The Governor proposes to increase California Community College (CCC) fees from $26 per unit to $36 per unit beginning in July 2011. We believe that a fee increase should be an important component of the state’s budget strategy for CCC, as it would leverage more federal funds (in the form of federal tax credits) to mitigate programmatic impacts on CCC instruction and services, while having no negative effect on financially needy students (who do not pay fees). While the Governor is on the right track, the Legislature might consider going even further in the budget year to tap additional federal dollars in support of the CCC system. In future years, we recommend the Legislature ensure that CCC fee levels are pegged to the maximum amount covered by federal tax credits.

The Governor proposes to increase CCC enrollment fees from $26 per unit to $36 per unit beginning in July 2011. This brief addresses how such an action could (1) benefit the CCC system and (2) protect affordability and access for financially needy and nonneedy students.

Fee Revenue Would Help Colleges. Community colleges receive three main sources of general–purpose apportionment funding: General Fund, local property taxes, and student fee revenue. As part of his budget–balancing solutions for 2011–12, the Governor proposes to reduce General Fund support for CCC by $400 million, or 6.9 percent of base apportionments. This represents a potential loss of funding that could serve over 80,000 full–time equivalent (FTE) students. The budget also proposes to increase fees from $26 per unit to $36 per unit, which would raise about $110 million in additional fee revenues (about 1.9 percent of base apportionments). This revenue would partially backfill CCC’s General Fund reduction, restoring funding for about 23,000 FTE students. Net base reductions to CCC’s 2011–12 budget would thus decline from $400 million to $290 million in 2011–12. Put another way, the effect of the Governor’s fee proposal would be to provide the community colleges with $110 million more in total resources than would have been available absent a fee increase. This would help the colleges provide more programs and services than would otherwise be possible.

Fee Increase Would Not Affect Needy Students, Who Are Not Required to Pay Fees. In considering any fee increase, the Legislature should consider the potential effects on student affordability and access. For financially needy CCC students, affordability is preserved through the Board of Governors’ (BOG) fee waiver program. This entitlement program is designed to ensure that community college fees will not pose a financial barrier to California residents. It accomplishes this by waiving enrollment fees for residents who demonstrate financial need. The program has relatively high income cut–offs. For example, a CCC student living at home, with a younger sibling and married parents, could have a family income up to approximately $65,000 and still qualify for a fee waiver. The family’s income cut–off would increase to roughly $80,000 if the same student lived away from home. An older, independent student living alone could have an income up to about $45,000, and a student with one child could have an income up to about $80,000 and still qualify for a waiver.

Increasing CCC fees thus creates no additional out–of–pocket expense for financially needy students, since these students qualify for waivers—whatever the fee level. In recent years, about one–third of all community college students (representing up to 50 percent of all units taken) have received BOG fee waivers. In 2009–10, about $365 million in fees were waived.

Federal Government Will Reimburse Most Fee–Paying Students. The vast majority of students who do not qualify for BOG waivers are still eligible for federal financial assistance that covers all or a portion of their fees. Figure 1 summarizes the features of the federal American Opportunity tax credit (AOTC), Lifetime Learning Credit, and tuition and fee tax deduction.

Figure 1

Federal Tax Benefits Applied Toward Higher Education Fees

2011

|

American Opportunity Credit

|

Lifetime Learning Credit

|

Tuition and Fee Deduction

|

- Directly reduces tax bill and/or provides partial tax refund to those without sufficient income tax liability.

|

- Directly reduces tax bill for unlimited number of years.

|

|

- Covers 100 percent of the first $2,000 in tuition payments and textbook costs. Covers 25 percent of the second $2,000 (for maximum tax credit of $2,500).

|

- Covers 20 percent of first $10,000 in fee payments (up to $2,000 per tax year).

|

- Deducts between $2,000 and $4,000 in fee payments (depending on income level).

|

- Designed for students who:

- Are in first through fourth year of college.

- Attend at least half time.

- Are attempting to transfer or acquire a certificate or degree.

|

- Designed for students who:

- Already have a bachelor’s degree.

- Carry any unit load.

- Seek to transfer or obtain a degree/certificate—or simply upgrade job skills.

|

- Designed for any student not qualifying for a tax credit.

|

|

|

- Provides full benefits at adjusted income of up to $160,000 for married filers ($80,000 for single filers) and provides partial benefit at adjusted income of up to $180,000 ($90,000 for single filers).

|

- Provides full benefits at adjusted income of up to $100,000 for married filers ($50,000 for single filers) and provides partial benefit at adjusted income of up to $120,000 ($60,000 for single filers).

|

- Capped at adjusted income of $160,000 for married filers ($80,000 for single fillers).

|

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act replaced the Hope tax credit with the AOTC in the 2009 and 2010 tax years. (For details on the Hope tax credit, please see the 2009–10 Budget Analysis Series: Higher Education, page HED–25.) The federal government recently extended AOTC through the 2012 tax year. As the figure indicates, income thresholds for AOTC are high. For example, students (or their parents) with a family income of up to $160,000 are eligible for a full federal tax credit equal to their fee payment—as well as textbook costs—for up to $2,000 per year. (The amount of the tax credit is gradually reduced between $160,000 and $180,000 for joint returns; $80,000 and $90,000 for single filers.) Therefore, if the state were to increase fees to $36 per unit (or $1,080 for a full–time student), eligible students taking 30 units per year would still pay—after taxes—nothing for courses, and would still be eligible to receive over $900 for full reimbursement of textbook costs. In addition, families or students with insufficient tax liabilities qualify for partial tax refunds (equivalent to 40 percent of qualifying expenses).

Students who do not meet AOTC’s academic requirements (such as those who already hold a bachelor’s degree or only take one course each term) can qualify for the federal Lifetime Learning tax credit, which provides a tax credit equal to 20 percent of fees. Finally, those not claiming the credits may be eligible for a tax deduction of up to $4,000 of the cost of fees. We estimate that roughly two–thirds of CCC students would qualify for full fee coverage through the BOG waiver program or AOTC. About 90 percent of CCC students would qualify for either a fee waiver or a full or partial tax offset to their fees.

Affordability and Access for High–Income Students. We recognize that some students (roughly 10 percent of total CCC students) do not qualify for any state or federal financial assistance due to their high income level, and thus would have to pay the full fee. It is possible that some students who would have attended CCC at $26 per unit would not enroll if the fee were raised. Because these students by definition are not financially needy, their decision not to enroll should not be considered a denial of access, but rather a choice they make about the benefit they will receive from community–college classes. Consequently, affordability and access for CCC students would be preserved even with a fee increase. (Please see the box on page 5 for a discussion about the effect of past fee increases on enrollment.)

|

Over time, CCC’s enrollment has fluctuated. Between 2002–03 and 2004–05, for example, enrollment dropped by about 11 percent. During this two–year period, fees increased twice: from $11 per unit to $18 per unit in 2003–04, and to $26 per unit in 2004–05. The number of students in the system dropped by approximately 300,000 (headcount), from 2.8 million in 2002–03 to 2.5 million in 2004–05. This equals a decrease of about 50,000 full–time equivalent (FTE) students in credit instruction between 2002–03 and 2004–05 (plus about 10,000 FTE students in noncredit courses). After a brief drop back down to $20 per unit, the Legislature returned fees to $26 per unit in 2009–10. Enrollment declined by about 140,000 students (headcount) that year compared with 2008–09.

Some cite these fee increases as the cause of enrollment decline. Our analysis suggests that this claim about fees being the sole or even the major cause of enrollment declines is exaggerated. In fact, there are other reasons for the enrollment declines, including:

Crackdown on Concurrent Enrollment. Much of the decline in enrollment from 2003–04 to 2004–05 was an intended result of statutory and budget changes to address systemic abuses involving concurrent enrollment. Beginning in 2002, the Legislature and Governor became concerned that a number of community college districts were inappropriately, and in some cases illegally, claiming state funding for a rapidly increasing number of high school athletes who were “concurrently enrolled” in CCC physical education courses. For 2003–04 the Legislature reduced funding for concurrent enrollment by $25 million and tightened related statutory provisions. As a result, high–school students concurrently enrolled in CCC courses dropped from about 100,000 (headcount) in 2002–03 to about 16,000 in 2004–05 (which translates into a drop from 15,000 FTE students to less than 2,000 FTE students). Thus, about one–quarter of the enrollment decline can be explained by a drop in these high school students—which was an intended policy reform entirely unrelated to fee increases.

Reduced Course Offerings. In a 2005 report to the Legislature on enrollment changes during the previous few years at CCC, the Chancellor’s Office suggested that an unknown amount of the enrollment decline can be explained by districts having reduced the number of course offerings. Districts reduced enrollment in anticipation of possible cuts to the CCC system budget during this period. Community colleges reduced about 10,000 course sections systemwide between fall 2002 and fall 2003—a reduction that was not fully restored until spring 2005. With fewer course offerings, some potential students were unable to find space in courses they wanted and thus did not enroll. (This explains why enrollment in noncredit instruction—which is free for all students—also declined during this time period.) Similarly, between 2008–09 and 2009–10, community colleges responded to budget cuts by reducing course–section offerings by a total of about 37,000 (9 percent). According to the Chancellor’s Office, this action prevented many students from finding open classes (particularly first–time students, who generally are among the last students allowed to register for classes).

In summary, a combination of factors likely contributed to earlier CCC enrollment declines, with fee increases having only a partial effect. |

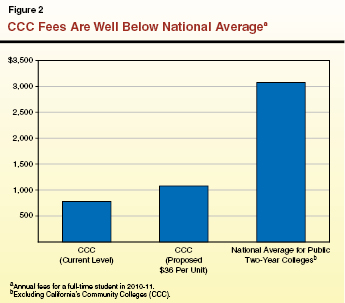

Even at $36 Per Unit, Fees Would Remain Lowest in Country. Over the past decade, CCC fee levels for credit courses have fluctuated between $11 per unit and $26 per unit. (There continues to be no charge for noncredit courses.) The state currently has no official policy for setting CCC fees. Often, fees have been increased during fiscally challenging periods, and reduced when budget situations improve. Despite this fluctuation, fees have consistently been the lowest in the country. Most recently, fees were increased from $20 per unit to $26 per unit in July 2009. As a result, a full–time student taking 30 units per academic year now pays $780 per year. This is $420 below that of New Mexico ($1,200, or about $40 per unit), which has the next–lowest fees among the country’s public two–year colleges. Figure 2 shows that the average for all other public two–year colleges ($3,075) is almost four times the amount charged by CCC. The figure also shows that, even at $36 per unit, CCC fees would remain significantly below the national average.

Recommend the Legislature Leverage More Federal Aid by Increasing Per–Unit Fee. Maintaining very low fees is an inefficient strategy for preserving affordability. While needy students are already shielded from fees through the BOG waiver program, low fees deliver high subsidies to nonneedy students—most of whom are eligible for substantial, if not full, fee refunds from the federal government. California, which charges only $780 for a full–time student, is one of the only states that does not take full advantage of these federal funds. In effect, the state is paying for costs that the federal government would otherwise pay and does pay in virtually all other states. Thus, a low fee policy actually works to the disadvantage of the state.

For these reasons, we find merit with the Governor’s proposal to increase fees to $36 per unit. Given the state’s budget situation and the availability of federal tax credits, the Legislature might consider going even further in 2011–12. For example, an increase to $40 per unit would generate roughly $40 million more in fee revenues than under the Governor’s proposal, and allow the state to take fuller advantage of the effective federal subsidy of CCC programs. (The Legislature might consider setting aside a portion of funding generated by any fee increases for purposes of outreach and technical assistance to students on the federal tax benefits.)

Recommend Adoption of Longer–Term Fee Strategy Linked to Federal Tax Credits. As noted above, AOTC is scheduled to sunset at the end of the 2012 tax year. If AOTC is not extended, the Hope tax credit would return. Since the Hope tax credit covers 100 percent of the first $1,200 in fee costs, an eligible student taking 30 units per academic year would still be fully covered at a rate of $40 per unit. If AOTC is made a permanent program in 2013 (as the president has proposed), we recommend that the Legislature adopt a fee strategy that increases the annual level of CCC fees to the amount that is fully covered by AOTC. For example, assuming that AOTC continues to fully reimburse students for 100 percent of the first $2,000 in fees and textbook costs, the state could eventually increase fees to $60 per unit (or $1,800 for a full–time student). This would allow eligible students taking 30 units per year to take full advantage of the tax credit—while still leaving $200 for reimbursement of textbook costs. Given that only three other states currently charge full–time students less than $1,800 to attend a community college, even at $60 per unit CCC fees would remain among the very lowest in the country.