May 2007

Ensuring an Adequate Health Workforce: Improving State Nursing Programs

In recent years, the number of registered nurses in the state has not kept up with demand. While the mismatch in coming years may not be as large as forecasted, the state needs to continue its efforts to increase the number of nurses to meet projected need. Increasing the supply of nurses relies in large part on the state’s higher education system, which trains the majority of registered nurses in California. In this report, we recommend ways the Legislature can increase enrollment in state nursing programs as well as reduce attrition rates, particularly in the community colleges. Taken together, these measures would increase significantly the supply of registered nurses, and address concerns about the adequacy of the size of the nursing workforce.

Introduction

In recent years, there have been increasing concerns regarding a potential mismatch between the demand for registered nurses and the size of the registered nurse workforce. These concerns have been expressed in a number of states, including California, and in both the public and private sectors. Numerous studies have warned that the need for registered nurses is likely to increase in future years as the population grows and ages. Unless the supply of registered nurses keeps pace with growing patient demand, the delivery of health care services to the public could be adversely affected.

California’s higher education system plays a major role in training and supplying the state’s registered nurses. In the past few years, the Legislature has directed the system to expand this role. In particular, recent state budgets have augmented funding to the California Community Colleges (CCC), California State University (CSU), and University of California (UC) segments to increase the number of nursing enrollment slots. In addition, new laws such as Chapter 837, Statutes of 2006 (SB 1309, Scott), have sought to improve the nursing pipeline by addressing matters such as student attrition and faculty recruitment.

This report is organized as follows. First, it describes the state’s role in training and licensing registered nurses. Second, we provide an estimate concerning the current and—absent corrective actions—future supply of and demand for registered nurses. Third, we discuss oft-cited challenges to increasing the supply of nurses, particularly as regards the state’s higher education system. Finally, we recommend actions for the Legislature’s consideration to increase the number of completions from state nursing programs.

Background on State Nursing Requirements and Programs

Registered nurses provide a variety of health care services. Under the direction of a physician, registered nurses perform such tasks as administering medications, performing diagnostic tests, and monitoring and recording patients’ condition. Registered nurses often supervise other health care personnel such as licensed vocational nurses and certified nurse assistants. In addition to providing and supervising direct patient care, registered nurses also work in areas such as administration, teaching, and research.

Registered Nurse Demographics

Currently, there are approximately 230,000 registered nurses working full or part time in California. According to a 2004 survey, most registered nurses in California (91 percent) are female. About two-thirds of registered nurses are white, 22 percent are Asian, 6 percent are Latino, and 4 percent are African-American. Slightly more than one-half (55 percent) of the state’s registered nurses received their nursing education within California. About one-quarter of the state’s registered nurses were educated in other states, and the remaining nurses (18 percent) were educated in other countries—such as Canada and the Philippines. The average age of the registered nurse workforce is increasing. While in 1990 the average age was 43 years, today it is about 48 years.

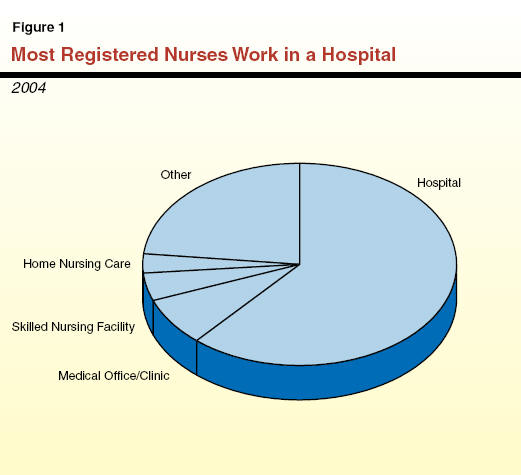

Registered nurses are employed in the public and private sectors and operate in various settings, including hospitals, medical offices and clinics, skilled nursing facilities, and patients’ homes. Figure 1 details where registered nurses are employed. The majority work in hospitals. Most registered nurses are hired directly by a service provider. About 8 percent of nurses are employed by staffing agencies that provide nurses to service providers on a temporary basis.

The primary responsibility of just over one-half (53 percent) of all registered nurses is to provide direct care to patients. About 18 percent of registered nurses serve primarily as supervisors or managers of health care personnel. The remaining registered nurses in the state work in fields such as education, research, and consulting.

Workday patterns among nurses vary. About two-thirds of registered nurses work full time (defined in a survey of nurses as working over 32 hours per week). On average, full-time nurses work 42 hours per week, and part-time nurses work 23 hours per week. In addition, nurses tend to work long shifts. In 2004, over 90 percent of surveyed nurses reported working 9 or more hours per day, with one-third of nurses regularly working 12-hour shifts. One-quarter of nurses work at least some mandatory overtime, with the average amount of their mandatory overtime totaling about six hours per week.

Salaries for registered nurses have increased considerably in recent years. The average annual salary for a full-time nurse increased from about $52,000 in 2000 to $69,000 in 2006, an increase of 32 percent over the six-year period (13 percent after adjusting for inflation).

State Requirements to Become a Registered Nurse

All registered nurses in the state must have a license issued by the California Board of Registered Nursing (BRN). To obtain a license, students must complete a number of steps, including graduating from an approved nursing program and passing the national licensing examination.

In California, there are four types of pre-licensure educational programs available to persons seeking to become a registered nurse. All four types are generally full-time programs, and each combines classroom instruction and “hands-on” training in a lab with clinical placement in a hospital or other health facility. The first two options are for students to enroll in either an associate degree in nursing (ADN) program at a two-year college, or a four-year bachelor’s degree in nursing (BSN) program at a university. In addition, individuals who are already licensed vocational nurses may choose to enroll in an accelerated nursing program at a two-year college. Finally, students that already hold a bachelor’s or higher degree in a non-nursing field are eligible to apply for an entry-level master’s (ELM) program at a university. Generally, students in an ELM program complete educational requirements for a registered-nurse license in about 18 months, then continue for another 18 months to obtain a master’s degree in nursing. Besides providing direct care, nurses with a master’s degree often serve as educators, researchers, and administrators.

Students that complete nursing program requirements are eligible to take the National Council Licensing Examination. Applicants that pass the examination and a criminal background check are licensed by BRN to practice as a registered nurse in California. (Registered nurses from other states and countries that want to work in California must also pass the national licensing examination and background check, as well as show proof of completion of a nursing educational program that meets state requirements.)

Nursing Programs in California

Currently, 110 public and private colleges in California offer a total of 123 pre-licensure nursing programs. As Figure 2 shows, most of these are ADN programs offered at CCC, which graduated almost two-thirds of nursing students in the state in 2005-06. In addition, there are 17 BSN programs offered by CSU and UC, and 12 BSN programs offered at private four-year institutions. There are a total of 15 ELM programs in the state. Appendix A (see page 20) lists all California nursing schools by program type.

|

Figure 2

Prelicensure Nursing Programs in California |

|

|

Number of Programs |

Number of Graduates in 2005-06 |

|

Associate’s Degree in Nursing |

|

|

|

California Community Colleges |

70a |

4,852 |

|

Private colleges |

8b |

384 |

|

County of Los Angeles program |

1 |

110 |

|

Totals |

79 |

5,346 |

|

Bachelor's Degree in Nursing |

|

|

|

CSU system |

15 |

1,246 |

|

UC system |

2c |

— |

|

Private institutions |

12d |

615 |

|

Totals |

29 |

1,861 |

|

Entry-Level Master's Degree |

|

|

|

CSU system |

8 |

29 |

|

UC system |

2 |

74 |

|

Private institutions |

5 |

213 |

|

Totals |

15 |

316 |

|

Grand Totals |

123 |

7,523 |

|

|

|

a Two

programs admit only licensed vocational nurses. |

|

b Four

programs admit only licensed vocational nurses. |

|

c New

programs that began in 2006-07. |

|

d One

program admits only licensed vocational nurses. |

A total of 26 nursing programs have been added in California since 2000-01—an increase of 25 percent. Of this amount, 15 programs are state-run and 11 are administered by private colleges.

Nursing Program Applications Far Exceed Admissions. Statewide, the number of applicants to nursing schools in California far exceeds the number of available slots. According to a 2007 BRN study, for example, California nursing programs received a total of 28,410 eligible applications for just 11,000 first-year slots for the 2005-06 school year. (Eligibility is based on the applicants meeting a minimum set of requirements to apply to a program.) This means that there was capacity to accommodate less than 40 percent of applications. The mismatch between potential students and actual slots applies to all types of nursing programs in the state, including the ADN, BSN, and ELM programs. Figure 3 breaks out nursing program applications and available slots by program type.

Nursing Program Admissions Policies Vary. California nursing schools have developed different strategies in order to decide which applicants to accept into a program. Generally, nursing programs at four-year institutions and two-year private colleges require students to take certain prerequisite courses (such as anatomy and microbiology) as well as a standardized test before applying to the program. Applicants are then ranked by criteria such as the applicant’s grade point average on the prerequisites and test score results. The students with the top overall scores are admitted to the program in accordance with the number of available first-year slots. For example, the 40 highest-ranking applicants would be admitted into a program with space for 40 nursing students.

In contrast, ADN programs at community colleges rely heavily on nonmerit-based or only partially merit-based selection processes. This follows a legal settlement concerning equal access (see box below). All community college nursing programs require at a minimum that applicants obtain at least a “C” average on multiple science prerequisite courses in order to qualify for admission. Some nursing programs require that applicants meet stricter criteria (such as at least a “B” average on prerequisites) in order to apply, though these requirements must be justified through validation studies.

Because there are more applicants that qualify for admission than enrollment slots, community college nursing programs must decide which applicants to admit. The method of selecting students varies by program. Many programs use a lottery system, which randomly selects students from a pool of applicants. Others admit students on a first-come, first-served basis, or give priority to “wait-listed” applicants that were not chosen in prior years. As discussed above, the community colleges do not select from among eligible students based strictly on merit criteria.

CCC Assessment and Selection Policies

Until the early 1990s, many California Community College (CCC) nursing programs chose students by ranking them according to factors such as grades in prerequisite classes and test score results. Students in various other programs also were required to take assessment tests for course placement purposes. In 1988, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) filed a lawsuit against the CCC system. The MALDEF contended that CCC’s assessment, placement, and prerequisite policies were disproportionately excluding Latino students from certain courses and programs (including nursing).

The organization agreed to drop the lawsuit in 1991 after the CCC Chancellor’s Office committed to develop a new set of regulations. Under these regulations, nursing programs, for example, are allowed to continue requiring prospective students to complete (with at least a “C” grade) science prerequisite courses (such as anatomy and microbiology) to be eligible to apply. Community colleges are permitted to require applicants to take and pass nonscience classes (such as English composition), though districts must first conduct a validation study showing that students who fail to satisfy such requirements are “highly unlikely” to succeed in a nursing program. Validation studies also must be conducted in order for districts to require applicants to obtain grades higher than a “C” on prerequisite classes. In addition, community colleges must offer basic skills courses (such as English-as-a-second-language instruction and elementary mathematics) to help applicants achieve minimum eligibility requirements. The regulations require nursing programs to adopt nonevaluative selection methods when there are more eligible applicants than enrollment slots. Approved methods include randomly selecting students and selecting students based on a “first-come, first-served” basis. |

Recent Trends

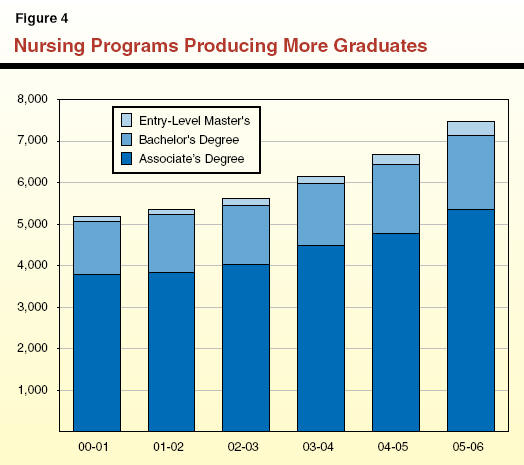

More Graduates. Figure 4 shows that nursing programs have increased the number of graduates significantly in the past few years. A total of about 7,500 students graduated from a nursing school in California during the 2005-06 school year, which exceeds the prior year’s level by 800. This is largely because recent state budgets have included augmentations to fund expansions of nursing programs at all three segments. These augmentations include both one-time and ongoing appropriations, and fund both undergraduate and graduate enrollment. Most recently, the 2006-07 Budget Act provides support for a number of nursing program expansions, as shown in Figure 5.

|

Figure 5

Major

Nursing-Related Appropriations in 2006-07 Budget Package |

|

(In Thousands) |

|

Description |

Appropriation |

|

University of California |

|

|

Increase entry-level master's

students by 65 FTE students |

$860 |

|

Increase postlicensure nursing

students by 20 FTE students |

103 |

|

California

State University |

|

|

Fund startup costs to prepare

for nursing program expansions in 2007-08 |

$2,000 |

|

Increase entry-level master's

students by 280 FTE students |

560 |

|

Increase baccalaureate nursing

students by 35 FTE students |

371 |

|

California

Community Colleges |

|

|

Fund new Nursing Enrollment

Growth and Retention Program |

$12,886 |

|

Fund enrollment and equipment

costs for nursing programs |

4,000 |

|

Fund new Nursing Faculty

Recruitment and Retention Program |

2,500 |

|

California

Student Aid Commission |

|

|

Authorize 100 new SNAPLE

awards |

—a |

|

Authorize 40 new nurses in

State Facilities APLE awards |

—a |

|

|

|

a

State will not incur costs for forgiving loans under

this program until subsequent years. |

|

FTE=full-time equivalent; SNAPLE=State Nursing APLE;

APLE=Assumption Program of Loans for Education. |

Nursing programs have also expanded capacity through partnerships with hospitals and other institutions (such as foundations). These organizations provide funding or other in-kind support, often matched with federal Workforce Investment Act funds, in order to improve the pipeline of nursing graduates. For example, in recent years a number of health care organizations (such as Sutter Health and Kaiser Permanente) have supplied faculty, equipment, facilities, and financial aid to increase enrollment at nursing programs.

In addition to expanding nursing programs, recent legislative actions created new programs to recruit and retain nursing faculty, and to provide new forms of financial aid specifically for nursing students. For example, the 2006-07 Budget Act authorizes 140 new loan forgiveness awards for nursing students. These Assumption Program of Loans for Education (APLE) awards are available to students that teach in a nursing program or work in certain state health care facilities upon graduation.

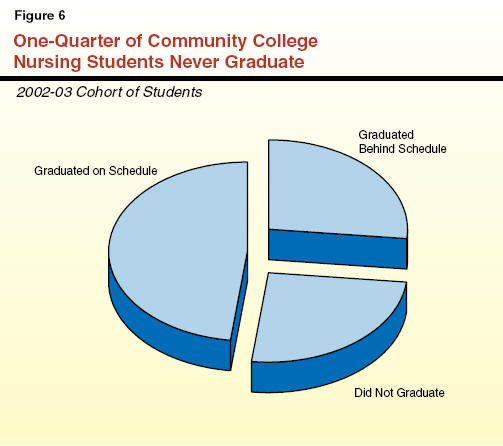

CCC Attrition Is a Concern. A large number of nursing students, particularly at community colleges, never complete their degree. As Figure 6 shows, about one-half of the roughly 6,000 students that enrolled in a community college ADN program in 2002-03 graduated on schedule—that is, in two years. About one-quarter of the students graduated behind schedule, taking three or more years. Another one-quarter (about 1,500 students) never graduated. The attrition rate for the community colleges is much higher than that of UC and CSU nursing students (about 7 percent).

A recently enacted law—Chapter 837, Statutes of 2006 (SB 361, Scott)—seeks to reduce attrition in CCC nursing programs by ensuring that students are sufficiently prepared for success in a nursing program. Specifically, Chapter 837 allows community colleges to administer a diagnostic assessment test to admitted students before they start a nursing program. Students that are unable to obtain a passing score must demonstrate readiness for the program by, for example, passing remedial courses (such as English or math classes) or receiving tutorial services from community college staff.

Assessing the Demand for and Supply of Registered Nurses

As noted above, roughly 230,000 registered nurses currently work part or full time in California. This translates into about 200,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) registered nurses (a measure which converts part-time employment into the equivalent full-time basis). In recent years, health care employers have indicated that the size of the nursing workforce is making it increasingly difficult for them to adequately staff health care facilities. This is particularly true for hospitals, which are statutorily required to maintain minimum nurse-to-patient ratios. Generally, hospitals are using several approaches to provide sufficient patient coverage, including encouraging—and in some cases, requiring—existing staff to work overtime, and employing “traveling” nurses (contract nurses from out-of-state that work on a temporary basis in California).

State’s Demand for Registered Nurses Is Projected to Grow Significantly

The state’s demand for registered nurses is expected to increase in future years. This is primarily because California’s population is projected to increase and grow older, two key drivers of health-care service demands. Between 2007 and 2014, for example, the state’s population is projected to increase by almost 10 percent, or 3.6 million residents. During that same period, the state’s population of seniors (aged 65 and over), is expected to increase by one-quarter, from 4.1 million to about 5.2 million. Taking into account these projected demographic changes, several recent studies have attempted to estimate the demand for registered nurses in future years. The California Employment Development Department, for example, projects that the state will need approximately 240,000 FTE registered nurses by 2014. The U.S. Bureau of Health Professions forecasts similar levels of demand for California. A University of California—San Francisco (UCSF) study conducted for BRN in 2005 forecast a statewide demand of between 241,000 and 257,000 FTE registered nurses by 2014. If these forecasts are accurate, the state will need a net increase of more than 40,000 FTE registered nurses within the next decade in order to meet projected demand.

Like most forecasts, these occupational-demand studies rely on a series of assumptions that may or may not prove to be correct. For example, forecasts of the supply of foreign nurses working in California could change if the federal government modified its immigration policies. These demand studies also assume that there will not be any significant differences in how health care is delivered to patients over the next several years. To the extent that these assumptions do not hold true, demand for nurses will differ from projected levels.

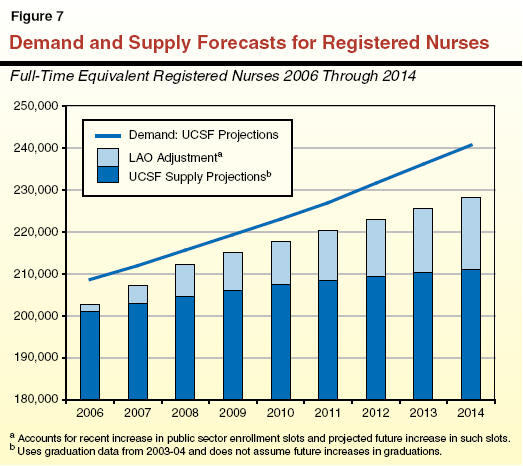

Supply of Nurses Also Expected to Increase, Though Not as Fast as Demand

Projecting changes in the supply of registered nurses is difficult, as well, since the future total depends on a number of factors. “Inflows” of nurses (such as graduates of state nursing programs and new arrivals to California of nurses from other states and countries) increase the supply of nurses in the state’s workforce. “Outflows” of nurses (such as retirements and the migration of California-based nurses to other states) reduce the size of the workforce. Using data from BRN and other surveys to estimate future inflows and outflows, UCSF forecast the supply of registered nurses to grow by 11,000 FTEs (from 200,000 to 211,000 FTEs) between now and 2014, as the number of new nurses in the state is largely offset by factors such as retirements.

We believe the UCSF forecast now understates the supply for two reasons. First, the UCSF model is based on an “inflow” assumption that California nursing schools would graduate about 6,200 students annually throughout the forecast period (the number during the 2003-04 school year, which was the most recent data available at the time of the 2005 report). As noted earlier, however, in the past few years both private and public institutions have significantly increased enrollment capacity. As a result, the number of students graduating from nursing programs exceeded 7,500 in 2005-06. Second, the UCSF model does not include a growth factor for graduations in future years. We think a more reasonable assumption is that capacity will continue to increase throughout the forecast period. In the next three years, we expect to see a significant year-to-year increase in graduations (approximately 10 percent annually) as students occupying enrollment slots that were created as a result of recent funding increases graduate from a nursing program. In future years, even without any further specific policy actions by the Legislature, we would expect future nursing enrollment to grow on the natural with overall enrollment growth at institutions—which is generally around 2 percent annually.

Taking into account recent increases in capacity and building in a growth factor (10 percent growth annually through 2008-09, and 2 percent annually thereafter), the adjusted model forecasts that the supply of registered nurses would total about 228,000 FTEs by 2014. Figure 7 shows demand and supply forecasts for registered nurses through 2014.

Various Ways Supply of Nurses Could Grow to Meet Anticipated Demand

The above analysis suggests that, to accommodate the projected demand for roughly 240,000 FTE registered nurses by 2014, the state will need to increase the number of FTE nurses by at least 12,000 over our office’s supply projection (from 228,000 to 240,000 FTE nurses). Increasing the number of nursing program graduates could help close this gap. (We discuss this option in more detail below). Yet, there are a number of other ways to help close the gap between projected supply and projected demand. For example:

-

The supply of FTE nurses would grow if more nurses worked a slightly longer work week. The UCSF model suggests that if all working nurses under the age of 50 increased the average time worked per week by just one hour (through regular time or overtime), the state’s supply of FTE registered nurses would increase by almost 4,000 FTEs by 2014.

-

Further increases to the nursing supply could be achieved if employers recruited more registered nurses from other states to work in California. An increase in the annual number of out-of-state nurses that migrate to California from approximately 5,200 to 5,500 would further increase the statewide supply by about 2,000 FTEs by 2014.

-

Finally, there are about 7,000 actively licensed registered nurses in the state that are currently employed in a non-nursing field. A 2004 BRN survey of nurses indicates that a major reason they no longer work in nursing stems from dissatisfaction with the profession (such as relations with management). To the extent that employers such as hospitals make nursing a more attractive occupation, they may entice many of these people back into direct patient care.

Increasing Graduations. There are two major approaches to increasing the number of nurses graduating annually from the state’s higher education system: (1) add more slots in ADN, BSN, and ELM programs, and (2) reduce the attrition rate in nursing programs, thus increasing the number of graduates. As noted in the previous section, about one-quarter of ADN students leave their program prior to receiving a degree. If that rate were 7 percent (the approximate attrition rate for UC and CSU nursing students), the state would graduate hundreds of additional nurses each year.

In combination with other strategies mentioned above, we believe accommodating the demand for registered nurses will require only modest increases in nursing program capacity. The following section discusses challenges to increasing the output of new nurses, and the concluding section offers recommendations for addressing those issues.

Challenges to Expanding Capacity and Reducing Attrition

Increasing Enrollment Slots at UC, CSU, and CCC

Funding Issues. Typically, the Legislature provides funding in the annual budget act for enrollment growth at each of the three segments. With minor exceptions, each segment’s enrollment augmentation is based on a single rate of funding for each new FTE student. Although different programs incur different costs per student, the growth funding is based on an average, and thus all programs—both high cost and low cost—can grow in proportion to the growth funding provided. For example, funding for 2 percent system growth would enable all programs—including nursing—to grow by 2 percent. Generally, the segments themselves make decisions about how the new enrollment slots will be distributed among the programs they judge to require expansion.

The segments, therefore, expand nursing enrollment each year using their regular enrollment growth allocations. However, in recent years the segments have contended that this funding approach impedes their ability to respond quickly to the increased demand for nurses. This is because the costs to educate a student in a nursing program are much higher than the nominal per-student funding rate. (This is due mainly to the lower faculty-student ratio that is required for clinical classes, as well as equipment costs.) As a result of these higher costs, segments are not able to increase the proportion of FTE nursing students at a college without directing some funding away from other (lower-cost) student programs. This acts as a fiscal disincentive for segments to increase nursing enrollment slots more rapidly than the funded growth rate for overall programs.

In recent years, the Legislature has responded by providing supplemental funding on top of normal per-student funding. As we discuss in the 2007-08 Analysis of the Budget Bill, however, funding for nursing enrollment has varied considerably among and within the segments, with some enrollment slots supported by supplemental amounts of varying size and others receiving only the normal per-student funding rate. The different funding rates can depend on whether the student is filling an existing slot, a new slot within the segment’s overall enrollment growth allocation, or a new slot created outside the regular growth allocation. Moreover, some funding is considered one-time while other funding is considered ongoing. The result is an increasingly complicated and confusing set of expectations with regard to nursing enrollment.

Faculty Considerations. Another expansion-related factor to consider is faculty recruitment and retention. Nursing programs require faculty (generally nurses with a master’s degree or higher) to educate students in the classroom, laboratories, and clinical settings. Yet, a number of nursing programs have reported difficulty filling faculty positions, particularly as programs expand. According to BRN, the statewide vacancy rate for nursing faculty has increased from 4.1 percent (83 faculty positions) in 2001-02 to 6.6 percent (192 faculty positions) in 2005-06.

In fact, certain state laws serve as barriers to hiring and allocating nursing faculty resources, particularly as regards the community colleges. For instance, the state Education Code places limitations on the percentage of part-time and temporary faculty that are employed by a community college district. One provision requires that at least 75 percent of all credit instruction be provided by full-time faculty. Districts that fall below targets set by the Chancellor’s Office may be subject to financial penalties. This provision can influence campus decisions to expand nursing programs, because about one-third of nursing faculty works part time at the college. Given that a registered nurse can often earn a higher salary in the medical field than at a community college, many colleges are finding it harder to hire full-time nursing faculty than part-time nursing faculty.

Another provision restricts the number of semesters that a “temporary” faculty member can teach in a three-year period. Although the allowable number of semesters for temporary clinical nursing faculty (four) is larger than for other temporary faculty (two), this still limits colleges’ flexibility in hiring nursing instructors.

Facility Constraints. Space is another obstacle to expanding nursing enrollment. Nursing programs require classroom facilities as well as laboratory space to educate students. The segments report that many nursing programs are reaching full capacity. Unless new facilities are constructed, they contend it will be increasingly difficult to accommodate additional nursing students.

Student Attrition

High Attrition Rates in CCC Nursing Programs. Besides increasing capacity, more nurses could be trained by reducing attrition rates. In particular, a reduction in attrition rates at community college nursing programs would increase considerably the state’s supply of nurses.

Nursing students that leave a program prematurely tend to do so relatively late in the program. According to the California Postsecondary Education Commission (CPEC), about one-quarter of dropouts leave their program by the beginning of their second year. Another one-half leave sometime during their second year. The remaining one-quarter of dropouts do not leave a program until sometime after their second year.

Academic Failure Is Main Attrition Factor. Of the various factors that contribute to students dropping out of a program, BRN’s 2005-06 survey of nursing programs cites academic failure as the top reason. (Others include personal reasons such as family obligations and financial need.) Nursing program directors contend that many students are not prepared academically for the rigors of a nursing curriculum. As a result, they do not receive passing grades in their classes and eventually leave the program. Other students may have the necessary skills but need to work full time to support themselves, making it difficult to devote sufficient time to their studies.

Study Addresses CCC Attrition, Admissions Practices. In 2003, CPEC released a report on CCC attrition. A major focus of the study was the extent to which CCC admissions processes allow for the identification of those students that were most prepared for and, therefore, most likely to succeed in a nursing program. The study found that the community colleges’ admissions policies rely heavily on random selection, and identified this as a possible source of the attrition problem. As a result of the lottery process, some of the most prepared applicants are not selected, while many lesser-prepared students are admitted.

The study noted that entering students are often underprepared in core subjects such as mathematics, science, and English. This lack of proficiency serves as an obstacle to graduation. Based on the success of programs that had more selective admission requirements at the time, the study recommended that at least a portion of enrollment slots be reserved for the most qualified applicants (such as those with the highest grades on their prerequisite courses). The CPEC recommended that the remaining students be chosen using a nonmerit method such as random selection.

The CPEC study also found that the nursing programs with the highest success rates tended to offer more comprehensive student-support services, including tutoring, mentoring, and programs for students that speak English as a second language. In fact, programs that offered at least two support services had significantly higher graduation rates than programs that offered one or no service. As a result, CPEC recommended that nursing schools offer English-as-a-second-language instruction, remedial support services in math and science, and tutoring programs—three programs associated with program success.

Recommendations

In this report, we have discussed the state’s role in training registered nurses and the challenges to further expanding their supply to meet projected future demand. Based on the findings of our review, we recommend (1) removing fiscal disincentives for segments to rapidly expand enrollment slots, (2) expanding the state’s nursing faculty loan forgiveness program to attract more educators, (3) temporarily exempting community college nursing faculty from certain hiring restrictions, (4) encouraging nursing programs to use existing facilities more efficiently, (5) providing “completion bonuses” to community colleges that improve student outcomes, and (6) implementing a merit-based admissions policy for community college nursing programs to address attrition concerns. We believe that these recommendations would help to close the gap between the supply of and demand for registered nurses (forecasted to grow to roughly 12,000 FTE registered nurses by 2014, as discussed earlier).

Address Fiscal Disincentives to Expanding Enrollment

In order to address the shortfall in registered nurses, we recommend that at least for the next several years the Legislature provide supplemental funding for each new nursing slot.

As discussed earlier, the annual budget includes funding for overall enrollment growth at each segment. In general, the state funds instruction using a single per-student rate at each segment. This funding rate is intended to cover the costs of serving an “average” student, recognizing that students in some disciplines (such as the social sciences) may impose lower costs, while students in other disciplines (such as nursing) may impose higher costs. It is up to the segments to decide what kind of enrollment they will expand.

In recent years, however, the demand for nursing enrollment slots has exceeded the growth rate for overall programs. Because the cost of educating nursing students is unusually high, there is a disincentive for segments to rapidly expand enrollment when the state provides only the regular per-student funding rate for these slots. As noted earlier, while the Legislature has at times provided supplemental funding beyond the regular growth funding, the funding approach has been inconsistent.

We see justification for providing the segments with supplemental funding for nursing students above what segments receive for other students. The extra funding recognizes three special factors concerning nursing programs:

As we discuss in our 2007-08 Analysis of the Budget Bill, these special factors make nursing a unique case. For this reason, we have recommended against supplemental funding for other courses (such as certain science classes with above-average costs. In addition, we recommend that the supplemental funding for nurses be provided only for a limited time period and ended once enrollment growth for nurses is more in line with overall enrollment growth.

Expand Eligibility for Nursing Faculty Loan Forgiveness Program

We recommend the Legislature amend statute to expand the pool of applicants eligible for the State Nursing Assumption Program of Loans for Education (SNAPLE) in order to attract and retain more nursing faculty.

As noted earlier, many nursing programs have indicated that they are having difficulty filling faculty positions, which creates a barrier to expanding nursing programs. To address this issue, the 2006-07 budget package authorizes nursing student participation in new APLE programs. Specifically, the budget directs the California Student Aid Commission to issue 40 new loan forgiveness awards for the Nurses in State Facilities APLE, and 100 new awards for SNAPLE. The latter program forgives up to $25,000 in student loans for graduates of nursing programs who teach for three years in a California college or university. The purpose of SNAPLE is to recruit faculty to educate the increasing number of students in state-supported nursing programs.

Currently, SNAPLE is only available to persons who have not yet completed their degree in nursing. Consequently, the benefits of SNAPLE will not be realized until award recipients complete their nursing program and obtain a faculty position—which could take several years. To realize a more immediate benefit from SNAPLE and increase the pool of potential applicants, we recommend the Legislature amend statute to offer SNAPLE awards to nurses interested in a teaching career who already have a nursing degree. We also recommend the Legislature increase the number of SNAPLE awards to accommodate the larger pool of nurses that would be eligible for this program. If, for example, the Legislature increased the number of awards by 50, it would cost about $1.2 million. (Awards must be authorized annually in the budget act.)

Exempt Nursing Faculty From Restrictive Hiring Policies

We recommend the Legislature amend statute to temporarily exempt community college nursing faculty from certain restrictive hiring policies.

As we discuss earlier in this report as well as in our 2007-08 Analysis of the Budget Bill, there are various laws and regulations in place that limit how community colleges can use faculty. For example, current policies require a certain ratio of full-time faculty to part-time faculty employed by a district and limit the number of terms temporary faculty can teach within a three-year period. As we discussed in the 2001-02 Analysis of the Budget Bill, we find no evidence that these policies improve student outcomes. To maximize community colleges’ flexibility to meet enrollment demands, we thus recommend the Legislature exempt nursing faculty from these restrictions for a limited period (for example, through 2010). We also note that hiring and retaining faculty is greatly affected by the salaries and benefits that campuses offer. Typically, such decisions are subject to collective bargaining at the district level.

Encourage Fuller Use of Existing Facilities

We recommend the Legislature link funding for new nursing facilities to programs’ use of existing facilities in order to encourage more efficient use of resources and more options for students.

As noted earlier, the segments have indicated that nursing programs are outgrowing their classroom and laboratory facilities. Segment officials cite increasingly limited classroom and laboratory space as a barrier to expanding nursing enrollment. Yet, our review indicates that most nursing programs are not using their existing space to full capacity. Currently, most nursing programs are full time, and courses generally are offered only during daytime hours and during the traditional work week. The availability of nontraditional schedules is limited. For example, according to BRN, only 23 of the 70 CCC nursing programs offer evening courses. An even smaller number of programs offer courses on weekends or during the summer term.

We believe that there would be several benefits to expanding the number of nursing programs that offer these types of nontraditional course schedules. First, a more intensive, year-round use of existing instructional space would help to avoid major costs in building new facilities. Second, programs may be able to grow more quickly to the extent that they would not have to wait for new buildings to be constructed in order to accommodate additional students. Third, such a change would provide more choices to students, which could reduce attrition and even accelerate the graduation timeline for certain students. An increase in part-time programs, for example, could give students that work more time to devote to their studies. A year-round program could allow other students to graduate sooner than they would otherwise.

To accomplish these goals, we recommend the Legislature link any new funding for nursing program facilities to programs’ more efficient use of existing facilities. For example, the Legislature could choose to withhold funding for new facilities unless nursing programs already use existing facilities a certain percentage of the time year-round (such as 80 percent). This would ensure that the state did not provide funding for increased instructional space until the segments fully used their existing space.

Provide Nursing Completion Bonuses to Community Colleges

We recommend the Legislature provide “completion bonuses” to community colleges that increase nursing student completions. We recommend the Legislature give the community colleges significant flexibility in how they use these funds to enhance nursing student outcomes.

As discussed earlier, the state’s higher education segments receive funding based largely on the number of students they serve. For example, the amount of funding a community college district receives from the state depends primarily on the number of students enrolled at a point early in the semester. Generally, funds are provided regardless of student outcomes (such as the number of graduations from a program or even the number of students completing a class).

Reward Successful Training of Nursing Students. Given the state’s strong interest in increasing the supply of nurses, we recommend the Legislature strengthen incentives for nursing programs to increase the number of nurses by reducing attrition. This could be accomplished through the enactment of a completion bonus. For example, nursing programs could be eligible to receive extra funding (in addition to per-student enrollment funds) for every student completion above currently projected levels. Alternatively, nursing programs could receive a completion bonus by reducing attrition rates. “Completion” would be defined as graduating with a nursing degree as well as passing the national licensure examination. The inclusion of the latter requirement would ensure that programs do not lower their academic standards to obtain bonus funding. Recipients of these bonuses would have flexibility to spend the funds in whatever way they felt would increase nursing completions. This might include additional support services, which research has shown can be an effective tool for improving student success.

Target CCC, Use New Discretionary Proposition 98 Funds. We recommend including only the community colleges in this program for two reasons. First, community colleges offer the majority of nursing enrollment slots in the state. Second, we project significant base increases over the next several years in the amount of new discretionary Proposition 98 funds—the primary funding source for the community colleges. (Discretionary funds represent the growth in year-to-year Proposition 98 funds that is left after providing for baseline costs such as changes in attendance and cost of living.) As we discuss in our 2007-08 Analysis of the Budget Bill, we project the community colleges could receive roughly $800 million in additional ongoing Proposition 98 discretionary resources by 2011-12. The fiscal impact of a completion bonus for the community colleges would depend on the size of the bonus and growth in the number of completions from nursing programs, but would likely be only a small portion of projected new Proposition 98 funds. For example, a per-student bonus of $5,000 paid on an increase of 500 additional registered nurses per year (about 10 percent more than current levels) would cost $2.5 million annually. Under an alternative approach, a reduction in attrition from 25 percent to 15 percent from a cohort of 6,000 students would yield 600 additional graduations. A bonus payment of $5,000 per student would cost $3 million. Regardless of the Legislature’s preferred approach, we recommend that additional funding be provided for a limited time period (such as five years). This would give the Legislature an opportunity to assess the impact of the program and reassess the continued need for such an incentive program based on the labor market for registered nurses at that time.

Change Nursing Program Admission Policies at CCC

We recommend the Legislature enact legislation to better align the admissions process at community college nursing programs with qualifications for student success.

As discussed earlier, community college policies in such areas as student assessment and placement stem largely from a nearly 20-year old lawsuit settlement involving Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund. The regulations that resulted from the legal dispute require, among other things, that districts use nonevaluative admissions strategies (such as random selection) when selecting students for oversubscribed programs. As a result, nursing programs cannot choose the most qualified and best prepared students from among the pool of applications they receive.

Use a Comprehensive Approach to Identify Best Applicants. Given the state’s interest in reducing attrition, we recommend that the Legislature enact legislation to improve the admissions process in a way that promotes fairness as well as student success. This could include implementing merit-based admissions policies that take into account applicants’ academic performance as well as other skills and special circumstances (such as the ability to speak a second language, community service, and life experiences). We believe that such a comprehensive and evaluative approach would serve state interests by more effectively identifying applicants that are most likely to succeed in a nursing program. We believe that this approach, in combination with other measures such as a completion bonus and the new diagnostic assessment test (discussed earlier), would help to reduce attrition and increase the number of nurses.

Conclusion

While this analysis finds that the mismatch between the supply of and demand for registered nurses is not as large as has been reported elsewhere, the state needs to continue to increase its supply of nurses in order to meet projected growth in demand. Our report has focused on ways the Legislature can increase the supply by creating additional enrollment slots in nursing programs. Recommendations to this end include creating incentives for nursing programs to expand capacity and use existing facilities more efficiently, as well as modifying policies to attract more nursing faculty. In addition, we recommend actions the Legislature could consider to reduce student attrition rates, particularly at the community colleges. These recommendations include offering bonus funding to nursing programs that increase completion rates, and amending statute to allow for merit-based admissions policies. Taken together, we believe that these measures would result in a significant increase to the state’s supply of registered nurses, and address concerns about the adequacy of the size of the nursing workforce.

Appendix A

Prelicensure Nursing Programs in California |

| Associate's Degree in Nursing |

|

|

California Community Colleges |

|

|

Allan Hancock College* |

Merritt College |

|

American River College |

Modesto Junior College |

|

Antelope Valley College |

Monterey Peninsula College |

|

Bakersfield College |

Moorpark College |

|

Butte College |

Mt. San Antonio College |

|

Cabrillo College |

Mt. San Jacinto College |

|

Cerritos College |

Napa Valley College |

|

Chabot College |

Ohlone College |

|

Chaffey College |

Palomar College |

|

City College of San Francisco |

Pasadena City College |

|

College of Marin |

Rio Hondo College |

|

College of San Mateo |

Riverside Community College |

|

College of the Canyons |

Sacramento City College |

|

College of the Desert |

Saddleback College |

|

College of the Redwoods |

San Bernardino Valley College |

|

College of the Sequoias |

San Diego City College |

|

Contra Costa College |

San Joaquin Delta College |

|

Copper Mountain College |

Santa Ana College |

|

Cuesta College |

Santa Barbara City College |

|

Cypress College |

Santa Monica College |

|

De Anza College |

Santa Rosa Junior College |

|

East Los Angeles College |

Shasta College |

|

El Camino College |

Sierra College |

|

El Camino College—Compton Education Center |

Solano Community College |

|

Evergreen Valley College |

Southwestern College |

|

Fresno City College |

Ventura College |

|

Gavilan College* |

Victor Valley College |

|

Glendale Community College |

Yuba College |

|

Golden West College |

|

|

Grossmont College |

Private Programs |

|

Hartnell College |

Maric College |

|

Imperial Valley College |

Mount St. Mary's College |

|

Long Beach City College |

National University |

|

Los Angeles City College |

Pacific Union College |

|

Los Angeles Harbor College |

San Joaquin Valley College* |

|

Los Angeles Pierce College |

Unitek College* |

|

Los Angeles Southwest College |

West Coast University* |

|

Los Angeles Trade-Tech College |

Western Career College* |

|

Los Angeles Valley College |

|

|

Los Medanos College |

Other Programs |

|

Mendocino College |

Los Angeles County College of Nursing and Allied Health |

|

Merced College |

|

|

|

|

|

Bachelor’s Degree in Nursing |

|

|

Public Programs |

Private Programs |

|

California State University, Bakersfield |

American University of Health Sciences |

|

California State University, Chico |

Azusa Pacific University |

|

California State University, East Bay |

Biola University |

|

California State University, Fresno |

California Baptist University |

|

California State University, Long Beach |

Dominican University of California |

|

California State University, Los Angeles |

Loma Linda University |

|

California State University, Sacramento |

Mount St. Mary's College |

|

California State University, San Bernardino |

National University |

|

California State University, San Marcos |

Point Loma Nazarene University |

|

California State University, Stanislaus |

Samuel Merritt College |

|

Humboldt State University |

University of Phoenix at Modesto* |

|

San Diego State University |

University of San Francisco |

|

San Francisco State University |

|

|

San Jose State University |

|

|

Sonoma State University |

|

|

University of California, Irvine |

|

|

University of California, Los Angeles |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Entry-Level Master's Degree in Nursing |

|

|

Public Programs |

Private Programs |

|

California State University, Bakersfield |

Azusa Pacific University |

|

California State University, Dominguez Hills |

Samuel Merritt College |

|

California State University, Fullerton |

University of San Diego |

|

California State University, Long Beach |

University of San Francisco |

|

California State University, Los Angeles |

Western University of Health Sciences |

|

California State University, Sacramento |

|

|

San Francisco State University |

|

|

Sonoma State University |

|

|

University of California, Los Angeles |

|

|

University of California, San Francisco |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* Admits only licensed vocational nurses. |

|

|

Acknowledgments This report was prepared by

Paul Steenhausen and reviewed by

Steve Boilard. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides

fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature.

|

LAO Publications To request publications call (916) 445-4656.

This report and others, as well as an E-mail

subscription service

, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is

located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page