Traditional State Fund Sources. State transportation programs have traditionally been funded on a pay–as–you–go basis from taxes and user fees. Two special funds—the State Highway Account (SHA) and Public Transportation Account (PTA)—have provided the majority of ongoing state funding for highways, local roads, and transit programs. The SHA is funded mainly by an 18 cent per gallon excise tax on gasoline and diesel fuel (referred to as the gas tax) and truck weight fees. These revenues fund mostly highways and road improvements. Revenues to the PTA come from a portion of the state sales tax on diesel fuel and gasoline, and are dedicated primarily to public transportation purposes. Additionally, since 2003, state gasoline sales tax revenues that previously were used for General Fund programs are to be used under Proposition 42 for highway improvements, transit and rail, and local streets and roads.

Other transportation–related programs, including traffic enforcement programs administered by the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) and the California Highway Patrol (CHP), also rely on dedicated revenue sources for their support. Specifically, both departments are funded mainly from fees imposed on drivers and vehicles.

Bonds. Since 2006, the state has increasingly used bond funds for various transportation programs. In 2006, voters passed Proposition 1B to provide about $20 billion in bond funding over multiple years for a variety of transportation improvement purposes. In November 2008, Proposition 1A was passed to provide $9.95 billion to develop a high–speed rail system and to improve other passenger rail systems in the state.

Governor Proposes Alternative Way to Fund Transportation. The budget proposes to significantly change (1) how the state generates revenues to fund transportation programs and (2) what programs would be funded with these revenues. Specifically, the Governor proposes to:

- Eliminate the state sales tax on fuel and make up most of the lost revenues with an increase in the per gallon gas tax. The increase would be 10.8 cents per gallon in 2010–11, and would be adjusted annually thereafter through 2019–20. The increase would be such that, in total, motorists would not pay more than they do now in gas and sales tax combined.

- Use the revenues from the gas tax increase to (1) pay debt service on transportation bonds and (2) fund state highways and local streets and roads.

- Eliminate on a permanent basis a dedicated source of state funding for transit operations and capital improvement.

For 2010–11, the Governor’s proposal would reduce fuel sales tax revenues by $2.8 billion, to be partially offset by about $1.9 billion in new gas tax revenues, which would be used as follows:

- $603 million for debt service on transportation bonds.

- $629 million for state highways.

- $629 million for local roads.

Legislative Alternative to Governor’s Proposal Under Consideration. As part of the special session to address the state’s fiscal condition, the Legislature has been considering an alternative to the Governor’s proposal to change transportation funding as outlined above. In general, the Legislature’s alternative would eliminate only the state gasoline sales tax, and replace the revenue from that source with revenues from an increase in the per gallon excise tax on gasoline beginning in 2010–11. The new revenues would be used to pay debt service on transportation bonds, to provide funding for state highway expansion and rehabilitation, and to fund local streets and roads. The Legislature’s alternative would not eliminate the state sales tax on diesel, thereby ensuring ongoing revenues for transit assistance and other public transportation activities.

At the time this analysis was prepared, the Legislature had not taken final action on its alternative.

Budget Proposals. In total, the Governor’s budget proposes $17.4 billion in expenditures for transportation programs in 2010–11. This amount includes about $12.6 billion in state and bond funds and $4.8 billion in federal funds. The total amount proposed is essentially the same as the estimated current–year expenditure level.

In addition to the alternative funding proposal discussed above, key proposals in the budget include:

- Authorizing $680 million in GARVEE bonds backed by future federal funds to pay for three highway rehabilitation projects.

- Using $583 million in Proposition 1A bonds to develop a high–speed rail system.

- Committing $3.45 billion in federal funds over multiple years to attract private investment in transportation projects.

- Increasing the number of CHP traffic officers by 180 positions.

- Using $350 million in Proposition 1B bonds for transit capital improvements, but providing no funding to assist transit operations.

Due to the state’s continued fiscal problems, the budget also proposes to use existing transportation funds to pay the General Fund for transportation debt service in the current and budget years. Specifically, the budget proposes a total of $311 million from the PTA and $72 million from the SHA to pay debt–service costs on various transportation bonds. Together with the funding ($603 million) from the new gas tax, the budget would provide about $1 billion for transportation debt service to help the General Fund.

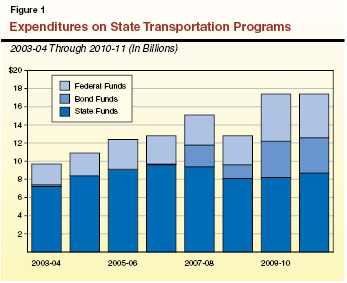

Overall Growth Trends. Figure 1 shows the expenditures for state transportation programs from state, bond, and federal funds from 2002–03 through 2010–11. The figure shows that total state transportation expenditures grew modestly through 2006–07. The figure also shows that since 2007–08, bond–funded transportation expenditures have increased significantly as the result of the passage of Proposition 1B in 2006 and Proposition 1A in 2008. In fact, bond expenditures are estimated to increase to about $4 billion annually in the current year, and remain at that increased level in the budget year, accounting for about 23 percent of all expenditures on state transportation programs.

While state transportation programs have relied more heavily on bond funding, Figure 1 shows that state funding from other non–bond sources has decreased since 2007–08. This is mainly due to the loan and redirection of various transportation funds to help the General Fund. For 2010–11, funding under the Governor’s budget proposal from various non–bond state funds for transportation would be at about the 2004–05 level. This funding level is primarily the result of two factors: (1) the proposed use of existing transportation funding to help the General Fund, and (2) the reduction in transportation revenues in the budget year under the Governor’s alternative funding proposal.

Figure 1 also shows a significant increase in the expenditure of federal funds for transportation for the current and budget years. The increase mainly reflects the availability of federal economic stimulus funds provided by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). Expenditures of federal funds are estimated to be at $5.2 billion in the current year. For 2010–11, they are projected at $4.8 billion, accounting for almost 28 percent of all expenditures on state transportation programs.

Figure 2 shows spending for the major transportation programs and departments from all fund sources, including state, bond, and federal funds, as well as reimbursements.

Figure 2

Transportation Budget Summary Selected Funding Sources

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

Actual

2008–09

|

Estimated

2009–10

|

Proposed

2010–11

|

Change From 2009–10

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

Department of Transportation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$1,333.1

|

$1,506 .0

|

$83.4

|

($1,422.3)

|

–94.5%

|

|

Other state funds

|

2,413.8

|

2,409.8

|

4,077.1

|

1,667.3

|

69.2

|

|

Federal funds

|

3,156.6

|

5,171.9

|

4,796.7

|

(375.2)

|

–7.3

|

|

Bond funds

|

1,118.4

|

3,057.5

|

3,432.6

|

375.1

|

12.3

|

|

Other

|

1,059.1

|

1,614.2

|

1,477.2

|

(137.0)

|

–8.5

|

|

Totals

|

$9,081.0

|

$13,759.1

|

$13,867.0

|

$107.9

|

0.8%

|

|

California Highway Patrol

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Motor Vehicle Account

|

$1,718.5

|

$1,723.4

|

$1,778.8

|

$55.4

|

3.2%

|

|

State Highway Account

|

60.8

|

58.9

|

59.5

|

$0.6

|

1.0

|

|

Other

|

110.9

|

138.6

|

139.1

|

$0.5

|

0.4

|

|

Totals

|

$1,890.2

|

$1,920.9

|

$1,977.4

|

$56.5

|

2.9%

|

|

Department of Motor Vehicles

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Motor Vehicle Account

|

$478.2

|

$501.9

|

$552.9

|

$51.0

|

10.2%

|

|

Vehicle License Fee Account

|

342.8

|

318.7

|

325.0

|

6.3

|

2.0

|

|

State Highway Account

|

49.4

|

49.0

|

55.8

|

6.8

|

13.9

|

|

Other

|

18.9

|

23.2

|

20.5

|

(2.7)

|

–11.6

|

|

Totals

|

$889.3

|

$892.8

|

$954.2

|

$61.4

|

6.9%

|

|

State Transit Assistance

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Public Transportation Account

|

$153.1

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—a

|

|

Bond funds

|

255.4

|

$514.3

|

$350.0

|

($164.3)

|

–31.9%

|

|

Totals

|

$408.5

|

$514.3

|

$350.0

|

($164.3)

|

–31.9%

|

|

High–Speed Rail Authority

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Public Transportation Account

|

$5.3

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

—a

|

|

Bond funds

|

37.3

|

$139.1

|

$583.2

|

$444.1

|

319.3%

|

|

Other

|

3.8

|

—

|

375.0

|

375.0

|

—a

|

|

Totals

|

$46.4

|

$139.1

|

$958.2

|

$819.1

|

588.9%

|

Caltrans. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $13.9 billion in 2010–11 for the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), about $108 million, or 0.8 percent, more than estimated current–year expenditures. As Figure 2 shows, expenditures from the General Fund are projected to decrease by $1.4 billion. This decrease reflects the Governor’s proposal to eliminate gasoline sales tax revenues for Proposition 42 funding in 2010–11. Expenditures from other state funds in 2010–11 would be higher, including $629 million more from the 10.8 cent per gallon gas tax increase proposed by the Governor.

CHP and DMV. Spending for CHP is proposed at about $2 billion—about 3 percent higher than the current–year estimated level. About 90 percent of all CHP expenditures would come from the Motor Vehicle Account (MVA), which generates its revenues primarily from driver license and vehicle registration fees. The increase includes first–year support for an additional 180 traffic officers.

For DMV, the budget proposes expenditures of $954 million, which is about 7 percent higher than the current–year estimated level. Support for the department would continue to come from MVA and vehicle license fee revenues (VLF). The VLFs are an in–lieu property tax, which DMV collects for local governments. For 2010–11, about 58 percent of the department’s support would come from MVA, and 34 percent would come from VLFs.

Transit Assistance. Up through 2008–09, the state provided funding assistance to transit systems for both operations and capital improvements. A portion of the PTA revenues was allocated annually to transit operators under the State Transit Assistance (STA) program. In the current year, due to the state’s fiscal condition, STA funding was suspended and PTA funds were redirected to help the General Fund. Additionally, Chapter 14, Statutes of 2009 (SBX3 7, Ducheny) was enacted to suspend the funding of the program through 2012–13.

Consistent with Chapter 14, the Governor’s budget proposes no funding for STA in 2010–11. Additionally, by eliminating the state sales tax on fuel, the Governor’s alternative transportation funding proposal would eliminate this revenue source for ongoing state funding for transit operations and capital improvements. Any future funding for transit capital would come from Proposition 1B, which provides $3.6 billion in bond funds for transit capital projects. For 2010–11, the budget proposes $350 million from the remaining Proposition 1B transit capital funding.

High–Speed Rail Authority. Of the amount authorized under Proposition 1A, $9 billion is specifically for the development and construction of a high–speed rail system. Under law, up to 10 percent of the bond funds may be used for noncapital costs, including planning, design, and engineering of the system. For 2010–11, the budget proposes $50.4 million in Proposition 1A funds for support activities, and $533 million for capital expenditures. The budget also anticipates another $375 million in federal funds to be available for the system’s development. (This amount of federally funded expenditure was included in the budget as a placeholder. Since the release of the Governor’s budget, the federal government has announced on January 28, 2010 its decision to allocate $2.25 billion in ARRA funds to California for the development and construction of the system.)

Due to the state’s fiscal condition in the past several years, funding that has traditionally been dedicated to transportation has been loaned to the General Fund or redirected to pay for programs that previously were funded from the General Fund.

Loans and Repayments. Since 2001–02, various amounts of transportation funds have been loaned to the General Fund. Figure 3 shows the amount of loans outstanding, and the amount of repayments due to transportation. As Figure 3 shows, three substantial loans require repayment. For 2010–11, the Governor proposes to delay the repayment owed to the Traffic Congestion Relief Fund from tribal gaming revenues, as has been done in 2008–09 and 2009–10. Rather, tribal gaming revenues of about $95 million would be retained in the General Fund. The General Fund, however, would repay (1) $83 million for a portion of the outstanding loan in Proposition 42 funding, as required by Proposition 1A (2008) and (2) $200 million to the SHA for a loan made in 2008–09.

Figure 3

Transportation Loans and Repaymentsa

(In Millions)

|

Year

|

To General Fundb From:

|

|

TCRF

|

Proposition 42

|

SHA

|

Other

|

|

Total Amount Borrowed

|

$1,383

|

$2,167

|

$200

|

$31

|

|

Balance Through 2008–09

|

849

|

584

|

200

|

31

|

|

2009–10

|

—

|

–83

|

135

|

—

|

|

2010–11

|

—d

|

–83

|

–200

|

–31

|

|

Beyond 2010–11

|

–849

|

–418

|

–135

|

—

|

Redirection and Broadened Use of Transportation Funds. In addition to the loan of transportation funds to the General Fund, the use of certain transportation revenues has been broadened in recent years to include purposes that had previously been paid from the General Fund. In particular, a portion of the revenues from sales tax on gasoline and diesel, which traditionally funded public transportation (and was deposited in the PTA) was used to pay transportation bond debt service and other services such as transportation for regional centers for the developmentally disabled.

In 2009, a state appeals court ruled that many of these uses were not allowable under statutory provisions adopted by voters. Specifically, the court held that about $1.2 billion in state transit funding could not be used as directed in the 2007–08 budget plan. As a consequence, the General Fund will have to repay this amount for public transportation purposes. The repayment terms are likely to be determined later in 2010.

One of the most important Caltrans activities is to develop and manage the construction of roughly $10 billion in highway projects. Caltrans’ Capital Outlay Support (COS) program is responsible for these activities. In the following analysis, we assess the way the department budgets and staffs the COS program.

Our review indicates that, overall, Caltrans provides insufficient information regarding the basis for workload and staffing for the COS program. In light of this problem, we evaluated the level of funding and staffing provided for the program using several different methods in order to build a comprehensive analysis of this situation. The cumulative evidence from our review shows that the program is overstaffed and lacks strong management. Specifically, we find the following:

- The workload that is assumed in the department’s annual COS budget request has not been justified.

- Although comparisons are difficult, Caltrans appears to be incurring significantly higher costs for COS activities than similar agencies.

- Comparisons of one Caltrans region to another suggest that COS staffing in at least some regions is excessive. There appears to be little relationship between the number of positions in a region and the size of its capital program.

- The imposition of furloughs on Caltrans COS staff appears to have had no identifiable impact on its productivity, further suggesting that the department is over–staffed for these activities

- A review of a sample of Caltrans projects showed that its COS costs regularly exceeded the norm, often by a considerable margin.

- Caltrans lacks systems and processes to manage and control COS costs.

These findings indicate that Caltrans has provided insufficient oversight of its COS resources. Accordingly, in our analysis below, we offer several recommendations to improve the management of the program, enhance legislative oversight, and bring staffing in line with the actual workload for this important function.

COS is the Work Necessary to Develop, Manage, and Oversee Projects. The COS program provides the support needed to deliver highway capital projects. Work conducted in the program includes completing environmental reviews, designing and engineering projects, acquiring rights of way, and managing and overseeing construction. The department accomplishes most of these activities with state staff, with a relatively small proportion of all work being done though contract resources. Figure 4 lists the major COS activities performed by Caltrans.

Figure 4

Capital Outlay Support (COS) Activities

|

|

|

Direct Project Work

|

|

Environmental Review. Each project is reviewed to determine its impact to the environment. This process includes the preparation of environmental documents, and the completion of studies, such as endangered species studies or archeological studies. Environmental work also includes identifying mitigation measures and obtaining permits.

|

|

Right–of–Way Support. Right of way is the land on which a project is built. Support for this portion of a project includes activities such as acquisition of property or easements, and working with other affected property owners.

|

|

Project Design and Engineering. Each project must be designed and engineered before it can be constructed. This includes activities such as preparing plans and project specifications, and developing the project’s final design, including estimates of the amounts of materials to be used and detailed plans for how the project is to be built.

|

|

Construction Oversight. Caltrans manages and oversees the construction of projects on the state’s highways by contractors. This includes activities such as documenting the number of contract workers on site, testingmaterials used in the project, and working with the contractor when changes or problems arise.

|

|

Indirect Project Work

|

|

Headquarters Program Management. Caltrans has a team of staff in headquarters who manage and oversee the COS program on a statewide basis. Program managers are responsible for establishing the overall COS budget, monitoring the use of resources by districts, and ensuring that the outcomes and goals of the program are achieved statewide.

|

|

Office of the Chief Engineer. This office, at Caltrans headquarters, is responsible for reviewing and signing off on certain work performed by district staff, as well as guiding the policies and standards used for the design and construction of highways.

|

As shown in the figure, so–called direct and indirect support activities must be performed for each project. Direct costs, which include mainly costs for engineering staff who work on specific projects, account for 78 percent of Caltrans’ total COS budget. The other 22 percent is for indirect costs, such as program–wide technical support that is not tied to specific projects, overall COS program management, certain engineering functions and oversight performed by Caltrans headquarters, and administrative overhead. Because direct support comprises the majority of the cost of the COS program, our review focuses mainly on these activities and their associated costs.

A $2 Billion Program. The COS program is the largest program within Caltrans in terms of staffing. The 2009–10 budget includes about $1.6 billion to support about 12,000 personnel–year equivalents (PYEs) of staffing and contract resources in the program. (Each PYE represents the equivalent of one staff member or contract resource working fulltime for a year.) The proposed 2010–11 January budget requests about $2 billion for COS, including $1.5 billion for Caltrans staff to perform direct and indirect project work, and $272 million for contract resources. The budget also includes about $250 million for Caltrans’ administrative overhead for the program. As has typically been done in past years, the request will be updated as part of the Governor’s May Revision, when the department expects to have more up–to–date information about the project work it will need to perform in the budget year.

Budget Request Not Justified With Workload. Caltrans submits a COS budget request each year that is supposed to be zero–based. That is, the request is supposed to fluctuate year to year based on the workload necessary to deliver transportation projects. Workload should be determined in accordance with various milestones set up to ensure projects in the State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP), State Highway Operation and Protection Program (SHOPP), and other programs are constructed as scheduled. Caltrans staff, together with contracted resources, work on various phases of a couple of thousand projects in any given year so that they will be ready for construction by the scheduled time.

However, our review of Caltrans’ COS budget for direct project work for recent years (2007–08, 2008–09, and 2009–10) indicates that the requests for COS funding and staffing lack sufficient workload justification. Specifically, the department has not been able to identify the work that needs to be done for each particular project, nor has it provided a summary of work programwide.

For instance, in 2009–10, the department‘s COS budget request was accompanied by a Caltrans work plan. This work plan was essentially a list of projects and the amount of resources to be allocated to each project. The plan, however, does not contain workload information to justify the request, such as the number of environmental documents the department needs to complete, or the number of projects for which design work must be accomplished in the year. Nor does the plan identify any outcomes that were to be achieved with the requested funding and staffing, such as the completion of certain project milestones. Furthermore, none of the information provided includes workload standards for COS activities, such as the number of hours it should take to complete various tasks, so that the program’s efficiency can be assessed.

Thus, based on the information provided in the work plan, it is impossible to determine whether the requested funding and staffing levels provide what the department actually needs to deliver transportation projects. Nor does the work plan provide the Legislature the information it needs to determine how efficient the department has been in delivering capital projects.

Other Information Evaluated. Because the department’s information provided through the annual budget process fails to justify the program’s budget level, we reviewed other information in order to gauge the reasonableness of the department’s COS requests for funding and staffing. In performing this analysis, we talked with several other agencies that deliver capital projects, and reviewed project–specific data on Caltrans support costs. We discuss our findings from these efforts below.

We reviewed information on capital support costs from numerous other state and local agencies in order to compare and evaluate Caltrans’ COS costs and performance. This information included reviewing reports published by Departments of Transportation in other states regarding their support costs. We discussed these issues with state officials from other states. We also surveyed local transportation agencies on their support costs for projects and compared them to Caltrans for comparable projects. We discussed these issues with other transportation program experts, and, to gain a greater perspective on these matters, also examined the support costs that are incurred for capital outlay activities in California other than transportation projects.

Our review indicates that Caltrans’ costs for project support work appear to be much higher than those incurred by other agencies that perform similar types of work. In some cases, other agencies delivered projects nearly identical to some Caltrans projects, but with significantly lower support costs. Similarly, non–transportation capital outlay projects in California generally have support costs that are lower than Caltrans’ costs for transportation projects.

When we asked the department about these discrepancies in costs, Caltrans contended that such comparisons are not fair and could potentially be misleading because of differences in how support costs are counted. For example, some agencies count certain construction management activities as part of the capital cost of a project rather than as a support cost.

Our review found that there are some real differences among agencies in regard to which costs for the delivery of capital projects are counted as support. However, our analysis further indicates these differences alone do not fully explain Caltrans’ comparatively higher costs. Rather, it appears that Caltrans’ higher program costs are likely due to the comparatively greater staffing levels used to deliver projects.

For instance, the costs being reported by other transportation agencies for performing certain types of support work, such as construction oversight or project design and engineering, are much lower than Caltrans’. Our review indicates that the costs for the other transportation agencies were lower for these functions because they accomplished them with fewer staff and more efficient procedures. In one such case, an agency was able to manage and oversee the construction of a project with substantially fewer staff than Caltrans had requested to perform the same work. The lower support costs for non–transportation capital outlay projects in California also appear to be, at least in part, due to fewer support staff used to complete the project.

Region–to–Region Comparison. As part of our analysis, we also compared the staffing provided in different Caltrans regions for COS workload. The department groups its 12 districts into seven regions for COS and project delivery purposes. While each of these regions have some specific workload that is unique, support costs are accounted for in a consistent manner across the state. In addition, each region must abide by the same set of state laws and departmental rules. As we discuss in greater detail below, our region–to–region comparison found that the staffing levels in each region do not correspond closely with their capital program. The data available to us for this component of our review was insufficient, in a number of respects. Based on the limited information we were able to obtain, however, it appears that the high staffing levels in the regions are driving the cost for the COS program.

Staffing Levels High Relative to the Size of the Capital Program. Because the purpose of the COS program is to support capital projects, the staffing provided within each region should, in theory, tie closely to the magnitude of its capital program. Caltrans should be comparing its capital outlay staffing with its workload on an ongoing basis to ensure projects are being delivered efficiently and that resources are distributed appropriately across the state. Unfortunately, the department was unable to provide us with such comparison data. For this reason, we prepared our own such analysis that compares the number of positions in each region to the size of its corresponding capital program, as measured in dollars. Because the Caltrans work plan does not provide data on the actual workload that must be accomplished for each project, our analysis was based on the capital funding allocated for projects in each region. We concluded that this approach would at least provide a rough comparison of these factors.

Our review shows that the allocation of COS staff among regions has little correlation to the size of the capital program in each region. As Figure 5 shows, some regions have substantially more positions supporting their capital program than others. Some regions have very high staffing levels even though their capital program is relatively small. However, caution should be used in interpreting some of the data presented in the figure. This is because many factors affect the size of a particular region’s capital program and there are some legitimate reasons for variations among regions. For instance, the projects in a particular region may have generally low capital costs but still require a fair amount of design and engineering or environmental review. On the other hand, regions with projects with large material and construction costs, such as the Oakland–San Francisco Bay Bridge replacement, would have relatively lower staffing per capital dollar.

Figure 5

COS Staffing Unrelated to Size of Capital Program

(Dollars in Millions)

|

District/Region

|

Number of

Positions

|

Capital

Program

|

Positions Per

$100 Million

In Capital

|

|

Bay Area (District 4)

|

1,710

|

$4,293

|

40

|

|

Central Region (Districts 5, 6, 9, and 10)

|

1,552

|

828

|

187

|

|

North Region (Districts 1, 2, and 3)

|

1,450

|

1,456

|

100

|

|

Los Angeles (District 7)

|

1,029

|

1,333

|

77

|

|

Inland Empire (District 8)

|

713

|

483

|

148

|

|

San Diego and Imperial (District 11)

|

651

|

865

|

75

|

|

Orange County (District 12)

|

402

|

340

|

118

|

|

Headquarters

|

2852

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

10,359

|

$9,599

|

108

|

However, because each region has such a mix of projects, these factors can account for only part of the differences between regions. Caltrans was unable to explain why COS staffing levels in some regions are so much higher than in others. Coupled with the lack of workload justification for the program, the data indicate that at least some of the regions have more COS staff than is warranted by their capital program.

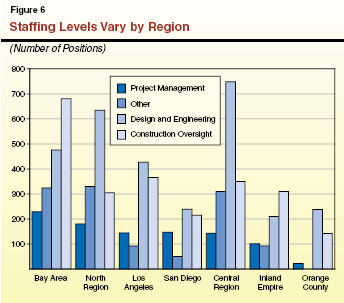

Staffing by Function Appears High Relative to the Capital Program. In order to assess the appropriateness of Caltrans staffing levels by yet another measure, we asked Caltrans to document how its staffing levels for various functions (such as design and engineering, or construction oversight) match up with the workload for those functions. Because the department was unable to do so, we prepared our own analysis to compare COS staffing by function in the regions relative to the regions’ capital program. Figure 6 shows the staffing for design and engineering, construction oversight, and other COS functions in the regions. As the figure shows, some regions have a very large staff for design and engineering or construction oversight. However, our review again finds that the staffing in those regions does not seem to correlate to projects programmed for those regions in the STIP, SHOPP, and other programs.

For example, the department reports that the Central Region has a design and engineering staff of about 750 positions for 2009–10. Our review of the STIP and SHOPP programs, however, indicates that the region does not need such a large design and engineering staff to perform the work reflected for that region in Caltrans’ work plan. The 2008 STIP document shows that the region had only $23 million in design and engineering work on STIP projects for 2009–10 (accounting for roughly 200 positions). It is highly unlikely that other work, such as designing SHOPP projects or other local projects, would constitute enough workload to justify the remaining 550 positions. Based on similar comparisons of workload by function to staffing in other regions, it is likely that some regions have more COS staff than warranted by their capital program.

Lack of Information Hinders Evaluation on Furlough Impacts. As noted above, Caltrans has been unable to document how its staffing level ties to the COS workload it is to achieve in 2009–10. Caltrans likewise cannot account for how its work has been affected by the furloughs imposed in 2009–10 across state executive branch agencies, including Caltrans, through an executive order of the Governor.

The current furlough program requires Caltrans staff to take three unpaid Fridays off each month, effectively reducing staff resources by roughly 15 percent in 2009–10. When asked to identify the projects in the 2009–10 COS work plan that would be delayed due to staff furloughs, Caltrans could only identify minimal impacts, such as a reduction in its planned sale of excess property. For the majority of the activities performed by the COS program, Caltrans responded that it is not possible to determine what work would not be completed this year.

Caltrans indicates that it has taken some actions to ensure the completion of the programmed work. Specifically, the department has indicated that roughly 30 percent of its direct COS staff was placed on a self–directed furlough program. This allows staff to work on furlough days and use their day off at another time. Regional and district managers have indicated that staff have been taking self–directed furloughs on days when work is slower, such as when construction oversight work is halted due to bad weather. However, as of mid–February, the department reported that only a very small portion of furlough days remained unused, meaning that self–directed furloughs notwithstanding, staff have been taking off work on their furlough days.

Lack of Furlough Impact Indicates Overstaffing. The department’s inability to estimate the impact of the furlough program indicates overstaffing in the COS program. Because the furlough program was not accounted for when the current–year staffing request was developed, the 15 percent reduction in resources should have a quantifiable reduction in outcomes of the program, such as achievement of project milestones. Given that there is little concrete evidence that the program’s output has declined due to furloughs, the program appears to be overstaffed by as much as 15 percent.

A Rule of Thumb for Evaluating Support Costs. The department’s Chief Engineer indicates that, as a general industry standard, project support costs should be about 30 percent to 32 percent of the capital cost of a project. For example, if the capital cost of a project is $1 million, support for that project should cost roughly $300,000, for a total cost of $1.3 million. This is consistent with a previously established Caltrans goal of keeping support costs below one–third of the capital cost of projects. Some variation for particular projects is considered reasonable. However, the COS cost to capital ratio described above provides a good general rule of thumb to use when evaluating COS costs department wide. Accordingly, we reviewed a sample of 30 Caltrans projects to see whether support costs aligned with this standard.

High Support Costs Seen on a Sample of Projects. For our project–level review, Caltrans provided the details of support costs for a sample of 30 STIP projects selected by the department. These projects were located throughout the state and had capital costs ranging from under $1 million to over $87 million. The sample included high–occupancy vehicle lanes, conversion of a two–lane highway to an expressway, new interchanges, operational improvements, landscaping, and others. While these projects do not represent all the types of work in the COS program, they are representative of typical STIP projects and are the only detailed project–specific data the department would provide.

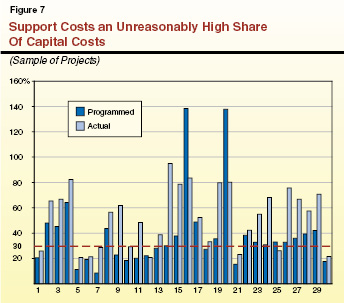

Our review of the data indicates that support costs on some of the sample projects are unreasonably high. Figure 7 compares the programmed and actual support expenditures for each project in the sample. As the figure shows, the actual support costs on many of the projects were well above one–third of the capital cost of the project. In fact, 19 of the projects (or 63 percent) had support costs exceeding 40 percent of their capital costs. Because there may be legitimate reasons that projects would occasionally have high support costs, we asked Caltrans to explain why the costs for the projects in the sample were so high. However, the department was unable to do so for any of the projects.

Very High Programmed STIP Support Costs Are Being Authorized… Caltrans and local transportation agencies program the cost and schedule of STIP projects by phase, including cost estimates, for environmental review, right–of–way support, design and engineering, and construction oversight. Caltrans staff indicates that support cost estimates are developed by project managers and reviewed by the district management for that region. However, our review finds that projects are not evaluated consistently across the department to ensure the reasonableness of each project’s support budget. Thus, individual projects could receive authorization to spend large sums on support even if those costs are potentially excessive.

As Figure 7 shows, 17 of the projects were initially budgeted with COS costs above the 30 percent benchmark, with many well above this level. Two projects were programmed for support costs of nearly 140 percent of the capital cost to build the project. Caltrans was unable to explain why these high support budgets were warranted and approved for the projects.

…Yet Actual Spending on STIP Support Is Greatly Exceeding the Programmed Amounts. Although the support budgets that are initially being set for capital projects appear to be unjustifiably high, the actual amounts being spent for the projects are far exceeding the budgeted amounts. Strong evidence of this was found in our review of the sample of 30 STIP projects.

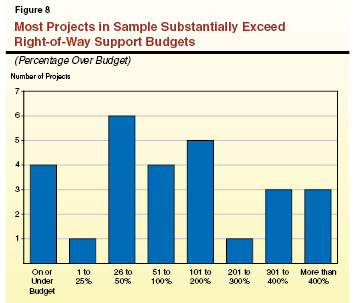

Our review shows that project overspending for support costs tended to occur mainly for right–of–way support (such as acquiring land on which to build a project) and construction oversight (overseeing the construction contractor and testing the materials used in the project). As shown in Figure 8, only four projects were within the original budget for right–of–way support, with most of the sample projects exceeding the planned amount, some by four times the initial amount budgeted. (Three projects failed to report any right–of–way cost information.)

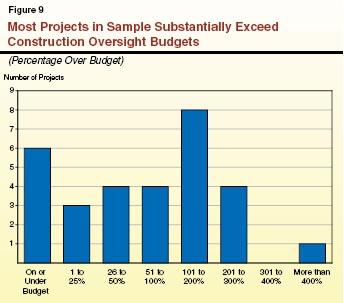

Similarly, most projects in the sample exceeded the planned amount for construction oversight, as shown in Figure 9, in a number of cases by substantial amounts.

Support Costs on SHOPP Projects Unknown, Lack Accountability. We also requested data on the planned and actual costs for a sample of SHOPP projects, similar to the STIP project sample. Caltrans responded that it has not tracked support cost information department wide on individual SHOPP projects. However, after our initial inquiries, the department now claims that since mid–2009 it has begun tracking this information. After repeated requests, Caltrans provided some limited information on support costs for SHOPP projects. However, the data provided lacks details, such as costs by phase and the associated capital cost of the projects, to allow any meaningful assessment. To the extent that support costs on SHOPP projects are still not comprehensively tracked and evaluated, there is little accountability on spending for support work on SHOPP projects, and it cannot be determined whether support expenditures for these projects are justified or not.

As noted above, support budgets for projects are developed by project managers and reviewed by the district management for each region. While projects are not consistently evaluated across the department, Caltrans previously set a goal that project managers were to keep project support costs below one–third of capital costs. However, the department reports that it has recently abandoned that goal, leaving no statewide cost control measures in place.

Currently, Caltrans indicates that its main method for controlling support costs on all projects is to check staff time cards to make sure that only staff who actually work on a project charge their time to that project. However, Caltrans’ headquarters acknowledges that regions are performing this function so poorly as to provide little or no accountability for these expenditures. The COS managers in headquarters indicate that they do not learn about overspending on project support costs until after it has already happened, thus providing the department no opportunity to intervene and keep these costs under control.

Based on our analysis, Caltrans lacks justification for the staffing and funding levels it has previously received for the COS program and is generally unable to provide basic information about the status and workload of the program. The cumulative weight of the evidence, based on the various methods we used in this analysis, indicates that the program has high costs due to overstaffing and insufficient departmental oversight of the program. We think that major actions are needed to correct these issues, as proposed below.

Require Additional Justification of COS Budget Request. To begin to remedy these concerns, we recommend that the Legislature adopt statutory language as part of the 2010–11 budget package requiring Caltrans to provide additional information to justify its annual COS budget request on an ongoing basis, beginning with the 2011–12 budget. We also recommend the Legislature direct Caltrans to initially include key components of this workload information with its May Revision budget request for 2010–11. The information provided should include:

- A summary of the projects to which the department plans to allocate COS resources in the budget year. This should include, for each region, (1) the amount of PYEs allocated by program (SHOPP, STIP, and other programs); (2) the number of projects in each phase of work (such as environmental review, design and engineering, or construction oversight); and (3) the total capital cost of all projects. In addition, the department should provide the Legislature, upon request, with specific information for all its projects similar to the data we obtained for our sample of 30 STIP projects.

- A description of expected COS workload over the next five years.

- A description of the workload standards used by Caltrans to evaluate the reasonableness of support budgets for specific projects.

We acknowledge that our proposal would require Caltrans to track, compile, and report a large amount of data. However, based upon the findings of our analysis, we have concluded that this information is critical for the sound management of the $2 billion COS program and for proper legislative oversight of Caltrans’ efforts in this regard.

Cost Controls Should Be Adopted for the COS Program. In light of the problems identified above, we recommend that the Legislature direct Caltrans to report at budget hearings on the steps it is taking to control its COS costs. At a minimum, such cost control measures should include the following:

- A consistent department wide process for reviewing project budgets that have support costs in excess of its standards. Such reviews should be performed by program managers in headquarters in conjunction with regional or district staff. The reviews should include (1) an evaluation of the tasks that need to be completed for each project, (2) the hours of staff time estimated to complete those tasks, (3) an assessment of how the estimate compares to workload standards for each task, and (4) specific justification for any significant departure from the workload standards.

- A department wide process for monitoring support expenditures for each project in comparison to the work that has been completed on that project.

- Tighter controls on allowing staff time to be charged to a particular project. For instance, supervisors should be required to thoroughly review all charges made by staff under their direction, and project managers should be held accountable for staff costs that are charged to the projects they are managing.

Request Audit of Time Records. Caltrans staff has indicated that there is currently very little control over how many hours staff members charge to projects. As a result, it is possible that employees could charge time to a project even if they have not performed any work, or were not authorized to do so. In light of this serious issue, we recommend the Joint Legislative Audit Committee consider requesting the Bureau of State Audits (BSA) to perform an audit of Caltrans COS staff time charging practices to determine the extent of this problem.

Reduce Staffing for COS. It is clear from our analysis that the COS program is overstaffed. However, due to the limited workload information now available to us, it is difficult to precisely determine the level of reduction needed to bring staffing in line with workload. Caltrans’ inability to demonstrate that any significant project delivery impacts resulted from the 15 percent reduction in staff time imposed under the furlough program, together with other evidence we have accumulated, indicates that the department may be overbudgeted for its direct COS work by as much as 15 percent, or roughly 1,500 PYEs. Accordingly, if Caltrans is unable to provide workload justification for its 2010–11 request, we recommend that the Legislature reduce the budget for direct COS by 1,500 PYEs in 2010–11. Such a reduction would free up about $200 million annually that could be used for capital projects. In addition, the Legislature should have Caltrans report at budget hearings on the corresponding reductions that would be warranted for indirect support activities and program overhead costs commensurate with a 1,500 reduction in PYEs.

Chapter 2, Statutes of 2009 (SBX2 4, Cogdill), authorizes Caltrans, in cooperation with regional transportation agencies, to enter into an unlimited number of toll or fee–generating public–private partnership agreements for transportation projects (commonly referred to as P3 projects) through 2016. Specifically, Chapter 2 allows Caltrans to enter into such agreements for various phases of a project’s development and operation, such as the planning, design, financing, construction, operation, and maintenance of highway, street, or rail facilities. Chapter 2 also requires agreements to authorize and establish tolls or user fees to pay for the facilities.

The Governor requests that $3.45 billion in future federal transportation funds be appropriated to Caltrans to pay private–sector firms for costs related to an unspecified number of transportation P3 agreements. These monies would be provided through a continuous appropriation, meaning that these expenditures in future years would not be subject to further legislative review and approval in the annual budget act. Of the total amount, about $1 billion would potentially be used for one project—the Doyle Drive replacement project in San Francisco. Caltrans would pay a private partner to develop and construct the project, then to operate and maintain it over 30 years. The other projects that would be supported from this appropriation have not yet been identified by the administration. In addition, the budget requests authority for the Department of Finance (DOF) to augment the appropriation indefinitely and without restriction.

Our review indicates that the Governor’s proposal has several significant problems, which we discuss below.

Revenue–Generating Projects Contemplated Under Current Law. Chapter 2 specifically requires that P3 project agreements include financing from toll or user fee revenues. Such sources of funding would be used to pay for the capital outlay and operating costs of P3 projects, as well as to provide the state’s private partners with a reasonable return on their investment. However, Caltrans indicated that tolls or user fees would not be charged on the projects contemplated in its budget proposal. Instead, the state would simply make payments to its private partners for each projects’ design, construction, operation, and maintenance over 30 years, using available federal funds. Thus, this type of agreement does not appear to be allowed under the P3 authorizing legislation.

Budget Proposal Not Workable Using Only Federal Funds. In theory, the Legislature could amend Chapter 2 to allow the department to enter into an agreement that does not require tolls or user fees. However, the budget proposal would still not work. This is because an unidentified portion of the costs the state would pay under the proposed P3 agreements would be for the operations and maintenance of transportation facilities. These costs are not eligible for federal funding.

Details Not Provided for $2.5 Billion of Request. The department is not able to explain how it plans to spend the majority of the funds requested. In particular, about $2.5 billion of the request would be available to pay private firms for projects that have not yet been identified. Absent such information, in our view, the Legislature should not make such a large commitment of funds.

P3 Approach to Identified Project May Not Reduce State Costs. Caltrans contends that its privatization strategy would reduce state costs for projects over time. In support of this claim, Caltrans provided a comparison of the cost of funding the one identified project (Doyle Drive) through a P3 agreement versus the cost if the project were constructed and operated in the same way as other highway projects. The department plans to pay a third party a set amount to construct, operate, and maintain the proposed highway facility over multiple years. These costs were compared with the costs and benefits of procuring the design and construction of the project through the department’s standard practices, then having the department operate and maintain the facility as part of the overall state highway system after the facility was constructed.

While we are still in the process of reviewing the data, it is unclear how the P3 procurement would achieve certain cost savings that it assumes would save the state money over the life of the project. For instance, the comparison assumes that a private partner would be more efficient at managing the construction of the project, which would result in savings. However, the basis for assuming these efficiencies is not identified.

Proposal Prioritizes P3 Projects Over Other Highway Needs. The proposal would set aside a sizeable amount of the state’s transportation funds to pay for P3 projects. This would reduce the amount of funding available for the rest of the state’s highway maintenance and repair needs. The Legislature should consider carefully whether it makes sense to make large commitments of federal funding “off the top” to the P3 projects, given significant competing state highway needs.

Budget Requests a Blank Check. The budget request includes language that would provide DOF with open–ended authority to augment the proposed appropriation. The proposal would allow the administration to spend an unlimited amount of future federal funds, and would be authorized indefinitely. As such, the request amounts to a blank check that provides little or no opportunity for legislative review and oversight of these expenditures in the future.

Administration Reconsidering Its Proposal. After discussing our concerns about the proposal with the department, the administration indicated that it is reviewing its proposal and plans to revise its request in the spring.

For the reasons outlined above, we recommend rejecting the request. Furthermore, we recommend that, in revising its funding request for P3 agreements, the department ensure the following:

- The proposal is authorized under current law, or includes proposed statutory changes to allow implementation of the proposal. It must also be workable given the restrictions and requirements of the proposed funding source.

- The proposal clearly explains how the funds requested would be used, such as a list of projects or activities that the department plans to fund and the associated dollar amounts requested for these purposes.

- The proposal identifies the criteria and methodology used to establish benefits to the state from the funding agreements. For instance, the proposal should demonstrate whether the use of payments would allow a project to be completed at a lower cost, or significantly sooner than would otherwise be the case.

- The proposal explains the impact of prioritizing the maintenance of privately managed transportation facilities on the state’s ability to fund maintenance and repair of the rest of the highway system operated by the state.

California voters have authorized more than $19.9 billion in Proposition 1B bonds for various transportation improvements. The budget requests a reversion of about $1.9 billion in prior–year appropriations of Proposition 1B bond funds that could not be used in a timely manner due to the state’s difficulties in selling bonds. After taking this adjustment into account, the state has appropriated about $11.6 billion in bond funds. For 2010–11, the budget requests the appropriation of $4.7 billion in additional Proposition 1B funds to meet current program needs. Figure 10 shows the total amount of bonds authorized by the voters in each category; prior–year appropriations, adjusted for the amounts that would be reverted; and the amounts requested for the budget year.

Figure 10

Appropriations of Proposition 1B Funds

(In Millions)

|

Program

|

Authorized

Amount

|

Appropriated

|

Balance

|

|

Prior Yeara

|

2009–10

|

Proposed 2010–11

|

|

Corridor Mobility

|

$4,500

|

$1,894.7

|

$1,357.9

|

$1,147.7

|

$99.7

|

|

Trade Corridors

|

2,000

|

182.9

|

490.5

|

673.8

|

652.8

|

|

Local Transit

|

3,600

|

950.0

|

350.0

|

350.0

|

1,950.0

|

|

STIP

|

2,000

|

1,376.9

|

57.4

|

525.2

|

40.6

|

|

Local Streets and Roads

|

2,000

|

1,287.2

|

700.0

|

—

|

12.8

|

|

SHOPP

|

750

|

368.8

|

75.1

|

258.2

|

48.0

|

|

SLPP

|

1,000

|

160.3

|

200.5

|

200.8

|

438.4

|

|

Grade Separations

|

250

|

33.5

|

0.7

|

75.6

|

140.3

|

|

Highway 99

|

1,000

|

52.3

|

433.2

|

310.9

|

203.6

|

|

Local Seismic

|

125

|

34.6

|

31.2

|

22.9

|

36.2

|

|

Intercity Rail

|

400

|

103.0

|

126.3

|

71.5

|

99.3

|

|

School Bus Retrofit

|

200

|

193.0

|

3.0

|

4.0

|

—

|

|

Air Quality

|

1,000

|

500.3

|

250.1

|

249.6

|

—

|

|

Transit Security

|

1,000

|

202.9

|

101.5

|

101.0

|

594.6

|

|

Port Security

|

100

|

99.2

|

—

|

0.8

|

—

|

|

Total Appropriations

|

$19,925

|

$7,439.5

|

$4,177.4

|

$4,744.1

|

$3,564.0

|

Funding Requested Is Higher Than Needed for Projects. The appropriation of funds requested for some of the Proposition 1B programs does not appear to match the planned schedules for projects in those programs. Specifically, the requested appropriation levels for some of the Proposition 1B programs are higher than needed. For instance, the budget requests $674 million in additional appropriations for the Trade Corridors Improvement Fund program for 2010–11 on top of the $673 million that has already been appropriated for these purposes. Our analysis indicates that this would result in the appropriation of about $300 million more in funding for the program than is needed based on current project schedules. Similarly, the budget proposes to appropriate most of the remaining Corridor Mobility Improvement Account funds even though some of the projects in that program would not begin construction until 2012.

Analyst’s Recommendation. We recommend that the Legislature direct Caltrans to report at budget hearings on the specific projects that are planned for allocation through June 2011 and their associated amounts of bond funding. We recommend the Legislature adjust the appropriation of Proposition 1B funds accordingly to provide only the amounts needed based on the schedule of projects in each program.

Chapter 21, Statutes of 2009 (ABX3 20, Bass), allowed Caltrans to use federal stimulus funds provided under the ARRA to provide $310 million in cash loans to Proposition 1B projects in 2008–09 and 2009–10. These loans allowed four state highway projects to proceed to construction that otherwise would have been delayed due to the state’s difficulties selling bonds. Similarly, several local agencies used a portion of their ARRA funds to advance Proposition 1B projects

Analyst’s Recommendation. In the event that California receives more federal stimulus funds for transportation, we recommend the Legislature enact legislation to authorize additional cash loans to Proposition 1B projects. In total, there are about $600 million in Proposition 1B projects ready to start construction, but that are delayed due to insufficient bond funding. Of these projects, Caltrans estimates that $428 million are federally eligible and could therefore be advanced if additional federal stimulus funds are provided. To do so, however, would require the approval of new state legislation, since the existing authority relates only to federal stimulus funds already received under ARRA.

The High–Speed Rail Authority (HSRA) was statutorily established to develop a high–speed rail system in California that links the state’s major population centers, including Sacramento, the San Francisco Bay Area, the Central Valley, Los Angeles, the Inland Empire, Orange County, and San Diego. The latest cost estimate for completion of the first phase of the project, from San Francisco to Los Angeles and Anaheim via the Central Valley, is roughly $43 billion. (This cost estimate reflects the escalated cost of each portion of the project at the time it is to be built.) In November 2008, voters approved Proposition 1A, which allows the state to sell $9 billion in general obligation bonds to partially fund the development and construction of the high–speed rail system. The remaining funding for the system’s construction and operation is anticipated to come from federal and local governments as well as the private sector.

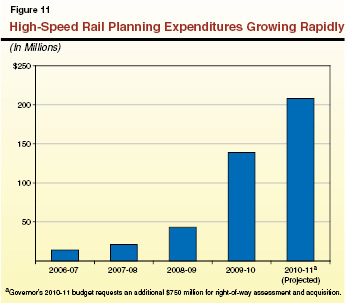

Over the past few years, the development work for the high–speed rail project has been increasing. As shown in Figure 11, the authority’s support expenditures have grown very quickly since 2006–07. This figure includes the authority’s administration costs as well as the costs of consulting contracts to plan and develop the system. These contracts include:

- Program management, which includes oversight of all engineering work.

- Project–level engineering and environmental studies conducted along the corridors by various contractors.

- Financial consulting and public–private partnership development.

- Technical consulting such as ridership forecasts and visual simulations.

Through the current year, nearly all funding for project development has come from the state. However, the authority anticipates using some federal stimulus funding available through the ARRA to supplement state funds beginning in 2010–11. Additionally, the current–year budget authorizes the state to replace state bond funding with federal funding if allowed by federal law. Thus, it is possible some of the federal stimulus funding would be used in the current year as well.

The ARRA provides $8 billion nationwide to fund rail projects, including high–speed rail development programs. The authority applied for more than $4.7 billion of the available funding to be used in three specific corridors as well as for systemwide planning and environmental clearance. Though not required under ARRA, the state’s application for funds pledged to match any ARRA funds awarded to the high–speed rail project with an equal amount of state monies.

Project Awarded $2.25 Billion. On January 28, 2010, the federal government awarded California $2.25 billion toward the development of the high–speed rail system. (California also received $99 million to improve and upgrade the state’s current intercity rail program.) The funding will be available for program development and environmental clearance for the entire first phase of the project, as well as design–build contracts in four of the project’s ten corridors, including:

- Los Angeles to Anaheim.

- Merced to Fresno to Bakersfield.

- San Francisco to San Jose.

The other corridors were not included in the grant application because they are not far enough along in the development process to meet the ARRA deadlines.

Funding Availability and Expenditure Timeline. It is unknown at this time when the ARRA funding will be available or how it will be divided among the various eligible segments of the project. According to interim guidance released by the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) in June 2009, the money must be obligated by September 2011 and fully expended by September 2017. According to FRA’s interim guidance, these funds will be considered obligated when a grant or cooperative agreement between the federal agency and the state is complete. The grant agreement will describe project milestones and what steps must be taken for the state to access these federal funds. However, because it is unknown at this time when this agreement will be reached, there is no way of knowing when the federal funds will become available for expenditure.

Bond Funds Will Match Federal Dollars. At the time of this analysis, it is also unclear how the authority plans to structure the pledge to match federal funds with state bond funds. For example, one way to provide this match would be to apply one state dollar for every federal dollar spent, whether it is for the purchase of land or some other service. This would mean that federal dollars would provide one–half of the funding for a particular contract or section of right of way, and the state bond money would fund the other half of the same expenditure. Alternatively, the authority could simply apply an equivalent amount of bond dollars to a particular segment of the system, regardless of what the particular expenditure may be. In this case, state funding may pay for a consulting contract to complete the environmental work on a section of the system where an equivalent amount of federal funding has purchased the right of way. How the authority plans to use state bond funds to match ARRA dollars would determine when the state would have to issue Proposition 1A bonds as well as the amount to issue in the budget year.

Analyst’s Recommendation. Because of the deadlines attached to the ARRA award, it is imperative that HSRA act expeditiously to meet federal requirements. In addition, the state should consider how to most effectively spend the federal dollars while reducing the debt service burden on the state in the near term. Therefore, we recommend that the authority report at budget hearings on its plans to meet the ARRA deadlines. Specifically, the HSRA should discuss the following:

- What restrictions are placed on the federal funds?

- How much of the ARRA funds are available for each segment or task?

- How will the authority structure the state’s match of federal funds?

- What steps must be taken in order to obligate the funds?

- How will HSRA ensure that the project schedule meets the federal obligation deadline?

The 2009–10 Budget Act (as amended in July 2009) required the authority to submit to the Legislature a revised business plan with specific elements by December 15, 2009. The plan was submitted on time, and included at least some discussion of all the required elements. The new plan is much more informative than the previous business plan, and contains, among its other components, descriptions of potential operational plans and many system details, as well as a discussion of various funding possibilities available for the project.

Nonetheless, our review of the plan concludes that the plan’s discussion of particular elements is lacking some important details. Specifically, the plan lacks discussion of risk management, including any detailed description of many key types of risk or mitigation processes. Also, there are few deliverables or milestones identified in the plan against which progress can be measured. Due to the multiyear nature of a project of this size, without clearly defined deadlines and work to be accomplished, it will be difficult for the Legislature and the administration to track progress in any meaningful way.

Analyst’s Comments. Chapter 618, Statutes of 2009 (SB 783, Ashburn), requires the authority to prepare, publish, adopt, and submit to the Legislature an updated business plan addressing specific elements no later than January 1, 2012, and every two years thereafter. We will be reviewing the submitted plan to ensure compliance with statutory requirements and identify any improvements that are needed in these documents.

Authority Submitted Program Work Plan Through 2012–13. The Legislature approved $139 million to fund continued preliminary planning of the rail system during 2009–10, including project–level design and environmental review for all ten segments of the rail line, program management services, financial planning, and development of a new ridership model. In order to justify the current–year funding level, the authority submitted a Program Summary Report to the Legislature in July 2009, which described the authority’s recent and ongoing activities as well as the expected work to be completed each year through 2012–13. This multiyear summary is intended to outline the management plan to move the project through the environmental processes to construction and revenue service. However, our analysis indicates there are questions about how progress on the project is being tracked. We explain these concerns below.

Actual Progress Does Not Appear to Follow Work Plan. So that the authority’s staff can track the project’s status against the work plan laid out in the Program Summary Report, the HSRA’s program management consultant provides monthly status reports on a list of specific tasks that each have their own due date. However, our review shows that some of the tasks contained in recent status reports are inconsistent with those listed in the work plan. For instance, the November 2009 status report only provided an update on one–half of the 160 uncompleted tasks identified in the work plan, with the remaining tasks deleted or missing. When asked about these discrepancies, the authority indicated that some of the tasks might have been combined or considered unnecessary, but could not definitively explain these changes.

Progress Report of Project–Level Work Plan Provides No Details. The monthly status reports submitted to the authority are problematic in another way: they provide only summary information on the progress of project–level work being accomplished by contractors. The work plan lays out the expected timelines for the particular tasks to be accomplished each year by each of these contractors. However, our review indicates that the monthly reports do not track each contractor’s status against the work plan. Instead, the reports only summarize the cumulative amount of time spent on the project by the contractors collectively. Without more detailed information, it is hard for the Legislature to determine what work is being accomplished by each contractor in the current year and what work remains to be done in subsequent years.

Analyst’s Recommendation. Multiyear mega projects such as the high–speed rail project are susceptible to significant unexpected challenges in their planning, development, and construction as well as financing. For example, a 2004 report by the BSA regarding the replacement of the Oakland–San Francisco Bay Bridge, another mega project, found that a considerable financial crisis arose in part due to the project management’s failure to disclose huge cost overruns as soon as it was aware of them. Because the state has committed a significant amount of funding for the high–speed rail project, it is important that the Legislature be provided from the outset with regular updates on the project’s progress to avoid unexpected challenges in the project’s development.

Therefore, we recommend the Legislature adopt legislation to require the authority to submit an annual report that tracks the project’s progress and identifies (1) the expected tasks and deliverables for the coming year, and (2) any potential challenges and issues the project encounters. This information would enable the Legislature to better assess the authority’s budget request for the subsequent year. The report could be structured similar to those required for the oversight of the Bay Bridge replacement project. Information should include, but not be limited to:

- A baseline budget, by contract, for capital and support costs.

- Expenditures to date, by contract, for capital and support costs.

- A comparison of the current or projected schedule and the baseline schedule that was assumed.

- A summary of milestones achieved during the previous year.

- Any issues identified, and actions taken to address those issues, in the previous year.

This report should be submitted by September 1 of each year. This date would give the authority time to compile details of the past fiscal year, clearly identify current–year deliverables, and provide an outline of the expected work plan for the coming budget year.

The Governor’s budget requests $958 million to fund the authority’s activities in 2010–11, including $375 million in expected federal economic stimulus funds and $583 million in Proposition 1A bond funds. The total request will be used for three purposes. First, $750 million is requested for right–of–way assessment and acquisition. Second, $203 million would go for consulting contracts to perform system development work. Finally, the remaining $5 million would cover the authority’s administrative costs. We comment on each of these budget proposals below.

Total Capital Outlay Request Not Needed in Budget Year. The authority is requesting $750 million for right–of–way acquisition in the budget year. At the time the Governor’s budget was being prepared, the authority did not know how much ARRA funding the state would be awarded or when the federal dollars would become available. Therefore, the $750 million request, comprised of $375 million from the state and an equal amount of federal funds, was a placeholder amount based on the authority’s best estimate at the time. However, HSRA has indicated in recent discussions that it would not need the total amount requested in 2010–11. The authority now believes it will need no more than $250 million to begin negotiations with large landholders.

Analyst’s Recommendation. Based on the authority’s updated estimate of the funding needed for land acquisition, we recommend that the capital outlay funding level be reduced by $500 million to provide $250 million in 2010–11. Furthermore, we recommend the adoption of budget bill language, similar to the language in the 2009–10 budget, to authorize the HSRA to replace state bond funding with federal funding as it becomes available.

Little Justification Provided for Contract Amounts. In 2010–11, the authority is requesting $203 million for various contracts. Figure 12 lists the contracts the HSRA proposes to be funded in 2010–11, as well as the amounts expended on these contracts in the prior and current years. While the general types of proposed contract work appear reasonable, the authority’s budget requests provide no justification for the specific amounts requested for each contract. Also, as discussed earlier in this analysis, because the monthly status reports do not indicate whether the work planned for 2009–10 is actually being accomplished, the Legislature cannot determine whether the resources proposed for 2010–11 are appropriate and justified.

Figure 12

HSRA Contract and Administration Expenditures

(In Millions)

|

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

Projected

|

3–Year

Total

|

|

Contract Work

|

|

|

|

|

|

Project–Level Consultants (10)

|

$31.6

|

$103.0

|

$157.4

|

$295.6

|

|

Program Management

|

3.9

|

26.6

|

37.0

|

67.6

|

|

Ridership/Revenue Forecasts

|

—

|

2.0

|

1.0

|

3.0

|

|

Financial Plan

|

—

|

2.0

|

1.0

|

3.0

|

|

Program Management Oversight

|

—

|

0.4

|

2.0

|

2.4

|

|

Public Outreach

|

—

|

—

|

1.8

|

1.8

|

|

Resource Agency Agreements

|

—

|

—

|

1.8

|

1.8

|

|

Right–of–Way Development

|

—

|

0.8

|

0.2

|

0.9

|

|

Visual Simulation

|

—

|

0.3

|

0.4

|

0.6

|

|

Other Unspecified

|

9.2

|

2.3

|

—

|

11.4

|

|

Subtotals

|

($44.7)

|

($137.2)

|

($202.6)

|

($388.1)

|

|

Authority Administration

|

$1.8

|

$1.9

|

$5.2

|

$8.9

|

|

Totals

|

$46.4

|

$139.2

|

$207.8

|

$397.0

|

The authority’s funding requests for consulting contracts contain little information on the work to be accomplished over the budget year, or about how that work fits into the total development of the system. As a result, it is unknown how the amount for each contract was determined. This is the same concern raised in our analysis of the authority’s similar 2009–10 budget requests. The authority appears no more equipped to justify the requested contract amounts than it was one year ago.