Introduction

The state’s higher education segments offer a variety of academic programs at various campuses and centers throughout the state. In order to ensure that the segments’ offerings continue to meet the needs of the state’s citizens and employers, new programs and schools are periodically created. (See nearby box for definitions of these terms.) For example, UC has authorized at least 45 new programs and seven new schools since 2002. These expansions create significant budget implications, as they require the addition or redirection of faculty, staff, and facilities. Each higher education segment has procedures and criteria for establishing new academic programs and schools. Additionally, state law requires CPEC to review the segments’ proposals in order to ensure the proposals meet priorities and are coordinated with nearby public and private postsecondary institutions.

This report examines the process currently in place for approving and establishing new programs and schools. (A detailed examination of the process for establishing new campuses is not included because—as we describe later—it has a different scope and procedure.) By analyzing recent efforts to establish a new law school at UC Irvine and other new proposals, this report focuses on determining how well the current process addresses needs, avoids duplication, and serves state interests. We also offer recommendations on how the Legislature can improve outcomes of the review process.

Schools and Programs

A school at the University of California (UC) or the California State University (CSU) represents an academic unit that includes an academic dean and other administrators. A school could offer multiple degrees at both the undergraduate and graduate level, such as a school of engineering or school of social sciences. Alternatively, a professional school—such as a school of public policy or school of law—offers specialized graduate degrees. A handful of professional schools (such as nursing schools) may offer both undergraduate and graduate degrees. Unlike UC and CSU, community colleges are not divided into schools and only establish new program offerings.

A program is a course sequence leading to an academic degree in a particular field, such as a masters degree in environmental policy or a doctorate in music. New programs are typically created within an established department or school.

New programs and new schools typically undergo a similar approval process. Establishing a school typically requires more resources since it includes the hiring of a dean, other administrators, and founding faculty, and is also likely to enroll more students. |

The Approval Process

Each segment follows a process by which proposals for new programs or schools are studied, evaluated, and ultimately approved or denied. The process includes internal reviews by the segments themselves as well as external reviews by CPEC and accrediting agencies.

Internal Approval Process At the Segments

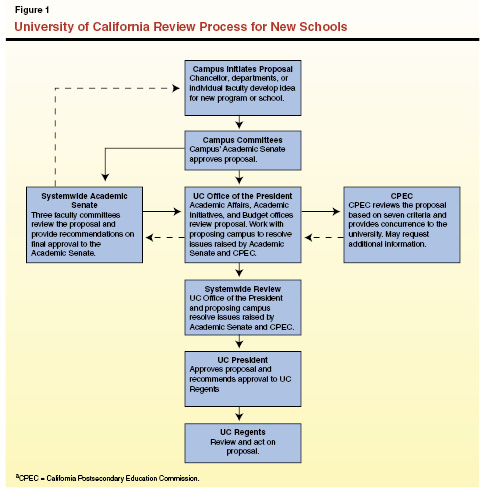

The segments initiate the program approval process with several steps at the campus and systemwide level. The segments evaluate the program proposals using similar criteria, such as: program rationale, curriculum, societal need, student demand, and total cost. Although each segment has its own formal procedures for proposing and approving new programs and schools (Figure 1 shows UC’s process for approving new schools), the processes follow similar sequences:

- Proposals Originate at the Campus Level. Most proposals originate at the campus level. Faculty, departments, or administrators develop proposals and submit them to campus committees for approval. At UC, proposals are submitted to the campus’ Academic Senate for review and approval, and at the California Community Colleges (CCC) the campus’ curriculum committee and the district’s governing board review new proposals. Somewhat different is the California State University (CSU), where campuses must first submit a preliminary program proposal to the system’s Board of Trustees. Approval by the Trustees authorizes the campus to develop a formal proposal for further campus–level review.

- Systemwide Review. After approval at the campus level, the campus submits the proposal to the systemwide office. Graduate program and school proposals at UC go through various committees of the systemwide Academic Senate—which typically includes internal and external reviews by faculty—and the provost and budget offices. Undergraduate program proposals do not undergo a systemwide approval process at UC—they only require approval at the campus level. At CSU, the Academic Program Planning Office at the Chancellor’s Office as well as external reviewers evaluate the proposals. At CCC, the Academic Affairs Division of the Chancellor’s Office reviews and approves proposals. After review, the systemwide offices forward these proposals to CPEC and accrediting agencies for review as described below.

- Approval of the Chancellor or Governing Board. At UC, the Board of Regents hears the proposals and provides final approval for new schools. The final approval for new graduate programs is delegated to the UC President. The CSU Board of Trustees and the CCC Board of Governors delegate approval authority for schools and programs to their respective systemwide chancellors.

CPEC’s Role in the Approval Process

While the segments perform their internal evaluation of proposals, they also submit the proposals to CPEC and outside accrediting agencies. The Education Code provides that one of CPEC’s responsibilities is to review proposals for new schools and programs and make recommendations regarding those proposals to the Legislature and the Governor. The CPEC can concur with the proposal, return the proposal to the segment with a request for more information or improvements, or not concur with the proposal. Unlike CPEC’s review of new campuses (see box below), its recommendation on program and school proposals is only advisory, with the exception of CSU’s proposals for joint doctoral programs with independent universities. However, all three segments historically have not allowed a campus to implement a proposal without CPEC’s concurrence.

Review for New Campuses and Off–Campus Centers

In addition to reviewing proposals for new programs and schools, the California Postsecondary Education Commission (CPEC) reviews proposals for new campuses and off–campus centers. State statute requires that CPEC review and approve new campuses before the campus receives state funding or is established. The segments are supposed to provide a letter of intent for the new campus at least five years (two years for community colleges) prior to the first expected capital outlay appropriation. The segments then develop a detailed needs study which CPEC uses to evaluate the need for the new campus based upon ten criteria.

The 1960 Master Plan for Higher Education in California (Master Plan) assigned the authority to approve new campuses to the Coordinating Council for Higher Education (changed to CPEC in 1973) in order to ensure a measure of objectivity. The Master Plan also designated general locations for future University of California and California State University (CSU) campuses so that the coordinating agency was more focused on researching the timing and order of establishing new campuses. Once the sites in the Master Plan were used, however, the planning for new campuses became more of an ad hoc process dependent upon a number of factors including segmental planning, legislative actions, and the availability of land. For example, the establishment of CSU Monterey Bay was largely the result of the federal government’s donation of land at the former Fort Ord army base. The availability of the land and some federal funds led CPEC to approve the campus even though CPEC’s needs study indicated that the campus did not adequately meet all of the ten required criteria.

An off–campus center is essentially a branch campus affiliated with a main campus that offers a limited range of courses and student services. A campus can operate an off–campus center with state funds without CPEC approval, but can only receive state funds for capital outlay if CPEC approves the center. The approval process for an off–campus center is the same as for campuses, except that the letter of intent for all segments must only be received two years prior to the first expected capital outlay appropriation. |

The CPEC has established seven criteria for evaluating new proposals, as shown in Figure 2. Due to the large number of proposals received each year, CPEC has separate agreements with each segment to exempt certain types of proposals from CPEC review. For example, CPEC reviews only doctoral programs, professional schools, and certain types of master’s programs at UC and reviews CCC proposals only if they match certain characteristics, such as being the first program of its type in the CCC system or requiring new facilities or major renovations.

Figure 2

California Postsecondary Education Commission’s Program Review Guidelines

|

|

|

|

Student demand

|

"Within reasonable limits, students should have the opportunity to enroll in programs of study in which they are interested and qualified for. Therefore, student demand for programs, indicated primarily by current and projected enrollments, is an important consideration in determining need for a new program."

|

|

Societal needs

|

"Workforce demand projections serve as one indication of the need for a proposed program. Although achieving and maintaining a perfect balance between supply and demand in any given career field is nearly impossible, it is important nevertheless that the number of persons trained in a field and the number of job openings in that field remain reasonably balanced."

|

|

Appropriateness to institutional and system mission

|

"Programs offered by a public institution within a given system must comply with the delineation of function for that system, as set forth in the California Master Plan for Higher Education."

|

|

The number of existing and proposed programs in the field

|

"An inventory of existing and proposed programs provides an initial indication of the extent to which apparent duplication or undue proliferation of programs exists. However, the number of programs alone cannot be regarded as an indication of unnecessary duplication...because (1) programs with similar titles may have varying course objectives or content, (2) there may be a demonstrated need for the program in a particular region of the state, or (3) the program might be needed for an institution to achieve academic comparability within a given system."

|

|

Total costs of the program

|

"Included in the consideration of costs are the number of new faculty required based on desired student–faculty ratios, as well as costs associated with equipment, library resources, and facilities necessary to deliver the program. For a new program, it is necessary to know the source of the funds...both initially and in the long run."

|

|

The maintenance and improvement of quality

|

"Although the primary responsibility for the quality of programs rests with the institution and its system, the Commission...considers pertinent information to verify that high standards have been established for the operation and evaluation of the program."

|

|

The advancement of knowledge

|

"The program review process encourages the growth and development of intellectual and creative scholarship. When the advancement of knowledge seems to require establishing programs...such considerations as costs, student demand, or employment opportunities may become secondary."

|

The Role of Accrediting Agencies

Another step in the approval process involves accrediting agencies, which provide another independent evaluation in addition to CPEC’s review. These agencies evaluate each new proposal to determine if it meets accreditation standards for quality. The reviews require the campus to submit information on many aspects of proposals including financial resources, societal need, and plans for evaluating educational effectiveness. There are two levels of accreditation. All of California’s public universities and community colleges receive institutional accreditation from the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC). The WASC does not accredit individual programs or schools, but requires that each institution submit new proposals for schools and programs for review as part of maintaining its institutional accreditation. Another type of accreditation is specialized or professional accreditation, which focuses on programs in specific disciplines, but does not evaluate the entire institution. For example, the American Bar Association accredits law schools while the Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education and the California Board of Registered Nursing accredit nursing programs.

The Process for Discontinuing Programs

The segments also have procedures for discontinuing programs. The formal processes for discontinuing programs is initiated at the campus level and then forwarded to the systemwide offices. Campuses, however, are more likely to informally close programs through faculty retirements and the cessation of faculty hiring and student admissions.

Measuring the Effectiveness of the Program and School Approval Process

In order to evaluate the approval procedures described above, we examined several recently approved programs and schools to determine how well they meet the state’s interests. For this evaluation, we assumed that an effective approval process should achieve the following state goals:

- Alignment With State Needs. As public institutions, UC, CSU, and CCC should align their proposals to the needs of the state’s citizens and economy. These needs could include education that addresses projected workforce shortages, promotes economic growth, or confronts societal problems. Some of these needs may differ by regions of the state.

- Focus on State Priorities. Given the limited resources of the state and its higher education segments, it is difficult to meet all of the economic and educational demands of the state. Thus, new proposals must do more than simply address some identified needs of the state—instead, new proposals should address the most critical needs. Therefore, the program and school review process should ensure that new proposals are prioritized to address the state’s most pressing needs. Such prioritization can correct for the natural desire of some institutions to seek growth and prestige through new programs that may not match state priorities.

- Cost–Effectiveness. Establishing a new program or school involves associated costs—such as the hiring of new administrators, staff, and faculty; funding for enrollment growth; and utilization of facilities. Proposals should accurately identify estimated costs and then be compared with potentially more cost–effective alternatives, such as increasing the enrollment in existing programs at another campus.

As shown in Figure 3, these goals overlap with some of the seven criteria CPEC utilizes for evaluating proposals. The major difference is that our criteria consider a project’s cost–effectiveness and rank among state priorities, recognizing that the state has more demands than it can meet with its limited resources.

Figure 3

LAO Criteria for Reviewing ProposalsCompared to CPEC Criteria

|

LAO Criteria

|

Key Considerations

|

Comparable CPEC Criteria

|

|

Alignment with state needs

|

- Is there sufficient student demand?

|

|

|

|

- Would the program address state or regional needs that are not already addressed by existing programs?

|

|

|

|

- The number of existing and proposed programs in the field.

|

| |

- The advancement of knowledge.

|

|

Focus on state priorities

|

- Is this program a critical priority for the state’s limited resources?

|

|

| |

- Are there other programs that should be implemented prior to this program?

|

|

|

Cost effectiveness

|

- What additional resources would be required?

- Is the proposed budget realistic?

- Are there more cost–effective alternatives?

|

- Total costs of the program.

|

|

|

- Is there unused capacity in existing programs?

|

|

|

|

- What steps could be taken to reduce the cost of the proposal?

|

|

UC Irvine Law School

The UC Irvine campus opened a new law school in the fall of 2009 with approximately 60 first–year students. The effort to establish the new law school helps illustrate how the state’s review process for new schools currently works. It also raises several concerns about this process—as it demonstrates how the process allowed a non–priority school to proceed.

Planning and Approvals

Figure 4 shows the key milestones in the establishment of the UC Irvine School of Law. As indicated, the campus’ plans historically included a law school. Recognizing that almost 35 years had passed since a new public law school opened in California at UC Davis, UC commissioned the RAND Corporation (RAND) in 1999 to forecast the supply and demand for lawyers in the state. The RAND’s report found that the supply of lawyers was likely to keep pace with or exceed the demand for the state as a whole and for each region in the state through at least 2015—the final year evaluated in the study. (See the box below for a more detailed description of the RAND study.)

Figure 4

Timeline for UC Irvine Law School

|

|

|

|

1964

|

The UC Irvine campus is established. Its original long–term academic plan calls for a law school.

|

|

1965

|

The UC Davis law school opens.

|

|

1999

|

The UC commissions RAND to study the need for additional lawyers in California. The study finds that the supply of lawyers will exceed demand through at least 2015.

|

|

2001

|

The UC’s systemwide Academic Senate approve plans for law schools at UC Irvine and UC Riverside. The plans do not proceed to the UC Regents due to budget concerns.

|

|

July 2006

|

The UC’s Academic Senate reaffirms its support for law schools at UC Riverside and UC Irvine. The Academic Senate states that the UC Office of the President should decide the order in which the schools are established.

|

|

July 2006

|

A special ad hoc committee appointed by UC’s Provost recommends establishing the new law school at UC Irvine before a new law school at UC Riverside.

|

|

November 2006

|

The UC Regents approve the law school at UC Irvine.

|

|

March 2007

|

The CPEC does not concur with the proposal for the law school at UC Irvine, citing the proposal’s failure to meet CPEC’s criteria in three areas: societal need, program duplication, and total cost.

|

|

May 2007

|

The UC Regents approve the position and salary for the Dean of the School of Law at UC Irvine.

|

|

July 2007

|

The UC Regents formally vote to recognize CPEC’s objections and proceed with the law school.

|

|

September 2007

|

The UC Irvine hires the founding Dean for the law school.

|

|

August 2009

|

The law school opens with approximately 60 first–year students.

|

The RAND Study

In 1999 the University of California (UC) commissioned the RAND Corporation (RAND) to study the workforce needs for lawyers in the state through 2015. The RAND study used data from a variety of sources as well as interviews with law school faculty, law firms, and other experts. The authors cautioned that supply and demand projections are open to error because many factors are difficult to predict, such as economic conditions, retirements and deaths, and changes in industry needs. The study’s projections determined that the number of lawyers is likely to keep pace with or exceed the expected growth in demand through at least 2015 for the state as a whole and for each region in the state as well. Nonetheless, the study suggested the following supply and demand issues warranted policy consideration:

- The Inland Empire and San Joaquin Valley have the lowest lawyer–to–population ratios and are having difficulty attracting lawyers.

- Significant disparities exist among the representation of California’s ethnic groups in the legal profession. Specifically, there are disproportionately more white lawyers compared with other ethnic groups.

- The state faces a potential shortage of qualified public sector lawyers as more law school graduates choose private practice.

The study mentioned that many experts did not think changes in legal education—such as a new law school—would alleviate these concerns. They believe these concerns rise from market demand rather than supply. Thus, increasing the supply of lawyers is unlikely to change the market incentives that drive these disparities. For example, the main reasons lawyers cited for not entering public practice were lower salaries and heavy workloads. And, just as in the medical profession, the Inland Empire and San Joaquin Valley have difficulty attracting lawyers because of low salaries and quality of life considerations in less metropolitan areas. |

UC Approval. While RAND was conducting its study, UC Irvine and UC Riverside moved forward with law school proposals, securing approval at the campus level and from the systemwide Academic Council in 2001. However, the UC President did not forward the proposals to the UC Regents for approval because of concerns that the system could not accommodate the associated costs at that time.

The law school proposals surfaced again in 2006 with some minor updates. The Academic Council once again approved law schools at both campuses and recommended that the UC Office of the President determine the relative timing of their establishment. The Provost appointed a committee of law experts, which in turn decided to move forward with the Irvine proposal first. The Irvine proposal was submitted to the Regents for approval at their meeting in November 2006.

At the time of the Regents’ consideration, CPEC had still not reached a decision on the UC Irvine proposal. The commission’s staff had raised several concerns with the proposal and were still awaiting a response from UC Irvine. The Regents approved the UC Irvine law school in November 2006 with the understanding that CPEC had outstanding issues with the proposal that might not be resolved.

CPEC Concerns. Additional information, however, did not alleviate CPEC’s concerns with the proposal, and CPEC did not concur with the law school proposal because it did not meet their criteria for new programs and schools. Specifically, CPEC stated that a new law school at UC Irvine:

- Was unnecessary for meeting statewide, regional, or industry workforce needs.

- Would duplicate many of the program offerings and services of existing law schools.

- Would impose additional operating and capital costs that would reduce funding available for other program areas.

The CPEC report determined that the current annual increases in law school degree production would be sufficient to meet the state’s workforce needs over the next ten years in the areas of private legal services, business, government, and public interest law. Using demand data from the Employment Development Department (EDD) and updated supply data from the RAND study, CPEC found that supply would outpace demand by more than 50,000 lawyers. Thus, supply would be sufficient to not only cover traditional legal services, but also other occupations for which a legal education is valued such as government, business, and research.

UC Response to CPEC. The UC Regents moved forward with plans for the new law school despite CPEC’s findings. The UC’s representatives argued that CPEC’s forecast underestimated the demand for lawyers in nonlegal professions and offered a number of other reasons in support of a new public law school:

- A new public law school has not opened in California since UC Davis in 1965.

- The addition of the law school at UC Irvine would offer additional opportunities to students in Southern California where there was only one public law school (UC Los Angeles [UCLA]).

- The large number of law school applicants demonstrate an unmet demand for legal education—UC annually turns away more than 80 percent of applicants.

- The UC law schools, as part of large public research universities, offer legal education that is of greater breadth and more affordable than private law schools.

- The law school will offer additional benefits to the state such as expansions in legal scholarship and research.

Although some of UC’s supporting arguments have merit, as we discuss below, they are not sufficient in our view to justify the establishment of the new school.

Establishing the New Law School

The school hired a founding Dean in September 2007 and began recruiting founding faculty. The school began accepting applications in October 2008 and opened in August 2009 with 60 first–year students, 22 faculty members, and 10 administrators. The law school expects to increase the size of its entering class to 200 students within five years for a total enrollment of 600 students.

No State Commitment. The Legislature did not appropriate any state funds specifically for the planning and startup costs of the new law school. The school planned to cover operational costs through student fee revenue, state enrollment growth funding, and private donations. The law school’s fees are $33,276 for 2009–10 and are expected to rise at least 10 percent to 15 percent for 2010–11—similar to other UC law schools. The law school expects to use private donations to provide full scholarships covering student fees for all three years for each member of the entering class in 2009–10. Based on the Legislature’s adopted methodology for marginal cost funding, the state’s cost for the law school would be less than $1 million for 2009–10, increasing to approximately $6.5 million annually at buildout with 600 students. As the 2009–10 Budget Act did not include state enrollment growth funding as originally anticipated in the law school’s financing plan and allowed UC to allocate its budget reductions internally, the state’s funding contribution to the law school in 2009–10 is unclear. The school will initially be located within existing facilities on the campus with plans for a new law school building and library within six years. Irvine officials assert that the law school will not require state funds for capital facilities as they anticipate to cover these costs with campus and donor funds. In the interim, however, the school is occupying temporary space on campus vacated by departments moving into state–funded facilities. The campus has raised $28 million in philanthropic support so far.

Law School Does Not Meet LAO Criteria For New Programs and Schools

As described earlier in this report, we believe an effective program approval process should result in programs that (1) address state needs, (2) reflect state priorities, and (3) are cost–effective. In our view, the law school at UC Irvine does not adequately meet these criteria.

The Law School Is Not Aligned With State Needs. Our review of available data shows that the state is not projected to experience a statewide shortage for lawyers. For example, both the RAND and CPEC studies demonstrated that demand for lawyers in California will not exceed supply in the foreseeable future. The UC criticized the studies for not adequately accounting for law school graduates demanded in nonlegal professions. Yet CPEC’s study reported an estimated surplus of 50,000 active California bar members that should be sufficient to support these occupations. Although projecting supply and demand accurately is difficult, we are not aware of any evidence that suggests California faces a shortage of lawyers.

The RAND study pointed out additional workforce concerns, such as potential lawyer shortages at the regional level. However, these potential shortages are not expected in Orange County. Additionally, other policy options—such as maximizing enrollment at existing law schools and offering enhanced incentives for lawyers to work in underserved regions—provide more efficient ways to address regional shortages than opening new schools.

Another potential workforce shortage could occur in particular sectors of law such as intellectual property law or environmental law. Opening a new law school to address such shortages is not necessary, however, because existing institutions should be able to adjust their curriculum to respond to changing market demand for these fields. Similarly a new law school is not an efficient way to address existing shortages in the fields of public sector and public interest law. Most law schools already offer loan forgiveness and other specialized programs to promote these sectors, yet shortages still exist due to the lower salaries and heavy workloads in these sectors. Opening a new law school with similar loan forgiveness programs would not directly address these problems. Historically, UC law schools have offered lower fees than private schools, which potentially made it easier for graduates to enter the public sector. However, with scheduled annual professional fee increases at UC of between 10 percent and 15 percent, the gap in the cost of attendance between California’s public and private law schools has narrowed in recent years.

Although the law school would be focused outside of the state’s workforce needs, UC asserts that it could contribute to the state in other ways such as economic growth and increasing law–related research. These contributions, however, do not in themselves justify the law school. Most investments in higher education contribute to economic growth and academic research—whether the investment is for additional law, undergraduate, or doctoral students. The state would be better off investing in an academic program that addresses workforce needs as it would still receive the additional benefit, regardless of the type of program, of a more educated population, economic growth, and additional research.

The Law School Is Not Among Top State Priorities. An additional criterion for new programs and schools is that they should address the state’s most critical needs. With limited resources, the state’s higher education segments cannot meet all of the economic and educational needs of the state and should focus on the highest priorities. Even if there were a demand for more lawyers, it would not necessarily justify a new law school above other higher education priorities such as undergraduate education, health sciences expansion, teaching and nursing education, outreach efforts, and maintaining affordability. Additionally, from a statewide perspective, a new law school would likely rank low among the state government’s other priority education programs such as maintaining funding for K–12 education or addressing forecasted shortages for other occupations such as nurses, physicians, and certain information technology jobs.

The Cost–Effectiveness of the New Law School Is Unclear. Assuming the law school proposal is carried out as planned, the state’s costs for the law school primarily would be the marginal cost of instruction per student. Private donations and a redirection of internal funds would cover startup costs and future capital facilities. However, we have two concerns about this funding plan. First, it is possible that nonstate funds will not materialize and UC will need to redirect other state funds to the law school. Additionally, it is not clear that a new public law school would be the most effective way to expand law enrollment, if such an expansion were warranted. For example, in planning to expand its health sciences enrollment—discussed later in this report—UC determined that it would be more cost–effective to maximize enrollment in existing schools prior to opening new schools. A similar approach might have made sense for expanding law school enrollment. The law schools at UC Davis and UC Berkeley are currently undergoing physical expansions meant to relieve overcrowding and update facilities at the schools. Further expansions to accommodate additional students at the existing law schools could have offered an alternative to opening a new law school. Existing UC law schools may argue that increasing enrollments would negatively affect the quality of instruction. However, as shown in Figure 5, many top public and private law schools currently maintain enrollments that are greater than those at the existing UC law schools.

Figure 5

Enrollment of 2007 Incoming Law School Classes at Selected Institutions

|

|

|

|

Harvard University

|

555

|

|

Georgetown University

|

450

|

|

New York University

|

448

|

|

Hastings

|

401

|

|

University of Texas

|

401

|

|

Columbia University

|

373

|

|

University of Virginia

|

361

|

|

Michigan University

|

355

|

|

UC Los Angeles

|

323

|

|

UC Berkeley

|

269

|

|

Duke University

|

207

|

|

UC Davis

|

201

|

|

University of Southern California

|

196

|

|

University of Chicago

|

190

|

|

Stanford University

|

170

|

Additionally, there are 16 private American Bar Association approved law schools in California—11 in Southern California. The state should recognize the capacity of California’s independent colleges and universities to absorb some increases in demand for law education.

Other Recently Approved Schools and Programs

The establishment of the UC Irvine School of Law raises concerns in our view because (1) CPEC did not concur with the proposal and (2) the UC Regents established the school despite CPEC’s objections. Both of these decisions are rare. The UC was unable to identify another instance in which the system had moved ahead with a proposal without CPEC’s concurrence. In addition, as we have indicated, these decisions raise questions about the effectiveness of the approval process to prevent nonpriority proposals.

Although UC Irvine’s proposal provides a good case study of the approval process, it is just one of many new programs. For example, UC has authorized approximately 45 graduate programs and 7 schools since 2002, while the CSU Trustees have approved the addition of more than 280 bachelors and masters degree programs and approximately 35 joint degree programs to campus’ academic plans during the same time period. (Not all of these CSU programs will ultimately be implemented as they must still go through the program approval process since Trustee approval is the initial step in the process.) We highlight a few of these programs below to show that some of the identified issues with the approval process are not unique to the law school and that the approval process occasionally involves more steps—including involvement from the Legislature—depending upon the proposal. We mainly focus on UC, as the university has adopted an aggressive strategy for expanding graduate enrollment that has resulted in numerous proposals for new graduate programs and schools. (See the nearby box for an overview of UC’s long–range enrollment plans.)

UC Plans Expansion of Graduate Enrollment

The Supplemental Report of the 2007–08 Budget Act required the University of California (UC) and the California State University (CSU) to provide enrollment projections through at least 2020. In its report, UC forecasted slower growth in undergraduate enrollment and a shift towards a larger proportion of graduate students. The system expects a smaller proportion of undergraduate students because demographic projections show that the size of California’s high school graduating class will stabilize and decline over the next decade. The UC plans to increase the participation rates of high school graduates and transfers so that undergraduate enrollment slightly increases despite the expected decline in the population. Most of the undergraduate growth is expected to occur at the Riverside and Merced campuses.

With undergraduate enrollment growing modestly, UC plans to focus more resources on increasing the number of graduate students. The system expects almost half of its new students by 2020–21 to be graduate students, increasing the proportion of graduate students at UC from 22 percent to 26 percent of the total student population. The UC argues this planned expansion of graduate enrollment will increase the supply of highly skilled and trained workers. It also asserts the graduate expansion responds to the increased demand for graduate degrees and seeks to bring the university’s graduate enrollment closer to that of its comparison institutions. The shift towards additional graduate enrollment is apparent in the UC Regents’ January 2009 action to reduce enrollment growth in response to the state’s budget shortfall. The adopted plan would reduce the size of the incoming freshman class by 2,500 full–time equivalent students while maintaining graduate student levels in most fields and increasing graduate student levels in nursing and medicine. |

Legislature Involved in Some Proposals

As we outlined above, the Legislature is not routinely involved in approving new programs. At times, however, programs take alternative routes to implementation when they require action by the Legislature. For example, as discussed below, the Legislature was involved in the expansion of UC’s Programs in Medical Education (PRIME) because the program required supplemental funding, and the Legislature had to take an active role in the establishment of educational doctoral programs at CSU because it required statutory changes.

Programs in Medical Education

In 2004, UC Irvine enrolled eight students in PRIME for the Latino Community (PRIME–LC). The new five–year program was designed to train physicians prepared to address the health needs of the growing Latino population. The PRIME–LC program—in which students earn a medical degree as well as a masters degree—did not undergo the program approval process because the degrees were in established departments. The program was initiated at the campus level where private grants provided funding for the program’s planning and first year of operation. However, in the 2005–06 Budget Act, the Legislature approved funds to expand and continue the program. The appropriation included a $15,000 supplement above the marginal cost funding normally provided for additional students to account for the higher cost of medical education. The Legislature provided more supplemental funding in subsequent years for the expansion of the PRIME program to other UC campuses. Additionally, the voters approved Proposition 1D, which provided $200 million for the expansion of medical educational facilities at UC, partly to accommodate the increases in enrollment associated with the PRIME program.

Educational Doctorates at CSU

Legislative approval was required for CSU to initiate its own Doctor of Education (EdD) programs since statute originally provided UC sole authority to award doctoral degrees. Chapter 269, Statutes of 2005 (SB 724, Scott), allowed CSU to offer EdD programs independently. The enacted legislation placed some limitations upon CSU’s implementation of the new programs including:

- Each program proposal must be submitted for CPEC review.

- State funding is limited to enrollment growth funding, and enrollment growth in EdD programs is not to come at the expense of undergraduate enrollment.

- Any startup funding is to come from within CSU’s existing academic support budget without diminishing the quality of CSU’s undergraduate programs.

- The CSU, the Department of Finance, and LAO are to jointly conduct an evaluation of the new programs before January 1, 2011.

As a result of the legislation, 11 campuses now operate EdD programs. Given the unallocated cuts and the lack of enrollment growth funding in recent state funding, CSU would need to redirect significant resources from other graduate programs to proceed with the new EdD programs without diminishing the resources to undergraduate education as directed by the Legislature.

Each program followed the approval process outlined earlier with reviews by the CSU Chancellor’s Office, CPEC, and WASC. The CPEC raised some concerns with the quality of the proposals in demonstrating societal need, outlining program evaluation tools, and forecasting costs, but ultimately concurred with each proposal.

Proposals Without Statewide Review

Resource constraints have necessitated that CPEC limit the number of proposals it actively reviews. As stated above, CPEC’s goal is generally to review major proposals or those with high costs. Similarly, the segments employ different review processes for specific types of proposals. For example, CSU uses a pilot program process that allows campuses to initiate small programs without systemwide review. These pilot programs can operate for five years, after which they must seek permanent approval through the standard review process or be discontinued. As for UC, it does not conduct systemwide reviews for undergraduate programs, allowing campuses complete discretion to initiate new undergraduate majors. As a result of these policies, a number of programs are initiated each year without systemwide review or CPEC review.

In most cases these are small programs without significant state costs. Two recent examples, however, demonstrate that nonreviewed proposals can result in state operating and capital outlay costs. The Governor’s 2009–10 budget proposal included two capital outlay projects which were meant to accommodate students in new programs. One proposal was a $59.4 million building for the business school at UC Irvine to provide space for expected enrollment in two new nonreviewed undergraduate majors: a Bachelor of Arts in Business Administration and a Bachelor of Science in Business Information Management. The campus estimated the two programs will increase enrollment in the business school by more than 500 full–time equivalent (FTE) students requiring an additional 32 FTE faculty. Another capital outlay proposal was a $62.6 million addition to CSU San Bernardino’s theatre arts building that would, among other goals, support new, nonreviewed master’s degree programs in music and theatre arts. The Legislature rejected both capital outlay proposals without prejudice by not including any funding for UC and CSU from lease–revenue bonds in the 2009–10 Budget Act.

Additional Proposals Approved That Do Not Satisfy LAO Criteria

The CPEC—appropriately, in our view—identified concerns with the UC Irvine law school and did not concur with the proposal. In its review of other recent proposals, however, we believe that CPEC concurred with proposals that do not meet our criteria for state priorities or cost–effectiveness. The following section describes two of these proposals.

UC Riverside School of Public Policy

The UC Riverside campus is planning to open a public policy school. The original proposal that was approved by the UC Regents and CPEC intended to open the school in the fall of 2010, but the campus decided to delay the school due to the state’s budget situation. When fully implemented, the school is expected to offer Master’s of Public Policy degrees for 120 students and doctoral degrees for 30 students. The funding sources identified in the school’s preliminary budget include state–funded enrollment growth, educational and professional school fees, and revenue from executive education programs. The school’s plan anticipates receiving state enrollment funding of just under $2 million annually once the school achieves full enrollment of 150 students. In the startup phase, however, the school expects expenses will exceed revenue by approximately $3 million, which the school plans to cover through fundraising. After initially opening in temporary space, the school would move into a new facility shared with the school of education that is projected to cost approximately $46 million.

The public policy school followed UC’s program approval process, receiving approvals from the UC Riverside Academic Senate in November 2007, the systemwide Academic Senate and UC Office of the President in May 2008, CPEC in July 2008, and the UC Regents in September 2008. Despite these approvals, our analysis of the proposal found that it does not meet our criteria for new proposals:

- Alignment With State Needs. Determining workforce needs in public policy is difficult because it includes so many fields at all levels of government, nonprofit organizations, and private firms. The proposal cites the growing enrollment in public policy programs nationwide and expected retirements in many public sector jobs as evidence of the need for a new school. However, the number of applicants to UCLA’s school of public policy was fairly constant from 2002 to 2007, when the UC Riverside school was approved. The proposal also indicated the need for a graduate public policy program in the Inland Empire region. Yet, CSU San Bernardino currently offers a graduate program in public administration, and many universities in Southern California provide graduate programs in public policy or public administration—including UCLA, the University of Southern California, Pepperdine University, and Claremont Graduate University.

- Focus on State Priorities. Opening a new public policy school at UC Riverside at the same time that undergraduate enrollment is limited, fees are increasing, and health sciences initiatives remain underfunded raises questions about UC’s priorities. It also raises questions about the state’s priorities—how do new public policy graduates compare to other state programs experiencing funding reductions to balance the state’s budget? The campus’ decision to delay the opening of the school demonstrates that it recognized some of these tradeoffs at the campus level. However, the campus’ decision to confront its priorities came after the UC Regents and CPEC approved the proposal without confronting them.

- Cost–Effectiveness. The new public policy school could lead to duplication in the region as similar programs already exist at UCLA, CSU San Bernardino, and potentially UC Irvine. The segments should explore to what extent these programs could be expanded prior to approving a new program. Additionally, unlike medical and law education, the Master Plan and statute do not provide UC sole authority to grant masters degrees in public policy. Given that the proposal is mainly meant to respond to regional needs within the Inland Empire, it could be more cost–effective and appropriate for CSU—which is typically responsible for responding to regional needs—to operate a public policy program in this region.

UC Riverside School of Medicine

The UC Riverside campus also intends to open a new medical school in the fall of the 2012 with an entering class of 50 students. At build–out, the program would accommodate 400 medical students, 160 doctoral students, and 160 residents and fellows. The UC Riverside school would be the first new public medical school in California in 40 years.

Approvals and Costs. The UC Regents approved UC Riverside’s proposal in July 2008, and CPEC concurred with the proposal in September 2008. Both agencies also adopted language that the school should not open until the resources necessary for its startup and operations are available. This contingency originated in June 2008 with the UC Academic Senate’s approval, which stated that the school should only be approved upon the commitment of new funding resources above UC’s current funding and that “if it is planned that a significant amount of funding should come from a redirection of existing resources, the school should not be approved.”

The UC estimates that the school will require $50 million in state funds prior to the school’s opening for startup activities such as recruiting a Dean and faculty, establishing residency programs, initiating accreditation, and fundraising. The UC also estimates that the school would need an additional $50 million in supplemental state funding between 2012 and 2019 as it builds up enrollment. The school estimates that by 2020–21 it would be able to cover its support costs through state enrollment funding, educational fees, contracts and grants, private gifts, and endowments. Once students are enrolled, the campus expects ongoing state enrollment funding at the respective marginal cost levels for medical students. (Medical students, residents, and doctoral students have different state marginal cost funding rates to reflect the varying costs of education for each.) The total annual state support costs for students through marginal cost funding is estimated at $26 million at full enrollment.

The school would use a distributed model of education in which the school would partner with existing hospitals and clinics rather than build a university hospital. Although the school would use a distributed model, starting the school would still have capital costs for instructional, office, and research space that would result in annual debt service costs from the state’s General Fund. In the first phase, the school would open in 2012 using existing space, newly constructed surge space built with $36 million of university funds, and approximately $12 million in renovated space built with a combination of state bond PRIME funds and university funds. The university has already authorized financing for constructing the proposed surge space and secured general obligation bonds for the renovated space in the 2009–10 Budget Act. Additionally, the school has sought funding for facilities from the federal government and private foundations. The second phase would consist of $508 million for instruction and research facilities that would begin construction in 2011 for completion in 2015. The proposal expects most of the cost of phase two to be covered with state bond funds. Currently, however, state bond funds for UC projects are depleted.

The UC Regents’ state budget request for 2009–10 included $10 million of the estimated $50 million necessary in supplemental funding to continue with the school’s planning. The enacted 2009–10 Budget Act, however, does not provide supplemental funding for planning. The UC has not indicated whether the school’s opening would be delayed. Up to this point, the school has used internal resources and fundraising to support the proposal’s preparation and subsequent planning, which have included appointing an interim Vice Chancellor and hiring a founding Dean.

Planning. The medical school would be part of a systemwide plan to increase enrollment in UC’s health sciences departments. Based upon the findings of various committees, UC outlined the need for the expansion of health sciences and a new medical school in a 2007 publication entitled A Compelling Case for Growth. The document described California’s growing workforce needs in the health professions and UC’s systemwide plan for expanding enrollment in medicine, nursing, public health, pharmacy, and veterinary science. According to UC’s publication and other studies, California has fewer opportunities for medical students than other states and is likely to experience a shortage of doctors in specific regions and specialties. The growth plan described in UC’s document indicated that it would be more cost–effective to expand medical student enrollments at existing schools through a continuation of PRIME and other initiatives prior to opening a new medical school. Once growth was maximized at existing schools, the publication suggested opening at least one new medical school by 2020. Two campuses—UC Riverside and UC Merced—put together proposals for a new medical school, with UC Riverside receiving formal approval.

The UC study and other estimates both support the view that educating more doctors is aligned with the state’s workforce and healthcare demands. And, given the Legislature’s recent funding for additional PRIME and nursing students, expanding funding in the health sciences reflects state priorities. Despite the approval of the UC Regents and CPEC, however, we believe the proposal still does not adequately meet our criterion of cost–effectiveness.

Cost–Effectiveness. There are a number of alternatives to this proposal that we think should have been considered prior to its approval. These alternatives, summarized below, represent policy options that could achieve the identified goals of the proposed medical school with potentially lower costs.

- Maximize Enrollment at Existing Medical Schools. The UC’s 2007 report stated that it would be more cost–effective to maximize enrollment at existing medical schools prior to opening a new school. The report identified an additional capacity of 775 FTE students at UC’s existing medical schools. However, the only enrollment growth initiative at existing medical schools is the PRIME program, which plans to add 276 additional FTE students. Once PRIME programs are fully enrolled, existing schools would have additional capacity for approximately 500 medical students—more students than would eventually be enrolled at UC Riverside’s medical school. Adding these students to existing schools would require some additional investment in capital facilities, but would still cost substantially less than constructing and operating a new medical school in Riverside. As originally outlined in UC’s health sciences initiative, a new medical school should only open after capacity in existing programs is fulfilled.

- Implement the Distributed Model at Existing Medical Schools. An additional alternative for meeting the state’s interests at a lower cost would be for existing medical schools to operate programs in underserved regions rather than opening new medical schools in these areas. For example, UCLA currently operates such a program with Charles Drew University (CDU) in south Los Angeles in which students undertake the basic science curriculum at UCLA during the first two years of medical school and complete their third and fourth years with clinical rotations at CDU and its affiliate hospitals. The medical school at UC San Francisco (UCSF) offers a similar program in Fresno which provides clinical rotations at sites around Fresno for third and fourth year medical students from UCSF and other schools. The UCSF program also offers residency programs at hospitals in the Fresno region. Such models have also been used in other states. Medical schools within the University of Texas, Michigan State University, and Florida State University have adopted distributed models in which medical students complete their first two years of medical education at a main campus and are then distributed to community–based program sites in regions throughout the state for their third and fourth years of training. These models would consolidate the costlier basic science curriculum and research at existing institutions while still allowing students and residents to develop connections in underserved communities—hopefully motivating them to stay in the region.

- Reduce Research Capacity at the New Medical School. An additional option for reducing the medical school’s costs that was not included in UC Riverside’s proposal would be to limit the research mission of the new medical school. A large portion of UC Riverside’s costs would result from the additional facilities and faculty needed to support research activities. However, the state’s primary need—and the primary rationale for the new medical school—is to increase the supply of physicians in an underserved region of the state. Consequently, the school could primarily focus on medical instruction and clinical training for students and residents, and limit the resources and faculty time devoted to research. California already has five comprehensive UC medical schools as well as private medical schools that provide medical instruction, residency training, research, and clinical services. These schools would continue to support and advance medical research in California, while UC Riverside could focus on the education of doctors without duplicating or diluting the research programs at existing schools.

Proposals With Substantial Nonstate Support

Another important characteristic of many proposals is the amount of nonstate support campuses receive for planning and implementation prior to approval at the systemwide or state level. As already described, PRIME, the UC Irvine law school, and the UC Riverside medical school were able to begin planning, hire full–time staff, and even enroll students without state support by using nonstate support for the proposals. Another example that shows the unique role of nonstate financing in new proposals is the proposed school of nursing at UC Davis.

The UC Davis campus is proposing to open a new school of nursing with masters and doctoral programs in the fall of 2010 and an undergraduate program in the fall of 2011. The school anticipates enrolling about 450 students at full enrollment. This growth is aligned with UC’s 2007 plan for growth in the health sciences which advocated substantial increases in nursing students through existing and new programs. Increasing the supply of nurses has been a state priority for a number of years—starting in 2006–07, the Legislature appropriated supplemental funding to all three segments to increase nursing enrollment. Similar to funding for PRIME and other nursing programs, the school’s plans expect for the Legislature to provide per–student funding above the normal marginal cost level to account for the higher cost of educating nursing students at the masters and doctoral level. The state’s annual contribution from enrollment is expected to be approximately $13.5 million (54 percent of the school’s total revenues) when the school reaches full enrollment.

In late 2006, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation approached UC Davis with an interest in improving health–care delivery systems. The foundation ultimately agreed to commit $100 million over 11 years for UC Davis to establish a nursing school. The terms of the grant were for an initial release of funds followed by the remaining funds over an 11–year time frame, contingent upon the school achieving specific milestones, including approval of the school by the UC Regents and receipt of state funding for enrollment growth. Prior to receiving approval from CPEC in February 2009 and the UC Regents in March 2009, UC Davis had received approximately $21 million of the grant funds. These funds allowed the campus to retain 9.75 FTE staff members dedicated to the school of nursing, as well as six other UC Davis staff members who regularly contributed to the planning process. The school also appointed an Associate Vice Chancellor for Nursing in June 2008 who will serve as the Dean of the new school. These funds, therefore, allowed the campus to conduct considerable planning, hire staff, and initiate additional fundraising efforts for the school before it was approved. The availability of nonstate funds will also allow the school to recruit and fund faculty in advance of state funding.

Over the next 11 years, the school expects to use the remaining grant to fund competitive faculty salaries and student support services and to finance leased facilities as necessary to accommodate future enrollment growth. The funds would also be used to support a development office for the additional fundraising necessary to support the school after the original grant runs out. Recognizing that the school’s growth plan relies upon ambitious fundraising and faculty–generated grant projections, the school adopted contingency plans to reduce program size if fundraising does not meet expectations. The contingency plans were included as a response to concerns about the school’s financial projections that were raised by the systemwide academic committees during the review process. Even with the revised contingency plans, one academic committee rejected the proposal, citing that the Betty Moore Foundation grant would be insufficient to build and maintain the school over the long term.

Analysis of Problems With Existing Process

As demonstrated above, the approval process has resulted in some programs and schools that—based on our assessment—are not aligned with state priorities, are not cost–effective, or are duplicative of existing programs. Although each proposal is unique, we believe structural problems with the process allow proposals to move forward without proper consideration. We describe these problems below. In the final section of this report, we provide recommendations for remedying these problems.

Campus Interests—Not State Interests—Drive Proposals

A main problem with the proposal and approval process is that the program proposals originate from the campus and faculty level rather than as the result of systemwide coordination and priorities. Under the segments’ process for approving programs, the campuses decide the type of programs and schools they would like to create as well as make key decisions on the scope, size, and costs of those programs.

Proposals Reflect Campus Priorities. Under the current process, proposals sometimes reflect the priorities of a campus or its community, which may conflict with systemwide or statewide goals and priorities. Campuses understandably are motivated by institutional concerns such as increasing the prestige of the campus or responding to the interests of alumni or donors. For example, many program proposals cite enhancing the campus’ reputational rankings and keeping up with comparison institutions as important reasons for establishing new programs or schools. Although these can be important considerations, they should not by themselves justify new programs or schools. The UC Irvine law school illustrates how local community support, substantial private donations, and the goal of increasing the campus’ prestige can drive a proposal even in the face of clear evidence showing a lack of state need.

Lack of Systemwide or Statewide Coordination. The origination of proposals at the campus level can also work against systemwide and statewide coordination. Rather than the university systems or the Legislature laying out goals or priorities, the bottom–up planning structure defers to individual campuses significant responsibility for directing the growth of public higher education. A more coordinated approach was evident in UC’s systemwide plan to expand its health sciences programs in its publication A Compelling Case for Growth. In the end, however, campus plans were allowed to override the system’s goals, as UC Riverside pushed ahead its plan for a medical school contrary to the plan’s vision that new medical slots first be located at existing schools with unused capacity. The plan also only represented UC’s role in health sciences education rather than incorporating potential contributions from CSU and the community colleges in some fields.

State Input Occurs Too Late in the Process

Under the current review process, most of the major policy decisions regarding scope and cost are made at the campus level and through the segment’s review process prior to state review. As a result, the role of CPEC and the Legislature in setting policies is minimized.

Policy Decisions Are Made Prior to State Input. By the time a proposal comes to CPEC for review, major decisions have already been made through the segment’s review process. As a result, CPEC can ask clarifying questions or propose small changes, but in regards to the purpose, scope, and cost of the program, its only option is to accept or reject the proposal. Similarly, for those few proposals that include explicit funding augmentations requiring legislative appropriations, the Legislature is asked only to provide or deny funding—not to play a role in shaping the policies of the proposal. The CPEC and the Legislature, as the coordinating agency for higher education and the policymakers for California, respectively, should play a more active role in the policy decisions that form the basis of these proposals.

For example, the Legislature would eventually need to approve supplemental funding for the UC Riverside medical school to proceed. Under the current process, UC would request a specific amount of funding to meet the scope and cost of its finalized proposal—a distributed–model medical school at UC Riverside. This presents the Legislature with an oversimplified and difficult choice: provide the requested funding for the new medical school or leave an asserted need of the Inland Empire unaddressed. In fact, as outlined in our analysis above, the Legislature has additional options for addressing the shortage of doctors, such as a smaller medical school or the expansion of existing medical schools. The policy questions presented to the Legislature should be: “Does the state need to train additional medical doctors? If so, what is the most efficient and effective way to achieve it?” Instead, the Legislature is relegated to essentially signing off on the segments’ spending plans. It is possible that, after hearings and additional research, the Legislature would ultimately adopt the campus’ proposal, but it is also possible that the Legislature—with a wider view of budget implications and state priorities than campus officials—would recommend changes to the proposal.

Proposals Gain Significant Funding and Momentum Prior to State Review. The current process also allows proposals to gain significant support and momentum before they are presented to the Legislature and CPEC, making rejection or modification more difficult. Typically, proposals take advantage of private donations in the early stages of planning. As a result, significant financial resources are committed to the new program or school before state policymakers have considered it. For example, full–time staff were already employed developing the new nursing school at UC Davis and the new medical school at UC Riverside even though these schools had not yet received the final approval of the UC Regents, been reviewed by CPEC, or received any state funding from the Legislature. Although rejecting or altering certain proposals may be in the state’s interest, such actions are difficult to make when the campus has already spent donations and grants, secured additional donations and grants, hired full–time employees for fundraising and planning, and earned public support.

Campuses also receive private donations that are contingent upon state financial support. For example, the UC Davis school of nursing and the UC Riverside school of medicine each have sizeable donations that become available only if the Legislature appropriates funds to the proposal and commits to support the new school. Leveraging state funds in this way can be an effective way for the segments to attract additional resources, but gaining private support for proposals prior to legislative funding places the Legislature in a difficult position—rejecting the proposal means leaving behind available funds. Although the availability of private funding should be a consideration in approving new schools and programs, there are other criteria that should be satisfied first: state needs, state priorities, and cost–effectiveness. Additionally, private donations are typically fixed sums while the state will annually incur the ongoing enrollment costs. In other words, the use of outside funds should be encouraged and adds valuable resources to the higher education segments, but it should not drive policy decisions or be used as justification for unworthy proposals.

Review Criteria Inadequate

We think the seven review criteria employed by CPEC to evaluate proposals are insufficient for assessing deficiencies or identifying improvements with the submitted proposals. As shown in our review of UC Riverside’s public policy school proposal and medical school proposal, CPEC concurred with proposals without raising concerns that our criteria identified. This occurred mostly because CPEC’s criteria do not address these issues (see Figure 3 on page 10).

CPEC Review Does Not Consider Priorities. One shortcoming of CPEC’s criteria is that they consider each proposal in isolation without examining where it ranks within the context of all of the state’s higher education priorities. For example, CPEC approved the new public policy school at UC Riverside because it concluded the graduates would fill societal needs within the public policy profession and the costs were reasonable. However, CPEC did not consider how public policy’s workforce needs and the school’s costs compared with other higher education priorities requiring funding from the state’s limited resources—a factor which, in our view, should have at least delayed planning for the school. In this case, the campus decided to delay the school recognizing that opening the school was not a high priority given the constraints in state funding.

CPEC Review Does Not Consider Alternatives. The CPEC criteria also insufficiently consider policy alternatives that could achieve a proposal’s goals more efficiently or at a lower cost. The commission raised concerns about the cost of UC Riverside’s medical school, but ultimately accepted the proposal contingent upon adequate state funding. The criteria did not lead CPEC to question whether more cost–effective alternatives existed for meeting the school’s goals. An adequate review process should at least require the proposal to identify relevant alternatives and explain why the chosen alternative is preferable.

Statutory Framework Is Weak

In most states, the higher education coordinating agency’s review is binding—if the coordinating agency does not concur with the proposal, the university may not move forward unless the Legislature overrides the coordinating agency’s decision. In California, statute specifies that CPEC’s review is only advisory, and thus programs and schools can be implemented even when CPEC finds they do not meet state goals. For many years the segments would not implement proposals without CPEC’s concurrence. However, UC’s decision to continue with UC Irvine’s law school despite CPEC’s objections raises serious questions about the current process.

The current system does not provide a formal role for the Legislature in these important policy decisions that affect the universities’ costs and the direction of their enrollment growth. In most cases, the Legislature only becomes involved in the process if the proposal requires a change in statute or supplemental state appropriations. For example, the Legislature’s involvement was necessary to allow CSU to offer educational doctorates because it required a change in statute for CSU to offer degrees at the doctoral level. The Legislature was able to assert its priorities for funding the new programs. The Legislature also had some involvement in the PRIME expansion when it was asked to provide supplemental funding for the associated enrollment growth. Similarly, UC Riverside will need the Legislature’s approval for enrollment funding at its future medical school, as well as funding for startup costs. Through the budget, therefore, the Legislature is able to consider some of the policy and cost implications of the proposals and provide some oversight. However, proposals such as the UC Irvine law school or the UC Riverside public policy school that do not rely on special enrollment augmentations do not require explicit approval from the Legislature—the school’s enrollment is simply included in the system’s overall enrollment target. This means that the creation of some new schools and programs is not transparent in the overall budgets of the segments.

State Lacks Data for Proper Workforce Analysis

Determining student demand for new programs and schools and projecting workforce needs requires substantial data and analysis. The EDD forecasts labor demand for many professions, but labor supply forecasts are irregular, usually the result of studies undertaken by universities or foundations. As a result, many proposals for new schools or programs rely upon anecdotal evidence of labor trends or require custom studies of labor supply in particular fields. For example, UC’s plan for expanding health science programs is based upon its A Compelling Case for Growth publication, which incorporates a combination of new research and existing studies by outside researchers. The CPEC has traditionally not undertaken extended studies on labor supply and demand. Its detailed workforce analysis for the UC Irvine law school proposal, for example, relied on previous work by RAND and its analysis of the UC Riverside medical school proposal accepted the data provided in UC’s proposal and one outside study as evidence of the need for more medical doctors.

Recommendations for Improving the Approval Process

In this report, we have identified a number of shortcomings in the current process used by the higher education segments and the state for approving new programs and schools. We believe the Legislature, the state’s higher education coordinating agency, and the segments have opportunities to reform this process in a way that improves statewide coordination and legislative participation, ensures new programs and schools are aligned with the state’s interests, and makes use of reliable data and in–depth analysis.

In the following section, we provide recommendations for improving the approval process for new programs and schools. Our recommendations include changes to CPEC’s role in the process. However, several past and current bills have sought to eliminate or radically change the commission. In our view, the policies that we recommend for CPEC would be important for any statewide higher education coordinating agency, whether it is CPEC or a newly formed replacement agency.

Improve Data and Analysis

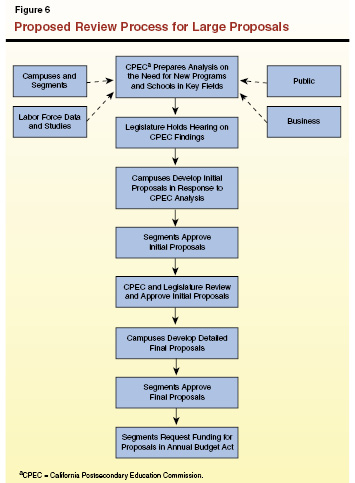

Any credible assessment of a new school or program should begin with an analysis of the supply and demand in that field. As mentioned in this report, the state does not forecast labor supply, and proposals for schools and programs typically rely on independent studies to support workforce claims. In order to properly evaluate whether higher education’s programs are aligned with the state’s needs, CPEC should periodically measure supply and demand in major fields. Such reports should critically evaluate:

- Does the state need to train more students for this profession?

- Is there appropriate opportunity for residents to obtain training for this profession?

- If the state decides to educate more students for this profession, should it do so by increasing enrollment in existing programs or should it create new programs?

These studies could build off of data already provided by the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics and EDD as well as CPEC’s database on degrees conferred. Additional data could be compiled from professional organizations, licensing agencies, independent studies, and the segments’ research.

Many states already conduct such studies through their coordinating agencies for higher education. For example, the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board projects the need for new professional schools with reports that are updated every five years. Such reports provide guidance to the higher education institutions and the Legislature on what programs should be the focus of planning. The CPEC performed a similar study of the law profession in order to respond to UC Irvine’s law school proposal. However, CPEC should change its focus from primarily responding to program proposals and instead routinely conduct these studies in order to provide a framework for planning new schools and programs. For example, workforce need studies could be conducted in major professions—such as medical doctors, nurses, lawyers, teachers, and engineers—every five years. Rather than performing the analyses in response to already submitted proposals, these upfront studies would signal to the universities which programs they should consider initiating and which programs would be unnecessary. If CPEC’s analysis preemptively showed that California would not need a new law school in the next five years, a campus could not justify planning such a school.

Increase Coordination and Guidance in the Planning Process

Reverse the Planning Structure. The development of state workforce projections would allow for more centralized and coordinated planning for new schools and programs. With this information, the statewide coordinating agency could identify statewide needs for new programs and then the campuses could respond with proposals to meet the identified needs. For example, if a report identified the need for more public policy graduates in the Inland Empire, it would have the effect of inviting campuses in that region to develop public policy proposals. This change in the planning structure would ensure that societal need—rather than donor contributions or campus interests—drives proposals. If more than one campus were interested, the resulting competition could increase the quality and cost–effectiveness of the proposals.

The UC’s health sciences initiative provides a good example of such a planning structure. The plan identified which professions would need additional students and analyzed the most efficient way to meet the supply needs. Numerous schools responded with proposals to expand medical, nursing, and public health enrollments. Additionally, the plan communicated to campuses potentially considering expansions in dentistry or optometry that those expansions were not a priority. (As noted earlier, the limitation of UC’s publication is that it did not incorporate the other segments—for example, planning nursing expansion without coordination with CSU and CCC—and that it lacks the authority of a state–sanctioned report.)