January 14, 2009

2009–10 Budget Analysis Series

California’s Cash Flow Crisis

Summary

“Double Whammy” of Weak Revenues and Limited Credit Market Access Has Hurt the State’s Cash Position

In a typical year, after the Legislature and the Governor agree to a balanced annual budget, the state must borrow from available special funds balances and municipal bond investors to “smooth out” cash flow deficits, particularly during the early months of the fiscal year. In 2008–09, weakening revenues and limited access to the credit markets have reduced the state’s resources to address monthly cash flow deficits. As a result, the state’s “cash cushion”—its available liquidity to allow the General Fund to make all budgeted payments on time—is unacceptably low.

Absent Prompt Action by the Legislature, Delays in Some State Payments Are Likely

The State Controller is the official responsible for managing the state’s cash flows. Absent prompt action by the Legislature to begin addressing the state’s massive budget and cash flow crises, the state’s cash cushion is likely to be depleted in the coming weeks, and the Controller will be forced to delay certain budgeted payments, including some vendor payments and tax refunds.

Key Considerations for the Legislature and the Public

When Will the State “Run Out of Cash?” Strictly speaking, the state can never run out of cash because tax and other payments flow into state coffers every day. Instead, what may happen in the next few weeks is that available cash may no longer be sufficient to make all state payments that have been appropriated by the Legislature on a timely basis. The state would most likely reach this point—absent any corrective action by the Legislature or the Controller—in late February or early March 2009.

Which Payments Will Be Delayed in the Next Few Weeks? In the weeks before the state’s cash on hand reaches zero, the State Controller must start taking corrective action. Specifically, he must delay payments classified as lower–priority under the law. The Controller must do this to help ensure that the state can keep making payments deemed as higher–priority under the law. The Controller has broad discretion to determine which payments are “priority payments.” The state’s priority payments appear to include many related to schools, debt service, state employee payroll and benefits, and Medi–Cal. Other categories of payments, such as tax refunds, student aid grants, and payments to local governments and vendors, may be delayed in the coming weeks.

When Will State Funding for Infrastructure Projects Resume? A board consisting of the State Treasurer, the Controller, and the Director of Finance recently decided to stop a key source of initial funding for many infrastructure projects funded by state bonds. The state’s weak cash position and its current inability to access the bond markets for financing caused the board to take this step. Legislative action to address much or even most of the state’s colossal $40 billion budget gap will be necessary for the state to improve its cash position and regain access to the bond markets. This would allow state officials to resume funding for the important public works projects.

Is Bankruptcy an Option for the State? When individuals, companies, and local governments are unable to pay their bills, filing for protection under the U.S. Bankruptcy Code is an option that allows them to renegotiate or restructure their financial obligations. States, however, are believed to be ineligible for bankruptcy protection.

Balancing the Budget Is the Best Way to Address the Cash Crisis

Balancing the budget—by increasing state revenues and decreasing expenditures—is the most important way that the Legislature can shorten the duration and severity of the state’s cash flow crisis. Absent prompt action to begin addressing the state’s colossal budget gap and other measures discussed in this report specifically to help the state’s cash flows, state operations and payments will have to be delayed more and more over time. In the event that the Legislature and the Governor are unable to reach agreement to balance the budget by the summer of 2009, major categories of services and payments funded by the state may grind to a halt. This could seriously erode the confidence of the public—and investors—in our state government. To avoid this, it is urgent that the Legislature and the Governor act immediately to address the budgetary and cash crises that have put the state on the edge of fiscal disaster.

Distinguishing Between the Budget Situation and the Cash Situation

The state’s budget situation, which is the primary fiscal focus of the Legislature each year, can be distinguished from the state’s cash situation, which only recently has become an equally important concern. It is important to understand how the two situations are different and how they relate to one another.

The Annual Budget and the Annual State Cash Flow Plan

Annual Requirement to Enact a Balanced State Budget. Unlike the federal government, the state may not enact an annual budget that is out of balance. There are practical reasons for this—principally, that the state’s ability to borrow is more limited than that of the U.S. government and the state cannot print currency. Moreover, Proposition 58 amended the State Constitution in 2004 to require the Legislature to enact a balanced budget each year in which estimated resources for the year meet or exceed estimated expenditures. Proposition 58 also authorizes the Governor to declare a fiscal emergency in the middle of a fiscal year and propose corrective measures to the Legislature if it is determined that the state faces substantial revenue shortfalls or spending increases.

Annual State Cash Flow Plan. State law requires the Governor to submit to the Legislature a statement of estimated monthly cash flows each year. Typically, after the Legislature passes the budget act, an updated General Fund cash flow estimate is prepared principally by the Department of Finance (DOF) in consultation with the Controller and the Treasurer. This cash flow plan details how the state will meet its budgeted General Fund expenditures (also known as disbursements) in each month of the year. As described in more detail below, the cash flow plan must use various techniques, such as borrowing on a temporary basis from special funds or bond market investors, to deal with the fact that disbursements typically are higher than revenues (also known as receipts) during several months of the year. This process of managing cash flows during weaker revenue periods—through borrowing from available sources during leaner periods of the year—is typical in both the public and private sectors. The intent of the process is to ensure that budgeted obligations can be paid on time in each month of the fiscal year.

Differences and Similarities Between The Budget and Cash Flow Situations

Differences Between the Budget and Cash Flow Situations. When the Legislature balances the General Fund budget each year, it must enact measures to ensure that General Fund revenues and expenditures match over the course of the entire year. The cash flow plan, by contrast, focuses on the state meeting its payment obligations in each individual month of the fiscal year.

How Do the Budget and Cash Flow Situations Relate to Each Other? The state’s annual budget and cash flow plans are distinct documents, but they relate closely to each other. In particular, as the state’s budget situation improves (with stronger tax collections, smaller expenditures, or larger reserves), its cash flow situation typically improves as well, resulting in the need for less borrowing from special funds or investors to smooth out monthly cash flows. On the other hand, when the state’s budget situation deteriorates (with weaker tax collections, larger expenditures, or smaller reserves), its cash flow situation generally deteriorates, requiring more borrowing from special funds or investors to smooth monthly cash flows. In the long run, the state’s cash flow and budget situations both are driven by the same fundamental fact—the need to balance revenues and expenditures. When the budget falls out of balance, therefore, it is inevitable that the state’s cash flow situation will be negatively affected. When the budget falls deeply out of balance in a relatively short period of time, as has occurred during the current fiscal year, state cash flows can prove insufficient to support the amounts of state payments previously appropriated by the Legislature.

How State Cash Flows Work in a Typical Fiscal Year

In this section, we discuss how the state’s General Fund cash flows are managed in a typical year. We use the 2007–08 cash flows as an example because they demonstrate how state cash flows work in a typical year—prior to the extreme cash flow distress that has emerged in the current 2008–09 fiscal year.

General Fund Receipts

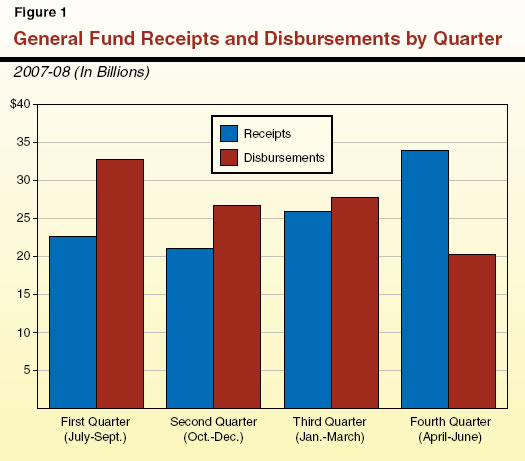

State Receives Much of Its Receipts in the Second Half of the Fiscal Year. The state’s fiscal year runs from July 1 to June 30. Figure 1 shows the quarter–by–quarter trend of General Fund receipts and disbursements during the 2007–08 fiscal year, which began on July 1, 2007, and ended on June 30, 2008. The timing of receipts is driven heavily by statutory and regulatory tax payment schedules. For example, the April 15 personal income tax filing deadline results in a surge of collections for this major revenue source during that month—resulting in April being the General Fund’s peak month for receipts. The April revenue surge typically means that the state also collects more of its receipts during the final quarter of the fiscal year than during any other part of the year. The state General Fund collected 33 percent of its receipts during the final three months of 2007–08.

General Fund Disbursements

State Makes Most of Its Payments During the First Half of the Fiscal Year. As with the timing of receipts, disbursements are made from the General Fund largely according to statutory and regulatory requirements. Figure 1 shows the quarter–by–quarter trend of General Fund disbursements during 2007–08. Nearly 60 percent of these disbursements were made during the first half of the fiscal year. Several types of expenditures are “front–loaded” toward the beginning of the fiscal year. In 2007–08, for example, about 55 percent of school payments were made between July and December.

Monthly Cash Flow Surpluses and Deficits

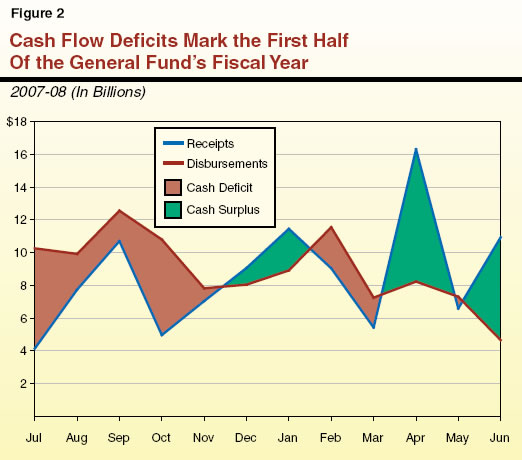

Cash Deficits Typically Materialize During the First Half of the Fiscal Year. The breakdown of General Fund disbursements by quarter can be contrasted with the breakdown of General Fund receipts by quarter in Figure 1. While the state received two–thirds of its 2007–08 General Fund receipts during the first three quarters of the fiscal year, it had already made over 80 percent of its disbursements during those same three quarters. This means that the state tends to have cash deficits during the first half of the fiscal year. Figure 2 shows the month–by–month breakdown of General Fund receipts and disbursements during 2007–08. When disbursements are greater than receipts, a cash flow deficit results. During 2007–08, the state experienced cash flow deficits for each of the first five months of the fiscal year. In the second half of the fiscal year, some months (especially February and March) saw cash flow deficits, while other months (particularly April, due to personal income tax payments) saw cash flow surpluses.

Short–Term Borrowing Is the State’s Main Tool to Address Cash Flow Deficits

Public and Private Entities Use Borrowing to Address Periodic Cash Deficits. Like many private businesses (and even individuals), the state and other public entities use borrowing to address cash flow deficits that occur during some parts of the year. Large banks and corporations, for instance, often issue commercial paper (a type of short–term financial instrument) to address periodic cash flow deficits. Smaller companies and individuals may use credit cards or lines of credit from financial institutions to meet cash flow needs from time to time. The state and other governmental entities also resort to short–term borrowing to meet cash flow needs—typically from two main sources:

- The governments’ own “borrowable funds” (known as “internal borrowing”).

- Municipal bond market investors (known as “external borrowing”).

Internally Borrowable Resources Are Mainly the State’s Special Funds. In addition to the state’s General Fund, there are about 600 special funds and other funds that are classified by the State Controller’s Office (SCO) as borrowable funds under current law. State law allows SCO to borrow from these funds on a temporary basis—repayable, in many cases, with interest—for cash flow purposes. The combined balances of these approximately 600 funds—including the state’s Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) and Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (reserve funds that are also available for cash flow borrowing)—vary from month to month. In 2007–08, the state’s internally borrowable funds typically had combined balances of between $13 billion and $16 billion. The balances of these funds generally are invested in the state’s Pooled Money Investment Account (PMIA). (See the nearby text box for background information about PMIA, the governing board of which voted recently to shut down funding for certain infrastructure projects due to the state’s cash flow crisis.) For each fund, if balances are borrowed for cash flow purposes, the General Fund pays back these temporary loans when it has funds available to do so or when the fund needs money to pay lawful appropriations. Therefore, the cash flow borrowing is designed never to affect a fund’s ability to pay for the programs it supports.

The State’s Pooled Money Investment Account (PMIA)

What Is the PMIA? The PMIA is the state’s short–term savings account. Moneys in the General Fund and state special funds are held in the PMIA and invested according to conservative guidelines. Some cities, counties, and other local entities also invest in the Local Agency Investment Fund (LAIF), which is a separate part of the PMIA. As of November 2008, the PMIA had a balance of $63 billion, of which $21 billion was in the LAIF. Who Administers the PMIA? The Investment Division of the State Treasurer’s Office manages the PMIA. The PMIA is governed by the Pooled Money Investment Board (PMIB), which is chaired by the Treasurer and also includes the Controller and the Director of Finance. In addition to the PMIB, the Local Investment Advisory Board—a five–member board also chaired by the Treasurer—provides oversight for the LAIF. Why Did the PMIB Cut Off Funding for Infrastructure Projects? The state’s weakening cash cushion has affected the balances of the state’s portion of the PMIA. Under state law, the PMIA provides short–term loans (known as “AB 55 loans”) to jump start projects funded by the future sale of state general obligation and lease–revenue bonds. The AB 55 loans are repaid from state bond or commercial paper issues. On December 17, 2008, the PMIB voted to begin the process of shutting down the AB 55 loan program, which may put a halt on hundreds of infrastructure projects. The deterioration of the state’s cash cushion in the PMIA and the state’s inability to access the bond or note markets—due in part to its budget and cash crises—were the reasons cited for the action. By addressing these budget and cash crises, the Legislature would lay the groundwork for the PMIB to restart the AB 55 loan program. |

External Borrowing From Investors Is Also a Key Cash Management Tool. Available balances in the state’s internally borrowable funds vary from month to month. These available balances are not always sufficient to allow the General Fund to address its monthly cash flow deficits. Accordingly, the state regularly pursues external borrowing from municipal bond investors. In a typical year, the state uses one or both of the short–term external cash borrowing instruments described in the text box on page CSH–10—revenue anticipation notes (RANs) or revenue anticipation warrants (RAWs). The most commonly used external borrowing instruments are RANs. The state has issued RANs in 19 of the last 20 fiscal years—that is, during good and bad budgetary situations. The RAWs, which span fiscal years and result in higher costs for the state, are less frequently used—typically during times of severe budgetary problems. The state has issued RAWs in only 6 of the last 20 fiscal years. Like most internal borrowing, RANs and RAWs must be repaid with interest by the General Fund in a relatively short period of time.

Revenue Anticipation Notes (RANs) and Revenue Anticipation Warrants (RAWs)

RANs. The state’s most commonly used device for external cash flow borrowing is the RAN—a low–cost, short–term financing tool. Typically issued early in the fiscal year, RANs must be repaid prior to the end of the fiscal year of issuance (usually in April, May, or June). The RANs are secured by money in the General Fund that is available after providing funds for the state’s “priority payments” (which are described later in this report). The State Treasurer’s Office works with financial firms to issue RANs almost every year. RAWs. The main reason the state sometimes resorts to RAWs is that they can be repaid in a subsequent fiscal year after their issuance. In fact, one California RAW issued in July 1994 matured 21 months later. The ability to have a later maturity date means the state can borrow for cash flow purposes even if the state’s cash outlook is challenging in the near term. Because of this longer maturity schedule and the fact that RAWs typically are issued when the state faces challenging budget times, they generally are more costly—with higher interest and other issuance costs—than RANs. The state’s $7 billion of RAWs in 1994, for example, resulted in interest and other issuance costs of over $400 million, and the $11 billion of RAWs in 2003 resulted in over $260 million of costs. The State Controller’s Office works with financial firms to issue RAWs. |

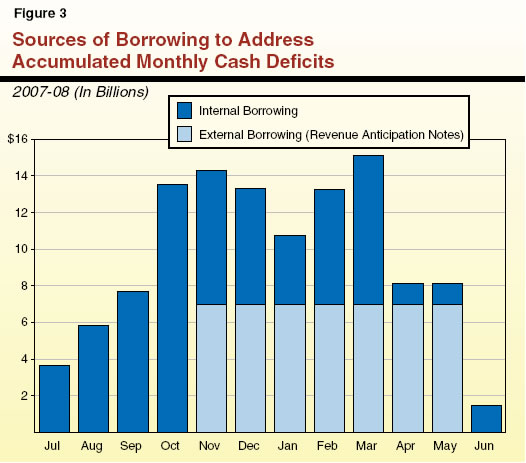

How Borrowing Allowed the State to Pay Bills on Time During 2007–08. As discussed above, the timing of General Fund receipts and disbursements means that the state experiences periodic monthly cash flow deficits, particularly during the first half of the fiscal year. Figure 3 shows the General Fund’s cash flow deficit as it accumulated through 2007–08 and the sources of internal and external cash flow borrowing that were used to address that deficit. The accumulated cash flow deficit grew steadily during the first few months of the fiscal year as General Fund disbursements outpaced receipts. By the end of October 2007, the accumulated cash flow deficit had consumed most of the available internally borrowable fund balances. As a result, $7 billion of RANs were issued to investors in November. The proceeds of the RANs allowed the General Fund to repay a portion of the borrowed special funds. The $7 billion of RANs were repaid with interest in June 2008.

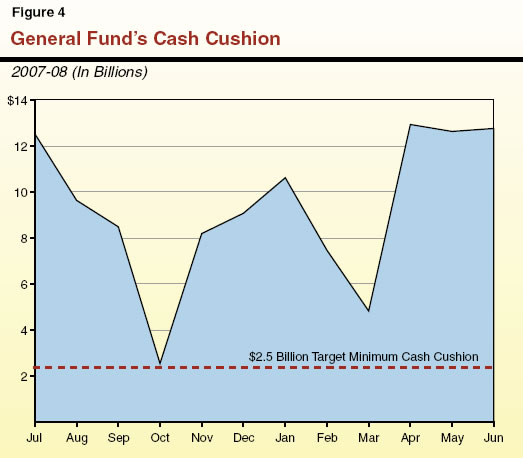

State Needs to Close Fiscal Year With Significant Cash Cushion. At the end of the 2007–08 fiscal year—as the result of the normal fourth–quarter surge of receipts—the state had a small accumulated cash deficit, as shown in Figure 3. The state generally needs to close the fiscal year on June 30 with its General Fund cash flow roughly in balance. This leaves the state’s borrowable funds largely untapped as a cash cushion that is available to cover the large cash flow deficits that emerge during the first half of the new fiscal year beginning on July 1. At any given point during the fiscal year, the state’s cash cushion consists of available borrowable resources not needed at that point in time to address the General Fund’s accumulated cash flow deficit. Figure 4 shows the amount of the state’s cash cushion at the end of each month during 2007–08. To ensure that there are enough funds on hand to address unexpected General Fund or special funds needs, SCO typically prefers to maintain a cash cushion of no less than $2.5 billion. In 2007–08, the end–of–the–month cash cushion never dipped below $2.5 billion.

Cash Flow Borrowing Is Different From “Budgetary Borrowing.” The types of internal and external cash flow borrowing described above are different from the multiyear borrowing of special funds that is sometimes authorized by the Legislature to help balance a fiscal year’s budget. The latter type of multiyear borrowing is known, along with other types of budget–balancing actions, as budgetary borrowing. Internal and external cash flow borrowing is short–term in nature and, except for certain RAWs, generally is repaid within one year. Budgetary borrowing, on the other hand, often is repaid over multiple years. For instance, the state currently has about $1.4 billion in outstanding budgetary borrowing loans from special funds that will not be repaid until 2010–11 or later. Budgetary borrowing provides resources that help balance the annual state budget; in other words, funds from budgetary borrowing often are counted as revenue for purposes of ensuring that annual budget revenues match annual expenditures. By contrast, proceeds of cash flow borrowing generally are not counted as a resource for purposes of balancing the annual budget. Instead, the proceeds of internal and external cash flow borrowing merely help SCO—the department responsible for paying the state’s bills—make payments on time throughout the fiscal year.

The 2008–09 Cash Flow Crisis

The state’s cash flows have deteriorated steadily—along with its budgetary situation and, particularly, state revenues—since the end of 2007. This means that the state’s cash cushion has weakened considerably during 2008–09. This section traces the history of the current state cash flow crisis and how 2008–09 state cash flows are much different from those in a typical fiscal year.

Legislative Actions Affecting Cash Management in 2008

The Legislature enacted several measures to address the declining cash flow situation during 2008. These measures (1) delayed certain state payments to later in the fiscal year in order to reduce monthly cash flow deficits and the amount of external borrowing and (2) made some state funds available for internal cash flow borrowing for the first time.

Delaying State Payments. When the Governor called a fiscal emergency special session of the Legislature in January 2008, he noted the state’s deteriorating cash situation and proposed to shift $4.7 billion of payments (to schools, social services programs, local governments, Medi–Cal providers, and others) from July and August of 2008 to later months of 2008–09. The goal of this package was to bolster the state’s cash flows prior to issuance of RANs during the fall of 2008. The Legislature adopted the proposal in February 2008 with some modifications, including making the payment deferrals effective for 2008–09 only (rather than ongoing as originally proposed). As the Legislature considered the 2008–09 budget during the spring after the special session, the administration submitted proposals to delay an additional $3.6 billion of payments to later in the fiscal year. The intent of these proposals was to reduce the size of the state’s RAN borrowing. The Legislature also passed these measures with some modifications as part of the 2008–09 budget plan. The adopted plan included a $3 billion shift in school funding from January through March to April through June. These changes were approved on a one–time basis for 2008–09. Additional, smaller changes in payment schedules affecting the University of California and other entities were approved on a permanent basis.

Increasing Internally Borrowable Resources. The budget plan also included legislation to reclassify 18 existing state funds as internally borrowable resources, an act that increased the state’s total borrowable resources by about $3.5 billion. In addition to the Legislature’s actions, SCO—using its existing administrative authority—reclassified other funds with combined balances of about $500 million to make them internally borrowable. In total, these actions added about $4 billion to the state’s cash cushion.

The Double Whammy: Weak Revenues And Credit Market Access Hurt The State’s Cash Cushion

Weak Revenues Have Placed Major Stress on State Cash Flows. The administration recently estimated that 2008–09 General Fund revenues would be $14.5 billion lower than assumed when the Legislature passed the 2008–09 Budget Act. These sharply lower revenue estimates correspond to the state’s declining economy and reflect broad–based weakness in personal income, sales, corporate, and other state taxes. Lowered revenue estimates translate into lower–than–expected levels of receipts to support General Fund cash needs. This is the key reason for the state’s current cash flow crisis.

State Officials Decide to Seek $7 Billion in External Cash Flow Borrowing. The state cash flow plan prepared by DOF in May 2008 estimated the state might need to access the credit markets and issue $10 billion of RANs during the first half of 2008–09. The actions of the Legislature (discussed above) to delay certain state payments and increase the state’s internally borrowable resources helped reduce the size of the needed RAN offering and its anticipated interest expenses. The Legislature and the Governor‘s delay in agreeing to a budget package until late September also meant that some anticipated payments during the first quarter of 2008–09 were delayed, and this reduced cash flow pressures during the first part of the fiscal year. Accordingly, soon after enactment of the budget, the Controller determined that the state needed a reduced amount of external cash flow borrowing—$7 billion—to meet its cash obligations on time through the end of 2008–09. The Treasurer and other state officials, who had already been preparing for months for the state’s cash flow borrowing, went to municipal bond market investors in earnest beginning in early October to attempt to issue $7 billion of RANs.

Financial Market Crisis Limits State’s Ability to Access Credit Markets. In October 2008, California had the misfortune of approaching investors to sell RANs at the moment of the worst worldwide financial crisis since the Great Depression. On September 15, 2008, Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. announced it was filing for bankruptcy protection—in part due to the firm’s exposure to weakened mortgage assets. On September 16, the Federal Reserve authorized an up to $85 billion loan to American International Group Inc., one of the world’s largest insurance companies, to prevent the company’s failure. In the ensuing days, as federal officials considered a proposed $700 billion stabilization package for the financial industry, equity markets declined worldwide, money markets experienced unprecedented tumult, and credit markets—including the municipal bond market—“froze,” meaning that the normal volume of bond and note transactions declined dramatically. For a number of days, the state’s prospects of achieving any significant credit market access were uncertain, and, as a result, the Governor wrote the Secretary of the Treasury on October 3 to alert him to the possibility that California might ask the federal government for “short–term financing” in the event that the RANs could not be issued. State officials also initiated an unusually broad marketing campaign—including radio advertisements featuring the Governor—to convince individual Californians to “invest in California” and purchase RANs through authorized brokerages. The response from these “retail investors” proved to be unexpectedly strong, offsetting very weak demand from large financial institutions and funds that usually purchase the state’s securities. On October 9, the Governor again wrote the Treasury Secretary—following final enactment of the federal financial market package—to express his optimism that no federal loans to the state would be required. During the week of October 13, the Treasurer’s Office successfully coordinated a sale of $5 billion of RANs—primarily to retail investors. The notes were sold with two maturity dates: $1.2 billion of RANs to mature on May 20, 2009, with a 3.75 percent yield, and $3.8 billion of notes to mature on June 22, 2009, with a 4.25 percent yield. While the RAN proceeds have been important in helping the General Fund meet its obligations to date during 2008–09, the $5 billion issued in October is $2 billion less than the Controller estimated was needed in early October—before the severity of the state’s budget situation became fully apparent.

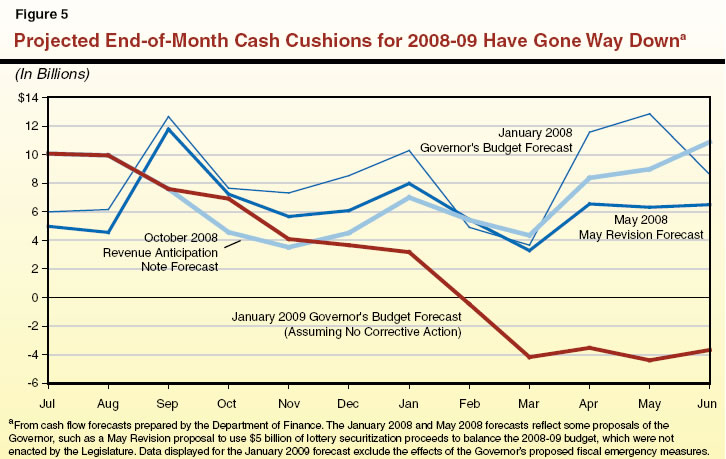

Cash Cushion Seriously Hurt by Weak Revenues and Credit Market Access. The twin blows to the state’s cash flows of (1) sharply weakened General Fund revenues and (2) limited credit market access have represented a double whammy for the state’s cash position in 2008–09. Figure 5 shows how the cash cushion forecasted by DOF for 2008–09 has weakened in recent months, with the most recent estimates being those presented this month with the Governor’s new budget proposal. While the Legislature’s actions to strengthen the cash cushion during the 2008 session helped the General Fund preserve a relatively healthy position during the first half of 2008–09, the cash cushion has weakened steadily throughout the fall and winter. Addressing the decline in the cash cushion already has been a focus of the Legislature and the Governor during successive special sessions since November.

Actions Will Occur to Cope With the Insufficient Cash Cushion

Cash Cushion Insufficient to Allow Normal Cash Flow During the Rest of 2008–09. The projected $3.2 billion cash cushion at the end of January 2009—as shown in Figure 5—is insufficient to ensure that the General Fund can continue normal cash flow operations with currently budgeted appropriations through the end of 2008–09. (In fact, the state entered January 2009 with $445 million less on hand than estimated in DOF’s most recent cash flow forecast, and this may mean that the cash cushion at the end of the month will be even less than estimated.) For comparison purposes, note the state’s $10.6 billion cash cushion at the end of January 2008, as shown in Figure 4. The General Fund needs a large cash cushion at the end of January because February and March typically have significant cash flow deficits. In some other years, the state might have been able to rely on accessing external borrowing through issuance of RANs or RAWs to supplement a weaker–than–expected January cash cushion. At the present time, however, credit markets—while recovered somewhat from their freeze last fall—remain weak, and investors are displaying a marked preference for highly creditworthy entities. California’s well–known financial troubles and the lack of consensus among elected leaders on balancing the state budget make it unlikely that the state can issue billions of dollars of RANs or RAWs to add to the cash cushion right now.

Absent Corrective Action, Cash Cushion Will Be Depleted in February 2009. Strictly speaking, the state can never “run out” of cash because tax and other payments flow into state coffers every day. As displayed in Figure 5, however, the General Fund’s cash cushion is projected to be entirely depleted sometime during February 2009—ending the month with a $500 million deficit—without prompt corrective action. Absent corrective action, monthly General Fund cash flow deficits in February 2009 would likely continue into March 2009. In total, through the end of March 2009, the cash deficit could rise to $4.2 billion. The state does not have the practical or legal ability to spend amounts in excess of its cash on hand at any given time. This means that corrective action to address the February and March cash flow shortfalls will occur. Such corrective action could be achieved by the Legislature (which can increase revenues, decrease expenditures, expand the state’s list of internally borrowable funds, or delay budgeted payments) or the Controller (who, as discussed below, has the authority to delay certain state payments). In the absence of agreement between the Legislature and the Governor to promptly address the projected cash flow deficit, the Controller must take action to determine which state payments his office will make on time and which payments will be delayed.

What Will the Controller Do?

Controller Must Focus on Making Priority Payments

Controller Has the Ability to Delay Payments With a Lower Legal Priority. The Controller—the official responsible for paying the state’s bills—has broad constitutional and statutory powers to manage state cash flows. In particular, state law—as well as contracts and disclosures made to the state’s bond and note investors—establishes that certain state obligations are priority payments. Priority payments are those that have a higher legal claim on state funds than other, non–priority payments. Accordingly, when the state’s cash resources are insufficient to meet all budgeted obligations, the Controller has the power and responsibility to make priority payments before making non–priority payments.

What Are the State’s Priority Payments? The law about which payments are priority and which are non–priority is murky. In large part, this is because the state has never experienced a prolonged period of extreme cash flow stress, which might have resulted in these questions being answered more definitively by elected officials and the courts. The clearest statements about which obligations are believed to be priority payments are those listed in the state’s RAN offering documents. The RAN offering documents list the state’s priority payments as follows:

- Payments, as and when due, to support public schools and public higher education system (as provided in Section 8 of Article XVI of the State Constitution).

- Principal and interest payments on the state’s general obligation bonds and general obligation commercial paper notes.

- Repayments from the General Fund to special and other funds for internal cash flow borrowing.

- Payment of state employees’ wages and benefits, including state payments to pension and other employee benefit trust funds.

- State Medi–Cal claims.

- Payments on lease–revenue bonds.

- Any amounts required to be paid by the courts.

Determining which state payments fall into these broad categories is a challenging task, and should the state face a prolonged period of cash flow stress, litigation likely would result in the Controller’s priority payment requirements becoming much more specific. Nevertheless, absent additional statutory or court direction, the Controller has a broad ability to determine which payments have legal priority. The Controller then has the duty during a period of severe cash flow distress to make those priority payments first, while delaying payments that have a lower legal priority.

Controller Has Various Options to Delay Non–Priority Payments

The Controller has several ways that he can delay non–priority payments in order to ensure that priority payments are made on time.

Registered Warrants Were Developed During the Depression to Delay Payments. One of the key tools that the Controller has to delay non–priority payments was developed by the Legislature in the depths of the Depression. In 1933, the Legislature anticipated that the General Fund might be exhausted before the end of the 1933–35 budget biennium. Legislation was enacted to provide that SCO could issue registered warrants when the state was presented with valid claims unable to be paid “for want of funds.” The registered warrants—now often referred to as IOUs—could bear interest of 5 percent per year. While the Treasurer challenged the constitutionality of the practice, the California Supreme Court upheld the registered warrant law as a valid use of the Legislature’s authority to appropriate state moneys, writing that “it is well settled in this state that revenues may be appropriated in anticipation of their receipt just as effectually as when such revenues are physically in the treasury.” The court further found that the IOUs did not run afoul of the Constitution’s debt limitation clauses. Accordingly, under the current version of the registered warrant statutes, the Controller may issue IOUs that bear interest of up to 5 percent per year, as determined by the PMIB. The law also allows the state to set a specific maturity date in the future when the IOUs may be redeemed. By issuing IOUs, SCO can delay making payments until the time when the IOUs are able to be redeemed from available General Fund resources. The state issued IOUs during the Depression and also during a budget impasse for two months in 1992, when numerous banks cashed IOUs that the state used to cover state tax refunds, vendor payments, and some other expenses.

Controller Can Also Simply Not Pay Some State Bills. Another option for the Controller to delay non–priority payments is simply not to pay certain bills when they are presented to his office. Instead, SCO can wait to pay the bills until the General Fund has available resources to do so at a later date. This is somewhat similar to what SCO does in a year with a prolonged budget impasse, when certain state payments are not made until a budget is enacted. This type of cash management can result in the state incurring additional costs or penalties, which are akin to the interest payments the state must pay when it issues IOUs. For example, the state’s Prompt Payment Act establishes penalties for the state when valid invoices from certain vendors are not paid within 45 days from receipt.

Bankruptcy Protection Is Not an Option to Delay Payments. While the Controller has several options to delay non–priority payments, the state does not have the option of seeking bankruptcy protection, as individuals, businesses, and local governments might if they were unable to pay bills on time. Local governments—such as the City of Vallejo—apply for the ability to restructure their obligations under Chapter 9 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code. Chapter 9, it is generally believed, does not afford states an ability to file for bankruptcy protection.

Controller Has Indicated IOUs May Be Issued Beginning in February 2009

What the Controller Has Indicated He Will Do. On December 30, 2008, the Controller released a statement indicating that, without budget solutions from the Legislature and the Governor, SCO would “have no choice but to pursue payment deferrals or the issuance of registered warrants…as early as February 1.” The Controller stated that IOUs may have to be issued in lieu of salaries and per diem payments to legislators, state elected officers, judges, and their appointed staff (all totaling about 1,700), as well as tax refunds owed to individuals and businesses. In a letter to state agencies the same day, the Controller stated that the purpose of issuing the IOUs was “to ensure that the state can meet its obligations to schools, debt service, and others entitled to payment under the State Constitution, federal law or court order.” With the letter, the SCO provided to departments and the Legislature a list of expenses currently paid through regular electronic funds transfers (EFTs) that the SCO said could be affected in the event registered warrants are issued. The list of EFT payees that SCO asked departments to prepare to transition to registered warrants is displayed in Figure 6. These payments include personal income tax refunds and California Student Aid Commission (CSAC) grants, including, potentially, Cal Grants.

SCO Expected to Provide More Detail on Its Plans Soon. The SCO’s December 30 letter indicated the possibility that the payments in Figure 6, among others, could be subject to issuance of registered warrants or payment delays. We understand that SCO soon will release more information on its plans. The Controller’s plans probably will change and evolve over time if the cash crisis persists. The longer the crisis persists, the longer the list of affected programs and payees may become.

Figure 6

List of Programs to Be Converted From Electronic Funds Transfers to Prepare for Possible Registered Warrants |

Administering Agency or

Department |

Program |

Assembly |

Payroll and Legislators' Per Diem Payments |

California Student Aid Commission |

Student Aid Grants |

Health Care Services |

Medi-Cal (Fund 0001 Claims and Abortion Claims) |

Franchise Tax Board |

Personal Income Tax Refunds |

Franchise Tax Board |

Bank and Corporate Tax Refunds |

Judicial Council |

Court-Appointed Counsel (Appellate and

Supreme Courts) |

Legislative Analyst's Office |

Payroll |

Senate |

Payroll and Legislators' Per Diem Payments |

State Controller's Office |

Citizens Option for Public Safety (COPS)

Apportionments |

State Controller's Office |

Homeowners' Exemption Apportionments |

State Controller's Office |

Williamson Act Apportionments |

State Controller's Office |

Trial Court Trust Fund Apportionments |

Legislature’s Options for Addressing the Cash Flow Crisis

The Legislature can avert the issuance of IOUs and the delay of certain state payments by the Controller only by taking substantial budget–balancing and cash management actions almost immediately. Even if the Legislature is unable to avert the delay of some state payments by SCO in the coming weeks, it has the power to shorten the duration and severity of the state’s cash flow crisis by acting soon to address the state’s huge fiscal problem.

Balancing the Budget Is Key to Addressing the Crisis

Increasing Revenues and Cutting Spending Key to Fixing Both the Budget and Cash. As we discussed at the beginning of this report, the state’s budget and cash flow situations are related. The Legislature must address a General Fund budget gap over the next 18 months that was recently estimated by the administration to total $40 billion. By increasing revenues and reducing expenditures, the Legislature can not only balance the 2009–10 budget, but also dramatically improve the cash situation by reducing the General Fund’s monthly cash flow deficits. The sooner that the Legislature enacts budget solutions, the sooner that these solutions can benefit the state’s cash situation.

Recommend Passing Measures to Increase Borrowable Resources

And Delay Some Payments

Administration Has Proposed Another Significant Package of Cash Flow Measures. In its special session and January 2009 budget proposals, the administration has proposed another series of measures intended to relieve state cash flow pressures and expand the General Fund’s weakened cash cushion.

Recommend Approving Expansion of Internally Borrowable Resources. Proposed trailer bill language would authorize internal borrowing from several additional state funds, and DOF estimates these funds would add about $2 billion to the cash cushion. Borrowing from these funds would occur in a similar fashion to the borrowing that already occurs from the 600 internally borrowable state funds discussed earlier in this report. We recommend that the Legislature approve this administration proposal.

Recommend Approving at Least Some Payment Deferrals on One–Time Basis. The Governor also submitted with his 2009–10 budget package a proposal to delay by a few months several categories of payments to schools, local governments, regional centers, and others (in addition to the $2.8 billion school funding deferral proposed to help balance the budget). These proposed payment deferrals are listed in Figure 7. Some of the payment deferrals, such as a two–month or three–month delay in some school apportionments now scheduled to be made in July and August, are similar to proposals enacted by the Legislature on a one–time basis in 2008. The payment deferrals could add about $1 billion to the state’s cash cushion during the last four months of 2008–09 and expand the cash cushion by $3 billion to $5 billion above what it would be under current law in July, August, and September of 2009. Each one of these proposed deferrals could result in difficulties for the entities whose payments would be delayed. In considering the proposals, the Legislature may wish to explore with the affected entities whether any measures could be enacted that would lessen the impact of the payment deferrals without additional costs to the state. We recommend that the Legislature approve on a one–time basis at least some of the proposed changes, as it did in 2008 for several groups of payments. Given current projections for a slow economic recovery and the state’s ongoing structural budget problems, it is likely, if the Legislature approves these deferrals on a one–time basis, that the administration will propose these payment delays again in 2010.

Figure 7

Additional Payment Deferrals Proposed by the Governor |

|

|

K-14 Education |

Defer $2.7 billion of payments to schools from July and August 2009 to October 2009. |

Transportation |

Defer transfers of $700 million of gas tax revenues to counties and cities for local street and road projects spread over several months beginning in February 2009. |

Defer $270 million of Proposition 42 transportation payments from April and June 2009 to October 2009. |

Medi-Cal |

|

Defer $874 million of various Medi-Cal payments from March 2009 to April 2009. |

Payments to Counties |

Defer $1.8 billion of various social services payments to counties spread across several months beginning in February 2009. Payments would be delayed until September 2009. |

Defer $92 million of mental health cash advances to counties from

July 2009 to September 2009. |

Defer $85 million of reimbursement payments to counties for the February 2008 election beginning in January 2009 to June 2009. (We understand that these payments have already been made to counties.) |

Developmental Services |

Defer $400 million of payments for regional centers from July and

August 2009 to September 2009. |

Payments to Health Plans for State Retiree Health Benefits |

Defer $194 million of payments for state retiree health benefits from March and April 2009 to May 2009. |

Mandates |

|

Defer $142 million of local mandate reimbursements from August 2009 to October 2009. |

Legislation to Facilitate RAW Issuance May Be Needed

Governor’s Proposed RAW Is Central for Both His Budget and Cash Flow Plans. In the first report in the 2009–10 Budget Analysis Series: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, we noted our concerns with the Governor’s use of about $5 billion of proceeds from RAWs to balance his budget plan. We acknowledge, however, that regardless of whether RAW proceeds are used to balance the annual budget, a RAW may need to be issued for General Fund cash flow purposes before or during 2009–10. In its summary of the Governor’s 2009–10 budget proposal, the administration opined that in order for a successful RAW issuance to proceed, three conditions would have to be met:

- A sustainable, balanced state budget.

- A plausible plan for repaying RAWs in a subsequent fiscal year.

- Enactment of legislation to protect RAW holders, including a “trigger” that automatically increases taxes or cuts programs if needed to ensure timely repayment of the RAWs.

The administration is correct that investors will need to be assured that the state has a viable budget plan in order to issue RAWs, RANs, or other debt instruments. In the past, enactment of trigger legislation has facilitated the state’s issuance of RAWs. Specifically, Chapter 135, Statutes of 1994 (SB 1230, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), helped state officials sell a 1994 series of RAWs to investors. Chapter 135 required the state to reduce most categories of expenditures if cash flow projections showed that timely payment of the RAWs was threatened. Given the need to preserve the Legislature’s constitutional prerogatives over the state budget, we are reluctant to recommend passage of such trigger legislation. We concede, however, that, given the current environment in the financial markets and investors’ shaken confidence in California’s credit quality, such legislation may be necessary to market RAWs and sustain a normal cash cushion for the General Fund during 2009–10. When the administration submits any proposed trigger legislation, we will review it and provide recommendations for any modifications to the Legislature.

Few Good Options to Control Higher Costs Once Cash Cushion Is Depleted

IOUs and Payment Delays Mean Higher State Costs. The state may experience increased costs—which are not reflected in the 2008–09 budget or the Governor’s proposed 2009–10 budget plan—beginning in 2008–09 if registered warrants or other payment delays are required as the state’s cash cushion is depleted. This is because registered warrants must be paid along with interest to the person or entity whose payment was delayed. In addition, the Prompt Payment Act and other laws require payment of interests or penalties in some cases of late state payments. It is virtually impossible to estimate the total amount of these higher costs in advance. In general, the longer and the more severe the state’s cash crisis, the more the state will be exposed to these types of payments.

Reducing Registered Warrants’ Maximum Interest Rate Would Be Problematic. Section 17222 of the Government Code provides that the PMIB may set the interest rate paid by the state on registered warrants at up to 5 percent per year. One option for the Legislature to reduce the costs of state payment delays would be to reduce this maximum interest rate. This, however, would be problematic. A key purpose of the registered warrant law is that the IOUs be negotiable instruments. This means that registered warrants can be traded in a fashion somewhat similar to the state’s debt securities. This, in turn, increases the probability that banks will cash the IOUs, as many did in 1992. Given the state’s weakened credit condition, financial institutions will need to be able to earn an appropriate return in order to feel comfortable cashing these investments for their depositors and others. Therefore, lowering the maximum registered warrant interest rate may reduce the number of banks willing to cash the IOUs.

Modifying or Suspending the Prompt Payment Act Also Would Be Problematic. The Prompt Payment Act provides for financial penalties if the state fails to meet certain deadlines for making certain state payments, particularly those to vendors. Reducing these penalties, restricting the scope of payments covered by the act, or suspending or repealing the act altogether could reduce the costs of state payment delays. Such an approach, however, would invite litigation, as vendors have entered into business relationships with the state based on the assurances and protections provided by the Prompt Payment Act. Over the longer term, the state’s failure to live up to the requirements of the Prompt Payment Act may discourage some businesses from doing business with state departments or result in them demanding higher payments for services to compensate for the risk of not being paid in a timely manner.

Over Longer Term, Building State Reserves Would Strengthen The Cash Cushion

Legislature’s 2008 Budget Reform Package Seeks to Increase Reserves. The 2008–09 budget package included a measure to be submitted to voters to make changes to the state’s BSA reserve fund, which was created by Proposition 58 in 2004. As mentioned earlier in this report, the BSA is one of the state’s accounts that is borrowable for cash flow purposes. Under current law, an annual transfer equal to 3 percent of General Fund revenues is made into the BSA. One–half of the transfer is saved as a reserve, and the other one–half is used to make a supplemental payment to pay off outstanding deficit–financing bonds. The Governor can suspend the annual transfer in any year by issuing an executive order (as was the case this year and is proposed for 2009–10). The proposed ballot measure would increase funds in the BSA in a number of ways. First, the ability to suspend the annual transfer would be limited to those years in which prior–year General Fund spending (grown for inflation and population) exceeded estimated General Fund revenues. Second, unanticipated revenues exceeding the enacted budget’s estimate by more than 5 percent would be automatically transferred to the BSA. Third, the target cap on BSA funds would be raised from 5 percent to 12.5 percent of annual revenues. Finally, funds could be transferred out of the BSA only to (1) meet emergency costs or (2) increase General Fund revenues up to the level of prior–year General Fund spending (grown for inflation and population). In addition, if voters approve the measure, the Governor would gain new authority to reduce certain General Fund appropriations during a fiscal year. These measures, as well as actions taken each year by the Legislature during the budget process, to expand reserves would bolster the state’s cash cushion in the long run. Relying more on such internally borrowable resources to smooth monthly variations in cash flows would reduce the state’s dependence on the credit markets for external cash flow borrowing.

The Fiscal Disaster That Would Result From Prolonged Inaction

State Faces Fiscal Disaster if Cash and Budget Deficits Remain Unaddressed. As we noted in our Overview of the Governor’s Budget, it is urgent that the Legislature and Governor act immediately to address the budgetary and cash flow situations that have put the state on the edge of fiscal disaster. Given the recent inability of the Legislature and the Governor to reach agreement on budget–balancing actions, it is now quite likely that some state payments will have to be delayed by the Controller in February and March. Even if this occurs, the sooner the Legislature and Governor begin to act to address the state’s fiscal crisis, the less the duration and severity of the state’s cash crisis will be.

Outlook in the Event of Prolonged Inaction

During the Rest of 2008–09, Delays in Tax Refunds Could Affect Many Residents. If the Controller decides to delay payments or issue IOUs beginning in February, it appears likely that personal income tax refunds to millions of California households could be delayed significantly. This would reduce the ability of those residents to spend refunds in their local communities, thereby producing an added “drag” on an already struggling economy. Some businesses and local governments might experience delays in their state payments, thus reducing the strength of their own cash flows and potentially subjecting their employees to layoffs or reductions in work hours. Some CSAC student aid grants may be delayed. Some state employees might not be paid on time, and this could affect recruitment and retention, particularly if financial institutions reach the point when they are unwilling to provide those staff with temporary assistance or cash IOUs. Other programs, such as those listed in Figure 6, also could be affected.

Summer 2009 Promises to Be a “Cash Abyss” if Few Solutions Are Enacted. As discussed earlier in this report, the General Fund typically needs to close the fiscal year on June 30 with a substantial cash cushion and a limited accumulated cash flow deficit. If few or no solutions are enacted in the next few months—before the beginning of the 2009–10 fiscal year—the state may begin July with no cash cushion and hundreds of millions of dollars of IOUs and delayed claims. In that scenario, it seems unlikely that the state could access billions of dollars of external financing to supplement its cash cushion. If the summer progressed further with a prolonged budget impasse, the Controller could be forced to delay more and more non–priority payments. If the state proceeds further into this summer cash abyss, it is possible the Controller would need to start delaying even some priority payments in order to ensure that schools and debt service payments are made on time. In this scenario, tens of thousands of state workers could see their paychecks delayed. Many Medi–Cal services might cease. Repaying internal cash flow borrowing to special funds could be difficult, and this could cause departments funded by special funds to implement major reductions in their operations. Financial institutions’ willingness to cash IOUs for Californians could wane. Gradually, more and more of state government’s payments—as well as services provided both by the state and local governments—could grind to a halt.

Action Needed Now to Begin Addressing the Cash Flow and Budget Crises

Unfortunately, the worst–case scenario described above is a plausible outcome if the Legislature and the Governor are unable to begin reaching agreements very soon on tough, painful measures to begin addressing both the state’s estimated $40 billion budget gap and the cash flow crisis. The most important thing that the Legislature can do to ensure the state can pay its bills on time and access the credit markets is to address the colossal budget gap. Approving measures to increase the state’s cash cushion in the short term and facilitate external borrowing in 2009–10 also may be required. If the massive budget gap is not addressed promptly, the state’s insolvency may significantly erode for years to come the confidence of the public—as well as investors—in state government itself. The Legislature and Governor, therefore, must act immediately to address the fiscal crisis that has put our state on the edge of disaster.

|

Acknowledgments

This report was prepared by

Jason Dickerson and reviewed by

Michael Cohen. The Legislative Analyst's Office (LAO) is a nonpartisan

office which provides fiscal and policy information and advice to the Legislature. |

LAO Publications

To request publications call (916) 445-4656. This report and others, as well as

an E-mail subscription service , are

available on the LAO's Internet site at www.lao.ca.gov. The LAO is located at 925

L Street, Suite 1000, Sacramento, CA 95814.

|

Return to LAO Home Page