January 2007

California Travels: Financing Our Transportation

Introduction

In the past year, transportation has been a central issue in the

discussions on the condition of the state’s infrastructure. About

60 percent of Californians view traffic congestion as a major problem.

This dissatisfaction is probably because the state’s transportation

capacity has not kept pace with growth in population and travel demand.

Even with the funding provided by the Traffic Congestion Relief Act

(2000) and Proposition 42 (2002), many feel that the state’s

transportation system suffers from underinvestment. In November 2006,

voters approved two measures to increase the state’s investment in

transportation: Proposition 1A to enhance the reliability of certain

funds and Proposition 1B to provide a one-time infusion of $20 billion

in bond revenues for transportation.

These measures will help to improve the state’s transportation

infrastructure. Nonetheless, issues remain regarding how the state can

meet transportation demands on an ongoing basis. For instance, the

state’s highways and roads require increasing maintenance and

rehabilitation. Additionally, there are emerging issues, such as goods

movement and transportation security, which the state is just beginning

to address.

What is being done to address these problems? How should the state

ensure Proposition 1B funds effectively address congestion problems and

provide mobility to facilitate the state’s growing economy? What other

fund sources are available for transportation? How are these funds

distributed? This publication seeks to answer these and other related

questions in an effort to help those interested in finding solutions to

our transportation challenges.

Contents

Traveling

in California: Trends and Mobility

Transportation Revenues and

Expenditures

The Transportation System: How

Decisions Are Made

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Acronyms and Definitions

Traveling in California: Trends and Mobility

Travel Increasing Steadily…

- Demand for Highway Travel

Outpaced Population Growth. From 1990 to 2003,

California’s population increased by almost 21 percent.

Meanwhile, travel on the state highway system as measured by

vehicle-miles traveled (VMT) increased by 26 percent.

- Population Growth

Concentrated in Inland Areas. Population growth has

been uneven throughout the state. Between 1990 and 2003,

population grew most in the following regions: Sacramento

(50 percent), Bakersfield (47 percent), and Riverside-San

Bernardino (37 percent).

- Inland California Also Sees

Largest Gains in Total Driving. Beyond the state

highway system, demand for travel on local roads also

increased between 1990 and 2003 with the largest gains in

noncoastal regions. The regions with the largest increases

between 1990 and 2003 included: Fresno (61 percent),

Bakersfield (51 percent), and Riverside-San Bernardino

(45 percent).

… But Only Marginal Growth in State Highway Capacity

- Highway Lane-Miles

Increased Minimally. Between 1990 and 2003, highway

lane-miles only increased by about 3 percent. Today,

California has about 50,500 lane-miles of highways,

maintained and operated by the California Department of

Transportation (Caltrans). An additional 327,000 miles of

local roads are maintained and operated by local cities and

counties.

- Growth in Highway Capacity

Uneven Across State. The most significant expansion

in highway capacity over this period occurred in Orange, Los

Angeles and Ventura Counties, and the Bay Area. Capacity

increases were much less noticeable (or even nonexistent) in

other parts of the state.

- Carpool Lane-Miles

Increased Considerably. In 2000, the state highway

system included 925 miles of high occupancy vehicle (HOV)

lanes. As of 2005, California’s highway system included

1,268 miles of HOV lanes, a 37 percent increase. In most

cases, use of HOV lanes is restricted to vehicles with two

or more occupants in order to encourage carpooling. In some

cases, three or more occupants are required for vehicles

using HOV lanes.

- Toll Roads Remain a Small

Fraction of Highway System Capacity. There are about

120 miles of tolled transportation facilities in California.

This includes eight toll bridges in the Bay Area (seven are

state owned) and about 85 miles of toll roads in San Diego

and Orange Counties. Some of these facilities offer variable

tolls which set toll prices by level of congestion and time

of day.

California’s Roads More Crowded Than Other States

|

Rank

(2003) |

Urban

Area |

Miles

Driven Per Highway Lane-Mile |

|

1 |

Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa

Ana, CA |

23,248 |

|

2 |

Riverside-San Bernardino, CA |

21,429 |

|

3 |

San Francisco-Oakland, CA |

20,242 |

|

4 |

Chicago, IL-IN |

19,516 |

|

5 |

San Diego, CA |

19,460 |

|

6 |

Sacramento, CA |

19,303 |

|

7 |

Atlanta, GA |

19,077 |

|

8 |

Miami, FL |

19,057 |

|

9 |

Houston, TX |

18,970 |

|

10 |

Oxnard-Ventura, CA |

18,873 |

|

|

- Urban Roads Are Heavily

Used. California regions lead the nation with the

most crowded roads, measured in terms of the number of miles

driven on each lane-mile of highway. Los Angeles tops the

list, with Riverside-San Bernardino and San

Francisco-Oakland placing second and third.

- Trends of Road Usage in

Urban Areas. While Los Angeles has the nation’s most

crowded roads, other California regions are catching up.

Between 1990 and 2003, miles driven per highway lane-mile

increased considerably in Sacramento (35 percent),

Riverside-San Bernardino (28 percent), and Oxnard-Ventura

(27 percent).

- Supply Has Not Kept Pace

With Demand. One reason why California’s roads are

more crowded than those in the rest of the country is that

the state’s transportation infrastructure has not expanded

enough to keep pace with growth in travel demand (measured

in VMT).

Congestion Paid for in Delay, Fuel, and Excess Emissions

- Hours of Delay Have Risen.

Because of the imbalance between road supply and

travel demand, delay on urban freeways has nearly doubled

from about 262,000 vehicle-hours per day in 1992 to 512,000

vehicle-hours per day in 2002.

- Increased Congestion.

In 2002, 43 percent of the state’s urban freeways

were congested. Congestion is defined as occurring when

vehicles are traveling at 35 miles per hour or less during

peak commute periods on a typical work day. This is up from

32 percent in 1992.

- Costs of Congestion.

Congestion on urban freeways costs Californians at least

$16 million per day (or $5.9 billion per year) in wasted

time and excess fuel.

- Environmental Impacts.

This delay also has negative environmental

consequences, resulting in an estimated 512 additional tons

of emissions per day.

Are Californians Really in Love With Their Cars?

- While the conventional wisdom is that Californians are

infatuated with their automobiles, some data suggest that

this is not the case.

- For instance, when compared to the average American,

Californians tend to drive fewer miles.

- Californians do have slightly more vehicles than the

average American.

Bus Riders Make Up the Bulk of Transit Ridership

2003-04

- Transit Ridership.

In 2003-04, almost 1.3 billion passenger trips were made on

various modes of transit, including bus, rail, and ferry.

- Most Transit Patrons Ride

the Bus. About 70 percent of these trips were on

buses. Most of the remaining trips (27 percent) were made on

commuter and urban (light) rail systems. Intercity rail,

paratransit, and ferry systems carried less than 3 percent

of all trips.

- Increasing Number of Trips

by Train. Since the late 1990s, the number of transit

trips made by rail has significantly increased. In 2003-04,

about 347 million trips were made by train compared to only

287 million in 1997-98.

- Bus Ridership Down.

In contrast to rail, the total number of annual bus trips in

California has actually declined slightly. In 2003-04,

881 million trips were made on buses, down from 889 million

in 1997-98.

- While Auto Travel Grows,

Transit Ridership Stagnates. While auto travel on

state highways has increased by 26 percent since 1990,

transit (bus and rail) ridership overall has experienced

almost no growth. Again, this is due to the slight drop in

bus trips (the mode representing the bulk of transit

ridership), offset by growth in other transit modes, such as

intercity, commuter, and urban rail which have experienced

considerable ridership growth.

Intercity Rail Ridership Grows, but So Do State’s Costs

- The state’s passenger rail system includes intercity

rail that serves trips between regions in California and to

other parts of the country.

- Currently, Amtrak operates all intercity rail service in

the state. The state funds service in three corridors:

-

Capitol Corridor serving San Jose, Oakland,

Davis, Sacramento, and Auburn.

-

Pacific Surfliner serving San Diego, Los Angeles,

Santa Barbara, and San Luis Obispo.

-

San Joaquin serving Oakland, Sacramento, Fresno,

and Bakersfield.

- Between 1994-95 and 2004-05, ridership on the three

corridors has nearly doubled from 2.3 million to 4.4 million

annual passengers, an average annual rate of 6.6 percent.

The Capitol Corridor has experienced the largest increase in

ridership, which resulted mainly from the expansion of

service in the number of daily round-trip trains available

to riders.

- State costs (funded mainly by the Public Transportation

Account) to operate and maintain intercity service nearly

doubled over that period from $55 million to almost

$100 million annually, an average annual growth rate of

5.8 percent.

Urban and Commuter Rail Ridership Concentrated in Bay Area

- Urban and commuter rail are the components of the

state’s passenger rail system that primarily serve local and

regional transportation needs.

- These services are generally planned and administered by

local or regional transportation agencies, with funding

provided by a combination of local, state, and federal

sources.

- The bulk of urban and commuter rail ridership has

historically been in the Bay Area. However, most of the

recent growth in rail ridership has been outside of the Bay

Area.

- Ridership gains since the late 1990s on rail systems in

the Los Angeles (73 percent) and Sacramento-San Joaquin

(42 percent) regions are at least partially attributable to

major system expansions over that period.

Transportation Revenues and Expenditures

Local Funds Account for Almost One-Half of Ongoing Funds for

Transportation

2005-06

Transportation in California is funded by a variety of state, local,

and federal fund sources. Together, these revenues provide roughly

$20 billion a year for transportation purposes.

State Funds

-

Ongoing state funds

consist primarily of the state excise tax on gasoline and

diesel fuels, weight fees, as well as most of the state

sales tax on motor fuels.

-

Additional state funding

sources can include bond revenues and appropriations from

the General Fund.

-

In 2005-06, state revenues

provided about 30 percent ($6.1 billion) of total funds for

transportation.

Local Funds

-

Local funds for

transportation are derived from a variety of revenue

sources. These sources include (but are not limited to) a

statewide 0.25 percent tax on the sale of all goods and

services, additional (optional) local sales taxes, property

taxes, and transit fares.

-

In 2005-06, we estimate

that local funds constituted 47 percent ($9.4 billion) of

all revenues for transportation.

Federal Funds

-

These funds are generally

apportioned to California based on the state’s contribution

of federal excise taxes on motor fuels to the federal

Highway Trust Fund.

-

In 2005-06, California

received about $4.6 billion in federal transportation funds.

This accounted for 23 percent of total funding to the

state’s transportation system.

Price of Motor Fuel Includes Taxes for Transportation

- A large portion of transportation revenues in California

are collected at the pump, with Californians paying the

following taxes:

- 18 cents in state

tax for each gallon of gasoline and diesel fuel

(generally referred to as the “gas” tax).

- 18.4 cents in federal

tax for each gallon of gasoline.

- 24.4 cents in federal

tax for each gallon of diesel fuel.

- 7.25 percent uniform

state and local

sales tax, plus optional local sales taxes for

transportation or other purposes varying by county. (The

statewide average sales tax level is approximately

7.9 percent once local optional taxes are considered.)

- The state also collects weight fees on commercial

vehicles (trucks) based on either the truck’s unladen weight

(for trucks lighter than 10,000 pounds) or its gross weight

(for trucks in excess of 10,000 pounds).

State Transportation Funding Comes Primarily From Fuel

Taxes. . .

2005-06

. . . And Goes Primarily for Highways

Key State Transportation Funding Accounts

State Highway Account (SHA)

- Revenues-state gas tax and weight fees.

- Expenditures-generally used for highway

maintenance and operation, highway rehabilitation and

reconstruction, and Caltrans administration. Can also be

used for capital improvements (highways and certain transit

facilities).

Transportation Investment Fund (TIF)

- Revenues-state sales tax on gasoline.

- Expenditures-provides funds directly for

local road improvements, as well as for capital projects

(highway and transit) selected by regionals and Caltrans in

the State Transportation Improvement Program. Also funds

traffic congestion relief projects and transit indirectly

through transfers to the TCRF and PTA (see below).

Traffic Congestion Relief Fund (TCRF)

- Revenues-state sales tax on gasoline

(from TIF).

- Expenditures-provides funds for 141

statutorily specified transportation projects.

Public Transportation Account (PTA)

- Revenues-state sales tax on diesel, and a

portion of state sales tax on gasoline including:

- Sales tax on 9 cents per gallon of

gasoline (referred to as Proposition 111 revenue).

- Net revenue from 4.75 percent sales tax

on gasoline in excess of 0.25 percent sales tax on all other

goods, over and above the Proposition 111 revenues (referred

to as spillover).

- A portion of state gasoline sales tax

revenue from TIF.

- Expenditures-provides funds for transit

capital improvement, as well as operating assistance for

local transit systems. Also funds capital improvement and

ongoing support of the state’s intercity rail program. Funds

are restricted to expenditures for transit and planning

only.

|

Use of Gas Tax and Weight Fees Is Restricted

- The State Constitution (Article XIX) restricts how state

gas tax and weight fee revenues are spent. These monies may

only be used to plan, construct, maintain, and operate

public streets and highways, as well as to plan, construct,

and maintain transit/rail tracks and related facilities

(such as stations). These revenues

cannot be used to

operate transit systems or to purchase rolling stock

(trains, buses, or ferries).

- In 2005-06, these sources provided about $4.3 billion,

including $3.4 billion from the gas tax. A portion of gas

tax revenues-roughly $1.1 billion in 2005-06-is allocated to

cities and counties to plan, construct, and maintain local

streets and roads.

- The remaining $3.2 billion state gas tax and weight fee

revenues, along with federal transportation funds, finance

various state highway purposes. Together, these revenues

totaled about $6 billion in 2005-06. Current law sets

priorities for expending these funds as follows:

- Highway maintenance and operations, and local

assistance.

- Highway rehabilitation and safety projects in the

State Highway Operations and Protection Program.

- Capital improvements (including capacity expansion

projects such as additional highway lanes and new

transit facilities) in the State Transportation

Improvement Program (STIP).

Sales Tax on Motor Fuel Used for Broad Range of

Transportation Purposes

Statewide, there is a uniform sales tax rate of 7.25 percent on most

purchases. Five percent of that rate goes to the state, with the

remainder dedicated to local uses. (Due to additional local optional

taxes, the average sales tax rate in California is closer to

7.9 percent.)

Sales Tax on Gasoline

- Before 2002, most revenues generated from the sales tax

on gasoline were deposited into the General Fund and used

for various nontransportation purposes. Only a small share

of state gasoline sales tax revenues (spillover and

Proposition 111 revenues) was used for transit purposes.

- Since 2002, Proposition 42 constitutionally requires

that the portion of gasoline sales tax revenues that

previously went to the General Fund be transferred to

transportation purposes. The funds can be used for a broad

range of projects-highways, streets and roads, and transit

(including rolling stock). After 2007-08, 40 percent of

these funds will be used for STIP projects, 40 percent will

be used for local street and road improvements, and

20 percent will go for transit purposes. (Through 2007-08, a

portion of the annual Proposition 42 transfer first will be

used to fund projects in the Traffic Congestion Relief

Program.)

- Proposition 42 allowed the transfer to be suspended

under certain conditions. This occurred in 2003-04 and

2004-05. Proposition 1A, passed in November 2006, limits

the conditions under which suspensions may occur.

- In 2005-06, Proposition 42 provided almost $1.4 billion

for transportation. Another $67 million in gasoline sales

tax revenues went to the PTA for transit purposes. In total,

gasoline sales tax revenues accounted for 23 percent of

state funds for transportation in 2005-06.

Sales Tax on Diesel

- Most of the revenues from the state’s portion of the

sales tax on diesel fuel (4.75 percent rate) go to the PTA

for transit purposes. This revenue, about $271 million in

2005-06, accounts for about 4 percent of state funds for

transportation. Revenues from the remaining 0.25 percent

rate are retained in the General Fund.

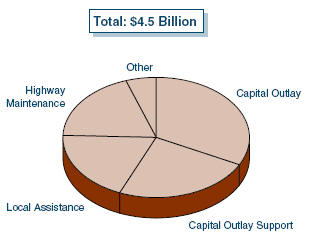

Most Highway Expenditures Are for Capital

Projects

2005-06

Most state highway program expenditures are for capital improvement

on the state and local road system, as well as to fund planning and

engineering activities supporting these improvements.

- Capital improvements-one-third

of Caltrans’ highway expenditures, funds highway and bridge

rehabilitation, expansion, right-of-way acquisition, and

safety improvements.

- Capital project support-24 percent

of highway expenditures, includes project design,

engineering, and environmental review activities.

- Local assistance-19 percent

of highway expenditures, primarily federal funds, the state

passes through to local agencies, which finance highway and

roadway improvements, bridge replacement and seismic

retrofit, as well as transit and nonmotorized (bicycle and

pedestrian) facility enhancements.

Remaining funds (one-quarter) are for noncapital uses:

- Highway maintenance-about

19 percent of spending, funds roadway repairs, landscaping,

and snow and litter removal.

- Other support

activities make up the

remaining 5 percent of highway expenditures. These include

spending for traffic management centers, new technology

research, legal costs, costs related to scheduling and

tracking projects, as well as various Caltrans

administrative expenses.

State Transit Expenditures Primarily for Local Assistance

2005-06

Most state transit expenditures provide assistance to local and

regional agencies to make capital improvements to rail and bus equipment

and facilities, and to support transit operations.

- Transit capital

improvements account for over one-half of these

expenditures (55 percent). These expenditures are in the

form of project grants to local jurisdictions.

- State Transit Assistance

constitutes about 29 percent of total state

expenditures for transit. These funds are distributed by

formula statewide to transit operators to support the

operations and maintenance of transit systems, and for

capital acquisition purposes.

- Support for intercity

passenger rail service accounts for about 15 percent

of total state transit expenditures.

- Transit planning and

administrative support make up 1 percent of state

expenditures for transit purposes.

State Bond Funds Will Provide Substantial One-Time Infusion

to Transportation

|

|

|

Proposition 1B Uses of Bond Funds |

|

(In

Millions) |

|

|

Amount |

|

Congestion Reductions, Highway and Local Road Improvements |

$11,250 |

|

Reduce congestion on state

highways and major access routes |

$4,500 |

|

Increase highways, roads, and

transit capacity |

2,000 |

|

Improve local roads capacity,

safety, and operations |

2,000 |

|

Enhance State Route 99

capacity, safety, and operations |

1,000 |

|

Provide grants for locally

funded transportation projects |

1,000 |

|

Rehabilitate and improve

operation of highways and roads |

750 |

|

Transit |

$4,000 |

|

Improve local rail and transit

capital |

$3,600 |

|

Improve intercity rail capital |

400 |

|

Goods Movement and Air Quality |

$3,200 |

|

Improve movement of goods on

highways, rail, and in ports |

$2,000 |

|

Reduce emissions from goods

movement activities |

1,000 |

|

Retrofit and replace school

buses |

200 |

|

Safety and Security |

$1,475 |

|

Improve transit system

security and disaster response |

$1,000 |

|

Improve railroad crossing

safety |

250 |

|

Seismically retrofit local

bridges and overpasses |

125 |

|

Improve security and disaster

planning in ports, harbors, and ferry facilities |

100 |

|

Total |

$19,925 |

- In November 2006, voters approved Proposition 1B, the

Highway Safety, Traffic Reduction, Air Quality, and Port

Security Bond Act of 2006. This act allows the state

to sell $20 billion in general obligation bonds to fund

transportation projects to relieve congestion, improve air

quality, and enhance the safety and security of the state’s

transportation system.

- These bond funds are one-time in nature. However, they

constitute a major infusion of state funds into the state’s

transportation system that will be spent over multiple

years.

About One-Half of Local Transportation Revenues

Comes From Sales Tax

2005-06

Collectively, local revenues generated an estimated $9.4 billion

from various sources in 2005-06 for transportation.

- Optional local sales taxes

represent an important source of local transportation

funding, generating approximately $3.1 billion annually.

These revenues fund improvements to highways, local streets

and roads, and transit systems.

- Quarter-percent tax on all

sales provided almost $1.4 billion in 2005-06. The

funds are generated under the Transportation Development Act

of 1971 and are deposited into the Local Transportation

Fund. They provide a major source of support for transit

operating assistance and capital projects.

- Transit fares

provided about $1.2 billion to local transit systems in

2005-06.

- Property tax and other

local funds collectively provided an estimated

$3.8 billion in 2005-06. These funds include property taxes,

developer fees, bond proceeds, as well as fines and

forfeitures. These funds are spent mainly on maintenance and

improvements of local streets and roads.

Optional Local Sales Taxes Contribute Significant

Transportation Funding

|

Agency |

Tax Rate (%) |

Year Established |

Year Expires |

Annual Revenue

(Millions) |

|

Permanent Measures |

|

|

|

|

BARTa |

0.5% |

1970 |

None |

$238 |

|

LACMTAb |

1.0 |

1981 and 1991 |

None |

1,300 |

|

San Mateo County |

0.5 |

1982 |

None |

61 |

|

Santa Clara VTAc |

0.5 |

1976 |

None |

150 |

|

Santa Cruz Metropolitan |

0.5 |

1979 |

None |

16 |

|

Subtotal |

|

|

|

($1,765) |

|

Fixed-Term

Measures |

|

|

|

|

Alameda |

0.5% |

2002 |

2022 |

$106 |

|

Contra Costa |

0.5 |

1989 |

2009 |

66 |

|

Fresno |

0.5 |

1987 |

2007 |

46 |

|

Imperial |

0.5 |

1990 |

2010 |

8 |

|

Marin |

0.5 |

2005 |

2025 |

20 |

|

Orange |

0.5 |

1991 |

2011 |

226 |

|

Riverside |

0.5 |

1989 |

2009 |

104 |

|

Sacramento |

0.5 |

1989 |

2009 |

93 |

|

San Bernardino |

0.5 |

1990 |

2010 |

104 |

|

San Diego |

0.5 |

1988 |

2008 |

213 |

|

San Francisco |

0.5 |

2004 |

2034 |

66 |

|

San Joaquin |

0.5 |

1991 |

2011 |

38 |

|

San Mateo |

0.5 |

1989 |

2009 |

61 |

|

Santa Barbara |

0.5 |

1990 |

2010 |

29 |

|

Santa Clara |

0.5 |

2006 |

2036 |

150 |

|

Sonoma |

0.25 |

2005 |

2025 |

23 |

|

Subtotal |

|

|

|

($1,353) |

|

Total |

|

|

|

$3,118 |

|

|

|

a

Bay Area Rapid Transit. |

|

b

Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation

Authority. |

|

c

Valley Transportation Authority. |

|

|

- History of Local Optional

Sales Taxes. Optional local sales taxes for

transportation originated in 1970, when the Legislature

authorized several counties served by the BART District to

impose a regional sales tax. Since 1987, state law has

authorized counties to impose special sales taxes for

transportation purposes, subject to voter approval.

Currently, a two-thirds vote is required for approval of any

local optional sales tax for transportation purposes.

- Current Use. In most

cases, counties proposing to impose local option sales taxes

must provide voters with an expenditure plan that specifies

how the funds would be used. As of 2006, 17 counties have

optional local sales taxes for transportation. (Starting in

early 2007, two additional counties-Madera and Tulare-will

levy a local sales tax for transportation.)

Fares and Local Funds Comprise the Bulk of

Transit Revenues

2003-04

(In Millions)

- Transit services are funded by a combination of

passenger fares and local, state, and federal funds.

- For the state’s largest transit operators, local funds

(such as local sales tax and property taxes) tend to provide

the largest source of revenues. For 2003-04, VTA reported

the highest proportion of total revenues met through local

funds (76 percent). At the low end, BART reported that local

funds constitute 53 percent of total revenues.

- Passenger fares also provide an important source of

revenues for operators. For instance, passenger fares made

up 47 percent of BART’s revenues in 2003-04. However,

passenger fares represented a much smaller proportion

(10 percent) of total revenues for VTA.

- The proportion of total revenues from state and federal

funds varied among transit operators. These revenues are

estimated to range from 0.2 percent of BART’s total revenues

to 18 percent of revenues for AC Transit.

Federal Transportation Act and Its Impact on California

|

|

|

The Safe, Accountable, Flexible,

Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for

Users (SAFETEA-LU) |

|

Major Provisions |

|

General: |

|

Maintains

overall structure of previous transportation act

(TEA-21), but increases emphasis on safety. |

|

Continues

TEA-21’s flexibility allowing up to 50 percent of

most program formula funds to be redirected. |

|

Funding Nationwide: |

|

Provides 42

percent increase in average annual funding over

TEA-21. Authorization of $241 billion for fiscal

years 2005 through 2009 includes $190 billion for

highways, $45 billion for transit, and $5.7 billion

for safety enhancements. |

|

Earmarks over

$26 billion worth of congressionally specified

projects, including $14.8 billion for High Priority

Projects and $1.8 billion for Projects of National

and Regional Significance. |

|

Highways: |

|

Guarantees

“donor states” a minimum of 90.5 percent return on

state fuel tax contributions in 2005 and 2006, 91.5

percent in 2007, and 92 percent in 2008 and 2009. |

|

Provides

incentives for private sector participation in

construction of major transportation facilities. |

|

Pilots

include: federal delegation of environmental review

responsibilities to states and toll programs on

interstate highways. |

|

Transit: |

|

Most

discretionary funds remain available for competitive

project applications. |

|

Provides

capital funding for smaller transit projects

requiring less than $75 million in federal funds. |

|

|

Federal Transportation Act Provides Funding Through 2009

|

|

|

Authorized Funding for California |

|

(In Billions) |

|

|

Formula |

Earmarks |

Totals |

|

Highway |

$15.4 |

$2.4 |

$17.8 |

|

Transit |

3.9 |

1.3 |

5.2 |

|

Safety |

0.4 |

— |

0.4 |

|

Totals |

$19.7 |

$3.7 |

$23.4 |

|

|

- Source of Federal Funds.

The federal government levies a fuel excise tax-18.4

cents per gallon of gasoline and 24.4 cents per gallon of

diesel. These revenues are deposited in the federal Highway

Trust Fund-the primary account for federal transportation

spending. Annually, California receives a share of these

funds via the federal transportation program (SAFETEA-LU),

which authorizes $241 billion to be invested in highways,

transit, and transportation safety projects nationwide from

2005 through 2009.

- Funding to State.

The federal act authorizes $23.4 billion for California

through 2009, including about $18 billion for highways, $5

billion for transit, and $452 million for safety

improvements. Roughly 15 percent of this funding ($3.7

billion) is earmarked for specific projects. For 2005-06,

federal funds provided about $4.6 billion for California’s

transportation system.

The Transportation System: How Decisions Are Made

|

|

|

The Key

Players: Who Decides What Gets Built and When? |

|

State |

|

Legislature |

·

Sets overall transportation policies, including

establishing revenue sources and expenditure

priorities.

·

Appropriates lump sum for capital improvements

through annual budget and provides oversight on

implementation of the state transportation program.

·

In general, delegates the authority to

select specific projects to Caltrans, regional and

local agencies, as well as CTC.

·

Occasionally designates transportation

projects statutorily. In 2000, selected 141 projects

to be funded through the Traffic Congestion Relief

Program. |

|

Department of Transportation (Caltrans): |

·

Implements the state transportation

program in general through 12 districts and

headquarters in Sacramento.

·

Owns, operates, maintains, and repairs

the state highway system.

·

Plans and designs capital improvement

projects on the state highway system.

·

Selects projects for the interregional

portion of the five-year State Transportation

Improvement Program (STIP).

·

In 2006-07, 22,352 authorized

positions in department. |

|

California Transportation Commission (CTC) |

·

Consists of nine members appointed by

the Governor.

·

Recommends policy and funding

priorities to the Legislature.

·

Adopts estimates (prepared by Caltrans)

of available transportation funds for capital

projects.

·

Reviews and adopts STIP and State

Highway Operation and Protection Program to ensure

compliance with statutory guidelines.

·

Allocates state and federal funds to

projects nominated by Caltrans and regional

agencies.

·

Provides oversight on Caltrans and

local project delivery. |

|

Regional |

|

Regional

Transportation Planning Agency (RTPA) |

·

Currently, there are 48 RTPAs

statewide.

·

Formed by specific legislation. These

RTPAs are usually in the form of council (or

association) of governments, and local

transportation commissions.

·

Administers state funds and allocates

federal and local funds to projects.

·

Selects projects for the regional

portion of the STIP. |

|

Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) |

·

Currently, there are 17 MPOs in

California.

·

Federally required planning bodies;

typically the same as an urban region’s RTPA.

·

Prepares the 20-year Regional

Transportation Plan and selects projects.

·

The Governor designates an MPO in

every urbanized area with a population over 50,000. |

|

Other |

|

Other

Players |

·

County transportation authorities

develop expenditure plans for voter-approved local

option sales tax measures and administer funds.

·

Federal transportation agencies—such

as the Federal Highway Administration and the

Federal Transit Administration—oversee the use of

federal transportation funds.

·

Environmental agencies at the local,

state, and federal level review transportation

projects and issue permits to ensure transportation

improvements comply with environmental laws.

·

Cities and counties set land-use

policy and nominate transportation projects for

funding by the RTPA.

·

Transit agencies—such as the Bay Area

Rapid Transit and Los Angeles County Metropolitan

Transportation Authority—nominate projects for

funding and deliver transportation services and

improvements. |

|

|

Four Major Programs Guide State Capital

Spending

Currently, there are four major programs which guide state capital

spending for transportation in California:

- The State Transportation

Improvement Program (STIP) funds new construction

projects that add capacity to the transportation system.

These projects include capital improvements to highways,

streets and roads, and transit systems. Funding comes from a

mix of the state gas tax and sales tax on motor fuels, as

well as federal funds. This program is ongoing.

- The State Highway

Operations and Protection Program (SHOPP) funds capital

projects to improve existing highways. Projects include

pavement rehabilitation (reconstruction), as well as

projects to enhance highway safety and operations. Funding

comes from state gas tax, truck weight fees, and federal

funds. This program is ongoing.

- The Traffic Congestion

Relief Program (TCRP) funds 141 capital projects

specified in the Traffic Congestion Relief Act of 2000 (AB

2928, Torlakson). The TCRP includes mainly highway and

transit projects located in urban areas. Funding comes

primarily from gasoline sales tax revenues provided each

year through 2007-08. However, TCRP will likely receive

revenues into the next decade from repayment of loans it

made to the General Fund in past years.

- Proposition 1B Bond Program

funds projects to relieve congestion, facilitate

goods movement, improve air quality, and enhance the safety

and security of the transportation system. Specific projects

have yet to be selected, but will include projects that add

capacity to highways and transit systems, improve major

trade infrastructure (including highways with high truck

volumes, ports, and freight rail lines), as well as enhance

the safety of existing transportation infrastructure. These

projects are to be funded by almost $20 billion in general

obligation bonds sold by the state.

Availability of Funds Determines What Gets Built and When in

the STIP

How Are State Transportation Dollars

Estimated?

-

Fund Estimate. Caltrans

estimates biennially all federal and state transportation

funds that would be available over a five-year period. These

funds include mainly revenues from state and federal excise

tax on motor fuels, sales tax on motor fuels, and truck

weight fees.

- The estimate projects

the amounts to be committed to various purposes over the

period. Priority is given to highway maintenance and

operations, local assistance, and SHOPP projects. Any

remaining funds would be available for STIP projects.

How Are STIP Funds Distributed?

How Are Regional Funds Programmed?

How Are Projects Chosen in the Regional

Program?

-

Projects are selected for

funding by RTPAs based on regional priorities, as defined in

20-year regional transportation plans. Projects are selected

from a large pool of projects proposed by cities, counties,

and transit agencies. The RTPAs then submit their respective

lists to CTC for approval.

- The CTC can either adopt or reject an individual RTIP in

its entirety, but cannot delete or add specific projects.

Together, the 48 regional proposals form the statewide RTIP.

How Are the Interregional Funds

Distributed?

Expenditures During the 2006 STIP Period

For the 2006 STIP period (from 2006-07 to 2010-11),

Caltrans estimates that available transportation funds total

$45 billion. (This estimate does not include bond funds available under

Proposition 1B.)

- Non-STIP

Expenditures. Most available funds will

not go to STIP projects (new construction). About $39 billion will

be spent on other priorities:

- About $18 billion for noncapital expenditures

(including highway maintenance and operations) and local

assistance.

- Almost $12 billion for SHOPP projects to

rehabilitate highways and improve highway safety and operations.

- About $9 billion for other purposes,

including operating assistance for local transit systems, local

streets and road improvements, TCRP projects, and the state’s

intercity rail program.

- STIP Expenditures.

About $5.9 billion-the remaining amount

after other requirements have been funded-will be available for new

construction projects.

- Historically, most of the funds available for

STIP projects came from the SHA (state gas tax and weight fees)

and federal funds. In recent years, however, growing highway

rehabilitation and maintenance expenditures have consumed an

increasing proportion of these revenues, leaving fewer funds for

STIP projects.

- For the 2006 STIP period, most of the funds

available for STIP projects will come from TIF and PTA

(primarily sales tax on motor fuels).

|

Most STIP Funds Used for Roads

2006 Through 2011

- Funding for Projects in the

2006 STIP. The 2006 STIP provides about $5.9 billion

over a five-year period for capital improvements. Of this

amount, 65 percent is for highways and roads, 29 percent is

for transit, and 6 percent is for transportation

enhancements (including roadway beautification, as well as

bicycle and pedestrian facilities).

- Many STIP Funds Are

Restricted to Specified Uses. Projects funded in STIP

are constrained by the types of funds available. For

instance, funds from PTA may only be used for transit

projects, whereas funds from TIF are more flexible in their

use. Thus, there could be a mismatch between available funds

and the projects proposed to be funded over a STIP period.

- For instance, there were considerably more highway

and road projects proposed in the 2006 STIP than dollars

available for these types of projects (TIF, SHA, and

federal funds). Because most of the funding available

for new projects was from PTA, the adopted 2006 STIP

includes additional funds only for transit projects.

- Funding Provided for

Discrete Project Development Phases. These phases

include engineering and design (known as capital outlay

support), environmental review, right-of-way acquisition,

and construction.

The SHOPP Includes Primarily Highway Pavement and Safety

Projects

2006 Through 2010

-

The SHOPP primarily

funds pavement rehabilitation and projects that improve

roadway safety. It also funds roadside preservation

(including rest areas and freeway plantings), operational

improvements (such as ramp metering), upkeep of facilities

(including office buildings and equipment shops),

construction of railroad grade crossings, and hazardous

waste mitigation.

- The SHOPP is based on a ten-year plan prepared by

Caltrans. Caltrans develops this plan by periodically

inspecting the state highway system to identify areas in

need of rehabilitation, safety, or operational improvements.

The SHOPP is updated every two years.

- Projects are selected by Caltrans based on statewide

need, rather than a geographic formula, such as percentage

of population or highway lane-miles. Available funds also

constrain the number of projects included in the four-year

SHOPP.

- For the four-year period from 2006 to 2010, CTC adopted

a SHOPP of about $7.9 billion. Most of this amount

($6.7 billion) has been programmed for specific projects.

(This amount does not include the support costs to design

and engineer projects.) The remainder is left unallocated

for unanticipated needs.

|

|

|

SHOPP and

STIP Allocations by County |

|

(In

Millions) |

|

|

SHOPP (2006-2010) |

STIP (2006-2011) |

|

Alameda |

$461 |

$152 |

|

Alpine |

7 |

29a |

|

Amador |

21 |

a |

|

Butte |

35 |

18 |

|

Calaveras |

26 |

a |

|

Colusa |

31 |

3 |

|

Contra Costa |

159 |

65 |

|

Del Norte |

46 |

2 |

|

El Dorado |

245 |

16 |

|

Fresno |

84 |

84 |

|

Glenn |

17 |

5 |

|

Humboldt |

138 |

27 |

|

Imperial |

36 |

46 |

|

Inyo |

34 |

55 |

|

Kern |

118 |

155 |

|

Kings |

62 |

18 |

|

Lake |

69 |

14 |

|

Lassen |

34 |

12 |

|

Los Angeles |

994 |

874 |

|

Madera |

20 |

9 |

|

Marin |

11 |

32 |

|

Mariposa |

2 |

4 |

|

Mendocino |

113 |

47 |

|

Merced |

137 |

12 |

|

Modoc |

— |

5 |

|

Mono |

18 |

31 |

|

Monterey |

81 |

97 |

|

Napa |

38 |

11 |

|

Nevada |

159 |

22 |

|

Orange |

231 |

327 |

|

Placer |

208 |

83 |

|

Plumas |

44 |

9 |

|

Riverside |

245 |

153 |

|

Sacramento |

137 |

72 |

|

San Benito |

2 |

1 |

|

San Bernardino |

639 |

287 |

|

San Diego |

219 |

174 |

|

San Francisco |

35 |

41 |

|

San Joaquin |

114 |

42 |

|

San Luis Obispo |

68 |

53 |

|

San Mateo |

175 |

78 |

|

Santa Barbara |

78 |

95 |

|

Santa Clara |

187 |

53 |

|

Santa Cruz |

42 |

28 |

|

Shasta |

286 |

30 |

|

Sierra |

— |

3 |

|

Siskiyou |

40 |

19 |

|

Solano |

237 |

60 |

|

Sonoma |

99 |

78 |

|

Stanislaus |

54 |

65 |

|

Sutter |

23 |

21 |

|

Tahoe RPA |

N/A |

3 |

|

Tehama |

101 |

8 |

|

Trinity |

13 |

17 |

|

Tulare |

43 |

53 |

|

Tuolumne |

24 |

6 |

|

Ventura |

62 |

78 |

|

Yolo |

95 |

25 |

|

Yuba |

13 |

7 |

|

Subtotals |

($6,710) |

($3,812) |

|

Interregional Program |

N/A |

1,361 |

|

Unallocated Funds |

1,185 |

730 |

|

Totals |

$7,895 |

$5,904 |

|

|

|

a

Shared by Amador, Alpine, and Calaveras Counties. |

|

|

- While STIP funds are distributed according to a formula

based on population and highway lane-miles, SHOPP funds are

distributed according to need.

- As a result, some counties-such as Marin and Orange-

receive substantially more STIP funds than SHOPP funds,

while the reverse is true for other counties, including

Nevada and Del Norte.

- Counties often have the opportunity to advance their

STIP funding. This means that counties can borrow from

future-year STIP shares in order to fund a project sooner.

Because some counties, like Fresno, advanced funds in prior

years, these counties will receive less new funding in the

2006 STIP than the formula would otherwise provide.

Traffic Congestion Relief Program: Projects

Defined by Statute

- Projects Defined by

Statute. The TCRP is a multiyear transportation

funding program. In 2000, the Traffic Congestion Relief Act

committed $4.9 billion (largely in gasoline sales tax

revenues) to fund 141 projects specified in statute. Because

TCRP projects are specified in statute, rather than

programmed by CTC, the project selection process for TCRP is

very different from STIP and SHOPP.

- Large Share of Funds for

Transit and Rail. Over one-half of TCRP funds

(62 percent) are provided for transit and rail projects.

Most of the remaining funds are for highway projects, with a

small share of funds dedicated to other purposes, including

local road enhancements, seismic retrofit, and air quality

improvement.

- Program Ends, but Projects

Not Yet Delivered. Due to the state’s fiscal

condition, many TCRP funds were loaned to the General Fund

during the early years of the program. Under current law,

most of these loans will be repaid to TCRP by June 30, 2016.

Because of these loans, as well as other delays related to

specific projects, many TCRP projects will not be delivered

until after 2010.

- Through 2005-06, 26 projects have been completed

which received about $300 million in TCRP funds. So far,

almost $1.7 billion (35 percent of the total funding

amount) has been expended on development of all TCRP

projects.

Proposition 1B: New Funding Programs Guide Project Selection

In 2006, voters approved Proposition 1B, which provides almost

$20 billion in general obligation bonds to fund a variety of

transportation purposes. These bond funds are subject to appropriation

by the Legislature before they can be expended.

From Planning to Construction: How a Project

Gets Built

In order to develop a transportation project from a concept-through

design, engineering, and construction-to a useable facility, a number of

steps have to be taken and requirements met. The key steps and processes

are highlighted below.

Long-Term Transportation Planning to

Identify Projects

-

Federal and state law

require that every region with a population of 50,000 or

more prepare and regularly update a 20-year Regional

Transportation Plan (RTP). This plan identifies the

transportation needs of the region based on projections of

growth and travel demand, coupled with projections of

estimated funding levels.

- Any project that is expected to have a negative air

quality impact must

be included in the RTP. This ensures that the

project’s air quality impact is considered in the evaluation

of the region’s ability to meet state and federal air

quality standards.

- The RTP must be approved by the Federal Highway

Administration (FHWA), the Federal Transit Administration,

and must be consistent with the State Implementation Plan

for air quality conformity with the federal Clean Air Act

before a project is eligible for federal funds.

Prepare

Initial Document

-

To begin a transportation

project, Caltrans prepares a project initiation document to

define the project and describe its cost, scope, and

schedule.

Secure Funding for Project

-

Once a project has been

included in the RTP, its sponsor (such as a city, county, or

transit agency) must secure funding for the project. Funding

may come from any combination of state, federal, local, or

private sources.

- For projects built with state funds, funding is

generally secured when a project is programmed in the STIP;

for projects built with federal funds, but no state funds,

projects must be included in the federal equivalent, known

as the Federal Transportation Improvement Program.

Environmental Review

-

Before extensive design or

construction can begin, the project must comply with state

and federal environmental laws. The two major laws affecting

transportation projects are the California Environmental

Quality Act and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

These laws require that various alternatives be examined in

order to meet the needs of the project while minimizing its

negative environmental impact.

- Typically, environmental review is the longest and most

unpredictable phase of the project delivery process. Project

evaluation and permit approval by as many as 15 to 20

agencies on certain projects takes considerable time.

- The federal act, SAFETEA-LU, allows five states,

including California, to takeover FHWA’s NEPA review duties

on a pilot basis. Chapter 31, Statutes of 2006 (AB 1039,

Nuñez) allows Caltrans to use this delegation of authority

through January 1, 2009. The law requires Caltrans to report

on the costs and time savings realized through the pilot, so

that California can assess the benefits of NEPA delegation.

Design

-

Since the passage of

Proposition 35 in 2000, both Caltrans and local

transportation entities have the authority to contract out

the design of transportation projects, including STIP

projects. Prior to 2000, the State Constitution required

that most state highway projects be designed by state staff.

- Although preliminary design must be done in order to

conduct environmental review, final design work is not

completed until the project has received environmental

approval by the various state and federal agencies.

Construction

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Implementing the Transportation Bond

In November 2006, voters approved Proposition 1B, which allows the

state to sell $20 billion in general obligation bonds to fund

transportation projects that relieve congestion, facilitate goods

movement, improve air quality, and enhance safety and security. These

bond funds, when appropriated by the Legislature, will be available for

expenditure over multiple years for a number of existing as well as new

transportation programs.

In order to achieve the objectives of Proposition 1B, the bond funds

should be allocated to effective projects that can be constructed and

open to users in a timely manner. We recommend that the Legislature take

the following actions relating to Proposition 1B implementation to

ensure that the bond act’s objectives are met.

Adopt Additional Project Eligibility,

Evaluation Criteria. Proposition 1B establishes a number of new

funding programs, but provides only general guidelines for the use of

the funds. This leaves fund recipients with broad discretion. For

example, in allocating $1 billion for Transit Security grants, the bond

act language is very open-ended-conceivably these funds could be used

either for projects that specifically address a security threat or for

projects that more generally increase a transit system’s capacity. Such

a lack of specificity may allow projects to be funded that do not best

align with state priorities. We think that the Legislature should adopt

additional project eligibility and evaluation criteria for five new

programs with funding totaling $5.1 billion. These include Trade

Corridors, Air Quality, Transit Security, State-Local Partnership, and

Port Security.

Ensure Timely Project Delivery.

Projects must be complete and open to users before offering any

mobility, air quality, or economic benefits. To create incentives for

timely delivery of projects and avoid bond funds remaining available

indefinitely for projects that show no signs of progressing (as has

occurred in the Traffic Congestion Relief Program [TCRP]), the

Legislature should adopt project delivery deadlines, as well as

mechanisms to remove funds from lagging projects so they can be

allocated elsewhere.

Provide Adequate Resources to Deliver

Projects, Including Increased Use of Contracting. Considerable

personnel resources will be necessary to plan and construct the

multitude of transportation projects funded by these bonds. Given

Caltrans’ crucial role in delivering bond-funded projects, the

department’s project delivery capacity will likely need to be expanded

significantly for a number of years. The Legislature should ensure that

Caltrans, in its annual budget request, has an adequate combination of

support resources-including both state staff and contracted

services-that would enable the department to provide timely delivery of

all transportation projects.

Provide Ongoing Program Oversight.

Transportation projects often take five or more years to plan and

construct. It is therefore important for the Legislature to monitor on

an ongoing basis how well the bond-funded programs are delivering

projects that cost-effectively relieve congestion and meet other

objectives. Given the number of programs and fund recipients, we

recommend that the Legislature designate one agency, such as California

Transportation Commission (CTC), to oversee the entire transportation

bond program and provide an annual report to the Legislature with

specific information, including progress in delivering projects on time

and on budget. We further recommend that the policy committees and

budget subcommittees of the Legislature hold periodic joint hearings in

which CTC, Caltrans, and other key implementing entities report on the

use of bond funds and the timeliness of project delivery.

Measures to Streamline and Enhance Project

Delivery

Expeditious delivery of transportation projects is important to meet

Californians’ increasing travel demand and to relieve congestion. The

administration should identify and implement measures to streamline

steps in the project development process, which may reduce state staff

workload and improve delivery times. There are also measures that we

recommend the Legislature adopt to expand the state’s capabilities to

deliver projects. Below, we list a few examples of various strategies.

Design-Build Contracting. The

design-build contracting method awards both the design and construction

of a project to a single entity. The use of design-build to construct

projects seeks to reduce project delivery times by integrating the

design and construction processes. Under SAFETEA-LU, virtually any

transportation project is eligible to be built using this method.

Current state law, however, authorizes the use of design-build only for

specific transportation projects (for example, I-405). Thus, Caltrans

has little experience using this contracting method. While there are

advantages to using design-build, including potential shortening of

project delivery time, there are also pitfalls to avoid.

- We recommend that the Legislature authorize a

design-build pilot program similar to that proposed by AB

143 (Nuñez) in 2006 and SB 56 (Runner) in 2007. Both bills

propose a demonstration program that allows Caltrans and

regional agencies to deliver a set number of projects using

design build. These bills also require that transportation

agencies report on their experiences so that the state can

use the information in deciding whether to pursue future

design-build projects.

Streamlining Environmental Review.

As environmental clearance is typically one of the longest and least

predictable phases of the delivery process, streamlining measures to

minimize redundant steps or uncertainty in the environmental review

phase may offer significant benefits.

- Chapter 31, Statutes of 2006 (AB 1039, Nuñez),

streamlines environmental review by exempting certain

earthquake safety projects from state reporting requirements

and permitting Caltrans to prepare one master environmental

impact report (EIR) for projects on Highway 99, rather than

multiple EIRs for projects along the corridor. The statute

also allows Caltrans to take over federal environmental

reporting duties on a pilot basis through January 1, 2009.

By allowing Caltrans to communicate directly to involved

federal agencies, rather than doing so indirectly via the

Federal Highway Administration staff, the pilot seeks to

reduce project delivery times.

- Caltrans estimates that per-project time-savings gained

from taking over federal reporting duties will range from a

few weeks on the simplest projects to over six months on

large projects requiring a federal EIR. If these estimates

hold, the Legislature may want to extend this pilot for

several more years, subject to federal approval. We further

recommend the Legislature direct Caltrans to identify

additional streamlining measures to improve delivery times

for specific bond-funded programs.

Increase Use of Contracting-Out for

Design Services. Under the State Constitution, Caltrans has the

authority to contract for design and engineering services. To date, the

department has annually contracted out about 10 percent of its design

and engineering work. As Caltrans becomes responsible for the timely

delivery of more projects under Proposition 1B, the department will

likely need a significantly higher level of support resources to deliver

these projects than it currently has. However, it will be difficult for

Caltrans to hire and train within a short time frame the necessary level

of state staff to handle the workload. In order for projects to be open

to users in a timely manner, we recommend the Legislature direct

Caltrans to expand its use of private consultants to deliver projects.

Leveraging Additional Transportation Dollars

While the transportation bond provides a substantial one-time

infusion of state funds for transportation, there is still a

substantial, ongoing funding shortfall in order to provide continuing

capital improvements to meet Californians’ travel demand. In our view,

the state should leverage other fund sources to supplement state

sources.

Public-Private Partnerships.

Public-private partnerships (P3) provide a means to generate private

investment for transportation facilities. These partnerships often take

the form of a state or local government entering into a lease agreement

with a private entity to design, construct, maintain, and operate a

facility for a period of time. The federal act encourages the use of

these partnerships to generate private sector investment in

transportation.

- Chapter 32, Statutes of 2006 (AB 1467, Nuñez), allows

Caltrans and regional agencies to pursue four P3 projects on

goods movement facilities. Because P3s may also work well

for other types of projects, for example highway toll

facilities, we recommend that the Legislature authorize P3

projects around the state on a broader range of facilities.

Encourage Local Investment. Most

urban counties have adopted local option sales taxes with revenues

dedicated to transportation. Because the benefits of transportation

investments are felt most at the local level, the state should encourage

more local investment.

- Proposition 1B provides $1 billion in State-Local

Partnerships (SLP) grants to match local funds for

transportation projects over the next five years. The

measure also allows the Legislature to add conditions and

criteria to the program through statute. The CTC proposed

guidelines that would provide funding to local jurisdictions

that have adopted local sales tax measures or developer fees

for transportation. These guidelines, however, do not set

aside any of these funds to create incentives for new local

revenues to be pursued in the future. In order to spur new

local funding for transportation, we recommend that the

Legislature adopt guidelines that would set aside a portion

of SLP grants for cities and counties that establish new

fees or tax measures for local transportation purposes.

Tolling. In recent years, there

has been a growing public acceptance of charging tolls for road usage,

particularly when tolls can finance new facilities or offer congestion

relief. While many observers have equity concerns regarding access to

tolled facilities across socioeconomic groups, recent research shows

that it is not just high-income travelers who choose to pay a toll when

pressed for time.

- Chapter 32 also authorizes regional agencies, in

cooperation with Caltrans, to create four high-occupancy

toll (HOT) lanes. Given increasing public acceptance of

tolls and the revenue generated by these projects, we

recommend the Legislature authorize Caltrans and the regions

to build additional HOT and toll lane projects.

Funding Highway Maintenance and Rehabilitation

Over the Long Haul

While travel on the state’s highway network continues to increase,

many of California’s highways have surpassed their design life. As a

result, maintenance and rehabilitation costs have grown considerably in

recent years. While Proposition 1B provides some one-time additional

funding for highway rehabilitation projects, it does not address the

long-term issue that maintenance and rehabilitation needs are growing

faster than the revenues which pay for these activities.

Existing Gas Tax Inadequate to

Cover Maintenance and Rehabilitation Costs. Growing

maintenance and rehabilitation demands consume increasing

portions of state gas tax revenues, which traditionally have

been the state’s primary source to fund capacity expansion on

state highways. In its 2006 annual report, CTC projects that

annual gas tax and weight fee revenues are insufficient to

address highway maintenance and rehabilitation needs. This is

because:

- Gas Tax Has Not Increased

in Over a Decade. The current state gas tax rate (18

cents per gallon) has been in place since 1994. Since then,

inflation has eroded the value of per gallon gas tax

revenues by 29 percent, so that 18 cents is worth less than

13 cents today (in constant dollar terms).

- Eroding Revenues.

The figure (see next page) shows that

between 1991 and 2006, travel on California’s roads

increased by an estimated 35 percent. Meanwhile, gas tax

revenues (in constant dollar terms) have not increased. As a

result, revenue generated per vehicle-mile traveled has

declined by more than 20 percent over the period.

Several alternatives are available to the Legislature to increase

maintenance and rehabilitation funding.

- Indexing for Inflation.

We estimate that the current 18 cent per gallon state

gas tax will generate $37 billion over the next ten years.

We recommend that the gas tax be indexed to inflation. Doing

so could generate up to $42 billion from this funding source

over the next decade-$5 billion more than would be generated

if the gas tax was not indexed to inflation.

- Indexing for Fuel Economy.

Similarly, the increasing popularity of hybrid

vehicles could result in a corresponding reduction in gas

tax revenues as total gas consumption declines. For example,

if the increasing market share of hybrid vehicles lead to a

doubling in fuel economy, the Legislature could consider

doubling the gas tax to ensure that total gas tax revenues

remain at their current level into the future.

- Taxing Alternative Fuels.

Many alternative fuels (such as ethanol and natural

gas) are taxed at a lower rate than gasoline and diesel

fuel. Thus, if alternative fuels become a more prevalent

energy source for transportation, the Legislature should

consider taxing these fuels at a comparable rate to

conventional motor fuels to ensure that revenues for uses

like highway maintenance and rehabilitation do not decline.

- Mileage-Based Fees.

Mileage-based fees offer an advantage over gas taxes in that

their revenues are not eroded by increasing fuel economy or

use of alternative fuels. Rather, the fees would closely

match the extent motorists use highways and roads. There are

privacy and technical obstacles to overcome in implementing

a mileage-based approach to fund transportation. However,

the state of Oregon is currently testing the feasibility of

implementing a mileage-based fee in Portland. Similarly, we

recommend that the Legislature examine the policy and

implementation issues that must be addressed if

mileage-based fees were to be imposed in California.

Addressing Issues in the TCRP

In 2000, the Traffic Congestion Relief Act committed $4.9 billion in

General Fund and gasoline sales tax revenues to 141 specified projects

between 2000-01 and 2005-06. Due to the state’s fiscal condition, much

of this funding was delayed or loaned to the General Fund. Current law

extends funding for TCRP through 2007-08 and establishes that most of

the loaned funds are to be repaid by June 30, 2016. Because of the

loans, as well as other delays related to specific projects, there are

TCRP projects that will not be completed until after 2010.

Given this timeline and the problems with a number of TCRP projects,

the Legislature should consider actions such as the following to ensure

that TCRP funds are used effectively.

- Establish Project Delivery

Deadlines. Many TCRP projects have fallen behind

schedule. Current law allows funds to remain available

indefinitely to these projects. The Legislature should

consider directing CTC to establish a final project delivery

deadline in order to ensure that funds are used to construct

projects in a timely manner.

- Identify Projects That Are

No Longer Viable. If there are stalled projects that

are not progressing, the Legislature may want CTC to

identify these projects so that funds may be put to other

projects in the near term.

- Redirecting Funds From

Failed Projects. For projects that miss their

construction deadline or which CTC deems as no longer

viable, the Legislature should redirect remaining TCRP funds

to other transportation projects. The Legislature has a

number of options in how it reallocates the freed-up funds.

Funds could go to projects statewide that offer congestion

relief benefits (in keeping with the goals of TCRP),

projects which are similar in type to the failed project (to

maintain the original level of investment in transit or

highways), or other projects in the original region (to

maintain the level of investment in a single region).

Acronyms and Definitions

AC Transit (Alameda Contra-Costa

County Transit)-The transit authority serving Alameda and Contra Costa

Counties.

BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit

District)-A commuter rail system serving the San Francisco Bay Area.

Caltrans (California Department

of Transportation)-The state agency responsible for building,

maintaining, and operating the state highway and intercity rail system.

CEQA (California Environmental

Quality Act)-State law establishing environmental reporting requirements

that apply to all transportation projects using state funds.

CTC (California Transportation

Commission)-A nine-member board appointed by the Governor to oversee and

administer state and federal transportation funds and provide oversight

on project delivery.

FHWA (Federal Highway

Administration)-The federal agency responsible for administering federal

highway funds.

FTIP (Federal Transportation

Improvement Program)-A three-year list of all transportation projects

proposed for federal transportation funding within the planning area of

an MPO.

ITIP (Interregional

Transportation Improvement Program)-The portion of STIP that includes

projects selected by Caltrans (25 percent of STIP).

HOT lane (High Occupancy Toll

lane)-An HOV lane, which also allows for use by single occupant vehicles

that pay a toll.

HOV lane (High Occupancy Vehicle

lane)-A lane restricted to vehicles with two (and in some cases three)

or more occupants to encourage carpooling.

LACMTA (Los Angeles County

Metropolitan Transportation Authority)-RTPA for the Los Angeles region.

MPO (Metropolitan Planning

Organization)-A federally required planning body responsible for

transportation planning and project selection in the region. In many

cases, is the same as the RTPA.

NEPA (National Environmental

Policy Act)-Federal environmental law establishing environmental

reporting requirements that apply to all projects funded with federal

funds or those requiring review by a federal agency.

P3 (Public-Private

Partnership)-Partnership between state or local government and a private

entity to design, construct, maintain, and operate a transportation

facility for a period of time.

PTA (Public Transportation

Account)-The major state account for transit purposes. Revenues include

a portion of the sales tax on gasoline and diesel fuels.

RTIP (Regional Transportation

Improvement Program)-Share of capital outlay improvement funds

controlled by regional agencies (75 percent of STIP funds).

RTP (Regional Transportation

Plan)-Federally required 20-year plan prepared by metropolitan planning

organizations, updated every three years. Includes projections of

population growth and travel demand, along with a specific list of

proposed projects to be funded.

RTPA (Regional Transportation

Planning Agency)-Planning bodies established by statute to administer

state, local, and federal funds to projects in a region.

SAFETEA-LU (Safe, Accountable,

Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for

Users)-Federal transportation act covering the period from 2004 through

2009.

SHA (State Highway Account)-The

major state transportation account for highway purposes. Revenues

include the state excise taxes on gasoline and diesel, and truck weight

fees.

SHOPP (State Highway Operation

and Protection Program)-A four-year capital improvement program for

rehabilitation, safety, and operational improvements on state highways.

SIP (State Improvement

Program)-State air quality plan to ensure compliance with state and

federal air quality standards. In order to be eligible for federal

funding, projects must demonstrate conformity with the SIP.

Spillover-A

source of revenue for the PTA, which is equal to the amount that

gasoline sales tax revenues at the 4.75 percent rate exceed the amount

generated from the sales tax on all other goods at the 0.25 percent

rate.

STA (State Transit

Assistance)-State funding program for mass transit operations and

capital projects. Current law requires that STA receive 50 percent of

PTA revenues.

STIP (State Transportation