration indicated at last year's budget hearings that further staffing augmentations beyond the one new position could not be funded from currently available resources.

Therefore, we recommend that the Legislature remove these statutory caps for both accounts. Moreover, since the current fee schedule is already assessing most mines at the maximum amount permitted by statute, we believe that the statutory limits on fees should be adjusted for inflation.

As regards SMARA Account, we recommend that the Legislature abolish the account and deposit federal mining payments directly into the General Fund. Money could then be appropriated from the General Fund as warranted by SMARA workload. We believe the Mine Reclamation Account should be retained since it allows mining fees to be directed exclusively to SMARA enforcement.

The department has spent $1.8 million over the past four years to map the sites of abandoned mines in the state. The budget proposes $399,000 to continue this effort in the budget year. However, the department does not propose to take any action to remediate the abandoned mines it has identified. Because there is limited value in continuing to map abandoned mines without addressing identified hazards, we recommend that funding for abandoned mine mapping be deleted. Any restoration of that funding should be made as part of an abandoned mine reclamation program. (Reduce Item 3480-001-0001 by $399,000.)

Tens of thousands of abandoned mines pose physical and environmental hazards in the state. Many of these mines date back to the 1800s, and their locations and last owners are frequently unknown.

In its 1997-98 budget proposal, the department requested funds to begin locating, mapping, and evaluating the state's abandoned mines. The department also indicated that, at the end of three years, it would produce a report that (1) detailed the magnitude, scope, and location of the hazards posed by the state's abandoned mines and (2) recommended future actions to address these problems. (Please see our Analysis of the 2000-01 Budget Bill, pages B-80 and B-81.) Since 1997-98, DOC has expended $1.8 million from various state funds to map abandoned mines.

Report Estimates That State Has 39,000 Abandoned Mines. The department's report, released in July 2000, estimates that the state has 39,000 abandoned mines. As summarized in Figure 3, the large majority of these mines pose physical safety hazards, environmental hazards (such as mercury leaching into groundwater), or both. The report also presents a number of options that the state could take in response to these findings, including the remediation of physical and environmental hazards and the enactment of legislation to provide funding for such remediation.

|

Figure 3 |

|

Department of Conservation |

|

Key Findings |

|

|

|

|

Options for Addressing Abandoned Minesa |

|

|

|

|

|

a Only a portion of the 20 options presented in the report are identified here. They represent the wide scope of options. |

New Legislation Authorizes Mine Remediation. In budget hearings last year, the Legislature expressed its concern that the department's efforts concerning abandoned mines should not focus solely on identifying abandoned mines, but rather should also include efforts to remediate those mines. The department responded that it was unclear whether existing statute permitted DOC to conduct mine remediation activities. Specifically, the department noted that Chapter 1094, Statutes of 1993 (AB 904, Sher) authorized such a program and an Abandoned Mine Reclamation and Minerals Fund (AMRMF), but made these provisions contingent on the enactment of anticipated federal legislation. Because federal legislation was never enacted, the relevant provisions of Chapter 1094 had not become operative.

To respond to this problem, the Legislature enacted Chapter 713 (SB 666, Sher) in September 2000. This legislation, among other things, removes the provision concerning enactment of federal legislation. As a result, Chapter 713 directly authorizes DOC to create an abandoned mine reclamation program when funds are appropriated for that purpose. The legislation also broadened potential funding sources for AMRMF, from which an abandoned mine reclamation program would be funded. To date, no money has been appropriated to that fund.

Proposed Budget Contains No Provision for Abandoned Mine Reclamation. Notwithstanding Chapter 713, as well as the department's acknowledgment in its abandoned mine report of the need to remediate abandoned mine hazards, the 2001-02 budget contains no proposal for the department to begin mine remediation activities. The budget also does not propose any money to be appropriated to AMRMF for mine remediation. The budget, however, proposes to continue DOC's abandoned mine mapping and requests $399,000 in General Fund and special fund monies to do so.

Continuation of Mapping Program of Limited Value Without Efforts to Address Identified Hazards. We see little value in continuing the mapping of abandoned mines unless the information is utilized in some meaningful effort to address the hazards posed by those mines. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature delete the $399,000 requested for the mapping program.

Initiation of Remediation Program Could Warrant Further Mapping Efforts. If the Legislature wishes that DOC begin an abandoned mine remediation program in 2001-02, it should provide funds to AMRMF and in turn appropriate funds for mine remediation from AMRMF. With an active remediation program in place, further mapping of abandoned mines might be warranted. If the Legislature wishes to fund further mapping, we would recommend that funding be provided from AMRMF as part of the remediation program.

The department's budget includes $845,000 to replace 32 department vehicles. However, the department now indicates that it only intends to purchase seven vehicles in the budget year, at an estimated total cost of $208,000. Accordingly, we recommend that the department's budget be reduced by $636,000. (Reduce Item 3480-001-0001 by $636,000.)

The budget proposes $845,000 for the purchase of 32 replacement vehicles. Most of these would be four wheel drive utility vehicles.

In the course of our review, however, the department indicated that it actually intends to purchase only seven vehicles in the budget year. Based on data provided by the department, we estimate that the seven vehicles would cost $208,000.

Based on information provided by the department, we estimate that the department is overbudgeted for the vehicle purchases by $636,000. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature reduce the department's budget by $636,000.