May 2007

Reforming California’s Instructional Material Adoption Process

The Supplemental Report of the 2006 Budget Act directed our office to examine instructional material costs and assess California’s process for adopting kindergarten through eighth grade (K-8) instructional materials. This report details our findings. Most importantly, we identify several shortcomings with California’s K-8 adoption process. To address these shortcomings, we recommend the Legislature adopt a package of six reforms designed to lower instructional material costs, expand school district choice, and enhance program effectiveness.

Executive Summary

In recent years, the Legislature has expressed growing concern with the rising cost of instructional materials in California. In response, it directed our office to compare spending trends in California with other states. Examining data from 1993 through 2003 (the most recent year for which consistent state data are available), we found that inflation-adjusted kindergarten through twelfth grade (K-12) instructional material spending in California increased more than $100 per pupil, or almost 80 percent, over this period. This was about double the rate of growth of other states and about four times the rate of growth for “all other” K-12 support spending. Despite such a sizeable increase, California at the end of this period still spent slightly less per pupil on instructional materials than the national average.

In recent years, the Legislature also has expressed growing concern with the state’s process for adopting K-8 instructional materials. In response, it directed our office to explore the relationship between instructional material review processes and state spending. We found that states with state-level adoption processes consistently spend slightly more than states with local-level selection processes. However, after controlling for such factors as state demographics, we found adoption states spend less than local-selection states. This means adoption states might be spending more as a result of other factors. For example, adoption states tend to serve larger percentages of low-income students and English learners (ELs), which, in turn, is linked to higher per-pupil spending.

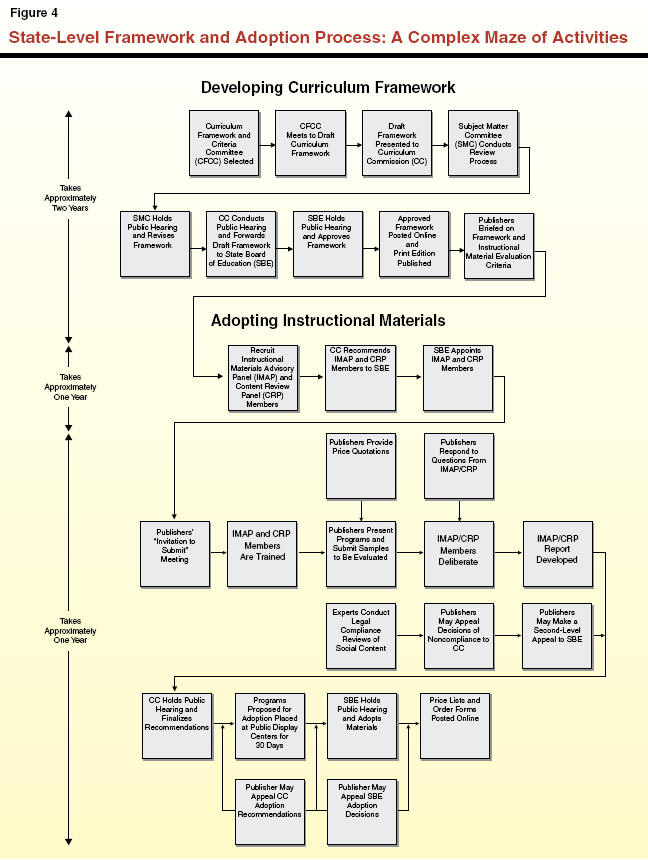

To gain a better understanding of California’s K-8 adoption process, we reviewed California law and regulations, examined various other state and industry documents, and interviewed various individuals—including state administrators, program experts, publishers, and representatives of state-level advocacy groups, as well as staff at school districts and county offices of education. The state’s adoption process is a complex maze of activities—involving four sets of evaluation criteria and various expert panels, two curriculum committees, a Curriculum Commission, and two state agencies, as well as advocates and the general public. Just about when the process is fully implemented at the local level, districts must begin the process anew. We found this highly prescriptive process can be linked to less competition among publishers, more limited district choice, higher cost, questionable quality, and little useful information.

To address these shortcomings, we recommend the Legislature adopt a package of six reforms designed to lower cost, expand district choice, and enhance program effectiveness. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature reform the existing system by: (1) using fewer sets of evaluation criteria, (2) streamlining the review process, (3) offering districts voluntary extension of already adopted materials for up to two consecutive cycles, (4) shifting focus back to core materials by requiring ancillary materials to be priced and sold separately, (5) ensuring greater predictability by linking annual price increases to a specified inflationary index, and (6) enhancing the quality and availability of information by collecting better information from expert reviewers and making that information available to the public.

Introduction

In recent years, the Legislature has expressed concern with the rising cost of instructional materials as well as the process the state has constructed to adopt these materials for use in elementary and middle schools. Stemming from these concerns, the Legislature adopted language in the Supplemental Report of the 2006 Budget Act that directed our office to compare K-12 instructional material costs in California with other states over time. In doing so, it asked us to explore how states’ instructional material review processes, academic content standards, and student diversity might be affecting these costs. In addition, we were directed to make recommendations for lowering the cost of instructional materials in California.

In the first half of this report, we explore trends in K-12 textbook costs and instructional material spending. In the second half of the report, we focus specifically on California’s adoption process for K-8 instructional materials—first identifying the shortcomings of this system and then offering a package of recommendations designed to reduce the cost of instructional materials, expand school district choice, and enhance program effectiveness.

Spending Trends

This section identifies general trends in K-12 textbook costs and instructional material spending and then explores how various factors might be affecting these trends.

General Trends

Below, we examine California textbook cost trends using data compiled by the California Department of Education (CDE) as well as cross-state spending trends using data compiled by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

Costs of Textbooks in California Has Risen Sharply Since 1990. In a 2005 report, CDE tracked data on the average cost of fourth grade reading/language arts textbooks from 1990 through 2005. In 1990, the average cost of one of these fourth grade textbooks was $18. By 2005, the average cost was more than $50. Even adjusting for inflation, the average cost almost doubled over this time period. A study conducted on behalf of publishers also suggests that sizeable cost increases are likely to continue over the next several years. For example, the study estimated that the average cost of a fourth grade textbook in the upcoming 2008 reading/language arts adoption cycle would be approximately $85.

Little Cross-State Data on Textbook Costs. Each year, NCES collects data on state expenditures for K-12 education. Unfortunately, NCES did not begin collecting data on state textbook expenditures until 2003-04 (with only 38 states then reporting data in that category). Given this limitation, we reviewed other information sources, including a private firm that collects data for publishers. Unfortunately, the last year this firm collected data separately for textbooks was in 2000-01. In short, we were unable to find consistent cross-state data on textbook costs.

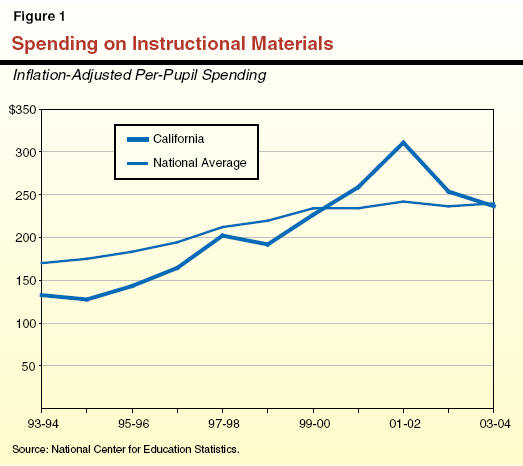

Cross-State Data on Instructional Material Spending Send Mixed Messages. The NCES, however, has collected data for many years on states’ instructional material spending (which includes spending for textbooks, classroom teaching supplies, audiovisual supplies, and periodicals). We reviewed spending trends from 1993-94 through 2003-04 (the most recent year for which NCES data are available). Over this period, inflation-adjusted per-pupil spending on instructional materials in California grew from $133 to $237—an increase of $104 or 78 percent (see Figure 1). The average annual rate of change in California was 5.9 percent. By comparison, average spending on instructional materials in other states grew from $171 to $240 per pupil—an increase of $69 or 41 percent. The average annual rate of change in other states was 3.5 percent. Thus, spending in California grew at almost twice the rate of other states over this period. Nonetheless, at the end of this period, California still was spending slightly less than the national average. Whereas it was ranked 44th among the 50 states in per-pupil instructional spending in 1993-94, it ranked 25th in 2003-04.

Spending on Instructional Materials Has Outpaced All Other Spending. To disentangle instructional material spending trends from any underlying trends in spending for K-12 education, we also examined all other support spending (total K-12 support spending less instructional material spending). In both California and other states, inflation-adjusted all other support spending grew by about 20 percent from 1993-94 through 2003-04, reflecting an average annual rate of increase of less than 2 percent. These increases are substantially less than the increases in instructional material spending. This could mean that states felt they were underspending on instructional materials in the early 1990s and made special efforts to increase spending over the next ten years. Alternatively, it could mean that changes in state policies and/or publisher practices were driving up instructional material costs much more sharply than other K-12 education costs.

Instructional Material Review Policies

In an effort to understand what might be causing such significant increases in instructional material spending, we explored the relationship between states’ spending and their instructional material review policies.

Two Basic Processes Used to Select Instructional Materials. Every state has policies regarding the selection and purchase of K-12 instructional materials. To select materials, 20 states use a state-level process. Most states that use such a process formally adopt a list of approved instructional materials and districts must purchase materials from this list. A few states, however, adopt lists of “suggested” or “recommended” materials and/or grant districts some discretion to purchase materials not on the state lists. In contrast to these adoption states, 30 states use a local-level selection process. In these states, districts may purchase any instructional materials of their choosing. Figure 2 shows the instructional material review process each state currently uses. California is unique among the 50 states in using both processes—it uses a state-adoption process for K-8 materials and a local-selection process at the high school level.

|

Figure 2

Majority of States Use Local-Selection Process |

|

Local Selection (30) |

State Adoption (20) |

|

Alaska |

Alabama |

|

Arizona |

Arkansas |

|

Colorado |

Californiaa |

|

Connecticut |

Florida |

|

Delaware |

Georgia |

|

Hawaii |

Idaho |

|

Illinois |

Indiana |

|

Iowa |

Kentucky |

|

Kansas |

Louisiana |

|

Maine |

Mississippi |

|

Maryland |

New Mexico |

|

Massachusetts |

North Carolina |

|

Michigan |

Oklahoma |

|

Minnesota |

Oregon |

|

Missouri |

South Carolina |

|

Montana |

Tennessee |

|

Nebraska |

Texas |

|

Nevada |

Utah |

|

New Hampshire |

Virginia |

|

New Jersey |

West Virginia |

|

New York |

|

|

North Dakota |

|

|

Ohio |

|

|

Pennsylvania |

|

|

Rhode Island |

|

|

South Dakota |

|

|

Vermont |

|

|

Washington |

|

|

Wisconsin |

|

|

Wyoming |

|

|

|

|

a

California has a state-adoption process for K-8

materials and a local-selection process for high school materials.

|

|

Source: Education Commission of

the States. |

Adoption States Spend Slightly More on Instructional Materials but Cause Unclear. Because many states did not institutionalize their existing adoption processes until the late 1990s, we confined our analysis in this section to the latter part of our data set (1998-99 through 2003-04). Over this period, adoption states consistently spent, on average, slightly more per pupil on instructional materials than states with local-selection processes. In 1998-99, for example, adoption states spent, on average, $227 per pupil on instructional materials whereas local-selection states spent, on average, $215 per pupil. Similarly, in 2003-04, adoption states spent $249 per pupil compared to $234 per pupil in local-selection states. Although adoption states spent more per pupil than local-selection states, the rate of spending increases over this period were about the same for both groups (1.8 percent). Moreover, when controlling for other factors (such as state demographics), we found adoption states spend less than local-selection states. This means adoption states might appear to be spending more only because they are correlated with other “high-spending” factors, such as being states that serve more low-income and EL students.

No Firm Findings Relating to Type of Adoption System. We also examined differences in the types of adoption systems states use. Specifically, we classified adoption states as either “strict-adoption” states, in which states formally adopt lists of approved instructional materials and districts must purchase materials from those lists, or “flexible-adoption” states, in which states approve lists of suggested or recommended materials and/or districts can purchase materials not on the state lists. Strict-adoption states, on average, spent more per pupil on instructional materials than flexible-adoption states every year from 1998-99 through 2003-04. The differences, however, are much larger during the first half of the period. In 1998-99, for example, strict-adoption states spent, on average, $237 per pupil on instructional materials whereas flexible-adoption states spent, on average, $213 per pupil. By comparison, in 2003-04, strict-adoption states spent $250 per pupil compared to $246 per pupil in flexible-adoption states. Without additional years of data, the relationship between the type of adoption system and instructional material spending remains inconclusive.

K-12 Content Standards

In addition to exploring the relationship between states’ spending and their instructional material review policies, we compared spending trends in California with states that have similar K-12 content standards. California commonly is recognized as having the most rigorous K-12 content standards in the country. The Fordham Foundation, which periodically ranks all 50 states according to the quality of their academic standards, ranked California second in 1998 and first in both 2000 and 2006. Only California, Arizona, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Virginia ranked in the top ten in each of the three review cycles.

Relationship Appears Weak. We examined the 1998, 2000, and 2003 Fordham Foundation rankings. In 1998 and 2000, state rankings were based on the rigor of content standards in all core subjects whereas the 2003 rankings were based only on content standards in history. (We were unable to use the 2006 Fordham rankings because NCES expenditure data were not available for that year). Although counterintuitive, the ten states with the most rigorous standards spent, on average, somewhat less on instructional materials than other states. The difference, however, has steadily narrowed over time. In 1998-99, states with the most rigorous standards spent, on average, $48 per pupil less than other states whereas they spent $15 less per pupil in 2000-01 and $13 less per pupil in 2003-04. Conducting several other types of statistical analyses, the relationship between states’ content standards and spending on instructional materials appears quite weak. This means states likely could strengthen or weaken their content standards without a major or direct effect on instructional materials costs.

K-12 Student Populations

As directed, we also compared California’s spending with states that serve similar students yet have higher achievement. Given California’s diversity, no other state makes for a particularly good comparison. Nonetheless, California commonly is compared to Texas, Florida, and New York. As Figure 3 shows, California has a notably higher percentage of EL students and a slightly higher percentage of low-income students than these three other states. It also has lower scores on national standardized tests for fourth and eighth graders in reading and mathematics. Of the four states, only New York typically scores above the national average in both subjects and both grades. Also shown in Figure 3, California spent more per pupil on instructional materials than Florida but somewhat less than New York and significantly less than Texas. Over the decade, however, California increased its spending at almost triple the rate of Texas as well as at a notably higher rate than Florida and New York.

|

Figure 3

Comparing California With Other Large States |

|

(2003) |

|

State |

English Learners |

Low-Income Studentsa |

Test Scoresb |

Per-Pupil Spendingc |

Average Annual Rate Of Changed |

|

California |

25% |

47% |

251 |

$237 |

5.9% |

|

Florida |

8 |

45 |

257 |

202 |

4.7 |

|

New York |

13 |

43 |

264 |

260 |

4.6 |

|

Texas |

16 |

45 |

259 |

322 |

2.0 |

|

|

|

a

Reflects students eligible for federal free and

reduced-price meal programs. |

|

b

Reflects average score on the National Assessment of

Educational Progress for eighth graders in reading

(scale of 0 to 500). |

|

c

Reflects per-pupil instructional material spending. |

|

d

Reflects changes in per-pupil spending between

1993-94 and 2003-04. |

K-12 Student Demographics Do Affect Spending. We also conducted a number of other statistical analyses using data from all 50 states on instructional material spending, percentage of EL students, and percentage of students who are eligible for free or reduced-price meals (a proxy for low-income students). Controlling for various factors, we found that states with higher percentages of EL and low-income students typically spend more per pupil on instructional materials than states with lower percentages of these students. Specifically, for every 1 percent increase in a state’s EL population or 1 percent increase in its low-income student population, we found per-pupil spending on instructional materials increased by a few dollars. This could mean states with more diverse populations spend more on targeted supplemental materials.

A Closer Look at California’s Adoption Process

The available quantitative data do not tell a clear story. On the one hand, instructional material spending has been increasing in California and across the nation far in excess of inflation and enrollment growth. Despite such steep increases, spending in California still is slightly below the national average. Moreover, the data suggest that state demographics affect spending but the rigor of state content standards seems to have little, if any, effect on spending. Furthermore, if instructional material review processes matter, the available data are too crude to suggest exactly how they matter.

To gain a better understanding of what might be happening in California, this section focuses specifically on California’s K-8 adoption process and its potential impact on instructional material costs. We reviewed California law and regulations, examined various other state and industry documents, and conducted more than 20 interviews with state administrators, program experts, publishers, and leaders of professional associations, as well as staff at school districts and county offices of education. These interviews helped us uncover inefficiencies in California’s adoption process, identify factors likely to be driving up the cost of instructional materials, and develop recommendations designed to lower these costs.

Below, we describe California’s existing K-8 adoption process. As shown in Figure 4, this process consists of a complex maze of activities.

Instructional Materials Evaluated Based on Four Sets of Criteria

Instructional materials in California are evaluated based on four sets of criteria: (1) alignment with academic content standards, (2) consistency with subject-specific curriculum frameworks, (3) satisfaction of instructional material evaluation criteria, and (4) portrayal of social content.

Evaluation Based on Academic Content Standards. Beginning in the mid-1990s, the State Board of Education (SBE) began adopting content standards for every grade in English language arts, mathematics, history/social science, and science, as well as visual and performing arts, physical education, foreign language, and health education. The content standards delineate the specific knowledge and skills students should acquire in each subject. For example, California has 53 standards for fourth grade English language arts and 55 standards for fourth grade mathematics. A 21-member advisory committee made up of parents, teachers, administrators, business leaders, and academics develops the standards and presents them to SBE for approval. These content standards, coupled with performance standards, are designed to be the core of the state’s accountability system. They also are designed to be the core of the instructional material evaluation process.

Also Evaluated Based on Curriculum Frameworks. The objective of a curriculum framework is to provide guidance on how to teach each content standard in a given subject. The frameworks are extensive documents that specify: the instructional approaches needed for students to master the standards, appropriate student assessments, pedagogical strategies for working with all types of students, appropriate professional development, and requirements for instructional materials. The current reading/language arts and mathematics curriculum frameworks each contain almost 400 pages of discussion and specifications. Publishers are required to base their instructional materials on these frameworks.

. . . And Program/Evaluation Criteria. In addition to addressing each academic content standard and the associated state curriculum framework, instructional materials must meet certain program and evaluation criteria to become adopted. The program criteria delineate the specific types of programs that publishers may submit. For example, SBE is allowing three types of programs to be developed for the 2007 mathematics adoption: (1) basic grade-level programs (K-8), (2) intervention programs for struggling students (grades 4-7), and (3) an algebra readiness program for eighth grade students who are not yet ready for algebra. Each type of program is associated with certain requirements. For example, a basic grade-level mathematics program must consist of a comprehensive curriculum that provides instructional content for at least 50 minutes per day. Publishers may submit instructional materials for one or more of the above types of programs in one or more of the specified grade levels. If a set of instructional materials (typically including a student textbook, student workbooks, and teacher guide) meets all program requirements, it then is evaluated based on five other criteria—alignment with standards, organization, student assessments, universal access (including instructional strategies that address the full range of possible learning needs), and instructional planning and support. These program and evaluation criteria form the core of the document the state provides to publishers toward the beginning of each adoption cycle. These documents—typically running between 150 and 200 pages—also are filled with a myriad of minute specifications.

. . . And Social Content. In addition to meeting the requirements of the content standards, curriculum frameworks, and evaluation criteria, state law requires instructional materials to portray certain social content. For example, state law specifies that instructional materials must portray the contributions of both men and women in professional, vocational, and executive roles; Native Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans, Asian Americans, and European Americans; and entrepreneurs and labor. The materials also must encourage thrift, fire prevention, and the humane treatment of animals and people, and discuss (when appropriate) the effects on the human system of the use of tobacco, alcohol, narcotics, restricted dangerous drugs, and other dangerous substances.

Each Adoption Cycle Involves Seemingly Countless Players

California’s existing adoption process involves a slew of parties—many of whom perform the same functions. Specifically, the process involves various expert panels, two curriculum committees, a Curriculum Commission, and two state agencies, as well as interested stakeholders and the general public.

Involves Expert Panels. The bulk of the actual review of instructional materials is undertaken by two expert panels—the Instructional Materials Advisory Panel (IMAP) and the Content Review Panel (CRP). Most IMAP members are K-12 teachers but the panel may include school administrators, curriculum experts, and parents. Members of CRP are subject matter experts, often with doctoral degrees. All IMAP and CRP members receive training on the adoption criteria prior to individually reviewing submitted materials. Whereas CRP members focus almost solely on academic content, IMAP members focus on academic content as well as the other sets of evaluation criteria. Members of the IMAP and CRP are selected separately for each adoption cycle and volunteer their time. The SBE appoints the members upon recommendation of the Curriculum Commission. Districts absorb costs for any of their teachers who serve on an expert panel.

Also Involves Two Committees. As part of the curriculum frameworks process, SBE appoints a Curriculum Framework Criteria Committee (CFCC). The CFCC consists primarily of current K-8 teachers but may include some noneducators. All CFCC members are to have subject matter expertise and professional experience with effective educational programs. The CFCC’s primary task is to develop a draft framework and submit it to the Curriculum Commission for consideration, after which a Subject Matter Committee (SMC) reviews the draft. The SMC consists of commission members who have expertise or interest in the relevant subject. This committee holds a public hearing to discuss the framework, makes revisions, and then submits it to the commission.

. . . And the Curriculum Commission. The Curriculum Commission, established in state law, is an 18 member advisory board to SBE. Commissioners tend to be recognized authorities in a specific subject matter, professors, curriculum experts, K-12 teachers, or community members. The commission advises SBE on the K-12 curriculum frameworks and K-8 instructional materials. In doing so, it serves as a kind of intermediary between the field experts and SBE. The commission holds a public hearing on a framework after the SMC hearing and before the SBE hearing on the framework. It also holds a public hearing on instructional materials after the IMAP/CRP members develop their evaluation report and before SBE holds a hearing to adopt the materials.

. . . And CDE. The department has a Curriculum Frameworks and Instructional Resources Division that provides various support and administrative services. Its activities include developing the “Publishers Invitation to Submit” document, contracting with county offices of education to assist with legal and social compliance reviews, supporting the commission and SBE in their instructional material activities, and administering the Instructional Materials Block Grant (the primary funding source for the purchase of K-12 materials).

. . . And SBE. The board approves finalized curriculum frameworks and makes final instructional materials adoption decisions. State law requires SBE to adopt at least five sets of basic instructional materials at each grade level (K-8) in each of seven subjects (reading/language arts, mathematics, history/social science, science, visual/performing arts, foreign language, and health education). Exceptions are made, however, if fewer than five sets of materials are submitted or if SBE finds that fewer than five submittals meet the four sets of evaluation criteria.

. . . And Advocates as Well as the General Public. In addition to involving interested parties through the expert panels, committees, commission, and board, advocates have six other opportunities to be involved in the framework and adoption processes. Stakeholders may present oral and written feedback before the SMC as it develops the draft curriculum framework, before the whole commission as it finalizes recommendations on the framework, and before SBE as it makes final decisions on the framework. Similarly, stakeholders may present oral and written feedback before the commission as it finalizes its recommendations on instructional materials and before SBE as it makes final adoption decisions. Between these hearings, any interested party also may visit any of 21 Learning Resource Display Centers located throughout the state to view materials proposed for adoption. Furthermore, publishers can appeal decisions made at various stages of the adoption process.

Just When Fully Implemented, Process Starts All Over Again

California’s separate six-year adoption cycles for seven academic subjects requires the state to conduct review activities every year and results in school districts having to buy new instructional materials in at least one subject virtually every year.

State Engaged in Framework/Adoption Activities Every Year. As shown earlier in Figure 4, development and release of a state curriculum framework takes approximately two years, recruiting experts to review instructional materials takes about one year, and actually undertaking the instructional material evaluation process takes another year. The state undergoes this process separately for each of seven subjects. As shown in Figure 5, the state has structured the process such that it is engaged in some framework and/or adoption activities every year.

|

Figure 5

Major

State Activities by Year and Subject |

|

|

State Activities: |

|

2005 |

·

Approved mathematics framework.

·

Adopted history/social science

materials. |

|

2006 |

·

Approved reading/language arts

framework.

·

Adopted science materials.

·

Adopted visual/performing arts

materials. |

|

2007 |

·

To adopt mathematics materials. |

|

2008 |

·

To approve physical education

framework.

·

To adopt reading/language arts

materials. |

|

2009 |

·

To approve foreign language framework.

·

To approve history/social science

framework. |

|

2010 |

·

To approve health framework.

·

To approve science framework. |

|

2011 |

·

To approve mathematics framework.

·

To adopt foreign language materials.

·

To adopt history/social science

materials. |

|

2012 |

·

To approve visual/performing arts

framework.

·

To adopt health materials.

·

To adopt science materials. |

School Districts Required to Purchase New Instructional Materials Virtually Every Year. After state adoption decisions have been made for a particular subject, school districts must purchase K-8 materials within 24 months. Given SBE adopts materials in some subject almost every year and, in some years, adopts materials for more than one subject, school districts must purchase new K-8 instructional materials virtually every year. Prior to purchasing new materials, school districts typically pilot materials for one year. After purchasing new materials in a particular subject, districts invest substantial effort in training teachers on the new materials while they are in use. Districts typically train only a portion of their teachers each year and report taking up to three years to complete all associated teacher training. This means school districts have only one or two years after fully implementing a set of instructional materials before the state requires them to begin the process anew. Moreover, they too undergo this process separately for each of seven subjects. In our interviews with district and county staff, representatives expressed frustration with such a process. They were frustrated they had to purchase new instructional materials for some subjects every year. They were frustrated they sometimes had to purchase new instructional materials for higher-cost core subjects in consecutive years. (For example, school districts had to begin purchasing science materials in 2006 and will have to begin purchasing mathematics materials in 2007 and reading/language arts materials in 2008.) They also were frustrated that the frequency of the process meant they had to purchase “new” materials just as their professional development efforts seemed to be coming to fruition and teachers were becoming expert in using the “old” materials.

Highly Prescriptive Process Linked With Poor Outcomes

Presumably, the intent of a state-level adoption process is to ensure high quality at low cost. Instead, California’s highly prescriptive process can be linked to less competition among publishers, more limited district choice, higher cost, questionable quality, and little useful information.

Less Competition. Over the last decade, many smaller publishers have either shut down or merged with larger publishers, resulting in an oligopoly in the California textbook market. Today, four publishing companies dominate the instructional materials market. Given California’s extensive set of instructional material evaluation criteria, publishers claim they incur high upfront research and development costs. In our interviews, representatives of the Association of American Publishers (AAP) stated that publishers also view California as a high-risk market because large upfront investment is needed yet no guarantee of eventual state adoption is provided. Given such high upfront costs and high risk, few small- and mid-sized publishers, to date, have been able to develop California materials.

. . . And Fewer Local Choices. Over the last decade, this trend within the publishing industry has translated into fewer choices for school districts. For example, in 1988, SBE approved 13 reading/language arts instructional material packages. By comparison, in the 2002 reading/language arts adoption, only three publishers even submitted K-3 materials, and SBE approved only two of them. In our interviews, district and county staff as well as state-level education advocacy groups voiced concern with the limited number of instructional material options available to them.

. . . And Very, Very Lengthy Student and Teacher Editions. Representatives of AAP provided us with data for the only set of reading/language arts instructional materials adopted in both the 1988 and 2002 cycles. As shown in Figure 6, the 2002 grade 1 student edition was more than 1,000 pages longer than the 1988 edition—more than doubling in length. Even more dramatic, the 2002 teacher edition was more than 6,000 pages longer than the 1988 edition—increasing more than sevenfold.

|

Figure 6

More

Specifications, More Pages Grade 1 Reading/Language Arts |

|

|

1988 |

2002 |

Change |

|

Number |

Percent |

|

Program specifications (pages) |

59 |

301 |

242 |

410% |

|

Grade 1 student edition

(pages) |

792 |

1,808 |

1,016 |

128 |

|

Grade 1 teacher edition

(pages) |

848 |

6,913 |

6,065 |

715 |

|

|

|

Source: Strategic Education

Services. |

. . . And Higher Cost. With so few publishers developing K-8 materials in California, coupled with a state law that requires publishers to offer textbooks at a set price statewide, publishers have come to distinguish themselves by offering special “gratis” items (items offered free of charge). Technically, a gratis item may be virtually any product that has some instructional content. (Gratis items may not include equipment, such as overhead projectors and laptops.) Given publishers presumably intend to cover their costs, core materials likely are being overpriced in an effort to cover the cost of the ancillary materials that publishers are offering free of charge. In addition to inflating the price of core instructional materials, some district representatives believe publishers provide so many ancillary materials that teachers can not practically put them all to use. A comparison of 1988 and 2002 price lists, which are maintained by CDE and include the name and price of each textbook and ancillary product approved for use in the state, support these claims. In 1988, the price list for the 13 adopted sets of instructional materials was 12 pages. In 2002, the price list for the 2 adopted sets of materials was 44 pages.

Unconstrained Mid-Cycle Price Increases Exacerbate Matters. State law currently allows publishers to increase the price of their instructional materials every two years within an adoption cycle. No limit is placed on how much prices may be raised mid-cycle. These price increases affect the cost of lost and worn books as well as the cost of annual workbooks. Given the initial investment in a set of instructional materials is significant, districts essentially are captive to those materials throughout the six-year adoption cycle. This implies they are virtually compelled to pay whatever mid-cycle price increases a publisher might impose.

All This and Not Necessarily Better Programs. In our interviews, several state-level advocacy groups also believed the Curriculum Commission tended to base its recommendations on pedagogical preferences rather than standards alignment. Some groups have expressed their concerns to SBE. For example, in a letter to SBE, the California Science Teachers Association (CSTA) claimed it had witnessed “one or two Commissioners convince the entire commission to ignore the months-long work of the IMAPs and CRPs and reject a particular program for what appear to be personally based reasons . . . [T]he Commissioners pedagogical philosophy is heavily skewed.” Similarly, in a letter to SBE, the Association of California School Administrators) stated, “the Commission retains too much authority . . . and should focus more on its advisory role and less on the mechanics and politics of the adoption process.” Furthermore, in our interviews with former IMAP and CRP members, they too expressed frustration, believing some Commissioners based decisions on pedagogy rather than alignment with content standards. In short, if these claims are true, California’s highly prescriptive process might not be guaranteeing high-quality instructional materials.

. . . Nor Useful Information. The current system also produces little information about instructional material evaluations. Despite spending up to 90 hours reviewing a set of instructional materials, the IMAP and CRP members we interviewed thought their evaluation efforts did not result in good information about the quality of those materials. They stated this was because the state’s evaluation matrix did not allow them to give critical feedback—such as being able to cite the strengths and weaknesses of the materials they reviewed. Instead, evaluators currently are asked only to check whether a set of materials meets each requirement. They do not have an opportunity to share how well it covers a particular content standard, how well it is organized, or how well it addresses the needs of EL students. In a letter to CDE, a former IMAP reviewer complained that “cursory information was considered to be sufficient.” In short, under the state’s existing evaluation process, valuable information on the quality of instructional materials is being lost.

School Districts Largely Duplicate the Review Process. As a result, districts are given virtually no information they can use to compare adopted materials. As a result, school districts typically spend one school year reevaluating and piloting state-adopted instructional materials. To do so, they often compensate teachers for work outside of their normal work hours. In the end, districts have spent additional time and resources to duplicate, at least in part, the efforts of the state’s expert panels.

LAO Recommendations

We recommend the Legislature adopt a package of six reforms designed to expand district choice, lower cost, and enhance program effectiveness. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature reform the existing system by: (1) using fewer sets of evaluation criteria, (2) streamlining the review process, (3) offering districts voluntary extension of already adopted materials, (4) shifting focus back to core materials by eliminating gratis items, (5) ensuring greater predictability by capping mid-cycle price increases, and (6) enhancing information gathering and sharing.

Below, we discuss each of these six recommendations. All would require statutory change. Together, they could yield potentially big savings to both districts and the state, without undermining the publishing industry or stifling input from advocates. These recommendations—along with the problems they are intended to address and their likely effect on choice, cost, and quality—are summarized in Figure 7.

|

Figure 7

Summary of Recommended Reforms |

|

Problem With Existing System |

Recommended Reform |

Likely Effect |

|

|

|

District

Choice |

Cost of Materials |

Program Effectiveness |

|

Based on four sets of evaluation criteria, thereby increasing requirements and

inflating instructional material costs |

Eliminate use of curriculum frameworks

as evaluation criteria |

Increase number and types of adopted

materials |

Reduce for school districts, the

state, and publishers |

Streamline process—resulting in

greater efficiency |

|

Involves many agencies and groups,

many of whom duplicate functions, thereby inflating

costs |

Have expert panels report directly to

SBE |

Increase number of adopted materials |

Reduce for school districts and the

state |

Streamline process—resulting in

greater efficiency |

|

Just when fully implemented, process

begins again, meaning school districts need to

purchase "new" materials shortly after they feel

expert in using "old" materials |

Allow districts to maintain program for up to two consecutive cycles |

Increase choice |

Reduce for school districts and the

state |

No direct or major effect |

|

Reduced competition has resulted in

marketing strategies that shift focus from quality

of core materials to "gratis" items |

Eliminate gratis items, require each

instructional material to be priced and sold

separately |

No direct or major effect |

Reduce for school districts, the

state, and publishers |

Improve quality as each instructional

material would be evaluated on its own merits |

|

Significant initial investment in instructional materials program virtually compels school districts to pay unconstrained mid-cycle price increases |

Limit annual price increases to inflationary index |

None |

Make more predictable for school districts |

None |

Use Fewer Sets of Evaluation Criteria. First, we recommend the state continue to assess instructional materials based on academic content standards, social content standards, and other basic evaluation criteria (such as program organization and instructional support), but eliminate curriculum frameworks (which are designed to guide the teaching of standards) from the evaluation process. Under the new system, K-8 frameworks would continue to be developed and available as instructional guides for school districts, as is currently the case with high school curriculum frameworks. Removing them from the instructional material review process, however, would help retain focus on overarching content standards rather than specific pedagogical preferences. It also likely would reduce the instructional material requirements. This, in turn, likely would allow more publishers, potentially even small- and mid-sized publishers, to submit materials, thereby increasing district choice and reducing cost.

Streamline Review Process. Second, we recommend the state continue to involve expert panels, CDE, SBE, publishers, other advocates, and the general public in the framework development and adoption process but eliminate the role of the Curriculum Commission. This would be consistent with the process used in most adoption states, which either do not have such commissions or do not involve them in adoption decisions. As with the frameworks themselves, the Curriculum Commission would continue to exist and provide state-level guidance in developing effective instructional programs. Removing the commission from the adoption process, however, would streamline the process significantly—eliminating virtually all of the existing redundancies. Under the new process, expert panels would report directly to SBE, and publishers would appeal compliance and adoption decisions directly to SBE. Eliminating the frameworks and commission from the process would cut the length of the process almost in half. It also would constrain the state-level tendencies to override the evaluation decisions of teachers and other experts. In so doing, it likely would increase the number of district options and reduce instructional material costs.

Offer Districts Voluntary Extension of Already Adopted Materials. Third, we recommend the Legislature allow school districts to use already adopted materials for up to two consecutive cycles. Under such a system, the state would continue to adopt new materials every six years, but school districts would have the choice whether to continue with existing materials or purchase new materials. School districts still would be required to replace lost and worn materials and could purchase new instructional tools as they became available, but they would not be required to purchase entirely new sets of materials every six years. This could be particularly helpful in subjects such as mathematics, for which new developments affecting K-12 education are less frequent. Being able to extend materials for up to 12 years would allow school districts to reduce both textbook and professional development costs significantly, with potential state savings. Voluntary extension also would allow teachers to become more familiar with and adept at using adopted materials. Given the longer time horizon and potential for more sustained payoffs, such a change also might entice small- and mid-sized publishers to submit materials in California. This would further increase competition and drive down costs.

Shift Focus Back to Core Program by Eliminating Gratis Items. Fourth, we recommend the Legislature amend statute to eliminate gratis items and require publishers to sell each product separately. Eliminating gratis items likely would reduce the cost of core instructional materials. This is because ancillary products would need to be sold separately at their market value. As a result, school districts could experience a significant decline in instructional material spending, with potential savings at the state level. In addition, eliminating gratis items would create stronger incentives for publishers to compete solely on the quality of their core materials, which, in turn, could improve the quality of those materials.

Cap Mid-Cycle Price Increases. Fifth, we recommend the Legislature link prices to an annual inflationary index (such as the Consumer Price Index or state and local price deflator) during the life of an adoption cycle. This would replace the state’s current practice of allowing unconstrained price increases every two years. Linking price increases to an annual inflationary index would offer districts protection against unreasonable mid-cycle increases as well as greater predictability in prices and greater certainty in budgeting.

Enhance Information Sharing. Lastly, we recommend the Legislature create a better instructional material information system. We recommend the new system include both more and better information on each submitted and adopted set of instructional materials. Specifically, we recommend replacing the state’s current evaluation matrix with one that allows each expert to assess each set of instructional materials on about five evaluation criteria, including alignment to each basic category of the content standards (for example, reading, writing, listening, and speaking), program organization, student assessments, teacher support, and support for EL students. We recommend displaying experts’ assessments on CDE’s public Web site for access by any interested party, including school district administrators, teachers, parents, publishers, and policymakers. In particular, school districts could use the new online information system to help them select programs to pilot, potentially reducing their review costs and enhancing the likelihood those programs would meet their needs.

Conclusion

The problems identified in this report are not trivial and are not likely to disappear over time or go away of their own volition. The shortcomings we identified largely were created by the state and can be addressed only by state action. We think the shortcomings can be largely overcome, however, with a package of six relatively modest reforms. Although the reforms we highlight could be enacted individually, they are likely to be less effective if pursued separately. For example, allowing districts to maintain materials for up to two consecutive cycles would reduce their overall costs, but, without other reforms, districts still would have relatively little upfront choice. Similarly, linking price increases to an annual inflationary index is likely to protect school districts against unreasonable mid-cycle increases, but, without other reforms, school districts’ overall savings would be relatively modest. Taken together, the recommendations would have much greater effect—adding up to more significant savings and more comprehensive reform.

|

Acknowledgments This report was prepared by

Jennifer Kuhn and Jacqueline Guzman. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides

fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature.

|

LAO Publications To request publications call (916) 445-4656.

This report and others, as well as an E-mail

subscription service

, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is

located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page