October 16, 2009

Workers’ Compensation: Recent Decisions Likely to Increase Benefits and Employer Costs

Executive Summary

California’s workers’ compensation system provides medical and monetary benefits to workers who have been injured on the job. In 2004, in response to rising system costs, the Legislature modified the manner in which a worker’s permanent disability (PD) was measured to promote its stated goals of “consistency, uniformity, and objectivity.” Under the new system, compensation for PD benefits fell for most workers. Injured workers challenged the new system for measuring PD, claiming that it did not fairly compensate them for their injuries.

In February 2009, the Workers’ Compensation Appeals Board (WCAB) determined that the system used to measure PD could be “rebutted” or challenged based on the evidence in particular cases. In September 2009, the WCAB revised portions of these decisions, but maintained its position that PD ratings can be rebutted. Our analysis indicates that the WCAB’s decisions could lead to (1) changes in PD ratings, (2) increased incentive for litigation, and (3) decreased uniformity in determining PD. Ultimately, these effects would likely lead to increased benefits for workers and higher costs for businesses and governments.

If the Legislature agrees with the board’s decisions, it could allow the cases to be resolved through the judicial process. However, if it does not agree with the board’s rulings, the Legislature could clarify statute to determine when and if the system for measuring PD can be rebutted and/or make direct changes in compensation for PD. Our analysis indicates that the latter approach would provide more uniformity and objectivity.

Introduction

What Is Workers’ Compensation?

Workers injured on the job have a legal right to receive workers’ compensation benefits. Those benefits include medical care, compensation for wages lost while recovering from an injury, and compensation for future earnings lost due to PD. The workers’ compensation system is a “no–fault” system, which means that an employee injured at work receives medical care and benefits regardless of who was at fault for the injury. Employers in the state of California are required to provide workers’ compensation benefits, and, in return, employees cannot sue employers for their job–related injuries. Although most employers purchase workers’ compensation insurance, some employers who meet certain financial requirements choose to self–insure. This means that they do not purchase workers’ compensation insurance and instead set aside reserves to cover their own workers compensation costs. Among the more than 17 million people employed in California in 2008, there were roughly 618,900 reported occupational injuries, illnesses, and deaths.

Workers’ Compensation Appeals Board. When an injured worker files a workers’ compensation claim for benefits, the insurance company that represents the employer reviews the claim and approves or denies coverage. If there is a dispute between the worker and the insurance company over such issues as monetary benefits or scope of medical treatment, either can bring the case before a workers’ compensation judge, who rules on the case. If either party disagrees with the judge’s decision, the parties can appeal to the WCAB. The WCAB is a seven–member judicial body whose commissioners are appointed by the Governor and confirmed by the Senate for six–year terms. Five of the members must be attorneys.

The WCAB is the court of appeal for all workers’ compensation claims in California. In addition to reviewing claims, it also establishes statewide policy for the operation of the workers’ compensation system by issuing “en banc” decisions, or decisions that are reviewed and made by the entire board. All of the state’s workers’ compensation judges are required to follow en banc decisions.

Role of the Insurance Commissioner and Rating Bureau. In California, the Insurance Commissioner monitors the premium rates that insurance companies charge employers for workers’ compensation insurance and issues an advisory benchmark rate. That rate is not binding and insurance companies may chose to set premium rates below or above the benchmark.

The Workers’ Compensation Insurance Rating Bureau (WCIRB) is an independent entity funded by insurance companies that collects data to measure the cost of workers’ compensation in California. The WCIRB issues a recommendation to the Insurance Commissioner on the rate at which the advisory benchmark should be set. The Commissioner may accept, reject, or modify the board’s recommendation.

Permanent Disability Awards for Disabled Employees

Workers who suffer a permanent disability are entitled to receive PD benefits. The amount of compensation that a worker receives is determined by measuring, or “rating,” the injured worker’s impairment. Those impairment ratings are then adjusted for age and occupational factors. The PD ratings can range from 0 percent, which signifies no impairment, to 100 percent, which signifies total disability. Ratings determine the amount of compensation an injured worker will receive. This system of determining an injured worker’s disability rating, and adjusting it up or down based on various factors, is known as the Permanent Disability Rating Schedule (PDRS).

Workers’ Compensation Reforms of 2004

Workers’ compensation premiums reached a peak in 2003, with California employers paying an average of $6.45 in workers’ compensation insurance premiums for every $100 of payroll, making the state the most expensive in the country for workers’ compensation insurance. To control costs, the Legislature passed a series of reforms, including Chapter 34, Statutes of 2004 (SB 899, Poochigian). Since 2004, workers’ compensation costs have declined by about 65 percent. In 2008, California employers paid an average of $2.25 in workers’ compensation insurance premiums for every $100 of payroll. Meanwhile, payments for PD benefits for injured workers have declined by an average of 40 percent.

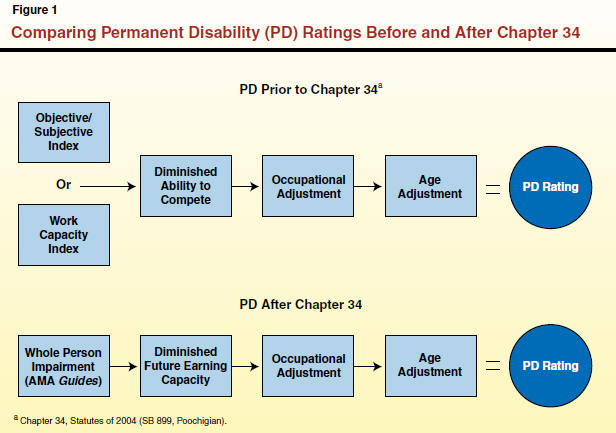

Chapter 34, in part, changed how the level of PD was determined for injured workers with the stated goal of promoting “consistency, uniformity, and objectivity.” As described below, and illustrated in Figure 1, the PDRS was significantly affected by Chapter 34.

PD Prior to Chapter 34. Prior to the 2004 reforms, California used two methods for determining an injured worker’s impairment rating—an “objective/subjective index” and a “work capacity index.” The objective/subjective index measured physical or functional losses (such as limited arm movement due to an injury) and unmeasurable factors (such as pain). The work capacity index considered a worker’s reduced ability to perform certain work functions (such as a reduced ability to lift heavy items). One or both indexes could be used in determining a PD impairment rating. When both measures were used, the index with the higher rating was applied. The rating was then adjusted for age, occupation, and the extent to which a worker’s ability to compete generally in the open labor market had been diminished.

Under the methods described above, impairment ratings for similar injuries could vary based on factors that could not be measured. A worker who reported “moderate” back pain, for example, would receive a higher impairment rating than a worker who reported “slight” back pain, although neither pain level could be objectively quantified.

PD After Chapter 34. Chapter 34 replaced the two indexes with the American Medical Association (AMA) Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment 5th Edition, which provide more standardized, evidence–based ratings. The AMA Guides measure a person’s loss of their ability to perform certain activities and assign a whole person impairment (WPI) rating accordingly. Each type of impairment, such as reduced range of arm motion, corresponds to a specific rating. The WPI rating is then adjusted using the PDRS to account for the injured worker’s age, occupation, and how their future earning capacity (FEC) was affected by their injury. Under this method, there is less reliance on factors that cannot be quantified objectively.

In addition, under the AMA Guides, the final rating takes into account the worker’s diminished FEC. The FEC adjustment is an upward adjustment made to the AMA rating based on the future earnings an injured worker will likely lose as a result of their injury. These adjustments range from 10 percent to 40 percent, based on historical averages of the proportional earnings loss associated with each injury, thereby increasing the benefits paid to injured workers. For example, an injured worker with a WPI rating of 20 percent under the AMA Guides may have an injury that receives a FEC adjustment of 10 percent. This FEC adjustment would increase the rating from 20 percent to 22 percent (0.20 percent x 1.10=0.22 percent).

Recent Decisions by the WCAB

In February 2009, the WCAB issued two en banc decisions that could significantly impact workers’ compensation in California. (Although the WCAB revised its decisions in September 2009, we anticipate that the potential effects on the workers’ compensation system remain significant.) Below, we present our understanding of these cases and the WCAB’s rationale for these rulings, based on our conversations with experts in this field.

February 2009: The Almaraz/Guzman Decision

The AMA Guides Held to Be Rebuttable. In two separate cases, injured workers appealed the PD ratings awarded to them by workers’ compensation judges, arguing that they should have received higher ratings than those granted under the AMA Guides. The WCAB, in its ruling, agreed that the AMA Guides could be superseded, or “rebutted,” if an impairment rating based on the Guides resulted in a PD award that was “inequitable, disproportionate, and not a fair and accurate measure of the employee’s permanent disability.” This is referred to later in this report as the Almaraz/Guzman February standard. The ruling also concluded that when an impairment using the AMA Guides has been rebutted, “medical opinions that are not based or are only partially based on the AMA Guides” may be considered. The WCAB did not, however, specify the standards by which a worker proves that a PD rating is inequitable, disproportionate, and not a fair and accurate measure. These two cases are collectively known as the Almaraz/Guzman decision.

February 2009: The Ogilvie Decision

The FEC Adjustment Held to Be Rebuttable. The Ogilvie decision involves an injured worker who appealed the FEC adjustment awarded by a workers’ compensation judge, arguing that it was lower than the potential earnings the worker would have received had she not been injured. The WCAB ruled that the FEC adjustment may be rebutted if there is evidence that the injured worker’s individual loss would differ from the average loss assumed under the PDRS for that particular injury. In contrast to their decision in Almaraz/Guzman, the WCAB provided more specific guidance in the Ogilvie ruling on the method to rebut the FEC adjustment.

September 2009: Almaraz/Guzman II and Ogilvie II

Technical Clarifications to Prior Rulings. In September 2009, the WCAB issued revised decisions for each of the cases discussed above. With respect to both cases, the WCAB clarified that, technically, it is the total PD rating which is deemed to be rebuttable, not the individual factors (such as the WPI or the FEC) used to calculate the total PD rating. However, this technical change may have little practical importance, because one way to rebut the total PD rating is to successfully challenge the validity of one of the individual factors. Additionally, the new board decisions further clarify the methods that may be used to challenge a PD rating. In general, we view these changes as technical rather than substantive.

Modifications to Prior Almaraz/Guzman Ruling. Beyond the technical clarifications described above, the WCAB significantly modified the way in which parties may rebut the PD ratings under the AMA Guides. In the February decision, the WCAB allowed parties to use evidence outside of the AMA Guides to establish PD ratings in order to address a PD rating which was inequitable, disproportionate, and not fair and accurate (the Almaraz/Guzman February standard). Under the revised decision, the board ruled that (1) parties may not go outside the AMA Guides to rebut PD ratings but (2) the Almaraz/Guzman February standard no longer applies (that is, a worker could challenge a rating for any reason, without having to show a certain threshold of “unfairness”). With regard to its impact on rebuttals, these two factors tend to work in opposite directions.

With respect to the revised ruling on the AMA Guides, physicians may use other parts of the AMA Guides that, based on their clinical judgment, are more reflective of the injured worker‘s impairment, even if those portions of the AMA Guides are not directly related to the worker’s specific injury. For example, a hairstylist who injured both arms due to overuse may have received a 2 percent impairment rating under a strict usage of the AMA Guides. A doctor, using his/her clinical judgment, may now determine under the new ruling that the injury is more like that of a vascular disease, resulting in a rating of 9 percent. Our analysis suggests that this aspect of the new decision has the effect of narrowing the original Alamaraz/Guzman decision, primarily because it prevents the physician from using anything other than the AMA Guides for rating purposes.

On the other hand, the elimination of the Almaraz/Guzman February standard could make it easier for injured workers to rebut their rating. As noted above, this is because workers could raise other reasons why their rating should be adjusted. We note, however, that even if the number of rebuttal attempts increase, a workers’ compensation judge must still decide whether enough evidence has been presented to successfully rebut the PD rating.

WCAB Rationale

The PDRS Is Prima Facie Evidence. In both the Almaraz/Guzman and Ogilvie decisions, the WCAB concluded that PD ratings are rebuttable because the Legislature did not specifically say in statute that they were not. Current law stipulates that the PDRS “shall be prima facie evidence of the percentage of permanent disability to be attributed to each injury covered by the schedule.” Prima facie evidence, as defined by the California Supreme Court, “is that which suffices for the proof of a particular fact, until contradicted and overcome by other evidence. It may, however, be contradicted and other evidence is always admissible for that purpose.” The WCAB ruled that the Legislature in effect allowed PD ratings to be rebutted by other evidence when it left intact statutory language indicating that the PDRS is prima facie evidence.

Workers’ Compensation Judges Ultimately Decide. The WCAB also noted in its rulings that the burden of rebutting a PD rating rests with the party wishing to dispute the rating. The workers’ compensation judge will ultimately decide if enough evidence (specifically, a preponderance of the evidence) has been presented to successfully rebut the PD rating in each specific case.

Status of Cases

As noted above, the board clarified both its decisions and modified its decision in Almaraz/ Guzman. Many observers believe that these cases will be appealed to the California Courts of Appeal, and possibly subsequently to the state Supreme Court.

We note that the WCAB did not determine if sufficient evidence had been presented to rebut the PD ratings in any of the cases above. Instead, the WCAB returned the cases to the original workers’ compensation judges for reconsideration consistent with the rulings.

Potential Effects of WCAB Decisions

Because these decisions were made recently, there is little data available to quantify the extent to which they will impact PD benefits for injured workers and the operation of the state’s workers’ compensation system. However, our analysis indicates that some significantly potential effects are possible, assuming that the cases cited above are not reversed or modified significantly by future court action.

Changes to Ratings and PD Benefits For Some Injured Employees

The WCAB’s ruling that PD ratings are rebuttable means that injured workers and insurance companies can appeal their PD ratings and potentially receive ratings that are either higher or lower than they would have received absent these decisions. Since benefits are determined by these ratings, workers who receive higher PD ratings will receive greater compensation for their injuries, while workers who receive lower ratings will receive less compensation. As discussed below in the fiscal effects section of this report, we believe that the most likely net effect is an increase in workers’ compensation costs.

Increased Incentive for Litigation

As a result of these decisions, injured workers and insurance companies have an increased incentive to challenge PD ratings. Cases that may have settled previously may now go to trial so that workers can appeal their ratings to obtain higher PD benefits. Also, insurance companies may pursue legal action in instances where they believe the AMA Guides or FEC adjustment components of the rating have been too generous.

Decreased Uniformity and Objectivity May Lead to Increased Variation

Under these new board rulings, the PD ratings would likely deviate from the established usage of the AMA Guides and FEC adjustment, introducing more subjectivity into the ratings. Similar workers with similar injuries could receive different PD benefits based on if, and how, they rebutted their ratings. Thus, this revised process for determining PD may affect the goal set forth in the original workers’ compensation reform legislation to determine PD with consistency, uniformity, and objectivity. However, our analysis indicates that there would still likely be more uniformity in the awarding of PD benefits than existed prior to Chapter 34. That is because injured workers and insurance companies would have to first provide evidence demonstrating why their particular injury would be a candidate for rebutting the schedule.

There are also some potential policy benefits to the new approach. Although these decisions may decrease uniformity and objectivity, they provide increased flexibility for injured workers or insurance companies to rebut PD ratings in cases when sufficient evidence is presented to demonstrate that a strict usage of the AMA Guides or FEC adjustment may not be appropriate.

Potential Fiscal Impacts of the Recent Rulings

Below, we discuss the potential fiscal impacts the recent WCAB rulings may have on California businesses and state government.

Private and Local Government Employers

In theory, the recent WCAB decisions may result in increased PD costs or savings for insurance companies and employers. If employees successfully rebut their PD ratings, insurance companies will have to pay larger PD awards. If insurance companies successfully rebut the ratings, they may pay smaller PD awards.

Although employers and insurance companies also have the right to rebut a PD rating, we believe that the WCAB decisions are more likely to result in a cost for employers. As we have noted, since the enactment of Chapter 34, benefits for injured employees have declined by about 40 percent. In order for an insurance company to successfully rebut the PD rating, it will have to provide enough evidence to demonstrate that a PD rating is too generous. This could be difficult in light of the sharp declines in PD ratings and benefits. Additionally, the threat of increased litigation may cause some insurance companies to settle before trial with a higher payout to workers than would have otherwise been the case prior to these decisions. This is because it may often be more costly to an insurer to litigate a case than to settle a case for a higher amount. Insurance companies will likely pass on those costs to California employers by increasing the premiums they charge for workers’ compensation insurance. The end result is likely to be higher net costs for insurers over time which would largely be passed along to employers—including some local government employers—in the form of higher premiums than they would otherwise be charged. Private and local government employers who are self–insured are also likely to experience increases in benefit costs.

State Government

Under current law, the state of California is not required to purchase workers’ compensation insurance and generally does not do so. Nonetheless, the state must pay successful claims for workers’ compensation benefits and the recent board decisions thus could result in unknown costs in PD benefits for successfully rebutted ratings. Although the magnitude of these costs are unknown at this time, for the same reasons noted above, it is likely that the decisions will result in higher net workers’ compensation costs for the state over time.

Estimated Net Impact on Workers’ Compensation Costs

The extent to which these decisions will be used to rebut PD ratings, and the costs associated with those rebuttals, are unknown at this early stage. In response to the February decisions, the WCIRB estimated that premium rates would have to be increased by 5.8 percent to cover the costs of increased PD benefits. (This would represent a total annual cost increase of over $800 million for all employers.) The Insurance Commissioner rejected the WCIRB’s estimate, not because he disagreed with the determination that there could be increased costs, but because he determined that it was premature to adjust premium rates to account for the board decisions, since they were under reconsideration by the WCAB at the time. The WCIRB has not issued a revised estimate of the potential costs in light of the September decisions. Nevertheless, we anticipate that private and public employer costs will generally increase as a result of increased PD ratings and benefits, although somewhat less than under the original rulings.

Potential Legislative Action

The WCAB ultimately concluded that because the Legislature did not change the section of the law that stated that the PDRS constituted prima facie evidence, it was the Legislature’s intent to make the PD ratings rebuttable. On the other hand, the Legislature also stated in the 2004 reform law that the PDRS should promote consistency, uniformity, and objectivity, raising a significant issue related to the Legislature’s actual intent. Below, we outline three potential approaches the Legislature could pursue to resolve this issue. We note that, in formulating its policy decision, the Legislature could implement these options individually or in combination.

Option One: Take No Action. One option is to do nothing. This would allow the court appeals process to run its course, during which time some of the likely effects noted above may begin to occur. This “wait and see” approach would allow for study of the magnitude of these effects. For the time being, PD benefits would be determined with greater variation than strictly adhering to the AMA Guides.

Option Two: Clarify the Statute Now. If the Legislature does not intend for the PD ratings to be rebuttable, it could clarify statute now to explicitly say so. In particular, it could remove the prima facie evidence clause from the workers’ compensation law. Removing the prima facie evidence clause would essentially return the workers’ compensation system to the way it operated before the board rulings and require that PD ratings adhere to the AMA Guides.

Alternatively, if the Legislature finds that the current schedule is too inflexible in certain situations, it could specify in statute (1) which portions of the PDRS are rebuttable, and (2) the criteria that a case needs to meet in order to be eligible for a potential rebuttal. For example, certain injuries are known to result in PD ratings of zero under the AMA Guides even though they result in some type of impairment. In specific situations such as this, the Legislature could specify that parties would be permitted to rebut their ratings. Specifying which portions of the PDRS are rebuttable would mean that only workers who meet certain specified criteria would be able to rebut their PD rating.

Option Three: Modify the PDRS. The lower level of PD benefits injured workers receive as a result of Chapter 34 is an important issue. Some observers may see these decisions as a way to correct for what they feel is inadequate compensation for injured workers. Because the ratings have been found to be rebuttable, benefits for injured workers who successfully rebut their ratings would increase. However, if the Legislature’s goal is to increase the relative generosity of PD benefits, a more direct way would be to change the amount of PD compensation rather than allowing PD ratings to be rebuttable. For example, the Legislature could clarify that PD ratings are not rebuttable but increase the compensation for injuries. This would increase benefits for injured workers, while maintaining a more predictable and consistent rating schedule.

Conclusion

As described in this report, the recent decisions made by the WCAB may significantly impact workers’ compensation PD determinations in California. Although the net effect on workers’ compensation costs cannot be known with certainty, the most likely impact is an increase in benefit payments and employer costs. To the extent the Legislature finds that the WCAB’s interpretation of current law is not in line with the original intent of the 2004 workers’ compensation reform package, it could take action to address the situation. In formulating its policy on this issue, the Legislature should consider the trade–offs between how its policies would affect benefits for injured workers versus the impact on private employers and state and local agency budgets.