January 2009

Improving Academic Success For Economically Disadvantaged Students

Executive Summary

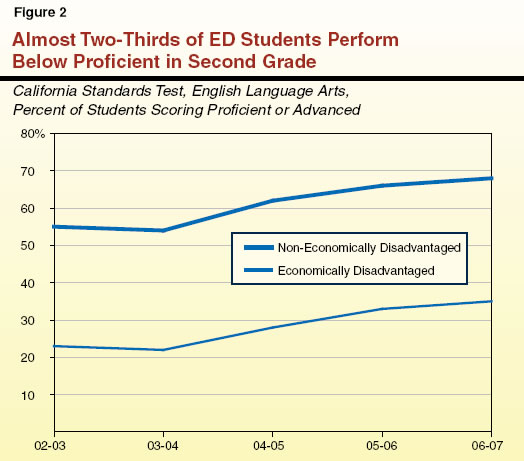

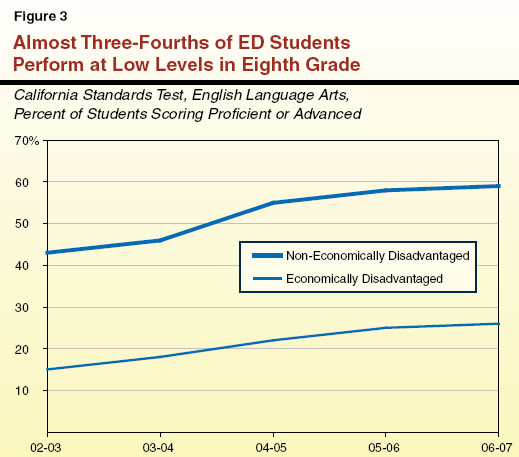

California’s economically disadvantaged (ED) students are failing to meet federal and state academic standards and generally perform below their non–economically disadvantaged (NED) peers. This trend appears in all grade levels, with nearly two–thirds of second grade ED students and nearly three–fourths of eighth grade ED students performing at low levels. In addition, ED students are much more likely to drop out than their peers. Today, more than 45 programs operate and more than $9 billion in state and federal monies are spent each year in California to support approximately three million ED students. Despite these efforts, ED students continue to perform below expectations and below their NED peers.

Recognizing that no single program is likely to help all ED students succeed in school, we believe California’s existing approach for helping these students fails on virtually every score. Specifically, it:

- Does not focus on the underlying barriers to academic success.

- Consists of a hodgepodge of disconnected programs.

- Does not link funding to the prevalence and severity of academic barriers and the cost of overcoming them.

- Is neither centered around improving academic achievement nor well–integrated into the state’s overall accountability system.

- Does not collect and disseminate useful information on program outcomes.

Given these shortcomings, we believe the state needs to be both more strategic and more flexible in its approach to supporting ED students. We recommend five steps the state can take to improve the existing system. Specifically, we recommend:

- Redefining the conversation to focus on the barriers impeding academic success.

- Simplifying the system for all involved.

- Refining funding formulas to reflect the pervasiveness and severity of students’ academic challenges.

- Strengthening overall accountability by measuring year–to–year growth in student achievement.

- Identifying and facilitating the sharing of best practices.

We recognize this process likely will take time to complete and recommend the state continue to make refinements as more information becomes available. In particular, we recommend the state build on research that identifies barriers to academic success as well as effective strategies for overcoming those barriers. In both the near and long term, our recommendations would not increase ongoing costs at either the state or local level—instead consolidating existing programs and pooling existing resources.

Introduction

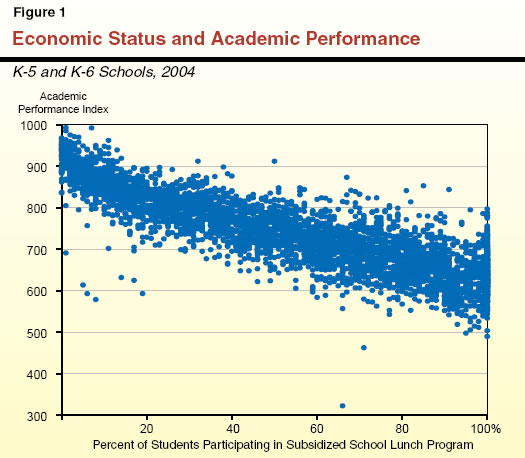

In California, the percent of ED children in public schools has been steadily increasing. In 1992–93, approximately 40 percent of public school children were ED, as measured by eligibility for the federal Free and Reduced Price Meal program (which requires family income to be at or below 185 percent of the federal poverty guidelines). By comparison, in 2006–07, 50 percent of public school children (approximately three million) were ED. This trend is of concern in part because students’ economic status is consistently correlated with academic performance. The Getting Down to Facts (GDTF) report, published by Stanford University in March 2007, is one of the latest reports to highlight this correlation. Figure 1, from the GDTF summary report, shows the strong correlation between the size of a school’s ED population and its score on the Academic Performance Index.

Much Money Is Spent on Programs to Serve These Kids. Many programs have been created over the years to help ED students succeed. Today, more than 45 programs operate and more than $9 billion in state and federal monies are spent each year in California to serve this population of students. This represents roughly one–half of all categorical programs and 40 percent of all categorical spending.

Are Efforts on Target? This report provides data on the academic performance of ED students and surveys the programs that are designed to serve them. The report reviews trends in program spending and participation and attempts to look at the effectiveness of these programs individually and in the aggregate. Finally, it identifies shortcomings with the state’s existing approach to serving ED students and makes recommendations designed to improve the performance of these students.

Academic Achievement of ED Students Consistently Below Standards and Peers

The ED students, on average, consistently achieve below federal and state standards and at lower levels than their NED peers. On average, California’s ED students have lower scores than their peers on state assessments at all grade levels. They also drop out of school at much higher rates than their peers. California’s ED students also consistently score at the bottom of national assessment comparisons. Taken together, these data (discussed in more detail below) show California’s ED students have a well–established and consistent trend of underperforming academically.

Low Achievement for ED Students in Elementary and Middle School. Reflected in Figure 2, almost two–thirds of second grade ED students did not achieve a score of “proficient” or above on the California Standards Test (CST) in English Language Arts (ELA). For eighth grade ED students, almost three–fourths did not score proficient or above (reflected in Figure 3). Additionally, in both grades, ED students were far below their NED peers. The percentage of NED students scoring proficient or above on the CST in ELA is more than 30 points higher than their ED peers in both second and eighth grade. Although scores for all students have been increasing over the years, the achievement gap between the ED and the NED has not changed significantly.

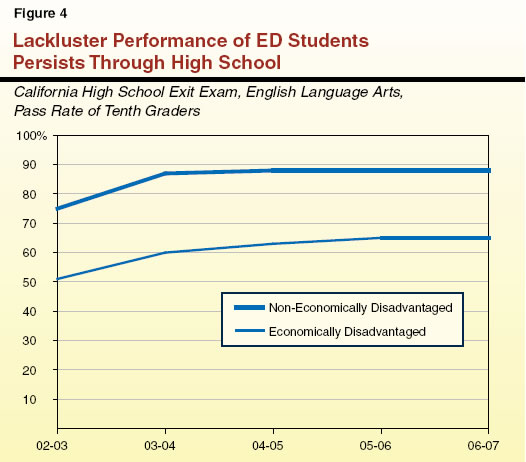

Low Achievement Persists at High School Level. At the high school level, ED students have lower exit exam pass rates and higher dropout rates than their peers. Figure 4 shows that each year for the past five years, roughly one–fourth fewer ED students pass the California High School Exit Examination in ELA than NED students. For example, in 2006–07, 88 percent of NED students passed the exit exam whereas only 65 percent of ED students passed. As with elementary and middle school students, the pass rate for both groups of students has been increasing slightly over time, but the gap between the ED and NED has not changed significantly. As for dropout rates, California does not yet have individual–level data for an entire student cohort, but available data indicate ED students are dropping out at a considerably higher rate than their NED peers.

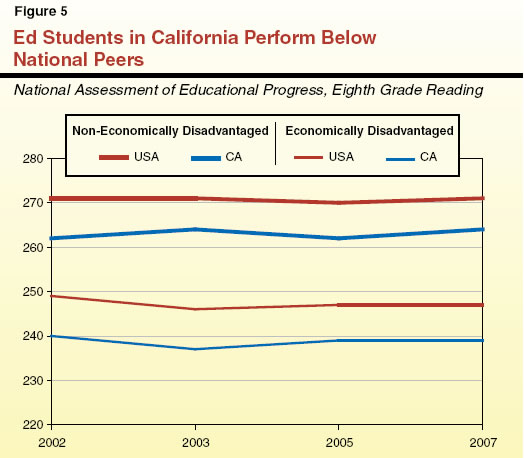

Low Achievement Also Evident on National Tests. Scores from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) show underperformance similar to that found on California tests. Figure 5 shows the average score of eighth graders on the NAEP reading test. In 2007, California’s ED students scored 23 points (9 percent) lower than California’s NED students. Although the achievement gap is not significantly larger in California than in other states, both ED and NED students in California score lower than their national peers. As shown in Figure 5, ED students in California consistently score about 8.5 points (3 percent) lower than their national ED peers. Indeed, California’s ED students, on average, receive some of the lowest scores in the country. For example, California ranked 49th of all states in the performance of its ED students on the eighth grade national reading test in 2007.

Plethora of Programs Designed for ED Students

This section describes the 47 state and federally funded programs designed to serve ED students. Each of the identified programs have eligibility criteria based on some measure of economic disadvantage—typically family income equal to a specified percentage of the federal poverty guidelines ($20,650 for a family of four in 2007) or the state median income ($67,000 for a family of four in 2007–08). This report does not include information on programs designed primarily to address other factors, even if those programs serve many ED students. For instance, this report does not include information on programs for teen parents, foster youth, English Learner (EL) students, or special education students.

For convenience, we organized the 47 programs into five categories:

- Early Childhood Education (ECE)

- Child Care and After School Activities

- Academic Achievement

- Nutrition

- Facilities

Figure 6 identifies the programs by category. Short descriptions of these categories and programs follow.

Figure 6

A Plethora of Programs Serving California's ED Students |

2007‑08 |

|

State Funded |

Federally Funded |

Early Childhood Education (7) |

|

|

Head Start, Early Head Start, Migrant Head Start, Tribal Head Start |

|

X |

State Preschool, Pre-Kindergarten Family Literacy program |

X |

|

Healthy Start |

X |

|

Child Care and After School Activities (11) |

|

|

Child care programs (general, alternative payment, CalWORKsa Stage 1, CalWORKs Stage 2,

CalWORKs Stage 3, campus, migrant, handicapped, latchkey) |

X |

X |

After School Education and Safety |

X |

|

21st Century Community Centers |

|

X |

Academic Achievement (19) |

|

|

Title I, Part A—Basic Grants |

|

X |

Title I, Part B—Literacy Programs (William F. Goodling Even Start Family Literacy, Reading First, Early Reading First) |

|

X |

Title I, Part G—Advanced Placement Programs (Incentive Grants, Fee Reimbursement) |

X |

X |

Pupil Retention Block Grant (Elementary School Intensive Reading, Intensive Algebra Instruction Academies,

Continuation High School Foundation, High Risk Youth Education and Public Safety, Tenth Grade Counseling, District Opportunity Classes and Programs, Dropout Prevention and Recovery, Early Intervention for School

Success, and At-Risk Youth for Los Angeles Unified School District) |

X |

|

Title VI, Part B—Rural and Low-Income Schools |

|

X |

Economic Impact Aid, Charter School Categorical Block Grant—Disadvantaged Student Component |

X |

|

Advancement Via Individual Determination |

X |

|

Nutrition (8) |

|

|

Summer Food Service |

|

X |

School Nutrition Programs (National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, Seamless Summer Feeding Option, Special Milk Program, State Meal Program) |

X |

X |

Child and Adult Care Food |

|

X |

School Breakfast and Summer Food Start-Up or Expansion |

X |

|

Facilities (2) |

|

|

Qualified Zone Academy Bonds |

|

X |

Charter School Facility Grant |

X |

|

|

a California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids. |

Early Childhood Education Programs

The ECE category includes programs for children and their families that are intended to increase the cognitive and behavioral abilities of children under five years of age. The federal government runs four ECE programs and the state runs three ECE programs. Together, these programs serve more than 220,000 children each year.

Head Start. As shown in Figure 6, Head Start consists of four federal programs, all of which aim to prepare ED children to succeed in school. Head Start provides comprehensive child development services from birth through preschool. Home visits are common for younger children and their families, whereas older children are typically served in center–based preschool programs. In addition to Head Start and Early Head Start, the federal government also operates special migrant and tribal programs for young children in those communities. Although Head Start is a federal initiative, grantees are awarded funds and monitored through state chapters. Approximately 100,000 California children participate in Head Start each year.

State Preschool. California also offers two state preschool programs. State Preschool programs serve three– and four–year old children whose families earn less than 75 percent of the state median income. Pre–Kindergarten Family Literacy (PKFL) programs, created in 2005, are nearly identical, center–based preschool programs. The notable distinctions are that PKFL programs must include a family literacy component and be located in the attendance area of low–performing elementary schools. State Preschool and PKFL providers contract with the state for a maximum level of service and then are reimbursed at the same predetermined rate after service has been provided. Approximately 110,000 children attend state preschool programs each year.

Healthy Start. California also offers Healthy Start grants. The Healthy Start program offers state–funded school–community collaborative grants for integrating services to support academic success for children and families. Grants may be used for various types of collaboration. For example, grants may be used to connect families with community health resources, offer family literacy programs in collaboration with local libraries, and teach parenting classes in collaboration with community colleges. Healthy Start estimates serving approximately 13,000 children annually.

Child Care and After School Programs

This category includes the various state and federally funded programs designed to serve children before and after school. Child care typically serves children from birth through age 11 and runs yearlong. By comparison, after school programs serve school–age children through high school during the school year. Nine child care programs exist (one supported entirely with federal funds, four state funded, and four funded by a combination of federal and state monies). Two after school programs currently exist (one federally funded and one state funded). Approximately 450,000 children are served by this category of programs.

Child Care Programs. California operates nine child care programs serving ED children from birth through age 11 (or older for special populations). The funding mechanism for child care programs varies slightly across programs, but essentially providers are awarded a contract for a maximum level of service and then reimbursed after child care has been provided. Although providers must meet specified health and safety and programmatic requirements, they are not subject to formal academic or curriculum requirements. More than 300,000 children are served by these programs each year.

After School Programs. The federal government operates an after school program called 21st Century Community Learning Centers and the state operates a similar program called After School Education and Safety (ASES). Both programs aim to offer school–age students a safe environment after school to do homework and engage in enrichment activities. Providers for both programs receive grants and, in return, submit regular reports including attendance counts to the California Department of Education. Together, these programs serve approximately 150,000 students annually.

Academic Achievement Programs

This category includes 19 programs intended to directly improve the academic performance of ED students in kindergarten through 12th grade. Five of these programs are solely funded with federal monies, 12 are solely funded with state monies, and 2 are funded with both federal and state monies. These programs serve nearly every local educational agency (LEA) in the state.

Federal Title I, Basic Grants. Title I, created by the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in 1965, consists of 15 federal programs intended to ensure that disadvantaged students have the opportunity to reach proficiency on state assessments through high–quality education. Title I was reauthorized with the No Child Left Behind Act in 2002 and is currently the largest federal initiative supporting elementary and secondary education. Of the 15 Title I programs, Basic Grants is by far the largest program and the most flexible. Few restrictions are put on how the funding may be used, but schools receiving Basic Grants must participate in the federal accountability program and accept intervention if test scores do not meet federal targets. Basic Grants are completely funded with federal monies. Approximately 1,000 LEAs participate in the Basic Grants program.

Federal Literacy Programs. The federal government also funds literacy programs. Even Start, Reading First, and Early Reading First are all designed to help children master reading in the early years. These programs, solely funded with federal monies, are used by approximately 200 districts across the state.

Advanced Placement (AP) Programs. California currently operates two AP programs. The first program is intended to increase the number of students who participate and succeed in AP courses. The AP courses prepare high school students for the rigor of college courses. The AP courses are also intended to prepare students to take AP exams that, if passed with a mark of 4 or 5, will grant them college credit. The second program covers AP (and International Baccalaureate) test fees for ED students. Both programs are funded with a combination of federal and state funds. Approximately 200 districts participate in these AP programs.

Pupil Retention Block Grant. The state–funded Pupil Retention Block Grant consolidates nine programs intended to assist students at risk of academic failure and dropping out. These programs range from counseling to tutoring and are available in more than 450 districts.

Federal Rural Program. The Rural Education Achievement Program (REAP) is designed to help rural districts by supplementing funding allocations that otherwise would be too small to run a program. One of the two REAP programs, the Rural and Low–Income School Grant, provides funds for improving the achievement of children in rural and low–income schools by supporting activities such as teacher recruitment and retention, teacher professional development, educational technology projects, and parental involvement activities. This program is solely funded with federal monies and serves approximately 29 districts.

Economic Impact Aid (EIA) Program. The EIA program is a state program that provides funding to support supplemental services for educationally disadvantaged (including ED) students and EL students in public schools. School districts use this funding for a variety of purposes, including: (1) extra assistance for low–achieving pupils, (2) supplemental instruction services for EL students, (3) training for teachers who instruct EL students, and (4) supplementary materials. Charter schools receive funding in lieu of EIA via the Disadvantaged Student Component of the Charter School Categorical Block Grant. Nearly every LEA in California receives EIA or funding in lieu of EIA.

Advancement Via Individual Determination (AVID) Program. The AVID program is an academic support program for middle and high school students. This state–funded program places students from disadvantaged backgrounds into college–preparatory classes. Only students who demonstrate a desire to go to college and a willingness to work hard are accepted into the program. The AVID grants are disseminated to schools through 11 regional offices and serve approximately 100,000 students each year.

Nutrition Programs

Nutrition is one of the largest categories of expenditures for ED students. Eight nutrition programs provide subsidized food services to ED students in California. The nutrition services provided to students include milk, breakfast, and lunch. Service is provided during the school year as well as during school breaks and summer. The majority of the nutrition programs are funded on a reimbursement basis using primarily federal monies. It is estimated that these programs serve more than 720 million meals each year.

Facilities Programs

There are two small programs available to help schools with large ED populations fund facilities and equipment. The Charter School Facility Grant program is a state grant available to charter schools serving ED populations. The grant may be used for rent and lease expenses. The Qualified Zone Academy Bonds program is a federal initiative. It provides public schools that have large ED populations with interest–free loans. The loans are intended to fund innovative school programs in partnership with local businesses. Combined, these programs serve more than 150 schools each year.

Substantial Investment in Helping ED Students

This section summarizes funding trends. As noted above, 15 of the 47 programs are solely supported with federal funds, 19 are solely supported with state funds, and 13 are funded with both state and federal monies. Figure 7 shows the total funding for each of the five categories from 2000–01 through 2007–08.

Figure 7

Investment in California's ED Students Has Steadily Increased |

Appropriation by Category

(In Millions) |

Category |

2000‑01 |

2001‑02 |

2002‑03 |

2003‑04 |

2004‑05 |

2005‑06 |

2006‑07 |

2007‑08 |

Early Childhood Education (7) |

$1,100 |

$1,129 |

$1,118 |

$1,117 |

$1,151 |

$1,154 |

$1,246 |

$1,244 |

Child Care and After School Activities (11) |

1,673 |

1,812 |

2,167 |

2,137 |

2,188 |

2,261 |

2,808 |

3,351 |

Academic Achievement (19) |

1,449 |

2,098 |

2,342 |

2,414 |

2,496 |

2,537 |

2,939 |

2,917 |

Nutrition (8) |

1,254 |

1,299 |

1,351 |

1,539 |

1,719 |

1,742 |

1,756 |

1,782 |

Facilities (2) |

56 |

53 |

58 |

57 |

58 |

58 |

85 |

20 |

Totals |

$5,532 |

$6,391 |

$7,036 |

$7,264 |

$7,612 |

$7,752 |

$8,834 |

$9,314 |

California’s Investment in ED Students Has Steadily Increased. As Figure 7 shows, approximately $9 billion is currently being spent on programs for ED students in California. Funding has been steadily increasing across all categories over the past eight years. Figure 8 shows funding levels by program for 2007–08. The federal Title I, Basic Grants program is the largest single program at more than $1.6 billion. The EIA funding is also over $1 billion annually. Head Start, ASES, and School Nutrition are also substantial—spending more than $500 million each. Child Care is divided into nine funding streams but combined funding is more than $2.6 billion each year—making it the largest subcategory of funding for ED children.

Figure 8

Investment in California’s ED Students Spread Across Many Programs |

(In Millions) |

|

2007‑08 Fundinga |

Program (Number of Programs) |

State |

Federal |

Total |

Early Childhood Education (7) |

|

|

|

Head Start, Early Head Start, Migrant Head Start, Tribal Head Start |

— |

$825 |

$825 |

State Preschool, Pre-Kindergarten Family Literacy program |

$419 |

— |

419 |

Healthy Startb |

— |

— |

— |

Totals |

$419 |

$825 |

$1,244 |

Child Care and After School Activities (11) |

|

|

|

Child care programs (9) |

$1,553 |

$1,065 |

$2,618 |

After School Education and Safety, 21st Century Community Learning Centers |

547 |

186 |

733 |

Totals |

$2,100 |

$1,251 |

$3,351 |

Academic Achievement (19) |

|

|

|

Title I, Part A—Basic grants |

— |

$1,608 |

$1,608 |

Title I, Part B—Literacy programs (3) |

— |

188 |

188 |

Title I, Part G—Advanced Placement programs (2) |

$2 |

3 |

5 |

Pupil Retention Block Grant (9) |

98 |

|

98 |

Title VI, Part B—Rural and Low-Income Schools |

— |

1 |

1 |

Economic Impact Aid, Charter School Categorical Block Grant—Disadvantaged Student Component |

1,008 |

— |

1,008 |

Advancement Via Individual Determination |

9 |

— |

9 |

Totals |

$1,117 |

$1,800 |

$2,917 |

Nutrition (8) |

|

|

|

Summer Food Service |

— |

$23 |

$23 |

School nutrition programs (5) |

$135 |

1,613 |

1,748 |

Child and Adult Care Food |

— |

10 |

10 |

School Breakfast and Summer Food Start-Up or Expansion |

1 |

— |

1 |

Totals |

$136 |

$1,646 |

$1,782 |

Facilities Financing (2) |

|

|

|

Qualified Zone Academy Bonds |

— |

$20 |

$20 |

Charter School Facility Grantc |

— |

— |

— |

Totals |

— |

$20 |

$20 |

|

a May not add due to rounding. |

b No funding provided in 2007‑08. In 2006‑07, $10 million was budgeted. |

c No funding provided in 2007‑08. In 2006‑07, $9 million was budgeted. |

Existing System Fails on Virtually Every Score

Some programs described in this report—child care, child nutrition, and facility programs—presumably are not designed to boost academic achievement directly nor is that their sole objective. Other programs however—including the 7 ECE programs, 2 after school programs, and 19 academic achievement programs—presumably are designed primarily or exclusively to meet this objective. Unfortunately, despite these 28 academically oriented programs and the almost $5 billion investment made in them each year, the academic achievement of ED students is still low and the gap between ED and NED students is as wide today as it was five years ago.

While recognizing that no single program is likely to help all ED students succeed in school, California’s existing approach for helping these students fails in virtually every way. Specifically, (1) it does not focus on the underlying causes of poor performance and barriers to academic success, (2) it consists of a hodgepodge of disconnected programs, (3) funding is not closely linked to the cost of educating students, (4) the programs neither are centered around academic achievement nor well–integrated into the state’s overall accountability system, and (5) useful information on program outcomes is not readily available to guide state and local decisions. Below, we discuss these shortcomings in more detail.

Missing Opportunities to Address Root Causes. Currently, approximately three million students facing a wide range of barriers to academic success are eligible for the same intervention programs, largely in the same way, at the same funding rates—all because they have been categorized as economically disadvantaged. Under such a system, the focus largely revolves around targeting more resources to ED students rather than addressing underlying issues likely to be affecting academic performance. For instance, students from ED families may lack health care, be in single–parent homes living on public assistance, have absent parents or parents with little formal education, have parents in jail or addicted to drugs, be parents themselves, live in unsafe neighborhoods, lack nurturing relationships with adults, speak a primary language other than English, be influenced by gang pressures, and/or need to work long hours outside of school. By focusing so much attention and resources on a student’s economic status, the state is missing opportunities to address the root causes of achievement problems. Without identifying and focusing on these underlying causes, neither the state nor school districts can act strategically to mitigate them.

Hodgepodge of Programs. Currently, local education agencies must weave through a maze of programs designed to serve ED students. As described earlier, a school district currently can use funds from more than two dozen different programs—and face more than two dozen sets of corresponding program requirements—to serve the same ED youth. Because each program has its own set of specific requirements, program providers have little incentive to coordinate services with other program providers serving the same students. The difficulty of navigating such a system is compounded by a host of different program providers—the state, regional centers, county offices of education, county hospitals, city governments, school districts, school sites, community–based organizations, and private companies. For example, a child can receive reading intervention at school, participate in an after school program run by the city park department, and receive mental health services through a county–run Healthy Start program. Though the various programs presumably work toward their own ends, none is held responsible for ensuring students receive an overall set of appropriate, well–integrated services.

Funding Not Linked to Cost of Overcoming Barriers. Despite the wide range of barriers to academic success, wide differences in individual circumstances, and wide variations in performance among ED students, California’s existing funding structure essentially treats all ED students the same. That is, programs generally provide school districts with a uniform funding amount per ED student. Such a funding system does not account for potentially significant differences in the cost of overcoming different academic barriers. As a result, schools with students who face multiple barriers (such as lack of health care, low parental education level, and parent absenteeism) or relatively costly barriers (such as dealing with gang influence in the neighborhood) are provided roughly the same amount of categorical funding as schools with students who face fewer barriers or less costly barriers to overcome. In short, funding is not closely linked to the cost of addressing underlying problems.

Programs Poorly Integrated Into State’s Accountability System. Even with the plethora of existing programs, requirements, and funding streams, the existing system is not centered around improving student academic achievement. This is true even for the 28 academically oriented programs. Indeed, with the exception of Title I, Basic Grants and Reading First, none of the programs described in this report require LEAs to improve students’ academic achievement. In fact, many programs have no performance requirements at all, only compliance requirements. Of even greater concern, the state’s overarching assessment and accountability system currently lacks the wherewithal to measure year–to–year improvements in the academic achievement of at–risk students.

Useful Data Not Readily Available to Guide Decision Making. The current system also suffers from evaluations that have been infrequent, unreliable, uninformative, and inconsistent—resulting in a lack of quality data on program outcomes. Figure 9 shows that more than half of the programs designed for ED students have not undergone any evaluation to measure their effectiveness. Of those programs that have been evaluated, most merely describe program activities, identify the number of students served, and self–report on outcomes. Very few programs have been independently evaluated. Even fewer have had independent evaluations that include quantifiable performance measures. Indeed, the evaluations conducted to date have not reported in a consistent way on any common set of performance measures. As a result, determining program effectiveness and comparing effectiveness across programs is nearly impossible. This lack of independent and quality information hinders the ability of state and local leaders to make informed decisions about what strategies to use in helping students succeed and what changes could be made to spur further improvements.

Figure 9

Program Evaluations Inconsistent |

Programs by Category |

|

|

Early Childhood Education |

Evaluated? |

Year Evaluated |

Head Start, Early Head Start, Migrant Head Start, Tribal Head Start |

Yes |

2001, 2002, 2005 |

State Preschool, Pre-Kindergarten Family Literacy |

No |

— |

Healthy Start |

Yes |

1995, 2002 |

Child Care and After School Activities |

|

|

Child care programs |

No |

— |

After School Education and Safety |

Yes |

2005 |

21st Century Community Learning Centers |

Yes |

2003, 2005,

2006, 2007 |

Academic Achievement |

|

|

Title I, Part A—Basic Grants |

Yes |

2006 |

Title I, Part B—Literacy Programs: Even Start |

Yes |

1998, 2004, 2005 |

Title I, Part B—Literacy Programs: Reading First |

Yes |

2006 |

Title I, Part B—Literacy Programs: Early Reading First |

Yes |

2007 |

Title I, Part G—Advanced Placement Programs |

No |

— |

Pupil Retention Block Grant |

No |

— |

Title VI, Part B—Rural and Low-Income Schools |

No |

— |

Economic Impact Aid, Charter School Categorical Block Grant—Disadvantaged Student Component |

No |

— |

Advancement Via Individual Determination |

Yes |

2000 |

Nutrition |

|

|

Summer Food Service |

Yes |

2006 |

School nutrition programs |

Yes |

2006 |

Child and Adult Care Food |

Yes |

2006 |

School Breakfast and Summer Food Start-Up or Expansion |

No |

— |

Facilities |

|

|

Qualified Zone Academy Bond |

No |

— |

Charter School Facility Grant |

Yes |

2003 |

A New System With a New Focus

We believe the state should replace its existing system of support for ED students with a new system revolving around the major determinants of academic success. Under the new system, LEAs would be afforded much greater flexibility. We believe flexibility at the local level is warranted both because LEAs typically are familiar with the challenges their students face and because of the wide range of barriers that might be prevalent within and across communities. Nonetheless, we think the state still has an important role in the improvement process—systematically assessing barriers to academic achievement; ensuring funding is distributed based on the prevalence, severity, and cost of overcoming these barriers; measuring the results of state and local investments; and sharing those results with educators and the public. Specifically, we recommend five steps the state can take to improve the existing system (see Figure 10), as discussed in more detail below.

- Redefining the conversation to focus on the barriers impeding academic success.

- Simplifying the system for all involved.

- Refining funding formulas to focus on students’ academic challenges.

- Strengthening overall accountability by measuring year–to–year growth in student achievement.

- Identifying and facilitating the sharing of best practices.

Our recommendations would not increase ongoing costs at either the state or local level—instead consolidating existing programs and pooling existing resources. Our recommendations focus only on state programs under the control of the Legislature to modify. (We believe that similar changes in federal programs would be productive.)

Figure 10

Five Steps Towards Refining State’s Approach to Supporting At-Risk Students |

Existing System: |

New System: |

- Ignores underlying barriers to academic success.

|

- Focus on barriers to academic success.

|

- Consists of hodgepodge of disconnected programs.

|

- Simplify system by consolidating many existing programs into one large block grant.

|

- Does not link funding to academic barriers.

|

- Link funding to cost of overcoming barriers to

academic achievement.

|

- Is neither centered around academic achievement nor well-integrated

into state’s accountability system.

|

- Strengthen overall accountability by measuring year-to-year growth in student achievement.

|

- Does not make useful data readily available to

decision makers.

|

- Collect and disseminate data on outcomes to

foster continuous improvement.

|

Refocus the Discussion. We recommend the state fund an independent study that would assess the impact of various barriers on academic performance. For example, the study could control for family income and then compare the effect of such factors as parent education, amount of adult supervision, amount of structured study time, English language proficiency, teen pregnancy, and neighborhood violence on academic performance. For each possible indicator, the study could determine: (1) the indicator’s relationship to academic achievement, (2) the method by which accurate data could be collected, and (3) gradients of risk and estimated costs of overcoming the related barrier. Once completed, the results of the study could be used to help the state craft a new corresponding funding formula that better reflected the prevalence and severity of the academic barriers students confront. It also could help inform local implementation decisions, enabling LEAs to develop more strategic approaches to addressing barriers and craft more effective responses. We estimate such a study would cost approximately $500,000.

Simplify System. The current system distracts LEAs from focusing on barriers to student success by forcing school districts to spend time accessing multiple funding streams and complying with seemingly countless program requirements. To ease bureaucratic complications at the state and local levels and focus efforts on students, we recommend the state replace much of the hodgepodge of categorical programs now serving ED students with one block grant. Specifically, we recommend consolidating all the state–funded academic achievement programs into an “Opportunity to Learn” (OTL) block grant. While such streamlining can occur in the near term, we also recommend the state continue to look for opportunities to further streamline the system over time. For example, we recommend placing the after school program into the OTL block grant, though such a change would require a ballot initiative. We also think other programs (such as those supporting English Learners, helping struggling students, or promoting school safety) could be candidates for inclusion in the OTL block grant. We believe such decisions could be informed by the study assessing the impact of relevant risk factors (described above). Nonetheless, even in the near term, the new OTL block grant recommended above would result in a much simpler system with much more flexibility for LEAs to tailor services to local needs.

Link Funding to Student Barriers. We also think the state’s funding system could better reflect differences in the cost of educating students who face different barriers to academic success. Specifically, we recommend OTL funding be distributed to LEAs using a weighted, per–pupil funding formula. Under the new system, a student with multiple risk factors would generate more funding than a student with only one risk factor. Similarly, a higher level of risk would generate more funding than a lower level of risk. For example, a school district might receive significantly less funding for a student who is an English Learner from an educated two–parent household living in a relatively safe suburb than a school district would receive for an English Learner student living in a dangerous neighborhood who has one parent absent and one parent with a low level of education. The results of the study described previously could be used to craft the new funding formulas.

Strengthen Accountability—Measuring Year–to–Year Learning Gains. To help focus efforts on improving the academic progress of ED students, we recommend the state’s assessment system be refined to better assess year–to–year learning gains. Although such a measure of learning gains would apply to all students, it is especially important for promoting accountability in serving ED students. This is because ED students often have fallen behind more than one grade level and the existing assessment system lacks the capability to assess their progress. For K–8 students, we recommend aligning CSTs such that individual year–to–year learning gains could be identified, without the need for any additional testing. We recommend the same endeavor be undertaken for certain high school assessments. At all grade spans, such measures of learning gains would allow LEAs achieving significant success with at–risk students to be more clearly distinguished from LEAs that largely fail to address the needs of their ED students.

Strengthen Accountability—Collect and Disseminate Data on Outcomes. For the OTL block grant, we further recommend linking funding to specific data and reporting requirements. Specifically, as a condition of receiving OTL funding, we recommend that LEAs report on the academic achievement of their at–risk population, as measured by multiple indicators, including attendance data, test scores, year–to–year learning gains, course completion rates, and graduation rates. In addition to requiring annual reporting on objective measures of progress, we recommend periodic, independent evaluations assessing how well stated objectives were being met at the local level. These evaluations could be particularly useful to school districts—helping them identify, share, and implement best practices. We also recommend that annual data on performance as well as the results of independent evaluations be made easily available to the public. This would improve transparency and promote stronger accountability at both the state and local levels.

Conclusion

The state’s current approach to supporting ED students does a poor job of distinguishing among California’s roughly three million ED students, identifying the major academic barriers they face, and providing funding linked to the cost of overcoming those barriers. To make matters worse, the existing system consists of a hodgepodge of disconnected programs that have yet to demonstrate positive results in improving the academic achievement of ED students.

To address these concerns, we recommend replacing the existing system with a new system centered around the root causes of poor academic performance. Importantly, we believe school districts should have much greater flexibility in responding to the academic barriers that are prevalent in their communities. Nonetheless, we think the state still has an important role in the improvement process—systematically assessing barriers to academic achievement, ensuring funding is distributed based on those barriers, strengthening accountability by measuring learning gains, and identifying and facilitating the sharing of best practices in supporting at–risk students. By consolidating existing programs and pooling existing funding, we believe all this can be done at no additional cost to the state.

|

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by

Stefanie Fricano and reviewed by Jennifer Kuhn. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan

office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as

an E-mail subscription service , are

available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925

L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page