The Governor’s proposed 2011–12 budget includes sizable General Fund reductions for the state’s university systems and the community colleges totaling about $1.4 billion. While the administration does not provide many specific proposals as to how those reductions would be accommodated, they could affect access to higher education programs, the price paid by students, average class size, and the availability of various related services, among other things. The budget assumes fee and tuition increases at all three public segments.

At the same time, the Governor’s budget would fully fund financial aid programs, thus helping to ensure that cost does not prevent enrollment by financially needy students. The budget also includes General Fund augmentations to backfill one–time federal funds received by the universities in 2010–11, pay for increased retirement costs, and cover other workload adjustments.

This publication provides context to help the Legislature think about what the Governor’s proposed budget could mean for higher education. It is divided into two parts. The first part reviews how the state’s budget crisis has affected higher education to date, while the second part assesses how the Governor’s budget proposal would affect higher education in 2011–12. In other publications we recommend specific budget actions for the Legislature to take with regard to higher education.

In recent years, confusion has surrounded the question of how the budget crisis has affected higher education budgets. To a large extent, this confusion results from different characterizations that focus on different funding sources or use different baselines for their comparisons. As we have explained elsewhere, there is no single correct way to describe higher education funding. However, below we present what we consider to be the most relevant facets of changes to higher education funding since 2007–08. That year is considered by most to be the last fairly “normal” year for higher education funding—enrollment growth and cost–of–living increases were funded at all three segments, no large unallocated reductions were imposed, and no payments for new costs were deferred to future years.

As shown in Figure 1, General Fund support for higher education has declined by 5 percent between 2007–08 and 2010–11. This includes reductions of 10 percent to 11 percent for the universities and 6 percent for California Community Colleges (CCC), and growth of more than 40 percent in state financial aid programs. (Note that these figures and the others in this section show only budget changes through the current year—not the Governor’s proposal for 2011–12.)

Figure 1

Higher Education General Fund Appropriations

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

Change From 2007–08

|

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

UC

|

$3,257.4

|

$2,418.3

|

$2,591.2

|

$2,911.6

|

–$345.8

|

–11%

|

|

CSU

|

2,970.6

|

2,155.3

|

2,345.7

|

2,682.7

|

–287.9

|

–10

|

|

CCC

|

4,272.2

|

3,975.7

|

3,735.3

|

3,994.7

|

–277.5

|

–6

|

|

Hastings

|

10.6

|

10.1

|

8.3

|

8.4

|

–2.2

|

–21

|

|

CPEC

|

2.1

|

2.0

|

1.8

|

1.9

|

–0.2

|

–12

|

|

CSAC

|

866.7

|

888.3

|

1,043.5

|

1,224.3

|

357.6

|

41

|

|

Totals

|

$11,379.6

|

$9,449.7

|

$9,725.8

|

$10,823.5

|

–$556.0

|

–5%

|

Simply looking at General Fund appropriations can be misleading for purposes of understanding trends in programmatic support for higher education. Other sources of funding (primarily tuition and fee revenue, local property taxes, and federal stimulus funding) work in combination with General Fund revenue to support core higher education programs. In addition, some budget solutions (such as funding “deferrals”) create General Fund savings without having a direct impact on programs. Moreover, increases or decreases in enrollment affect the level of resources available to serve each student and thus should be factored into an analysis of programmatic funding.

In Figure 2, we combine all core sources of funding and adjust for deferrals and enrollment changes to show programmatic support per student from 2007–08 through 2010–11. Over that period, funding per student increased 3.6 percent and 4.6 percent at University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU), respectively, and declined 3.9 percent at CCC. Note that this figure does not adjust funding levels for inflation. This is for two reasons: (1) inflation rates have generally been low, and (2) state law adopted in 2009 expressly prohibits automatic annual price increases for higher education and most other areas of state government. At the same time, we acknowledge that any price increases experienced by the segments have the effect of eroding their programmatic funding.

Figure 2

Programmatic Funding Per Student for Higher Educationa

|

|

2007–08 Actual

|

2008–09 Actual

|

2009–10 Actual

|

2010–11 Estimated

|

Change From 2007–08

|

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

$20,345

|

$18,948

|

$17,484

|

$21,087

|

$741.8

|

3.6%

|

|

California State University

|

11,038

|

10,791

|

10,143

|

11,542

|

503.8

|

4.6

|

|

California Community Collegesb

|

5,731

|

5,636

|

5,551

|

5,506

|

–224.8

|

–3.9

|

In our opinion, higher education has generally been spared the kinds of programmatic reductions experienced by other state sectors since the recession began. Although the segments have experienced significant General Fund reductions, these reductions by 2010–11 have been backfilled with other sources of revenue, primarily student tuition and federal stimulus funding. As a result, students are now paying a higher share of the cost of their education, as we describe in the next section.

College affordability is determined by several factors. These include tuition levels, other costs of attending college, personal income and financial resources, and the availability of financial aid. California historically has had relatively low tuition and robust financial aid programs compared with other states. These advantages have been somewhat offset by higher–than–average living expenses.

From this comparatively low starting point, tuition charges at the state’s public universities have increased steadily in recent years. Tuition–paying students—those who do not qualify for financial aid due to their income levels or other factors—are paying significantly more than they paid in 2007–08. Many students, however, do not pay tuition. State and campus financial aid programs cover full or partial tuition for nearly half of university students, and full tuition for more than half of community college full–time equivalent (FTE) students.

Tuition by Any Other Name. In 2010, UC and CSU ended the longtime practice of avoiding the term tuition. Some student charges previously called mandatory systemwide fees (including the Education Fee at UC and the State University Fee at CSU) are now called tuition.

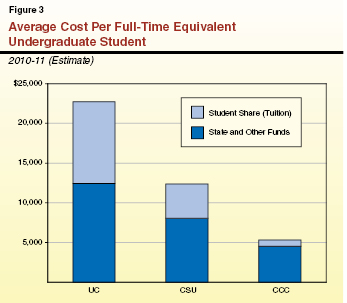

Students Paying Higher Share of Costs. Tuition represents a growing share of average educational costs at all three segments. In 2007–08, the full tuition charge represented about one–third of average costs at UC, one–quarter at CSU, and 11 percent at CCC. This year the tuition shares of cost are 45 percent, 35 percent, and 15 percent, respectively. Figure 3 shows amounts currently paid by a tuition–paying student and the state at each segment.

Tuition at UC Rises to Middle of Comparison Group. Since 2007–08, UC has increased tuition 68 percent, to $10,302 (see Figure 4 on next page). Even with those tuition increases, UC’s tuition is roughly average relative to comparable public research universities in the United States.

Tuition at CSU Rises Steeply, but Remains Lower Than Comparison Institutions. As Figure 4 shows, the four–year increase in CSU tuition is even greater, at 76 percent. Undergraduate tuition is now $4,440 annually. Despite these recent increases, CSU remains at the very bottom of its group of 15 comparison public institutions and far below regional and national averages for state universities.

Figure 4

University Tuition Increases Since 2007–08

|

Academic Year

|

University of California

|

California State University

|

|

2008–09

|

7.4%

|

10.0%

|

|

2009–10

|

9.3

|

32.1

|

|

2009–10 midyear additional increase

|

15.0

|

—

|

|

2010–11

|

15.0

|

5.0

|

|

2010–11 midyear additional increase

|

—

|

5.0

|

|

2011–12

|

8.0

|

10.0

|

|

Cumulative Increases

|

67.6%

|

76.2%

|

CCC Fees Remain Lowest in Nation. California has long had the lowest community college fees in the nation. Fees were increased from $20 per unit ($600 per year for a student taking a full course load) to $26 per unit ($780 per year) in 2009–10. At this level, CCC fees are about one–fourth of the national average for community college fees, and are more than $400 below those of New Mexico, the state with the second–lowest fees.

California students with financial need (as defined by federal aid guidelines) may qualify for a range of financial assistance including grant aid from the federal government, state, universities, and private sources; full or partial fee waivers; and student loans.

Many Students Shielded From Tuition Increases. About half of students receive need–based financial aid specifically to cover full tuition costs. The state’s primary student financial aid program is the Cal Grant program. About 240,000 students at public and private postsecondary institutions will receive an estimated $1.3 billion in Cal Grant awards this year. Income ceilings for eligibility are relatively high. For example, a student from a four–person family making up to $78,100 per year could qualify. Most Cal Grant awards include full tuition coverage at the universities, and Cal Grant recipients at the CCC receive fee waivers.

Cal Grants Are Tied to Tuition Levels. The Cal Grant award amount for UC and CSU students is set by statute at the mandatory systemwide tuition and fee level for each segment. (Some Cal Grant recipients are not eligible for a tuition payment in their first year, but most of these students receive additional support from the institutions to cover this cost.) When the segments increase tuition, California Student Aid Commission (CSAC) increases award amounts accordingly. As a result, all university students whose tuition is paid by Cal Grants are protected from tuition increases.

Campus–Based Financial Aid Programs Expand With Tuition Revenues. For many years, the universities have set aside a portion of revenues from tuition increases, currently about one–third, to augment their own financial aid programs. In the current year, UC and CSU campuses are providing about $1.5 billion in student financial aid, primarily from tuition revenues. Between Cal Grants and institutional funds, tuition is fully covered for about 45 percent of CSU students and 47 percent of UC students. In addition, UC campuses offer partial tuition coverage, equal to half the amount of any tuition increases, to eligible students with family incomes up to $120,000 who are not otherwise eligible for grant assistance. The UC plans to expand this program to cover 100 percent of the 2011–12 tuition increase for these students.

Beyond tuition coverage, campus–based aid at the universities also covers some non–tuition expenses (such as books and living expenses). In fact, UC uses its campus–based aid to cover any remaining financial need not covered by other sources (such as federal aid and family and student contributions) for all of its students. Similar programs at CSU ensure all need is met for some, but not all, students.

The CCC’s primary campus–based aid is provided through the Board of Governors (BOG) fee waiver program. All financially needy students qualify to have their enrollment fees waived, and thus are not affected by fee increases. The CCC estimates that more than half of all enrollment fees are waived under this program.

Federal Aid Programs Have Expanded. Although not directly tied to tuition levels, federal financial aid programs have helped to offset some cost increases in recent years.

- The maximum federal Pell Grant has increased by $1,240 since 2007–08, to $5,550 in the current year. About one–third of UC and CSU students qualify for these grants.

- Many military veterans returning from active duty are benefiting from the post–9/11 GI Bill, which became effective in August, 2009. Benefits include full tuition and fee coverage at the public segments, a monthly housing allowance, and an annual stipend for books and supplies.

- The American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC), effective from 2009 through 2012, reimburses students or their parents with a family income of up to $160,000 for up to $2,500 of qualified educational costs. Even families who do not owe taxes can qualify for partial refunds of educational costs under the AOTC. This is an enhancement of the Hope credit, which provided up to $1,800 in reimbursements, had lower income ceilings, and was not reimbursable.

Many Perceive Price as Barrier. Despite these benefits from the state, campuses, and the federal government, there is a public perception that higher tuition is a barrier to attending college. According to a fall 2010 survey by the Public Policy Institute of California, more than two–thirds of Californians—and more than 80 percent of lower–income respondents—believe the price of a college education keeps students who are qualified and motivated to go to college from doing so. This suggests a need for more effective outreach to financially needy students and their families.

In the current year, CCC has slightly less funding per student than it had before the current recession began, while UC and CSU have slightly more (after taking into account revenue from tuition increases). Meanwhile, state financial aid programs have received funding increases to cover increased participation and the increased cost of fee coverage. While higher education has been spared the programmatic reductions experienced by most other sectors of state government, it has been affected by the budget crisis in several key ways.

Some Cost Increases Not Funded. As noted earlier, the segments have not received inflation adjustments for several years. Even though inflation rates have generally been low, the segments have had to accommodate general cost increases. Some unfunded costs have been significant, such as UC’s resuming of employer payments for the UC Retirement Program. (Unlike UC, CSU has received General Fund augmentations to cover increased retirement costs.)

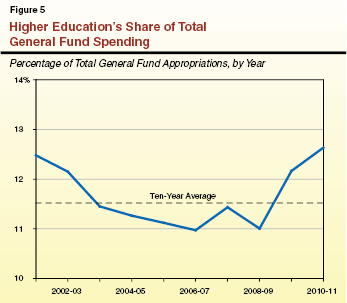

General Fund Reductions and Augmentations Have Been Uneven. While most state agencies have experienced significant budget dislocations in the past several years, General Fund support for higher education has been particularly volatile. Recent state higher education budgets have included retroactive funding reductions, midyear budget changes, and partial restorations of past cuts. As shown in Figure 5, higher education’s share of total state General Fund support has fluctuated year by year. While there is no policy reason to expect higher education’s share of the state budget to remain fixed, the fluctuations appear disconnected from tuition increases, enrollment levels, and other factors that one might expect to influence higher education’s need for General Fund support. (Note that the Governor’s 2011–12 budget proposal would reduce higher education’s share to 11.6 percent, which is the average of the past ten years.)

Campuses Contending With Funding Constraints. As a result of this General Fund volatility, the higher education segments in some years have had to tap into funding reserves and take actions to reduce per–student costs—increasing class size, furloughing employees, and reducing various campus services and overhead, among others. Moreover, the universities in particular have sought to limit enrollment, employing various enrollment management practices such as increasing admission standards, restricting the number of courses students can take, suspending summer sessions, and other techniques. Some campuses have also boosted revenues by enrolling more nonresident students. The lack of inflationary adjustments has generally prevented faculty and staff salary and benefits increases.

The Governor’s budget proposal provides $15.9 billion for higher education, including $9 billion from the General Fund, $1.9 billion in local property tax revenues, and $3.8 billion from student fees (see Figure 6). The proposal reduces General Fund support for higher education by $1.8 billion or about 17 percent from the 2010–11 level. These reductions are overstated, however, due to a proposal in the budget to shift $947 million in funding for the Student Aid Commission from the General Fund to federal funds. After adjusting for this shift, the year–over–year reduction in higher education spending is $875 million, or 8 percent. Figure 7 lists the primary reductions and augmentations that produce this net year–to–year reduction.

Figure 6

Higher Education Core Funding

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2007–08 Actual

|

2008–09 Actual

|

2009–10 Actual

|

2010–11 Estimated

|

2011–12 Proposed

|

Change From 2010–11

|

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$3,257.4

|

$2,418.3

|

$2,591.2

|

$2,911.6

|

$2,524.1

|

–$387.6

|

–13%

|

|

Tuitiona

|

1,116.8

|

1,166.7

|

1,449.8

|

1,793.6

|

1,909.5

|

116.0

|

6

|

|

ARRA

|

—

|

716.5

|

—

|

106.6

|

—

|

–106.6

|

—

|

|

Lottery

|

25.5

|

24.9

|

26.1

|

30.0

|

30.0

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$4,399.7

|

$4,326.4

|

$4,067.0

|

$4,841.9

|

$4,463.6

|

–$378.2

|

–8%

|

|

California State University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$2,970.6

|

$2,155.3

|

$2,345.7

|

$2,682.7

|

$2,291.3

|

–$391.4

|

–15%

|

|

Tuitiona

|

916.3

|

1,104.5

|

1,210.8

|

1,254.9

|

1,400.7

|

145.7

|

12

|

|

ARRA

|

—

|

716.5

|

—

|

106.6

|

—

|

–106.6

|

—

|

|

Lottery

|

58.1

|

42.1

|

42.4

|

45.8

|

45.8

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$3,945.0

|

$4,018.4

|

$3,599.0

|

$4,090.1

|

$3,737.8

|

–$352.3

|

–9%

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$4,272.2

|

$3,975.7

|

$3,735.3

|

$3,994.7

|

$3,599.8

|

–$394.9

|

–10%

|

|

Fees

|

291.3

|

302.8

|

353.6

|

350.1

|

456.6

|

106.5

|

30

|

|

Local property taxes

|

1,970.8

|

2,028.8

|

1,999.8

|

1,892.1

|

1,873.5

|

–18.6

|

–1

|

|

ARRA

|

—

|

—

|

35.0

|

4.0

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Lottery

|

168.7

|

148.7

|

163.0

|

168.5

|

168.5

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$6,702.9

|

$6,456.0

|

$6,286.7

|

$6,409.4

|

$6,098.3

|

–$311.0

|

–5%

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$10.6

|

$10.1

|

$8.3

|

$8.4

|

$6.9

|

–$1.4

|

–17%

|

|

Feesa

|

21.6

|

26.6

|

30.7

|

34.2

|

35.3

|

1.1

|

3

|

|

Lottery

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.1

|

0.2

|

0.2

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

$32.3

|

$36.8

|

$39.1

|

$42.7

|

$42.4

|

–$0.3

|

–1%

|

|

California Postsecondary Education Commission

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$2.1

|

$2.0

|

$1.8

|

$1.9

|

$1.9

|

$0.1

|

4%

|

|

California Student Aid Commission

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$866.7

|

$888.3

|

$1,043.5

|

$1,224.3

|

$577.6

|

–$646.8

|

–53%

|

|

Otherb

|

—

|

24.0

|

32.0

|

100.0

|

976.8

|

876.8

|

877

|

|

Totals

|

$866.7

|

$912.3

|

$1,075.5

|

$1,324.3

|

$1,554.4

|

$230.0

|

17%

|

|

Grand Totals

|

$15,948.7

|

|

$15,069.2

|

$16,710.2

|

$15,898.5

|

–$811.7

|

–5%

|

|

General Fund

|

$11,379.6

|

$9,449.7

|

$9,725.8

|

$10,823.5

|

$9,001.5

|

–$1,822.0

|

–17%

|

|

Fees/Tuitiona

|

2,346.0

|

2,600.6

|

3,044.9

|

3,432.8

|

3,802.1

|

369.3

|

11

|

|

ARRA

|

—

|

1,433.0

|

35.0

|

217.2

|

—

|

–217.2

|

—

|

|

Local property taxes

|

1,970.8

|

2,028.8

|

1,999.8

|

1,892.1

|

1,873.5

|

–18.6

|

–1

|

|

Lottery

|

252.4

|

215.8

|

231.7

|

244.6

|

244.6

|

—

|

—

|

|

Otherb

|

—

|

24.0

|

32.0

|

100.0

|

976.8

|

876.8

|

877

|

Figure 7

Components of Net $1.8 Billion General Fund Reduction For Higher Education

|

Decreases

|

|

$500 million unallocated reduction for UC.

|

|

$500 million unallocated reduction for CSU.

|

|

$400 million unallocated reduction for CCC.

|

|

$129 million “deferral” of some CCC apportionment funding from 2011–12 to 2012–13.

|

|

$947 million reduction in General Fund support for the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC), replaced with the same amount of federal funding.

|

|

Increases

|

|

$371 million augmentation to cover increased Cal Grant costs.

|

|

$212 million augmentation to backfill one–time federal funding in the universities’ 2010–11 budget.

|

|

$70 million augmentation to backfill one–time Student Loan Operating Fund support in CSAC’s 2010–11 budget.

|

Compared with our benchmark of 2007–08, the Governor’s proposed would:

- Reduce General Fund support for higher education by 21 percent.

- Keep total higher education funding about even.

- Reduce per–student funding at UC and CSU by about 4.5 percent (assuming no enrollment change).

In general, the Governor’s 2011–12 budget proposal adjusts the universities’ budgets in two steps:

- It augments the universities’ General Fund appropriations by $106 million each, replacing one–time federal stimulus funding that had supplemented the universities state support in the current–year budget. This has no programmatic effect; it is simply a fund swap.

- It then imposes unallocated $500 million reductions to each university’s General Fund support.

The administration says that the unallocated reductions are “intended to minimize fee and enrollment impacts on students by targeting actions that lower the cost of instruction.” However, the administration does not explain how it expects this goal to be achieved.

The Governor proposes a $400 million unallocated reduction to CCC apportionments, as well as a new deferral of $129 million. The deferral has no programmatic effect; it simply delays into the next fiscal year a state payment of $129 million to cover CCC costs incurred in 2011–12. This new deferral would bring CCC’s ongoing deferrals up to $961 million—or about 17 percent of its annual Proposition 98 appropriation.

While the Governor offers no specific proposals for allocating the $400 million apportionments reduction, he suggests that changes to allocation formulas (including a change in how and when the number of students to be funded at each campus is counted) could better align campus incentives with state objectives. In addition, revenue from a proposed fee increase (see below) would in effect compensate for $110 million of CCC’s unallocated reduction, leaving a net reduction of $290 million.

Past, current, and proposed enrollment levels for the higher education segments are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8

Higher Education Enrollment

Resident Full–Time Equivalent Students

|

|

2007–08 Actual

|

2008–09 Actual

|

2009–10 Actual

|

2010–11 Budgeted

|

2011–12 Proposed

|

Change From 2010–11

|

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

166,206

|

172,142

|

174,681

|

170,005

|

170,005

|

—

|

—

|

|

Graduate

|

24,556

|

24,967

|

28,218

|

27,366

|

27,366

|

—

|

—

|

|

Health Sciences

|

13,144

|

13,449

|

13,675

|

12,606

|

12,606

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

(203,906)

|

(210,558)

|

(216,574)

|

(209,977)

|

(209,977)

|

(—)

|

(—)

|

|

California State University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

304,729

|

307,872

|

294,736

|

294,363

|

294,363

|

—

|

—

|

|

Graduate/post–baccalaureate

|

49,185

|

49,351

|

45,553

|

45,496

|

45,496

|

—

|

—

|

|

Subtotals

|

(353,914)

|

(357,223)

|

(340,289)

|

(339,859)

|

(339,859)

|

(—)

|

(—)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

1,182,627

|

1,260,498

|

1,254,487

|

1,187,807

|

1,210,507

|

22,700

|

1.9%

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

1,262

|

1,291

|

1,250

|

1,250

|

1,250

|

—

|

—

|

|

Totals

|

1,741,709

|

1,829,570

|

1,812,600

|

1,738,893

|

1,761,593

|

21,575

|

1.2%

|

The current (2010–11) budget directs UC to serve 209,977 FTE students, and CSU to serve 339,873 FTE students. The Governor proposes no new enrollment funding for the universities in 2011–12. In recent years, the state budget has included language specifying the number of FTE students the segments are expected to enroll. The Governor does not suggest a specific enrollment target for 2011–12, and instead proposes budget language directing the universities to set their own targets “in consultation with the Administration and the Legislature.”

For CCC, the administration proposes a $110 million augmentation to increase funded enrollment by 1.9 percent (or about 23,000 FTE students). However, as noted above, the administration also proposes a $400 million reduction to CCC apportionments. Combined, these two proposals lead to a net reduction of $290 million in CCC apportionment funding. In addition, most CCC campuses are already enrolling more students than they are funded to serve. For these reasons, we believe it is unlikely to expect an increase in systemwide community college enrollment under the Governor’s budget.

Figure 9 shows past, current, and proposed annual student fees at the public colleges and universities.

Figure 9

Higher Education Annual Tuition/Fees

Full–Time Resident Students

|

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

2011–12 Proposed

|

Change From 2010–11

|

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

University of California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

$6,636

|

$7,126

|

$8,373a

|

$10,302

|

$11,124

|

$822

|

8%

|

|

Graduate

|

7,440

|

7,986

|

8,847

|

10,302

|

11,124

|

822

|

8

|

|

California State University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

2,772

|

3,048

|

4,026

|

4,440a

|

4,884

|

444

|

10

|

|

Teacher credential

|

3,216

|

3,540

|

4,674

|

5,154a

|

5,670

|

516

|

10

|

|

Graduate

|

3,414

|

3,756

|

4,962

|

5,472a

|

6,018

|

546

|

10

|

|

Doctoral

|

7,380

|

7,926

|

8,676

|

9,546

|

9,546

|

—

|

—

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

600

|

600

|

780

|

780

|

1,080

|

300

|

38

|

|

Hastings College of the Law

|

21,303

|

26,003

|

29,383

|

36,000

|

37,080

|

1,080

|

3

|

The UC and CSU have already approved tuition increases of 8 percent and 10 percent, respectively, for 2011–12. In addition, CSU adopted a 5 percent midyear increase in 2010–11 which will further raise student tuition payments when its full–year effect is realized in 2011–12. Both universities have announced plans to continue their practice of setting aside one–third of new tuition revenue to augment campus financial aid programs. In combination with Cal Grants, these programs fully cover fees for nearly half of UC and CSU students.

The Governor proposes the CCC student fee be increased from $26 per unit to $36 per unit. (As noted above, CCC would keep the associated revenue, which would in effect backfill a portion of the Governor’s proposed $400 million cut.) Even with this increase, California’s community college fees would remain by far the lowest in the nation. In addition, the BOG’s fee waiver program waives fees for all financially needy students—about half of all FTE students enrolled at CCC.

As shown in Figure 10, the Governor proposes $307 million in bond spending on capital outlay at the three segments. About two–thirds of this spending would come from new lease–revenue bonds, with the remainder coming from general obligation bonds already approved by voters. The budget also projects $756 million in General Fund expenditures in 2011–12 to service existing general obligation fund debt for higher education projects.

Figure 10

Higher Education Capital Outlay Appropriations

(In Millions)

|

|

2007–08

|

2008–09

|

2009–10

|

2010–11

|

Proposed 2011–12

|

|

University of California

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General obligation bonds

|

$450.0

|

$57.0

|

$30.9

|

$9.8

|

$9.3

|

|

Lease–revenue bonds

|

70.0

|

205.0

|

—

|

342.9

|

45.3

|

|

Subtotals

|

($520.0)

|

($262.0)

|

($30.9)

|

($352.7)

|

($54.6)

|

|

California State University

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General obligation bonds

|

$417.0

|

$72.0

|

$16.1

|

$13.4

|

$2.8

|

|

Lease–revenue bonds

|

—

|

224.0

|

—

|

76.0

|

201.2

|

|

Subtotals

|

($417.0)

|

($296.0)

|

($16.1)

|

($89.4)

|

($204.0)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

$536.0

|

$444.0

|

$205.0

|

$111.0

|

$48.6

|

|

Totals

|

$1,473.0

|

$1,002.0

|

$252.0

|

$553.1

|

$307.2

|

The Governor’s 2011–12 budget proposal for higher education includes sizable General Fund reductions to help balance the state budget, increases in student tuition and fees to partially backfill those reductions, and increases in student aid to help prevent cost increases from affecting access for financially needy students. The budget generally returns higher education’s share of state General Fund support to the average level it has received over the past decade.

At the same time, the Governor’s budget does not clearly specify how the segments should absorb the proposed net funding reductions. We recommend that the Legislature express its expectations about this issue as part of the budget process. We also recommend that the Legislature consider achieving some General Fund savings for the universities in the current year, which could help reduce the size of the budget–year reductions proposed by the Governor. We elaborate on these recommendations in other publications.