February 2007

California Tribal Casinos: Questions and Answers

In 1987, a U.S. Supreme Court decision involving two California tribes set in motion a series of federal and state actions that dramatically expanded tribal casinos here and in other states. Now, California’s casino industry outranks all but Nevada’s in size. In this report, we answer key questions about tribal casinos in California and their payments to state and local governments.

Introduction

On February 25, 1987, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that neither the State of California nor Riverside County could regulate the bingo and card game operations of the Cabazon Band of Mission Indians and the Morongo Band of Cahuilla Mission Indians. This court ruling, known as the Cabazon decision, set in motion a series of federal and state actions-including two ballot propositions-that dramatically expanded tribal casino operations in California and other states. In 2006, industry estimates suggest that tribal casinos in California took in around $7 billion of annual revenues-about as much as all other legalized gambling sectors in the state combined. Only Nevada now has a larger casino industry.

In this report, we answer key questions related to (1) the history of tribal casino expansion in California and (2) payments from the casinos to state and local governments. We also discuss proposed amendments to several tribal-state compacts that-collectively-would expand the industry significantly in Southern California.

State-Tribal Relations

What Is Tribal Sovereignty?

Indian tribes possess a special status under U.S. law. In 1787, the new U.S. Constitution reserved for the federal government the power to “regulate commerce” with foreign nations, among states, and with Indian tribes. In 1831 and 1832, two U.S. Supreme Court decisions determined that tribes in the U.S. were “independent political communities” with “original natural rights” that preceded European colonization. Certain jurisdictional rights were declared to be ones with which no state could interfere. In the last century, judicial rulings began to recognize tribes’ sovereign immunity from lawsuits as one aspect of this sovereignty. As a result of these laws, a state’s regulation of tribal activities-including casinos-generally is limited to what is authorized under (1) federal law and (2) federally approved agreements between tribes and a state.

What Is the Federal Authority for Tribal Gambling Operations?

The Cabazon decision relied heavily on the principles underlying tribal sovereignty. In its ruling, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected California’s attempts to regulate tribal gambling enterprises in the absence of congressional authorization. In a response to the Cabazon decision, the Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) in 1988. The act provides a statutory structure for tribal gambling operations and declares that Congress seeks to advance three principal goals in authorizing tribal casinos:

- Tribal economic development.

- Tribal self-sufficiency.

- Strong tribal governments.

What Are IGRA’s Key Provisions?

Under IGRA, gambling operations are divided into three categories with varying levels of tribal, state, or federal regulation, as shown in the nearby box. Balancing state and tribal interests, IGRA generally requires that states and tribes enter into compacts to authorize the types of gambling commonly associated with tribal casinos today-such as slot machines-when state law permits similar gambling operations in any other context. The act permits casino operations on Indian lands, which it defines as (1) reservation lands, (2) lands held in trust by the U.S. for benefit of an Indian tribe or individual, or (3) certain specified lands over which an Indian tribe exercises governmental power. The act requires states to negotiate with tribes that request the opportunity to enter into a compact. The IGRA establishes the National Indian Gaming Commission within the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) as a body to limit organized crime and corruption, ensure that tribes benefit from gambling revenues, and enforce the honesty and fairness of certain tribal gambling operations.

Types of Gambling Under IGRA

The Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA) divides tribal gambling operations into three categories, or “classes.”

Class I Games. Class I games are (1) social games for prizes of minimal value or (2) traditional Indian games related to tribal ceremonies or celebrations.

- Who Regulates?

These games are subject only to regulation by the tribes themselves.

Class II. Class II includes several games, such as bingo (either with or without electronic game devices), lotto, and “non-banked” card games like poker. Class II games involve players competing against each other and not the “house” (although this is sometimes a difficult distinction to make given the similarity of modern Class II and Class III electronic devices).

-

Who Regulates?

The IGRA provides for regulation of Class II games by both tribes and the National Indian Gaming Commission (NIGC). In states allowing Class II games, like California, there are no limits on the number of Class II games that a tribe may operate.

Class III. Class III games (sometimes called Nevada-style games) include all other types of gambling. These include slot machines, electronic games of chance, and many banked card games like blackjack. (According to the California Department of Justice, certain craps, roulette, and dice games are prohibited under the State Constitution and laws.)

-

Who Regulates? Tribes and states regulate Class III games pursuant to tribal ordinances and tribal-state compacts approved by the U.S. Department of the Interior. In California, the principal state regulatory agencies are the California Gambling Control Commission and the Division of Gambling Control in the Department of Justice. The NIGC has asserted its authority to regulate and audit tribes’ Class III operations, but in October 2006, a federal appeals court affirmed a lower court decision that no such authority exists under IGRA.

|

What Does the State Constitution Say About Tribal Casinos and Other

Types of Gambling?

California outlawed many forms of gambling soon after statehood. (Cardrooms, or poker clubs, however, have been common throughout the state’s history.) Voters have authorized specific forms of gambling:

- 1933-wagering on horse races.

- 1976-bingo games for charitable

purposes.

- 1984-the California Lottery

(Proposition 37).

Proposition 37 also amended the State Constitution to prohibit “casinos of the type currently operating in Nevada and New Jersey.” Following a court’s determination that a 1998 statutory initiative authorizing tribal casinos (Proposition 5) was unconstitutional, the Legislature placed Proposition 1A on the ballot in March 2000. Proposition 1A amended the Constitution to allow the Governor to negotiate compacts-subject to ratification by the Legislature-with federally recognized Indian tribes to operate certain types of gambling on Indian lands. Games allowed by the amendment include slot machines, lottery games, and banked and percentage card games.

How Many Tribal-State Compacts Have Been Ratified by the Legislature?

The Legislature has ratified 66 tribal-state compacts. In September 1999, anticipating the passage of Proposition 1A, the Governor negotiated and the Legislature ratified compacts with 57 of the state’s 108 federally recognized tribes. (California also has dozens of tribes which are not federally recognized.) These are known as the “1999 compacts.” (Eventually, 61 tribes agreed to the terms of the 1999 compacts.) Compacts with five additional tribes were ratified in 2003 and 2004. Several amendments to these compacts also have been ratified by the Legislature. Most notably, the 2004 amendments to compacts with five tribes substantially altered the original financial framework of the 1999 compacts. These five amended compacts sometimes are called the “2004 compacts.” Currently, nine compacts or compact amendments proposed since 2004 have not received legislative ratification.

What Are the Differences Between the 1999 Compacts and the 2004 Compacts?

Key differences between the 1999 compacts and the 2004 compacts are summarized in Figure 1 (see next page). The 2004 compacts allowed five tribes-two in Northern California (the Rumsey Band of Wintun Indians and the United Auburn Indian Community) and three in Southern California (the Pala Band of Mission Indians, the Pauma Band of Luiseño Indians, and the Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians)-to operate an unlimited number of Class III slot machines in exchange for payments to the state General Fund for machines added after ratification of the compacts. By contrast, tribes could operate no more than 2,000 machines under the 1999 compacts. Unlike the 1999 compacts, the 2004 compacts require payments to the General Fund, as well as payments expected to be used to support a bond that will repay loans made by a state transportation account to the General Fund in 2001-02 and 2002-03. The 2004 compacts also require that tribes negotiate with local governments concerning enforceable memoranda of understanding to address environmental, public safety, infrastructure, and other demands related to casinos.

|

Figure 1

Differences Between 1999 Compacts and 2004 Compacts |

|

1999 Compacts |

2004 Compacts |

|

How many Class III slot machines are

authorized? |

|

·

Up to 2,000. |

·

Unlimited number of machines. |

|

·

Total number of machines statewide

limited to 61,957. |

|

|

Which state funds receive tribal

compact moneys? |

|

·

Revenue Sharing Trust Fund (RSTF):

Payments on a per machine basis. |

·

RSTF: Payments of $2 million annually

per tribe to maintain licenses for machines

operating prior to 2004 compacts. |

|

·

Special Distribution Fund (SDF):

Payments based on percentage of revenue from

machines operated as of September 1999. |

·

SDF: No payments. |

|

|

·

General Fund: Payments of

$8,000-$25,000 per machine added after the 2004

compacts. |

|

|

·

Designated account for transportation

bond: Payments from all of the tribes equal to about

$100 million a year for 18 years. |

|

What support is provided for local

governments affected by casinos? |

|

·

SDF provides grants to these local

governments. |

·

Tribes must negotiate with local

governments on agreements (including potential

payments) to address infrastructure, safety, and

other issues. |

|

What ability do state regulators have to inspect

casino facilities and machines? |

|

·

General compact language concerning

inspections of public and nonpublic

areas and access to records and equipment. |

·

More specific compact language

concerning testing of machines. Regulators may

inspect a certain number of machines up to four

times per year. |

|

When do the compacts expire? |

|

·

December 31, 2020. |

·

December 31, 2030. |

Tribal Casinos in California

How Many Casinos Currently Operate in California?

As of March 2006, 53 tribes operated 54 casinos with Class III machines in California. (The Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians operates two facilities-in Rancho Mirage and Palm Springs-as allowed under the 1999 compacts.) One additional casino (the Lytton Rancheria of California’s casino in Contra Costa County) operated only Class II devices, which does not require a compact with the state. There are some tribes with ratified compacts that do not have a casino, and other tribes have had casinos in development since March 2006.

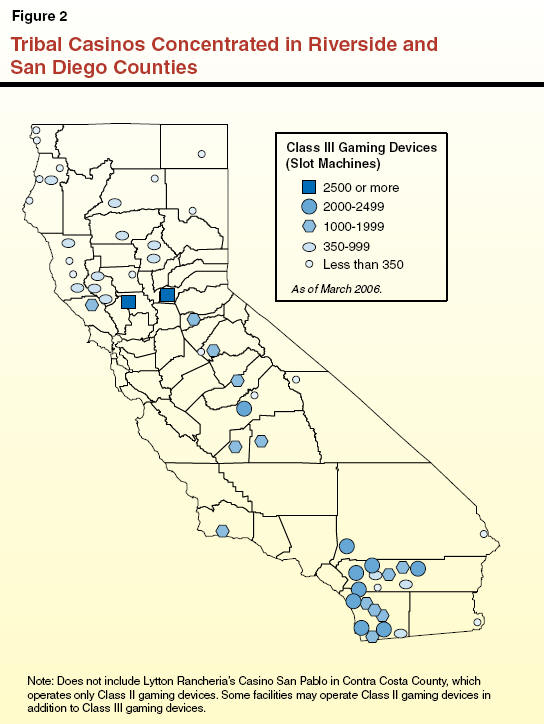

Where Are Casinos Concentrated, and What Are Some of the Largest?

As illustrated in Figure 2, tribal casinos are heavily concentrated in Riverside and San Diego Counties, where 17 of the state’s 54 casinos (and 45 percent of licensed slot machines) are located. Southern California casinos also operate in Imperial, San Bernardino, and Santa Barbara Counties. Nevertheless, the two largest facilities in the state (as measured by the number of Class III devices) are both operated in Northern California pursuant to the 2004 compacts: the United Auburn Indian Community’s Thunder Valley Casino in Placer County and the Rumsey Band of Wintun Indians’ Cache Creek Casino Resort in Yolo County. Industry estimates indicate that Thunder Valley Casino is one of the highest revenue-generating casinos in the country and the highest-ranked facility by this measure in California.

How Many Slot Machines Are

Operating at Tribal Casinos?

The number of slot machines and similar devices at California’s casinos has grown rapidly since passage of Proposition 1A. Prior to passage of the measure, tribes operated an estimated 20,000 slot machines at about 40 casinos, despite the unclear legal environment of the time. As of March 2006, tribes operated over 58,000 Class III devices. Continued expansion is likely, even if the Legislature does not ratify several compacts agreed to by the Governor and tribes in 2006. (These compacts would allow Southern California tribes to operate up to 22,500 additional Class III devices.) In addition to Class III devices, Class II devices-which are not governed by the tribal-state compacts-are at some casinos.

Tribal Payments to State and

Local Governments

How Much Do Tribes Pay to California Governments?

State Government Funds: Compact Revenues. Tribes make payments to several state government accounts under the terms of the tribal-state compacts. Figure 3 shows that state revenues related to the tribal-state compacts (including state interest earnings, if applicable) totaled about $301 million in 2005-06. In that fiscal year, most payments ($173 million) were made to two special funds, the primary uses of which are to disburse grants to non-compact tribes and local governments affected by tribal casinos. (Under the 1999 compacts, non-compact tribes are those federally recognized tribes operating 350 or fewer Class III gaming devices.) Only $27 million was paid directly to the General Fund. In addition, $101 million was deposited to a designated account expected to be used to repay state transportation funds for loans made to the General Fund in prior years. These moneys help relieve the General Fund of a potential cost to repay the transportation funds. Combined, these two revenue sources equaled just over 0.1 percent of General Fund revenues in 2005-06. Unless the Legislature ratifies additional compacts or amendments early in 2007, state revenues in 2006-07 will grow slightly above the 2005-06 levels.

|

Figure 3

Payment by Tribes to State Accounts

Pursuant to Tribal-State Compacts |

|

(In Millions) |

|

Fund |

2005-06

Revenues |

Fund Purpose |

|

General Fund |

$27 |

·

Any state activity. |

|

Indian Gaming Revenue

Sharing Trust Fund (RSTF) |

33 |

·

Pay $1.1 million per year to each

“non-compact” tribe. |

|

Indian Gaming Special

Distribution Fund |

140 |

·

Fund RSTF shortfalls.

·

Gambling addiction programs.

·

Regulatory costs.

·

Grants to local governments affected

by tribal casinos.

·

Other purposes allowed by law. |

|

Designated Account for

Transportation Bond |

101 |

·

Repay state transportation accounts

for loans made to benefit the General Fund in prior

years.

·

Loan repayments may occur either

through (1) the sale of bonds secured by these

annual tribal payments or (2) direct repayment of

transportation accounts from this fund. |

State Government Funds: Taxes. In addition to funds paid pursuant to the compacts, tribes and their members pay certain state taxes. The laws surrounding the taxability of tribes, tribal members, and related enterprises are complex. Tribes and their members are not subject to several types of taxation due to the lack of authority granted to states for this purpose under federal law. Tribal members living on reservations, for example, are not subject to state income tax, and tribal casinos do not pay the corporate income tax. Regarding the sales and use tax, tribes are generally expected to collect taxes on purchases made by nontribal members for consumption or use off of reservations.

Local Government Funds: Compact-Related Revenues. Local governments receive compact-related revenue through (1) funds appropriated from the Indian Gaming Special Distribution Fund (SDF) to mitigate casinos’ effects on local communities and (2) agreements with individual tribes-like those established under the 2004 compacts-to mitigate these effects. Recently, the Legislature has appropriated between $30 million and $50 million per year for mitigation from the SDF for distribution among local governments pursuant to Chapter 858, Statutes of 2003 (SB 621, Battin). Chapter 858, which sunsets on January 1, 2009, provides that priority for distribution of SDF grant moneys be given to localities with one of the tribes that contributes to the SDF (currently, 25 tribes statewide). A few local governments receive significant funds directly from tribes under mitigation agreements reached with tribes for such things as traffic and law enforcement costs. The Rumsey Band of Wintun Indians, for example, pays Yolo County several million dollars per year to address off-reservation impacts of the tribe’s casino.

Local Government Funds: Taxes. In addition to the funds described above, local governments also receive some revenue from the taxation of certain tribal activities and transactions. As in the case of the state, local government has only a limited ability to tax such enterprises. Property taxes and hotel occupancy taxes, for example, do not apply to reservations.

What Is the Revenue Sharing Trust Fund (RSTF)?

Purpose of the RSTF. In addition to ratifying the 1999 compacts, Chapter 874, Statutes of 1999 (AB 1385, Battin), established the RSTF. Under the various tribal-state compacts, tribes make payments to the RSTF in exchange for licenses to operate up to 2,000 slot machines. Chapter 874 provides that the RSTF (upon appropriation by the Legislature) fund distributions to non-compact tribes pursuant to the provisions of the 1999 compacts and subsequent compacts. The 1999 compacts were among the first in the country to share casino revenues with tribes that do not have compacts. Each non-compact tribe receives (1) $1.1 million per year or (2) an equal share of moneys available to the RSTF if funds are not sufficient to make the full $1.1 million payment.

Payments Into the RSTF. Figure 4 shows the payments that 1999 compact tribes make into the RSTF. These payments are based on the number of slot machines that the tribes operate. Subsequent compacts and amendments have specified other levels of payments. The 2004 compacts, for example, specify that each tribe must pay a flat $2 million to the RSTF annually to maintain existing slot machine licenses.

|

Figure 4

Payments Into Revenue Sharing Trust Fund Under 1999

Compacts |

|

Number of Slot Machines |

Annual Payment

Per Machine |

|

1-350 |

— |

|

351-750 |

$900 |

|

751-1,250 |

1,950 |

|

1,251-2,000 |

4,350 |

Addressing RSTF Payment Shortfalls. Through 2002, RSTF funds were insufficient to fund the full annual payment to each non-compact tribe. (The tribes received on average less than one-half of the $1.1 million payment annually.) Chapter 210, Statutes of 2003 (AB 673, J. Horton), provides that (1) SDF funds are available for appropriation to cover shortfalls in the RSTF and (2) covering the shortfalls is the “priority use” for SDF funds. The Legislature has transferred SDF moneys to fund the RSTF shortfall each year since 2002-03. In recent years, these transfers have been around $50 million.

What Is the Special Distribution Fund?

Purpose of the SDF. Chapter 874 also establishes the SDF. Current state law provides that the SDF’s priority use is to cover shortfalls of the RSTF. The law ranks other allowable uses of the SDF in descending order after this priority use, as follows:

- Appropriations to the Department of Alcohol and Drug Programs (DADP) for its Office of Problem Gambling.

- Funding for state regulation by the California Gambling Control Commission (CGCC) and the Division of Gambling Control in the Department of Justice.

- Grants to local governments affected by tribal casinos.

In addition, the law permits SDF disbursements to implement the terms of labor relations provisions of the 1999 compacts and for “any other purpose specified by law.” (Several years ago, a court ruled that this provision allowed SDF funding only for gambling-related activities.)

Payments Into the SDF. Figure 5 shows the payments that 1999 compact tribes make into the SDF. These payments are a percentage of the average slot machine net win (a measure of slot machine revenues) on machines operated by the tribe on September 1, 1999. Most recent compacts or amendments have not required tribal payments into the SDF.

|

Figure 5

Payments Into Special Distribution Fund Under 1999

Compacts |

|

Slot Machines Operated

By Tribe (9/1/99) |

Net Win Per Machine |

|

1-200 |

— |

|

201-500 |

7% |

|

501-1000 |

10 |

|

1,001 or More |

13 |

SDF Fund Condition. Over the last several years, the SDF has collected more revenues each year than the Legislature has spent out of the fund. As a result, the SDF’s fund balance is projected to grow to $132 million by the end of 2006-07. (We discuss the potential effects on the SDF of compacts pending before the Legislature later in this report.)

What Are the

Tribal Transportation Bonds?

Background. The 2004 compacts provide for tribes to make fixed annual payments of about $100 million to the state over 18 years-an annual amount that was reportedly equal to at least 10 percent of the tribes’ net win from slot machines at the time of the amendments. Chapter 91, Statutes of 2004 (AB 687, Nuñez), which ratifies the compacts, authorizes the California Infrastructure and Economic Development Bank (I-Bank) to sell the $100 million annual revenue stream from the five tribes to a special purpose trust. The trust may issue bonds and provide the state with a one-time payment from the bond proceeds in exchange for the state’s sale of the revenue stream. Chapter 91 authorizes the I-Bank to administer a sale of bonds for an amount originally estimated to be $1.2 billion and directs that the bond proceeds be deposited into various transportation accounts to repay loans made from the Traffic Congestion Relief Fund (TCRF) to the General Fund in 2001-02 and 2002-03.

Bond Sale Has Been Delayed and Amount of Bond Proceeds Uncertain. According to the State Treasurer’s Office, two lawsuits filed by tribes, one lawsuit filed by an owner of a card room, and one lawsuit filed by interests related to several horse racing tracks have delayed sale of the transportation bond by the I-Bank. It is not known when or if the bonds will be sold. Since ratification of the 2004 compacts, various sources also have indicated that the proceeds of the bonds were not likely to equal the $1.2 billion that was originally anticipated in 2004-05. In a letter to the Governor dated December 23, 2004, the Treasurer indicated that the bond proceeds would likely total only about $800 million. In the absence of the bond sale, the $100 million in annual payments have been deposited to a designated state account.

Compact Funds Transferred to State Highway Account (SHA). Under current law, the administration may use the annual payments to

(1) repay the transportation loans or (2) support the planned bond issue that would repay the transportation loans. (The Legislature, however, may amend the law and direct that the funds be used for any other purpose.) At the end of 2005-06, the full balance in the designated account-$151 million-was transferred to SHA to repay General Fund loans-making the funds no longer available for the bond sale. As a result, the amount of bond proceeds to be generated from the sale are likely even lower than previously estimated. The

2006-07 Budget Act assumes that proceeds of the bonds will be sufficient to repay $827 million plus interest to the TCRF. Trailer bill language also modified the allocation of future bond sale revenues, providing that they would fund projects under the Traffic Congestion Relief Program. Given the uncertainty about the bond sale, however, the

2007-08 Governor’s Budget proposes that compact funds from the designated account in 2006-07 and 2007-08-$200 million-be used to repay the transportation loans. This action would further reduce the amount of any future bond.

Proposed Compacts

Which Tribes Have Proposed Compacts Or Amendments That Have Not Been Ratified By the Legislature?

Nine proposed Class III casino compacts or amendments have not been ratified by the Legislature, as listed in Figure 6. In this section, we will focus principally on the five proposed compact amendments that we refer to as the 2006 compacts, given that they recently have generated the most discussion among legislators and the public. The 2006 compacts are those with the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, the Morongo Band of Mission Indians, the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians, the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians, and the Sycuan Band of the Kumeyaay Nation.

|

Figure 6

Tribal-State Compacts That Have Not

Been Ratified by the Legislature |

|

Tribe |

County |

Number of

Class III

Machines

Allowed |

Date

Proposed By

Governor |

New

Compact or Amendment |

|

Lytton Rancheria of California |

Contra Costa |

2,500 |

8/23/2004 |

New Compact |

|

Big Lagoon

Rancheria |

Humboldta |

2,250 |

9/9/2005 |

New Compact |

|

Los Coyotes Band

of Cahuilla and Cupeno Indians |

San Diegoa |

2,250 |

9/9/2005 |

New Compact |

|

Agua Caliente

Band of Cahuilla Indiansb |

Riverside |

5,000 |

8/8/2006 |

Amendment |

|

Pechanga Band of Luiseño

Indiansb |

Riverside |

7,500 |

8/29/2006 |

Amendment |

|

San Manuel Band of Mission

Indiansb |

San Bernardino |

7,500 |

8/29/2006 |

Amendment |

|

Morongo Band of Mission

Indiansb |

Riverside |

7,500 |

8/30/2006 |

Amendment |

|

Sycuan Band of

the Kumeyaay

Nationb |

San Diego |

5,000 |

8/30/2006 |

Amendment |

|

Yurok Tribe of the Yurok

Reservation |

Del Norte and Humboldt |

99 |

8/30/2006 |

New Compactc |

|

|

|

a The

proposed compacts involve two adjacent proposed

casino facilities in Barstow (San Bernardino

County). |

|

b Due

to the similarities between these compacts with

tribes operating large casinos, we refer to them

collectively as the "2006 compacts." |

|

c This

proposed compact replaces the prior proposed compact

with the tribe, which was negotiated with the

Governor in June 2005. |

What Are the Key Provisions

Of the 2006 Compacts?

How Are They Similar to the 2004 Compacts? Earlier in this report, we compared the 1999 compacts and the 2004 compacts. The 2006 compacts are similar in many respects to the 2004 compacts. Like the 2004 compacts, the 2006 compacts would allow tribes to operate more than 2,000 slot machines. The tribes would be able to operate the machines at one, two, or three gambling facilities on Indian lands (depending on the tribe and the compact amendment involved) after negotiating with local government officials on measures to mitigate effects of casino development. The agreements contain similar language allowing state regulators to inspect casino facilities and machines. As was the case for the 2004 compacts, tribes covered by the 2006 compacts would make contributions to the state’s General Fund for the first time. While their contributions to the RSTF would increase, their payments to the SDF would end.

How Are They Different From the 2004 Compacts? Figure 7 lists some key differences between the 2004 compacts and the 2006 compacts. While the 2004 compacts allow tribes to operate an unlimited number of slot machines in exchange for certain payments to the state, the 2006 compacts allow tribes to operate up to 5,000 or 7,500 machines (depending on the compact). Legislation implementing the 2004 compacts directed a large portion of the revenues that these tribes pay to the state to repay state transportation loans. The minimum annual payments under the 2006 compacts, by contrast, would go to the General Fund. This would increase the General Fund’s share of tribal-state compact revenues substantially above current levels.

|

Figure 7

Differences Between 2004 Compacts and 2006 Compacts |

|

2004 Compacts |

2006 Compacts |

|

How many Class III slot machines are

authorized? |

|

·

Unlimited number of devices. |

·

5,000-7,500 per tribe, depending on

the compact. |

|

Which state funds receive tribal

compact moneys? |

|

·

Revenue Sharing Trust Fund (RSTF):

Payments of $2 million annually per tribe for

licenses for machines operating prior to 2004

compacts. |

·

RSTF: Payments of $2 million annually

(for all but one tribe) for licenses for machines

operating prior to 2006 compacts. $3 million

annually for

Sycuan Band. |

|

·

Special Distribution Fund (SDF): No

payments. |

·

SDF: No payments. |

|

·

Designated account for transportation

bond: Payments of about $100 million for all of the

tribes combined for

18 years. |

·

General Fund: Minimum payments of $168

million for the five tribes combined (about 10

percent of existing machines' current revenues). |

|

·

General Fund: Payments of

$8,000-$25,000 per machine added after the 2004

compacts. Estimated to average 15 percent of added

machines

revenue as of 2004. |

·

General Fund: Added payments of

15 percent of revenues from machines 2,001-5,000 and

25 percent from

machines 5,001-7,500. |

|

What are some key compact provisions

concerning labor relations? |

|

·

Signed authorization cards from

50 percent of employees certifies

union as exclusive bargaining representative. Tribal

neutrality required during organization process. |

·

Signed authorization cards from

30 percent of employees triggers secret ballot

election to determine if majority wish to certify

the union. Tribal neutrality not required. |

|

When do the compacts expire? |

|

·

December 31, 2030. |

·

December 31, 2030. |

Financial Health of SDF Would Be Affected by Proposed Compacts. Should the Legislature ratify all of the proposed 2006 compacts, SDF revenues likely would drop substantially as several tribes with large casinos would cease making payments into the SDF. Because tribal financial information is confidential, we are unable to estimate the amount of the decline with specificity, but we suspect that revenues would decline by over 50 percent. Under the terms of several of the proposed compacts, RSTF shortfalls then would be offset by tribal revenues that otherwise would be paid to the General Fund. In this scenario, the SDF’s large fund balance may be depleted within one to three years. Therefore, if the Legislature ratifies the proposed compacts, it may need to consider the current funding priorities of the SDF in statute, as well as the appropriation amounts for various purposes included in the annual budget act.

Are the Administration’s Near-Term Revenue Estimates Realistic?

General Fund Revenue Projections Overstated. The Governor’s budget assumes that annual General Fund revenues related to tribal-state compacts grow from $33 million in 2006-07 to $539 million in 2007-08 due to ratification of the 2006 compacts by the Legislature in early 2007. This projection is not realistic. If the Legislature adopted all of the 2006 compacts on an urgency basis, gross General Fund revenues from all tribal-state compacts probably would increase to at least $200 million in the first full fiscal year in which the compacts were effective, considering the minimum payment levels established in the compacts. Additional expansion of General Fund revenues would depend largely on how fast the tribes with 2004 and 2006 compacts bring new slot machines online. Given the pace at which the 2004 compact tribes have expanded and the economics of the casino industry, we expect that expansion of casino operations would be gradual, rather than sudden and dramatic. To reach the level of revenues assumed by the Governor’s budget, we estimate that the five tribes with 2006 compacts would all have to double their number of slot machines by

July 1, 2007. Over the next three to ten years, we believe that gross annual General Fund revenues from the compacts could increase to the level projected in the Governor’s budget. Such an increase in only a few months, however, is very unlikely. Even in the longer term, tribes may not opt for aggressive business expansion strategies, and it is possible that some tribes will find that it is not in their best interests to expand to the maximum number of slot machines allowed under the 2006 compacts. (Other businesses, for example, may offer a greater rate of return for some tribes and a chance for them to diversify their portfolios.)

Addressing RSTF and SDF Shortfalls Will Reduce General Fund Benefits. Offsetting the growth of General Fund revenues would be the requirement in the 2006 compacts that the state use some of the new revenues to address shortfalls in the RSTF. This requirement could increase General Fund costs in the tens of millions of dollars annually. In addition, as a result of declining SDF revenues, the Legislature could face funding shortfalls for gambling addiction, regulatory, and local government programs.

Will the Compacts Produce Billions of New Revenues to Help Eliminate the State’s Structural Deficit?

Recently proposed compacts would increase state revenues and help the state’s financial situation. In press releases announcing major compact agreements, the Governor’s office has asserted that the compacts will produce billions of dollars of new state revenues over the life of the compact. The actual annual effects on state funds from new compacts, however, tend to be in the tens of millions of dollars per year for each tribe’s compact. The billions of dollars are only possible if one sums decades worth of annual payments. As a result, while proposed new compacts would generate revenues to help lawmakers address the state’s structural deficit, these revenues will not eliminate a substantial portion of that deficit, which totals in the billions of dollars each year. Even assuming that all of the 2006 compacts are ratified and a few more similar compacts are ratified in the future, we expect that compact-related sources will provide the General Fund with less than 0.5 percent of its annual revenues for the foreseeable future.

What Are the Key Issues Involving Union Organization in the Tribes’ Casinos?

The compacts’ labor relations provisions have generated significant controversy. Employees of at least six tribal casinos are unionized. Organizing efforts have occurred at some other California casinos. In this section, we discuss the labor relations provisions of the 1999, 2004, and 2006 compacts.

1999 Compacts. Tribes with 250 or more persons employed in Class III casinos or related activities are required to adopt a “model tribal labor relations ordinance (TLRO),” as specified in the 1999 compacts. Unions are granted access to eligible employees to discuss organization and representation issues. Upon receipt of signed authorization cards from 30 percent or more of eligible employees, a secret ballot election is called to determine if a union will be certified as the exclusive collective bargaining representative of a bargaining unit of employees. The union must win a majority of those eligible employees voting in the secret ballot election. Should such a union win certification, it would then bargain collectively for employees in its bargaining unit.

2004 Compacts. The 2004 compact tribes without existing collective bargaining relationships with a union agreed to adopt an amended TLRO. Under the required amendments, a union has the option of offering a tribe that it will not strike or picket tribal facilities and will submit all issues to binding arbitration. If so, the tribe thereafter must remain neutral with regard to that union’s organization efforts. The union then may obtain signed authorization cards from 50 percent or more of eligible employees and be certified as the exclusive collective bargaining representative of the employees. In contrast to the provisions of the 1999 compacts, there are no secret ballot election requirements. This process may make it easier for unions to be certified as the exclusive representative of employees of tribal casinos and related facilities.

2006 Compacts. The compact amendments do not propose to change the tribes’ TLROs under the 1999 compacts.

Other Issues

Can Tribes Establish Casinos in Urban Areas or Outside of Their Tribal Lands?

Federal Law. The IGRA permits casino operations on Indian lands, which it defines as (1) reservation lands, (2) lands held in trust by the U.S. for benefit of an Indian tribe or individual, or (3) certain specified lands over which an Indian tribe exercises governmental power. (The State Constitution also provides that tribal casinos in California must be on Indian lands “in accordance with federal law.”) Historically, ancestral lands of many tribes have been taken from them by policy or force. Tribes, therefore, may seek to rebuild a land base by having the federal government acquire lands in trust for their use through a lengthy, complex process. In some cases, this can mean that tribes seek to establish a land base in areas (such as urban or suburban areas) not associated with the tribes in recent history. Throughout the nation and in California, conflicts occasionally have arisen between tribes wishing to establish a casino (particularly on recently acquired trust lands) and nearby communities resisting such development.

Recent Trends. The rules governing where tribes may operate casinos are extraordinarily complex. In recent years, however, the general trend seems to have been for federal and state policymakers to make it more difficult for tribes to open casinos on recently acquired trust lands. The U.S. DOI has not approved many pending requests of tribes to acquire trust lands for the purpose of establishing casinos and has established rules requiring environmental reviews and support from nearby community leaders before approval will be granted. In 2005, the Governor released his policy for tribal gambling compacts, which declared his general opposition to

(1) “proposals for the federal acquisition of lands within any urbanized area where the lands sought to be acquired in trust are to be used to conduct or facilitate gaming activities” and

(2) “compacts where the Indian tribe does not have Indian lands eligible for Class III gaming.” Opponents have criticized several proposed compacts with California tribes for their provisions to establish casinos on these types of lands. Such criticisms have been one reason why the Legislature has not yet ratified some proposed compacts.

What Powers Does the State Have to Ensure That Tribes Meet Their Obligations Under the Compacts?

Compacts Limit CGCC’s Powers. The compacts limit CGCC’s authority to monitor and audit tribal operations. The compacts, for example, limit CGCC’s abilities to inspect slot machines-in several compacts, to no more than four times per year, with notice to the tribe prior to the inspection. In the commission’s budget request for additional staffing for 2006-07, CGCC officials described several other ways that the compacts and existing practices limit regulators’ monitoring of tribal financial operations, as summarized below:

- Limited access to tribal financial reports and information related to internal controls over slot machines and machine revenues.

- Lack of periodic casino financial reports prepared by independent certified public accountants (CPAs) to evaluate and perform risk assessments.

- Lack of internal control reports prepared by both independent CPAs and casino internal audit departments.

- Inability to conduct interim walk-through audits (as Nevada regulators do).

- Inability to have audit personnel at each casino 24 hours a day, 7 days a week (as in New Jersey), in order to test devices and report on changes to internal controls.

- Differing sets of requirements for different tribes, as opposed to Nevada and New Jersey’s uniform legal authorities and regulations.

Legislature Expanded CGCC in 2006-07. The CGCC administers the RSTF and SDF and has the principal responsibility for monitoring and auditing Class III casino activities. In 2006, the Legislature approved an expansion of CGCC’s divisions that license casino employees and suppliers and test slot machines to ensure compliance with compact provisions and regulations. The CGCC’s authorized number of staff positions increased from 42 to 63 as a result of the Legislature’s actions (with many of the new positions approved on a limited-term basis to evaluate the effects of the expansion). The commission’s operations budget increased from $6.7 million in 2005-06 to $10.5 million in 2006-07 principally due to this expansion of staff. (This entire budget currently is supported by the SDF and a special fund supported by fees from the state’s cardrooms, which CGCC also regulates.) The Governor’s budget for 2007-08 proposes no additional expansions in CGCC’s staff.

How Much Does the State Provide to Prevent and Treat Problem Gambling?

SDF Expenditures. The bulk of state funding for problem gambling prevention activities comes through annual appropriations from the SDF to DADP’s Office of Problem Gambling. In 2006-07, this appropriation totals $3 million. To date, much of this funding has been used to provide grants to problem gambling telephone services (including publicity for these lines) and to fund research activities related to problem gambling in the state. In some cases, local mitigation agreements or local SDF grants are also used to fund efforts to prevent gambling addiction.

New Funding for Treatment. Chapter 854, Statutes of 2006 (AB 1973, Bermúdez), requires cardrooms in the state to pay an additional $100 per licensed table, which will be available to be appropriated to community-based organizations that provide gambling addiction treatment. This new fee is expected to generate $150,000 per year. The Governor’s budget, however, does not include an appropriation for these funds in 2007-08.

Have the Socioeconomic Conditions of California Tribes Improved?

Background. As described earlier, improvement of tribal living conditions was the principal purpose for the enactment of IGRA by Congress. The socioeconomic gaps between American Indians living on reservations and the rest of the national population remained significant, as of the 2000 U.S. Census. Per capita income at that time was less than one-half of the U.S. level, and family poverty was three times that of the rest of the country.

For Some Tribes, Conditions Have Improved. While Census and other authoritative demographic data focused on tribal members is limited, it is clear that the expansion of tribal casinos has dramatically improved socioeconomic conditions for some tribal members in California. These positive economic effects seem to be concentrated among members of tribes with some of the largest casinos. Added together, all of the casino tribes represent just 9 percent of California’s residents identified as American Indians by the 2000 Census, according to the California Research Bureau.

For Most Tribal Members, Unclear That Casinos Have Helped Much. The majority of California tribal members do not benefit directly from a casino. While federally recognized tribes receive at least $1.1 million annually through the RSTF, this amount has eroded by inflation by roughly 20 percent since 1999. In addition, particularly for large tribes (sometimes with hundreds or thousands of members and large geographic territories), the amount may have a limited effect on the socioeconomic conditions of most members.

Conclusion

Previously approved tribal-state compacts bind the state for the coming decades. As the Legislature considers several proposed compact amendments in 2007 (as well as any future proposed compacts), however, it faces several key fiscal and policy issues, including:

- How much more should the tribal casino industry expand in California? How many more slot machines and casinos should be authorized?

- What payments should tribes make to the state and local governments?

- What should compacts require with regard to labor relations at tribal casinos?

- Do compacts provide for effective state regulation to ensure that tribes meet their financial obligations to state and local governments?

- Should the statutory method of allocating funds from the SDF be changed in the future?

- Are the tribal-state compacts effective in meeting IGRA’s goals to strengthen tribal governments and improve economic opportunities for tribal members?

|

Acknowledgments This report was prepared by

Jason Dickerson and reviewed by

Michael Cohen. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan office which provides

fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature.

|

LAO Publications To request publications call (916) 445-4656.

This report and others, as well as an E-mail

subscription service

, are available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is

located at 925 L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page