January 31, 2007

California’s

Criminal Justice

System: A Primer

Juvenile Crime

Contents

Chapter 1:

Introduction

In recent years, the Legislature and Governor have considered and enacted numerous laws to respond to the public’s concerns with crime and the criminal justice system in California. The measures included stiffening penalties for existing criminal offenses, providing treatment for drug offenders, defining new criminal offenses, constructing new correctional facilities, providing financial assistance to law enforcement, and reorganizing the state corrections system.

In an effort to put the current discussion of crime in California in perspective, we have prepared this report to answer several key questions, including:

- How much crime is there in California? How has the level of crime changed over time? How does crime vary within California, and among the states?

- Who are the victims and perpetrators of crime?

- How does the California criminal justice system-local law enforcement, courts, and correctional agencies-deal with adult and juvenile offenders?

- What are the characteristics of adult and juveniles under the supervision of local and state correctional agencies?

- What are the costs of crime and the criminal justice system?

- What are the key criminal justice issues for policymakers today?

Although this report is not designed to present comprehensive answers to all of these questions, it does provide basic information on these issues. It does this through a “quick reference” document that relies heavily on charts to present the information. This report relies on the most recent data available from several federal and state agencies, including the U.S. Department of Justice (U.S. DOJ), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), and the Criminal Justice Statistics Center in the California Department of Justice (state DOJ). Below we describe the main components of this report.

Overview of the Criminal Justice System. Chapter 2 provides a description of how the criminal justice system is structured in California, including the various roles of the federal, state, and local governments. In addition, we identify the major features of criminal sentencing law and the most significant criminal laws enacted in recent years.

The State of Crime in California. Chapter 3 provides a mixed picture of the current state of crime in California. The crime rate in California declined substantially throughout most of the 1990s, but has increased somewhat in more recent years. Violent crime in California, however, has continued to decline even in more recent years, but is still significantly higher than the national average.

Adult Criminal Justice System. Despite the decline in crime rates over recent decades, the state has experienced a significant increase in incarceration with approximately 250,000 adult inmates in jail and prison today, as well as another 450,000 adults supervised on probation or parole. Chapter 4 describes what happens to adult offenders in the criminal justice system, including a discussion of trends in criminal arrests, disposition of court cases, and incarceration.

We also discuss two important topics in today’s adult justice system: (1) the discretion that police, prosecutors, and judges have in its operation, and (2) federal court involvement in the provision of prison inmate health care. (See our November 2006 report, California’s Fiscal Outlook [page 43], for our projections of the fiscal effect of three federal court cases concerning the state’s inmate health care system. Future publications by our office will provide more detailed analysis of this important issue.)

Juvenile Justice System. In many ways, juvenile crime trends are similar to those for adults. For example, the majority of arrests for both groups are for misdemeanor offenses rather than felonies, and felony arrest rates for both adults and juveniles have declined in recent years. Chapter 5 describes the juvenile justice system, including arrest trends, disposition of court cases, and incarceration. We also discuss the rehabilitation mission of the juvenile justice system at both the local and state levels.

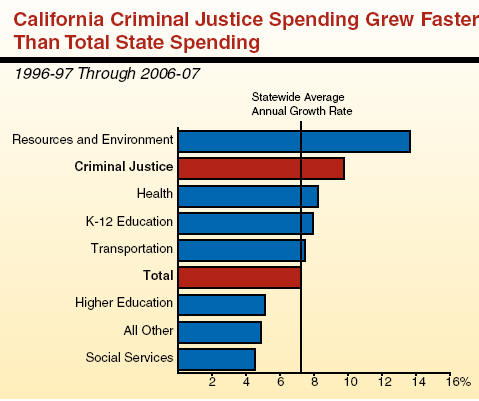

Costs of Crime and the Criminal Justice System. Chapter 6 documents how spending on the criminal justice system in California has grown steadily over the past decade, reaching $25 billion in 2003-04. Most of this spending is done by local governments, including $11 billion for police and sheriffs. The fastest-growing segment of the state’s criminal justice system is state corrections, with these costs growing at an average annual rate of about 10 percent during the past ten years. These costs have been driven in large part by increases in employee salaries, court-ordered mandates (such as for the provision of health care services), as well as inmate population growth.

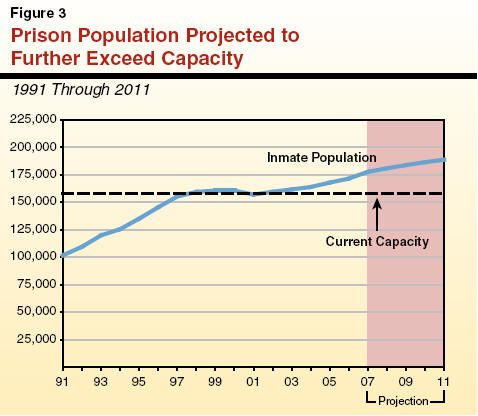

Conclusion. In Chapter 7, we identify two major state criminal justice system challenges facing policymakers. The first challenge is managing prison capacity in light of projected growth in the state’s prison population. The amount of growth projected suggests that California’s incarceration capacity, which is already strained, may be unable to adequately meet the future demand, and policymakers will have to carefully weigh options to balance population demands and the available capacity to meet those demands.

The second challenge regards correctional rehabilitation programs. While the Legislature and Governor have increased funding for programs such as education and substance abuse treatment for state inmates and parolees, this funding still only represents a very small share of the prison system budget, resulting in low participation rates for these programs. Given the number of inmates who are paroled to the community and then subsequently return to prison, it is important for policymakers to further consider the role that rehabilitation programs can play in reducing the state’s high recidivism rates.

Chapter 2:

An Overview of

California’s Criminal Justice System

The criminal justice system operates at multiple levels of government: the local, state, and federal levels. Because the vast majority of criminal activity is handled by state and local authorities, we focus in this report on the role of the state and local governments in California’s criminal justice system. The primary goal of the system is to provide public safety by deterring and preventing crime, incarcerating individuals who commit crime, and reintegrating criminals back into the community.

Criminal Sentencing Law

The criminal justice system is based on criminal sentencing law, the body of laws that define crimes and specify the punishments for such crimes. The majority of sentencing law is set at the state level.

Types of Crimes. Crimes are classified by the seriousness of the offenses as follows:

- A felony is the most serious type of crime, for which an offender may be sentenced to state prison for a minimum of one year. California Penal Code also classifies certain felonies as “violent” or “serious.” Violent felonies include murder, robbery, and rape. Serious felonies include all violent felonies, as well as other crimes such as burglary of a residence and assault with intent to commit robbery.

- A misdemeanor is a less serious offense, for which the offender may be sentenced to probation, county jail, a fine, or some combination of the three. Misdemeanors include crimes such as assault, petty theft, and public drunkenness. Misdemeanors represent the majority of offenses in California’s criminal justice system.

- An infraction is the least serious offense and is generally punishable by a fine. Many motor vehicle violations are considered infractions.

California law also gives law enforcement and prosecutors the discretion to charge certain crimes as either a felony or a misdemeanor. These crimes are known as “wobblers.”

Determinate Sentencing. Prior to 1977, convicted felons received indeterminate sentences in which the term of imprisonment included a minimum with no prescribed maximum. For example, an individual might receive a “five-years-to-life” sentence. After serving five years in prison, the individual would remain incarcerated until the state parole board determined that the individual was ready to return to the community and was a low risk to commit crimes in the future.

In 1976, the Legislature and the Governor enacted a new sentencing structure for felonies, called determinate sentencing, which took effect the following year. Under this structure, most felony punishments have a defined release date based on the “triad” sentencing structure. The triad sentencing structure provides the court with three sentencing options for each crime. For example, a first-degree burglary offense is punishable by a term in prison of two, four, or six years. The middle term is the presumptive term to be given to an offender found guilty of the crime. The upper and lower terms provided in statute can be given if circumstances concerning the crime or offender warrant more or less time in state prison. We would note that, in January 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court (Cunningham v. California) restricted a judges ability to assign the upper term. In some cases, offenders are still punished by indeterminate sentences today. Specifically, indeterminate sentences are provided for some of the most serious crimes, such as first-degree murder, as well as for some repeat offenders. In fact, about 19 percent of state prison inmates are currently serving indeterminate life sentences.

Components of the Criminal Justice System

The criminal justice system can be thought of as having three components: law enforcement, courts, and corrections. Figure 1 shows the different actors in California’s criminal justice system, including information on their level of government and responsibilities. We discuss these components in more detail below.

|

Figure 1

Roles Within California’s Criminal

Justice System |

|

These Criminal

Justice Officials… |

Who Are Subject to the

Control of… |

Must Often Decide

Whether or Not or How to… |

|

Police/Sheriffs |

Cities/Counties |

·

Enforce

laws |

|

|

|

·

Investigate crimes |

|

|

|

·

Search

people, premises |

|

|

|

·

Arrest

or detain people |

|

|

|

·

Supervise offenders in local correctional facilities

(primarily county sheriffs) |

|

District

Attorneys (prosecutors) |

Counties |

·

File

charges |

|

·

Prosecute the accused |

|

·

Reduce,

modify, or drop charges |

|

Judges |

State |

·

Set bail

or conditions for release |

|

|

|

·

Accept

pleas |

|

|

|

·

Determine delinquency for juveniles |

|

|

|

·

Dismiss

charges |

|

|

|

·

Conduct

hearings |

|

|

|

·

Impose

sentences |

|

|

|

·

Revoke

probation |

|

Probation Officials |

Counties or

|

·

Recommend sentences to judges |

|

|

Judges |

·

Supervise offenders released on probation

|

|

|

|

·

Supervise offenders (especially juveniles) in

probation camps and ranches |

|

|

|

·

Recommend probation revocation to judges

|

|

Correctional Officials |

State |

·

Assign

offenders to type of correctional facility |

|

|

|

·

Supervise prisoners |

|

|

|

·

Award

privileges, punish for disciplinary infractions

|

|

Parole Officials |

State |

·

Determine conditions of parole |

|

|

|

·

Supervise parolees released to the community |

|

|

|

·

Revoke

parole and return offenders to prison |

|

|

Law Enforcement. State sentencing laws are primarily enforced at the local level by the sheriff and police officers who investigate crimes and apprehend offenders. Law enforcement is a local responsibility in California, with funding typically provided by cities and counties. At the state level, the Attorney General provides some assistance and expertise to local law enforcement in the investigation of crimes that are multi-jurisdictional (occur in multiple counties) such as organized crime. The state also provides grants to local law enforcement for various crime-fighting activities.

Courts. Once an individual is arrested and charged with committing a crime, he or she must go through California’s trial court system. Local district attorneys, employed by the county, charge them with a specific crime and prosecute them. If the individual cannot afford an attorney, he or she is represented by a public defender, also provided by the county. Superior Court judges preside over cases that come through the system. Judge salaries, as well as all other funding for the operation of the state’s trial courts, are a responsibility of the state. The system is designed in a way that it provides flexibility for district attorneys and judges to decide how to prosecute specific cases and manage overall caseload. (See page 45 for a more detailed discussion of this topic.)

Corrections. The component of the system that supervises offenders is commonly referred to as “corrections” or the “correctional system.” In California, individuals convicted of, or adjudicated for crimes are placed under supervision either at the local level (jail and probation) or the state level (prison and parole) depending on the seriousness of the crime and the length of incarceration. Generally speaking, low-level offenders are supervised at the local level, while more serious offenders who are sentenced to more than a year of incarceration are supervised at the state level. By law, individuals who serve prison sentences are required to be on parole, typically for a minimum of three years. Although those who serve jail sentences are not required by law to be on probation, the vast majority are in fact placed on probation after their release from jail.

What Is the Difference Between the State and

Federal Criminal Justice Systems?

The state criminal justice system (including both state and local agencies) and the federal criminal justice system have much in common. For example, both systems have statutory criminal law, law enforcement agents, courts, and prisons. Procedurally, the systems are also similar, for example, offering the same protections to criminal defendants, such as the right to jury trial.

The key difference between the two systems relates to the criminal law statutes. Federal criminal law is limited to the powers of the federal government enumerated in the United States Constitution. Therefore, most federal criminal laws relate to the national government’s role in the regulation of interstate commerce, immigration, and the protection of federal facilities and personnel. Consequently, federal law enforcement tends to focus on nonviolent crimes such as drug trafficking, immigration violations, fraud, bribery, and extortion.

By comparison, state criminal law is based on the general police powers of the state and is therefore broader in scope. For example, as shown in Figure 2, more than one-half of the federal prison population is made up of drug offenders, while only 21 percent of state prison inmates were imprisoned for a drug offense. However, there is some crossover, such that some crimes-for example, weapons offenses and robbery-that are prosecutable under state law may also be prosecuted under federal law. Nevertheless, most crimes are prosecuted under state law.

|

Figure 2

Federal and State Inmate

Population |

|

2005 |

|

|

Prison Inmates |

|

|

California |

Federal |

|

Totals |

168,055 |

187,241 |

|

Offense Type |

|

|

|

Violent |

50% |

10% |

|

Property |

22 |

8 |

|

Drug |

21 |

53 |

|

Immigration |

— |

11 |

|

Other |

8 |

17 |

|

|

|

Details

may not total due to rounding. |

|

|

What Are Some Significant Changes in

Criminal Law?

The underlying structure of California sentencing law has remained unchanged since the transition to determinate sentencing in 1976. However, concern about certain types of crimes, offenders, and law enforcement capabilities has led the Legislature and voters to make some significant changes to specific areas of law. We highlight below those changes to criminal law (since 1990) that have affected large numbers of offenders.

Proposition 115: Speedy Trial Initiative. Approved by the voters in 1990, this measure made significant changes to criminal law and judicial procedures in criminal cases. The measure provided the accused with the right to due process of law and a speedy public trial and required felony trials to be set within 60 days of a defendant’s arraignment. Other provisions expanded the definition of first-degree murder and the list of “special circumstances” that could lead to a longer sentence; changed the way juries are selected for criminal trials; changed the rules under which prosecutors and defense attorneys had to reveal information to each other; and, under certain circumstances, allowed the use of hearsay evidence at preliminary hearings, which are conducted to determine if the evidence against a person charged with a crime is sufficient to bind them over for trial.

“Three Strikes and You’re Out.” In 1994, the Legislature and voters approved the Three Strikes and You’re Out law (the legislative version is Chapter 12, Statutes of 1994 [AB 971, Bill Jones]). The most significant aspect of the new law was to require longer prison sentences for certain repeat offenders. Individuals who have one previous serious or violent felony conviction and are convicted of any new felony (it need not be serious or violent) generally receive a prison sentence that is twice the term otherwise required for the new conviction. These individuals are referred to as “second strikers.” Individuals who have two previous serious or violent felony convictions and are convicted of any new felony are generally sentenced to life imprisonment with a minimum term of 25 years (“third strikers”). In addition, the law also restricted the opportunity to earn credits that reduce time in prison and eliminated alternatives to prison incarceration for those who have committed serious or violent felonies.

Proposition 21: Juvenile Crime. Proposition 21, approved by the voters in 2000, expanded the types of cases for which juveniles can be tried in adult court. The measure also increased penalties for gang-related crimes and required convicted gang members to register with local law enforcement.

Proposition 36: Drug Prevention and Treatment. Also approved by the voters in 2000, Proposition 36 provided for the sentencing of individuals convicted of a nonviolent drug possession offense to probation rather than prison or jail. As a condition of probation, the offender is required to complete a drug treatment program. The measure excluded certain offenders from these provisions, including those who refuse drug treatment or are also convicted at the same time for a felony or misdemeanor crime unrelated to drug use.

Megan’s Law Database. As a result of legislation enacted in the 1950s, the state requires sex offenders to register with local law enforcement agencies at least once annually, and additionally within 14 days of moving to a new address. Various pieces of legislation enacted in the 1990s required law enforcement to provide public access to the state DOJ database, commonly referred to as the Megan’s Law database, containing information on the residences of sex offenders. Initially, this information was available via a state-operated “900” telephone line and a CD-ROM disc available at local law enforcement agencies. In 2004, the Legislature enacted Chapter 745, Statutes of 2004 (AB 488, Parra), which made the Megan’s Law database available electronically via the Internet.

Proposition 69: DNA Samples. Enacted in 2004, this measure required state and local law enforcement agencies to collect samples of deoxyribonucleic acid, commonly known as DNA, from all convicted felons, some nonfelons, and certain arrestees for inclusion in the state’s DNA data bank. Samples from the data bank are compared to DNA evidence from unsolved crimes to look for potential matches. Although the state collected DNA samples from certain felons prior to passage of this measure, this measure greatly expanded the number of individuals from whom the state was required to collect DNA.

Senate Bill 1128 (Alquist) and Proposition 83: Jessica’s Law. In 2006, the Legislature enacted Chapter 337, Statutes of 2006 (SB 1128, E. Alquist), and voters approved Proposition 83, commonly referred to as Jessica’s Law. These new laws made a number of changes regarding the sentencing of sex offenses. Among other changes, they increased penalties for certain sex offenses, required global positioning system monitoring of felony sex offenders for life, restricted where sex offenders can live, and expanded the definition of who qualifies as a sexually violent predator who can be committed to a state mental hospital by the courts for mental health treatment.

Chapter 3:

The State of

Crime in California

Measuring Crime in California

Crime is primarily measured in two different ways. One approach is based on official reports from law enforcement agencies, which are compiled and published by the FBI. California data is published by the Criminal Justice Statistics Center in the state DOJ. These are the statistics often cited in reports and newspaper articles. The other method is through national victimization surveys in which researchers ask a sample of individuals if they have been victims of crime, regardless of whether the crime was reported to the police.

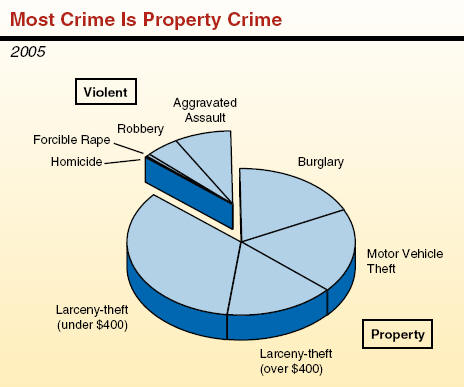

Crimes Reported to Law Enforcement. Since 1930, the FBI has been charged with collecting and publishing reliable crime statistics for the nation, which it currently produces through the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) program. Local law enforcement agencies in California and other states submit crime information, which is forwarded to the FBI. In order to eliminate differences among various states’ statutory definitions of crime, UCR reports data only on selected general crime categories, which are separated into violent and property crimes. The violent crimes measured under UCR include murder, forcible rape, robbery, and aggravated assault. Property crimes include burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft. All crime rate data provided in this chapter are based on crimes reported by local law enforcement.

The UCR crime information is typically presented in terms of rates. A rate is defined as the number of occurrences of a criminal event within a population. Crime rates are typically presented as a rate per 100,000 people. For example, California’s 2005 murder rate was 6.9, which means that there were 6.9 murders per 100,000 Californians in 2005. Presenting information in terms of rates makes it easier to compare criminal activity in regions with differing population sizes.

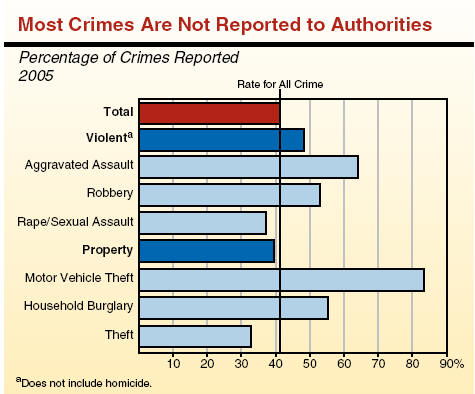

Crime Estimates Through Victimization Surveys. Crime statistics from law enforcement do not tell the entire story of crime. There is a significant amount of crime committed each year that goes unreported to law enforcement authorities and therefore is not counted in official statistics.

In order to provide a more complete picture of the amount of crime committed, the U.S. DOJ, through its National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), surveys households and asks whether they have been victims of crime. The NCVS is conducted annually at the national level, not on a state-by-state basis. It provides useful nationwide information on such issues as the number of violent and property crimes in the nation, the likelihood of victimization for various demographic groups, the percentage of crimes reported to the police, the characteristics of offenders, and the location of crimes. The NCVS uses “victimization rates” to compare the frequency of victimization among various demographic groups. The victimization rate for a particular group is presented as a rate per 1,000 people and excludes individuals under the age of 12.

What Is the State of Crime in California?

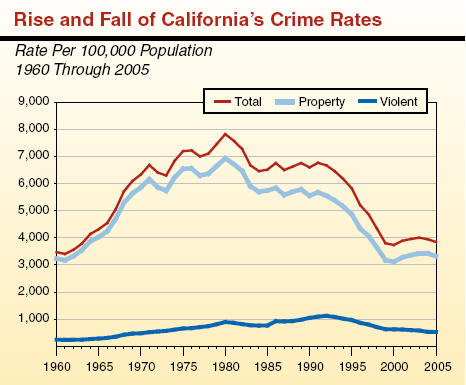

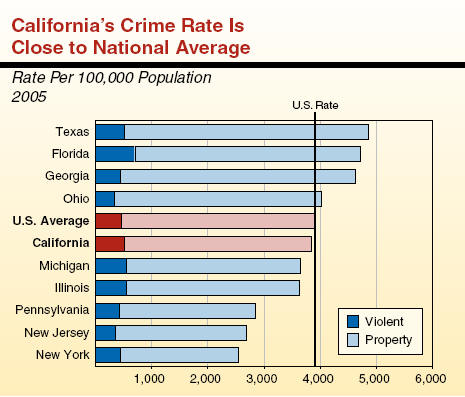

Statewide. Providing an assessment of criminal activity in California depends on the time horizon one uses. From a longer-term perspective, the state has seen substantial decreases in crime over time. Crime rates have decreased 51 percent since reaching their peak in 1980. However, shorter-term trends are not as positive. Although violent crimes have continued to decline, property crimes have increased 7 percent since 2000. Comparing California to the rest of the U.S. also results in mixed conclusions. Although California’s overall crime rate was significantly higher than the national crime rate throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, the state’s crime rate is now slightly lower than the national rate. California’s violent crime rate, however, remains higher than the U.S. rate.

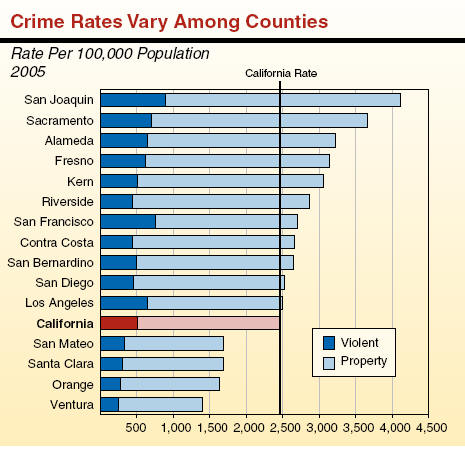

Regional Variation. It is important to note that there is also significant variation in crime rates among the regions of California. Generally, the Central Valley has the highest crime rates of any region in California. Among the most populous California counties, three of the four counties with the highest crime rates (San Joaquin, Sacramento, and Fresno) are located in the Central Valley. The counties with the lowest crime rates are in Southern California and the Bay Area-specifically, Ventura, Orange, and Santa Clara Counties, as shown on page 22.

This chapter provides information on crime rates in California. This includes data on the prevalence of crime in California-including comparisons of California’s crime rates to those of other states and comparisons among California counties-as well as data on the offenders and victims of crime. The chapter also discusses two other crime-related topics: (1) the major factors that have caused a decline in crime rates, and (2) the prevalence of drug crimes, which are not included in traditional crime rate data.

How Prevalent Is Crime in California?

- California experienced a decline in crime rates for nine consecutive years, from 1992 to 2000. During this period, the overall crime rate decreased by 56 percent. This trend is similar to declines in crime patterns in the rest of the U.S.

- Since 2000, however, overall crime in California has increased 3 percent. The increase is driven by increases in property crime, which has increased 7 percent. The violent crime rate has continued to decline, dropping 15 percent since 2000.

- Overall, California reported 3,849 crimes per 100,000 people in 2005.

- Property crime accounted for about 86 percent of reported crimes in California in 2005, and violent crime accounted for 14 percent.

- Although the proportion of crime changes slightly every year, property crimes consistently represent approximately 85 percent of all reported crimes.

- California’s crime rate was slightly lower than the U.S. crime rate in 2005, and was fifth highest among the ten largest states.

- California also has the fifth highest violent crime rate among the ten largest states, 11 percent higher than the U.S. rate. California’s property crime rate ranks fifth among the largest states, 3 percent below the national rate.

- California’s property crime rate has increased 7 percent since 2000, the only large state to have experienced a property crime increase. Much like the rest of the nation, however, California has continued to experience decreases in violent crime.

- Among the 15 largest counties in California, San Joaquin had the highest violent crime and property crime rates. Ventura had the lowest violent and property crime rates.

- Since 2000, property crime rates have increased in 12 of the 15 large counties. Violent crime has increased in 5 of the 15 large counties.

- Kern had the largest increase in property crime since 2000, at 34 percent, while Fresno had the largest decrease, with a 9 percent decline.

- Between 2000 and 2005, San Mateo had the highest increase in violent crime, at 22 percent, while Los Angeles had a 30 percent decrease, the largest decrease of all the large counties.

Who Is Involved in Crime?

Who Commits Crime?

The NCVS, conducted annually by the U.S. DOJ, provides useful information about criminal offenders in the U.S. The 2005 NCVS shows that:

- About 79 percent of violent crimes involving one offender were committed by a male.

- In 52 percent of assaults, the offender was someone known to the victim. However, the offender was someone known to the victim in only 20 percent of robberies. In rapes and sexual assaults, offenders were known by 65 percent of their victims. For all violent crimes, females were more likely than males to be victimized by someone they know.

- About 45 percent of violent crimes were committed by individuals ages 15 through 29, despite representing only 21 percent of the overall population.

- About 28 percent of violent crimes involved an offender who was perceived to be under the influence of drugs or alcohol.

Who Are the Victims of Crime?

The 2005 NCVS also provides information on the characteristics of victims of crime. Of particular interest are the following:

- Age. Individuals age 12 to 24-those most likely to commit violent crimes-were also most likely to be the victims of violent crime. The chances of becoming a victim of violent crime were significantly lower for all other age groups.

- Sex. The likelihood of being a victim of violent crime was 45 percent higher for males than for females.

- Ethnicity. Violent victimization rates for blacks were 37 percent higher than those for whites. Hispanics had violent victimization rates 24 percent higher than whites. Black households were victims of property crimes at a rate 7 percent lower than whites, and Hispanic household victimization rates were 35 percent higher than whites. These rates, however, can vary significantly from year to year.

- Economic Status. Poorer households were much more likely to experience an unlawful entry into their homes (burglary) than wealthier households. However, while wealthier households do not experience burglary as often, they were more likely to be victims of theft, which includes the taking of household items, motor vehicle accessories, or other objects without entry into the home.

Key Topics in California Crime Trends

What Major Factors Have Caused

Declining Crime Rates?

During the 1990s, the U.S. experienced an unprecedented decrease in crime rates at a time when many experts were predicting that crime would reach all-time highs. This decrease was consistent throughout the nation, from large urban cities to small rural areas. Numerous studies have been conducted to examine the causes of this drop in crime levels. Although there is no consensus on all causes of the decreases in the crime rate, the following factors are widely considered to be among the most significant factors in the crime drop:

- Increased Prison Population. Higher rates of incarceration reduce crime for two reasons. First, keeping a higher proportion of criminals in prison keeps them from committing new crimes. Second, high incarceration rates are believed to serve as a deterrent, discouraging others from committing future crimes. In California, the boom in the prison population was due to factors such as increases in the number of individuals sentenced to prison by the courts, higher rates of parole violators returning to prison, and the use of sentence enhancements.

- More Police. Studies have also shown that a nationwide increase in police officers per capita has been a factor in reducing crime rates. There has been little conclusive research, however, focusing on whether certain types of police strategies, such as so-called community policing, have been effective strategies for reducing crime.

- Demographic Factors. Changes in the state’s crime rate follow changes in the portion of the population aged 18 through 24, the age group most likely to be involved in criminal activity. In California, the share of the population in the 18 to 24 age group increased throughout the 1970s until reaching its peak in 1978, when 18 to 24 year-olds represented 14 percent of the population. The share of 18 to 24 year-olds decreased consistently throughout the 1980s and 1990s, until 1997, when the share had dropped to 10 percent. This pattern follows the peaks and valleys of the state’s crime rates; California reached its peak crime rate in 1980 and its lowest crime rate in 2000, consistent with increases and decreases in the share of 18 to 24 year-olds in the population. During the next 15 years, the share of 18 to 24 year-olds in the state’s population is projected to remain stable at approximately 10 percent of the population.

- Economic Factors. Changes in unemployment, poverty, and mean household income also affect crime rates. In the U.S., the economic boom of the late 1990s likely played a role in the reduction of crime rates. Although economic factors are often considered a central component to variations in crime, research shows that factors such as police officers per capita and prison population may have a greater impact on the crime rate.

Drug Crimes

A Significant Share of Felony Arrests and Incarceration. The FBI Crime Index focuses solely on crimes that involve violence against persons or the loss of personal property. These statistics do not include crimes related to the possession, sale, or manufacture of illegal drugs. However, drug crimes do represent a significant portion of all crimes committed in the U.S. and within California. In 2005, felony drug arrests represented 30 percent of all felony arrests in California. As a result, approximately 21 percent of inmates in California’s prisons were incarcerated for a drug-related crime. This is a significant increase as compared to 20 years ago when only 11 percent of state inmates were incarcerated for drug offenses. This increase is likely due to changes in drug laws-particularly in the 1980s-that increased penalties for the possession and sale of illegal drugs.

Although there has not been a recent change in arrest or incarceration rates for drug crimes, there has been a change in the type of drugs most commonly used. California has experienced growth in the use of methamphetamines, which has become an increasingly popular drug in the western U.S. In addition, California is the primary source of methamphetamine sold in the U.S.

Drug Courts. Because a significant number of individuals are frequently imprisoned solely for drug-related crimes, several California counties began using drug courts for managing individuals with substance abuse problems. The first drug court was established in Alameda County in 1993. Rather than seeking imprisonment, drug courts use judicially supervised treatment, mandatory drug testing, and a system of sanctions and rewards to help individuals become sober and successfully return to their communities.

This focus on treatment rather than incarceration became a statewide priority after the enactment of Proposition 36 in 2000, which provided the option of treatment for drug offenders who had been convicted of only drug-related crimes. In 2006, the Legislature increased the state’s annual funding for Proposition 36 programs, providing counties with a total General Fund appropriation of $145 million for this purpose in 2006-07. This action was intended to allow counties to maintain the level of support for these programs in 2005-06 using funding carried over from prior years. The Governor’s 2007-08 budget plan proposes a net reduction of $25 million in support for Proposition 36 programs.

Chapter 4:

Adult Criminal

Justice System

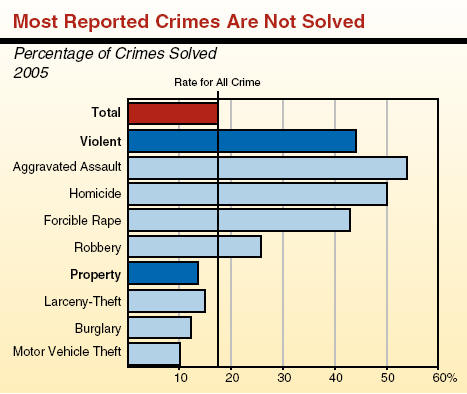

As indicated in the prior chapter, victimization studies show that a substantial amount of crime goes unreported to law enforcement. According to NCVS studies, about 60 percent of all crimes are not discovered or reported to law enforcement authorities. In addition, of the crimes reported to law enforcement officials, only about one-fifth are solved. In 2005, for example, only about 17 percent of all reported crimes were solved or “cleared” (that is, a person was charged with a crime). This figure has remained relatively stable for a number of years.

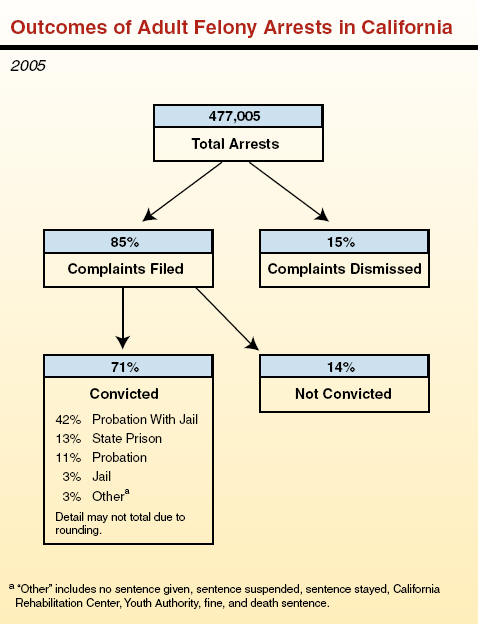

Following an arrest, a law enforcement agency may file a complaint against the individual and he or she may be prosecuted. Prosecution may result in the person being convicted. Persons who are convicted are given a fine and/or are sentenced to county probation, county jail, county probation with a jail term, or state prison. The vast majority of convicted offenders end up on county probation and/or in county jail (as shown on page 33).

Although the Legislature and Governor enact laws that define crimes and set penalties, criminal justice officials exercise a great deal of discretion in enforcing these laws. The greatest discretion is at the local level, when police decide whether to arrest someone for a crime, prosecutors decide whether or how to charge a person with a crime, and courts adjudicate suspected offenders (as discussed on page 45).

This chapter provides information on the adult criminal justice system. This includes data on what happens to adult offenders from arrest through incarceration. The chapter also provides information on the characteristics of those in the criminal justice system, such as demographics and criminal history. In addition, this chapter discusses two topics affecting the adult criminal justice system: (1) the discretion of police officers, prosecutors, and judges affecting outcomes for adult offenders, and (2) federal court intervention in the prison health care system.

What Happens to Adult Offenders?

- According to NCVS studies, 41 percent of the crimes committed were reported to authorities in 2005. About 47 percent of all violent crimes were reported, while only 40 percent of property crimes were reported. (This report generally uses the term “violent” crimes to signify a category of offenses committed against persons-such as homicides and assaults-and is broader than the list of felonies defined as violent under the Three Strikes law.)

- About 83 percent of motor vehicle thefts were reported to the police, the highest rate of the major crime categories. This is likely due to the fact that individuals must file police reports in order to file auto insurance claims.

- Only 38 percent of rapes and sexual assaults were reported to the police, lowest among violent crimes.

- In 2005, 44 percent of violent crimes in California were solved, while 13 percent of property crimes were solved.

- A crime is typically considered solved, or cleared, when someone has been arrested, charged for the crime, and turned over for prosecution.

- Generally, those crimes in which the offender is more likely to be a relative or acquaintance of the victim, such as homicide and aggravated assault, have a higher likelihood of being solved.

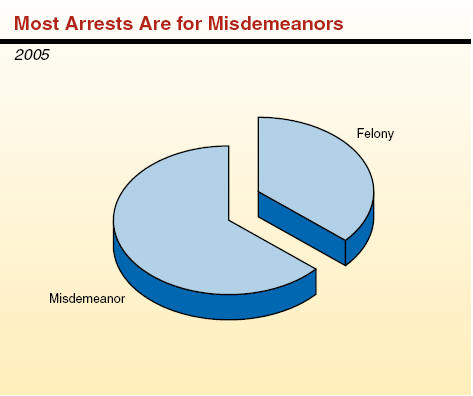

- There were almost 1.5 million arrests of adults and juveniles for felonies and misdemeanors in California in 2005.

- About 64 percent of the arrests were for misdemeanors, while 36 percent were for felonies.

- The share of arrests that are misdemeanors and felonies has remained constant over the past ten years.

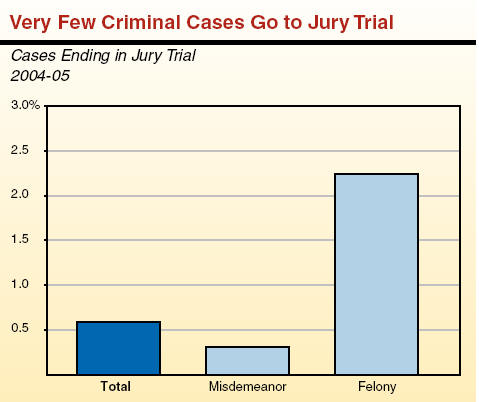

- In 2004-05, there were 1.2 million felony and misdemeanor dispositions in California’s Superior Courts. Only 8,000 of those cases, or 0.6 percent of all dispositions, reach a jury trial.

- Only 0.3 percent of misdemeanor cases reach a jury trial.

- About 2.2 percent of felony cases go to a jury trial, a significantly higher proportion than for misdemeanor cases, but still a very small portion of the total.

- Of felony cases that do not go to jury trial, 80 percent are plea-bargained and 20 percent result in acquittals, dismissals, or transfers. For misdemeanor cases, approximately 70 percent of cases that do not go to trial lead to a guilty plea by the defendant.

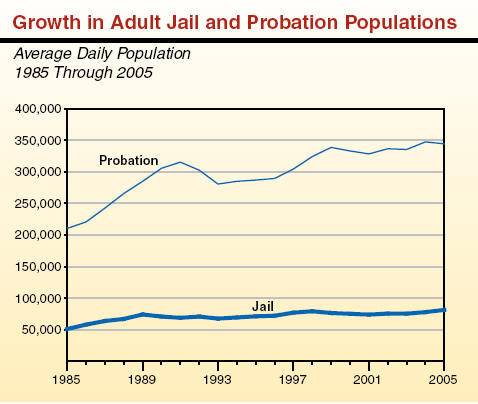

- Between 1985 and 2005, the jail population grew from 51,000 inmates to 81,000 inmates (about 2 percent annually). Most of this growth occurred during the 1980s.

- The relative stability in the jail population since 1989 is in part due to federally-imposed caps on jail population. By 2005, 20 counties had jails placed under such caps.

- Many more offenders are on probation than in jail. The number of adults on probation in California grew by less than 3 percent annually between 1985 and 2005, going from 210,000 to approximately 344,000 probationers.

- Of the 344,000 adults on probation in 2005, 77 percent were on probation for a felony, with the remainder misdemeanors. In some counties all probationers are convicted of a felony. In other counties, less than 50 percent of probationers are convicted of a felony.

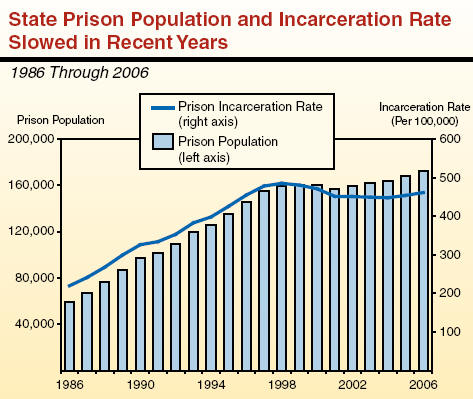

- The prison population grew from about 59,000 inmates in 1986 to 173,000 inmates in 2006 (5 percent average annual growth). Similarly, the prison incarceration rate grew from 220 to 460 inmates per 100,000 Californians over the same period (4 percent average annual growth).

- Most of this growth occurred between 1986 and 1998. This period was one of declining crime rates but also included the implementation of tougher sentencing laws and a prison construction boom that activated 20 state prisons.

- The prison population is projected to grow by more than 17,000 inmates over the next six years. This level of growth would significantly exceed the total bed capacity of the prison system in the near term, including housing in nontraditional beds in gyms and dayrooms.

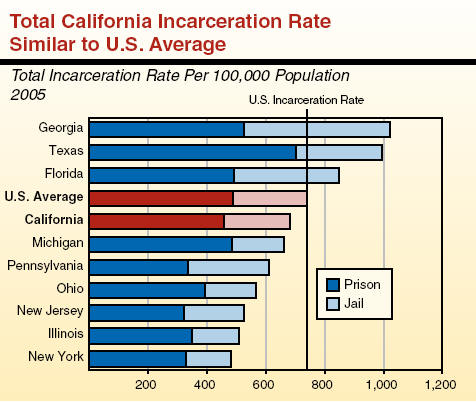

- California’s total incarceration rate, including both inmates in local jails and prisons is 683 (per 100,000 population). This is relatively close to the national average of 740.

- As with most states, roughly two-thirds of California’s incarcerated population is housed in state prisons.

- Of the ten largest states, Georgia has the highest incarceration rate (1,022), more than twice the rate of New York (480).

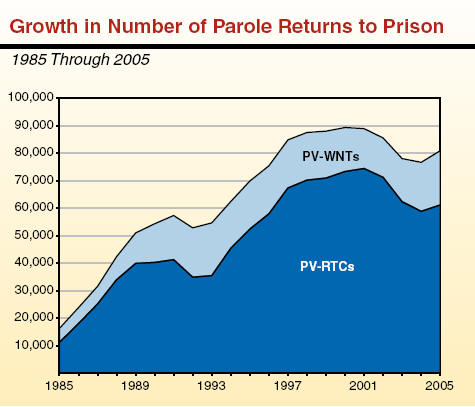

- Most parole violators (PVs) are returned to custody (PV-RTC) for violations of the conditions of their parole, while others are convicted in courts for new crimes with new terms (PV-WNT).

- The total number of parole violations that resulted in an offender being returned to prison has increased five-fold over the past 20 years from about 16,000 PVs in 1985 to 81,000 in 2005. There were about 115,000 individuals under state parole supervision at the end of 2005.

- The larger number of parole returns mostly reflects increases in the total prison and parole populations, which have grown by almost four-fold since 1985. This increase also reflects a rise in the rate at which parolees are returned to prison as PV-RTCs. The PV-RTC rate has increased by about 15 percent during the past 20 years due in part to changes in parole revocation regulations.

Who Is in Corrections?

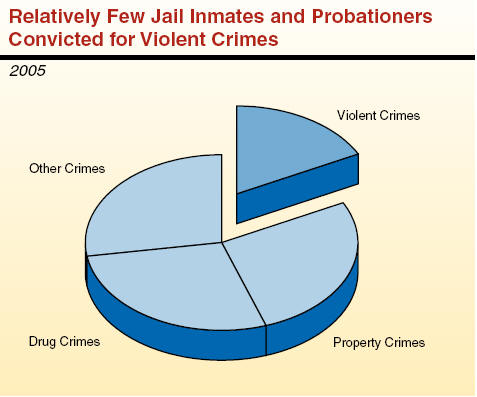

- About 176,000 individuals were sentenced to local corrections-jail, probation, or both-in 2005. About 76 percent of the total were sentenced to both jail and probation.

- Of this total, about 18 percent were convicted for violent crimes, while 55 percent were convicted for property or drug offenses. About 27 percent were convicted for other crimes, including driving under the influence or possession of a weapon.

- The fact that individuals committing violent crimes make up a relatively small share of the total sentenced to local corrections largely reflects the fact that violent crimes represent less than 19 percent of all felony convictions.

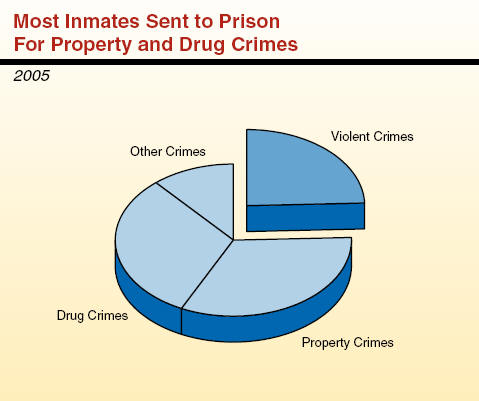

- Almost two-thirds of court admissions to state prison are for property and drug offenses, including drug possession (15 percent), drug sales (15 percent), burglary (9 percent), and auto theft (7 percent).

- About one-quarter of admissions to prison from the courts are for violent crimes. Of these, the most common offenses are assault (13 percent) and robbery (5 percent).

- The “other crimes” category include weapons possession (5 percent) and driving under the influence (2 percent).

|

Demographics of the

Prison Population |

|

2006 |

|

|

Prison

Population |

California Adult Population |

|

Total Population |

172,508 |

27,648,604 |

|

Gender |

|

|

|

Male |

93% |

50% |

|

Female |

7 |

50 |

|

Ethnicity |

|

|

|

Black |

29% |

6% |

|

Hispanic |

38 |

29 |

|

White |

28 |

51 |

|

Other |

6 |

14 |

|

Age |

|

|

|

18‑19 |

1% |

4% |

|

20‑29 |

31 |

19 |

|

30‑39 |

31 |

20 |

|

40‑49 |

26 |

21 |

|

50‑59 |

9 |

16 |

|

60 and older |

2 |

20 |

|

|

|

Details

may not total due to rounding. |

|

|

- The prison population is predominantly comprised of male blacks and Hispanics age 20 through 39.

- By comparison, the California population has significantly higher percentages of women, whites, and older individuals than are in prison.

- During the past 20 years, the percentage of inmates who are Hispanic has increased by about 10 percent, while the percentage that is white or black has decreased. Over this period, the percentage of inmates age 50 or older, more than doubled. The gender distribution of the prison population has remained stable.

|

Striker Population by Most Recent

Offense |

|

2006 |

|

Current Offense |

Third Strikers |

Second Strikers |

Total |

|

Number |

Percent |

|

Violent Crimes |

3,514 |

12,935 |

16,449 |

40% |

|

Robbery |

1,821 |

4,884 |

6,705 |

16 |

|

Assault With a Deadly Weapon |

458 |

2,645 |

3,103 |

8 |

|

Assault/Battery |

426 |

2,432 |

2,858 |

7 |

|

Property Crimes |

2,414 |

9,147 |

11,561 |

28% |

|

1st Degree Burglary |

931 |

2,502 |

3,433 |

8 |

|

2nd Degree Burglary |

479 |

1,701 |

2,180 |

5 |

|

Petty Theft With a Prior |

359 |

1,400 |

1,759 |

4 |

|

Drug Crimes |

1,295 |

7,880 |

9,175 |

22% |

|

Possession of a

Controlled

Substance |

681 |

3,782 |

4,463 |

11 |

|

Possession of a Controlled

Substance for Sale |

313 |

2,369 |

2,682 |

7 |

|

Sale of a Controlled Substance |

198 |

1,091 |

1,289 |

3 |

|

Other Crimesa |

722 |

3,313 |

4,035 |

10% |

|

Possession of a Weapon |

432 |

1,825 |

2,257 |

5 |

|

Totals |

7,945 |

33,275 |

41,220 |

100% |

|

|

|

a For

example, arson and driving under the influence. |

|

|

- About 40 percent of all strikers committed a violent crime as their current offense, while 50 percent committed a property or drug offense.

- Third strikers are more likely than second strikers to have a current offense that is a violent crime. About 44 percent of third strikers (3,514) and 39 percent of second strikers (12,935) are currently incarcerated for a violent crime.

- In 2006, strikers made up about 24 percent of the total prison population.

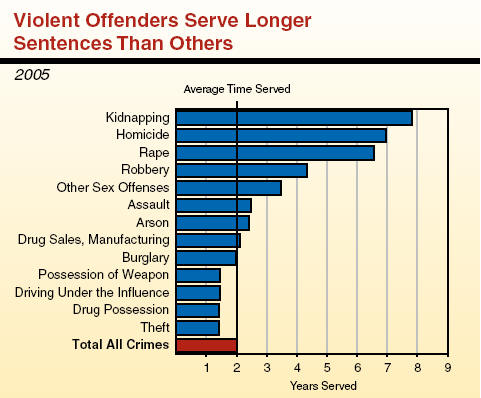

- In 2005, there were more than 64,000 inmates released from prison after completing their prison sentence. On average, these inmates were incarcerated for two years.

- About 78 percent of inmates released served time for a property, drug, or other nonviolent offense. These offenders were incarcerated for an average of less than two years. On average, inmates who committed violent crimes-such as kidnapping, sex offenses, or homicide (including murder and manslaughter)-were incarcerated for an average of more than three years.

- Data on the average time served in prison shown above is for offenders released from prison. But some offenders are never released. As of December 31, 2005, about 31,700 inmates (19 percent of the inmate population) were serving life terms in prison and over 600 inmates were on death row awaiting execution.

|

Three-Fourths of

Parole

Population Resides in Ten Counties |

|

2006 |

|

County |

Parolees |

Percent |

|

Los Angeles |

35,376 |

30% |

|

San Bernardino |

8,815 |

8 |

|

San Diego |

7,626 |

7 |

|

Orange |

7,229 |

6 |

|

Riverside |

7,193 |

6 |

|

Santa Clara |

5,344 |

5 |

|

Fresno |

4,743 |

4 |

|

Kern |

4,106 |

4 |

|

Sacramento |

3,603 |

3 |

|

Alameda |

3,309 |

3 |

|

All other counties |

29,453 |

25 |

|

Total California |

116,797 |

100% |

|

|

|

Detail may not total due to rounding. |

|

|

- Under state law, all inmates released from prison must serve a term on parole. In the 2007-08 budget, the Governor proposed modification of this policy, which would provide an exception for certain low-level offenders.

- Generally, inmates leaving prison are required by law to parole to the county in which they were prosecuted. About 75 percent of the 117,000 parolees statewide are concentrated in ten counties. These counties represent 72 percent of the total California population.

- Los Angeles County has more than 35,000 (30 percent) of the total parole population. In total, 28 percent of Californians reside in Los Angeles County.

Key Topics in Adult Criminal Justice

Discretion Among Police Officers, Judges, and

District Attorneys

Although it is sometimes overlooked, police (including county sheriffs), judges and district attorneys (DAs) have a great deal of discretion in carrying out their responsibilities that can significantly affect trends in punishment and incarceration within county jails and the state prison system.

Police. The actions of law enforcement agencies primarily affect the nature of the criminal cases that will be reviewed by DAs and judges. Law enforcement agencies decide how to distribute officers throughout their jurisdiction and prioritize the use of their resources in enforcing criminal laws. When they encounter different types of crime, police officers decide which investigations to conduct and which individuals to arrest. Once an arrest has been made, police officers also can decide to release an arrestee without filing criminal charges.

District Attorneys. The DAs have a significant amount of authority that affects the outcome of many criminal cases. The DAs review information for various cases and decide which cases to prosecute and which to dismiss, based on available evidence and the county’s priorities. Once they decide to prosecute a case, they also decide whether to plea bargain with a defendant, thereby foregoing a jury trial in exchange for a guilty plea to a lesser offense. Since a very small percentage of cases end up in a jury trial (as shown on

page 34), the bargaining decisions of DAs ultimately determine the punishment for virtually all criminal cases. In addition, DAs can have a significant impact on the cases that do end up in a jury trial. For example, the DA decides whether to pursue the death penalty for an individual who has been charged with murder. Also, DAs can decide whether to seek a sentencing enhancement that would ensure a longer prison sentence upon conviction, such as under the Three Strikes law.

Judges. Once an individual has been convicted of a crime, judges have final discretion in determining prison or jail sentences. Under California sentencing law, a range of punishments is provided for many types of crimes. For example, first-degree burglary is punishable by imprisonment for either two, four, or six years; the particular sentence that a convicted burglar receives depends on the decision of the judge. However, we would note that a ruling made by the U.S. Supreme Court in January 2007

(Cunningham v. California), restricts a judge’s ability to assign sentences that are higher than the presumptive term. In addition, judges have the discretion to sentence a convicted felon to probation in lieu of a prison term, and dismiss prior strikes so that a felon is not required to serve additional prison time as otherwise required by the Three Strikes and You’re Out law.

Overall. A number of factors play a role in the decisions made by police, DAs, and judges. Some relate to the specifics of each case, such as the severity of the crime and the criminal history of the defendant. Other, broader considerations can also come into play. For example, a judge might be less likely to require jail time for a defendant if county jails are over capacity. Similarly, a DA might be more likely to plea bargain if the court is facing an overwhelming number of cases. On the other hand, a growing problem in the community, such as drugs or gangs, might lead to stronger action by law enforcement, judges, and DAs, leading to higher arrest rates, less plea bargaining, and longer sentences. County sheriffs, county DAs, and superior court judges are publicly elected in each county. This explains in part why certain counties tend to hand down harsher sentences to criminal offenders than others. For example, after adjusting for population and arrest rates, Kern County is much more likely to impose longer prison sentences under the state’s Three Strikes law than San Francisco County.

The discretion that police, judges, and DAs have in these matters can have significant effects on the state criminal justice system. Together they affect rates of arrest, lengths of imprisonment, the number of individuals incarcerated in county jails and state prison, the length of parole and probation, and, ultimately, the overall costs of the state criminal justice system and the share of these costs borne by the state and local governments.

Correctional Health Care:

Federal Court Supervision

Court Findings. The CDCR operates three main types of health care programs: medical, mental health, and dental care. Each program is currently under varying levels of federal court supervision based on court rulings that the state has failed to provide inmates with adequate care as required under the Eighth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The courts found key deficiencies in the state’s correctional programs, including: (1) an inadequate number of staff to deliver health care services, (2) an inadequate amount of clinical space within prisons, (3) failures to follow nationally recognized health care guidelines for treating inmate-patients, and (4) poor coordination between health care staff and custody staff.

The health care case with the greatest level of court involvement relates to CDCR’s medical program. Since April 2006, medical services have been administered by a federal receiver, whose mandate is to bring the department into compliance with constitutional standards. To that end, the receiver’s powers include hiring and firing medical staff, entering into contracts with community providers, and acquiring and disposing of property, including new information technology systems.

Potential Costs. Compliance with court requirements in the three health care programs is expected to result in significant additional costs to the department over the next several years, including costs to attract high-quality health care professionals and expand clinical space to accommodate added staff. We have estimated that these costs could eventually exceed $1.2 billion annually by 2010-11, particularly if the federal courts order the state to construct new health care facilities. The Legislature will play a key role as it (1) reviews support and capital outlay proposals intended to improve the delivery of health care services to inmates and (2) monitors the steps taken to improve inmate patient care with the goal of eventually having the court shift jurisdiction over these matters back to the state.

Chapter 5:

Juvenile Justice

System

Unlike the adult criminal justice system, the stated purpose of the juvenile justice system is to focus

primarily on rehabilitation rather than punishment. To this end, counties and state juvenile facilities provide significantly more education, treatment, and counseling programs to juvenile offenders as compared to adult offenders. Consequently, correctional programs for juveniles tend to be more expensive to operate than for adults.

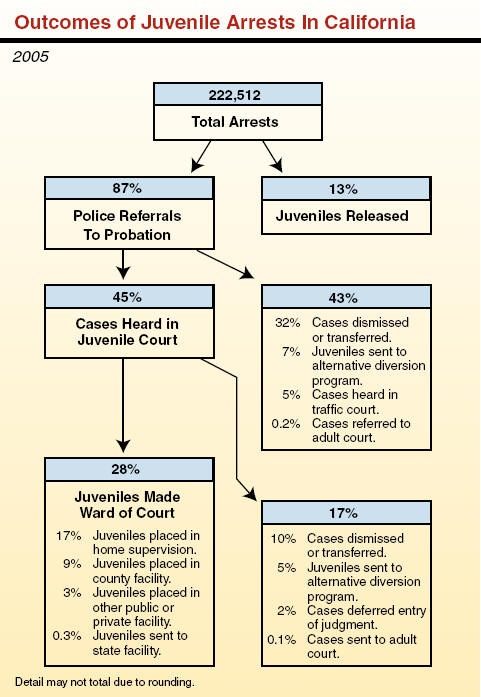

Generally, the juvenile justice system is a local responsibility. Following the arrest of a juvenile, the law enforcement officer has the discretion to release the juvenile to his or her parents, or to take the suspect to juvenile hall and refer the case to the county probation department. Probation officials decide how to process the cases referred to them. For example, they can choose to close the case at intake or, with the permission of the juvenile’s parents, place a juvenile offender on informal probation. About one-half of the cases referred to probation result in the filing of a petition with the juvenile court for a hearing. In 2005 approximately 99,000 petitions were filed in juvenile court (as shown on page 57).

Taking into account the recommendations of probation department staff, juvenile court judges decide whether to make the offender a ward of the court and, ultimately, determine the appropriate placement and treatment for the juvenile. Placement decisions are based on such factors as the juvenile’s offense, prior record, criminal sophistication, and the county’s capacity to provide treatment. Judges declare the juvenile a ward of the court almost two-thirds of the time. Most wards are placed under the supervision of the county probation department. These youth are typically placed in a county facility for treatment (such as juvenile hall or camp) or supervised at home. Other wards are placed in foster care or a group home.

A small number of wards (under 2 percent annually), generally constituting the state’s most serious and chronic juvenile offenders, are committed by the juvenile court to the CDCR’s Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) (previously known as the Department of the Youth Authority) and become a state responsibility (as shown on page 57). In addition, juveniles tried in adult criminal court for particularly serious or violent crimes are placed in a DJJ facility until their 18th birthday, at which time they are transferred to state prison for the remainder of their sentence.

This chapter provides information on the juvenile justice system. This includes data on juvenile arrest rates, the characteristics of juvenile offenders, and the outcomes for juvenile arrestees. The chapter also discusses two topics affecting the juvenile justice system: (1) reforming DJJ juvenile facilities, and (2) the changing roles of the state and local governments in the juvenile justice system.

Who Are Juvenile Offenders?

|

Legal Categories of Juvenile

Offenders |

|

|

|

|

Informal Probationers Welfare and Institutions

Code Section 654

Known as “654s” |

·

Juveniles who have committed a minor

offense. |

|

·

Probation officers have a great deal

of flexibility and can place a juvenile on informal

probation if the officer decides the juvenile is

under the jurisdiction of the juvenile court or is likely to be under its jurisdiction in the

future. |

|

|

·

These juveniles are often diverted

into substance abuse, mental health, crisis

shelters, or other services. |

|

Status Offenders

Welfare and Institutions

Code Section 601

Known as “601s” |

·

Juveniles who have committed offenses

unique to a juvenile, such as truancy, a curfew

violation, and incorrigibility. |

|

·

They can be placed on formal probation

but cannot be detained or incarcerated with criminal

offenders. |

|

Criminal Offenders

Welfare and Institutions

Code Section 602

Known as “602s”

|

·

Offenders under the age of 18 years

who commit a misdemeanor or felony. |

|

·

Subject to the jurisdiction of a

juvenile court. |

|

·

Can

be placed on formal probation, detained before

adjudication in a juvenile hall, and/or incarcerated

after adjudication in a county or state facility. |

|

|

·

They are treated differently from

adults; they are not “tried”, but “adjudicated”;

they are not “convicted,” but rather, their

“petition is sustained.” |

|

Juveniles Remanded

to Superior Court Welfare and Institutions

Code Section 707

Known as “707Bs”

or remands |

·

Any juvenile age 14 or older, who

commits specified felonies and is determined not fit

for adjudication in juvenile court. |

|

·

Tried in superior court as an adult. |

|

·

If convicted, is sentenced to state

prison and held in a DJJ facility for all or part of

sentence. |

|

·

If

convicted, is sentenced to state prison and held in

a DJJ facility for all or part of sentence. |

|

|

|

Juvenile Arrests by

Gender, Race, and Age |

|

2005 |

|

|

Juvenile Arrests |

California

Youth Population |

|

Totals |

222,512 |

4,493,439 |

|

Male

|

74% |

51% |

|

Female |

26 |

49 |

|

Black |

17% |

8% |

|

Hispanic |

48 |

46 |

|

White |

28 |

33 |

|

Other |

7 |

14 |

|

Ages

10‑11 |

2% |

24% |

|

Ages 12‑14 |

27 |

38 |

|

Ages 15‑17 |

71 |

38 |

|

|

- In 2005, males accounted for about 74 percent of all juvenile arrests in California. Males accounted for more than 80 percent of all juvenile

felony arrests.

- Most juveniles arrested in 2005 were age 15 through 17. Only 2 percent of juvenile arrests were in the 10 and 11 age group.

- Black and Hispanic juveniles represented about one-half of California’s juvenile population age 10 through 17 in 2005, but they accounted for almost two-thirds of juvenile arrests.

How Prevalent Is Juvenile

Crime in California?

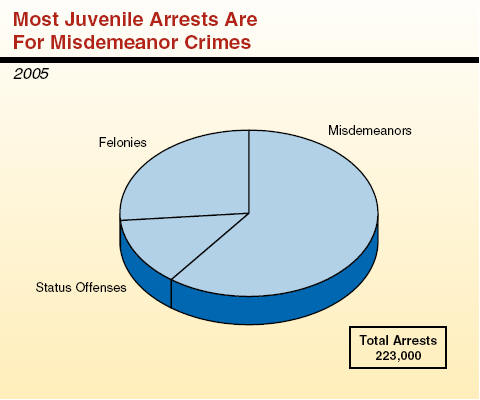

- There were almost 223,000 juvenile arrests in California in 2005.

- Misdemeanor crimes-including crimes such as petty theft and assault and battery-accounted for 60 percent of all juvenile arrests.

- Felony arrests, such as burglary, accounted for 27 percent of all juvenile arrests.

- So-called status offenses, which include truancy and curfew violations, accounted for 13 percent of juvenile arrests in 2005.

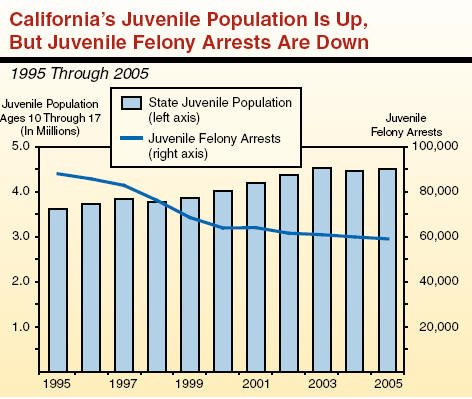

- Although the population of juveniles in California has increased by about 24 percent since 1995, the number of juvenile felony arrests has

decreased by 33 percent.

- Juvenile misdemeanor arrests declined by about 6 percent between 1995 and 2005, from about 142,000 arrests in 1995 to less than 134,000 arrests a decade later.

- There is no consensus among researchers as to the cause of the declining juvenile arrest rates. One possible explanation is the implementation of more effective prevention and intervention programs. In addition, some of the same factors that have led to declining crime rates nationwide-such as increased law enforcement personnel and economic factors-may be contributing to declining juvenile crime.

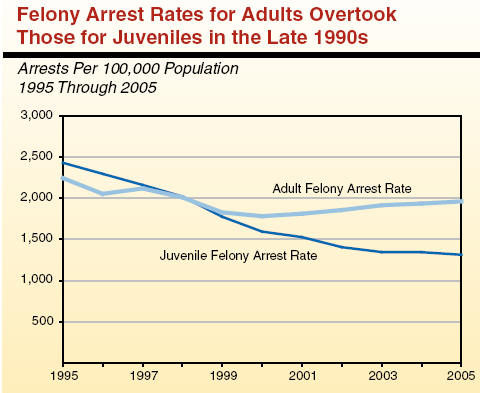

- The juvenile felony arrest rate in California decreased by 46 percent between 1995 and 2005. Specifically, the number of juvenile felony arrests per 100,000 juveniles fell from more than 2,400 in 1995 to about 1,300 in 2005.

- The adult felony arrest rate also decreased during this period but has increased in more recent years. The number of adult felony arrests per 100,000 adults was almost 2,000 in 2005.

- The adult felony arrest rate surpassed the juvenile felony arrest rate in 1999 and the “gap” between the two rates has widened every year since that time.

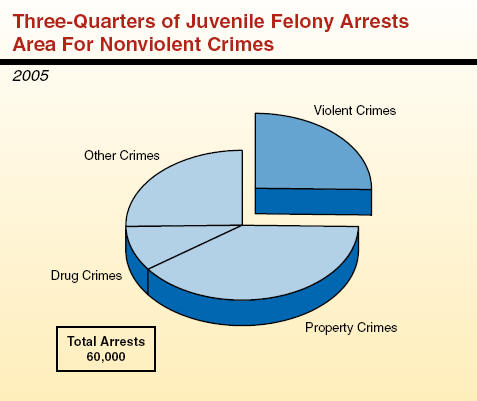

- There were about 60,000 juvenile felony arrests in 2005.

- Property crimes-such as burglary and theft-accounted for about 40 percent of all juvenile felony arrests.

- Drug offenses accounted for 10 percent of juvenile felony arrests in 2005. The “other crimes” category, which includes such felonies as illegal possession of a firearm, accounted for 25 percent of arrests.

- Violent crimes, including homicide, rape, and robbery, accounted for 25 percent of all juvenile felony arrests. There were a total of 171 juvenile arrests for homicide in 2005, less than one-half of 1 percent of all juvenile felony arrests.

What Happens to Juvenile Offenders?

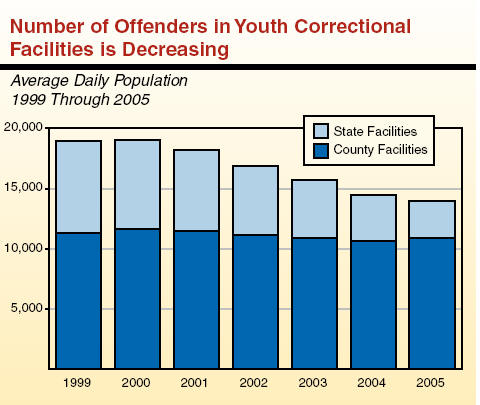

-

The population of juveniles incarcerated in state or county facilities has decreased every year since 2000 from about 19,000 in 2000 to 14,000 in 2005, a 27 percent decrease.

-

Since 1999, the number of juveniles incarcerated in county facilities has declined by about 4 percent, from about 11,400 to 10,900.

-

The number of juveniles incarcerated in state facilities declined by about 60 percent between 1999 and 2005, from almost 7,600 in 1999 to about 3,000 in 2005.

-

The decline in juvenile incarceration is due largely to the decline in juvenile arrest rates and the implementation by counties of more alternatives to incarceration, such as placements in home supervision and group homes.

Key Topics in Juvenile Justice

Reforming the Division of Juvenile Justice

Farrell Lawsuit.

In January 2003, a lawsuit,

Farrell v. Allen, was filed against the Department of Youth Authority (as noted above, later renamed DJJ), contending that it failed to provide adequate care and effective treatment programs to youthful offenders (known as “wards”) incarcerated in state facilities. In November 2004, the administration agreed to plaintiffs’ demand that the state develop and implement remedial plans that addressed operational and programmatic deficiencies identified by court experts in six areas: education, sex behavior treatment, disabilities, health care, mental health, and ward safety and welfare. The overarching goal of these reforms is to transform the state’s youth correctional system into a “rehabilitative model” of care and treatment for youthful offenders.

Remedial Plans. During the next several years, DJJ is required to implement reforms consistent with the remedial plans. The first priority is to reduce the level of ward-on-ward and ward-on-staff violence in the correctional facilities in order to create a suitable environment for treatment and rehabilitation. To do this, the remedial plan requires the division to hire various additional staff, particularly security officers, and place them in living units that will be limited to no more than 38 wards. Another priority is to train staff on treatment practices that have been successfully implemented in other states such as Texas and Washington. These “best practices” are intended to improve treatment for substance abuse, mental illness, and sex-offender behavior.

Fiscal Impact. Implementing these reforms will be a long-term project. States such as Colorado report that it can take ten years or more to transform an underachieving youth correctional system into a successful rehabilitative model. Current estimates are that the implementation of these reforms will cost the state more than $100 million annually once fully implemented. This amounts to approximately a 25 percent increase in state spending on juvenile corrections.

Defining State and Local Responsibilities for

Juvenile Offenders

Current Local Role. As noted earlier, the juvenile justice system is primarily a local responsibility. Counties currently are responsible for more than 98 percent of all juvenile offender cases, typically through their probation departments, which provide incarceration, rehabilitation services, and community supervision. The state, through DJJ, provides these services for the relatively small number of remaining juvenile offenders who generally have committed crimes that are more serious in nature or have repeatedly failed to respond to local juvenile justice programs.

Current State Role. The state’s role in the juvenile justice system has been changing in recent years. The number of offenders held in the state facilities operated by DJJ has dropped dramatically, as shown on page 58, from about 7,600 wards in 1999 to about 3,000 in 2005. (The number of wards in state facilities is even lower now and still dropping.) Meanwhile, the state has invested significant additional funding in recent years to improve its institutional programs (largely in response to litigation over conditions in DJJ facilities), as well as to expand grants to counties for community services to prevent at-risk youth from being involved in criminal activities.

Future Roles. What roles the state and the counties should play in the juvenile justice system in the future-both in terms of funding and in setting overall policy governing the state’s approach to dealing with juvenile offenders-is the subject of continuing policy debate and discussion among criminal justice experts and governmental officials. One perspective is that, since criminal justice policies are often established by actions at the state level (such as by voter approval of Proposition 21 in 2000, which expanded the types of cases for which juveniles can be tried in adult court), the state is obligated to retain a significant role in funding and operating youth institutions as well as parole supervision of wards who have been released into the community. In our past analyses of these issues, however, we have noted that, upon their release from state facilities, most juvenile offenders return to their home communities and that these local communities thus have a significant interest in their future behavior. Counties also already administer many of the programs these individuals need to reduce their likelihood of recidivism, such as drug and alcohol treatment programs and mental health treatment.

Accordingly, one option is for part or all of the operation of existing DJJ institutions as well as parole supervision responsibilities to be shifted to counties, along with the resources to continue these programs. The Governor’s

2007-08 budget plan proposes to shift part of the DJJ institutional population-primarily lower-level juvenile offenders-to counties along with block grant funding to offset the additional cost of this shift.

Chapter 6:

The Costs of Crime And the Criminal Justice System

A number of studies have attempted to estimate the total direct and indirect costs of crime to government and society. The estimates resulting from these studies have varied, but generally conclude that nationwide costs of crime range from the tens to hundreds of billions annually.

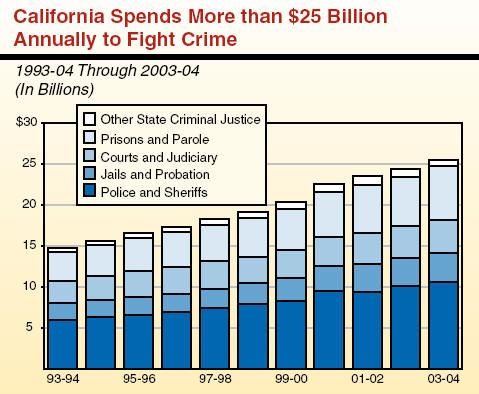

Some components of the cost of crime can be readily estimated. For example, in 2003-04, California spent more than $25 billion to fight crime, which included costs for police, prosecution, courts, probation, and incarceration (as shown on page 63). This amount was primarily funded by the state and local governments.

Other costs cannot be easily measured. For example, many crimes-such as fraud, embezzlement, or arson-often go undetected or unreported and thus their costs to society are not fully captured in some estimates. Also, some costs are difficult to estimate because the costs are “transferred” from one party to another. For example, the costs of crime in terms of the loss of goods and services may be transferred from manufacturers and retailers to consumers as the price of their products are adjusted to reflect the costs for crime prevention activities or losses from crime.

This chapter provides information on the costs of the criminal justice system. This includes data on the costs to state and local governments over time, criminal justice personnel compared to other states, and state expenditures on youth and adult corrections. The chapter also discusses two topics related to the costs of crime: (1) the cost of crime to society and (2) cost-effective crime prevention strategies.

What Does It Cost to Operate the

California Criminal Justice System?

- Total state spending on criminal justice grew from about $15 billion in 1993-94 to more than $25 billion in 2003-04 (the most recent complete data available).

- Criminal justice spending grew by about 6 percent annually during this period. Spending on prisons and parole grew slightly faster than other criminal justice programs, at a rate of 7 percent annually.

- Local governments support about 62 percent of total annual criminal justice costs, including approximately $11 billion for police and sheriffs.

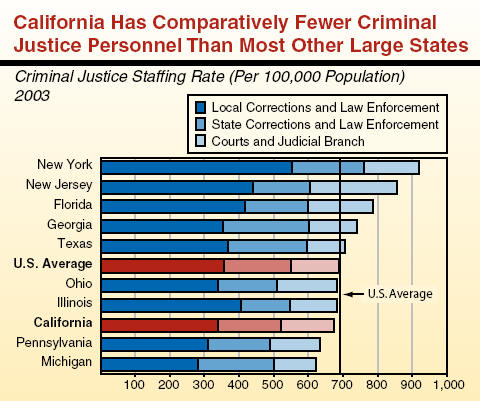

- In 2003, California had about 240,000 personnel (as measured by the number of full-time equivalent staff) working in the state and local criminal justice system, the highest total of any state.

- However, California ranked eighth among the ten largest states in terms of the number of criminal justice personnel per population. Specifically, California had less than 700 criminal justice staff per 100,000 people, slightly less than the U.S. average. Of these ten states, New York had the most criminal justice personnel per capita, with 900 per 100,000 population.

- One-half of California criminal justice personnel worked in local corrections and law enforcement, 27 percent worked in state corrections and law enforcement, and 23 percent worked in the court system.

- State spending for criminal justice reached $14 billion in 2006-07, an average annual increase of about 10 percent since 1996-97. This growth rate outpaced that for total state spending and was only eclipsed by the growth in funding for resources/environmental programs.

- Most of the increase in spending in criminal justice programs is due to increases in salary costs, as well as court-ordered mandates to improve parts of the prison system, such as medical care. The prison

inmate population grew at an average annual rate of 2 percent over this period.

- Spending on criminal justice programs takes up a greater share of total state expenditures today than a decade ago, increasing from about 6 percent of total expenditures in 1996-97, to about 7 percent in 2006-07. Spending for corrections makes up two-thirds of total state criminal justice expenditures in the current year.

|

California Annual

Costs to

Incarcerate an Inmate in Prison |

|

2006‑07 |

|

Type of Expenditure |

Per Inmate Costs |

|

Security |

$19,561 |

|

|

|

|

Inmate Health Care |

$9,330 |

|

Medical care |

$6,186 |

|

Psychiatric services |

1,751 |

|

Pharmaceuticals |

977 |

|

Dental care |

416 |

|

Operations |

$6,216 |

|

Facility operations (maintenance,

utilities, etc.) |

$4,377 |

|

Classification and inmate

services |

1,582 |

|

Reception, testing, assignment |

240 |

|

Transportation |

17 |

|

Administration |

$3,351 |

|

|

|

|

Inmate Support |

$2,527 |

|

Food |

$1,437 |

|

Inmate activities and canteen |

485 |

|

Clothing |

309 |

|

Inmate employment |

296 |

|

Employment/Training |

$2,053 |

|

Academic education |

$949 |

|

Substance abuse programs |

823 |

|

Vocational training |

281 |

|

Miscellaneous |

$246 |

|

Total |

$43,287 |

|

|

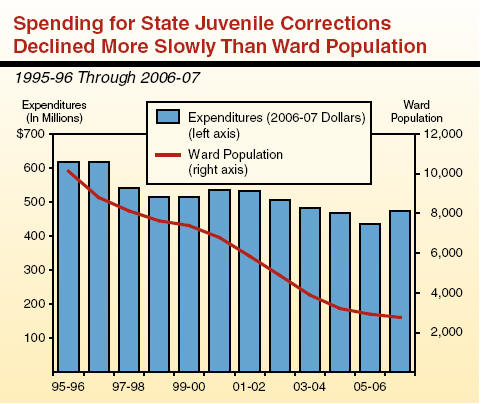

- Adjusting for inflation, state expenditures for juvenile corrections declined by about $137 million or 22 percent since 1995-96.

- The ward population declined much more quickly over that period, falling from about 10,000 wards in 1995-96 to fewer than 3,000 projected in 2006-07, a decrease of more than 70 percent. This decrease is due primarily to the decline in juvenile arrest rates and the implementation by counties of more alternatives to incarceration, such as placements in home supervision and group homes.

- The annual cost of housing a ward in a state facility is estimated to be approximately $180,000 in 2006-07. These costs are substantially higher than the state costs to house adult offenders, primarily because juvenile facilities have higher staffing ratios and provide more education and rehabilitation programs than adult facilities.

Key Topics in

Criminal Justice System Spending

The Cost of Crime to Society