January 17, 2008

Redefining Student Data Access Policy

Existing state and federal laws limit the ability of school districts and the California Department of Education to use student data to improve instruction. The adverse effect of these limitations will become even more pervasive once the state’s longitudinal student data system is completed in 2010. To ensure the full benefits of the new system can be achieved, we recommend the state adopt a new data access policy. The policy we recommend would expand the capacity of instructors and policy makers to use student data to improve instruction while preserving student privacy protections. It would do so at no additional cost.

Executive Summary

California is currently in the process of developing a multimillion dollar system to store long–term, student specific data. Known as the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS), the system will provide the capability for educators and policy makers to improve instruction for both individual students and the system as a whole. Specifically, CALPADS could help achieve the following four benefits:

- Target appropriate instruction for students.

- Help educators identify effective instructional approaches.

- Enable informed decision making by policy makers.

- Increase research and public awareness to improve the educational system.

Unfortunately, existing federal and state laws will not allow these benefits to be fully realized. Federal law limits disclosure of records that could lead to identification of an individual student to the entity that collected the data and only then under limited circumstances. Local educational agencies (LEAs) collect student data and, therefore, control disclosure of student records. When CALPADS is implemented, however, data will be stored centrally in a statewide repository. Nonetheless, given the constraints of federal law, the state will not be able to use or disclose data from the statewide repository. Federal law effectively makes statewide research that depends upon analysis of identifiable student records a near impossibility, even if conducted by a reputable researcher. These same restrictions on disclosure of student records also make it difficult for school districts to share data with one another—regardless of the potential benefits. State laws mimic federal laws but apply even further restrictions.

In this report, we recommend changes to state law that would allow the benefits of CALPADS to be realized while maintaining existing student privacy protections. Specifically, we recommend statutory language that would allow the California Department of Education (CDE) to, in effect, inherit disclosure rights already provided to LEAs. Thus, the new law we recommend would expand state–level opportunities for data analysis while maintaining the level of privacy prescribed by federal law. Our recommendation would not change what data may be disclosed, to whom the data may be disclosed, or the rules around protecting the data once disclosed. Our recommendations would merely affect who is allowed to disclose the data—effectively removing logistical hurdles to research and allowing the state to use the longitudinal data, to achieve the intended benefits.

We also make cost–neutral recommendations relating to staffing and implementation of the new policy. These recommendations—including the creation of a new team within CDE comprised of existing personnel—would help support the expected increase in demand for student data after CALPADS is fully implemented.

Introduction

California, like many states, is in the midst of implementing a statewide longitudinal student data system to improve the quantity and quality of data about the students served in its public Kindergarten through 12th grade (K–12) system. Collection of longitudinal student data on a statewide level can help not only individual students by ensuring their educational history follows them when they change schools, but also the educational system as a whole by enabling policy makers to analyze programs and make data–driven decisions. California, however, is in a transition phase. Laws about data access have not kept pace with technology. Most significantly, current state and federal laws pertaining to student records assume that data are only managed locally—within the LEA that collected the data. To protect student privacy while still allowing statewide data analysis, new policy needs to be adopted.

This report describes the state’s new data system and its potential benefits. It also describes federal and state laws governing the disclosure of student data and explains how these laws will not allow the state to achieve the desired benefits of its new system. The report goes on to recommend the state adopt a data access policy that would continue to protect individual student privacy while maximizing the benefits of the new longitudinal data system. We conclude with recommendations for implementation.

California on Verge of Education Information Boon

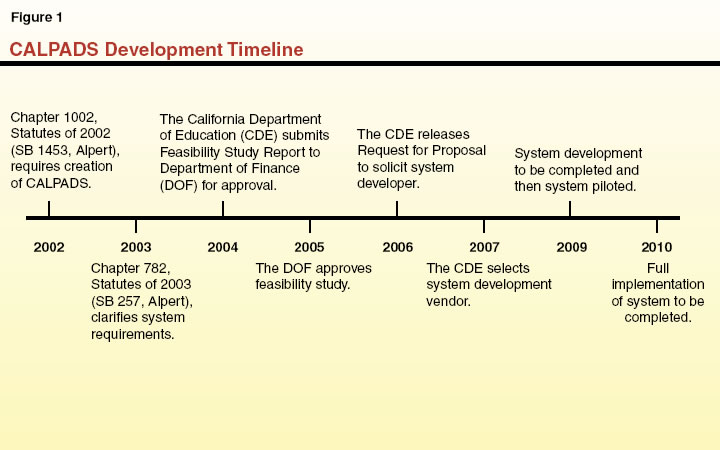

CALPADS was initiated via legislation in 2002 and is still under development. Upon full implementation, the system will maintain individual student data for all public school students in California over their K–12 academic career (that is, it will contain “longitudinal” data). Figure 1 provides a timeline of CALPADS development.

State Currently Lacks Longitudinal Data System. Currently, there is no statewide repository of individual student academic histories. The state currently collects information from LEAs in aggregate, thereby limiting the analysis that can be done with that data. For example, with aggregate data the state cannot determine the specific composition of certain student groups and cannot track the movement of students in and out of these groups. For instance, the state collects information on English Learners each year in aggregate but does not know how individual students, classified as English Learners at one point, perform from year to year. CALPADS, in contrast, will provide a common data repository into which all LEAs will provide longitudinal data for individual students. This will allow much more rigorous analysis of the effectiveness of programs designed to serve specific student groups.

CALPADS to House Variety of Student Data. The data that will be tracked in CALPADS includes elements required to comply with federal No Child Left Behind (NCLB) reporting requirements and any elements already collected from LEAs. The specific data to be stored in CALPADS includes:

- Test Scores—Including scores on Standardized Testing and Reporting (STAR) exams, the California English Language Development Test (CELDT), and the California High School Exit Exam (CAHSEE).

- Participation in Selected Programs—Including participation in the National School Lunch Program, Alternative Education, Independent Study, English Learner programs, Special Education, Advancement Via Individual Determination (AVID), drop out prevention programs, and Gifted and Talented Education (GATE).

- Courses Taken—Including completion information.

-

Demographic Data—Including gender, ethnicity, birth date, primary language, truant status, and parent education level.

The Benefits of a Longitudinal Student Database

The Legislature required the creation of the CALPADS system to meet federal reporting requirements, evaluate education programs, and improve student achievement. (See the box below for more information on the legislation creating CALPADS.) The Legislature recognized that a longitudinal student data system could be used to provide tangible and direct benefits to students, educators, and policy makers. Moreover, it recognized that the vast increase of research and analysis that could be conducted with individual longitudinal data had the potential to promote an environment of continuous improvement and provide indirect benefits to the entire K–12 education system and the public.

Specifically, a statewide longitudinal student database has the potential to provide the following four benefits:

- Target Appropriate Instruction for Students. When a student changes schools, the new school could immediately have access to the student’s academic history and use that knowledge to target appropriate services and instruction.

- Help Educators Identify Effective Instructional Approaches. Common reporting requirements and a statewide database mean that LEAs could analyze data to look for similar LEAs that have found successful approaches to a common challenge. The ability to examine data and then collaborate with other districts has the potential to save educators the time and expense of trying to “reinvent the wheel” or implementing practices shown to be ineffective elsewhere.

- Enable Informed Decision Making by Policy Makers. With longitudinal student data, analysis of program effectiveness in the aggregate and for certain student groups could be performed accurately for the first time. Currently, the state cannot accurately evaluate many programs, including programs designed for students learning English or in need of special education. Evaluation of these latter programs is especially difficult because the population of these groups are constantly changing given the classification and reclassification of students. Once CALPADS is fully operational, policy makers could use the data collected to make better programmatic and fiscal decisions. Such decisions could enhance effectiveness and efficiency—saving time and money for the system and providing better service to students.

- Increase Research and Public Awareness to Improve System. The dramatic increase in research that could be conducted with statewide longitudinal data could provide an environment for continuous improvement. Researchers could answer questions such as, “Which schools produce the strongest academic growth for students in the aggregate and subsets of students, such as English learners?” Or, “What course patterns in middle school indicate that a student is on track to succeed in rigorous courses in high school?” Currently, researchers cannot answer these questions because the data are not available. The ability to answer these types of questions would help students, educators, parents, policy makers and the entire K–12 education system.

The Legislature Envisioned Major Benefits From CALPADS

Chapter 1002, Statutes of 2002 (SB 1453, Alpert), and Chapter 782, Statutes of 2003 (SB 257, Alpert), intended the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS) be used for meeting federal reporting requirements, evaluating education programs, and improving student achievement. Specifically, these laws articulate the following goals for CALPADS:

- To ensure confidentiality and provide for data management and data sharing in a manner so as to protect individual pupil data.

- To provide access to student data for approved users (including school districts, charter schools, state education agencies, legislative policy analysts, evaluators of public school programs, and education researchers from established research organizations).

- To provide local educational agencies information that could be used to improve pupil achievement individually and in aggregate.

- To allow for accurate analyses of pupil achievement and the ability to report progress of test subgroups over time as well as allow for high quality evaluations.

- To provide the state with access to longitudinal pupil data to assess the long–term value of its educational investments and provide a research basis for improving pupil performance.

|

Existing Data Access Laws Limit Possibilities

There are a variety of federal and state laws that affect access to student records (see Figure 2 for a list). The majority of these laws were written before the creation of electronic student records and state–level longitudinal databases. Because these laws do not accommodate statewide management of data, they do not support full realization of the benefits mentioned above. Below, we review the major laws that affect access to student data. Then we explain the specific limitations of these laws that prevent full realization of the benefits of CALPADS.

Figure 2

Major Laws Affecting Access to Student Records |

Law |

Federal

or

State |

Right

Afforded To |

Education

Records Affected |

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) |

F |

Parents and

eligible students |

All education records as defined in lawa |

Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment |

F |

Parents |

Surveys containing certain questions and data as defined in the law |

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act |

F |

Parents and students who have reached the age of majority under state law |

All education records as defined in FERPA |

National School Lunch Act |

F |

Custodial parents |

Name of students and eligibility status for free meals, free milk, or reduced price meals |

Patriot Act |

F |

U.S. Attorney General or designee |

Any education records, in order to comply with a “lawfully issued subpoena or court order” |

California Education

Code 60641 |

S |

Parents and students |

All education records as defined in the law |

Individual Privacy Act California Civil Code 1798.24 |

S |

California citizens |

Any individually identifiable data held by a state agency/department including education records |

|

a All files maintained by the school including student work and tests, discipline records, health information, and instructor and parent notes. |

Federal Law

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) Is Most Significant Federal Data Access Law. The act is the primary law affecting access to student records. Virtually all pupil data (including health information, discipline records, and grades) are covered by FERPA. The only notable exception is the information pertaining to eligibility determination and status for Free and Reduced Price Meals, which is governed by the National School Lunch Act (NSLA).

FERPA Assumes Local Management of Data. The act has the two main objectives of ensuring that: (1) students (and their parents) have access to all information in a student’s official academic record and (2) unauthorized persons do not have access to the individually identifiable information in a student’s record. Under FERPA, the LEA that collected the student data is the only entity allowed to disclose that data and only then in limited situations. (For more details on FERPA rules of disclosure see the nearby box.) Currently, districts may not share individually identifiable student data with anyone outside the district, not even another district, for purposes of data analysis or collaboration. Collaboration is not an allowable reason for disclosure outside the LEA, according to FERPA. Similarly, neither state policy makers nor CDE may authorize research using disaggregated, individually identifiable student records. (CDE is allowed to disclose records that are not individually identifiable.) Only the LEA that collected the data may authorize such research. Thus, if a researcher wanted to conduct a study analyzing the high school performance of students from the 100 largest urban middle schools, the researcher would have to contact and obtain permission for use of data from each LEA individually.

Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) Disclosure Exceptions

FERPA allows local educational agencies (LEAs) to release aggregate data without restrictions, as there are no privacy issues. They may not release “individually identifiable” information to anyone except students, their parents, personnel within the district who have a “legitimate educational interest,” and the following list of specified exceptions:

- Other schools/LEAs to which a student is transferring.

- Appropriate parties in connection with financial aid to a student.

- Researchers conducting studies for, or on behalf of, the LEA.

- Specified officials conducting an audit of state or federal programs or enforcing federal legal requirements.

- Anyone specified to comply with a judicial order or lawfully issued subpoena.

- Appropriate officials in cases of health and safety emergencies.

- Anyone authorized via written parent consent.

Individually identifiable information is any information that, combined with publicly available information, allows the recipient to easily recognize an individual student’s identity. Therefore, a record need not identify a student directly, such as including a name or identification number to be individually identifiable data. Information about such characteristics as gender, age, ethnicity, special education status, or primary language, usually do not allow for identification of specific individuals. In small environments or in combination, however, this information could make a person’s identity easily traceable. Thus, each request for data needs to be analyzed on a case–by–case basis to remove individually identifiable data for that situation. |

State Law

State Laws Nearly Mirror Federal Laws. The California Education Code, for the most part, mirrors the protections in FERPA and the NSLA. California is slightly stricter than FERPA with regard to minor details and slightly more specific about roles and responsibilities. However, in general, compliance with FERPA means compliance with California state law.

California Law Extends Privacy Protections to All Statewide Individually Identifiable Records. In 2002, the California Individual Privacy Act (IPA) was passed to provide consumer protection against fraud and identity theft. One of the safeguards of the law limits who can receive individually identifiable data from a state agency or department. Currently this law does not affect access to student records in California because individually identifiable records can only be disclosed by LEAs, not a state agency or department. However, if California were to enable CDE to disclose individually identifiable data to researchers, then the IPA restriction would apply. The IPA provision requires that any release of individually identifiable data from a state department or agency to a researcher be approved by the California Health and Human Services Agency’s Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) or another independent review board (IRB) that has a signed agreement with the CPHS.

Federal and State Laws Limit Benefits of CALPADS

The Right to Disclose Is the Key to Benefit Realization. As described above, current federal and state laws assume student data is collected, stored, and managed at the local level. LEAs are authorized to disclose data under certain conditions and are responsible for ensuring federal privacy protections. Current law does not make any accommodations for data stored centrally at the state level. While the right to disclose data remains with individual LEAs, the full benefits of CALPADS will not be realized. Figure 3 illustrates this point. It lists the four potential benefits of CALPADS and our assessment of whether, under current law, they can be fully realized.

Current Laws Will Result in Inefficiencies. Figure 3 shows that only the first benefit—targeting appropriate instruction to students—can be fully realized under current law. After CALPADS implementation, LEAs will be able to get longitudinal information about an incoming transfer student. Even in these situations, however, the record transfer will not be as fast or efficient as it could be. Without a new data access policy, LEAs will still have to wait for a student’s previous LEA to forward his or her educational history upon transfer. Although the data will be stored in CALPADS, the new LEA will not be allowed to retrieve it because CALPADS is not allowed to disclose data.

Figure 3

Current Law Will Allow Partial Benefit Realization at Best |

Benefit/Objective |

Can Be Fully

Realized Under Current Law? |

Comments |

Target appropriate

instruction for students |

Yes |

May be fully realized under current law but the process could be faster and easier with a change to the data access laws to allow the transfer to be done via the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System. |

Help educators identify effective instructional approaches |

No |

Benefit will only be partially realized at best under current law. Local education agencies can do data analysis in aggregate and then call each other for specifics but no data analysis of details or for small populations will be permitted unless data access laws are changed. |

Enable informed

decision making by

policy makers |

No |

Benefit will only be partially realized at best under current law. Currently statewide research may only be conducted in aggregate, internally by the California Department of Education (CDE), or if all districts agree to provide data to the researcher. External statewide research using disaggregated identifiable records would require a change to data access laws. |

Increase research and public awareness to

improve system |

No |

Benefit will only be partially realized at best under current law. Currently statewide research may only be conducted in aggregate, internally by CDE, or if all districts agree to provide data to the researcher. External statewide research using disaggregated identifiable records would require a change to data access laws. |

Current Laws Will Allow Only Partial Benefit Realization. As Figure 3 shows, we believe the remaining CALPADS benefits can, at best, be only partially realized under current law. Limitations on disclosure rights will limit collaboration and research, and thus, the resulting benefits.

- Collaboration Discouraged. LEAs may not disclose data with one another for purposes of collaboration because, as noted earlier, this is not an allowable reason for disclosure under FERPA. This limitation will prevent educators from accessing data in another LEA to identify effective instructional approaches.

- Research Possibilities Limited. Current law does not allow CDE to disclose individually identifiable data. CDE may only release nonidentifiable data to researchers—either in aggregate or disaggregated records that have had all identifiable data removed manually. This limits the statewide data analysis that can be conducted and increases the workload for CDE. Without a change in policy regarding disclosure rights, educators and researchers can benefit from the statewide collection of longitudinal data in aggregate, but will not be able to benefit from the statewide collection of disaggregated records without intensive manual effort to remove identifiable information. This reduction in possible research means a reduction in information available to policy makers and the public to improve the system.

Data Access Limitations Currently Masked by Absence of Desired Data. Although statewide research using individually identifiable records is currently hampered by federal and state laws, the lack of desired data has minimized the impact of these legal limitations. Current laws prevent the disclosure of individually identifiable data to a researcher by anyone except the LEA that collected the data. LEAs often do not keep disaggregated or longitudinal data. Aggregate, nonlongitudinal data is less useful to researchers and thus, the requests for data from researchers have been limited. As a result, federal and state laws limiting disclosure of data have not been the most significant hurdle for researchers. Rather, the absence of desired data has been the obstacle. When CALPADS is implemented, however, the individually identifiable, longitudinal data will be available in one central location. Without a change to state law, however, researchers still will not be able to access that state data because CDE is not allowed to disclose the data. At that time, the limitations of the current laws will become a significant roadblock to statewide research and cross–district collaboration.

New Data Access Policy Needed to Achieve Benefits

The benefits of CALPADS discussed previously will only be fully achieved if the state defines a data access policy that supports these objectives. This section outlines the major components that would need to be included in such a policy and then discusses major implementation issues.

New Policy Needs Clear Objectives

The first step in articulating a new data access policy is to be clear about its general purpose. To this end, we recommend the policy contain three key intent statements. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature state its intent to:

- Comply with FERPA and protect student rights and privacy.

- Create an environment where CDE and CALPADS become resources rather than burdens to the LEAs. For example, CALPADS and CDE could reduce redundant data entry, respond to requests for data from researchers or other LEAs, transfer records electronically and in a timely fashion, provide data storage and archival services, and reduce errors in reporting.

- Promote a culture of continuous improvement via informed decision making at all levels. Accordingly, declare that student data should be as available to nonprofit researchers as possible while appropriately protecting the privacy of individuals.

Including these intent statements would help ensure the full benefits of CALPADS could be achieved. Specifically, the first intent statement is needed to assure the federal government that California will continue to comply with federal law. The second and third intent statements clarify the Legislature’s intent to expand access to statewide data analysis to legitimate educators and researchers in order to improve instruction. These intent statements form the backdrop against which more detailed policy direction, and later regulations, could be vetted during implementation.

New State Policy Should Delineate Roles and Responsibilities

We recommend that the state’s data access policy also delineate high–level guidelines for data access and use without being prescriptive on process. Specifically, as shown in Figure 4, we recommend the new policy contain four key provisions.

Figure 4

Policy Changes to Maximize Benefits of CALPADS |

Recommended Language |

Benefits Achieved |

|

Target Appropriate Instruction for

Students |

Help Educators Identify Effective

Instructional

Approaches |

Enable

Informed

Decision

Making

by Policy

Makers |

Increase

Research and Public Awareness to Improve System |

Authorize the California Department of Education (CDE) and the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS) to work on behalf of local education agencies

regarding data management |

X |

X |

X |

X |

Authorize districts to share data with each other

via CALPADS |

X |

X |

— |

— |

Authorize CDE to review requests for aggregate and individually identifiable data (via an independent review board [IRB] within CDE) using high-level guidelines defined in this statute and more detailed criteria and procedures defined

in regulations |

— |

— |

X |

X |

Authorize the CDE IRB to review requests for individually identifiable data instead of the California Health and Human Services Agency’s Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects |

— |

— |

X |

X |

Authorize State Educational Agency to Work on Behalf of LEAs. Under FERPA, CDE is currently not allowed to disclose individually identifiable data without parent consent (except for specific disclosures to the federal government for compliance purposes) because only LEAs have disclosure rights. As a result, research on statewide data and the resulting benefits of that research are severely restricted. If CDE were deemed a data management agent for LEAs, then CDE would inherit the rights afforded to them under FERPA. Thus, authorizing CDE and CALPADS to work on behalf of LEAs is the key to enabling CDE to inherit the disclosure exemptions provided by FERPA, thereby allowing CDE to authorize research. Most states that allow the state educational agency to manage statewide data disclosure have such a provision.

Authorize LEAs to Share Data Via CALPADS. Without a new data access policy, LEAs will still have to wait for a student’s previous LEA to forward his or her educational history upon transfer. Although the data will be stored in CALPADS, the new LEA will not be allowed to retrieve it. We recommend the Legislature adopt language that would allow districts to share data electronically via CALPADS. This language would not enlarge the scope of data that districts would be allowed to share. Rather it would merely facilitate the sharing of the data. Encouraging and facilitating the sharing of data between LEAs would help promote a culture of data analysis and increase the identification and sharing of best practices.

Authorize CDE to Review Requests for Student Data Using Defined Guidelines. Currently, CDE may only release nonidentifiable data to researchers—either in aggregate or disaggregated records that have had all identifiable data removed manually. This limits the statewide data analysis that can be conducted and increases the workload for CDE. We recommend the Legislature adopt language allowing CDE to give legitimate researchers access to individually identifiable data needed for research. We recommend the Legislature provide specificity on the level of openness and data access intended but could allow the details of the process to be defined by CDE. For example, we recommend all nonprofit researchers who agree to follow the data protection security measures be allowed access to individually identifiable data, and we recommend the Legislature state that explicitly in the policy. We further recommend the Legislature: (1) require CDE to create a “student data team” (SDT) that would respond to requests for data as well as conduct internal research, and (2) specify that the SDT include an IRB, which would review and respond to all requests for individually identifiable data. The SDT would be responsible for defining and implementing the details of the data request process—including the application, the process, and criteria by which the IRB would review requests, the timing of reviews, the communication flow between applicants and the IRB, the data security procedures applicants would need to agree to follow, and the appeals process. We recommend the new state policy specify that the Superintendent of Public Instruction is ultimately “authorizing” all research requests in his/her capacity as head of CDE, thereby authorizing the Superintendent to be responsible for appeals. This approach—declaring CDE responsible—is the most common approach other states have adopted to handle requests for data from researchers. This element of the new policy may have the largest benefit to the K–12 system as it would relieve the current bottleneck on research. This would expand the amount of quality research that could be conducted on statewide data and increase the ability of policy makers and the public to be informed by such research. It also would have the tangential benefits of freeing up CDE staff time for more value–added activities, such as assisting LEAs with data analysis.

Authorize CDE IRB to Release Data. As mentioned previously, California has additional individual privacy protections above and beyond the federal requirements and those of many other states. Accordingly, the policy framework recommended above would comply with FERPA but would not comply with the California IPA, unless a specific exception to that process is declared. Thus, as a final procedural step, our recommended data access policy would include a statement authorizing CDE’s IRB to replace the need for CPHS to review the release of individually identifiable student data.

It Is Not Too Soon to Begin Now

Although the final implementation of CALPADS may seem far in the future, there is much work to be done to implement a comprehensive data access policy before the system is up and data is being collected statewide. We recommend the following timeline:

- 2007–08 Legislative Session—Enact new data access policy.

- 2008–09—CDE prepares for the creation of the SDT (including posting job descriptions, conducting staff search, and defining organizational relationships). We recommend a deadline for these details approximately one month before the CALPADS pilot begin date.

- Spring/Summer 2009 (During CALPADS Pilot)—Two SDT staff prepare regulations and finalize logistics to fully implement the SDT and IRB. We recommend a deadline for these details approximately one month before the CALPADS pilot end date.

2009–10 (CALPADS Full Implemen–tation)—CDE implements full SDT team with final rollout of CALPADS.

Student Data Team Estimated at Six Full–Time Staff but No Additional Costs Expected. Based upon responses from researchers as well as data from other states, we anticipate a large increase in the volume of requests for data from researchers once CALPADS is fully operational. To respond to these requests, we anticipate CDE’s SDT will need approximately six full–time staff. We believe the staffing demand will be higher if the policy recommended in this report is not implemented and current law remains in effect. In that situation, CDE would be unable to provide individually identifiable data to researchers and would need additional staff to depersonalize all individually identifiable data from records before releasing data to researchers. The CDE must respond to these requests pursuant to the Public Records Act and, therefore, when the volume of requests increases, the need for CDE staff to respond will increase. By allowing more individually identifiable data to be released to researchers, the workload for this activity would be decreased.

Redirect Existing Staff to Capitalize on Knowledge. We recommend existing California School Information Services and CALPADS development staff who are currently scheduled to be released from their roles upon implementation of CALPADS be redirected to staff the new SDT. This approach would ensure transfer of existing knowledge about student data, CALPADS data structure, database management, and security procedures. This approach would also mean no new costs for the state, but rather an extension of existing costs for longer than originally planned. During the CALPADS pilot (currently scheduled for spring/summer 2009), we recommend transitioning the first two staff members to the SDT team so that they can write the regulations that are needed (create the application, define and document the response process, create and publish confidentiality forms, set up communication forms, establish fee schedules, etc). When CALPADS is fully implemented (currently scheduled for summer 2010), we recommend transitioning the remaining four staff members over to SDT.

Conclusion

We believe it is critical for the state to update its student data access policy. Taken together, our recommendations would allow California to maximize research opportunities and use data to help improve instruction in public schools while still safeguarding the privacy protections currently afforded in federal and state law. Moreover, our recommendations would result in no net new costs for the state, ensure knowledge transfer, and maximize the potential for informed decision making at all levels. If no changes are made to existing state law before CALPADS is fully implemented in 2010, the state should expect a large workload increase for CDE to respond to requests for nonindividually identifiable data. Furthermore, despite spending millions on the project, CALPADS will not fully realize its potential to inform decision makers at all levels and improve instruction for California’s students.

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by

Stefanie Fricano

and reviewed by

Jennifer Kuhn. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan

office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature.

|

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as

an E-mail subscription service , are

available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925

L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page