June 2008

Back to Basics: Improving College Readiness of Community College Students

Most students who enter California Community Colleges (CCC) lack sufficient reading, writing, and mathematics skills to undertake college–level work. Thus, one of the CCC system’s core missions is to provide precollegiate “basic skills” instruction to these students. In this report, we find that a large percentage of students do not overcome their basic skills deficiencies during their time at CCC. We identify a number of state policies that we believe stand in the way of student success, and recommend several structural and systemwide changes designed to help increase preparedness and achievement among community college students.

Executive Summary

Basic Skills Education Is a Core Responsibility of Community Colleges. The California Community Colleges (CCC) provide instruction to about 2.6 million students (annual headcount) at 109 colleges operated by 72 locally governed districts throughout the state. The colleges carry out a number of educational missions, including offering academic and occupational programs at the lower–division level (freshman and sophomore), as well as recreational courses, citizenship instruction, and other services. A core mission of CCC is to provide “basic skills” instruction to students who lack college–level proficiency in reading, writing, and mathematics. (Basic skills is a term generally synonymous with remedial education.) These skills form the foundation for success in college and the workforce, yet data suggest that (1) most incoming CCC students are not ready for college–level work and (2) completion rates for underprepared students are generally low.

In 2006–07, the state launched a “basic skills initiative” that provides CCC with additional funding to address these issues. Districts are permitted to use these funds for a number of purposes, such as curriculum development, faculty training, and student tutorial services. As a condition of receiving these funds in 2007–08, colleges agreed to assess the extent to which their individual policies and practices align with evidence–based “best practices” identified by CCC researchers in a recent report.

Challenges to Improving College Readiness. Our review of CCC’s report and other studies finds a number of systemwide CCC policies and practices that are at odds with generally accepted strategies for improving basic skills education. For example:

- The CCC system does not clearly indicate to high school students how well their reading, writing, and math skills are aligned with CCC standards and expectations.

- Individual colleges often use different assessment tests and employ different definitions of college readiness, which sends a confusing message to current and prospective students.

- Many incoming CCC students do not undergo mandatory assessment. In addition, assessed students who are identified as underprepared are not required to take remedial coursework within a certain time frame.

- Community colleges fail to provide a substantial number of new students with required orientation and counseling services.

- Basic skills curricula and instructional practices are often not aligned with students’ learning styles.

LAO Recommendations. While colleges can make certain changes on their own (such as using more effective instruction techniques), we conclude that there are several structural and systemwide changes that are needed in order to improve student preparedness and success. These include:

- Assessing prospective CCC students while they are still in high school to signal their level of college readiness—and giving them an opportunity to address basic skills deficiencies before enrolling in a community college.

- Making available a statewide CCC placement test derived from K–12’s math and English standards tests.

- Creating a strong incentive for students to take required assessments, as well as requiring underprepared CCC students to begin addressing their basic skills deficiencies immediately upon enrollment.

- Giving colleges’ fiscal flexibility to provide students with the appropriate mix of classroom instruction and counseling services.

Taken together, we believe that these recommendations would help to increase the level of awareness and preparation of high school students interested in attending a community college, as well as assist the colleges to identify, place, and advise basic skills students.

Introduction

California’s community colleges provide instruction to about 2.6 million students annually. The CCC system is made up of 109 colleges operated by 72 locally governed districts, with coordination and oversight functions provided by the state–level Board of Governors (BOG). The state’s Master Plan for Higher Education, which was originally adopted in 1960, and existing statute require the community colleges to carry out a number of educational missions. For example, the system offers lower–division instruction enabling students to transfer to four–year colleges, grants two–year associate degrees, and provides precollegiate basic skills instruction as well as recreational courses. Consistent with the Master Plan, the CCC system operates on an “open access” model. That is, whereas only the top one–eighth of high school graduates are eligible for admission to the University of California (UC)—and top one–third to California State University (CSU)—all persons 18 or older who can “benefit from instruction” are eligible to attend CCC.

In the past few years, the community colleges have increased their focus on the problem of underprepared students—that is, those lacking basic reading, writing, and math skills. Most incoming CCC students are not ready for college–level work. In addition, relatively few of these students reach proficiency during their time at CCC. As discussed later, these issues have taken on a greater sense of urgency in light of the system’s recent decision to increase math and English proficiency requirements beginning in fall 2009 for students receiving an associate’s degree, as well as changes in graduation requirements for high school students.

In response to system requests, the state has invested additional resources for CCC to study and implement reforms. This report provides an overview of basic skills education and the CCC system’s new basic skills initiative. In addition, it identifies statutory and regulatory barriers to substantive improvement. Finally, we recommend ways to (1) reduce the number of underprepared high school graduates that arrive at a community college and (2) improve educational outcomes for CCC students in need of basic skills.

Background on Basic Skills

What Is Basic Skills Education?

Basic skills education refers to courses and programs designed to help underprepared CCC students succeed in college–level work. (Basic skills are typically used interchangeably with terms such as foundational skills and remedial and developmental education.) These include instruction and tutorial services in precollegiate–level reading and composition (for native English speakers as well as English learners), and mathematics (such as basic arithmetic). As the foundation upon which postsecondary studies build, basic skills education is considered one of the top priorities of the Legislature and CCC system.

Basic skills courses can be either credit or noncredit. Unlike credit courses, students taking noncredit basic skills courses do not receive grades and are typically permitted to join or leave a class at any time during the semester. (Adult education in the K–12 system is the equivalent of noncredit instruction at CCC.) Despite the name, students taking credit basic skills courses do not receive college credit. That is, units for these courses do not count toward an associate’s degree, and are not transferable to UC or CSU. However, the units are taken into account for financial aid purposes.

Workload and Demographics

The CCC system provided basic skills instruction to over 600,000 students (headcount) in 2006–07. Basic skills coursework taken by these students was the equivalent of about 115,000 full–time equivalent (FTE) students, or about 10 percent of total FTE students served by the CCC system in 2006–07. (One FTE represents a certain number of classroom hours provided to a student taking a full load of coursework during an academic year.) As discussed later, however, this percentage would be much higher if all students in need of basic skills instruction actually enrolled in such courses.

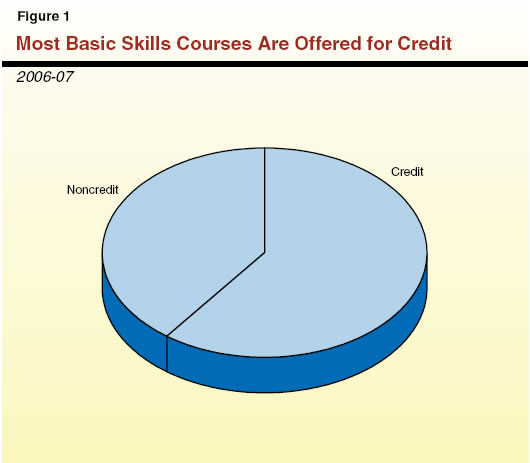

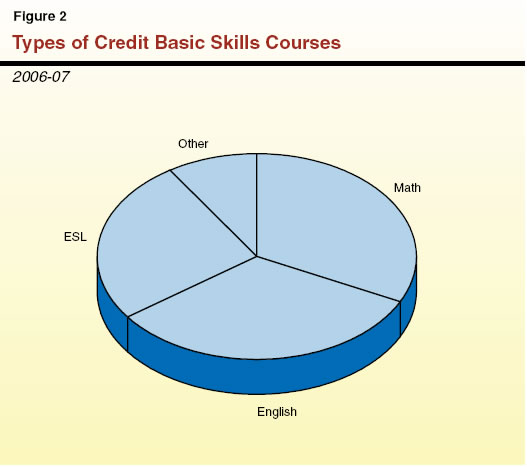

Figure 1 breaks out basic skills by credit and noncredit instruction. The figure shows that credit courses account for about 60 percent of the basic skills program. The majority of noncredit basic skills are in English–as–a–second–language (ESL) courses. Figure 2 indicates that credit basic skills is fairly equally divided among math, English, and ESL coursework.

In 2006–07, about 40 percent of basic skills students (credit and noncredit) were Latino, 20 percent were white, 20 percent were Asian, 10 percent were African–American, and the remaining 10 percent of students did not report an affiliation. There is a considerable age gap between credit and noncredit instruction. Whereas over 60 percent of credit basic skills instruction is provided to students under 25 years of age, young adults make up only about one–third of noncredit basic skills.

Completion Rates of Basic Skills Students

All three segments of the state’s public postsecondary system find that many high school graduates are not fully prepared to do college–level work. At UC, about one–third of regularly admitted freshmen (those meeting the system’s eligibility requirements) arrive unprepared for college–level writing. More than one–half of regularly admitted CSU freshmen are unprepared for college–level writing or math. According to the CCC Chancellor’s Office, about 90 percent of incoming CCC students are not proficient in transfer (university) level math or English.

Success rates for basic skills students are generally low. For example, our review of CCC data show that:

- Many Students Do Not Pass Their Basic Skills Courses. Of those students who enroll in credit basic skills courses, only about 60 percent successfully complete (receive a grade of “C” or better) a basic skills English course, while just 50 percent of students successfully complete a basic skills math course. The course completion rate for ESL is better (about 75 percent). These percentages do not take into account an unknown number of students who initially enroll in a basic skills course but drop out before the third week of classes, when an official student count (census) is taken.

- About One–Half of Basic Skills Students Do Not Persist in College. About one–half of students enrolled in credit basic skills math, English, and ESL courses in any given fall term do not return to college the following fall.

- About One–Half of “Successful” Basic Skills Students Do Not Advance. According to the Chancellor’s Office, of those students that successfully complete a credit basic skills math, English, or ESL course, only about one–half go on to complete a higher–level course in the same discipline within three years.

- Few Noncredit Students Move on to Credit Courses. The CCC system frequently states that one of the purposes of noncredit basic skills courses is to serve as a gateway to credit instruction and the attainment of a college degree. Yet, less than 10 percent of noncredit basic skills students eventually advance to and successfully complete one degree–applicable credit course (excluding physical education). (It should be noted, however, that an unknown number of noncredit students do not endeavor to achieve such a goal.)

Funding Basic Skills

Apportionments. As with college–level courses, the state provides the community colleges with funding for each FTE student served in basic skills courses. These general–purpose monies, known as apportionment funds, are provided to cover each campus’ basic operating costs. (Although they are often referred to as “unrestricted” funds, the state imposes certain restrictions on how districts spend apportionment funds, such as requiring that at least 50 percent of total funds be spent on classroom instruction.)

In 2007–08, the per–student funding rate for credit courses is $4,565. Chapter 631, Statutes of 2006 (SB 361, Scott), established an enhanced funding rate for noncredit courses that advance career development or college preparation. The 2006–07 Budget Act included $30 million in base funding toward the enhanced noncredit rate. These courses, which include all noncredit basic skills classes (such as ESL instruction), receive $3,232 per FTE student in 2007–08, while all other noncredit courses (such as home economics and educational programs for older adults) receive $2,745 per FTE student.

Matriculation Categorical. In addition to general–purpose funds, the state provides community colleges with dedicated monies for student support services, or “matriculation.” Matriculation includes programs and services for students such as assessment, orientation, and academic counseling. The 2007–08 Budget Act provides the CCC system with $102 million for matriculation. (To receive these funds, each college must provide a local match of at least 1:1.)

The Basic Skills Initiative. Since 2006–07 the state has provided additional funding to community college districts as part of the so–called basic skills initiative. The new program was created to help colleges and the Chancellor’s Office research and implement changes designed to improve basic skills education. This goal became even more important as a result of a recent regulatory change at CCC and a statutory change involving K–12. Specifically:

- In 2006, the CCC system opted to increase the minimum graduation requirements for an associate’s degree. Beginning in the fall 2009, incoming students must demonstrate competence in mathematics equivalent to intermediate algebra (rather than elementary algebra, the current requirement), as well as English composition equivalent to a transfer–level course (rather than one course below transfer level).

- Since 2006, students must pass the California High School Exit Examination (CAHSEE) in order to graduate from high school. Along with K–12, many community colleges provide additional test–related instruction and assistance to students who were not able to pass CAHSEE by the end of their senior year.

The 2006–07 Budget Act provided $63 million in one–time funds to the CCC system for basic skills. Most of these funds were allocated to community colleges in proportion to their share of statewide basic skills enrollment. Districts were permitted to use these funds for activities and services such as curriculum development, additional counseling and tutoring, and the purchase of instructional materials for basic skills classes. A portion of the funds was set aside for the Chancellor’s Office to facilitate statewide research and training on improving basic skills education in the colleges. These activities included the development of a comprehensive literature review of 26 research–based best practices in the area of basic skills education.

The 2007–08 budget package converted this one–time funding into an annual ongoing program for basic skills. Chapter 489, Statutes of 2007 (AB 194, Committee on Budget), allocated a total of $33.1 million to the CCC system. Of this amount, $31.5 million is allocated to districts on a basic skills FTE student basis (credit as well as noncredit), with a focus on students who are recent high school graduates. Chapter 489 permits the Chancellor’s Office to establish a minimum allocation of $100,000 per district.

As a condition of receiving these funds, districts must agree to conduct a self assessment on the extent to which their current practices align with the best practices identified in the aforementioned literature review, as well as submit an expenditure plan to the Chancellor’s Office on their planned use of these funds. The remaining $1.6 million is designated for faculty and staff development activities, such as regional workshops on effective instructional practices. Chapter 489 also requires the Chancellor’s Office, in consultation with the LAO and Department of Finance, to develop performance indicators for the purpose of evaluating the progress and success of the basic skills initiative. The first annual report is due to the Legislature and Governor in November 2008.

Challenges to Improving College Readiness at CCC

Research on basic skills education has grown considerably in the past several years. In general, these studies agree on a number of effective strategies for improving students’ college readiness in math and English. However, CCC policies are at odds with several of these research–based best practices. State law precludes community colleges from employing some of these strategies. In other cases, the CCC system’s own regulations or individual district practices diverge from the research. Below, we highlight some of the major discrepancies.

Early Assessment of High School Students

Research Findings. Research on higher education stresses the importance of “signaling” to high school students the extent to which their reading, writing, and math skills are aligned with college expectations. In learning whether they are on track for college–level work, students (with the assistance of their parents and high school teachers) have an opportunity to address basic skills deficiencies before entering a postsecondary institution. In so doing, students are provided with the information they need to minimize the amount of time they spend in college taking basic skills classes.

Many studies cite CSU’s early assessment program (EAP) as a national model for measuring and communicating college readiness to high school students. The EAP builds off the state’s Standards Testing and Reporting accountability program for public K–12 schools. High school juniors taking the California Standards Tests (CST) have the option of completing fifteen additional multiple–choice questions on both the math and English CST, as well as writing a separate essay. In the summer, they receive information based on their test results indicating whether they meet CSU expectations for math and English. If so, students who go on to attend CSU can enroll directly in college–level classes without taking a placement test. If they do not, students are advised to receive additional instruction in these subject areas during their senior year of high school. The EAP program also includes a professional development component in which CSU trains high school faculty on effective instructional practices for math and English.

Current CCC Policies and Practices. Currently, there is no statewide EAP for high school students considering a community college. Yet, several reports, including studies by Policy Analysis for California Education and the Stanford University Bridge Project, find that high school graduates who enroll in a community college are often unaware of CCC academic standards and the extent to which they meet such standards. Many new CCC students mistakenly assume that passing CAHSEE and receiving a high school diploma indicate that they are ready for postsecondary education. Yet, CAHSEE is not designed to test college readiness. In fact, passing it requires only 10th grade English proficiency and 9th grade math proficiency. As a result, often these students do not know they are in need of additional precollegiate coursework until they take a community college assessment test prior to registering for classes. (And as discussed below, some students fail to get assessed altogether.)

Some community colleges test students (typically seniors) while they are in high school. Yet, as the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education has shown, colleges often use different tests (including tests that are developed and used by a single campus), and use different definitions of college readiness. This sends inconsistent and confusing signals to high school students about the standards of preparedness needed to succeed in college.

Assessment of Incoming Community College Students

Research Findings. Most studies agree that incoming community college students should be assessed prior to enrolling in classes. The most commonly used assessment instruments are standardized tests. The purpose of these tests is to determine the proficiency level of students in math and English. Based on assessment results, campuses can then direct students to take coursework that is appropriate for their skill level. A number of recent studies have linked mandatory assessment with improved student outcomes such as course completion and graduation rates.

Current CCC Policies and Practices. State law authorizes the CCC system to assess both credit and noncredit students. Districts are permitted to use any assessment tool they desire, provided that they are approved by BOG. (In addition to standardized tests, colleges assess students’ level of preparation by considering other factors such as relevant coursework and grades in high school.) Regulations developed by BOG require districts to provide assessment and other matriculation services to students, though districts can establish criteria defining the circumstances under which certain students may be exempted from this requirement. (For example, a district may exempt students that wish only to take a couple of recreational classes such as golf and cooking.)

Under CCC regulations, nonexempt students are not permitted to simply “opt out” of assessment. Despite this policy, many students do. In the fall 2006, for example, the Chancellor’s Office reports that 97,000 nonexempt students in credit instruction failed to participate in assessment, which represents about 10 percent of the total number of students directed to assessment that term. Regulations prohibit districts from requiring assessment as a condition of enrollment, though they can take limited actions such as not allowing unwilling students to register for classes until the first day of the term and denying them a number of campus–provided services.

Placement of Students Into Basic Skills Courses

Research Findings. Almost all studies agree that colleges should mandate placement of students into math and English courses based on the results of their assessment. In addition, organizations such as the Lumina Foundation recommend that students take any remedial coursework as early as possible. Many studies also recommend that remedial students be discouraged from taking advanced academic or vocational courses until they have demonstrated proficiency in basic math and English skills.

Current CCC Policies and Practices. Under current law, CCC assessment results must be nonbinding. That is, statute prohibits community colleges from requiring students to take any particular class (such as a basic skills writing class) based on their assessment. Instead, “assessment instruments shall be used as an advisory tool to assist students in the selection of an educational program.” According to the CCC Academic Senate, this is a problem because over one–third of students assessed as needing basic skills courses choose not to enroll in them. Moreover, unlike UC, CSU, and a number of community colleges outside the state, California’s community colleges cannot require their students to address their basic skills deficiencies within a certain time period. Instead, these students are free to enroll in any course they choose, provided they meet any prerequisites. (As the Institute for Higher Education Leadership and Policy and others have noted, CCC regulations also make it difficult for districts to establish math and English prerequisites for college–level courses in other disciplines such as history and economics.)

Orientation and Counseling for Newly Admitted Students

Research Findings. The community college literature recommends that new students should be required to attend orientation prior to beginning their first term. Such sessions provide an opportunity for students to receive an overview of student life and campus services, as well as learn about the importance of completing remedial work as soon as possible. Researchers and practitioners also recommend that colleges provide counseling services to help new students develop an individualized educational plan and choose an appropriate set of courses.

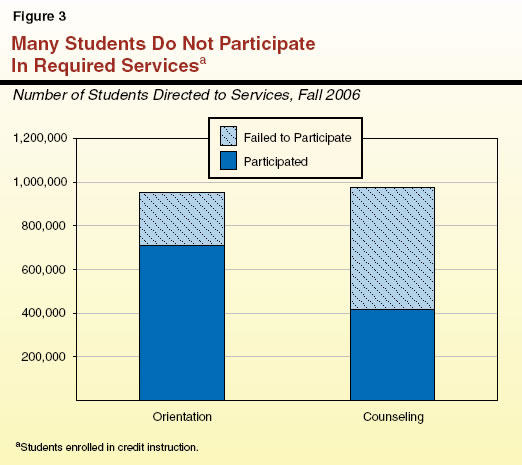

Current CCC Policies and Practices. Like assessment, state law authorizes CCC to offer orientation and counseling to students. Regulations require districts to provide these services to all students who do not meet locally determined exemption criteria. Yet, according to the Chancellor’s Office, many students directed by their college to these services do not receive them. For example, as shown in Figure 3, in fall 2006 about one–quarter of nonexempt credit students (240,000 students) failed to participate in orientation and over one–half (560,000 students) did not receive mandated counseling services. (Over three–quarters of noncredit students—about 17,000 students—did not receive required counseling.) To the extent students do not receive these services because the students refuse to participate, districts can impose the same penalties noted above for assessment.

Orientation and counseling are also constrained by a state law that requires districts to dedicate at least 50 percent of their general operating budgets to direct classroom instruction. Even though most of the personnel working in counseling and orientation programs are faculty members, these costs are not counted as instructional costs. Other noninstructional costs include administrative and clerical support, library services, financial aid advising, facilities maintenance, utilities, supplies, and various other costs in support of the community colleges’ educational mission. As a result, orientation and counseling must compete for a limited portion of a district’s funding. In some cases, this can result in counseling and advising services being funded at a level lower than what a campus would otherwise desire.

Instructional Practices

Research Findings. There is a large body of literature on effective ways to teach remedial education at two– and four–year colleges. The literature generally discourages teaching models that rely exclusively on lectures and repetitive drills involving abstract concepts. Rather, studies recommend using a variety of teaching strategies, such as encouraging interaction with and among students and emphasizing critical thinking and problem–solving skills. There is a growing literature on the benefits of contextual (applied) learning, in which students are taught math or English in a way that references “real world” situations (such as students’ life experiences or interests in a vocational field). In addition, learning communities—in which a group of students take multiple classes together for a semester—are cited by research organizations such as MDRC as a potentially effective way to promote improvement in basic skills. Though there is evidence that these instructional models can improve student outcomes, researchers caution that their effectiveness is undermined if faculty are not adequately trained and students do not receive proper support services outside the classroom (such as tutoring and academic advising).

Current CCC Practices. Based on our observations and discussions with CCC staff, it appears that California’s community colleges vary significantly as regards their use of effective instructional practices for remedial courses. In recent years, a few community colleges have developed learning–community programs that have become national models. Yet, these exemplary programs are more the exception than the rule. As an authoritative team of CCC basic skills experts noted last year, the traditional lecture–based approach to educating students is “still the prevalent model offered to the vast majority of CCC students.”

The CCC research study faults a lack of awareness among campuses as one reason why so few of them have embraced effective practices for basic skills students. It may be that the self assessment that colleges are required to complete as a condition of receiving basic skills initiative funds (discussed earlier in this report) will address this issue by familiarizing them with up–to–date research. Other colleges may be resistant to deviating from traditional instructional approaches. The largest set of concerns stem from a belief that these alternative models are more costly. The CCC study suggests, however, that these additional costs can be recouped over time.

The state has provided CCC with sufficient authority to develop and implement more effective instructional strategies. Like other best practices such as strong faculty–staff cooperation and proper sequencing of courses (also identified as best practices in the CCC system’s literature review), it is within the purview of individual districts and colleges to make the necessary pedagogical changes. However, we believe that there are a number of structural and statewide changes that are needed in order to improve student preparedness and success. We discuss our recommendations in the next section.

Recommendations

As discussed above, CCC policies and programs to improve the college readiness of students are uneven and, in many cases, inadequate. In this section, we recommend ways to improve CCC policies so as to better align college–readiness expectations of high school students with community colleges, as well as to ensure that underprepared CCC students are properly identified and guided through the remedial process. To that end, we recommend (1) expanding CSU’s EAP to high school students interested in attending a community college, (2) allowing community colleges to use CST results to help place freshmen in appropriate CCC classes, (3) requiring that underprepared students begin addressing academic deficiencies in their first term, and (4) providing campuses with additional financial flexibility to meet students’ counseling needs. Figure 4 summarizes our recommendations.

Figure 4

Summary of LAO Recommendations for

Improving College Readiness |

|

✔ Provide an indication to high school students about their readiness for college-level work at California Community Colleges (CCC) by expanding California State University’s Early Assessment Program. |

✔ Develop a CCC placement test based on K-12’s English and math California Standards Tests (CST). |

For colleges that choose to retain their current placement exam, require their acceptance of CST results and translation of CST scores into their own test results as a condition of receiving “basic skills initiative” funds. |

✔ Enact legislation that allows colleges to require underprepared students to take basic skills coursework beginning in their first term. |

✔ Allow CCC to provide more support services to students by amending the “fifty percent law,” which currently limits colleges’ fiscal flexibility to hire academic counselors. |

|

Expand EAP to the CCC System

We recommend the Legislature enact legislation to expand EAP to high school students who are considering attending a community college.

Unlike UC and CSU, community colleges require no minimum grade point average or other performance–related criteria for admission. This does not mean, however, that community colleges lack academic standards and expectations for students. In fact, as noted earlier, community colleges require that students demonstrate minimum standards of proficiency in reading, writing, and mathematics in order to graduate with an associate’s degree. In addition, students intending to transfer from a community college to UC or CSU must meet even higher math standards.

Nevertheless, a number of studies have pointed out that many high school students are unaware of the preparation needed for success in community college and the extent to which their skills and knowledge make them “college ready.” We believe that the CCC system could provide much better feedback to high school students on their preparedness for college. By sending an early message, community colleges could provide students, parents, faculty, and other staff with an opportunity to address students’ deficiencies while they are still in high school. This, in turn, could help reduce the amount of precollegiate work that students need to complete in college.

We recommend that the Legislature enact legislation to expand CSU’s EAP to high school students interested in attending a community college. We envision an expanded program that would use CST results and CSU’s supplemental test to determine whether students are on track toward preparation for CCC and CSU. (Legislation along these lines [SB 946, Scott] is currently being considered by the Legislature.) High school juniors who are thinking about attending either system would take the same test and receive information in the summer before their senior year concerning their preparation for college–level work at the two systems. Students that perform well would be exempt from taking a CCC placement exam and be permitted to enroll directly in college–level math and English. Students that need additional work could use their senior year to address their deficiencies.

Use CST Results for Placement in CCC Courses

We recommend the development of an assessment test using CST data that would help community colleges place freshmen in appropriate courses. Community colleges would be permitted to continue using their own placement test provided that they also accept CST results.

As discussed earlier, existing law allows community colleges to choose the assessments they administer to new students (subject to approval by BOG). Currently, dozens of different standardized tests are used throughout the CCC system. (In addition, many colleges recognize only their own tests and require students who were previously tested at other colleges to be reassessed.) As the National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education has found, there is significant variation among these tests both in terms of what is assessed (“test content”) and how much students are expected to know (“levels of expected proficiency”). In effect, the state’s CCC system has multiple definitions of college readiness. This sends a confusing message to current and prospective students, and results in costly duplicative testing by the colleges.

In our view, students would be better served by a statewide math and English placement test that is made available to all community colleges. Given ongoing fiscal concerns, it is particularly important that such a test be cost–effective. To that end, we recommend the development of a placement test for incoming CCC students that uses questions derived from past or current CST tests. By using CST results for placement decisions, the community colleges would:

- Be Able to Test a Range of Skill Levels. Incoming CCC students possess a wide range of knowledge and skills. By using questions from the CST test, community colleges would be able to assess the proficiency of students from elementary–school levels through high school.

- Reduce Costs for Assessment. Currently, most community colleges purchase assessment tests from commercial firms. According to a BOG–appointed task force on assessment, the tests cost an average of about $5 each time a student is tested. On the other hand, K–12 contracts with a third party to develop CST questions, to which the state owns the rights after the test is administered. To the extent that colleges use these questions for incoming CCC students, there would be reduced costs for assessment.

- Link to K–12 Standards. The CST measure whether K–12 students are meeting the state’s course performance standards. By using these tests for assessment purposes in the CCC system, the state would improve the alignment of postsecondary standards with those of K–12.

Our proposal would not require the community colleges to use CST for placement decisions (although it would be in their financial interest to do so). Instead, community colleges would retain the right to use their own commercially bought or homegrown tests. However, in order to promote consistency of standards throughout the state, we recommend that the Legislature link colleges’ receipt of future basic skills initiative funds to accepting CST results and being able to translate CST scores into their own test results. This would enable a student assessed at any community college to receive the same placement information from any other community college.

Require Students to Begin Addressing Deficiencies Upon Enrollment

We recommend the Legislature allow colleges to require underprepared students to take precollegiate coursework beginning in their first term.

Under current law, incoming students who assess into precollegiate math or English are not required to enroll in those courses. Instead, they are free to take any classes that do not carry a prerequisite (which includes most course offerings at the community colleges). As noted earlier, over one–third of assessed students fail to enroll in needed remedial work. Others delay enrollment in these courses for one or more semesters. Without building these foundational skills in math, reading, and writing, students undercut their ability to succeed in other subject areas. In addition, students who do not advance beyond basic skills math and English cannot graduate or transfer to a four–year institution (because they fail to meet minimum transfer and/or associate’s degree requirements for math and English).

In order to enhance student success and the public’s investment in the community colleges, we recommend that the Legislature amend statute to require underprepared students (who are not exempted by districts) to take appropriate remedial classes based on their assessment results. We also recommend that students be required to take such courses beginning in their first semester as a CCC student (subject to availability of these classes), and every semester thereafter until they advance to college–level proficiency. In addition, nonexempt students who refused to undergo assessment would be placed in beginning–level remedial math and English courses. This would create a strong incentive for students to participate in assessment in order to get placed in the appropriate classes.

Provide Additional Fiscal Flexibility to CCC to Enhance Support Services

In order to better serve students’ interests, we recommend the Legislature amend the “fifty percent law” to include counseling staff.

As noted in the previous section, a large number of CCC students who are directed to assessment, counseling, and orientation do not receive these services. Community colleges assert that part of the reason stems from statutory requirements that restrict how much they can spend on counselors. Specifically, as noted earlier, current law requires districts to spend at least 50 percent of their general operating budget on in–classroom instruction (the so–called fifty percent law). Most of these costs include the salaries and benefits of faculty and instructional aids. Costs for staff that provide services such as academic counseling, tutoring, and financial–aid advising are not counted (as well as operating costs such as supplies and utilities)—presumably to ensure that noninstructional functions (such as administrators’ salaries) do not squeeze out core classroom support. Yet, since most districts hover near the 50 percent threshold (the statewide average in 2006–07 was 52 percent), campuses must be careful about hiring more noninstructional staff—even when such staff provide direct services to students and (like counselors) are classified as faculty members.

As we have discussed in past Analyses, we have found no evidence that policies such as this, which set arbitrary restrictions on how colleges can allocate resources, improve student outcomes. Indeed, by limiting district flexibility to respond to local needs, they can impede the ability of community colleges to provide adequate support services that improve student performance. In order to provide colleges with the flexibility they need to provide the best mix of services for their students, we recommend amending statute to include expenditures on counseling services as part of instructional costs.

Conclusion

While the state and community colleges are investing a significant amount of time and money in basic skills education, we believe that substantial advancements can only come about if CCC changes its policies to promote a more effective delivery of services. In this report, we identified several areas of potential improvements at the community colleges, as well as statutory changes for legislative consideration. Taken together, we believe that these recommendations would help to increase the preparation levels of recent high school graduates and the ability of the community colleges to identify, place, and counsel basic skills students.

|

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by

Paul Steenhausen and reviewed by

Steve Boilard . The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan

office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as

an E-mail subscription service , are

available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925

L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page