- Revenue Bonds Mainly Used. While local agencies generally have funding sources similar to the state and federal governments, they mainly use revenue bonds supported by fees paid by local water users. General obligation (GO) bonds backed by property taxes have also been used by local governments. Local agencies also are able to access state revolving loan programs mainly for water quality infrastructure (such as wastewater treatment plant improvements or to meet safe drinking water standards), as well as state–local assistance grants from statewide bond funds. In many cases, these state programs require a local match or share of cost.

- Cash Versus Revenue Bonds: Size of Project Affects Local Financing Approach. Many local entities have long–term capital plans which fund at least part of a project with cash reserve.

- When project costs go beyond cash availability, revenue bonds are generally used to make up the difference. For example: The Diamond Valley Reservoir—a $2 billion, 800,000 acre–foot reservoir developed by the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California (MWD)—was funded approximately 80 percent from revenue bonds and 20 percent in cash from MWD’s current revenues (user fee revenues and investment income).

- In contrast, a smaller project, the City of Santa Cruz Bay Street Reservoir Reconstruction Project—a $20 million, 107 acre–foot reservoir reconstruction—was fully funded by cash on a pay–as–you–go basis with 80 percent funded by water rates and 20 percent from connection fees (paid by developers for construction projects).

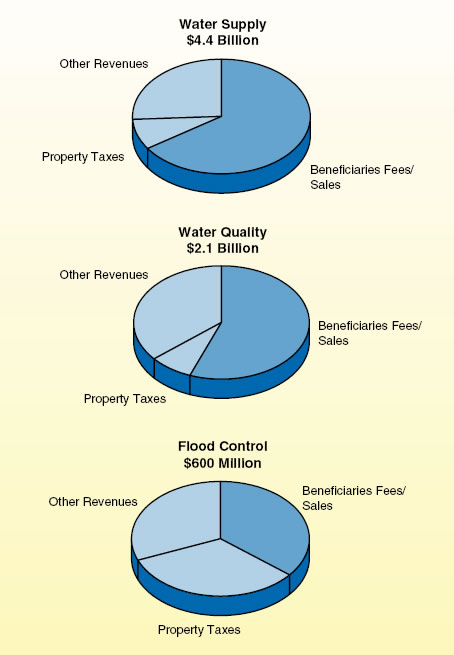

- The Role of Water Districts and User Fees. Although many cities and counties provide water services, special districts also provide these functions. Special districts provide a number of water services including water delivery, waste disposal (sanitation), and flood control. User fees—customer charges for the cost of the services they use—represent the largest source of revenues for these activities (more than 60 percent). These fees can be used to repay bonds, or for pay–as–you–go, renting, or leasing payments.

- The Use of Property Taxes. Depending largely on historical decisions, some water special districts receive an allocation of property taxes to support their operations. In order to support large capital projects, some special water districts seek voter authorization (two–thirds vote required) for local GO bonds backed by property tax levies.

- Flood Control Funding. Property taxes provide about one–third of flood control district revenues. Other major sources of revenues include development fees, benefit assessments, and intergovernmental aid.

- Other Revenues. These revenues include interest earnings, various taxes and assessments, and grants from government agencies.

Background. Proposition 218, approved by the state’s voters in 1996, restricts local governments’ authority to raise property owner fees, taxes, and assessments. The measure also permits residents to use the initiative process to repeal or reduce local fees, taxes, and assessments. The provisions of Proposition 218 affect the financing of water programs, including water supply delivery, flood control, and stormwater services, as discussed below.

Water Supply Delivery Service

Many local governments charge property owners user fees for water delivery. Prior to increasing these fees, a government must notify fee payers, hold a hearing, and reject the increase if a majority of the fee payers submit written protests. In some cases, Proposition 218 does not allow governments to charge property owners user fees. For example, government may not impose fees to finance the future expansion of a water system. To raise revenues for these purposes, government may impose taxes, assessments, or fees on developers. (We discuss Proposition 218’s requirements regarding these other revenue sources below.)

|

|

Stormwater Services

Local governments finance stormwater clean–up services from revenues raised from a variety of fees and, less frequently, through taxes. Property owner fees for stormwater services typically require approval by two–thirds of the voters, or a majority of property owners. Developer fees and fees imposed on businesses that contribute to urban runoff, in contrast, are not restricted by Proposition 218 and may be approved by a vote of the governing body. Taxes for stormwater services require approval by two–thirds of the electorate.

|

|

Flood Control Programs

Local governments sometimes impose assessments on property owners to pay for flood protection programs. Under Proposition 218, the dollar amount of each property owner’s assessment reflects the owner’s relative benefit from the program and improvements financed by the assessment. A majority of property owners must approve new assessments, with each vote weighted in proportion to the property owner’s assessment liability. Governments may only impose assessments for programs and improvements that provide a distinct benefit to land or buildings. Programs and improvements that benefit the public at large (such as a regional recreational facility) may be financed with taxes, approved by a two–thirds vote of the electorate.

|

What Drives the Cost of Water?

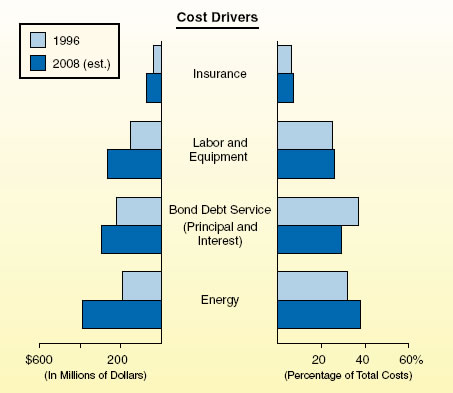

Annual State Water Project (SWP) costs have increased from $600 million in 1996 to about $1 billion in 2008. While bond–related costs for capital projects have increased by about 34 percent, the majority of the increase is for operations and maintenance of the system. Over this period, labor and equipment costs have increased $116 million—a 77 percent increase. Energy costs to run the system have more than doubled—from $192 million to $389 million.

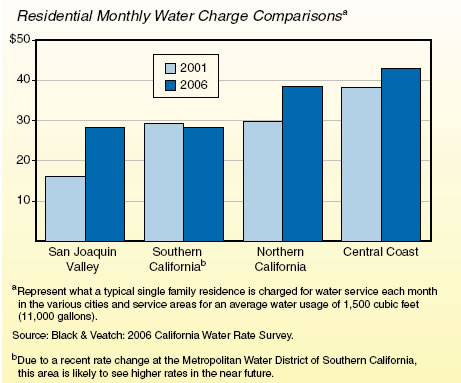

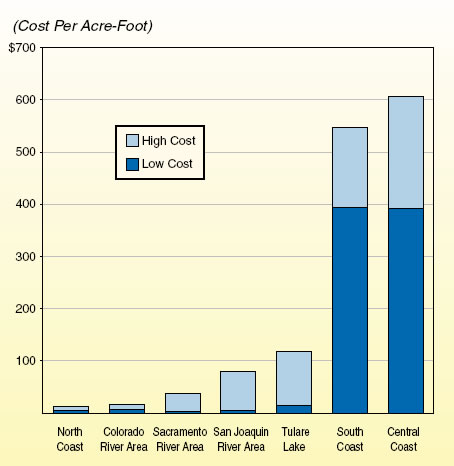

Residential water rates vary regionally, although not as much as agricultural rates (see page 62). Coastal regions (including the Central Coast) pay the highest residential water rates, mostly due to the cost of transporting and treating surface water delivered from other regions (such as from the SWP or Colorado River). In other regions, the combination of available clean groundwater and surface water reduces the consumer price by diversifying the sources of water supply in wet and dry years.

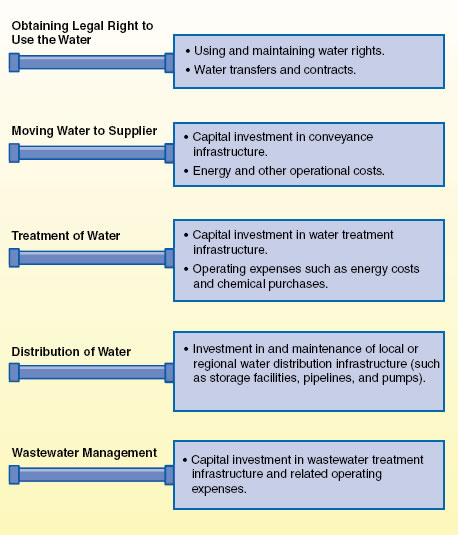

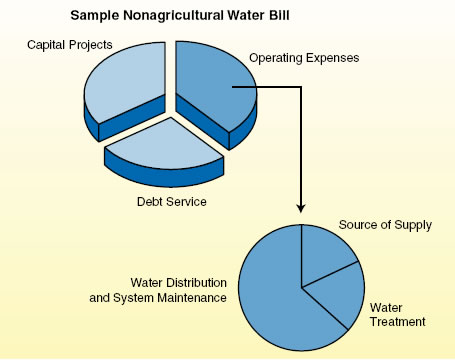

- Many factors affect the rates paid by most nonagricultural water users statewide. In a typical urban water agency, the budget is split between operating and capital/debt service expenditures. Most often, capital and debt service are as high or higher than operating expenditures given the cost of developing capital infrastructure. The relative share of these costs varies greatly among water agencies depending on the need for capital infrastructure.

- Within operating costs, most agencies have ongoing costs for purchasing water (such as from the SWP or other water rights holders), distribution costs (including energy payments, labor, and maintenance), and water treatment (including chemical purchases, labor, and facility operations).

- The cost of surface water delivered to agricultural consumers varies widely between two coastal areas and the rest of the state. In the Central Coast and South Coast hydrologic regions, most agricultural consumers are charged prices closer to residential rates, reflecting the high cost of the water delivery systems bringing water from other regions of the state (mainly the SWP). Lower prices in other regions can be attributed to a number of factors, including more abundant local surface water supplies, capital storage and delivery systems that are largely paid off, and lower–cost contracts for water.

- The cost of agricultural water, among other factors, is related to the type of crops grown. For example, the South Coast and Central Coast regions are well known for specialty crops, such as artichokes, strawberries, avocados, and citrus, which are also supported by the types of soil and climate conditions in these areas. The relatively high value of these crops helps support the relatively high cost of water required to grow them. In areas where water costs are less, row crops (such as cotton, wheat, corn, and tomatoes) are more likely to be found. This is due to a number of factors, with the abundance of low–priced water being one factor among many.

- Potential for Lower Costs in Coastal Areas. In some coastal regions, agricultural users contract with their water suppliers for lower prices in exchange for an agreement to take less water during dry seasons. In these cases, farmers would take higher reductions in water deliveries than their urban counterparts in dry years in exchange for lower rates over time.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Throughout this primer, we have shown the many dimensions of water in California, from who uses it, to its cost, to legal provisions governing its management. A few themes arise from these pages, including the complexity of the water supply system; the challenges of conveying water to those who need it, particularly through the Delta region, and to those with limited access to regional water supply; and the importance of having a reliable and sufficiently high–quality water supply to meet average demand.

In this section, we address several key water policy issues that legislators will likely face in both the short term and long term and make recommendations for legislative action. Given competing demands for funding, it is important for the state to focus on cost–effective solutions and to ensure that its water supply and water quality programs are coordinated and administered efficiently and effectively. The overarching theme of our recommendations is to improve the management of water within the state—both in terms of how currently available water is allocated among uses and the level of flexibility of water delivery systems to meet demand as conditions (such as extended dry periods) change in the future.

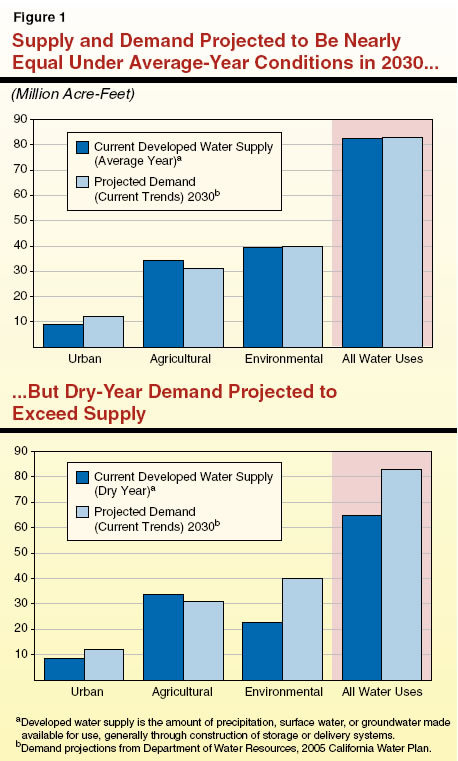

Projections show that the state is likely to have adequate water supply in the aggregate to meet its water demands in average precipitation years under current trends as seen in Figure 1. However, in dry years, projected demand by category of use will exceed supply in 2030 in most cases.

Options for Addressing Water Supply Reliability. There are several options available to the state to ensure that, during the driest years, disruptions from water shortages are minimized on a statewide basis. These options generally fall into two categories—short term and long term—depending on the length of time required to implement them. While short–term options may produce benefits sooner, they can also have long–term benefits if adopted and sustained.

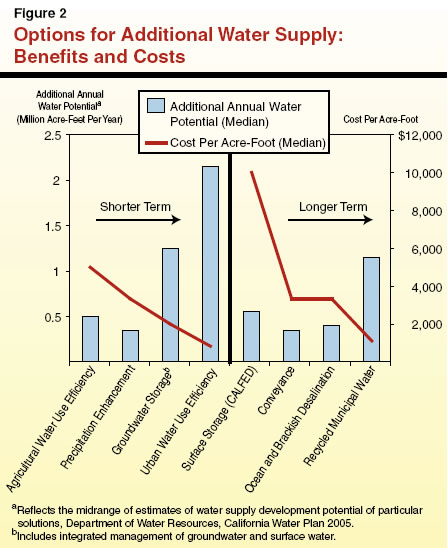

As shown in Figure 2 , the Department of Water Resources (DWR) has analyzed a number of short– and long–term options to strengthen water supply reliability throughout the state. (The surface storage–related option in Figure 2 reflects only specific CALFED Bay–Delta Program [CALFED]–proposed projects and does not include locally implemented projects.) The options presented in the figure generally involve reducing water demand or increasing water supplies. They also vary in their potential to produce additional water and in their per–unit cost to do so. For example, according to DWR estimates, urban water use efficiency (a shorter–term solution) costs about $1,000 to achieve one acre–foot of water savings per year. The DWR also determined that annually about 2 million acre–feet of additional water could result from this water management strategy. According to DWR’s estimates, this makes urban water use efficiency both the most cost–beneficial and the highest potential water producer of all of the solutions evaluated.

On the other hand, according to DWR estimates, CALFED surface storage (a longer–term solution) costs about $10,000 to achieve one acre–foot of water savings per year. This estimate is based on three specific CALFED–proposed projects: (1) Sites Reservoir, (2) Temperance Flat Reservoir, and (3) Los Vaqueros expansion. The DWR also determined that in the range of 500,000 acre–feet of additional water annually could result from this water management strategy.

In evaluating options for additional water supply, the Legislature should not only consider the cost–benefit of each but how they work together as a comprehensive package of tools. Each of the options presented in Figure 2 would contribute to needed flexibility in the management of the water system and therefore all may have a role to play.

Using the criterion of “least cost, highest gain,” short–term options (including those that would have a greater short–term impact and, if sustained, a long–term impact as well) should be directed first toward urban water use efficiency and groundwater storage, and second to agricultural water use efficiency and other options. For long–term options, investing in the long–term solution of recycled municipal water would be the first funding priority, with improvements to conveyance, desalination, and the proposed CALFED surface storage projects as secondary options.

“Reasonable Use” Requirement Should Better Reflect Scarcity of Resources. The development of California’s water rights system is steeped in tradition, and has roots in the State Constitution, but its implementation is based on outdated policy that is in need of reform. Article X of the Constitution requires that water be put to beneficial use and that waste of water or unreasonable use be prevented. At first glance, such principles seem reasonable. However, their implementation has had counter–productive results in some instances. The reasonable use requirement for surface water has generally been implemented as a “use it or lose it” policy, which itself resulted from a policy of “first in time, first in right.” Under the latter policy, the first individual to claim a water right gains the water right so long as they can demonstrate the continued use of water. The combination of these longstanding policies can lead to inefficient uses of water.

Water Rights Realignment Necessary. It is in the interest of the state to undertake a concerted effort to realign the water rights system to better reflect modern needs and circumstances. For example, this could be done by accounting for the potential for water conservation and water use efficiency in managing water rights. Thus, where water is required for agricultural purposes, the water right should mirror only the amount of water needed to grow a crop using available water efficiency technology. Similarly, urban water rights should reflect the use of cost–effective water conservation and efficiency measures. By realigning water conservation and efficiency efforts with water rights, overuse of water simply to maintain a water right could be reduced and that water would be available for other purposes within the region or state. This modernization of the water rights system could start to be accomplished by the enactment of legislation to provide an updated, comprehensive definition of the “reasonable use” of water to be used in the water rights permitting process. This definition would encompass the potential for the water rights holders to avail themselves of water conservation and water use efficiency measures discussed above.

Groundwater Important to Water Supply. The potential to use groundwater to increase water supply, by introducing water from another source into the ground as a storage basin, or encouraging the natural refilling of groundwater basins, is a significant option to address water supply needs. However, successful implementation of this solution is hampered because groundwater use is generally not regulated or monitored at the state level (in contrast to surface water). In addition, local groundwater management does not take into account statewide water needs. Finally, groundwater quality is not protected under state regulation as comprehensively as surface water quality. When contaminated, groundwater loses its potential to serve as a water supply source.

Recommend Statewide Groundwater Rights and Quality Permitting System. For the reasons stated above, we recommend that the Legislature establish a state–administered water rights system for groundwater. In addition, we recommend that the water quality permitting processes of the state and regional water boards be restructured to protect groundwater to the same extent as surface water. While moving in these directions would increase state administrative costs to establish and implement new programs, in the long term there would be cost savings to public and private entities across the state. This is because these efforts would decrease the need for costly water rights adjudications, cleanup of degraded groundwater, and treatment of groundwater for use in water supply. As with the regulation of surface water use and quality, we believe a strong case can be made for groundwater beneficiaries and polluters of groundwater to pay for the bulk of the costs of state groundwater regulatory programs.

Over $5 billion has been spent through the CALFED effort to address issues related to water flows in and through the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta (the Delta). The issues primarily revolve around the problem of balancing environmental objectives with urban and agricultural water supply requirements.

The state’s Delta–focused water system—the SWP—provides a portion of the water supply to two–thirds of Californians (mainly in Southern California, the Bay Area, and coastal cities) and irrigation water to over one–third of the state’s cropland. After years of research and study, there is generally common agreement among policy experts that the current approach to managing the Delta must change to meet the state’s water supply reliability and environmental objectives—in other words, the state needs to abandon the “business as usual” model. A culmination of this research is seen in the soon to be released Delta Vision “strategic plan” as well as the recently released Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) report evaluating various alternatives for managing the Delta. Both of these reports focus on specific proposals to change how water is conveyed through the Delta, and lay out trade–offs that will need to be made in meeting economic and environmental objectives under any of the alternatives.

At present, water exports are being reduced from the Delta to meet fish and wildlife needs, as required by federal court–order. It is unlikely that the state will be able to achieve all the water supply and environmental benefits that are currently being demanded of the Delta under current law and practice (see pages 25 and 26 for a discussion of the role of the Delta). Trade–offs will need to be made, and these will likely have negative impacts on certain segments of the state’s population, economy, and environment. The Legislature will need to evaluate the specific projects recommended in the Delta Vision and PPIC reports, as well as other reports, to determine the acceptable level of trade–offs of continued export of water from the Delta, and enact legislation that reflects the Legislature’s policy on the appropriate choice for future water conveyance and management in the Delta. Additionally, the Legislature should give particular consideration to the role that water rights and water transfers can play in strengthening water supply reliability for competing uses of water. The Legislature also needs to set clear policy for who will pay for the implementation of its Delta policy, and we recommend this be based on the application of the beneficiary pays funding principle.

Conveyance Through the Delta Must Be Addressed—and Soon. Recommendations to strengthen water supply reliability, facilitate water transfers, increase surface water storage outside of the Delta, and generally improve the efficiency and flexibility of California’s water system all hinge on addressing current problems with conveyance of water through the Delta. The Delta Vision task force as well as the PPIC have found that an alternative to the current system of conveyance is necessary if environmental and economic objectives for the Delta are to be met.

There are three basic alternatives to the current through–Delta conveyance system that have been evaluated—(1) an isolated peripheral facility such as a canal or pipeline isolated from the Delta, (2) combining through–Delta conveyance with an isolated peripheral facility (“dual–conveyance”), and (3) ending water exports from the Delta to the south. While the PPIC report recommends the Peripheral Canal as the long–term solution, the draft Delta Vision strategic plan recommends the dual–conveyance approach. To this end, we recommend that it be a priority for the state to select an alternative to the business–as–usual conveyance approach. This would be done after considering each alternative’s costs, inherent trade–offs (including environmental and land use impacts), and benefits.

Glossary

Acre–Foot—The volume of water required to cover one acre of land to a depth of one foot.

Assessment—A charge levied on property to pay for a public improvement or service that benefits that property and therefore the property owner. Assessments are usually collected on the regular property tax bill.

Beneficiary Pays Principle—According to this principle, those who benefit from the provision of a good or service should be responsible for paying its cost.

Conjunctive Use—The integrated management of surface and groundwater supplies to improve water supply reliability, such as pumping surface water into groundwater basins for storage.

Conveyance—Water transport through a pipe, canal, ditch, or natural system (such as a river or groundwater).

Dam—A physical structure designed to hold water back in a reservoir.

Desalination—The removal of salts from water to convert to fresh water.

Developed Water Supply—The amount of precipitation, surface water, or groundwater made available for use, generally through construction of storage or delivery systems.

Distribution System—A network of pipes or other means of conveyance leading to the user of water, such as pipes leading from a treatment plant to a customer’s plumbing system.

Fee—A charge imposed on an individual or business for a service, such as water right permitting or water delivery, used by that individual or business.

Groundwater—Waters beneath the land surface in underground basins (aquifers), underground streams, and underground flows of a surface stream.

Groundwater Recharge—Inflow of water to a groundwater reservoir from the surface. Precipitation moving to the water table is one form of natural recharge.

Irrigation—The controlled application of water through manmade systems to supply water requirements not satisfied by precipitation.

Levee—A natural or manmade earthen barrier along the edge of a stream, lake, or river, protecting adjacent lands from flooding.

Per Capita Water Use—The average amount of water used per person during a standard time period, generally per day.

Polluter Pays Principle—According to this principle, private individuals or businesses that use or degrade a public resource (such as air, water, or wildlife habitat) should pay for the social cost imposed by their use of the resource.

Precipitation—Rain, snow, hail, sleet, dew, and frost.

Reasonable and Beneficial Use Doctrine—A state constitutional requirement (Article X, Section 2) that all water resources must be put to beneficial use, preventing waste or unreasonable use or unreasonable method of use.

Recycled Water—Wastewater that is treated so that it can be reused before it passes back into the natural hydrologic system.

Reservoir—A pond, lake, or basin, either natural or artificial, for the management of water, such as storage.

Runoff—That part of precipitation, snow melt, or irrigation water that finds its way to surface streams, rivers, lakes, drains, sewers, or the ocean.

Subsidence—A dropping of the land surface occurring as a result of a number of factors, including as a result of large amounts of groundwater being pumped. Cracks and fissures can appear in the land.

Surface Water—Water that is on the earth’s surface, such as in a stream, river, lake, or reservoir.

Urban Water Use—Water used for commercial, industrial, or domestic household purposes, such as for business needs, drinking, food preparation, washing, and watering lawns and gardens.

Wastewater—Water that has been used in homes, industries, businesses, and agriculture that is not available for reuse unless it is treated.

Water Quality—Description of the chemical, physical, and biological characteristics of water, usually in respect to its suitability for a particular purpose.

Water Right—The legal right to use water from a particular water source, such as a stream or river.

Water Supply—Water withdrawn (for example, from streams or groundwater) that is delivered to users.

Water Use—Water that is used for a specific purpose, such as withdrawals for domestic use, irrigation, and industrial processing, and instream uses such as for hydroelectric power production and environmental–related flows.

|

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by

Catherine Freeman and reviewed by

Mark Newton . The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan

office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as

an E-mail subscription service, are

available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925

L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814. |

Return to LAO Home Page