February 15, 2013

Governor's Criminal Justice Proposals

Criminal Justice Spending Basically Flat. The proposed total level of spending on criminal justice programs is $13.2 billion in 2013–14. This is an increase of about 2 percent over estimated current–year expenditures. The Governor’s budget includes General Fund support for criminal justice programs of $10.1 billion in 2013–14, an increase of about 4 percent over the current year. Under the proposed budget, General Fund support for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) is basically flat in 2013–14, and total support for the judicial branch budget is proposed to increase by 7 percent in 2013–14.

Relatively Few Major Criminal Justice Proposals. Compared to prior years, the Governor’s 2013–14 budget includes few major proposals. The budget, however, includes a one–time $200 million transfer from a court construction fund to the General Fund, as well as a proposal to fund the ongoing service payments for the new Long Beach Courthouse from the same construction fund. In considering these proposals, the Legislature will want to weigh the General Fund benefits of these proposals against the likely delays in court construction projects that could result. The budget for CDCR includes a significant policy proposal to modify an existing grant program designed to bolster county probation programs and incentivize reductions in the number of probation failures that go to prison. In particular, the proposed modifications are meant to account for changes in who is eligible to be sentenced to state prison after recent policy changes. While the administration is right to propose changes to the existing formula, we find that the methodology proposed has serious flaws that could undermine the effectiveness of the program.

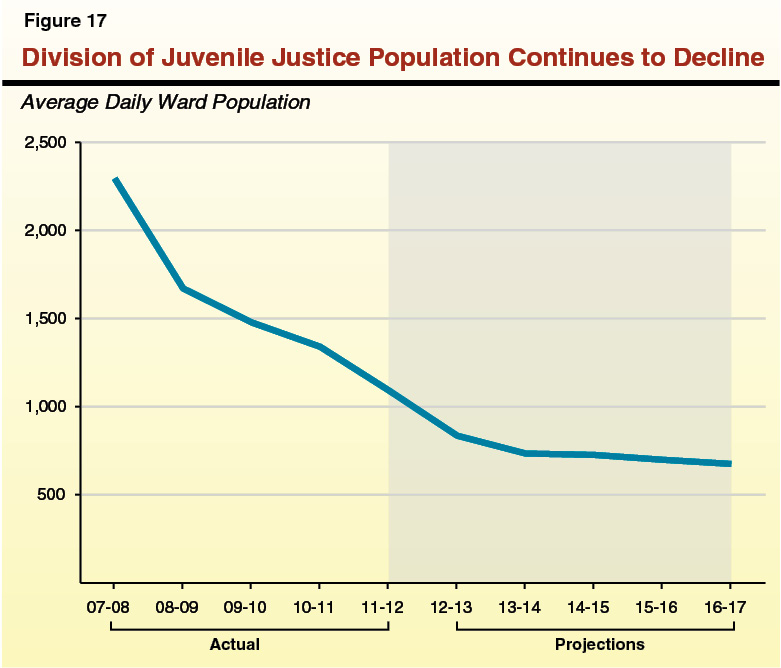

Potential Reductions Identified. In reviewing the Governor’s budget, we identify several proposals that we believe could be reduced on a workload or policy basis. For example, we find that the caseload request for the Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) is likely overestimated by several million dollars because actual population trends are much lower than budgeted. We also recommend reverting an existing appropriation set aside for future CDCR infrastructure projects. This would save the state $10 million in the budget year and better preserve the Legislature’s oversight authority. We also find that the state could save $7.5 million in 2013–14 by rejecting the administration’s proposal to increase an existing grant to cities to support police services. The administration provided no workload justification for the proposal, nor is the augmentation necessary to address the administration’s concern that the grants could not be provided to all cities in 2013–14.

Opportunities for Legislative Oversight. The relatively small number of major criminal justice proposals this year provides the Legislature with an opportunity to do more oversight of existing programs. This report highlights several such areas that could use such oversight. For example, trial courts face ongoing budget reductions and beginning in 2014–15 will no longer have significant reserves with which to offset these reductions. The Legislature will want to have judges, court executives, and other court stakeholders report on what plans they are making to implement reductions, how these plans will impact court users, and what options the courts and the Legislature have to reduce court operations costs. We also recommend that the federal court–appointed Receiver managing the prison medical program report at budget hearings on a new staffing methodology that he is implementing. Finally, we recommend that the Legislature require the Board of State and Community Corrections (BSCC) to report on its efforts to develop strategies for providing greater technical assistance to local criminal justice agencies, as well as expand its criminal justice data collection program.

The primary goal of California’s criminal justice system is to provide public safety by deterring and preventing crime, punishing individuals who commit crime, and reintegrating criminals back into the community. The state’s major criminal justice programs include the court system, prisons and parole, and the Department of Justice (DOJ). The Governor’s budget proposes General Fund expenditures of about $10 billion for judicial and criminal justice programs. Below we (1) discuss recent criminal justice trends, (2) describe recent trends in state spending on criminal justice, and (3) provide an overview of the major changes in the Governor’s proposed budget for criminal justice programs in 2013–14.

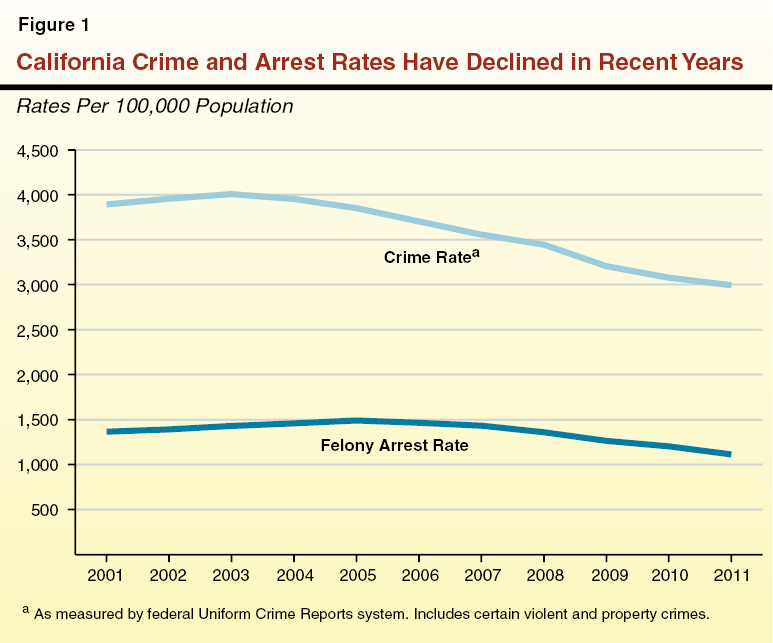

Crime and Arrest Rates Decline in Recent Years. The past three decades have seen a significant decline in the rate at which Californians report crimes to law enforcement, as well as a similar decline in the rate of law enforcement arrests for felony offenses. As shown in Figure 1, the crime rate in California—measured as the number of selected crimes reported per 100,000 population—has declined by 23 percent between 2003 and 2011 (the most recent year that data is available). Similarly, the felony arrest rate has declined by 18 percent between 2005 and 2011. There is no consensus among researches as to what is driving the declining crime rate in California. We note, however, that California’s declining crime rate mirrors national trends. While it is also not clear what is driving the recent drop in the state’s arrest rate, that decline could reflect both the decrease in crime, as well as the effects of local budget reductions to law enforcement agencies due to the recession. (For more information on recent criminal justice statistics in the state, see our January 2013 report California’s Criminal Justice System: A Primer.)

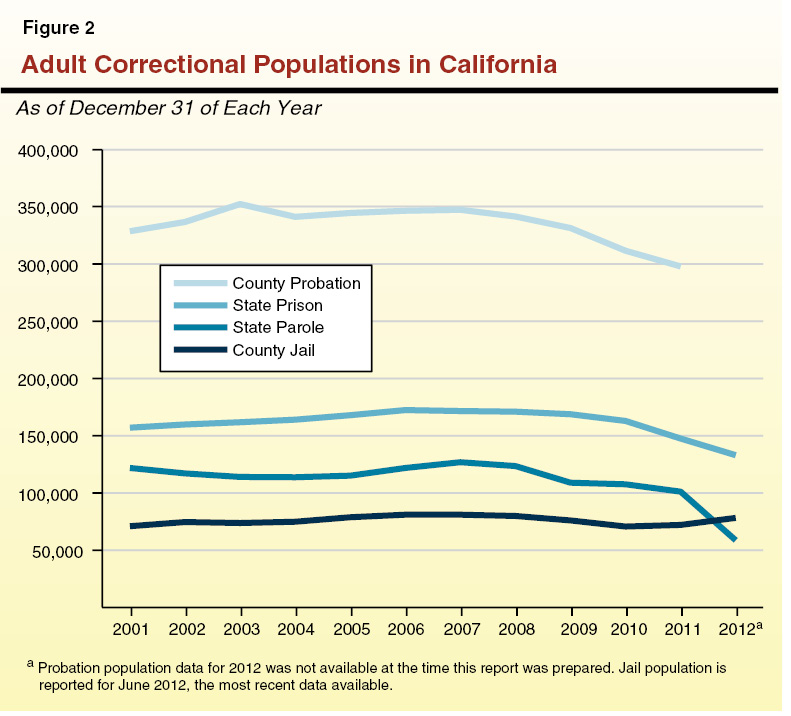

Recent Policy Changes Likely to Affect Correctional Populations in Coming Years. Individuals convicted of crimes can be placed under correctional supervision. Less serious offenders generally are sentenced to county jail and/or probation, while more serious offenders are sentenced to state prison followed by state parole. Figure 2 shows state and local correctional populations over the last decade. As indicated, all of these offender populations decreased by varying amounts in recent years until 2011, at which time the county jail population increased while the other populations continued to decline. (At the time of this publication, data for the 2012 probation population was not available.) There are several likely explanations for these recent declines. First, declining crime and arrest rates have probably had some impact on the number of offenders sentenced to state and local corrections. Second, and probably more significantly, state and local governments have taken actions to reduce correctional budgets due to the recession. The state, for example, has made various policy changes in recent years designed to reduce the number of offenders in prison and on parole, including permitting greater use of medical parole, removing certain lower–level parolees from supervised caseloads, and increasing credits inmates can earn towards their release date. The most significant of these changes, however, happened in 2011 with the passage of “realignment” which, among other changes, made felons ineligible for state prison unless they had a current or prior conviction for a serious, violent, or sex–related offense. Realignment has already resulted in decreases of tens of thousands of inmates and parolees who are no longer eligible for state prison and parole. Conversely, under realignment more offenders will be sentenced to local jails and/or probation in coming years, which are likely to increase by a total of tens of thousands of offenders. Unfortunately, at the time of this publication, there is little data available on how realignment has affected local jail and probation caseloads. (For more information on realignment, see our August 2011 publication 2011 Realignment: Addressing Issues to Promote Its Long–Term Success.)

In addition, in November 2012 voters approved Proposition 36, which modified the state’s three strikes law. Proposition 36 requires that a life term in prison for a third strike generally be limited to those offenders who have two or more prior serious or violent convictions and whose new conviction is also a serious or violent offense. (Previously, the third strike could be any felony—not just a serious or violent felony.) The measure also allows existing third strikers to petition the courts for a reduced sentence if their third strike offense was a nonserious, non–violent offense. This measure could reduce the prison population by as many as a couple thousand inmates over the next few years, depending, in part, on how many current inmates are resentenced by the courts.

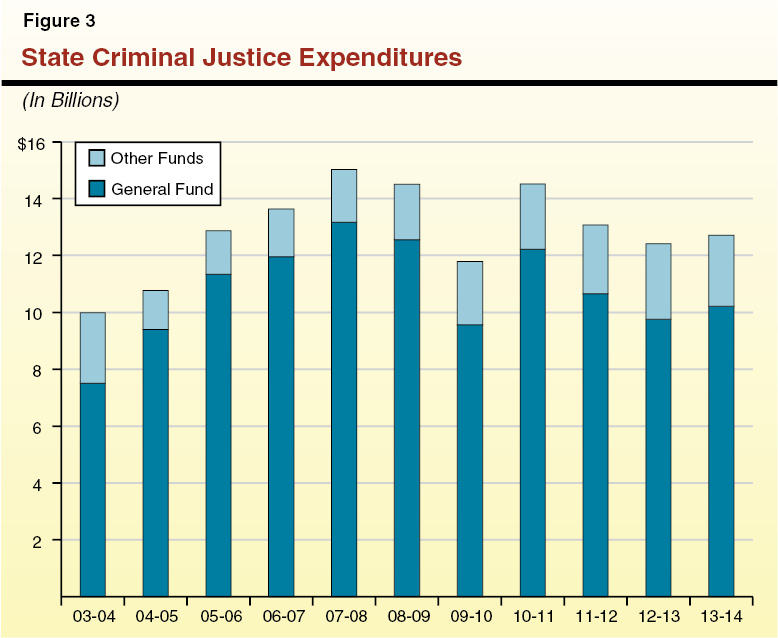

Realignment Has Reduced State Costs in Recent Years. Over the past decade, state spending on criminal justice programs has changed in sync with the state’s fiscal condition. As shown in Figure 3, state spending on criminal justice increased to about $15 billion ($13 billion General Fund) in 2007–08, an increase of 50 percent since 2003–04. In comparison, total state spending on criminal justice was about $13 billion in 2011–12. Much of the decline in 2011–12 was the result of the 2011 realignment, which shifted responsibility for several major criminal justice programs—including the shift of trial court security costs and various grant programs—to counties. Over the past decade, roughly four out of every five dollars spent on criminal justice has been from the General Fund.

Figure 4 summarizes expenditures from all fund sources for criminal justice programs in 2011–12 and as revised and proposed by the Governor for 2012–13 and 2013–14. As shown in the figure, total spending on criminal justice programs is proposed to increase from an estimated $13 billion in the current year to $13.2 billion in the budget year. This is an increase of 1.9 percent. General Fund spending is proposed to increase by 4.3 percent over current–year expenditure levels. As described in more detail below, this General Fund increase is primarily due to the restoration of one–time reductions in the judicial branch.

Figure 4

Judicial and Criminal Justice Budget Summary

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

Actual 2011–12

|

Estimated 2012–13

|

Proposed 2013–14

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Actual

|

Percent

|

|

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

|

$9,421

|

$8,932

|

$8,965

|

$33

|

0.4%

|

|

General Fund

|

9,206

|

8,662

|

8,694

|

32

|

0.4

|

|

Special and other funds

|

215

|

270

|

271

|

2

|

0.6

|

|

Judicial Branch

|

$3,100

|

$2,901

|

$3,106

|

$206

|

7.1%

|

|

General Fund

|

1,215

|

755

|

1,155

|

400

|

53.0

|

|

Special and other funds

|

1,885

|

2,146

|

1,951

|

–194

|

–9.1

|

|

Department of Justice

|

$585

|

$727

|

$754

|

$27

|

3.7%

|

|

General Fund

|

101

|

167

|

174

|

8

|

4.5

|

|

Special and other funds

|

484

|

561

|

580

|

19

|

3.4

|

|

Board of State and Community Corrections

|

—

|

$134

|

$129

|

–$5

|

–3.4%

|

|

General Fund

|

—

|

42

|

44

|

3

|

6.7

|

|

Special and other funds

|

—

|

92

|

85

|

–7

|

–7.9

|

|

Other Departmentsa

|

$276

|

$283

|

$264

|

–$19

|

–6.8%

|

|

General Fund

|

105

|

84

|

64

|

–20

|

–23.8

|

|

Special and other funds

|

171

|

199

|

200

|

1

|

0.3

|

|

Totals, All Departments

|

$13,382

|

$12,977

|

$13,219

|

$242

|

1.9%

|

|

General Fundb

|

$10,628

|

$9,710

|

$10,132

|

$422

|

4.3%

|

|

Special and other funds

|

2,754

|

3,267

|

3,087

|

–180

|

–5.5

|

Major Budget Proposals. The Governor’s budget includes relatively few major changes, particularly compared to prior years that included major policy changes (such as realignment) and significant budget cuts such as to the courts. Proposed funding for CDCR, which comprises two–thirds of total spending in this program area, is basically flat. The department’s budget includes additional correctional savings that will result from the continuing impact of realignment, as well as savings from reduced community corrections performance grants (discussed in more detail later in this report). These savings will be offset from additional costs associated with employee compensation (especially the expiration of the personal leave policy at the end of the current year) and the additional staff necessary to activate two new prison facilities in Stockton. The Governor’s proposed budget for the judicial branch includes the restoration of $418 million from the General Fund (which is being offset by special funds and trial court reserves in the current year). The budget also includes a one–time transfer of $200 million from court construction funds to the General Fund, as well as the use of court construction funds to pay service payments on a new courthouse in Long Beach.

Budget Assumes 2011 Public Safety Realignment Funding on Track. As described above, the 2011–12 budget package included statutory changes to realign several criminal justice and other programs from state responsibility to local governments, primarily counties. Along with the shift—or realignment—of programs, state law realigned revenues to locals. Specifically, current law shifts a share of the state sales tax, as well as Vehicle License Fee revenue, to local governments. The passage of Proposition 30 by voters in November 2012, among other changes, guaranteed these revenues to local governments in the future. The Governor’s budget includes an estimate of revenues projected to go to local governments over the next few years. These estimates are generally in line with prior estimates. As shown in Figure 5, total funding for the criminal justice programs realigned is expected to increase from $1.4 billion in 2011–12 to $2.2 billion in 2013–14.

Figure 5

Estimated Revenues to Counties for 2011 Realignment of Criminal Justice Programs

(In Millions)

|

|

2011–12

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

|

Community corrections

|

$354.3

|

$920.2

|

$1,088.6

|

|

Trial court security

|

446.9

|

506.7

|

518.7

|

|

Law enforcement grants

|

489.9

|

489.9

|

489.9

|

|

Juvenile justice grants

|

97.2

|

109.1

|

121.1

|

|

District attorneys and public defenders

|

12.7

|

19.8

|

23.1

|

|

Totals

|

$1,401.0

|

$2,045.7

|

$2,241.4

|

The judicial branch is responsible for the interpretation of law, the protection of an individual’s rights, the orderly settlement of all legal disputes, and the adjudication of accusations of legal violations. The branch consists of statewide courts (the Supreme Court and Courts of Appeal), trial courts in each of the state’s 58 counties, and statewide entities of the branch (the Judicial Council, Judicial Branch Facility Program, and the Habeas Corpus Resource Center). The branch receives revenues from several funding sources including the state General Fund, civil filing fees, criminal penalties and fines, county maintenance–of–effort payments, and federal grants.

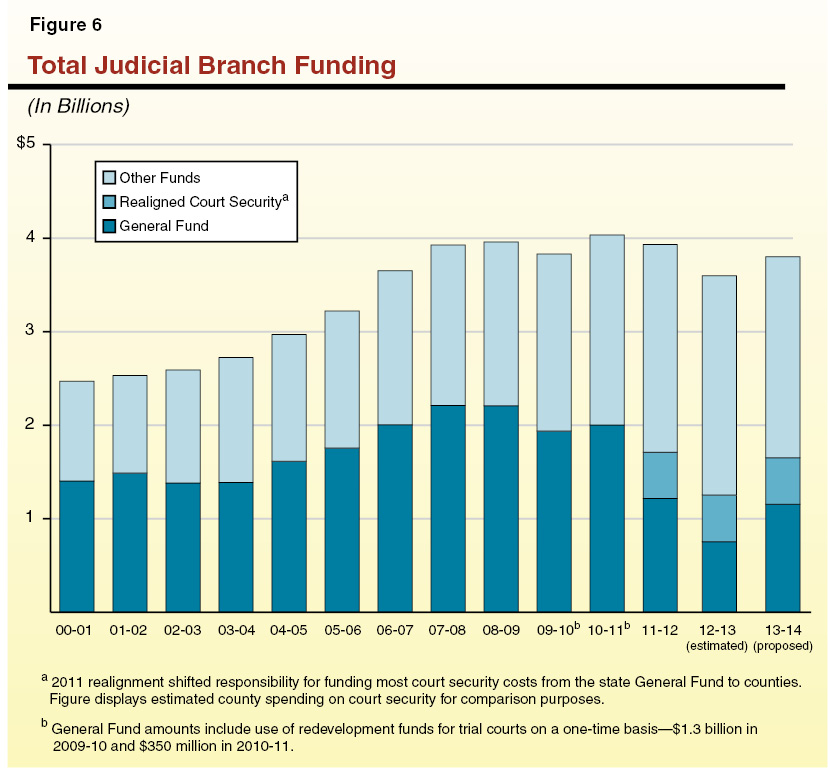

Figure 6 shows total funding for the judicial branch from 2000–01 through 2013–14. As shown in the figure, funding for the branch peaked in 2010–11 at roughly $4 billion but has declined somewhat in more recent years. General Fund support for the branch has been reduced significantly during this time. Under the Governor’s budget, the General Fund share of the entire branch budget will have declined from a high of 56 percent in 2008–09 to 30 percent in 2013–14. Much of these General Fund reductions have been offset by increased funding from other sources, such as transfers from branch special funds and additional revenues from court–related fee increases.

As shown in Figure 7, the Governor’s budget proposes $3.1 billion from all state funds to support the judicial branch in 2013–14, an increase of $206 million, or roughly 7 percent, above the revised amount for 2012–13. (These totals do not include expenditures from local revenues or trial court reserves, which we discuss in more detail below.) Of the total budget proposed for the judicial branch in 2013–14, nearly $1.2 billion is from the General Fund. This is a net increase of $400 million, or 53 percent, from the 2012–13 level. The increase in General Fund support is primarily due to the restoration of a one–time $418 million reduction to the trial courts in the current year.

Figure 7

Judicial Branch Budget Summary—All State Funds

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12

Actual

|

2012–13

Estimated

|

2013–14

Proposed

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

State Trial Courts

|

$2,680

|

$2,268

|

$2,431

|

$163

|

7.2%

|

|

Supreme Court

|

41

|

44

|

44

|

—

|

—

|

|

Courts of Appeal

|

199

|

202

|

205

|

2

|

1.0

|

|

Judicial Council

|

121

|

149

|

151

|

2

|

1.3

|

|

Judicial Branch Facility Program

|

174

|

224

|

263

|

39

|

17.4

|

|

Habeas Corpus Resource Center

|

12

|

14

|

14

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

($3,227)

|

($2,901)

|

($3,106)

|

($206)

|

(7.1%)

|

|

Offsets from local property tax revenuea

|

–$127

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$3,100

|

$2,901

|

$3,106

|

$206

|

7.1%

|

Prior–Year Budget Reductions and Offsets. The judicial branch has received a series of one–time and ongoing General Fund reductions since 2008–09. By 2012–13, the branch had received ongoing General Fund reductions totaling $778 million. Of this amount, $54 million were allocated to the state–level courts and branch entities, while $724 million in reductions were allocated to the trial courts. However, the Legislature and Judicial Council—the policymaking and governing body of the judicial branch—used various one–time and ongoing solutions to offset most of the reductions to the trial courts. For example, in 2012–13, about 80 percent of the total reductions to the trial courts was offset, primarily by using revenues from increased fines and fees, transfers from judicial branch special funds, and trial court reserves. (Reserves are the accumulation of unspent funds from prior years that are carried over and kept by each trial court.) Over the last five years, most of the transfers to the trial courts came from three special funds: the State Court Facilities Construction Fund (SCFCF), the Immediate and Critical Needs Account (ICNA), and the State Trial Court Improvement and Modernization Fund (IMF). (The IMF is used to fund various efforts, such as judicial education programs, self–help centers, and technology projects.)

Recent Court Actions to Implement Reductions. Despite most of the reductions being offset, the trial courts had to absorb $214 million in General Fund reductions in 2011–12 and 2012–13. Based on our discussions with officials from and visits to various trial courts throughout the state, we find that trial courts have taken various actions to accommodate these reductions. These actions include leaving staff vacancies unfilled to reduce employee compensation costs, renegotiating contracts, delaying purchases, closing courtrooms or courthouses, reducing clerk office hours, and reducing self–help and family law services. The impacts of these actions vary across courts and depend on the specific operational choices these courts have made. One commonly reported operational consequence of these actions is reduced public access to court services. For example, many courtroom and courthouse closures occurred in outlying branch locations, which now forces some court users to travel further distances to go to a different location. Moreover, the additional distance can make it difficult for some court users to make their court appearances, such as to contest evictions or resolve custody disputes. Additionally, courts report that reductions in service hours of clerks’ offices, self–help centers, and family law offices result in long lines and, in some cases, court users being turned away. Consequently, more self–represented individuals appear in court with incomplete or inaccurate forms requiring greater judicial time.

Other commonly reported operational consequences include longer wait times for court services and hearings, as well as increased backlogs in court workload. For example, a number of courts report that a reduction in staff who provide mediation services in custody cases has resulted in two to four month delays in obtaining a mediation appointment. Because mediation is required before a judge can issue a custody or support order, court users sometimes wait months before the court can resolve the custody issue. Additionally, court staff frequently prioritize processing documents necessary to meet statutory deadlines or that are needed for upcoming cases. Consequently, staff delay the processing of lower priority documents, which can negatively affect court users who need these documents processed in order for their case to proceed or conclude. For example, some courts report additional delays of six months or longer to process default civil judgments, which generate the final court order authorizing plaintiffs to collect compensation.

Efforts to Reduce Impacts on Court Users. In order to help minimize the extent to which the above actions affected court users, a number of courts made various changes. These changes include installing dropboxes for individuals to submit court paperwork when clerks’ offices are closed, kiosks where individuals can pay for traffic tickets, and online systems for individuals to automatically book hearings in select case types. Some courts have made multiyear investments, such as shifting to electronic filing of documents in certain case types. The Legislature also sought to minimize the impact on trial courts. For example, during its deliberations on the 2012–13 budget, the Legislature requested that the judicial branch submit a report on potential operational efficiencies, including those requiring statutory amendments. The Legislature’s intent was to identify efficiencies that, if adopted, would help the trial courts address their ongoing budget reductions. In May 2012, the judicial branch submitted to the Legislature a list of 17 measures that would result in greater operational efficiencies, reduced costs, or additional court revenues. This list was approved by the Judicial Council after consultation with trial court executives and presiding justices.

The Governor’s budget for 2013–14 fully restores a $418 million one–time reduction to the trial courts made in 2012–13. It also assumes that $200 million in trial court reserves will be available for use by the trial courts to offset previously approved reductions. In addition, the Governor proposes statutory changes to implement 11 of the 17 options identified by the judicial branch in its May 2012 report to the Legislature. Of the 11 proposed changes, 4 changes would reduce trial court workload and operating costs, and 7 would increase user fees to support ongoing workload. Examples of the proposed changes include amending the requirement to provide preliminary hearing transcripts in all felony cases and increasing fees to cover costs of mailing certain documents. A summary of the full list of 11 proposed administrative efficiencies and user fees are provided in the nearby box. The Governor estimates that these changes would provide the courts with about $30 million in ongoing savings or revenues to help address prior–year budget reductions.

The Governor proposes the following administrative efficiencies and user fee increases to generate savings or increase revenues to help trial courts address ongoing reductions. At the time of this report, neither the administration nor the judicial branch had provided estimates of the savings or additional revenue that could be achieved for most of the proposed changes. The proposed administrative efficiencies and increased user fees are described in more detail below.

Court–Ordered Debt Collection. Courts (or sometimes counties on behalf of courts) may choose to utilize the state’s Tax Intercept Program, operated by the Franchise Tax Board (FTB) with participation by the State Controller’s Office (SCO), to intercept tax refunds, lottery winnings, and unclaimed property from individuals who are delinquent in paying fines, fees, assessments, surcharges, or restitution ordered by the court. Current law allows FTB and SCO to require the court to obtain and provide the social security number of a debtor prior to running the intercept. Under the proposed change, courts will no longer be required to provide such social security numbers to FTB. Instead, FTB and SCO (who issues payments from the state) would be required to use their existing legal authority to obtain social security numbers from the Department of Motor Vehicles. This change will reduce court costs associated with attempting to obtain social security numbers from debtors.

Destruction of Marijuana Records. Courts are currently required to destroy all records related to an individual’s arrest, charge, and conviction for the possession or transportation of marijuana if there is no subsequent arrest within two years. Under the proposed change, courts would no longer be required to destroy marijuana records related to an infraction violation for the possession of up to 28.5 grams of marijuana, other than concentrated cannabis. This proposed change would reduce staff time and costs associated with the destruction process.

Preliminary Hearing Transcripts. Courts are currently required to purchase preliminary hearing transcripts from certified court reporters and provide them to attorneys in all felony cases. In all other cases, the courts purchase transcripts upon the request of parties. Under the proposed change, courts would only be required to provide preliminary hearing transcripts to attorneys in homicide cases. Transcripts would continue to be provided upon request for all other case types. This change reduces costs as the court will no longer be required to purchase copies of all non–homicide felony cases from the court’s certified court reporter, but will only need to purchase them when specifically requested.

Court–Appointed Dependency Counsel. Current law states that parents will not be required to reimburse the court for court–appointed counsel services in dependency cases if (1) such payments would negatively impact the parent’s ability to support their child after the family has been reunified or (2) repayment would interfere with an ongoing family reunification process. Designated court staff currently has the authority to waive payment in the first scenario, but are required to file a petition for a court hearing to determine whether payment can be waived in the second scenario. Under the proposed change, staff would be permitted to waive payments under this second scenario, thereby eliminating the need for some court hearings.

Exemplification of a Record. Exemplification involves a triple certification attesting to the authenticity of a copy of a record by the clerk and the presiding judicial officer of the court for use as evidence by a court or other entity outside of California. The fee for this certification is proposed to increase from $20 to $50. The cost of a single certification is $25. The increased fee is estimated to generate $165,000 in additional revenue.

Copies or Comparisons of Files. The fee for copies of court records is proposed to increase from $0.50 to $1 per page, which is estimated to generate an additional $5.9 million in revenue. Additionally, fees to compare copies of records with the original on file would increase from $1 to $2 per page.

Record Searches. Current law requires court users to pay a $15 fee for any records request that requires more than ten minutes of court time to complete. Typically, courts interpret this to mean that the fee can only be applied when the search for any single record takes more than ten minutes to complete, regardless of the total number of requests made by the requester. Under the Governor’s proposal, courts would charge a $10 administrative fee for each name or file search request. A fee exemption is provided for an individual requesting one search for case records in which he or she are a party.

Small Claims Mailings. The fee charged for mailing a plaintiff’s claim to each defendant in a small claims action would increase from $10 to $15 to cover the cost of postal rate increases that have occurred over the past few years.

Deferred Entry of Judgment. Courts would be permitted to charge an administrative fee—up to $500 for a felony and $300 for a misdemeanor—to cover the court’s actual costs of processing a defendant’s request for a deferred entry of judgment. This occurs when the court delays entering a judgment on a non–violent drug charge pending the defendant’s successful completion of a court–ordered treatment (or diversion) program.

Vehicle Code Administrative Assessment. Courts would be required to impose a $10 administrative assessment for every conviction of a Vehicle Code violation, not just for subsequent violations as required under current law. This new assessment is estimated to generate $2.2 million in annual revenue.

Trial by Written Declaration. Currently, defendants charged with a Vehicle Code infraction may choose to contest the charges in writing—a trial by written declaration. Originally implemented to allow individuals living far from the court to contest the charge, courts have discovered that more and more individuals living close to the court have been using this service. If the local violator is unsatisfied with the decision rendered in the trial by declaration process, they may then personally contest the charges in court as if the trial by written declaration never took place. In recognition of the unintended increased workload, courts would be authorized to collect a non–refundable $50 administrative fee from individuals residing in the county in which a traffic citation was issued to process their request for a trial by written declaration. This new fee is estimated to generate $3.2 million in annual revenue.

Courts Must Absorb Additional $234 Million in Ongoing Reductions by 2014–15. While the Governor’s budget provides no new reductions, trial courts must still address ongoing reductions from prior years, totaling $724 million in 2013–14. The budget assumes that $476 million in resources will be available to help offset a large portion of this ongoing reduction (including the estimated savings or revenues from the Governor’s proposed administrative efficiencies and user fee increases). This leaves $248 million in reductions that will have to be absorbed by trial courts, an increase of $34 million over the amount already assumed to be absorbed by the trial courts in 2012–13. As shown in Figure 8, the total amount of ongoing reductions that would be allocated to the courts increases to $448 million in 2014–15, a total of a $234 million increase from the current year. The increase in 2014–15 reflects the fact that there will be less resources available to the courts (such as trial court reserves) to offset ongoing reductions. (We discuss this issue in more detail later in this report.)

Figure 8

Trial Courts Budget Reductions Through 2014–15

(In Millions)

|

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13 (Estimated)

|

2013–14 (Budgeted)

|

2014–15 (Estimated)

|

|

General Fund Reductions

|

|

One–time reduction

|

–$92

|

–$100

|

–$30

|

—

|

–$418

|

—

|

—

|

|

Ongoing reductions (cumulative)

|

—

|

–261

|

–286

|

–$606

|

–724

|

–$724

|

–$724

|

|

Total Reductions

|

–$92

|

–$361

|

–$316

|

–$606

|

–$1,142

|

–$724

|

–$724

|

|

Solutions to Address Reduction

|

|

Construction fund transfers

|

—

|

$25

|

$98

|

$213

|

$299

|

$55

|

$55

|

|

Other special fund transfers

|

—

|

110

|

62

|

89

|

102

|

52

|

52

|

|

Trial court reserves

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

385

|

200

|

—

|

|

Increased fines and fees

|

—

|

18

|

66

|

71

|

121

|

121

|

121

|

|

Statewide programmatic changes

|

—

|

18

|

14

|

19

|

21

|

48

|

48

|

|

Total Solutions

|

—

|

$171

|

$240

|

$392

|

$928

|

$476

|

$276

|

|

Reductions Allocated to the Trial Courtsa

|

$92

|

$190

|

$76

|

$214

|

$214

|

$248

|

$448

|

Proposed Efficiencies and Fee Increases Merit Consideration. The Governor’s proposed statutory changes for administrative efficiencies and user fee increases merit consideration because they will generate ongoing cost savings or new revenues that will help courts meet their ongoing reductions. As discussed above, all of these proposals have been vetted and are supported by the Judicial Council. To date, we have heard no significant concerns raised by court stakeholders regarding the efficiency proposals. While we recognize that the proposed fee increases may make it more difficult for those with less financial resources to access court services, the increases are designed to offset existing court costs to provide the services. While the Governor assumes that the proposed efficiencies and fee increases will generate revenues or savings of $30 million, fiscal estimates for most of the proposed items were not available at the time of this publication. It is, therefore, difficult for us to assess whether $30 million is a reasonable estimate that can be achieved.

Legislature Should Define Its Priorities for How Reductions Are Implemented. While the Governor’s proposed efficiencies and user fee increases provide some additional funds to help trial courts meet their ongoing reductions, additional solutions will still be required to address the bulk of their reduction. As indicated above, trial courts addressed $214 million of their ongoing reductions in 2011–12 and 2012–13 by making various operational changes. These actions frequently resulted in a backlog of cases, delays in processing court paperwork, and longer wait times for those seeking court services. Absent legislative action, trial courts will likely expand upon these actions to address $234 million in additional ongoing reductions that require solutions in 2014–15. This would likely further reduce public access to court services. Given the magnitude of additional reductions which must be addressed by the courts in 2014–15, the Legislature will want to (1) establish its own priorities for how the budget reductions will be implemented by the judicial branch and (2) determine whether to minimize further impacts to court users by providing additional offsetting resources on a one–time or ongoing basis. In making these decisions, the Legislature has several options. However, each of these options has distinct trade–offs and is discussed in more detail below. (An evaluation of potential trial court governance changes, which may also help the trial courts absorb their reduction, is currently underway and is discussed in the box below.)

Chapter 850, Statutes of 1997 (AB 233, Escutia and Pringle), more commonly known as the Lockyer–Isenberg Trial Court Funding Act of 1997, shifted primary financial responsibility for trial court operations from the counties to the state. This legislation sought to: (1) stabilize and simplify trial court funding and (2) promote greater efficiencies and uniformity in trial court operations. As a part of the 2012–13 budget, a working group—consisting of six appointees by the Chief Justice and four appointees by the Governor—was established to evaluate the state’s progress in achieving these goals. Specifically, this group was tasked with (1) conducting a statewide analysis of funding, workload, staffing, and operational standards; (2) evaluating factors affecting a trial court’s ability to provide equal access to justice; (3) identifying cost–efficient operational changes; and (4) increasing funding transparency and accountability. This group conducted its first meeting in November 2012 and is expected to provide a final report to the Judicial Council and Governor by April 2013.

We would note that we have previously offered three recommendations to further the goals of trial court realignment: (1) shifting responsibility for the trial court employee personnel system from the individual trial courts to the state (specifically under the authority of Judicial Council), (2) establishing a comprehensive trial court performance assessment program, and (3) establishing a more efficient division of responsibilities between the Administrative Office of the Courts—the staffing agency for the Judicial Council—and trial courts. Implementation of these changes have the potential to reduce trial courts costs, better prioritize funding among courts, and increase efficiency. (Please see our September 2011 publication, Completing the Goals of Trial Court Realignment, for further description of these recommendations.)

Given the ongoing nature of the prior–year reductions, we recommend that the Legislature focus on options that provide ongoing savings or revenues for court operations. Such options include:

We recommend approval of the Governor’s proposed trailer bill language to implement administrative efficiencies and increase user fees as they provide trial courts with ongoing fiscal relief. Further, we recommend that the Legislature request that judges, court executives, court employees, and other judicial branch stakeholders identify at budget hearings this spring additional efficiencies that could provide further savings. This could provide the Legislature with additional options that, if adopted, could further offset ongoing General Fund reductions. However, the Legislature may be concerned that the ongoing reductions to the trial courts could have increasingly negative impacts on court users, especially as the amount of ongoing budget reductions that the trial courts must absorb increases in 2014–15. Thus, the Legislature should require the judicial branch to report at budget hearings on how the trial courts plan to implement their remaining ongoing budget reductions and what impacts any operational changes may have upon public access to the courts in the future.

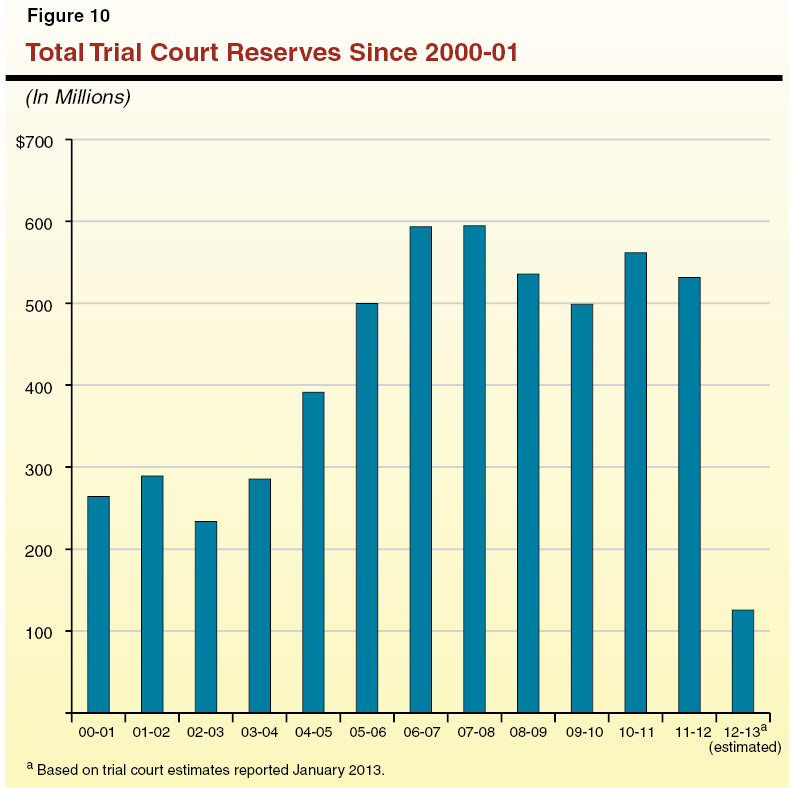

Chapter 850, Statutes of 1997 (AB 233, Escutia and Pringle), allowed Judicial Council to authorize trial courts to establish reserves to hold any unspent funds from prior years. Chapter 850 did not place restrictions on the amount of reserves each court could maintain or how they could be used. As shown in Figure 10, trial courts had $531 million in reserves at the end of 2011–12. The judicial branch estimates that reserves will decrease to roughly $125 million by the end of 2012–13. This decline reflects, in large part, the expectation in the 2012–13 budget that courts would use $385 million of their reserves to offset General Fund reductions.

These reserves consist of funding designated by the court as either restricted or unrestricted. Restricted reserves include (1) funds set aside to fulfill contractual obligations or statutory requirements and (2) funds usable only for specific purposes. Examples of restricted reserves include funds set aside to cover short–term facility lease costs, service contracts, license agreements, and children’s waiting rooms costs. Unrestricted reserves, on the other hand, are funds that are available for any purpose. Unrestricted funds are generally used to avoid cash shortfalls caused by normal revenue or expenditure fluctuations, to make one–time investments in technology or equipment, and to cover unanticipated costs.

As part of the 2012–13 budget package, the Legislature approved legislation to change the above reserve policy that allows trial courts to retain unlimited reserves. Specifically, beginning in 2014–15, each trial court will only be allowed to retain reserves of up to 1 percent of its prior–year operating budget. The judicial branch estimates that, in total, trial courts will be able to retain up to $22 million in 2014–15. Additionally, legislation was approved to establish a statewide trial court reserve, managed by the Judicial Council, beginning in 2012–13. This statewide reserve consists of 2 percent of the total funds appropriated for trial court operations in a given year—$27.8 million in 2012–13. Trial courts can petition the Judicial Council for an allocation from the statewide reserve to address unforeseen emergencies, unanticipated expenses for existing programs, or unavoidable funding shortfalls. Any unexpended funds in the statewide reserve would be distributed to the trial courts on a prorated basis at the end of each fiscal year.

The Governor’s budget maintains the new reserve policy enacted as part of the 2012–13 budget. The administration also states that it plans to propose budget trailer legislation designed to assist the judicial branch manage monthly trial court cash flows effectively in the absence of individual court reserves. As discussed above, the Governor’s budget also assumes that trial courts will utilize $200 million in reserves in 2013–14 to help offset ongoing General Fund reductions.

Assumption of Available Reserves May Be Overstated. As mentioned earlier, the trial courts currently estimate that approximately $125 million in reserves will be available at the end of 2012–13 for use in the budget year. This is less than the $200 million that the Governor assumes will be available to offset ongoing General Fund reductions to the trial courts. In addition, the majority of the $125 million in projected reserves is expected to be restricted leaving only about $51 million of unrestricted funds available for discretionary uses. To the extent trial courts have less in available reserves than the $200 million the Governor’s budget plan assumes, courts would likely have to take additional actions to accommodate the reduction. Since these estimates are being made midway through the current fiscal year, the final amount of reserves available for use may be significantly higher or lower than the branch’s current estimates depending on what operational actions trial courts take over the latter half of the year.

Reserves Cap Has Presented Unintended Challenges. The Legislature enacted the new reserves policy to ensure greater consistency with state departments and agencies, which generally are not authorized to retain reserves. However, the ability to retain unlimited reserves provided trial courts with a great deal of financial autonomy in the past. Thus, the limitation of reserves to 1 percent of prior–year operating budgets, as well as the withholding of trial court operation funding to create a 2 percent statewide reserve, presents a number of unintended challenges which require new judicial branch policies and procedures. Some of these may also require statutory changes. These issues include:

- Cash Shortfalls. Trial courts receive allocations from the state on a monthly basis, which sometimes is not enough cash to cover all operating expenses in a given month. Courts currently use their reserves to cover this gap in funding to pay all of their bills on time and avoid cash shortfalls. In addition, the courts often use their reserves to ensure that certain court programs can continue to operate even when there are delays in federal or other reimbursements for those programs. For example, federal reimbursements for child support commissioners and facilitators are often delayed by up to a year or longer, but courts are able to use their reserves to ensure that this program continues to operate. The potential for cash shortfalls is exacerbated by the requirement that the branch maintain a 2 percent statewide reserve. Each court will receive a monthly state allocation that is 2 percent smaller than what they would otherwise receive, thereby reducing the size of the local reserve they are allowed to keep.

- Payroll Requirements. Courts may process their own employee payroll or utilize a third–party vendor, such as the county personnel agency or a private company. These third–party vendors often require the court to maintain the equivalent of one or more months of court employee salaries in reserves to ensure that the court has sufficient funds to reimburse the county. This single reserve requirement can exceed 10 percent of a court’s annual budget amount, which is well in excess of the 1 percent limit that will go into effect under current law. Without an exemption of these funds from the new reserves limit, courts may have difficulty making employee payroll on a monthly basis or may no longer be able to use the third party vendor.

- Restricted Funds. As discussed previously, restricted reserves are funds constrained by statute, contract, or use for a specific purpose. As such, they are often not easily accessible for alternative uses by the courts. The new reserve policy does not exempt restricted funds from this 1 percent cap. Consequently, courts will have fewer unrestricted funds available for discretionary uses and may be forced to break existing contracts to reduce their reserves to meet the 1 percent cap. In some courts, obligations in restricted reserves may actually exceed the court’s cap.

- Projects Traditionally Funded Using Reserves. Historically, trial courts have used their reserves to fund certain projects and have not had to have these projects approved by the Judicial Council or the Legislature. For example, courts have built up reserves to purchase expensive technology or other services, often designed to help the court operate more efficiently, support additional workload, or provide the public with greater access to court services. Past projects include replacing or updating their case management systems as well as document management, collections, electronic filing, and electronic access technologies. Additionally, some courts report using their reserves to support other unique programs or practices. For example, the Shasta superior court uses its reserve to pay the salaries of their collections staff, who collect court–ordered debt for itself as well as a number of smaller trial courts, thereby minimizing the costs of collections for itself and all of its partners. The current reserve policy limits the ability for courts to save and plan over time for similar projects and programs in the same ways. Instead, the Legislature and judicial branch will likely need to establish new processes for prioritizing and funding those projects determined to be of greatest value to the state.

Our understanding is that the administration’s proposed budget trailer legislation related to reserves will address some of the challenges discussed above. At the time of this analysis, however, the administration’s proposed legislation was not available. Therefore, we withhold recommendation pending the provision of this language. After the administration has provided its proposed language to the Legislature, we will review it at that time and advise the Legislature on the degree to which it addresses the issues outlined above.

Background. Chapter 311, Statutes of 2008 (SB 1407, Perata), authorized increases in criminal and civil fines and fees to finance up to $5 billion in trial court construction projects. (These funds may also be used for other facility–related expenses such as maintenance and modification of existing courthouses.) The revenue from the fines and fees are deposited in ICNA established by Chapter 311. In accordance with the legislation, the Judicial Council selected 39 construction projects deemed to be of “immediate” or “critical” need for replacement—often because of structural, safety, or capacity shortcomings of the existing facilities—that would be funded from ICNA. This account receives roughly $300 million annually in revenue.

Governor’s Proposal. Recent budgets have transferred or loaned hundreds of millions of dollars from ICNA to help address the state’s fiscal problems. The Governor’s budget proposes a new one–time $200 million transfer from ICNA to the General Fund. The budget also reflects the ongoing transfer of $50 million from ICNA to support trial court operations as initially authorized as part of the 2012–13 budget. Additionally, the Governor proposes to delay from 2013–14 to 2015–16 the repayment of a $90 million loan that was made from ICNA to the General Fund in 2011–12. As we discuss below, repeated transfers and loans from ICNA have greatly decreased the availability of funds for construction projects.

Figure 11 summarizes the amount of ICNA revenues, expenditures, transfers, and loans that have occurred each year since the account was established and are proposed by the Governor for 2013–14. Under the Governor’s proposal, over two–thirds—a total of $1.1 billion—of all ICNA revenues over the period shown will have been transferred or loaned to offset reductions to trial courts or General Fund shortfalls by the end of 2013–14. (During this same time period, nearly $550 million will have also been transferred or loaned for similar purposes from another construction account—the SCFCF.) As shown in the figure, the budget assumes that the judicial branch will spend $110 million from ICNA on projects and other facility–related expenses in 2013–14, leaving a projected fund balance of $14 million at the end of the budget year.

Figure 11

Nearly Two–Thirds of ICNA Funds Transferred or Loaned by 2013–14

(In Millions)

|

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12

|

2012–13 Estimated

|

2013–14 Proposed

|

|

Adjusted beginning balance

|

—

|

$197

|

$258

|

$406

|

$61

|

$73

|

|

Revenues

|

$94

|

304

|

330

|

305

|

301

|

300

|

|

Total Resources

|

$94

|

$501

|

$588

|

$710

|

$362

|

$374

|

|

Expenditures

|

—

|

$129

|

$145

|

$106

|

$49

|

$110

|

|

Transfers and Loans

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Trial court operations transfers

|

—

|

25

|

73

|

143

|

240

|

50

|

|

General Fund transfers

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

310

|

—

|

200

|

|

General Fund loans

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

90

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals, Transfers and Loans

|

(—)

|

($25)

|

($73)

|

($543)

|

($240)

|

($250)

|

|

Total Expenditures, Transfers, and Loans

|

—

|

$154

|

$219

|

$649

|

$289

|

$360

|

|

Fund Balance

|

$94

|

$347

|

$370

|

$61

|

$73

|

$14

|

Projects to be Delayed Unspecified. Prior to the release of the Governor’s budget, the Judicial Council delayed eight ICNA–funded projects and directed all remaining projects to meet project–specific cost–reduction goals to address the drop in available funds in 2012–13. (As we discuss in the next section, the Judicial Council chose to delay four additional projects in 2012–13 in order to fund the service payments associated with the construction of a new courthouse in Long Beach from ICNA.) The council made its decision based on an evaluation of all projects using several operational and economic criteria. Figure 12 summarizes the current status of all court construction projects that are planned to be funded from ICNA.

Figure 12

ICNA Projects—Status and Current Estimated Project Cost

As of January 2013 (In Millions)

|

Project

|

Current Estimated Project Cost

|

Priority Need

|

|

Beginning Construction in 2013

|

$799

|

|

|

Alameda—East County Courthouse

|

110

|

Critical

|

|

Butte—North Butte County Courthouse

|

65

|

Immediate

|

|

Kings—Hanford Courthouse

|

124

|

Critical

|

|

San Joaquin—Juvenile Justice Center

|

4

|

Immediate

|

|

Santa Clara—Family Justice Center

|

234

|

Critical

|

|

Solano—Fairfield Old Solano Courthouse

|

28

|

Immediate

|

|

Sutter—Yuba City Courthouse

|

72

|

Immediate

|

|

Yolo—Woodland Courthouse

|

162

|

Immediate

|

|

Preconstruction Activities

|

$2,398

|

|

|

El Dorado—Placerville Courthouse

|

91

|

Critical

|

|

Glenn—Willows Courthouse

|

46

|

Critical

|

|

Imperial—El Centro Family Courthouse

|

60

|

Immediate

|

|

Inyo—Inyo County Courthouse

|

34

|

Critical

|

|

Lake—Lakeport Courthouse

|

56

|

Immediate

|

|

Los Angeles—Eastlake Juvenile Courthouse

|

90

|

Critical

|

|

Los Angeles—Mental Health Courthouse

|

84

|

Critical

|

|

Mendocino—Ukiah Courthouse

|

122

|

Critical

|

|

Merced—Los Banos Courthouse

|

32

|

Immediate

|

|

Riverside—Hemet Courthouse

|

119

|

Immediate

|

|

Riverside—Indio Juvenile and Family Courthouse

|

66

|

Immediate

|

|

San Diego—Central San Diego Courthouse

|

620

|

Critical

|

|

Santa Barbara—Criminal Courthouse

|

132

|

Immediate

|

|

Shasta—Redding Courthouse

|

171

|

Immediate

|

|

Siskiyou—Yreka Courthouse

|

78

|

Critical

|

|

Sonoma—Santa Rosa Criminal Courthouse

|

179

|

Immediate

|

|

Stanislaus—Modesto Courthouse

|

277

|

Immediate

|

|

Tehama—Red Bluff Courthouse

|

72

|

Immediate

|

|

Tuolumne—Sonora Courthouse

|

69

|

Critical

|

|

Indefinitely Delayed

|

$1,178

|

|

|

Fresno—County Courthouse

|

113

|

Immediate

|

|

Kern—Delano Courthouse

|

42

|

Immediate

|

|

Kern—Mojave Courthouse

|

44

|

Immediate

|

|

Los Angeles—Glendale Courthouse

|

127

|

Immediate

|

|

Los Angeles—Lancaster Courthousea

|

—

|

Immediate

|

|

Los Angeles—Santa Clarita Courthouse

|

64

|

Immediate

|

|

Los Angeles—Southeast Los Angeles Courthouse

|

126

|

Immediate

|

|

Monterey—South Monterey County Courthouse

|

49

|

Immediate

|

|

Nevada—Nevada City Courthouse

|

103

|

Critical

|

|

Placer—Tahoe Area Courthouse

|

23

|

Immediate

|

|

Plumas—Quincy Courthouse

|

35

|

Critical

|

|

Sacramento—Criminal Courthouse

|

452

|

Immediate

|

|

Total, All ICNA Projects

|

$4,375

|

|

As a result of the Governor’s proposed transfer of $200 million from ICNA to the General Fund, fewer projects are likely to be able to proceed in the budget year than the Judicial Council previously planned. In fact, the administration states that the transfer will likely delay most or all construction projects by at least a year, except for those projects scheduled to complete bond sales by the end of the current year (these will proceed as planned). The Judicial Council is responsible for determining specifically which projects to delay, and will base this decision on the recommendations of its Court Facilities Working Group Advisory Committee. At this time, the courts have not identified which projects will be delayed, what criteria will be used to prioritize projects, or when these decisions will be made.

LAO Recommendation. We recommend approval of the Governor’s proposal to transfer $200 million from ICNA to the General Fund because of the fiscal benefit it provides the state. We acknowledge, however, that this transfer will likely mean additional delays in court construction projects intended to be funded through ICNA. Therefore, we also recommend that the judicial branch report at budget hearings this spring on (1) which projects will be delayed, (2) how they plan to prioritize further delays, and (3) whether the need or scope of currently proposed ICNA projects have changed due to changes in trial court operations that were implemented to address budget reductions (such as the consolidation of existing courthouses). Such information will help ensure that the judicial branch’s construction plans are consistent with legislative priorities.

Background. The 2007–08 Budget Act directed the Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC), the agency that staffs the Judicial Council, to gather information regarding the possible use of a public–private partnership (P3) for the construction of a new facility to replace the existing courthouse in Long Beach. In December 2010, AOC entered into a P3 contract that required a private developer to finance, design, and build a new Long Beach courthouse, as well as to operate and maintain the facility over a 35–year period. At the end of this period, the judicial branch will own the facility. In exchange, the contract requires AOC to make annual service payments (also known as service fees) totaling $2.3 billion over the period. The actual amount of the annual service payment will vary each year primarily due to inflation, as well as other factors. These payments commence upon occupancy of the Long Beach courthouse, which is currently estimated to occur in September 2013.

Governor’s Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes using $34.8 million from ICNA to fund the first annual service payment for the Long Beach courthouse in 2013–14. Since occupancy of the new courthouse will not begin until September 2013, this payment reflects only partial–year occupancy of the facility. So, an additional $19.4 million is requested from ICNA for 2014–15 to make a full–year service payment of $54.2 million. In subsequent years, the judicial branch will have to submit budget requests to fund any growth in service payments.

Permissible Use of ICNA Funds. While the P3 contract between AOC and the Long Beach courthouse developer requires annual service payments by AOC, neither the contract nor statute specifies a particular funding source for these payments. Statute clearly permits the use of ICNA funds for service payments, and using this special fund rather than the General Fund to pay these costs provides the Legislature with additional General Fund resources to support other state priorities. The Long Beach courthouse project, however, was not originally on the list of projects the judicial branch planned to be funded from ICNA. Instead, the branch had assumed that the project would be funded from the General Fund. Therefore, the plan to use ICNA funds for these service payments, combined with reduced ICNA fund balances as previously discussed, resulted in a Judicial Council decision to indefinitely delay four court construction projects (the Fresno County, Southeast Los Angeles, Nevada City, and Sacramento Criminal courthouses).

LAO Recommendation. We recommend approval of the Governor’s proposal to use ICNA funds for service payments for the Long Beach courthouse. This proposal benefits the General Fund by tens of millions of dollars per year (potentially for the next 35 years), and it is a permissible use of ICNA funds.

The CDCR is responsible for the incarceration of adult felons, including the provision of training, education, and health care services. As of January 9, 2013, CDCR housed about 133,000 adult inmates in the state’s prison system. Most of these inmates are housed in the state’s 33 prisons and 42 conservation camps. Approximately 9,600 inmates are housed in either in–state or out–of–state contracted prisons. The CDCR also supervises and treats about 58,000 adult parolees and is responsible for the apprehension of those parolees who commit new offenses or parole violations.

In addition, about 800 juvenile offenders are housed in facilities operated by CDCR’s DJJ, which includes three facilities and one conservation camp. Prior to January 1, 2013, CDCR also supervised juvenile parolees. County probation departments, however, now have responsibility for supervising all juvenile offenders released from DJJ.

The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $9 billion ($8.7 billion General Fund) for CDCR operations in 2013–14. Figure 13 shows the total operating expenditures estimated in the Governor’s budget for the current year and proposed for the budget year. As the figure indicates, spending is virtually flat between the two years.

Figure 13

Total Expenditures for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2011–12 Actual

|

2012–13 Estimated

|

2013–14 Proposed

|

Change From 2012–13

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Prisons

|

$7,817

|

$7,612

|

$7,791

|

$179

|

2.4%

|

|

Adult parole

|

767

|

628

|

537

|

–91

|

–14.5

|

|

Administration

|

449

|

442

|

409

|

–33

|

–7.5

|

|

Juvenile institutions and parole

|

231

|

179

|

186

|

7

|

3.8

|

|

Board of Parole Hearings

|

85

|

71

|

42

|

–29

|

–40.7

|

|

Corrections Standards Authoritya

|

71

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$9,421

|

$8,932

|

$8,965

|

$33

|

0.4%

|

The department’s budget includes increased spending related to higher employee compensation costs caused by the expiration of the Personal Leave Program, the activation of new prison health care facilities, the expansion of inmate rehabilitation programs, and increased use of in–state contract beds for inmates. This additional spending is partially offset by proposed budget reductions, primarily related to additional savings from the 2011 realignment of adult offenders to counties. These budget reductions include operational savings associated with reduced state prison and parole populations, as well as decreased use of out–of–state contract beds for inmates. These changes are consistent with the administration’s 2012 plan (commonly referred to as the “blueprint”) to reorganize various aspects of CDCR’s operations, facilities, and budget in response to the effects of the 2011 realignment.

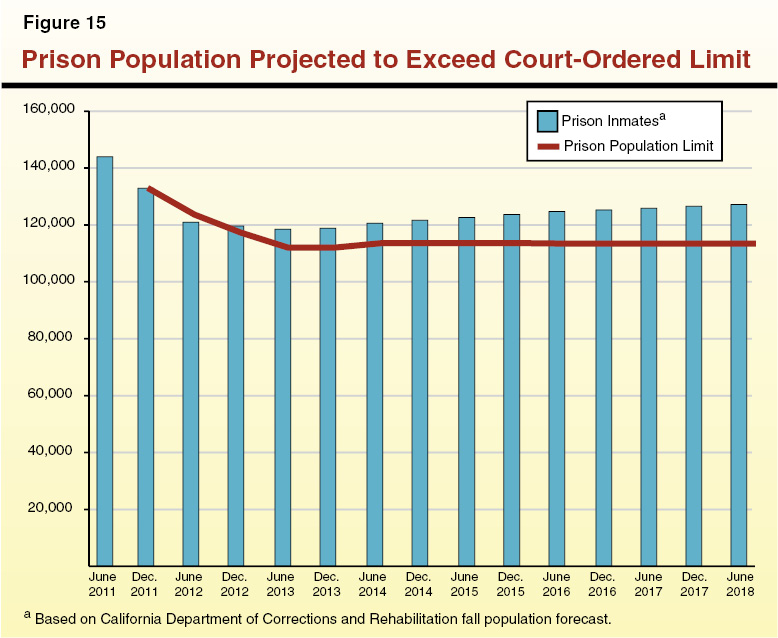

Background. The average daily prison population is projected to be about 129,000 inmates in 2013–14, a decline of roughly 3,600 inmates (3 percent) from the estimated current–year level. This decline is largely due to the 2011 realignment of lower–level felons from state to local responsibility. Although decreasing, the projected inmate population for 2013–14 is still about 3,200 inmates higher than was projected by CDCR in spring 2012. According to the department, this is due in part to higher–than–expected admissions to state prison. In addition, CDCR reports that more individuals on Post Release Community Supervision (PRCS) were convicted of new crimes and returned to prison than was originally projected. (As part of the 2011 realignment, individuals who do not have a current conviction for a serious or violent offense are generally supervised by counties on PRCS after serving their prison sentence, rather than by state parole agents.) The CDCR’s projections also show that the decline in the prison population is expected to slow down in the coming years and actually increase within a few years.

The average daily parole population is projected to be about 43,000 parolees in the budget year, a decline of about 15,000 parolees (25 percent) from the estimated current–year level. This decline is also largely a result of the 2011 realignment, which shifted from the state to the counties the responsibility for supervising certain offenders following their release from prison. The average daily population projected for 2013–14 is about 4,500 parolees lower than was initially projected by the department in spring 2012. According to CDCR, this is due to more parolees being discharged from supervision than expected in the first six months of 2012. In addition, CDCR projections show that the decline in the parole population is expected to slow down and even increase in coming years.

Governor’s Proposal. As part of the Governor’s January budget proposal each year, the administration requests modifications to CDCR’s budget based on projected changes in the prison and parole populations in the current and budget years. The administration then adjusts these requests each spring as part of the May Revision based on updated projections of these populations. The adjustments are made both on the overall population of offenders and various subpopulations (such as mentally ill inmates and sex offenders on parole). As can be seen in Figure 14, the administration proposes a net reduction of $14.6 million in the current year and a net increase of $2.3 million in the budget year.

Figure 14

Governor’s Population–Related Proposals

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2012–13

|

2013–14

|

|

Population Assumptions

|

|

|

|

Prison population 2012–13 Budget Act

|

129,461

|

125,434

|

|

Prison population 2013–14 Governor’s Budget

|

132,223

|

128,605

|

|

Prison Population Adjustments

|

2,762

|

3,171

|

|

Parole population 2012–13 Budget Act

|

66,753

|

47,417

|

|

Parole population 2013–14 Governor’s Budget

|

57,640

|

42,958

|

|

Parole Population Adjustments

|

–9,113

|

–4,459

|

|

Budget Adjustments

|

|

|

|

Inmate related adjustments

|

$13.9

|

$12.0

|

|

Jail contract reimbursements

|

—

|

8.9

|

|

Health care facility activations

|

–7.4

|

5.0

|

|

Parolee related adjustments

|

–21.1

|

–23.5

|

|

Proposed Budget Adjustments

|

–$14.6

|

$2.3

|

The current–year net reduction in costs is primarily due to savings from the larger than expected decline in the 2012–13 parolee population, as well as a delay in the activation of a 50–bed mental health crisis unit at California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo. These savings are partially offset by increased inmate costs due to the higher–than–expected inmate population and inmates returning from out–of–state contract beds. (The savings from reducing the number of out–of–state beds—totaling $84 million in the current year—are largely accounted for elsewhere in the Governor’s budget for CDCR.)

The budget–year net increase in costs is largely related to the higher–than–expected inmate population and back payments to counties for housing CDCR offenders (primarily parole violators) in jail in prior years. These costs are partially offset by the larger–than–expected decline in the parole population, as well as savings from a decline in certain populations of inmates needing mental health care.

Population Budget Request Generally Reasonable but Requires Current–Year Adjustment. In general, the administration’s projections of the prison and parole population appear to be accurate based on recent trends, and the associated budget adjustments are generally reasonable. We find, however, that one component of the administration’s funding request—specifically related to the provision of treatment services for sex offenders—is over–budgeted in the current year by about $15 million and requires greater transparency on an ongoing basis.

Prior to their release, parolees who are registered sex offenders are given risk assessments, and those classified as sufficiently high risk are placed on High Risk Sex Offender (HRSO) caseloads. These parolees are subject to more intensive supervision by parole agents and are required to participate in sex offender treatment programs. Specifically, HRSOs are required to receive relapse prevention therapy and undergo polygraph examinations, consistent with the sex offender containment model. This model is designed to both decrease the likelihood that these parolees will commit new sex offenses and increase the probability that new offenses are detected. The department relies on contractors to provide the treatment services to HRSOs. The department, however, has historically been unable to enter into a sufficient number of contracts to fully serve its HRSO population.

The Governor’s budget proposal includes enough funding to provide treatment to an average of about 3,300 HRSOs in 2012–13 and 4,100 HRSOs in 2013–14. The CDCR, however, estimates that it will only be able to serve an average of about 1,100 HRSOs in the current year because of past problems securing contracts with treatment providers. The department expects to have resolved these problems by the end of the current year. Accordingly, we estimate that the department is over–budgeted for these services by $15 million in 2012–13. The department informs us that these current–year savings may be needed to offset shortfalls elsewhere in its budget, specifically related to positions that had full–year funding eliminated in the 2012–13 budget but that were not actually eliminated until October 2012. At the time of this analysis, CDCR could not identify a specific dollar amount associated with this potential current–year shortfall.

Lack of Transparency for Parolee Sex Offender Program. For the budget year, CDCR informs us that it may be unable to fill all of the 4,100 treatment slots assumed in the Governor’s budget with HRSOs. This is because, at any given time, roughly one–third of HRSOs are unable to participate in the program because they are in county jail pending new criminal charges, have been revoked due to violations of their parole, or are at large. To the extent that CDCR has more treatment slots funded than HRSOs to participate in them at any given time, CDCR plans to use these funds to provide non–high risk sex offenders (non–HRSOs) treatment. In so doing, the department argues that it will be closer to compliance with Chapter 218, Statutes of 2009 (AB 1844, Fletcher)—also known as Chelsea’s Law—which requires that all sex offenders on parole be provided with sex offender treatment.

While Chapter 218 does require CDCR to provide treatment to both HRSOs and non–HRSOs, the department’s plans raise several concerns. First, the request for sex offender treatment funding does not provide any estimate of the number of HRSOs versus non–HRSOs that will be served, making it difficult for the Legislature to understand and evaluate the department’s actual operational plans. Second, even though the department is only likely to have treatment slots available for a portion of the state’s non–HRSO parole population, it has not identified how it will prioritize which non–HRSOs will be placed in these programs. Third, it is not clear what type of treatment CDCR is providing to non–HRSOs, how effective the approach being used is, or whether it is the most cost–effective way to manage low–risk sex offenders. We are informed that CDCR is currently running a pilot program in Fresno in which non–HRSOs are being provided with sex offender treatment. The results of the pilot are not available at this time—something the department should provide to the Legislature before expanding the program.

LAO Recommendations. We withhold recommendation on the administration’s adult population funding request until the May Revision. We will continue to monitor CDCR’s populations, and make recommendations based on the administration’s revised population projections and budget adjustments included in the May Revision. We recommend, however, that the Legislature direct the department to make adjustments as part of the May Revision to reflect the correct number of treatment slots that will be available in the current year, as well as distinguish between the number of HRSO and non–HRSO parolees that will be in treatment programs. We also recommend that the Legislature direct the department to report at budget hearings on the provision of sex offender treatment to non–HRSOs. In particular, the department should report on (1) whether the treatment modality used for non–HRSOs is appropriate and (2) how the department will prioritize which non–HRSOs will be placed into treatment. If the department’s responses are satisfactory to the Legislature, we recommend that it direct the department to separately delineate funding for HRSO and non–HRSO treatment in subsequent budget proposals.