February 2007

Improving Alternative Education in California

Between 10 percent to 15 percent of high school students enroll in one of the state’s four alternative programs each year. These programs serve many of the state’s at-risk students. We recommend fixing the state and federal accountability programs so that schools and districts are held responsible for the success of students in alternative programs. We also recommend funding reforms that reinforce the district’s responsibility for creating effective options for students.

Executive Summary

State law authorizes three types of alternative schools-continuation schools, community schools, and community day schools to serve high school students who are “at risk” of dropping out of school. In addition, some districts use independent study to educate at-risk high school students. Between 10 percent to 15 percent of high school students enroll in one of these programs each year.

Despite the importance of alternative education, existing K-12 accountability programs do not permit an evaluation of whether participating students are making progress. In fact, the state’s accountability system allows schools and districts to use referrals to alternative schools as a way to avoid responsibility for the progress of low-performing students. The way that the state finances alternative schools further blurs accountability and creates incentives that result in fewer services to these students.

By addressing these two issues, the Legislature can begin the process of improving alternative education in California. Improving state and federal accountability programs is a crucial first step. Schools and districts need to be held responsible for the success of students who are referred to local alternative programs. In addition, we also recommend the Legislature revise the state’s alternative school accountability program so that it focuses on learning gains and graduating students from high school.

We also recommend creating a new funding mechanism for the support of alternative programs that would reinforce the district’s responsibility for creating effective options for at-risk students. Our proposed block grant would give districts maximum flexibility to support district alternatives that best meet the needs of its students.

Alternative programs are designed, at least in part, to create a safety net for students who are unsuccessful in our regular comprehensive high schools. Currently, data are not adequate to answer the question of whether these programs serve this role. Our recommendations, therefore, would provide the data the Legislature needs to answer this question. More importantly, however, our recommendations would help ensure that all parties involved in the process-including school officials, teachers, parents, and students-would seek the answer to this question as well.

|

Introduction

In 2005, we issued

Improving High School: A Strategic Approach, which examined how well schools were serving different groups of high school students. In that report, we noted that about 30 percent of high school students left high school before graduating. This clearly signals a major problem in our K-12 education system.

Students who are at risk of dropping out of high school often attend an alternative school or program during their time in high school. This report explores the success of alternative programs, which includes alternative schools-continuation, community day, and community schools-and independent study programs. Specifically, it tries to answer the question of whether the system of alternative programs creates a sufficient number and type of quality educational settings that address the needs of students who are not successful in regular high schools.

In Chapters 1 and 2, we review the policy and fiscal structure of the existing programs and provide data that suggest how districts use them. Chapter 3 reviews research that provides insight into the operation of alternative programs and Chapter 4 summarizes the results of our site visits in the context of these research findings. Chapters 5 and 6 describe our recommendations for changes to the state’s accountability system and the state alternative programs.

Chapter 1: A Brief Overview of

Alternative Programs

State law authorizes three types of alternative schools that are targeted primarily at high school students: continuation schools, community day schools, and community schools. In addition, current law permits districts to operate independent study programs for high school students as an alternative to regular attendance at a comprehensive high school or alternative school. These four options constitute the range of alternatives used by most districts.

The state’s system of alternative schools has developed over many years. Continuation schools have existed in California since the early 1900s. Originally designed to give students who worked a more flexible approach to their education after age 16, continuation schools today often offer individualized instruction and smaller class sizes to students who find the large comprehensive high school unsuitable. (This can be due to a range of issues-from behavioral problems to falling behind in their studies.) Existing statutes authorizing community schools date from the 1970s. These schools, operated by county offices of education (COE), often serve students who are expelled for serious offenses in school or are involved with juvenile law enforcement agencies. The expansion of mandatory expulsion laws in the 1990s motivated the state to create community day schools. These schools provide districts with the option of operating a program similar to those run by county offices.

Local factors play a major role in the design and use of alternative programs. In general, community and community day schools are designed as short-term interventions that last about one semester. In contrast, continuation schools are usually designed as long-term placements for students. Independent study is sufficiently flexible to provide both short- and long-term placements.

Local factors also play a role in the types of students referred to these programs. Independent study, for instance, may serve both high- and low-performing students. The three alternative schools also serve a variety of different types of students depending on district needs and the range of options available locally.

In this chapter, we review the state-level framework for the three alternative schools and independent study. This includes a description of each program and its fiscal structure as specified in state law.

Program Framework for

Alternative Programs

Figure 1 summarizes five critical features of law for continuation, community day, and community schools. As the figure suggests, state law describes very general goals for the three schools. The statutory mission for continuation schools is the clearest-provide the courses students need to graduate from high school. For community schools, state law identifies providing individualized instruction as the purpose of the school. The statutes supply little guidance about the state’s intent in creating community day schools.

|

Figure 1

Statutory Framework for Alternative Schools |

|

|

Continuation |

Community Day |

Community |

|

Mission |

·

Complete courses for graduation |

·

None identified |

·

Individually planned education |

|

|

·

Emphasize work and intensive guidance |

|

·

Emphasize occupations and guidance |

|

|

· Meet students’ needs for flexible

schedule or occupational goals |

|

|

|

Eligible to Operate |

·

Districts |

·

Districts or county offices |

·

County offices |

|

Grades Served |

·

10-12 (at least 16 years old) |

·

K-12 |

·

K-12 |

|

Placement Criteria |

·

Volunteers |

·

Volunteers |

·

Volunteers |

|

|

·

Suspended or expelled |

·

Expelled |

·

Expelled |

|

|

·

Habitually truant or irregular

attendance |

·

Referred by SARBa |

·

Referred by SARBa |

|

|

|

·

Probation referred |

·

Homeless children |

|

|

|

|

·

Probation referred |

|

|

|

|

·

On probation |

|

Instructional Setting |

·

Small classes |

·

Small classes |

·

Small classes |

|

|

·

Individual instruction |

·

Individual instruction |

·

Individual instruction |

|

|

·

Independent study |

|

·

Independent study |

|

|

|

a

SARB—School Attendance Review Board. |

The figure also shows that the statutory features of community day and community schools are very similar. This was intentional, as the community day program was designed to provide districts the ability to operate a program similar to a community school (which may only be operated by COE). One major difference, however, is that current law prohibits community day schools from using independent study as a student’s instructional setting.

The authorizing laws for continuation schools also are similar to those of community day and community schools. All serve high school students, and continuation schools and community schools have an occupational focus. The types of students that may attend the three schools also are similar-all may serve students who volunteer as well as expelled students. State law also encourages the three schools to employ instructional settings that focus on individualized instruction and smaller class sizes.

Despite the similarities among the three programs, there also are important differences. State law requires districts serving high school students to operate at least one continuation school. Community day and community school programs are optional. In addition, continuation schools are permitted to enroll only students ages 16 and older (with limited exceptions), while community day and community schools may serve the full K-12 range of students. (Students in grades K-8 represent 15 percent of community school and 25 percent of community day school enrollments.)

Independent Study. State statutes define independent study as an “individualized alternative education designed to teach the knowledge and skills of the core curriculum.” Independent study fulfills a number of student needs. Students attending regular high schools may use independent study to take individual courses that are either not available at the school or not convenient to the student. Working students also can use independent study to continue classes during the times they cannot attend school. Students also may take all their classes through independent study.

State law requires each student to enroll in a school. Since the program is considered an instructional approach rather than a school, districts decide which school full-time independent study students “attend.” As a result, many of these students are shown as enrolled in a regular high school or other district school. Independent study may serve all K-12 students (about 28 percent of full-time independent study students are in grades K-8).

A significant number of requirements and restrictions exist in current law to shape the local approach to independent study. In general, these rules focus on the processes districts must follow in operating an independent study program. These include the following:

- Credentialed Teachers. Independent study students must work under the “general supervision” of certificated teachers. State law also mandates that only certificated teachers may evaluate the seat-time equivalent of an independent study student’s work for the purposes of state revenue limit funding.

- Individual Written Agreement. Districts must maintain a written agreement with each student (and parent) that specifies the dates of participation, methods of study and evaluation, and other resources to be made available to the student. The agreement also must inform students and parents that independent study is an option for the student (although it does not require the agreement to list the other options available to the student).

- Pupil-Teacher Ratios. Current law limits the number of students each independent study teacher may supervise. Specifically, the number of independent study students supervised may not exceed the overall student-certificated teacher ratio in the district.

- Educational Standards.

State law prohibits independent study from using an “alternative curriculum.” This restriction implies that independent study students must be held to the same standards as other district students. Current law, however, does not clarify what an alternative curriculum means or provide a means of enforcing the prohibition.

Fiscal Framework for

Alternative Programs

A second important element guiding the state’s system of alternative programs is the fiscal structure that supports local schools and programs. Figure 2 describes the basic features of the fiscal rules for the four programs.

|

Figure 2

Fiscal

Framework for Alternative Programs |

|

2004-05 |

|

|

Continuation |

Community Day |

Community |

Independent Study |

|

Supplemental Funding |

None |

$4,753 per ADAa

for districts |

$3,285 per ADA |

None |

|

|

|

$6,250 per ADA for county offices |

|

|

|

Funding Restrictions |

None |

Extra funds available for up to 0.5 percent of

district studentsb |

Extra funding for specified “severe” students only |

None |

|

|

|

Funds earned only when students attend more than the

minimum dayc |

|

|

|

Minimum Instruction Day |

3 hour day,

4 hours per week if working |

4 hour day |

4 hour day |

1 hour per week |

|

|

|

a

Average daily attendance. |

|

b

0.625 percent for high school districts. |

|

c

One-half of the supplemental funds are earned for a

fifth hour of instruction, with the other one-half

earned for a sixth hour. |

Supplemental Funding. Only community day and community schools receive extra funds to supplement revenue limits (which are general purpose grants provided for all students). The additional funds, however, come with a variety of restrictions and exceptions. For instance, the supplemental community day school funds are provided only for the fifth and sixth hour of attendance-the school receives no supplemental funds for a student who attends only four hours each day. The supplemental community school funds, alternatively, are provided for each day a student attends-no matter how many hours (although the student must be scheduled for at least four hours each day).

State law also limits the number or type of students eligible for supplemental funding. Unified school districts, for instance, may claim additional community day school funding for only 0.5 percent of its students (0.625 percent for high school districts). Community schools receive supplemental funding only for more “severe” students-those referred by the county probation department or expelled from school for specified reasons. For all other students, county offices receive the district’s revenue limit funding.

“After School” Funding. Community day schools also are eligible for $4.55 per student-hour of attendance for the seventh and eighth hour in a school day. This funding supports after school programs for students and provides tutoring, sports, and other activities for students at the end of the school day.

Minimum School Day. As Figure 2 indicates, state law permits exceptions for three of the alternative programs from the four-hour minimum school day that applies to regular schools. Independent study students must attend school an average of one hour a week to meet with their teacher to review work performed by the student. (This is typically on a one-on-one basis.) Continuation schools must offer a three-hour day (except for students who work or are assigned to independent study). Community schools have a four-hour minimum day except for students in independent study. Only community day schools must adhere to the four-hour a day standard for all students (and to receive extra funding, students must attend five or six hours).

State Expenditures. In 2004-05, the state spent $107 million in supplemental funding for alternative schools. Of this amount, community schools received $46 million in additional funds for attendance of the more severe students. The state spent $61 million for community day school subsidies, including $59.5 million for the fifth and sixth hours and $1.6 million for the after school component.

Conclusion

State law establishes a framework for alternative programs that affords districts great flexibility to design programs in ways that best meet local needs. The goals of these programs are vague, however, and the programs overlap in the groups of students they may serve. In addition, current law is inconsistent in the types of funding mechanisms used to support these programs. In the next chapter, we review data on the number of students enrolled in alternative programs and on the experience of students while enrolled in a program.

Chapter 2:

Use of Alternative Programs in California

Data from the California Department of Education (CDE) show that a significant number of students attend an alternative program at some point during the school year but that students stay in the programs for a relatively brief time. Data also indicate that a significant proportion of high school dropouts leave school while enrolled in an alternative program.

Significant Enrollment in

Alternative Programs

Currently, there are 851 alternative schools in California-an average of about 2 schools for each district in the state that serves high school students. Of these, 501 are continuation schools, 56 are community schools, and 294 are district or county administered community day schools (262 district and 32 county).

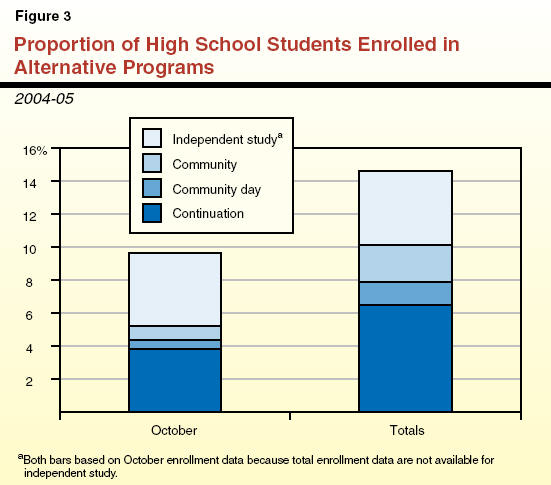

The number of students attending alternative programs also is large. Figure 3 displays the proportion of high school students enrolled in alterative schools in 2004-05. The figure includes two measures of enrollments. The left-hand bar reflects CDE data on the number of students in these programs as of the first Wednesday in October. This “snapshot” shows that about 10 percent of students were enrolled in an alternative program in October. The right-hand bar displays the proportion of students who enrolled in alternative programs at any point during the school year. It shows that about 15 percent of high school students enrolled in an alternative education option at some point during the 2004-05 school year. (Since the total enrollment data are not available for independent study, we used the October data for both bars in the figure.)

These data suggest that a significant proportion of each high school class attends an alternative program at some point during their four years in school. The CDE data do not track whether students enroll in more than one program during the year (or over the four years of high school). Without this critical information, it is not possible to determine the proportion of students who have some involvement with alternative programs.

Figure 3 also shows that continuation schools and independent study represent the largest alternative educational placements. Based on the October enrollment data, the two programs each enroll about 4 percent of all high school students, together representing 84 percent of alternative program students. Students enrolled in community day or county community schools account for only 1.4 percent of all high school students.

The data on independent study should be interpreted with care, as it is not possible to know the proportion of “at-risk” students among those in independent study. Districts use independent study in different ways and, as a result, may enroll a broad range of students in the program-not just at-risk students. Excluding independent study, just over 5 percent of students in grades 9-12 were enrolled in alternative programs in October 2004 and about 10 percent of high school students enrolled in these schools at some point during the year.

Alternative School Students

Attend for a Short Time

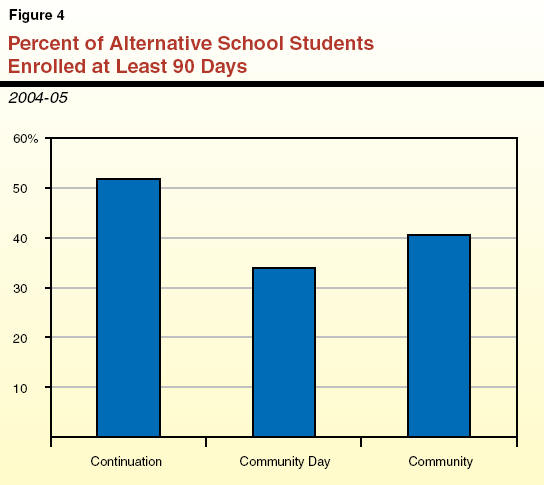

As Figure 3 indicates, alternative schools enroll many more students throughout the year than indicated by the October data. Alternative schools can accommodate the new students because most students attend for relatively brief periods. Figure 4 displays the percent of students in alternative schools who were enrolled for at least 90 days in 2004-05. Overall, less than one-half of all alternative school students attended for 90 days. While continuation schools reported the highest proportion of these longer-term students (52 percent), the rate was not dramatically higher than community schools (40 percent). Community day schools enroll the lowest percentage of students for at least 90 days-34 percent. These data clearly illustrate the short-term nature of alternative school participation.

Dropout Data Raise Questions

Alternative schools often enroll students who are at risk of dropping out of school. Given the at-risk population alternative schools tend to enroll, it seems reasonable to expect these programs would report relatively high dropout rates. An examination of the CDE dropout data for alternative schools reveals several interesting findings. First, the data confirm that dropout rates in alternative schools are significantly higher than regular high schools. Reported dropouts from alternative schools accounted for one-quarter of all high school dropouts in 2004-05, and dropout rates in alternative schools are at least two and one-half times higher than the statewide dropout rate. Thus, despite their attempts to keep students in school, alternative schools represent a place where many students exit the education system.

Second, the one-year dropout rates reported by the three alternative schools are dramatically different. As shown in Figure 5, continuation schools report that more than 10 percent of their total annual enrollment dropped out during 2004-05, whereas community day and community schools reported dropout rates of about 4 percent.

The dropout data on community day and community schools are difficult to reconcile with the fact that these schools often enroll students with the most significant behavioral problems. In fact, the reported dropout rates from these two schools is only slightly higher than the 3.1 percent statewide dropout rate reported for all high school students in 2004-05. As a result, we are concerned that these data do not accurately describe the dropout problem in these schools.

The temporary nature of most community day and community schools may explain their low reported dropout rates. According to local administrators, a student who drops out of one of these two schools may be referred back to the student’s home district due to failure to attend school. In this event, a student would not be identified as a dropout from the alternative school, and the district (or regular high school) would be responsible for getting the student to return to school.

Similar Data on Independent Study Is Not Available

Unfortunately, CDE data do not permit an analysis of enrollments and dropouts for students in independent study. As discussed in Chapter 1, districts determine which schools independent study students attend. As a consequence, data on independent study students are included with all other students at these schools-even though independent study students’ experience is considerably different from other students.

In October 2004, almost 80,000 high school students were enrolled full-time in independent study. Unfortunately, data are not available on the proportion of this group that would be considered at risk of falling behind academically and dropping out. District data show that 90 percent of these students “attended” one of three types of schools-regular high schools, district magnet schools, or charter schools. Community and continuation schools account for the remaining 10 percent of independent study students.

The community school data provide a glimpse of how independent study is sometimes used for struggling students. About 35 percent of community school students were enrolled in independent study. In general, community schools are believed to enroll students with the most severe behavioral problems. Often, these students also perform at levels far below state standards. While many educators question the effectiveness of independent study for these types of students, community schools nonetheless often use this approach.

District Use of

Alternative Programs

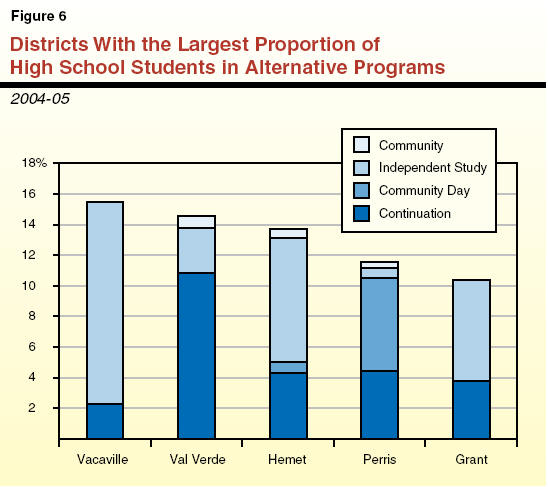

Our examination of the use of alternative programs shows widely different levels and patterns of use by districts. Figure 6 shows alternative school attendance in districts with more than 4,000 high school students that enroll the highest proportion of students in alternative programs. (We excluded smaller districts because relatively small numbers of students in alternative programs can represent a large share of total students.) We used attendance (rather than enrollment) to show independent study in a comparable way to the alternative schools. Since CDE does not collect attendance by grade, we used total high school enrollments to calculate the proportion of high school students in each of the alternative programs.

Of the larger districts, those with the highest proportion of student attendance in alternative programs all claimed more than 10 percent of their students in one of the four programs. This compares to an average of 5.7 percent of district attendance for all districts statewide.

As the figure shows, districts tend to use one or two options most frequently, with the other programs playing a relatively small role. In Vacaville, Hemet, and Grant districts, for instance, independent study is the most commonly used option. Val Verde, on the other hand, uses its continuation school as its primary option. Only Hemet and Perris use all four alternative programs-albeit in quite different proportions.

Community schools account for a small share of the alternative school attendance in these five districts. The data in Figure 6, however, represent only the less-severe students in these schools because CDE collects the district of attendance for these students. For the more severe students, CDE does not collect the district of attendance.

Conclusion

Data reviewed in this chapter reveal the limits of the state’s information on alternative programs. The October enrollment data tend to understate the size of alternative program enrollments-twice as many students attend a continuation, community day, or community school as the fall numbers suggest. In addition, the dropout data reported by community day and community schools raise significant questions about whether a large number of students are “falling through the cracks” of the data reporting system. For independent study, data problems preclude any statewide analysis of its use for at-risk students.

The data, however, allow several important conclusions about continuation, community day, and community schools. First, many students enroll in these programs each year-10 percent to 15 percent of high school students. This represents a much larger proportion of students than is reflected in the October data, and raises the possibility that a considerable proportion of students enroll in an alternative school during their four years in high school.

Second, students generally stay at alternative schools for a relatively short time. Only at continuation schools did more than one-half of all students remain at the school for at least 90 days. As a result, turnover of the student body at community and community day schools is very high. Third, alternative schools represent a place students often exit the education system. More than 25 percent of all reported high school dropouts leave one of the three types of alternative schools.

Data on district use of alternative programs reveal significant local differences in the use of the four programs. Some districts use the options extensively while others use them sparingly. Some districts offer one or two of the alternatives, others use all four. In the next chapter, we turn to research to develop a better understanding of the roles alternative programs play for districts, high schools, and students.

Chapter 3: A Perspective on

Alternative Schools and Programs

Research on effective alternative programs in California or other states is almost nonexistent. We were unable to find program evaluations that would help policymakers understand how well the different alternative programs work for the major subgroups of students who enroll in these schools.

Understanding Alternative Schools

There is one resource, however, that delves deeply into alternative program issues-Last Chance High School: How Girls and Boys Drop In and Out of Alternative Schools, by Dierdre Kelly. Published in 1993, the book examines one continuation school in the Bay Area from a variety of different perspectives. Its analysis is dated in some respects-at that time, students did not have to pass the California High School Exit Examination (CAHSEE) to graduate from high school, and school and district accountability systems were not in place. Nevertheless, the book provides insight into the forces and issues that alternatives must address in educating at-risk students. We discussed the book’s findings with program experts and local educators and found that alternative programs still wrestle with the same issues that Kelly describes in her book-often times with similar successes and failures.

In this chapter, we review four issues discussed in the book that apply to all alternative programs, not just continuation schools. These issues are (1) the institutional role alternative programs play within the district, (2) the goals of alternative schools, (3) educational standards of alternative schools, and (4) the system of alternatives within districts.

Institutional Role of the Programs

Alternative programs operate within a district context that reflects the attitudes of district officials and high school teachers and administrators about how to deal with students who create challenges-academic or behavioral-for the comprehensive high school. These attitudes shape the role of alternative programs within districts, and directly affect the performance of the alternatives. Kelly identifies three institutional responses that characterizes a district’s focus on meeting the educational needs of at-risk students.

Safety Net Programs. These districts view alternative programs as an educational setting that can help students who are not well-served by large, inflexible, comprehensive high schools. A safety net program, therefore, is “geared to meet the intellectual and social needs of those that the mainstream schools cannot or will not help.” The ultimate characteristic of a safety net is that it “meets with some measure of success in reengaging students.”

Safety Valve Programs. These districts focus on the needs of the comprehensive high school and use alternative programs as a place to send students the high school no longer wants. Such a program “provides a mechanism to rid mainstream schools of failures and misfits without holding school administrators fully accountable for the consequences.” While safety valve schools are best characterized as struggling programs, they are able to meet some student needs through the efforts of educators working in the alternative programs.

Kelly’s continuation school, for instance, struggled under the district’s policy that allowed the comprehensive high schools to determine referrals to the continuation school. The alternative school had little voice in the referral decision even when the school expressed strong concern “about the wisdom of a particular transfer.” In addition, because it was the only alternative school in the district, the continuation school received students who faced a variety of problems-including students with problems the school probably would be unable to address.

Cooling-Out Programs. These are districts that focus on the needs of the regular high school but operate neglected and ineffective alternative programs. Cooling out programs provide “a situation of structured failure” that undermines student aspirations and sense of academic potential. In the worst cases, the mismatch between program design and student needs is significant, and results in a large number of dropouts. Students who were unsuccessful at Kelly’s school, for example, were referred to adult education or independent study. There were no other options in the district, and most students were not given the choice to return to the regular high school. Referral to adult education or independent study did not prove to be an effective setting for these students.

Other Institutional Roles. Kelly also cites other roles for the alternative program within the district. For instance, the district used the continuation school as a place to train high school administrators and to punish poor performance by high school principals. This led to rapid turnover of the program’s administrators. The program also appeared to attract “disengaged” teachers, who were “among the worst teachers” in the district.

Goal of the Alternative School

Alternative programs often enroll students who face several different problems. Kelly cites two general approaches used by alternative schools.

Short Term (Fix the Student). Short-term programs focus on behavior modification-correcting student behavior patterns that result in educational failure or disruptive behavior in or out of school. Typically, these programs enroll students for about one semester, then students return to the comprehensive high school. Short-term programs often emphasize individual counseling and “credit recovery”-an instructional approach that allows students to earn course credits rapidly-to help students address behavior issues and get back on track academically. Community and community day schools typically are designed as short-term programs.

Long Term (Fix the School). Long-term programs recognize that many students achieve at higher levels in a different educational setting than the comprehensive high school. Continuation schools, for instance, are usually designed as long-term options that emphasize smaller class size and a more-relaxed relationship between students and teachers.

As the primary option in the district, Kelly’s continuation school offered features from both approaches. Counseling and credit recovery, for instance, were a prominent aspect of the services provided to students. This combination was dictated by the wide range of personal issues students brought to the school and the fact that most students arrived at the school after falling behind academically in the regular high school.

Educational Standards

The curriculum at the Last Chance High School generally was remedial-not surprising, perhaps, for a school with students who were often far behind academically. For many students, however, educational standards were defined more by process than by what students actually learned. Classes at Kelly’s school “put a premium on attendance, punctuality, and productivity rather than on academic content.” There were no school or district standards that students were required to meet to receive credit for a course. “Earning credit (based largely on attendance) as opposed to learning became the students’ overriding goal.”

Kelly suggests the district failed to provide a clear structure to guide program decisions. As a result, teachers and administrators at the Last Chance High School had considerable latitude over the design and operation of the school. This flexibility often meant that teachers were on their own to best determine how to meet student needs. Grading policies-awarding credits-was left to the individual teacher. Methods of instruction-lecture, small group work, or individual instruction-also was largely influenced by teacher preference. Kelly concludes that, without more structure, the school’s “goals seemed diffuse at best.”

The consequence of teacher-awarded credits was a phenomenon Kelly calls “push-throughs.” These unmotivated students generally attended regularly but did as little work as possible to obtain credits. In their desire to help students graduate, teachers essentially “pushed-through” this group of students by giving them credit for substandard work. Students acknowledged they were asked to do less: two-thirds of students surveyed felt classes at the continuation school were easier than at the regular high school.

The System of Alternatives

The system of alternatives described by Kelly is similar to the system present in many districts today: continuation school and independent study (or adult education) were the options available to students. In Kelly’s district, the continuation school was the first alternative. Students who were successful in improving grades and behavior could return to the comprehensive high school. Students who violated the continuation school’s attendance policies or whose behavior did not improve were transferred to independent study or adult education.

Less than 5 percent of students at Kelly’s school returned to the comprehensive high school. Returning often was motivated by the desire to graduate from the more prestigious comprehensive school. Many students who could have returned to the regular high school stayed at the continuation school, in part, because the work was easier.

On the other hand, more than one-half of all students sent to the continuation school eventually were referred to independent study or adult education. The school felt pressure to transfer students out of the school to make room for other students that the comprehensive high school wanted to send. Transfer out of the school also was used as a threat to induce better performance from students.

Long-Term Perspective Needed to Track Student Impact

Because of the turnover of students in these programs, measuring the quality of alternative programs requires following individual students over relatively long periods of time. To understand the performance of the Last Chance continuation school, Kelly tracked all of the school’s students who entered high school in 1985. Kelly tracked each student’s progress through June 1990 (to include students that needed an extra year of school to graduate).

Gauging the success of the school depended on how it was defined. For students at Kelly’s continuation school who did not transfer to another school, about 70 percent graduated and about 30 percent dropped out. Since the continuation school was the last school attended for only about one-third of all students attending the school, however, the 70 percent graduation rate reflects the experience of a relatively small group of continuation school students.

Including all students in the class of 1989 who attended the continuation school at some point yields a dramatically lower success rate. About 30 percent of the students eventually graduated and almost 60 percent dropped out. Of the remaining students, about 3 percent were still enrolled in school in June 1990 and about 9 percent had moved or transferred to a school in another district.

Kelly’s research also shows that students were unlikely to succeed in independent study or adult education. More than 90 percent of students referred to adult education, for example, eventually dropped out. According to one teacher at the school, “it is a fairly small group of people who are smart enough, motivated enough, and goal-oriented enough to benefit” from the individualized instruction provided through adult education or independent study. “Explained one teacher: There is no monitoring once they are at adult ed. It’s really the end. They leave saying they’ll make it there, but 99 percent won’t. We say ‘Yeah, good luck’-sending them out feeling good. But we know they won’t make it.”

Conclusion

Last Chance High School paints a picture of concerned teachers and administrators trying to help a group of students that the high schools no longer wanted. For a small group of students, the school was a good fit. But for many students, the school was attractive only because it required less work and fewer hours of class.

In the next chapter, we discuss the findings of our site visits and discussions with local alternative program administrators. These findings show that many of the problems experienced by Kelly’s continuation school are present in today’s programs.

Chapter 4: Evidence on the Quality of

Alternative Programs

In preparing this report, we visited a cross-section of programs around the state. These programs were selected based on a review of data about the range of programs administered by districts and the proportion of students involved in alternative programs. We visited districts and programs in inner-city areas as well as those in outlying areas. We talked to county office and district administrators, principals, teachers and students.

The site visits confirmed much of Kelly’s analysis. We talked to many educators who were working hard to develop a range of options designed to meet student needs. We also talked to frustrated administrators who pointed out problems with their own district’s programs. In this chapter, we couch our observations in terms of the institutional roles these programs play-safety net (indicating responsive programs), safety valve (indicating a struggling program), and a cooling-out program (indicating a neglected program). Our observations do not allow us to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of the state’s alternative programs. Instead, we used the site visits to better understand the larger forces that affect the operation of these programs.

Attributes of Safety Net Programs

We visited several districts that placed a high priority on creating effective options for at-risk students. Programs in these districts were characterized by an array of services or options that were established in response to the specific needs of students attending the school. Other positive signs include:

- Programs That Exceed State Minimums.

We visited two continuation schools that provide a six-hour school day for students-twice the length that is required in state law. In these cases, districts foot the bill for the additional costs of these full-day programs.

- Long-Term Options With a Strong Vocational Emphasis.

One district was developing a vocational component in its continuation school, with strong connections to regional vocational education programs and the community college.

- A Wide Array of Social, Health, and Family Services.

A charter alternative school we visited worked closely with other local agencies to provide on-site services for students. The school also was unique in the close working relationship it cultivated with the students’ parents.

- Standardized Assessments to Monitor Student Progress, Maintain High Standards. One district required alternative school students to pass the same district-wide end-of-course assessments as students in the regular high school. Three districts also used “pre-post” tests to gauge how well students learned the material.

Administrators of responsive programs often credited the district superintendent with providing the impetus and support to improve the quality of services provided through the alternative programs. Administrators also described their alternative programs as a “work in progress,” and that their programs have changed significantly over the years. Because there are few regional or state resources for improving alternative programs, administrators were often “on their own” to develop effective programs.

Attributes of Safety Valve Programs

We also sited programs operating at state minimums-three-hour days for continuation schools and four hours for community schools. Credits were awarded based on the individual teacher’s assessment of work performed during class rather than district achievement standards. The programs offered few or no additional classes or services outside the four core academic areas, such as vocational education or health or social services. Other signs included:

- Need for Additional Options.

One district administrator acknowledged a need for better options for students under the age of 16 (that is, too young to be sent to a continuation school). Instead, the district sent the younger students to the community school, which he felt could not adequately meet the needs of these students.

- Using Community School In Lieu of District Alternatives.

One urban community school program we visited enrolled 4 percent of

all high school students

and one-half of all alternative school enrollments in the county

in 2004-05. This translates into a rate that is about 10 times the statewide average proportion of students in community school. The size of the programs suggested that districts in the county preferred to send problem students to the community school rather than create “in-house” alternative programs. Almost 40 percent of these students, for example, fell into the category of community school students who had not committed serious offenses-students that districts in most other parts of the state address through district programs.

Perhaps the best way to describe these programs is that they respond to problems of students with the tools the state provides. The commitment did not exist in these areas, however, to extend the scope of services, lengthen the school day, or tailor services to better meet the needs of subgroups of students. In the case of the community school, the school seemed to have become a primary option for serving a wide range of students in the county, rather than a placement option for the most severe behavioral problems. This suggests that districts and high schools have shifted to the county office the challenge of working with more difficult students.

Attributes of a

Cooling-Out Program

We also talked to administrators who believed the district alternative programs had the attributes of a cooling-out program-a situation of structured failure. In these districts, independent study was a primary alternative for many students, rather than the second or third option. Other features of neglected programs include:

- Independent Study as a Permanent Placement for Low-Performing Students.

One district sent most “problem” students to independent study, even though most of these students were performing far below state standards. Since the district had almost no other alternative programs, these placements were considered permanent and no mechanism existed to help students return to the regular high school.

- Lack of Options Creates Waiting Lists.

One district developed a small community day school program primarily for students who were returning from state youth prisons or county correctional programs. The program frequently filled with referrals from the district, however, creating waiting lists for the students returning from jail. The administrator asked rhetorically: “What do we do with these students-tell them to go home and wait for an opening?”

- A Place to Send Ineffective Teachers.

According to one administrator, the district used the continuation school as a “dumping ground for tired or ineffective teachers.”

Alternative programs that exhibit the traits of a cooling-out program may be most charitably described as neglected. In the worst case, one district administrator admitted that the role of the alternative programs is to accommodate students that the high schools no longer want. This district provided few options and little effort was expended to track student progress in the programs or improve the quality of the programs over time.

Heavy use of independent study also i s characteristic of these programs. While independent study was used by virtually every district we visited, districts with well-developed alternatives referred students to independent study as the last option of several available to students. Despite all these districts referring at-risk students to independent study, no administrator believed that it was an appropriate setting for low-performing students-those scoring below the “basic” level on state tests, for instance-except in unusual situations.

Conclusion

The differences in district alternative programs are stark. It is important to recognize, however, that program attributes that appear responsive to student needs may not translate into effective education programs. A rich array of health and social services, for instance, may do little to help students be more successful in school. Educational effectiveness is the most important quality indicator for these programs.

Nevertheless, we were struck by how similar some of these schools were to the Last Chance High School. Our observations were reinforced by administrators who confirmed the shortcomings of their districts’ programs. These factors lead us to the conclusion that Kelly’s analysis still applies to alternative programs in California today.

Our site visits also highlight two problems with existing state programs. Most importantly, the design and operation of programs with attributes of safety net programs appears to require an unusual degree of local commitment. Administrators often cited strong support from the districts’ superintendent as a critical factor in developing responsive programs. Local administrators also agreed that state and federal accountability measures do not accurately capture the effectiveness of district alternative programs. These findings suggest the state needs to strengthen local accountability for effective alternative programs.

The state’s system of alternative programs also contributes to weak district programs. State support for alternative programs is available only when districts implement specific program models or refer students to county office programs. This encourages districts to rely on these programs rather than develop local programs that better fit the needs of students. In addition, the state programs create negative incentives that push districts to act in ways that may not be in the best interests of students. As discussed above, some continuation schools provide only the state-minimum three hours of class each day-one-half the amount that students in regular high schools receive. These problems suggest the state needs to thoroughly review existing alternative programs.

In the next two chapters, we examine these two problems in greater detail, and propose changes in state law that would reshape local incentives for addressing the needs of at-risk students.

Chapter 5:

Accountability For Alternative Programs

In this chapter, we examine the reasons why existing accountability programs are failing to adequately track alternative school performance. For the primary state and federal accountability measures, student mobility undermines the accuracy of school accountability scores-for both regular and alternative schools. Shortcomings of the state’s alternative school accountability system are more fundamental-the system fails to provide the most basic elements of an accountability system.

State and Federal

Accountability Programs

Alternative programs receive accountability “scores” under three programs, as follows:

- Federal Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP).

Under the federal Title 1 accountability program, school performance is measured by the percentage of students performing at the “proficient” level on state assessments. Each year, CDE establishes a minimum percentage of students that must perform at or above this level for a school to make AYP. Under the federal program, alternative schools are treated like all other schools.

- State Academic Performance Index (API). California also calculates a school API, which is similar to a weighted average of student scores on state tests. While state law exempts alternative programs from API-based rankings and interventions, the state uses API as an additional indicator of performance under the federal program. For this reason, alternative schools also receive an API, even though they are not responsible for making annual performance gains under the state program.

- State Alternative School Accountability Model (ASAM). State law requires CDE to develop an accountability program specifically for alternative schools-now known as ASAM. The ASAM requires districts to choose 3 performance measures from among 14 developed by CDE to determine the outcomes that are used to hold local alternative programs accountable. These measures include indicators on student attendance, suspensions, credits earned, graduation, and academic progress.

To work effectively, accountability systems must adhere to several design criteria. Input data, such as test scores, should include generally accepted measures of student educational performance. Data must be verifiable to insure accuracy. The system must protect school scores from manipulation by districts through local policies or actions. Finally, consequences must flow from inadequate performance. All three accountability systems violate at least one of these criteria in measuring alternative school performance.

Attendance Rule Undermines

API and AYP

Student mobility in alternative programs presents a difficult challenge for the main state and federal accountability programs. Specifically, how does the system account for the test scores of students who move between schools or districts during the school year? Take, for example, a student who begins attending a school the week before state tests are administered. Since the school had virtually no chance to influence the student’s education, it would be unfair to hold the school accountable for that student’s test results.

To address the issue of mobility, the state adopted a policy for the API and AYP that assigns a student’s accountability data (test scores, graduation status) to a school only when they attended the school for virtually the entire school year. The State Board defines the “entire school year” to mean a student who is enrolled at the school in October and at the time the Standardized Testing and Reporting (STAR) test is administered in the spring. Any student who transfers to another school after October is not counted towards either schools’ accountability score. Similarly, a student who transfers from one district to another (or to a county office program) after October is not counted towards either districts’ accountability score.

This attendance policy has two important effects. First, the high mobility of alternative school programs means that AYP and API scores fail to accurately measure the schools’ performance. Specifically, student mobility creates the following problems:

- Excludes Many Students From the School’s Scores.

Because many alternative school students stay for less than one semester, the schools’ API and AYP are based on a relatively small proportion of the students who attended the school during the year. In 2004-05, for instance, the attendance rule eliminated so many students from the alternative schools’ accountability scores that only 55 percent of alternative schools had enough students to receive an API .

- Long-Term Students May Not Be Representative.

It is unlikely that the few long-term students who do count towards the API and AYP are representative of

all the students-long-term and short-term-who attend the school each year.

- Year-to-Year Comparisons Not Meaningful. The mobility of alternative school students means that students who count towards the API in one year probably were not counted towards the API in the previous year, and thus a school’s scores for the two years are not really comparable.

For these reasons, the API and AYP measures do not accurately measure the levels or gains in student achievement at alternative schools.

Rule Allows Schools to

Avoid Accountability

The second major impact of the attendance rule is that it creates a way for regular high schools to avoid responsibility for the progress of low-performing students by referring them to an alternative school during the year. Since regular schools play a major role in the decision to refer students to alternative schools, it seems reasonable to hold high schools accountable for the progress of these students in their new school. The state’s attendance rule, however, releases districts from any accountability for that student.

This rule violates a basic accountability system criterion-schools and districts should not be able to manipulate accountability scores through local policies. The attendance rule allows-or even encourages-schools to avoid accountability for low-performing students by sending them to district alternatives. The same problem applies to districts for students who are sent during the school year to a community school-they do not count toward any school or district accountability score.

The impact on high school accountability can be significant. Using data from CDE’s web site, we examined the impact of the attendance rule on high school districts. To do this, we calculated the proportion of high school students in the district that were included in the district’s API but not the school’s API-signifying that the students moved between schools during the year. Of all high school districts, an average of 4 percent (with a range between 1 percent and 10 percent) of students changed schools within the district during the year. These figures do not include students referred to community schools.

While an average of 4 percent may seem like a small number, considerable variation in district exclusion rates exists. In some districts, virtually all students count towards school APIs, whereas in other districts, more than 10 percent of students are not counted. If the 10 percent of excluded students are primarily low-performing students, the attendance policy would have the effect of significantly improving these schools’ scores.

Omitting a significant proportion of low-performing students from school accountability scores clouds the comparability and meaning of the state and federal measures. A high school that works hard to meet the needs of all students would send fewer students to alternative programs-and thus, be accountable for their educational progress. Schools that use alternative programs as a “safety valve” or “cooling out stage” can artificially improve their accountability scores.

ASAM Fails to

Provide Accountability

Recognizing the challenge that student mobility presents for accountability programs, the state required CDE to develop ASAM to provide a measure of school performance and growth for alternative schools. Under the ASAM, schools pick 3 performance measures from a list of 14 possible measures. Each year, schools report their performance on these measures, but only for students who were enrolled in the school for at least 90 days.

Figure 7 displays the five most commonly used ASAM measures and the performance on each measure that CDE uses to define whether a school’s outcome is satisfactory or unsatisfactory. As the figure shows, credit completion and attendance are the two most commonly used performance measures, with about two-thirds of alternative schools choosing them. About one-quarter of schools use the other measures.

|

Figure 7

Commonly Used Accountability Indicators, 2004-05

Alternative School Accountability Model |

|

|

Proportion

of Schools |

School Scores |

|

Indicator |

Unsatisfactory Rate |

Growth Plan Needed |

Satisfactory Rate |

|

Credit completion rate |

69% |

0-67% |

68-81% |

82-100% |

|

Attendance rate |

67 |

0-65 |

66-83 |

84-100 |

|

Suspend/expel rate |

27 |

78-100 |

42-77 |

0-41 |

|

Graduation rate |

24 |

0-49 |

50-72 |

73-100 |

|

Reading improvement |

23 |

—a |

—a |

—a |

|

|

|

a

Performance levels had not been established for this

indicator in 2004-05. |

The figure also displays ASAM performance standards for the five measures. A “satisfactory” score represents CDE’s determination of the minimum adequate level of school performance. A school attendance rate of 85 percent, for instance, would be considered satisfactory, as it exceeds the minimum threshold of 84 percent for that indicator. An unsatisfactory rate, however, indicates a need for “immediate improvement” in the program. A school with an attendance rate below 66 percent would fall into this category. Schools with scores that fall between these two levels are advised to develop a “growth plan” to improve program outcomes.

Problems With ASAM

The ASAM violates several accountability criteria. In our view, these problems render it ineffective from an accountability perspective. Specific problems of ASAM are discussed further below.

Most Indicators Do Not Measure Educational Performance. Most ASAM measures are intermediate outcomes (such as credit completion and attendance)-necessary preconditions to creating a good learning environment. They do not, however, reflect learning outcomes. This violates the criterion that input data for accountability must be generally accepted measures of educational achievement.

Choice of Measures Thwarts School Comparisons. Allowing schools to choose their performance indicators under ASAM makes impossible any comparison of outcomes for similar programs. Accountability cannot be achieved without comparable data.

Some Indicators Are Not Comparable Across Districts. The credit completion rate, for instance, is the most commonly used ASAM indicator. As we discussed previously, however, districts have different policies for granting credits. Some use a district-wide examination to receive credit while others use teacher judgment. Without a statewide standard for granting credit, school outcomes on this measure are not comparable.

Performance Data Covers Less Than One-Half of Alternative School Students. By including only “long-term” students, ASAM excludes data on the majority of students attending alternative schools-those who were enrolled for less than 90 days. According to CDE, the 90-day rule gives programs time to get students on the road to learning before they are held accountable for student performance. This rule, however, frees programs from responsibility for results for students who attend less than 90 days. In fact, since some programs use 80-day semesters, it is possible for a school to have no long-term students.

School Performance on the Chosen Indicators Is Self-Reported. The department cannot verify district data. Reliable data is an essential ingredient to holding local education agencies accountable for their performance.

No Consequences for Poor Performance. The ASAM does not initiate district or program consequences for very low performance. Schools falling into the unsatisfactory performance levels are urged to take steps to improve, but there are no penalties for continued low performance.

Align ASAM With Accountability Criteria

Given these serious problems, we think ASAM needs a comprehensive overhaul so that it conforms with the accountability criteria discussed above. In our view, a redesign of ASAM needs to focus on a few student outcomes that (1) are consistent across all alternative schools and (2) can be captured with data that is accurate and consistent statewide. In addition, ASAM needs to create consequences for programs with very low student outcomes.

Recommendations

Tightening accountability for alternative programs will require some fairly substantial changes to existing programs. For API and AYP, the state needs to ensure that schools and districts cannot “select” which students they are accountable for. For ASAM, the state needs to establish a much more rigorous system of accountability.

Alter Attendance Rule to

Capture More Students

As discussed above, schools and districts can use alternative programs as a way to shift responsibility for at-risk students from regular high schools. Addressing this critical problem entails making high schools accountable for the achievement of students even after they are referred to an alternative program. To fix this problem, we recommend replacing the current “entire school year” rule with one that assigns accountability scores based on the each student’s “home” school. Our proposal would assign the test scores of alternative school students to the comprehensive high school of each alternative school student. By holding the regular high school accountable no matter where students are sent during the year (including district or county office alternative schools), this change would eliminate the ability at the local level to avoid accountability for at-risk students.

This change would alter the local relationships between comprehensive and alternative high schools. By holding the comprehensive school accountable for its students when they attend an alternative program, the accountability system would create a much stronger local incentive for the regular high schools to make appropriate referrals to alternative programs and ensure that alternative schools have the capacity to address student needs.

Revamp ASAM

Revamping ASAM requires defining the goals of alternative programs in a way that apply to all students who enroll in district programs. The state’s goals for students in alternative programs are identical to those for all students-to reach the highest possible levels of achievement and graduate from high school. Because many alternative program students perform far below state standards and are at risk of not graduating, accountability measures for these schools should focus on accelerating learning and graduating.

To be fair, ASAM does include indicators that measure these goals. Alternative schools may choose graduation rates or improvement in reading skills as ASAM indicators. Few schools make this choice. There are other problems, however, with these indicators. The state has no way to independently verify local performance data submitted for the two measures. Additionally, the state permits districts to use one of several pre-post tests, which means that the test results are not comparable across all programs.

Measures of Short-Term Success. Because alternative programs often are designed as short-term interventions, ASAM should include measures of short-run success-outcomes that can be evaluated every three to six months. State assessments do not provide a good measure of short-term learning gains. Local tests, such as district quarterly assessments or district end-of-course tests would not be comparable. In our view, a state-developed pre-post test that is aligned to state standards represents the best solution. While the cost of developing such an assessment would be considerable (up to $1 million), the state could reduce this cost by using questions developed for STAR and CAHSEE that were no longer in use. The alternative to a state-developed test would require CDE to choose a commercially available pre-post test for ASAM. According to CDE, available commercial tests are only partially aligned with state standards.

We also recommend ASAM include a short-term measure of whether a student is still in school. One of the core missions of alternative schools is to reengage students so they complete high school. Thus, our second short-term outcome would assess whether students were still enrolled in school three and six months after enrolling in an alternative program.

Longer-Term Performance Measures. Measures of more sustained success also are needed. Successful short-term programs may make little difference if students are returned to a long-term educational setting that is not designed to meet their needs. In our view, the components of the API-progress on STAR and CAHSEE and graduation rates-represent a good measure of the longer-term outcomes for alternative school students. Because of their mobility, however, any longer-term measure would need to track individual student success on these outcomes over time.

We recommend, therefore, that ASAM include an alternate API that measures student-level growth on state assessments over time. The alternate API would track student progress by comparing each student’s test scores in the year before they attended an alternative school or program with their score in the year they attended an alternative.

We see several benefits from a longer-term, student-level API. First, it measures what we consider are the most important outcomes of any educational program-student achievement. The alternate API would hold alternative programs responsible for preparing students to make progress towards this goal. Second, the measure would encourage alternative programs to work closely with regular high schools and districts to ensure its students are placed in a long-term setting where they can be most successful. Third, it provides critical information for students, parents, and the public to gauge how well the district serves at-risk students.

Deem Independent Study

Programs a “School”

Strengthening accountability for alternative schools would not necessarily address the use of independent study as a primary option for at-risk students since the program is not considered a school in most districts. As discussed earlier, districts house independent study programs at various sites. As a consequence, data are not available to understand how this subset of students fare educationally.

In our view, one remedy for this problem is to deem district independent study programs a school for the purposes of ASAM. This proposal would not require districts to actually create an independent study school. Instead, the state would simply aggregate the relevant test score data for all students in the program in each district. Under our proposal, the state would calculate an API and our recommended alternate API for full-time independent study high school students for each district. This would highlight the performance of independent study by providing new data on students in these programs.

Several objections to this proposal were raised in our discussions with educators. Some point out that some independent study programs may not fit the definition of an “alternative” school because they primarily enroll high-performing students. Others note that independent study is not a school, but one of many different types of instructional programs administered by districts.

We do not think these objections outweigh the need for better data on student success in independent study. At least 4 percent of all high school students are served through independent study, yet the state has no data to understand how these students fare educationally. Therefore, we think the Legislature should begin by taking a broad look at the effectiveness of the instructional approach.

The concern that independent study is not a school but a program takes too narrow a view of what constitutes a school. From an accountability perspective, a school is not a physical space where students congregate to learn. Instead, a school represents the level of local accountability that is closest to the individual student. For independent study students, the place they meet with teachers each week does not capture the fundamentally different educational program they receive compared to students who are physically present in classrooms each day. In fact, we think independent study represents a greater departure from the regular classroom experience than any of the existing alternative schools.

Therefore, we recommend the Legislature amend ASAM so that district independent study programs provide district-level data on the success of students in these programs.

Implementation Issues

Would Need to Be Addressed

Our recommendations would present new implementation issues for CDE. Specifically, our accountability proposals require the capacity to track individual student scores over time regardless of where the student attended school. In addition, new pre-post tests would be required and ways to collect this short-term data would need to be developed. We briefly discuss these issues below.

Longitudinal Student Data. The state currently does not have the capacity to track individual students over the four years of high school. It is developing such a data system as part of the California Pupil Assessment Data System (CALPADS). Student identifiers have been assigned to all students, and these identifiers now allow individual student test scores on STAR and CAHSEE to be tracked over time. By the time CALPADS is operational (2008-09), the state will have three years of STAR and CAHSEE data that could be linked longitudinally to calculate our recommended alternate API. We also think CALPADS could be used to collect three- and six-month dropout data that are part of our suggested short-term measures.

With the implementation of the student identifiers, the data are already being collected that would allow CDE to implement our recommendations over the next several years. We suggest, therefore, the Legislature require the State Board to implement our recommended changes beginning with the 2006-07 STAR scores. We also recommend giving the board the authority to phase in these changes over time so that school and district scores would be based on our recommendation in 2008-09.

Annual Student Progress. Our recommendations for long-term ASAM performance measures would require CDE to develop a way to measure student gains on STAR tests year to year. The STAR scores were not designed to ensure that the basic or proficient levels describe the same level of mastery in each grade. As a result, there is no way to interpret longitudinal student scores to determine whether gains or losses on the test are meaningful.

There are several ways to solve this problem. One would require a substantial redesign of STAR tests to create a “vertical scale” for the tests. This would provide a methodological framework to establish performance levels that mean the same thing in each grade. A vertical scale creates a way to easily calculate student growth from year to year relative to the state’s performance standards.

A second option would require CDE to calculate the “average gains” that students actually achieved from one year to the next. This would involve a relatively simple calculation of the average change in test scores from year to year. The measure would establish a benchmark for determining whether the progress of an individual student is greater or less than the average. Average gains could be calculated for each proficiency level and other major subgroups of students.

It is important to note that average gains would provide a relative benchmark for comparing individual gains in STAR scores. The measure would not necessarily provide any indication of the progress students were making in attaining a proficient level of achievement. Instead, it would establish a metric for evaluating individual gains compared to the gains made by similar groups of students. Only with a vertically scaled test can progress be measured in terms of proficiency. Thus, in the long run, we think a vertically scaled test is desirable.

We recommend that the Legislature begin with the average gains approach, as it could be implemented relatively quickly and at low cost. We also recommend requiring CDE to contract out for a report to the Legislature on the feasibility and costs of vertically scaling STAR tests. Technical experts are divided on the question of how best to provide comparability between grades in these statewide tests. We think the Legislature would be best served by commissioning a panel of assessment experts to provide the state with the available options and a recommendation for how to proceed in this area.

Over the long run, we think the state’s assessment and accountability system must be vertically scaled so that annual student-level gains in achievement can be measured. This requires a significant upgrade to the state’s annual test, which would take a number of years to accomplish. As a result, we recommend the Legislature begin the long-term improvement process now. In the meantime, the state could use the average gains methodology for ASAM. This would allow the state to revamp ASAM quickly and give CDE experience in the challenges of using individual student gains in an accountability system.

Administration of Pre-Post Tests. The state has several options for scoring and collecting the pre-post test results that are part of our suggested short-term performance outcomes. These tests could be shipped to a central scoring facility operated by a contractor, as is currently done for the other state assessments. The contractor would send the scores to the school and the state. Alternately, local school personnel could score the tests and transmit the score data to the state periodically. Site scoring is currently the policy in New York State for its statewide tests. This has the added value of providing instant feedback to the school on each student’s progress and informs teachers of students’ strengths and weaknesses. New York conducts random audits of school scoring and investigates unusual school-level gains or declines as a way of ensuring the integrity of the scoring process.