November 11, 2008

Overview of the Governor’s Special Session Proposals

Summary

Plummeting Revenues Yield $28 Billion Hole

State Faces $27.8 Billion Shortfall. We concur with the administration’s assessment that the state’s struggling economy signals a major reduction in expected revenues. Combined with rising state expenses, we project that the state will need $27.8 billion in budget solutions over the next 20 months.

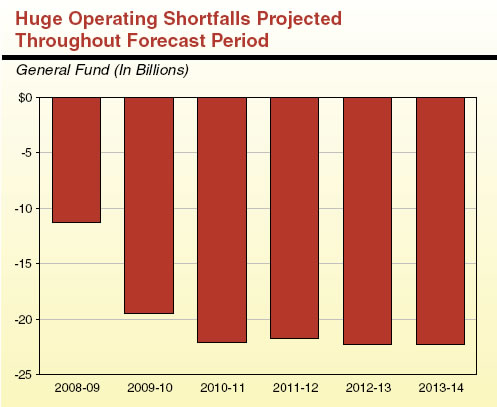

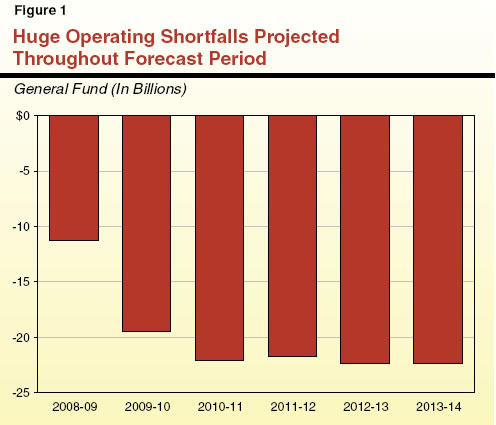

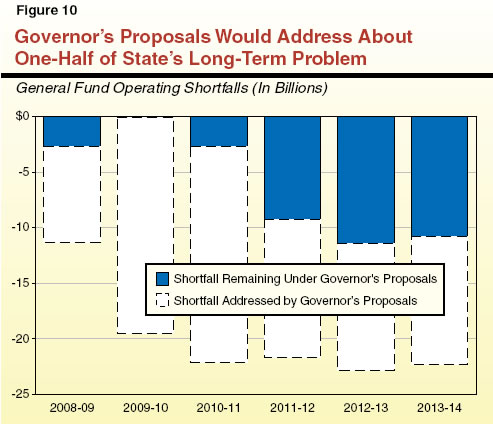

Long–Term Outlook Similarly Bleak. The state’s revenue collapse is so dramatic and the underlying economic factors are so weak that we forecast huge budget shortfalls through 2013–14 absent corrective action. From 2010–11 through 2013–14, we project annual shortfalls that are consistently in the range of $22 billion, as shown below.

Governor’s Framework Has Many Positive Aspects

The Governor’s special session proposals are a comprehensive and ambitious package. Among the positive aspects of its approach are:

- Realistic Numbers. The Governor’s package would achieve its targeted savings and close the budget gap for 2009–10.

- No Borrowing. The administration has avoided putting forward any new budgetary borrowing proposals.

- Long–Lasting Solutions. The Governor’s proposals would provide budgetary relief for at least three years and permanently in many cases.

- Balanced Approach. The Governor has put forward a mix of revenue increases and spending reductions. The magnitude of the budget shortfall is too great to close on only one side of the ledger—revenues must be increased and expenditures must be decreased.

Early Action Is Critical

With the expected slow recovery of the state’s economy, it is imperative that the Legislature attack the grim budget problem aggressively, making permanent improvements to the state’s fiscal outlook. If the state has any hope of developing a fiscally responsible 2009–10 budget, it must begin acting now. The state will need to make major ongoing reductions to current service levels and impose major increases in revenues in order to achieve fiscal balance.

Legislature Should Pursue Alternative Approaches in Some Areas

We are supportive of the administration’s general framework for closing the budget gap. The specifics of the proposals, however, raise a number of policy and fiscal issues. While there are few avenues remaining that would achieve budgetary savings without some negative consequences, we have identified alternate revenue increases and program reductions that would minimize harm to the state’s taxpayers and core programs

This report provides an overview of the issues facing the Legislature in bringing the 2008–09 and 2009–10 budgets into balance. It begins with a discussion of the size and scope of the state’s fiscal problems. It then describes and evaluates the administration’s proposed solutions, which include broad–based tax increases and spending reductions. It concludes with advice to the Legislature as it begins its special session and provides alternative budget solutions to consider.

The Reemergence of a Huge Budget Problem

As was the case in 2007–08, the Governor has called the Legislature into special session to address a multibillion dollar shortfall in the current–year budget. In this section, we describe the administration’s view of the size of the shortfall and then provide our own assessment.

Governor’s Problem Statement

In September, when the Governor signed the 2008–09 Budget Act, the state had a projected reserve of $1.7 billion. Less than two months later, the administration reports that it expects revenues for the year to fall short of the budget’s projections by $10.7 billion. Combined with a prior–year revenue reduction of nearly $600 million, it expects the state to end the 2008–09 fiscal year with a $9.5 billion shortfall if no corrective actions are taken.

The administration has also adjusted its previous projection of 2009–10 revenues downward by $13 billion. Over the next 20 months, therefore, the state would need to adopt $22.5 billion in budget solutions to keep the state in the black. The administration notes that its projection of a $22.5 billion shortfall does not reflect a complete update of programs’ caseloads and other spending factors. The administration plans to conclude such an update in time for the release of the Governor’s budget in January.

LAO Assessment of the Budget Problem

Our office has completed a new fiscal forecast based on current trends, including both a new economic and revenue forecast, as well as updated spending estimates. We summarize our new forecast below, and we will provide more of the details behind our forecast next week in our annual California’s Fiscal Outlook publication.

Governor’s New Revenue Estimates Are Reasonable. We concur with the administration’s assessment that the state’s struggling economy signals a major reduction in expected revenues. Our revised revenue forecast is very similar to the administration’s—down $24.5 billion over 2008–09 and 2009–10 combined. We do, however, have some differences in specific tax estimates, as well as variations in the timing of the revenue decline. Specifically, we project about $2 billion more than the administration in current–year revenues but $2.7 billion less in budget–year revenues. We compare our economic and revenue forecasts in detail in the next section of this report.

Spending Factors Make Problem Even Greater. Our updated spending forecast, compared to the 2008–09 Budget Act, also contains negative factors widening the state‘s budget shortfall. By far, the largest adjustment is higher state spending due to an almost $1.5 billion reduction in the expected property taxes to be received by school districts over three fiscal years—principally caused by the rapid decline in the state’s housing market. Other major adjustments include higher expected caseloads in a number of health and social services programs, higher firefighting costs, and less–than–assumed savings from unallocated reductions.

Projected Budget Shortfall of $28 Billion. Even at the time the 2008–09 budget was signed, policymakers acknowledged a multibillion dollar shortfall was expected for the upcoming 2009–10 budget. Combined with the steep revenue drop and some spending increases, that shortfall has grown dramatically to over $19 billion. When combined with the current–year deficit, we project that the state will need to close a $27.8 billion gap over the next 20 months.

Long–Term Outlook. Our fiscal forecast also looks beyond the 2009–10 budget year to see where the state’s finances are headed in the longer term, through 2013–14. In some of our prior forecasts, the state’s finances improved over the forecast period as revenue growth outpaced spending trends. In contrast, under our current forecast, the state’s revenue collapse is so dramatic and the underlying economic factors are so weak that we forecast huge budget shortfalls through 2013–14 absent corrective action. Even once revenues begin to rebound in the later years of the forecast, some fast–growing spending programs (such as Medi–Cal, some social services programs, and infrastructure debt–service payments) would prevent the state from reducing its annual imbalance between revenues and spending. As shown in Figure 1, from 2010–11 through 2013–14, we project annual shortfalls that are consistently in the range of $22 billion. Our long–term current–law forecast does not include the potential effects of ballot measures that will be placed before the state’s voters in 2009. The nearby box describes their potential effects.

Potential Impact of 2009 Special Election

As part of the 2008–09 budget package passed in September, the Legislature put forward two propositions that would go before the state’s voters at a special election planned for the first half of 2009. If approved by voters, these measures—dealing with the lottery and budget reform—would have significant effects on the state’s fiscal condition beginning in 2009–10 and throughout our forecast period. Because both of these proposals have yet to be approved, we have not included their effects in our forecast of the budget problem under current law.

Lottery. The state’s current plan envisions securitizing lottery profits in order to benefit the General Fund in the short term—$5 billion each in 2009–10 and 2010–11—through the sale of lottery bonds. Thus, if the measure is approved by the voters and the state successfully sells the first batch of lottery bonds, the state would achieve a budgetary solution of $5 billion in 2009–10. Yet, the lottery plan could cost the state nearly $1 billion annually by 2013–14—after accounting for debt–service payments on the bonds and General Fund increases to educational entities (which would no longer receive lottery profits).

Budget Reform. The budget reform measure would redirect, in specific circumstances, General Fund revenues to a restricted reserve account and make the funds harder to access. The measure, therefore, could make balancing the budget more difficult over the forecast period—by limiting the availability of funds to help balance the budget. The ability to forecast its precise effect on the state budget, however, is difficult. This is because the impact would depend on (1) the state’s ability to accurately forecast revenues and (2) growth of both revenues and spending. |

Economic and Revenue Forecast

In this section, we provide more details on the deteriorating economic and revenue outlook.

Economic Forecast

Sharply Deteriorating Economy. The near–term outlook for both the national and state economies is extremely negative. For example, there have been declines in employment levels, consumer spending, durable goods orders, consumer confidence, industrial production, and car sales. Unemployment rates have shot up. The nation’s gross domestic product contracted in the third quarter of 2008—with a much larger decline this quarter all but assured. Likewise, the housing market continues to be very depressed, the foreign economies that we trade with have slowed, the condition of governmental budgets has deteriorated, and the financial and credit markets have yet to recover from their recent near collapse.

Economic Forecast. The current economic forecasts of our office and the Department of Finance (DOF) are very similar, but with our projections being slightly more negative in a few areas. Our forecasts both reflect the current consensus view that both the national and state economies will experience very subdued performance during most of 2009, with some modest recovery in 2010, and further strengthening in 2011. The outlook, however, is clouded with considerable uncertainty at this time, and there are significant downside risks.

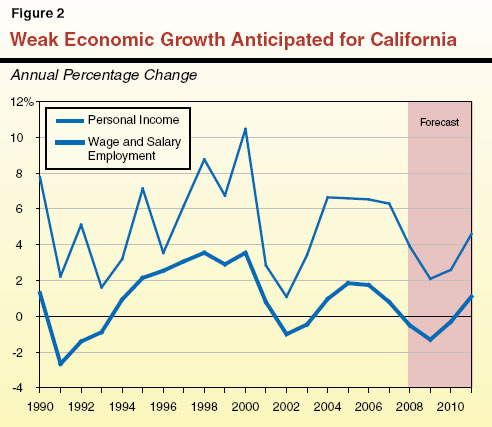

Figure 2 summarizes our revised forecasts for key economic variables for California—growth in personal income and employment. We project that:

- Personal income growth will drop from 6.3 percent in 2007 to just 3.9 percent in 2008, 2.1 percent in 2009, and 2.6 percent in 2010. In the following year, we project that growth will firm up to 4.6 percent, and rise to the 5.5 percent to 6 percent range thereafter.

- Employment will fall from 2008 through 2010, including a 1.3 percent decline in 2009. Thereafter, we expect a return to positive growth of 1.1 percent in 2011 and around 2 percent thereafter.

The figure also shows how California’s projected performance compares to income and job growth in previous years, including the recessions experienced in the early 1990s and 2000s.

Revenue Projections

The economic events of the past two months make it clear that the revenue assumptions underlying the 2008–09 Budget Act were too optimistic. Even before the crisis in the financial and credit markets occurred, revenues were falling below expectations. September revenue data, for example, revealed a major shortfall in estimated payments for both the personal income tax (–10 percent) and corporate tax (–22 percent). The weakness in estimated payments, along with a $200 million shortfall in September sales and use tax receipts, resulted in revenues from the “Big 3” taxes falling almost $1 billion short of budget estimates for the month.

Administration’s Revenue Forecast. Figure 3 shows DOF’s revised revenue projections for 2007–08 through 2009–10 and compares them to the 2008–09 budget estimates. For the three years combined, the estimates are down $24.2 billion. Specifically:

- In 2007–08, revenues were down $567 million. This reduction primarily reflects more recent data on final receipts and accruals for the year.

- In 2008–09 and 2009–10, the administration projects revenues that are more than $10 billion lower in each year. Specifically, DOF estimates revenues will fall by $10.7 billion in 2008–09 and $13 billion in 2009–10.

Figure 3

Revised Administration Revenues |

(In Millions) |

|

2007-08 |

|

2008-09 |

|

2009-10 |

Revenue Source |

Budget Act |

Revised |

Difference |

|

Budget Act |

Revised |

Difference |

|

Budget Act |

Revised |

Difference |

Personal Income Tax |

$54,380 |

$54,289 |

-$91 |

|

$55,720 |

$48,479 |

-$7,241 |

|

$55,863 |

$48,824 |

-$7,039 |

Sales and Use Tax |

26,813 |

26,613 |

-200 |

|

27,111 |

25,486 |

-1,625 |

|

29,248 |

25,234 |

-4,014 |

Corporation Tax |

11,926 |

11,690 |

-236 |

|

13,073 |

11,426 |

-1,647 |

|

11,982 |

10,731 |

-1,251 |

Other revenues and transfers |

9,908 |

9,868 |

-40 |

|

6,087 |

5,942 |

-145 |

|

5,516 |

4,799 |

-717 |

Totals |

$103,027 |

$102,460 |

-$567 |

|

$101,991 |

$91,333 |

-$10,659 |

|

$102,609 |

$89,588 |

-$13,021 |

The administration’s 2009–10 revenue projection suggests total revenues will fall $1.7 billion below its revised 2008–09 level. This year–to–year reduction, however, is caused primarily by the fact that new revenue provisions adopted in the 2008–09 Budget Act (totaling about $4 billion) are primarily one–time in nature. As a result, the administration’s 2009–10 baseline projection—once the one–time revenues are accounted for—contains a modest increase of about $2 billion.

LAO Revenue Projections Are Similar. As with our economic forecast, our revenue projection also is quite similar to that of the administration. Figure 4 displays our forecast for 2008–09 and 2009–10 compared to the administration’s estimates. Over the two years combined, our estimate of revenues is $800 million lower. In the current year, we project revenues will total $93.2 billion, or $1.9 billion higher than the administration. Compared to DOF, our somewhat higher projection in 2008–09 stems from both methodological estimating differences and our slightly–more–optimistic assumptions about the tax bases involved. In contrast, our estimate of budget–year revenues is $2.8 billion below DOF’s projection—as a result of more pessimistic views of capital gains income and corporate profits. Despite the differences on a year–to–year basis, the bottom line is the same—the state faces a dramatic drop in revenues approaching $25 billion over the next two years.

Figure 4

Comparison of Revised DOF and LAO Revenues |

(In Millions) |

|

2008-09 |

|

2009-10 |

Revenue Source |

DOF |

LAO |

Difference |

|

DOF |

LAO |

Difference |

Personal Income Tax |

$48,479 |

$50,265 |

$1,786 |

|

$48,824 |

$46,339 |

-$2,485 |

Sales and Use Tax |

25,486 |

25,381 |

-105 |

|

25,234 |

26,100 |

866 |

Corporation Tax |

11,426 |

12,023 |

597 |

|

10,731 |

9,102 |

-1,629 |

Other revenues and transfers |

5,942 |

5,580 |

-362 |

|

4,799 |

5,294 |

495 |

Totals |

$91,333 |

$93,248 |

$1,916 |

|

$89,588 |

$86,835 |

-$2,753 |

Components of the Governor’s Plan

The Governor’s ambitious special session plan has two primary components—a package of tax increases and a series of spending reductions. The administration has also made proposals related to cash management, stimulating the economy, unemployment insurance, and mortgages. We describe these proposals below and summarize them in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Governor’s Special Session Proposalsa |

(In Millions) |

|

2008‑09 |

2009‑10 |

Revenue Increases |

|

|

Increase sales tax by 1.5 cents for three yearsb |

$3,540 |

$6,643 |

Expand sales tax to some services |

357 |

1,156 |

Impose oil severance tax |

530 |

1,202 |

Raise alcohol tax by a nickel a drink |

293 |

585 |

Subtotals, Revenue Increases |

($4,720) |

($9,586) |

Expenditure Savings |

|

|

Reduce Proposition 98 spending |

$2,500 |

$729 |

Reduce higher education spending (unallocated) |

132 |

132 |

Reduce regional center rates by 3 percent |

34 |

60 |

Restrict Medi-Cal eligibility and benefits |

142 |

715 |

Reduce SSI/SSP grants |

391 |

1,176 |

Eliminate California Food Assistance Program |

— |

30 |

Reduce CalWORKs grants and implement reforms |

274 |

847 |

Reduce IHSS state wage participation and target services |

118 |

357 |

Implement parole reform and other corrections savings |

78 |

678 |

Eliminate funding for public safety grant programs |

250 |

501 |

Eliminate state funding to transit agencies |

230 |

306 |

Furlough state workers and reduce other costs |

320 |

556 |

Eliminate funding for the Williamson Act |

35 |

35 |

Subtotals, Expenditure Savings |

($4,504) |

($6,120) |

Total Solutions |

$9,224 |

$15,706 |

|

a Scoring reflects administration's estimates. |

b Sales tax revenues are the net benefit to the General Fund, after accounting for higher spending

required under Proposition 42. |

Tax Increases

In response to the expected drop in revenues, the administration’s special session plan proposes four new tax changes that would significantly increase General Fund revenues in 2008–09 and 2009–10. In total, the administration expects its new proposals to bring in $4.7 billion in the current year and $9.6 billion in the budget year.

Sales Tax Increases. The centerpiece of the administration’s revenue plan is a three–year, 1.5 percent increase in the sales and use tax rate, which would yield $3.5 billion in 2008–09 and $6.6 billion in 2009–10. (Actual sales tax receipts would be somewhat higher, but offset by increased costs under Proposition 42.) This change would boost the current base sales tax rate from 7.25 percent to 8.75 percent beginning January 1, 2009. The administration also proposes to extend sales and use taxes to selected services, including car and other repair services, veterinarian services, golf, amusement parks, and sporting events. This proposal is projected to garner an additional $357 million in 2008–09 and $1.2 billion in 2009–10.

Oil Severance Tax. The administration also proposes to levy a new 9.9 percent oil severance tax on most oil produced in California. According to DOF, stripper wells—which are defined as producing less than ten barrels a day—would be exempted from the proposal under some circumstances. The administration estimates the new tax would generate $530 million in 2008–09 and $1.2 billion in 2009–10.

Alcohol Tax. The final tax increase proposed by the administration would increase the existing alcohol excise tax that is levied on beer, wine, and distilled spirits. The proposal would add 5 cents per drink, bringing in an estimated $293 million in the current year and $585 million in the budget year. Current excise taxes on alcohol are “per–unit” taxes—that is, they are based on a physical unit of the goods taxed (such as a gallon) rather than its price or value (as with the sales tax, for example). Beer, wine, and sparkling hard cider are currently taxed at 20 cents per gallon, champagne and sparkling wine at 30 cents per gallon, and distilled spirits at $3.30 per gallon. The proposal would add a tax of 30 cents to a six–pack of beer, about 25 cents to a bottle of wine, and roughly $1.07 to a quart of distilled spirits.

Administration Estimates Are Reasonable, But Potentially Low. Given the difficulty in making projections for new taxes, our review suggests the DOF revenue estimates associated with its tax proposals are generally reasonable. If anything, however, we believe they may have understated the amount of revenue that would actually be generated. Specifically, our estimate of the revenue impact of the Governor’s tax proposals indicates that actual revenues may exceed DOF estimates by as much as a combined $1 billion over the two years involved.

Spending Reductions

Reduced Proposition 98 Funding For K–14 Education

Given the substantial drop in General Fund revenues, the Governor proposes a sizeable reduction in Proposition 98 funding, which supports K–12 education and community colleges. As shown in Figure 6, the Governor proposes to reduce Proposition 98 General Fund spending in 2008–09 by $2.5 billion. For K–12 education, the Governor proposes to reduce funding by $2.2 billion—a decline of slightly more than 4 percent from the 2008–09 Budget Act level. For the California Community Colleges (CCC), the Governor proposes to reduce funding by $332 million—a decline of slightly more than 5 percent. (The administration has not updated its estimate of property tax revenues since the 2008–09 Budget Act was adopted. We estimate property tax revenues have dropped substantially, which automatically adds to the state’s General Fund shortfall.)

Figure 6

Governor Proposes $2.5 Billion Midyear Reduction in Proposition 98 Funding |

2008-09

(Dollars in Millions) |

|

Budget Act |

Special

Session |

Difference |

Percent |

K-12 education |

$51,620 |

$49,453 |

$2,168 |

4.2% |

California Community Colleges |

6,359 |

6,027 |

332 |

5.2 |

Other |

106 |

106 |

— |

— |

Totals |

$58,086 |

$55,586 |

$2,500 |

4.3% |

Almost Entire Reduction Applied to Revenue Limits/Apportionments. Figure 7 lists the specific Proposition 98 reductions proposed in the Governor’s special session plan. As shown in the figure, the Governor proposes to withdraw the 0.68 percent cost–of–living adjustment (COLA) that the 2008–09 Budget Act had provided to K–12 revenue limits and CCC apportionments. Base reductions of $1.8 billion for K–12 revenue limits and almost $300 million for CCC apportionments are then proposed. In addition to the revenue limit/apportionment reduction, the Governor’s proposal captures a small amount of savings from programs that have lower–than–expected expenditures.

Figure 7

Governor’s Proposed Proposition 98 Midyear Reductions |

(In Millions) |

|

|

Rescind COLAa |

$284 |

K-12 revenue limits |

(244) |

California Community College (CCC) apportionments |

(40) |

Reduce base funding |

2,083 |

K-12 revenue limits |

(1,791) |

CCC apportionments |

(292) |

Capture savings from current year |

132 |

Child care programs |

(97) |

K-12 programs |

(35) |

Total |

$2,500 |

|

a The 2008-09 Budget Act provided a 0.68 percent cost-of-living adjustment (COLA). |

To Mitigate Cut, Plan Provides Much More Flexibility. The Governor’s proposal contains several limited–term flexibility provisions designed to help districts respond to a sizeable midyear reduction. The administration proposes loosening many major fiscal requirements now placed on districts. To backfill the proposed revenue limit cut, the Governor would allow districts to transfer unlimited amounts and completely drain prior–year ending balances from virtually any categorical program. His flexibility proposals also include cutting reserves for economic uncertainties in half, reducing routine maintenance reserves from 3 percent to 2 percent, and suspending local deferred maintenance matches.

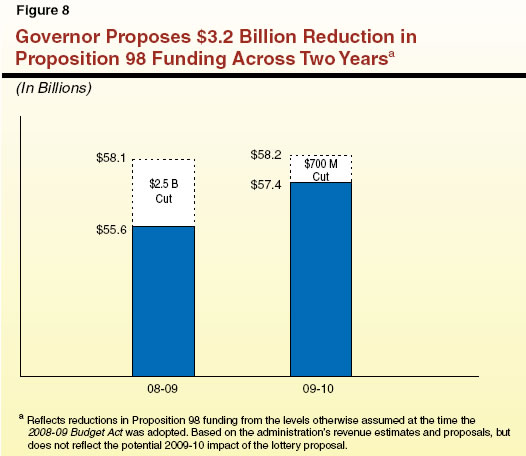

Across Two Years, Governor’s Proposed Reductions Total More Than $3 Billion. Figure 8 shows the 2009–10 impact of the Governor’s proposed midyear reduction. If the entire $2.5 billion reduction were made in 2008–09, the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee in 2009–10 would be $57.4 billion (assuming all of the Governor’s revenue estimates and proposals). This reflects a programmatic cut of about $700 million. Across the two years, therefore, the Governor’s proposed reductions total $3.2 billion from the funding levels assumed at the time the 2008–09 Budget Act was adopted.

Other Spending Reductions

The administration’s other special session spending reduction proposals include significant operational changes and restrictions of eligibility and benefits. Key proposals are described below.

- Health. Under the special session proposals, fewer families could apply to the Medi–Cal Program. The income level that determines eligibility for certain families would be reduced—resulting in $340 million in General Fund savings upon full implementation. The Medi–Cal benefits provided to certain immigrants would be limited, and the amount that some aged, blind, and disabled recipients pay out of pocket before they can receive Medi–Cal benefits would be increased. The administration also proposes to eliminate certain Medi–Cal benefits, including dental services for adults. Certain reimbursements to regional center providers would be reduced by 3 percent, effective December 1, 2008.

- Social Services. The administration proposes to reduce—to the federal minimum—grants for low–income aged, blind, and disabled Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Program (SSI/SSP) recipients. In California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs), savings also would be achieved by reducing grants by 10 percent and by limiting benefits beyond five years for some recipients, in addition to other proposed reforms. In the In–Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program, the state’s participation in wage costs for workers would be reduced and access to domestic services would be restricted to recipients rated as most needing assistance.

- Criminal Justice. Under the special session proposal, inmates who did not have current or prior convictions for violent, serious, or certain sex crimes would not receive parole supervision after release from prison. This proposal combined with other changes, such as expanding inmate credits and increasing the threshold value for prosecuting property crimes as a felony, would save $78 million in 2008–09 and $678 million in 2009–10.

- Higher Education. For the university systems (University of California, California State University, and Hastings College of the Law), the administration proposes unallocated reductions totaling $132 million. This proposal would reduce funding to the levels originally proposed by the Governor in January 2008.

- Transportation. The administration proposes to (1) eliminate the State Transit Assistance program and (2) use all spillover revenues to benefit the General Fund on an ongoing basis.

- Employee Compensation Savings. Savings are proposed from furloughing most state employees for one day per month through the end of 2009–10—the equivalent of a 4.62 percent reduction in pay. (Employees’ retirement credit and health, dental, and vision benefits would not be affected.) In addition, the measures would eliminate the Lincoln’s Birthday and Columbus Day holidays for state employees, eliminate premium pay for hours worked on remaining state holidays, and change methods for computing employee overtime. In general, these changes would take effect outside of the collective bargaining process. Certain provisions, such as the furlough proposal, would not apply to California Highway Patrol officers, who are part of the only bargaining unit operating under a current collective bargaining agreement.

- Local Government Funding. Other proposals include reducing the amount of funding provided to local governments for various public safety grants by $250 million in 2008–09 and $501 million in 2009–10. Most of the General Fund spending reductions would be backfilled with funding from the portion of vehicle license fee (VLF) revenues currently dedicated to Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) administrative costs. In addition, the administration proposes to eliminate state reimbursements to local governments for the loss of property tax revenues under the Williamson Act open space program.

Most Estimates of Savings Reasonable. Most of the administration’s estimates of savings for its proposals are reasonable. We have identified a few exceptions. For instance, our analysis indicates that a proposal to change application procedures for undocumented immigrants obtaining Medi–Cal emergency services is unlikely to result in the level of savings assumed by the administration. On the other hand, we believe the elimination of state funding for transit operations will result in significantly greater General Fund savings in 2009–10.

Cash Management

Because a large portion of state revenues—particularly personal income taxes—is received late in the fiscal year, the state typically must borrow several billion dollars each fall through issuing securities called revenue anticipation notes (RANs). The RANs then are paid back in the spring following receipt of April income tax payments. In October, the State Controller’s Office determined that the state needed to issue $7 billion of RANs to ensure timely cash payments through the end of 2008–09. The financial market crisis and the state’s deteriorating financial condition, however, prevented officials from issuing the full $7 billion of RANs. Instead, a smaller $5 billion RAN borrowing was executed.

New Cash Flow Pressures for 2008–09. The state’s economic outlook and deteriorating budgetary situation reduce the chance that investors will provide the remaining $2 billion of RAN proceeds requested by the Controller. This situation also places more stress on the state’s cash flows than previously anticipated. We concur with the administration’s estimate that, even if the state were able to obtain $2 billion more in RAN proceeds from investors during 2008–09, the General Fund still would be unable to meet all of its payment obligations on a timely basis without additional remedial action by the Legislature.

Administration’s Cash Flow Proposals. To address this situation, the Governor proposes $10 billion of budgetary and other measures that would improve the state’s cash flow situation through at least the end of 2008–09.

- Revenue proposals and budgetary reductions (discussed earlier) would provide over $8 billion of estimated General Fund cash flow relief by the end of 2008–09.

- Statutory measures to allow the General Fund to temporarily borrow from available special fund and other fund balances would provide around $2 billion of additional cash flow cushion.

The administration forecasts that these measures would allow the General Fund to preserve a minimum cash cushion of over $3 billion (slightly more than the targeted minimum of $2.5 billion) at the end of each of the last seven months of the 2008–09 fiscal year.

Legislature May Need Additional Solutions. Despite all of these remedial measures, the estimated cash cushion at the end of 2008–09 would be several billion dollars less than was on hand at the end of 2007–08. The General Fund typically needs a large cash cushion at the end of June because the months between July and October are ones when state expenditures far exceed state revenues. In order to ensure that the General Fund can meet its payment obligations in the summer of 2009, the Legislature may need to enact additional cash management solutions—above and beyond those now presented by the administration—either in the special session or in the first part of 2009. While additional borrowing (through mechanisms like revenue anticipation warrants) may be available to assist with cash flow during the summer of 2009, the fragile condition of the financial markets makes reliance on such borrowing risky, as well as expensive.

Other Proposals

The Governor’s call for a special session was quite broad and included a number of additional policy proposals.

Economic Stimulus Measures. The administration hopes to help stimulate the economy through a variety of means. The administration proposes to accelerate the allocation of bond funds from measures previously approved by voters. In addition, the administration seeks to ease a variety of hospital construction and workplace regulations. It also seeks to provide tax incentives for film and television productions (although any lost state revenues from these incentives are not part of the Governor’s fiscal plan). Finally, the administration proposes changes related to home mortgages that would aim to reduce the frequency of foreclosures.

Unemployment Insurance (UI) Trust Fund. Because benefit payments exceed the UI taxes collected from employers, the Employment Development Department (EDD) estimates that the UI trust fund will end calendar year 2009 with a deficit of $2.4 billion, rising to $4.9 billion by the end of 2010. (An existing federal loan program, with required interest payments, will enable California to continue making benefit payments while the fund is experiencing a deficit.) Effective January 2010, the Governor proposes to increase the employer taxes for each worker and to slightly decrease UI benefits for those who become unemployed. The tax increase could as much as double the tax paid per employee, depending on the stability of the employer’s workforce. The EDD estimates that these changes would restore solvency to the UI trust fund in 2011.

The Bottom Line on the Governor’s Special Session Proposals

We have examined the implications of the Governor’s special session proposals using our updated revenue and spending forecast. In other words, if the Legislature adopted all of the Governor’s proposals, we have forecasted what the budget would look like.

2008–09 and 2009–10 Outlook. As noted above, we have differences with the administration in the magnitude of benefit that some of its solutions will generate. On net, however, we project that the Governor’s special session proposals would provide a similar level of benefit. Combined with $5 billion in assumed benefit from borrowing from lottery profits (pending voter approval and successful marketing of the bonds), the Governor’s approach would essentially close the projected $28 billion gap—leaving a minimal $169 million reserve as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9

LAO Projection of General Fund Condition

Under Governor's Proposalsa |

(In Millions) |

|

2007‑08 |

2008‑09 |

2009‑10 |

Prior-year fund balance |

$4,777 |

$3,786 |

$1,110 |

Revenues and transfers |

102,649 |

98,332 |

97,703 |

Total resources available |

$107,426 |

$102,118 |

$98,813 |

Expenditures |

$103,640 |

$101,008 |

$97,759 |

Ending fund balance |

$3,786 |

$1,110 |

$1,054 |

Encumbrances |

$885 |

$885 |

$885 |

Reserve |

$2,901 |

$225 |

$169 |

Budget Stabilization Account |

— |

— |

— |

Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties |

2,901 |

225 |

169 |

|

a Assumes enactment of all special session proposals and voter adoption of lottery securitization. |

Long–Term Outlook. As noted above, the Legislature begins the special session with projected annual shortfalls in the range of $22 billion through 2013–14. The Governor’s proposals would help address those shortfalls by permanently providing increased revenues and by reducing spending. The largest proposed solution—the increase in the sales tax rate—however, would end after three years. Combined with the expected end of available lottery borrowing after 2010–11, the state’s budget problem would grow once again to between $9 billion and $11 billion in the future, as illustrated in Figure 10. In other words, the Governor’s proposals would cut these years’ shortfalls in about half.

How Should the Legislature Approach the Budget Problem?

The rapid deterioration of the state’s economy and revenues follows seven years of budget problems of various degrees. The Legislature and the Governor have tended to close these prior gaps principally with borrowing and other one–time solutions. Consequently, the state faces its newest budget struggle burdened with more than $18 billion in outstanding budgetary borrowing from past decisions. With the expected slow recovery of the state’s economy, it is imperative that the Legislature attack the budget problem quickly and aggressively, making permanent improvements to the state’s fiscal outlook.

Governor’s Framework Offers Many Positive Aspects

The Governor’s special session proposals are a comprehensive and ambitious package. Among the positive aspects of its approach are:

- Realistic Numbers. The Governor’s revenue forecast is a realistic assessment of expected state resources. Despite some differences in our scoring of the Governor’s proposed solutions, the overall package would achieve its targeted savings and close the budget gap for 2009–10.

- No Borrowing. The administration has avoided putting forward any new budgetary borrowing proposals that would simply push the budget problem into 2010–11 or beyond.

- Long–Lasting Solutions. With little prospect of a quick economic recovery, the state’s budget problems demand long–term solutions. The Governor’s proposals would provide budgetary relief for at least three years and permanently in many cases.

- Balanced Approach. The Governor has put forward a mix of revenue increases and spending reductions. The magnitude of the budget shortfall is too great to close on only one side of the ledger—revenues must be increased and expenditures must be decreased.

Early Action Is Critical

While the state is not required by law to take action to bring the 2008–09 budget into balance, it is critical that the Legislature close as much of the problem as possible. By taking action now, the Legislature in some cases can “double up” its savings from any enacted solutions. That is, by acting this year a program reduction can generate savings in 2008–09 which will then carry over into 2009–10. In other cases, solutions may need early action in order to get a full year’s worth of savings in 2009–10. This would often be the case in program reforms or restructurings. Similarly, early action can send signals to cities, counties, and school districts on what to expect for the upcoming budget. The extra months of planning can help these governments mitigate the adverse effects of any reductions or program changes. Actions now will also ensure that the state can continue to meet its cash flow demands. Finally, with a special election already planned for 2009, early decisions could include adding more measures to the ballot for constitutional or other changes that need to be approved by voters. In the end, any unsolved problem from 2008–09, would make next year’s budget gap even more difficult to close.

Effect of Actions on the Economy

The state’s main options for addressing its budget dilemma—cutting expenditures and/or raising revenues—would both have adverse effects on the economy. Either type of option would reduce money held by or received by individuals or businesses that otherwise could be used for consumption or investment purposes. Because the state’s economy totals more than $1.7 trillion in economic activity each year, however, spending reductions or tax increases totaling between $20 billion and $30 billion would have a relatively small impact on the overall economy. While the Legislature should try to minimize any negative economic effects of its decisions, the foremost concern must remain a permanent fix to the state’s budget ills.

Potential for Federal Assistance

In the coming months, there is a good chance that Congress will pass economic stimulus measures in an effort to boost the national economy. In the past, some components of such measures have directly provided state fiscal relief. To date, the administration has not built any estimates of such relief into its budget numbers. For the time being, this is appropriately cautious to avoid counting on relief that may never come. The state, however, should continue to press the federal government for economic stimulus measures that will provide California with flexible fiscal relief. While such relief would not solve the state’s budget problem, it could provide several billions of dollars in budgetary solutions.

Assessing the Governor’s Revenue Proposals

The most important decision facing the Legislature is the mix of solutions between spending reductions and revenue increases. As we have noted earlier, we believe the Legislature must have major contributions from both sides of the fiscal equation. The Governor is proposing roughly equal revenue and spending solutions for 2008–09, although the proportion of solutions from revenues increases in 2009–10. Below, we provide comments on the Governor’s tax proposals and offer several considerations for the Legislature as it reviews these proposals.

Duration of Increases

The Legislature will need to carefully consider the duration of any tax or revenue increases, particularly given the massive operating deficits we estimate over the forecast period. The Governor’s major proposal—the 1½ cent sales tax increase—would be in effect for three years, while all the other proposals would be ongoing. Based on our forecast, we recommend that any major revenue increases adopted be in effect for at least a three–year period.

Economic and Incidence Effects

As noted previously, almost anything the state does to close its fiscal gap will have a negative effect on the economy. The Governor’s proposed sales tax rate increase, for example, would result in an average state and local total rate of about 9.5 percent—the highest average rate in the country. This level of taxation would not only worsen the impacts on durable goods spending (particularly cars), but it would likely lead to increased internet and other “remote” purchases that could completely escape taxation. Given these factors, the Legislature should also consider a smaller sales tax increase—say, a 1 cent increase.

Alternative tax increases, however, also would have negative economic impacts. For instance, we have provided as an option (see appendix) a temporary 5 percent income tax surcharge on all personal income taxpayers. While this alternative might have somewhat less impact on consumer spending in the short term, it would have more impact on work and investment decisions. In addition, it would add to the already volatile nature of the state’s revenue structure.

The Legislature will also need to consider tax incidence issues—that is, who bears the burden of the tax—with regard to any new or increased tax revenues. The Governor relies on increases in taxes that are regressive in nature—that is, over much of the income spectrum, the proportion of taxes paid relative to income declines as income increases. Alternative methods of raising revenue—such as an income tax surcharge—raise other tax incidence issues. Some have expressed concern, for instance, over the “top heavy” nature of the personal income tax, where 1 percent of taxpayers pay over 40 percent of total liabilities. One other consideration relates to deductibility of state taxes for federal tax purposes. Increased sales tax payments generally do not affect federal liabilities, while increased state income taxes are partially offset by lower federal tax payments for many filers.

New Taxes

The Governor is proposing two new revenue sources: taxing some services and an oil severance tax.

Tax on Services. The state currently applies the sales and use tax to tangible goods, not to services. The Governor’s proposal, therefore, represents a significant departure from current policy. We believe there are good reasons to rethink the state’s approach by taxing all final transactions—whether they be tangible goods or services. Such a change, which would result in a broader–based tax with a lower average tax rate, would require a comprehensive approach and a longer–term process to sort out the many implementation issues. One option would be to have the Governor’s newly announced tax modernization commission address this proposed change as a key part of its deliberations.

Oil Severance Tax. The Legislature will also have to evaluate the proposed new severance tax on oil. California is currently the only major oil producing state that does not levy such a tax. Unlike California, however, some of those states do not levy a corporate tax and some do not levy a property tax. In addition, many severance taxes are levied on all products removed from the ground, such as natural gas and minerals. If the Legislature wants to impose such a tax, it should consider whether to apply it selectively to one industry or more broadly to all.

Broadening/Increasing Existing Taxes

Finally, the Legislature will be confronted with choices whether to broaden existing taxes and/or increase the rate on certain taxes.

Base Broadening. The Governor has not proposed any modification or elimination of tax expenditure programs. (Tax expenditures are special deductions, credits, exemptions, and exclusions that provide targeted incentives or relief to certain groups of taxpayers.) In this report’s appendix, we provide several tax expenditure options as ways to raise revenues without increasing overall tax rates.

Increased Tax Rates. In addition to the three–year increase in the state sales and use tax rate, the Governor proposes to increase the tax on alcoholic beverages by roughly a nickel a drink. We think the proposal is a reasonable one, as these per–unit charges have not been raised since 1991, and these revenues can be justified as a way for the state to recoup health care and law enforcement–related costs imposed on it as a result of alcohol abuse.

We have also offered an alternate tax rate increase as an option for the Legislature’s consideration. As described further in the next section, the Legislature could increase the vehicle license fee (VLF) rate from 0.65 percent to 1 percent and use the proceeds for a realignment of certain services from the state to local governments (similar to a 1991 realignment). There is a strong tax policy basis for increasing the rate to 1 percent, as the VLF—an in lieu property tax on cars—would then be assessed at the same base rate as other property. These taxes are also deductible for federal tax purposes, which reduces the impact of any increase for many taxpayers.

LAO Alternatives for Additional Budget Solutions

While we are supportive of the administration’s general framework for closing the budget gap, the specifics of the proposals raise a number of policy and fiscal issues. Many of the spending proposals are not new, and the Legislature has previously rejected such proposals, given concerns about the implications on program recipients. The severely worsening budget outlook warrants the Legislature giving such proposals another look. In other cases, there are better alternatives to achieve budgetary savings. While there are few avenues remaining that would achieve budgetary savings without some negative consequences, we have attempted to identify revenue increases and program reductions that would minimize harm to the state’s taxpayers and core programs.

The appendix itemizes these additional options along with their estimated fiscal effects in 2008–09 and 2009–10. We believe these options merit consideration in the special session either because of the savings they can generate in 2008–09, or because they will facilitate the state’s ability to achieve savings in 2009–10. Below, we discuss in more detail alternative approaches related to realigning program responsibilities and Proposition 98.

Program Realignments

California’s system of state–local governance diffuses responsibility to such an extent that it is often difficult to hold any one entity accountable for program results. Severe budget difficulties can offer an opportunity for the Legislature to examine the state’s structure of governance and make improvements. For instance, during the early 1990s recession, the Legislature raised revenues from the sales tax and the VLF. The increased revenues, along with General Fund costs for various social services, health, and mental health programs, were transferred to local governments. This 1991 realignment generally improved program outcomes by providing a flexible and stable revenue source for these programs.

Administration’s Funding Realignments Would Not Achieve Program Efficiencies or Innovation. The administration proposes two modest funding realignments:

- Backfilling most of the proposed General Fund reductions in local public safety funds with a shift of about $360 million in VLF revenues currently used to support DMV administrative costs. (Revenues from a proposed increase in vehicle registration fees, in turn, would backfill the loss to the department of VLF funding.)

- Dedicating the estimated $585 million in annual revenues from increasing the alcohol tax to the support of various drug and alcohol abuse prevention and treatment programs operated by the state (and currently paid for by the General Fund).

Neither of these realignments make a significant effort to improve the operations of the affected programs. Rather, they are simply tax or fee increases, with the new funds dedicated to specific purposes. Funds would be earmarked without a corresponding change in program governance or operations. As such, the administration misses an opportunity to use the new revenues as the foundation for an improvement in service delivery and program effectiveness.

Alternative Program Realignment. As noted above, raising the VLF tax rate to 1 percent has merit from a tax policy perspective. If the Legislature made it the foundation of a program realignment with local governments, programmatic outcomes could be improved as well. Under this approach, $1.6 billion of state criminal justice and mental health programs could be realigned to counties and supported by (1) the revenues raised by the increase in the VLF rate and (2) most of the VLF fee revenues currently retained for administrative purposes by the DMV. By consolidating these program responsibilities at the county level, and giving counties significant program control and an ongoing revenue stream, we think California could achieve greater program outcomes and significant budgetary savings.

Proposition 98

As has been the case over the last few years, the Proposition 98 funding requirement in 2008–09 and 2009–10 is very sensitive to year–to–year changes in General Fund revenues. Although making decisions in such a volatile revenue environment is difficult, we believe the state can take certain actions now that will help it achieve some savings while giving schools more time to respond to the magnitude of the fiscal downturn.

Make Midyear Reductions That Lower Costs Rather Than Shift Burden. Given teachers and students are in the midst of their school year—with districts already having made decisions about staff, class size, and programs—we suggest the state consider more modest midyear reductions. Compared to the administration’s $2.5 billion midyear reduction, we think districts realistically can accommodate midyear cuts of roughly $1 billion. Figure 11 shows how this $1 billion could be achieved. As shown in the figure, we think roughly one–half of the savings can come from eliminating the COLA provided in the 2008–09 Budget Act and finding one–time savings from lower–than–expected program expenditures. To achieve the remaining savings, we recommend a series of targeted changes. For K–12 education, we recommend suspending some professional development activities, some maintenance, and some instructional material purchases. For community colleges, we recommend increasing the credit fee to $26 per unit (up from $20 per unit), effective January 1, 2009, and reducing the funding for certain credit–bearing physical education courses (such as pilates, racquetball, and golf) to the regular noncredit rate. As this list suggests, we encourage the state to link reduced state funding either to reduced local costs or increased local revenue. In contrast, the administration’s approach is likely to leave some districts drawing down their local reserves to backfill midyear cuts that cannot realistically be achieved.

Figure 11

Recommend Set of Targeted Education Changesa |

(In Millions) |

|

2008‑09 |

2009‑10 |

Rescind 2008-09 COLA (0.68 percent) |

$284 |

$284 |

Foregone growthb |

— |

81 |

Savings from current/prior yearsc |

216 |

— |

K-12 program suspensions |

400 |

915 |

K-12 program eliminations |

— |

500 |

Increase California Community College (CCC) credit fee |

40 |

120 |

Reduce funding rate for certain CCC enrichment courses |

60 |

200 |

Total Reductions |

$1,000 |

$2,100 |

|

a All amounts reflect reductions from funding levels assumed at the time the 2008-09 Budget Act was adopted. |

b Assumes no growth in overall Proposition 98 funding for 2009-10. |

c Reflects one-time savings from lower-than-expected program expenditures. Assumes roughly one-half will materialize from child care programs, with the other one-half coming from K-14 programs. |

Use “Settle–Up” to Forego Even Deeper Midyear Cuts. Even after making $1 billion in midyear cuts to K–14 education, we currently estimate that Proposition 98 spending in 2008–09 would remain approximately $500 million above the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Reducing spending down to the minimum guarantee maximizes the state’s options for the coming year—enabling it to achieve budget–year savings without suspending Proposition 98 and without adversely affecting other budget priorities. Thus, we recommend scoring any current–year Proposition 98 spending that exceeds the calculated funding requirement toward prior–year Proposition 98 obligations. (This is known as settle–up. The state currently owes $1.1 billion in settle–up attributable to 2002–03 and 2003–04.) Such action not only lowers the minimum guarantee in 2009–10, it also allows the state to achieve $150 million in General Fund savings by virtue of having prepaid the scheduled 2009–10 settle–up payment. Even with scoring the settle–up in this way, the Proposition 98 base remains somewhat higher in 2008–09 under our alternative than under the administration’s plan.

Make Budget–Year Cuts Now. For 2009–10, more options are available—both for the state and school districts. Nonetheless, given the magnitude of potential cuts and the need for school districts to notify staff of impending reductions, we recommend making an initial set of budget–year reductions in the special session. As shown in Figure 11, we identify slightly more than $2 billion in potential budget–year savings. Of this amount, we identify approximately $500 million in program eliminations. We also recommend continuing from 2008–09 and further extending K–12 program suspensions. For community colleges, we recommend further increasing the credit fee to $30 per unit, effective July 1, 2009, and applying the regular noncredit funding rate to additional enrichment courses (such as ballroom dancing, drawing, and photography).

Make Targeted, Transparent Cuts. For both 2008–09 or 2009–10, we recommend preserving K–12 revenue limits and CCC apportionments, as these represent flexible dollars that support districts’ basic education program. Given these monies support basic operations, even the Governor’s plan assumes that many cuts, in reality, likely will be made elsewhere in districts’ budgets. This is why the Governor’s plan relies so heavily on flexibility provisions allowing districts to transfer categorical funds to mitigate the cut to revenue limits. Rather than take such a circuitous approach, we recommend identifying low–priority categorical programs and cutting them directly. This approach is both transparent and strategic. Under such an approach, the state would evaluate programs based on their merits and eliminate those that are poorly structured, create poor local incentives, are duplicative of other state programs, or have largely outlived their original purpose. As a result, it would make the best of difficult times by weeding out programs of lower priority.

Closing the Gap

The Legislature faces a monumental task in closing the projected $28 billion budget shortfall. The administration has put forth a credible plan that can serve as a starting point for deliberations. If the Legislature has any hope of developing a fiscally responsible 2009–10 budget, it must begin laying the groundwork now. We believe it must take major ongoing actions—reducing base spending and increasing revenues—both to close as much of the current–year gap as possible and to provide a head start on closing the 2009–10 shortfall.

Appendix |

|

|

LAO Budget Options |

(In Millions) |

|

|

|

2008-09 |

2009-10 |

Revenues |

|

|

Vehicle License Fee (VLF) Rate and Realignment—Set VLF rate at 1 percent, shift VLF administrative costs, and use funds to realign some criminal justice and mental health responsibilities from the state to counties, as discussed in the text of this report. |

— |

$1,600.0 |

Personal Income Tax Surcharge—Increase final tax liability by 5 percent for all taxpayers in 2009. Tax is deductible for federal taxes. |

$1,150.0 |

1,100.0 |

Reduce Dependent Credit—Make dependent credit the same amount ($99 per person) as the personal exemption. |

— |

1,100.0 |

Eliminate the Senior Credit—Make personal credits for seniors the same for other adults. |

— |

130.0 |

End Small Business Stock Exclusion—Eliminate the deduction for qualified sales of small business stock. |

— |

55.0 |

Repeal the Like-Kind Exchange Exclusion—Tax all like-kind exchanges, which currently allow individuals to avoid paying taxes on the sale of property. |

65.0 |

290.0 |

K-14 Education |

|

|

Proposition 98—Make various targeted reductions and increase certain fees, as described in the text of this report. |

$1000.0 |

$2,100.0 |

Proposition 98 Settle-Up—Prepay 2009-10 obligation by reclassifying some 2008-09 spending, as described in the text of this report. |

— |

150.0 |

ERAF Redevelopment Pass-Through Payments—Increase current-year amount by $50 million and make the pass-through requirement permanent. This requirement would offset part of the annual revenue loss K-14 districts experience due to redevelopment. |

50.0 |

400.0 |

Higher Education |

|

|

University of California (UC), California State University (CSU), Hastings College of the Law (Hastings)—Express intent not to fund cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) in 2009-10. |

— |

$120.0 |

UC, CSU, Hastings—Assume additional 5 percent fee increase (above 10 percent increase assumed in our baseline projection) to offset General Fund costs. (Savings are net of increased financial aid costs.) |

— |

83.0 |

UC and CSU—Increase student-faculty ratio to 20.5 on current funded enrollment base. |

$113.6 |

227.3 |

UC—Reduce specified research programs by 25 percent. |

9.3 |

9.3 |

UC and CSU—Phase out General Fund support for excess course units (credits beyond 110 percent of those required to complete a degree at UC and 120 percent at CSU). |

— |

57.9 |

California Student Aid Commission—Raise Cal Grant B eligibility requirement from 2.0 to 2.5 grade point average. |

— |

12.8 |

Health |

|

|

Medi-Cal—Adjust dental benefits to eliminate certain procedures. This option would restructure the dental benefit to eliminate some restorative procedures, but maintain access to a wide range of services, including preventative care. |

$3.4 |

$20.0 |

Medi-Cal—Include Medicare revenue in nursing home quality assurance fee calculation. The quality assurance fee that is currently charged for Medi-Cal and private pay beds would be expanded to include Medicare beds. |

— |

26.0 |

Medi-Cal—Delay implementation of Chapter 328, Statutes of 2006 (SB 437 Escutia), to self-certify income and assets of applicants. This option would delay implementation of a new program for two years. |

— |

13.0 |

Medi-Cal—Capture federal matching funds for “minor consent” beneficiaries. The state recently opted to forego federal matching funds instead of complying with new federal eligibility requirements for these beneficiaries. However, Medi-Cal can likely meet the requirements in many cases without inconvenience to these beneficiaries or disruption of services. |

1.5 |

18.9 |

Medi-Cal—Discontinue payment for over-the-counter drugs. This option would stop Medi-Cal payment for over-the-counter drugs, thereby reducing pharmacy costs. |

2.9 |

15.0 |

Medi-Cal—Suspend COLA for county administration. |

— |

24.6 |

Medi-Cal—Implement interstate match to identify and disenroll beneficiaries who have left California. |

— |

7.0 |

Medi-Cal—Reduce benefits for certain undocumented immigrants who now receive full-scope benefits with no federal matching funds. This proposal would conform benefits for this group to those of other undocumented immigrants. |

5.9 |

71.3 |

Alcohol and Drug Programs—Redirect asset forfeiture proceeds to support community substance abuse treatment. This alternative funding source could support spending for cost-effective substance abuse treatment services. |

— |

10.0 |

Developmental Services—Expand the number of services included under the Family Cost Participation Program. This option would require those with the greatest ability to pay a share of the cost for the services. |

— |

10.0 |

Medi-Cal—Retract one-half of January 2008 rate increase for family planning services. The state raised these rates by 91 percent through policy legislation (Chapter 636, Statutes of 2007 [SB 94, Kuehl]) at the same time it reduced rates for many other providers. There is no clear basis for singling out these services for an increase of that magnitude. |

1.7 |

21.6 |

Healthy Families Program—Freeze state funding at 2008-09 levels and establish a waiting list for new applicants. This approach would realize savings while keeping the program intact, and allow flexibility to adjust to new federal rules. (State Children’s Health Insurance Program will likely be reauthorized before March 2009.) |

— |

28.4 |

Social Services |

|

|

Proposition 10—Eliminate state commission and redirect 50 percent of funds to children’s health or childcare programs. This targets resources to high-priority state programs while allowing some local priorities to be supported. This option requires voter approval. |

— |

$307.4 |

Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Program (SSI/SSP)—Reduce combined SSI/SSP monthly grants to December 2008 levels. This action captures savings from January 2009 federal COLA. |

$156.0 |

479.3 |

SSI/SSP—Reduce grants for couples to 125 percent of federal poverty level. See SSI/SSP write-up in 2008-09 Analysis. |

38.9 |

119.4 |

Cash Assistance Program for Immigrants—Make some current recipients eligible for federal benefits. This proposal takes advantage of new federal funds. |

$1.1 |

$18.1 |

In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS)—Limit state support for provider wages to current state average ($10 per hour). Counties above the state average would share the marginal cost with the federal government. |

29.0 |

89.0 |

IHSS—Impose graduated caps for domestic services. See Overview of the

2008-09 May Revision. |

11.6 |

37.1 |

IHSS—Reduce state participation in share-of-cost buyouts. See Overview of the

2008-09 May Revision. |

7.4 |

23.6 |

Community Care Licensing—Increase fees for child care and community care facilities. We estimate that a 25 percent fee increase would raise cost recovery to about 50 percent of program costs. |

1.7 |

5.2 |

Kinship Guardianship Assistance Payment Program—Enable drawdown of federal funds pursuant to federal legislation. This proposal takes advantage of new federal funds. |

1.8 |

72.6 |

California Work Opportunities and Responsibilities fo Kids (CalWORKs)—Adopt community service requirement for parents who have been on aid for more than five years. See CalWORKs write-up in the 2008-09 Analysis. |

0.9 |

23.5 |

CalWORKs—Make in-person interview a condition of eligibility for adult cases. This action targets cases with a work-eligible adult who could benefit from contact and engagement. |

3.2 |

9.6 |

CalWORKs—Do not provide July 2009 COLA. |

— |

119.5 |

Welfare Automation—Delay replacement of Los Angeles County computer system by two years. The current system is functional; bid award for a new system is otherwise anticipated in early 2009. |

— |

14.6 |

Judiciary and Criminal Justice |

|

|

Judicial Branch—Suspend conservatorship program. Some courts are able to implement this program without additional funding. |

— |

$17.4 |

Judicial Branch—Make one-time reductions from 2008-09 ongoing. |

— |

103.5 |

Judicial Branch—Partially eliminate COLA provided in 2008-09. |

$35.1 |

35.1 |

Judicial Branch—Suspend State Appropriations Limit adjustment for one year. Trial courts have significant reserves to help offset this reduction. |

— |

99.9 |

Judicial Branch—Implement electronic court reporting. |

— |

12.6 |

Judicial Branch—Phase in competitive bidding for court security. |

— |

20.0 |

Judicial Branch—Transfer surplus funds from Trial Court Improvement Fund. |

61.0 |

— |

Judicial Branch—Transfer funds from State Court Facilities Construction Fund. |

— |

40.0 |

Judicial Branch—Delay appointment of additional judges. |

— |

57.1 |

Department of Justice—Charge forensic lab fees. |

— |

20.5 |

Restitution Fund—Transfer additional funds from Restitution Fund. |

30.0 |

— |

Control Section 24.10—Increase transfer to General Fund. |

— |

4.0 |

Corrections—Change so-called “wobbler” crimes to misdemeanors. Offenders diverted from prison would still be subject to criminal sanctions at the local level. |

128.0 |

261.0 |

Corrections—Requires second and third “strikes” to be serious or violent for an offender to get a full “Three Strikes” sentence enhancement. Prioritize limited prison resources for serious or violent offenders. |

10.0 |

50.0 |

Corrections—Release all non-lifer inmates 30 days early. |

$27.0 |

$53.0 |

Corrections—Exclude inmates with less than six months to serve from prison. |

14.0 |

29.0 |

Corrections—Reduce time served for parole revocations. |

48.0 |

96.0 |

Corrections—Exclude parolees with technical and misdemeanor violations from prison. Offenders could be diverted to community sanctions. |

138.0 |

262.0 |

Corrections—Implement earned discharge program for parolees. |

25.0 |

50.0 |

Corrections—Implement supervision fees for parolees. |

16.0 |

31.0 |

Resources |

|

|

Parks and Recreation—Shift funding for Empire Mine remediation to bonds. Proposition 84 funds for state park planning and administrative purposes are an eligible alternative funding source for this activity. |

$4.0 |

— |

Parks and Recreation—Shift funding for Americans With Disabilities Act lawsuit compliance to bonds. Proposition 84 bond funds for the state park system are an eligible alternative funding source for this activity. |

11.0 |

$11.0 |

Parks and Recreation—Increase state park fees. User fees in the state park system are comparatively low and many have not increased significantly over the last decade. The increased fee revenues would facilitate a reduction in the department’s General Fund spending. |

— |

25.0 |

Forestry and Fire Protection—Partially shift funding for wildland fire protection in state responsibility areas to new fees. Property owners benefitting from the service should also pay a share of state costs. The state would still bear one-half the cost of protecting wildlands from fire. |

— |

239.0 |

Various Resources Departments—Shift funding for water and regulatory programs to fees. Beneficiaries of state services should pay the state’s costs of providing these services; regulatory programs should be fully funded by regulated entities. |

6.5 |

60.2 |

Integrated Waste Management Board—Delay budgeted special fund loan repayments. Full repayment of loans from California Tire Recycling Management Fund and Integrated Waste Management Account is not statutorily required and can be delayed; repayment of loan from Recycling Market Development Revolving Loan Subaccount also can be delayed. |

26.0 |

— |

Public Utilities Commission—Delay budgeted special fund loan repayments. Repayment of $5 million on loan from California Teleconnect Fund is not statutorily required and can be delayed to a later year. |

5.0 |

— |

Transportation |

|

|

Transportation—Suspend Local Airport Grant programs. |

— |

$4.5 |

Department of Motor Vehicles—Sweep all Motor Vehicle Account revenues not subject to Article XIX. These revenues can be used for general purposes. |

$55.0 |

110.0 |

Transportation Loans—Temporarily redirect tribal payments for transportation loans to the General Fund. |

62.9 |

100.8 |

General Government |

|

|

Franchise Tax Board (FTB)—Establish Financial Institutions Records Match program that would require banks to match records of account holders to delinquent taxpayers for improved collection of unpaid tax liabilities. |

-$2.6 |

$35.4 |

FTB—Allow for suspension of occupational licenses if tax debts are not paid. |

— |

12.0 |

Office of Emergency Services (OES)—Capture related administrative costs from Governor’s proposal to eliminate public safety and victim services grants. |

2.0 |

11.5 |

OES—Eliminate California Gang Reduction Intervention and Prevention program and Internet Crimes Against Children Task Force. Program funds for the next several years could be transferred from the Restitution Fund to the General Fund. |

$30.0 |

— |

Office of Planning and Research—Eliminate Cesar Chavez Grants. |

2.5 |

$2.5 |

Various Programs—Eliminate Office of Administrative Law, Commission on the Status of Women, and the Commission for Economic Development. |

0.9 |

3.5 |

Animal Adoption Mandate—Repeal mandate and pay prior years’ costs over time. Mandate does not promote Legislature’s objectives. |

— |

25.0 |

|

Acknowledgments

The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan

office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature.

|

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as

an E-mail subscription service , are

available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925

L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page